1. Introduction

Vector-borne diseases pose a significant burden on global health. More than 80% of the world's population lives in regions where at least one vector-borne disease is endemic. Prominent examples of vector-borne diseases include malaria, dengue, lymphatic filariasis, schistosomiasis, chikungunya, onchocerciasis, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, Zika virus disease, yellow fever, and Japanese encephalitis [

1].

Arboviruses are a subset of vector-borne diseases, caused by viral pathogens transmitted by arthropod vectors to vertebrate hosts. These viruses belong to diverse taxonomic families, including

Togaviridae,

Flaviviridae,

Peribunyaviridae,

Rhabdoviridae, of the order

Reovirales [

2]. Hematophagous arthropods such as mosquitoes, ticks, sand flies, and midges are vectors of several arboviruses, which can be transmitted to susceptible vertebrate hosts and cause diseases. Arboviral diseases are acute febrile illnesses with a wide range of clinical manifestations, from mild fever to severe complications such as neurological disorders, shock, congenital anomalies, and hemorrhagic fever. Fatal outcomes are not uncommon [

3]. These diseases pose a significant global health challenge, with dengue alone accounting for an estimated annual economic burden of US

$ 8.9 billion [

4]. The lack of effective vaccines and specific antiviral treatments highlights the critical importance of robust surveillance and vector control strategies as the primary tools for preventing and mitigating arboviruses outbreaks [

3,

5].

Despite the implementation of control measures in numerous countries, the desired outcomes have often fallen short [

1]. This shortfall is largely due to the lack of comprehensive policies that account for the territorial, demographic, and ecological factors shaping host-pathogen-vector interactions [

1,

6]. Furthermore, gaps in understanding the biology, diversity, and ecological dynamics of vector species undermine predictive modeling efforts and complicate the design and implementation of effective control strategies.

This narrative review provides an overview of entomo-virological surveillance, encompassing prevention and control strategies for arboviruses, in the context of advancements in virus and vector surveillance tools. We included articles published between January 1, 1994, and December 10, 2024. The literature search encompassed English, Spanish, and Portuguese publications, including peer-reviewed articles, systematic reviews, official documents, randomized controlled trials, and observational studies that utilized entomo-virological approaches for arbovirus surveillance, diagnosis, and prevention. This review aims to inform a diverse audience, including entomologists, virologists, public health managers, academics, and health professionals.

2. What Is Entomo-Virological Surveillance?

The molecular detection of arboviruses in arthropod vectors, including mosquitoes and biting midges, is a critical component of entomo-virological surveillance. This approach involves collecting vector samples from the field and analyzing them to identify the circulation of arboviruses in the environment, enabling the early detection of potential outbreaks. It also plays a critical role in monitoring the geographic distribution and diversity of arboviruses, which is essential for designing targeted control strategies. A notable example is a study carried out in Greece by Tsioka et al., [

7] which demonstrated the effectiveness of entomo-virological surveillance detecting West Nile virus (

Orthoflavivirus nilense - WNV) in mosquitoes two weeks prior to the first reported human case. In regions where arboviral transmission is sporadic or produces mild symptoms, the importance of early detection becomes even more pronounced. Research conducted in India highlighted this utility when Zika virus (

Orthoflavivirus zikaense - ZIKV) was detected in

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, emphasizing the vector’s pivotal role in the 2016–2021 ZIKV epidemic [

8]. Cruz et al. [

9] demonstrate the importance of the entomo-virological approach by analyzing data from the largest outbreak of sylvatic yellow fever virus (

Orthoflavivirus flavi - YFV) in Brazil, between 2016-2018, demonstrating that not only the primary vector

Haemagogus janthinomys was involved in the transmission cycle, but several other species recorded YFV detection, and thus must be closely monitored such as

Ae. albopictus,

Ae. scapularis and

Ae. serratus.

Entomo-virological data can incorporate mathematical models to predict arboviral outbreak risks, identify key drivers of viral transmission, and evaluate the environmental factors influencing viral dissemination. This integrative approach has been validated through several studies, further illustrating its potential to enhance public health preparedness and response [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Entomo-virological surveillance is also a fundamental component of Integrated Vector Management (IVM), a comprehensive strategy that employs a combination of interventions to optimize vector control. The selection of specific interventions within IVM is guided by factors such as the nature of the vector-borne disease problem, cost-effectiveness, ecological sustainability, and available resources [

14]. The urgent need for implementing IVM is underscored by the emergence of insecticide resistance, as well as the globalization-driven introduction of novel vectors and pathogens.

3. How Do Mosquitoes Participate in the Maintenance and Transmission of Arboviruses in the Environment?

Arbovirus transmission involves a complex mechanism of several factors, including a virulent viral strain capable of replicating in both vertebrate and invertebrate hosts, susceptible vertebrate hosts, and competent arthropod vectors. For an arthropod to serve as a vector, it must acquire the pathogen through a blood meal, allow its replication within its body, and subsequently transmit it to a susceptible host [

15]. A critical aspect of this process is the extrinsic incubation period (EIP), which is the time interval between the arthropod acquiring the pathogen and its ability to transmit it via its saliva. The EIP is influenced by environmental factors such as temperature and humidity, as well as vector-intrinsic factors, including susceptibility to infection and interactions with its microbiota. During a viral infection in mosquitoes, the virus must overcome several barriers. These include successful infection and replication in the midgut epithelial cells post-blood meal (Midgut Infection Barrier - MIB), subsequent traversal of the midgut basal lamina to access the mosquito hemocoel (Midgut Escape Barrier - MEB), survival and transportation within the hemocoel to target tissues, primarily the salivary glands, infection of the salivary gland epithelial cells (Salivary Gland Infection Barrier - SGIB), and eventual release into the salivary ducts for dissemination during feeding (Salivary Gland Escape Barrier - SGEB) [

16,

17].

The transmission dynamics of a mosquito arbovirus is primarily shaped by ecological factors, as the cohabitation of mosquitoes and hosts in shared environments enhances transmission opportunities through increased host-mosquito contact rate [

18]. Also, vector longevity is critical since viruses must complete their replication cycle within the mosquito before being transmitted to a new host [

19]. The vector competence varies significantly among mosquito species and even between populations of the same species [

20,

21,

22,

23]. These variations underscore the need to characterize local mosquito populations for accurate arbovirus transmission risk assessments. Furthermore, the appetitive behavior of mosquito populations has been shown to be an important factor in defining their vectorial competence. Recent studies have shown that multiple sequential blood feedings can increase the dissemination of arboviruses in several mosquito genera. This phenomenon may be attributed to several factors, including damage to the midgut basal lamina caused by blood feeding, a reduction in EIP [

24,

25,

26] or acceleration of parasite development [

27,

28].

Mosquitoes exhibit diverse adaptive strategies to cope with environmental changes, including insecticide resistance, ecological plasticity, dietary shifts, and physiological adjustments. Insecticide resistance has become a growing concern in recent years, with studies highlighting the rapid evolution of resistance mechanisms in mosquito populations, such as target-site mutations and increased detoxification enzyme activity, which compromise the efficacy of chemical control measures [

29,

30]. Ecological plasticity enables mosquitoes to exploit a wide range of habitats, from natural to urban environments, allowing species to thrive in densely populated areas with abundant artificial breeding sites [

31,

32]. Dietary shifts, including increased reliance on human blood meals, have been observed in some mosquito populations, further enhancing their ability to transmit pathogens [

33]. Physiological adaptations, such as thermal tolerance, enable mosquitoes to survive in a broader range of climatic conditions, extending their geographic distribution and seasonal activity [

34,

35].

During adverse conditions such as drought or low temperatures, certain mosquito species, such as those of the tribe Aedini, may enter reproductive diapause, a state of suspended development that enhances survival. Recent research has identified the molecular and hormonal pathways involved in diapause, offering insights into how mosquitoes synchronize their reproductive cycles with environmental cues [

36]. Mosquito eggs also demonstrate remarkable resilience, for example,

Ae. aegypti eggs can remain viable for over a year in dry conditions, allowing populations to persist and rebound quickly when conditions improve [

37,

38]. Emerging studies have also reported that these mosquitoes can withstand varying levels of salinity, suggesting an even greater adaptive capacity in response to environmental stressors [

39,

40,

41]. These findings underscore the remarkable adaptability of mosquitoes and the challenges this poses for controlling mosquito-borne diseases in a rapidly changing world.

4. How Does the Prolonged Viability of Mosquito Eggs Influence Viral Transmission Dynamics?

Arthropods are the true reservoir of arboviruses. Once infected, arthropods remain infected and may be capable of transmitting the virus to susceptible vertebrates throughout their lives [

42]. The arthropods are unable to effectively clear the virus from their bodies, and in some instances, can vertically transmit the virus to their offspring, resulting in infected progeny [

43].

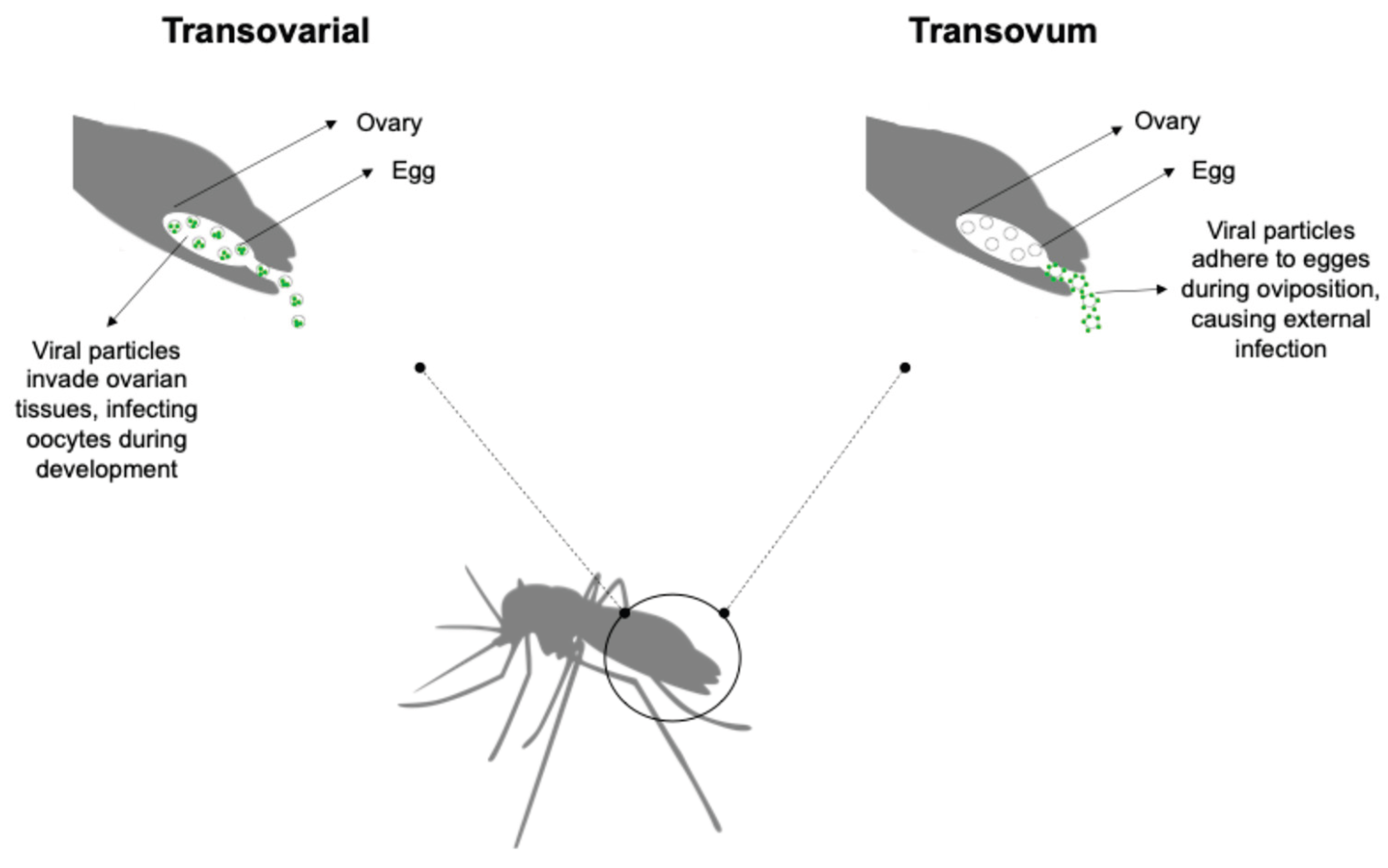

Vertical transmission can occur via two primary mechanisms: transovarial transmission, where the virus infects the female germline, and trans-egg transmission, where the virus infects the developing egg during oviposition (

Figure 1) [

5,

43]. The hypothesis of vertical transmission has been explored in the context of pathogen persistence under adverse environmental conditions, such as drought, winter, interepidemic periods, and intensive vector control measures [

43,

44]. In this scenario, viruses (arboviruses and insect-specific viruses - ISVs) can persist within mosquito eggs, immature stages, and adult females, including those entering diapause, without requiring a vertebrate host [

5]. The detection of arboviruses in male mosquitoes supports the role of vertical transmission in maintaining arbovirus persistence in the environment. A study conducted in Mexico revealed that 6.7% of male mosquitoes collected during a post-epidemic period were positive for arboviruses, with

Alphavirus chikungunya (CHIKV) being the most prevalent (5.7%), followed by

Orthoflavivirus denguei (DENV) (0.9%) and ZIKV (0.1%) [

45]. Alencar et al. [

46] identified positivity for ZIKV and YFV in samples of male and female

Aedes albopictus and

Haemagogus leucocelaenus, collected through ovitraps, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Although

Culex eggs exhibit reduced environmental resilience compared to

Aedes sp. eggs, vertical transmission of arboviruses has been observed in

Culex species [

47]. There is limited information about how these horizontal infection events could trigger new transmission cycles leading to outbreaks or even how this persistence affects the virulence of the viruses. As a result, outbreak forecasting based on traditional epidemiological models that do not incorporate this mechanism may lead to inaccurate predictions.

5. Methodologies Applied to Entomo-Virological Surveillance

Vector surveillance methodologies are, in general, a combination of the techniques employed in field entomology, such as the collection of specimens in the field, identification, and sometimes, its maintenance in the laboratory, and virology techniques that, in part, are based on molecular biology and genomics. Studies focused on the analysis of vector competence of mosquitoes may also use techniques of cell culture and viral isolation [

21,

23,

48].

The choice of mosquito collection strategies depends on the surveillance objective. The methodological design should incorporate the biological and behavioral characteristics of the vector species involved in arbovirus transmission. Both active and passive methods can be used to achieve this, including CDC light traps (LT), CDC LT with CO2 attractants, human landing catches, ovitraps, BG-Pro sentinels, and larval collection. Comprehensive surveillance or outbreak investigations can benefit from a combination of complementary collection methods to facilitate extensive sampling of the local vector population. For example, a study conducted in West Africa using nets suspended from helium balloons at altitudes of 120–290 m allowed the tracking of 61 mosquito species, with some mosquitoes positive for arbovirus,

Plasmodium sp., and filaria infections [

49].

It is necessary to note that the primary objective of entomo-virological surveillance is the detection of viruses. Consequently, all aspects of field operations, from specimen collection and identification to nucleic acid extraction and subsequent analyses, must be optimized to ensure successful viral detection. For instance, mosquitoes collected using traps should be processed promptly and stored under conditions that preserve viral genetic material, such as ultra-refrigeration (-80°C), liquid nitrogen dewar (-196°C) or the use of appropriate preservation media (ethanol, propylene glycol and nucleic acid preservation reagent) [

50,

51].

In entomo-virological studies, a range of life stages can be collected, including eggs [

21,

48], larvae, pupae [

8,

22,

52], and adults [

7,

9,

47,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. Adults are preferentially collected due to the higher likelihood of detecting viral infections, considering both vertical and horizontal transmission routes. The combined effect of vertical and horizontal transmission enables pathogens to persist under conditions that would otherwise lead to their extinction [

43]. Furthermore, morphological identification keys are primarily based on adult mosquitoes, particularly females, as many diagnostic morphological characteristics are not fully developed in early larval instars [

59]. Collecting immature life stages (eggs, larvae, and pupae) is generally considered to pose lower risks to researchers compared to adult collection methods like human landing catches, Shannon traps, and manual aspiration. Nevertheless, collecting immature stages demands a comprehensive understanding of vector ecology and appropriate facilities to rear specimens to later developmental stages [

60]. Another interesting biological specimen processed in some studies is the adult mosquito’s excreta. L’Ambert et al. [

61] were able to detect WNV circulation in Camargue, France, using a xenomonitoring method based on the molecular detection of virus in excreta from trapped mosquitoes. This strategy shed light on how viral surveillance needs to complement standard surveillance methods.

Accurate taxonomic identification is essential for comprehending the dynamics and factors driving arbovirus transmission. Morphological identification remains the gold standard [

59]. However, it necessitates the expertise of skilled taxonomists, particularly when rapid viral detection is the primary goal. Innovative approaches have been developed to supplement or improve the accuracy of mosquito species identification. Machine learning algorithms offer a promising avenue for automated morphological identification, although large datasets are required for training the algorithm [

62]. Over the past two decades, mitochondrial and ribosomal genes have become established tools for species-level taxonomic identification in entomological research. Commonly employed markers include Cytochrome Oxidase 1 (COI), Cytochrome Oxidase B (CytB), ITS2, D2, 28S and 12S rRNA [

59,

63,

64,

65]. DNA barcoding can be integrated with viral detection protocols [

63,

66,

67,

68,

69] providing a valuable tool for situations where expert taxonomic expertise is limited. However, DNA barcoding-based identification still faces challenges in resolving recent intraspecific divergences [

64,

70].

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) has become a cornerstone technique for the direct detection of viruses in mosquito samples within the field of entomo-virology [

7,

8,

9,

47,

53,

56,

57,

58,

67]. While RT-qPCR is often used as a primary detection tool, it is frequently complemented by whole-genome sequencing of positive samples to characterize viral genomes and infer phylogenetic relationships [

7,

47,

53,

55,

57,

67,

71]. A critical aspect of RT-qPCR-based arbovirus detection in mosquitoes is the establishment of a standardized threshold for positivity. The Cycle Threshold (Ct) value, representing the number of cycles required for the fluorescent signal to cross a defined threshold, is commonly used to determine positivity. However, the optimal Ct cutoff can vary depending on factors such as the target virus, sample quality, and assay sensitivity. While some studies have adopted Ct cutoffs of 35 [

23], 37 [

9], 38 [

45,

56,

71], or even 40 [

58], the choice of cutoff remains a subject of ongoing discussion. For samples with high or indeterminate Ct values, it is recommended to perform replicate RT-qPCR assays using separate aliquots of extracted RNA to minimize the risk of compromising RNA integrity due to repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Viral metagenomics offers a novel approach to explore the diverse viral communities associated with mosquito hosts. Unlike targeted RT-qPCR methods, virome analysis provides an unbiased exploration of the entire viral community, including ISVs, viruses associated with the microbiota, and arboviruses [

72]. This approach can facilitate the discovery of novel arboviruses with potential public health significance [

54]. Virome analysis typically involves Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [

73] and often leverages high-throughput sequencing platforms [

68,

74]. While NGS-based virome analysis offers unparalleled depth of viral discovery, it is a resource-intensive methodology that generates vast amounts of data requiring sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines. Factors such as sample type, collection methods, and sequencing depth can significantly influence the complexity and interpretation of virome data [

74]. Although the routine integration of virome analysis into entomo-virological surveillance may be challenging due to technical and logistical constraints, it remains a promising complementary tool for addressing specific research questions and public health concerns.

The positivity of mosquito samples collected from field sites exhibits variability influenced by vector species/lineage, viral species, and geographic location. For instance, studies investigating WNV surveillance have reported an average positivity rate of 4.71% among mosquito pools comprising

Culex sp. and

Aedes sp. in Israel [

53]. A comparable positivity rate of 4.4% for WNV-positive pools was documented in Greece [

55].

To better assess transmission risk, entomo-virological studies often employ additional metrics such as the minimum infection rate (MIR) and maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) beyond simple positivity rates [

7,

8,

10,

44,

47,

52,

56,

57,

58,

75,

76,

77,

78]. The MIR is determined by dividing the number of mosquito pools positive for arboviruses by the total number of mosquitoes tested and multiplying the result by 1000. The MLE is calculated using the formula [

75]:

In this equation:

The MIR provides a conservative estimate of the infection rate, while the MLE offers a more precise estimate of the true infection rate. Under low-intensity transmission scenarios, MIR and MLE values may be comparable. However, in high-transmission or epidemic settings, these two estimates can diverge significantly [

10,

79].

6. The Role of Entomo-Virological Surveillance in Understanding Multi-Vector Transmission of Arboviruses

Upon identifying an arbovirus outbreak or epidemic, immediate preventive actions must be implemented to protect the exposed population. These measures may include vaccination (if available), establishing outpatient and inpatient care services, intensifying laboratory testing, and executing vector control interventions. However, developing a comprehensive prevention and control strategy becomes particularly challenging in urban and rural contexts when multiple vector species are involved in transmitting and maintaining a specific arbovirus. Zoonotic arboviruses that thrive in wild, rural, or suburban environments often rely on multiple vector species and infect a wide range of vertebrate hosts [

80,

81]. The emergence of such arboviruses at epidemic levels can be triggered by disruptions to natural ecosystems caused by changes in viral genetics, host or vector population dynamics, or anthropogenic environmental modifications [

82]. A notable example is the transmission of Oropouche fever in Brazil.

Oropouche fever is a febrile illness in humans caused by the tri-segmented

Orthobunyavirus oropoucheense (OROV). Its clinical presentation, which includes myalgia, arthralgia, and headache, often overlaps with other arboviral infections like dengue. This overlap, coupled with limited diagnostic testing and the co-circulation of multiple arboviruses, contributes to its underreporting [

83]. Before the emergence of CHIKV and ZIKV, OROV was the second most prevalent arbovirus in Brazil after dengue. However, a surge in OROV transmission was detected in Brazil starting in 2023, following the implementation of enhanced laboratory testing for cases negative for Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika. This heightened surveillance revealed significant OROV circulation, initially concentrated in the Brazilian Amazon (Acre, Amazonas, Rondônia, and Roraima) and later spreading to other regions of the country [

84,

85].

While

Culicoides paraensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) is the primary vector for OROV transmission, other mosquito species, such as

Culex quinquefasciatus,

Aedes scapularis,

Aedes serratus,

Coquillettidia venezuelensis,

Psorophora cingulata, and

Haemagogus tropicalis, may also play a role [

56,

83,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89]. Additionally, other

Culicoides species cannot be ruled out as contributors to OROV transmission [

90]. Effective control strategies for vector-borne diseases, especially those without available vaccines, often begin with vector control measures using insecticides. However, uncertainty surrounding the specific roles of multiple vectors with diverse ecological characteristics increases the risk of implementing ineffective control strategies.

A thorough understanding of vector diversity, competence, and biology is essential to designing targeted control strategies that account for technical, economic, environmental, and public health considerations [

91]. Entomo-virological surveillance serves as a critical tool for comprehending the natural history of arboviral diseases and identifying the key factors contributing to the establishment and maintenance of arbovirus transmission. This knowledge is crucial for developing effective preventive measures tailored to the specific epidemiological complexities of each situation.

7. Entomology-Virology for Strengthening Border and Port Surveillance

Virological surveillance for arboviruses necessitates prioritizing strategic locations such as ports, borders, and urban centers. These areas function as critical hubs for the movement of goods, people, and potential vectors, creating an environment conducive to the introduction and dissemination of arboviruses. The challenges associated with border regions are further compounded by disparities in healthcare systems, which can impede the prevention and control of emerging health threats [

92]. The absence of robust surveillance tools in these strategic locations can compromise preparedness and response efforts in the face of emerging imported pathogens. For instance, DENV and YFV, and likely ZIKV, were introduced into Brazil via ports and cross-border human movement. Airports also play a significant role in the introduction of arboviruses [

93,

94,

95,

96]. Travelers can bring new pathogens into a territory. Although the importation of infected vectors is less frequent, it still poses a non-negligible risk. A surveillance program conducted at a major international airport in Central Europe underscored the potential for this route of introduction, revealing high levels of WNV and Usutu virus (

Orthoflavivirus usutuense - USUV) transmission [

47].

8. Challenges in Implementing Entomo-Virological Surveillance for Public Health

Implementing a comprehensive public health surveillance strategy necessitates a multifaceted approach that encompasses management, service organization, and robust data infrastructure. While the collection of relevant indicators is a fundamental component, it alone is insufficient for establishing effective entomo-virological surveillance. A systematic framework for data collection, analysis, and response is essential to ensure timely and appropriate interventions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the development of genomic surveillance capabilities, particularly within public health laboratories in many countries, including Brazil [

97,

98]. Anticipating that climate change may alter the transmission dynamics of arboviruses and increase their impact on human and animal health [

99], it is opportune and strategic to leverage these expanded laboratory capacities for integrated arbovirus surveillance [

97]. Entomo-virological surveillance represents a strategic approach to expanding the genomic surveillance of arboviruses with public health significance. This approach offers several advantages, including the ability to anticipate outbreaks, understand the epidemic potential of emerging and circulating viral strains, and assess the impact of antiviral drugs and novel vector control strategies [

98].

The implementation of entomo-virological surveillance, however, is often hindered by various challenges, including limited human resources, inadequate infrastructure, and difficulties in data collection and sharing. To address these limitations, a comprehensive surveillance strategy should be developed, fostering collaboration among stakeholders, and providing opportunities for training and capacity building. Effective health management is essential for consolidating integrated surveillance systems for arboviruses. This involves coordinating efforts with sectors responsible for solid waste management, urbanization, water supply, and environmental education, as well as engaging with the community. By investing in surveillance infrastructure and promoting data sharing, it is possible to strengthen the integration of environmental, epidemiological, and laboratory surveillance.

9. The Arbovirus Diagnostic Laboratory Network of the Americas (RELDA)

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/WHO), in partnership with its member states, established the Americas Arbovirus Diagnostic Network (RELDA) to enhance the capacity for arbovirus diagnosis and surveillance. Building upon the successful Dengue Laboratory Network of the Americas, which was launched in 2008, RELDA aims to strengthen laboratory infrastructure, harmonize diagnostic protocols, and promote collaboration among laboratories in the region (

https://www.paho.org/en/topics/dengue/arbovirus-diagnosis-laboratory-network-americas-relda).

The emergence of CHIKV and ZIKV viruses in the Americas highlighted the need for a more robust and coordinated regional response to arbovirus outbreaks. As a result, RELDA expanded its scope to include the Arbovirus Genomic Surveillance Platform (ViGenDa) and the Entomo-virological Laboratory Network (RELEVA). Currently, RELDA comprises 40 laboratories from across the Americas, including Argentina, Brazil, Canada, and the United States. These laboratories collaborate to improve diagnostic capabilities, share data, and respond to emerging threats. Additionally, five collaborating centers provide technical support and guidance to the network. These centers include the National Institute of Human Viral Diseases in Argentina, the Evandro Chagas Institute in Brazil, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States.

10. Conclusions

Entomo-virological surveillance is a necessary tool for assessing risks and identifying the factors that drive arbovirus outbreaks and epidemics. In public health, this type of surveillance can be implemented at various levels, ranging from localized monitoring in specific areas such as ports, airports, and sentinel municipalities to broader, nationwide efforts, depending on the operational resources available.

Transmission dynamics of arboviruses depends on specific environmental conditions, characteristics of the arboviruses itself and its vectors (especially the capacity of being maintained in for several months in eggs), and previous contact of human populations with that pathogen, which will affect their susceptibility to disease and symptoms. All factors will influence the risk assessment of a local population.

Several methods to assess mosquitoes and arboviruses identification using high-throughput genetic data may contribute significantly to access transmission risk and comparing outbreaks in different areas. However, the conditions needed to achieve the whole potential of those strategies are challenging due to the complex logistic to routinely use them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design: P.S.L. and. M.M.M.P.; literature review and bibliographic search: P.L.S., B.L.S.N., M.M.M.P., D.D.D. and M.S.C.; data/information analysis and interpretation: L.S.S., M.M.M.P., S.P.S and L.C.F.F.; original draft writing: P.S.L.; critical review and final editing: M.A.M.S and S.P.S.; final version approval: All authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CDC LT |

CDC light traps |

| CHIKV |

Alphavirus chikungunya |

| COI |

Cytochrome Oxidase 1 |

| Ct |

Cycle Threshold |

| CytB |

Cytochrome Oxidase B |

| DENV |

Orthoflavivirus denguei |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| EIP |

Extrinsic Incubation Period |

| IVM |

Integrated Vector Management |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MEB |

Midgut Escape Barrier |

| MIB |

Midgut Infection Barrier |

| MIR |

Minimum infection rate |

| MLE |

Maximum likelihood estimate |

| NGS |

Next-Generation Sequencing |

| OROV |

Orthobunyavirus oropoucheense |

| PAHO |

Pan American Health Organization |

| RELDA |

Americas Arbovirus Diagnostic Network |

| RELEVA |

Entomo-virological Laboratory Network |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| rRNA |

Ribosomal RNA |

| RT-qPCR |

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SGEB |

Salivary Gland Escape Barrier |

| SGIB |

Salivary Gland Infection Barrier |

| USUV |

Orthoflavivirus usutuense |

| ViGenDa |

Arbovirus Genomic Surveillance Platform |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| WNV |

Orthoflavivirus nilense |

| YFV |

Orthoflavivirus flavi |

| ZIKV |

Orthoflavivirus zikaense |

References

- World Health Organization. UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases Global Vector Control Response 2017-2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2017; ISBN 978-92-4-151297-8. [Google Scholar]

- Donalisio, M.R.; Freitas, A.R.R.; Zuben, A.P.B.V. Arboviruses Emerging in Brazil: Challenges for Clinic and Implications for Public Health. Rev. Saúde Pública 2017, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, L.; Matthews, E.; Piquet, A.L.; Henao-Martinez, A.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Tyler, K.L.; Beckham, D.; Pastula, D.M. Nervous System Manifestations of Arboviral Infections. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2022, 9, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, D.S.; Undurraga, E.A.; Halasa, Y.A.; Stanaway, J.D. The Global Economic Burden of Dengue: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lequime, S.; Lambrechts, L. Vertical Transmission of Arboviruses in Mosquitoes: A Historical Perspective. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 28, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weetman, D.; Kamgang, B.; Badolo, A.; Moyes, C.; Shearer, F.; Coulibaly, M.; Pinto, J.; Lambrechts, L.; McCall, P. Aedes Mosquitoes and Aedes-Borne Arboviruses in Africa: Current and Future Threats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsioka, K.; Gewehr, S.; Pappa, S.; Kalaitzopoulou, S.; Stoikou, K.; Mourelatos, S.; Papa, A. West Nile Virus in Culex Mosquitoes in Central Macedonia, Greece, 2022. Viruses 2023, 15, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Gupta, S.K.; Singh, H. Surveillance of Zika and Dengue Viruses in Field-Collected Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes from Different States of India. Virology 2022, 574, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.C.R.; Hernández, L.H.A.; Aragão, C.F.; Da Paz, T.Y.B.; Da Silva, S.P.; Da Silva, F.S.; De Aquino, A.A.; Cereja, G.J.G.P.; Nascimento, B.L.S.D.; Rosa Junior, J.W.; et al. The Importance of Entomo-Virological Investigation of Yellow Fever Virus to Strengthen Surveillance in Brazil. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevallos, V.; Ponce, P.; Waggoner, J.J.; Pinsky, B.A.; Coloma, J.; Quiroga, C.; Morales, D.; Cárdenas, M.J. Zika and Chikungunya Virus Detection in Naturally Infected Aedes Aegypti in Ecuador. Acta Trop. 2018, 177, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fan, Z.-W.; Ji, Y.; Chen, J.-J.; Zhao, G.-P.; Zhang, W.-H.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Jiang, B.-G.; Xu, Q.; Lv, C.-L.; et al. Mapping the Distributions of Mosquitoes and Mosquito-Borne Arboviruses in China. Viruses 2022, 14, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbanks, E.L.; Daly, J.M.; Tildesley, M.J. Modelling the Influence of Climate and Vector Control Interventions on Arbovirus Transmission. Viruses 2024, 16, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros-Sousa, A.R.; Lange, M.; Mucci, L.F.; Marrelli, M.T.; Grimm, V. Modelling the Transmission and Spread of Yellow Fever in Forest Landscapes with Different Spatial Configurations. Ecol. Model. 2024, 489, 110628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Handbook for Integrated Vector Management. <b>2012</b>, 67.

- Salazar, M.I.; Richardson, J.H.; Sánchez-Vargas, I.; Olson, K.E.; Beaty, B.J. Dengue Virus Type 2: Replication and Tropisms in Orally Infected Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes. BMC Microbiol. 2007, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, A.; Kantor, A.; Passarelli, A.; Clem, R. Tissue Barriers to Arbovirus Infection in Mosquitoes. Viruses 2015, 7, 3741–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.; Gallichotte, E.N.; Randall, J.; Glass, A.; Foy, B.D.; Ebel, G.D.; Kading, R.C. Intrinsic Factors Driving Mosquito Vector Competence and Viral Evolution: A Review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1330600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, W.J. Ecological Effects on Arbovirus-Mosquito Cycles of Transmission. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 21, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Yu, X.; Wang, P.; Cheng, G. Arbovirus Lifecycle in Mosquito: Acquisition, Propagation and Transmission. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2019, 21, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, W.C.; Bennett, K.E.; Gorrochótegui-Escalante, N.; Barillas-Mury, C.V.; Fernández-Salas, I.; De Lourdes Muñoz, M.; Farfán-Alé, J.A.; Olson, K.E.; Beaty, B.J. Flavivirus Susceptibility in Aedes Aegypti. Arch. Med. Res. 2002, 33, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Bugallo, G.; Boullis, A.; Martinez, Y.; Hery, L.; Rodríguez, M.; Bisset, J.A.; Vega-Rúa, A. Vector Competence of Aedes Aegypti from Havana, Cuba, for Dengue Virus Type 1, Chikungunya, and Zika Viruses. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Vargas, R.E.; Missé, D.; Chavez, I.F.; Kittayapong, P. Vector Competence for Dengue-2 Viruses Isolated from Patients with Different Disease Severity. Pathogens 2020, 9, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoa-Bosompem, M.; Kobayashi, D.; Itokawa, K.; Murota, K.; Faizah, A.N.; Azerigyik, F.A.; Hayashi, T.; Ohashi, M.; Bonney, J.H.K.; Dadzie, S.; et al. Determining Vector Competence of Aedes Aegypti from Ghana in Transmitting Dengue Virus Serotypes 1 and 2. Parasit. Vectors 2021, 14, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, P.M.; Ehrlich, H.Y.; Magalhaes, T.; Miller, M.R.; Conway, P.J.; Bransfield, A.; Misencik, M.J.; Gloria-Soria, A.; Warren, J.L.; Andreadis, T.G.; et al. Successive Blood Meals Enhance Virus Dissemination within Mosquitoes and Increase Transmission Potential. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 5, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.M.; Cozens, D.W.; Ferdous, Z.; Armstrong, P.M.; Brackney, D.E. Increased Blood Meal Size and Feeding Frequency Compromise Aedes Aegypti Midgut Integrity and Enhance Dengue Virus Dissemination. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdous, Z.; Dieme, C.; Sproch, H.; Kramer, L.D.; Ciota, A.T.; Brackney, D.E.; Armstrong, P.M. Multiple Bloodmeals Enhance Dissemination of Arboviruses in Three Medically Relevant Mosquito Genera. Parasit. Vectors 2024, 17, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, W.R.; Holmdahl, I.E.; Itoe, M.A.; Werling, K.; Marquette, M.; Paton, D.G.; Singh, N.; Buckee, C.O.; Childs, L.M.; Catteruccia, F. Multiple Blood Feeding in Mosquitoes Shortens the Plasmodium Falciparum Incubation Period and Increases Malaria Transmission Potential. PLOS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1009131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackney, D.E.; LaReau, J.C.; Smith, R.C. Frequency Matters: How Successive Feeding Episodes by Blood-Feeding Insect Vectors Influences Disease Transmission. PLOS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.P.; Paiva, M.H.S.; De Araújo, A.P.; Da Silva, É.V.G.; Da Silva, U.M.; De Oliveira, L.N.; Santana, A.E.G.; Barbosa, C.N.; De Paiva Neto, C.C.; Goulart, M.O.; et al. Insecticide Resistance in Aedes Aegypti Populations from Ceará, Brazil. Parasit. Vectors 2011, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyes, C.L.; Vontas, J.; Martins, A.J.; Ng, L.C.; Koou, S.Y.; Dusfour, I.; Raghavendra, K.; Pinto, J.; Corbel, V.; David, J.-P.; et al. Contemporary Status of Insecticide Resistance in the Major Aedes Vectors of Arboviruses Infecting Humans. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndenga, B.A.; Mutuku, F.M.; Ngugi, H.N.; Mbakaya, J.O.; Aswani, P.; Musunzaji, P.S.; Vulule, J.; Mukoko, D.; Kitron, U.; LaBeaud, A.D. Characteristics of Aedes Aegypti Adult Mosquitoes in Rural and Urban Areas of Western and Coastal Kenya. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0189971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasegaran, K.; Lahondère, C.; Escobar, L.E.; Vinauger, C. Linking Mosquito Ecology, Traits, Behavior, and Disease Transmission. Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, L.C.; Edman, J.D.; Scott, T.W. Why Do Female <I>Aedes Aegypti</I> (Diptera: Culicidae) Feed Preferentially and Frequently on Human Blood? J. Med. Entomol. 2001, 38, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mordecai, E.A.; Caldwell, J.M.; Grossman, M.K.; Lippi, C.A.; Johnson, L.R.; Neira, M.; Rohr, J.R.; Ryan, S.J.; Savage, V.; Shocket, M.S.; et al. Thermal Biology of Mosquito-borne Disease. Ecol. Lett. 2019, 22, 1690–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahondère, C.; Bonizzoni, M. Thermal Biology of Invasive Aedes Mosquitoes in the Context of Climate Change. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2022, 51, 100920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, C.; Denlinger, D.L. Insulin Signaling and the Regulation of Insect Diapause. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.H.G.D.; Silva, I.G.D. Influência do período de quiescência dos ovos sobre o ciclo de vida de Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus, 1762) (Diptera, Culicidae) em condições de laboratório. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 1999, 32, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Sreedharan, S.; Bakthavachalu, B.; Laxman, S. Eggs of the Mosquito Aedes Aegypti Survive Desiccation by Rewiring Their Polyamine and Lipid Metabolism. PLOS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multini, L.C.; Oliveira-Christe, R.; Medeiros-Sousa, A.R.; Evangelista, E.; Barrio-Nuevo, K.M.; Mucci, L.F.; Ceretti-Junior, W.; Camargo, A.A.; Wilke, A.B.B.; Marrelli, M.T. The Influence of the pH and Salinity of Water in Breeding Sites on the Occurrence and Community Composition of Immature Mosquitoes in the Green Belt of the City of São Paulo, Brazil. Insects 2021, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduino, M. deBrito; Mucci, L.; Serpa, L.N.; Rodrigues, M. deMoura Effect of Salinity on the Behavior of Aedes Aegypti Populations from the Coast and Plateau of Southeastern Brazil. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2015, 52, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasari, A.; Jabal, A.R.; Syahribulan, S.; Idris, I.; Rahma, N.; Rustam, S.N.R.N.; Karmila, M.; Hasan, H.; Wahid, I. Salinity Tolerance of Larvae Aedes Aegypti Inland and Coastal Habitats in Pasangkayu, West Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, R.A.G.B.; Oliveira, R.L.D. Principais Mosquitos de Importância Sanitária No Brasil; Editora FIOCRUZ, 1994; ISBN 978-85-7541-290-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lequime, S.; Paul, R.E.; Lambrechts, L. Determinants of Arbovirus Vertical Transmission in Mosquitoes. PLOS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, N.; Yadav, M.; Yadav, A.; Sehrawat, N. Zika Virus Vertical Transmission in Mosquitoes: A Less Understood Mechanism. J Vector Borne Dis 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirstein, O.D.; Talavera, G.A.; Wei, Z.; Ciau-Carrilo, K.J.; Koyoc-Cardeña, E.; Puerta-Guardo, H.; Rodríguez-Martín, E.; Medina-Barreiro, A.; Mendoza, A.C.; Piantadosi, A.L.; et al. Natural Aedes -Borne Virus Infection Detected in Male Adult Aedes Aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Collected From Urban Settings in Mérida, Yucatán, México. J. Med. Entomol. 2022, 59, 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alencar, J.; Ferreira De Mello, C.; Brisola Marcondes, C.; Érico Guimarães, A.; Toma, H.K.; Queiroz Bastos, A.; Olsson Freitas Silva, S.; Lisboa Machado, S. Natural Infection and Vertical Transmission of Zika Virus in Sylvatic Mosquitoes Aedes Albopictus and Haemagogus Leucocelaenus from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakran-Lebl, K.; Camp, J.V.; Kolodziejek, J.; Weidinger, P.; Hufnagl, P.; Cabal Rosel, A.; Zwickelstorfer, A.; Allerberger, F.; Nowotny, N. Diversity of West Nile and Usutu Virus Strains in Mosquitoes at an International Airport in Austria. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 2096–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-Y.; Bozic, J.; Mathias, D.; Smartt, C.T. Immune-Related Transcripts, Microbiota and Vector Competence Differ in Dengue-2 Virus-Infected Geographically Distinct Aedes Aegypti Populations. Parasit. Vectors 2023, 16, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamou, R.; Dao, A.; Yaro, A.; Kouam, C.; Ergunay, K.; Bourke, B.; Diallo, M.; Sanogo, Z.; Samake, D.; Afrane, Y.; et al. Pathogens Spread by High-Altitude Windborne Mosquitoes 2024.

- Torres, M.G.; Weakley, A.M.; Hibbert, J.D.; Kirstein, O.D.; Lanzaro, G.C.; Lee, Y. Ethanol as a Potential Mosquito Sample Storage Medium for RNA Preservation. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, I.; Kobayashi, D.; Itokawa, K.; Sanjoba, C.; Itoyama, K.; Isawa, H. Evaluation of Long-Term Preservation Methods for Viral RNA in Mosquitoes at Room Temperature. J. Virol. Methods 2024, 325, 114887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, J.; Kushwah, R.B.S.; Singh, S.S.; Sharma, A.; Adak, T.; Singh, O.P.; Bhatnagar, R.K.; Subbarao, S.K.; Sunil, S. Evidence for Natural Vertical Transmission of Chikungunya Viruses in Field Populations of Aedes Aegypti in Delhi and Haryana States in India—a Preliminary Report. Acta Trop. 2016, 162, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, Y.; Hindiyeh, M.; Orshan, L.; Weiss, L.; Koren, R.; Katz-Likvornik, S.; Zadka, H.; Glatman-freedman, A.; Mendelson, E.; Shulman, L.M. Mosquito Surveillance for 15 Years Reveals High Genetic Diversity Among West Nile Viruses in Israel. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Altan, E.; Deng, X.; Barker, C.M.; Fang, Y.; Coffey, L.L.; Delwart, E. Virome of > 12 Thousand Culex Mosquitoes from throughout California. Virology 2018, 523, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, A.; Gewehr, S.; Tsioka, K.; Kalaitzopoulou, S.; Pappa, S.; Mourelatos, S. Detection of Flaviviruses and Alphaviruses in Mosquitoes in Central Macedonia, Greece, 2018. Acta Trop. 2020, 202, 105278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Silva, J.W.; Ríos-Velásquez, C.M.; Lima, G.R.D.; Marialva Dos Santos, E.F.; Belchior, H.C.M.; Luz, S.L.B.; Naveca, F.G.; Pessoa, F.A.C. Distribution and Diversity of Mosquitoes and Oropouche-like Virus Infection Rates in an Amazonian Rural Settlement. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0246932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, S.E.; Jones, J.A.; LaDeau, S.L.; Leisnham, P.T. Higher West Nile Virus Infection in Aedes Albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) and Culex (Diptera: Culicidae) Mosquitoes From Lower Income Neighborhoods in Urban Baltimore, MD. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 1424–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, M.-G.; Lee, H.S.; Yang, S.-C.; Noh, B.-E.; Kim, T.-K.; Lee, W.-G.; Lee, H.I. National Monitoring of Mosquito Populations and Molecular Analysis of Flavivirus in the Republic of Korea in 2020. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Chiang, L.-P.; Hapuarachchi, H.C.; Tan, C.-H.; Pang, S.-C.; Lee, R.; Lee, K.-S.; Ng, L.-C.; Lam-Phua, S.-G. DNA Barcoding: Complementing Morphological Identification of Mosquito Species in Singapore. 2014.

- McDermott, E.G.; Lysyk, T.J. Sampling Considerations for Adult and Immature Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae). J. Insect Sci. 2020, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Ambert, G.; Gendrot, M.; Briolant, S.; Nguyen, A.; Pages, S.; Bosio, L.; Palomo, V.; Gomez, N.; Benoit, N.; Savini, H.; et al. Analysis of Trapped Mosquito Excreta as a Noninvasive Method to Reveal Biodiversity and Arbovirus Circulation. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2023, 23, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittichai, V.; Kaewthamasorn, M.; Samung, Y.; Jomtarak, R.; Naing, K.M.; Tongloy, T.; Chuwongin, S.; Boonsang, S. Automatic Identification of Medically Important Mosquitoes Using Embedded Learning Approach-Based Image-Retrieval System. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batovska, J.; Lynch, S.E.; Cogan, N.O.I.; Brown, K.; Darbro, J.M.; Kho, E.A.; Blacket, M.J. Effective Mosquito and Arbovirus Surveillance Using Metabarcoding. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018, 18, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes Zenker, M.; Portella, T.P.; Pessoa, F.A.C.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Galetti, P.M. Low Coverage of Species Constrains the Use of DNA Barcoding to Assess Mosquito Biodiversity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.M.P.; Saraiva, J.F.; Da Silva, H.; Sallum, M.A.M. Molecular Identification of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) Using COI Barcode and D2 Expansion of 28S Gene. DNA 2024, 4, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-López, R.; Suaza-Vasco, J.; Rúa-Uribe, G.; Uribe, S.; Gallego-Gómez, J.C. Molecular Detection of Flaviviruses and Alphaviruses in Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from Coastal Ecosystems in the Colombian Caribbean. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2016, 111, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarido, M.M.; Govender, K.; Riddin, M.A.; Schrama, M.; Gorsich, E.E.; Brooke, B.D.; Almeida, A.P.G.; Venter, M. Detection of Insect-Specific Flaviviruses in Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in Northeastern Regions of South Africa. Viruses 2021, 13, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, M.; Wahaab, A.; Shan, T.; Wang, X.; Khan, S.; Di, D.; Xiqian, L.; Zhang, J.-J.; Anwar, M.N.; Nawaz, M.; et al. A Metagenomic Analysis of Mosquito Virome Collected From Different Animal Farms at Yunnan–Myanmar Border of China. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 591478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Triana, L.M.; Garza-Hernández, J.A.; Ortega Morales, A.I.; Prosser, S.W.J.; Hebert, P.D.N.; Nikolova, N.I.; Barrero, E.; De Luna-Santillana, E.D.J.; González-Alvarez, V.H.; Mendez-López, R.; et al. An Integrated Molecular Approach to Untangling Host–Vector–Pathogen Interactions in Mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) From Sylvan Communities in Mexico. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 564791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beebe, N.W. DNA Barcoding Mosquitoes: Advice for Potential Prospectors. Parasitology 2018, 145, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, B.J.; Nicholson, J.; Winokur, O.C.; Steiner, C.; Riemersma, K.K.; Stuart, J.; Takeshita, R.; Krasnec, M.; Barker, C.M.; Coffey, L.L. Vector Competence of Aedes Aegypti, Culex Tarsalis, and Culex Quinquefasciatus from California for Zika Virus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonen, J.P.; Schinkel, M.; Van Der Most, T.; Miesen, P.; Van Rij, R.P. Composition and Global Distribution of the Mosquito Virome - A Comprehensive Database of Insect-Specific Viruses. One Health 2023, 16, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Martínez, D.; Páez-Triana, L.; Luna, N.; De Las Salas, J.L.; Hernández, C.; Flórez, A.Z.; Muñoz, M.; Ramírez, J.D. Characterizing Viral Species in Mosquitoes (Culicidae) in the Colombian Orinoco: Insights from a Preliminary Metagenomic Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cui, F.; Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Fang, W.; Kang, X.; Lu, H.; Li, S.; Liu, B.; Guo, W.; et al. Association of Virome Dynamics with Mosquito Species and Environmental Factors. Microbiome 2023, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condotta, S.A.; Hunter, F.F.; Bidochka, M.J. West Nile Virus Infection Rates in Pooled and Individual Mosquito Samples. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2004, 4, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balingit, J.C.; Carvajal, T.M.; Saito-Obata, M.; Gamboa, M.; Nicolasora, A.D.; Sy, A.K.; Oshitani, H.; Watanabe, K. Surveillance of Dengue Virus in Individual Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes Collected Concurrently with Suspected Human Cases in Tarlac City, Philippines. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, C.J.; Grossi-Soyster, E.N.; Ndenga, B.A.; Mutuku, F.M.; Sahoo, M.K.; Ngugi, H.N.; Mbakaya, J.O.; Siema, P.; Kitron, U.; Zahiri, N.; et al. Evidence of Transovarial Transmission of Chikungunya and Dengue Viruses in Field-Caught Mosquitoes in Kenya. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish, D.; Tesh, R.B.; Guzman, H.; Travassos Da Rosa, A.P.A.; Balta, V.; Underwood, J.; Sither, C.; Vasilakis, N. Emergence Potential of Mosquito-Borne Arboviruses from the Florida Everglades. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0259419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Lampman, R.; Novak, R.J. Problems in Estimating Mosquito Infection Rates Using Minimum Infection Rate. J. Med. Entomol. 2003, 40, 595–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, N.; Bradbury, R.S.; Aaskov, J.G.; Taylor-Robinson, A.W. Neglected Australian Arboviruses: Quam Gravis? Microbes Infect. 2017, 19, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, C.H.; Andrade, M.S.; Campos, F.S.; Da, C. Cardoso, J.; Gonçalves-dos-Santos, M.E.; Oliveira, R.S.; Aquino-Teixeira, S.M.; Campos, A.A.; Almeida, M.A.; Simonini-Teixeira, D.; et al. Yellow Fever Virus Maintained by Sabethes Mosquitoes during the Dry Season in Cerrado, a Semiarid Region of Brazil, in 2021. Viruses 2023, 15, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.C.; Reisen, W.K. Present and Future Arboviral Threats. Antiviral Res. 2010, 85, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Corrado, S.; Bottazzoli, M.; Marchesi, F.; Gili, R.; Bianchi, F.P.; Frisicale, E.M.; Guicciardi, S.; Fiacchini, D.; Tafuri, S.; et al. (Re-)Emergence of Oropouche Virus (OROV) Infections: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Viruses 2024, 16, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRAZIL. Ministry of Health. NOTA TÉCNICA No 6/2024-CGARB/DEDT/SVSA/MS 2024.

- Naveca, F.G.; Almeida, T.A.P.D.; Souza, V.; Nascimento, V.; Silva, D.; Nascimento, F.; Mejía, M.; Oliveira, Y.S.D.; Rocha, L.; Xavier, N.; et al. Human Outbreaks of a Novel Reassortant Oropouche Virus in the Brazilian Amazon Region. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3509–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Alvarez, D.; Escobar, L.E. Oropouche Fever, an Emergent Disease from the Americas. Microbes Infect. 2018, 20, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mendonça, S.F.; Rocha, M.N.; Ferreira, F.V.; Leite, T.H.J.F.; Amadou, S.C.G.; Sucupira, P.H.F.; Marques, J.T.; Ferreira, A.G.A.; Moreira, L.A. Evaluation of Aedes Aegypti, Aedes Albopictus, and Culex Quinquefasciatus Mosquitoes Competence to Oropouche Virus Infection. Viruses 2021, 13, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifay, T.; Le Turnier, P.; Epelboin, Y.; Carvalho, L.; De Thoisy, B.; Djossou, F.; Duchemin, J.-B.; Dussart, P.; Enfissi, A.; Lavergne, A.; et al. Review on Main Arboviruses Circulating on French Guiana, An Ultra-Peripheric European Region in South America. Viruses 2023, 15, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Feng, S.; Lu, K.; Zhu, W.; Sun, H.; Niu, G. Oropouche Virus: A Neglected Global Arboviral Threat. Virus Res. 2024, 341, 199318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Requena-Zúñiga, E.; Palomino-Salcedo, M.; García-Mendoza, M.P.; Figueroa-Romero, M.D.; Merino-Sarmiento, N.S.; Escalante-Maldonado, O.; Cornelio-Santos, A.L.; Cárdenas-Garcia, P.; Jiménez, C.A.; Cabezas-Sanchez, C. First Detection of Oropouche Virus in Culicoides Insignis in the Ucayali Region, Peru: Evidence of a Possible New Vector 2024.

- Carpenter, S.; Mellor, P.S.; Torr, S.J. Control Techniques for Culicoides Biting Midges and Their Application in the U.K. and Northwestern Palaearctic. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2008, 22, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Melo, G.Z.; Andrade, S.R.D.; Rocha, Y.A.D.; Cosme, K.D.O.; Pereira, T.C.L.; Monteiro, A.X.; Ribeiro, G.M.D.A.; Passos, S.M.D.A. Importância e desafios da vigilância em saúde em uma região de fronteira internacional: um estudo de caso. Saúde E Soc. 2023, 32, e220433pt. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchimol, J.L. História Da Febre Amarela No Brasil. História Ciênc. Saúde-Manguinhos 1994, 1, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, Ima Aparecida; Valle, Denise Aedes aegypti: histórico do controle no Brasil 2007.

- Faria, N.R.; Quick, J.; Claro, I.M.; Thézé, J.; De Jesus, J.G.; Giovanetti, M.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Hill, S.C.; Black, A.; Da Costa, A.C.; et al. Establishment and Cryptic Transmission of Zika Virus in Brazil and the Americas. Nature 2017, 546, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveca, F.G.; Claro, I.; Giovanetti, M.; De Jesus, J.G.; Xavier, J.; Iani, F.C.D.M.; Do Nascimento, V.A.; De Souza, V.C.; Silveira, P.P.; Lourenço, J.; et al. Genomic, Epidemiological and Digital Surveillance of Chikungunya Virus in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.; Yu, M.A.; Sacks, J.; Barnadas, C.; Pereyaslov, D.; Cognat, S.; Briand, S.; Ryan, M.; Samaan, G. Global Genomic Surveillance Strategy for Pathogens with Pandemic and Epidemic Potential 2022–2032. Bull. World Health Organ. 2022, 100, 239–239A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallau, G.L.; Abanda, N.N.; Abbud, A.; Abdella, S.; Abera, A.; Ahuka-Mundeke, S.; Falconi-Agapito, F.; Alagarasu, K.; Ariën, K.K.; Ayres, C.F.J.; et al. Arbovirus Researchers Unite: Expanding Genomic Surveillance for an Urgent Global Need. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1501–e1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, W.M.; Weaver, S.C. Effects of Climate Change and Human Activities on Vector-Borne Diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).