1. Introduction

Robots are revolutionizing agriculture by addressing labor shortages, automating repetitive tasks, and enhancing safety. By integrating robots into agricultural systems, we are reshaping the industry and also unlocking transformative potential in precision agriculture to ensure food security, resource management, and environmental sustainability [

1,

2]. Additionally, the challenging conditions of agricultural environments, combined with increasing demands for high-quality production, make robotic technologies a timely and necessary solution [

3,

4,

5]. An indicator of this technological growth and importance is the global agricultural robotics market, which was valued at approximately USD 14.74 billion in 2024, and it is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 23% from 2025 to 2030 [

6].

In a recent review, advancements in agricultural robots specifically targeting specialty crops were identified [

7]. The findings revealed significant interest in robot solutions for harvesting, along with emerging relevance in tasks such as spraying, pruning, weed control, pollination, transplanting, and fertilizing. These efforts emphasize the importance of robotic technologies and their problem-solving capabilities. More notably, the review highlighted the importance of collaborative robotics (co-robotics), where robots do not necessarily perform tasks solely, but often in collaboration with humans or other technologies [

7]. The integration of such systems leverages the strengths of each platform, facilitating the execution of tasks that exceed the capabilities of either system independently [

8,

9]. Certainly, activities that require high levels of precision and adaptability, as well as considerations such as safety and ergonomics, are key areas of focus for co-robotics [

10,

11]. For instance, Fei and Vougioukas [

12] developed a robotic platform to dynamically control worker positioning and travel speed in real time during harvesting operations. Their system uses an algorithm that adjusts these parameters based on inputs such as the distribution of incoming fruit loads and the workers’ fruit-picking rates. The algorithm selects the highest possible speed that still ensures the fruit-picking percentage remains above a grower-defined minimum threshold. This approach increased harvesting throughput by up to 25%. Another study by Koc and Vatandas [

13] introduced an autonomous robot designed to optimize fruit transportation logistics in agricultural environments. The system was built on the Robot Operating System (ROS) and featured an enhanced hybrid navigation system for precise localization. It integrated high-resolution LiDAR for environmental mapping, an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) for motion estimation, and wheel encoders for odometry. The robot was tested across various terrain types to ensure robust performance and validate its effectiveness.

Delving deeper into co-robotics, we could find recent studies exploring collaborative systems involving both robots and drones. For instance, a study by Manasherov and Degani [

14] introduced a co-robotic system comprising a ground-based robotic platform and multiple drones for artificial pollination. The platform was equipped with a single sensor to detect flower positions and deployed several drones accordingly. An algorithm assigned each drone a sequence of target flowers and planned safe trajectories to enable effective pollination via aerial deployment. In another study, Mansur et al. [

15] utilized drones to generate navigation maps for agricultural robots operating in row crops, particularly soybeans. This approach demonstrated the potential of integrating drones with ground robots in precision agriculture tasks, such as site-specific application of fertilizers or pesticides using small autonomous machines. Notably, these studies underscore the growing importance of both robots and drones in modern agriculture and, more significantly, the value of their collaboration. While drones are already a well-established technology in the agricultural sector, primarily used for remote sensing [

16], they have recently emerged as effective platforms for spraying applications [

17].

Spraying drones present a promising solution to many challenges associated with conventional manual and machinery-based application methods [

18]. These include reducing human exposure to chemicals [

19], enabling low-volume application [

20], accessing difficult or uneven terrain [

21], and increasing efficiency [

22]. However, despite their advantages, several operational concerns remain, particularly regarding field support requirements. Typically, a field team is needed to set up the drone and, more critically, to prepare the application mixture, which is a labor-intensive, time-consuming, and susceptible to error task. Commercially, trailer-based systems are available to carry spraying components such as water tanks, mixers, chemicals, and pumps to prepare the application mixture. However, they are generally unsuitable for family-owned or small farms with smaller areas due to their high cost and scale, making the overall operation less viable. Additionally, it adds complexity for the end user to lead with non-user-friendly platforms.

Considering the importance of spraying drones and the collaborative potential of robotic systems, our objectives were to design and implement a robotic system to support spraying drone operations, focusing on small farms and research field support. To provide a clearer understanding of our approach, the following sections detail our methodological framework (

Section 2). This section includes the robotic system architecture, platform components, programming and control interface, and the parameters used to evaluate the system’s effectiveness. We then present the results of the performance assessment (

Section 3) and conclude with final remarks (

Section 4).

2. System’s Framework

2.1. Robotic Platform

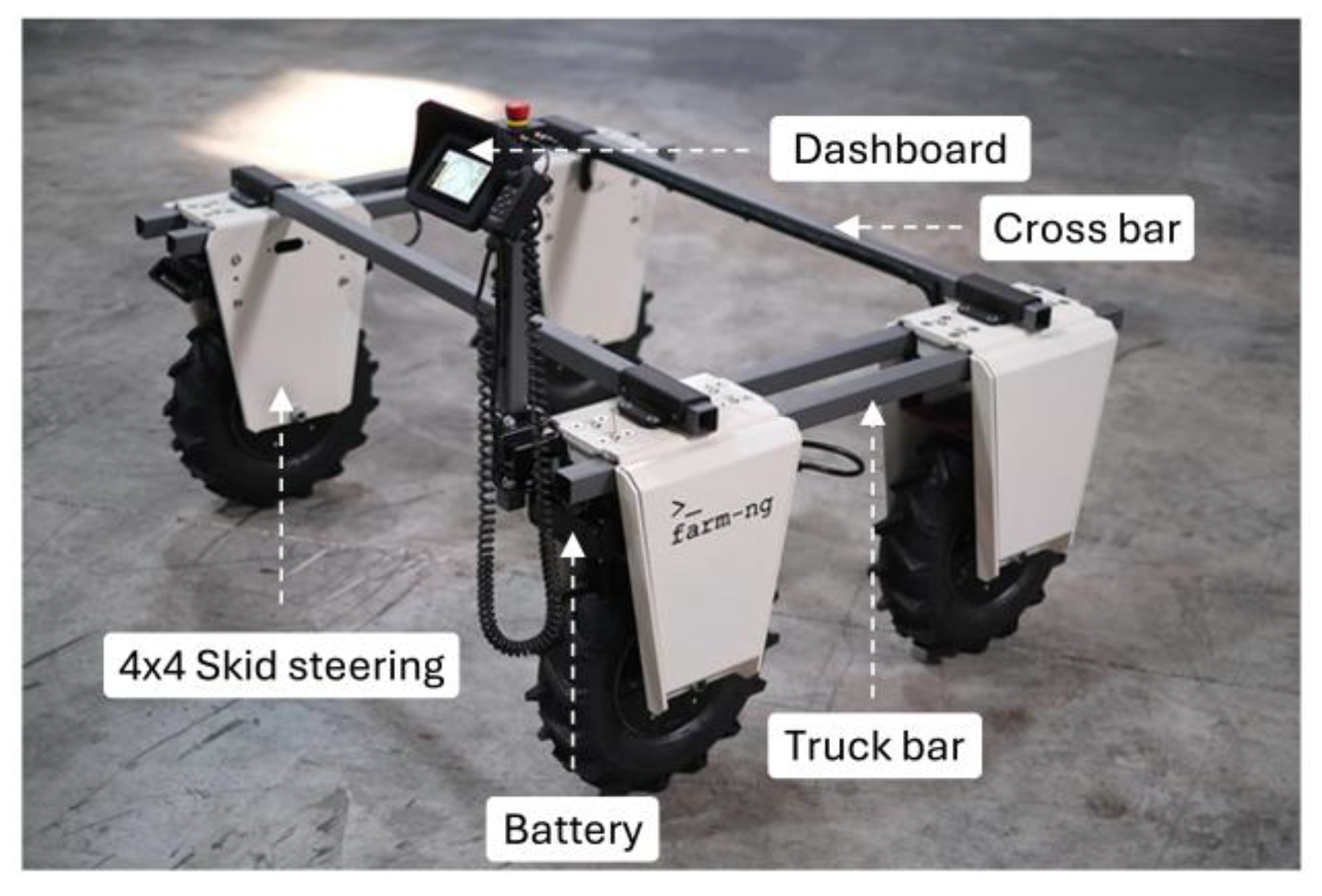

A ground robot (Farm-ng Amiga, Watsonville, California, USA) was the platform deployed for this study (

Figure 1). It is a 4x4 all-electric skid-steer vehicle powered by a 1.32 kWh dual battery pack, guaranteeing approximately 3 hours of operating time. The robot’s load capacity includes hauling up to 430 kg, towing up to 900 kg, lifting up to 360 kg (with a 3-point lift kit), and reaching speeds of up to 8 km/h. Additionally, it is composed of crossbars and truckbars that are fully adjustable to the desired wheel track width. For this specific study, the robot was configured to a width of 0.80 m and a length of 1.13 m. It served as the base vehicle, with all components subsequently installed on it. The robot is operated via a pendant controller, and settings are accessed via a touchscreen dashboard display.

2.2. Components of the System

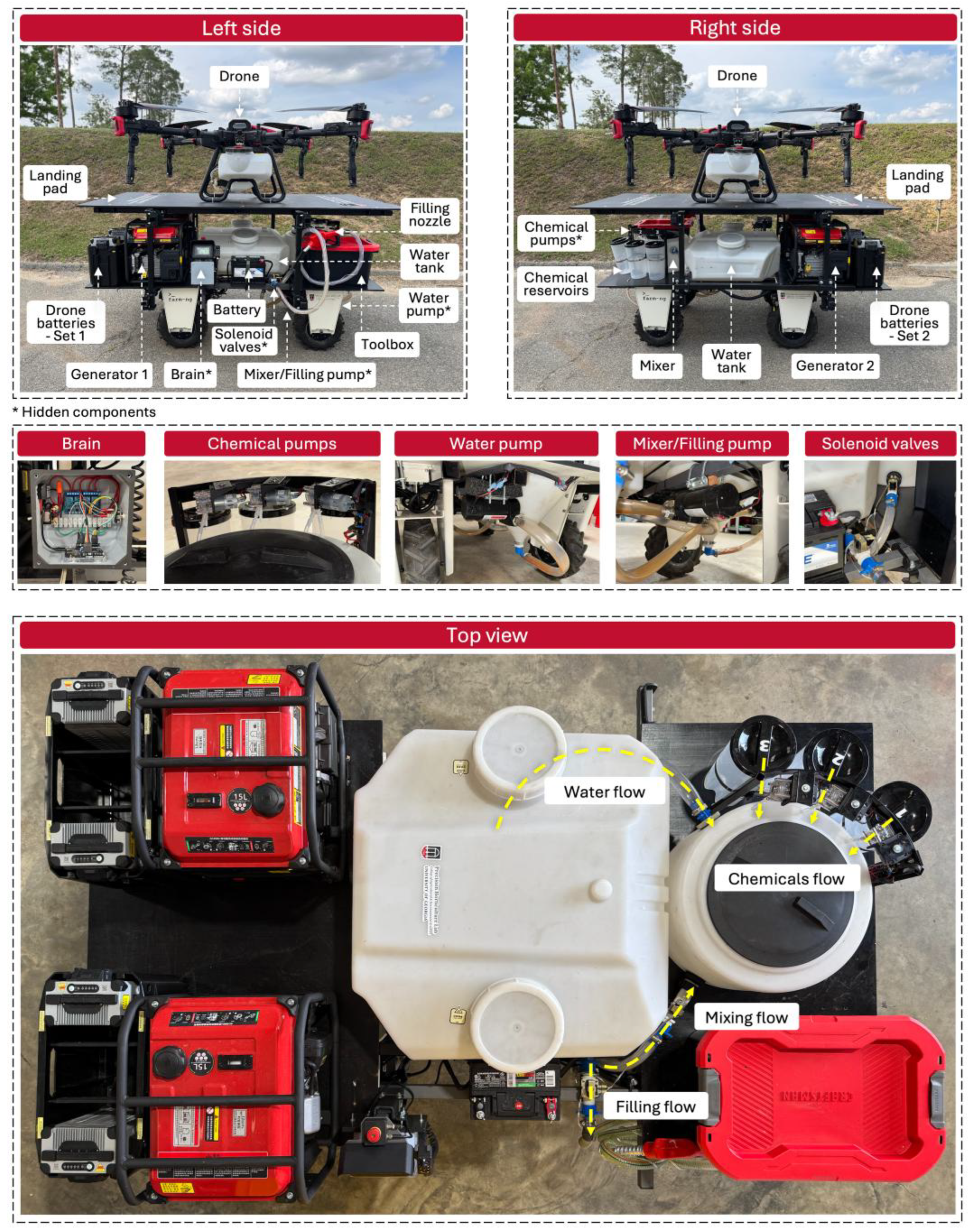

The main components included a 150-L water tank, three 3.5-L chemical reservoirs, a 60-L mixing tank, two generators for drone battery charging, and a top landing pad (

Figure 2). In this system, independent pumps were designated to deliver water and chemicals to the mixing tank. Considering the low-volume application, low-pressure, and repeatable chemical dispensing, we used peristaltic pumps for dispensing chemicals, ensuring precision and accuracy. Chemical pumps achieve a nominal flow of approximately 500 mL/min. Conversely, the pumps for the water supply and the mixer/filling process need to operate at higher volumes to ensure a faster process. Therefore, for the water supply, we used higher-pressure pumps with a nominal flow of approximately 50 L/min. The pump designated for the mixer tank was implemented to extract the application mixture through suction and recirculate it back into the mixer tank via a tank agitator device installed in the mixing tank. This system was also integrated into the drone filling process using a solenoid valve system. When the agitation is running, a solenoid valve is normally open, allowing the application mixture to recirculate to the mixing tank. A momentary push button was installed in the filling nozzle trigger; when the trigger is pressed, the solenoid valve system closes the solenoid of the mixing process and opens another solenoid valve, delivering the application mixture to the drone’s tank through the hose. To start the mixer/filling process, we installed a toggle button for customized and rapid action according to the user’s needs.

2.3. Programming and Control Interface

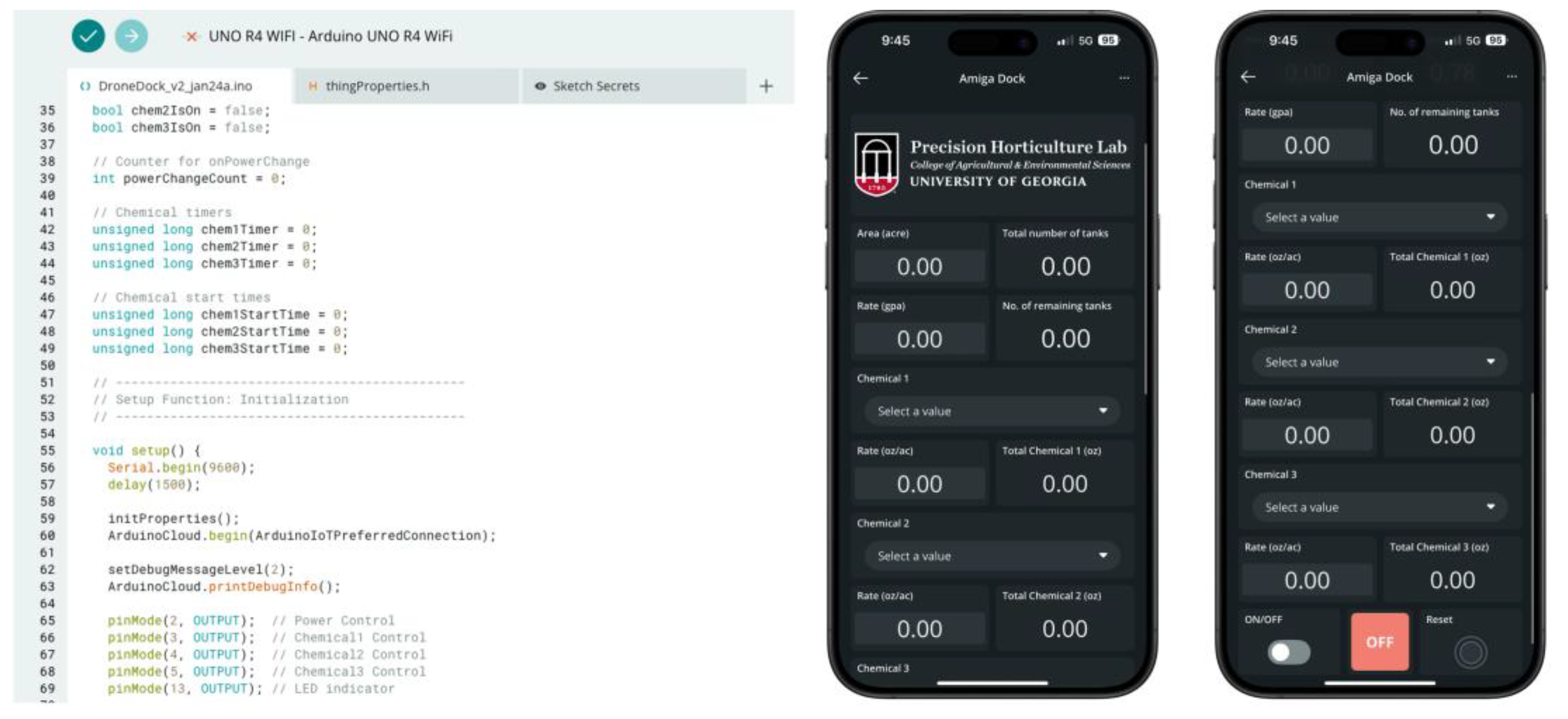

Water and chemical pumps were automatically controlled using a microcontroller (Arduino UNO R4 WIFI). In addition to the microcontroller, Arduino technology includes a cloud programming interface (

https://app.arduino.cc), allowing for dashboard creation and full control through a mobile app (IoT Remote). Initially, we developed a programming code to perform all the desired steps (

Figure 3, left). This code determines all the input and output signals the microcontroller needs to handle. Subsequently, we created a mobile app to transform the process into a user-friendly platform (

Figure 3, right). Through the app, the user only needs to fill in the boxes with information such as “Area (acre)”, “Rate (GPA)”, and up to three chemicals (“Chemical 1”, “Chemical 2”, and “Chemical 3”). Additionally, we implemented a list of illustrative examples of pre-saved chemicals to facilitate further suggested chemical doses. As a result, this system automatically calculates the “Total number of tanks” needed to execute the spraying task in the specific field, and the “Total Chemicals” needed for each active ingredient in the field. To initiate the application mixture preparation, the user only needs to press the “ON/OFF” button to turn the system on. Similarly, when needed, the user can also interrupt the operation by clicking the button again to turn it off. As the application progresses, the mobile app continuously updates the user on the “Number of remaining tanks”. The mobile app also contains a “Reset” button to restart the system and clear previous input information. To complement the description and better illustrate the system in operation, a supplementary video is provided (Video S1).

2.4. Analysis of the System’s Effectiveness

Before evaluating the system’s effectiveness, we meticulously calibrated the pumps by conducting detailed measurements of the time required to deliver varying amounts of both water and chemicals. For safety and consistency in this initial study, only water was used in the chemical reservoirs. As a result, the water pump exhibited a real flow rate of approximately 27 L/min, while the chemical pumps operated at around 420 mL/min. Following calibration, we employed evaluation metrics to assess both the precision and accuracy of the robotic system. Precision was quantified using the standard deviation (SD) and the coefficient of determination (R2), while accuracy was evaluated through the mean absolute error (MAE) for water and chemical dosages. These metrics enabled us to quantify the system’s consistency and reliability in delivering the target application rates. To perform this evaluation, we programmed six different application rates and chemical dosages into the mobile app for delivery into the mixer tank. The water pump was tested with volumes of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 L, while the chemical pumps were tested with dosages of 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, and 600 mL. Each application rate and dosage was measured five times to ensure statistical robustness.

In addition to dosage analysis, we conducted a comparative study on time efficiency, focusing on two key processes:

- (i)

chemical rate calculation using the conventional manual method versus the robotic system via the mobile app.

- (ii)

chemical dosing using traditional tools (e.g., graduated cylinder) compared to the automated robotic system. To ensure consistency and reduce bias, five independent and experienced individuals were assigned to perform the manual calculations and measurements.

3. Performance Assessment

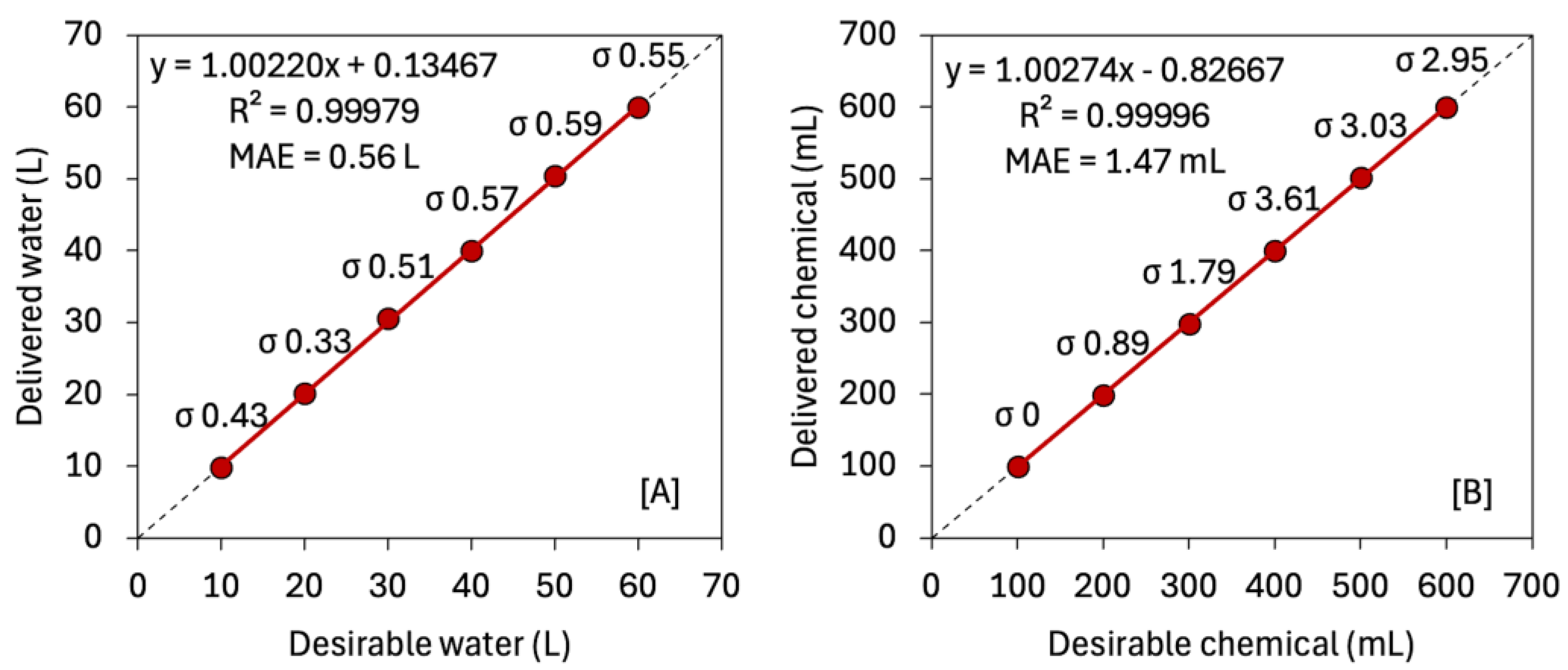

The results of the robotic system demonstrated high performance in delivering the desired amount of water and chemicals into the mixing tank (

Figure 4). When delivering water, the system proved to be both precise (R

2 > 0.99; SD = 0.33–0.59 L) and accurate (MAE = 0.21 L) (

Figure 4A). Overall, water delivery was consistent across all the application rates. When delivering chemicals, the system also showed high effectiveness, with R

2 > 0.99, SD < 3.61, and MAE = 0.93 mL (

Figure 4B). Notably, the chemical pumps exhibited a trend of increasing variability at higher dosage levels. However, this increased variation remained below 1%.

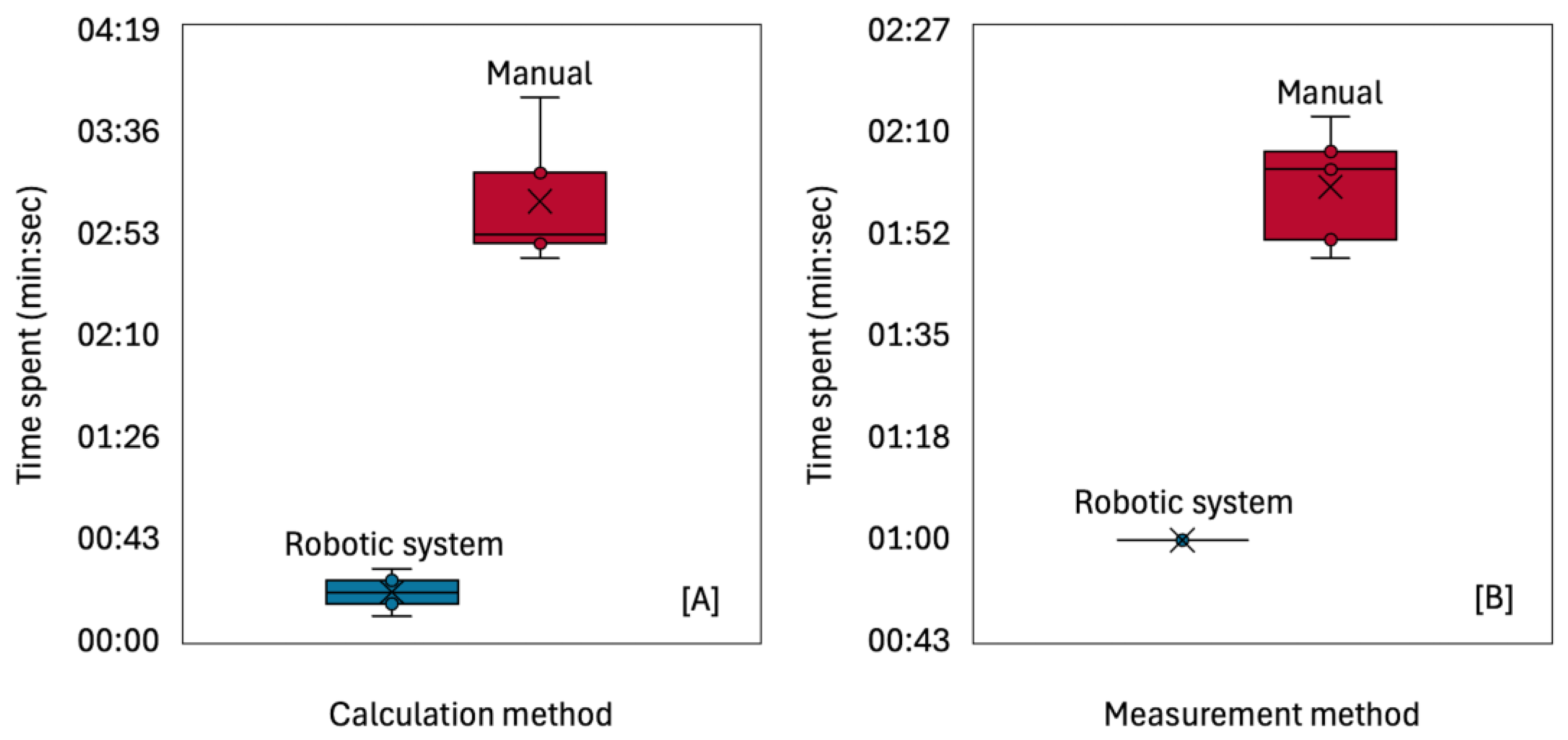

Regarding the time required to calculate and measure chemical dosages, the robotic system was, on average, 9.3 times faster than manual calculation (

Figure 5A). For example, calculating the chemical dosage for a specific field manually took an average of 3 minutes. In contrast, using the mobile app, results were generated instantly, with the only time required being the user’s input, which averaged only 20 seconds. Additionally, the robotic system also outperformed manual methods in measuring and delivering chemical dosages (

Figure 5B). In a test involving the measurement of 420 mL using the chemical pumps, the robotic system completed the task twice as fast as manual measurement.

4. Final Remarks and Conclusions

In this study, we designed and implemented an automatic mixing and refiling platform mounted on a robotic system to support spraying drone applications. The system integrates hardware and software components to automate several critical steps in the spraying process. Such steps involve transporting the drone along with all necessary spraying components, preparing the application mixture, and serving as a platform for drone takeoff and landing directly on it. This collaborative approach demonstrates how ground-based robotic platforms can extend the functionality and operational efficiency of aerial spraying drones. To the best of our knowledge, this represents a novel approach and a pioneering solution aimed at supporting small farms and experimental research fields, for whom large-scale commercial field systems are often financially and logistically inaccessible.

Small farms represent a substantial portion of global food producers, yet they frequently lack access to advanced agricultural technologies [

1,

23]. By combining mobility, automation, and user-friendly control via a mobile app, our system supports small farms owners to improve productivity and safety, while contributing to broader goals of food security, economic resilience, and sustainable land management. Mobile-app-based solutions are increasingly being developed and recommended as effective tools to facilitate technology adoption among farmers [

24,

25,

26]. In our study, for instance, the mobile app serves as an in-pocket solution that allows users to easily configure spraying parameters. Overall, our system supports field-level precision agriculture without demanding extensive technical expertise from the operator. Moreover, this development introduces these technologies within a co-robotic concept. It serves as a valuable asset for agricultural tasks and has been highlighted as a direction to facilitate robot adoption, primarily by significantly reducing labor [

7] and improving overall efficiency [

12,

14].

Our results demonstrated that the robotic system accurately and precisely delivered the desired amount of water and chemicals into the mixing tank, eliminating the need for human intervention and minimizing subjectivity. Furthermore, the system outperformed traditional manual methods in terms of speed. More importantly, the system presents potential social, environmental, and economic impacts. Socially, it can reduce human exposure to hazardous chemicals, particularly during the measurement and mixing automatic process, steps identified as primary sources of chemical exposure [

27]. Environmentally, it minimizes chemical waste and contamination, supports cleaner disposal practices, and contributes to sustainable chemical use. Economically, it potentially lowers costs from chemical overuse and waste, increases operational efficiency and precision, and reduces expenses related to health and environmental impacts. All these impacts are aligned with the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Endangered Species Act and Pollinator Protection Actions.

To further enhance automation, future studies will incorporate a robotic arm to automate the drone filling and refilling process. This addition will complete the automation loop and also eliminate the need for human involvement in these tasks, thereby increasing safety and operational efficiency. Additionally, a built-in display on the platform will provide an alternative interface to the mobile app, increasing accessibility for users in the field. Ultimately, the system is envisioned to become fully autonomous, capable of navigating the field and coordinating directly with the drone to optimize mission planning and battery management. Certainly, this step will require further communication and coordination between the collaboration robot-drone [

28].

In conclusion, this study represents a substantial contribution to the advancement of agricultural robotics by demonstrating a practical, low-cost, and collaborative platform. It opens new possibilities for efficient and safe spraying operations, particularly in small-scale and research farming environments, and lays the groundwork for future developments in co-robotic systems designed to meet the evolving challenges of precision agriculture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1; Total cost of the robotic system. Video S1: field demonstration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.B.J., R.G.d.S., L.d.A.S., J.V.d.S.M., J.G.d.S., and L.P.d.O.; methodology, M.R.B.J., R.G.d.S., L.d.A.S., J.V.d.S.M., J.G.d.S., and L.P.d.O.; software, M.R.B.J.; validation, M.R.B.J., R.G.d.S., L.d.A.S., J.V.d.S.M. and L.P.d.O.; formal analysis, M.R.B.J., R.G.d.S., L.d.A.S., J.V.d.S.M. and L.P.d.O.; investigation, M.R.B.J., R.G.d.S., L.d.A.S., J.V.d.S.M. and L.P.d.O.; resources, L.P.d.O.; data curation, M.R.B.J; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.B.J. writing—review and editing, M.R.B.J., R.G.d.S., L.d.A.S., J.V.d.S.M. and L.P.d.O.; visualization, M.R.B.J., R.G.d.S., L.d.A.S., J.V.d.S.M., J.G.d.S., and L.P.d.O.; supervision, L.P.d.O. and M.R.B.J.; project administration, M.R.B.J. and L.P.d.O.; funding acquisition, L.P.d.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Precision Horticulture Laboratory of the Department of Horticulture at the University of Georgia (UGA). The infrastructural support provided by this institution was instrumental in facilitating the construction of the platform, data collection, analysis, and visualization processes involved in this study. Especially, we acknowledge the efforts of En’ya Touzé and Mateus Naciben. Additionally, we would like to thank Jeff Clack (Bestway Ag Drones), Sebastião Neto (MagnoJet), and the Farm Robotics Challenge for supporting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAGR |

Compound Annual Growth Rate |

| Co-robotics |

Collaborative Robotics |

| ROS |

Robot Operating System |

| IMU |

Inertial Measurement Unit |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| R2

|

Coefficient of Determination |

| MAE |

Mean Absolute Error |

| UN |

United Nations |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

References

- Barbosa Júnior, M.R.; Moreira, B.R. de A.; Carreira, V. dos S.; Brito Filho, A.L. de; Trentin, C.; Souza, F.L.P. de; Tedesco, D.; Setiyono, T.; Flores, J.P.; Ampatzidis, Y.; et al. Precision Agriculture in the United States: A Comprehensive Meta-Review Inspiring Further Research, Innovation, and Adoption. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221, 108993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiafe, E.K.; Betitame, K.; Ram, B.G.; Sun, X. Technical Study on the Efficiency and Models of Weed Control Methods Using Unmanned Ground Vehicles: A Review. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2025, 15, 622–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Fu, J.; Su, H.; Ren, L. Recent Advancements in Agriculture Robots: Benefits and Challenges. Machines 2023, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licardo, J.T.; Domjan, M.; Orehovački, T. Intelligent Robotics—A Systematic Review of Emerging Technologies and Trends. Electronics 2024, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.F.P.; Moreira, A.P.; Silva, M.F. Advances in Agriculture Robotics: A State-of-the-Art Review and Challenges Ahead. Robotics 2021, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research Agricultural Robots Market Size & Trends Available online:. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/agricultural-robots-market# (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Barbosa Júnior, M.R.; Santos, R.G. dos; Sales, L. de A.; Oliveira, L.P. de Advancements in Agricultural Ground Robots for Specialty Crops: An Overview of Innovations, Challenges, and Prospects. Plants 2024, 13, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munasinghe, I.; Perera, A.; Deo, R.C. A Comprehensive Review of UAV-UGV Collaboration: Advancements and Challenges. J. Sens. Actuator Networks 2024, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zheng, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, T.; Xie, P.; Xu, Y.; Deng, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, M.; Jiao, W. Integrating UAV, UGV and UAV-UGV Collaboration in Future Industrialized Agriculture: Analysis, Opportunities and Challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantoni, L.; Favilla, M.; Fraboni, F.; Mazzoni, E.; Morandini, S.; Benvenuti, M.; De Angelis, M. Integrating Collaborative Robots in Manufacturing, Logistics, and Agriculture: Expert Perspectives on Technical, Safety, and Human Factors. Front. Robot. AI 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytridis, C.; Kaburlasos, V.G.; Pachidis, T.; Manios, M.; Vrochidou, E.; Kalampokas, T.; Chatzistamatis, S. An Overview of Cooperative Robotics in Agriculture. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Z.; Vougioukas, S.G. A Robotic Orchard Platform Increases Harvest Throughput by Controlling Worker Vertical Positioning and Platform Speed. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdan Koc, D.; Vatandas, M. Development and Performance Analysis of an Autonomous Agricultural Vehicle for Fruit Transportation. J. F. Robot. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasherov, O.; Degani, A. Multi-Agent Target Allocation and Safe Trajectory Planning for Artificial Pollination Tasks. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, H.; Gadhwal, M.; Abon, J.E.; Flippo, D. Mapping for Autonomous Navigation of Agricultural Robots Through Crop Rows Using UAV. Agriculture 2025, 15, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aierken, N.; Yang, B.; Li, Y.; Jiang, P.; Pan, G.; Li, S. A Review of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Based Remote Sensing and Machine Learning for Cotton Crop Growth Monitoring. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, S.K.; Padhiary, M.; Sethi, L.N.; Kumar, A.; Saikia, P. Precision Farming with Drone Sprayers: A Review of Auto Navigation and Vision-Based Optimization. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 50, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrooz, M.; Talaeizadeh, A.; Alasty, A. Agricultural Spraying Drones: Advantages and Disadvantages. In Proceedings of the 2020 Virtual Symposium in Plant Omics Sciences (OMICAS); IEEE, November 23 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Chen, J.; Chang, Y.; Lin, S.; Chen, S.; Hung, Y. Assessing the Effectiveness of Mitigating Pesticide-related Disease Risk among Pesticide-spraying Drone Operators in Taiwan. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2024, 67, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, T.; Kamio, S. Control Efficacy of UAV-Based Ultra-Low-Volume Application of Pesticide in Chestnut Orchards. Plants 2023, 12, 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezić, A.; Trudić, B.; Stamenković, Z.; Kuzmanović, B.; Perić, S.; Ivošević, B.; Buđen, M.; Petrović, K. Drone-Related Agrotechnologies for Precise Plant Protection in Western Balkans: Applications, Possibilities, and Legal Framework Limitations. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, F.L. de L.; Santos, R.F.; Herrera, J.L.; Araújo, A.L. de; Johann, J.A.; Gurgacz, F.; Siqueira, J.A.C.; Prior, M. Use of Drones in Herbicide Spot Spraying: A Systematic Review. Adv. Weed Sci. 2023, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowder, S.K.; Sánchez, M. V.; Bertini, R. Which Farms Feed the World and Has Farmland Become More Concentrated? World Dev. 2021, 142, 105455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banday, R.U.Z.; Muzamil, M.; Dixit, J.; Gul, D.; Tak, S.A.; Sharma, M.K.; Rasool, S. Development and Evaluation of Mobile-App Controlled Self-Propelled Sensor-Integrated Rover for Site Specific Fertility Monitoring. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. A 2025, 106, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteyo, I.N.; Marra, M.; Kimani, S.; Meuter, W. De; Boix, E.G. A Survey on Mobile Applications for Smart Agriculture. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa Júnior, M.R.; Santos, R.G. dos; Sales, L. de A.; Vargas, R.B.S.; Deltsidis, A.; Oliveira, L.P. de Image-Based and ML-Driven Analysis for Assessing Blueberry Fruit Quality. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felkers, E.; Kuster, C.J.; Hamacher, G.; Anft, T.; Kohler, M. Pesticide Exposure of Operators during Mixing and Loading a Drone: Towards a Stratified Exposure Assessment. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentati, A.I.; Fourati, L.C. Comprehensive Survey of UAVs Communication Networks. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2020, 72, 103451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, met hods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).