1. Introduction

The prevalence of preoperative anemia in patients undergoing major surgery is approximately 30% [

1]. Preoperative anemia, even when moderate, is independently associated with a higher number of complications and a greater likelihood of requiring a blood transfusion [

2][

3]. It is important to know which laboratory parameters can differentiate preoperative anemia from a deficiency disorder, a disorder of erythropoiesis, or the pathological destruction of red blood cells [

1][

4]. The diagnosis of nutritional anemia relies on biochemical markers of iron deficiency, and also takes into consideration chronic disorders involving sequestration and malabsorption of iron due to high hepcidin levels, for example [

5][

6]. It may also be necessary to detect other deficiencies, such as vitamin B12 and folic acid [

7][

8]. Clinicians now have access to both standard biochemical parameters and biomarkers of hypochromia - a direct indicator of functional iron deficiency that can show the rate of erythropoiesis in recent months9,10. According to the latest Enhanced Recovery After Adult Surgery (RICA, in its original Spanish acronym) statement, preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) should be above 13 g/dl, regardless of gender [

3]. Guidelines also recommend administering preoperative intravenous iron in patients in whom oral administration is contraindicated or when the time interval between diagnosis of anemia and performance of surgery is too short for oral iron to be effective [

9][

10][

11][

4][

12]. Oral iron is reserved for patients in whom mild or moderate iron deficiency has been diagnosed at least 6 weeks before surgery [

3][

13][

14][

15]. In surgery prehabilitation programs, a multidisciplinary team implements a series of preoperative measures and strategies aimed at reducing surgery-induced stress and organic dysfunction, reducing postoperative complications, optimizing anemia, reducing hospital stay, and expediting patient recovery [

3][

16][

17][

18]. In this context, we hypothesized that administering ferric carboxymaltose (FC) before surgery would optimize the patient’s status, reduce the number of intraoperative and postoperative blood transfusions, and thus reduce the risk of postoperative complications. The main aim of this study has been to analyze Hb, ferritin, transferrin, and transferrin saturation levels before administration of FC, at the time of inclusion on the surgical waiting list (SWL), and 30 days after surgery, and to compare postoperative complications in patients who received FC and those who did not. Our secondary aim was to compare hospital length of stay (days), ICU length of stay (days), need for hospital readmission, and need for blood transfusion between patients who received FC and those who did not.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted a prospective pre-post interventional study between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2022 at Infanta Cristina University Hospital in Parla (Madrid, Spain). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Instituto de Investigación Biomédica Segovia-Arana of Puerta de Hierro University Hospital (Protocol Code: ACT 15.18), on 19 October 2018) and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. To ensure anonymity and confidentiality, patient data were coded and stored in secure, password-protected databases accessible only to authorized research personnel, in compliance with Spanish legislation (Organic Law 3/2018 and RD 1090/2015).

The data used in the study were anonymous and collected by impartial, unpaid, volunteers.

2.2. Study Population

A total of 152 patients were included in the study: 96 recruited between 2020 and mid-2022 received FC (intervention group), and 56 recruited in 2019 did not (control group).

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

All study patients met the following inclusion criteria:

Age over 18 years; on the SWL;

Hemoglobine <13g/dL.

Referred for major elective surgery requiring hospital admission (e.g., oncologic resections such as mastectomy, colon resection, nephrectomy, hysterectomy), typically involving general anesthesia and moderate to high morbidity risk, capable of understanding and consenting to the study.

Physically and mentally able to complete assessments.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Variables

The following variables were recorded for analysis: gender (male, female); age; timing of preoperative FC therapy; Hb, ferritin, and transferrin levels before and 30 days after treatment; erythropoietin levels before FC treatment; weight; size; BMI; FC dose (500 mg, 1000 mg, 1500 mg, or 2000 mg); type of surgery (gastrectomy, hysterectomy, knee replacement, shoulder replacement, hip replacement, nephrectomy, cystectomy, mastectomy/lumpectomy, hemicolectomy/colectomy, cholecystectomy, herniorrhaphy); hospital length of stay; presence of surgical wound infection; presence of complications; type of complication (visceral perforation, chest pain, respiratory infection, hemorrhagic shock, paralytic ileus, hematoma, and bleeding); units of red blood cells transfused; need for ICU admission; ICU length of stay and need for readmission.

2.4. Intervention

All patients in the control group underwent surgery in 2019. At this time, intravenous iron administration was not included in the pre-operative optimization protocol and was not used as a blood-saving strategy. Therefore, patients in the control group did not receive FC before surgery, and laboratory tests were performed at the time of inclusion in the SWL and immediately before the intervention.

Patients in the intervention group underwent surgery from 2020 to mid-2022 and were managed according to the surgery prehabilitation protocol. Once the surgeon has included the patient on the SWL, they were evaluated and followed up by the prehabilitation nurse (no more than 72 hours in the case of cancer patients) together with the study internist. The protocol at this preoperative stage consists of a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment and an analysis of lab and nutritional parameters, which are optimized using targeted treatment. One of the lab parameters analyzed was Hb. Study patients with Hb < 13 g/dL received 500 mg, 1000 mg, 1500 mg or 2000 mg FC, depending on their levels of Hb, ferritin, transferrin saturation index, and weight. The lab test was repeated immediately before surgery or 30 days after administration of FC in order to determine whether Hb levels had improved with FC therapy.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out on SPSS v27 (IBM, Armonk, New York). All study variables were analyzed descriptively in order to determine their distribution. Categorical variables are described as percentage frequencies, and quantitative variables as mean plus standard deviation. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables, and the Student’s t-test was used in the case of quantitative variables.

3. Results

A total of 152 patients were included in the study: 96 recruited between 2020 and 2022 received FC (intervention group), and 56 recruited in 2019 did not (control group). Study patients were mostly women (n = 96, 60.5%), with a mean (SD) age of 63.91 (13.00) years. The sociodemographic variables analyzed did not differ significantly between groups (

Table A1).

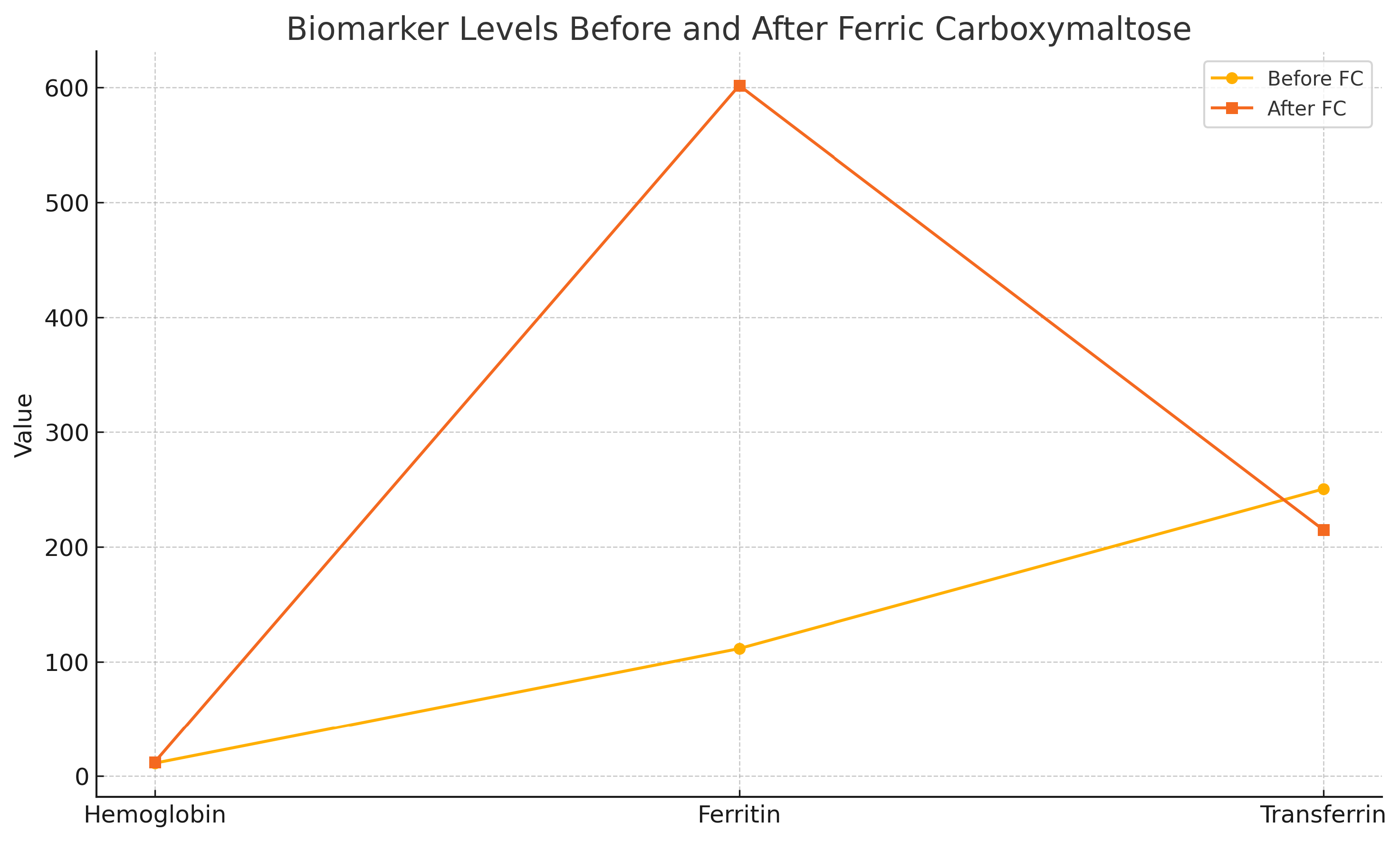

In the intervention group (n=96), laboratory parameters were analyzed before receiving FC and 30 days after. Valid parameters for comparison were obtained for Hb (96 patients), ferritin (64 patients), and transferrin (62 patients).

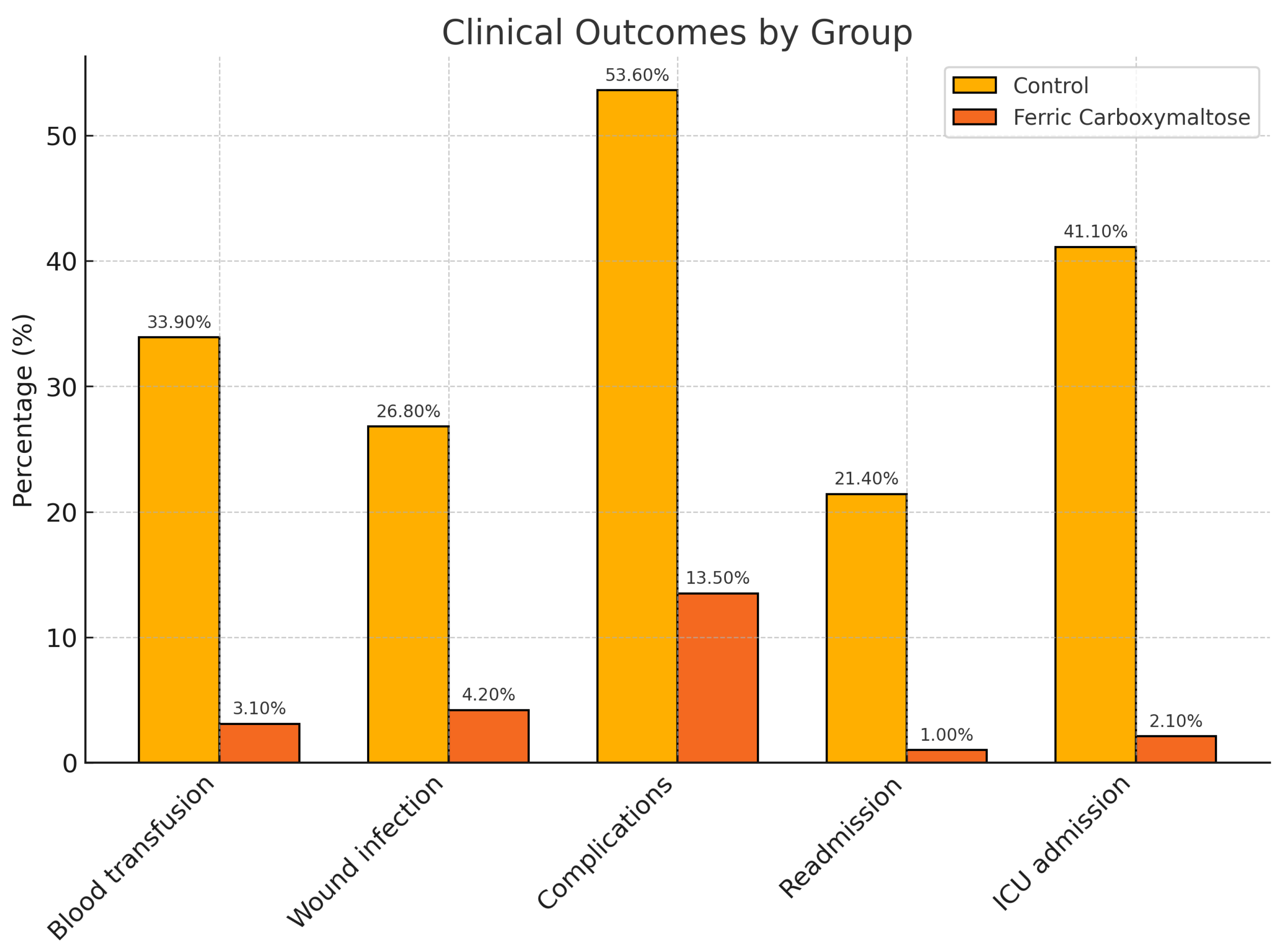

The mean hospital stay was 4.14 days in the intervention group vs. 9 days in the control group (p<0.001). Surgical wound infection occurred in 26.8% of patients in the control group vs 4.2% in the intervention group (OR 8.415 [2.63-26.91], p < 0.001). Blood transfusions were required in 3.1% of patients in the intervention group vs. 33.9% in the control group (OR 15.91[4.44-57.01], p<0.001). Regarding complications, 53.6% of patients in the control group presented some type of complication vs 13.5% in the intervention group (OR 7.36 [3.35- 16.16], p<0.001). Only 1% of patients in the intervention group required re-admission after surgery vs 21.4% in the control group (OR 25.90 [3.26 – 205], p<0.001). ICU care was required in 41.1% of patients in the control group vs 2.1% of patients in the intervention group (OR 32.75 [7.32-146.5], p<0.001)(

Figure 1). In terms of complications, significant differences between groups were observed in the case of abdominal collections (OR 7.57 (2.01-28.51], p=0.001), sepsis (OR 2.88 [2.3-3], p = 0.0035), and bleeding (OR 5 (1.48-16.80], p=0.005) (

Table A2).

Valid Hb values were obtained in 96 patients (63%) in the intervention group, in whom mean (SD) Hb prior to FC treatment was 11.33 g/dL (1.24) vs 12.34 g/dL (1.06) immediately before surgery (p = 0.038). Ferritin values were obtained in 64 patients (42%); pre-treatment values were 111.50 ng/ml vs 601.81 ng/ml immediately before surgery (p < 0.001). In the case of transferrin, pre-treatment values were 250.43 mg/dl vs 214.96 mg/dl after, p = 0.032. The TSI was only obtained in 34 patients (22.36%), and there was no significance between pre- and post-treatment values (mean [SD] 30.75% [57.61] and 35.19% [19.86], respectively, p=0.259)(

Figure 2).

EPO levels prior to treatment were obtained in 35 patients and showed a mean (SD) of 36.28 (55.73) mU/mL.

4. Discussion

Evidence has shown that a high proportion of surgical patients present preoperative anemia and are candidates for patient blood management and optimization strategies. Given the short supply of blood products, low hemoglobin levels need to be corrected before surgery in order to reduce the need for transfusion. The results of this study show that patients not treated with FC before surgery have a 15.91-fold higher risk of requiring blood transfusions.

Several studies have shown the benefit of optimizing patients with intravenous iron shortly before surgery when there is not enough time to administer an effective oral iron treatment [

9][

10][

12][

4]. On the basis of this recommendation, we performed a study in 96 patients receiving FC prior to surgery. The mean duration of FC treatment prior to surgery was 19.64 days; however, this period varied considerably because some surgeries could not be postponed given their characteristics. Our findings show that the administration of FC over this time period improves hemoglobin, ferritin, transferrin and transferrin saturation levels in patients undergoing prehabilitation, and that FC can also be administered far closer to the date of surgery. However, hemoglobin values in patients receiving FC less than 7 days before surgery, on average, showed a more modest increase (mean [SD] 10.96 [0.79] mg/dL) compared to other patients in the intervention group. Therefore, it would be highly recommendable to delay non-urgent surgeries in order to optimize patients adequately and thus minimize complications[

19].

Given the different types of anemia (iron deficiency, hemolytic, or anemia of chronic disease)[

5], we also analyzed erythropoietin levels in 34 patients (22.87%) in order to understand why FC administration did not achieve the expected results in some cases. Measuring blood levels of erythropoietin or hepcidin allowed us to determine which patients were likely to respond to a particular dose of FC in the absence of bone marrow dysfunction. These values should also be determined in subsequent studies.

In line with current evidence, our study demonstrates that the early correction of perioperative anemia using intravenous ferric carboxymaltose improves relevant clinical outcomes, including reduced transfusion rates, surgical site infections, and hospital stay. These findings are supported by the recently published national consensus document on the management of perioperative anemia in Spain (Muñoz et al., 2024)[

4], which emphasizes that perioperative anemia affects up to one-third of surgical patients and independently increases postoperative morbidity and mortality. The consensus establishes a unified diagnostic threshold of hemoglobin <13 g/dL for both sexes, which reinforces the appropriateness of our inclusion criteria. Moreover, it recommends a broader diagnostic panel that includes C-reactive protein (CRP) and reticulocyte hemoglobin content (CHr), in addition to conventional iron parameters, to better characterize anemia subtypes and guide iron therapy decisions. While our protocol already includes ferritin and transferrin measurements, future protocols may benefit from incorporating these additional biomarkers to refine patient stratification.

The Spanish consensus also highlights logistical and organizational barriers that currently limit the implementation of structured perioperative anemia management protocols in many hospitals. Our study shows that integration of intravenous iron therapy into a multidisciplinary prehabilitation program is not only feasible, but can also be delivered effectively within the limited time window available in oncologic surgery settings. Finally, the implementation of standardized clinical algorithms—such as those proposed in the consensus document—may help reduce variability in practice, improve efficiency, and support a more equitable and cost-effective model of perioperative care[

14][

4].

Regarding surgical wound infections and other postoperative complications, our results show that these and mortality rates are reduced in patients treated with FC sufficiently in advance of surgery - a finding also reported by other authors [

2][

11]. Patients in the control group (no preoperative FC) had a 7.36-fold higher risk of presenting post-surgical complications, particularly abdominal collections, which were significantly more frequent in patients not treated with FC and could be related to surgical wound complications. Complications such as sepsis, meanwhile, are usually associated with nosocomial infection acquired during a lengthy hospital stay and are favored by surgery-related immunosuppression. Finally, bleeding complications are directly related to preoperative anemia (low hemoglobin levels) which, if not corrected, may be aggravated by surgery-related blood loss and cause bleeding complications derived from hypovolemia. The results of our study show that patients not treated with FC before surgery have a 2.88-fold higher risk of developing septic complications, a 7.57-fold higher risk of presenting abdominal collections, and a 5-fold higher risk of bleeding complications. The relationship between anemia and surgical wound infection, however, is not described in the literature and we were unable to find any evidence of its pathophysiology. Even so, incidence of surgical wound infection was lower in patients in the intervention group vs the control group, and this, in turn, improves 30-day mortality rates, as described by Schack et al.[

2].

Regarding hospital stay, ICU admission and readmission’s, ICU length of stay was shorter in the intervention group vs controls, which also reduced the risk of ICU-related complications. Re-admissions were also less frequent in patients receiving FC, due to a lower rate of nosocomial infections and complications that cannot be treated at the primary care level or by the hospital’s outpatient department or nurse practitioners. Our findings also show that patients who are not treated with intravenous FC before surgery have a 25.90-fold higher risk of being readmitted and a 32.75-fold higher risk of requiring admission to the ICU.

According to Banerjee et al., administering FC to optimize hemoglobin levels prior to surgery is a cost-effective measure that saves approximately EUR 831.00 per transfusion and EUR 405.00 per unit of red blood cells. The authors concluded that FC was less expensive than other blood management modalities[

12] and it is consistent with the cost-saving data in surgical prehabilitation reported by Mudarra et al [

20]

5. Conclusions

FC rapidly and effectively boosts hemoglobin levels in anemic patients, reduces the need for blood transfusions and their corresponding costs, decreases the rate of surgical wound infections, reduces the incidence of post-surgical complications, hospital and ICU stays, and the rate of hospital readmissions.

Delaying surgery in order to optimize the patient’s Hb status could help reduce postoperative complications.

However, further studies are needed to analyze whether delaying surgery would be detrimental to the patient’s prognosis.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, although the prospective design enhances data quality, the use of a historical control group may introduce potential biases related to changes in surgical practices or perioperative management over time. Second, the sample size, while sufficient to detect significant differences in primary outcomes, may limit the generalizability of the results to broader surgical populations, especially in non-oncologic or emergency settings. Third, biomarker data (e.g., transferrin saturation index, erythropoietin, hepcidin) were only available for a subset of patients, which may limit the depth of interpretation regarding iron metabolism and treatment response. In addition, the absence of long-term follow-up prevents conclusions about delayed complications, recurrence rates, or survival.

Future research should focus on randomized controlled trials comparing different intravenous iron formulations and dosing strategies, ideally stratified by baseline inflammation status, type of anemia, and timing of administration. Moreover, integrating broader biomarker panels—such as CRP, CHr, and hepcidin—may allow for a more tailored and pathophysiologically guided approach to anemia management. Finally, cost-effectiveness analyses across different healthcare systems would help support policy-level decisions regarding the widespread implementation of perioperative anemia optimization programs.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, N.M. and F.G.; methodology, N.M.; software, N.M.; validation, F.G. and N.M.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, F.G.; resources, F.G.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.; writing—review and editing, F.G.; visualization, F.G.; supervision, F.G.; project administration, F.G.; funding acquisition, N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded through the funds of the IDIPHISA Foundation (Research Institute of the Puerta de Hierro University Hospital), with which the Infanta Cristina University Hospital in Madrid was affiliated, grant number [XXX].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee Segovia—Arana Biomedical Research Institute of Universitary Hospital Puerta de Hierro (protocol code ACT 15.18) in 19 October 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In this section you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| FC |

Ferric carboxymaltose |

| Hb |

Hemoglobine |

| RICA |

Recuperación intensificada en la cirugía del Adulto |

| SWL |

Surgical waiting List |

| TSI |

Transferrin saturation index |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sociodemographic variables comparing intervention and control group

Table A1.

Sociodemographic variables comparing intervention and control group

| |

|

IV Iron

(n = 96) |

No Iron

(n = 56) |

Total

(n=152) |

p |

| Gender, n(%) |

Men |

36 (37.50) |

24 (42.90) |

60 (39.50) |

0.515 |

| |

Women |

60 (62.50) |

32 (57.10) |

92 (60.50) |

|

| Age (years), mean (SD) |

|

62.22 (14.11) |

66.80 (10.35) |

63.91 (13.00) |

0.036 |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) |

|

159.70 (8.54) |

160.50 (9.19) |

159.99 (8.76) |

0.591 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) |

|

72.54 (16.02) |

71.36 (16.2) |

72.10 (16.06) |

0.664 |

| BMI, mean (SD) |

|

28.61 (5.87) |

27.83 (5.38) |

28.32 (5.69) |

0.420 |

Table A2.

Clinical variables comparing the intervention and control groups

Table A2.

Clinical variables comparing the intervention and control groups

| |

|

Iron

(n = 96) |

No Iron

(n = 56) |

Total

(n=152) |

p |

| Dose of Ferric Carboximaltose, n (%) |

500 mg |

37 (38.5) |

0 (0.00) |

37 (38.50) |

|

| |

1000 mg |

37 (38.50) |

0 (0.00) |

37 (38.50) |

|

| |

1500 mg |

20 (20.80) |

0 (0.00) |

20 (20.80) |

|

| |

2000 mg |

2 (2.10) |

0 (0.00) |

2 (2.10) |

|

| Type of surgery, n (%) |

Gastrectomy |

2 (2.10) |

10 (17.90) |

12 (7.90) |

<0.001 |

| |

Hysterectomy |

14 (14.60) |

5 (8.90) |

19 (12.50) |

|

| |

Hip replacement |

10 (10.40) |

0 (0.00) |

10 (6.60) |

|

| |

Shoulder replacement |

1 (1.00) |

0 (0.00) |

1 (0.70) |

|

| |

Nephrectomy |

4 (4.20) |

3 (5.40) |

7 (4.60) |

|

| |

Cystectomy |

1 (1.00) |

0 (0.00) |

1 (0.70) |

|

| |

Mastectomy / lumpectomy |

35 (36.50) |

0 (0.00) |

35 (23.00) |

|

| |

Colectomy |

23 (24.00) |

38 (67.90) |

61 (40.10) |

|

| |

Cholecystectomy |

1 (1.00) |

0 (0.00) |

1 (0.70) |

|

| |

Hiatus hernia |

5 (5.20) |

0 (0.00) |

5 (3.30) |

|

| Hospital stay (days), mean (SD) |

|

4.14 (3.44) |

9 (6.45) |

5.94 (5.31) |

<0.001 |

| Surgical wound infection, n (%) |

Yes |

4 (4.20) |

15 (26.80) |

19 (12.50) |

<0.001 |

| |

No |

92 (95.80) |

41 (73.20) |

133 (87.50) |

|

| Blood transfusion, n (%) |

Yes |

3 (3.10) |

19 (33.90) |

22 (14.50) |

<0.001 |

| |

No |

93 (96.90) |

37 (66.10) |

130 (85.50) |

|

| RBC units, mean (SD) |

|

0.05 (0.30) |

0.91 (1.13) |

0.24 (0.68) |

<0.001 |

| Complications, n (%) |

Yes |

13 (13.50) |

30 (53.60) |

43 (28.30) |

<0.001 |

| |

No |

83 (86.50) |

26 (46.40) |

109 (81.70) |

|

| Sepsis, n (%) |

Yes |

0 (0.00) |

5 (8.90) |

5 (3.30) |

p=0.003 |

| |

No |

96 (100.00) |

51 (91.10) |

147 (96.70) |

|

| Pleural effusion, n (%) |

Yes |

0 (0.00) |

5 (8.90) |

5 (3.33) |

p=0.003 |

| |

No |

96 (100.00) |

51 (91.10) |

147 (96.70) |

|

| Respiratory infection, n (%) |

Yes |

0 (0.00) |

2 (3.60) |

2 (1.30) |

p=0.062 |

| |

No |

96 (100.00) |

54 (96.40) |

150 (98.70 |

|

| Abdominal collection, n (%) |

Yes |

3 (3.1) |

11 (19.60) |

14 (9.20) |

p=0.001 |

| |

No |

93 (96.90) |

45 (80.40) |

138 (90.80) |

|

| Paralytic ileum, n (%) |

Yes |

4 (4.20) |

5 (8.90) |

9 (5.90) |

p=0.230 |

| |

No |

92 (95.80) |

51 (91.10) |

143 (94.10) |

|

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) |

Yes |

0 (0.00) |

1 (1.80) |

1 (0.70) |

p=0.189 |

| |

No |

96 (100.00) |

54 (96.40) |

150 (98.70) |

|

| Bleeding, n (%) |

Yes |

4 (4.20) |

10 (17.90) |

14 (9.20) |

p=0.005 |

| |

No |

92 (95.80) |

46 (82.10) |

138 (90.80) |

|

| Re-admission, n (%) |

Yes |

1 (1.00) |

12 (21.40) |

13 (8.60) |

<0.001 |

| |

No |

95 (99.00) |

44 (78.60) |

139 (91.40) |

|

| ICU admission, n (%) |

Yes |

2 (2.10) |

23 (41.10) |

25 (16.40) |

<0.001 |

| |

No |

94 (97.90) |

33 (58.90) |

127 (83.60) |

|

| ICU stay (days), mean (SD) |

|

0.04 (0.28) |

0.91 (1.13) |

0.36 (0.83) |

<0.001 |

Appendix B

All appendix sections must be cited in the main text. In the appendices, Figures, Tables, etc. should be labeled, starting with “A”—e.g., Figure A1, Figure A2, etc.

References

- Bisbe Vives, E. Tratamiento de la anemia preoperatoria en cirugía ortopédica mayor. Revista Española de Anestesiología y Reanimación 2015, 62, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schack, A.; Berkfors, A.A.; Ekeloef, S.; Gögenur, I.; Burcharth, J. The Effect of Perioperative Iron Therapy in Acute Major Non-cardiac Surgery on Allogenic Blood Transfusion and Postoperative Haemoglobin Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World Journal of Surgery 2019, 43, 1677–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presentada la VIA RICA | Grupo Español de Rehabilitación Multimodal.

- Muñoz, M.; Aragón, S.; Ballesteros, M.; Bisbe-Vives, E.; Jericó, C.; Llamas-Sillero, P.; Meijide-Míguez, H.; Rayó-Martin, E.; Rodríguez-Suárez, M. Resumen ejecutivo del documento de consenso sobre el manejo de la anemia perioperatoria en España. Revista Clínica Española 2024, 224, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charavía, M.C.; Mazo, E.M. Anemias carenciales y anemia de los trastornos crónicos. Medicine - Programa de Formación Médica Continuada Acreditado 2020, 13, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilreath, J.A.; Rodgers, G.M. How I treat cancer-associated anemia. Blood 2020, 136, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eussen, S.J.P.M.; Ferry, M.; Hininger, I.; Haller, J.; Matthys, C.; Dirren, H. Five year changes in mental health and associations with vitamin B12/folate status of elderly Europeans. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 2002, 6, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nalder, L.; Zheng, B.; Chiandet, G.; Middleton, L.; De Jager, C.A. Vitamin B12 and Folate Status in Cognitively Healthy Older Adults and Associations with Cognitive Performance. The Journal of nutrition, health and aging 2021, 25, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- on behalf of the Colon Cancer Study Group. ; Calleja, J.L.; Delgado, S.; Del Val, A.; Hervás, A.; Larraona, J.L.; Terán, Á.; Cucala, M.; Mearin, F. Ferric carboxymaltose reduces transfusions and hospital stay in patients with colon cancer and anemia. International Journal of Colorectal Disease 2016, 31, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froessler, B.; Palm, P.; Weber, I.; Hodyl, N.A.; Singh, R.; Murphy, E.M. The Important Role for Intravenous Iron in Perioperative Patient Blood Management in Major Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of Surgery 2016, 264, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Erce, J.; Altés, A.; López Rubio, M.; Remacha, A.; De La O Abío, M.; Benéitez, D.; De La Iglesia, S.; Dolores De La Maya, M.; Flores, E.; Pérez, G.; et al. Manejo del déficit de hierro en distintas situaciones clínicas y papel del hierro intravenoso: recomendaciones del Grupo Español de Eritropatología de la SEHH. Revista Clínica Española 2020, 220, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; McCormack, S. Intravenous Iron Preparations for Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness, and Guidelines; CADTH Rapid Response Reports, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa (ON), 2019.

- Laso-Morales, M.; Jericó, C.; Gómez-Ramírez, S.; Castellví, J.; Viso, L.; Roig-Martínez, I.; Pontes, C.; Muñoz, M. Preoperative management of colorectal cancer–induced iron deficiency anemia in clinical practice: data from a large observational cohort. Transfusion 2017, 57, 3040–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.; Acheson, A.G.; Bisbe, E.; Butcher, A.; Gómez-Ramírez, S.; Khalafallah, A.A.; Kehlet, H.; Kietaibl, S.; Liumbruno, G.M.; Meybohm, P.; et al. An international consensus statement on the management of postoperative anaemia after major surgical procedures. Anaesthesia 2018, 73, 1418–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okam, M.M.; Koch, T.A.; Tran, M.H. Iron Supplementation, Response in Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Analysis of Five Trials. The American Journal of Medicine 2017, 130, 991.e1–991.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, V.A.; Hazuda, H.P.; Cornell, J.E.; Pederson, T.; Bradshaw, P.T.; Mulrow, C.D.; Page, C.P. Functional independence after major abdominal surgery in the elderly. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2004, 199, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillis, C.; Fenton, T.R.; Sajobi, T.T.; Minnella, E.M.; Awasthi, R.; Loiselle, S.È.; Liberman, A.S.; Stein, B.; Charlebois, P.; Carli, F. Trimodal prehabilitation for colorectal surgery attenuates post-surgical losses in lean body mass: A pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Nutrition 2019, 38, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.H.; Cajas-Monson, L.C.; Eisenstein, S.; Parry, L.; Cosman, B.; Ramamoorthy, S. Preoperative malnutrition assessments as predictors of postoperative mortality and morbidity in colorectal cancer: an analysis of ACS-NSQIP. Nutrition Journal 2015, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, G.; Mehta, R.; McVeagh, K.; Egan, M. The Effects of Intravenous Iron Infusion on Preoperative Hemoglobin Concentration in Iron Deficiency Anemia: Retrospective Observational Study. Interactive Journal of Medical Research 2022, 11, e31082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudarra-García, N.; Roque-Rojas, F.; Izquierdo-Izquierdo, V.; García-Sánchez, F.J. Prehabilitation in Major Surgery: An Evaluation of Cost Savings in a Tertiary Hospital. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).