1. Introduction

Aphasia, predominantly caused by left-hemispheric stroke, is a debilitating language impairment that hinders speech production and/or understanding [

1,

2]. Non-fluent aphasia is generally linked to lesions in anterior language regions, notably the inferior frontal gyrus (Broca’s area), which impair articulatory and phonological functions [

3]. Although spontaneous recovery may occur in the acute and subacute phases, most individuals reach a recovery plateau within the first year post-stroke [

4,

5]. During the chronic phase, aphasia frequently becomes resistant to standard therapy, resulting in several patients experiencing enduring communication impairments and few avenues for substantial recovery. This clinical stalemate highlights the pressing necessity for personalized, circuit-oriented therapies that might reactivate inactive brain networks. One promising approach for these circuit-oriented therapies involves transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS), a non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) technique capable of modulating cortical excitability and promoting long-term plastic changes [

6] Conventional tDCS studies have demonstrated considerable success in targeting perilesional areas with anodal stimulation [

7,

8]; however, effect sizes are constrained and exhibit significant variability among patients. Recent meta-analyses underscore this diversity, identifying patient-specific characteristics such as lesion location, chronicity, and neuroanatomical variations as modifiers of response. These results have led to a transition towards multisite and network-targeted methodologies, which seek to influence scattered cortical networks associated with language processing by synchronizing stimulation targets with neurocognitive models [

9,

10]. In our previous study, we demonstrated that multisite tDCS targeting the dorsal stream of language, combined with adaptive cognitive training, produced significant short- and medium-term improvements in speech production in a person with chronic non-fluent aphasia [

11]. These behavioral gains were accompanied by changes in functional connectivity in left-lateralized language networks, supporting the relevance of network-guided neuromodulation approaches. The language training in that study was tailored to address the individual's specific weaknesses in phonological, lexical, and syntactic areas. This method changes the difficulty and content of each session based on how the patient's language skills are changing, which is different from normal rehabilitation protocols that usually employ predefined task sets.

This study builds upon previous research by investigating a bi-hemispheric multisite anodal tDCS montage in a second example of chronic non-fluent aphasia, emphasizing bilateral dorsal stream activation. We sought to assess the distinct effects of uni-hemispheric versus bi-hemispheric stimulation in conjunction with language-oriented cognitive training. We posited that this integrated intervention would facilitate the recovery of both speech production and understanding by augmenting functional restructuring within and across hemispheres. This is one of the first case studies to systematically combine bi-hemispheric, network-targeted tDCS with individualized language instruction in a patient with chronic, treatment-resistant aphasia. Even with these encouraging developments, the effects of bi-hemispheric multisite tDCS on behavioral and neurological outcomes in chronic aphasia are still insufficiently investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

The study was conducted ensuring the participants´ protection by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Life and Health Sciences (Comissão de Ética para as Ciências da Vida e da Saúde) of the University of Minho (approval number SECVS 014/2016). Written informed consent was obtained from the participant for both participation and publication of anonymized clinical data and images.

2.2. Case Presentation

This case study followed a protocol similar to the one previously published by our group [

11], which combined adaptive language training with multisite transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) in chronic post-stroke aphasia.

Albert (fictitious name) is a right-handed male and retired medical doctor who, at the age of 55 (in 2013), suffered an ischemic stroke in the left middle cerebral artery following the surgical removal of a left carotid body paraganglioma. In the acute phase, he was diagnosed with transcortical motor aphasia, characterized by profound speech production deficits, including phonetic paraphasia and speech apraxia. Neuropsychological assessments also revealed impairments in attention, working memory, and executive functioning. Although he initially exhibited right-sided hemiparesis, full motor recovery was achieved by the time of this intervention.

Over the following years, Albert demonstrated persistent deficits in verbal fluency and speech articulation. His expressive language remained limited to short, fragmented utterances composed primarily of basic nouns and verbs. He experienced substantial difficulty conveying complex ideas and understanding syntactically demanding or lengthy sentences. Despite undergoing multiple rounds of conventional speech-language therapy (SLT) and participating in online cognitive rehabilitation programs, these efforts resulted in only modest, short-lived improvements. Consequently, Albert continued to face significant challenges in everyday communication and social interaction.

At baseline, Albert presented marked deficits across various language domains, including verbal working memory, phonemic and semantic fluency, auditory sentence processing, reading, spelling, and lexical retrieval. In contrast, his non-verbal cognitive abilities—such as visuospatial construction, visual working memory, attention, and processing speed—were preserved. He reported no clinically significant symptoms of depression or anxiety. Notably, he had no prior exposure to NIBS, including tDCS.

Given the chronicity and severity of Albert’s language impairment, a tailored intervention was developed to target both expressive and receptive language functions. The treatment protocol combined a personalized language training program with a bi-hemispheric, multisite anodal tDCS montage targeting bilateral dorsal language streams.

Conventional interhemispheric rebalancing methods generally employ anodal stimulation on the left hemisphere and cathodal on the right to mitigate maladaptive activity in the right hemisphere [

16]. However, recent findings indicate that bilateral anodal stimulation with extracephalic references can enhance network-level plasticity without directly suppressing right-hemispheric areas [

9,

10]. This method may promote collaborative reconfiguration across both hemispheres, particularly when stimulation is administered simultaneously with functionally focused training [

7,

8].

In our approach, anodes were positioned over the bilateral dorsal stream regions (F5/CP5 on the left and F6/CP6 on the right), while extracephalic cathodes on the shoulders mitigated direct inhibitory effects on cortical areas, thereby enhancing the focused regulation of language networks. This dispersed, excitatory arrangement signifies a transition from therapies focusing on focal lesions to those influenced by network dynamics, prioritizing functional connection and collaboration above mere suppression.

2.3. Study Design and Timeline

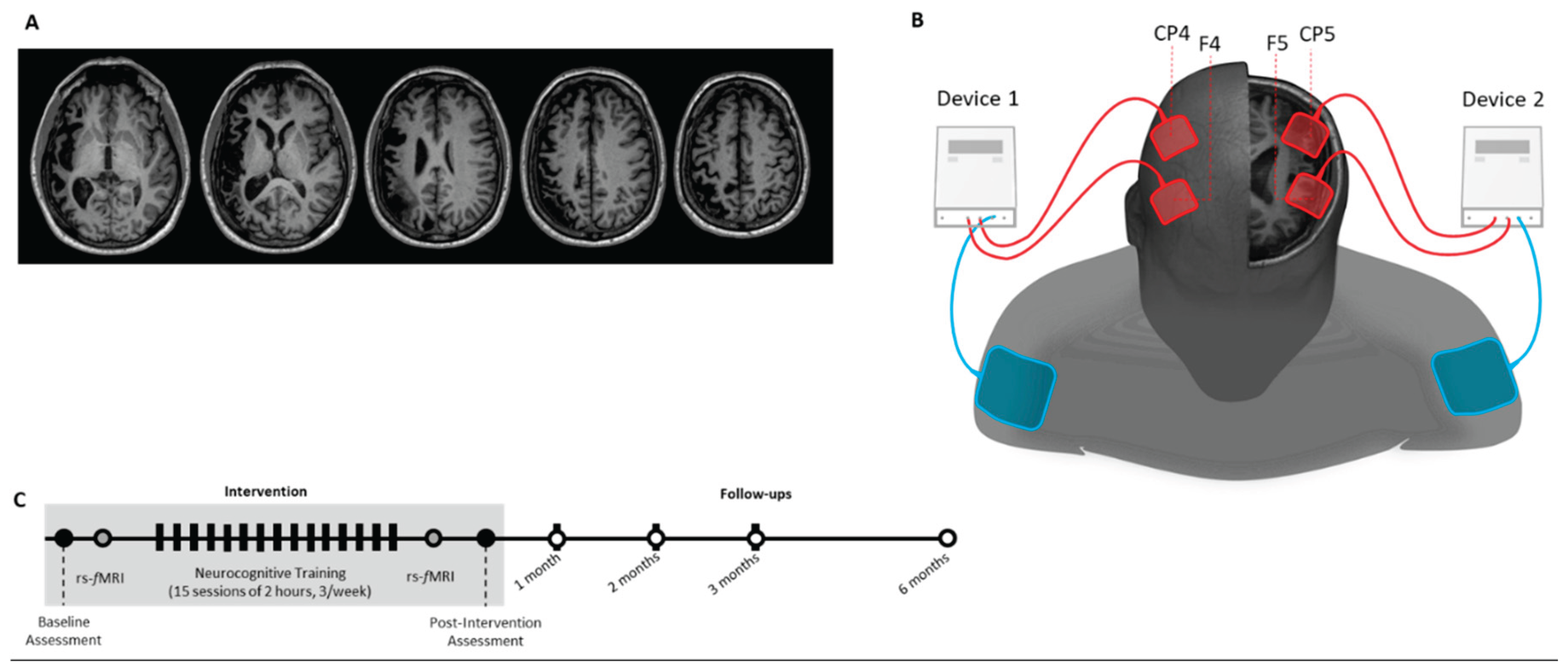

This open-label case study comprised a baseline assessment, an intervention phase combining adaptive language training with multisite transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS), and a series of follow-up assessments extending up to six months post-intervention. Resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) scans were acquired at baseline and immediately after the final session to assess changes in functional connectivity. EPI images were not included in the figure due to their lower spatial resolution and T2-contrast.

Follow-up assessments were conducted at five timepoints: immediately post-intervention, and at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months. To reinforce treatment effects, a booster session replicating the original intervention protocol was administered on the same day as each follow-up assessment. The intervention specifically targeted the dorsal language stream, with the goal of enhancing speech production by increasing activity in left perilesional areas through multisite anodal tDCS.

2.4. Assessments and Follow-Ups

The baseline and follow-up assessments focused exclusively on psycholinguistic testing using the Portuguese adaptation of the Psycholinguistic Assessments of Language Processing in Aphasia (PALPA-P) [

12]. Language production was evaluated through the following subtests: Word Minimal Pairs, Nonword Minimal Pairs, and Repetition (Imageability × Frequency, Nonword, and Sentence). Language comprehension was assessed using the Auditory Sentence Comprehension and Locative Relations subtests. Reading abilities were evaluated via the Spoken Letter–Written Letter Matching and Syllable Length tasks. Clinical scales were not administered due to Albert’s difficulty in completing self-report questionnaires.

2.4.1. Statistical analysis

To evaluate whether changes in Albert’s performance were statistically and clinically meaningful, we calculated the Reliable Change Index (RCI) for each relevant subtest of the PALPA-P across follow-up assessments. The RCI is a well-established method used to determine whether the difference between pre- and post-intervention scores exceeds what would be expected due to measurement error or natural variability [

13].

RCI values were computed using the following formula:

where

SEdiff =

×

SEM, and SEM (standard error of measurement) was derived from normative data validated for the Portuguese version of the PALPA [

12]. An RCI value greater than ±1.96 was considered statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (p < .05, two-tailed). This method allowed us to determine whether the changes observed across the follow-up time points reflected true, reliable improvements rather than measurement error or chance fluctuations. This approach allowed us to determine whether changes observed across follow-up time points reflected reliable improvements rather than chance fluctuations.

2.5. Language Training

The language training program adhered to the same technique as utilized in the prior case of Mary [

11] but was tailored to Albert’s specific impairments found at the baseline PALPA-P assessment. Tasks were chosen and arranged to address critical deficits in phonological processing, syntactic comprehension, and lexical retrieval. This adaptive method sought to enhance language rehabilitation by aligning the cognitive demands and linguistic intricacy of each assignment with Albert’s developing abilities, thereby promoting engagement and neuroplasticity during the intervention. The intervention consisted of 15 language training sessions, with each session lasting two hours, three times per week (totaling 30 hours). Additional booster sessions were administered on the same day as each follow-up psycholinguistic assessment (except at the 1-year follow-up), bringing the total number of sessions to 20. Training in speech production focused on phonological processing and repetition tasks (see

Table 1). Stimuli were selected from the European Portuguese lexical database Minho Word Pool [unlisted; if this is a published source, please provide citation details] and controlled for frequency and imageability. Words were distributed across sessions in order of difficulty, ranging from high-frequency/high-imageability items (e.g., água [water]) to low-frequency/low-imageability items (e.g., reversível [reversible]). None of the trained items were used in the assessments or follow-ups. Exercises included phoneme identification, deletion, replacement, and discrimination. Repetition exercises used both the lexical stimuli and specially constructed pseudowords. For speech comprehension, tasks required the participant to answer questions involving complex sentence structures and to process locative relationships. This dual focus aimed to simultaneously target both production and comprehension deficits identified at baseline.

2.6. tDCS Parameters

Bi-hemispheric multisite transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) was administered using two independent stimulators: the HDCStim (Newronika, Milan, Italy) and the Eldith DC Stimulator Plus (NeuroConn, Germany). The bi-hemispheric, multisite approach was guided by the principle of interhemispheric rebalancing, aiming to upregulate activity in the lesioned (left) hemisphere while downregulating maladaptive overactivation in the contralesional (right) hemisphere. The goal of stimulating both anterior and posterior language areas bilaterally was to promote coordinated plasticity changes throughout the distributed language networks. Each device delivered stimulation to one hemisphere, targeting language-relevant regions corresponding to Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas. Stimulation was delivered via four saline-soaked anodal electrodes (25 cm²; 5 × 5 cm), positioned over F5, F6, CP5, and CP6 according to the 10–20 EEG system. Two large extracephalic reference electrodes (100 cm²; 10 × 10 cm) were placed over the ipsilateral shoulders to minimize cortical current flow beneath the cathodes.

A current of 1 mA was applied to each anode (current density = 0.04 mA/cm²) for 20 minutes, with 15-second ramp-up and ramp-down periods. Stimulation was applied concurrently with the language-focused colanguages training tasks. This timing was chosen to promote activity-dependent plasticity by enhancing cortical excitability while the participant was actively engaging language networks related to phonological processing, syntactic comprehension, and lexical access (

Figure 1). Throughout all sessions, Albert was continuously monitored for adverse effects such as skin irritation, headache, dizziness, or discomfort at the electrode sites. No adverse events were reported, and tolerability was rated as high across all sessions. Impedance levels were checked prior to each session to ensure they remained below manufacturer-recommended thresholds.

2.7. Resting-State fMRI

2.7.1. Data Acquisition

Resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) data were collected using a Siemens Magnetom Tim Trio 3.0 T MRI system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). A 7-minute acquisition was performed, yielding 210 volumes using a BOLD-sensitive echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, echo time (TE) = 29 ms, flip angle = 90°, field of view (FOV) = 1554 mm, matrix size = 64 × 64, in-plane resolution = 3 × 3 mm², and slice thickness = 3 mm across 39 contiguous axial slices. During the scan, the participant was instructed to remain awake with eyes closed and to refrain from engaging in any specific mental task. Self-report after scanning confirmed compliance and absence of sleep.

2.7.2. Preprocessing of fMRI Data

Visual inspection of the raw data ensured the absence of significant motion artifacts. To allow for signal equilibrium and participant adaptation to scanner noise, the first five volumes were excluded from further analysis. Preprocessing was carried out using the SPM12 software package (Statistical Parametric Mapping; Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK). Slice-timing correction was applied using the first slice as a temporal reference and Fourier phase shift interpolation. Realignment was performed using a six-parameter rigid-body transformation, with realignment parameters estimated at 0.9 quality, a 4 mm sampling distance, and 5 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel smoothing. Only scans with translational displacement < 2 mm and rotational movement < 1° were retained.

Spatial normalization to the MNI standard space was performed via non-linear registration to the EPI template using trilinear interpolation. The normalized data were subsequently smoothed with an 8 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel to reduce spatial noise. Temporal filtering was conducted using a band-pass filter (0.01–0.08 Hz), and linear trends were removed to eliminate low-frequency drifts and high-frequency noise.

2.7.3. Independent Component Analysis and Network Identification

Independent component analysis (ICA) was implemented using the Group ICA of fMRI Toolbox (GIFT v4.0b; Correa et al., 2005;

http://www.icatb.sourceforge.net). The pipeline involved three primary stages: dimensionality reduction via Principal Component Analysis (PCA), estimation of group-level independent components, and subject-specific back-reconstruction. A total of 20 independent components were extracted based on an optimal trade-off between spatial specificity and statistical reliability, using the Infomax algorithm. To assess the stability of component estimation, the ICASSO framework was employed with 20 repetitions.

The resulting components, expressed as t-statistic maps, were transformed into Z-score maps to reflect the relative contribution of individual voxels to each component. These components were visually examined and spatially correlated with canonical resting-state networks (RSNs) based on established templates (Shirer et al., 2012). To evaluate connectivity changes, Z-score maps from baseline and post-intervention were contrasted. “Differences were considered significant when exceeding a Z-score threshold of ±2.5 and a minimum cluster extent of 10 voxels, for the independent components of each moment (i.e., baseline and post-intervention maps analyzed separately prior to direct comparison). This thresholding ensured that only spatially meaningful activations were retained before contrast analysis. The final contrast maps between timepoints could therefore display voxel-wise Z-values lower than 2.5, as only thresholded component maps entered this step.

3. Results

3.1. Neuropsychological Assessment

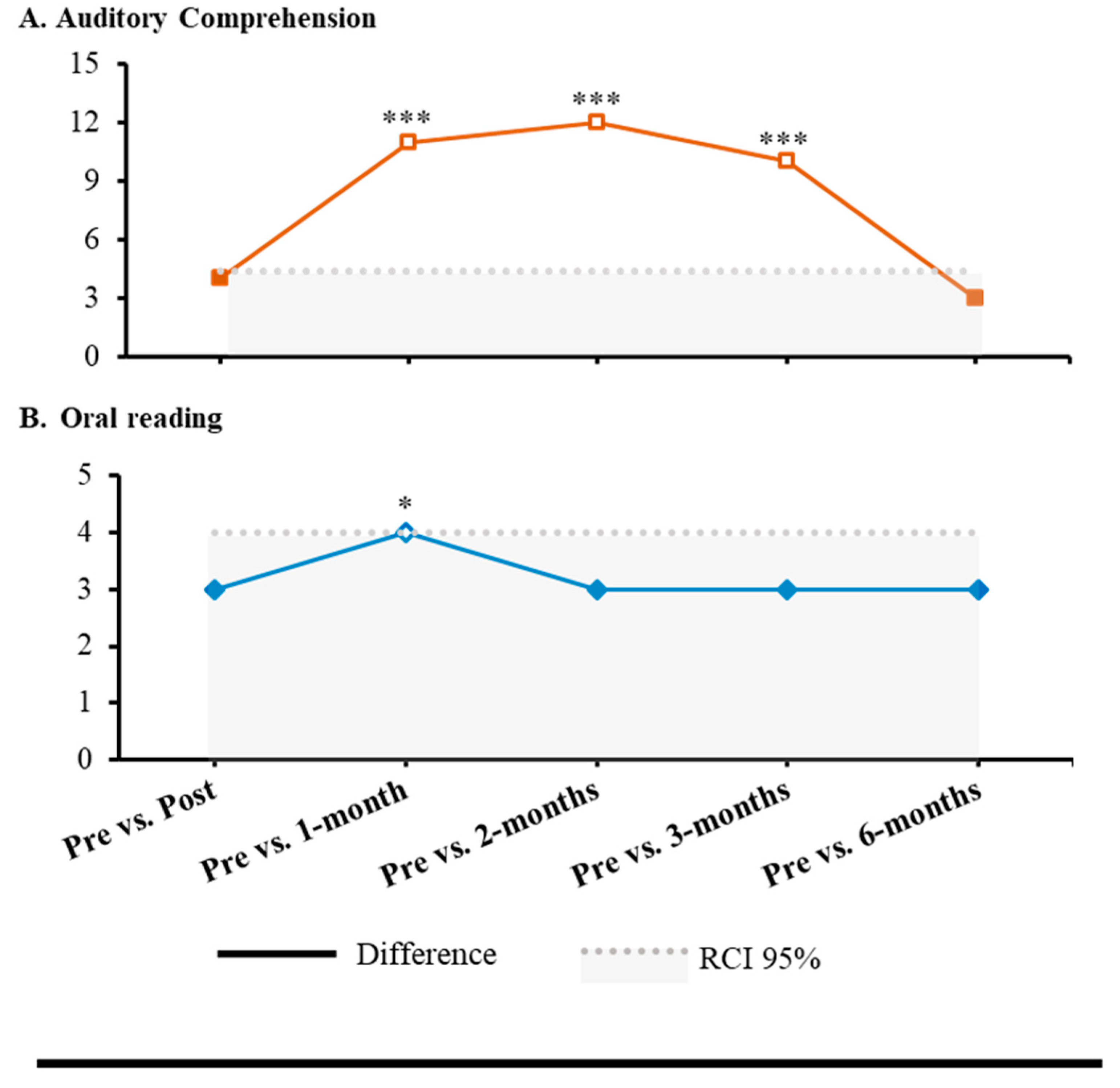

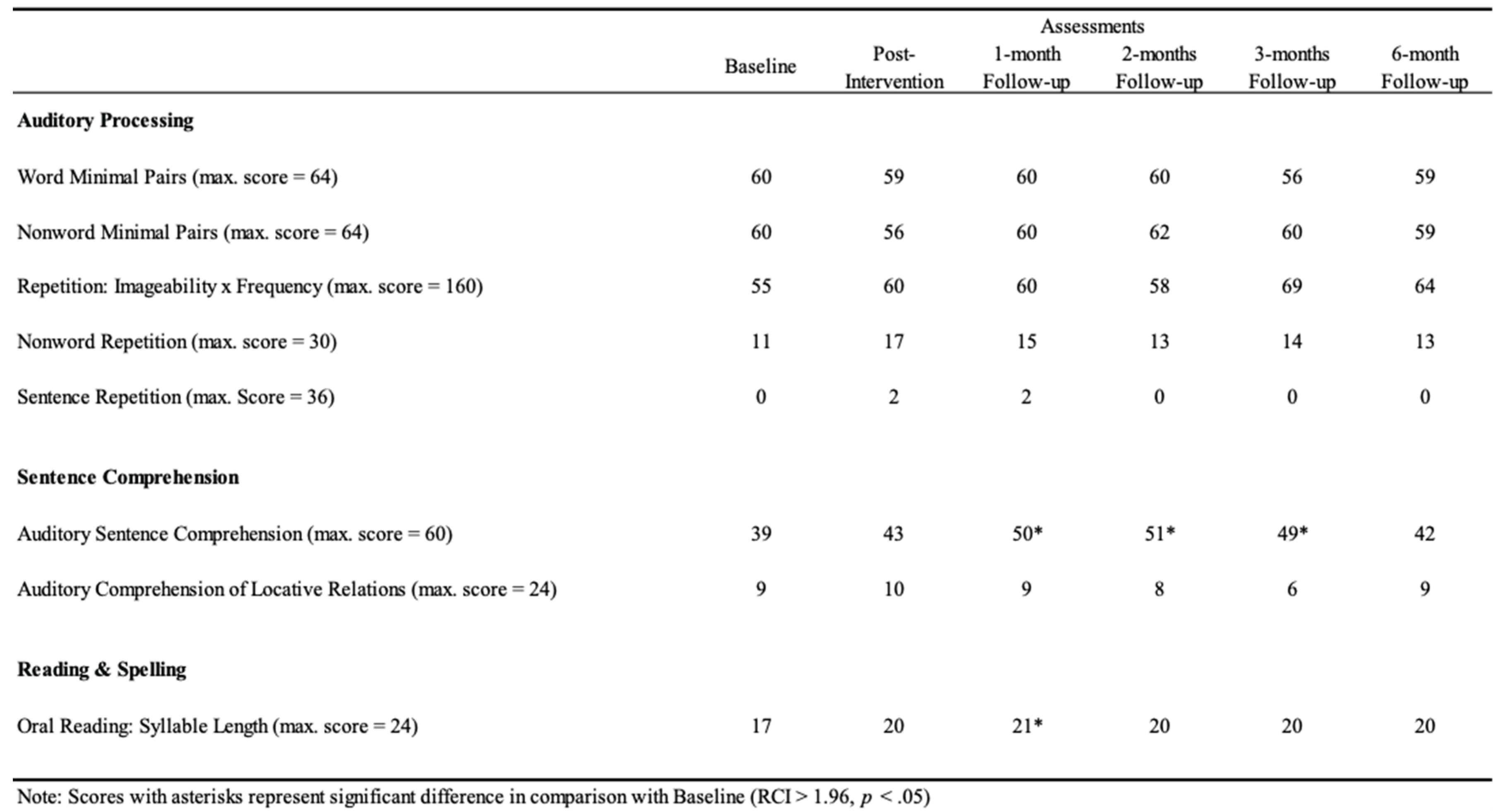

Albert did not show significant improvements in Auditory Processing (p > .05), while significant effects were observed in Sentence Comprehension and Reading and Spelling of PALPA-P (

Table 1) in several follow-ups (i.e., post-intervention, 1-month, 2-months, 3-months, and 6-months) when compared with baseline assessment. In Sentence Comprehension, a statistical improvement was found in Auditory Sentence Comprehension (1-month: RCI = 4.97, p < .001; 2-months: RCI = 5.42, p < .001; 3-months: RCI = 4.51, p < .001). Moreover, in Reading and Spelling, a statistical improvement was observed in Oral Reading: Syllable Length (1-month: RCI = 1.96, p = .025) (

Figure 2). Every other comparison was not statistically significant (p > .05) (

Table 1).

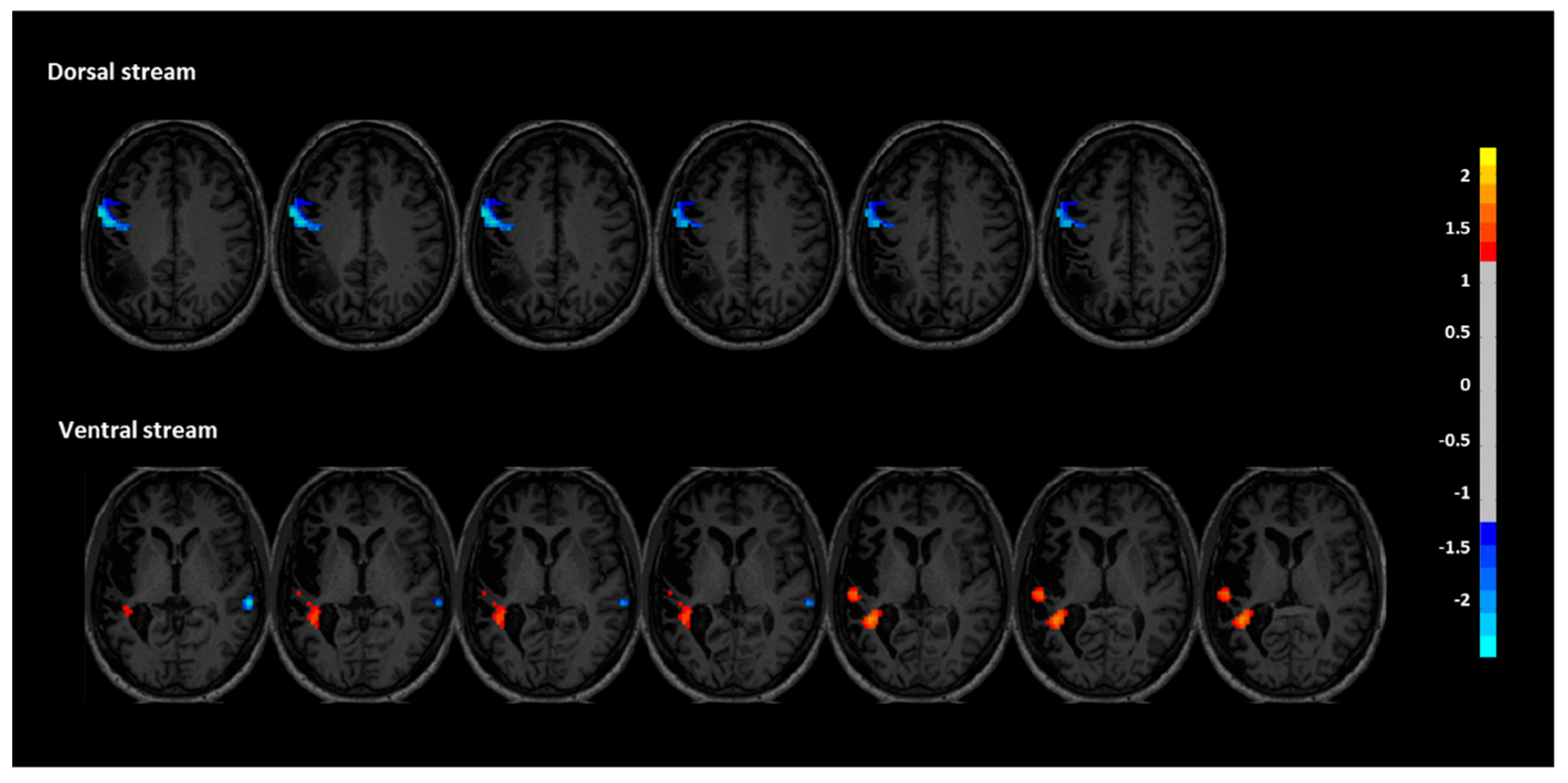

3.2. Resting-State fMRI

Functional connectivity (FC) analyses revealed distinct post-intervention changes in both the dorsal and ventral language streams, supporting a reorganization of language-related networks. In the dorsal stream, FC was significantly decreased in the left inferior frontal and precentral regions (peak coordinates: X = -60, Y = 0, Z = 33), with a cluster size of 139 voxels and a z-score of -0.894. This reduction may reflect a normalization or rebalancing of hyperconnectivity in perilesional motor-speech regions often observed in chronic aphasia. No significant increases were found in the dorsal regions of the right hemisphere. In contrast, the ventral stream showed signs of enhanced engagement. Specifically, two clusters within the left superior temporal gyrus demonstrated increased FC (X = -33, Y = -42, Z = 12 and X = -54, Y = -24, Z = 6), with cluster sizes of 109 and 12 voxels, and z-scores of 1.223 and 0.934, respectively. These changes suggest a strengthened role of left temporal areas, which are critical for auditory comprehension and phonological decoding. Additionally, decreased FC was observed in the right superior temporal region (X = -42, Y = 15, Z = -12), with a cluster size of 12 and a z-score of -0.806. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that reducing maladaptive right-hemisphere overactivation may facilitate improved language function through interhemispheric rebalancing. Together, these findings suggest that the intervention facilitated plastic changes that increased connectivity of the left-hemispheric language network while downregulating compensatory activity in the right hemisphere, particularly in the ventral stream (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

This case report shows the effectiveness of a precision-guided neuromodulatory intervention in a patient with chronic, non-fluent aphasia that had been resistant to multiple prior treatments. Albert had undergone several sessions of conventional speech-language therapy and cognitive rehabilitation without achieving lasting functional enhancements. His persistent expressive and receptive language deficits—nearly a decade post-stroke—underscore the therapeutic challenges inherent in chronic aphasia and the pressing need for customized, circuit-level interventions.

This single-case study expands upon our prior research [

11] by investigating the effects of bi-hemispheric multisite anodal tDCS in conjunction with language-focused training in an individual with chronic non-fluent aphasia. Our previous research showed that unilateral multisite tDCS targeting the dorsal stream could enhance behavioral and neurological aspects of speech production and comprehension. The present study examines the supplementary effects of a bi-hemispheric montage.

By stimulating both hemispheres simultaneously and assessing outcomes through repeated behavioral testing and resting-state functional connectivity (rs-fMRI), this study extends prior findings of the usefulness of the combination between tDCS and language training and provides further insight into the interhemispheric mechanisms of recovery in a participant with aphasia. We hypothesized that this bilateral approach would facilitate functional restructuring across hemispheres and augment improvements in both expressive and receptive language functions. Our results provided partial validation for this idea. Albert showed statistically significant improvements in auditory sentence comprehension and oral reading, particularly at the 1- and 3-month follow-ups. These behavioral improvements were accompanied by enhanced functional connectivity (FC) in left-lateralized language networks, alongside diminished connection in right-hemispheric areas normally linked to maladaptive plasticity in aphasia. This change is in line with the idea of interhemispheric rebalancing [

5], which means that the intervention helped the brain organize language processing in a more efficient and lateralized way.

The improvements in phrase comprehension noted in Albert’s instance are likely due to the downregulation of activity in the right superior temporal gyrus, along with enhanced connection in the left superior temporal lobe. The observed modifications in the brain align with previous studies suggesting that the modulation of right-hemisphere hyperactivity—through direct suppression or enhanced activation of left-hemisphere language regions—can lead to improved linguistic outcomes [

15,

16]. The absence of notable improvements in phonological processing corresponds with the diminished functional connectivity noted in the left inferior frontal and precentral regions, which are essential for phonological encoding and articulatory planning. This pattern is different from our previous case study that used unilateral multisite anodal tDCS, which showed that connectivity in left perilesional regions increased and phonological tasks improved as a result [

11]. The results from Albert's case indicate that bi-hemispheric anodal stimulation might elicit distinctive neuronal dynamics, potentially by interrupting or spreading concentrated activity in the left hemisphere within chronically compromised networks. This may elucidate why, in this instance, we noted more uniform improvements in sentence comprehension and oral reading, which depend more significantly on temporal and ventral stream processing, where enhanced functional connectivity was observed. The case-specific variations highlight the significance of stimulation montage and target network selection, emphasizing the necessity for personalized, network-informed strategies in neuromodulation therapy for aphasia. Moreover, this divergence in outcomes highlights the need for further investigation into how unilateral versus bilateral stimulation strategies may differentially impact distinct language components, such as phonology versus comprehension, particularly in chronic and treatment-resistant profiles.

Our results support the idea that using tDCS with language training in a network-specific and functionally directed way can improve recovery by activating specific brain circuits. Specifically, the execution of personalized cognitive training may have contributed to behavioral and neurological enhancements. Aligning each task with Albert’s unique language profile probably made him more interested in the tasks and activated the dorsal and ventral language streams in a way that was relevant to the tasks. This tailored integration of targeted cognitive deficit training with individualized tDCS montages enhances the progression of precision-guided neurorehabilitation.

The biggest improvements happened in the first three months, but booster sessions at each follow-up may have helped sustain the effects for a short time. The absence of substantial improvement after six months underscores the urgent necessity for more rigorous or continuous reinforcement tactics, such as repeated booster cycles or adaptive dose schedules, to extend the therapeutic effects.These results are consistent with prior studies demonstrating that therapy persistence remains a major challenge in post-stroke aphasia rehabilitation.

In addition to tDCS, increasing data supports the efficacy of transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) as a customized neuromodulation tool. Previous research demonstrated that tailoring tACS parameters to align with individual endogenous event-related potentials, namely the P3 component [

22], could enhance cognitive responses by synchronizing stimulation with endogenous oscillatory activity [

11]. This study, although conducted on a healthy sample, highlights a possible avenue for clinical application, especially in aphasia rehabilitation. Combining EEG-derived biomarkers with real-time stimulation protocols could allow physicians to modify electrode configurations, stimulation frequency, and timing, hence improving therapy accuracy and effectiveness. Subsequent study ought to investigate the effectiveness of closed-loop EEG–tACS protocols in individuals with post-stroke aphasia, particularly to mitigate oscillatory disruptions within language-related networks.

This case study provides significant insights into the possibilities of personalized, network-guided neuromodulation for persistent aphasia; however, some limitations must be acknowledged. The most important thing is that there is no sham-controlled condition, which makes it hard to say that the gains are only due to the intervention. Due to being a single-case research, the results are not applicable to other situations and should only be used with caution until they are confirmed in larger, more controlled investigations. Furthermore, the study exclusively employed performance-based psycholinguistic assessments; structured patient-reported outcomes (e.g., communicative confidence, quality of life) were not collected due to participants' difficulties with self-report questionnaires. Future study should include both behavioral and subjective measures to enhance the therapeutic relevance and validity of the results.

Building on this, future research must explore the feasibility and impact of home-based, web-based neuromodulation platforms for aphasia treatment. Recent expert opinion has endorsed the remote application of transcranial electrical stimulation (tES), such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), via mobile health devices [

18]. These virtual innovations could significantly improve scalability, convenience, and long-term adherence to therapy—particularly for individuals with limited access to clinic-based interventions. Future research should also focus on maximizing personalization of aphasia rehabilitation using digital or home-based tES technologies, which are remotely monitored and scalable therapies [

18]. Additionally, the use of electroencephalography (EEG)-based biomarkers, such as P300 event-related potentials (ERPs), in closed-loop systems can enable real-time modulation of stimulation protocols, potentially enhancing the specificity and effectiveness of neuromodulation methods [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Coupled with wearable EEG for biomarker-guided personalization [

21], such devices could support home-based, truly personalized brain stimulation therapies tailored to the individual’s unique neural profile and recovery trajectory.

5. Conclusions

This case report is an illustration of the therapeutic efficacy of precision-guided neuro-modulation in patients with chronic, treatment-resistant non-fluent aphasia. Despite having received repeated standard treatments for nearly a decade, Albert still had very severe expressive and receptive language impairment. The reported gains after a bi-hemispheric multisite anodal tDCS treatment, paired with individualized language-specific cognitive training, yield strong evidence supporting the need to customize both stimulation and behavioral therapy to one's own distinct neurological and linguistic characteristics.

The improvements on sentence reading and oral reading were not just statistically significant but also stable, indicating that the technique can cause long-lasting neuroplastic changes even in chronic aphasia. The behavioral effects were further substantiated by resting-state fMRI evidence, which indicated that there was a movement towards a more lateralized and functionally effective language network, characterized by in-creased connectivity in left-hemispheric regions and reduced maladaptive right-hemisphere activity. The differential impact on phonological processing relative to previous unilateral stimulation also highlights the importance of individually tailoring protocol according to patient-specific neural profiles.

Together, these findings support the application of network-based, bilateral neuro-modulation protocols as a valid treatment option for patients who have plateaued on conventional rehabilitation. Future work would be well served to focus on optimizing stimulation parameters, including the use of neurophysiologic biomarkers to predict responsivity, and cross-validation in larger controlled samples. Expanded accessibility to personalized, home-based neuromodulation technology also may represent a viable pathway towards scalable and sustained recovery from post-stroke aphasia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C and J.L., and A.J.M.; methodology, S.C and J.L., and A.J.M.; software, M.S.; validation, S.C., A.J.M. and J.L.; formal analysis, A.J.M. and M.S.; investigation, S.C.; resources, A.S.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, A.J.M.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, S.C and J.L.; project administration, S.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was conducted at Centro de Investigação em Psicologia (CIPsi), School of Psychology, University of Minho, supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT; UID/01662) through national funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Life and Health Sciences of the University of Minho (protocol number SECVS 014/2016). All procedures involving human participants adhered to the institutional ethical standards and applicable national regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the participant involved in the study. Written informed consent was also obtained from the participant for the publication of this paper, including the use of anonymized clinical details and images.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions but may be made available upon reasonable request. Interested researchers may contact the corresponding author (sandrarc@psi.uminho.pt) to inquire about access, subject to institutional approval and data sharing agreements.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to Albert (pseudonym) for his unwavering commitment, patience, and motivation, which were essential to the completion of this study. We also wish to thank the clinical psychology and neuropsychology students who contributed to data collection during their internships; their dedication and professionalism were greatly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| tDCS |

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| CT |

Cognitive Training |

| fMRI |

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| rs-fMRI |

Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| FC |

Functional Connectivity |

| PALPA |

Psycholinguistic Assessments of Language Processing in Aphasia |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| tACS |

Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation |

| NIBS |

Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation |

| SLT |

Speech-Language Therapy |

| ROI |

Region of Interest |

| MNI |

Montreal Neurological Institute |

| ICA |

Independent Component Analysis |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| RSN |

Resting-State Network |

| RCI |

Reliable Change Index |

References

- Heiss, W.D.; Thiel, A. A proposed regional hierarchy in recovery of post-stroke aphasia. Brain Lang. 2006, 98(1), 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saur, D.; Hartwigsen, G. Neurobiology of language recovery after stroke: Lessons from neuroimaging studies. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93(1 Suppl), S15–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code, C.; Petheram, B. Delivering for aphasia. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2011, 13(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons-Mackie, N. A solution to the discharge dilemma in aphasia: Social approaches to aphasia management. Aphasiology 1998, 12(3), 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkeltaub, P.E.; Messing, S.; Norise, C.; Hamilton, R.H. Are networks for residual language function and recovery consistent across aphasic patients? Neurology 2011, 76(20), 1726–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Cohen, L.G.; Wassermann, E.M.; Priori, A.; Lang, N.; Antal, A.; Paulus, W.; Hummel, F.; Boggio, P.S.; Fregni, F.; Pascual-Leone, A. Transcranial direct current stimulation: State of the art 2008. Brain Stimul. 2008, 1(3), 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangolo, P.; Fiori, V.; Calpagnano, M.A.; Campana, S.; Razzano, C.; Caltagirone, C.; Marini, A. tDCS over the left inferior frontal cortex improves speech production in aphasia. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biou, E.; Cassoudesalle, H.; Cogné, M.; Sibon, I.; De Gabory, I.; Dehail, P.; Aupy, J.; Glize, B. Transcranial direct current stimulation in post-stroke aphasia rehabilitation: A systematic review. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 62(2), 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmochowski, J.P.; Datta, A.; Bikson, M.; Su, Y.; Parra, L.C. Optimized multi-electrode stimulation increases focality and intensity at target. J. Neural Eng. 2011, 8(4), 046011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffini, G.; Fox, M.D.; Ripolles, O.; Miranda, P.C.; Pascual-Leone, A. Optimization of multifocal transcranial current stimulation for weighted cortical pattern targeting from realistic modeling of electric fields. NeuroImage 2014, 89, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.J.; Lema, A.; Soares, J.M.; Sampaio, A.; Leite, J.; Carvalho, S. Functional neuroimaging and behavioral correlates of multisite tDCS as an add-on to language training in a person with post-stroke non-fluent aphasia: A year-long case study. Neurocase 2024, 30(1), 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, S.L.; Caló, S.; Gomes, I. PALPA: Provas de Avaliação da Linguagem e da Afasia; Cegoc-Tea: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, N.S.; Truax, P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59(1), 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangolo, P.; Marinelli, C.V.; Bonifazi, S.; Fiori, V.; Ceravolo, M.G.; Provinciali, L.; Tomaiuolo, F. Electrical stimulation over the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) determines long-term effects in the recovery of speech apraxia in three chronic aphasics. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 225(2), 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Y. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on naming and cortical excitability in stroke patients with aphasia. Neurosci. Lett. 2015, 589, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Chun, M.H.; Jung, S.E.; Park, S.J. Cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation of the right Wernicke’s area improves comprehension in subacute stroke patients. Brain Lang. 2011, 119(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, N.; Adali, T.; Li, Y.O.; Calhoun, V.D. Comparison of blind source separation algorithms for FMRI using a new MATLAB toolbox: GIFT. In ICASSP’05. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing - Proceedings 2005, 5, v–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Ekhtiari, H.; Antal, A.; Auvichayapat, P.; Baeken, C.; Benseñor, I.M.; Bikson, M.; Boggio, P.; Borroni, B.; Brighina, F.; et al. Digitalized transcranial electrical stimulation: A consensus statement. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 143, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criel, Y.; Depuydt, E.; De Clercq, B.; Raman, N.; Haekens, N.; Miatton, M.; Santens, P.; van Mierlo, P.; De Letter, M. Long-term functional connectivity alterations in the mismatch negativity, P300 and N400 language potentials in adults with a childhood acquired brain injury. Aphasiology 2024, 38(10), 1684–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.J.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Lema, A.; Gonçalves, Ó.F.; Fregni, F.; Leite, J.; Carvalho, S. Modulation of the cognitive event-related potential P3 by transcranial direct current stimulation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 132, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.J.; Lema, A.; Carvalho, S.; Leite, J. Tailoring transcranial alternating current stimulation based on endogenous event-related P3 to modulate premature responses: A feasibility study. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, A.; Malavera, A.; Doruk, D.; Morales-Quezada, L.; Carvalho, S.; Leite, J.; Fregni, F. Duration dependent effects of transcranial pulsed current stimulation (tPCS) indexed by electroencephalography. Neuromodulation 2016, 19(7), 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, J.; Morales-Quezada, L.; Carvalho, S.; Thibaut, A.; Doruk, D.; Chen, C.F.; Schachter, S.C.; Rotenberg, A.; Fregni, F. Surface EEG-transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) closed-loop system. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2017, 27(6), 1750026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).