1. Introduction

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly following the public deployment of Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, have influenced diverse sectors, including healthcare and education. Within educational contexts, these AI-driven technologies offer new opportunities to support learning and enhance knowledge acquisition. In healthcare, the integration of AI is expanding rapidly, encompassing applications ranging from diagnostic algorithms to clinical decision-support systems (Wartman and Combs, 2017; Banerjee et al., 2021). Given this trajectory, AI is likely to become an integral component of medical education, influencing how students interact with curricular materials and acquire core competencies. Notably, interactive AI tools such as virtual patient platforms, which present dynamic clinical scenarios with branching logic, may help scaffold the development of diagnostic reasoning and decision-making (Cook and Triola, 2009).

Although interest in AI chatbots in medical education has accelerated, much of the literature has focused primarily on tool validation and user experience, while conflating interface appeal with pedagogical effectiveness and offering less analysis grounded in theory or learning outcomes. Moreover, current research indicates that while medical students increasingly acknowledge AI’s significance, they often feel inadequately prepared to engage with it in clinical or educational contexts (Sit et al., 2020). A recent scoping review highlighted a persistent lack of empirical work evaluating the impact of AI tools on learning experience, knowledge retention, and higher-order cognitive skills (Gordon et al., 2024), thereby limiting insight into their educational value and theoretical coherence.

While students often express optimism about AI’s potential in medicine, multiple studies suggest that their understanding of its practical applications and limitations remains superficial (Bisdas et al., 2021; Amiri et al., 2024; Jebreen et al., 2024). This may, in part, reflect the lack of structured AI education within medical curricula, which has been shown to negatively affect students’ conceptual grasp and critical appraisal of AI tools (Pucchio et al., 2022; Buabbas et al., 2023). As a result, it remains difficult to assess whether AI-assisted learning offers substantive educational advantages over conventional methods. Although some studies have reported improvements in engagement and accessibility in resource-constrained settings, the extent to which AI fosters critical thinking and deeper understanding remains unclear (Jackson et al., 2024; Salih, 2024; Civanar et al., 2022; Jha et al., 2022; Luong et al., 2025).

AI chatbots, powered by LLMs, offer medical students an interactive and adaptive learning environment. In response to these limitations, educational theory offers a structured foundation for designing AI chatbots that go beyond superficial engagement to support meaningful learning. When guided by established cognitive frameworks, these tools can deliver interactive, adaptive learning environments that provide instant feedback, clarify complex concepts, and facilitate clinical problem-solving. Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) emphasises the importance of minimising extraneous processing demands to promote deep learning (Sweller, 2011). Incorporating these principles into chatbot design may help students engage with complex clinical content more effectively without becoming cognitively overloaded (Gualda-Gea et al., 2025).

In addition, this study integrates complementary conceptual frameworks to interpret user engagement and trust in AI-assisted education. Dual-Process Theory, which differentiates between intuitive (System 1) and analytical (System 2) cognition, offers a lens to assess how chatbots may facilitate rapid recall while potentially limiting reflective reasoning (Evans and Stanovich, 2013). The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) introduces a behavioural perspective, shedding light on the role of perceived usefulness and ease of use in shaping students’ adoption of educational technologies. Further, Epistemic Trust Theory provides a foundation for analysing student perceptions of the transparency, credibility, and reliability of AI-generated information (McCraw, 2015). Together, these frameworks inform both the design and analysis of this study, supporting a more rigorous assessment of chatbots not merely as digital tools, but as pedagogical instruments embedded in medical training.

The introduction of the Medical Licensing Assessment (MLA) and its linked Applied Knowledge Test (AKT) by the General Medical Council (GMC) has created a much more explicitly defined curriculum (General Medical Council, 2018). Nationally students are likely to become focused on this shared final output leading to a greater convergence of medical curricula. The current trend of medical students making use of question banks to test their knowledge will continue. These question banks will evolve to resemble the AKT-style questions. Generative AI has already been shown to be easily capable of generating appropriate questions with the proviso that expert human curation is needed for ultimate quality assurance and avoidance of hallucinations. The ultimate usefulness of a chatbot may rely on whether the style/standard of the questions matches those that are to be used in summative assessments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a randomised controlled crossover design to evaluate the educational impact of an AI chatbot (Lenny AI) compared to conventional study materials in preclinical, undergraduate medical education. Each participant completed two academic tasks, experiencing both the AI-supported and conventional learning conditions in alternating order. The study combined quantitative scores and survey measures with qualitative data from post-intervention focus group discussions, allowing for a mixed-methods analysis of both perceived and objective learning outcomes.

Our primary hypothesis from the quantitative analysis includes the following:

Participants will report significantly higher scores in the measured perception parameters when using an AI chatbot compared to conventional study tools.

The use of the AI chatbot will result in higher SBA performance scores compared to conventional tools.

Perception scores from participants using the AI chatbot correlate with performance scores.

Additionally, we aim to focus on the following research questions from our qualitative analysis:

How do medical students perceive the usefulness and usability of AI chatbots compared to conventional study tools?

What are students’ experiences with AI chatbots in supporting their learning, engagement, and information retention?

How do students perceive the limitations or challenges of using AI chatbots for medical studies?

What changes, if any, do students report in their attitudes toward AI in medical education after using the chatbot?

To what extent do students feel the chatbot aligns with their curriculum and supports deeper learning and critical thinking?

2.2. Participants and Setting

A total of 20 first-year medical students from GKT School of Medical Education, King’s College London (KCL), participated in the study. Eligible participants were enrolled in the standard five-year Medicine MBBS programme and had completed a minimum of three months of preclinical instruction. Students on the Postgraduate Entry Programme or the Extended Medical Degree Programme were excluded. Participants were recruited via posters and offered a small token of appreciation for their time, in accordance with institutional policy and ethics approval. All participants completed the full study protocol.

The study was conducted face-to-face in a classroom setting using facilities provided by KCL in 2024. To ensure standardisation, all participants accessed materials via university-provided computers or pre-prepared physical handouts.

2.3. Study Materials

2.3.1. Conventional Study Materials

For the control condition, participants used conventional learning resources, including anatomical diagrams, concise explanatory texts, and summary tables, reflecting the typical content format encountered in undergraduate anatomy teaching at KCL. Materials were derived from standardised textbook excerpts mapped to the relevant task topics:

-

1.

Ellis, H., & Mahadevan, V. (2019). Clinical Anatomy: Applied Anatomy for Students and Junior Doctors (14th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. Pages 193-200; pages 264-267.

-

2.

Moore, K. L., Dalley, A. F., & Agur, A. (2017). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (8th ed.). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Pages 1597-1599.

These materials were printed and distributed as handouts during the study session. In addition, students were permitted to use university computers to consult non-AI digital resources, such as google search or medical websites, consistent with typical self-directed study. However, all AI-based platforms (chatbots, summarisation tools, AI overviews etc.) were explicitly prohibited during the conventional learning condition.

2.3.2. AI Chatbot: Lenny AI

The intervention group used Lenny AI, a custom-designed educational chatbot developed by the qVault team, built on the ChatGPT-4o LLM created by OpenAI (OpenAI, 2024; QVault.ai, 2025). Lenny AI was created to simulate a domain-specific teaching assistant tailored to the UK undergraduate medical curriculum. It provides text-based, interactive responses to typed user queries, focusing on clinically oriented anatomy for this study. The chatbot was hosted on a secure, web-based interface and made accessible only to study participants during the experimental period.

Lenny AI is not a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) system, nor is it fine-tuned on proprietary or external data (Lewis et al., 2021). Instead, its outputs were generated directly from the base GPT-4o model, guided by robust prompt engineering and custom runtime configurations. These included a temperature setting of 0.3, an input token cap of 300, and an output limit of 1,000 tokens, all chosen to balance fluency with factual reliability and maintain a concise, high-yield interaction style. Sampling parameters were calibrated to suppress generative randomness while retaining pedagogical flexibility.

The system operated under a set of instructional guardrails that shaped output formatting and reasoning style. Prompts directed the model to employ formal medical terminology, present information in structured layouts such as tables and lists, and embed mnemonics to support cognitive retention. These constraints were designed to mimic institutional relevance without requiring dynamic integration with local lecture content. While Lenny AI was not connected to real-time databases, its response style was aligned to simulate the KCL Medicine MBBS curriculum, and all Single Best Answer (SBA) outputs were internally validated by the research team prior to deployment.

It is worth noting that, although this paper evaluates a specific tool, the implications extend beyond Lenny AI itself. Given that this implementation represents a high-performing, instruction-optimised use of a LLM, it serves as a conservative benchmark. If a custom-built, pedagogically structured chatbot demonstrates cognitive, epistemic, or performance-related limitations, then such issues are likely to be more pronounced in generic or commercially unrefined systems. At the same time, certain limitations observed in this study, particularly those related to source transparency, curriculum alignment, and reasoning depth, may potentially be mitigated through the incorporation of RAG frameworks or reasoning-optimised architectures. As such, the findings offer both a diagnosis of current constraints and a direction of travel for future chatbot development in medical education.

2.4. Study Procedures

2.4.1. Task 0: Baseline AI Perception Assessment

At the beginning of the session, participants received a brief orientation outlining the study rationale and were introduced to Lenny AI. To establish baseline familiarity and attitudes toward AI, participants completed a pre-study AI literacy and perception questionnaire. This questionnaire, comprising 20 items and administered via Google Forms (see Appendix 1), was distributed immediately prior to the academic tasks. In this context, baseline refers to participants' existing familiarity with and attitudes toward AI (as assessed in task 0), used as a reference point for comparing changes observed later in the study.

2.4.2. Task 1 and Task 2: Randomised Crossover Academic Tasks

Participants were randomly assigned a number between 001 and 020 using an online random number generator. Allocation to study arms was determined by number parity: odd-numbered participants (Arm 1) began with the AI chatbot condition, while even-numbered participants (Arm 2) began with conventional study tools.

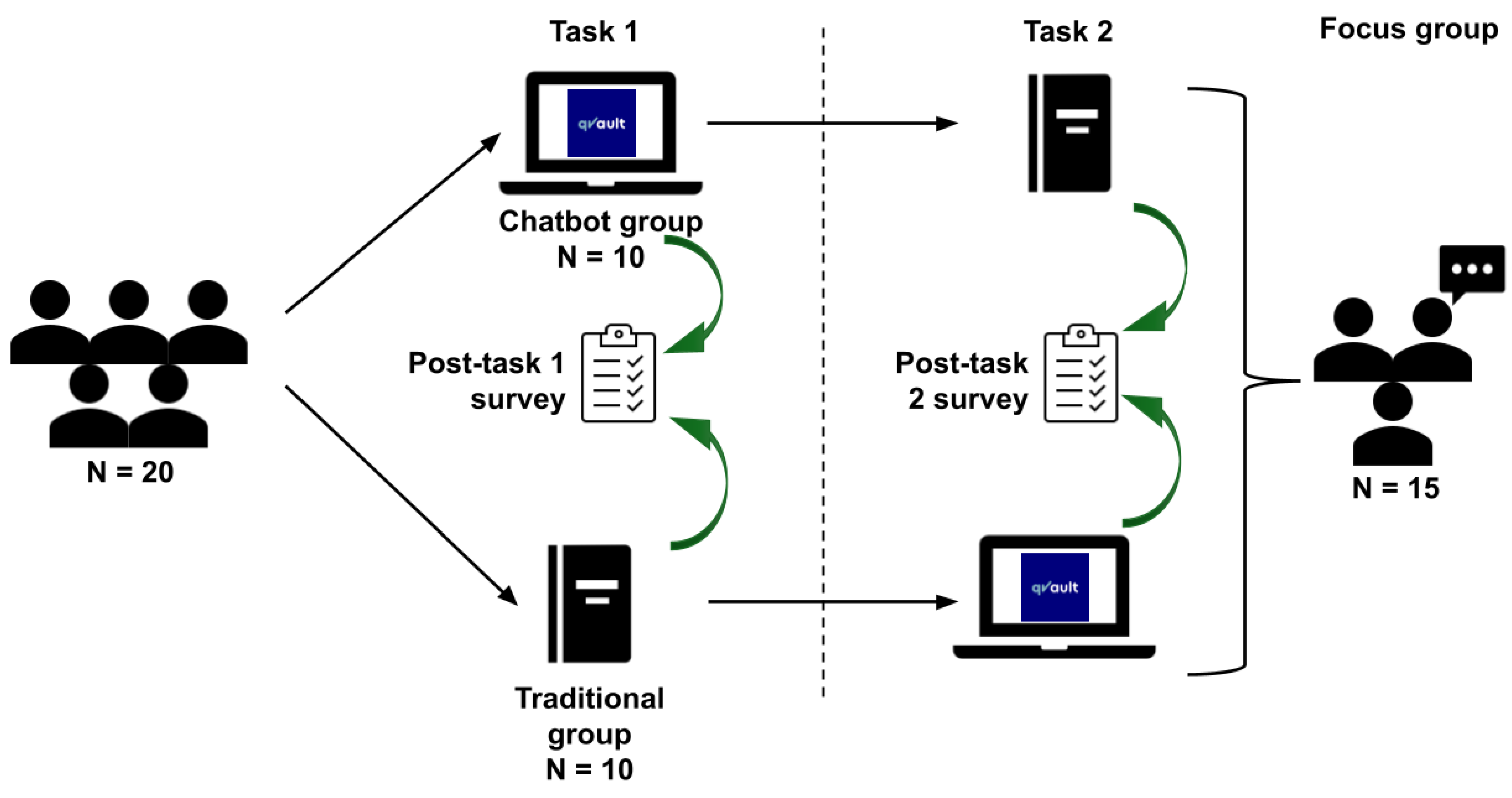

Each group completed Task 1 under their assigned condition, followed by a 10-minute break and a crossover: Arm 1 proceeded to conventional materials, while Arm 2 transitioned to the AI chatbot for Task 2. Each academic task was time-limited to 20 minutes to standardise cognitive load and reduce variability in task exposure. This randomised crossover design aimed to minimise inter-cohort variability and control for participant-level confounders (

Figure 1).

Each academic task included 10 SBA questions and 6-7 Short Answer Questions (SAQs), all mapped to the KCL Medicine MBBS curriculum. Participants were given 20 minutes per task. Task 1 focused on the anatomy and clinical application of the brachial plexus, while Task 2 addressed the lumbosacral plexus. Although both question sets were designed for preclinical students, they incorporated structured clinical vignettes to holistically assess applied anatomical knowledge and early interpretive reasoning (see Appendices 2 and 3).

2.4.3. Post-Task Questionnaire

Following each academic task, participants completed post-task questionnaires via Google Forms (see Appendices 4 and 5), assessing their perceptions of the learning method used in that task. The first and second questionnaires included 18 and 22 items, respectively, using 5-point Likert-type scales to capture agreement with statements across multiple domains of perceived learning efficacy, usability, and engagement (Likert, 1932). The second questionnaire included additional exploratory items designed to capture broader aspects of the user experience. While only a subset of these items was used in the primary analysis, the extended format allowed for more comprehensive feedback and may support secondary analyses in future work.

2.4.4. Focus Group Discussion

After completing both learning conditions, 15 of the 20 participants voluntarily joined post-task focus group discussions to further explore their experiences with the AI chatbot and conventional study materials. Three focus groups with 5 participants each were facilitated by two hosts and one transcriber over two sittings (2 groups on Day 1 and 1 group on Day 2), with each discussion lasting approximately 30 minutes.

Discussion topics were structured around nine core domains:

Experience with AI

-

3.

Changes in perceptions of AI

-

4.

Comparative effectiveness of AI tools

-

5.

Impact of AI on learning

-

6.

Usability and engagement with AI

-

7.

Challenges in using AI

-

8.

Potential future influences of AI

-

9.

Perceived role of AI in medical education

-

10.

Suggestions for improving Lenny AI

Real-time transcription was conducted by the facilitator, supplemented by contemporaneous field notes to ensure completeness. These transcripts were subsequently used for thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). (see Appendix 6)

2.5. Blinding and Data Anonymisation

Due to the interactive nature of the intervention, participants were aware of the learning method used in each task. However, all data analysis was conducted in a blinded manner. Questionnaire responses and qualitative transcripts were anonymised prior to statistical processing to reduce the potential for researcher bias.

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarised descriptively using spreadsheet formulae. To assess within-subject differences in perception between Task 1 and Task 2, the distribution of change scores was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which indicated non-normality, likely attributable to the sample size of 20 (Shapiro and Wilk, 1965). Accordingly, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare paired responses, with statistical significance defined as p-value < 0.05 (Wilcoxon, 1945). Due to the non-parametric nature of the analysis and the small sample size, a formal power calculation was not feasible. However, the crossover design improves statistical efficiency by controlling for inter-individual variability.

Performance scores were calculated as the percentage of correct responses on the 10 SBA items in each task. Four comparisons were performed:

Between-arm performance in Task 1 (Lenny AI vs. conventional tools)

-

11.

Between-arm performance in Task 2 (conventional tools vs. Lenny AI)

-

12.

Within-arm performance change in Arm 1 (Lenny AI → conventional tools)

-

13.

Within-arm performance change in Arm 2 (conventional tools → Lenny AI)

As performance scores conformed to a normal distribution (based on Shapiro–Wilk testing), these comparisons were conducted using unpaired t-tests.

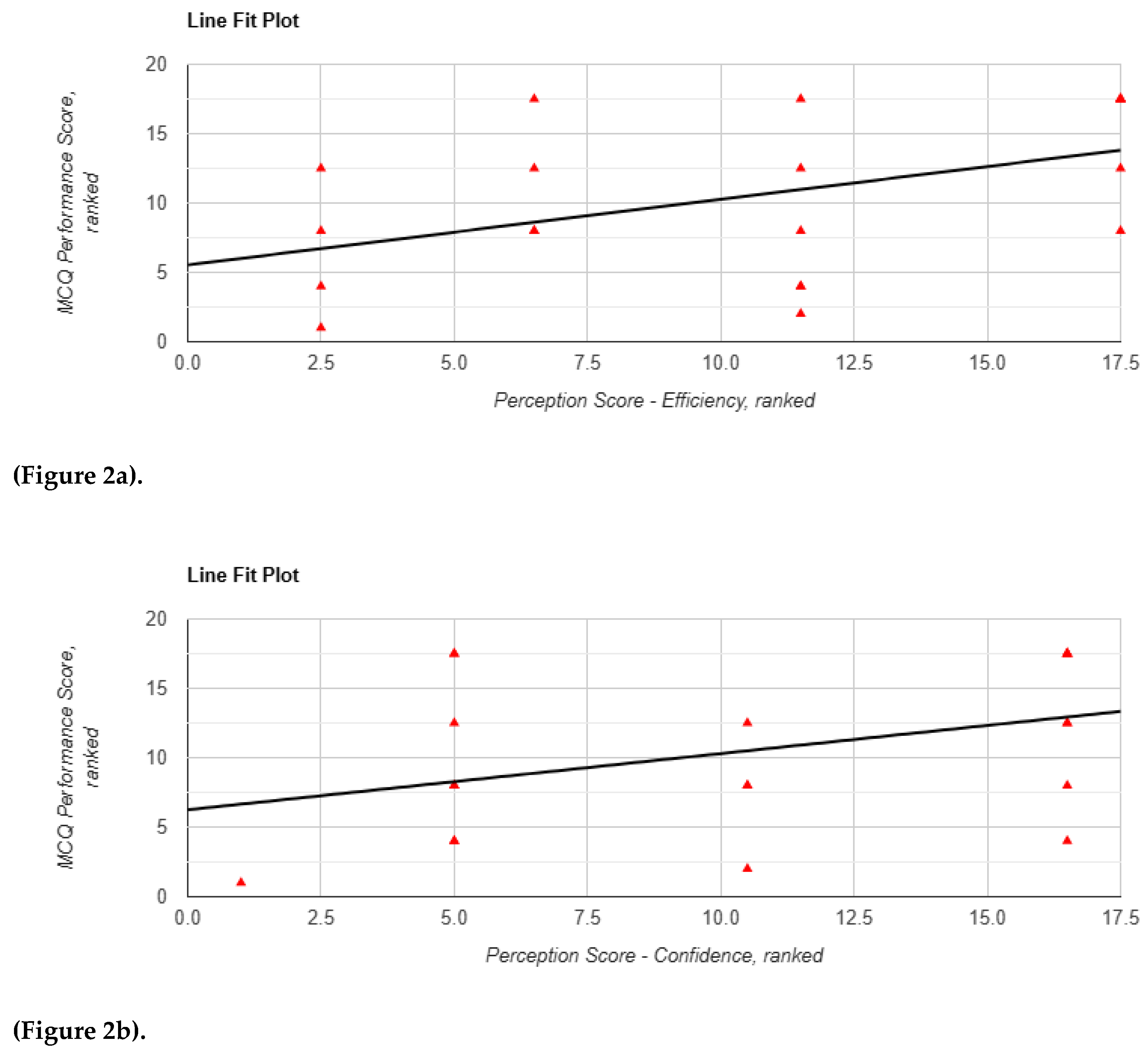

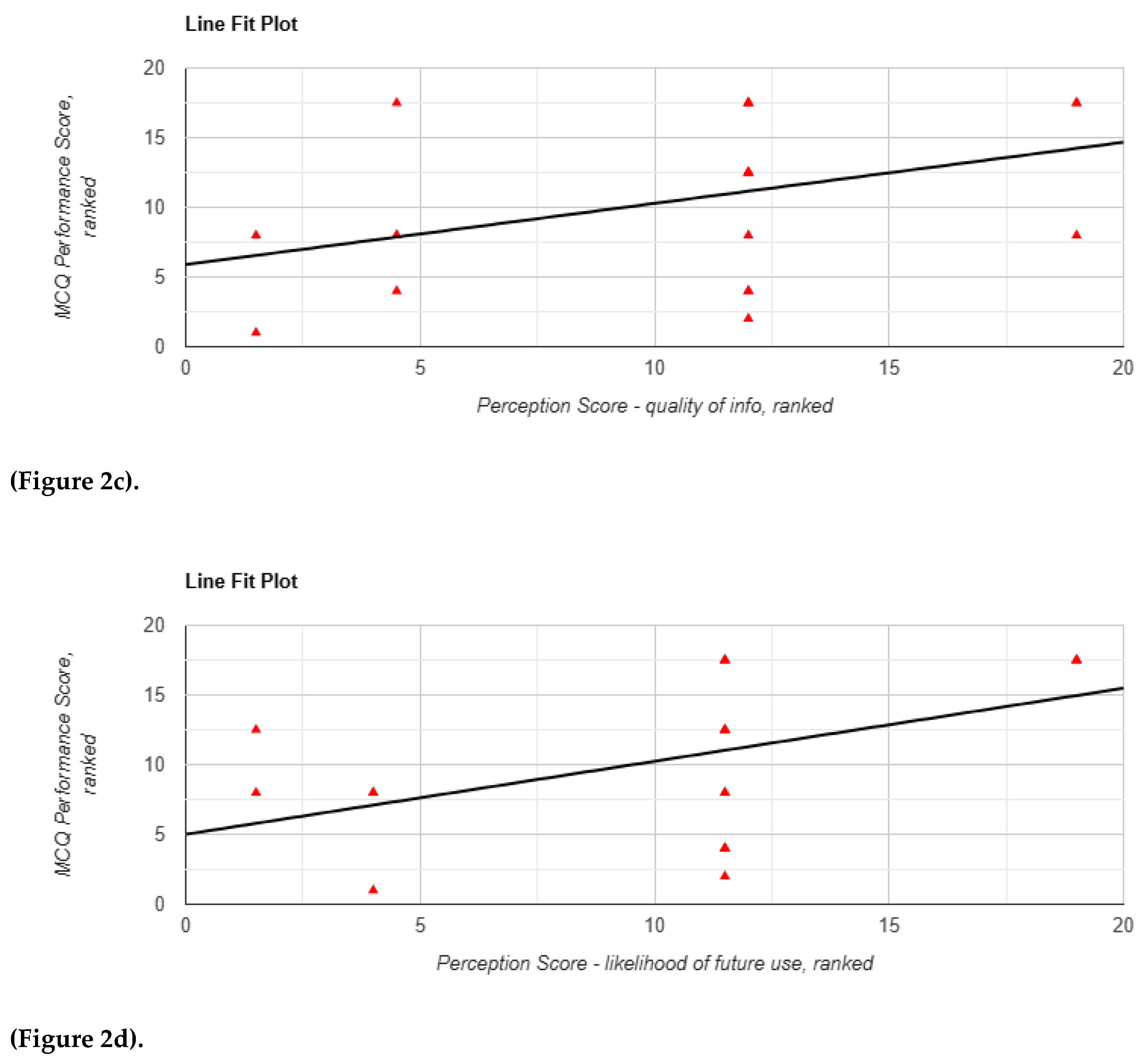

To examine the association between performance outcomes and participant perceptions, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated between the percentage scores and each of the 12 perception metrics (Spearman, 1904) (see

Table 1). Where significant associations were observed, follow-up Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare perception scores between learning conditions (Mann and Whitney, 1947). This supplementary analysis aimed to identify whether the use of the AI chatbot modified the relationship between perceived and measured learning performance.

There were no participant dropouts during the study, which was conducted over two days over two sittings. One missing response was recorded for the “ease of use” item in the baseline perception questionnaire. This data point was excluded from the analysis of that variable, with all other responses retained.

2.7. Qualitative Analysis

Focus group discussions were conducted using a semi-structured question guide designed to elicit participants' views on learning efficacy, usability, perceived credibility, and future integration of AI tools in medical education. The guide included eight core questions, each with optional follow-up prompts, covering domains such as engagement, critical thinking, and comparative perceptions of learning methods. The full question set is provided in Appendix 7.

Transcripts were then subjected to thematic analysis. Three independent coders reviewed the data using a predefined keyword framework and extracted representative quotations, which were then categorised by theme. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, calculated pairwise between each coder dyad (rater 1 vs. rater 2, rater 2 vs. rater 3, rater 1 vs. rater 3) to account for the method’s assumption of two-rater comparisons (Cohen, 1960). All analyses were conducted using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) statistical software (version 30.0.0) (IBM, 2025).

The perception questionnaire was adapted from previously validated instruments in the domains of AI education and technology acceptance (Attewell, 2024; Malmström et al., 2023), with modifications made to suit the medical education context and align with the study’s objectives.

3. Results

Among the 20 participants, 13 (65%) identified as female and 7 (35%) as male. The mean age was 19.05 years (SD = 1.47), with a range of 18 to 24 years. 16 participants (80%) reported prior experience using chatbots; 4 (20%) had no previous exposure.

3.1. Baseline Perceptions

Prior to the intervention (Task 0), participants expressed moderate confidence in their ability to use AI chatbots effectively (M = 3.05, SD = 1.00). Confidence in applying information derived from LLMs was slightly higher (M = 3.75). Perceived usefulness of AI tools was rated as highly helpful (M = 4.32, SD = 0.75), while ease of use was also positively rated (M = 3.79, SD = 0.79). However, perceived accuracy of chatbot-generated responses was more moderate (M = 3.50, SD = 0.89), indicating some initial scepticism.

Participants rated chatbots moderately in their ability to support critical thinking (M = 3.40, SD = 0.88), but more favourably in terms of saving time (M = 3.70, SD = 1.17). Concerns regarding academic integrity were low (M = 2.10, SD = 1.02). There was strong agreement that AI will play a significant role in the future of medical education (M = 4.17, SD = 0.71), and participants expressed a high likelihood of using AI chatbots in future studies (M = 4.20, SD = 0.83). Perceived importance of AI literacy was more moderate (M = 3.35, SD = 0.99).

3.2. Quantitative Findings

3.2.1. Overview

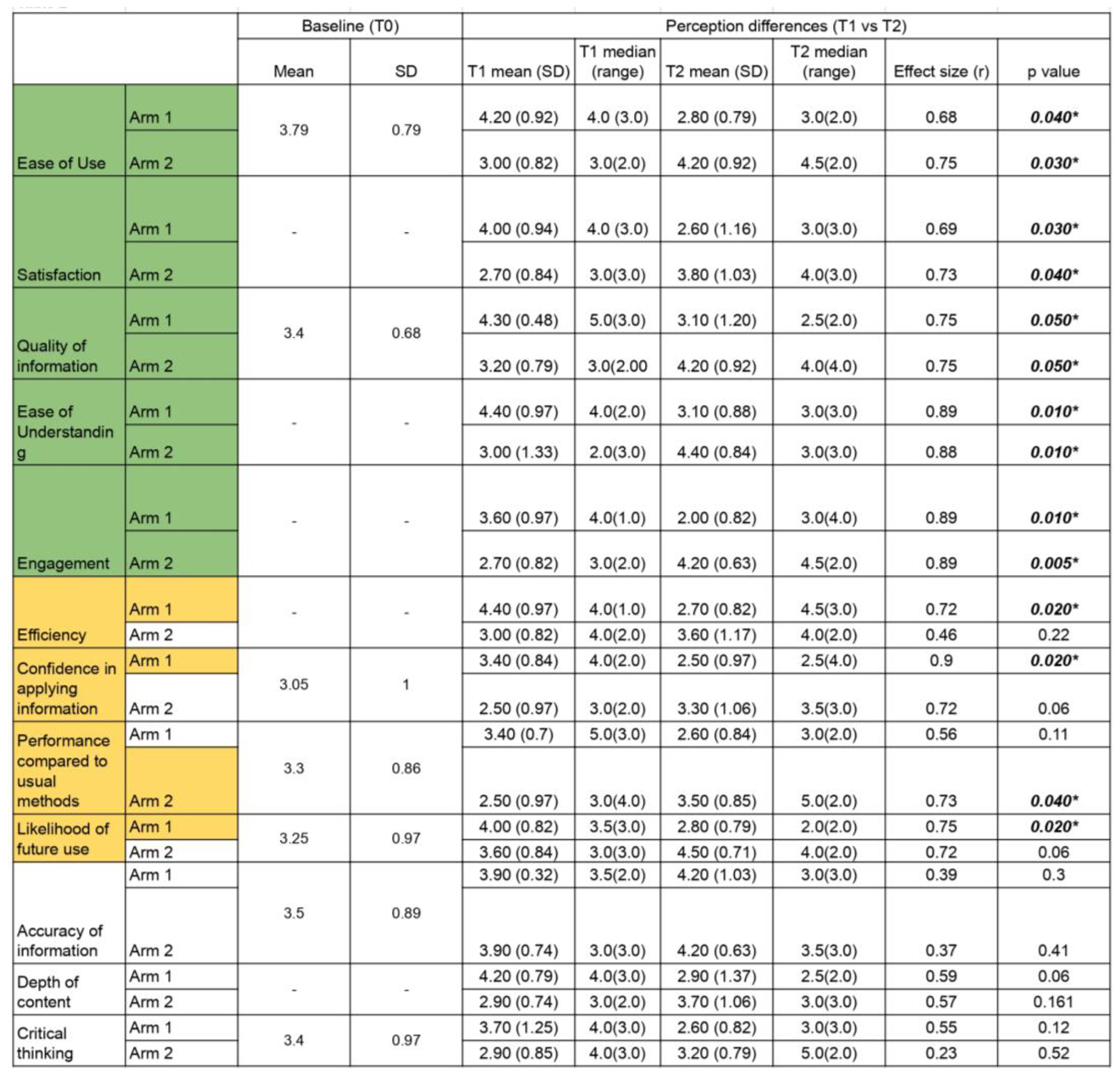

Twelve outcome domains were analysed from the post-task questionnaires based on a 5-point Likert scale: ease of use, satisfaction, efficiency, confidence in application, information quality, information accuracy, depth of content, ease of understanding, engagement, critical thinking, perceived performance compared to usual methods, and likelihood of future use. Analyses were limited to within-subject comparisons (i.e., Task 1 vs. Task 2) for each study arm independently. Results are summarised below and presented in

Table 2.

Across all twelve outcome domains, no statistically significant differences were identified in favour of conventional tools over the AI chatbot.

3.2.2. Dimensions Favouring Chatbot Use Across Both Arms

Five domains showed consistent and statistically significant preference for the AI chatbot over conventional tools across both arms: ease of use, satisfaction, ease of understanding, engagement, and perceived quality of information.

Ease of Use: Participants rated the chatbot as significantly easier to use than traditional materials (Arm 1: Mean Difference (MD) = 1.40, p = 0.040; Arm 2: MD = 1.20, p = 0.030). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance when compared with baseline expectations (Arm 1: p = 0.170; Arm 2: p = 0.510).

Satisfaction: Satisfaction scores were significantly higher in the chatbot condition (Arm 1: MD = 1.40, p = 0.030; Arm 2: MD = 1.10, p = 0.037).

Quality of Information: Both arms rated the chatbot more highly in terms of information quality (Arm 1: MD = 1.20, p = 0.050; Arm 2: MD = 1.00, p = 0.050). Notably, Arm 1 participants reported a significant improvement in their perception of information quality from baseline (3.40 to 4.30; p = 0.020)

Ease of Understanding: The chatbot condition was rated more favourably in terms of ease of understanding, where both arms reported a higher score for the question “How easy was it to understand the information provided by your given learning method?” (Arm 1 MD = 1.30; Arm 2 MD = 1.40; both p = 0.010)

Engagement: Chatbot use was associated with significantly higher engagement scores (Arm 1 MD = 1.60, p = 0.010; Arm 2 MD = 1.50, p = 0.005).

3.2.3. Divergent Perceptions of Efficiency, Confidence, Performance and Future Use

While several domains showed overall preference for the chatbot, some outcomes demonstrated statistically significant differences only within one study arm.

-

Efficiency:

- ○

Arm 1 (chatbot-first) reported significantly greater perceived efficiency (MD = 1.70, 4.40 vs. 2.70; p = 0.020) whilst completing Task 1.

- ○

Arm 2 (conventional-first) showed no significant change (MD = 0.60, 3.60 vs. 3.00; p = 0.220).

-

Confidence in Applying Information:

- ○

Arm 1: Participants felt significantly more confident applying information learned from the chatbot (MD = 0.09, 3.40 vs. 2.5; p = 0.020).

- ○

Arm 2: The increase was smaller and did not reach statistical significance (MD = 0.80, 3.30 vs 2.50; p = 0.060)

-

Perceived Performance Compared to Usual Methods:

- ○

Arm 1: The difference was not statistically significant (MD = 0.80; p = 0.110).

- ○

Arm 2: Participants reported a significant increase in perceived performance using the chatbot (MD = 1.00, 3.50 vs. 2.50; p = 0.040).

-

Likelihood of Future Use:

- ○

Arm 1: Reported a significantly greater intention to use chatbots in future learning (MD = 1.20; p = 0.020).

- ○

Arm 2: The increase approached significance (MD = 0.90; p = 0.060).

3.2.4. Inconsistent Impacts on Perceived Accuracy, Depth, and Critical Thinking

Across the remaining outcome domains, results were more variable and in some cases non-significant.

In Arm 2, there was a statistically significant increase in participants’ perceptions of the accuracy of information provided by the chatbot following Task 2, relative to Task 0 (M = 3.30 to 4.20; MD = 0.90, p = 0.046). No significant change was observed in Arm 1. This suggests a possible effect of direct engagement on perceived information reliability.

Perceptions of content depth and critical thinking did not differ significantly between learning methods in either arm. For depth of content, Arm 1 approached statistical significance (MD = 1.30, p = 0.060), while Arm 2 showed a smaller, non-significant effect (MD = 0.80, p = 0.160). Similarly, ratings for critical thinking did not yield meaningful differences (Arm 1: MD = 1.10, p = 0.120; Arm 2: MD = 0.30, p = 0.520).

3.2.5. Comparative Task Performance and Correlation with Perception

Objective performance, measured via percentage scores on Single Best Answer (SBA) questions, did not differ significantly across arms or tasks (

Table 3).

In Task 1, participants in Arm 1 (chatbot-first) achieved a mean score of 71.43% (SD = 15.06), compared to 54.29% (SD = 23.13) in Arm 2 (conventional-first), yielding a mean difference (MD) of 17.14% (95% CI: –1.20 to 35.48; p = 0.065). In Task 2, where the arms were reversed, Arm 2 (chatbot) scored 63.33% (SD = 18.92) and Arm 1 (conventional) scored 68.33% (SD = 26.59), with a non-significant MD of –5.00% (95% CI: –16.68 to 26.68; p = 0.634).

Within-arm comparisons yielded similarly non-significant findings. In Arm 1, performance decreased slightly between Task 1 and Task 2 (MD = –3.10%; 95% CI: –15.41 to 21.60; p = 0.7139). In Arm 2, performance increased from 54.29% to 63.33% (MD = 9.04%; 95% CI: –23.09 to 4.99; p = 0.179).

Although absolute performance did not vary significantly, correlation analyses revealed associations between subjective perception and performance, particularly in Task 1. Perceived efficiency was significantly correlated with performance (r(18) = 0.469, p = 0.037), and the Mann-Whitney U test showed a significant between-arm difference favouring chatbot use (p = 0.004; Z = 0.64,

Figure 2a). Confidence in applying information was also associated with a near-significant positive correlation with performance (r(18) = 0.392, p = 0.087,

Figure 2b), and was significantly higher in the chatbot group (p = 0.049; Z = 0.40).

A similar trend was observed for perceived quality of information, which was near-significantly correlated with performance (r(18) = 0.409, p = 0.073,

Figure 2c); the corresponding Mann-Whitney U test yielded a statistically significant result (p = 0.003; Z = 0.66). Likelihood of future use showed a significant correlation (r(18) = 0.475, p = 0.034,

Figure 2d), although the between-arm difference was not significant (p = 0.214; Z = 0.28).

No significant correlations were observed between performance and any perception measures in Task 2, suggesting that the strength of association may vary by exposure order or content domain.

3.3. Thematic analysis

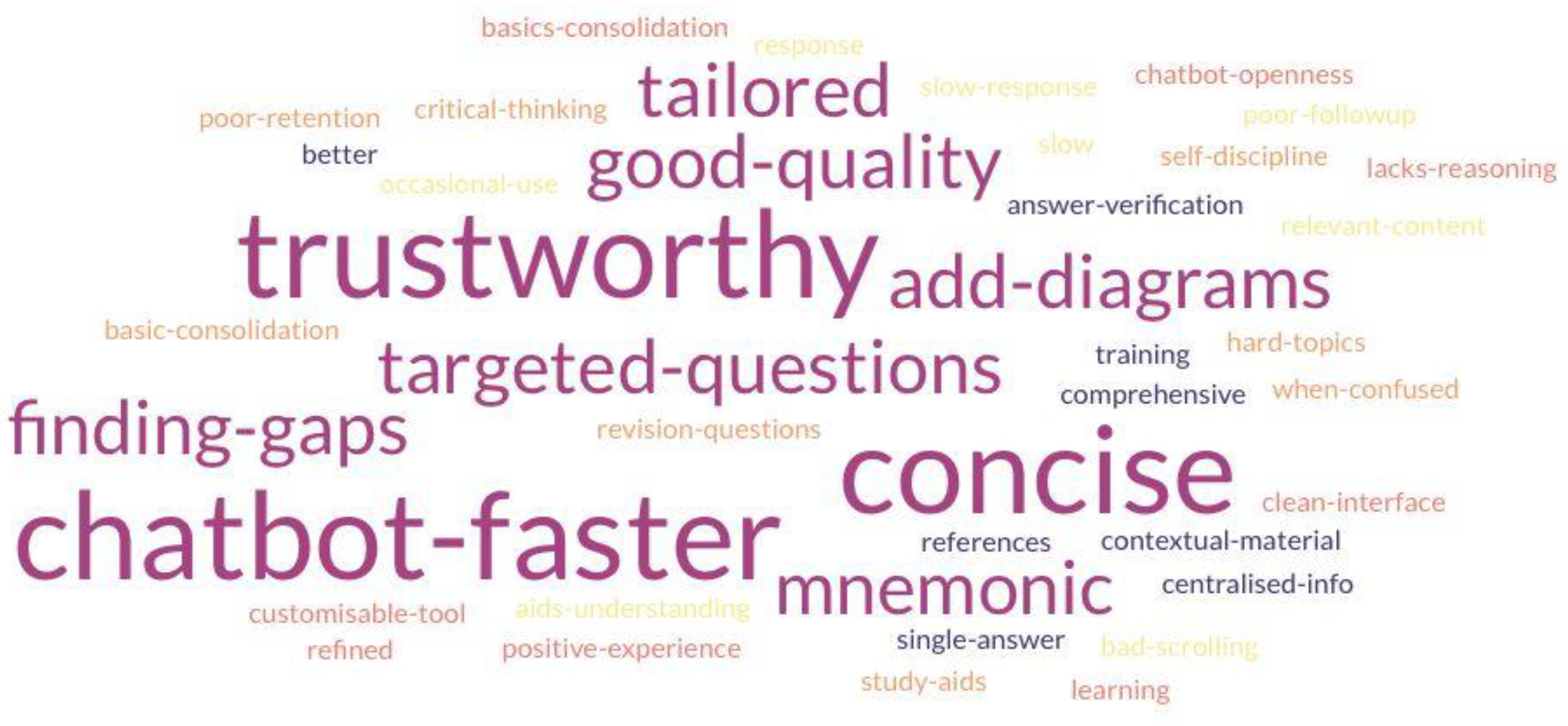

Qualitative insights were drawn from focus group transcripts, thematically analysed by three independent coders using an inductive framework. Twelve key themes were identified, reflecting both the perceived benefits and limitations of AI chatbot use in medical education (

Table 4). Inter-rater agreement ranged from fair to substantial (Cohen’s κ = 0.403–0.633), indicating acceptable reliability of thematic classification. The themes are identified and separated into two categories, and the keyphrases are represented in the word cloud (

Figure 3).

3.3.1. Speed and Efficiency

Participants consistently identified speed as a primary advantage of chatbot use. The tool was seen as particularly effective for rapid information retrieval and clarification of discrete medical queries. This conciseness was particularly beneficial when students needed quick clarification or a general topic overview. One participant noted that "if it was a single answer, then the chatbot was better" than conventional sources. Others contrasted this with conventional methods, which required "a lot longer to filter through information".

3.3.2. Depth and Complexity

While chatbots were viewed as efficient, several participants expressed concern about limitations in the depth of explanation and conceptual scaffolding. Conventional study methods were regarded as more comprehensive for building foundational understanding and exposure to broader discussions of the inquiry, with one student commenting that "traditional [conventional methods] gave residual information useful for understanding". Others felt the chatbot offered less engagement and limited support for deeper learning, with one remarking that "Googling and using notes enhanced critical thinking instead of [using] the chatbot".

3.3.3. Functional Use Case and Focused Questions

The chatbot was seen as effective for addressing specific knowledge gaps, but less suited for comprehensive topic review. Several participants reported the chatbot answering direct questions better and using it to reinforce rather than initiate learning: "Chatbot is better for specific questions" and "more useful with a specific query in mind instead of learning [an] entire topic". Concerns were also raised about knowledge retention, with one stating, "didn’t allow retaining the information" and another “Better for consolidating already learnt basic knowledge". This statement positions the chatbot less as a teacher, and more as the academic equivalent of a highlighter pen: useful, but only if you already know what’s important.”

3.3.4. Accuracy and Credibility

Perceptions of chatbot accuracy were mixed. While most participants were positively surprised by the reliability of AI-generated content (e.g. "was surprised to use a chatbot for reputable information"), some emphasised the need to corroborate responses with trusted academic sources. There were repeated suggestions to improve credibility by incorporating references: "more useful if references are included in chatbot responses" and "will trust ChatGPT more if it is trained based on past papers".

3.3.5. Openness to AI as a Learning Tool

Most participants expressed openness to using AI chatbots as supplementary learning tools. One stated, "more open to using chatbots after this [study]". However, there was widespread agreement that chatbots should not supplant textbooks or peer-reviewed material. A participant summarised this sentiment: "In its current state, I would only use it from time to time".

3.3.6. Curriculum Fit

Students frequently noted a disconnect between chatbot content and their specific medical curriculum, requiring additional effort to contextualise the information. The AI’s output was seen as generic and occasionally misaligned with institutional learning outcomes. One participant suggested: "best to train it to be tailored to [the] curriculum to ensure relevance”, hinting at further developments, such as utilising Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) techniques to ensure alignment. Another proposed that better questions could be generated if tailored to the uploaded lecture content. This suggestion reflects not only the desire for personalisation but also the implicit truth every student learns early: if it’s not on the syllabus, it might as well be wrong.

3.3.7. Further Development and Technical Limitations

Overall, the chatbot’s interface received positive feedback. One participant noted, "The UI (User Interface) is very clean and easy to use", suggesting that a smooth user experience and design played a key role in its usability. However, some participants encountered usability challenges that impacted their experience. One participant noted that "Scrolling to the bottom wasn’t smooth". Participants noted latency issues, mentioning that the chatbot takes too long to generate responses and could deter them from using the chatbot. They “tend to Google it instead if it takes too long" and "Delay could be frustrating". These limitations highlight the need for further development to improve user experience and content delivery. Suggestions for future development included the addition of diagrams, better mnemonic aids, and interactive learning tools: "generate Ankis, questions, and diagrams from PowerPoint".

4. Discussion

This study employed a mixed-methods, crossover design to examine the pedagogical value of AI chatbots in undergraduate medical education. By integrating quantitative data with qualitative insights, the findings offer a nuanced understanding of how AI tools influence learning processes. While participants consistently reported improvements in usability, efficiency, and engagement, these benefits appeared to come at the expense of cognitive depth and integrative understanding. It is important to note that participants were novice Year 1 medical students, and findings should be interpreted in light of their early stage of professional development.

4.1. The Efficiency-Depth Paradox: When Speed Compromises Comprehension

A central finding concerns what may be termed the efficiency-depth paradox. Participants found the chatbot to be significantly easier to use than conventional materials, with higher ratings for satisfaction, engagement, and perceived information quality. These improvements were supported by both statistical analysis and thematic feedback, with students praising the tool’s speed and conciseness. However, measures of content depth and critical thinking did not improve significantly, and student feedback frequently reflected concern about superficiality. As one participant noted, the chatbot was "more useful with specific queries" but lacked the capacity to "show how everything is related". Depth of content - a key measure of how well students engage with, contextualise, and interrelate information - did not exhibit meaningful improvements.

This tension may be interpreted through Cognitive Load Theory (CLT). AI chatbots appear to reduce extraneous cognitive load (the mental effort imposed by irrelevant or poorly structured information) by streamlining access to targeted information, which can be particularly beneficial in time-constrained learning environments such as medicine. However, minimising extraneous load does not automatically increase germane cognitive load, defined as the effort devoted to constructing and integrating knowledge structures (Sweller, 2011; Gualda-Gea et al., 2025). In our study, although participants reported lower mental effort, this did not translate into deeper learning outcomes, suggesting limited activation of the cognitive processes needed for long-term retention and schema development. That said, for learners with less developed metacognitive strategies, such as difficulty with content triage, synthesis, or task regulation, the chatbot may function as a cognitive scaffold. By mitigating surface-level overload, it enables more efficient resource allocation toward germane cognitive processes than would typically be achievable with conventional, unstructured materials. In such cases, the chatbot does not merely streamline information retrieval but actively supports a more stable cognitive load distribution, thereby facilitating more sustained engagement. Although this interpretation warrants empirical validation, it offers a theoretically grounded explanation for the heterogeneous patterns observed across both performance outcomes and user perceptions. Longitudinal studies tracking learners’ cognitive development over time would provide more definitive insights into how AI tools influence schema construction and knowledge integration.

The Dual-Process Theory offers further explanatory insight. The chatbot interface predominantly supported System 1 cognition — fast, intuitive, and suitable for factual recall. Yet deeper conceptual learning in medicine depends on System 2 cognition — deliberate, reflective, and analytical. The lack of improvement in critical thinking domains and depth of content suggests an imbalance in cognitive processing. Participant feedback reinforced this distinction; while the chatbot facilitated quick answers, it failed to prompt reflective engagement and often felt transactional or superficial, thereby reinforcing a reliance on rapid, surface-level cognition at the expense of deeper conceptual integration. In other words, chatbots appeared to fast-track learners down a highway, occasionally bypassing the scenic route of reflective reasoning.

These findings have important implications for instructional design. AI chatbots, if unmodified, may reinforce surface learning strategies at the expense of higher-order thinking. To mitigate this, chatbot design should incorporate adaptive scaffolding. For instance, requiring learners to articulate reasoning or engage in structured reflection before receiving answers. Such strategies may encourage transitions from intuitive to analytical processing, aligning the tool more closely with deep learning objectives. However, excessive scaffolding risks undermining learner autonomy; future designs should consider offering scaffolded support as optional and allow tailoring learning pathways according to individual needs.

Finally, these limitations also articulate the importance of pedagogical complementarity. AI tools should augment, not replace, methods that foster dialogue, exploration, and self-reflection. For example, chatbots may be well suited to supporting flipped classroom models or hybrid learning strategies, in which they serve as preliminary tools for foundational knowledge acquisition, followed by an in-person, case-based discussion to promote deeper conceptual engagement and mitigate the trade-off.

4.2. Confidence Versus Competence: The Illusion of Mastery

This study revealed a notable dissociation between students’ self-reported confidence and their demonstrated cognitive performance. Participants exposed to the AI chatbot reported significantly greater confidence in applying information, alongside improved perceptions of information accuracy. However, these perceptions were not accompanied by measurable improvements in critical thinking or consistent gains in academic performance. In some instances, performance declined relative to conventional methods. Despite this disconnect, participants expressed a strong intention to continue using the chatbot. This suggests high user endorsement, yet also increases the risk of overestimating one’s mastery based on the immediacy and clarity of AI responses.

Qualitative feedback reinforced this discrepancy. Many students viewed the chatbot as a confidence-boosting tool, frequently citing its clarity, speed, and directness. Several commented that its concise and unambiguous format made information feel more accessible than conventional materials, reducing uncertainty when studying. However, others voiced concern that this simplification limited deeper engagement, describing the chatbot as helpful for rapid fact-checking but insufficient for promoting reflective or analytical thinking.

These findings are consistent with the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which posits that perceived ease of use and usefulness are key predictors of user acceptance (Davis, 1989). Our data support this mechanism: students clearly valued the chatbot’s functionality. However, TAM does not assume that usability translates into deep cognitive engagement. The chatbot’s structured, efficient interface may foster recall and fluency, but lacks the scaffolding required for critical thinking and complex reasoning. This distinction matters: the fluency of retrieval may be misinterpreted as comprehension, resulting in cognitive overconfidence, in which learners feel assured without having achieved conceptual mastery.

The educational implications are significant. While confidence enhances engagement and can motivate further learning, confidence without competence poses risks, particularly in clinical education, where overconfidence may translate into diagnostic error. AI-based learning tools should therefore be designed to temper misplaced certainty and mitigate overconfidence, ensuring that learners interrogate their understanding rather than accept fluency as a proxy for insight.

One potential solution lies in instructional scaffolding embedded within chatbot interactions. For example, prompting students to articulate their reasoning before receiving answers may compel engagement with the underlying logic, fostering deeper processing. Similarly, adaptive AI systems could modulate task complexity based on expressed confidence, offering progressively challenging scenarios that test conceptual boundaries and guard against premature certainty. Future mediation analyses may examine whether increases in self-reported confidence predict actual academic performance or if these effects reflect transient affective boosts without corresponding cognitive development.

4.3. Transparency and Traceability: The Foundations of Trust in AI Learning Tools

The perceived credibility of AI-driven learning tools hinges not only on the accuracy of their outputs, but also on the transparency of their informational provenance. In our study, students reported significantly improved perceptions of the chatbot’s quality and accuracy over time, reflecting confidence in its technical performance. Yet qualitative data revealed persistent concerns regarding the verifiability of responses and the absence of identifiable sources. This tension reflects a broader challenge in AI integration: how to foster epistemic trust in systems that deliver answers without evidentiary scaffolding.

Although the chatbot reliably produced correct and relevant responses, many students hesitated to fully trust its outputs due to a lack of traceable citations or curricular alignment. Several explicitly requested embedded references and clearer links to validated educational materials. Its persona occasionally resembled an overenthusiastic peer: helpful, articulate, and entirely unreferenced. These findings echo current debates in algorithmic transparency, which emphasise that accuracy is insufficient without contextual legibility; that is, the ability of users to interrogate the epistemic basis of machine-generated outputs. In high-stakes educational settings such as medicine, where knowledge validity is paramount, tools that obscure their informational lineage risk undermining their own utility.

TAM offers partial explanatory power here. While perceived ease of use and usefulness clearly facilitated chatbot adoption, long-term engagement requires a deeper sense of control and visibility over system logic. Without transparency, students may rely on the chatbot for efficiency, but withhold full epistemic endorsement. In other words, accepting its outputs functionally, yet distrusting them academically.

This distinction is captured more precisely by epistemic trust theory, which holds that credibility depends on the perceived expertise, integrity, and openness of an information source (Origgi, 2004; McMyler, 2011). In our findings, the chatbot met functional expectations of accuracy but fell short of epistemic credibility. Participants repeatedly described a desire for tools that did not merely appear accurate, but enabled verification. Without mechanisms for students to trace, interrogate, and contextualise content, trust remained provisional.

Addressing this credibility dilemma requires a dual-pronged approach. First, chatbots must maintain their efficiency and streamlined design, ensuring that it remains a highly accessible learning tool. Concurrently, it must incorporate mechanisms for transparency, allowing users to verify, interrogate, and expand upon the information provided. To reconcile these demands, the following design features are recommended:

Citation Toggles: Allowing users to reveal underlying references where applicable, supporting source traceability.

Uncertainty Indicators: Signalling lower-confidence outputs to prompt additional verification.

Expandable Explanations: Offering tiered content depth, enabling students to shift from summary to substantiated detail on demand.

In the absence of these deeper structural redesigns, students are likely to remain selectively engaged with AI tools: turning to them for convenience, but withholding full epistemic reliance. It is worth noting, however, that superficial interface enhancements, such as citation toggles or confidence indicators, may elevate the appearance of trustworthiness but do little to guarantee its substance. This distinction is not merely semantic; it is pedagogically fundamental. An interface that feels authoritative cannot compensate for outputs that remain unverifiable. The prioritisation of aesthetic fluency over evidentiary integrity in many AI-driven learning platforms may cultivate a form of functional trust that lacks epistemic depth, potentially leading to commercial success. Yet, in such cases, user experience becomes a surrogate for validation, offering a veneer of credibility while displacing the critical standards upon which educational authority must rest. Moreover, developing scalable, transparent trust mechanisms that meet both educational and epistemic standards remains a substantial design challenge that future AI systems must actively confront.

Ultimately, trust in AI-assisted learning is not a function of fluency alone, but is built through transparency, traceability, and critical agency. Students must be empowered not only to accept chatbot-generated content, but to interrogate it, contextualise it, and, where appropriate, challenge it. Without this shift, AI risks reinforcing passive consumption rather than fostering the critical appraisal skills essential to clinical practice.

4.4. No Consistent Performance Gains from Chatbot Use

Although chatbot use did not produce statistically significant improvements in performance across all 20 participants, the absence of significance is the most striking finding in this field saturated with hype. It challenges the core assumption that AI-enhanced tools inherently improve learning outcomes and the overlooked importance of context, content, and learner variability in shaping efficacy. In Task 1, students using the chatbot outperformed their peers using conventional resources, and perceptions of efficiency, confidence, and information quality showed positive associations with performance. However, these effects were not observed in Task 2, and no consistent pattern emerged across arms or tasks. Despite the lack of statistical significance, relative performance increases ranging from 5% to 17% suggest potential practical significance, particularly in our time-constrained settings, a hypothesis that merits further exploration through larger, adequately powered studies. The use of engagement and learning analytics could provide objective measures of cognitive load and learning retention over time.

More importantly, this inconsistency suggests the need to move beyond the assumption of uniform benefit. Qualitative feedback reinforces this: students described the chatbot as most effective for discrete, fact-based tasks, while expressing limitations in areas requiring conceptual synthesis. These findings suggest that the chatbot may favour learners who are already confident, goal-oriented, and proficient in self-directed learning, while offering less benefit to those who depend on scaffolding and structured reasoning to build understanding.

These observations call into question the adequacy of performance as a monolithic metric. Rather than relying solely on mean task scores, future studies should adopt more granular analytic approaches, such as mastery threshold models (e.g. via the Angoff method), residual gain analysis, or subgroup stratification based on learner confidence or cognitive style (Angoff, 1971). Where mastery thresholds are employed, triangulation with inter-rater reliability measures such as Cohen’s kappa would further strengthen methodological validity, particularly in larger cohorts (McHugh, 2012). Our findings indicate that AI tools may not equalise performance, but rather stratify it, reinforcing existing learner differences unless specifically designed to account for them.

Crucially, the absence of consistent performance gains should not be read as a failure of the chatbot per se, but as a call to rethink how such tools are designed and evaluated. Static delivery of content, regardless of how streamlined or accurate, is unlikely to yield uniform gains across diverse learner populations. AI tools must become more adaptive, sensitive to learner signals, task complexity, and evolving knowledge states. Incorporating diagnostic mechanisms that adjust the depth, format, or difficulty of chatbot responses based on real-time indicators of comprehension could help bridge the gap between surface-level usability and meaningful educational value.

5. Limitations

While this study offers valuable preliminary insights into AI chatbot use in medical education, several methodical considerations must be addressed in future work.

First, the modest sample size limits statistical power and increases susceptibility to Type I error. While several outcomes reached conventional significance thresholds, future studies would benefit from larger samples and longer washout periods to improve internal validity and minimise potential carryover effects. In addition, applying correction procedures such as Bonferroni or false discovery rate adjustment can further safeguard against spurious findings and ensure that reported effects reflect robust patterns, particularly those relating to confidence, engagement, and accuracy (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995; Bonferroni, 1936).

Second, while SBA questions offer an efficient and standardised method for assessing factual knowledge, they predominantly target the lower levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy, namely, remembering and understanding (Bloom, 1956). Though well-crafted SBAs can sometimes reach higher-order cognitive skills such as application and analysis, they often fall short of fully capturing the complex clinical reasoning required in medical practice. To enhance ecological validity, future evaluations should incorporate performance-based assessments, such as a deep evaluation of SAQs, Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) or AI-integrated case simulations, which better reflect real-world diagnostic and decision-making demands (Messick 1995, Van Der Vleuten 2005).

Finally, the generalisability of AI chatbot outputs remains constrained by the scope of their training data. If models are predominantly trained on Western biomedical literature and curricula, they may fail to accommodate context-specific variations in clinical practice, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Whitehorn, 2021). This raises concerns regarding content validity, biases and the equitable applicability of AI tools across diverse educational systems. Future studies should explicitly assess the performance of chatbots in non-Western curricular contexts, especially those that prioritise competency-based learning and locally relevant clinical paradigms. In addition, a design-based research (DBR) approach may offer methodological advantages by enabling iterative refinement of chatbot features across real-world educational settings, thereby enhancing both practical relevance and theoretical insight (Brown, 1992).

6. Conclusion

This study offers early but compelling evidence that AI chatbots can augment medical education by enhancing efficiency, engagement, and rapid information access. Yet these gains come with trade-offs. The limitations observed in fostering critical thinking, conceptual depth, and long-term retention reveal that chatbot use, while promising, is not pedagogically sufficient in isolation. Our findings advocate for a reframing of AI not as a standalone tutor, but as a pedagogical partner. It should be best deployed within hybrid educational models that preserve the rigour of clinical training while leveraging the speed and accessibility of intelligent systems. The crossover design employed in this feasibility study serves as an early validation of student acceptance, building a robust foundation for larger-scale and longer-term evaluations.

If AI is to earn its place in the future of medical education, it must not only deliver correct answers but also cultivate reasoning, reflection, and relevance. This is the line that separates educational technology from educational value, and scalable access from scalable wisdom.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Isaac Ng and Mandeep Gill Sagoo; Data curation, Isaac Ng, Anthony Siu, Claire Han, Oscar Ho and Jonathan Sun; Formal analysis, Isaac Ng, Anthony Siu, Claire Han, Oscar Ho and Jonathan Sun; Funding acquisition, Isaac Ng; Methodology, Isaac Ng and Mandeep Gill Sagoo; Project administration, Isaac Ng and Anthony Siu; Supervision, Anatoliy Markiv, Stuart Knight and Mandeep Gill Sagoo; Validation, Anthony Siu; Visualization, Isaac Ng, Anthony Siu, Claire Han and Jonathan Sun; Writing – original draft, Isaac Ng, Anthony Siu, Claire Han, Oscar Ho and Jonathan Sun; Writing – review & editing, Isaac Ng and Anthony Siu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the College Teaching Fund at King’s College London. The funders had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, or reporting of the study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received ethical approval from the KCL Research Ethics Management Application System (REMAS) (Ref: LRS/DP-23/24-40754). Approved on 18/11/2024. All study procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and complied with relevant data governance policies, including the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (European Union, 2016). Interaction data generated during the study were stored securely on institutional servers. No personally identifiable information was shared with third-party providers, including OpenAI, and no data was retained externally in accordance with the provider’s data handling policy.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the qVault team for their key role in developing and maintaining Lenny AI, the educational chatbot used in this study. Lenny AI is part of qVault.ai, an AI-powered education platform created through a student–staff partnership at KCL. The platform integrates AI engineering with pedagogical research to provide curriculum-aligned tools for medical education, including question generators, case creators, study assistants, and OSCE examiners. The team also provided ongoing technical support throughout the project. We acknowledge the wider team involved in building and refining the qVault platform (with names listed in alphabetical order): Abirami Muthukumar, Ananyaa Gupta, Natalie Wai Ka Leung, Nicolas Hau, Rojus Censonis, Sophia Wooden, Syed Nafsan, Victor Wang Tat Lau, and Yassin Ali.

Conflicts of Interest

Isaac Sung Him Ng, Claire Soo Jeong Han, Oscar Sing Him Ho, and Mandeep Gill Sagoo were involved in the development of Lenny AI, the AI chatbot evaluated in this study, as part of an educational research and development initiative. While Lenny AI served as the implementation tool, the study was designed to explore broader pedagogical themes related to AI-assisted learning, not to promote any specific product. At the time of study conduct, there was no commercial revenue associated with Lenny AI, and no participants or researchers received financial incentives linked to the tool. All data collection, analysis, and interpretation were carried out independently, and the authors adhered to institutional ethical guidelines to mitigate bias. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbrev. |

Full form |

| AKT |

Applied Knowledge Test |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| CLT |

Cognitive Load Theory |

| DBR |

Design-Based Research |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| KCL |

King’s College London |

| LLM(s) |

Large Language Model(s) |

| LMIC(s) |

Low- and Middle-Income Country(ies) |

| M |

Mean |

| MD |

Mean Difference |

| n |

Sample size |

| OSCE(s) |

Objective Structured Clinical Examination(s) |

| p |

p-value |

| RAG |

Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| r |

Correlation coefficient (effect size) |

| REMAS |

Research Ethics Management Application System |

| SAQ(s) |

Short Answer Question(s) |

| SBA |

Single Best Answer |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TAM |

Technology Acceptance Model |

| T0, T1, T2 |

Task 0 (baseline), Task 1, Task 2 timepoints |

| UI |

User Interface |

| Z |

Z-statistic |

| κ (kappa) |

Cohen’s kappa coefficient |

References

- Amiri, H. et al. (2024) ‘Medical, dental, and nursing students’ attitudes and knowledge towards artificial intelligence: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, BMC Medical Education [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Angoff, W.H., 1971. Educational measurement. Washington: American Council on Education.

- Attewell, S. (2024) ‘Student perceptions of generative AI report’, JISC [Preprint].

- Banerjee, M. et al. (2021) ‘The impact of artificial intelligence on clinical education: perceptions of postgraduate trainee doctors in London (UK) and recommendations for trainers’, BMC Medical Education [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. (1995) ‘Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 1 pp. 289–300. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2346101 (Accessed: 30 April 2025).

- Bisdas, S. et al. (2021) ‘Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: A Multinational Multi-Center Survey on the Medical and Dental Students’ Perception’, Frontiers in Public Health [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain. New York: Longman.

- Bonferroni, C. (1936). Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilità. Pubblicazioni del R Istituto Superiore di Scienze Economiche e Commerciali di Firenze.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), pp. 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. L. (1992) ‘Design Experiments: Theoretical and Methodological Challenges in Creating Complex Interventions in Classroom Settings’, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2(2), pp. 141–178. [CrossRef]

- Buabbas, A. et al. (2023) ‘Investigating Students’ Perceptions towards Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education’, Healthcare [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Civaner, M.M. et al. (2022) ‘Artificial intelligence in medical education: a cross-sectional needs assessment’, BMC Medical Education [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1960). A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), pp.37–46. [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.A. and Triola, M.M. (2009). Virtual patients: a critical literature review and proposed next steps. Medical Education, 43(4), pp.303–311. [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319-340.

- European Union (2016). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). [online] General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/.

- Evans JS, Stanovich KE. Dual-Process Theories of Higher Cognition: Advancing the Debate. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013 May;8(3):223-41. [online]. [CrossRef]

- General Medical Council (2018). Medical Licensing Assessment. [online] Gmc-uk.org. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/medical-licensing-assessment.

- Gordon, M. et al. (2024) ‘A scoping review of artificial intelligence in medical education: BEME Guide No. 84’, Medical Teacher [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Gualda-Gea, J.J. et al. (2025) ‘Perceptions and future perspectives of medical students on the use of artificial intelligence based chatbots: an exploratory analysis’, Frontiers in Medicine [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P. et al. (2024) ‘Artificial intelligence in medical education - perception among medical students’, BMC Medical Education [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- IBM (2025). SPSS software. [online] IBM. https://www.ibm.com/spss.

- Jebreen, K. et al. (2024) ‘Perceptions of undergraduate medical students on artificial intelligence in medicine: mixed-methods survey study from Palestine’, BMC Medical Education [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Jha, N. et al. (2022) ‘Undergraduate Medical Students’ and Interns’ Knowledge and Perception of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine’, Advances in medical education and practice [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P., Perez, E., Piktus, A., Petroni, F., Karpukhin, V., Goyal, N., Küttler, H., Lewis, M., Yih, W., Rocktäschel, T., Riedel, S. and Kiela, D. (2021). Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. [online] arXiv.org. [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), p. 55.

- Luong, J. et al. (2025) ‘Exploring Artificial Intelligence Readiness in Medical Students: Analysis of a Global Survey.’ . [CrossRef]

- Malmström, H., Stöhr, C. and Ou, W. (2023) ‘Chatbots and other AI for learning: A survey of use and views among university students in Sweden’. [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. and Whitney, D.R. (1947). On a Test of Whether one of Two Random Variables is Stochastically Larger than the Other. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, [online] 18(1), pp.50–60. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. (2009) Multimedia learning, 2nd ed. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press (Multimedia learning, 2nd ed), pp. xiii, 304. [CrossRef]

- McCraw, B. W. (2015). The Nature of Epistemic Trust. Social Epistemology, 29(4), 413–430. [online] . [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L., 2012. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), pp.276–282.

- Mcmyler, B. (2011). Testimony, trust, and authority. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Messick, S. (1995) ‘Standards of Validity and the Validity of Standards in Performance Asessment’, Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 14(4), pp. 5–8. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI (2024). Hello GPT-4o. [online] Openai.com. https://openai.com/index/hello-gpt-4o/.

- Origgi, G. (2004) ‘Is Trust an Epistemological Notion?’, Episteme, 1(1), pp. 61–72. [CrossRef]

- Pucchio, A. et al. (2022) ‘Exploration of exposure to artificial intelligence in undergraduate medical education: a Canadian cross-sectional mixed-methods study’, BMC Medical Education [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Qvault.ai. (2025). qVault. [online] https://qvault.ai [Accessed 30 Apr. 2025].

- Salih, S.M. (2024) ‘Perceptions of Faculty and Students About Use of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: A Qualitative Study’, Cureus [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S. and Wilk, M.B. (1965). An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika, 52(3-4), pp.591–611. [CrossRef]

- Sit, C. et al. (2020) ‘Attitudes and perceptions of UK medical students towards artificial intelligence and radiology: a multicentre survey’, Insights into Imaging [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. (1904). The Proof and Measurement of Association between Two Things. The American Journal of Psychology, 15(1), pp.72–101. [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (2011) ‘CHAPTER TWO - Cognitive Load Theory’, in J.P. Mestre and B.H. Ross (eds) Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Academic Press, pp. 37–76. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vleuten, C.P.M. and Schuwirth, L.W.T. (2005) ‘Assessing professional competence: from methods to programmes’, Medical Education, 39(3), pp. 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Wartman, S. and Combs, C. (2017) ‘Medical Education Must Move From the Information Age to the Age of Artificial Intelligence’, Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Whitehorn, A. et al. (2021) ‘Mapping Clinical Barriers and Evidence-Based Implementation Strategies in Low-to-Middle Income Countries (LMICs)’, Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 18(3), pp. 190–200. [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. (1945). Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biometrics Bulletin, 1(6), pp.80–83. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic of the randomised crossover study design. All 20 participants completed two academic tasks, each including 10 Single Best Answer (SBA) and 6–7 Short Answer Questions (SAQs). The duration of each task is 20 minutes, with 10 minutes in between. In Task 1, Arm 1 (n = 10) used the AI chatbot (qVault), while Arm 2 (n = 10) used traditional/conventional learning resources comprising printed textbook materials and unrestricted web browsing, excluding AI-based tools. In Task 2, the arms crossed over. SAQs were unscored but designed to promote deeper engagement. Post-task surveys followed each task. Fifteen participants voluntarily participated in an optional focus group discussion after both tasks were completed.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the randomised crossover study design. All 20 participants completed two academic tasks, each including 10 Single Best Answer (SBA) and 6–7 Short Answer Questions (SAQs). The duration of each task is 20 minutes, with 10 minutes in between. In Task 1, Arm 1 (n = 10) used the AI chatbot (qVault), while Arm 2 (n = 10) used traditional/conventional learning resources comprising printed textbook materials and unrestricted web browsing, excluding AI-based tools. In Task 2, the arms crossed over. SAQs were unscored but designed to promote deeper engagement. Post-task surveys followed each task. Fifteen participants voluntarily participated in an optional focus group discussion after both tasks were completed.

Figure 2.

a–d. Correlation between perception parameters and SBA performance scores for Task 1 using Lenny AI. Each red triangle represents a participant’s ranking: perception score (X-axis) and performance score (Y-axis) among 20 participants. Tied scores were assigned the same rank. Panels: (A) Efficiency, (B) Confidence in applying information, (C) Perceived quality of information, (D) Likelihood of future use.

Figure 2.

a–d. Correlation between perception parameters and SBA performance scores for Task 1 using Lenny AI. Each red triangle represents a participant’s ranking: perception score (X-axis) and performance score (Y-axis) among 20 participants. Tied scores were assigned the same rank. Panels: (A) Efficiency, (B) Confidence in applying information, (C) Perceived quality of information, (D) Likelihood of future use.

Figure 3.

Word cloud of phrases cited by participants during focus group discussions. The size of each phrase reflects the frequency with which it was mentioned across all participants. Key perceived strengths of the chatbot included its trustworthiness, speed, and conciseness. The most frequently suggested area for improvement was the integration of visual aids, particularly the ability to generate diagrams as part of the chatbot’s functionality.

Figure 3.

Word cloud of phrases cited by participants during focus group discussions. The size of each phrase reflects the frequency with which it was mentioned across all participants. Key perceived strengths of the chatbot included its trustworthiness, speed, and conciseness. The most frequently suggested area for improvement was the integration of visual aids, particularly the ability to generate diagrams as part of the chatbot’s functionality.

Table 1.

Outcome measures and corresponding survey questions. This table lists the outcome measures assessed through post-task questionnaires, alongside the exact survey questions used to evaluate each domain. Outcome measures targeted key aspects of user experience, including usability, satisfaction, information quality, engagement, and perceived performance. Responses were collected after participants completed each task, providing the basis for the perception analyses presented in this study.

Table 1.

Outcome measures and corresponding survey questions. This table lists the outcome measures assessed through post-task questionnaires, alongside the exact survey questions used to evaluate each domain. Outcome measures targeted key aspects of user experience, including usability, satisfaction, information quality, engagement, and perceived performance. Responses were collected after participants completed each task, providing the basis for the perception analyses presented in this study.

| Outcome Measures |

Questions |

| Ease of Use |

"How easy was it to use this learning method?" |

| Satisfaction |

"Overall, how satisfied are you with this method for studying?" |

| Efficiency |

"How efficient was this method in gathering info?" |

| Confidence in Applying Information |

"How confident do you feel in applying the information learned?" |

| Quality of Information |

"Rate the quality of the information provided." |

| Accuracy of Information |

"Was the information provided accurate?" |

| Depth of Content |

"Describe the depth of content provided by the learning tool." |

| Ease of Understanding |

"Was the information easy to understand?" |

| Engagement |

"How engaging was the learning method in maintaining your interest during the task?" |

| Performance Compared to Usual Methods |

"Compared to usual study methods, how did this one perform?" |

| Critical Thinking |

"How did this learning method affect your critical thinking?" |

| Likelihood of Future Use |

"How likely are you to use this learning method again?" |

Table 2.

Baseline scores and perception-score differences across 12 domains for Arm 1 and Arm 2. Baseline (T0) scores are shown where available. A dash (–) indicates that the domain was not assessed in the T0 (baseline) questionnaire. Significant findings are marked with an asterisk (*p < 0.050). Highlighted boxes show statistically significant improvements, with green indicating improvements from both arms and yellow in one arm only. SD: Standard Deviation. In both arms, chatbot use led to significantly higher scores for ease of use, perceived quality of information, ease of understanding, and engagement (p < 0.050). Domains such as efficiency, confidence in applying information, performance, and likelihood of future use showed significant changes in one arm only. Effect sizes ranged from moderate to large for significant comparisons, indicating meaningful differences.

Table 2.

Baseline scores and perception-score differences across 12 domains for Arm 1 and Arm 2. Baseline (T0) scores are shown where available. A dash (–) indicates that the domain was not assessed in the T0 (baseline) questionnaire. Significant findings are marked with an asterisk (*p < 0.050). Highlighted boxes show statistically significant improvements, with green indicating improvements from both arms and yellow in one arm only. SD: Standard Deviation. In both arms, chatbot use led to significantly higher scores for ease of use, perceived quality of information, ease of understanding, and engagement (p < 0.050). Domains such as efficiency, confidence in applying information, performance, and likelihood of future use showed significant changes in one arm only. Effect sizes ranged from moderate to large for significant comparisons, indicating meaningful differences.

Table 3.

Mean performance scores across study arms and tasks. This table summarises mean performance scores (percentage correct) for each study arm and task. No comparisons reached statistical significance. However, chatbot use in Task 1 was associated with a higher mean score compared to conventional tools. Within-arm differences between tasks were also non-significant, though trends favoured chatbot use. SD = Standard Deviation; CI = Confidence Interval.

Table 3.

Mean performance scores across study arms and tasks. This table summarises mean performance scores (percentage correct) for each study arm and task. No comparisons reached statistical significance. However, chatbot use in Task 1 was associated with a higher mean score compared to conventional tools. Within-arm differences between tasks were also non-significant, though trends favoured chatbot use. SD = Standard Deviation; CI = Confidence Interval.

| Comparison |

Task 1 Mean Score % (SD) |

Task 2 Mean Score % (SD) |

Mean Difference (%) |

95% CI |

p-value |

| Task 1: Arm 1 vs Arm 2 |

71.43 (15.06) |

54.29 (23.13) |

17.14 |

-1.20 to 35.48 |

0.065 |

| Task 2: Arm 2 vs Arm 1 |

63.33 (18.92) |

68.33 (26.59) |

-5 |

-16.68 to 26.68 |

0.634 |

| Within Arm 1: Task 1 vs Task 2 |

71.43 (15.06) |

68.33 (26.59) |

-3.1 |

-15.41 to 21.60 |

0.7139 |

| Within Arm 2: Task 1 vs Task 2 |

54.29 (23.13) |

63.33 (18.92) |

9.04 |

-23.09 to 4.99 |

0.179 |

Table 4.

Themes related to chatbot ability and their associated features and functions. This table presents key themes and attributes identified through focus group analysis, highlighting perceived strengths (e.g., accuracy, speed, curriculum fit) and areas for improvement (e.g., technical limitations, further development) in the context of chatbot-assisted learning.

Table 4.

Themes related to chatbot ability and their associated features and functions. This table presents key themes and attributes identified through focus group analysis, highlighting perceived strengths (e.g., accuracy, speed, curriculum fit) and areas for improvement (e.g., technical limitations, further development) in the context of chatbot-assisted learning.

| Ability |

Features and Functions |

| Accuracy |

Curriculum fit |

| Complexity |

Focused questions |

| Credibility |

Further development |

| Depth |

Functional use case |

| Efficiency |

Openness to AI as a learning tool |

| Speed |

Technical limitations |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).