Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

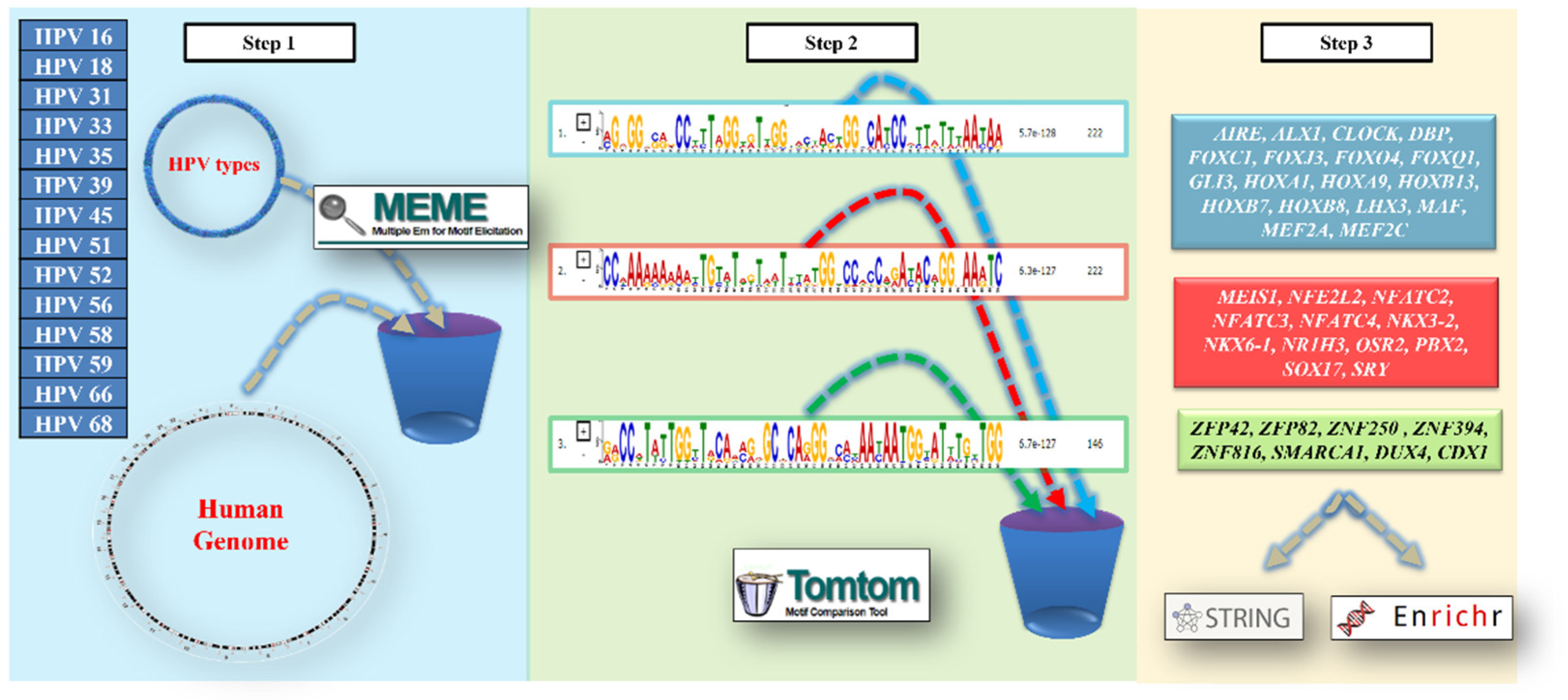

Materials and Methods

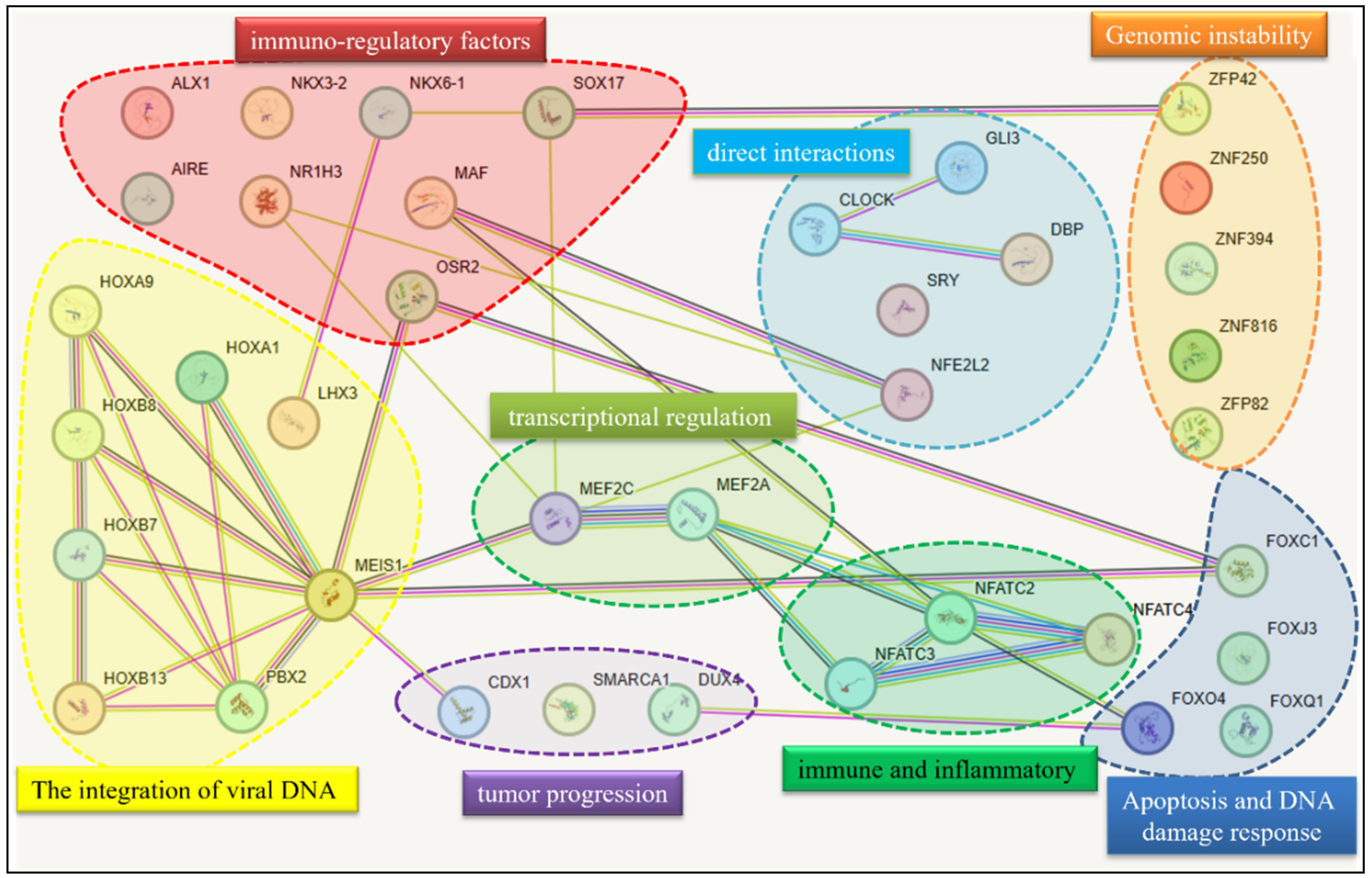

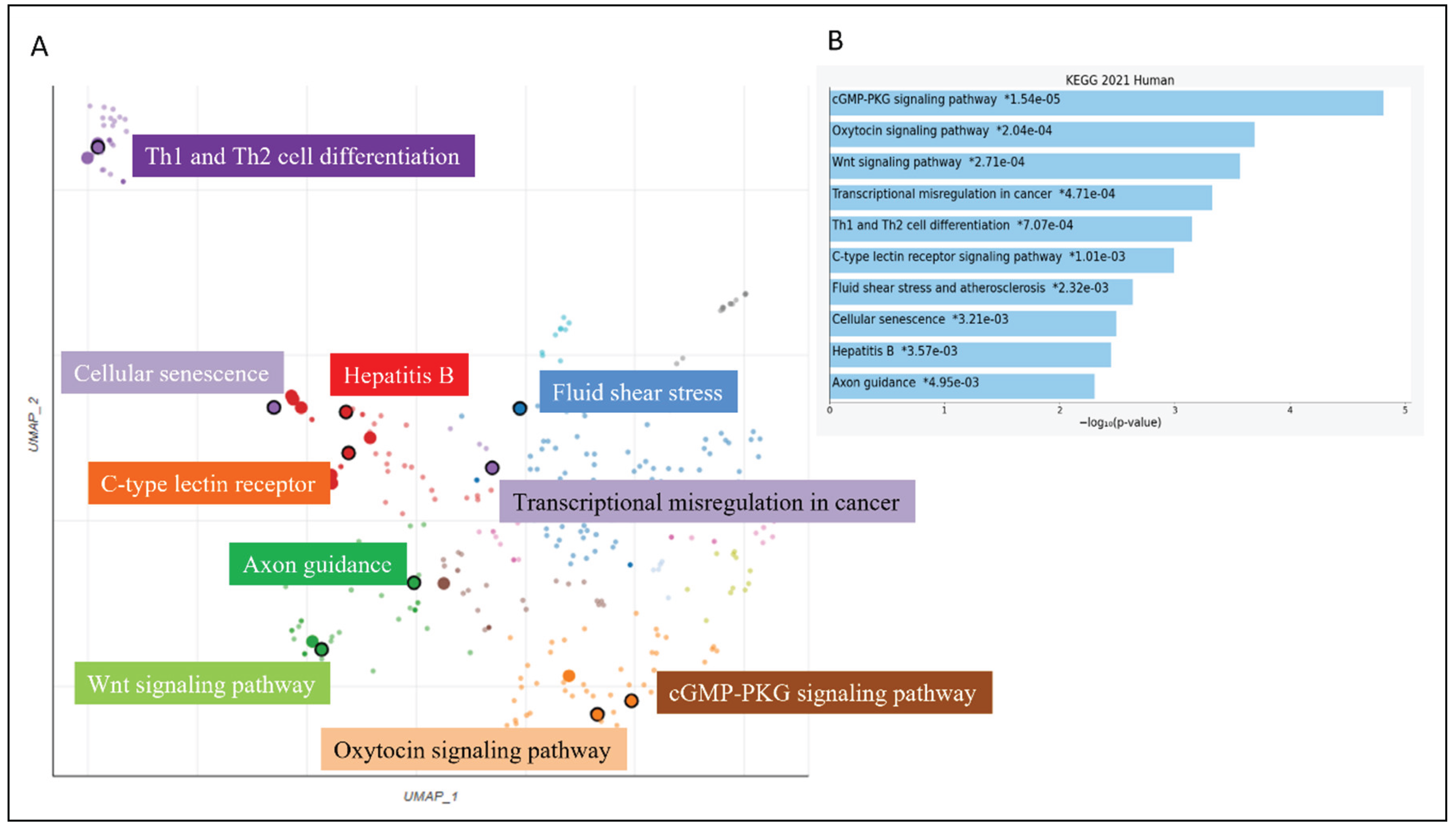

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

References

- Schiffman, M.; Castle, P.E.; Jeronimo, J.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Wacholder, S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 2007, 370, 890–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doorbar, J.; Egawa, N.; Griffin, H.; Kranjec, C.; Murakami, I. Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association. Rev. Med. Virol. 2015, 25, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, C.A.; Laimins, L.A. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: Pathways to transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A.; Bailey, T.L.; Noble, W.S. Quantifying similarity between motifs. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; Jensen, L.J.; von Mering, C. STRING v11: Protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.Y.; Tan, C.M.; Kou, Y.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Meirelles, G.V.; Clark, N.R.; Ma’ayan, A. Enrichr: Interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, C.A.; Laimins, L.A. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: Pathways to transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calnan, D.R.; Brunet, A. The FoxO code. Oncogene 2008, 27, 2276–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; He, H.; Jonsson, P.; Sinha, I.; Zhao, C.; Dahlman-Wright, K. AP-1 is a key regulator of proinflammatory cytokine TNFα-mediated triple-negative breast cancer progression. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 5068–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomis, R.R.; Alarcón, C.; He, W.; Wang, Q.; Seoane, J.; Lash, A.; Massagué, J. A FoxO–Smad synexpression group in human keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 12747–12752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.; Sukumar, S. The Hox genes and their roles in oncogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, C.B.; Selleri, L. Hox cofactors in vertebrate development. Dev. Biol. 2006, 291, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macián, F. NFAT proteins: Key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; McKinsey, T.A.; Nicol, R.L.; Olson, E.N. Signal-dependent activation of MEF2 transcription factors by dissociation from histone deacetylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 4070–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporn, M.B.; Liby, K.T. NRF2 and cancer: The good, the bad and the importance of context. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regl, G.; Neill, G.W.; Eichberger, T.; Kasper, M.; Ikram, M.S.; Koller, J.; Hintner, H.; Quinn, A.G.; Moyes, D.L.; Aberger, F. Human GLI2 and GLI1 are part of a positive feedback mechanism in basal cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2002, 21, 5529–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Kettner, N.M. The circadian clock in cancer development and therapy. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2013, 119, 221–282. [Google Scholar]

- Cassandri, M.; Smirnov, A.; Novelli, F.; Pitolli, C.; Agostini, M.; Malewicz, M.; Melino, G.; Raschellà, G. Zinc-finger proteins in health and disease. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 17071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaret, K.S.; Carroll, J.S. Pioneer transcription factors: Establishing competence for gene expression. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 2227–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, R. ARID1A loss in cancer: Towards a mechanistic understanding. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 190, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, L.N.; Yao, Z.; Snider, L.; Fong, A.P.; Cech, J.N.; Young, J.M.; van der Maarel, S.M.; Ruzzo, W.L.; Gentleman, R.C.; Tapscott, S.J. DUX4 activates germline genes, retroelements, and immune mediators: Implications for facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Dev. Cell 2012, 22, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.J.; Suh, E.R.; Lynch, J.P. The role of Cdx proteins in intestinal development and cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2004, 3, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, M.V.; Jones, M.R.; Rouillard, A.D.; Fernandez, N.F.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Koplev, S.; Jenkins, S.L.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Lachmann, A.; McDermott, M.G.; Monteiro, C.D.; Gundersen, G.W.; Ma’ayan, A. Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W90–W97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilz, R.B.; Casteel, D.E. Regulation of gene expression by cyclic GMP. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeto, A.; Nation, D.A.; Mendez, A.J.; Dominguez-Bendala, J.; Brooks, L.G.; Schneiderman, N.; McCabe, P.M. Oxytocin attenuates NADPH-dependent superoxide activity and IL-6 secretion in macrophages and vascular cells. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 295, E1495–E1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusse, R.; Clevers, H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 2017, 169, 985–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradner, J.E.; Hnisz, D.; Young, R.A. Transcriptional addiction in cancer. Cell 2017, 168, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnani, S. Th1/Th2 cells. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 1999, 5, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambuza, I.M.; Brown, G.D. C-type lectins in immunity: Recent developments. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2015, 32, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Haga, J.H.; Chien, S. Molecular basis of the effects of shear stress on vascular endothelial cells. J. Biomech. 2005, 38, 1949–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgoulis, V.; Adams, P.D.; Alimonti, A.; Bennett, D.C.; Bischof, O.; Bishop, C.; Campisi, J.; Collado, M.; Evangelou, K.; Ferbeyre, G.; et al. Cellular senescence: Defining a path forward. Cell 2019, 179, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revill, P.A.; Chisari, F.V.; Block, J.M.; Gehring, A.J.; Guo, H.; Cooper, S.; Locarnini, S.A. A global scientific strategy to cure hepatitis B. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlen, P.; Delloye-Bourgeois, C.; Chedotal, A. Novel roles for Slits and netrins: Axon guidance cues as anticancer targets? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, C.A.; Laimins, L.A. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: Pathways to transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Arreguín, K.; Teyra, J.; Weisburd, B.; Serra, R.W.; Yip, K.Y.; Fernandez-Zapico, M.E.; Uetz, P. HPV oncoproteins target the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex to repress tumor suppressor gene expression. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109103. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Yu, M.K.; Fong, S.; Ono, K.; Sage, E.; Demchak, B.; Sharan, R.; Ideker, T. Using deep learning to model the hierarchical structure and function of a cell. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Richon, V.M.; Ni, X.; Talpur, R.; Duvic, M. Selective inhibition of HDAC1 and HDAC2 contributes to transcriptional activation of DUX4 and apoptosis in cancer cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 1281–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Zitnik, M.; Agrawal, M.; Leskovec, J. Modeling polypharmacy side effects with graph convolutional networks. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i457–i466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglia, M.M.; Rycroft, C.H.; Glaunsinger, B.A. Transcript degradation by the herpesvirus host shutoff factor accelerates global changes in gene expression and mRNA turnover. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 559–571. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, Y. DUX4 modulates stem cell pluripotency and endows human embryonic stem cells with a higher capacity to form teratomas. Stem Cell Rep. 2020, 14, 345–358. [Google Scholar]

- Tamborero, D.; Rubio-Perez, C.; Deu-Pons, J.; Schroeder, M.P.; Vivancos, A.; Rovira, A.; Tusquets, I.; Albanell, J.; Rodon, J.; Tabernero, J.; López-Bigas, N. Cancer Genome Interpreter annotates the biological and clinical relevance of tumor alterations. Genome Med. 2018, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HPV Type | Prevalence in Tumors | Tumor Localization | Clinical Notes |

| HPV 16 | ~60% of cervical cancers~70% of oropharyngeal cancers | Cervix, oropharynx, anus, penis, vulva, vagina | Highly oncogenicPersistent infection linked to integration into the human genome |

| HPV 18 | ~10–15% of cervical cancers | Cervix, vagina, anus | Often associated with glandular carcinomas |

| HPV 31 | 2–5% | Cervix, anus, penis | Common in CIN2/CIN3 precancerous lesions |

| HPV 33 | 2–4% | Cervix, vulva | Frequent precancerous lesions |

| HPV 35 | <2% | Cervix, vagina | Detected in advanced cervical neoplasms |

| HPV 39 | <2% | Cervix, anus | Moderate oncogenic potential |

| HPV 45 | ~5% | Cervix, vagina | Strong association with adenocarcinomas |

| HPV 51 | ~1–2% | Cervix | Rare but oncogenic |

| HPV 52 | ~2–3% | Cervix, anus | Included in Gardasil 9 vaccine |

| HPV 56 | <1% | Cervix | Lower relative risk |

| HPV 58 | ~2–4% | Cervix, vulva | Common in East Asia |

| HPV 59 | <1% | Cervix | Rare but classified as high-risk |

| HPV 66 | Rarely isolated | Cervix | Often found in co-infections |

| HPV 68 | ~1% | Cervix, oropharynx | May integrate into host genome |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).