1. Introduction

Nipah virus, was first identified during an outbreak (1998-1999) in Malaysia, where it infected 276 people and led to approximately 106 fatalities , case fatality rate (CFR) 38% [

1,

2,

3]. Due to the high CFR and lack of prophylaxis, virus culture requires Biosafety Level 4 facilities. More recently, the virus has been associated with sporadic outbreaks across South and Southeast Asia, notably in Bangladesh, India, and the Philippines [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The CFR in these outbreaks have typically ranged from (40-100)% [

12]. Bangladesh reported its first NiV cases in 2001, since then, NiV has caused 343 cases and 245 deaths (CFR 71%). Since 2001, India has experienced six outbreaks, while Bangladesh has reported nearly annual occurrences [

13,

14]. The human-to-human transmission through respiratory secretions, recurring outbreaks of the virus, high fatality rate, and the absence of vaccines or effective therapeutic treatments underscore its pandemic potential and global health risk [

15].

The World Health Organization (WHO), recognizing the pandemic potential of NiV, has classified it as a priority pathogen for the development of effective vaccines and treatments [

16]. There is currently no approved vaccine for NiV; however, several candidate vaccines are currently in development stage and clinical trials [

17]. Most vaccines are designed to elicit neutralizing antibodies targeting the NiV glycoprotein (NiV-G) or fusion protein (NiV-F) [

18,

19]. To ensure their safety, efficacy, and potential for widespread use, these vaccine candidates must undergo rigorous evaluation through clinical trials, supported by regulatory-compliant laboratory tests and immunoassays to assess immune responses to NiV.

The plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) and virus neutralization test (VNT) have been developed for assessing neutralizing antibodies to evaluate vaccine efficacy [

20,

21,

22]. Both assays require high-containment (BSL-4) laboratories, which limits their accessibility, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and during potential pandemic situations requiring rapid assessment like COVID-19 [

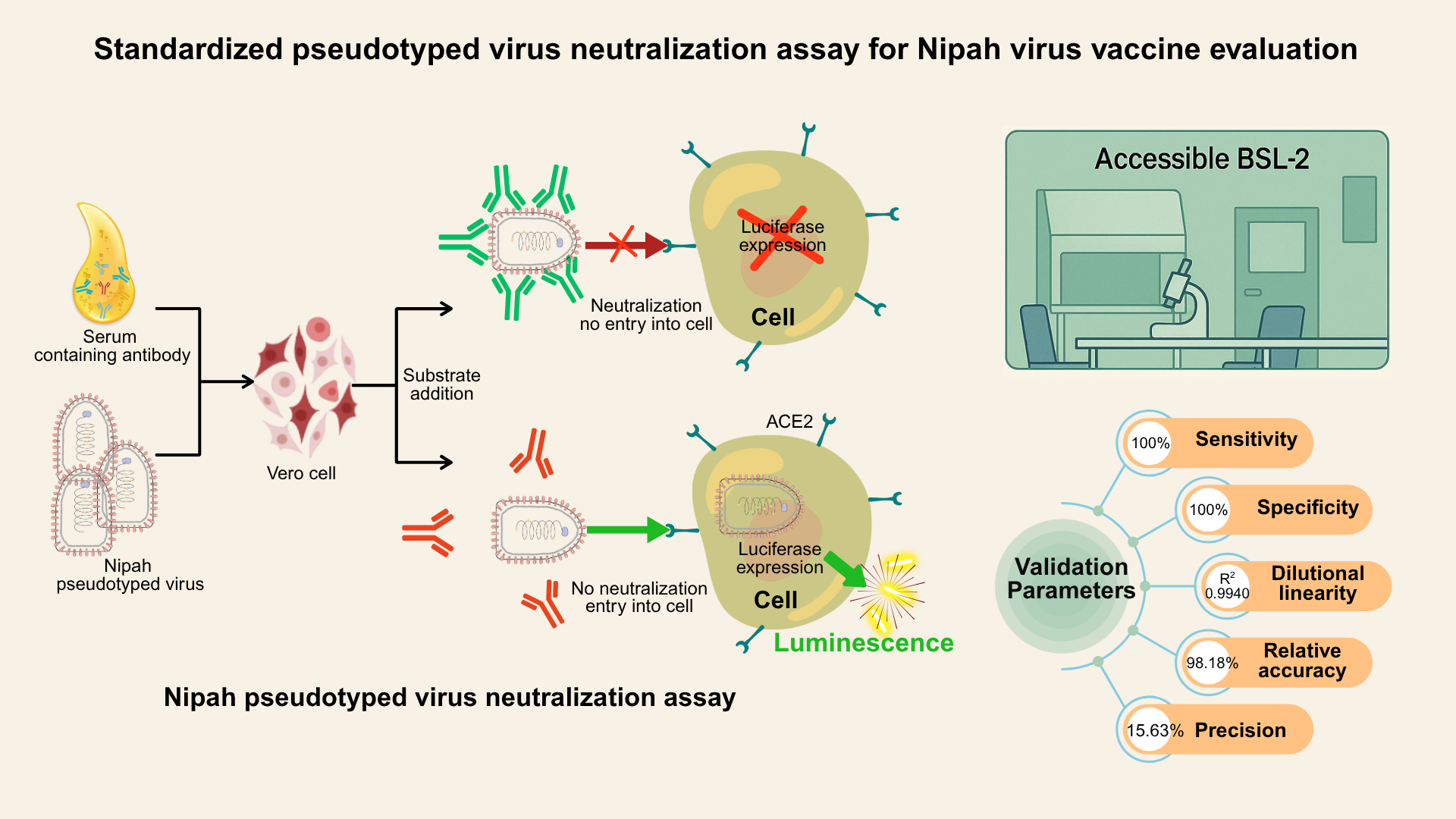

20]. To overcome this challenge, the Nipah pseudotyped virus neutralization assay (NiV-PNA) provides a safer and scalable alternative, as it can be performed in BSL-2 labs while effectively detecting neutralizing antibodies against NiV [

23].

In this study, a standardized and validated NiV-PNA was established. The methodology was implemented at the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) and the technology will be transferred to selected member of the CEPI Centralized Laboratory Network (CLN), which comprises 18 partner laboratories across 13 countries. This global collaboration is expected to accelerate the development of NiV vaccines and enhance preparedness for potential future NiV outbreaks [

16].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell lines

For pseudotyped virus production, HEK-293T/17 cells (NIBSC CFAR catalogue: #5016 or ATCC CRL-11268; provided by MHRA, UK) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, cat. #12800-017) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; Gibco, cat. #16140–071), 1% L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. #G8540), and 2% HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. #H3375).

For NiV-PsV titration and neutralization assay, Vero cells (African green monkey kidney cells, ATCC CCL-81) were used. The Vero cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.8% Fungizone (Amphotericin B; Sigma-Aldrich, cat. #A9528), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, cat. #15140–122, USA), 1% L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich cat. #G8540-100G), 1% sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich cat. #P2256-100G), and 2% HEPES. Cells were incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO₂ and passaged every 3 to 4 days in 100 mm TC-treated cell culture dishes (Corning, cat. #430167). For assay purposes, the same medium was used with 5% FBS.

2.2. Sample panel and reference standards

This study utilized the WHO International Standard (WHO IS) for anti-Nipah virus (anti-NiV) antibodies in neutralization assays (NV-1; NIBSC product code: 22/130_NT), alongside five other reference sera containing anti-NiV antibodies (NV-2, NV-3, NV-4, NV-6, and NV-10) and in addition, we prepared NNV-1, NNV-2, NNV-3, ,and NNV-4 by diluting NV-1 (Table-S1) [

24]. NV-1 served as the high positive assay control, and NV-3 as the low positive assay control. five negative sera (NC-1, NC-2, NC-3, NC-4, NC-5) collected at icddr,b, were confirmed to be free of NiV exposure using reverse transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (rt-PCR) and ELISA (NiV-G protein) following CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta) protocols [

25,

26] (Table-S1).

2.3. Plasmid preparation

The plasmids for the NiV-PsV production, containing codon-optimized NiV-G and NIV-F genes from the NiV Bangladesh isolate (NCBI accession number: JN808864.1) were generously provided by Dr. Edward Wright (University of Sussex, UK) and Professor Teresa Lambe (Oxford Vaccine Group, UK), respectively. These plasmids were transformed into competent

E. coli JM109 cells (Promega, cat no. #L2001) and then plasmid DNA was extracted using a Qiagen midiprep kit (Qiagen, cat. #12145, Germany) [

27,

28].

2.4. Pseudotyped virus production

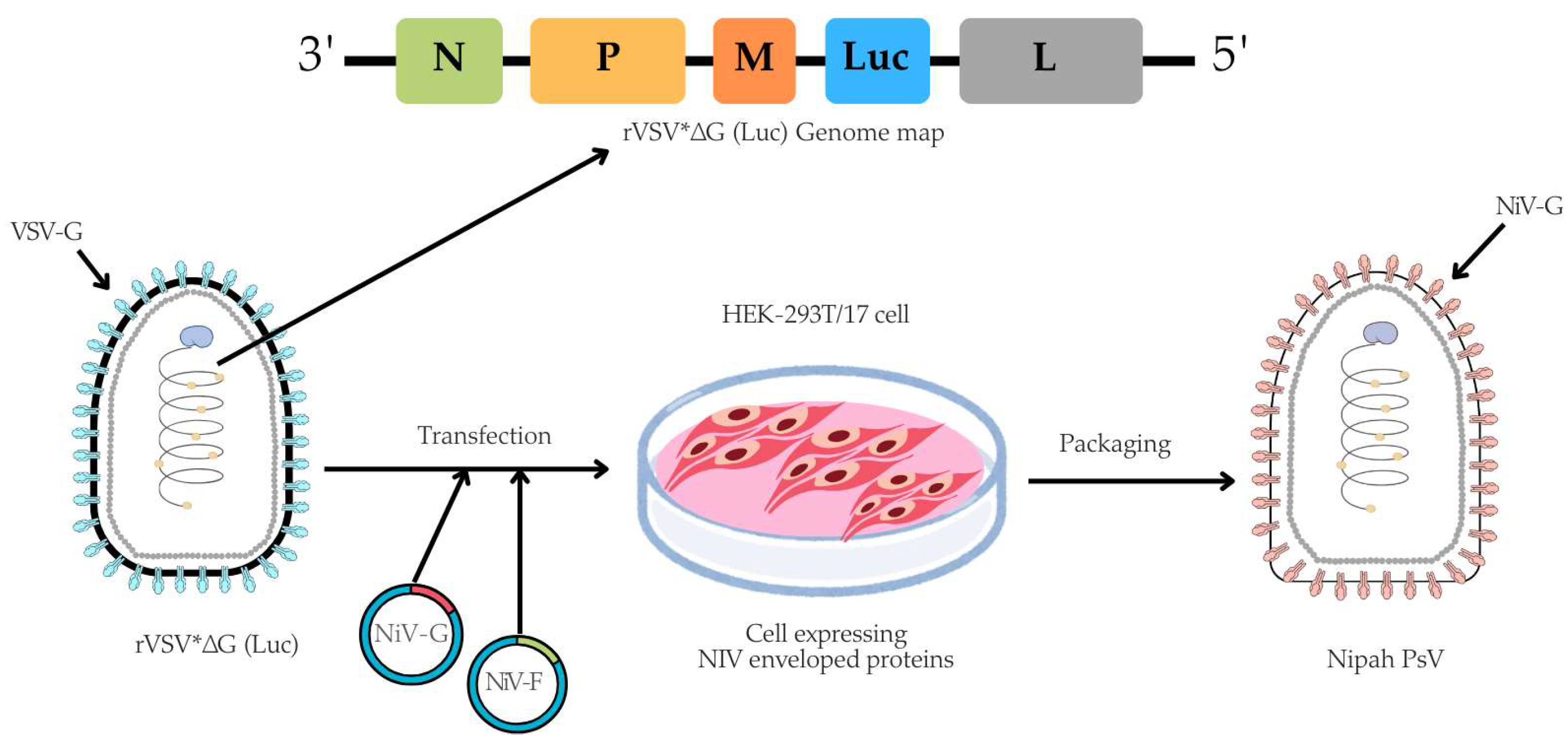

The pseudotyped virus was prepared using a rVSV backbone, in which the VSV glycoprotein (G) gene was replaced with a firefly luciferase (Luc) reporter gene, based on a method originally described by Dr. Michael A. Whitt in 2010 [

29]. In brief, for the NiV-PsV production, HEK-293T/17 cells were cultured in 100 mm TC-treated dishes (4×10

6 cells/dish) (Corning, cat. #430167) overnight at 37°C with 5% CO₂. Next day, once cells reached 50-60% confluency, they were co-transfected with pCAGGS NiV-G and pCAGGS NiV-F expression plasmids using the transfecting agent Polyethylenimine (PEI) (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. #408727). Approximately (20±2) hours post-transfection, the cells were infected with rVSV*ΔG virus (Kerafast, cat. #EH1020-PM) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 (Table-S2). Following (18±2) hours post-infection, NiV-PsV particles were harvested (Figure-1).

Figure-1.

A schematic illustration of NiV-PsV production. The genome map of recombinant Vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV*ΔG), which lacks the VSV envelope G protein and contains an additional firefly luciferase gene (Luc) as a marker, is transfected into cells expressing the Nipah envelope proteins (Glycoprotein, NiV-G and Fusion, NiV-F). Created using Canva and includes elements from the NIH BioArt Vector Library (

https://www.bioart.nih.gov).

Figure-1.

A schematic illustration of NiV-PsV production. The genome map of recombinant Vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV*ΔG), which lacks the VSV envelope G protein and contains an additional firefly luciferase gene (Luc) as a marker, is transfected into cells expressing the Nipah envelope proteins (Glycoprotein, NiV-G and Fusion, NiV-F). Created using Canva and includes elements from the NIH BioArt Vector Library (

https://www.bioart.nih.gov).

Then, the harvested NiV-PsV were filtered through a 0.45 µm syringe filter (Globe Scientific, cat. #SF-CA-4530-S), and centrifuged on a 20% (g/v) sucrose cushion (Fisher Scientific, CAS 57-50-1) in a round bottom, screw cap 10 ml centrifuge-tube (Tarsons, cat. #TARST541020) at 20,000 × g for 6 hours at 4°C. The pelleted NiV-PsV was resuspended in 3 mL PBS and stored at −80°C in aliquots until further use [

23,

29].

2.5. Pseudotyped virus titration

The 50% Tissue Culture Infectious Dose (TCID

50) was determined to quantitate the pseudovirus particle. Vero cells (2×10⁴ cells/well) were seeded in a TC-treated 96-well flat-bottom microplate (Corning, cat. #3917) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for overnight (80-90% confluent). Next day, serial dilution of NiV-PsV virus was performed in a 96-well V-bottom microplate (Corning, cat. #3894) according to plate layout (Figure-S1). After 1-hour incubation, the serially-diluted virus was transferred onto the microplate pre-seeded with Vero cells and incubated overnight (20 ± 2 hours) at 37°C with 5% CO₂. Following incubation, the supernatant was carefully aspirated using an aspirator (SCILOGEX SCIVac Vacuum Aspirator, cat. #761000019999). Subsequently, 50 μL of a 1:1 mixture of ONE-Glo™ EX Luciferase assay reagent (Promega, cat. #E8130, USA), and assay medium was added to each well. Immediately, plates were incubated in a microplate shaker at 600 rpm for 3 minutes at room temperature, and luminescence was measured in Relative Luminescence Units (RLUs) using a multimode plate reader (PerkinElmer Victor Nivo

TM, serial number: HH35L1122076). The TCID

50 of NiV-PsV was determined using the Reed-Muench method [

30].

2.6. Pseudotyped virus-based neutralization assay

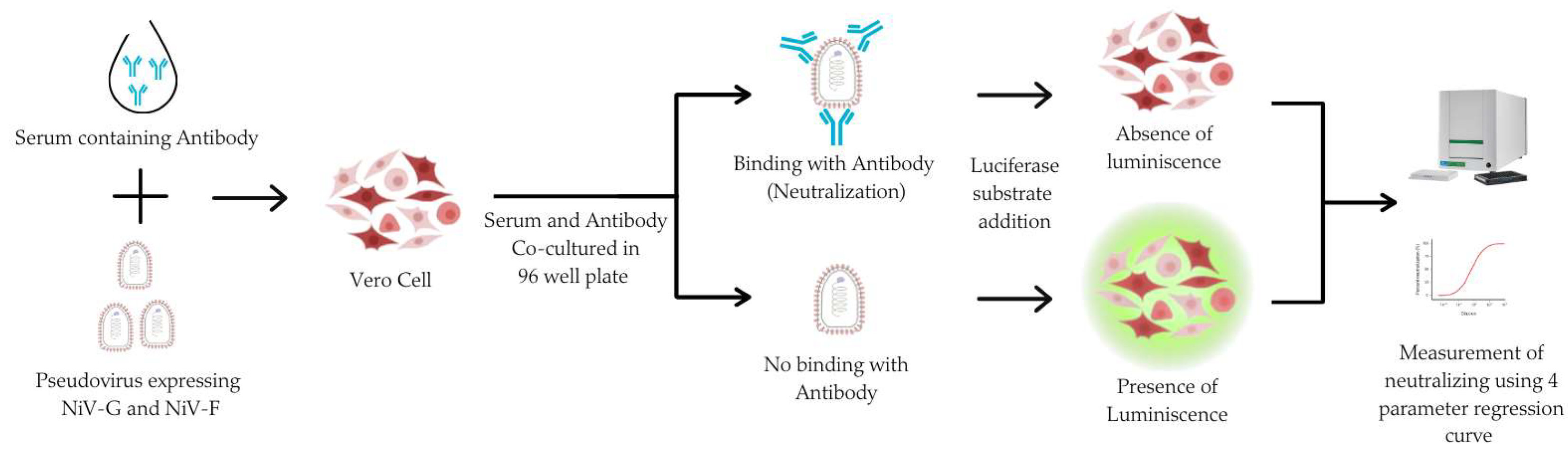

The PNA was developed to assess NiV-specific neutralizing antibodies in human serum. Heat inactivated sera was serially diluted 2-fold in a V-bottom microplate (plate map in Figure-S2) and NiV-PsV (100 TCID₅₀/well) was added to each well, except for cell controls. All the serum samples were tested in duplicate in each plate. Plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 1 hour and the serum-PsV complex were transferred onto the previously seeded microplate with Vero cells (2×10⁴ cells/well). Following incubation at 37°C, with 5% CO₂ for approximately 20 hours, luciferase substrate is added, and plates are read on a luminescence microplate reader. The luminescence intensity inversely correlated with neutralizing antibody present in the serum. Neutralization titers were determined using a 4-parameter logistic regression curve, which represents the dilution required to reduce the RLU signal by 50% relative to that of virus control in the absence of serum (Figure-2).

Figure-2.

The principle of the pseudotyped virus neutralization assay (PNA). Vero cells are incubated with NiV-PsV in the presence of serum. In the absence of neutralizing antibodies, the pseudovirus infects the cells. The addition of substrate results in luminescence. The luminescence signal is detected, and the presence of neutralizing antibodies is quantified using a four-parameter regression curve. Created using Canva and includes elements from the NIH BioArt Vector Library (

https://www.bioart.nih.gov).

Figure-2.

The principle of the pseudotyped virus neutralization assay (PNA). Vero cells are incubated with NiV-PsV in the presence of serum. In the absence of neutralizing antibodies, the pseudovirus infects the cells. The addition of substrate results in luminescence. The luminescence signal is detected, and the presence of neutralizing antibodies is quantified using a four-parameter regression curve. Created using Canva and includes elements from the NIH BioArt Vector Library (

https://www.bioart.nih.gov).

2.7. NiV-PNA validation

Neutralization assay validation was performed in accordance with the “United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Convention General Chapter on Biological Assay Validation (<1033>)” and the “ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology Q2(R1)”, utilizing validated instruments and software [

31,

32,

33]. The potency of the samples was measured in International Units per milliliter (IU/mL) relative to the WHO International Standard (NV-1) for each assay run (Table-S2).

Sensitivity and specificity assessments were conducted using a panel of 5 positive and 5 negative human serum samples for anti-NiV antibodies (Table-S3). And these 5 positive samples considered to be true positive based on the results of the collaborative study [

24]. Inter-laboratory specificity was evaluated by comparing measured results of these 5 positive samples between two laboratories (icddr,b and MHRA) performing NiV-PNA.

Dilutional linearity was evaluated using a two-fold dilution series (1:1 (neat) to 1:32) of three anti-NiV antibody-positive serum samples (Table-S4). Geometric mean titers (GMTs) were calculated for each dilution. A linear regression model was applied to compare serum dilution to GMT, with slope and R² used to assess linearity. Relative accuracy was determined by comparing the observed titers to expected titers (Tables-S2 and S4).

To assess the precision a panel of 10 human serum samples (8 positive and 2 negative) were assessed in duplicate by two analysts over three different days (in parallel). The precision parameters were assessed using the percent geometric coefficient of variation (%GCV) [

24,

34] (Tables-S2 and S5).

The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of this assay was established by generating a calibration curve using a positive human serum sample for anti-NiV neutralizing antibodies. A two-fold serial dilution was performed, spanning from 1:1 (neat) to 1:4096, with each dilution tested in duplicate. The detection limit for neutralizing anti-NiV antibodies in human serum was calculated based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [

35] (Tables-S2 and S6).

The robustness of the assay was evaluated on three anti-NiV antibody-positive serum samples by modifying several parameters: (i) the number of Vero cells in the assay plate (15000, 18000, 20000, 22000, and 25000 cells per well), (ii) the use of two different NiV-PsV lots (Lot-1 and Lot-2), and (iii) variations in the incubation period on day 2 of the NiV-PNA (18, 20, 22, and 24 hours). Sample variability was evaluated using the % GCV (Table-S7).

2.8. Statistical analysis of data

Neutralizing antibody titers in IU/mL unit was determined from the RLUs data using a 4-parameter logistic regression curve, calculated with SoftMax Pro GxP Compliance Software Suite (version 7.1.1). Experimental data was compiled and analyzed by Microsoft Excel 2019. After that, experimental outcomes and analyzed data were visualized by GraphPad Prism (version 9). MedCalc program (version 22.016) was used to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the assays.

3. Results

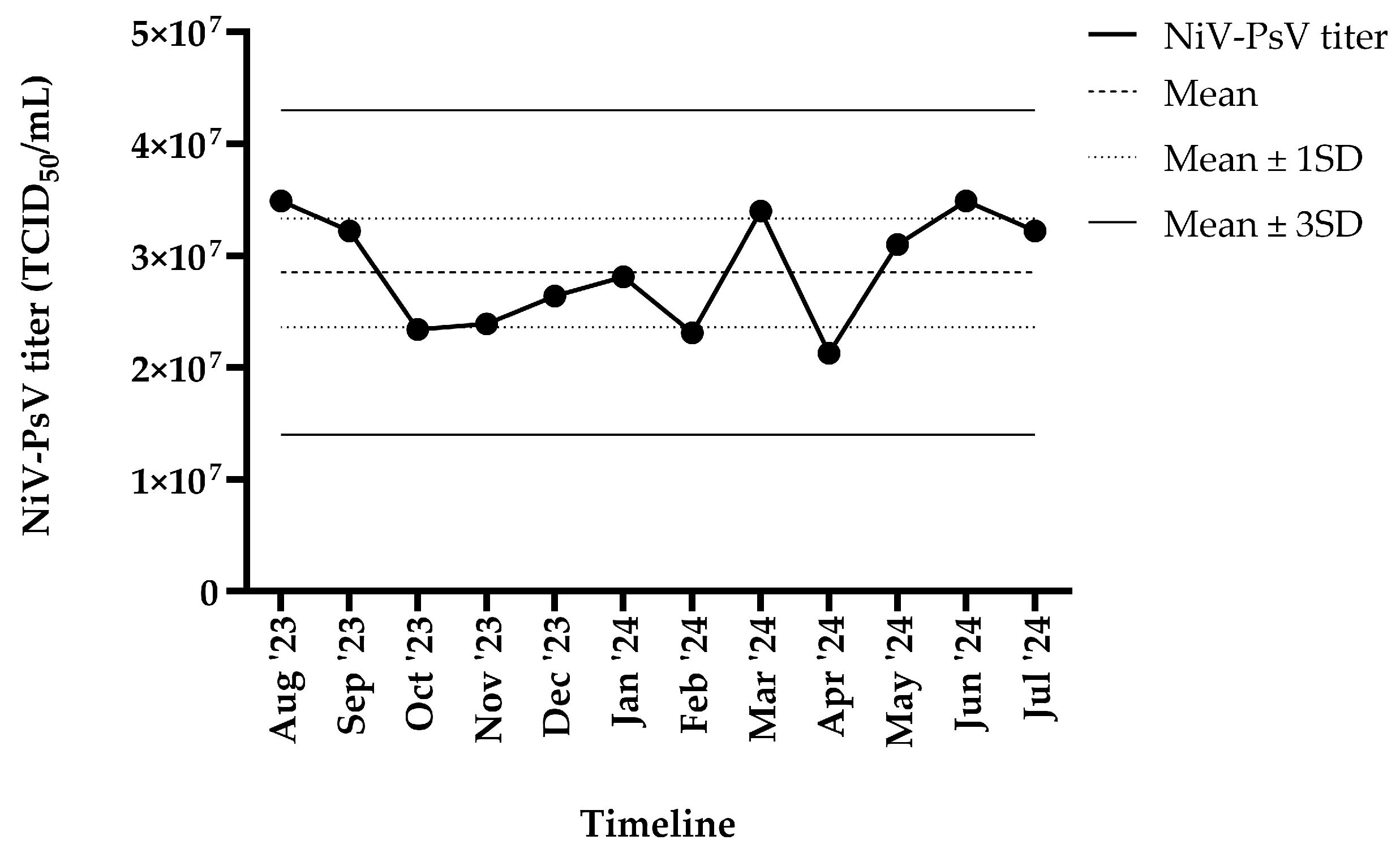

3.1. NiV pseudotyped virus particle production

The harvested NiV-PsV had a titer of >10⁷ TCID₅₀/mL. NiV-PsV titer variability was monitored over a 12-month period (August 2023–July 2024). The overall titer (TCID₅₀/mL) remained within ±3 standard deviation (SD) throughout the timeline (Figure-2).

Figure-2.

NiV-PsV titer variability over 12 months period. The X-axis represents the timeline, and the Y-axis indicates the NiV-PsV titer. The horizontal dashed line represents the mean titer, the dotted line indicates the mean ± 1 SD, and the solid line represents the mean ± 3 SD.

Figure-2.

NiV-PsV titer variability over 12 months period. The X-axis represents the timeline, and the Y-axis indicates the NiV-PsV titer. The horizontal dashed line represents the mean titer, the dotted line indicates the mean ± 1 SD, and the solid line represents the mean ± 3 SD.

3.2. Validation of NiV-PNA

To evaluate the performance of the NiV-PNA using Vero cells, key validation param-eters were assessed based on established acceptance criteria outlined in previously published studies and relevant guidelines [

31,

32,

36]. All criteria were met, confirming reliability and accuracy of the assay under the tested conditions. A summary of the validation outcomes is provided in Table-1.

Table-1.

Acceptance criteria for each validation parameters for validating Nipah pseudotyped virus neutralization assay using Vero cell

Table-1.

Acceptance criteria for each validation parameters for validating Nipah pseudotyped virus neutralization assay using Vero cell

| Parameter |

Acceptance criteria |

Validation

outcome

|

Passed/failed |

| Sensitivity |

≥ 80% |

100% |

Passed |

| Specificity |

≥ 80% |

100% |

Passed |

| Dilutional linearity |

linear regression slope (GMT1, observed vs expected) 0.80 – 1.25 and R2 ≥ 0.95 |

Slope = 1.04;

R2 = 0.9933 |

Passed |

| Relative accuracy |

percent recovery:

(70 – 130)% |

98.18% |

Passed |

Intra assay precision

(Repeatability) |

GCV2 ≤ 30% |

6.66% |

Passed |

Intermediate precision

(Total variability) |

GCV ≤ 30% |

15.63% |

Passed |

3.1.1. Specificity and sensitivity

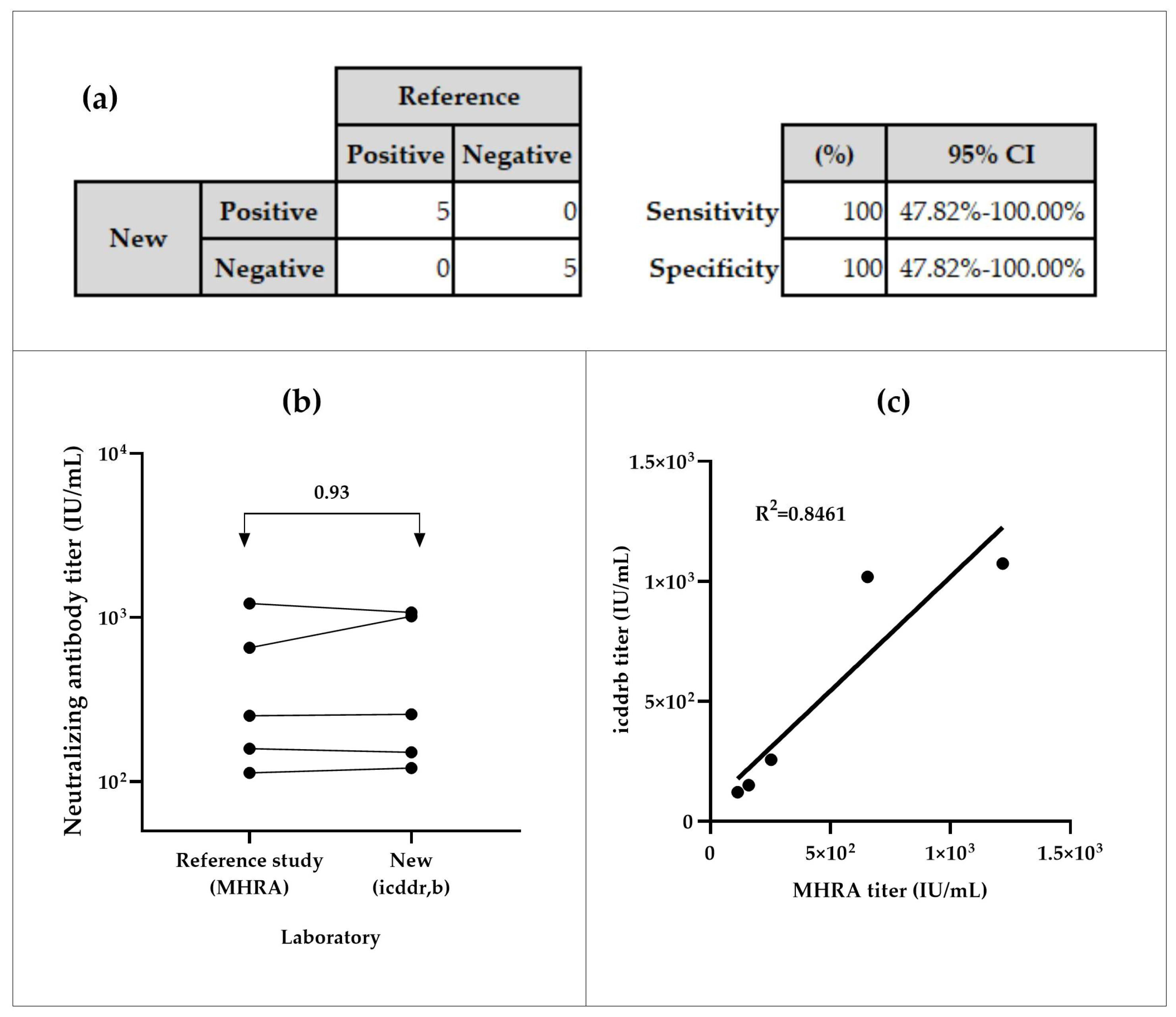

The NiV-PNA demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity in inter-laboratory testing. All positive samples (n=5) were correctly identified as positive, and all negative samples (n=5) as negative, with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of (47.82 – 100)% (Figure-3a). The inter-laboratory comparison of 5 positive samples between icddr,b and MHRA yielded an overall geometric mean ratio (GMR) of 0.93, with individual GMRs ranging from 0.64 to 1.13 (Figure-3b, Table-S3(a)). The coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.8461 was observed between both calibrated assays (Figure-3c).

Figure-3.

Specificity and sensitivity analyses of serum samples from icddr,b and MHRA. (a) Sensitivity of the NiV-PNA assay, based on MedCalc metrics, demonstrated 100% sensitivity in inter-laboratory testing of 5 positive samples between MHRA and icddr,b, with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of 47.82–100.00%. Additionally, 100% specificity was observed in icddr,b testing of 5 negative samples, as confirmed by both ELISA and NiV-PNA results. (b) Geometric mean ratios (GMR) of neutralizing titer (IU/mL) from inter-laboratory comparison, with an overall GMR of 0.93, indicating good correlation between MHRA and icddr,b (c) Correlation of NiV-PNA results in the specificity panel, showing a positive correlation (R² = 0.8461) between measured values.

Figure-3.

Specificity and sensitivity analyses of serum samples from icddr,b and MHRA. (a) Sensitivity of the NiV-PNA assay, based on MedCalc metrics, demonstrated 100% sensitivity in inter-laboratory testing of 5 positive samples between MHRA and icddr,b, with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of 47.82–100.00%. Additionally, 100% specificity was observed in icddr,b testing of 5 negative samples, as confirmed by both ELISA and NiV-PNA results. (b) Geometric mean ratios (GMR) of neutralizing titer (IU/mL) from inter-laboratory comparison, with an overall GMR of 0.93, indicating good correlation between MHRA and icddr,b (c) Correlation of NiV-PNA results in the specificity panel, showing a positive correlation (R² = 0.8461) between measured values.

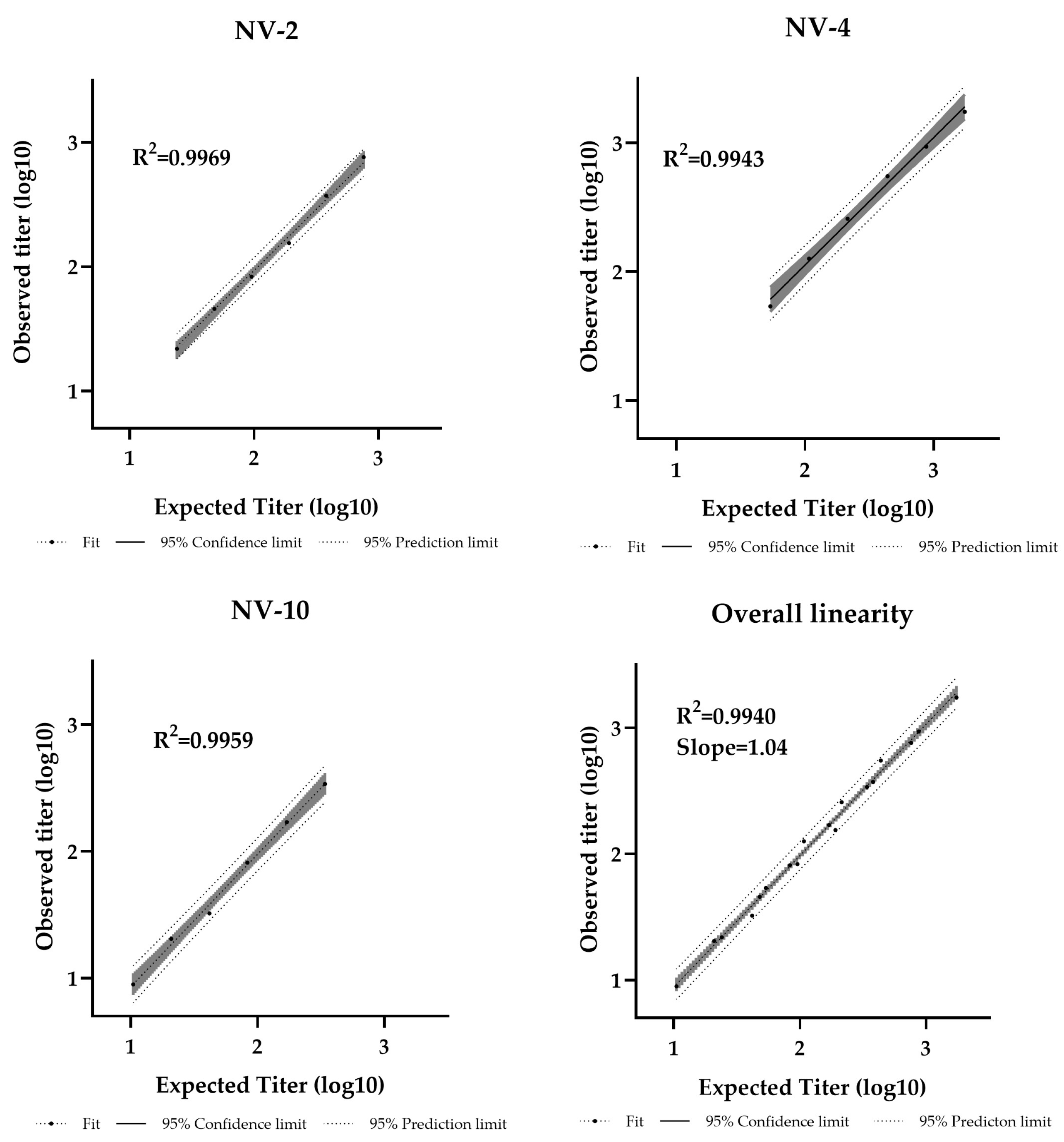

3.1.2. Dilutional linearity

Dilutional linearity was assessed by evaluating the linear regression slope between measured and expected values, with an acceptable range defined as 0.80 – 1.25 [

36]. The assay demonstrated a linear relationship between sample potency and dilution factor within the analytical range of 11–1728 IU/mL (Table-S4). The R² values were 0.9969, 0.9943, and 0.9959 for NV-2, NV-4, and NV-10, respectively, with an overall regression slope of 1.04, confirming strong linearity (Figure-4).

Figure-4.

Pseudotyped virus neutralization assay dilutional linearity of high and low titer samples. High-titer samples (NV-2, NV-4) and a low-titer sample (NV-10) were tested neat and at 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32 dilutions. Overall regression slope is 1.04 and R² = 0.9940.

Figure-4.

Pseudotyped virus neutralization assay dilutional linearity of high and low titer samples. High-titer samples (NV-2, NV-4) and a low-titer sample (NV-10) were tested neat and at 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32 dilutions. Overall regression slope is 1.04 and R² = 0.9940.

3.1.3. Relative accuracy

An assay is considered to have acceptable relative accuracy if the geometric mean (GM) recovery falls within the range of 70–130% [

36]. Across the tested anti-NiV antibody titer (11–1728 IU/mL) for samples NV-02, NV-04, and NV-10, the GM recovery was 98.18%. All dilutions met accuracy criteria, with relative accuracy range from 76.90% to 128.47% (Table-S4).

3.1.4. Precision

Precision was evaluated by measuring the percent geometric coefficient of variation (%GCV). According to US Food and Drug Administration (US-FDA) method validation guidelines, a precision of ≤20% is acceptable for most concentrations, with ≤25% allowed at the LLOQ [

37]. Considering the inherent variability of cell-based pseudotyped virus neutralization assays, a secondary acceptance criterion of ≤30% was applied [

33,

36,

38]. Intra-assay precision (repeatability), yielded an average GCV of 6.66% for the precision panel, while the intermediate precision (total variability), showed a GCV of 15.63% (Table-1). Overall, both the intra-assay precision and intermediate precision are within the threshold (≤30%), confirming that the method meets acceptance criteria.

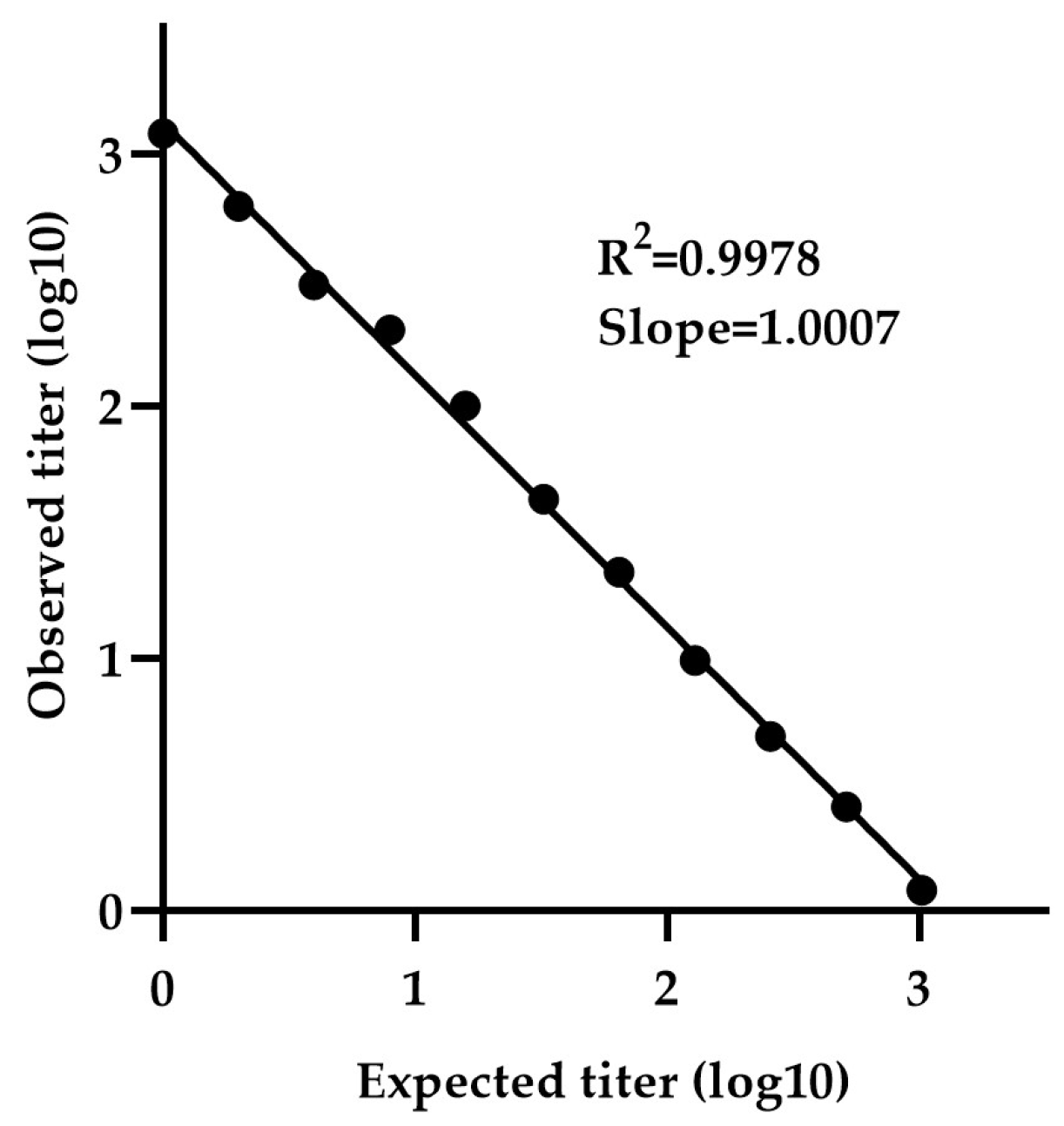

3.1.5. Lower limit of quantification

The minimum detectable concentration was determined using a calibration curve generated by serially diluting sample NV-4 (neat 1:1 to 1:4096) . The calibration curve exhibited a slope (measured vs expected titer) of 1.0007 and R2 value of 0.9978, indicating strong linearity (Figure-5). The LLOQ was calculated to be 2.78 IU/mL, based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope.

Figure-5.

Determination of LLOQ by NiV-PNA using serial dilutions of NV-4. The minimum detectable concentration was determined using a calibration curve generated by serially diluting NV-4 (1:1 to 1:4096). The calibration curve exhibited a slope (measured vs. expected titer) of 1.0007 with an R² value of 0.9978, indicating strong linearity.

Figure-5.

Determination of LLOQ by NiV-PNA using serial dilutions of NV-4. The minimum detectable concentration was determined using a calibration curve generated by serially diluting NV-4 (1:1 to 1:4096). The calibration curve exhibited a slope (measured vs. expected titer) of 1.0007 with an R² value of 0.9978, indicating strong linearity.

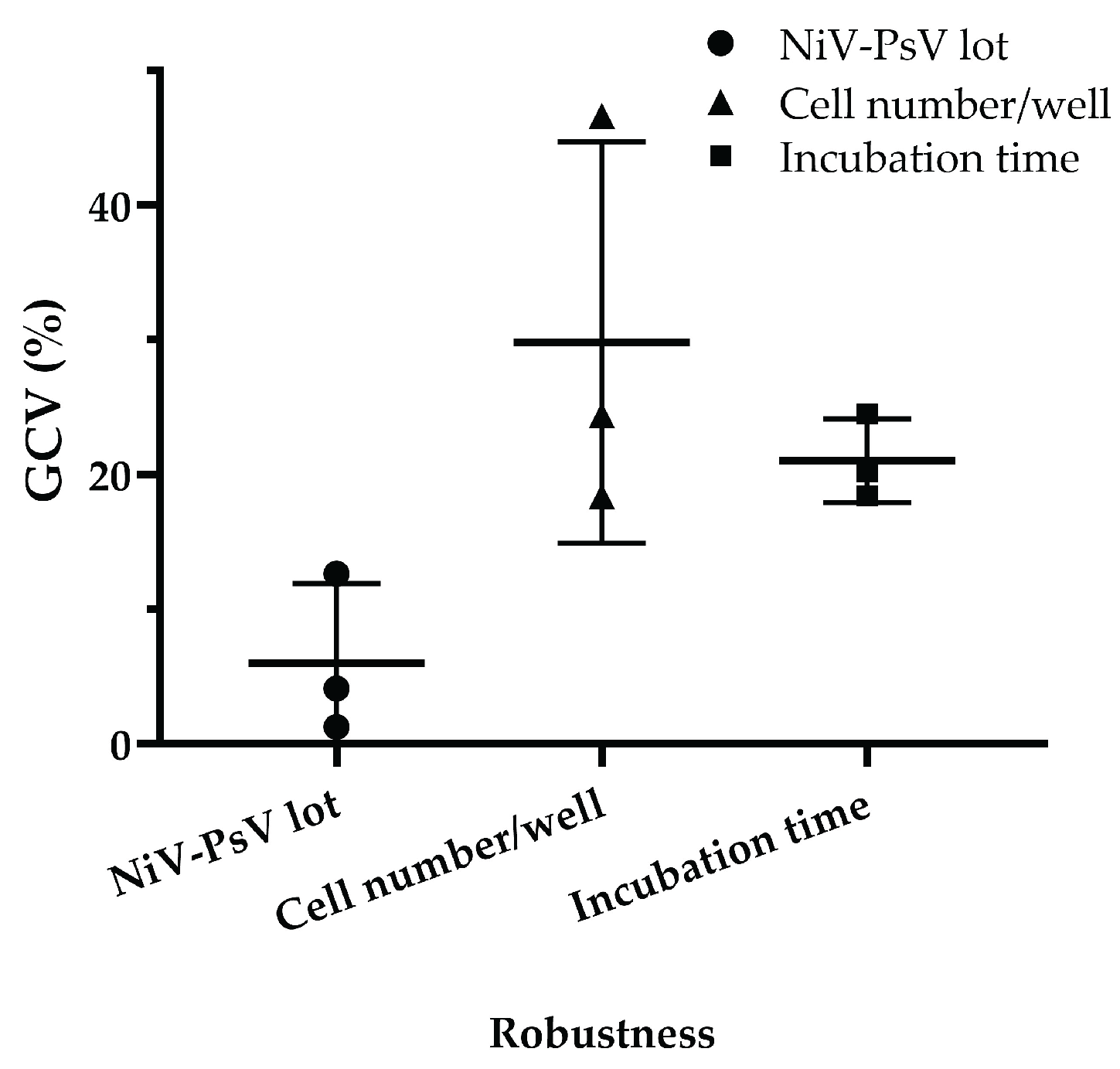

3.1.6. Robustness

The assay demonstrated robustness under varying experimental conditions. Minimal variation was observed when different pseudotyped virus lots were used, with a GCV of 4.03%, which is low considering the inherent variability of cell-based assays [

39]. Variations in incubation time after adding cells to the pseudotyped virus-serum mixture resulted in a GCV of 20.90%, while variations in cell number per well led to a GCV of 27.57%. However, when the cell count was limited to 18000, 20000, and 22000 per well, the GCV decreased to 10.65% (Figure-6), indicating improved consistency under controlled conditions.

Figure-6.

NiV-PNA robustness: Effects of NiV-PsV lot variability, cell number per well, and incubation time on %GCV for NNV-4, NV-2, and NV-4 sera. Robustness was assessed using three anti-NiV antibody-positive serum samples by varying (i) NiV-PsV lot (Lot-1 and Lot-2, GCV = 4.03%), (ii) the number of Vero cells per well (15000–25000, with highest variability at 25000, GCV = 27.57%; reduced to 10.65% when limited to 18000–22000), and (iii) incubation period on day 2 of NiV-PNA (18–24 hours, GCV = 20.90%).

Figure-6.

NiV-PNA robustness: Effects of NiV-PsV lot variability, cell number per well, and incubation time on %GCV for NNV-4, NV-2, and NV-4 sera. Robustness was assessed using three anti-NiV antibody-positive serum samples by varying (i) NiV-PsV lot (Lot-1 and Lot-2, GCV = 4.03%), (ii) the number of Vero cells per well (15000–25000, with highest variability at 25000, GCV = 27.57%; reduced to 10.65% when limited to 18000–22000), and (iii) incubation period on day 2 of NiV-PNA (18–24 hours, GCV = 20.90%).

4. Discussion

We successfully standardized and validated a PNA to assess the neutralizing potency of serum antibodies against NiV, ensuring compliance with international guidelines. This rigorous approach ensures the assay’s reliability and reproducibility for use in serological studies and vaccine evaluation.

To develop the assay, a rVSV-ΔG backbone-based Nipah pseudovirus was utilized. This system was chosen over the lentiviral system due to its ability to generate high-titer PsV particles and high-throughput, ensuring consistency and reliability [

23,

40,

41]. Previous studies by Negrete et al. and Kaku et al. have utilized this rVSV-ΔG platform to investigate the NiV cell entry and serological properties, by incorporating the NiV-G and NiV-F proteins into the pseudotyped virus [

42,

43]. Cai et al. validated a pseudotyped virus neutralization assay to evaluate neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and its Omicron subvariants [

44]. Nie et al. developed Rabies virus neutralization assays, demonstrating high correlation with traditional methods like Rapid Fluorescent Focus Inhibition Test (RFFIT), while offering greater sensitivity and faster results [

45]. Additionally, pseudotyped viruses have been used for CHIKV DNA vaccine evaluation and LASV neutralization assays, aiding vaccine development and comparison studies [

38,

46].

The WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization established an WHO International Standard (WHO IS) for anti-NiV antibody based on collaborative study involving 18 laboratories [

24]. This serves as a key reference for harmonizing serological assays and ensuring result comparability across studies. By calibrating the NiV-PNA against the WHO IS, neutralizing antibody titers can be quantified in International Units (IU), enabling direct comparisons across different studies and platforms in clinical vaccine trials.

The assay demonstrated a positive correlation between neutralizing antibody titers measured in serum samples by the collaborative study and the icddr,b laboratory, confirming its accuracy. Inter-laboratory comparisons between icddr,b and MHRA further demonstrated that the validated assay has good concordance with other calibrated NiV-PNA.

The sensitivity and specificity data indicate that the samples were accurately identified as true positives based on the results presented in the collaborative study report, supporting the reliability of the assay in detecting anti-NiV neutralizing antibodies. The dilutional linearity assessment confirmed that the assay generates consistent results across a range of serum dilutions, supporting its quantitative reliability. Additionally, relative accuracy measurements revealed a high degree of correlation between observed and expected neutralizing antibody titers, ensuring precise titer determination. Precision analysis, evaluated through intra-assay and total variability assessments, indicated minimal variation, further supporting the assay’s reliability across different experimental conditions.

The robustness assessments confirmed that slight variations in standard laboratory conditions did not affect the assay performance. It remained consistent despite minor changes in processing time, Vero cell count, or pseudotyped virus batches. This demonstrates the assay’s ability to withstand common laboratories inconsistencies, such as scheduling delays, cell seeding number differences, and reagent batch variations, ensuring its reliability across different laboratory settings.

Despite the successful standardization and validation of the NiV-PNA, certain limitations should be acknowledged, principally due to limited number and amount of specimen availability from NiV infection survivors. Specifically, we were unable to assess the impact of multiple freeze-thaw cycles on serum stability, nor the potential interference from lipemic or hemolytic samples. Only serum samples were used, and comparison between plasma and serum matrices were not performed. The upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) remain undermined, also due to the limited availability of serum samples. Future studies incorporating a larger and more diverse panel such as vaccinee serum and plasma would be beneficial to address this gap. Considering the limitation of human sera availability, we recommend standardizing other experimental animal sera (e.g., swine) for validation purpose. Additionally, we could not directly compare the NiV-PNA with virus neutralization assay (VNA) using wild-type NiV due to the absence of a BSL-4 laboratory facility. Such a comparative analysis would provide valuable insights into its correlation with the gold-standard method. Future studies should prioritize this comparative analysis to determine whether both assays yield comparable neutralization profiles.

Despite these limitations, this study addresses a critical challenge in NiV research in Bangladesh. The development and validation of NiV-PNA in a country with recurrent NiV outbreaks and considered a potential epicenter for future spillover events, holds significant public health relevance. The assay’s ability to determine neutralizing antibodies without requiring live virus enhances its utility in resource-limited and non-BSL-4 settings, making it a valuable tool for global health preparedness.

Looking forward, we plan to adapt the NiV-PNA for other NiV variants. Given the antigenic diversity of NiV strains, developing assays for multiple variants will facilitate a comprehensive evaluation of immunogenic variability, cross-neutralization potential, and vaccine efficacy. This expansion will be crucial for understanding immunity across different NiV lineages and guiding public health strategies.

The integration of this standardized and validated NiV-PNA into the CEPI-CLN represents a significant advancement in enhancing global health preparedness, facilitating robust vaccine evaluation and outbreak response capabilities. Future studies should explore its application in large-scale epidemiological studies and clinical trials to further strengthen its utility in NiV research and public health preparedness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table-S1: Panel of serum samples for Nipah pseudotyped virus neutralization assay validation, Table-S2: List of formulas used to Nipah pseudotyped virus neutralization assay validation, Table-S3: Comparative analysis of inter-laboratory specificity for anti-NiV neutralizing antibody detection, Table-S4: Evaluation of dilutional linearity and relative accuracy using dilution series (1:1 (neat) to 1:32) of three anti-NiV neutralizing antibody positive serum samples (NV-02, NV-04, and NV-10), Table-S5: For precision assessment: a panel of 10 serum samples covering negative, low, intermediate, and high anti-NiV neutralization antibody titer was tested in duplicate by two analysts over three days. Samples NC-1, NC-2 were not included in the calculations, as both samples were negative, Table-S6: The LLOQ was determined by generating a calibration curve using NV-04, a positive human serum sample for anti-NiV neutralizing antibodies. The LLOQ for neutralizing anti-NiV antibodies in human serum was calculated based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve, Table-S7: Evaluation of assay robustness using three anti-NiV antibody-positive serum samples. Sample variability was evaluated using the %GCV, Figure-S1: Microplate layout- Nipah pseudotyped virus TCID50 determination, Figure-S2: Microplate layout- NiV-PNA in Vero cells.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., M.J.R. and M.R; methodology, A.S, E.B., D.K.S, M.M.A and S.J.; software, M.J.R and M.A.R.; validation, M.J.R, M.A.R, G.K., and A.A.; formal analysis, M.J.R.; investigation, M.A. and M.R.; resources, E.B., R.R. and M.R; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A. and M.J.R.; writing—review and editing, E.B, A.A., M.Z.R, R.R, and M.R.; visualization, M.A., M.J.R, and M.A.R.; supervision, M.R; project administration, R.R, A.A and G.K.; funding acquisition, R.R and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), Oslo, Norway. APC was also funded by CEPI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Direct collection of clinical samples was not required for this study. All serum samples from patients who had recovered from NiV exposure in either Malaysia or Bangladesh were obtained through MHRA [

24], with the collections conducted by Universiti Malaya (Malaysia) and icddr,b (Bangladesh) (Table-S1). The collections received approval from the Universiti Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC) Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC). This validation study was approved by institutional Research Review Committee (RRC) of icddr,b.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this study are available in the article and supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of the International Centre for Diarrheal Diseases Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), for organizational support with the work. icddr,b is grateful to the Governments of Bangladesh, and Canada for providing core/unrestricted support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NiV |

Nipah virus |

| PNA |

Pseudotyped virus neutralization assay |

| NiV-PNA |

Nipah pseudotyped virus neutralization assay |

| rVSV |

recombinant Vesicular stomatitis virus |

| PsV |

Pseudotyped virus |

| NiV-PsV |

Nipah pseudotyped virus |

| BSL-4 |

Biosafety level 4 |

| BSL-2 |

Biosafety level 2 |

| R2

|

Coefficient of determination |

| CFR |

Case fatality rate |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| NiV-G |

Nipah virus glycoprotein |

| NiV-F |

Nipah virus Fusion Protein |

| PRNT |

Plaque reduction neutralization test |

| VNT |

Virus neutralization test |

| LMIC |

Low- and middle-income country |

| icddr,b |

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh |

| CEPI |

Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations |

| CLN |

Centralized Laboratory Network |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| WHO IS |

WHO International Standard |

| Anti-NiV |

anti-Nipah virus |

| rt-PCR |

reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta |

| PEI |

Polyethylenimine |

| MOI |

Multiplicity of infection |

| TCID50

|

The 50% tissue culture infectious dose |

| RLU |

Relative luminescence unit |

| USP |

United States Pharmacopeia |

| IU/mL |

International Units per milliliter |

| GMT |

Geometric mean titer |

| LLOQ |

Lower limit of quantification |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| GMR |

Geometric mean ratio |

| GM |

Geometric mean |

| %GCV |

Percent geometric coefficient of variation |

| US-FDA |

US Food and Drug Administration |

| RFFIT |

Rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test |

| IU |

International Units |

| ULOQ |

Upper limit of quantification |

| UMMC |

Universiti Malaya Medical Centre |

| MREC |

Medical Research and Ethics Committee |

| RRC |

Research Review Committee |

| 1 |

GMT, Geometric mean titer |

| 2 |

GCV, Geometric coefficient of variation |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Outbreak of Hendra-like Virus--Malaysia and Singapore, 1998-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999, 48, 265–269.

- Verma, A.; Jain, H.; Sulaiman, S.A.; Pokhrel, P.; Goyal, A.; Dave, T. An Impending Public Health Threat: Analysis of the Recent Nipah Virus Outbreak and Future Recommendations - an Editorial. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2024, 86, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattu, V.K.; Kumar, R.; Kumary, S.; Kajal, F.; David, J.K. Nipah Virus Epidemic in Southern India and Emphasizing “One Health” Approach to Ensure Global Health Security. J Family Med Prim Care 2018, 7, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.J.; Tan, C.T.; Chew, N.K.; Tan, P.S.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Sarji, S.A.; Wong, K.T.; Abdullah, B.J.; Chua, K.B.; Lam, S.K. Clinical Features of Nipah Virus Encephalitis among Pig Farmers in Malaysia. N Engl J Med 2000, 342, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, K.B.; Goh, K.J.; Wong, K.T.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Tan, P.S.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Zaki, S.R.; Paul, G.; Lam, S.K.; Tan, C.T. Fatal Encephalitis Due to Nipah Virus among Pig-Farmers in Malaysia. Lancet 1999, 354, 1257–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luby, S.P.; Rahman, M.; Hossain, M.J.; Blum, L.S.; Husain, M.M.; Gurley, E.; Khan, R.; Ahmed, B.-N.; Rahman, S.; Nahar, N.; et al. Foodborne Transmission of Nipah Virus, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis 2006, 12, 1888–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, V.P.; Hossain, M.J.; Parashar, U.D.; Ali, M.M.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Kuzmin, I.; Niezgoda, M.; Rupprecht, C.; Bresee, J.; Breiman, R.F. Nipah Virus Encephalitis Reemergence, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis 2004, 10, 2082–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, M.S.; Comer, J.A.; Lowe, L.; Rota, P.A.; Rollin, P.E.; Bellini, W.J.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Mishra, A. Nipah Virus-Associated Encephalitis Outbreak, Siliguri, India. Emerg Infect Dis 2006, 12, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, K.B.; Bellini, W.J.; Rota, P.A.; Harcourt, B.H.; Tamin, A.; Lam, S.K.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Rollin, P.E.; Zaki, S.R.; Shieh, W.; et al. Nipah Virus: A Recently Emergent Deadly Paramyxovirus. Science 2000, 288, 1432–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, P.K.G.; De Los Reyes, V.C.; Sucaldito, M.N.; Tayag, E.; Columna-Vingno, A.B.; Malbas, F.F.; Bolo, G.C.; Sejvar, J.J.; Eagles, D.; Playford, G.; et al. Outbreak of Henipavirus Infection, Philippines, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurley, E.S.; Montgomery, J.M.; Hossain, M.J.; Bell, M.; Azad, A.K.; Islam, M.R.; Molla, M.A.R.; Carroll, D.S.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Rota, P.A.; et al. Person-to-Person Transmission of Nipah Virus in a Bangladeshi Community. Emerg Infect Dis 2007, 13, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nipah Virus Infection - India Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON490 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- NIPAH Situation Dashboard- IEDCR NIPAH Virus Surveillance System Available online:. Available online: https://www.iedcr.gov.bd/site/page/d5c87d45-b8cf-4a96-9f94-7170e017c9ce/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.iedcr.gov.bd%2Fsite%2Fpage%2Fd5c87d45-b8cf-4a96-9f94-7170e017c9ce%2F (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Nipah Virus Infection - Bangladesh Available online:. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON442 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Luby, S.P.; Hossain, M.J.; Gurley, E.S.; Ahmed, B.-N.; Banu, S.; Khan, S.U.; Homaira, N.; Rota, P.A.; Rollin, P.E.; Comer, J.A.; et al. Recurrent Zoonotic Transmission of Nipah Virus into Humans, Bangladesh, 2001–2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, A.; Manak, M.; Bernasconi, V. The CEPI Centralized Laboratory Network for COVID-19 Will Help Prepare for Future Outbreaks. Nat Med 2023, 29, 2684–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, G.; Prajapat, V.; Nayak, D. Advancements in Nipah Virus Treatment: Analysis of Current Progress in Vaccines, Antivirals, and Therapeutics. Immunology 2023, 171, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, R.J.; Stewart-Jones, G.B.E.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Caringal, R.T.; Morabito, K.M.; McLellan, J.S.; Chamberlain, A.L.; Nugent, S.T.; Hutchinson, G.B.; Kueltzo, L.A.; et al. Structure-Based Design of Nipah Virus Vaccines: A Generalizable Approach to Paramyxovirus Immunogen Development. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, E.; Feldmann, F.; Cronin, J.; Goldin, K.; Mercado-Hernandez, R.; Williamson, B.N.; Meade-White, K.; Okumura, A.; Callison, J.; Weatherman, S.; et al. Distinct VSV-Based Nipah Virus Vaccines Expressing Either Glycoprotein G or Fusion Protein F Provide Homologous and Heterologous Protection in a Nonhuman Primate Model. eBioMedicine 2023, 87, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Chen, R.; Ning, T.; Liu, Q.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. Nipah Pseudovirus System Enables Evaluation of Vaccines in Vitro and in Vivo Using Non-BSL-4 Facilities. Emerg Microbes Infect 2019, 8, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riepler, L.; Rössler, A.; Falch, A.; Volland, A.; Borena, W.; von Laer, D.; Kimpel, J. Comparison of Four SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Assays. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manak, M.; Gagnon, L.; Phay-Tran, S.; Levesque-Damphousse, P.; Fabie, A.; Daugan, M.; Khan, S.T.; Proud, P.; Hussey, B.; Knott, D.; et al. Standardised Quantitative Assays for Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Immune Response Used in Vaccine Clinical Trials by the CEPI Centralized Laboratory Network: A Qualification Analysis. The Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, e216–e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, C.; Huang, Y.; Cong, S.; Tan, J.; Hou, W.; Ma, F.; Zheng, L. Establishment of a Neutralization Assay for Nipah Virus Using a High-Titer Pseudovirus System. Biotechnol Lett 2023, 45, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassall, M.; Bentley, E.M.; Cherry, C.; Bernasconi, V.; Atkinson, E.; Rigsby, P.; Page, M.; Yen Chang, L.; Ming Ong, H.; Satter, S.M.; et al. 2023.

- Guillaume, V.; Lefeuvre, A.; Faure, C.; Marianneau, P.; Buckland, R.; Lam, S.K.; Wild, T.F.; Deubel, V. Specific Detection of Nipah Virus Using Real-Time RT-PCR (TaqMan). Journal of Virological Methods 2004, 120, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzola, L.T.; Kelly-Cirino, C. Diagnostics for Nipah Virus: A Zoonotic Pathogen Endemic to Southeast Asia. BMJ Glob Health 2019, 4, e001118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucena-Aguilar, G.; Sánchez-López, A.M.; Barberán-Aceituno, C.; Carrillo-Ávila, J.A.; López-Guerrero, J.A.; Aguilar-Quesada, R. DNA Source Selection for Downstream Applications Based on DNA Quality Indicators Analysis. Biopreserv Biobank 2016, 14, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasel, J.A. Validity of Nucleic Acid Purities Monitored by 260nm/280nm Absorbance Ratios. Biotechniques 1995, 18, 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Whitt, M.A. Generation of VSV Pseudotypes Using Recombinant ΔG-VSV for Studies on Virus Entry, Identification of Entry Inhibitors, and Immune Responses to Vaccines. J Virol Methods 2010, 169, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Yang, J.; Hu, J.; Sun, X. On the Calculation of TCID50 for Quantitation of Virus Infectivity. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1033〉 Biological Assay Validation. [CrossRef]

- Guideline, I.H.T. Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology. Q2 (R1) 2005, 1, 05. [Google Scholar]

- DeSilva, B.; Smith, W.; Weiner, R.; Kelley, M.; Smolec, J.; Lee, B.; Khan, M.; Tacey, R.; Hill, H.; Celniker, A. Recommendations for the Bioanalytical Method Validation of Ligand-Binding Assays to Support Pharmacokinetic Assessments of Macromolecules. Pharm Res 2003, 20, 1885–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas B., L. Kirkwood Geometric Means and Measures of Dispersion. Biometrics 1979, 35, 908–909. [Google Scholar]

-

Validation of Analytical Procedures: Methodology. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Formulations, 2nd ed.; 2021; pp. 1512–1515. [CrossRef]

- Kostense, S.; Moore, S.; Companjen, A.; Bakker, A.B.H.; Marissen, W.E.; von Eyben, R.; Weverling, G.J.; Hanlon, C.; Goudsmit, J. Validation of the Rapid Fluorescent Focus Inhibition Test for Rabies Virus-Neutralizing Antibodies in Clinical Samples. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012, 56, 3524–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fda; Cder Bioanalytical Method Validation Guidance for Industry Biopharmaceutics Bioanalytical Method Validation Guidance for Industry Biopharmaceutics Contains Nonbinding Recommendations; 2018.

- Antonelli, R.; Forconi, V.; Molesti, E.; Semplici, C.; Piu, P.; Altamura, M.; Dapporto, F.; Temperton, N.; Montomoli, E.; Manenti, A. A Validated and Standardized Pseudotyped Microneutralization Assay as a Safe and Powerful Tool to Measure LASSA Virus Neutralising Antibodies for Vaccine Development and Comparison. F1000Res 2024, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atouf, F. USP Standards for Cell-Based Therapies. Cell Therapy 2021, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.E.; Kim, S.S.; Moon, S.T.; Cho, Y.D.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Shin, H.Y.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, Y.B. Construction of the Safe Neutralizing Assay System Using Pseudotyped Nipah Virus and G Protein-Specific Monoclonal Antibody. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2019, 513, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khetawat, D.; Broder, C.C. A Functional Henipavirus Envelope Glycoprotein Pseudotyped Lentivirus Assay System. Virol J 2010, 7, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrete, O.A.; Levroney, E.L.; Aguilar, H.C.; Bertolotti-Ciarlet, A.; Nazarian, R.; Tajyar, S.; Lee, B. EphrinB2 Is the Entry Receptor for Nipah Virus, an Emergent Deadly Paramyxovirus. Nature 2005, 436, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Noguchi, A.; Marsh, G.A.; McEachern, J.A.; Okutani, A.; Hotta, K.; Bazartseren, B.; Fukushi, S.; Broder, C.C.; Yamada, A.; et al. A Neutralization Test for Specific Detection of Nipah Virus Antibodies Using Pseudotyped Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Expressing Green Fluorescent Protein. Journal of Virological Methods 2009, 160, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Kalkeri, R.; Wang, M.; Haner, B.; Dent, D.; Osman, B.; Skonieczny, P.; Ross, J.; Feng, S.-L.; Cai, R.; et al. Validation of a Pseudovirus Neutralization Assay for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2: A High-Throughput Method for the Evaluation of Vaccine Immunogenicity. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Wu, X.; Ma, J.; Cao, S.; Huang, W.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Development of in Vitro and in Vivo Rabies Virus Neutralization Assays Based on a High-Titer Pseudovirus System. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 42769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Q.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. Development and Application of a Bioluminescent Imaging Mouse Model for Chikungunya Virus Based on Pseudovirus System. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6387–6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).