1. Introduction

Hip fractures constitute one of the most devastating injuries in the geriatric population, with incidence expected to increase dramatically due to global aging demographics. The annual number of hip fractures is estimated to rise from 1.7 million in 1990 to 6.3 million by 2050 [

1]. Allogeneic blood transfusion remains a frequently employed intervention in geriatric patients undergoing surgery for hip fractures, largely due to perioperative blood loss and a high prevalence of pre-existing anemia [

2,

3]. Nonetheless, allogeneic blood transfusion in geriatric hip fracture patients carries a risk of adverse outcomes, including higher rates of postoperative urinary tract infections [

4], prolonged hospital stays [

5], and potentially increased long-term mortality [

6,

7]. Accordingly, in an effort to minimize the need for blood transfusion and mitigate transfusion-related morbidity in this vulnerable patient population, several strategies have been employed under the framework of patient blood management. These strategies comprise preoperative anemia screening and treatment [

8], intra-operative blood-sparing techniques such as tranexamic acid administration [

9], and restrictive transfusion thresholds [

10].

Among the pharmacologic blood management approaches, Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose (FCM) has been shown to effectively reduce the need for ABT and improve postoperative hemoglobin in various surgical settings, including cardiac [

11] and abdominal surgery [

12]. It also offers practical advantages, including the ability to administer 1 g in a single 15-minute infusion, equivalence to 1000 mg iron sucrose, and a favorable safety and tolerability profile [

13,

14]. Additionally, FCM may confer additional clinical benefit by correcting iron deficiency anemia, which is a prevalent and clinically significant condition associated with impaired postoperative recovery, delayed rehabilitation, prolonged hospitalization, and increased mortality [

15]. Despite its established benefits in transfusion reduction and anemia correction, our literature review identified a notable gap. Although previous studies have explored iron supplementation after hip fracture surgery, evidence on mortality impact remains lacking. Parker et al. [

2] found no benefit of oral iron in a randomized trial, while Yoon et al. [

16] showed reduced transfusion rates with preoperative IV FCM in a retrospective study, but no mortality difference. Additionally, Cuenca et al. [

17] reported reduced transfusion and 30-day mortality with preoperative iron sucrose, though in a non-randomized design and using a different iron formulation. To our knowledge, no randomized controlled trial has evaluated whether preoperative IV iron impacts mortality in this vulnerable population.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate whether preoperative administration of FCM reduces 1-year all-cause mortality in elderly patients undergoing surgery for hip fractures. Secondary aim included assessing the effects of FCM on perioperative transfusion requirements, postoperative hemoglobin levels, length of hospital stay, and early postoperative complications. We hypothesized that a single preoperative dose of FCM would be associated with lower postoperative 6-month and 1-year mortality, decreased perioperative transfusion requirements, and improved perioperative outcomes compared to standard care without iron supplementation.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Eligibility Criteria

This study was designed as a prospective, single-center, randomized controlled trial and was conducted at a university hospital between October 2023 and May 2024. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of ****** (Approval No. 1916246), and all study procedures were carried out in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Registry number NCT06080893).

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they (1) were aged 65 years or older and (2) presented with a hip fracture requiring surgical intervention. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) current use of iron therapy at the time of admission or a history of iron supplementation within the past three months; (2) receipt of any blood transfusion prior to surgery; (3) presence of a pathological fracture; (4) multiple trauma involving other long bones or anatomical regions; (5) known allergy or documented hypersensitivity to any intravenous iron formulation; and (6) unwillingness to participate in the study.

2.2. Randomisation and Intervention

Patients were randomly allocated into two groups—FCM group and control group—using sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes. Randomisation was performed after confirmation of eligibility, and the treating physicians were blinded to group assignment. A single 1000 mg IV dose of FCM was administered to patients approximately 12 hours before surgery, via slow infusion over 20–30 minutes [

18]. The control group received no placebo or iron preparation.

2.3. Perioperative Transfusion Protocol

All patients were managed according to a restrictive transfusion strategy. Transfusions were permitted only if the hemoglobin level fell below 8 g/dL or if patients developed clinical signs of anemia, such as chest pain of cardiac origin, congestive heart failure, unexplained tachycardia, or hypotension unresponsive to fluid therapy [

19]. Blood was administered one unit at a time, and the patient’s clinical status was reassessed before each additional transfusion. Perioperative transfusion requirements were recorded, including total transfused units and transfusion index. The term perioperative refers to transfusions administered intraoperatively and postoperatively during the follow-up period. Transfusion status was further categorized as follows: no transfusion, transfusion with 1–2 units, and transfusion with ≥3 units of erythrocyte suspension (ES replacement).

2.4. Outcome Measures and Follow-Up Protocol

The primary outcomes of the study were 6-month and 1-year mortality after hip surgery in geriatric hip fracture patients. Secondary outcomes included preoperative anemia status, postoperative anemia status, preoperative hemoglobin levels (measured at time of admission), postoperative hemoglobin levels (measured 24 hours after surgery), hemoglobin levels at discharge, and length of hospital stay (LOS). Hemoglobin levels were reassessed at the sixth postoperative week in patients who did not receive any additional iron supplementation during the follow-up period.

Mortality follow-up was performed at both 6 and 12 months postoperatively through scheduled outpatient visits or structured telephone interviews. When necessary, mortality status was verified using hospital records and national health registry databases to ensure accuracy. All surviving patients were followed for at least 12 months.

Baseline characteristics—including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), type of fracture, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification [

20], type of surgical procedure, and comorbidities—were prospectively recorded at the time of admission. A detailed comorbidity assessment was also performed for each patient. Evaluated comorbidities included renal disease, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction, pulmonary disease, neurologic disorders (e.g., previous stroke, transient ischemic attack, Parkinson’s disease), dementia, and malignancy. In addition to individual comorbidities, the total number of comorbid conditions was recorded and categorized as either 0–1 or ≥2. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was also calculated to quantify the overall burden of chronic illness and facilitate comparison between groups [

21].

Beyond clinical outcomes, the study also evaluated the safety profile of intravenous FCM administration. All patients in the FCM group were prospectively monitored for adverse events, including hypersensitivity reactions, infusion-related complications, or other unexpected side effects. Any such events were documented during hospitalization and throughout the follow-up period.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Normality of continuous variables was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test and histograms. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages (%). Independent-samples t-test was used for comparing normally distributed continuous variables between the FCM and control groups. For categorical variables, comparisons were made using the Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Within-group comparisons of repeated hemoglobin measurements across time points were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA or Friedman test, depending on the distribution. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Bonferroni correction where applicable. To identify independent predictors of 6-month and 1-year mortality, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed using a backward stepwise elimination method. Results were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Sample size was calculated using G*Power software based on the effect size reported by Cuenca et al. [

17], who observed a 19.3% difference in 30-day mortality between standard care and patients receiving perioperative IV iron sucrose. Assuming a moderate effect size (w = 0.5), a significance level of 0.05, and power of 95%, a minimum sample size of 220 patients (110 per group) was required.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Comorbidity Profile

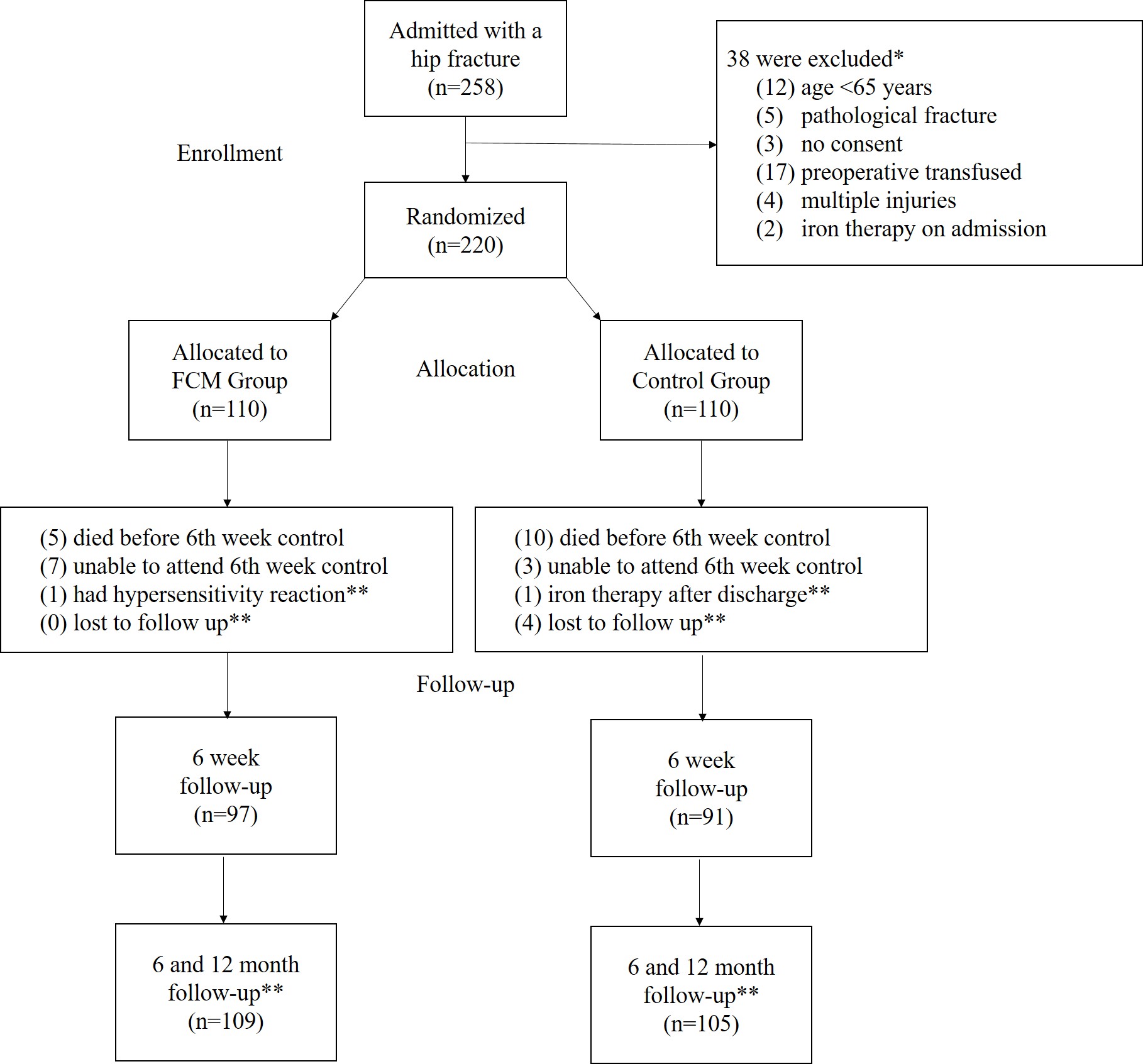

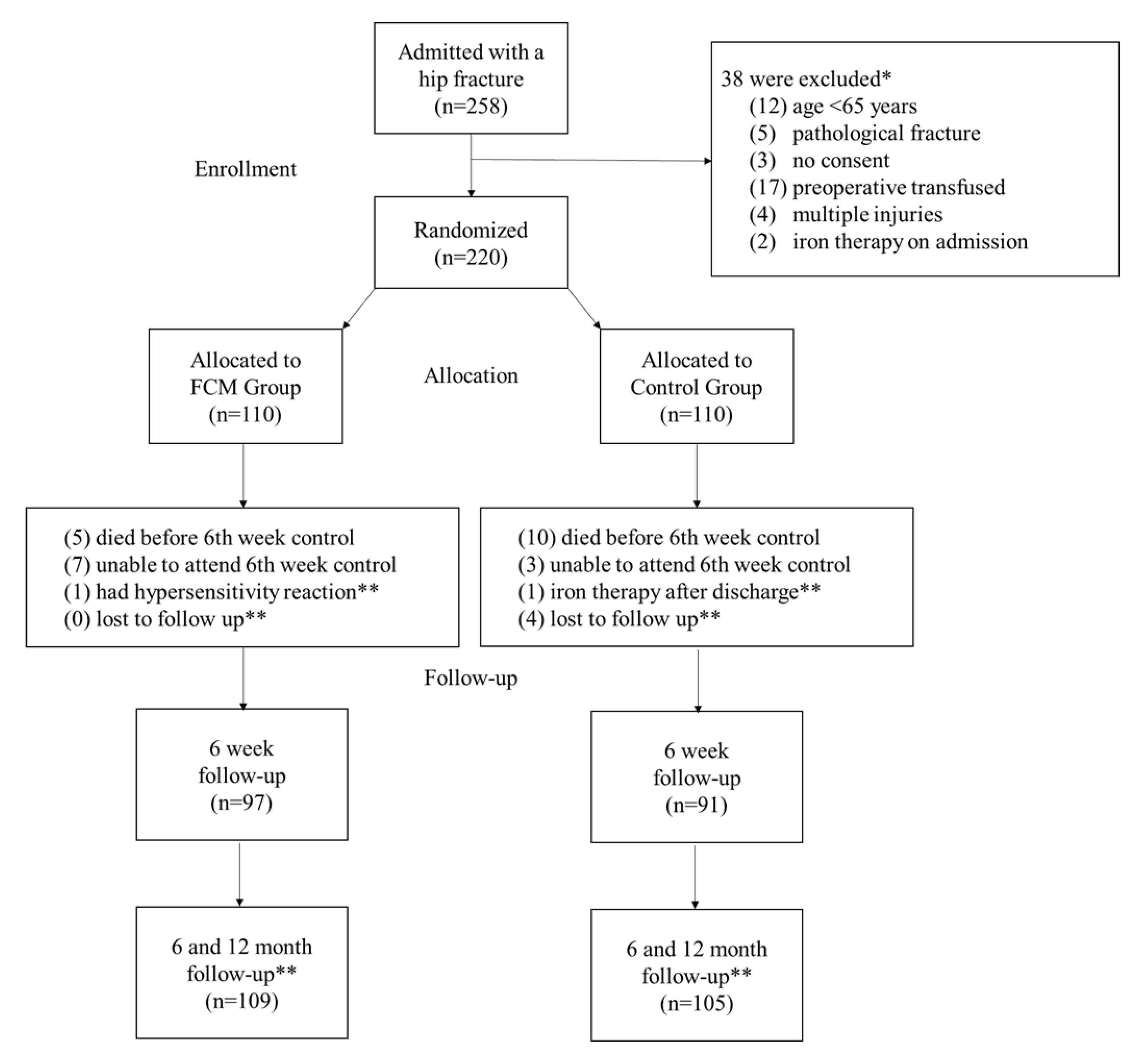

As illustrated in the flowchart (

Figure 1), a total of 258 patients presenting with hip fractures were initially screened for eligibility. Following the application of predefined exclusion criteria, 220 patients were enrolled and randomized into two groups: the FCM group (n = 110) and the control group (n = 110). The flowchart also illustrates the progression of patients through each stage of the study, including group allocation, 6th-week outpatient follow-up, and 6- and 12-month mortality assessments, along with documented reasons for loss to follow-up.

No statistically significant differences were observed between the FCM and control groups in terms of baseline characteristics and comorbidity profiles, except for the higher prevalence of dementia in the control group (17% vs. 7%, p = 0.016). Detailed distributions of baseline characteristics and comorbidity variables are outlined in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

3.2. Primary Outcomes: Mortality rates

The 6-month mortality rate was 22.9% in the FCM group and 39.0% in the control group (p = 0.011). The 1-year mortality rate was 28.4% in the FCM group and 42.9% in the control group (p = 0.028). Both time points demonstrated significantly lower mortality in the FCM group (

Table 3).

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

3.3.1. Anemia Status

Preoperative anemia was present in 88 patients (81%) in the FCM group and 86 patients (82%) in the control group (p = 0.826). Postoperative anemia was observed in 107 patients (98%) in the FCM group and 101 patients (96%) in the control group (p = 0.382). Anemia at discharge was found in 106 patients (97%) in the FCM group and 99 patients (94%) in the control group (p = 0.281). At the 6th postoperative week, anemia was present in 97 patients (89%) in the FCM group and 103 patients (98%) in the control group. This was the only time point at which a statistically significant difference was observed between the groups, with a higher proportion of patients being non-anemic in the FCM group (

p = 0.007) (

Table 3).

3.3.2. Hemoglobin Trends Over Time

In within-group analyses, hemoglobin levels differed significantly at different time points in both the FCM and control groups. In the FCM group, hemoglobin values at preoperative, postoperative, discharge, and 6th-week time points differed significantly (p < 0.001). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between preoperative values and all subsequent time points (all p < 0.001), as well as between postoperative and 6th-week levels (p = 0.017). In the control group, there was a statistically significant difference in hemoglobin levels across time points (

p < 0.001). However, pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences only between the preoperative values and those measured postoperatively, at discharge, and at the 6th week (

all p < 0.05), with no significant differences observed between postoperative and subsequent time points (

p > 0.05) (

Table 3).

Between-group comparisons of hemoglobin levels at each time point revealed no significant differences in the preoperative period (median 10.8 g/dL [IQR: 9.7–12.3] in the FCM group vs. 10.5 g/dL [IQR: 9.2–11.7] in the control group; p = 0.427) or immediately postoperatively (9.6 g/dL [IQR: 9.0–10.8] in the FCM group vs. 9.9 g/dL [IQR: 9.0–10.6] in the control group; p = 0.159). At discharge, hemoglobin levels were significantly higher in the FCM group (9.7 g/dL [IQR: 8.8–11.1]) compared to the control group (10.2 g/dL [IQR: 9.6–11.4]) (p < 0.001). At the 6th postoperative week, no significant difference was observed between the FCM group [10.4 g/dL [IQR: 9.4–11.0]) and the control group (10.3 g/dL [IQR: 9.9–10.9]) (p = 0.242) (

Table 3).

3.3.3. Perioperative Transfusion Characteristic

The rate of ES transfusion was significantly

lower in the FCM group (30%, n=34) compared to the control group (46%, n=48) (

p = 0.013). Among those who received transfusions, 1–2 units were administered to 97.1% (n=33) in the FCM group and 93.8% (n=45) in the control group. Transfusion of ≥3 units was

rare, observed in 2.9% (n=1) and 6.2% (n=3) of patients in the FCM and control groups, respectively (

Table 3).

3.3.4. Length of Hospitalization

The median length of hospitalization was 11 days (IQR: 7–14) in the control group and 10 days (IQR: 6–10) in the FCM group. Although the hospitalization duration was shorter in the FCM group, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.250) (Table 3).

3.3.5. Adverse Events Related to FCM Administration

No serious adverse events were reported in the FCM group. However, one patient developed a mild hypersensitivity reaction without systemic involvement and was subsequently excluded from the study.

3.4. Multivariate Analysis of Mortality Outcomes

3.4.1. 6-Month Mortality

In the multivariate logistic regression model, preoperative IV FCM administration (OR: 0.330,

p = 0.003), age (per year increase) (OR: 1.062,

p = 0.006), female gender (OR: 0.424,

p = 0.038), CCI score (per point) (OR: 1.398,

p = 0.014), ASA class (high vs. low) (OR: 2.309,

p = 0.035), fracture type (femoral neck vs. intertrochanteric) (OR: 0.388,

p = 0.017), hypertension (present vs. absent) (OR: 6.446,

p = 0.002), and neurologic disorders (present vs. absent) (OR: 1.292,

p = 0.037) were independently associated with 6-month mortality (

Table 4).

3.4.2. 1-Year Mortality

For 1-year mortality, the final model identified preoperative IV FCM administration (OR: 0.449,

p = 0.021), age (OR: 1.059,

p = 0.003), female gender (OR: 0.445,

p = 0.015), CCI score (OR: 1.248,

p = 0.019), ASA class (OR: 2.168,

p = 0.062), hypertension (OR: 3.583,

p = 0.001), and neurologic disorders (OR: 3.266,

p = 0.018) as independent predictors (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

Hip fractures in elderly patients are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly in the presence of perioperative anemia and high transfusion rates. Despite advances in surgical techniques and perioperative care, one-year mortality following hip fracture surgery remains high, as consistently reported in the literature [

22,

23,

24]. Intravenous iron supplementation, particularly with FCM, has been proposed as a promising strategy to optimize preoperative hemoglobin levels and reduce transfusion requirements. While studies in cardiac and abdominal surgeries [

11,

12] have demonstrated favorable effects on hemoglobin restoration and transfusion reduction , evidence from prospective randomized trials specifically focusing on patients undergoing hip fracture surgery remains limited. Therefore, in this randomized controlled trial, we hypothesized that a single preoperative dose of FCM would reduce 6-month and 1-year postoperative mortality and decrease perioperative transfusion requirements, while also improving short-term clinical outcomes. The results of the study confirmed this hypothesis, demonstrating a significant reduction in 6- and 12-month postoperative mortality, along with lower perioperative transfusion rates in the FCM group compared to the control group.

Previous studies investigating iron supplementation following hip fracture surgery have offered limited insight into clinically meaningful outcomes such as postoperative recovery and mortality [

2,

16,

17]. Most available data are derived from retrospective cohorts, non-randomized comparisons, or studies focusing on oral or less potent intravenous iron formulations. Parker (2010) [

2] conducted a randomized trial comparing postoperative oral iron supplementation (200 mg ferrous sulfate twice daily for 28 days, n = 150) with no iron therapy (n = 150) in patients with anemia after hip fracture surgery. The study found no improvement in hemoglobin recovery, transfusion needs, or clinical outcomes, with both groups demonstrating a 1-year mortality rate of 19.3% (29 patients per group). Cuenca (2005) [

17] reported encouraging findings from a prospective, non-randomized study comparing patients who received preoperative intravenous iron sucrose (n = 20) with a control group without iron therapy (n = 57) undergoing hemiarthroplasty for displaced subcapital hip fractures. The iron group demonstrated lower transfusion indices and a significant reduction in 30-day mortality (0% vs. 19.3%, p = 0.034), although the study was limited by small sample size, lack of randomization, and use of a less potent iron formulation [

17].

Yoon et al. (2019) [

16] conducted a retrospective cohort study comparing a liberal transfusion strategy (n = 775) with a restrictive protocol incorporating preoperative intravenous iron sucrose (200 mg) (n = 859) in elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. While the restrictive group showed reduced transfusion rates (48.2% vs. 65.3%, p < 0.001), shorter hospital stays (21.5 ± 36.8 vs. 28.8 ± 29.9 days, p < 0.001), and higher hemoglobin levels at 6 weeks, there was no significant difference in mortality at 30, 60, or 90 days. The retrospective design and lack of randomization may have limited the study’s ability to detect a survival benefit. In contrast to these studies, our trial is the first

prospective, randomized controlled study to evaluate the effect of

preoperative FCMon

both postoperative recovery and 6- and 12-month mortality in geriatric patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. By employing a standardized, high-dose, single-infusion IV iron protocol (1000 mg FCM administered approximately 12 hours preoperatively), our study overcomes key methodological limitations of earlier investigations. These design strengths allow for a more definitive assessment of clinical benefit and represent a significant contribution to the evolving evidence base on patient blood management strategies in this vulnerable population.

Given that mortality was the primary outcome of this study, the significant reduction observed at both 6 and 12 months in the FCM group represents a clinically and statistically meaningful finding. Importantly, multivariate logistic regression analysis confirmed that preoperative IV iron administration was an independent protective factor for mortality at both time points, even after adjusting for age, comorbidity burden, ASA class, and other known prognostic variables. These findings suggest that the observed survival benefit is not merely a reflection of baseline differences but is likely attributable to the intervention itself. While the mechanisms remain speculative, early correction of functional iron deficiency may enhance physiologic resilience, reduce transfusion exposure, and mitigate downstream complications in frail elderly patients undergoing surgery [

12,

25,

26]. Compared to oral iron, which is frequently associated with gastrointestinal intolerance [

2], and iron sucrose, which requires multiple low-dose administrations [

27], FCM offers the advantage of delivering a full replacement dose in a single short infusion with favorable tolerability [

27]. Although serious adverse reactions to FCM are rare, systemic hypersensitivity remains a known risk [

28], as observed in one patient in our study.

Beyond mortality, several secondary outcomes further support the potential benefit of preoperative FCM administration. The FCM group demonstrated significantly lower rates of perioperative transfusion compared to controls, findings that are consistent with previous studies highlighting the transfusion-sparing effects of intravenous iron therapy [

12,

16,

25]. Although hemoglobin levels at six weeks did not differ significantly between groups, patients receiving FCM showed higher discharge hemoglobin values, suggesting more rapid hematologic recovery in the early postoperative period. This early improvement may have contributed to better tolerance of surgical stress and reduced exposure to transfusion-related risks. Although a shorter median length of hospital stay was observed in the FCM group, the difference did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to variability in discharge protocols and comorbidity profiles. Nevertheless, the overall pattern of secondary outcomes is consistent with the hypothesis that timely correction of iron deficiency may facilitate early postoperative recovery in geriatric patients undergoing hip fracture surgery.

This study has certain limitations that warrant consideration. While the sample size was sufficient to detect differences in key clinical outcomes, it may not have been powered to evaluate infrequent adverse events or more nuanced postoperative parameters such as functional status or quality of life. Additionally, the follow-up protocol primarily focused on mortality and hemoglobin dynamics rather than long-term rehabilitation metrics. Despite these limitations, this trial possesses several notable strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first prospective, randomized controlled study to examine the effect of preoperative FCM on mortality and perioperative outcomes in geriatric patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. The use of a standardized transfusion strategy, rigorous randomization, and multivariate adjustment for known prognostic variables enhances the internal validity of the results. Moreover, the focus on clinically meaningful endpoints strengthens its relevance to real-world perioperative care. Importantly, our study includes the largest patient cohort to date examining the optimization of a guideline-based restrictive transfusion strategy supported by preoperative IV FCM administration in geriatric patients with hip fractures.

5. Conclusions

Preoperative administration of intravenous FCM in geriatric patients undergoing hip fracture surgery could reduce both 6-month and 1-year mortality, as well as the need for perioperative blood transfusion. These findings suggest that preoperative IV FCM may contribute to improved survival outcomes in this high-risk population, even in the absence of significant short-term hemoglobin improvement. Further clinical trials are warranted to explore the integration of preoperative IV FCM into restrictive transfusion protocols, and to investigate whether its combination with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents could further enhance outcomes in geriatric hip fracture patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article, therefore supplementary materials are not uploaded.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K. and M.Ö.; methodology, T.K. and M.Ö.; software, M.D.; validation, T.K., M.Ö. and M.B.; formal analysis, T.K. and M.D.; investigation, T.K. and M.Ö.; resources, T.K. and M.A.; data curation, T.K., M.Ö. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K., M.Ö. and M.D.; writing—review and editing, T.K., M.D. and M.A.; visualization, T.K. M.Ö. and M.D.; supervision, T.K. and M.A.; project administration T.K. and M.A. . All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of ****** (Approval No. 1916246), and all study procedures were carried out in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Registry number NCT06080893).

Informed Consent Statement

The principal investigator obtained written informed consent from all patients prior to enrollment related to the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and researchers at Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine for their support, and the participants for their valuable contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification;

BMI, Body Mass Index;

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index;

COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease;

ES, Erythrocyte Suspension;

FCM, Ferric Carboxymaltose;

IMN, Intramedullary Nailing;

THA, Total Hip Arthroplasty.

References

- Gullberg, B.; Johnell, O.; Kanis, J. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporosis international, 1997, 7, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.J. Iron supplementation for anemia after hip fracture surgery: a randomized trial of 300 patients. JBJS, 2010, 92, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruson, K.I.; Aharonoff, G.B.; Egol, K.A.; Zuckerman, J.D.; Koval, K.J. The relationship between admission hemoglobin level and outcome after hip fracture. Journal of orthopaedic trauma 2002, 16, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koval, K.J.; Rosenberg, A.D.; Zuckerman, J.D.; Aharonoff, G.B.; Skovron, M.L.; Bernstein, R.L.; Chakka, M. Does blood transfusion increase the risk of infection after hip fracture? Journal of orthopaedic trauma 1997, 11, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, S.; Verbruggen, J.; Poeze, M. Effect of blood transfusion on survival after hip fracture surgery. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology 2018, 28, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.J.; Kim, J.H.; Han, S.-B.; Park, J.H.; Jang, W.Y. Allogeneic red blood cell transfusion is an independent risk factor for 1-year mortality in elderly patients undergoing femoral neck fracture surgery: retrospective study. Medicine 2020, 99, e21897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engoren, M.; Mitchell, E.; Perring, P.; Sferra, J. The effect of erythrocyte blood transfusions on survival after surgery for hip fracture. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2008, 65, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshi, A.; Lai, W.C.; Iglesias, B.C.; McPherson, E.J.; Zeegen, E.N.; Stavrakis, A.I.; Sassoon, A.A. Blood transfusion rates and predictors following geriatric hip fracture surgery. Hip international 2021, 31, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, Y.; Bal, G.; Liu, R.; Ashaia, W.; Sorial, R. A randomised controlled trial assessing the effect of tranexamic acid on post-operative blood transfusions in patient with intra-capsular hip fractures treated with hemi-or total hip arthroplasty. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery 2024, 144, 3095–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, M.; Borris, L.C.; Damsgaard, E.M. Postoperative blood transfusion strategy in frail, anemic elderly patients with hip fracture: the TRIFE randomized controlled trial. Acta orthopaedica 2015, 86, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-C.; Chang, L.-C.; Ho, C.-N.; Hsu, C.-W.; Yu, C.-H.; Wu, J.-Y.; Lin, C.-M.; Chen, I.-W. Efficacy of intravenous iron supplementation in reducing transfusion risk following cardiac surgery: an updated meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froessler, B.; Palm, P.; Weber, I.; Hodyl, N.A.; Singh, R.; Murphy, E.M. The important role for intravenous iron in perioperative patient blood management in major abdominal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. in Editor (Ed.)^(Eds.) Book The important role for intravenous iron in perioperative patient blood management in major abdominal surgery: a randomized controlled trial’ (LWW, 2016, edn.), pp.

- Kulnigg, S.; Stoinov, S.; Simanenkov, V.; Dudar, L.V.; Karnafel, W.; Garcia, L.C.; Sambuelli, A.M.; D'haens, G.; Gasche, C. A novel intravenous iron formulation for treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: the ferric carboxymaltose (FERINJECT®) randomized controlled trial. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2008, 103, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wyck, D.B.; Martens, M.G.; Seid, M.H.; Baker, J.B.; Mangione, A. Intravenous ferric carboxymaltose compared with oral iron in the treatment of postpartum anemia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2007, 110, (2 Part 1), 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Camaschella, C. Iron-deficiency anemia. New England journal of medicine 2015, 372, 1832–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, B.-H.; Lee, B.S.; Won, H.; Kim, H.-K.; Lee, Y.-K.; Koo, K.-H. Preoperative iron supplementation and restrictive transfusion strategy in hip fracture surgery. Clinics in orthopedic surgery 2019, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, J.; García-Erce, J.A.; Martínez, A.A.; Solano, V.M.; Molina, J.; Munoz, M. Role of parenteral iron in the management of anaemia in the elderly patient undergoing displaced subcapital hip fracture repair: preliminary data. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery 2005, 125, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabeu-Wittel, M.; Romero, M.; Ollero-Baturone, M.; Aparicio, R.; Murcia-Zaragoza, J.; Rincón-Gómez, M.; Monte-Secades, R.; Melero-Bascones, M.; Rosso, C.M.; Ruiz-Cantero, A. Ferric carboxymaltose with or without erythropoietin in anemic patients with hip fracture: a randomized clinical trial. Transfusion 2016, 56, 2199–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.L.; Stanworth, S.J.; Guyatt, G.; Valentine, S.; Dennis, J.; Bakhtary, S.; Cohn, C.S.; Dubon, A.; Grossman, B.J.; Gupta, G.K. Red blood cell transfusion: 2023 AABB international guidelines. Jama 2023, 330, 1892–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, B.; Kloesel, B.; Todd, M.M.; Cole, D.J.; Prielipp, R.C. The evolution, current value, and future of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System. Anesthesiology 2021, 135, 904–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of chronic diseases 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Muñoz, F.A.; Perez-Aznar, A.; Gonzalez-Parreño, S.; Sebastia-Forcada, E.; Mahiques-Segura, G.; Lizaur-Utrilla, A.; Vizcaya-Moreno, M.F. Change in 1-year mortality after hip fracture surgery over the last decade in a European population. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery 2023, 143, 4173–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.; Jang, E.J.; Jo, J.; Jo, J.G.; Nam, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, H.; Ryu, H.G. The association between hospital case volume and in-hospital and one-year mortality after hip fracture surgery: a population-based retrospective cohort study. The Bone & Joint Journal 2020, 102, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Huette, P.; Abou-Arab, O.; Djebara, A.-E.; Terrasi, B.; Beyls, C.; Guinot, P.-G.; Havet, E.; Dupont, H.; Lorne, E.; Ntouba, A. Risk factors and mortality of patients undergoing hip fracture surgery: a one-year follow-up study. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 9607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.; Gómez-Ramírez, S.; Cuenca, J.; García-Erce, J.A.; Iglesias-Aparicio, D.; Haman-Alcober, S.; Ariza, D.; Naveira, E. Very-short-term perioperative intravenous iron administration and postoperative outcome in major orthopedic surgery: a pooled analysis of observational data from 2547 patients. Transfusion 2014, 54, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahn, D.R. Anemia and patient blood management in hip and knee surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Anesthesiology 2010, 113, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qunibi, W.Y.; Martinez, C.; Smith, M.; Benjamin, J.; Mangione, A.; Roger, S.D. A randomized controlled trial comparing intravenous ferric carboxymaltose with oral iron for treatment of iron deficiency anaemia of non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2011, 26, 1599–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avni, T.; Bieber, A.; Grossman, A.; Green, H.; Leibovici, L.; Gafter-Gvili, A. The safety of intravenous iron preparations: systematic review and meta-analysis. in Editor (Ed.)^(Eds.) Book The safety of intravenous iron preparations: systematic review and meta-analysis’ (Elsevier, 2015, edn.), 12-23.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).