1. Introduction

Açaí

(Euterpe oleracea Mart.) is a palm tree native to the floodplains of Central and South America, with widespread occurrence in the floodplains of the Amazon estuary [

1]. The fruit stands out for its high nutritional value, being rich in lipids, proteins, fibers and anthocyanins [

2]. In addition, it plays a fundamental socioeconomic and environmental role in the producing regions, especially in the state of Pará [

3]. The genus Euterpe comprises approximately 28 species, of which Euterpe oleracea and Euterpe precatoria are the most commercially exploited. While E. precatoria, known as “Açaí-do-Amazonas”, is native to the Western Amazon, E. oleracea, known as “Açaí-do-Pará”, predominates in the floodplain forests of the Amazon River estuary, covering the states of Pará, Amapá, Maranhão, Tocantins, as well as regions of Guyana and Venezuela [

4].

Despite its significant economic and social relevance, the açaí production chain faces major challenges related to the management of the waste generated, especially seeds and husks, which account for 70% to 95% of the total fruit mass [

5]. When improperly disposed of, this waste can cause significant environmental impacts, such as soil and water contamination, the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG) like methane (CH₄) and carbon dioxide (CO₂), as well as threats to local biodiversity [

6]. The state of Pará, which accounts for more than 98% of Brazil's açaí production [

7,

8], is particularly affected by this issue. Currently, the waste is mostly stored in bags and disposed of in open dumps or landfills, reflecting the lack of effective public policies and adequate infrastructure for proper waste management. This situation highlights the urgent need for sustainable alternatives and technologies that enable the recovery and valorization of this environmental liability.

The biomass of açaí seeds exhibits physicochemical characteristics that are favorable for industrial, energy, and environmental applications. Its high calorific value, combined with the significant presence of functional groups such as hydroxyl and carbonyl groups, supports its use in processes such as adsorption, the synthesis of carbon-based materials (graphene and graphite), and thermochemical conversion for energy generation [

9]. Recent studies demonstrate the potential of pyrolysis in transforming this biomass into biofuels (bio-oil, biochar, and syngas), as well as in the production of activated carbon and catalysts for various applications [

10].

Açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) have great potential for bio-oil production through pyrolysis, a thermochemical process that converts lignocellulosic biomass into liquids rich in organic compounds [

11]. Açaí seed bio-oil is obtained by pyrolyzing the seeds, producing a carbon-rich liquid with a high content of aromatic compounds [

12]. This conversion is favored by the high lignin content in the seeds (around 25%), which decomposes at higher temperatures and generates phenolic compounds in the bio-oil [

12,

13]. In addition to being a source of renewable energy, açaí bio-oil may also contain bioactive compounds. In fact, water-soluble extracts from açaí seeds have revealed the presence of phenolic compounds (proanthocyanidins, anthocyanins) with strong antioxidant activity [

14].

The interest in natural antioxidants has been growing due to the search for alternatives to synthetic additives used in food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics [

15]. Natural antioxidants derived from fruits and vegetables, such as the phenolic compounds found in açaí, offer health benefits by neutralizing free radicals and protecting the body from oxidative damage associated with cardiovascular diseases, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, among others [

15]. This demand is driven by the potential of natural compounds to prevent or delay undesirable oxidative processes, both in biological systems and in industrial formulations [

14]. In contrast, common synthetic antioxidants (e.g., BHT, BHA) are effective but present concerns regarding toxicological safety, which motivates research into more biocompatible natural sources [

16]. Consequently, vegetable oils rich in antioxidants, such as those derived from açaí, emerge as a promising natural alternative for the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries [

14]. These bio-oils can contribute to the stabilization of formulations and provide additional therapeutic activity due to their phenolic compounds [

14].

To experimentally verify the antioxidant activity of vegetable bio-oils, in vitro methods such as the DPPH• and ABTS•+ assays are commonly employed. The DPPH method uses the stable free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH•), a nitrogen-based compound with a violet color and absorbance around 515–520 nm [

16]. In the presence of an antioxidant, DPPH• accepts electrons or hydrogen atoms donated by the tested compound, leading to its reduction and a corresponding decrease in spectrophotometric absorbance [

16]. This method is considered fast, simple, accurate, and cost-effective, being suitable for assessing the radical scavenging capacity of complex extracts [

10]. Moreover, due to the commercial stability of the radical, the DPPH• assay is widely used in scientific research and is applied in over 90% of antioxidant activity studies [

17]. Additional advantages include its applicability to compounds soluble in organic solvents and the generation of direct results without the need for additional radical synthesis [

17].

The ABTS•+ assay is based on the generation of the cationic radical of 2,2’-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) [

18]. In this method, the ABTS•+ radical is formed, which exhibits a blue-green coloration. When it reacts with antioxidants, ABTS•+ is reduced, resulting in a loss of color in the solution and a decrease in absorbance [

11]. A key advantage of the ABTS method is its versatility: the ABTS•+ radical can be solubilized in both aqueous and organic media, allowing the evaluation of hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds [

9]. This assay is also fast, stable, and reproducible, offering good solubility and multiple absorption peaks that facilitate measurements [

18]. In summary, both methods monitor the ability of antioxidants present in the bio-oil to capture or neutralize synthetic free radicals, providing a quantitative indicator (e.g., EC₅₀ value or TEAC) of the sample's antioxidant activity [9;16]. It is recommended to use these assays in combination, as each exhibits different sensitivity to specific compounds, ensuring a more comprehensive characterization of the antioxidant potential of the studied matrix [

17].

The confirmation of the antioxidant activity of açaí bio-oil through DPPH and ABTS assays indicates its pharmacological and cosmetic potential [

15]. Phenolic compounds capable of neutralizing free radicals can protect cells against oxidative stress, which is associated with the prevention of inflammatory and degenerative processes [

15]. Moreover, natural antioxidants in cosmetic products contribute to the stabilization of formulations, preventing undesirable oxidation and extending the shelf life of active ingredients [

14]. Therefore, vegetable bio-oils that demonstrate high antioxidant activity tend to be safer and more effective in bioactive applications, as their protective action against free radicals suggests therapeutic potential (anti-inflammatory, anti-aging, etc.) and lower toxicity compared to synthetic additives [

16]. In summary, the use of DPPH and ABTS assays provides initial evidence of efficacy: the significant reduction of these radicals by bio-oils confirms the presence of active antioxidants and supports their quality as natural pharmaceutical or cosmetic ingredients [

9].

In this context, the present study aims to evaluate, at a laboratory scale, the pyrolysis process of açaí seeds, both in their natural form and chemically activated with sodium hydroxide (NaOH 1M). The research seeks to analyze the yields and characteristics of the products generated at different temperatures (350, 400, and 450 °C) under atmospheric pressure, as well as to investigate how operational variables influence process performance. Additionally, the study aims to characterize the liquid fraction (bio-oil) obtained, focusing on the evaluation of its antioxidant activity through ABTS•+ and DPPH• radical scavenging assays. The use of alkaline impregnation with NaOH promotes structural modifications in the biomass, facilitating the depolymerization of components such as lignin and hemicellulose, which favors the release of oxygenated and phenolic compounds during the thermal process [

19,

20]. Therefore, this study aims not only to contribute to the valorization of waste from the açaí production chain but also to promote sustainable technological solutions for the development of bioproducts with industrial potential, adding value to the bioeconomy of the Amazon region.

3. Results

3.1. Drying, Comminution, Sieving and Chemical Impregnation

Table 1 shows the yields obtained in the drying and comminution processes, in addition to the total yield of the pretreatment process carried out in a batch. The biomass showed a reduction in mass from 21 kg to 13.7 kg, resulting in a yield of 65%, which means that 35% of the mass was lost in the form of moisture. The value of 35% moisture in the natura biomass is consistent with data in the literature on lignocellulosic biomass, especially residues from Amazonian fruits, such as açaí seeds, which naturally have a high-water content due to their origin in humid environments. Drying was efficient in removing surface and free moisture, being a fundamental step to improve the thermal efficiency of subsequent processes, such as pyrolysis. The presence of residual moisture in biomass compromises the energy yield, since part of the energy would be consumed in the evaporation of water.

Figure 3 shows the samples obtained after the drying, comminution and sieving steps of the açaí seeds, prepared for the pyrolysis tests. These steps were essential to optimize the performance of the thermochemical process, since the removal of moisture prevents the formation of undesirable by-products, in addition to increasing the surface area of contact, favoring the efficiency of carbonization and ensuring the uniformity of the raw material.

3.2. Physical Characterization of Açaí Seeds

Knowledge of the physical and chemical characteristics of lignocellulosic raw materials helps in the selection of biomass for chemical processing to obtain high value-added products.

Table 2 shows the results obtained for the physical characterization of açaí seeds based on the Volatile Material Content, Ash Content and Fixed Carbon Content, after the drying process in an oven at 105 °C.

By analyzing the presented data, it is observed that the volatile matter content of the dried açaí seeds obtained in this study (81.63%) is consistent with values found in the literature, being quite close to those reported by [

27] (85.98%), [

28] (80.77%), and Seye et al. [

29] (80.35%). This similarity demonstrates that açaí seeds, regardless of origin, exhibit a composition rich in volatile compounds, a typical characteristic of lignocellulosic biomass, which favors thermochemical conversion processes such as pyrolysis and gasification. The ash content, corresponding to the inorganic fraction of the biomass, was 1.38%, a value slightly higher than that observed in [

27] (1.29%) but above the values reported by [

28] (0.69%) and Seye et al. [

29] (1.15%). Despite this variation, all values fall within a range considered low and acceptable for energy applications, since high ash contents can cause operational issues such as slagging, corrosion, and clogging in reactors and boilers. These minor differences may be attributed to cultivation conditions, environmental characteristics, fruit maturation stage, and the sample preparation method itself (drying, grinding, and sieving).

Regarding fixed carbon, a value of 17.00% was obtained, which is very close to those reported in the literature: 17.21% [

27], 18.50% [

28,

29]. Fixed carbon represents the solid fraction remaining after the release of volatiles and is directly associated with the formation of biochar in pyrolysis processes. This data reinforces that açaí seeds contain a significant amount of stable carbonaceous material, capable of producing biochar with good energetic and environmental properties, usable both as an energy source and as a soil conditioner or adsorbent material. Overall, the results obtained are well aligned with those already reported in the literature, confirming that açaí seeds are a biomass with favorable characteristics for thermochemical applications. The balance between the high volatile content and the significant percentage of fixed carbon makes this biomass particularly interesting for renewable energy generation and the production of value-added inputs.

3.3. Laboratory Scale Pyrolysis Process

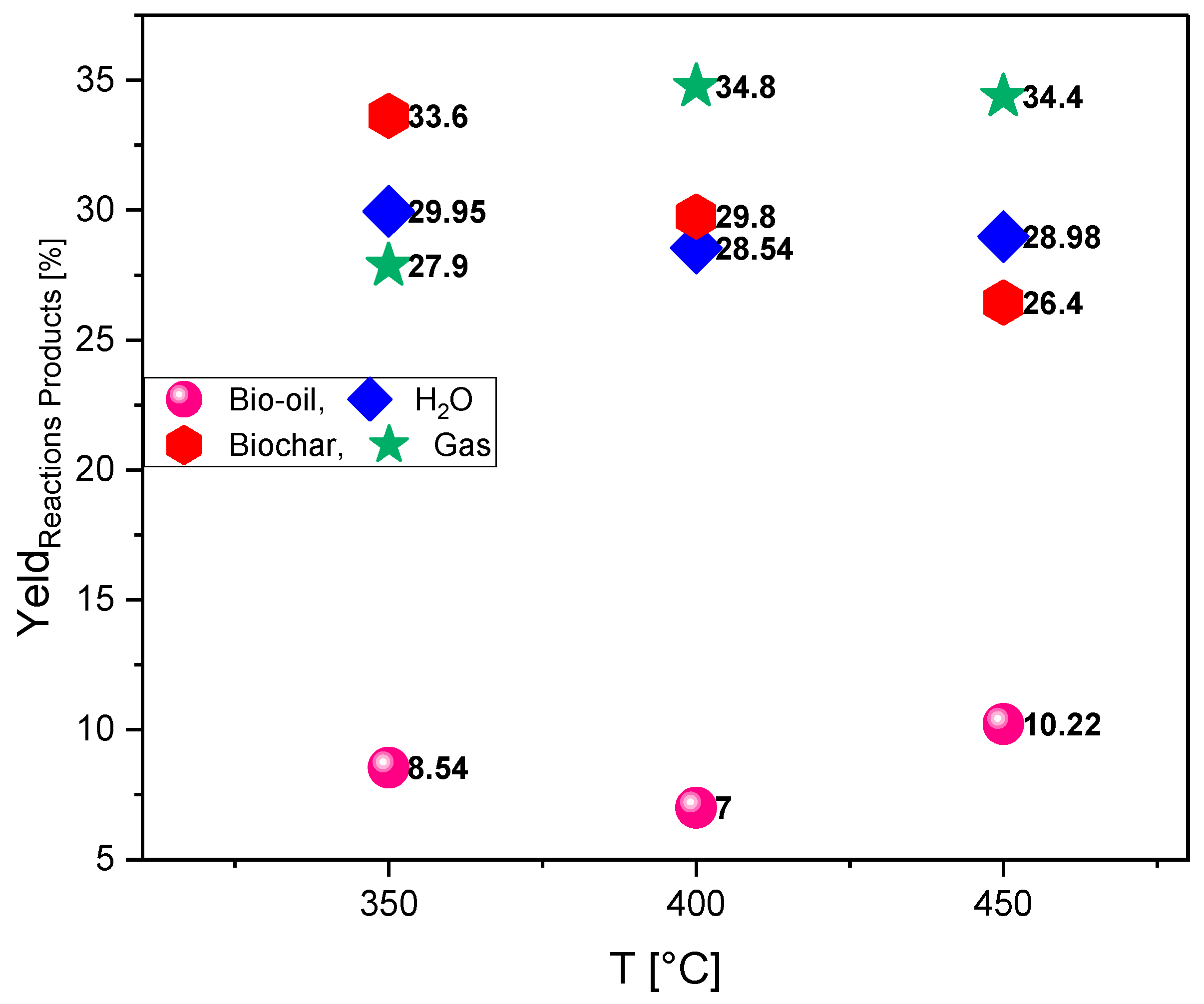

The operating conditions and steady-state mass balances of the pyrolysis of açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) seeds are presented in

Table 3, while the yields of the reaction products are illustrated in

Figure 4.

The reduced bio-oil yield at 350°C can be attributed to the impregnation with NaOH, which promotes the thermal degradation of volatile organic compounds, triggering secondary reactions that convert liquids into gases. Additionally, 350°C is a relatively low temperature to maximize bio-oil production, as the formation of this product is generally optimized between 400–600°C. The high water content may result from thermal dehydration and the reaction of NaOH with oxygenated compounds, favoring water release during pyrolysis. This factor can negatively affect the bio-oil quality, making it less energetic and more unstable due to high moisture. On the other hand, the presence of NaOH contributed to a higher biochar yield due to the chemical activation effect, promoting carbonization reactions and carbon retention in the solid phase. This result indicates that the biomass was not completely volatilized, possibly due to the moderate temperature favoring the formation of carbonaceous material rather than liquid and gaseous products. Gas formation (CO, CO₂, H₂, and CH₄) is high, aligning with NaOH’s role as a catalyst by facilitating thermal cracking and reforming of volatile compounds. This suggests that the process favored the conversion of liquid organic compounds into gases, reducing the bio-oil fraction.

Despite the temperature increase from 350°C to 400°C, the bio-oil yield decreased from 8.54% to 7.00%, which can be attributed to NaOH’s catalytic action. NaOH promotes thermal cracking of liquid compounds, converting them into light gases such as CO, CO₂, CH₄, and H₂. Additionally, higher temperatures promote repolymerization and secondary cracking, reducing the stability of condensable organic compounds. The high-water yield indicates that pyrolysis favored thermal dehydration reactions and the decomposition of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups present in the biomass. This result is consistent with the behavior of lignocellulose under catalytic pyrolysis, where oxygenated compounds are converted into CO, CO₂, and H₂O. Compared to pyrolysis at 350°C, the biochar fraction decreased from 33.63% to 29.75%, evidencing that higher temperatures promote the conversion of solid material into volatile compounds. NaOH may have also contributed to this reduction by acting as an activating agent, facilitating thermal degradation of biomass and favoring gas formation. The increased gas fraction confirms that the temperature rise and presence of NaOH accelerated biomass degradation, promoting reactions such as decarboxylation, decarbonylation, and hydrocarbon reforming. The conversion of condensable organic compounds into gases indicates greater efficiency in breaking long chains, favoring the formation of products like CO, CO₂, H₂, and CH₄, which are important for energy applications.

The higher bio-oil yield at 450°C, compared to 350°C (8.54%) and 400°C (7.00%), can be attributed to a greater conversion of biomass into condensable compounds. Higher temperatures favor the breakdown of polymeric chains of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, promoting the formation of vapors rich in phenolic compounds, acids, and hydrocarbons. This result suggests that 450°C may be an optimum point to maximize bio-oil production under NaOH impregnation. The aqueous fraction yield remained practically constant compared to previous temperatures, indicating that the presence of NaOH maintains a consistent thermal dehydration pattern of the biomass. Water may originate from lignocellulose pyrolysis or from the conversion of oxygenated compounds into H₂O, CO, and CO₂.The decrease in biochar compared to lower temperatures (33.63% at 350°C and 29.75% at 400°C) indicates that higher temperatures favor volatilization of the biomass solid components. This reinforces the role of NaOH as an activating agent, promoting thermal degradation of the carbonaceous structure and reducing the formation of solid residue. The gas fraction remained high, similar to that obtained at 400°C (34.76%), suggesting that the conversion of condensable material into gaseous products stabilized within this temperature range. NaOH likely contributed to thermal cracking and decarboxylation of oxygenated compounds, favoring the formation of CO, CO₂, CH₄, and H₂ — gases with significant energetic potential.

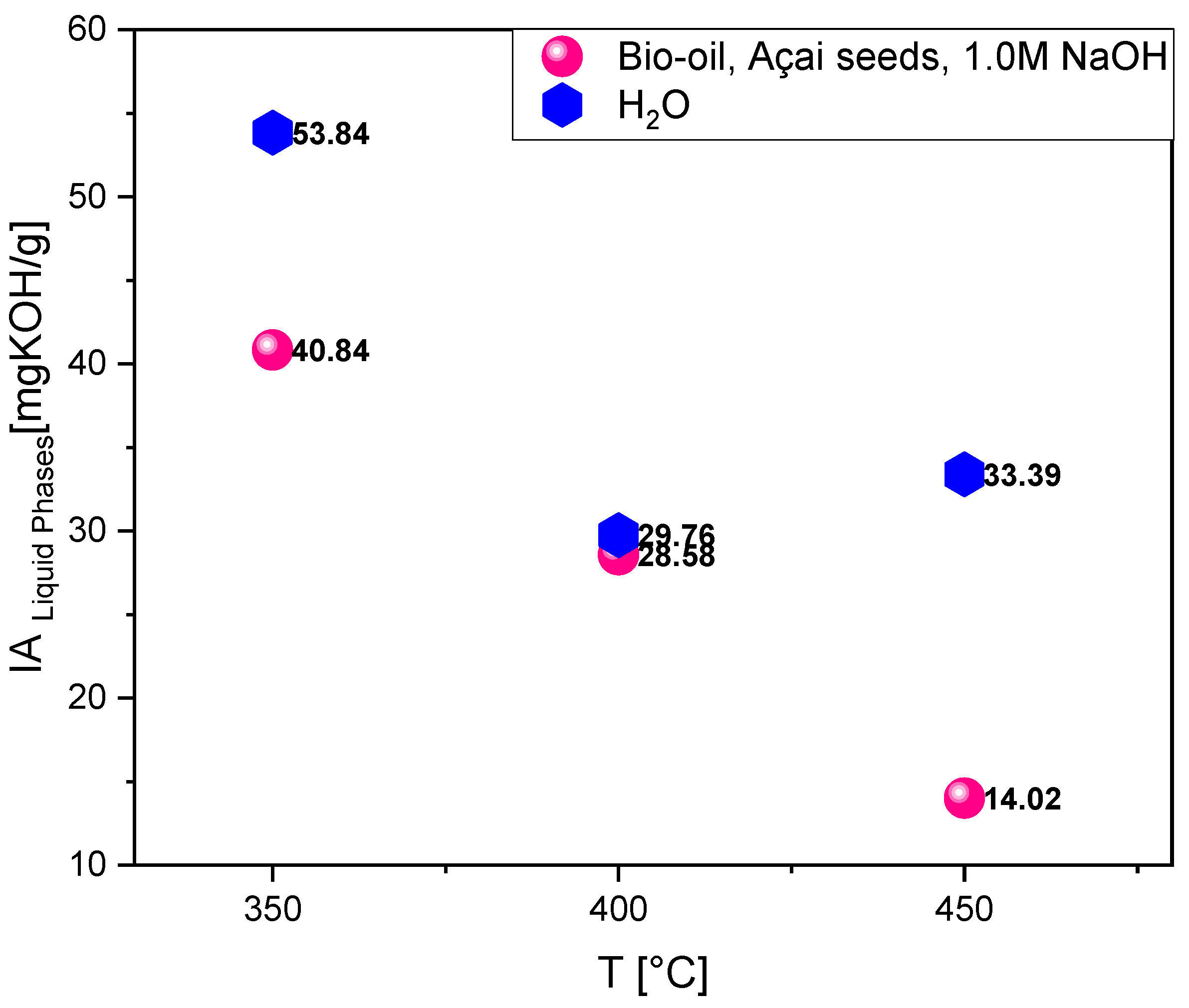

3.4. Acidity Index of Bio-Oil and Aqueous Phase

The acidity index values of the bio-oils produced by the pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH at temperatures of 350°C, 400°C, and 450°C were 40.84 mg KOH/g, 28.58 mg KOH/g, and 14.02 mg KOH/g, respectively (

Table 4), as illustrated in

Figure 5. These values indicate a decreasing trend in the acidity index with increasing pyrolysis temperature. At the lower temperature (350°C), pyrolysis is not as efficient in removing acidic oxygenated functional groups, such as carboxylic acids. This results in a bio-oil with higher acidity, reflecting an elevated content of acidic compounds. At 400°C, the thermal decomposition of biomass components is more intense, promoting the breakdown of carboxylic acids into less acidic compounds, such as ketones and phenols. This reduces the acidity index compared to the bio-oil obtained at 350°C, although it still retains a significant amount of oxygenated compounds. At the highest tested temperature (450°C), pyrolysis is sufficiently vigorous to decompose a large portion of acidic groups, further reducing the acidity index. The high temperature favors the formation of hydrocarbons and the conversion of carboxylic acids into less oxygenated compounds, resulting in a bio-oil with lower acidity.

These values demonstrate that the pyrolysis process at increasing temperatures, combined with NaOH impregnation, tends to reduce the acidity index of the bio-oil, which may be advantageous for applications where lower acidity bio-oils are desired. Additionally, this acidity reduction aligns with the progressive decrease of acidic oxygenated compounds, such as carboxylic acids, and the formation of more stable and less reactive compounds as the temperature rises. The acidity index values of the aqueous phase from açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH, obtained at pyrolysis temperatures of 350°C, 400°C, and 450°C, were 53.84 mg KOH/g, 29.76 mg KOH/g, and 33.39 mg KOH/g, respectively. The aqueous phase obtained at the lowest temperature of 350°C showed the highest acidity index. This can be explained by the lower thermal decomposition of acidic oxygenated compounds, resulting in a higher concentration of carboxylic acids and other acidic compounds in the aqueous phase.

At 400°C, pyrolysis becomes more intense, favoring partial decomposition of carboxylic acids and other oxygenated compounds, which significantly reduces the acidity index. This temperature appears to promote the conversion of acidic compounds into less acidic products, such as ketones and phenols, thereby decreasing acidity in the aqueous phase. Although 450°C is a higher temperature, the acidity index of the aqueous phase shows a slight increase compared to 400°C. This behavior may be attributed to the formation of new oxygenated compounds or the reincorporation of carboxylic acids into the aqueous phase due to secondary reactions, such as the reformulation of oxygenated structures. These results suggest that the acidity index of the aqueous phase initially decreases with increasing pyrolysis temperature but tends to stabilize or even slightly increase at higher temperatures (450°C), possibly due to secondary reactions forming additional acidic compounds. This behavior may indicate that 400°C is the most efficient temperature for reducing acidity in the aqueous phase, while at 450°C some oxygenated compounds reappear or stabilize in the aqueous phase.

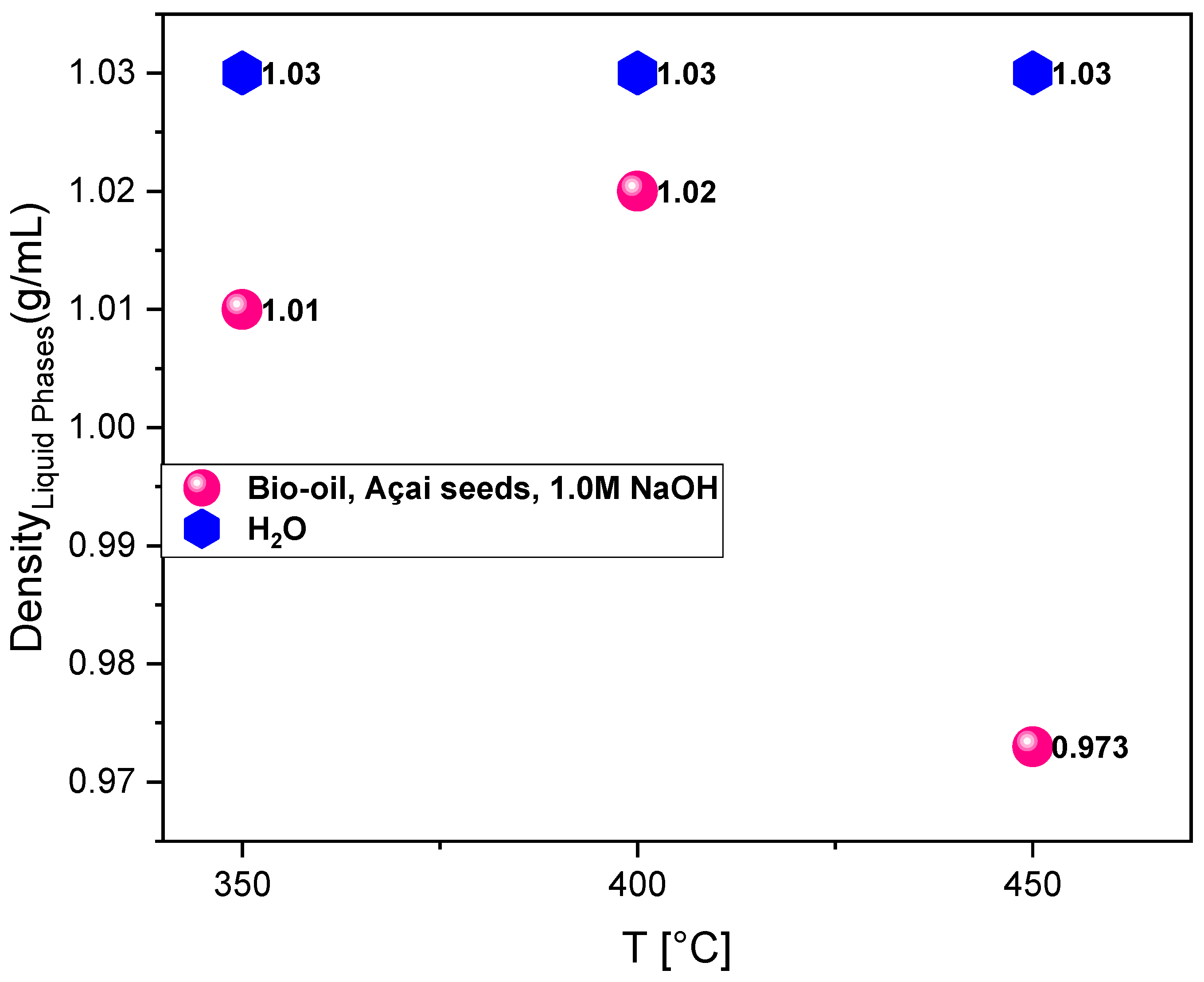

3.1. Density of Bio-Oil and Aqueous Phase

The density values of the bio-oils obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH at temperatures of 350°C, 400°C, and 450°C were 1.01 g/cm³, 1.02 g/cm³, and 0.973 g/cm³, respectively (

Table 5) and are illustrated in

Figure 6.

The density of the bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH varied as a function of temperature, directly reflecting the thermochemical transformations occurring during the process. It was observed that, in the range from 350°C to 400°C, there was a slight increase in density from 1.01 g/cm³ to 1.02 g/cm³. This behavior can be attributed to the greater formation of medium molecular weight oxygenated compounds, such as carboxylic acids, phenols, and alcohols, which have hydroxylated characteristics and high polarity. In this temperature range, degradation reactions of hemicellulose and the initial decomposition of cellulose predominate, resulting in liquid products with higher functional group content, which directly influences the increase in density. When the temperature was raised to 450°C, a reduction in bio-oil density to 0.973 g/cm³ was observed. This result is directly related to the increased thermal severity, which favors cracking, decarboxylation, and decarbonylation reactions responsible for breaking down macromolecules into lighter and less oxygenated hydrocarbons. This phenomenon results in bio-oils with lower density, higher content of nonpolar compounds, and consequently, a better energy profile, since the reduction in oxygen content contributes to increased heating value. Studies by [

31,

32] corroborate these findings, demonstrating that increasing the temperature during biomass pyrolysis promotes the production of bio-oils with physicochemical characteristics more compatible with fossil fuels.

Regarding the aqueous phase, the density remained constant at 1.03 g/cm³ across the three evaluated temperatures. This behavior suggests that, although the volume produced may vary as a function of temperature, the relative composition of the aqueous phase remained practically unchanged. This indicates that the generation of water-soluble compounds, such as low molecular weight organic acids (acetic, formic, and lactic acids), as well as light alcohols and aldehydes, occurs proportionally under the three thermal conditions studied. The stability in density is associated with the predominance of water combined with these soluble organic compounds, whose content does not show significant variations within the applied temperature range. Additionally, the presence of the alkaline agent NaOH during pyrolysis plays a relevant role in influencing the properties of the liquid products. The alkalinity promotes the cleavage of ester and ether bonds present in lignin and hemicellulose, facilitating the conversion of these macromolecules into phenolic compounds and carboxylic acids. Furthermore, it contributes to reducing the formation of coke and undesirable compounds, shifting the process equilibrium towards higher liquid production. This effect may also explain the production of bio-oils with slightly lower density compared to the average reported for conventional bio-oils derived from biomass pyrolysis, whose density typically ranges between 1.1 and 1.2 g/cm³.

3.2. Kinematic Viscosity of Bio-Oil and Aqueous Phase

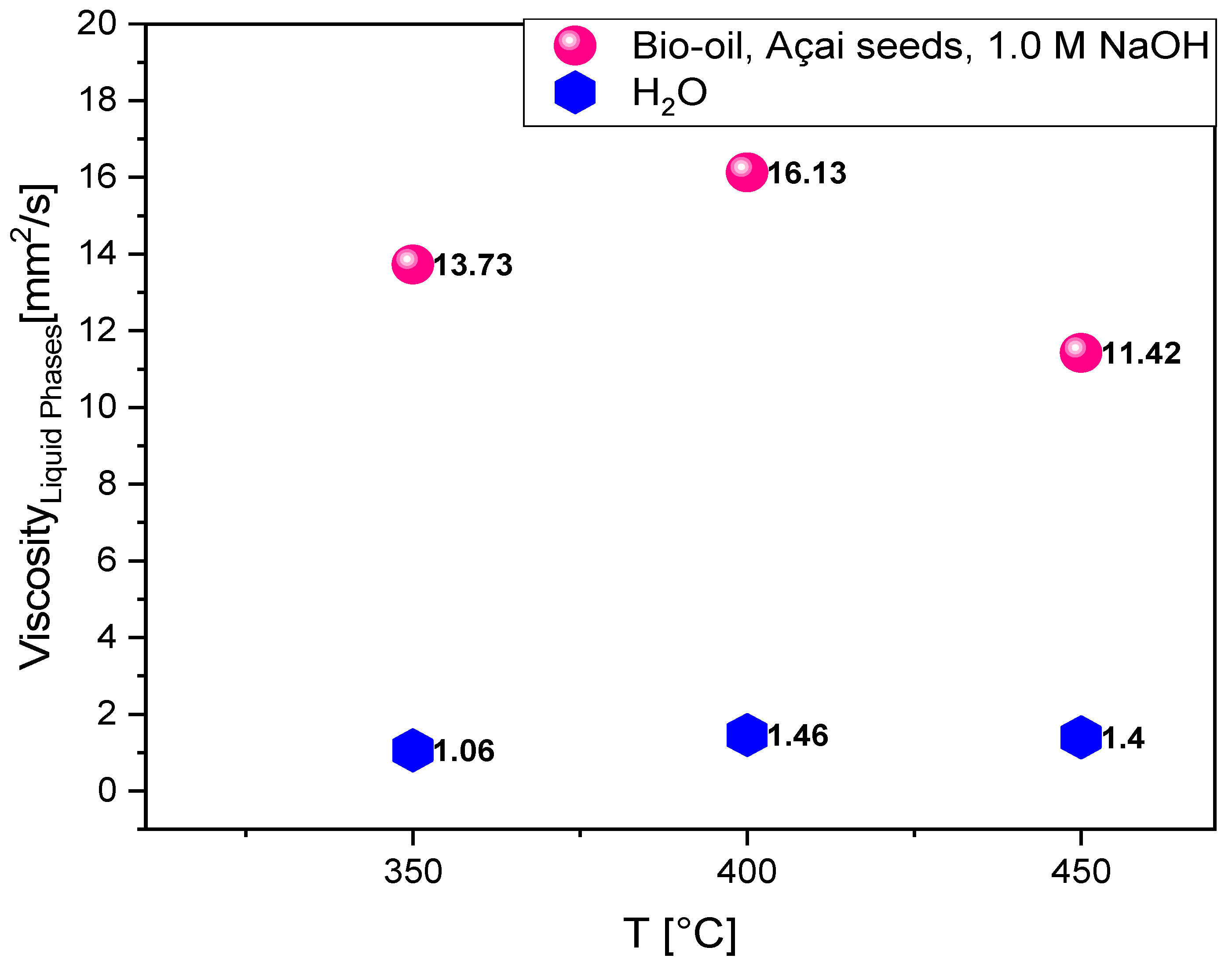

The highest viscosity value for the bio-oils (

Table 6), as illustrated in

Figure 7, was observed at 400°C (16.13 mm²/s), which may indicate a greater formation of oxygenated compounds with more complex molecular structures, such as carboxylic acids or phenols, that tend to increase viscosity. The decrease in viscosity at 450°C (11.42 mm²/s) suggests that the higher temperature favors the thermal cracking of long chains or high molecular weight compounds into lighter and less viscous components. Thus, the higher temperature is likely to promote greater conversion into hydrocarbons or lighter oxygenates, which contributes to the reduction in viscosity.

The NaOH impregnation may facilitate decarboxylation or deoxygenation reactions, which reduce the presence of high molecular weight oxygenated compounds at higher temperatures, thereby helping to decrease the bio-oil viscosity. These results suggest that the viscosity of the bio-oils varies with the pyrolysis temperature due to the formation and decomposition of specific compounds. Pyrolysis at 400°C produces bio-oils with higher viscosity, possibly due to increased formation of complex oxygenates, whereas pyrolysis at 450°C favors the breakdown of these compounds, resulting in lower-viscosity bio-oils that are richer in light hydrocarbons. NaOH impregnation appears to facilitate these transformations, especially at higher temperatures.

The increase in the viscosity of the aqueous phase to 1.46 mm²/s at 400°C suggests that, at this temperature, there is a more significant formation of polar oxygenated compounds or larger molecular chains in the aqueous phase. The NaOH impregnation may have favored the formation of acidic or phenolic species, which contribute to a higher-viscosity liquid. The slight decrease to 1.40 mm²/s at 450°C may indicate that, at higher temperatures, some of these more complex structures undergo thermal cracking, producing smaller and less viscous compounds. However, this variation is less pronounced than that observed in the bio-oil, as the aqueous phase still retains a significant content of oxygenated compounds that are less sensitive to temperature increases compared to those in the bio-oil. The NaOH impregnation influences the presence of polar compounds in the aqueous phase, which can increase viscosity at intermediate temperatures. Additionally, the alkalinity of NaOH may favor saponification reactions or partial hydrolysis of certain components, affecting the viscosity properties. The viscosity values of the aqueous phase increase from 350°C to 400°C and slightly decrease at 450°C, possibly due to the formation and partial decomposition of oxygenated compounds. NaOH impregnation promotes the formation of polar compounds that contribute to higher viscosity, especially at moderate temperatures like 400°C.

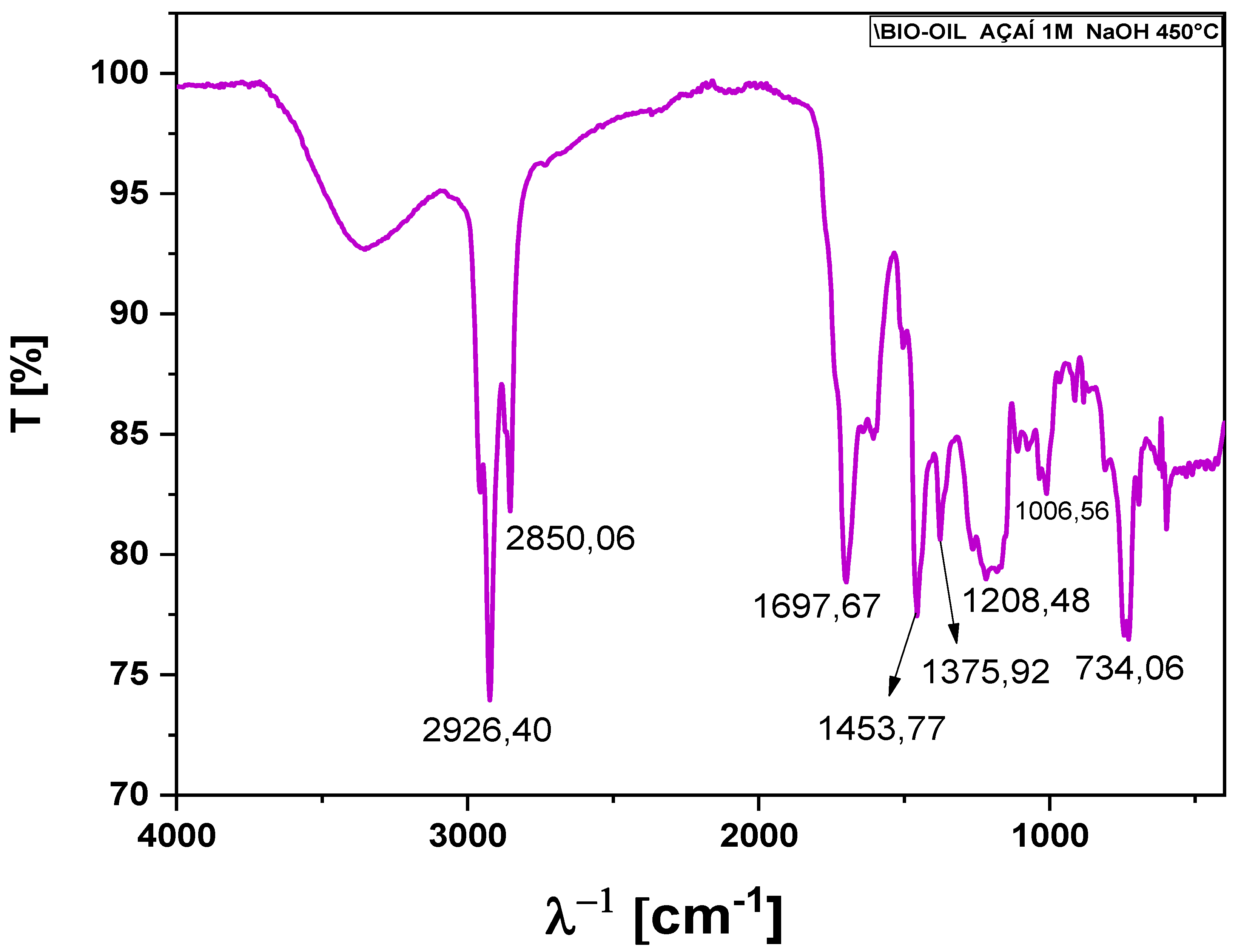

3.3. FT-IR of Bio-Oil

Given that the infrared spectra results of the bio-oils obtained from açaí seeds were similar, it was decided to present only a representative spectrum of the bio-oil produced by thermal pyrolysis at 450°C, using açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH (

Figure 8). The bands in the range of 2926.40 to 2850.06 cm⁻¹ in the FTIR spectrum generally correspond to the stretching vibrations of C-H bonds in methyl (CH₃) and methylene (-CH₂-) groups present in aliphatic hydrocarbons.

The FTIR band at 1697.67 cm⁻¹, observed in the spectrum of the bio-oil from NaOH-impregnated açaí seeds, indicates C=O stretching vibrations, characteristic of carbonyl compounds such as ketones, aldehydes, or carboxylic acids. This absorption suggests the presence of these functional groups in the bio-oil, reflecting the pyrolysis reactions and the chemical modifications promoted by NaOH impregnation. The band at 1453.77 cm⁻¹ is attributed to C-H bending vibrations in methyl (-CH₃) and methylene (-CH₂-) groups, suggesting the presence of aliphatic structures, such as alkanes, which are typical in biomass pyrolysis products. The NaOH impregnation may have altered the composition and intensity of these bands, highlighting changes in the molecular structure of the bio-oil. The band at 1375.92 cm⁻¹, associated with symmetric C-H bending in methyl (-CH₃) groups, indicates the presence of hydrocarbon chains, commonly found in pyrolysis products like the bio-oil from açaí seeds. These aliphatic structures may have been preserved or formed during the NaOH impregnation process at 1M concentration. The band at 1208.48 cm⁻¹ is related to C-O stretching in esters, ethers, or phenols, indicating the presence of oxygenated compounds formed or retained during pyrolysis. NaOH impregnation at 1M may have favored the formation of these oxygenated groups, reflecting chemical alterations in the original material.

The band at 1006.56 cm⁻¹, associated with C-O stretching in primary and secondary alcohols and some ether structures, indicates the presence of oxygenated compounds such as alcohols or ethers, which may have emerged during thermal decomposition. The NaOH impregnation may have stabilized or contributed to the formation of these groups in the final bio-oil. Finally, the band at 734.06 cm⁻¹, attributed to out-of-plane C-H bending vibrations in aromatic hydrocarbons, such as substituted benzene rings, indicates the presence of aromatic structures in the bio-oil. The 1M NaOH impregnation may have influenced the retention or formation of these aromatic compounds, which are typical products from the decomposition of lignocellulosic structures in biomass during pyrolysis.

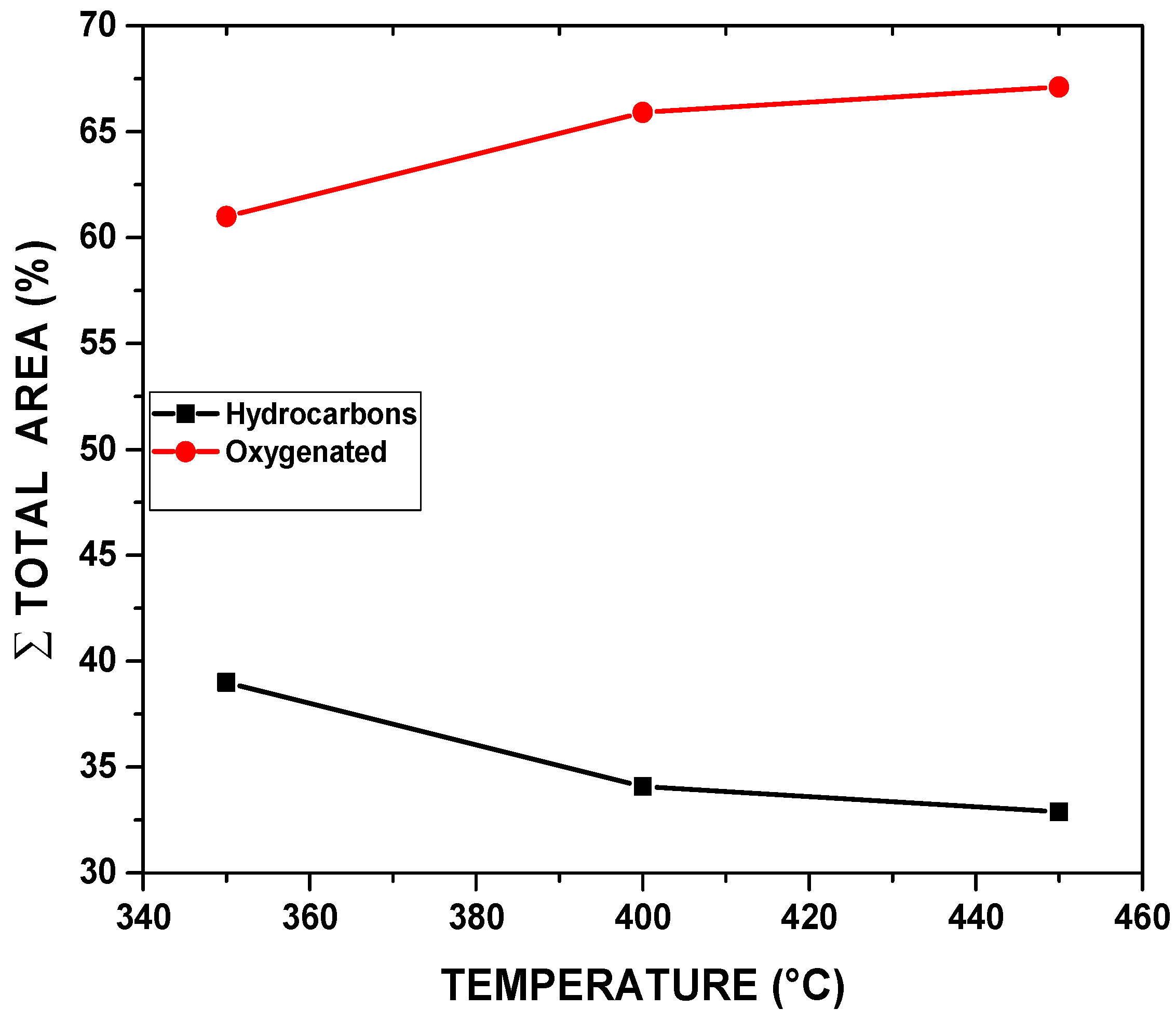

3.4. Cromatografia Gasosa Acoplada ao Espectro de Massa (GC/MS)

Table 7 and

Figure 9 illustrate the effect of temperature on the chemical composition, expressed in hydrocarbons and oxygenates, of the bio-oils obtained by thermal pyrolysis of açaí pits impregnated with 1M NaOH at 350°C, 400°C, and 450°C, under an inert atmosphere, on a laboratory scale. The chemical functions (alcohols, carboxylic acids, and other oxygenated compounds), sum of the peak areas, CAS numbers, and retention times of all the molecules identified in the bio-oils by GC-MS are presented in Supplementary

Tables S1–S3.

The bio-oil produced at 350°C contains 39% hydrocarbons and 61% oxygenated compounds. The relative area of hydrocarbons compared to oxygenates is higher at this temperature than at higher temperatures. At 400°C, the bio-oil presented 34.09% hydrocarbons and 65.91% oxygenates, reflecting an increase in the formation of oxygenated compounds compared to 350°C. This suggests greater decomposition and modification of the biomass, with the breakdown of more complex structures favoring the formation of oxygen-containing groups. At 450°C, the hydrocarbon concentration is the lowest (32.89%), while the oxygenated compound concentration is the highest (67.11%). Pyrolysis at 450°C results in more intense thermal degradation, promoting the formation of oxygenated compounds such as phenols, carboxylic acids, and ketones, while hydrocarbon formation is less favored.

In terms of area, the difference between the hydrocarbon and oxygenate areas is greater at 350°C since this temperature tends to favor the formation of simpler, less oxygenated hydrocarbons. As the temperature increases, especially at 450°C, hydrocarbons are further broken down into more oxygenated products, which is reflected in the larger area occupied by oxygenated compounds

At 350°C, although there is a higher relative yield of hydrocarbons, the total amount of bio-oil produced is likely to be lower in terms of mass or volume since the pyrolysis process is not as intense as at higher temperatures. The higher hydrocarbon content may be advantageous for applications such as liquid fuels or biofuels, but the formation of oxygenated compounds is more limited. In contrast, at 450°C, the higher yield of oxygenated compounds reflects greater thermal decomposition and molecular breakdown of the biomass. This can be advantageous for applications that require high-oxygen-content products, such as chemical feedstocks or bio-oils used in the production of second-generation biofuels.

The influence of NaOH on the impregnation process of açaí pits for bio-oil production at 350°C shows that at lower temperatures, pyrolysis tends to produce low molecular weight oxygenates such as carboxylic acids and aldehydes. NaOH impregnation favors the retention of oxygen in the compounds, partially inhibiting the formation of pure hydrocarbons and increasing the content of oxygenated compounds, resulting in bio-oils with high acidity and polarity. At 350°C, the energy supplied is limited for complete decomposition, leading to a bio-oil yield with fewer hydrocarbons and more oxygenated compounds, such as phenols and alcohols.

At 400°C, the breakdown of lignocellulosic structures is more pronounced. The presence of NaOH facilitated lignin decomposition and favored the formation of phenolic compounds and ketones. NaOH impregnation promoted reactions that led to the formation of oxygenated compounds such as acids, phenols, and esters. These compounds result from the partial decomposition of complex biomass polymers, catalyzed by NaOH. Compared to bio-oils without impregnation, as reported in [

5,

12,

21] the presence of the base (NaOH) inhibits the formation of pure aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, maintaining a more oxidized profile in the bio-oil.

At 450°C, thermal decomposition is more intense, and NaOH impregnation continues to favor the formation of oxygenated compounds, reaching a significant proportion (67.11% oxygenates). Compounds such as carboxylic acids, phenols, ketones, and esters are predominant. While higher temperatures generally favor hydrocarbon formation, the presence of 1M NaOH tends to inhibit this conversion by stabilizing oxygen-containing groups and catalyzing partial oxidation reactions. The alkaline medium helps stabilize oxygenated functional groups, such as phenols and ketones, which remain in the bio-oil even at higher temperatures. This effect is especially relevant for applications that require oxygen-rich bio-oils. It can be concluded that impregnation with 1M NaOH influences the pyrolysis of açaí pits by promoting a bio-oil with a high content of oxygenated compounds and reduced hydrocarbon formation. This trend increases with temperature due to the ability of NaOH to catalyze partial oxidation reactions, stabilize oxygenated groups, and decompose lignin and cellulose, resulting in a greater variety of oxygenated compounds in the final bio-oil, especially at higher temperatures.

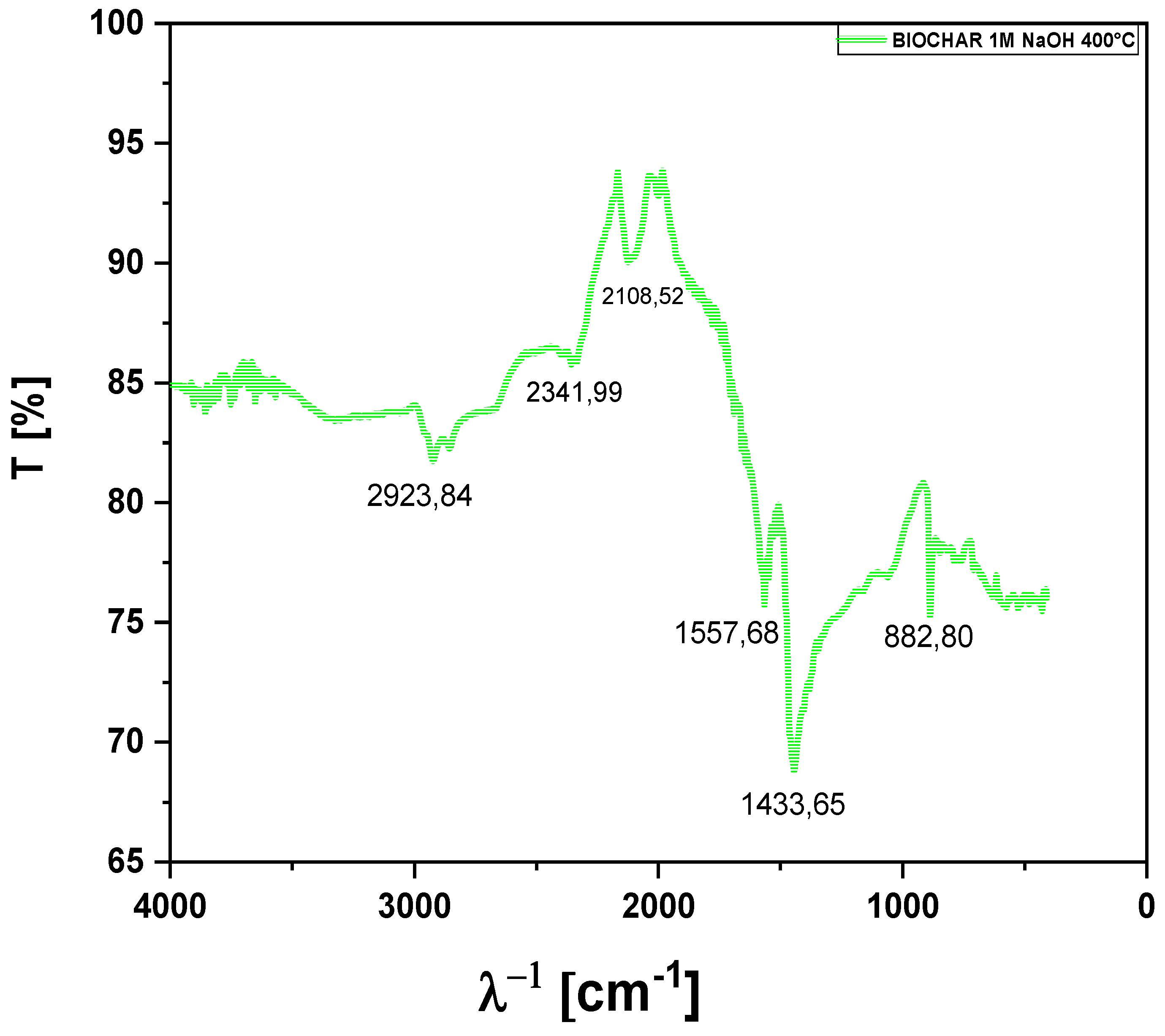

3.5. FT-IR of Biochar

Given that the infrared spectra of the biochars obtained from açaí pits showed similar results, it was decided to present only a representative spectrum of the biochar produced by thermal pyrolysis at 400°C, using açaí pits impregnated with 1M NaOH (

Figure 10). The FTIR band at 2923.84 cm⁻¹, observed in the biochar spectrum, is associated with asymmetric C-H stretching of methyl (-CH₃) and methylene (-CH₂-) groups. This absorption is characteristic of aliphatic chains, suggesting the presence of hydrocarbons in the biochar. The impregnation with NaOH may modify the structure of these aliphatic compounds, altering the intensity or profile of the bands, which reflects structural changes caused by pyrolysis and the impregnation process.The FTIR band at 2341.99 cm⁻¹ is commonly attributed to C≡O stretching, characteristic of carbon dioxide (CO₂) or compounds with C≡N bonds (nitriles). In biochars resulting from biomass pyrolysis, such as the biochar from açaí pits impregnated with 1M NaOH, this band may indicate the presence of small amounts of adsorbed CO₂ or CO₂ released during pyrolysis, or it may result from the interaction with NaOH. It may also reflect residual oxygenated functional groups that remained in the biochar after thermal decomposition.

The FTIR band at 2108.52 cm⁻¹ is associated with C≡C or C≡N bond stretching, suggesting the presence of unsaturated compounds, such as alkynes or nitriles. In the case of biochar from açaí pits impregnated with 1M NaOH, this band indicates the formation of unsaturated compounds during the thermal pyrolysis of biomass, with NaOH impregnation possibly influencing the formation or stability of these functional groups in the biochar. The FTIR band at 1557.68 cm⁻¹ is attributed to stretching or deformation vibrations of C=C bonds in aromatic rings or unsaturated compounds. This absorption suggests the presence of aromatic structures or compounds with conjugated double bonds, such as benzenes, which can be formed during the pyrolysis of biomass. Impregnation with 1M NaOH may have favored the formation or stabilization of these aromatic compounds in the biochar, a common characteristic in products derived from the thermal decomposition of lignocellulosic biomass. The FTIR band at 1433.65 cm⁻¹ is associated with C-H bending of methyl (-CH₃) or methylene (-CH₂-) groups in aliphatic compounds. This peak indicates the presence of aliphatic structures or hydrocarbons in the material, such as alkanes or other components derived from biomass pyrolysis. In the biochar from açaí pits impregnated with 1M NaOH, this band suggests that the pyrolysis process resulted in products with aliphatic chains, and the NaOH impregnation may have influenced the intensity or distribution of these bands, modifying the biochar composition.

The FTIR band at 882.80 cm⁻¹ is related to out-of-plane bending vibrations of C-H bonds in aromatic compounds, especially in substituted aromatic rings. This absorption suggests the presence of aromatic compounds formed during the pyrolysis of biomass. In the biochar from açaí pits impregnated with 1M NaOH, this band may indicate the formation or retention of aromatic compounds, typical of the products of thermal decomposition, particularly if the original biomass contains lignin or other components that favor the formation of these aromatic structures. The impregnation with NaOH may have influenced the stability or quantity of these compounds in the final biochar.

3.10. Antioxidant Activity of Bio-Oils Obtained from Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1M NaOH

3.10.1. Sequestration of the ABTS•+ Radical by Bio-Oil Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1M NaOH at 350°C

The bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds activated with 1M NaOH solution at 350 °C exhibited the highest antioxidant activity among the three temperatures evaluated in the ABTS•+ radical scavenging assay, as shown in

Figure 11. At higher concentrations (2 and 1 mg/mL), the antioxidant activity was comparable to that of ascorbic acid (positive control), with no statistically significant difference in certain ranges, demonstrating its effectiveness in neutralizing free radicals. This superior performance can be attributed to the temperature of 350 °C, considered optimal for the preservation and release of phenolic compounds, organic acids, and bioactive oxygenated structures.

Moderate pyrolysis allows controlled degradation of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, releasing low molecular weight molecules with functional groups such as –OH, –COOH, and conjugated carbonyls, which are responsible for reducing mechanisms against the ABTS•+ cation [18;22]. Furthermore, alkaline activation with 1M NaOH prior to pyrolysis significantly contributes to the increase in antioxidant activity by promoting the cleavage of ester bonds and depolymerization of lignocellulosic chains. This process enhances the formation of phenols and carboxylic acids during heating, which are known for their ability to donate electrons or hydrogen atoms and stabilize the ABTS•+ radical through resonance. Recent literature supports these findings. Valois et al. [

9], while investigating the effect of chemical activation and pyrolysis temperature of açaí pits, observed an increase of up to 35% in the antioxidant activity of bio-oils treated with NaOH compared to non-activated ones, especially under thermal conditions similar to those of this study [

9].

Additionally, a dose-dependent behavior was observed in the bio-oil produced at 350 °C: as the sample concentration decreased (from 2 to 0.06 mg/mL), the antioxidant activity progressively declined, a typical pattern of natural antioxidant systems. At lower concentrations (≤ 0.25 mg/mL), the difference compared to the control was statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating that the efficacy of the bio-oil depends on the amount of active compounds available in the solution. Finally, it is noteworthy that the bio-oil produced at 350 °C has a balanced chemical composition, with an ideal proportion of volatile and oxygenated compounds, which not only favors antioxidant activity but also improves the solubility of these compounds in the aqueous medium used in the ABTS•+ assay. This chemical balance tends to be lost at higher temperatures, where bioactive compounds are thermally degraded and replaced by stable but less reactive aromatic structures [9;20].

3.10.2. Sequestration of the ABTS•+ Radical by Bio-Oil Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1M NaOH at 400°C

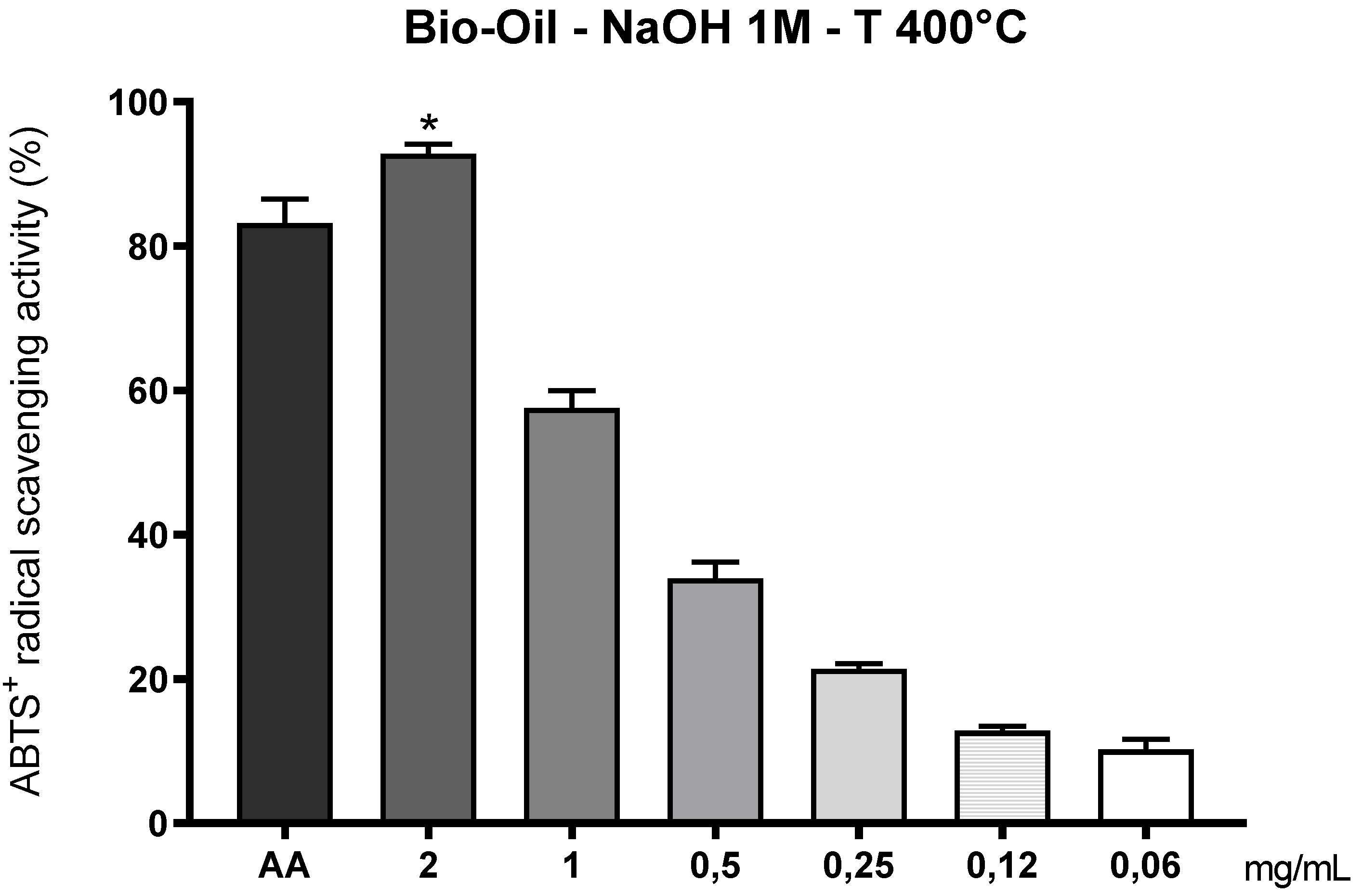

The bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds activated with 1M NaOH at 400 °C, shown in

Figure 12, exhibited measurable antioxidant capacity in the ABTS•+ radical scavenging assay, although lower than that observed for the bio-oil produced at 350 °C. This difference was particularly significant at lower concentrations (≤ 0.25 mg/mL), where the antioxidant activity was considerably reduced compared to the control (ascorbic acid, 2 mg/mL), with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05).

This result suggests that increasing the pyrolysis temperature to 400 °C negatively affected the preservation of thermally sensitive antioxidant compounds, such as short-chain phenols, oxygenated fatty acids, and flavonoids. Exposure of the biomass to higher temperatures promotes greater thermal degradation and partial carbonization of the organic matter, favoring the formation of condensed aromatic structures, which exhibit lower reactivity toward the ABTS•+ radical [

20]. Oribe et al. [

30] reported similar behavior when using lignocellulosic residues to produce bio-oil at 400 °C. The authors observed that under this condition, phenolic fractions are converted into less polar condensed aromatic compounds, which impairs their antioxidant performance in aqueous systems—such as the ABTS•+ assay [

30].

Despite these limitations, the sample pyrolyzed at 400 °C maintained relevant antioxidant activity at higher concentrations (2 and 1 mg/mL), indicating the residual presence of thermo-stable antioxidant compounds, such as alkylated phenols and aromatic acids, which exhibit greater resistance to thermal degradation. The prior alkaline activation with 1M NaOH may have contributed to this stability by promoting lignin depolymerization and the release of functionalized aromatic fragments, even at higher temperatures [

9,

19].

The progressive reduction in antioxidant activity with decreasing sample concentration reinforces the dose-dependent profile characteristic of bio-extracts and plant-based bio-oils. This trend becomes more pronounced in bio-oils obtained at temperatures above 400 °C, in which the density of reducing groups significantly decreases.

Another critical factor is related to the polarity of the compounds formed. At 400 °C, there is an increase in the generation of aromatic and long-chain aliphatic hydrocarbons, which are less polar compounds and exhibit low affinity with the ABTS•+ cation—soluble in aqueous medium. This mismatch between the biochemical matrix polarity and the target radical may compromise the neutralization efficiency [

23,

26], explaining the lower effectiveness observed.

3.10.3. Sequestration of the ABTS•+ Radical by Bio-Oil Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1M NaOH at 450°C

The bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí pits activated with 1M NaOH at 450 °C, shown in

Figure 13, exhibited the lowest antioxidant activity among the three temperatures evaluated in the ABTS•+ radical scavenging assay. A significant reduction in scavenging capacity was observed at nearly all tested concentrations, being statistically lower than the control (ascorbic acid, 2 mg/mL), even at the highest concentrations. This inferior performance is directly related to the elevated pyrolysis temperature, which promotes intensified carbonization of the lignocellulosic biomass, favoring the formation of gaseous and solid fractions at the expense of net yield (bio-oil).

In this thermal range, lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose undergo intense degradation, resulting in the formation of highly aromatic, poorly oxygenated, and nonpolar compounds, such as condensed aromatic hydrocarbons and stable polycyclic structures. These compounds possess a low density of antioxidant functional groups, such as phenolic hydroxyls (–OH) and carboxylic groups (–COOH), which are essential for free radical neutralization [

18,

22].

Even with prior alkaline activation using 1M NaOH—which favors the release of phenolic compounds at moderate temperatures—the high temperature of 450 °C compromises the stability of these functional groups, leading to their thermal decomposition or transformation into less reactive structures. This drastically reduces the bio-oil’s capacity to interact with the ABTS•+ cation, as evidenced by the low average scavenging values observed in spectrophotometric analyses [

9,

19].

These findings are consistent with results reported by Scarpa et al. (2024), who demonstrated that temperatures above 400 °C favor the production of poorly reactive nonpolar fractions. According to the authors, the dominance of hydrocarbons and the loss of oxygenated groups significantly reduce the bio-oil’s antioxidant response. García-Peñas et al. (2024) reinforce this observation by showing that bio-oils with a high proportion of long-chain aliphatic compounds lose up to 40% of antioxidant activity in aqueous systems, such as the ABTS•+ assay, due to the low solubility and reactivity of these compounds [

23].

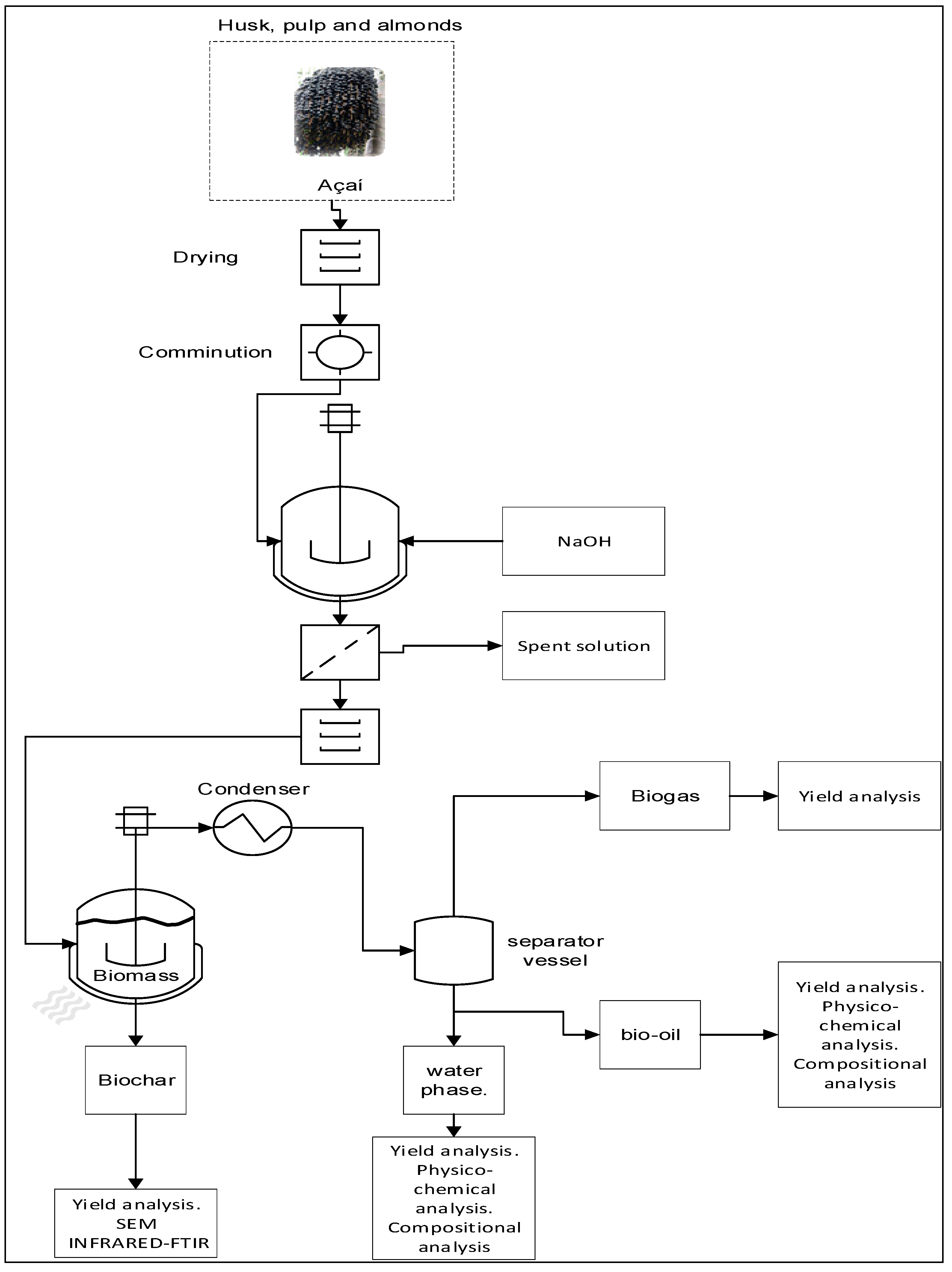

Furthermore, antioxidant activity at lower concentrations (≤ 0.5 mg/mL) was practically null or statistically lower than the control (p < 0.05), reinforcing the dose-dependent profile of bio-oils. However, even the highest tested concentrations were insufficient to reverse the trend of low efficacy, suggesting that the alteration in the chemical nature of the compounds generated at 450 °C decisively impacts antioxidant functionality. Therefore, not only the quantity of active compounds is affected at high temperatures, but also the quality and polarity of these compounds, factors crucial for antioxidant performance in hydrophilic systems such as the ABTS•+ radical. The flowchart presented in

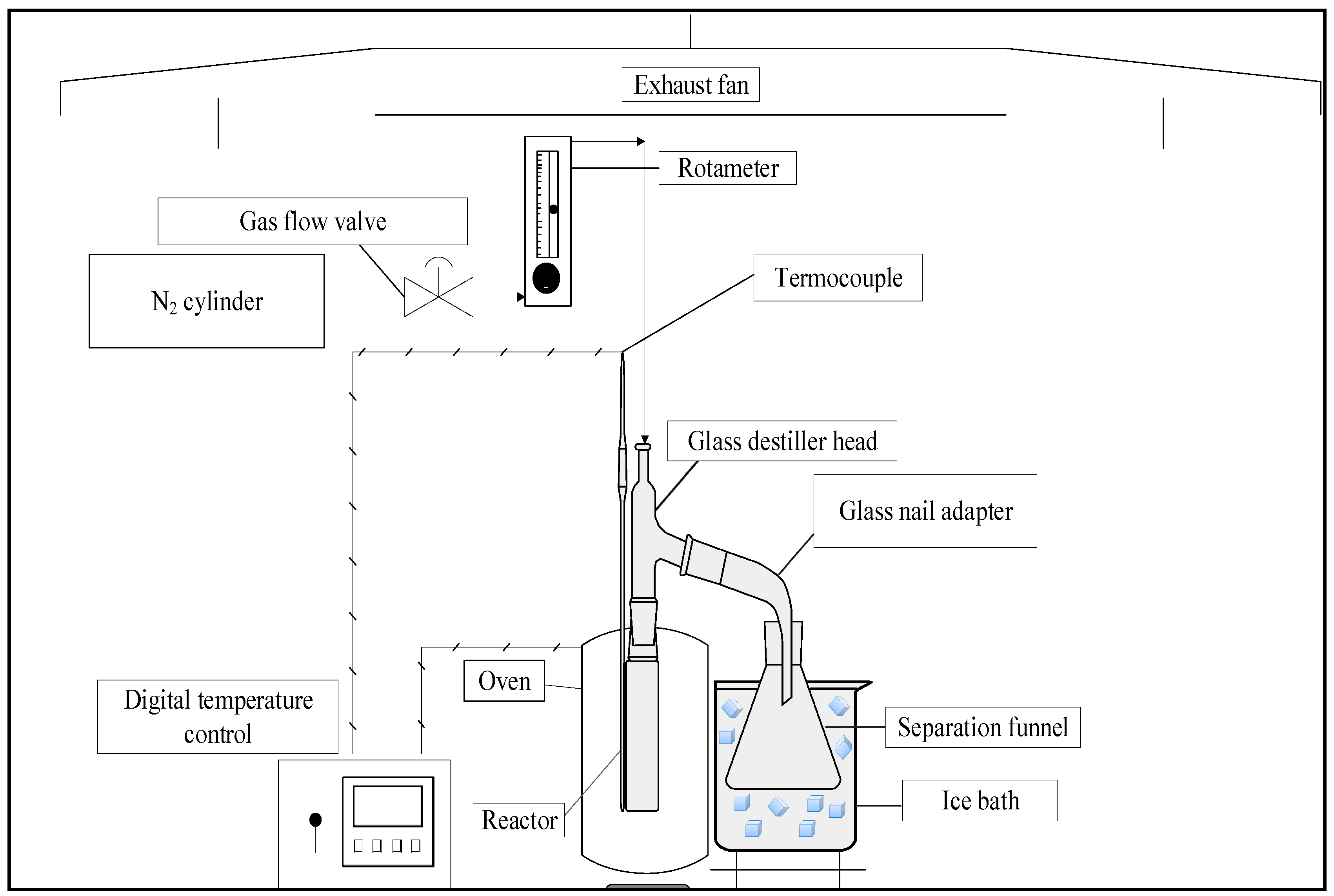

Figure 1 illustrates all the steps performed for the production and characterization of bio-oil and biochar by pyrolysis from açaí seeds. The process was conducted at 350, 400 and 450°C, under a pressure of 1.0 atm, using chemical activation with a 1.0 M NaOH solution, in a laboratory-scale fixed bed reactor. The seeds were collected from establishments that sell açaí pulp in the Guamá neighborhood of Belém-PA.

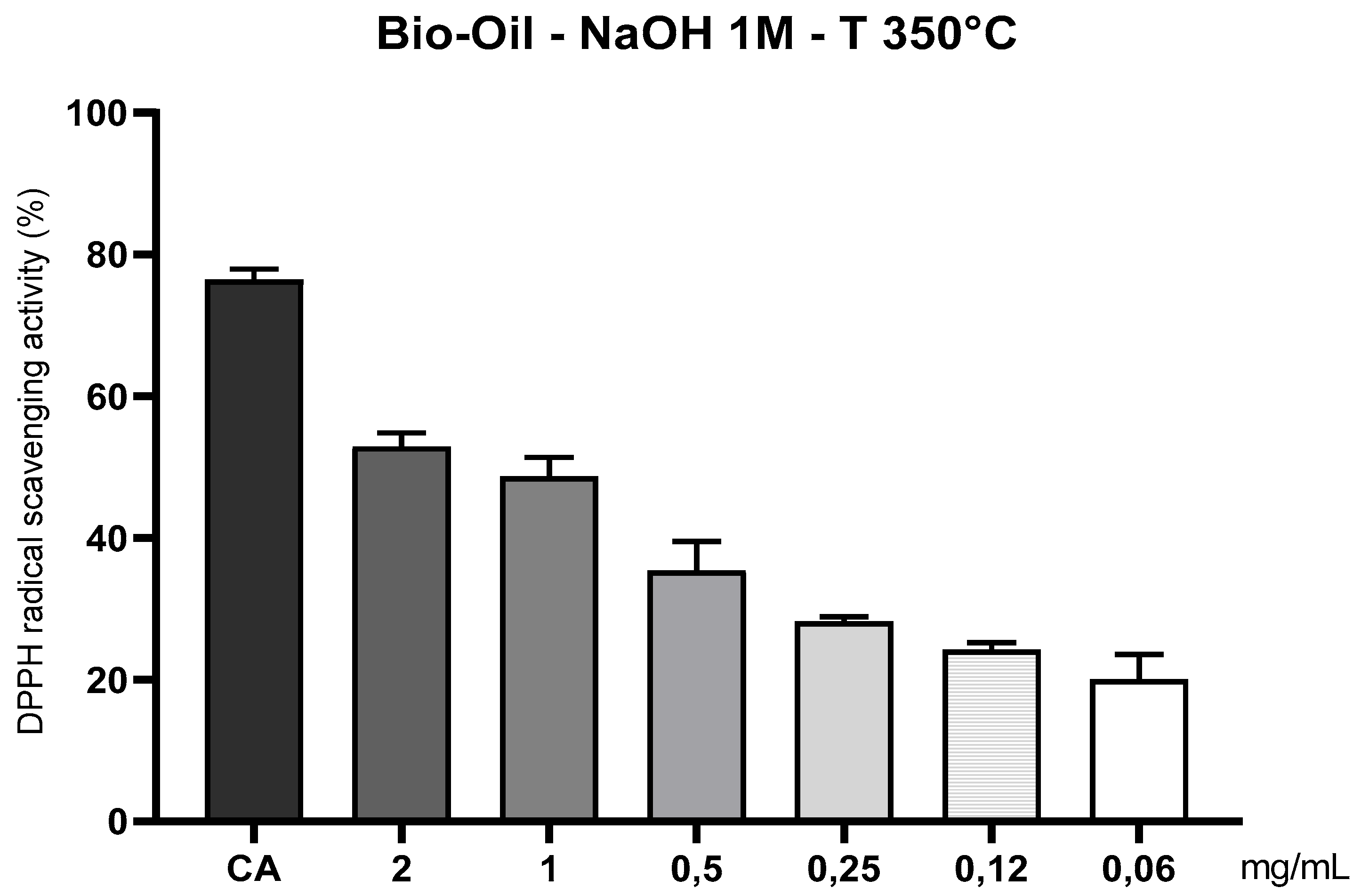

3.10.4. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Capacity of the Organic fraction of Bio-Oil, Obtained by Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1.0 M NaOH at 350°C, Using the DPPH• Radical Method (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl)

The analysis of the antioxidant activity of the organic fraction of bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí pits activated with 1M NaOH at 350 °C, using the DPPH• radical scavenging method, revealed positive results consistent with those observed in the ABTS•+ assay. In particular, at higher concentrations (2 and 1 mg/mL), the bio-oil demonstrated significant capacity to neutralize the DPPH• radical, although lower than the control used (caffeic acid – 200 µg/mL), a potent and pure antioxidant standard. The DPPH• radical (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) is widely employed to evaluate the antioxidant capacity of substances in ethanolic media, being sensitive to the presence of compounds capable of donating electrons or hydrogen atoms. The performance observed in this study indicates that the bio-oil contains phenolic compounds and oxygenated carboxylic acids, which act as reducing agents against the free radical, promoting its stabilization and discoloration [

18].

Figure 14.

Antioxidant capacity of açaí seed bio-oil (1M NaOH) by the DPPH• method at 350°C. Legend*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (350°C), through the DPPH• sequestration method. Control: caffeic acid (CA) 200 µg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL.

Figure 14.

Antioxidant capacity of açaí seed bio-oil (1M NaOH) by the DPPH• method at 350°C. Legend*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (350°C), through the DPPH• sequestration method. Control: caffeic acid (CA) 200 µg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL.

Pyrolysis at 350 °C, combined with alkaline activation with 1M NaOH, provided a favorable thermochemical environment for the release and preservation of volatile phenolic compounds, as well as promoting the formation of functional groups such as –OH and –COOH. The alkaline impregnation breaks structural bonds in lignin and hemicellulose, facilitating the release of molecules with antioxidant potential [

19]. According to Shi et al. (2025), fractions rich in oxygenated compounds, obtained by selective extraction of bio-oils, exhibited IC₅₀ values up to 20% lower compared to untreated fractions, highlighting the importance of alkaline activation in the final antioxidant efficiency [

25]. The bio-oil activity was clearly concentration-dependent, progressively decreasing with dose reduction (from 2 to 0.06 mg/mL), which is characteristic of plant extracts and complex biomass fractions. At concentrations ≤ 0.25 mg/mL, the antioxidant efficacy was statistically lower than the control (p < 0.05), reflecting the limitation of action at low doses, possibly due to the reduced availability of active reducing groups.

viability as an alternative source of natural antioxidants, especially if subjected to purification or selective concentration processes. Although caffeic acid demonstrated higher scavenging capacity—being a pure compound, the bio-oil, despite being a complex and multifunctional matrix, was able to express relevant antioxidant activity, evidencing its potential for applications in cosmetic or food formulations or as an antioxidant additive for renewable fuels [

9,

25].

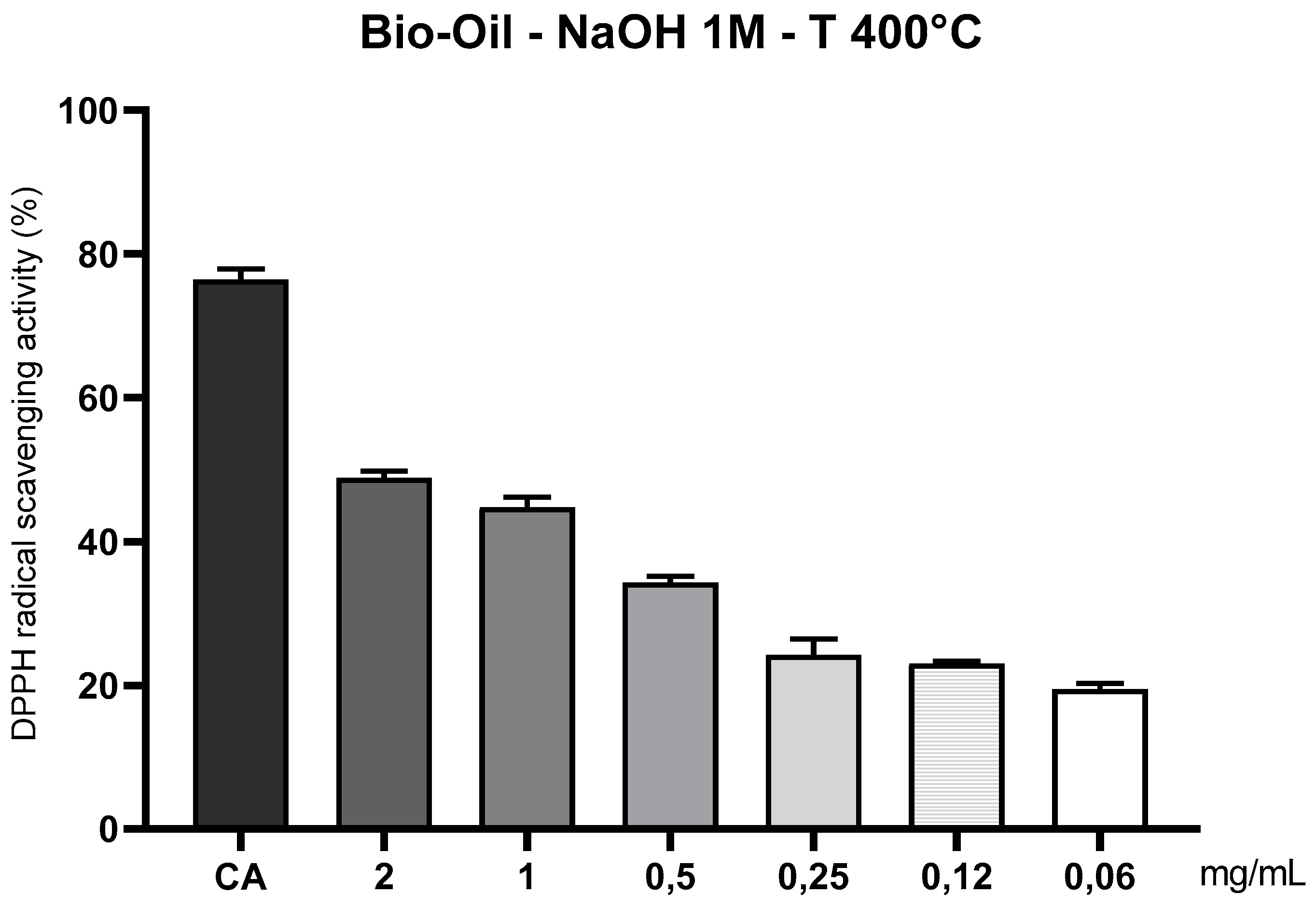

3.10.5. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Capacity of the Organic Fraction of Bio-Oil, Obtained by Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1.0 M NaOH at 400°C, Using the DPPH• Radical Method (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl)

The organic fraction of the bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí pits activated with 1M NaOH at 400 °C exhibited moderate antioxidant activity in the assay with the stable DPPH• radical. Compared to the bio-oil generated at 350 °C (

Figure 11), the radical scavenging capacity was visibly reduced, especially at intermediate and low concentrations, indicating a partial loss of antioxidant efficacy.

Figure 15.

Antioxidant capacity of açaí seed bio-oil (1M NaOH) by the DPPH• method at 400°C. Legend*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (400°C), through the DPPH• sequestration method. Control: caffeic acid (CA) 200 µg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL.

Figure 15.

Antioxidant capacity of açaí seed bio-oil (1M NaOH) by the DPPH• method at 400°C. Legend*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (400°C), through the DPPH• sequestration method. Control: caffeic acid (CA) 200 µg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL.

This behavior can be explained by the fact that higher temperatures, such as 400 °C, promote the fragmentation and thermal degradation of phenolic compounds and oxygenated carboxylic acids, which are primarily responsible for neutralizing free radicals. Under this thermal condition, pyrolysis tends to produce a liquid fraction with a lower density of antioxidant functional groups (such as –OH and –COOH) and a higher proportion of nonpolar compounds, including condensed aromatic structures with high molecular mass and low reducing reactivity.

Although alkaline activation with 1M NaOH initially contributed to the depolymerization of lignin and the release of antioxidant precursors, the thermal intensity at 400 °C exceeded the stability threshold of many of these compounds, promoting their thermal degradation or transformation into less functional structures. As a result, the obtained bio-oil presents a less functionalized chemical profile, which explains the decreased antioxidant activity against the DPPH• radical, especially at lower concentrations (≤ 0.25 mg/mL), where activity was statistically lower than the control (caffeic acid – 200 µg/mL) (p < 0.05). The bio-oil response was clearly dose-dependent, with more pronounced effects at concentrations of 2 and 1 mg/mL. However, even at these higher concentrations, scavenging values remained below the control, confirming the reduction in antioxidant efficacy as a function of temperature.

Furthermore, it is important to highlight that the DPPH• method is more sensitive to short-chain hydrophilic compounds, such as simple phenols and phenolic acids, and less responsive to nonpolar or high molecular weight compounds—traits more prevalent in bio-oils produced at elevated temperatures [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Scarpa et al. [

18], when investigating bio-oils, demonstrated that the absence of a catalytic deoxygenation process in bio-oils pyrolyzed at 400 °C maintains the predominance of poorly reactive aromatic fragments, compromising their antioxidant performance. This reinforces that at high temperatures, even chemically activated bio-oils may not fully express their antioxidant capacity without subsequent chemical modification steps [

18]. Therefore, the results indicate that açaí bio-oil pyrolyzed at 400 °C exhibits limited antioxidant activity in the DPPH• system, resulting from the combination of the loss of antioxidant functional groups and increased structural hydrophobicity of the compounds present in the liquid fraction.

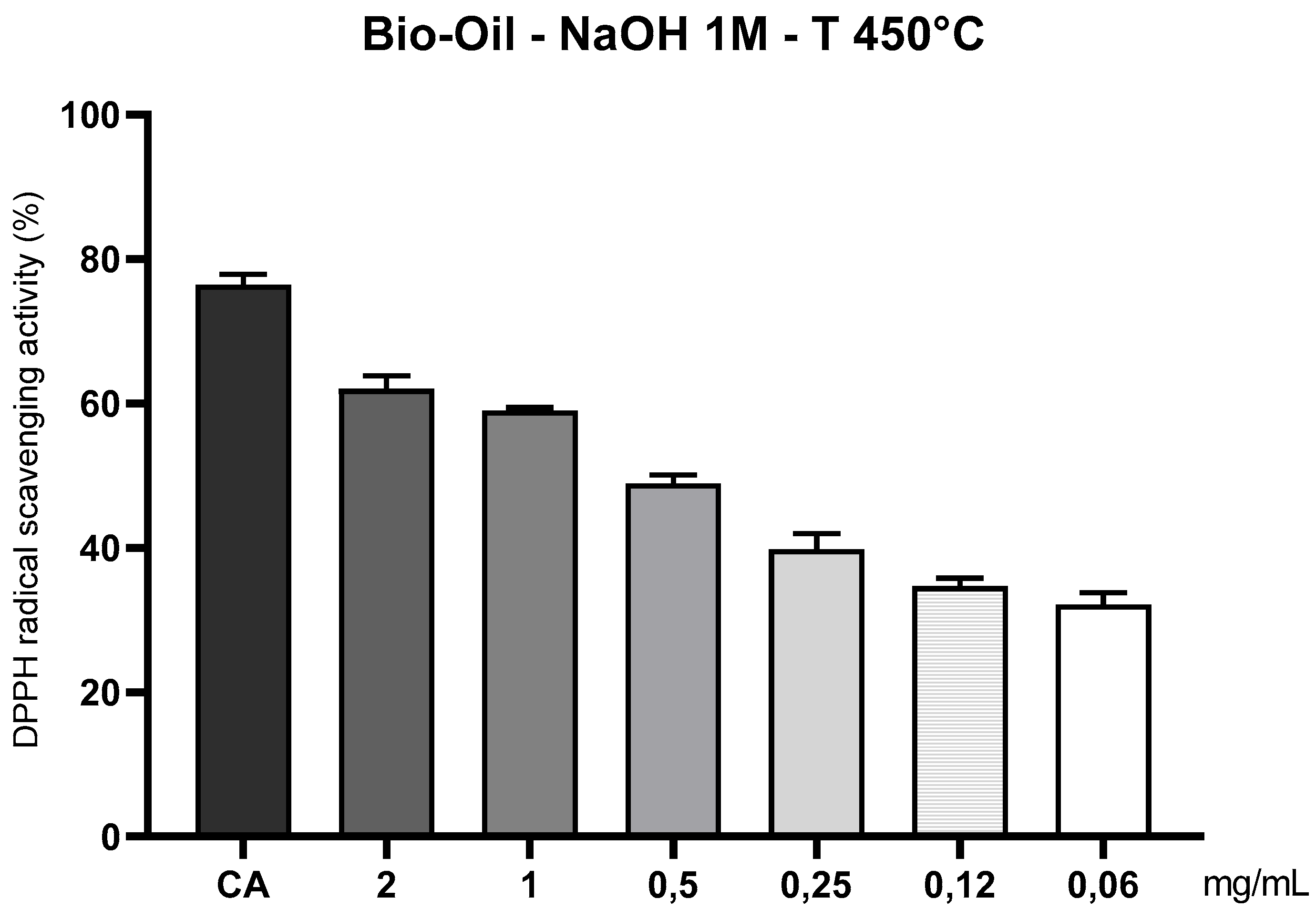

3.10.6. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Capacity of the Organic Fraction of Bio-Oil, Obtained by Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1.0 M NaOH at 450°C, Using the DPPH• Radical Method (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl)

The analysis of the antioxidant capacity of the organic fraction of bio-oil obtained via thermal pyrolysis of açaí pits activated with sodium hydroxide (1M NaOH) at 450 °C (

Figure 12) revealed significant residual activity at high concentrations, suggesting the presence of thermo-stable phenolic compounds still active even under severe thermal conditions. Specifically, at concentrations of 2 and 1 mg/mL, measurable antioxidant activity against the DPPH• radical was observed, although lower than the reference standard (caffeic acid – 200 µg/mL). This performance can be attributed to the presence of alkylated phenols and stable aromatic acids formed during the advanced thermal degradation of the biomass [

20]. The alkaline activation with 1M NaOH contributed to the breaking of bonds between lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose, promoting the release of antioxidant compounds in the liquid phase of the bio-oil. However, the high temperature of 450 °C also caused degradation and condensation of a considerable portion of these compounds, resulting in a chemical matrix composed of polycyclic aromatic structures, hydrocarbons, and fragments with a low density of hydrogen-donating groups [9;26].

Antioxidant efficacy drastically decreased at intermediate and low concentrations (≤ 0.5 mg/mL), with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to the control. This pattern confirms the dependence of antioxidant response on the concentration of active compounds, as well as indicating that the thermal process at 450 °C exceeded the stability threshold of most natural antioxidants formed during pyrolysis [

23]. As observed by Valois et al. (2024), bio-oils produced without complementary fractionation treatment or polarity control can lose up to 50% of their antioxidant activity against the DPPH• radical.

Another relevant factor is that the DPPH• method is more sensitive to water-soluble and short-chain compounds, such as phenolic acids, which limits the response to nonpolar or high molecular weight compounds predominant in bio-oils produced at elevated temperatures. Thus, even with alkaline activation, the nature of the compounds generated at 450 °C—less oxygenated, more nonpolar, and condensed, compromises affinity with the DPPH• radical, reducing neutralization efficiency [25;26]. Nevertheless, the presence of residual antioxidant activity at higher concentrations demonstrates that controlled pyrolysis with chemical activation still allows the formation of thermo-stable bioactive compounds, suggesting potential for industrial applications, such as antioxidant additives in cosmetic, food, or fuel formulations. To enhance this potential, it is recommended to apply complementary characterization techniques, such as liquid chromatography or mass spectrometry, for detailed identification of the phenolic compounds present and optimization of pyrolysis conditions to maximize the functional utilization of the residual biomass.

Figure 16.

Antioxidant capacity of açaí seed bio-oil (1 M NaOH) by the DPPH• method at 450°C. Caption*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1 M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (450°C), through the DPPH• sequestration method. Control: caffeic acid (CA) 200 µg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL.

Figure 16.

Antioxidant capacity of açaí seed bio-oil (1 M NaOH) by the DPPH• method at 450°C. Caption*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1 M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (450°C), through the DPPH• sequestration method. Control: caffeic acid (CA) 200 µg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL.

4. Conclusions

The pre-drying of the biomass proved effective in significantly reducing the moisture content, achieving a yield of 65% and removing 35% of the mass as water. This moisture removal is essential to optimize the energy efficiency of subsequent thermal processes, such as pyrolysis, as it reduces the energy consumption dedicated to evaporation, improving the overall performance of biomass treatment. The results confirm that açaí pits possess chemical characteristics suitable for thermochemical processes, with a high volatile matter content, low ash content, and a significant fixed carbon percentage. This composition favors efficient energy conversion and the production of quality biochar, highlighting the potential of açaí pits as a sustainable source for energy generation and value-added inputs. The results show that impregnation with NaOH, combined with the increase in temperature, favored gas formation and reduced bio-oil yield at the lower temperatures (350°C and 400°C) due to thermal cracking and dehydration reactions. At 450°C, a better balance was observed, with higher bio-oil yield and reduced biochar, indicating that this temperature is more suitable for maximizing liquid production. Overall, NaOH acted as a catalyst and activating agent, promoting the conversion of condensable compounds into gases and contributing to the efficient degradation of lignocellulosic biomass.

The results demonstrate that increasing the pyrolysis temperature, combined with impregnation with 1M NaOH, significantly influences the physicochemical properties of the bio-oils and aqueous phase obtained from açaí pits. A progressive reduction in the bio-oil acidity index was observed with increasing temperature, indicating greater conversion of oxygenated compounds into hydrocarbons. The bio-oil density showed slight variation, while that of the aqueous phase remained constant, suggesting stability in the composition of water-soluble compounds. Bio-oil viscosity peaked at 400°C, reflecting the formation of more complex compounds, and decreased at 450°C due to the thermal breakdown of these compounds. In general, 450°C proved to be more efficient for obtaining bio-oils with lower acidity and viscosity, desirable characteristics for future energy applications. FTIR analysis of the bio-oil produced by pyrolysis of açaí pits impregnated with 1M NaOH confirmed the presence of aliphatic, aromatic, and oxygenated compounds such as alcohols, ethers, and carbonyls. Alkaline impregnation influenced the chemical composition, favoring the formation of functional groups that may enhance bio-oil properties for energy and industrial applications.

Impregnation of açaí pits with 1M NaOH significantly influences bio-oil composition, favoring the formation of oxygenated compounds over hydrocarbons. This effect intensifies with increasing temperature, especially at 450°C, where acids, phenols, ketones, and esters predominate. Therefore, the process leads to bio-oils with a high oxygen content, with potential applications in the chemical industry and second-generation biofuel production. The FTIR spectrum of biochar from açaí pits impregnated with 1M NaOH reveals the presence of characteristic functional groups such as aliphatic chains, unsaturated compounds, and aromatic structures. The observed bands indicate that NaOH impregnation influenced the formation and stability of oxygenated and aromatic groups, as well as promoted modifications in the biochar structure, resulting in a material with potential applications in adsorption, catalysis, or improvement of physicochemical properties. The bio-oil obtained by pyrolysis of açaí pits at 350 °C with alkaline activation using 1M NaOH showed the highest antioxidant activity among the tested conditions, comparable to ascorbic acid at high concentrations. This performance is attributed to the preservation of bioactive phenolic and oxygenated compounds, favored by moderate pyrolysis and chemical activation, which together promote the release of molecules with high reducing potential. The effect was dose-dependent, with greater efficacy at higher concentrations, confirming the potential of the bio-oil as a natural antioxidant agent.

Overall, the results indicate that the organic fraction of bio-oil from açaí pits activated with 1M NaOH exhibits relevant antioxidant activity, especially when obtained at 350 °C, a condition that favors the preservation of bioactive phenolic and oxygenated compounds. As temperature increases (400 and 450 °C), a significant reduction in this activity is observed, associated with the thermal degradation of antioxidant functional groups and the formation of more nonpolar and less reactive compounds. Despite this, at high concentrations, bio-oil maintains residual activity, indicating potential for antioxidant applications, especially when combined with purification or fractionation processes.

Author Contributions

The individual contributions of all the co-authors are provided as follows: (A.C.F.B.) contributed with formal analysis and writing original draft preparation, investigation and methodology, (H.J.d.S.R.) contributed with investigation and methodology, (L.H.H.G.) contributed with investigation and methodology, (F.P.d.C.A.) contributed with formal analysis, investigation and methodology, (R.M.P.S.) contributed with investigation and methodology, (M.S.C.d.N.) contributed with investigation and methodology, (G.A.d.C.M.) contributed with investigation and methodology, (T.J.M.P.) contributed with investigation and methodology, (L.P.B.) contributed with formal analysis, investigation and methodology, (D.A.R.d.C.) contributed with formal analysis, (S.D.J.) contributed with resources, (E.d.C.D.) contributed with investigation and methodology, (S.M.d.S.) contributed with investigation and methodology, (L.d.S.G.) contributed with investigation and methodology, (B.A.Q.G.) contributed with formal analysis, investigation and methodology, (M.C.M.) contributed formal analysis, supervision, investigation and methodology, (N.T.M.) contributed with supervision, conceptualization, and data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Methodological scheme applied in the research.

Figure 1.

Methodological scheme applied in the research.

Figure 3.

Açaí seeds after physical pre-treatment. Legend: seeds + fibers (a); seeds + dry fibers (b); comminuted seeds (c).

Figure 3.

Açaí seeds after physical pre-treatment. Legend: seeds + fibers (a); seeds + dry fibers (b); comminuted seeds (c).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of the effect of reaction time on the hydrocarbon content during the upgrading of pyrolysis vapors of açaí seeds chemically activated with 1.0 molar NaOH, at temperatures of 350°C, 400°C and 450°C, under pressure of 1.0 atmosphere, using a fixed bed catalytic reactor on a laboratory scale.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of the effect of reaction time on the hydrocarbon content during the upgrading of pyrolysis vapors of açaí seeds chemically activated with 1.0 molar NaOH, at temperatures of 350°C, 400°C and 450°C, under pressure of 1.0 atmosphere, using a fixed bed catalytic reactor on a laboratory scale.

Figure 5.

Acidity index of bio-oil and aqueous phase obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea, Mart) impregnated at 450°C, 400°C and 350°C under 1.0 atmosphere. Legend*: I.A = Acid Value; T= temperature.

Figure 5.

Acidity index of bio-oil and aqueous phase obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea, Mart) impregnated at 450°C, 400°C and 350°C under 1.0 atmosphere. Legend*: I.A = Acid Value; T= temperature.

Figure 6.

Density of bio-oil and aqueous phase obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea, Mart) impregnated at 450°C, 400°C and 350°C under 1.0 atmosphere. Legend*: T= temperature.

Figure 6.

Density of bio-oil and aqueous phase obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea, Mart) impregnated at 450°C, 400°C and 350°C under 1.0 atmosphere. Legend*: T= temperature.

Figure 7.

Viscosity of bio-oil and aqueous phase obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea, Mart) impregnated at 450°C, 400°C and 350°C under 1.0 atmosphere. Legend*: T= temperature.

Figure 7.

Viscosity of bio-oil and aqueous phase obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds (Euterpe oleracea, Mart) impregnated at 450°C, 400°C and 350°C under 1.0 atmosphere. Legend*: T= temperature.

Figure 8.

FT-IR of bio-oil obtained by thermal pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with NaOH at 1M at 450 °C, 1.0 atmosphere, on a laboratory scale.

Figure 8.

FT-IR of bio-oil obtained by thermal pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with NaOH at 1M at 450 °C, 1.0 atmosphere, on a laboratory scale.

Figure 9.

Effect of temperature on chemical composition, expressed in hydrocarbons and oxygenates.

Figure 9.

Effect of temperature on chemical composition, expressed in hydrocarbons and oxygenates.

Figure 10.

FT-IR of biochar obtained by thermal pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with NaOH at 1M at 400 °C, 1.0 atmosphere, on a laboratory scale.

Figure 10.

FT-IR of biochar obtained by thermal pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with NaOH at 1M at 400 °C, 1.0 atmosphere, on a laboratory scale.

Figure 11.

Scavenging capacity of the ABTS•+ radical by bio-oil from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH at 350°C. Legend: * Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1 M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (350°C), through the ABTS+ sequestration method. Control: ascorbic acid (AA) 2 mg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference, determined by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05), compared with the control (AA).

Figure 11.

Scavenging capacity of the ABTS•+ radical by bio-oil from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH at 350°C. Legend: * Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1 M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (350°C), through the ABTS+ sequestration method. Control: ascorbic acid (AA) 2 mg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference, determined by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05), compared with the control (AA).

Figure 12.

Scavenging capacity of the ABTS•+ radical by bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH at 400°C. Caption*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (400°C), using the ABTS+ scavenging method. Control: ascorbic acid (AA) 2mg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference, determined by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05), compared to the control (AA).

Figure 12.

Scavenging capacity of the ABTS•+ radical by bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH at 400°C. Caption*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (400°C), using the ABTS+ scavenging method. Control: ascorbic acid (AA) 2mg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference, determined by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05), compared to the control (AA).

Figure 13.

Scavenging capacity of the ABTS•+ radical by bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH at 450°C. Legend*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (450°C), using the ABTS+ scavenging method. Control: ascorbic acid (AA) 2mg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference, determined by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05), compared with the control (AA).

Figure 13.

Scavenging capacity of the ABTS•+ radical by bio-oil obtained from the pyrolysis of açaí seeds impregnated with 1M NaOH at 450°C. Legend*: Antioxidant activity of açaí seed bio-oil activated with 1M NaOH and obtained by pyrolysis (450°C), using the ABTS+ scavenging method. Control: ascorbic acid (AA) 2mg/mL; Bio-oil: 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.12 and 0.06 mg/mL. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference, determined by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05), compared with the control (AA).

Table 1.

Results obtained in the drying and comminution process of açaí seeds.

Table 1.

Results obtained in the drying and comminution process of açaí seeds.

| Data |

Drying |

Comminution |

| Initial Mass [kg] |

21 |

13.7 |

| Final Mass [kg] |

13.7 |

13.4 |

| Yield [%] |

65 |

97.1 |

| Moisture [%] |

35 |

- |

Table 2.

Physical characterization of açaí seeds.

Table 2.

Physical characterization of açaí seeds.

| Analysis |

Dry lumps |

[27] |

[28] |

[29] |

| Volatile material content [%] |

81.63 |

85.98 |

80.77 |

80.35 |

| Ash content [%] |

1.38 |

1.29 |

0.69 |

1.15 |

| Fixed carbon [%] |

17 |

17.21 |

18.50 |

18.50 |

Table 3.

Mass balance of the açaí seed pyrolysis process.

Table 3.

Mass balance of the açaí seed pyrolysis process.

| Process parameters |

NaOH (1M) |

| 350 [°C] |

400 [°C] |

450 [°C] |

0.0

(wt.) |

0.0

(wt.) |

0.0

(wt.) |

| Massa de caroços de açaí [g] |

200 |

1000 |

1000 |

| Tempo de pirólise [min] |

30 |

30 |

30 |

| Temperatura Inicial de Pirólise [°C] |

266 |

220 |

257 |

| Mass of solids (biochar) [g] |

67.27 |

297.68 |

264.41 |

| Mass of bio-oil [g] |

17.08 |

69.95 |

102.25 |

| Mass of H2O [g] |

59.91 |

285.54 |

289.83 |

| Mass of gas [g] |

55.72 |

347.76 |

343.76 |

| Yield of bio-oil [%] |

8.54 |

7.0 |

10.22 |

| Yield of H2O [%] |

29.95 |

28.54 |

28.98 |

| Yield of biochar [%] |

33.63 |

29.75 |

26.44 |

| Yield of gas [%] |

27.86 |

34.76 |

34.37 |

Table 4.

Determination of the Acidity Index of Bio-oil and Aqueous Phase Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1 M NaOH at Temperatures of 350°C, 400°C and 450°C.

Table 4.

Determination of the Acidity Index of Bio-oil and Aqueous Phase Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1 M NaOH at Temperatures of 350°C, 400°C and 450°C.

| Physicochemical Properties |

Temperature |

| Acid Index |

350 °C |

400 °C |

450 °C |

I.ABio-Oil

[mg KOH/g] |

40.84 |

28.58 |

14.02 |

| I.AAqueous Phase [mg KOH/g] |

53.84 |

29.76 |

33.39 |

Table 5.

Determination of the Density of Bio-oil and Aqueous Phase Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1 M NaOH at Temperatures of 350°C, 400°C and 450°C.

Table 5.

Determination of the Density of Bio-oil and Aqueous Phase Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1 M NaOH at Temperatures of 350°C, 400°C and 450°C.

| Physicochemical Properties |

Temperature |

| Density |

350 °C |

400 °C |

450 °C |

| Density Bio-Oil [g/cm³] |

1.01 |

1.02 |

0.973 |

| DensityAqueous Phase [g/cm³] |

1.03 |

1.03 |

1.03 |

Table 6.

Determination of the Viscosity of Bio-oil and Aqueous Phase Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1 M NaOH at Temperatures of 350°C, 400°C and 450°C.

Table 6.

Determination of the Viscosity of Bio-oil and Aqueous Phase Obtained from the Pyrolysis of Açaí Seeds Impregnated with 1 M NaOH at Temperatures of 350°C, 400°C and 450°C.

| Physicochemical Property |

Temperature |

| Viscosidade cinemática |

350 °C |

400 °C |

450 °C |

| Viscosidade Bio-Oil [mm²/s] |

13.73 |

16.13 |

11.42 |

| ViscosidadeAqueous Phase [mm²/s] |

1.06 |

1.46 |

1.40 |

Table 7.

Quantification of compounds present in bio-oils, expressed in relative area (%), by Gas Chromatography analysis.

Table 7.

Quantification of compounds present in bio-oils, expressed in relative area (%), by Gas Chromatography analysis.

| Temperature [°C] |

Concentration [%area.] |

| Hydrocarbons |

Oxygenated |

| 350 |

39.00 |

61.00 |

| 400 |

34.09 |

65.91 |

| 450 |

32.89 |

67.11 |