Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Chlorination: Water Disinfection Process

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Water Sampling

- Raw water was collected from the Jadro River source, which is the main surface water source in the area.

- Chlorinated water samples were taken from bathroom taps in a hotel within the county, with the taps being disinfected by flame beforehand to ensure accurate results.

2.2. Chemical and Microbiological Analyses

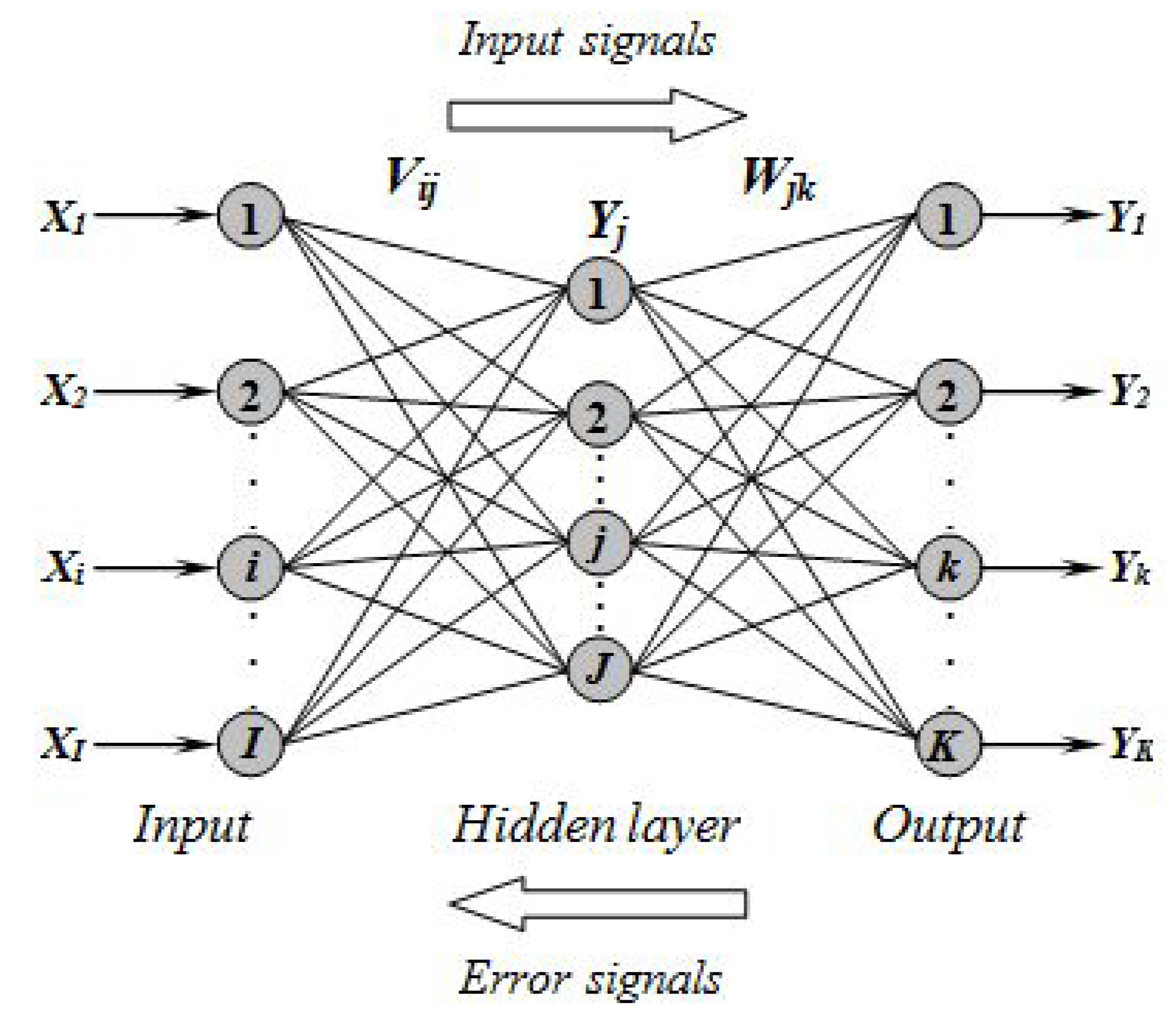

2.3. Application of Multiple Regression and the Artificial Neural Network Model

- Y - dependent variable (response),

- - independent variables (predictor),

- n - number of variables,

- - regression coefficients representing the relative predictive power of the model,

- c - constant that intersects the y-axis for the case .

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Performance function - MSE | 0.0001 |

| Learning rate | 0.01 |

| Learning rate - increase | 0.5 |

| Learning rate - decrease | 1.05 |

| Maximum performance increase | 1.04 |

| Minimum performance gradient | 1e−10 |

| Momentum | 0.9 |

| Number of layers | 3 |

| Number of neurons | 10-15-40 |

| Transfer functions | tansig-tansig-purelin |

| Training function | Levenberg-Marquardt |

| Epochs to train | 1000 |

| Training ratio | 70% |

| Test ratio | 30% |

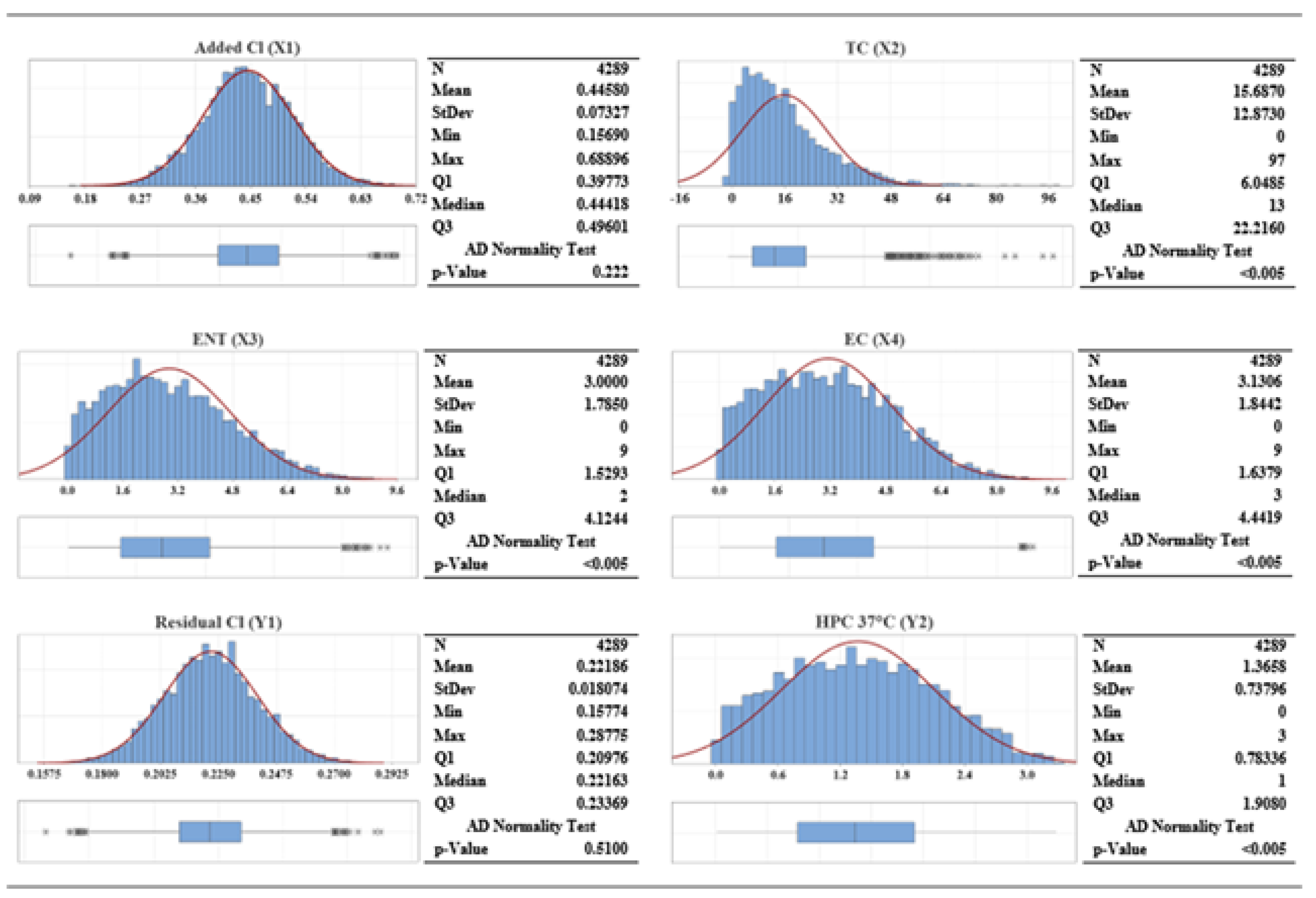

3. Experimental Data

4. Results and Discussion

| Parameter | Coef | Stan. Error | T-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONSTANT | 0.31945 | 0.00128 | 250.20 | 0.000 |

| -0.20567 | 0.00243 | -84.68 | 0.000 | |

| -0.001610 | 0.000196 | -8.22 | 0.000 | |

| -0.000339 | 0.000098 | -3.46 | 0.001 | |

| 0.000056 | 0.000029 | 1.97 | 0.049 |

| Source | Df | Sum of Sq | Mean of Sq | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 4 | 0.693818 | 0.173454 | 1855.86 | 0.000 |

| X1 | 1 | 0.670142 | 0.670142 | 7170.13 | 0.000 |

| X3 | 1 | 0.006312 | 0.006312 | 67.54 | 0.000 |

| X4 | 1 | 0.001116 | 0.001116 | 11.94 | 0.001 |

| X3*X4 | 1 | 0.000362 | 0.000362 | 3.87 | 0.049 |

| Error | 2997 | 0.280109 | 0.000093 | ||

| Total | 3001 | 0.973926 | |||

| Standard Error of Est. = 0.0096676 | |||||

| Parameter | Coef | Stan. Error | T-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONSTANT | 1.8335 | 0.044 | 41.26 | 0.000 |

| -0.1853 | 0.0127 | -14.54 | 0.000 | |

| 0.02208 | 0.00638 | 3.46 | 0.001 | |

| -0.00367 | 0.00186 | -1.97 | 0.048 |

| Source | Df | Sum of Sq | Mean of Sq | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 3 | 420.56 | 140.185 | 354.38 | 0.000 |

| X3 | 1 | 83.67 | 83.665 | 211.50 | 0.000 |

| X4 | 1 | 4.73 | 4.734 | 11.97 | 0.001 |

| X3*X4 | 1 | 1.54 | 1.542 | 3.90 | 0.048 |

| Error | 2998 | 1185.93 | 0.396 | ||

| Total | 3001 | 1606.49 | |||

| Standard Error of Est. = 0.628948 | |||||

5. Conclusions

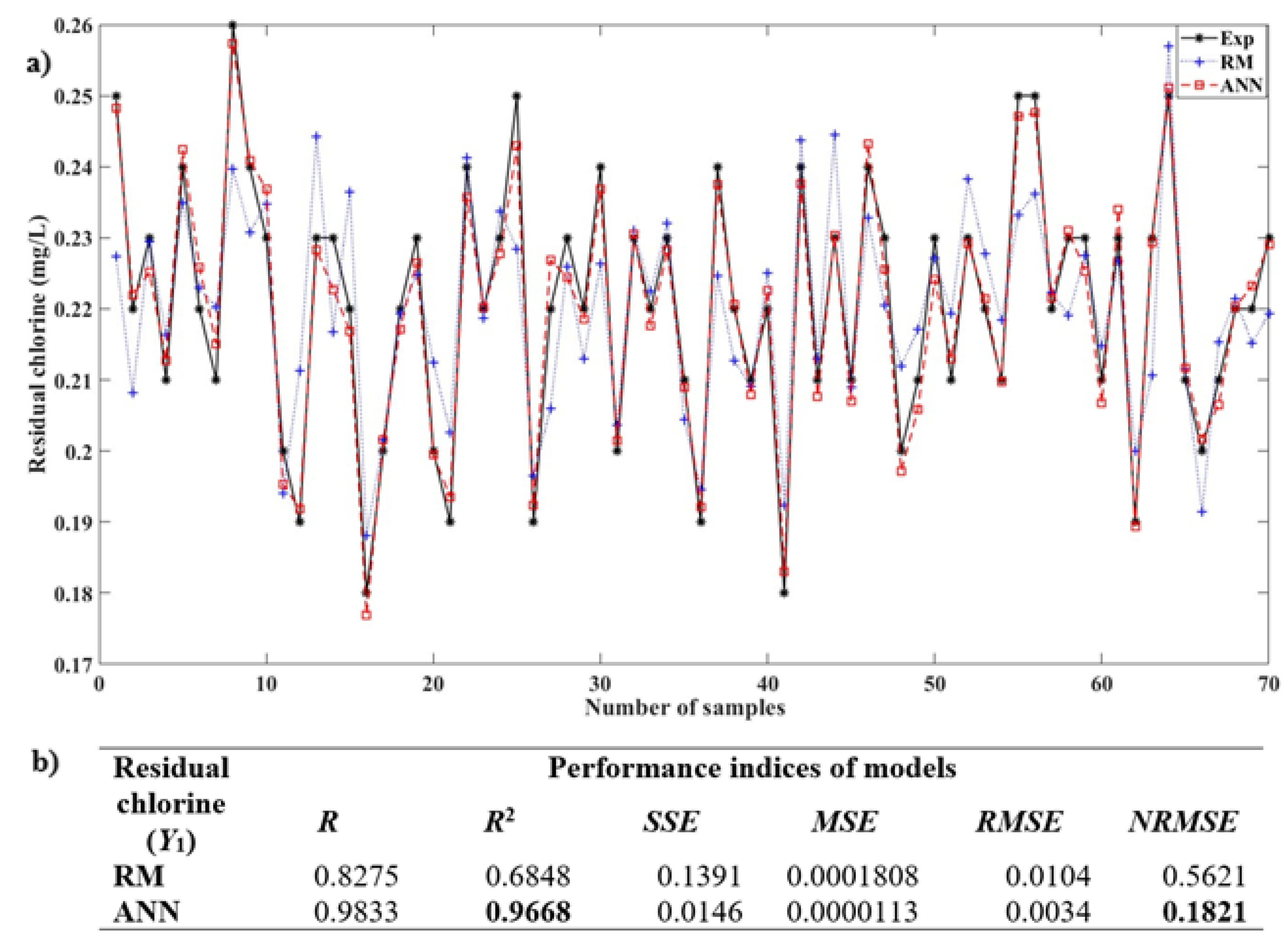

- (added chlorine): This has the largest impact, with a high regression coefficient, indicating a direct relationship between the amount of added chlorine and the residual chlorine concentration.

- (enterococci): This has a smaller but statistically significant negative impact.

- The interaction term (enterococci ×): This shows the smallest but significant positive impact.

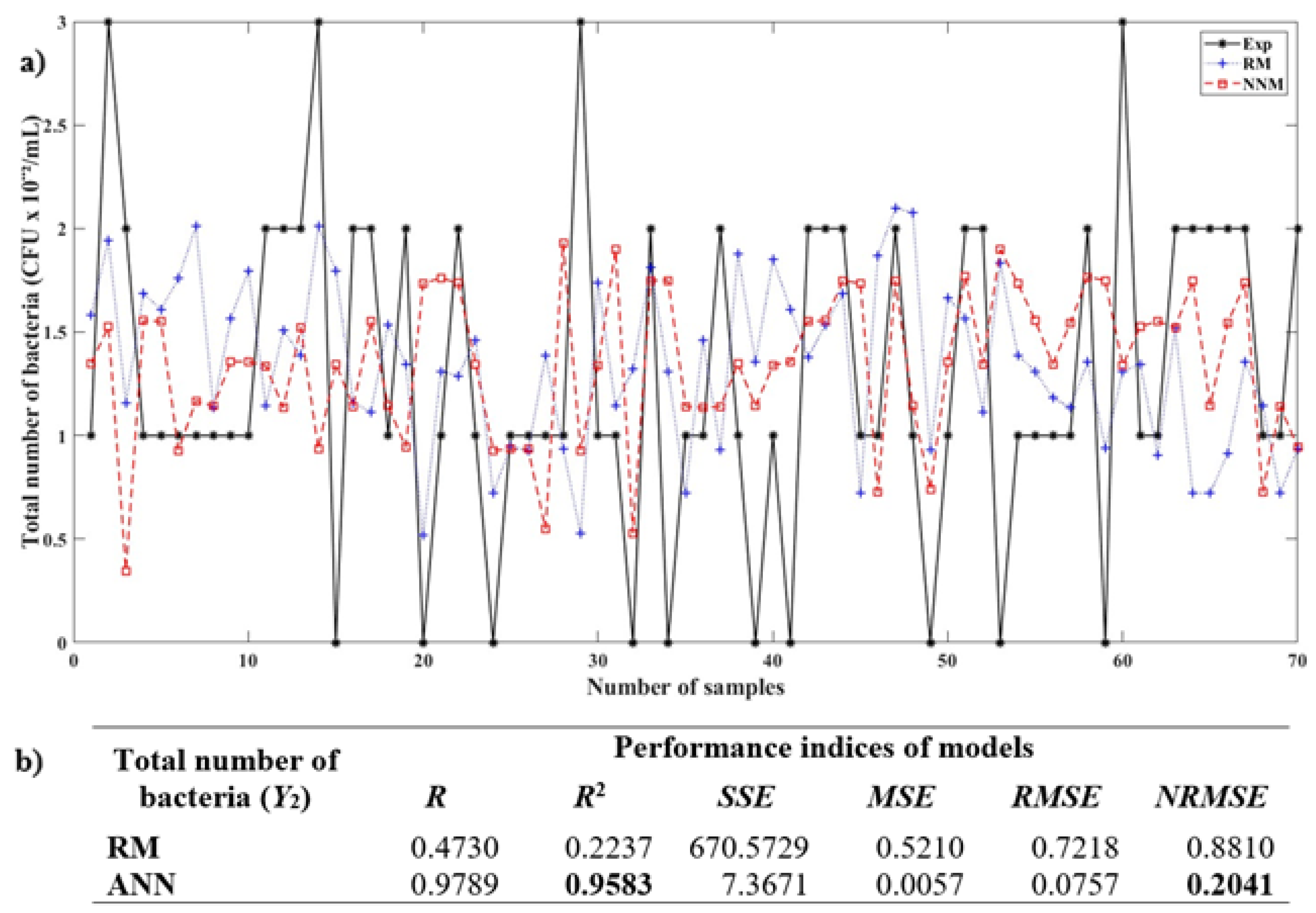

- (enterococci): This has the largest negative impact on the total bacterial count.

- (E. coli): This has a positive impact, but smaller compared to .

- The interaction term : This has a significant negative impact.

Abbreviations

| ak | Actual outputs of Eq. |

| Actual outputs (estimation) of Eqs. | |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| b1, b2, …, bn | The regression coefficients of Eq. |

| c | Constant of Eq. |

| Df | Degrees of freedom |

| dk | Desired outputs (experimental values) of Eq. |

| dn | Desired outputs (target) of Eqs. |

| E | System error. |

| Exp | Experimental. |

| I | Number of inputs of neuron j in the hidden layer of Eqs. |

| i | Number of neurons of the input layer of Eqs. |

| J | Number of inputs of neuron k in the output layer of Eqs. |

| j | Number of neurons of the hidden layer of Eqs. |

| K | Total number of patterns of Eq. |

| k | Number of neurons of the output layer of Eq. |

| lr | Learning rate of Eqs. |

| MCL | Maximum contaminant level |

| MR | Multiple regression |

| MSE | Mean square error |

| n | Current iteration step of Eqs. |

| NRMSE | Normalized Root Mean Square Error |

| N | Total number of patterns of Eqs. |

| R | Correlation coefficient |

| R2 | The square of correlation coefficients |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SSE | Sum of squared errors |

| T-Statistic | Student t distribution |

| V | Weight between the input layer and the hidden layer of Eq. |

| WDS | Water distribution systems |

| Weight between the hidden layer and the output layer of Eq. | |

| X | Independent variable |

| Added chlorine, mg/L | |

| - TC | Total coliforms, CFU×10−2/mL |

| - ENT | Intestinal enterococci, CFU×10−2/mL |

| X4 - EC | Escherichia coli, CFU×10−2/mL |

| Xi | Input signals |

| Y | Dependent variable of Eq. |

| Y1 | Residual chlorine, mg L−1 |

| Y2 - HPC | Total number of aerobic heterotrophic bacteria, CFU/mL |

| Output of the hidden neurons of Eqs. | |

| Y | Output signals |

| Momentum of Eqs. | |

| Learning errors of Eqs. | |

| Standard deviation of Eqs. |

References

- Chowdhury, S. Heterotrophic bacteria in drinking water distribution system: a review. Environ Monit Assess 2012, 184, 6087–6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHMRC. Australian Drinking Water Guidelines Paper 6 National Water Quality Management Strategy. Technical report, Canberra, 2011.

- Štambuk Giljanović, N. Water quality evaluation by index in Dalmatia. Water Res 1999, 33, 3423–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorillo, F.; Pagnozzi, M.; Addesso, R.; Cafaro, S.; D’Angeli, I.M.; Esposito, L.; Leone, G.; Liso, I.S.; Parise, M. Uncertainties in understanding groundwater flow and spring functioning in karst. In Threats to Springs in a Changing World: Science and Policies for Protection; Currell, M.J., Katz, B.G., Eds.; American Geophysical Union: Washington D.C, 2022; pp. 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Jukić, D.; Denić-Jukić, V. Investigating relationships between rainfall and karst-spring discharge by higher-order partial correlation functions. Journal of Hydrology 2015, 530, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukić, D.; Denić-Jukić, V.; Kadić, A. Temporal and spatial characterization of sediment transport through a karst aquifer by means of time series analysis. Journal of Hydrology 2022, 609, 127753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margeta, J. Water abstraction management under climate change: Jadro spring Croatia. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2022, 16, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margeta, J.; Fistanić, I. Water quality modelling of Jadro Spring. Water Sciences and Technology 2004, 50, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rađa, B.; Puljas, S. Macroinvertebrate diversity in the karst Jadro river (Croatia). Archives of Biological Sciences 2008, 60, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štambuk Giljanović, N. Vode Dalmacije; Nastavni Zavod za javno zdravstvo Splitsko-dalmatinske županije: Split, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacci, O.; Roje-Bonacci, T. Analiza oduzimanja vode iz izvora Jadra u razdoblju 2010. - 2021. Hrvatske vode 2023, 31, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, J. Water Microbiology. Bacterial Pathogens and Water. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010, 7, 3657–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutala, W.; Weber, D. Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities 2008.

- IARC. , Ed. Chlorinated drinking-water; chlorination by-products; some other halogenated compounds; cobalt and cobalt compounds; Number 52, IARC: Lyon, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Panguluri, S.; Grayman, W.; Clark, R. Water Distribution System Analysis: Field Studies, Modeling, and Management 2005.

- EC. Council Directive 98/83/EC on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption, L 330/32 ed. Official journal of the European Communities Council.

- Mansor, N.A.; Tay, K.S. Potential toxic effects of chlorination and UV/chlorination in the treatment of hydrochlorothiazide in the water. Sci Total Environ 2020, 20, 136745–136745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Koo, J. Prediction of Chlorine Concentration in Various Hydraulic Conditions for a Pilot Scale Water Distribution System. Procedia Eng 2014, 70, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U. (Eds.) Biofilm highlights; Springer series on biofilms, Springer: Heidelberg ; New York, 2011. OCLC: ocn729346877.

- Moritz, M.M.; Flemming, H.C.; Wingender, J. Integration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Legionella pneumophila in drinking water biofilms grown on domestic plumbing materials. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2010, 213, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimpenny, J.; Manz, W.; Szewzyk, U. Heterogeneity in biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2000, 24, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legay, C.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Sérodes, J.B.; Levallois, P. The assessment of population exposure to chlorination by-products: a study on the influence of the water distribution system. Environ Health 2010, 9, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legay, C.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Sadiq, R.; Sérodes, J.B.; Levallois, P.; Proulx, F. Spatial variations of human health risk associated with exposure to chlorination by-products occurring in drinking water. J Environ Manage 2011, 92, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Fu, J.; Xie, Y.F. Formation of disinfection by-products: effect of temperature and kinetic modeling. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, V.; Pirnie, M. Distribution Systems: The Next Frontier. The Bridge, National Academy of Engineering 2008, 38, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli, C.; Courtois, S.; Rosikiewicz, M.; Piriou, P.; Aeby, S.; Robert, S.; Loret, J.F.; Greub, G. Reduced Chlorine in Drinking Water Distribution Systems Impacts Bacterial Biodiversity in Biofilms. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefisoye, M.A.; Olaniran, A.O. Does Chlorination Promote Antimicrobial Resistance in Waterborne Pathogens? Mechanistic Insight into Co-Resistance and Its Implication for Public Health. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordinances on compliance parameters, methods of analysis and monitoring of water intended for human consumption. Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia 64/2023, 2023.

- García-Ávila, F.; Avilés-Añazco, A.; Ordoñez-Jara, J.; Guanuchi-Quezada, C.; Flores del Pino, L.; Ramos-Fernández, L. Modeling of residual chlorine in a drinking water network in times of pandemic of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Sustainable Environment Research 2021, 31, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, I.; Kastl, G.; Sathasivan, A. A suitable model of combined effects of temperature and initial condition on chlorine bulk decay in water distribution systems. Water Res 2012, 46, 3293–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Huang, C.; Shi, X.; Dong, S.; Yuan, B.; Nguyen, T.H. Role of drinking water biofilms on residual chlorine decay and trihalomethane formation: An experimental and modeling study. Sci Total Environ 2018, 642, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland. Water Quality - Sampling for Microbiological Analysis, 2006.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland. Water quality - Enumeration of culturable micro-organisms - Colony count by inoculation in a nutrient agar culture medium, 1999.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland. Water quality – Enumeration of Escherichia coli and coliform bacteria – Part 1: Membrane filtration method for waters with low bacterial background flora, 2017. ISO 9308-1:2014/Amd 1:2016; EN ISO 9308-1:2014/A1:2017.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO), Geneva, Switzerland. Water quality - Detection and enumeration of intestinal enterococci - Part 2: Membrane filtration method, 2000.

- Glavaš, Z.; Lisjak, D.; Unkić, F. The Application of Artificial Neural Network in the Prediction of the As-cast Impact Toughness of Spheroidal Graphite Cast Iron. Kovové Materiály 2007, 45, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cosic, P.; Lisjak, D.; Antolic, D. Regression analysis and neural networks as methods for production time estimation. Technical Gazette 2011, 18, 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Lisjak, D.; Maric, G.; Štefanić, N. Studying the possibility of neural network application in the diagnostics of a small four-stroke petrol engine by wear particle content. Technical Gazette 2012, 19, 857–862. [Google Scholar]

- Živko Babić, J.; Lisjak, D.; Ćurković, L.; Jakovac, M. Estimation of chemical resistance of dental ceramics by neural network. Dent Mater 2008, 24, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löschel, A. Technological change in economic models of environmental policy. Ecol Econ 2002, 43, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J. Interpretation of concrete dam behaviour with artificial neural network and multiple linear regression models. Eng Struct 2011, 33, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.S.; Šoštarić, T.D.; Pezo, L.L. Usefulness of ANN-based model for copper removal from aqueous solutions using agro industrial waste materials. Chem Ind Chem Eng Q 2015, 21, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kang, S.; Li, F. Simulation of artificial neural network model for trunk stem flowof Pyrus pyrifolia and its comparison with multiple-linear regression. Agric Water Manage 2009, 96, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, G.J.; Nixon, J.B.; Dandy, G.C.; Maier, H.R.; Holmes, M. Forecasting chlorine residuals in a water distribution system using a general regression neural network. Math Comput Model 2006, 44, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.J.; Sérodes, J.B. Assessing empirical linear and non-linear modelling of residual chlorine in urban drinking water systems. Environ Model Softw 1999, 14, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.P.; Gupta, S. Artificial intelligence based modeling for predicting the disinfection by-products in water. Chemom Intell Lab Syst 2012, 114, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).