Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Microplastics in Agroecosystems

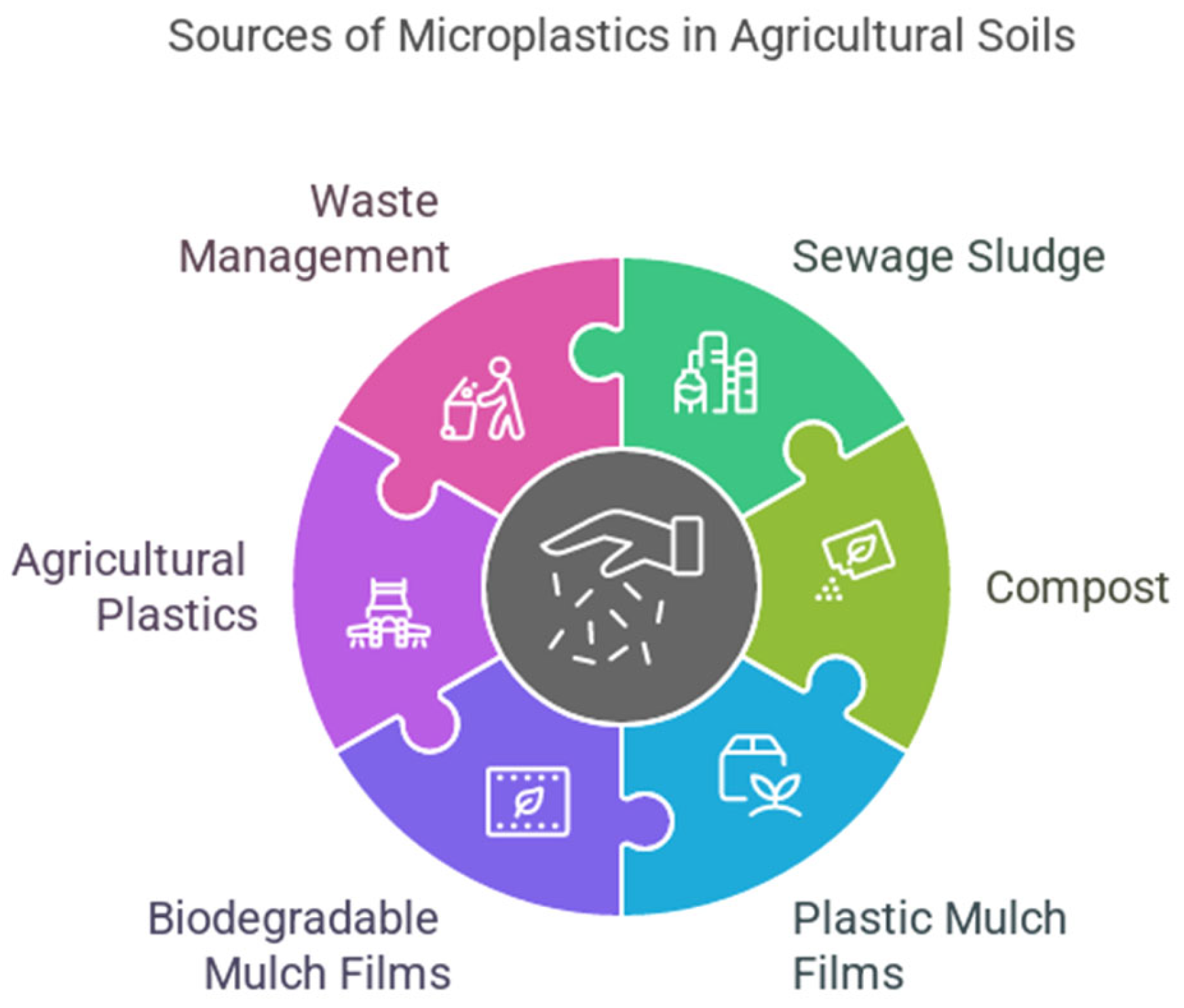

3.1. Sources of Microplastics in the Soil

3.1.1. Agriculture as a Source of Micro and Nanoplastics

3.1.2. Waste Management and Atmospheric Deposits as a Source of Micro and Nano Plastics

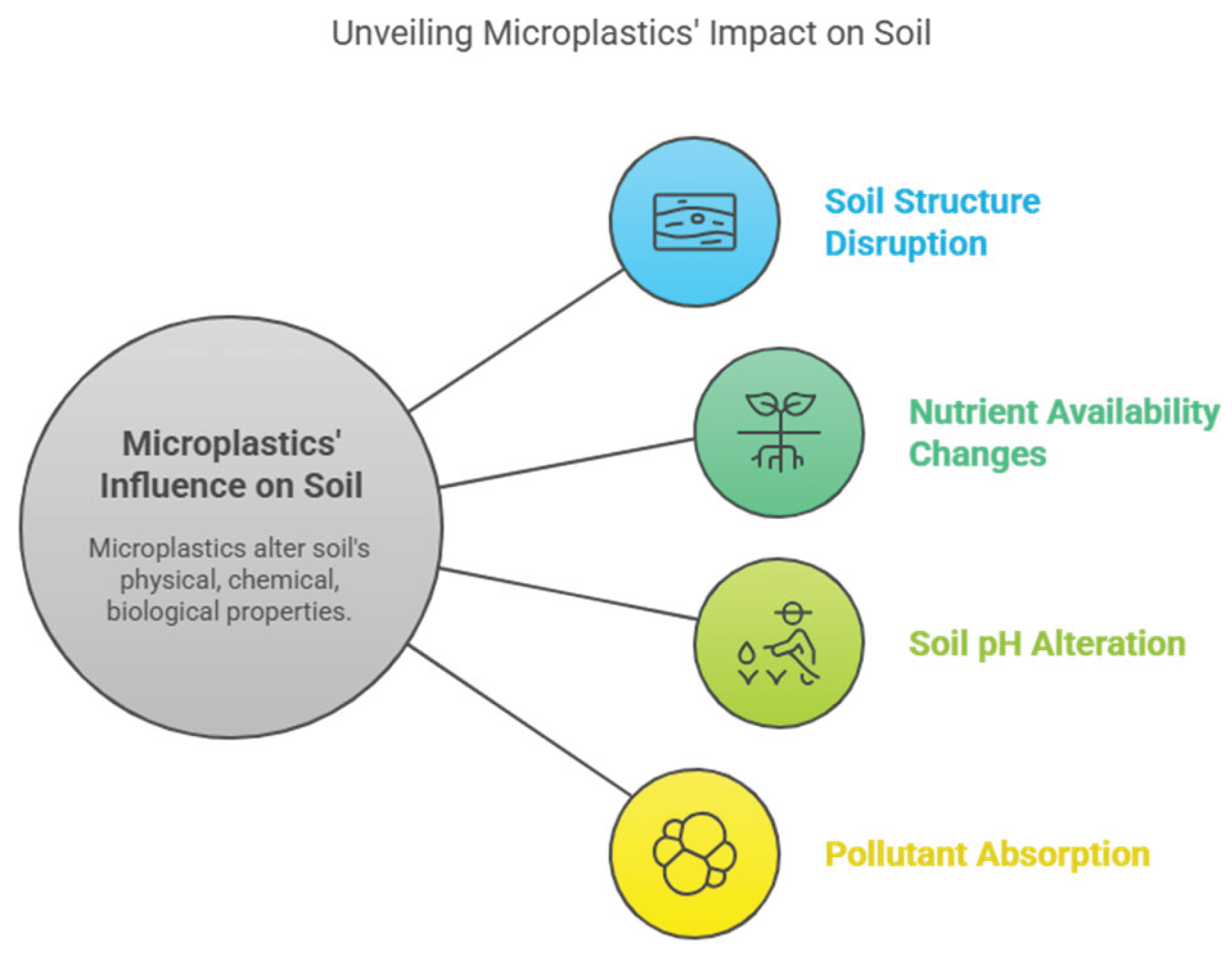

3.2. Influence of Microplastics on Soil Characteristics

4. Soil - Plant System

4.1. Mechanisms of Microplastics Uptake

4.2. Reaction of Plants to Microplastics and Nanoplastics

4.2.1. The Influence of Micro- and Nano -Plastics on Seed Germination

4.2.2. Changes in Morphological Features

4.2.3. Changes in Physiological and Biochemical Processes

4.3. Microplastics in Vegetables

4.3.1. Type and Form of Microplastics and Nanoplastic in Vegetables

4.3.2. Mechanisms of Uptake of Micro and Nanoplastics by Vegetables

4.3.3. Conditions Affecting the Adoption of Microplastics

4.3.4. The Impact of Microplastics and Nanoplastics on Vegetables

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pastor, K., Isić, B., Horvat, M., Horvat, Z., Ilić, M., Ačanski, M., Marković, M. Omnipresence of plastics: A Review of the Microplastic Sources and Detection Methods. Journal of Faculty of Civil Engineering, 2021, 39, 29-43. [CrossRef]

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com (accessed on 01/04/2025).

- Yan, H., Cordier, M., Uehara, T. Future Projections of Global Plastic Pollution: Scenario Analyses and Policy Implications. Sustainability, 2024, 16, 643. [CrossRef]

- Pottinger, A. S., Geyer, R., Biyani, N., Martinez, C., Nathan, N., Morse, M. R., Liu, C., Hu, S., de Bruyn, M., Boettiger, C., Baker, E. J., McCauley, D. J. Pathways to reduce global plastic waste mismanagement and greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Science, 2024, 386(6726), 1168-1173. [CrossRef]

- Lazăr, N. N., Calmuc, M., Milea, S. A., Georgescu, P. L., Iticescu, C. Micro and nano plastics in fruits and vegetables: A review. Heliyon, 2024, 10, e28291. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, J. T., Inobeme, A., B. O. Adetuyi, B. O., Adetunji, C. O., Popoola, O. A., Olaitan, F. Y., Akinbo, O., Shahnawaz, M., Oyewole, O. A., K.I.T., E., Yerima, M. B. General Introduction of Microplastic: Uses, Types, and Generation. In: Microplastic Pollution, (Ed) Mohd. Shahnawaz, M., Adetunji, C .O., Dar, M. A., Zhu, D. Springer, Singapore, 2024, pp. 3-21. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Liu, X., Li, Y., Powell, T., Wang, X., Wang, G., Zhang, P. Microplastics as contaminants in the soil environment: A mini-review. Sci. Total Environ., 2019, 691, 848-857. [CrossRef]

- Pinlova, B., Nowack, B. From cracks to secondary microplastics - surface characterization of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) during weathering. Chemosphere, 2024, 141305-141305. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Lei, C., Xu, J., Li, R. Foliar uptake and leaf-to-root translocation of nanoplastics with different coating charge in maize plants. J. Hazard. Mater., 2021, 416, 125854 . [CrossRef]

- Chia, R. W., Lee, J. Y., Cha, J., Çelen-Erdem, İ. A comparative study of soil microplastic pollution sources: a review. Environ. Pollut. Bioaviolab., 2023, 35(1), 2280526 . [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. R., Tarafder, M. M. A., Priti, M. S., Haque, M. A. Micro-plastics in soil environment: A review. Bangladesh J. Nuc. Agri., 2024, 38 (1):1-19. [CrossRef]

- Nath, S., Enerijiofi, K. E., Astapati, A.D., Guha, A. Microplastics and nanoplastics in soil: Sources, impacts, and solutions for soil health and environmental sustainability. J. Environ. Qual., 2024, 53 (6), 1048-1072. [CrossRef]

- Dogra, K., Kumar, M., Bahukhandi, K. D., Zang, J. Traversing the prevalence of microplastics in soil-agro ecosystems: Origin, occurrence, and pollutants synergies. J. Cont. Hyd., 2024, 266, 104398-104398. https://doiorg/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2024.104398.

- Zhang, L., García-Perez, P., Munoz-Palazon, B., Gonzalez-Martinez, A., Lucini, L., Rodriguez-Sanchez, A. A metabolomics perspective on the effect of environmental micro and nanoplastics on living organisms: A review. Sci.Total Environ., 2024, 932, 172915. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Yu, L., Li, Y., Han, B., Zhang, J., Tao, S., Liu, W. Status, characteristics, and ecological risks of microplastics in farmland surface soils cultivated with different crops across mainland China. Sci.Total Environ., 2023, 897, 165331. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Feng, Z., Ghani, M. I., Wang, Q., Zeng, L., Yang, X., Cernava, T. Co-exposure to microplastics and soil pollutants significantly exacerbates toxicity to crops: Insights from a global meta and machine-learning analysis. Sci. Total Environ., 2024, 954, 176490. [CrossRef]

- Chadegani, A.; Salehi, H.; Yunus, M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ebrahim, N. A comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of Science and Scopus databases. Asian Soc. Sci., 2013, 9, 18–26. http://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n5p18.

- He, D., Luo, Y., Lu, S., Liu, M., Song, Y., Lei, L. Microplastics in soils: Analytical methods, pollution characteristics and ecological risks. TRAC, 2018, 109, 163-172. [CrossRef]

- Paganini, E., Silva, R. B., Roder, L. R., Guerrini, I. A., Capra, G. F., Grilli, E., Ganga, A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Sustainable Impact of Sewage Sludge Application on Soil Organic Matter and Nutrient Content. Sustainability, 2024, 16(22), 9865-9865. https://doi.or/10.3390/su16229865.

- Rodrigues, M. Â., Sawimbo, A., da Silva, J. M., Correia, C. M., Arrobas, M. Sewage Sludge Increased Lettuce Yields by Releasing Valuable Nutrients While Keeping Heavy Metals in Soil and Plants at Levels Well below International Legislative Limits. Horticulturae, 2024, 10(7), 706. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S. M., Gameh, M. A., El Wahab, M. M. A., El Desoky, M. A., Negim, O. I. Environmental negative and positive impacts of treated sewage water on the soil: A case study from Sohag Governorate, Egypt. Egypt. Sugar J., 2022, 19(0):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A. M. S., Faria, R. T., Saran, L. M., Santos, G. O., Dantas, G. F., Coelho, A. P. Impact of treated sewage effluent on soil fertility, salinization, and heavy metal content. Bragantia, 2022, 81, e0222. [CrossRef]

- Tiruneh, A. T., Nkambule, S. J., Murye, A. F. Assessment of the benefits and risks of sewage sludge application as soil amendment for agriculture in Eswatini. Afri. J. Food Agricul. Nutri. Develop., 2024, 24(8), 24229-24260. [CrossRef]

- Rydgård, M., Bairaktar., A., Thelin, G., Bruun, S. Application of untreated versus pyrolysed sewage sludge in agriculture: A Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod., 2024, 454, 142249 . [CrossRef]

- Haider, I., Ali, M. A., Sanaullah, M., Ahmed, N., Hussain, S., Shakeel, M. T., Naqvi, S. A. H., Dar, J. S., Moustafa, M., Alshaharni, M.O. Unlocking the secrets of soil microbes: How decades-long contamination and heavy metals accumulation from sewage water and industrial effluents shape soil biological health. Chemosphere, 2023, 342, 140193-140193. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Li, Y., Jiang, L., Chen, X., Zhao, Y., Shi, W., Xing, Z. From organic fertiliser to the soils: What happens to the microplastics? A critical review. Sci. Total Environ., 2024, 919, 170217-170217. [CrossRef]

- Santini, G., Acconcia, S., Napoletano, M., Memoli, V., Santorufo, L., Maisto, G. Unbiodegradable and biodegradable plastic sheets modify the soil properties after six months since their applications. Environ. Pollut., 2022, 308, 119608. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Zou, G., Zuo, Q., Li, S., Bao, Z., Jin, T., Liu, D., Du, L. It is still too early to promote biodegradable mulch film on a large scale: A bibliometric analysis. Environ. Technol. Innov., 2022, 27, 102487. [CrossRef]

- Santini, G., Castiglia, D., Perrotta, M. M., Landi. S., Maisto, G., Esposito, S. Plastic in the Environment: A Modern Type of Abiotic Stress for Plant Physiology. Plants, 2023, 12(21), 3717. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N., Aqeel, M., Noman, A., Rizvi, Z. F. Impact of plastic mulching as a major source of microplastics in agroecosystems. J. Hazard. Mater., 2023, 445, 130455. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S., Chang, H., Zheng, L., Yan, Q., Pfleger, B.F., Klier, J., Nelson, K., Majumder, E.L., Huber, G.W. A Review of Biodegradable Plastics: Chemistry, Applications, Properties, and Future Research Needs. ACS Chem. Rev., 2023, 23, 9915–9939. [CrossRef]

- Qin, M., Chen, C., Song, B., Shen, M., Cao, W., Yang, H., Zeng, G., Gong, J. A review of biodegradable plastics to biodegradable microplastics: Another ecological threat to soil environments? J. Clean. Prod., 2021, 312, 127816. [CrossRef]

- Zytowski, E., Mollavali, M., Baldermann, S. Uptake and translocation of nanoplastics in mono and dicot vegetables. Plant Cell Environ., 2025, 48(1), 134-148. [CrossRef]

- Theofanidis, S. A., Delikonstantis, E., Yfanti, V. - L., Galvita, V. V., Lemonidou, A. A., Van Geem, K. An electricity-powered future for mixed plastic waste chemical recycling. Waste Manag., 2025, 193, 155–170. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Li, Y., Liu, S., Junaid, M., Wang, J. Effects of micro(nano)plastics on higher plants and the rhizosphere environment. Sci. Total Environ., 2022, 807, 150841. [CrossRef]

- Mou, X., Zhu, H., Dai, R., Lu, L., Qi, S., Zhu, M., Long, Y., Ma, N., Chen, C., Shentu, J. Potential impact and mechanism of aged polyethylene microplastics on nitrogen assimilation of Lactuca sativa L. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf., 2025, 291,117862. https://doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2025.117862.

- Chen, J. Y., Li, Y., Liang, X., Lu, S., Zhang, Y., Han, Z, Gao, B., Sun, K. Effects of microplastics on soil carbon pool and terrestrial plant performance. Carbon Res., 2024, 3(1), 37. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Liu, W., Zeb, A., Wang, L., Mo, F, Shi, R., Sun, Y., Wang, F. Biodegradable Microplastic-Driven Change in Soil pH Affects Soybean Rhizosphere Microbial N Transformation Processes. J. Agric. Food Chem., 2024, 72(30), 16674–16686. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., Wang, F., Huang, W., Liu, Y. Response of soil biochemical properties and ecosystem function to microplastics pollution. Sci. Rep., 2024, 14:28328. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Wang, X., Song, N. Polyethylene microplastics increase cadmium uptake in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) by altering the soil microenvironment. Sci. Total Environ., 2021, 784, 147133. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y., Li, X., Wei, Z., Zhang, T., Wang, H., Huang, X., Tang, S. Recent Advances on Multilevel Effects of Micro(Nano)Plastics and Coexisting Pollutants on Terrestrial Soil-Plants System. Sustainability, 2023, 15(5):4504-4504. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Y., Fan, P., Xi, B., Tan, W. Metal type and aggregate microenvironment govern the response sequence of speciation transformation of different heavy metals to microplastics in soil. Sci.Total Environ., 2021, 752:141956. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Luo, Y.; Li, R.; Zhou, Q.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Yin, N.; Yang, J.; Tu, C.; Zhang, Y. Effective uptake of submicrometre plastics by crop plants via a crack-entry mode. Nat. Sustain, 2020, 3, 929–937. [CrossRef]

- Lian, J., Liu, W., Meng, L., Wu, J., Chao, L., Zeb, A., Sun, Y. Foliar-applied polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs) reduce the growth and nutritional quality of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Environ. Pollut., 2021, 280, 116978. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Li, L., Feng, Y., Li, R., Yang, J., Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M., Tu, C. Quantitative tracing of uptake and transport of submicrometre plastics in crop plants using lanthanide chelates as a dual-functional tracer. Nat. Nanotechnol., 2022, 17, 424–431. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, Y. M., Lehnert, T., Linck, L. T., Lehmann, A., Rillig, M. C. Microplastic shape, polymer type, and concentration affect soil properties and plant biomass. Front. Plant Sci., 2021, 12, 616645. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D., Shi. Z., Shan, X., Yang, S. Y., Zhang. Y., Guo, X. M. Insights into growth-affecting effect of nanomaterials: Using metabolomics and transcriptomics to reveal the molecular mechanisms of cucumber leaves upon exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs). Soc. Sci. Res. Net., 2023, 866, 161247 - 161247. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Feng, X., Liu, Y., Adams, C. A., Sun, Y., Zhang, S. Micro(nano)plastics and terrestrial plants: Up-to-date knowledge on uptake, translocation, and phytotoxicity. Resour. Conserv. Recycl, 2022, 185, 106503-106503. https://doi.org10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106503.

- Qiuge, Z., Mengsai, Z., Fansong, M., Yongli, X., Wei, D., Yaning, L. Effect of polystyrene microplastics on rice seed germination and antioxidant enzyme activity. Toxics, 2021, 9, 179. [CrossRef]

- De Silva, Y. S. K., Rajagopalan, U. M., Kadono, H., Li, D. Effects of microplastics on lentil (Lens culinaris) seed germination and seedling growth. Chemosphere, 2022, 303, 135162. [CrossRef]

- Hu, M., Huang, Y., Liu, L., Ren, L., Li, C., Yang, R., Zhang, Y. The effects of Micro Nano-plastics exposure on plants and their toxic mechanisms: A review from multi-omics perspectives.. J. Hazard. Mater, 2023, 465, 133279–133279 . [CrossRef]

- Mészáros, E., Bodor, A., Kovács, E., Papp, S., Kovács, K., Perei, K., Feigl, G. Impacts of Plastics on Plant Development: Recent Advances and Future Research Directions. Plants, 2023, 12(18), 3282. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Zeng, X., Sun, F., Feng, T., Xu, Y., Li, Z., Zhang, Z. Physiological analysis and transcriptome profiling reveals the impact of microplastic on melon (Cucumis melo L.) seed germination and seedling growth. J. Plant Phys., 2023, 287, 154039. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M., Liu, Y., Wang, H., Weng, Y.; Gong, D., Bai, X. Physiological Toxicity and Antioxidant Mechanism of Photoaging Microplastics on Pisum sativum L. Seedlings. Toxics, 2023, 11, 242. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Ruiz, H., Martin-Closas, L., Pelacho, A.M. Impact of buried debris from agricultural biodegradable plastic mulches on two horticultural crop plants: Tomato and lettuce. Sci. Total Environ., 2023, 856, 159167. [CrossRef]

- Bouaicha, O., Tiziani, R., Maver, M., Lucini, L., Miras-Moreno, B., Zhang, L., Trevisan, M., Cesco, S., Borruso, L., Mimmo, T. Plant species-specific impact of polyethylene microspheres on seedling growth and the metabolome. Sci. Total Environ., 2022, 840, 156678. [CrossRef]

- Esterhuizen, M., Vikfors, S., Penttinen, O-P., Kim, Y. J., Pflugmacher, S. Lolium multiflorum germination and growth affected by virgin, naturally, and artificially aged high-density polyethylene microplastic and leachates. Front. Environ. Sci., 2022, 10, 964230. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R., Liu, W., Lian, Y., Wang, Q., Zeb, A., Tang, J. Phytotoxicity of polystyrene, polyethylene and polypropylene microplastics on tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.). J. Environ. Manag., 2022, 317, 115441. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Hou, H., Liu, Y., Yin, S., Bian, S., Liang, S., Wan, C., Yuan, S., Xiao, K., Liu, B. Microplastics affect rice (Oryza sativa L.) quality by interfering metabolite accumulation and energy expenditure pathways: a field study. J. Hazard. Mater., 2022, 422, 126834. [CrossRef]

- Gong, W., Zhang, W., Jiang, M., Li, S., Liang, G., Bu, Q., Xu, L., Zhu, Z., Lu, A. Species-dependent response of food crops to polystyrene nanoplastics and microplastics, Sci. Total Environ., 2021, 796, 148750. [CrossRef]

- Pignattelli, S., Broccoli, A., Renzi, M. Physiological responses of garden cress (L. sativum) to different types of microplastics. Sci. Total Environ., 2020, 727, 138609. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Jin, T., Wang, L., Tang, J. Polystyrene micro and nanoplastics attenuated the bioavailability and toxic effects of Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) on soybean (Glycine max) sprouts.J. Hazard. Mater., 2023, 448, 130911. [CrossRef]

- Liwarska-Bizukojc, E. Effect of innovative bio-based plastics on early growth of higher plants. Polymers, 2023, 15, 438. [CrossRef]

- Spanò, C., Muccifora, S., Castiglione, M.R., Bellani, L., Bottega, S., Giorgetti, L. Polystyrene nanoplastics affect seed germination, cell biology and physiology of rice seedlings in-short term treatments: evidence of their internalization and translocation. Plant Physiol. Biochem., 2022, 172, 158–166. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Zhao, M., Meng, F., Xiao, Y., Dai, W., Luan, Y. Effect of polystyrene microplastics on rice seed germination and antioxidant enzyme activity. Toxics, 2021, 9(8), 179. [CrossRef]

- Lian, J., Wu, J., Xiong, H., Zeb, A., Yang, T., Su, X., Su, L., Liu, W. Impact of polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs) on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Hazard. Mater., 2020, 385, 121620. [CrossRef]

- Colzi, I., Renna, L., Bianchi, E., Castellani, M. B., Coppi, A., Pignattelli, S., Loppi, S., Gonnelli, C. Impact of microplastics on growth, photosynthesis and essential elements in Cucurbita pepo L. J. Hazard. Mater., 2022, 423, 127. [CrossRef]

- Zantis. L. J., Adamczyk, S., Velmala, S. M., Adamczyk, B., Vijver, M. G., Peijnenburg, W., Bosker, T. Comparing the impact of microplastics derived from a biodegradable and a conventional plastic mulch on plant performance. Sci. Total Environ., 2024, 935, 173265. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G., Li, Y., Lin, X., Yu, Y. Effects and mechanisms of polystyrene micro- and nano-plastics on the spread of antibiotic resistance genes from soil to lettuce. Sci, Total Environ., 2024, 912, 169293. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, Y. M., Rillig, M. C. Effects of microplastic fibers and drought on plant communities. Environ, Sci. & Techn., 2020, 54(10), 6166-6173. [CrossRef]

- Jia, L. H., Liu, L., Zhang, Y., Fu, W., Liu, X., Wang, Q., Tanveer, M., Huang, L. Microplastic stress in plants: effects on plant growth and their remediations. Front. Plant Sci., 2023, 14, 1226484 . [CrossRef]

- Rong, S., Wang, S., Liu, H., Li, Y., Huang, J., Wang, W., Liu, W. Evidence for the transportation of aggregated microplastics in the symplast pathway of oilseed rape roots and their impact on plant growth. Sci. Total Environ., 2024, 912, 169419. [CrossRef]

- Cui J., Li, X., Gan, Q., Lu, Z., Du, Y., Noor, I., Wang, L., Liu, S., Jin, B. Flavonoids Mitigate Nanoplastic Stress in Ginkgo biloba. Plant Cell Environ., 2024, 48, 1790-1811. [CrossRef]

- Ren, F., Huang, J., Yang, Y. Unveiling the impact of microplastics and nanoplastics on vascular plants: A cellular metabolomic and transcriptomic review. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf, 2024, 279, 116490-116490. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Gao, M., Qiu, W., Song, Z. Uptake of microplastics by carrots in presence of as (III): combined toxic effects. J. Hazard Mater., 2021, 411, 125055. [CrossRef]

- Giorgetti, L., C. Spanò, C., Muccifora, C. S., Bottega, S., Barbieri, F., Bellani, L., Ruffini Castiglion, M. Exploring the interaction between polystyrene nanoplastics and Allium cepa during germination: internalization in root cells, induction of toxicity and oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem., 2020, 149, 170–177. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., An, S., Kim, L., Byeon, Y. M., Lee, J., Choi, M. J., An, Y. J. Translocation and chronic effects of microplastics on pea plants (Pisum sativum) in copper-contaminated soil. J. Hazard. Mater., 2020, 436, 129194. [CrossRef]

- Shorobi, F. M., Vyavahare, G. D., Seok, Y. J., Park J. H. Effect of polypropylene microplastics on seed germination and nutrient uptake of tomato and cherry tomato plants. Chemosphere, 2023, 329, 138679. [CrossRef]

- Oliveri Conti, G, Ferrante, M. Banni, M., Favara, C., Nicolosi, I., Cristaldi, A., Fiore, M., Zuccarello, P. Micro- and nano-plastics in edible fruit and vegetables. The first diet risks assessment for the general population. Environ. Res., 2020, 187, 109677. [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, K., Rajendiran, R., Pasupathi, M. S., Ahamed, S. B. N., Kalyanasundaram, R., Velu, R. K. Authentication of Microplastic Accumulation in Customary Fruits and Vegetables. Res. Squ., 2022 (preprint) . [CrossRef]

- Canha, N., Jafarova, M., Grifoni, L., Gamelas, C. A., Alves, L. C., Almeida, S. M., Loppi, S. Microplastic contamination of lettuces grown in urban vegetable gardens in Lisbon (Portugal). Sci. Rep., 2023, 13(1), 14278. [CrossRef]

- Aydın, R. B., Yozukmaz, A., Şener, İ., Temiz, F., Giannetto, D. Occurrence of Microplastics in Most Consumed Fruits and Vegetables from Turkey and Public Risk Assessment for Consumers. Life, 2023, 13(8), 1686. [CrossRef]

- Conti, G. O., Ferrante, M., Banni, M., Favara, C., Nicolosi, I., Cristaldi, A., Fiore, M., Zuccarello, P. Micro- and nano-plastics in edible fruit and vegetables. The first diet risks assessment for the general population. Environ. Res., 2020, 187, 109677. [CrossRef]

- Tympa, L.-E., Katsara, K., Moschou, P.N., Kenanakis, G, Papadakis, V.M. Do microplastics enter our food chain via root vegetables? A Raman based spectroscopic study on raphanus sativus. Materials, 2021, 14, 2329. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Song, Z., Liu, Y., Gao, M. Polystyrene particles combined with di-butyl phthalate cause significant decrease in photosynthesis and red lettuce quality. Environ. Pollut., 2021, 278, 116871. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z., Xu, X., Guo, L., Jin, R., Lu, Y. Uptake and transport of micro/nanoplastics in terrestrial plants: Detection, mechanisms, and influencing factors. Sci. Total Environ., 2024, 907, 168155. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Zhang, S., Xing, H., Yan, P., Wang, J. Soil moisture and texture mediating the micro (nano) plastics absorption and growth of lettuce in natural soil conditions. J. Hazard. Mater., 2025, 482, 136575. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Du, A., Ge, T., Li, G., Lian, X., Zhang, S., Wang, X. Accumulation modes and effects of differentially charged polystyrene nano/microplastics in water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica F.). J. Hazard. Mater., 2024, 480, 135892. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Hu, C., Wang, X., Cheng, H., Xing, J., Li, Y., Wang, L., Ge, T., Du, A., Wang, Z. Water Spinach (Ipomoea aquatica F.) Effectively Absorbs and Accumulates Microplastics at the Micron Level—A Study of the Co-Exposure to Microplastics with Varying Particle Sizes. Agriculture, 2024, 14(2), 301. [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z., Zhang, T., Luo, J., Bai, H., Ma, S., Qiang, H., Guo, X. Internalization, physiological responses and molecular mechanisms of lettuce to polystyrene microplastics of different sizes: Validation of simulated soilless culture. J. Hazard. Mater., 2024, 462, 132710. [CrossRef]

- Castan, S., Sherman, A., Peng, R., Zumstein, M. T., Wanek, W., Hüffer, T., Hofmann, T. Uptake, metabolism, and accumulation of tire wear particle-derived compounds in lettuce. Environ. Sci. & Tech., 2022, 57(1), 168-178. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Li, Q., Li, R., Zhou, J., Wang, G. The distribution and impact of polystyrene nanoplastics on cucumber plants. Environ. Sci.Pollu. Res., 2021, 28, 16042-16053. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Xiang, L., Wang, F., Wang, Z., Bian, Y., Gu, C., Xing, B. Positively charged microplastics induce strong lettuce stress responses from physiological, transcriptomic, and metabolomic perspectives. Environ. Sci. & Tech., 2022, 56(23), 16907-16918. [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, M., Liu, X., Yang, J., Xu, G. Foliar implications of polystyrene nanoplastics on leafy vegetables and its ecological consequences. J. Hazard. Mater, 2024, 480, 136346. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Wei, J. H., Wei, B. K., Chen, Z. Q., Liu, H. L., Zhang, W. Y., Zhou, D. M. Metabolic response of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) to polystyrene nanoplastics and microplastics after foliar exposure. Environ. Sci. Nano, 2024, 11(12), 4847-4861. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., White, J. C., He, E., Van Gestel, C. A., Cao, X., Zhao, L., Qiu, H. Foliar exposure of deuterium stable isotope-labeled nanoplastics to lettuce: Quantitative determination of foliar uptake, transport, and trophic transfer in a terrestrial food chain. Environ. Sci. & Tech., 2024. 58(35), 15438-15449. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Stimulation versus inhibition: The effect of microplastics on pak choi growth. Appl. Soil Ecol., 2022, 177, 104505. [CrossRef]

- Meng, J., Diao, C., Cui, Z., Li, Z., Zhao, J., Zhang, H., Chen, H. Unravelling the influence of microplastics with/without additives on radish (Raphanus sativus) and microbiota in two agricultural soils differing in pH. J. Hazard. Mater., 2024, 478, 135535. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T., Hussain, H., Sabir, A., Irfan, M., Ghafar, A., Jafir, M., Sabir, M. A., Zulfiqar, U., Binobead, M. A., Al Munqedhi, B.M. Impact of Microplastic on Roadside Vegetable Cultivation: A Case Study of Agricultural Farmland. Pol. J. Environ. Stud., 2025, 34(3):2525-2538. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Wang, J., Yan, P., Aurangzeib, M. Middle concentration of microplastics decreasing soil moisture-temperature and the germination rate and early height of lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. ramosa Hort.) in Mollisols. Sci. Total Environ., 2023, 905, 167184. [CrossRef]

- Gao, D., Liao, H., Junaid, M., Chen, X., Kong, C., Wang, Q., Wang, J. Polystyrene nanoplastics' accumulation in roots induces adverse physiological and molecular effects in water spinach Ipomoea aquatica Forsk. Sci. Total Environ., 2023, 872, 162278. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Xiang, L., Wang, F., Redmile-Gordon, M., Bian, Y., Wang, Z., Xing, B. Transcriptomic and metabolomic changes in lettuce triggered by microplastics-stress. Environ. Pollut., 2023, 320, 121081. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Yan, J., Li, Y., Liu, Y., Andom, O., Li, Z. Microplastics alter cadmium accumulation in different soil-plant systems: Revealing the crucial roles of soil bacteria and metabolism. J. Hazard. Mater., 2024, 474, 134768. [CrossRef]

- Maryam, B., Asim, M., Li, J., Qayyum, H., Liu, X. Luminous polystyrene upconverted nanoparticles to visualize the traces of nanoplastics in a vegetable plant. Environ. Sci. Nano, 2025, 12, 1273-1287. [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, S., Zantis, L. J., van Loon, S., van Gestel, C. A., Bosker, T., Hurley, R., Velmala, S. Biodegradable microplastics induce profound changes in lettuce (Lactuca sativa) defense mechanisms and to some extent deteriorate growth traits. Environ. Pollut., 2024, 363, 125307. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y., Zhang, Y., Guan, M., Fu, Y., Yang, X., Hu, M., Yang, R. The effect of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Microplastic stress on the composition and gene regulatory network of amino acid in Capsicum annuum. Environ. Exp. Bot., 2024, 228, 106029. [CrossRef]

- Bostan, N., Ilyas, N., Saeed, M., Umer, M., Debnath, A., Akhtar, N., Bukhari, N. A. An in vitro phytotoxicity assessment of UV-enhanced biodegradation of plastics for spinach cultivation. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng., 2025, 19(2), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Han, S., Wang, P., Zhang, X., Zhang, J., Hou, L., Lin, Y. Soil microorganisms play an important role in the detrimental impact of biodegradable microplastics on plants. Sci. Total Environ., 2024, 933, 172933. [CrossRef]

- He, B., Liu, Z., Wang, X., Li, M., Lin, X., Xiao, Q., Hu, J. Dosage and exposure time effects of two micro (nono) plastics on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity in two farmland soils planted with pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Sci. Total Environ., 2024, 917, 170216. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Cao, W., Wu, W., Xin, X., Jia, H. Transcription-metabolism analysis of various signal transduction pathways in Brassica chinensis L. exposed to PLA-MPs. J. Hazard. Mater, 2025, 486, 136968. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Hoagland, L., Yang, Y., Becchi, P. P., Sobolev, A. P., Scioli, G., Lucini, L. The combination of hyperspectral imaging, untargeted metabolomics and lipidomics highlights a coordinated stress-related biochemical reprogramming triggered by polyethylene nanoparticles in lettuce. Sci. Total Environ, 2025, 964, 178604. [CrossRef]

- Yar, S., Ashraf, M. A., Rasheed, R., Farooq, U., Hafeez, A., Ali, S., Sarker, P. K. Taurine decreases arsenic and microplastic toxicity in broccoli (Brassica oleracea L.) through functional and microstructural alterations. BioMetals, 2025, 38, 597–621. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Lin, X., Xu, G., Yan, Q., Yu, Y. Toxic effects and mechanisms of engineered nanoparticles and nanoplastics on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 908, 168421. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., He, J., Chen, X., Dong, X., Liu, S., Anderson, C. W., Lan, T. Interactive effects of microplastics and cadmium on soil properties, microbial communities and bok choy growth. Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 955, 176831. [CrossRef]

- Gao, M., Xu, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, S., Wang, C., Dong, Y., & Song, Z. Effect of polystyrene on di-butyl phthalate (DBP) bioavailability and DBP-induced phytotoxicity in lettuce. Env. Pollut., 2021, 268, 115870. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Zhao, S., Chen, L., Duan, C., Zhang, X., Fang, L. A review of microplastics in soil: occurrence, analytical methods, combined contamination and risks. Env. Pollut., 2022, 306, 119374. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Li, J., Song, Y., Zhang, Z., Yu, S., Xu, M., Zhao, Y. Stimulation versus inhibition: The effect of microplastics on pak choi growth. Appl. Soil Eco., 2022, 177, 104505. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, C., Jiang, M., Zhou, G. Bio-effects of bio-based and fossil-based microplastics: Case study with lettuce-soil system. Env. Pollut., 2022, 306, 119395. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Luo, X. S., Xu, J., Yao, X., Fan, J., Mao, Y., Khattak, W. A. Dry–wet cycle changes the influence of microplastics (MPs) on the antioxidant activity of lettuce and the rhizospheric bacterial community. J. Soils Sediments, 2023, 23(5), 2189-2201. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Vaccari, F., Bandini, F., Puglisi, E., Trevisan, M., Lucini, L. The short-term effect of microplastics in lettuce involves size-and dose-dependent coordinate shaping of root metabolome, exudation profile and rhizomicrobiome. Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 945, 174001. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Y., Niu, S. H., Li, H. Y., Liao, X. D. Xing, S. C. Multiomics analysis of the effects of manure-borne doxycycline combined with oversized fiber microplastics on pak choi growth and the risk of antibiotic resistance gene transmission. J. Hazard. Mater, 2024, 475, 134931. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y., Teng, Y., Wang, X., Wen, D., Gao, P., Yan, D., Yang, N. Biodegradable PBAT microplastics adversely affect pakchoi (Brassica chinensis L.) growth and the rhizosphere ecology: Focusing on rhizosphere microbial community composition, element metabolic potential, and root exudates. Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 912, 169048. [CrossRef]

- Pan, B., Pan, B., Lu, Y., Cai, K., Zhu, X., Huang, L., Mo, C. H. Polystyrene microplastics facilitate the chemical journey of phthalates through vegetable and aggravate phytotoxicity. J. Hazard. Mater, 2024, 480, 135770. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., Xu, Y., Liu, G., Li, B., Guo, T., Ouyang, D., Zhang, H. Polyethylene microplastic modulates lettuce root exudates and induces oxidative damage under prolonged hydroponic exposure. Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 916, 170253. [CrossRef]

- López, M. D., Toro, M. T., Riveros, G., Illanes, M., Noriega, F., Schoebitz, M., Moreno, D. A. Brassica sprouts exposed to microplastics: Effects on phytochemical constituents. Sci. Total Environ, 2022, 823, 153796. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, B., Zhou, J., Li, D., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, G. Effects of naturally aged microplastics on arsenic and cadmium accumulation in lettuce: Insights into rhizosphere microecology. J. Hazard. Mater, 2025, 486, 136988. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Liu, W., Wang, X., Zeb, A., Wang, Q., Mo, F., Lian, Y. Assessing stress responses in potherb mustard (Brassica juncea var. multiceps) exposed to a synergy of microplastics and cadmium: Insights from physiology, oxidative damage, and metabolomics. Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 907, 167920. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Huang, W., Wang, Y., Wen, Q., Zhou, J., Wu, S., Qiu, R. Effects of naturally aged microplastics on the distribution and bioavailability of arsenic in soil aggregates and its accumulation in lettuce. Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 914, 169964. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Qian, X., Chen, J., Yuan, X., Zhu, N., Chen, Y., Feng, Z. (2023). Co-exposure of polystyrene microplastics influence cadmium trophic transfer along the “lettuce-snail” food chain: Focus on leaf age and the chemical fractionations of Cd in lettuce. Sci. Total Environ, 892, 164799. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Peng, C., Shao, X., Gong, K., Zhao, X., Xie, W., Tan, J. Unveiling the impacts of biodegradable microplastics on cadmium toxicity, translocation, transformation, and metabolome in lettuce. Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 957, 177669. [CrossRef]

- Roy R, Hossain A, Sultana S, Deb B, Ahmod MM, Sarker T. Microplastics increase cadmium absorption and impair nutrient uptake and growth in red amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor L.) in the presence of cadmium and biochar. BMC Plant Biol.; 2024, 24(1):608. [CrossRef]

- Men, C., Xie, Z., Li, K., Xing, X., Li, Z., Zuo, J. Single and combined effect of polyethylene microplastics (virgin and naturally aged) and cadmium on pakchoi (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis) under different growth stages. Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 951, 175602. [CrossRef]

- Bethanis, J., Golia, E. E. Revealing the Combined Effects of Microplastics, Zn, and Cd on Soil Properties and Metal Accumulation by Leafy Vegetables: A Preliminary Investigation by a Laboratory Experiment. Soil Syst., 2023, 7(3), 65. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G., Lin, X., Yu, Y. Different effects and mechanisms of polystyrene micro-and nano-plastics on the uptake of heavy metals (Cu, Zn, Pb and Cd) by lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Environ. Pollut., 2023, 316, 120656. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Wang, P., Zhao, S., Shi, H., Zhu, Y., Teng, Y., Liu, S. Combined effects of microplastics and cadmium on the soil-plant system: phytotoxicity, Cd accumulation and microbial activity. Environ. Pollut., 2023, 333, 121960. [CrossRef]

- Ju, H., Yang, X., Tang, D., Osman, R., & Geissen, V. Pesticide bioaccumulation in radish produced from soil contaminated with microplastics. Sci. Total Environ, 2024, 910, 168395. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Chen, M., Li, M., Liu, H., Tang, H., Yang, Y. Do differentially charged nanoplastics affect imidacloprid uptake, translocation, and metabolism in Chinese flowering cabbage? Sci. Total Environ., 2023, 871, 161918. [CrossRef]

- Cui, M., Yu, S., Yu, Y., Chen, X., Li, J. Responses of cherry radish to different types of microplastics in the presence of oxytetracycline. Plant Physiol Biochem, 2022, 191, 1-9. [CrossRef]

| Base | Search Equation | Number of articles |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (microplastic OR "micro-plastics" OR nanoplastic*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (vegetables) AND PUBYEAR > 2020 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 | 260 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (microplastic* OR "micro-plastics" OR nanoplastic*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (vegetables) AND PUBYEAR > 2020 AND PUBYEAR <2026 AND (EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "MEDI") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "SOCI") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "ENER") OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "CENG") | 189 |

| Vegetables | Reference |

|---|---|

| Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis L.) | Zytowski et al [33] |

| Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica Plenck.) | Yar et al [112] López et al [125] |

| Cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis L.) | Ahmad et al [99] |

| Carrot (Daucus carota L.) | Dong et al [75] |

| Chinese flowering cabbage (Brassica rapa var. parachinensis) |

Ilyas et al [94] Pan et al [123] Tang et al [137] |

| Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) | Aydin et al [82] Huang et al [47] Li et al, 2021 [92] |

| Field mustard spinach (Brassica rapa var. perviridis L.) |

Maryam et al [104] |

| Leaf mustard (Brassica juncea) |

Wang et al [135] |

| Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L) |

Liu et al [126] Zhang et al [111] Wang et al [87] Xu et al [69] Adamczyk et al [105] Zhang et al [120] Jiang et al [96] Cai et al [124] Liu et al [128] Xu et al [130] Li et al [114] Hua et al [90] Li et al [113] Zhang et al [100] Canha et al [81] Wang et al [129] Bethanis and Golia [133] Zhang et al [119] Wang et al. [102] Xu et al [134] Castan et al [91] Wang et al [93] Zhang et al [118] Dong et al [85] Gong et al [60] Lian et al [44] Gao et al [115] |

| Melon (Cucumis melo L) | He et al [109] Li et al [53] |

| Onion (Allium cepa L.) | Ilyas et al [94] Aydin et al [82] |

| Pak choi (Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis) |

Li et al [110] Zytowski et al [33] Li et al [114] Ilyas et al [94] Men et al [132] Chen et al [37] Li et al [103] Liu et al [108] Han et al [122] Zhao [97] Yu et al [117] |

| Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) |

Cui et al [106] |

| Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) |

Ahmad et al [99] Aydin et al [82] |

| Potherb mustrad (Brassica juncea var. multiceps) |

Wang et al [127] |

| Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) |

Zytowski et al [33] Meng et al [98] Ju et al [136] Cui et al [138] López et al [125] Gong et al [60] Tympa et al [84] |

| Red amarant (Amaranthus tricolor L.) | Roy et al [131] |

| Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) | Bostan et al [107] Ahmad et al [99] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) | Zytowski et al [33] Aydin et al [82] |

| Watter spinach (Ipomea aquatica F.) | Zhao et al [88] Zhao et al [89] Gao et al [101] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).