1. Introduction

Educational institutions rely heavily on clear and efficient communication between students, faculty, and administrators to ensure a smooth learning experience. Timely access to information and resources is essential for academic success. Traditionally, communication has depended on in-person interactions, emails, and phone calls, which can be time-consuming and resource-intensive [

1]. The advent of chatbot systems offers a promising solution to streamline administrative tasks and enhance user experiences by providing prompt and accurate responses to a wide range of inquiries [

2,

3]. These intelligent conversational agents can reduce the administrative burden and improve accessibility for students, faculty, and staff by providing readily available information 24/7 [

4].

Despite their potential, current chatbot technologies face significant limitations. Existing approaches, such as rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative-based models, struggle to meet the diverse administrative needs of educational institutions effectively [

5]. For instance, generative models like ChatGPT can handle open-ended questions but may sometimes produce inaccurate or uncertain responses [

6]. This issue is particularly critical in educational settings, where the accuracy and reliability of information are paramount.

To address these limitations, we propose a novel hybrid chatbot model specifically designed for reliable educational administration. This model integrates the strengths of three distinct approaches—rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative-based chatbots—using a smart classifier system for intelligent query routing. By combining these methods, our hybrid model aims to provide superior performance and a dependable source of information within educational environments. Our research evaluates the effectiveness of individual chatbot models in handling educational inquiries, assessing their strengths and weaknesses, user satisfaction, and overall usefulness. Based on these evaluations, we have developed a hybrid model with an intelligent classifier to route queries to the most suitable approach. Our objective is to demonstrate the superiority of this hybrid model in terms of accuracy and reliability compared to individual models. This work contributes to the development of adaptable chatbot systems capable of addressing a broader range of administrative inquiries, which is particularly beneficial in resource-constrained educational environments. It also aims to inform future research on hybrid chatbots for educational settings.

The structure of the remaining sections of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides a review of relevant related works;

Section 3 discusses the methodology employed;

Section 4 outlines the results and discussion of the research; and

Section 5 concludes the research.

2. Literature Review

The amount of research exploring the use of chatbots in the educational field is increasing [

1], and the educational landscape is witnessing a surge in interest in chatbots as valuable tools for enhancing student learning experiences and streamlining administrative tasks. This growing adoption is driven by the potential of chatbots to provide 24/7 accessibility to information and resources [

7], fostering increased student engagement [

8], and reducing the workload on administrative staff [

9]. Studies have shown that chatbots can effectively address various needs within educational settings, which can be broadly categorized into information provision and administrative support. Regarding information provision, chatbots can address FAQs and provide users with general information regarding various aspects of educational institutions, including activities [

16,

17,

18,

19], admissions [

3,

9,

20,

21], academics [

8,

22,

23,

24], libraries [

25,

26], and other topics like tuition fees and campus life [

12,

27] . The second type of chatbot is designed to assist with administrative tasks, aiming to improve efficiency and user experience through automation. This automation benefits students, educators, and administrative staff by saving time [

28,

29], reducing workload and labor costs [

3,

23,

30,

31,

32], offering 24/7 availability [

4,

7,

15], increasing user experience [

33,

34], engagement [

4,

8,

35], and even automating the admission process [

29].

Chatbot Architectures: Based on their underlying architecture or approach, chatbot models can be classified as rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative chatbots. Rule-based chatbots follow a predefined set of rules and are designed to respond to specific keywords or phrases. Retrieval-based chatbots use a combination of predefined responses and machine learning algorithms to select the best response to a user's input. They work by matching the user's input to a database of pre-existing responses. Generative chatbots, on the other hand, use deep learning techniques like neural networks to generate responses from scratch. When it comes to chatbot development for educational institutions, the literature reflects a variety of approaches. For rule-based chatbots, some studies utilized development tools like Artificial Intelligence Markup Language (AIML) [

8,

30,

37]. Generative-based chatbots were created using techniques such as Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) [

38,

39] and Unsupervised Learning [

33]. Retrieval-based chatbots found application in educational settings through platforms like DialogFlow, a natural language understanding platform [

17,

31,

32,

41,

42,

43], as well as the RASA framework [

44,

45,

46], and Chatterbot platform [

11,

47].

Comparative Analysis: While individual studies have explored different chatbot approaches, there remains a gap in the literature concerning the development of a comprehensive and adaptable chatbot model capable of effectively handling various administrative tasks. While individual chatbot approaches have shown promise, there remains a limited understanding of their relative strengths and weaknesses in educational settings. Comparative analyses can address this gap by directly evaluating different models. One study [

42] compared rule-based (AIML) and generative (Sequence-to-Sequence) approaches, revealing a trade-off between user satisfaction and task completion for rule-based models, and superior information retrieval for generative models. Building upon the idea of comparative analysis, another study [

1] developed five chatbot models using various techniques and found limitations in pattern-matching approaches due to overfitting.

Generative models: The emergence of large language models like ChatGPT, have garnered significant interest for their ability to handle open-ended questions and generate creative text formats [

43]. In the context of educational administration, this translates to the potential for providing students with explanations, summaries, and even creative writing prompts. In their work, the authors of [

44] identified several key advantages of using ChatGPT in education. These include the ability to tailor learning to individual students, develop innovative assessment methods, and enhance students' critical thinking abilities. They suggest that by carefully considering both the potential benefits and drawbacks of ChatGPT, it can be used to improve the overall learning experience for university students.

Research Gap: The studies reviewed in this section showcase the potential of various chatbot approaches in educational settings. However, some limitations exist. Rule-based models can be inflexible for open-ended questions, while retrieval-based models may struggle with complex inquiries. Generative models, like ChatGPT, due to their reliance on statistical patterns in vast datasets can lead to inaccuracies, particularly in factual inquiries [

45]. Additionally, generative models may struggle to understand the nuances of human language and context, potentially leading to misleading or irrelevant responses. Our research proposes a hybrid chatbot model that leverages the strengths of these approaches to overcome these limitations. By combining rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative-based approaches, we aim to develop a more robust and adaptable model for handling diverse administrative tasks in educational institutions.

3. Materials and Methods

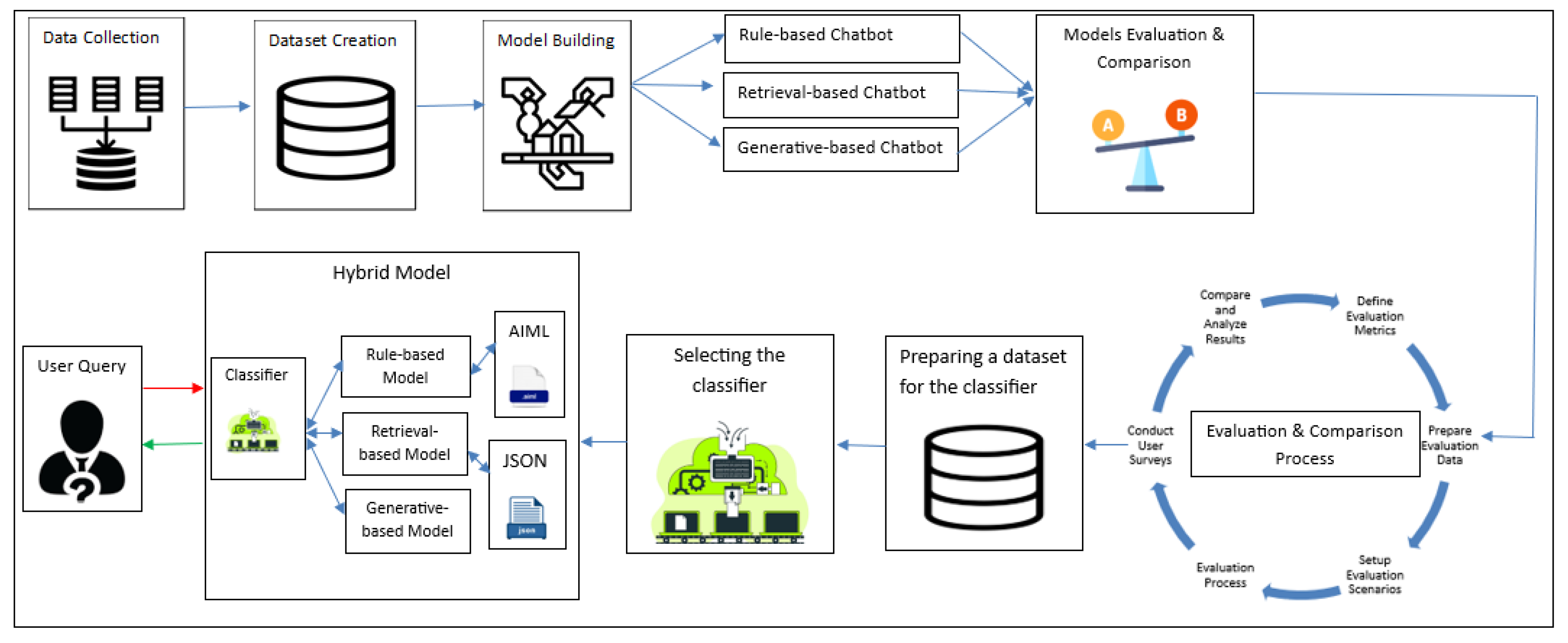

This section details the methods employed in the comparative analysis of rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative-based chatbots designed to address administrative inquiries within educational institutions, it also proposes the development and evaluation of a hybrid model that leverages the strengths of these individual approaches. The methodology, further illustrated in

Figure 1, encompasses five key steps: data collection, model development, model evaluation and comparison, classifier implementation, and model integration.

3.1. Data Collection and Dataset Creation

A dataset is crucial for training any model. Due to the lack of datasets specifically tailored to Sakarya University, we constructed a new dataset from scratch. This dataset comprises a collection of questions and corresponding answers stored in a text file format. To ensure clarity and organization, a consistent notation system has been adopted. Question sentences are marked with a "Q:" prefix, while answer sentences are denoted with an "A:". The data has been sourced from various channels: Sakarya University's FAQ pages, and social media groups where students posed questions about the university and questions were generated based on information available on the university's official websites. This comprehensive approach ensured the dataset captured a wide range of inquiries typically encountered by students. Additionally, incorporating valuable feedback from students further enriched the dataset's relevance. data pre-processing steps have been performed (removing punctuation and duplicate questions, segmenting long sentences into smaller units) to clean and organize the collected information. The resulting dataset encompasses 2253 lines of conversation, categorized into various domains such as Admissions and Registrations, Academic Affairs, Financial Matters, and Student Services. This structure ensures the dataset's broad coverage and addresses the needs of prospective, current, and foreign students at Sakarya University.

3.2. Models Creation

The core of this research hinges on the development and application of diverse models. This subsection, 3.2 Models Creation, delves into the specific steps taken to construct these models. We will detail the implementation of all three models: a rule-based approach, a retrieval-based approach, and a generative-based approach.

3.2.1. Rule-Based Chatbot

To develop a rule-based chatbot, Artificial Intelligence Markup Language (AIML) was selected. AIML is a widely used programming language for creating chatbots and virtual assistants. It is an XML-based language that uses pattern matching and natural language processing techniques to simulate conversation with human users [

46]. It has been opted for due to its simplicity, flexibility, and user-friendly syntax. AIML's built-in features enable efficient handling of diverse user queries [

46]. The Pandorabots platform has been utilized. Pandorabots is a platform that utilizes AIML to build and deploy chatbots which provides a user-friendly interface for defining AIML rules, managing the knowledge base, and integrating the chatbot [

47]. 637 categories were established from the dataset described in section 3.1. The development process can be summarized as follows:

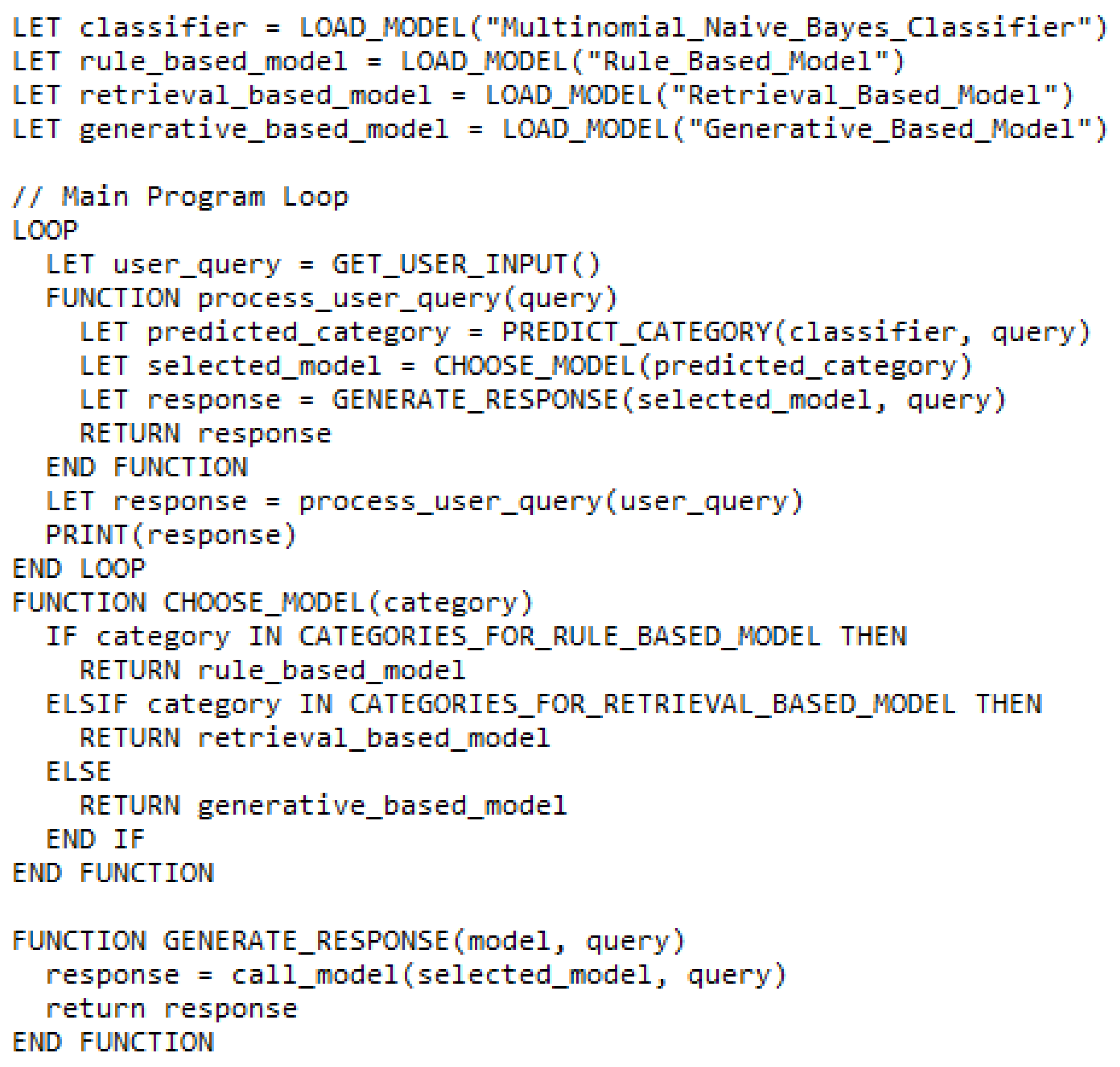

AIML File Generation: The Pandorabots playground was used to generate AIML files from the dataset, creating the initial chatbot prototype.

Prototype Integration: The prototype was then integrated into the Pandorabots framework, enabling user interaction.

User Testing: A group of 113 students (undergraduate and postgraduate) interacted with the chatbot.

Evaluation and Improvement: User interactions were logged and analyzed (elaborate on the specific aspects evaluated, e.g., response accuracy, user satisfaction). This analysis led to a review and enhancement of the chatbot's functionalities.

Redeployment: The improved version of the chatbot was redeployed for further user interaction.

Figure 2 shows the pseudocode for the built rule-based chatbot model, and

Figure 3 represents its graphical interface.

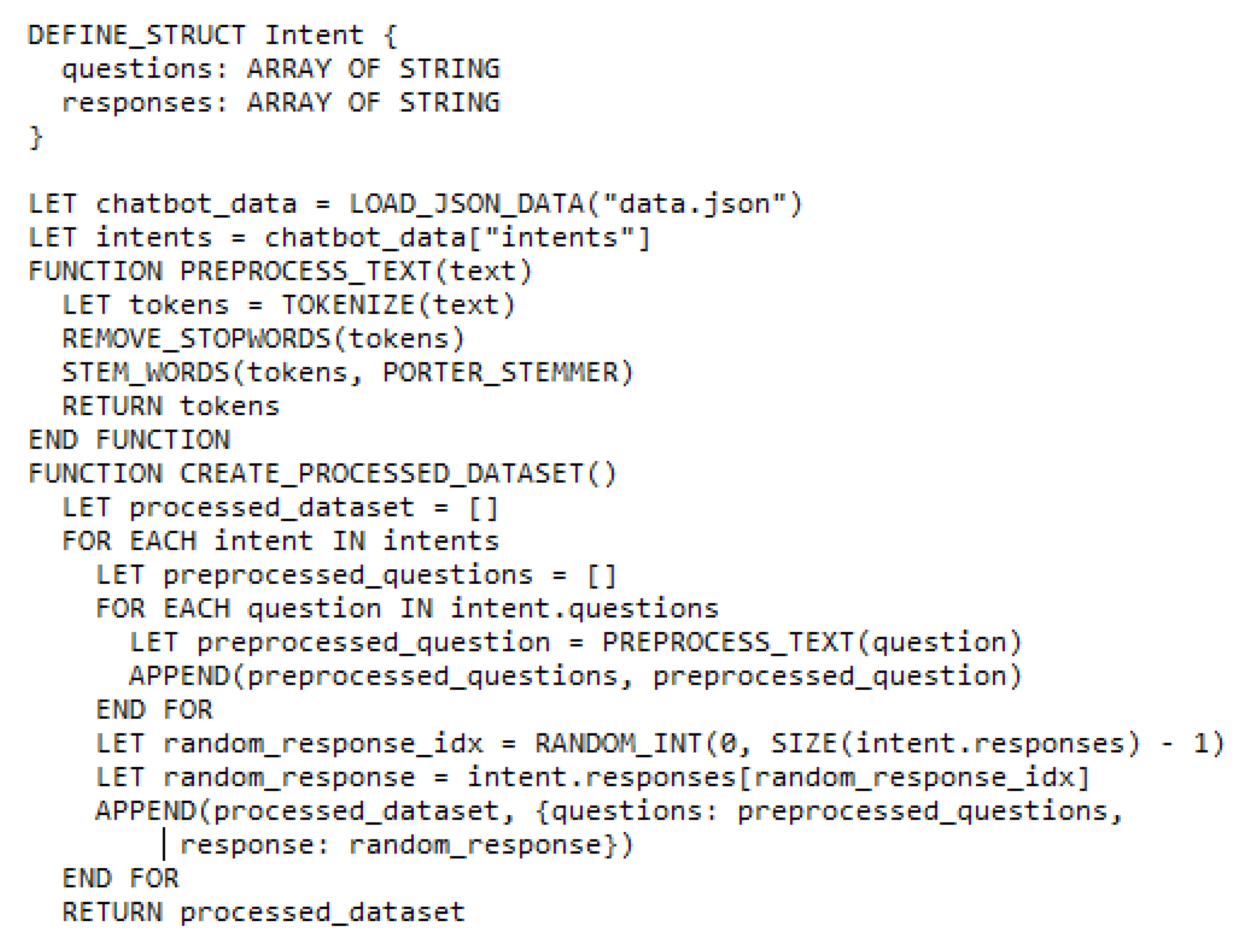

3.2.2. Retrieval-Based Chatbot

The retrieval-based chatbot leverages a JSON file to store information relevant to user inquiries. This file maintains data regarding Sakarya University, categorized into the same main categories as the dataset (section 3.1). The JSON structure includes:

intents: An array of intent objects, each representing a specific category such as ‘weather’, ‘courses’, and ‘tuition fees’.

Questions: An array of user queries or inputs associated with the intent.

Responses: An array of possible responses or answers the chatbot can provide related to the given intent.

Data pre-processing is crucial for the retrieval-based model. This involves:

Tokenization: Breaking down text into individual words or units.

Stopword removal: Eliminating common words that hold little meaning such as ‘the’, and ‘a’.

Stemming: Reducing words to their base form such as ‘running’ -> ‘run’. Porter Stemmer has been employed for this purpose.

Processed dataset creation: Combining the preprocessed questions (patterns) and corresponding preprocessed answers (randomly chosen from the response options).

TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) is a core technique used in this model. It is a numerical statistic used to evaluate the importance of a word to a document in a collection or corpus [

48]. A TF-IDF vectorizer is initialized to calculate the similarity matrix using cosine similarity. This step aims to determine the closest match between the user's input and the preprocessed questions within the dataset.

Entity extraction involves identifying specific elements within the user's input that are relevant to the query. This is achieved through a function named extract entities. It performs the following actions:

Tokenization: Breaking down the user input into individual words.

Pattern matching: Checking the user input against predefined patterns associated with the intent.

Entity extraction: Utilizing regular expressions to extract specific entities from the matched patterns.

Finally, the generated response function takes the user input and generates a response. This function:

Preprocesses the user input.

Calculate the similarity between the preprocessed input and the preprocessed dataset questions using cosine similarity.

Identifies the most similar question (intent) based on the calculated similarity scores.

Extract entities relevant to the identified intent using the extract_entities function.

Returns the corresponding response associated with the most similar question and extracted entities.

Figure 4 illustrates the pseudocode for the constructed retrieval-based chatbot model, while

Figure 5 displays its graphical interface.

3.2.3. Generative-Based Chatbot

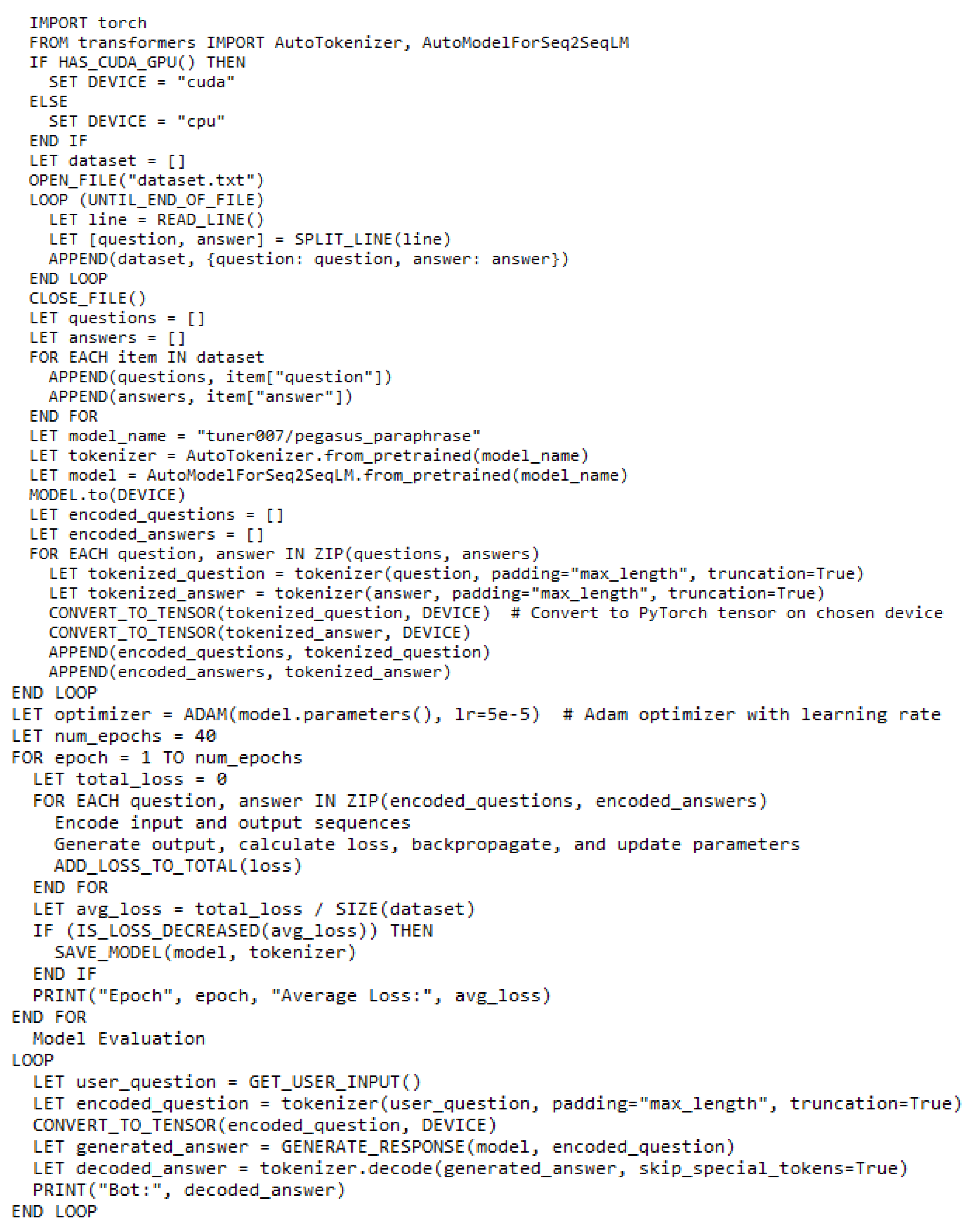

This section clarifies the fine-tuning process employed to convert a pre-trained language model into a functional chatbot using the Hugging Face transformers library. The objective is to fine-tune the model on a custom Q&A dataset (section 3.1) and leverage it to generate responses to user queries. The generative-based chatbot implementation can be summarized as follows:

Library Imports: Necessary libraries are imported, including torch for PyTorch functionalities and AutoTokenizer and AutoModelForSeq2SeqLM from the transformers library for handling the pre-trained model and tokenizer.

GPU Availability Check: The code checks for a CUDA-enabled GPU to accelerate computations. If available, the GPU is used; otherwise, the CPU takes over.

Loading the Dataset: The dataset created in section 3.1 is loaded line by line, separating each line into individual questions and answers.

Separating Questions and Answers: The entire dataset is traversed to split questions and answers into distinct lists.

Loading Pre-trained Model and Tokenizer: The pre-trained model ("tuner007/pegasus_paraphrase") is specified, and the corresponding tokenizer and model are loaded using AutoTokenizer and AutoModelForSeq2SeqLM. The loaded model is then transferred to the chosen device (GPU or CPU).

Tokenization and Encoding: Both questions and answers are tokenized and encoded using the loaded tokenizer. Padding and truncation are applied to ensure sequences adhere to specific length requirements. These encoded sequences are then converted into PyTorch tensors.

Fine-tuning the Model: Fine-tuning involves the following sub-steps:

Optimizer Selection: An Adam optimizer is chosen and initialized with a learning rate of 5e-5. The fine-tuning process iterates through 40 epochs.

Encoding Input and Output Sequences: For each epoch, the model encodes the input and output sequences for each Q&A pair.

Generating Output and Calculating Loss: The model generates an output sequence based on the input sequence and calculates the loss against the provided target output sequence.

Backpropagation and Updating Model Parameters: The calculated loss is accumulated and used to update the model's parameters through backpropagation.

Saving Model State: After each epoch, the model's state (including both model weights and tokenizer) is saved whenever a decrease in the average loss is observed.

- 8.

Model Evaluation: The fine-tuned model's performance is assessed using the training set.

- 9.

User Interaction with Fine-tuned Model: The final step involves user interaction with the chatbot:

Optimizer Selection: An Adam optimizer is chosen and initialized with a learning rate of 5e-5. The fine-tuning process iterates through 40 epochs.

Encoding Input and Output Sequences: For each epoch, the model encodes the input and output sequences for each Q&A pair.

Generating Output and Calculating Loss: The model generates an output sequence based on the input sequence and calculates the loss against the provided target output sequence.

Backpropagation and Updating Model Parameters: The calculated loss is accumulated and used to update the model's parameters through backpropagation.

Saving Model State: After each epoch, the model's state (including both model weights and tokenizer) is saved whenever a decrease in the average loss is observed.

Figure 6.

Generative-based model algorithm.

Figure 6.

Generative-based model algorithm.

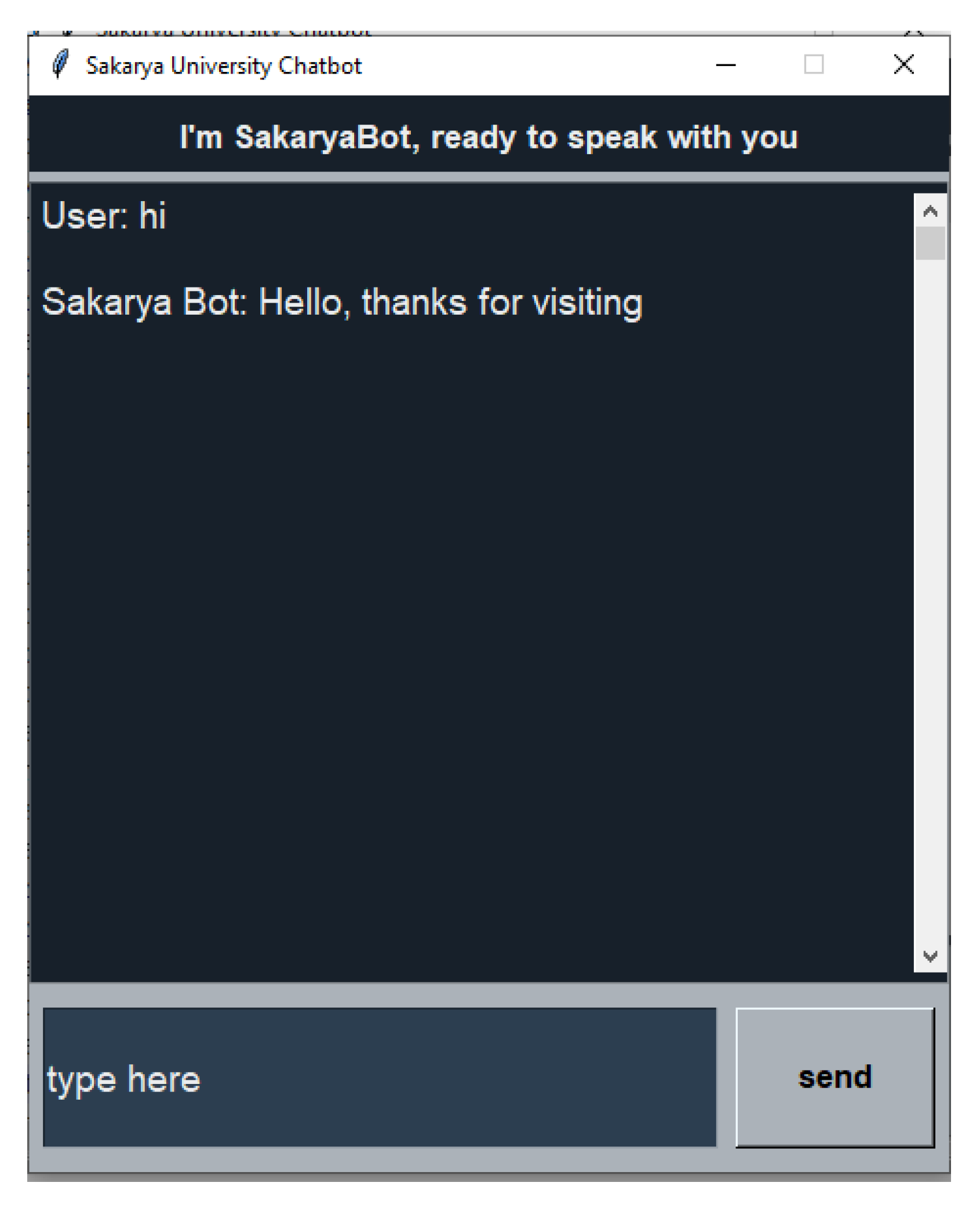

Figure 7.

Generative-based chatbot GUI.

Figure 7.

Generative-based chatbot GUI.

3.3. Models’ Evaluation and Comparison

This section presents a comparative analysis of three prominent chatbot models utilized in educational institutions: rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative-based models. Through a rigorous evaluation process to:

Unveil the strengths, weaknesses, and unique performance characteristics of each approach.

Lay the groundwork for identifying advancements and exploring the feasibility of a hybrid model that leverages the most advantageous features of all three approaches.

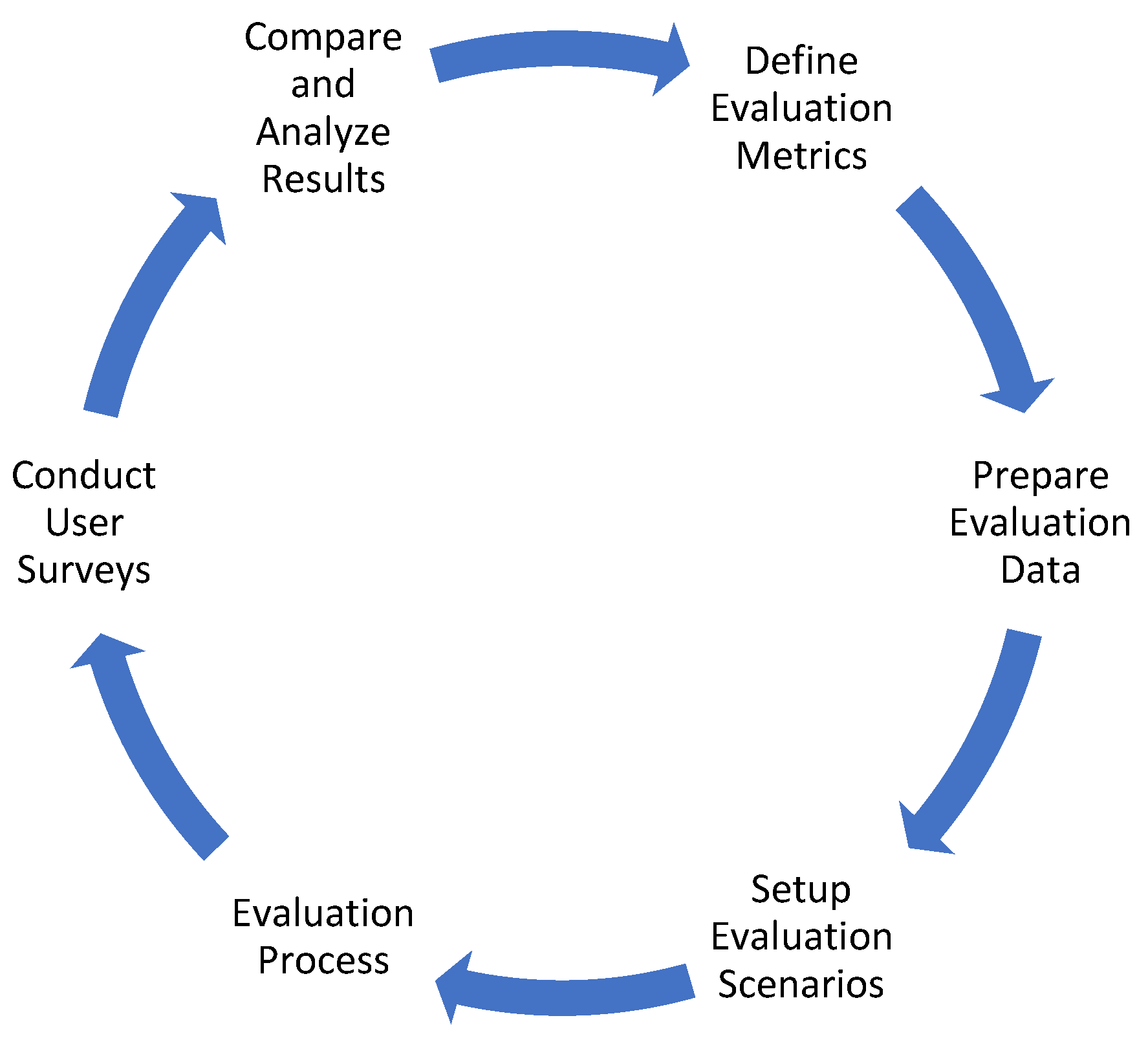

Figure 8 visually depicts the lifecycle of the comparison process, providing a roadmap for the subsequent sections.

3.3.1. Define Evaluation Metrics

The initial step involves determining relevant metrics to assess the chatbot models' performance, the core metrics include:

Accuracy: Percentage of inquiries answered correctly and relevantly.

Precision: Proportion of responses that are topical and pertinent to the user's query.

Recall: Proportion of relevant questions accurately answered.

F1 Score: Harmonic means of precision and recall, offering a balanced view.

In addition to the core metrics, additional metrics have been considered such as:

Response Time: Average time taken to generate a response.

User Satisfaction and Engagement: Subjective metrics assessed through surveys to gauge user perception of helpfulness, ease of use, and overall effectiveness.

Flexibility: Ability to adapt to new information or situations such as ease of adding new knowledge, handling unexpected queries.

3.3.2. Prepare Evaluation Data

To ensure an accurate evaluation, a dedicated dataset was compiled using real-world data, the factors have been considered are:

Data Source: Extracted from the last updated FAQ page on Sakarya University's main website.

Selection Criteria: 300 representative queries and corresponding answers, representing approximately 20% of the total training dataset size, were chosen to capture the diverse range of user inquiries typically encountered in the university setting.

Rationale: Incorporating these authentic and up-to-date queries aims to assess the models' performance in accurately understanding and responding to inquiries specific to Sakarya University.

3.3.3. Setup Evaluation Scenarios

Three distinct scenarios or use cases are defined to represent the digital assistant's functionalities:

Scenario 1 (Prospective Students): Admissions, academics, and general inquiries.

Scenario 2 (Enrolled Students): Registrations, tuition fees, courses, and campus facilities.

Scenario 3 (Foreign Students): Admission and registration, tuition fees, weather, language proficiency requirements, and accommodation.

These scenarios encompass various domains and topics relevant to Sakarya University.

3.3.4. Evaluation Process

In this step, the specific evaluation approaches for each model have been outlined:

- 2.

Retrieval-based Chatbot:

Focus: Selecting the most relevant response from a predefined set.

Metrics: Use accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score to evaluate response selection accuracy.

- 3.

Generative-based Chatbot:

Focus: Assess the quality of generated responses.

Factors: Consider response coherence, grammar, and relevance to the user query.

3.3.5. Conduct User Surveys

User surveys were conducted to gather feedback on:

Satisfaction Level: How satisfied users were with the interaction.

Perceived Usefulness: How helpful users found the chatbot.

Overall User Experience: Ease of use and overall impression.

A total of 267 undergraduate students participated by responding to the 10-question survey (

Table 1). All user interactions and feedback were recorded for further analysis.

3.3.6. Compare and Analyze Results

This final step involves:

Comparing performance: Analyze the performance of each model across the different evaluation metrics and user feedback.

Identifying strengths and weaknesses: Examine each model's effectiveness in terms of accuracy, response quality, user satisfaction, and other relevant factors.

The purpose of evaluating the models was to:

Review and improve: The evaluation aims to identify areas for improvement in both the dataset and the design of the models.

Hybrid model development: By comparing the models' strengths, the analysis seeks to explore the possibility of integrating them into a single, enhanced hybrid model.

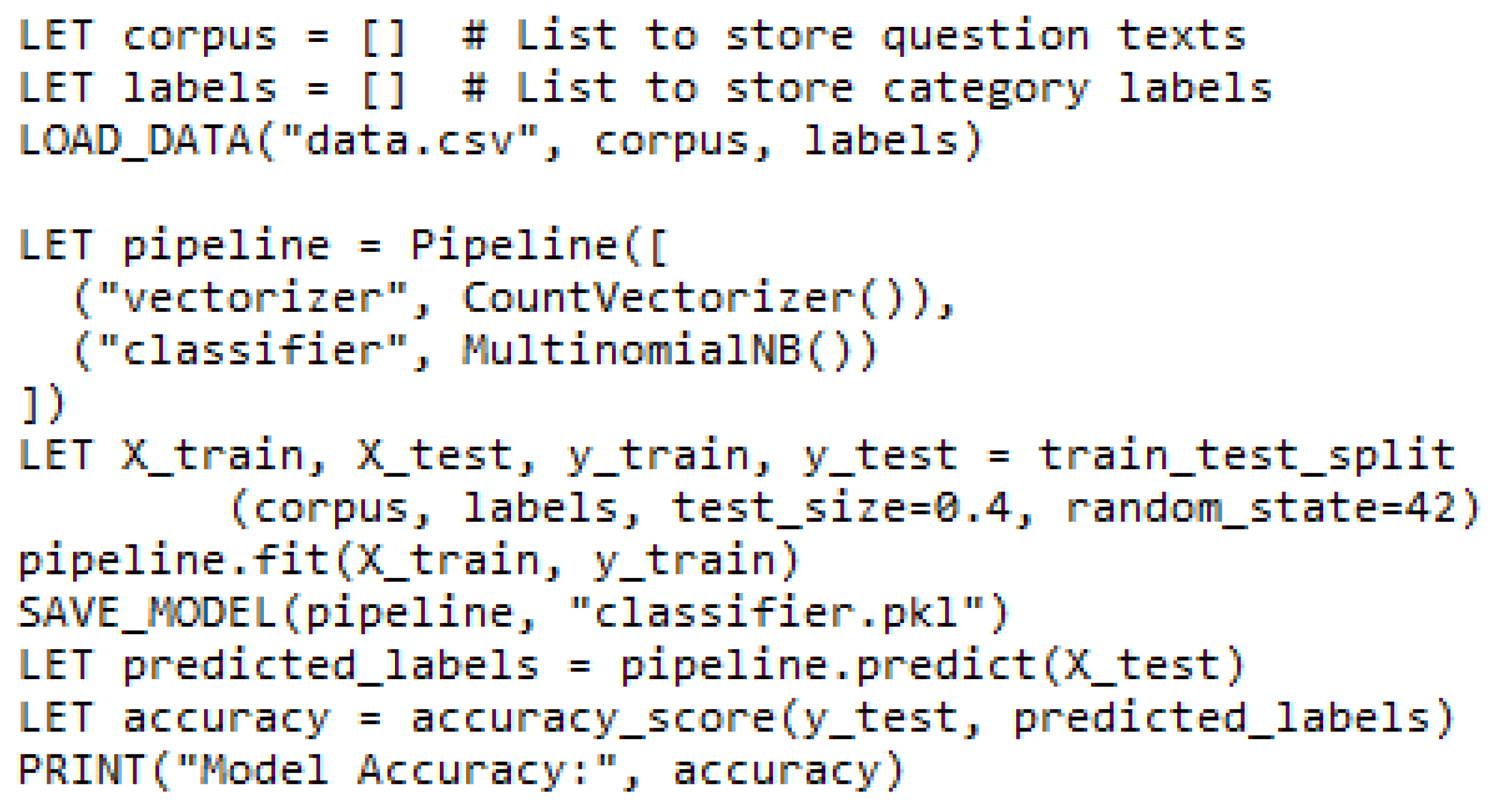

3.4. Classifier Implementation

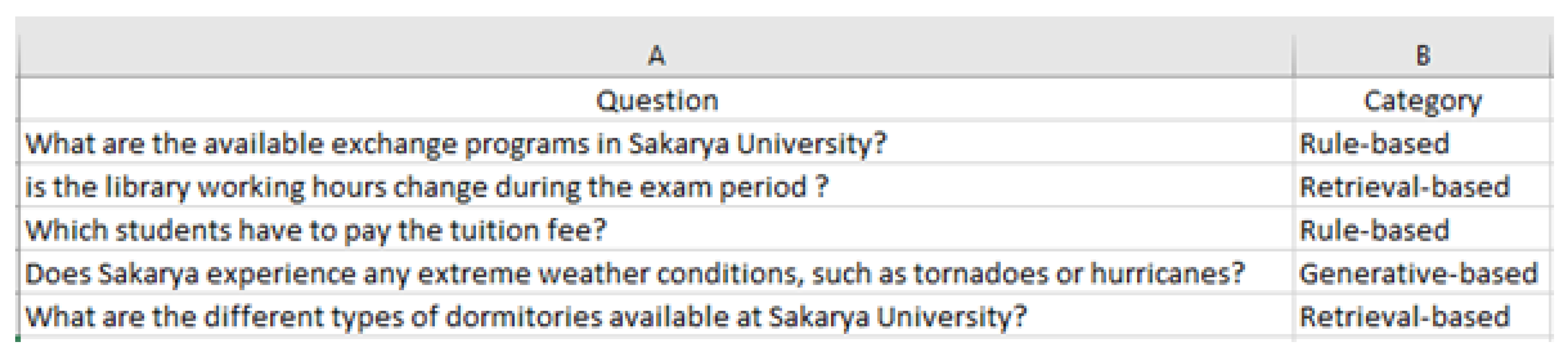

The evaluation process revealed the distinct strengths of each chatbot model in handling administrative tasks across various university-related categories. To efficiently route user queries to the most suitable model, a classifier is implemented. This section details the chosen approach and its implementation steps.

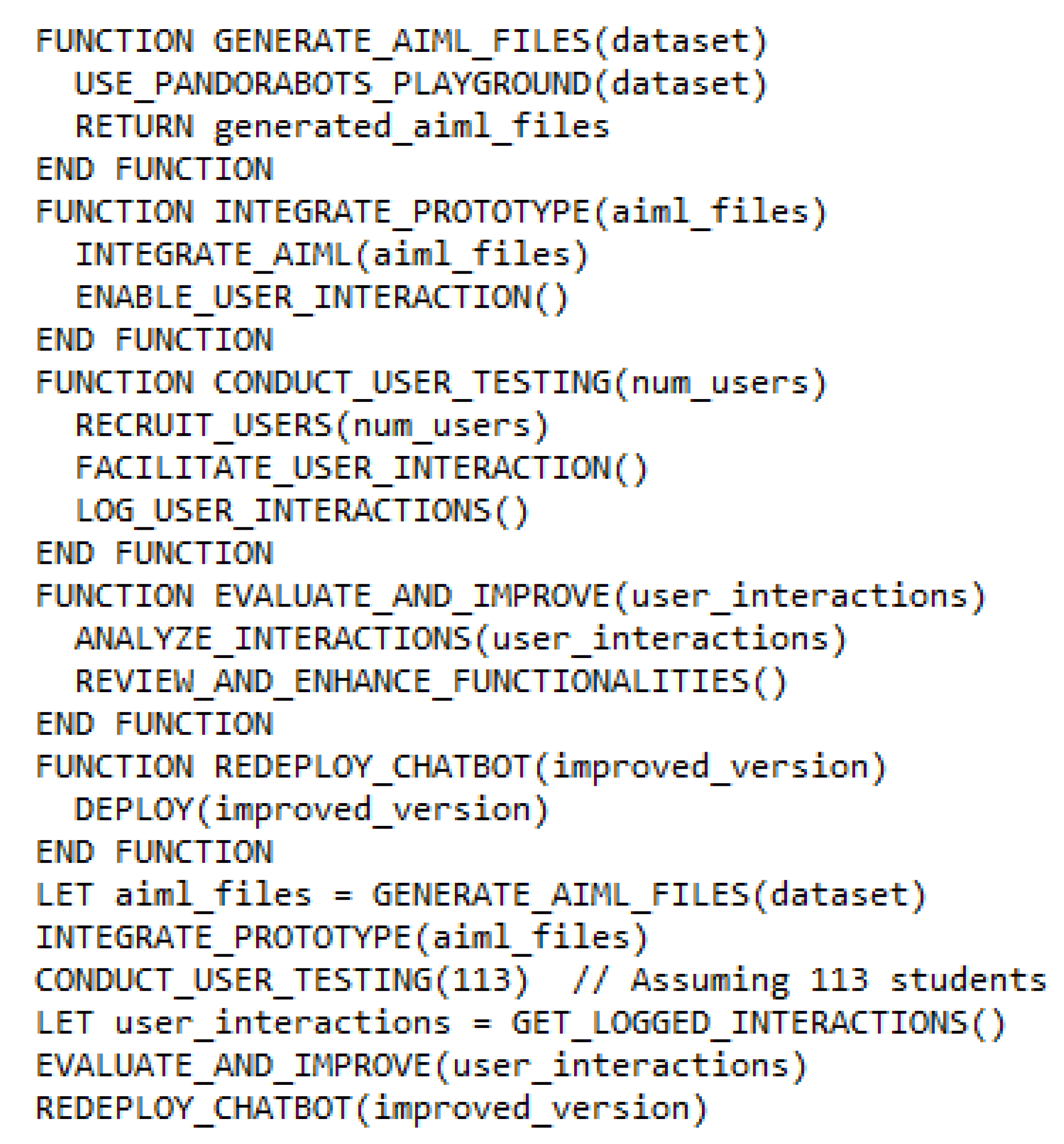

Figure 9 presents the pseudocode for the Multinomial Naive Bayes Classifier, while

Figure 10 displays a sample of the classifier dataset.

3.4.1. Classifier Selection:

A Multinomial Naive Bayes classifier is employed for category classification. A Multinomial Naive Bayes Classifier is a probabilistic machine learning algorithm used for text classification [

49]. It assumes that the occurrence of a word in a document is independent of the occurrence of other words. due to its:

Simplicity: Easy to understand and implement.

Efficiency: Performs well with large datasets and requires minimal training data compared to some complex models.

Effectiveness: Often yields competitive results for text classification tasks.

3.4.2. Data Preparation:

A dedicated dataset (

Figure 10) was created for classifier training, containing:

Question Column: Represents the input user query as text.

Category Column: Represents the corresponding category or class such as admissions, registration, and fees.

3.4.3. Implementation Steps:

Data Loading: The Question and Category columns are loaded into separate lists, typically named corpus and labels, respectively, for easier processing.

Text Classification Pipeline:

Text Vectorization: The CountVectorizer transforms textual data into numerical features, enabling the classifier to process the text.

Classification: The MultinomialNB algorithm implements the Naive Bayes classification model to categorize the text data based on the learned patterns.

- 3.

Data Splitting:

The train_test_split function from scikit-learn is used to divide the dataset into training and testing sets.

A common practice is to allocate 40% of the data for testing (test_size=0.4) to assess the classifier's performance on unseen data.

Setting the random_state parameter to a fixed value (e.g., 42) ensures reproducibility, meaning the same data split will occur when the code is run multiple times.

- 4.

Classifier Training:

The text data from the training set is vectorized using CountVectorizer.

The transformed numerical features are then used to train the Naive Bayes model, enabling it to learn the relationships between text patterns and their corresponding categories.

- 5.

Model Saving:

The trained classifier is saved to a file (classifier.pkl) using the joblib.dump function.

This step allows for reusing the trained model for future predictions without the need for retraining, saving computational resources.

- 6.

Evaluation:

The performance of the trained classifier is assessed using the testing set (X_test).

The predict method is employed to predict category labels for the unseen test data.

The accuracy_score function is used to evaluate the model's accuracy by comparing the predicted labels with the actual labels (y_test).

Accuracy represents the percentage of correctly classified instances.

Figure 9.

Multinomial Naive Bayes Classifier algorithm.

Figure 9.

Multinomial Naive Bayes Classifier algorithm.

Figure 10.

Sample of Classifier Dataset.

Figure 10.

Sample of Classifier Dataset.

3.5. Models Integration (Hybrid Model)

Building upon the individual strengths of the rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative-based models, this section describes their integration into a cohesive framework, forming a hybrid chatbot system.

The integration process revolves around two key components:

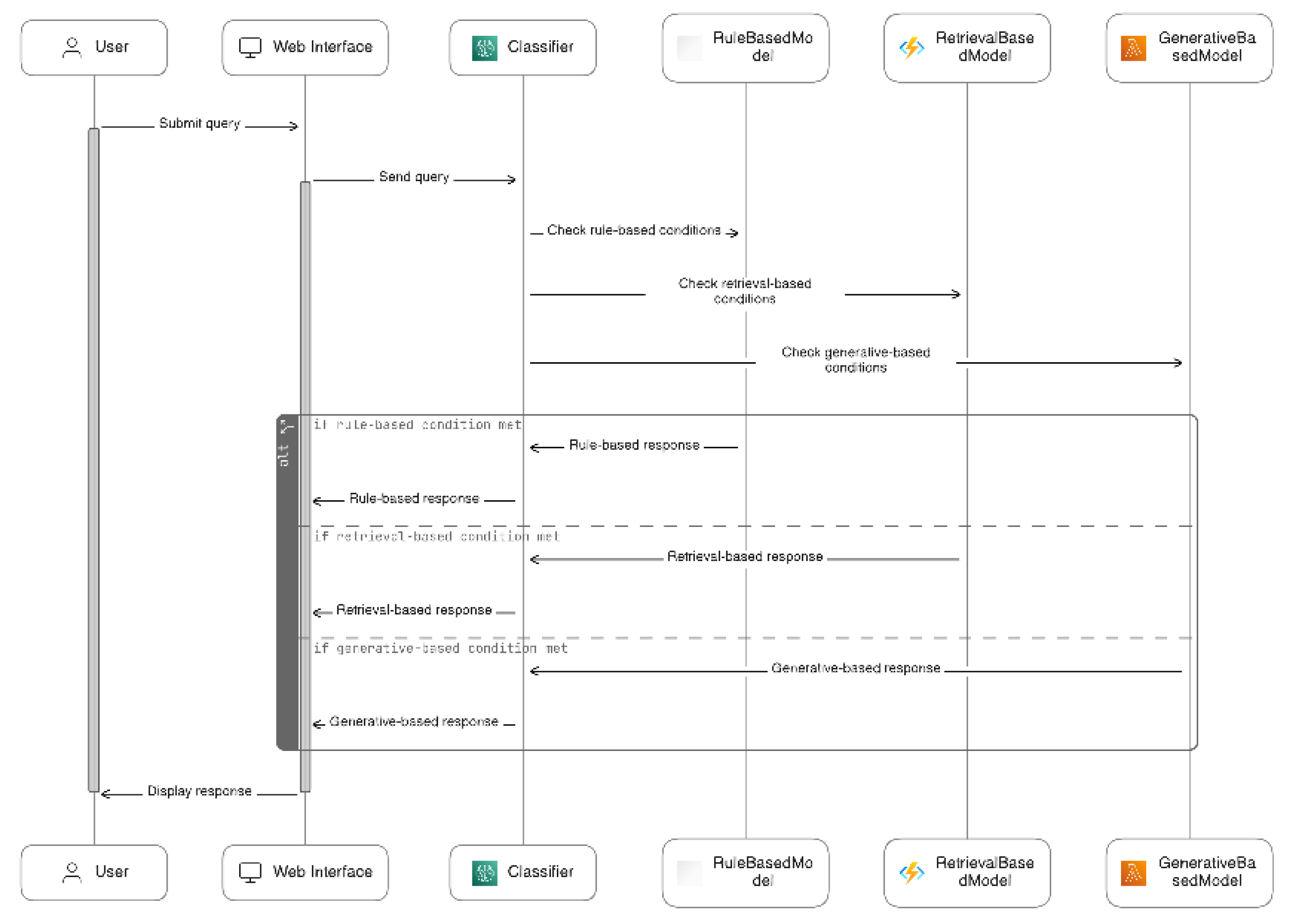

Figure 11 Represents the pseudocode for the proposed hybrid model, and

Figure 12 Describes it’s process flow which can be summarized as:

a. Category Prediction: The function leverages the trained classifier to predict the category (e.g., admissions, registration, fees) that the query most likely belongs to.

b. Model Selection: Based on the predicted category, the function directs the query to the most suitable model:

Rule-based model: Well-suited for well-defined queries with a clear answer in the knowledge base.

Retrieval-based model: Effective for retrieving relevant responses from a predefined set when the answer might involve variations in phrasing.

Generative-based model: Ideal for handling open-ended questions, complex inquiries, or situations where a creative response is desired.

- 3.

Model Response Generation: The selected model processes the query and generates a response tailored to the user's needs.

- 4.

Response Delivery: The generated response is returned from the process_user_query(query) function to the main program loop.

- 5.

User Interface Interaction: The main program loop displays the response to the user through the system's interface, completing the interaction cycle.

Figure 11.

Hybrid model algorithm.

Figure 11.

Hybrid model algorithm.

Figure 12.

Hybrid Model Flow Diagram.

Figure 12.

Hybrid Model Flow Diagram.

4. Results And Discussion

For randomly selected 300 different queries, the performance of all three chatbot approaches was evaluated. The rule-based chatbot achieved a matching accuracy of 73.33% for user queries to predefined rules, effectively generating appropriate responses. It covered 63.33% of the rules defined within AIML categories (

Table 2).

On the other hand, the retrieval-based chatbot demonstrated a higher performance with a score of 83.33% in selecting the most relevant response from a predefined set of responses. Additionally, it provided a wide range of response diversity, enhancing the overall user experience (

Table 3).

To evaluate the generative-based chatbot, the chatbot's responses for the same set of queries were assessed by an English specialist annotator. The manual evaluation using the Likert scale (strongly agree(5), agree(4) , neutral(3), disagree(2), strongly disagree(1)) revealed that the model achieved scores of 72.12%, 75.42%, 87.23% for response quality, coherence, grammar, and language fluency, respectively (

Table 4).

The evaluation results highlighted the need for improvements in all three chatbot models and the dataset as well. For the rule-based model, an expansion of the rules defined within AIML categories was necessary to cover a wider range of user queries. As a result, an additional 112 categories were added to enhance the model's coverage. In the case of the retrieval-based chatbot, the random() function was activated to introduce more response diversity, especially for queries that could have multiple valid answers. This adjustment aimed to enhance the user experience and provide varied responses. Furthermore, to improve the performance of the generative-based model, the dataset was modified to include more examples that consider comprehension and context, thereby ensuring the generation of more contextually appropriate and coherent responses.

Table 5 summarizes the results of the questionnaire administered to users who interacted with all three models. The scores were calculated for each question and for all three models using Equation 1. User satisfaction rates were determined based on questions 2, 6, and 7. The retrieval-based model received the highest score in user satisfaction. Model usefulness was assessed through questions 3, 8, and 9, and the rule-based model achieved the highest score in this category. User engagement was evaluated using questions 5 and 10, and the rule-based model also scored highest in this aspect. Question 4 focused on measuring human-like conversation, and the generative-based model received the highest score in this area.

The evaluation results and user feedback revealed distinct advantages for each chatbot model. The rule-based model demonstrated superior performance in terms of model usefulness and user engagement. This was primarily attributed to its ability to provide accurate answers in specific categories such as tuition fees and course schedules. Additionally, the rule-based model offered an attractive user interface through the utilization of rich media tags provided by the AIML playground (Pandorabots). The retrieval-based model outperformed the others in terms of response selection, leading to higher user satisfaction. The generative-based model excelled in delivering a more human-like conversation experience, owing to its implementation of a generative pre-trained model with a transformer architecture. To assess the strengths of each model in handling various administrative tasks within Sakarya University and to propose the hybrid model, a detailed analysis was conducted on all the conversations. The task completion rates for each model are summarized in

Table 6. The results indicate that the rule-based model performed well in the categories of Admissions and Registrations (87.33%) and Financial Matters (89.56%). The retrieval-based model achieved the best results in the categories of Academic Affairs (84.67%), Student Services (88.94%), and Campus Life (91.44%). On the other hand, the generative-based model excelled in the categories of General Information (100%) and Cross-domain Queries (73.12%).

This categorization resulted from the analysis of the study, where the specific chatbot implementation, quality of data, and training provided to the chatbot models contribute to the different strengths exhibited by each chatbot model in specific task categories. As part of the evaluation process, the individual responses of the chatbots have been analyzed.

Table 7 presents the various response categories.

Using the information provided in

Table 8, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F-Measure were computed utilizing the following formulas [

50]:

Accuracy measures the overall correctness of the model's predictions. the retrieval-based model still has the highest accuracy among the three models. The accuracy alone is not sufficient to evaluate a model's performance comprehensively. Precision and recall provide additional insights into the model's ability to correctly identify positive instances and minimize false positives or false negatives, respectively. Precision is a measure of how many of the responses predicted as positive are actually correct, the retrieval-based model still has the highest precision, meaning that when it predicts a response as positive, it is correct 78% of the time. Recall measures the ability of the model to correctly identify positive responses, the retrieval-based model still has the highest recall, indicating that it can correctly identify positive responses 88% of the time. F1-Measure is the harmonic mean of precision and recall and provides a single metric to evaluate the overall performance, The retrieval-based model still has the highest F1-Measure, indicating a balanced performance in terms of precision and recall.

The purpose of evaluating the models was to review and make the necessary modifications to both the dataset and the design of the models. Additionally, the purpose of comparing the models was to identify their respective strengths to integrate them into a single hybrid model. The models' evaluation has been completed and required modifications have been made to both the dataset and the design of the models. Based on the models' comparison, the polynomial Naïve Bayes classifier has been implemented to forward specific types of queries to different models. For instance, queries related to 'Admissions and Registrations' and 'Financial Matters' are directed to the rule-based model. 'Academic Affairs', 'Student Services', and 'Campus Life' queries are handled by the retrieval-based chatbot, while 'General Information' and 'Cross-domain' queries are addressed by the generative-based model.

Table 9 demonstrates the advancements and accuracy achieved by the hybrid model. The evaluation of the model utilized the updated dataset, with an equal number of queries employed for all three models. The results showcased a noteworthy improvement in comparison to the rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative-based models. This progress serves as evidence that the hybrid model effectively utilizes the strengths of all three models. This achievement stands as the primary contribution of this work.

According to [

2] assessing the practicality of Chatbot systems requires employing a suitable method to evaluate the efficiency of the software engineering product, along with a broader and statistically meaningful sample of users.

A detailed comparison in

Table 10 reveals the proposed hybrid model surpasses all existing state-of-the-art administrative educational chatbots. This superiority is achieved through combining the strengths of each model (rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative-based models). For example, the hybrid model leverages the rule-based system's efficiency for handling common tasks, the retrieval-based system's ability to access and deliver relevant information, and the generative-based system's capacity for natural language understanding and response generation.

5. CONCLUSIONs

This study investigated the potential of hybrid chatbot models for enhancing educational administration. By comparing rule-based, retrieval-based, and generative-based approaches, we identified distinct strengths and weaknesses in handling student inquiries. Our findings revealed that rule-based models excel in domains such as Admissions and Registrations, and Financial Matters, while retrieval-based models demonstrate superior performance in Academic Affairs, Student Services, and Campus Life. Generative models proved effective in handling Greeting and General Information inquiries as well as cross-domain queries. Our proposed hybrid model, which combines these approaches and employs a query routing classifier, demonstrated an accuracy improvement over individual models. This enhancement underscores the model's potential to optimize efficiency and user experience within educational settings. Benchmarking against state-of-the-art solutions further solidified the model's competitive performance. Future research should focus on expanding the dataset for more robust model training, exploring advanced classification algorithms such as deep learning-based techniques that could further enhance query routing and overall system performance, and conducting comprehensive user studies to assess the model's impact on student satisfaction and administrative efficiency.

Authors’ Contribution

KA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing the Initial Draft, and Revision; CO: Conceptualization and Supervision. TA: Methodology, Restructuring the Initial Draft, and Revision. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- G. Attigeri and A. Agrawal, “Advanced NLP Models for Technical University Information Chatbots : Development and Comparative Analysis,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, no. February, pp. 29633–29647, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. W. Okonkwo and A. Ade-Ibijola, “Chatbots applications in education: A systematic review,” Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell., vol. 2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. T. Nguyen, A. D. Le, H. T. Hoang, and T. Nguyen, “NEU-chatbot: Chatbot for admission of National Economics University,” Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell., vol. 2, p. 100036, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Dibitonto, K. Leszczynska, F. Tazzi, and C. M. Medaglia, “Chatbot in a Campus Environment : Design of LiSA , a Virtual Assistant to Help Students in Their University Life,” in Human-Computer Interaction. Interaction Technologies, Cham., M. Kurosu, Ed. Springer International Publishing, 2018, pp. 103–116. [CrossRef]

- T. Lopez and M. Qamber, “The Benefits and Drawbacks of Implementing Chatbots in Higher Education,” no. March, 2022.

- P. P. Ray, “ChatGPT: A comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future scope,” Internet Things Cyber-Physical Syst., vol. 3, no. March, pp. 121–154, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Rukhiran and P. Netinant, “Automated information retrieval and services of graduate school using chatbot system,” in International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), 2022, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 5330–5338. [CrossRef]

- D. Al-ghadhban and N. Al-twairesh, “Nabiha : An Arabic Dialect Chatbot,” Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl., vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 452–459, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. El Hefny, Y. Mansy, M. Abdallah, and S. Abdennadher, “Jooka : A Bilingual Chatbot for University Admission,” in Trends and Applications in Information Systems and Technologies, 2021, pp. 671–681. [CrossRef]

- R. Lucien and S. Park, “Design and Development of an Advising Chatbot as a Student Support Intervention in a University System,” TechTrends, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 79–90, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. N. Lam, L. H. Nguy, V. L. Le, and J. Kalita, “A Transformer-Based Educational Virtual Assistant Using Diacriticized Latin Script,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, no. August, pp. 90094–90104, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Man, O. Matei, T. Faragau, L. Andreica, and D. Daraba, “The Innovative Use of Intelligent Chatbot for Sustainable Health Education Admission Process: Learnt Lessons and Good Practices,” Appl. Sci., vol. 13, no. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Agus Santoso et al., “Dinus Intelligent Assistance (DINA) Chatbot for University Admission Services,” Proc. - 2018 Int. Semin. Appl. Technol. Inf. Commun. Creat. Technol. Hum. Life, iSemantic 2018, pp. 417–423, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Sakulwichitsintu, “ParichartBOT: a chatbot for automatic answering for postgraduate students of an open university,” Int. J. Inf. Technol., vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 1387–1397, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Udupa, “Application of artificial intelligence for university information system,” Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell., vol. 114, p. 105038, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Thalaya and K. Puritat, “BCNPYLIB CHAT BOT: The artificial intelligence Chatbot for library services in college of nursing,” in 2022 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON), 2022, pp. 247–251. [CrossRef]

- S. Rodriguez and C. Mune, “Uncoding library chatbots: deploying a new virtual reference tool at the San Jose State University library,” Ref. Serv. Rev., vol. 50, no. 3–4, pp. 392–405, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Isaev, R. Gumerov, G. Esenalieva, R. R. Mekuria, and E. Doszhanov, “HIVA: Holographic Intellectual Voice Assistant,” Proc. - 2023 17th Int. Conf. Electron. Comput. Comput. ICECCO 2023, pp. 1–6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Barzola-monteses, S. Member, and J. Guillén-mirabá, “CSM : a Chatbot Solution to Manage Student Questions About payments and,” vol. 4, pp. 1–12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Parkar, Y. Payare, K. Mithari, J. Nambiar, and J. Gupta, “AI and Web-Based Interactive College Enquiry Chatbot,” Proc. 13th Int. Conf. Electron. Comput. Artif. Intell., pp. 1–5, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Nikhath et al., “An Intelligent College Enquiry Bot using NLP and Deep Learning based techniques,” 2022 Int. Conf. Adv. Technol. (CONAT ), pp. 1–6, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. B. K. Md. Abdullah Al Muid, Md. Masum Reza, M. M. Reza, R. Bin Kalim, N. Ahmed, M. T. Habib, and M. S. Rahman, “Edubot: An unsupervised domain-specific chatbot for educational institutions,” Lect. Notes Networks Syst., vol. 144, pp. 166–174, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. A. Al-Madi, K. A. Maria, M. A. Al-Madi, M. A. Alia, and E. A. Maria, “An Intelligent Arabic Chatbot System Proposed Framework,” 2021 Int. Conf. Inf. Technol., pp. 592–597, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Agung and S. Gunawan, “Ava: knowledge-based chatbot as virtual assistant in university,” ICIC Express Lett. Part B Appl., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 437–444, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Dinh and T. K. Tran, “EduChat: An AI-Based Chatbot for University-Related Information Using a Hybrid Approach,” Appl. Sci., vol. 13, no. 22, p. 12446, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Lalwani, S. Bhalotia, A. Pal, S. Bisen, and V. Rathod, “Implementation of a Chat Bot System using AI and NLP,” Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Sci. Technol., vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 26–30, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. P. and J. S. L. Galko, “Improving the user experience of electronic university enrollment,” in 2018 16th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), 2018, pp. 179–184. [CrossRef]

- W. Villegas-ch, J. Garc, K. Mullo-ca, S. Santiago, and M. Roman-cañizares, “Implementation of a Virtual Assistant for the Academic Management of a University with the Use of Artificial Intelligence,” Futur. Internet, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 97, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Giannos and O. Delardas, “Performance of ChatGPT on UK Standardized Admission Tests: Insights from the BMAT, TMUA, LNAT, and TSA Examinations,” JMIR Med. Educ., vol. 9, pp. 1–7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Sushmitha, S. Ramya, and G. M. Gandhi, “College Chatbot using Natural Language Processing for Student Queries,” vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 25549–25553, 2020.

- N. N. Khin and K. M. Soe, “Question Answering based University Chatbot using Sequence to Sequence Model,” 2020 23rd Conf. Orient. COCOSDA Int. Comm. Co-ord. Stand. Speech Databases Assess. Tech., pp. 55–59, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. W. Chandra and S. Suyanto, “Indonesian chatbot of university admission using a question answering system based on sequence-to-sequence model,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 157, pp. 367–374, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Sinha, S. Basak, Y. Dey, and A. Mondal, “An Educational Chatbot for Answering Queries,” in Emerging Technology in Modelling and Graphics, 2020, pp. 55–60. [CrossRef]

- H. T. Hien, P.-N. Cuong, L. N. H. Nam, H. L. T. K. Nhung, and L. D. Thang, “Intelligent Assistants in Higher-Education Environments: The FIT-EBot, a Chatbot for Administrative and Learning Support,” in Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Information and Communication Technology (SoICT ’18), 2018, pp. 69–76. [CrossRef]

- K. Lee, J. Jo, and J. Kim, “Can Chatbots Help Reduce the Workload of Administrative Of fi cers ? - Implementing and Deploying FAQ Chatbot Service in a University,” in 21st International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, HCI International 2019, 2019, pp. 348–354. [CrossRef]

- M. Mekni, Z. Baani, and D. Sulieman, “A Smart Virtual Assistant for Students,” in Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Applications of Intelligent Systems (APPIS 2020), 2020, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- S. Alqaidi, W. Alharbi, and O. Almatrafi, “A support system for formal college students: A case study of a community-based app augmented with a chatbot,” 2021 19th Int. Conf. Inf. Technol. Based High. Educ. Train. (ITHET ), vol. 978, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Dinesh, M. R. Anala, T. T. Newton, and G. R. Smitha, “AI Bot for Academic Schedules using Rasa,” Proc. 2021 IEEE Int. Conf. Innov. Comput. Intell. Commun. Smart Electr. Syst. ICSES 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Windiatmoko, A. F. Hidayatullah, and ..., “Developing FB chatbot based on deep learning using RASA framework for university enquiries,” in IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng, 2020, p. 1077 012060. [CrossRef]

- N. Alzaabi, M. Mohamed, H. Almansoori, M. Alhosani, and N. Ababneh, “ADPOLY Student Information Chatbot,” 2022 5th Int. Conf. Data Storage Data Eng., pp. 108–112, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Roy, D. Singh, and S. Sahana, “Educational assistance bot,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 1797, no. 1, p. 012062, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Teckchandani, A. Santokhee, and G. Bekaroo, “AIML and Sequence-to-Sequence Models to Build Artificial Intelligence Chatbots: Insights from a Comparative Analysis,” Lect. Notes Electr. Eng., vol. 561, no. May, pp. 323–333, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Khennouche, Y. Elmir, Y. Himeur, N. Djebari, and A. Amira, “Revolutionizing generative pre-traineds: Insights and challenges in deploying ChatGPT and generative chatbots for FAQs,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 246, no. January, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Rasul et al., “The role of ChatGPT in higher education: Benefits, challenges, and future research directions,” J. Appl. Learn. Teach., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 41–56, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Doshi-Velez and B. Kim, “Towards A Rigorous Science of Interpretable Machine Learning,” no. Ml, pp. 1–13, 2017, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1702.08608.

- M. das G. Bruno Marietto et al., “Artificial Intelligence Markup Language: A Brief Tutorial,” Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. Surv., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 1–20, 2013. [CrossRef]

- “Pandorabots.” https://home.pandorabots.com/dash/help/tutorials (accessed Apr. 12, 2024).

- Jalilifard, V. F. Caridá, A. F. Mansano, R. S. Cristo, and F. P. C. da Fonseca, “Semantic Sensitive TF-IDF to Determine Word Relevance in Documents,” Lect. Notes Electr. Eng., vol. 736 LNEE, pp. 327–337, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Abbas, K. Ali, A. Jamali, K. Ali Memon, and A. Aleem Jamali, “Multinomial Naive Bayes Classification Model for Sentiment Analysis,” IJCSNS Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur., vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 62–67, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Goutte and E. Gaussier, “A Probabilistic Interpretation of Precision, Recall and F-Score, with Implication for Evaluation,” Lect. Notes Comput. Sci., vol. 3408, no. June, pp. 345–359, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Day and S. R. Shaw, “AI Customer Service System with Pre-trained Language and Response Ranking Models for University Admissions,” Proc. - 2021 IEEE 22nd Int. Conf. Inf. Reuse Integr. Data Sci. IRI 2021, pp. 395–401, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Jaiwai, K. Shiangjen, S. Rawangyot, S. Dangmanee, T. Kunsuree, and A. Sa-Nguanthong, “Automatized Educational Chatbot using Deep Neural Network,” 2021 Jt. 6th Int. Conf. Digit. Arts, Media Technol. with 4th ECTI North. Sect. Conf. Electr. Electron. Comput. Telecommun. Eng. ECTI DAMT NCON 2021, pp. 85–89, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Nguyen, M. Tran-Tien, A. P. Viet, H. T. Vu, and V. H. Nguyen, “Building a Chatbot for Supporting the Admission of Universities,” 2021 13th Int. Conf. Knowl. Syst. Eng., pp. 1–6, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Fauzia, R. B. Hadiprakoso, and Girinoto, “Implementation of Chatbot on University Website Using RASA Framework,” 2021 4th Int. Semin. Res. Inf. Technol. Intell. Syst. ISRITI 2021, pp. 373–378, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Jhqwv et al., “Intelligent Agents in Educational Institutions NEdBOT-NLP-based Chatbot for Administrative Support Using DialogFlow,” in 2022 IEEE International Conference on Agents (ICA), 2022, pp. 30–35. [CrossRef]

|

Kanaan Mikael holds a B.Sc. in Computer Science from Sulaimani University, Iraq, in 2006 and an M.Sc. in Information Technology from BAMU University, India in 2012. He is currently a Ph.D. student at Sakarya University, Turkey. With 12 years of teaching experience, Kanaan is a lecturer at the University of Human Development in Iraq. He was awarded second place in the Huawei ICT Competition 2023-2024, a Middle East-wide event held in Bahrain. His research interests encompass Natural Language Processing (NLP), Machine Translation, Machine Learning, and Dialogue systems. |

|

56. Cemil Oz was born in Cankiri, Turkey, in 1967. He received his B.S. degree in Electronics and Communication Engineering in 1989 from Yildiz Technical University and his M.S. in Electronics and Computer Education in 1993 from Marmara University, Istanbul. During the M.S. studies, he worked as a lecturer at İstanbul Technical University. In 1994, he began his Ph.D. in Electronics Engineering at Sakarya University. He completed his Ph.D. in 1998. He worked for three and half years as a research fellow at the University of Missouri-Rolla, MO, USA. He has been working as a professor in the Faculty of Computer and Information Science, Department of Computer Engineering at Sakarya University. His research interests include computer vision, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and pattern recognition. |

|

TARIK A. RASHID received a Ph.D. degree in computer science and informatics from the College of Engineering, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, University College Dublin (UCD), Ireland in 2006. He joined the University of Kurdistan Hewlêr, in 2017. He is a Principal Fellow for the Higher Education Authority (PFHEA-UK) and a professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of Kurdistan Hewlêr (UKH), Iraq. He is on the prestigious Stanford University list of the World’s Top 2% of Scientists for the years 2021, 2022, and 2023. His areas of research cover the fields of Artificial Intelligence, Nature Inspired Algorithms, Swarm Intelligence, Computational Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Data Mining. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).