1. Introduction

The largest organ in the body is the skin, which acts as a barrier against the entry of foreign pathogens, thermoregulation, and sensation [

1]. Given the skin's numerous functions, one can only imagine the problems that might arise when the skin is injured or not functioning correctly. Injuries can damage a victim's psychological well-being and endanger the skin barrier's function as a defense mechanism. If wounds are not treated, they may turn fatal. Also, the pathogens are not eliminated during an injury. In that case, the tissue is further invaded, and it impedes wound healing depending on the degree of the injury and the immune system's strength. However, some bacteria need moisture and nutrients at the wound site to grow when they invade a wound. Therefore, the amount of nutrients that are available to the cells that are growing is limited. Invasion of bacteria at a wound site can make the wound chronic and more difficult to treat [

2]. The largest organ in the body is the skin, which acts as a barrier against the entry of foreign pathogens, thermoregulation, and sensation [

1]. Given the skin's numerous functions, one can only imagine the problems that might arise when the skin is injured or not functioning correctly. Injuries can damage a victim's psychological well-being and endanger the skin barrier's function as a defense mechanism. If wounds are not treated, they may turn fatal. Also, the pathogens are not eliminated during an injury. In that case, the tissue is further invaded, and it impedes wound healing depending on the degree of the injury and the immune system's strength. However, some bacteria need moisture and nutrients at the wound site to grow when they invade a wound. Therefore, the amount of nutrients that are available to the cells that are growing is limited. Invasion of bacteria at a wound site can make the wound chronic and more difficult to treat [

2].

Nearly 6.5 million people in the U.S. experience chronic wounds each year, and that expense amounts to about

$25 billion annually [

2,

3,

4]. Therefore, an enormous amount of interest has been shown in wound dressings that contain antimicrobial agents to prevent bacterial invasion of the wound site. The bacteria and cells in wound healing compete at the wound site. However, if they adhere first, bacteria are more likely to take over the wound site.

There are several types of materials used in wound dressings. For example, Nonwoven textiles prepared from hyaluronan (HA) have low porosity, non-toxicity, and excellent mechanical strength [

5]. Suitable wound dressing materials should have hemostatic [

6,

7] and anti-inflammatory properties [

8,

9], be non-toxic [

10], be able to provide gas exchange [

11], have fibroblast and keratinocyte proliferation, and easily remove without irritating. Unnecessary changes in wound dressings can be painful and lead to injury, thereby creating disturbances in the process. Therefore, several nanoparticles have been loaded into electrospun textiles for wound-healing applications [

12]. For example, AgNPs are loaded into an electrospun textile with kaolinite to inhibit bacteria growth by opening the bacteria cell membrane [

13].

Electrospinning is the fundamental technology for fabricating fiber materials [

14]. However, in recent years, solution blow spinning (SBS) has started to gain the attention of researchers due to its advantages over electrospinning and other spinning techniques such as melt blown, centrifugal spinning, and magnetic-mechanical spinning [

15,

16]. SBS is an inexpensive, simple apparatus technique that involves using two fluids: a solvent to dissolve the polymer and a pressurized gas. SBS setup consists of a syringe pump, an airbrush, and a compressed gas [

17]. SBS technology and large-scale fabrication can use different ranges of materials. In addition, SBS is helpful in the fabrication technique where a voltage-sensitive polymer is involved since it does not require voltage use [

18].

Lou et al. (2013) demonstrated a way to fabricate micro/nanofibers by investigating four factors of SBS, which include injection rate, air pressure, solution concentration, and the nozzle diameter by fabricating polyethylene oxide (PEO) micro/nanofibers and concluded that these four factors affected the fabricated fiber diameter [

19]. Some of the limitations of SBS include the uneven distribution of fibers leading to poor fiber morphology, the polymer concentration type, liquid intake, atmospheric and gas pressure, and the working distance [

18]. The solvent evaporation rate is one of the advantages of SBS over other spinning techniques.

Magnesium oxide (MgO) has been shown to have excellent antibacterial properties against

E. coli [

20]

, B. subtilis, and B. megaterium [

21] mycobacterium tuberculosis [

22] by destroying their cell membrane, which will cause the release of the cell content and in turns cell death [

23]. MgO is superior to other nanoparticles such as Ag, Cu, and TiO

2 because of its precursor availability, biocompatible, and excellent antibacterial properties [

20]; this establishes their application in waste management, electronics, medical industry, as well as orthopedic for bone regeneration [

20].

Silicon nitride (Si

3N

4) may be a potential therapeutic option for treating bone diseases and physiologically regulating the processes of bone development [

24]. The biological relationship between living cells and Si

3N

4 was investigated, and their findings were built upon prior research [

25] and indicated that Si

3N

4 has medicinal therapies for joint diseases [

26]. Si

3N

4 is optimized to give a zwitterionic-like property showing improved osteoconductive and cell adhesion, making them applicable as bone substitutes and containing anti-fouling properties [

27]. Due to Si

3N

4 properties, it was shown to have applications in drug delivery [

28], orthopedics [

29], and antimicrobial agents [

30]. For example, Si

3N

4 was used to fabricate total hip arthroplasty bearing and compared with bearing fabricated with only Al

2O

3, which shows inferior fracture toughness and strength compared to reinforcing Si

3N

4 with Al

2O

3, which produces more improved properties [

31].

Halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) are a type of nanomaterial that is naturally available and abundant in clay particles [

32]. Halloysite nanotubes are double-layered aluminosilicate nanoclay with a predominantly hollow tubular structure. It has a chemical formula of Al

2Si

2O

5(OH)

4nH

2O. HNTs have an external diameter of 50 – 80 nm, an inner lumen of 10 - 15 nm, and a length of 1 µm [

33]. Each cylinder has concentric alternating layers of aluminum and silicate, giving the cylinder or tube positive and negatively charged layers. These alternating charges make halloysite nanoparticles suitable adsorbents for cations and anions. HNTs are abundantly and commercially available cheaply (

$15/metric ton), attracting increased interest across engineering and science disciplines [

34]. HNTs were reported to be non-toxic and biocomposite. Due to the weak intermolecular forces of HNT, they must undergo surface modification by reinforcing them with other materials to improve their properties. For instance, surface modification of HNT with bis(triethoxysilylpropyl)-tetrasulfide resulted in superior thermal stability and physical properties compared to the HNT without modification [

35].

This study shows the potential of Si3N4 and magnesium-coated HNTs (MgO/HNTs) fibers and their bacteriostatic activity. Furthermore, the effect that the silicon nitride and MgO/HNT concentration and their combined ratio have on the antimicrobial properties of the blow-spun nanocomposite fibers were equally analyzed. In addition, the effect of these polymers on the cell in vitro for fibroblast cells was demonstrated.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

Magnesium oxide (CAS: 1309-48-4), halloysite nanoclay (LOT: 685445-500G, CAS: 1332-58-7), senescence cell histochemical staining kit (CAT: #CS0030-1KT), and gentamicin sulfate salt (LOT #049M4874V) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM) (LOT: 2393824) and penicillin/streptomycin (REF: 15070-063) were obtained from Gibco Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) (CAT: FBS002, LOT: N21H21) was obtained from Neuromics, Edima, MN. Cell counting kit-8 (CAT: #DJDB4000X) was from Vita Scientific, college park, MD. The Biotium viability/cytotoxicity assay kit (CAT: 30002-T, LOT: 210811) was from Biotium, Fremont, CA. Polylactic acid and Silicon nitride (CAS; 12033-89-5) were obtained from 3DTech, Grand Rapids, MI, and Chem Savers, Bluefield, VA, respectively. Acetone (CAS: 67641) was obtained from Emplura-Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA. Phosphate buffer saline (PBS; REF: 25-508B; LOT: MS00LB) was from Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA. Human dermal fibroblast cells (HDF, PCS-201-012, LOT #81201212), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) were obtained from ATCC, Manassas, VA. CytoselectTM 24-well cell migration assay, 8 µm, Fluorometric format (CAT: #CBA-101) was obtained from Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA.

Electrodeposition of Magnesium Oxide on HNTs (MgO/HNT)

A platinum-coated titanium mesh electrode electrodeposition consists of two electrodes that operate as a reversible cathode and anode. The electrodes were cleaned using silicon carbide abrasive sandpaper to remove pollution before being ultrasonically sonicated in pure water for 10 minutes. A DC source was linked to the two electrodes spaced two inches apart (20 V). 350 mg of HNT and 141.07 mg of MgO were blended and dispensed into a solution of 700 mL of water at 85°C in the electrolysis vessels. The solution was continually agitated using a magnetic stir bar to promote formation at the working electrode while reducing electrophoretic accumulation. After 5 minutes, the polarity was switched back for 30 minutes (6 cycles). About five minutes were given for the solution to settle before the supernatant was decanted and three times rinsed with deionized water. The solution was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 2000 rpm to eliminate NPs that had not yet reacted to the supernatant. the MgO/HNT were dried at 37 °C.

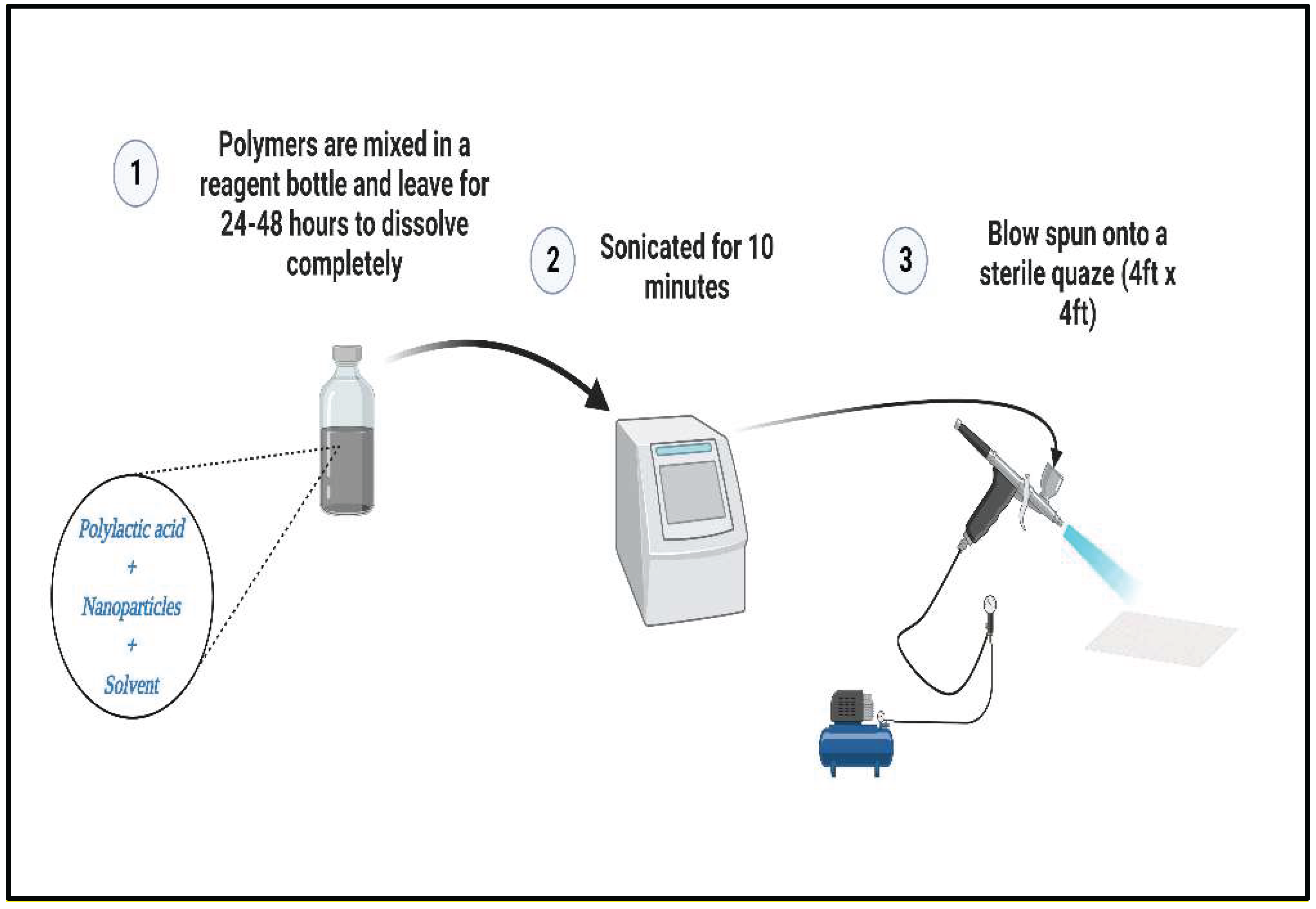

Fabrication of Antimicrobial Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers

Fabrication started with solvent selection based on FDA-approved materials, after which suitable solvents were used. Three compositions were tested in this study: Si

3N

4/PLA, MgO/HNT/PLA, and Si

3N

4MgO/HNT/PLA. The experiment was prepared in two concentrations (25% and 30%), as shown in

Figure 1. For 25% Si

3N

4 MgO/HNT/PLA, 1 g of PLA was added to a blended mixture of 0.150 g of Si

3N

4 and 0.150 g of MgO/HNT in a reagent bottle. The solvent choice was Chloroform and acetone in a 50:50 proportion. Next, 20 mL of the solvent was added to the sample reagent bottle and placed at room temperature for 48 hours to dissolve. The fibers were blown onto a square (4 in X 4 in) sterile gauze using the solution blow spinning technique, after which the gauze was dried at room temperature overnight.

Evaluation of In Vitro Fibroblast Response

Cell Culture and Culture Medium

Cryopreserved cells were purchased from ATCC, thawed, and equilibrated in a water bath. The complete culture media contains an alpha modification of Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic. The medium was filtered with vacuum filtration to remove large particles and contamination. Human dermal fibroblast (HDF) was thawed and cultured in the filtered DMEM complete media and then stored in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 level. Cells were allowed to attain 90-95% confluency and passaged with 0.25% trypsin. Cell culture plates were purchased from Midscientific, St. Louis, MO. Sub-confluent cells were passaged with 2 mL 0.25% Trypsin, centrifuged at 3000 rcf for 3-5 minutes, and resuspended in 2 mL of media.

Sample Conditioning

After being sterilized by UV light, 163 mg–165 mg of blown-spun nanocomposite fibers was extracted by conditioning in 5 mL of DMEM complete media for 72 hours at 37°C. 5 mL of fresh DMEM complete medium was added to the diluted extraction and mixed.

Cell Proliferation Assay Test

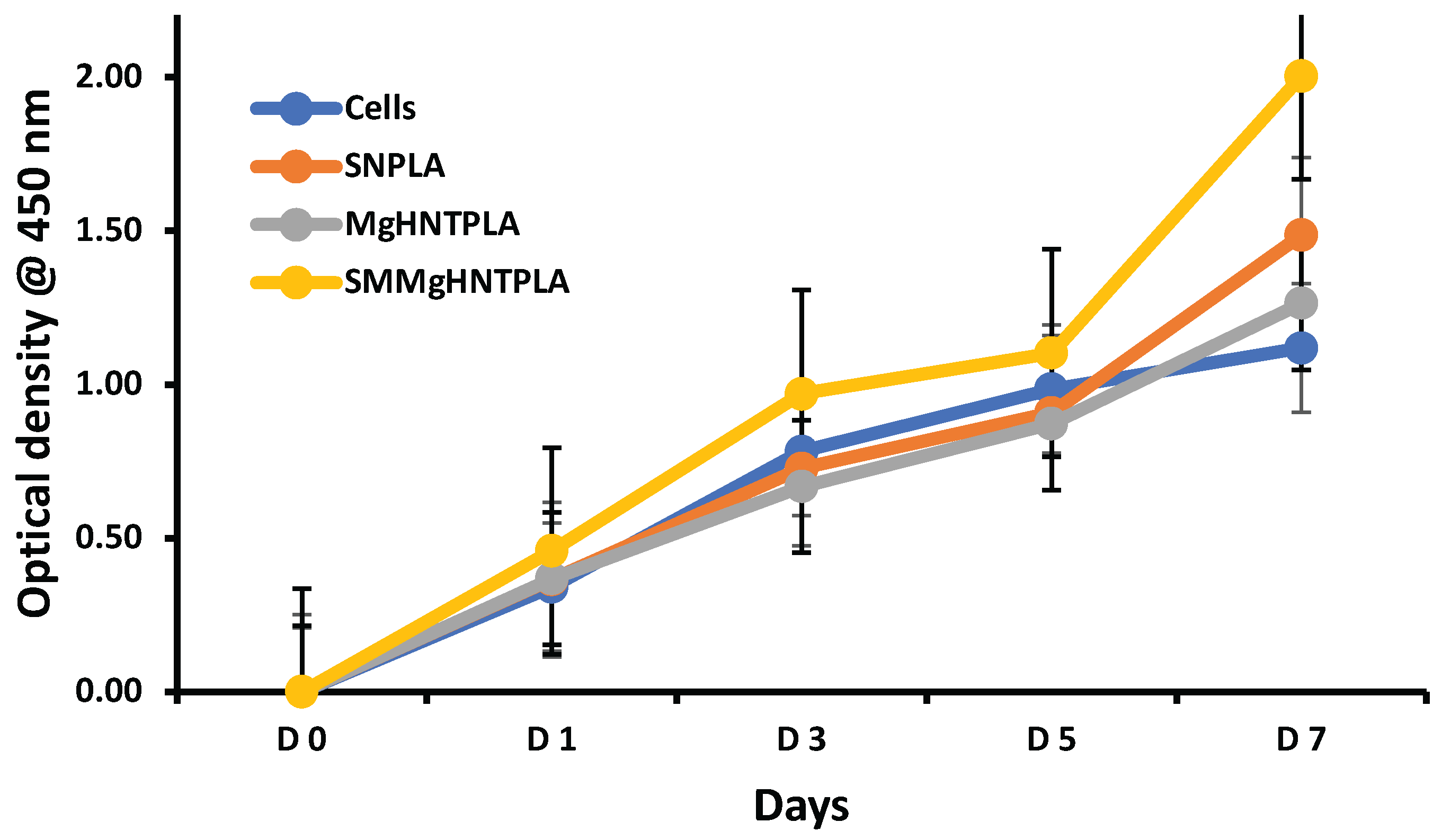

Nexcelon Bioscience Auto T4 Cellometer cell counter was used for cell counting to get 1 X 105 cells/well. The conditioned nanocomposite fibers were inoculated with 100 µL/well cell suspension (1 X 105 cells/well) in a 96-well cell culture plate and incubated at 37°C until attaining confluence. After attaining confluence, the Cell counting kit-8 reagent (Vita scientific, Cat #DJDB4000X) was thawed, and 1/10 µL/well of total cells was added to the cell culture plate for “x” day and incubated at 37°C for 1-4 hours. BioTek Instruments, Inc., REF 800TS microplate reader was used to record the optical density (OD) at 450 nm. “x” was day 1, 3, 5, and Cytotoxicity Testing

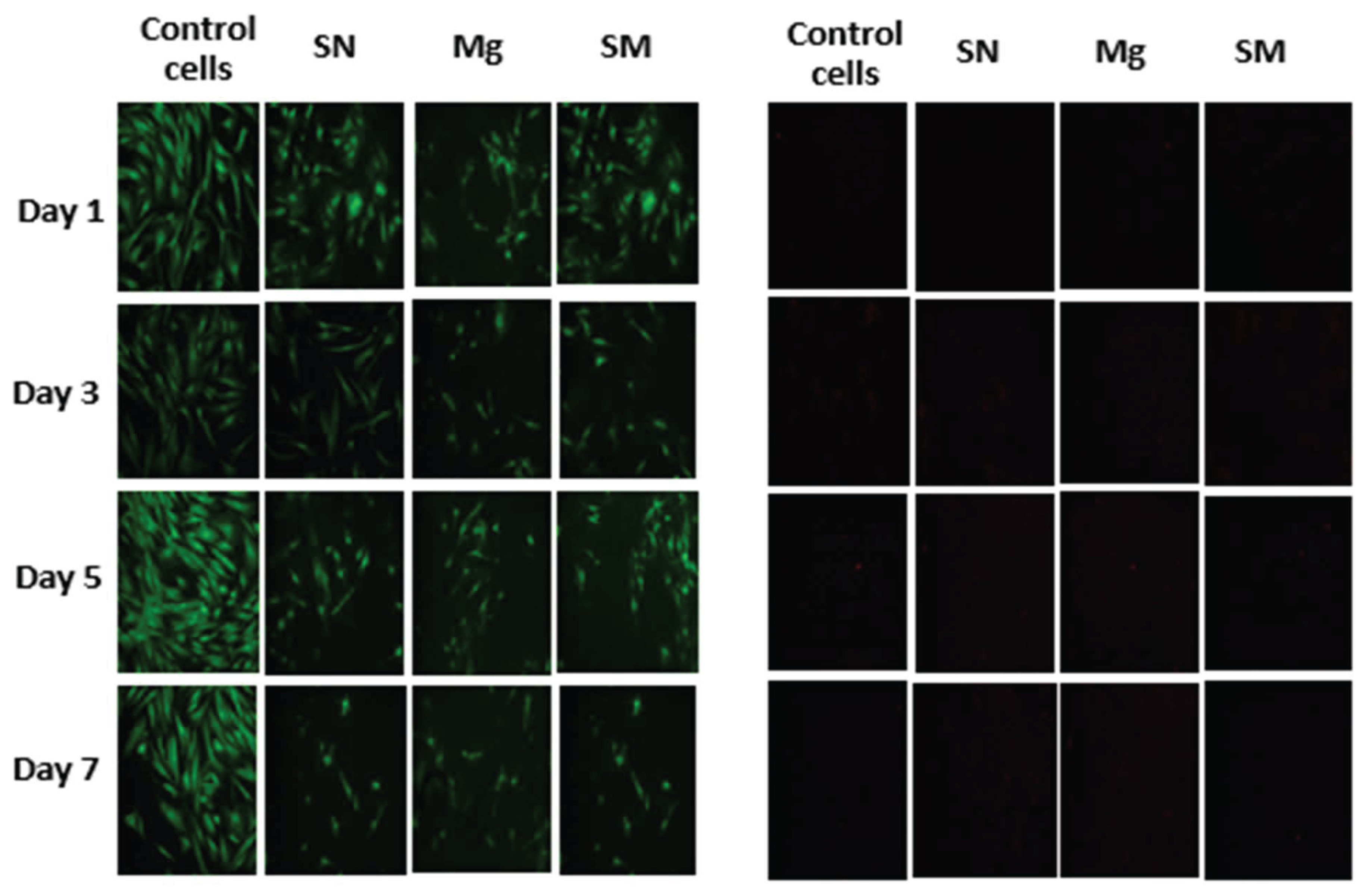

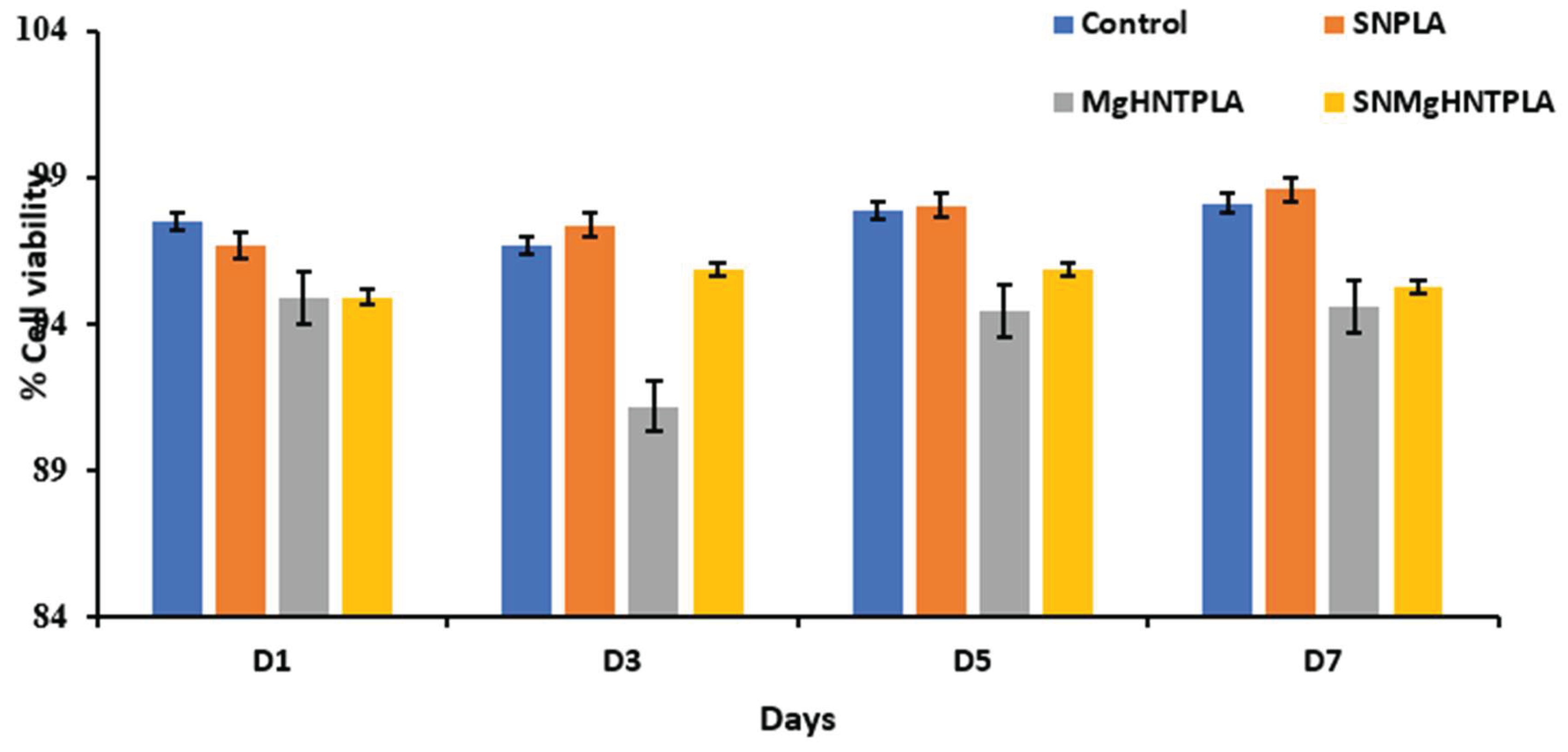

Assessing the combined cytotoxicity of Si3N4, MgO, and HNT on biological cells is crucial. After being exposed to human dermal fibroblast cell culture (500 µL of cell/well), the conditioned nanocomposite blow-spun fibers were subjected to a live/dead experiment to determine the cell viability using the biotium viability/cytotoxicity assay kit (Cat: 30002-T, Lot:210811) in a 24- well plate to attain 90-95% confluency in a 37°C incubator. After attaining confluence, the Cells were washed with 300 µL PBS twice before staining with the biotium solution and then incubated at room temperature for 30-45 minutes. Cytotoxicity was assessed on day 1, 3, 5, and 7 while utilizing Image J for live and dead counting.

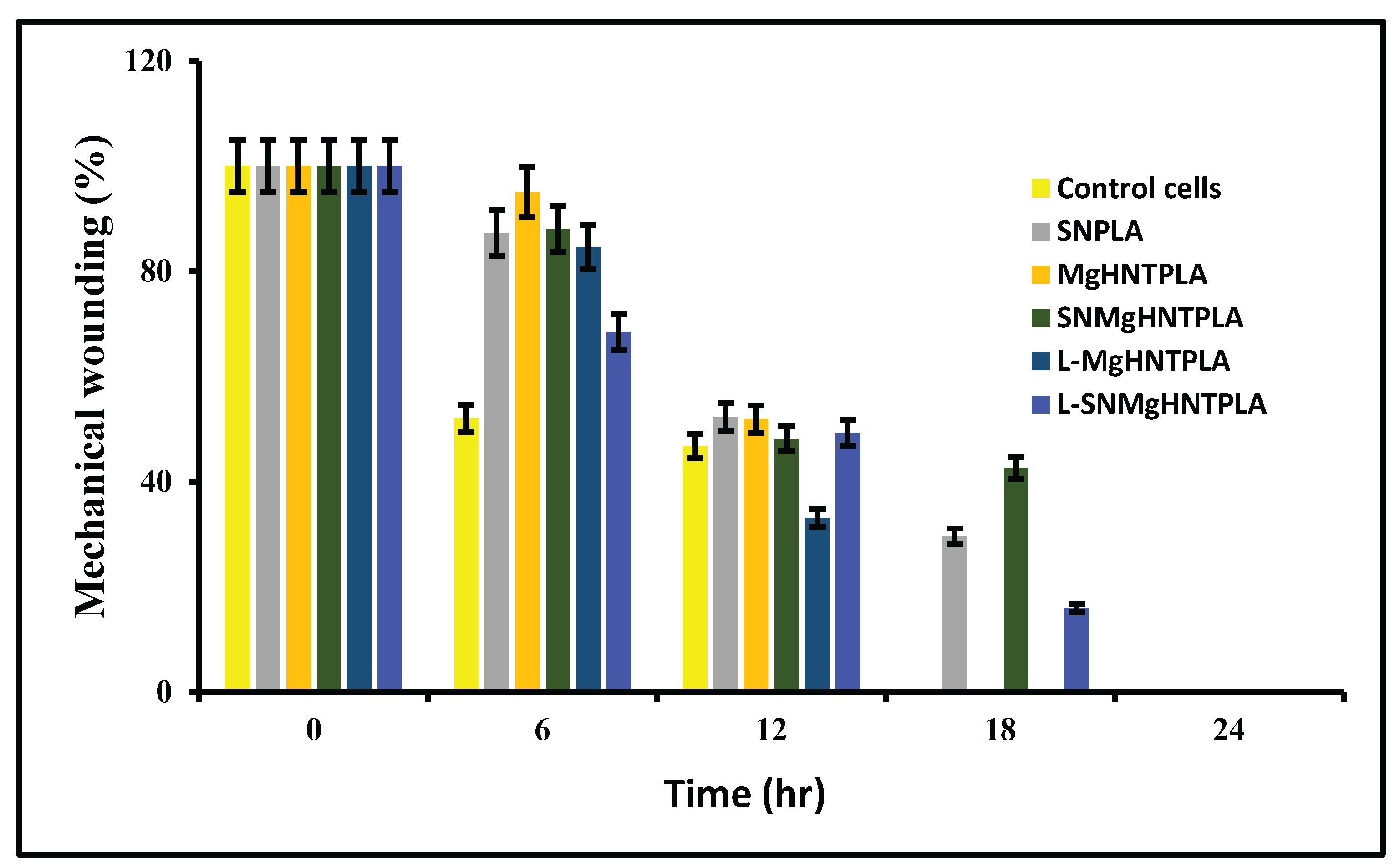

Scratch Assay

The scratch assay is a mechanical wounding assay used to analyze in vitro cell migration and measures three essential parameters: speed of migration, persistence, and polarity of migration. First, cells were counted and seeded in a 24-well, and after the cells had attained confluency, a scratch was introduced with a sterilized 200 µL pipette tip. After the wounding step, how the cell behaves and moves to the wounded part was recorded and analyzed every 6 hours for a total of 24 hours. The % wound area was calculated using

Equation 1.

Where:

Wo: measurement of wound area after creating a scratch,

Wt: measurement of wound area at time t.

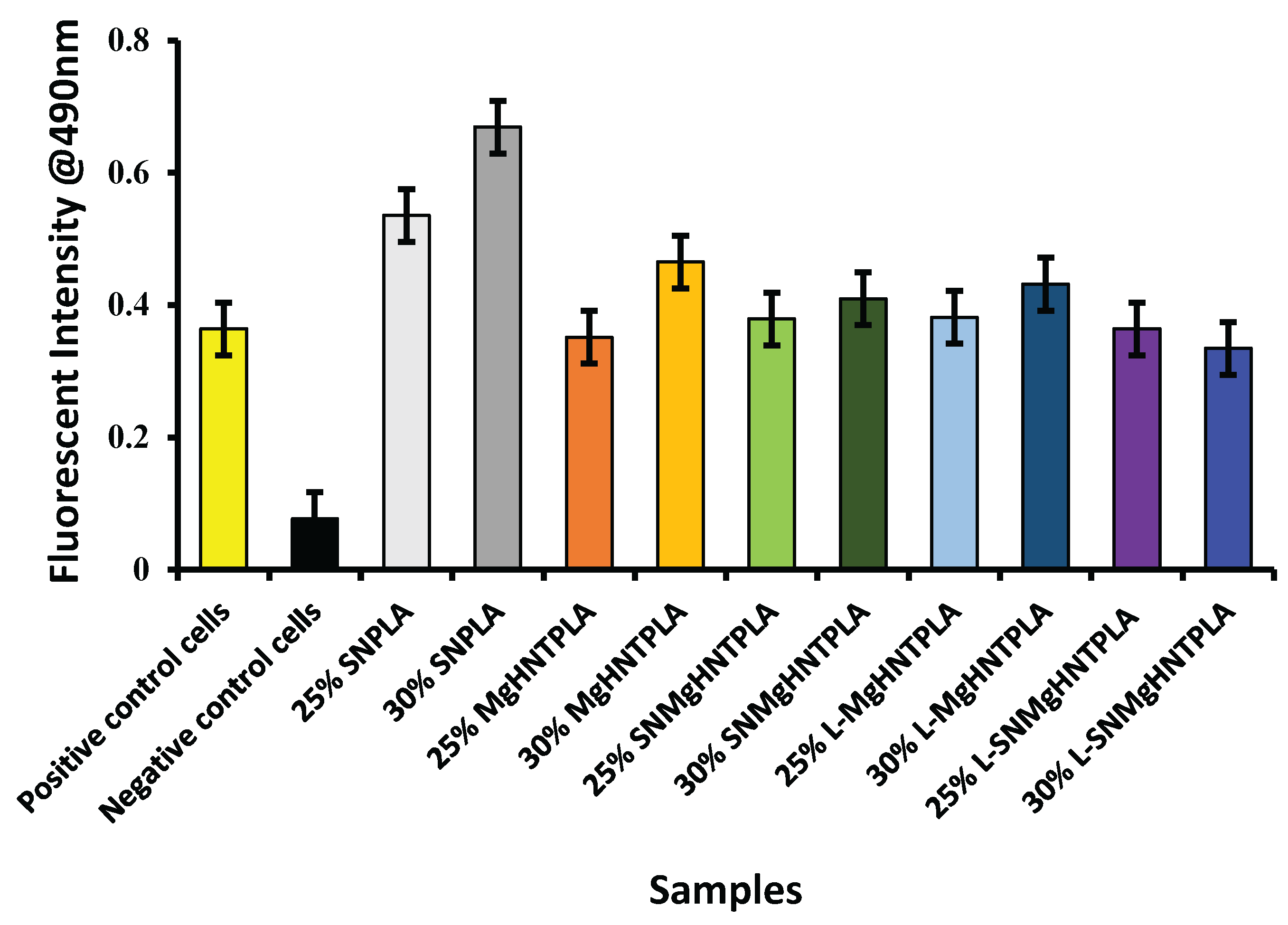

Migration Assay

The migratory pattern assay identified the HDF cell’s ability to migrate toward the conditioned samples (acts as a chemoattractant). 300 µL of 1.0X 106 cells/mL in serum-free media was added to the inside of the insert while 500 µL of conditioned samples were added to the lower well of the migration plate and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 level. Media were aspirated from the inside of the insert, then transferred to a well with 225 µL cell detachment solution and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The cells were dislodged from the underside of the membrane in the detachment solution and stained with 4X Lysis buffer/CyQuant®GR dye solution for 20 minutes at room temperature. Fluorescence was recorded with a fluorescence plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., REF 800TS) set at 490 nm.

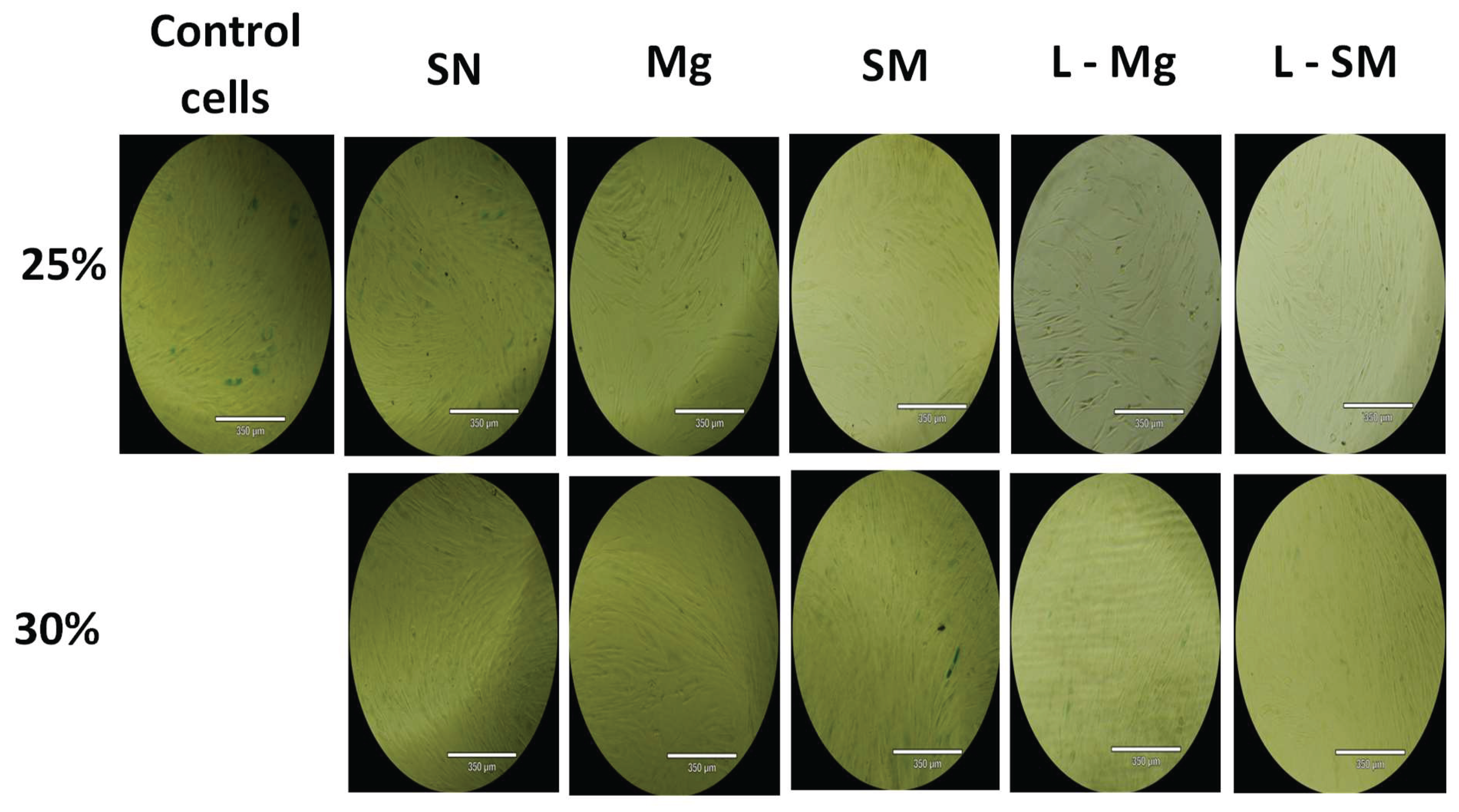

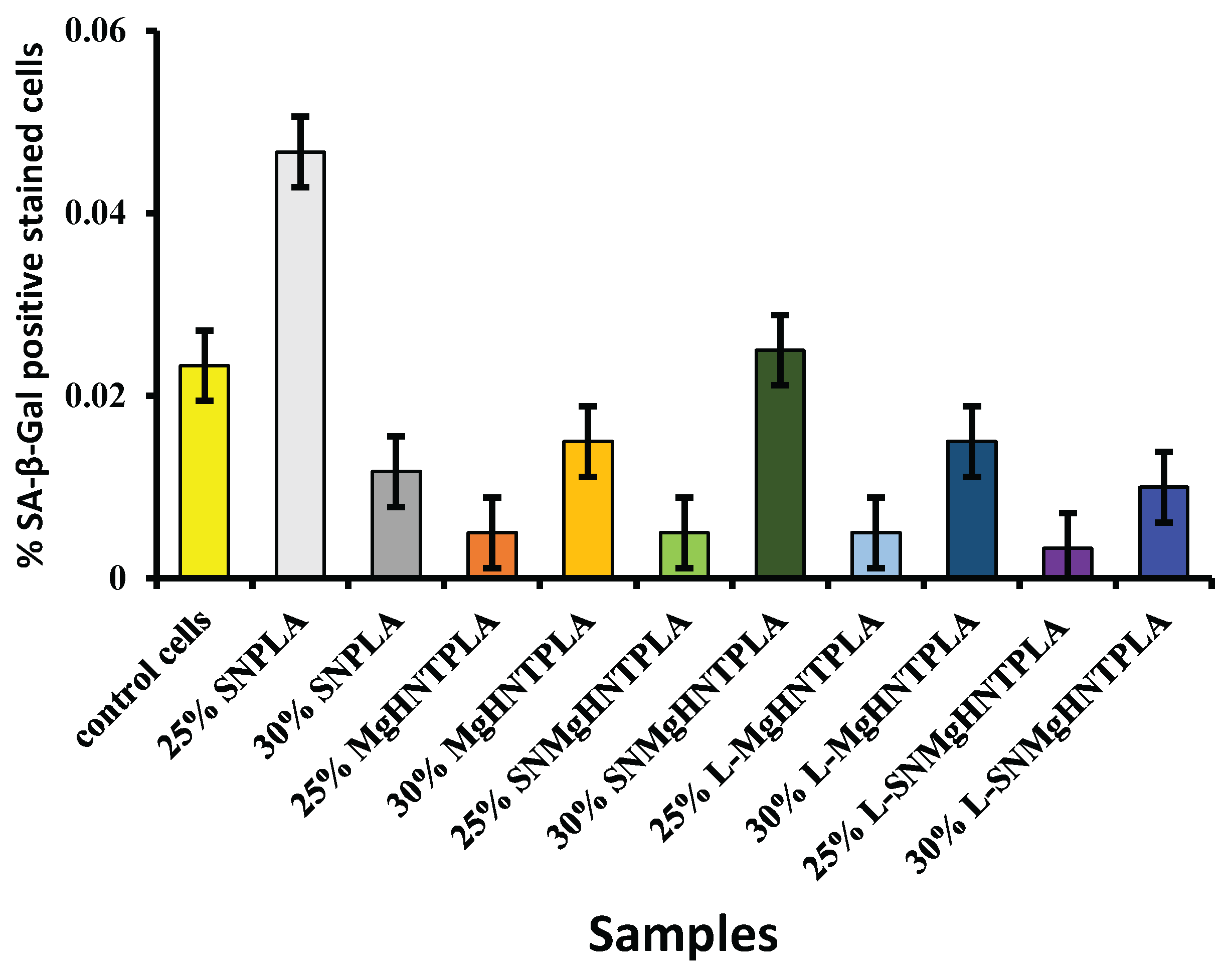

β-Galactosidase Staining

According to the manufacturer's protocol, a senescence cell histochemical staining kit (Sigma-Aldrich Cat. #CS0030-1KT) was used to measure the expression of β-galactosidase. Culturing human dermal fibroblast cells in the presence of conditioned nanocomposite fibers was followed by their fixation in 1X fixation buffer at room temperature for 6-7 minutes, staining the cells with the staining solution, and incubating the cells at 37°C overnight. The proportion of senescent cells (the fraction of cells expressing -galactosidase) was determined using the ratio of blue-stained cells.

Discussion

The most widely used wound healing material, plain gauze in wound dressing, tends to coagulate and reduce bleeding without advancing the wound healing process [

37]. A hemorrhage is a critical cause of civilian and military casualties. The human body’s hemostatic mechanism is a complex process with a limited capacity [

38]. In critical emergencies, the human hemostatic mechanism cannot stop bleeding effectively, and hemostatic materials are needed to save lives. The most commonly used hemostatic materials (including fibrin, collagen, zeolite, gelatin, alginate, chitosan, cellulose, and cyanoacrylate) and commercial wound dressings[

40].

The Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC) has recently recommended QuickClot combat gauze® (QCG), a material containing either Kaolin or Zeolite – to control bleeding in the military [

39]. Hematrix® an active-patch wound dressing for immediate hemostasis, is another widely used hemostatic material. These materials may have limitations, such as poor tissue adhesion, infection risk, exothermic reactions, and no regenerative capability that may lessen their efficacy and cause secondary injuries [

38,

40]. Therefore, there is a need to improve the current wound healing capability by incorporating additional properties needed for wound healing, eliminating infection without using drugs, enhancing trauma site recovery, tissue regenerative, and drug release capability. Multifunctional bandages (antimicrobial, pain relief, and regenerative) could be effective for wound repair and regeneration.

Halloysite has been studied as a delivery vehicle for wound healing applications [

41,

32]. Halloysite coupled with antimicrobial metals such as gold [

43], silver [

44] and zinc [

45]. Halloysite and chitosan have been studied for their antimicrobial and hemostatic capability [

46]. Chitosan’s inherent antimicrobial property [

46] was combined with halloysite ability as an absorbent to create antimicrobial and hemostatic bandages [

47,48] and often combined with various drugs to enhance the bandages efficacy [

41,

42,49].

This research aimed to produce novel gauze dressing using commercial gauze (with large openings) as the base material, with advanced nanocomposites, adding additional functionalities to current wound dressings.

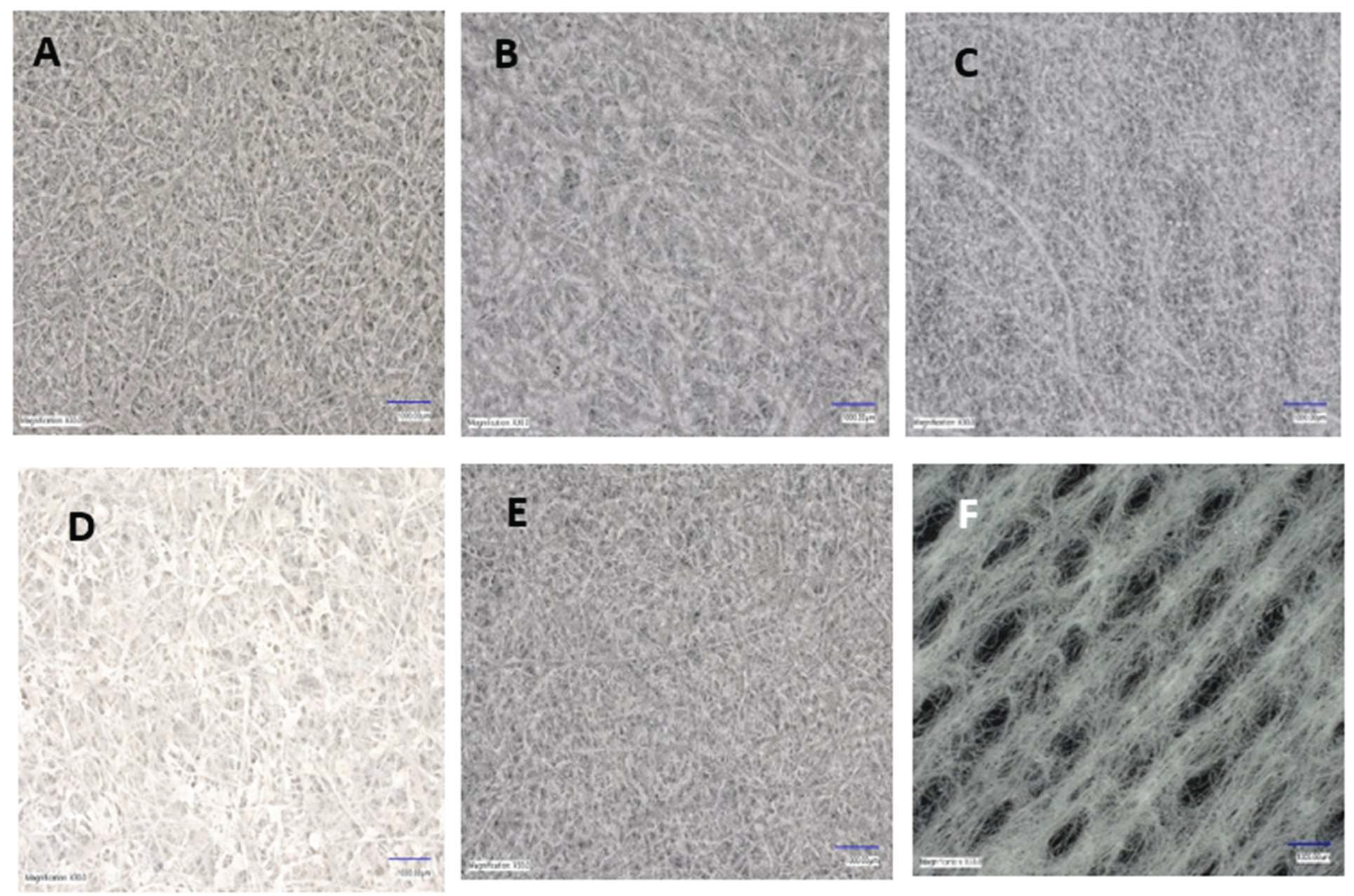

Figure 2 shows plain gauze having a large opening and lacking good coagulation capability.

Here, our approach in fabricating an antimicrobial and tissue regenerative bandage was through the combination of MgO/HNTs doped with gentamicin and included in solution spun fibers. FDA-approved materials like PLA, Si3N4, MgO, HNT, and suitable solvents were used to fabricate nanocomposite fibers. HNT is a clay material, just like Kaolin or Zeolite. Therefore, the solvents used in dissolving the polymers required for fabrication are an essential part of the fabrication process. Since chloroform/acetone in the ratio 45:55 does not dissolve the polymers completely, there was a need to make the ratio equal, that is, a 50:50 ratio. Fortunately, chloroform or dichloromethane evaporates after 24 hours, leaving the acetone. As stated earlier, the high evaporation rate in SBS is one of the advantages over other spinning techniques.

Cell proliferation is essential in the treatment of wounds. The proliferation assay on the nanocomposite fibers indicated that all nanocomposite fibers proliferated well, especially the Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA and Si3N4PLA, due to the presence of Si3N4, making them proliferate better than the control cells and other nanocomposites fibers without Si3N4. Wound dressing must not be toxic to cells because cell growth is essential in treating wounds. Furthermore, the cytotoxicity tests showed that the nanocomposite fibers were not toxic, making their application in wound healing viable.

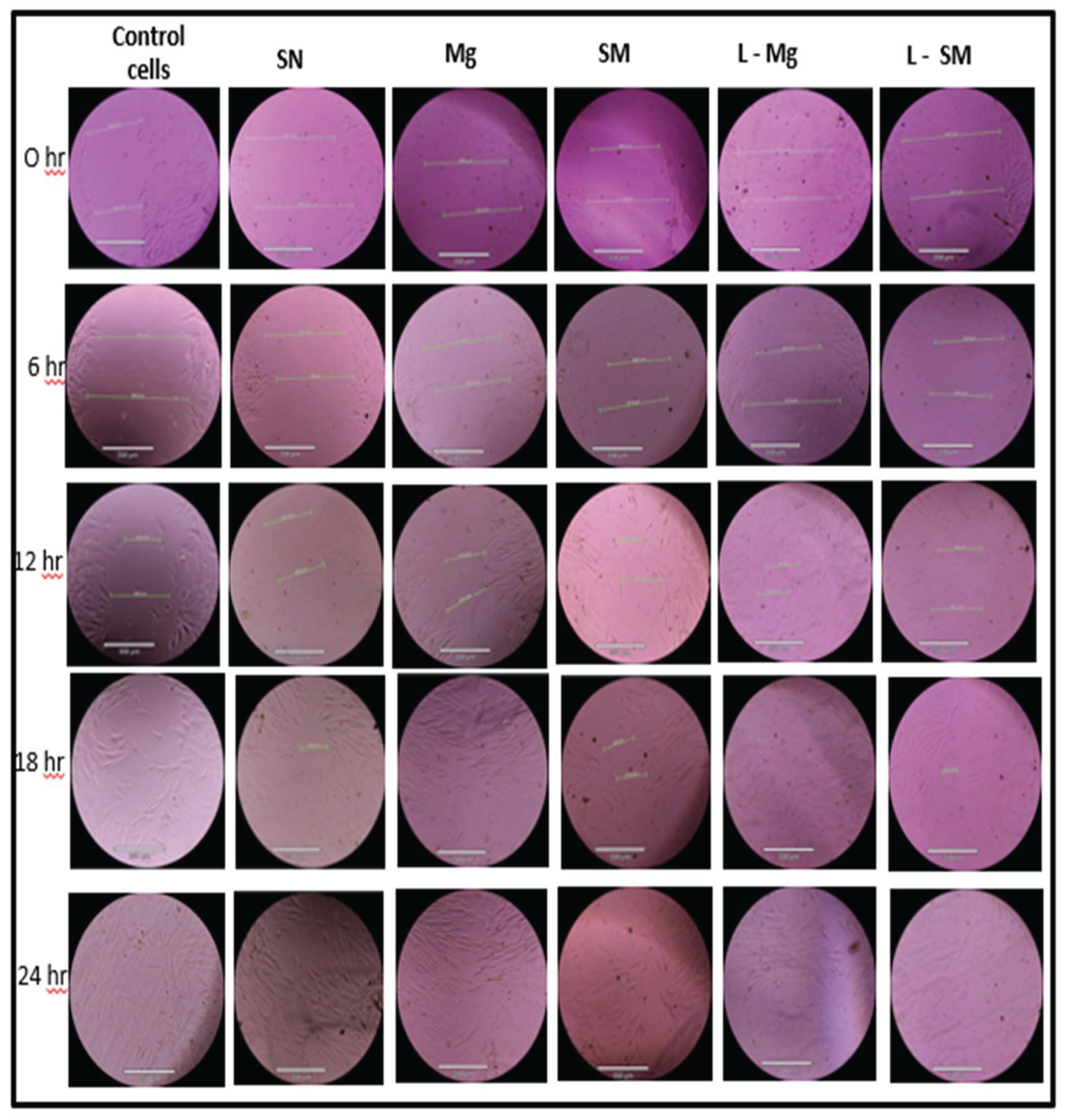

Since cytotoxicity and the proliferation rate has been established, it is essential to know how the nanocomposite fibers will behave in vitro. The mechanical wounding process, also known as the scratch assay in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, shows that the cells in the wounded part migrated toward the gap in the presence of the nanocomposite fibers. It was discovered that 30% of gentamicin-loaded MgO/HNT/PLA fibers saw cells migrated and covered the wounded surface within 18 hours, while all other 30% nanocomposites covered the wounded surface by 24 hours. However, the control cells, 25% MgO/HNT/PLA, and 25% gentamicin-loaded MgO/HNT/PLA fibers were also covered in 18 hours, but all other 25% nanocomposite fibers were covered in 24 hours.

The nanocomposite fibers were used as a chemoattractant in the migration assay to determine how the cells would migrate toward the nanocomposites.

Figure 10 showed that all nanocomposite fibers had increased cell migration. Similarly, the phase contrast images of β-galactosidase-stained human dermal fibroblast cells and their respective percentages were shown in

Figure 11 and Figure 12, indicating that all 25% nanocomposite fibers showed a low percentage of positive SA-β-galactosidase cells around 0.005% and below while the control cells also showing low signs of senescence but higher than the 25% nanocomposite fibers.

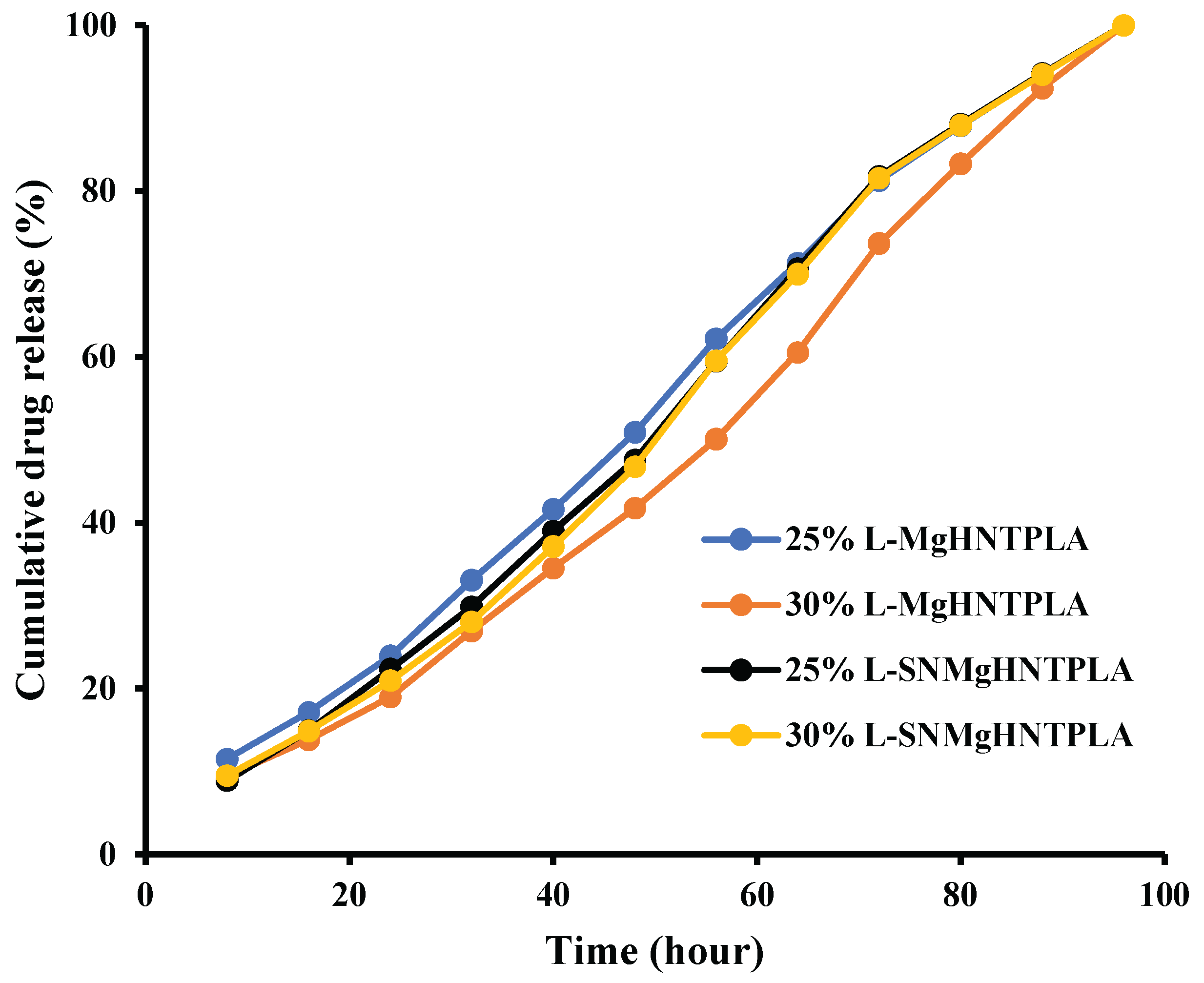

The drug delivery capability is one of the improved properties expected in the nanocomposites incorporated in wound dressing. Therefore, gentamicin was loaded into the nanocomposite fibers by vacuum entrapment method and subjected to an in vitro drug release study in the presence of PBS. The results shown in

Figure 13 indicated that most nanocomposites released the drug at a more stable and constant rate.

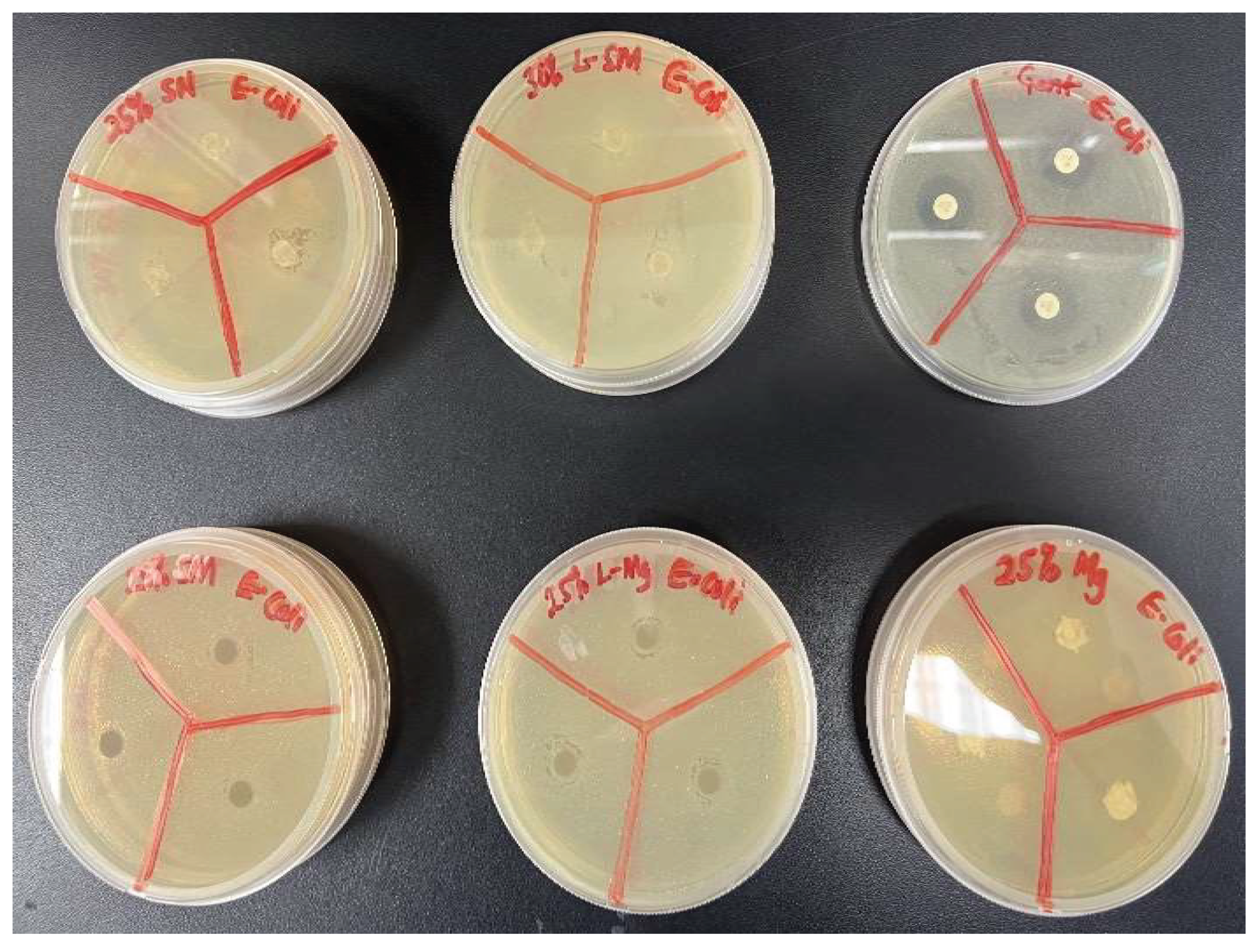

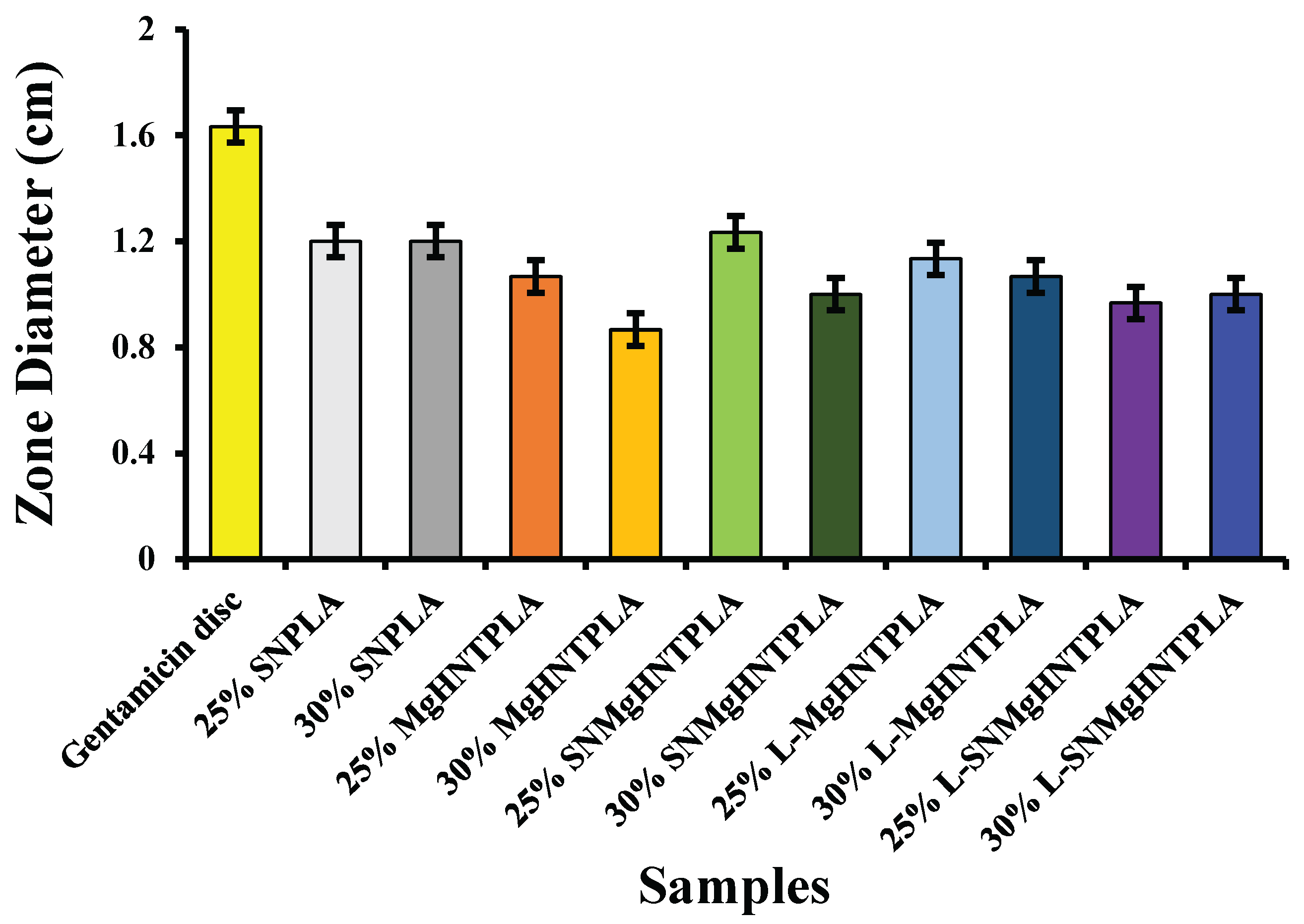

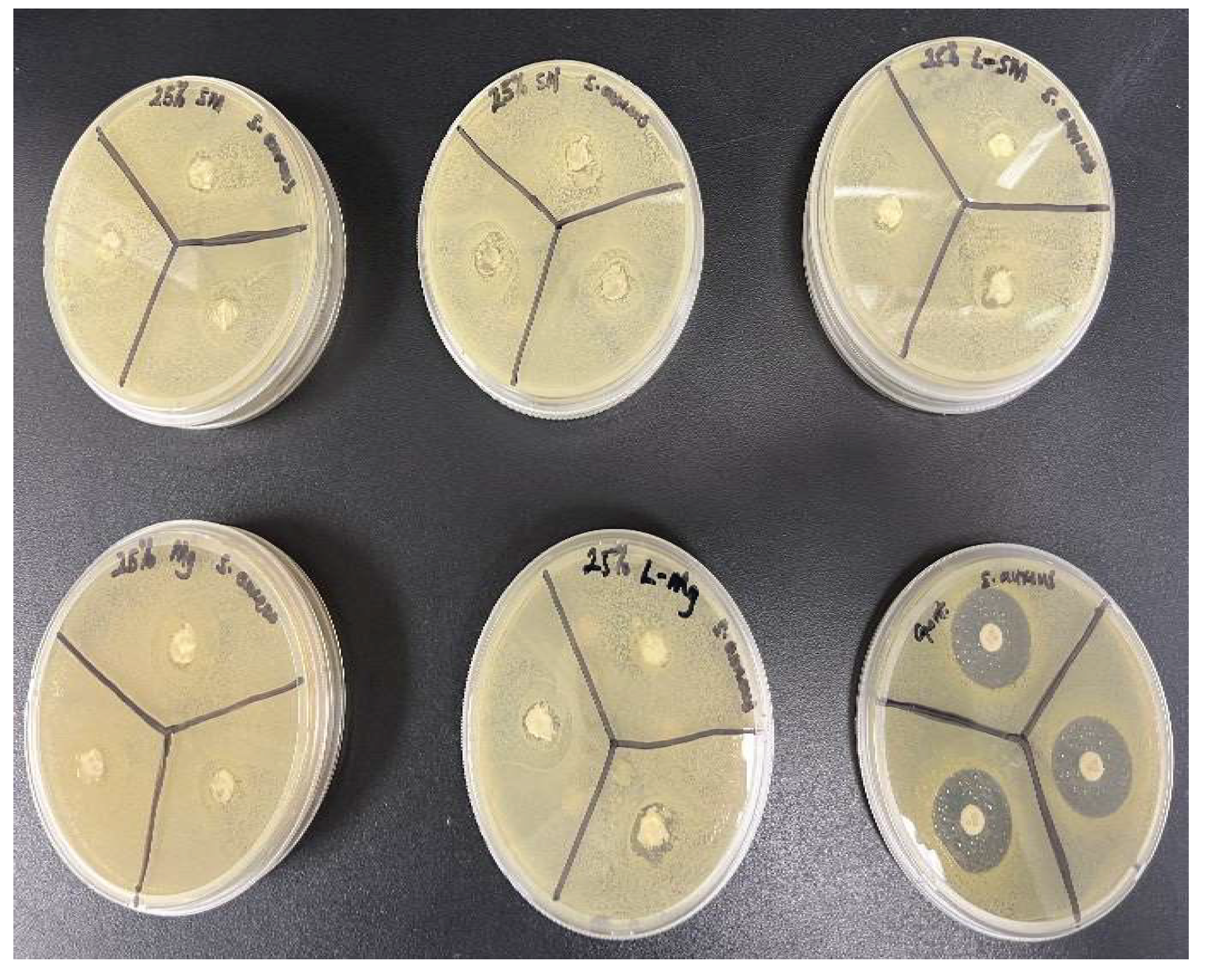

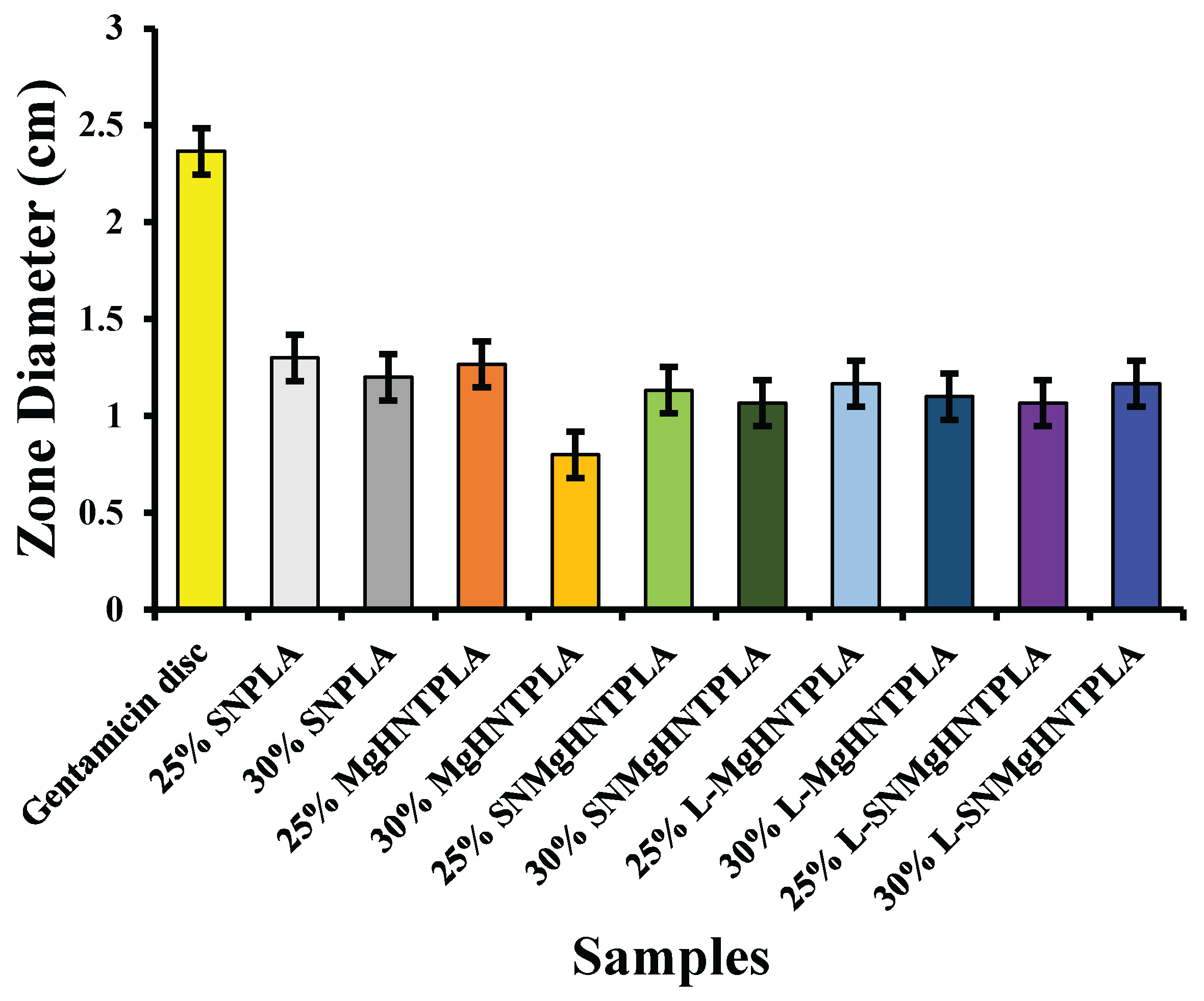

Antimicrobial activities of the nanocomposite fibers suppressed bacterial growth at a lower rate within 24 hours when tested against

E. coli and

S. aureus. However, the gentamicin reference disc performed excellently in suppressing bacterial growth. The analysis of the bacteria test shown in

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16, and

Figure 17 showed how the reference disc performed better. All nanocomposite fibers performed similarly against

E. coli and

S. aureus except 30% MgO/HNTPLA which performed less.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrating the fiber fabrication process. (Figure created through BioRender.com).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustrating the fiber fabrication process. (Figure created through BioRender.com).

Figure 2.

Digital microscope images of surface morphology of (A) 25% Si3N4/PLA Fiber (B) 30% Si3N4/PLA Fiber (C) 25% Si3N4/MgHNT/PLA Fiber (D) 25% MgHNT/PLA Fiber (E) 30% Si3N4/MgHNT/PLA Fiber (F) plain gauze lacking inclusion of the nanocomposite.

Figure 2.

Digital microscope images of surface morphology of (A) 25% Si3N4/PLA Fiber (B) 30% Si3N4/PLA Fiber (C) 25% Si3N4/MgHNT/PLA Fiber (D) 25% MgHNT/PLA Fiber (E) 30% Si3N4/MgHNT/PLA Fiber (F) plain gauze lacking inclusion of the nanocomposite.

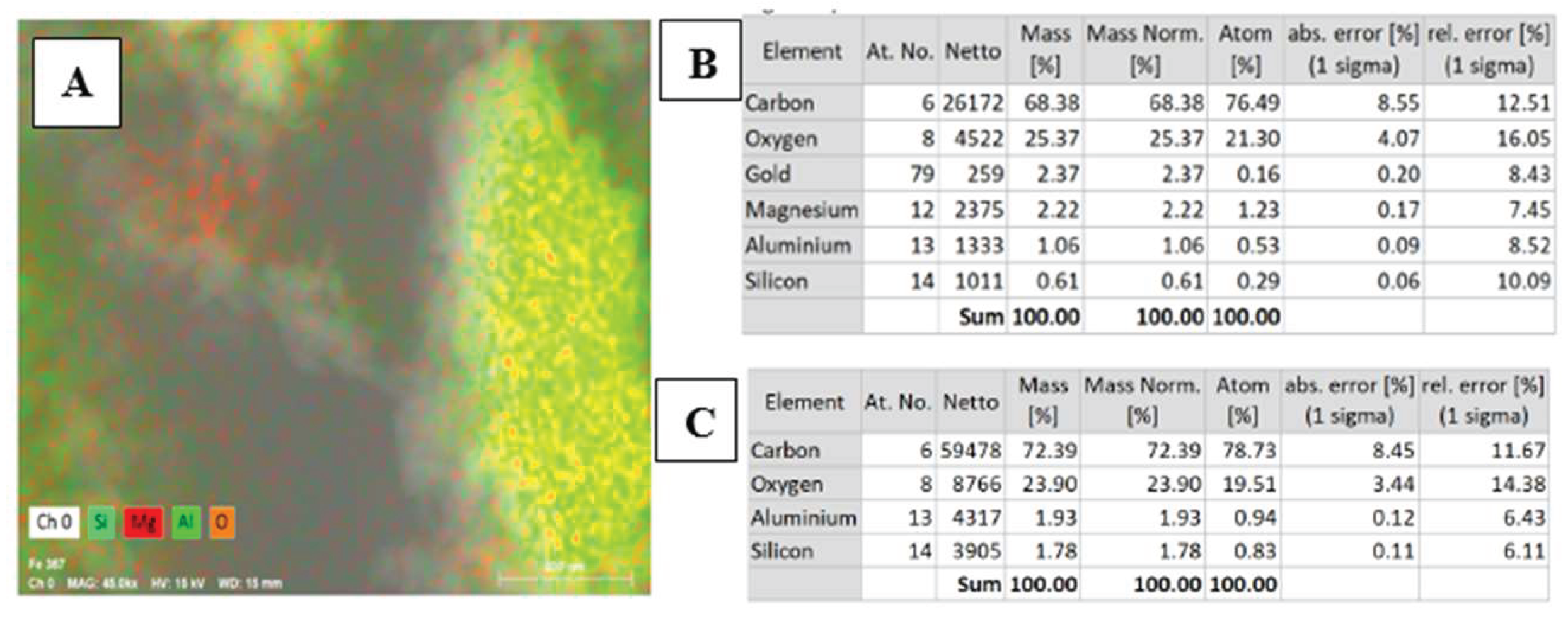

Figure 3.

(A) Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy Scan (B) Chemical element analysis of MgO/HNT confirming the presence of Mg. (C) Chemical element analysis of HNT confirming the absence of Mg. .

Figure 3.

(A) Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy Scan (B) Chemical element analysis of MgO/HNT confirming the presence of Mg. (C) Chemical element analysis of HNT confirming the absence of Mg. .

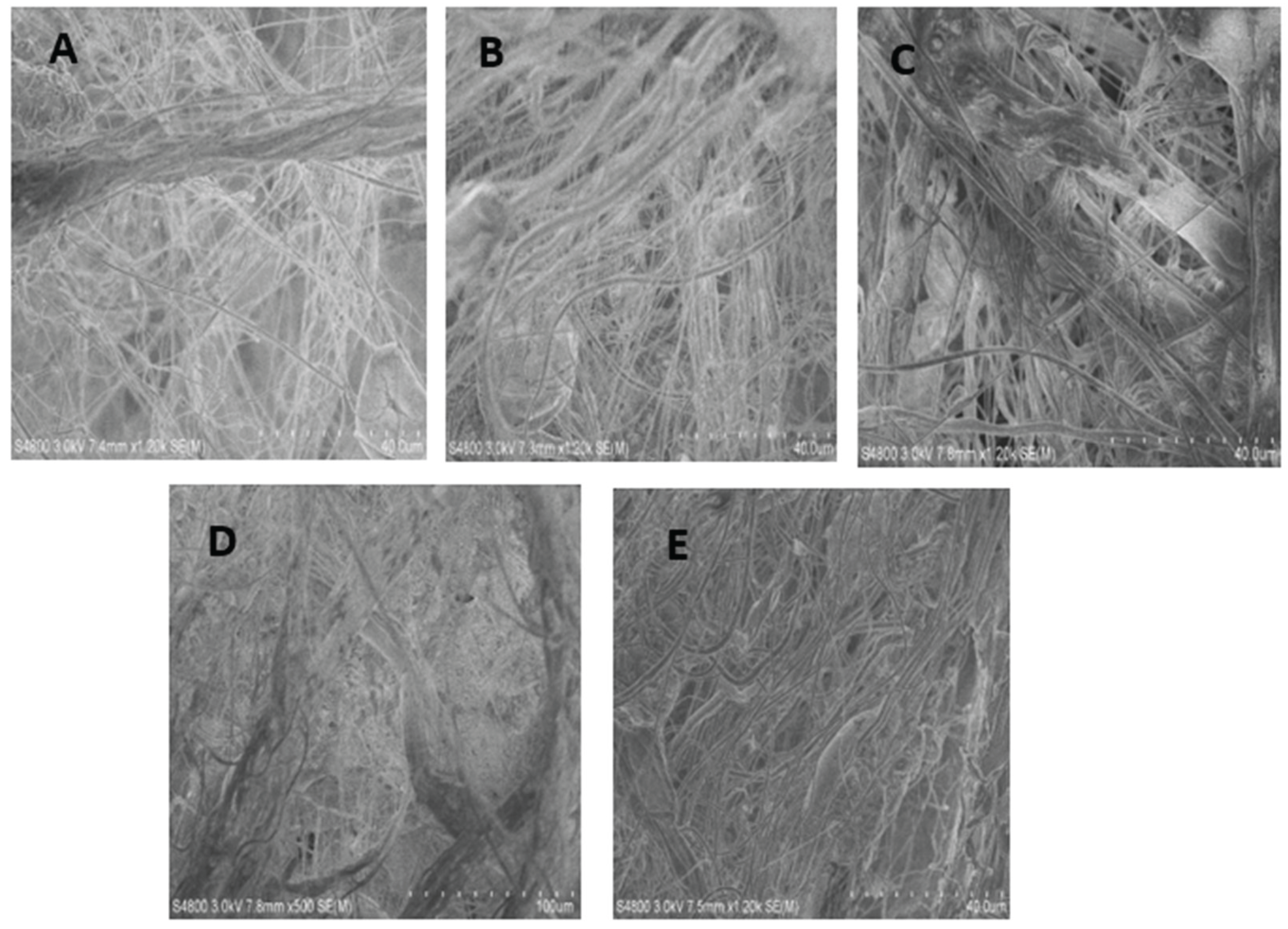

Figure 4.

SEM images of surface morphology of (A) 25% Si3N4/PLA Fiber (B) 25% MgHNT/PLA Fiber (C) 25% Si3N4/MgHNT/PLA Fiber (D) 30% Si3N4/PLA Fiber (E) 30% Si3N4/MgHNT/PLA Fiber.

Figure 4.

SEM images of surface morphology of (A) 25% Si3N4/PLA Fiber (B) 25% MgHNT/PLA Fiber (C) 25% Si3N4/MgHNT/PLA Fiber (D) 30% Si3N4/PLA Fiber (E) 30% Si3N4/MgHNT/PLA Fiber.

Figure 5.

Proliferation assay of blow spun nanocomposite fiber after exposure to human Dermal Fibroblast for 7 days. The Blue Line Signified Control Cells. Yellow, Orange, and Grey Lines Signify Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA, Si3N4/PLA, and MgO/HNT/PLA, respectively. Error bars are standard deviations, where n = 3.

Figure 5.

Proliferation assay of blow spun nanocomposite fiber after exposure to human Dermal Fibroblast for 7 days. The Blue Line Signified Control Cells. Yellow, Orange, and Grey Lines Signify Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA, Si3N4/PLA, and MgO/HNT/PLA, respectively. Error bars are standard deviations, where n = 3.

Figure 6.

Images of Cytotoxicity Test (Live/Dead Assay) with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cell of Blow Spun Nanocomposite Fibers. Live Cells in Green (Left Image) and Dead Cells in Red or Black Indicate no Dead Cell (Right Image) for Day 1, 3, 5, and 7; SN = Si3N4/PLA, Mg = MgO/HNT/PLA, SM = Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA.

Figure 6.

Images of Cytotoxicity Test (Live/Dead Assay) with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cell of Blow Spun Nanocomposite Fibers. Live Cells in Green (Left Image) and Dead Cells in Red or Black Indicate no Dead Cell (Right Image) for Day 1, 3, 5, and 7; SN = Si3N4/PLA, Mg = MgO/HNT/PLA, SM = Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA.

Figure 7.

Viability on Blow Spun Nanocomposite Fibers Showing Quantitative Cell Count Value Calculated (Live Cells/Total Cell Count). Error Bars are Standard Deviations, where n = 3.

Figure 7.

Viability on Blow Spun Nanocomposite Fibers Showing Quantitative Cell Count Value Calculated (Live Cells/Total Cell Count). Error Bars are Standard Deviations, where n = 3.

Figure 8.

Scratch assay quantification of blow-spun nanocomposite fibers. Error Bars are standard deviations where n = 3.

Figure 8.

Scratch assay quantification of blow-spun nanocomposite fibers. Error Bars are standard deviations where n = 3.

Figure 9.

Images of Mechanical Wound Assay (Scratch Assay) with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cell of Blow Spun Nanocomposite Fibers for 0 hour, 6 hour, 12 hour, 18 hour, and 24 hour. Control Cells are without the Nanocomposites, SN = Si3N4/PLA, Mg = MgO/HNT/PLA, SM = Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA, L-Mg = Gentamicin Loaded MgO/HNT/PLA, and L-SM = Gentamicin Loaded Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA.

Figure 9.

Images of Mechanical Wound Assay (Scratch Assay) with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cell of Blow Spun Nanocomposite Fibers for 0 hour, 6 hour, 12 hour, 18 hour, and 24 hour. Control Cells are without the Nanocomposites, SN = Si3N4/PLA, Mg = MgO/HNT/PLA, SM = Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA, L-Mg = Gentamicin Loaded MgO/HNT/PLA, and L-SM = Gentamicin Loaded Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA.

Figure 10.

Graphical Representation of Cell Migration Assay of Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cells. Error Bars are Standard Deviations, where n = 3.

Figure 10.

Graphical Representation of Cell Migration Assay of Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cells. Error Bars are Standard Deviations, where n = 3.

Figure 11.

Images of β-Galactosidase Test with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cell of 25% and 30% Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers. Control Cells are without the Nanocomposites, SN = Si3N4/PLA, Mg = MgO/HNT/PLA, SM = Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA, L-Mg = Gentamicin Loaded MgO/HNT/PLA, and L-SM = Gentamicin Loaded Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA.

Figure 11.

Images of β-Galactosidase Test with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cell of 25% and 30% Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers. Control Cells are without the Nanocomposites, SN = Si3N4/PLA, Mg = MgO/HNT/PLA, SM = Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA, L-Mg = Gentamicin Loaded MgO/HNT/PLA, and L-SM = Gentamicin Loaded Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA.

Figure 12.

Graphical representation of % SA-β-Gal Positive Stained Cells of Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cells. Error Bars are Standard Deviations, where n = 3.

Figure 12.

Graphical representation of % SA-β-Gal Positive Stained Cells of Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers with Human Dermal Fibroblast Cells. Error Bars are Standard Deviations, where n = 3.

Figure 13.

In Vitro Cumulative Release of Gentamicin from Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers to PBS Buffer Solution at 37°C.

Figure 13.

In Vitro Cumulative Release of Gentamicin from Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers to PBS Buffer Solution at 37°C.

Figure 14.

Image of Bacteria Culture Plates, with E. coli and (A) Si3N4/PLA Fiber (B) L-S3iN4MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (C) Gentamicin Standard Disc (D) Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (E) L-MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (F) MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber.

Figure 14.

Image of Bacteria Culture Plates, with E. coli and (A) Si3N4/PLA Fiber (B) L-S3iN4MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (C) Gentamicin Standard Disc (D) Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (E) L-MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (F) MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber.

Figure 15.

Graphical Representation of Zone Diffusion Assay of Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers Against E. coli. Error Bars are Standard Deviations where n = 3.

Figure 15.

Graphical Representation of Zone Diffusion Assay of Blow-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers Against E. coli. Error Bars are Standard Deviations where n = 3.

Figure 16.

Image of bacteria culture plates, with S. aureus and (A) Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (B) Si3N4/PLA Fiber (C) L-Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (D) MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (E) L-MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (F) Gentamicin standard disc.

Figure 16.

Image of bacteria culture plates, with S. aureus and (A) Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (B) Si3N4/PLA Fiber (C) L-Si3N4MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (D) MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (E) L-MgO/HNT/PLA Fiber (F) Gentamicin standard disc.

Figure 17.

Graphical Representation of Zone Diffusion Assay of Blow-Spun Nanocomposite against S. aureus. Error Bars are Standard Deviations, where n = 3.

Figure 17.

Graphical Representation of Zone Diffusion Assay of Blow-Spun Nanocomposite against S. aureus. Error Bars are Standard Deviations, where n = 3.

Table 1.

Solvent Selection Reaction.

Table 1.

Solvent Selection Reaction.

| Solvents

|

|

Reactions

|

|

| Acetone |

|

Did not dissolve. |

|

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) |

|

Did not dissolve. |

|

Toluene

Methyl ethyl ketone

Chloroform

Dichloromethane

20%:80% Chloroform/acetone

80%:20% Chloroform/acetone

50%:50% Chloroform/acetone

45%:55% Chloroform/acetone |

|

Did not dissolve.

Did not dissolve.

Dissolved overnight.

Dissolved overnight.

Did not dissolve.

Dissolved in 48 hours.

Dissolved in 48 hours.

Did not completely dissolve. |

|