1. Introduction

As the demographic diversity of higher education students expands, so too do their varying attitudes, motivations, and abilities. Upon transitioning to university, secondary school students often encounter large lectures devoid of fixed classmates, seating arrangements, and stringent mobile phone policies. Educators frequently struggle to foster student engagement both within and outside the classroom environment. Some students may experience discomfort in seeking assistance from instructors regarding academic inquiries. Such anxiety can adversely affect both interpersonal relationships and scholarly performance.

Ideally, educators would provide individualized attention to each student; however, this is impractical due to limited teaching time and potential educator fatigue following prolonged consultations. Furthermore, many students exhibit shyness in approaching instructors for clarification. They may also hesitate to engage peers for fear of jeopardizing their social standing (Carayannopoulos, 2018).

The chatbot possesses the capability to engage in conversations that closely resemble human interactions, devoid of the feelings of boredom or fatigue that characterize human communicative exchanges. Given that the primary function of the chatbot is to facilitate user dialogue, coupled with the necessity for proficiency in computer programming to construct such a tool, the majority of scholarly research pertaining to chatbots in educational contexts is predominantly confined to disciplines related to computer science and foreign language acquisition. Deveci, Dilek, and Kolburan (2021) conducted an investigation into a chatbot specifically designed for learners enrolled in the science curriculum covering “Matter and the changing state of matter.” Additionally, another chatbot was developed for students enrolled in courses on the fundamentals of computer science and computer networks (Clarizia, Colace, Lombardi, Pascale, & Santaniello, 2018, October). Yin et al. (2021) discovered that the chatbot proved to be effective in instructing students on the topic of number system conversion within a computer science course, employing a quasi-experimental methodology. Haristiani (2019, November) examined the potential for utilizing a chatbot as a medium for language acquisition. Vázquez-Cano, Mengual-Andrés, & López-Meneses (2021) explored both the efficacy and the perceptions of students regarding the use of a chatbot aimed at enhancing punctuation learning in the Spanish language. Their research employed a quasi-experimental design, incorporating both pretest and posttest assessments within a control group and an experimental group. The findings indicated that students in the experimental group exhibited significantly greater advancements in their post-test scores compared to those in the control group. Furthermore, participants in the experimental group provided favorable evaluations of the chatbot in relation to its support features and user-friendliness.

The existing body of research on chatbots as educational tools has predominantly concentrated on their capability for human-like conversational interactions. Although contemporary chatbots possess a plethora of functionalities that extend beyond mere textual exchanges, there remains a conspicuous dearth of scholarly inquiry into their potential as a more comprehensive student support mechanism (Bii, Too, & Mukwa, 2018; Carayannopoulos, 2018). Research surrounding chatbots as educational tools has primarily centered on their conversational capabilities. Despite the broader functionalities of contemporary chatbots, limited studies address their application as a student support mechanism in their non-course specific activities (Bii et al., 2018; Carayannopoulos, 2018). This study aims to investigate the utilization of chatbots by students in the context of completing a non-academic subject.

2. Work-Integrated Education (WIE) and the WIEBot

At this university, work-integrated education (WIE) is a graduation requirement for all students. The students must accumulate 300 hours of work experience to fulfil the WIE requirements. Students must submit forms including the proposal, log sheet, and reflective learning statement (RLS). As the WIE has no lessons and no assigned teacher, students are often not sure what they should do. In the past, the students could only approach their WIE advisor when they had questions. However, the WIE advisor may not be always available. The authors developed a chatbot called WIEBot, using NodeJS and MongoDB. Students can access the chatbot using the Telegram social media platform. By putting this WIEBot use, students can obtain any information related to WIE anytime in real-time as they have their own schedule and timetable.

The WIEBot was conceived as a prototype within the framework of a student-led initiative in the year 2020. Subsequently, it underwent enhancements to facilitate support for WIE education for a cohort of 105 students enrolled in an undergraduate program in Applied Sciences. The users of the WIEBot are afforded access through the social media platform Telegram. The selection of Telegram was predicated on its popularity among students, in addition to its efficacy as a platform for the development of chatbots. The underlying engine of the chatbot was constructed utilizing the NodeJS programming language, alongside the cloud-based database MongoDB Atlas.

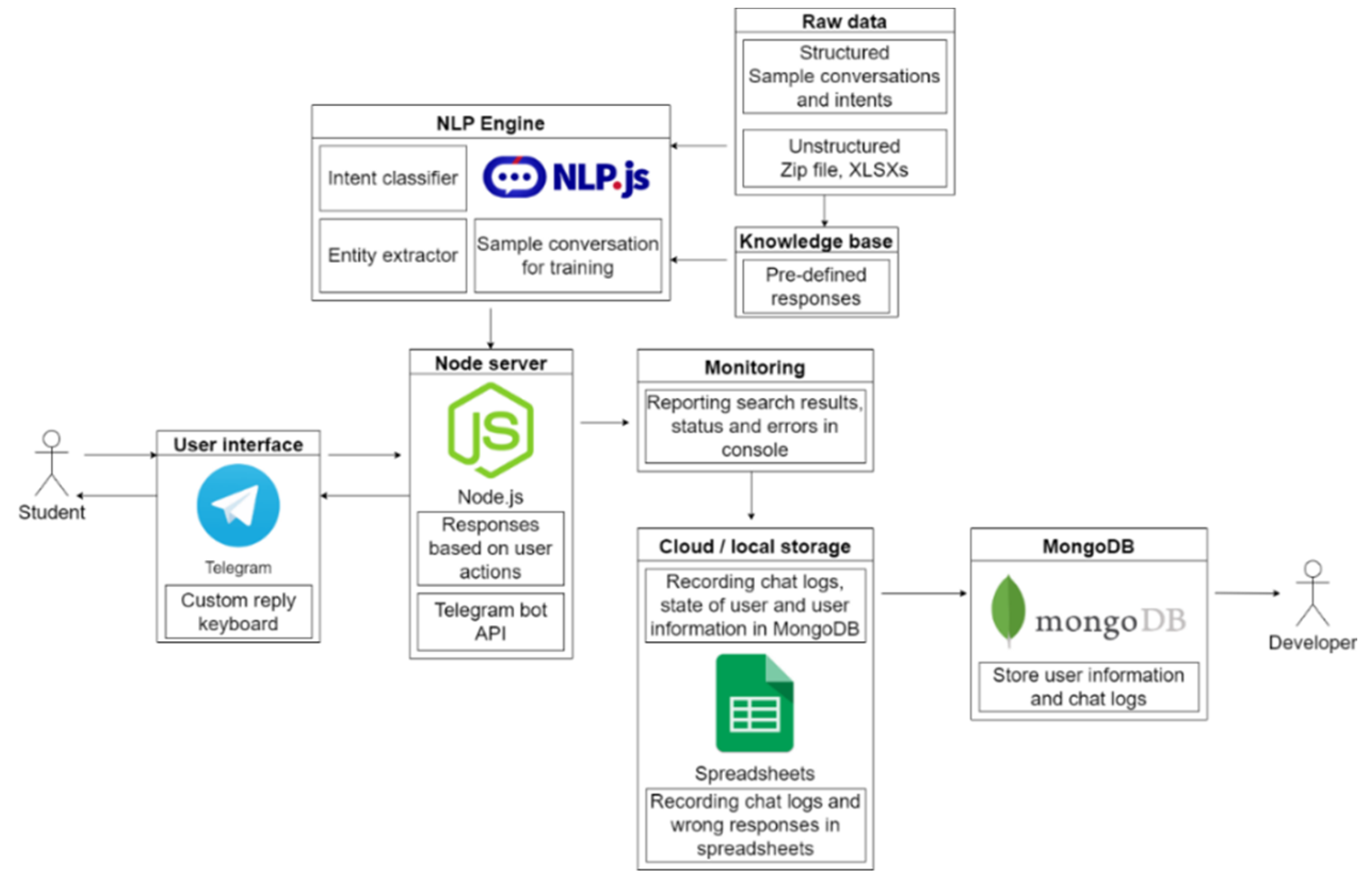

The technical architecture is shown in

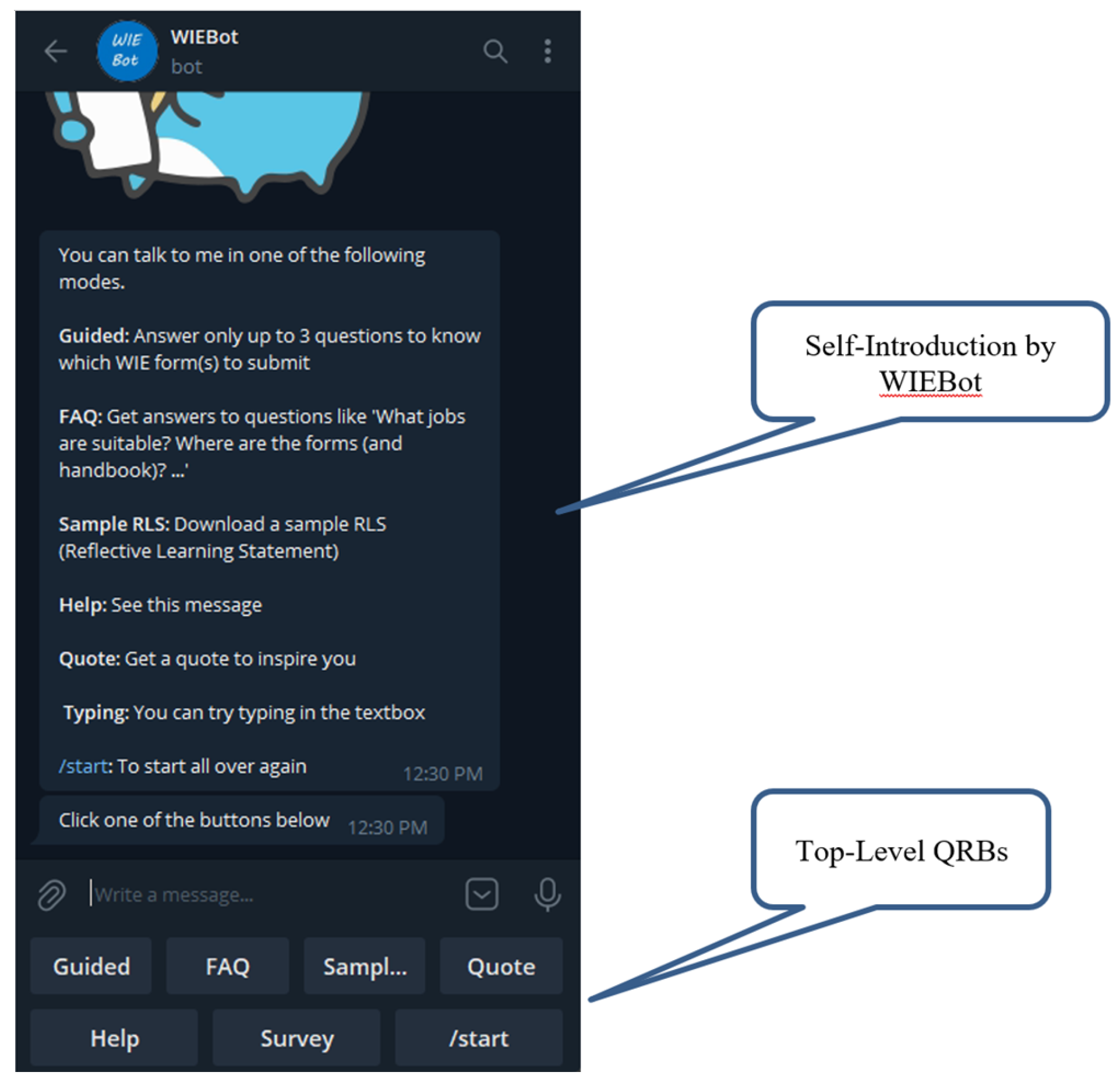

Figure 1. The startup screen of the WIEBot is shown in

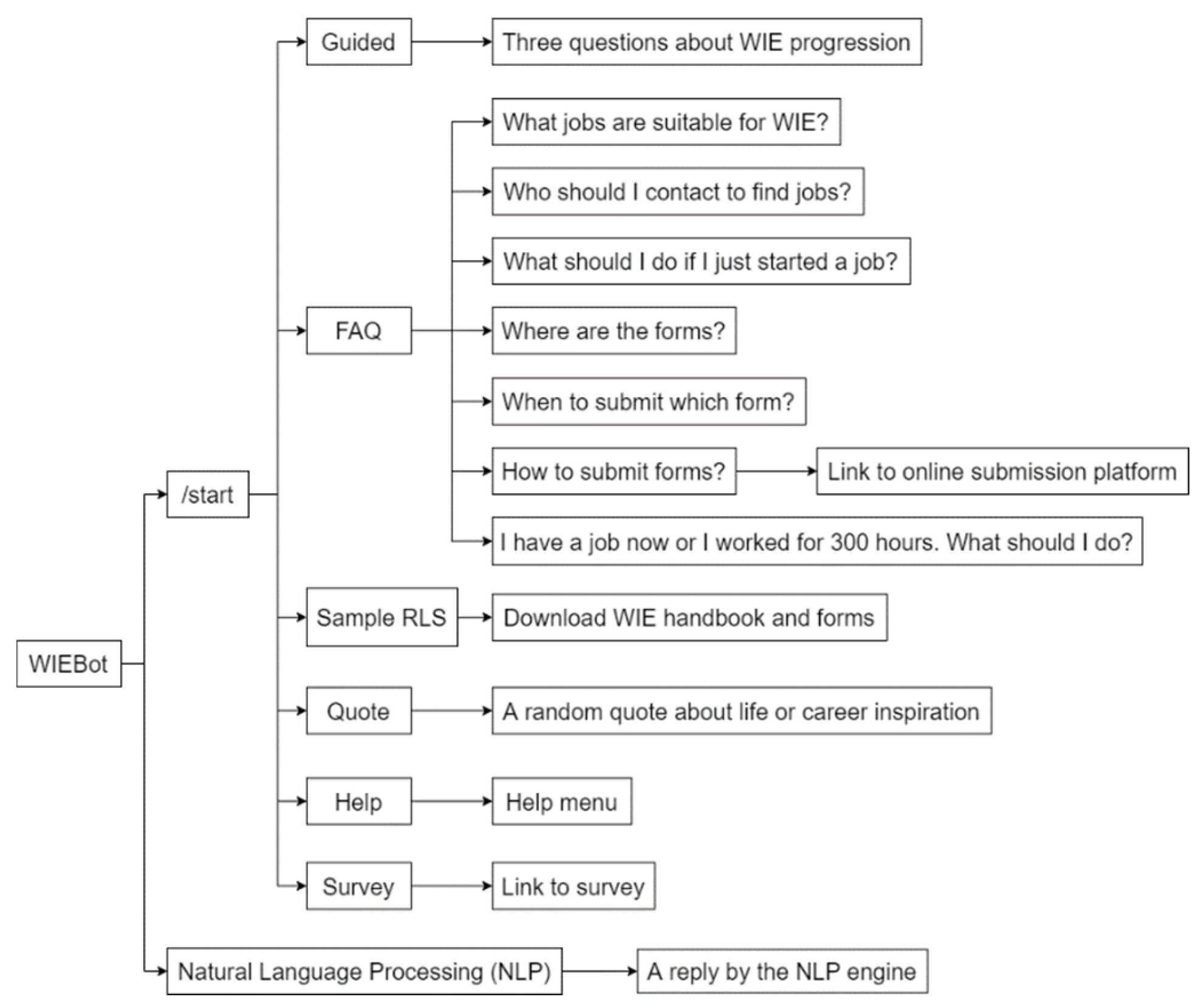

Figure 3. As shown in the Major functional blocks diagram in

Figure 2, users can start interaction by clicking a quick response button (QRB) or typing free text like the lines below.

“I need a job”

“Hi, where are the WIE forms?”

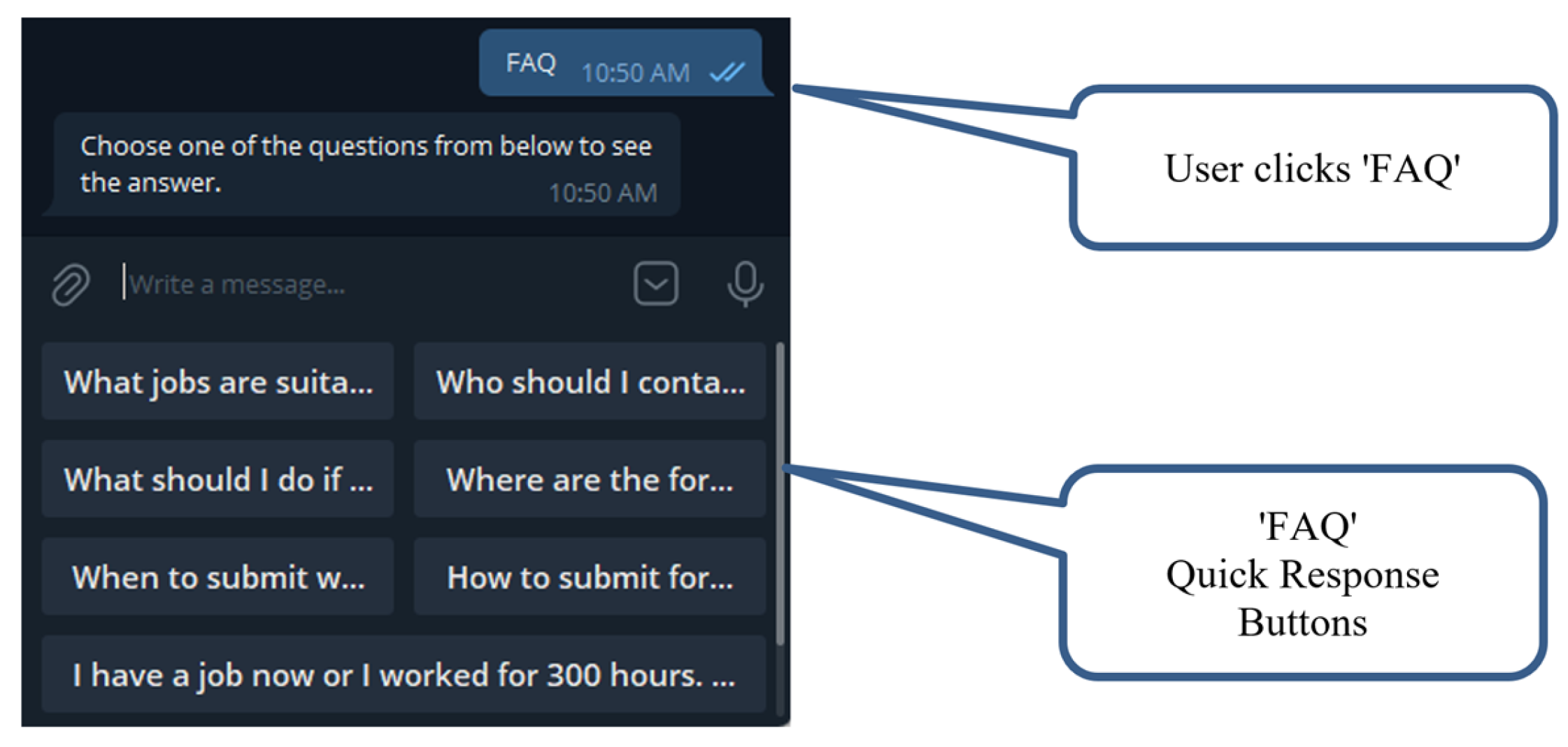

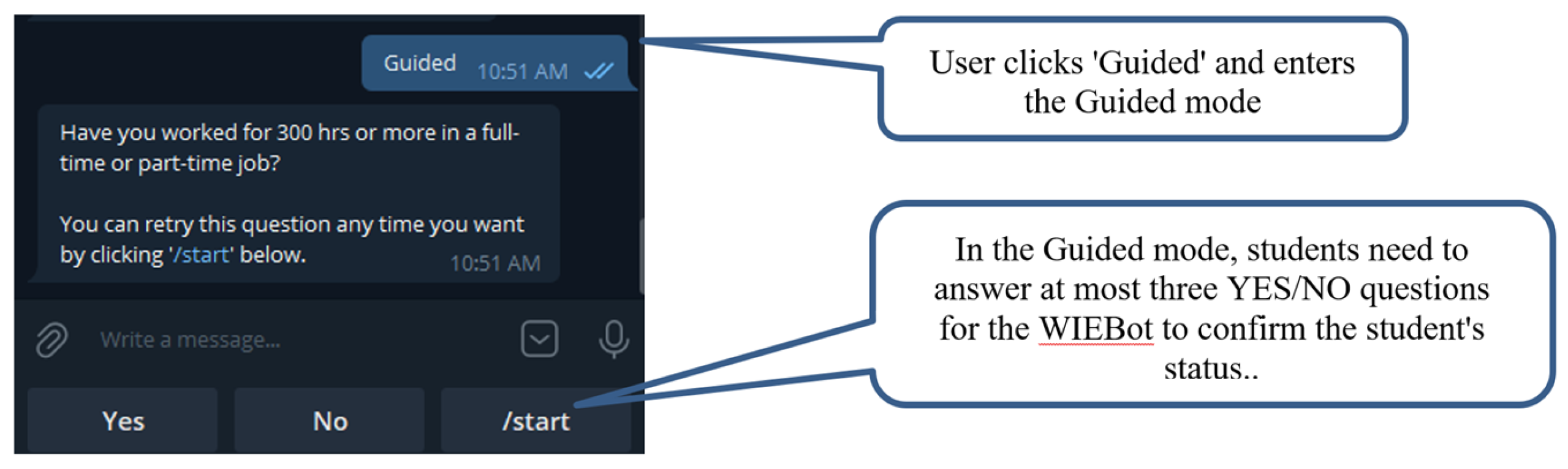

If the user clicks “FAQ” from the start-up screen, the WIEBot will show the frequently asked questions as buttons for the user to click. If the user clicks “Guided” from the start-up screen, the WIEBot will begin to ask the user a series of questions to understand the current status of the student. The questions were carefully designed so that no more than three questions needed to be asked. The starting screen of the “Guided” mode is shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 1.

WIEBot Technical Architecture.

Figure 1.

WIEBot Technical Architecture.

Figure 2.

Major functional blocks of the WIEBot.

Figure 2.

Major functional blocks of the WIEBot.

Figure 3.

WIEBot self-introduction when it is started for the first time.

Figure 3.

WIEBot self-introduction when it is started for the first time.

Figure 4.

When the user selects “FAQ”, WIEBot shows “quick responses” as buttons.

Figure 4.

When the user selects “FAQ”, WIEBot shows “quick responses” as buttons.

Figure 5.

WIEBot offers the “Guided” mode which can cover all possible scenarios by asking three questions.

Figure 5.

WIEBot offers the “Guided” mode which can cover all possible scenarios by asking three questions.

3. Research Question

To the best of our knowledge, there are no chatbots developed for student career support using the tools of NodeJS, Telegram and MongoDB. Our research would help the education community to gain more knowledge on the feasibility of this combination. The research question is stated below:

Research Question: Is feasible to build a chatbot using a social network as the front end and cloud storage as the backend?

4. Methodology

The data for this research was collected using multiple channels - pilot tests and data logging. To test the feasibility of building a chatbot using the selected tools, the WIEBot was built in 2020 as a student project. It was pilot tested in early 2021 by some students. The answers provided by the WIEBot were correct. The students suggested some improvements to the user interface. Then the WIEBot was enhanced in 2021 to improve the user interface and usage logging. From 16 November 2021 to 19 November 2021, the WIEBot was introduced to students in six tutorial classes of a compulsory subject. In each of the introduction sessions, the WIEBot was introduced and demonstrated. Then the students were invited to try the WIEBot and complete an online survey during the lesson.

5. Results & Discussions

As our objective is to find out if it is feasible to build a chatbot using a social network as the frontend and cloud storage as the backend, we try to answer this question by examining the number of requests handled by the WIEBot and the type of requests made by the students. The WIEBot was running on a desktop PC with NodeJS installed. All requests to, and responses from, the WIEBot were recorded in the cloud database called MongoDB Atlas. Compared with traditional SQL databases, MongoDB Atlas provides NoSQL database services which means the developer has more flexibility in changing the way information is stored in the database. Students can access the WIEBot through the Telegram social network. This whole web application ran 24 hours a day, 7 days a week throughout the study period. No students reported technical problems during this period. The QRBs and natural language processing (NLP) can be updated by modifying the relevant JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) files. Typically, updates were implemented successfully within half a day each time.

The WIEBot ran on a desktop PC for one year and six months starting from May 2021 without students reporting any outages and errors. There were three cases in which the system halted when the developer entered special data to test the NLP. No students raised reported problems during the six introduction sessions. A summary of the WIEBot usage is shown in

Table 1. There were 68 users, and there were 1140 requests to, and replies from, the WIEBot. Most of the responses were recognized as QRBs or text that can be interpreted by the NLP engine. Only 53 free-text requests were not recognized.

Each time the user interacts with the chatbot, it is recorded as a request. The number and the content of the requests are in a cloud database. After excluding the entries made by the teacher and developer, there are 1107 entries made by the students. We found that the requests come from 68 unique users. Assuming all these users were from the population of the 105 students who were introduced to this WIEBot, the sample size is 64.7% of the population. The following sections examine the usage patterns of the students based on this sample of 68 users.

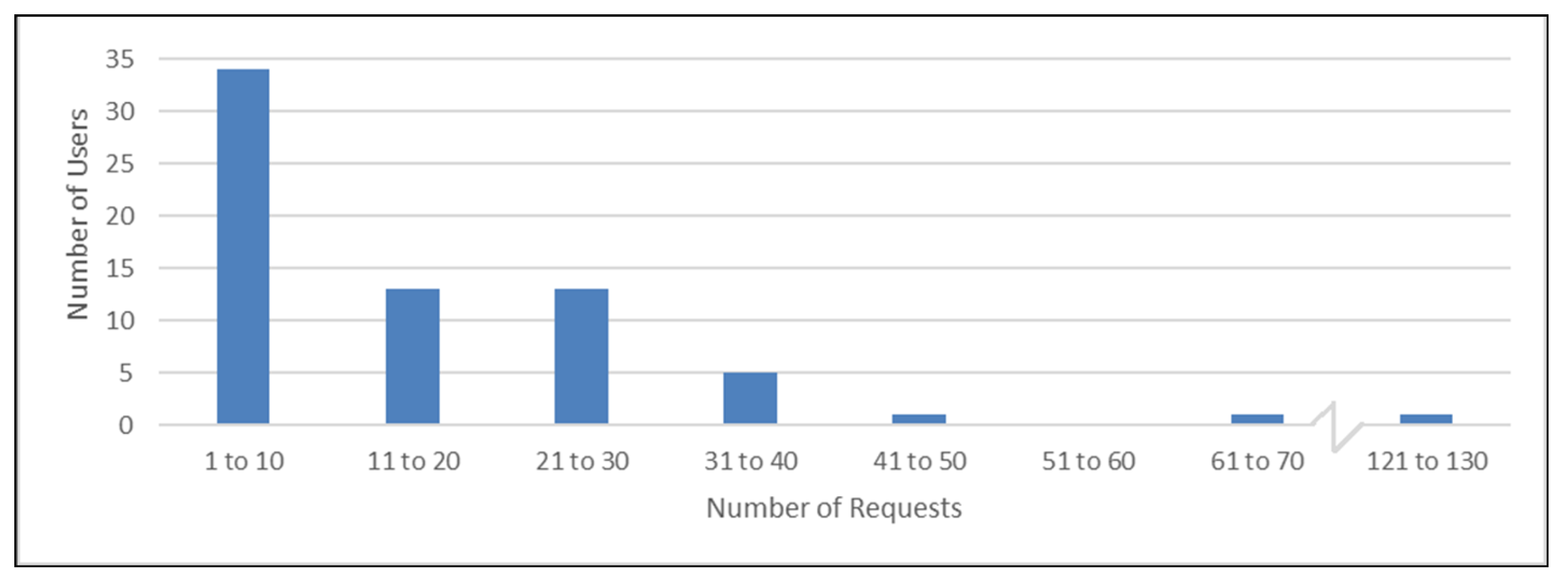

5.1. Average Number of Requests Per User

Figure 6 shows the actual usage fits this prediction. About 88% issued 30 requests or less. About 69% of the users issued fewer than 20 requests. Half of the users made 10 requests or less. This is an indication that these users found what they were looking for according to the designed usage pattern. Only 12% of the users issued more than 30 requests to WIEBot. If the information was displayed on a website, the user can move back to the previous page and the browser will display the data from the previous page from the computer’s cache. However, the WIEBot is deployed in an instant messaging app, the users may want results and answers quickly rather than searching for the answers in the chat history. The quickest way to do so is to issue a new request. This may be the reason users issuing similar requests multiple times. There is one user that has made 125 requests, of which 47 are free text requests. Based on this usage data, we assume this particular student wanted to test the Natural Language Processing (NLP) capability of the chatbot.

The WIEBot is designed to provide all the information normally within 20 requests, which consists of number of requests that a typical student must make – from the proposal, to the log sheet, and to the RLS. The first-time user will need to use “Help” a few times, read all the FAQs, try the “Guided” mode, which asks only up to 3 questions, and try several quotes for fun. This is a total of 20 requests. The second-time user will need to use “Help” fewer times, read some of the FAQs, try the “Guided” mode, and try fewer quotes for fun. This is a total of 13 requests. The third-time user probably would not try the free text input anymore but proceed straight to getting a sample of the RLS.

Table 2.

Number requests made by a typical student.

Table 2.

Number requests made by a typical student.

| |

First-time use |

Second-time use |

Third-time use |

| Request |

# of requests |

# of requests |

# of requests |

| Greeting (free text) |

3 |

1 |

0 |

| /start |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Guided |

3 |

2 |

- |

| FAQ |

7 |

5 |

- |

| Sample RLS |

- |

1 |

1 |

| Quote |

3 |

1 |

1 |

| Help |

3 |

2 |

- |

| Expected Total |

20 |

13 |

3 |

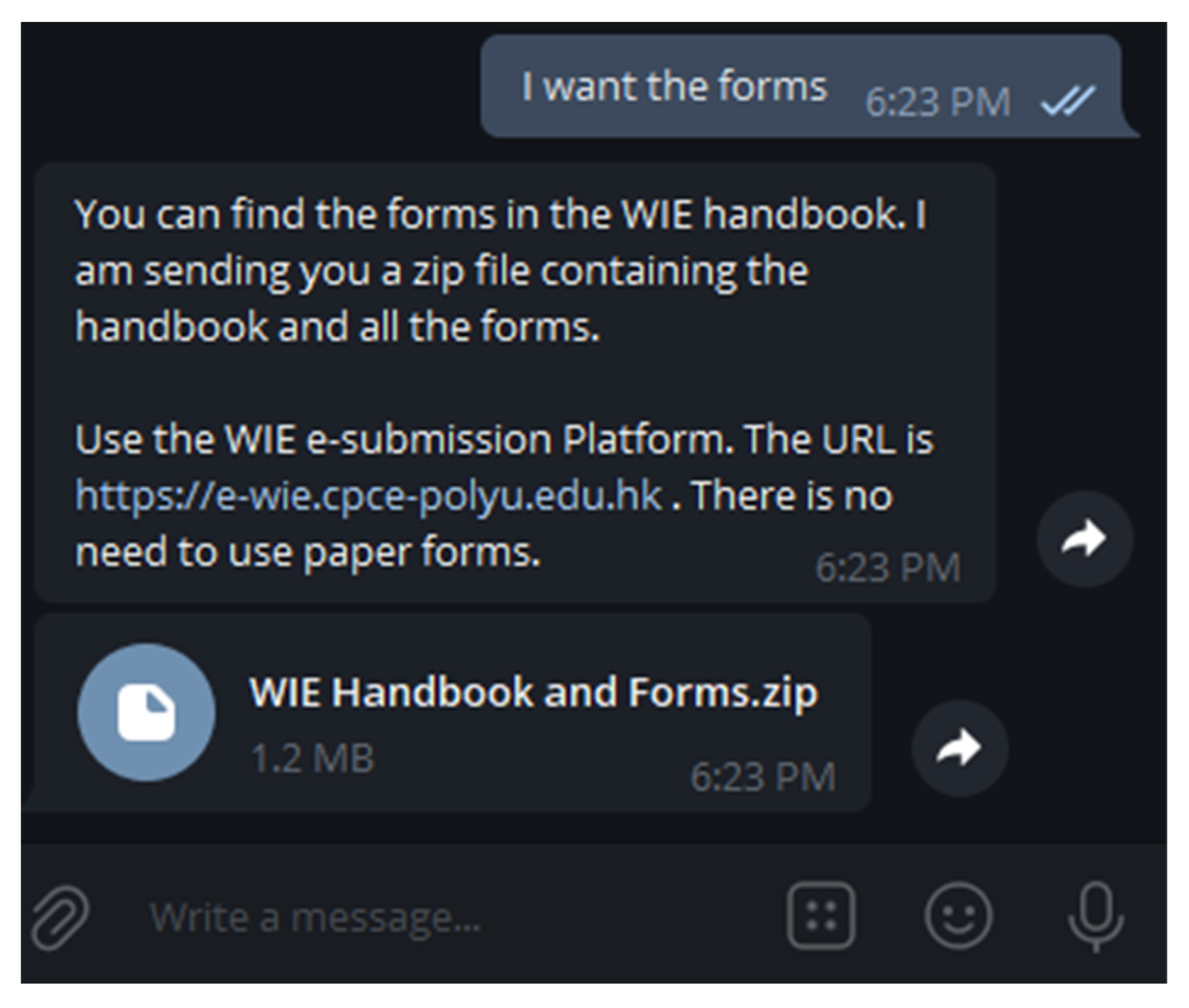

5.2. Natural Language Processing

Other than selecting the choices provided by the chatbot, users can also type freely and talk to the chatbot as the chatbot is equipped with NLP capability. It is observed that most of the students greeted the chatbot by typing “Hi”, “hi” or “hello”. The chatbot will respond will some polite responses such as “Greetings! If you need any help, please type /start”. If the student enters “Are you hungry?”, the chatbot will respond with “Hungry for Knowledge”. Some users typed gibberish too. One user tried to type in Chinese but the chatbot is designed to answer in English only. A sample dialogue is shown below.

Figure 7.

Example of NLP inside the WIEBot: The student enters “I want the forms” instead of clicking a button.

Figure 7.

Example of NLP inside the WIEBot: The student enters “I want the forms” instead of clicking a button.

There are three main purposes of implementing NLP into WIEBot. Sometimes, users may want to find information that is not available in the chatbot. NLP allows users to type what they want to know and us to collect the unrecognized requests for improving the chatbot, mainly its knowledge base. By implementing NLP, we can also observe the user’s intentions without being limited to static requests only. The free text may provide insights to us that do not exist with static requests. Moreover, NLP can provide users with more human-like interactions. The NLP engine can understand user intentions within the free text and respond accordingly thus elevating the enjoyment aspect of the WIEBot.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Our objective is to find out if it is feasible to build a chatbot using a social network as the front end and cloud storage as the backend. We proved that it is feasible to build a chatbot using a social network platform as the frontend and cloud storage as the backend. WIEBot worked as expected for one year and no students reported application outages. Many students issued free-text requests to test the NLP functions of the WIEBot.

Despite finding the answer to our research questions, certain limitations should be overcome to improve similar research in future. The chatbot is open to all users on Telegram. This means our data may include the activities of users who are not in need of WIE. In future, the chatbot should be enhanced so that the user needs to be authenticated as students who need WIE. This can be achieved by asking a simple question such as “What is the English abbreviation of the campus you are studying in?”. The chatbot should also send a daily summary of usage to the school so that any changes in usage can be dealt with swiftly. The chatbot is written in NodeJS. With the benefit of hindsight, it is better to write it in Python to take advantage of the libraries of data analytics and NLP capabilities brought by it.

From the experience of this exploratory study, we suggest some future development and research directions. To increase the perceived usefulness of the WIEBot, we suggest adding quizzes to help the students know how much they understand the learning outcomes and procedures of the WIE. The WIEBot was given to students in the “Information Systems & Web Technologies” top-up degree programme. They are likely more tech-savvy and our findings may not reflect the perceptions of users of non-IT programmes. The architecture of the WIEBot should be improved. For example, the knowledge base of NLP is stored in JSON files. Although it can be modified without changing the source code, it is not flexible to improve NLP. We suggest that the WIEBot can be revamped to be written in Python, and the NLP knowledge base to be stored in a database in the cloud. Using Python also allows the research team to use machine learning to better analyze usage patterns.

For further development work, we suggest to choose a programming language which is easily scalable. As the chatbot will be updated, maintained and enhanced continuously, we suggest keeping it modular for easy maintainability. Enjoyment is the main factor of users using a certain chatbot. Therefore, the design elements of the chatbot should involve enjoyment as one of the design principles. Using social media and cloud-based approach would be good as they will make the chatbot more accessible to the users and scalable to the developers. The application and interface provided by social media services are intuitive enough for students to use the chatbot without learning something new and specific. Also, there is no need to install or download any extra application in order to use the chatbot. The findings from this study can help solving some technical challenges found in previous studies such as those in Yang (2019, November). Finally, we suggest doing a quantitative study of students’ perception of using chatbots for learning support using a proven model such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) put forward by Davis (1989).

List of Abbreviations

FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions

JSON – JavaScript Object Notation

NLP – Natural Language Processing

QRB – Quick Response Button

RLS – Reflective Learning Statement

WIE – Work-Integrated Education

References

- Alenazy, W. M., Al-Rahmi, W. M., & Khan, M. S. (2019). Validation of TAM model on social media use for collaborative learning to enhance collaborative authoring. IEEE Access, 7, 71550-71562. [CrossRef]

- Bii, P. K., Too, J. K., & Mukwa, C. W. (2018). Teacher Attitude towards Use of Chatbots in Routine Teaching. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(7), 1586-1597. [CrossRef]

- Carayannopoulos, S. (2018). Using chatbots to aid transition. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology.

- Clarizia, F., Colace, F., Lombardi, M., Pascale, F., & Santaniello, D. (2018, October). Chatbot: An education support system for student. In International Symposium on Cyberspace Safety and Security (pp. 291-302). Springer, Cham.

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS quarterly, 319-340.

- Deveci Topal, A., Dilek Eren, C., & Kolburan Geçer, A. (2021). Chatbot application in a 5th grade science course. Education and Information Technologies, 26(5), 6241–6265. [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, S., Rizzi, S., Bassi, G., Carbone, S., Maimone, R., Marchesoni, M., & Forti, S. (2021). Engagement and effectiveness of a healthy-coping intervention via chatbot for university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: mixed methods proof-of-concept study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(5), e27965. [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications.

- Haristiani, N. (2019, November). Artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot as language learning medium: An inquiry. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1387, No. 1, p. 012020). IOP Publishing.

- Heller, B., Proctor, M., Mah, D., Jewell, L., & Cheung, B. (2005, June). Freudbot: An investigation of chatbot technology in distance education. In EdMedia+ innovate learning (pp. 3913-3918). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B., Kiran, S., Grima, S., & Rupeika-Apoga, R. (2021). Digital Banking in Northern India: The Risks on Customer Satisfaction. Risks, 9(11), 209. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

- Mailizar, M., Almanthari, A., & Maulina, S. (2021). Examining teachers’ behavioral intention to use E-learning in teaching of mathematics: an extended TAM model. Contemporary educational technology, 13(2), ep298. [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E., Wraith, S., & Duncan, T. E. (1991). Self-Efficacy, Perceptions of Success, and Intrinsic Motivation for Exercise 1. Journal of applied social psychology, 21(2), 139-155.

- Santoso, H. A., Winarsih, N. A. S., Mulyanto, E., Sukmana, S. E., Rustad, S., Rohman, M. S.,... & Firdausillah, F. (2018, September). Dinus Intelligent Assistance (DINA) chatbot for university admission services. In 2018 International Seminar on Application for Technology of Information and Communication (pp. 417-423). IEEE.

- Vázquez-Cano, E., Mengual-Andrés, S., & López-Meneses, E. (2021). Chatbot to improve learning punctuation in Spanish and to enhance open and flexible learning environments. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J., Goh, T. T., Yang, B., & Xiaobin, Y. (2021). Conversation technology with micro-learning: The impact of chatbot-based learning on students’ learning motivation and performance. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 59(1), 154-177. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., & Evans, C. (2019, November). Opportunities and challenges in using AI chatbots in higher education. In Proceedings of the 2019 3rd International Conference on Education and E-Learning (pp. 79-83).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).