Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Simulation Details

| Interaction | ε (eV) | σ (Å) |

| H-O | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| O-O | 0.00914 | 3.1668 |

| H-H | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| H-Mo | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| H-S | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| O-Mo | 0.002314 | 3.6834 |

| O-S | 0.011255 | 3.1484 |

| Interaction | Q | (Å) | A | B | β |

| Mo-Mo | 3.4191 | 179.0080 | 1.0750 | 716.9465 | 1.1610 |

| Mo-S | 1.5055 | 575.5097 | 1.1927 | 1344.4682 | 1.2697 |

| S-S | 0.2550 | 1228.4323 | 1.1078 | 1500.2125 | 1.1267 |

| state | Nanotube type |

Nanotube total atoms |

x(Å) | y(Å) | z(Å) | Water molecules |

CPU Time/hrs |

| Order-inside | (22,22) | 5643 | 141.4 | 141.4 | 48.9 | 1174 | 205 (rate 0.13) |

| Order-outside | (22,22) | 45633 | 108.6 | 109.4 | 44.4 | 14595 | 236 (rate 0.13) |

| Disorder-inside | (22,22) | 4971 | 141.4 | 141.8 | 42.6 | 1041 | 195 (rate 0.13) |

| Disorder-outside | (22,22) | 33477 | 90.5 | 94.1 | 48.9 | 10455 | 370 (rate 0.13) |

3. Results and Discussion

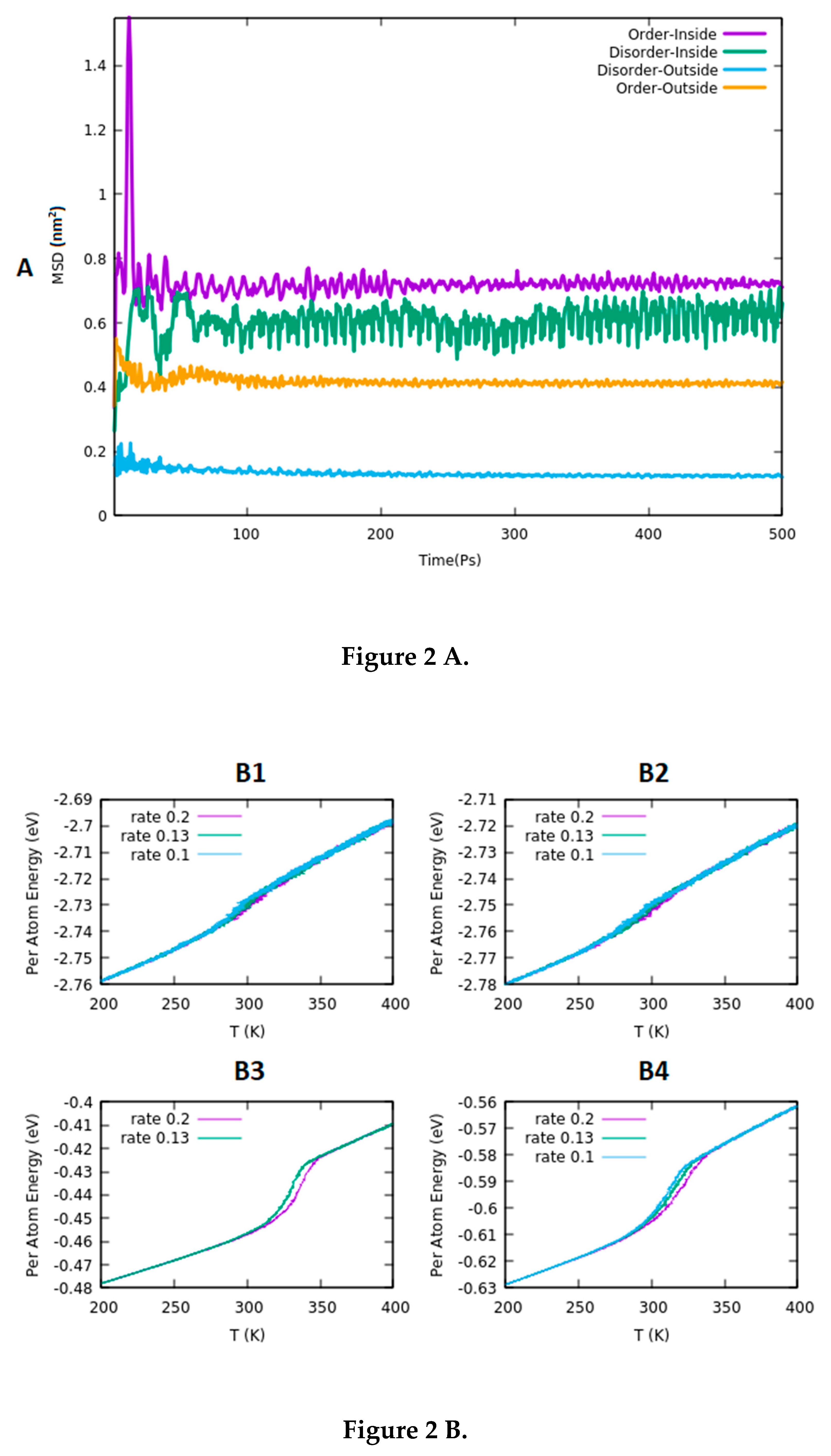

3.1. Structural Stability

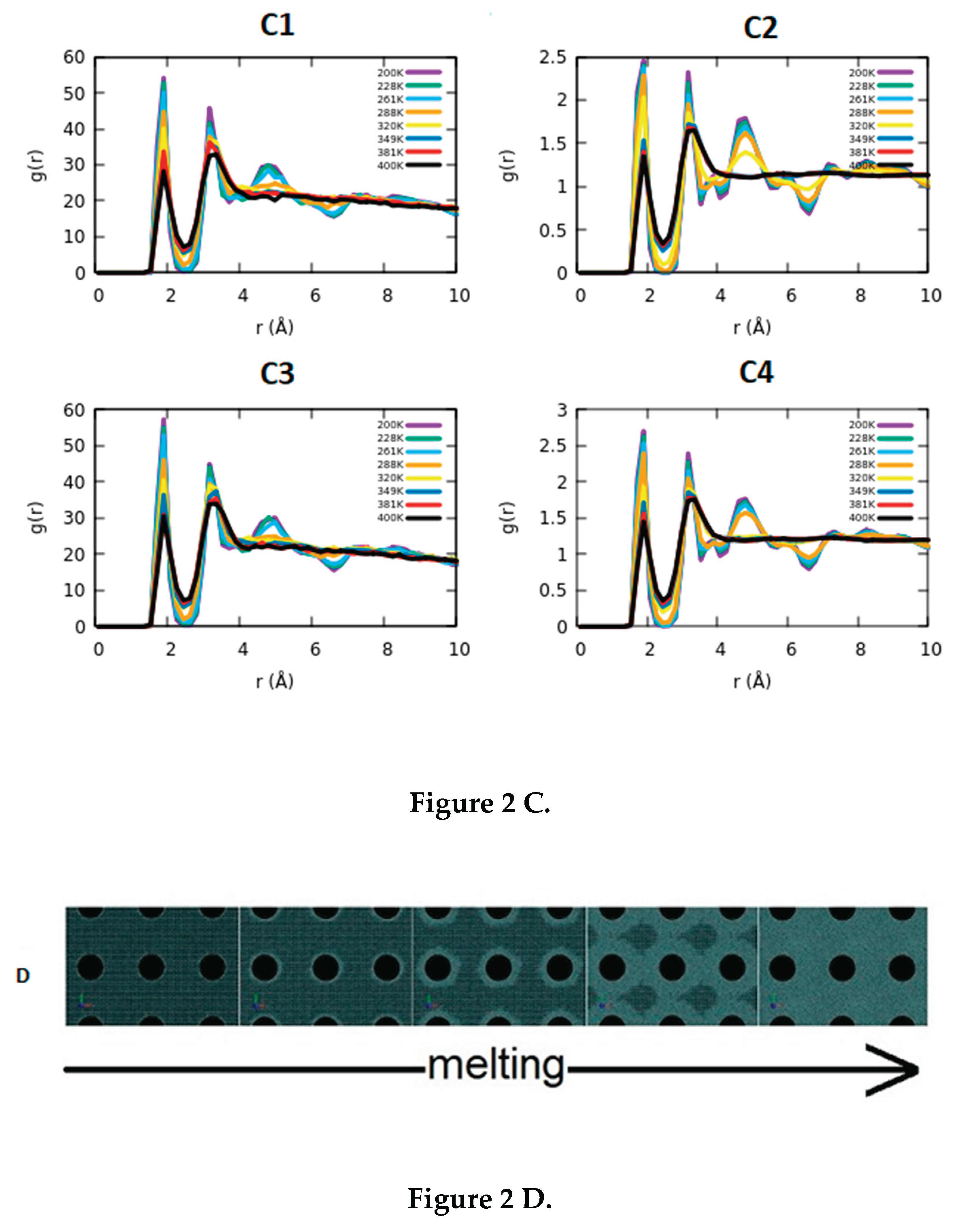

3.2. Determination of the Melting Point

3.3. Comparison of the Results

| Property | CNT | MoS2 nanotubes | CNT and Graphene | Graphene slit nanopores | CNT | CNT | CNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface type | Hydrophobic (non-polar) | Hydrophilic (Semi-polar) | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic |

| Interaction with water | Week | Moderate to strong | strong | Moderate to strong | strong | strong | strong |

| Melting point of confined water | Lower (~ -20˚C or less) | Higher (~ +10˚C or more) | Higher | - | Higher | Lower | - |

| Ice structure inside tubes | Irregular or ice nanotubes | More ordered, closer to known ice phases | ordered | amorphous | ordered | - | - |

| Water permeability | high | lower | high | lower | lower | - | high |

| Ice stability | Unstable at higher temperatures | More stable compared to CNT | Stable | Stable | Stable | - | - |

| Key References | [55] | [32] | [22] | [14] | [25] | [28] | [29] |

4. Conclusions

References

- F. Béguin, V. Pavlenko, P. Przygocki, M. Pawlyta, P. Ratajczak, Carbon 169 (2020) 501.

- K. Sotthewes, P. Bampoulis, H.J. Zandvliet, D. Lohse, B. Poelsema, ACS Nano 11 (2017) 12723.

- S. Chakraborty, H. Kumar, C. Dasgupta, P.K. Maiti, Acc. Chem. Res. 50 (2017) 2139.

- D. Han, X. Jin, Y. Li, W. He, X. Ai, Y. Yang, et al., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15 (2024) 2375.

- H.R. Corti, G.A. Appignanesi, M.C. Barbosa, J.R. Bordin, C. Calero, G. Camisasca, et al., Eur. Phys. J. E 44 (2021) 1.

- W. Wan, Z. Zhao, S. Liu, X. Hao, T.C. Hughes, J. Qiu, Nanoscale Adv. 6 (2024) 1643.

- A. Serva, N. Dubouis, A. Grimaud, M. Salanne, Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 1034.

- H. Zou, L. Yang, Z. Huang, Y. Dong, R.-Y. Dong, Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 220 (2024) 124938.

- D. Dutta, T. Muthulakshmi, P. Maheshwari, Chem. Phys. Lett. 826 (2023) 140644.

- J.N. Bassis, A. Crawford, S.B. Kachuck, D.I. Benn, C. Walker, J. Millstein, et al., Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 52 (2024).

- L. Salvati Manni, S. Assenza, M. Duss, J.J. Vallooran, F. Juranyi, S. Jurt, et al., Nat. Nanotechnol. 14 (2019) 609.

- I. Baranova, A. Angelova, W.E. Shepard, J. Andreasson, B. Angelov, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 634 (2023) 757.

- C.A. Angell, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 55 (2004) 559.

- W.-H. Zhao, L. Wang, J. Bai, L.-F. Yuan, J. Yang, X.C. Zeng, Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 2505.

- A.W. Knight, N.G. Kalugin, E. Coker, A.G. Ilgen, Sci. Rep. 9 (2019) 8246.

- M. Jażdżewska, K. Domin, M. Śliwińska-Bartkowiak, A. Beskrovnyi, D.M. Chudoba, T. Nagorna, et al., J. Mol. Liq. 283 (2019) 167.

- T. Khan, M.-x. Han, X.-w. Kong, D. Qu, J.-l. Bai, Z.-q. Wang, et al., Chem. Phys. Lett. 856 (2024) 141666.

- A. Reinhardt, M. Bethkenhagen, F. Coppari, M. Millot, S. Hamel, B. Cheng, Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 4707.

- S.L. Bore, F. Paesani, Nat. Commun. 14 (2023) 3349.

- J. Hayward, J. Reimers, J. Chem. Phys. 106 (1997) 1518.

- R. Ma, D. Cao, C. Zhu, Y. Tian, J. Peng, J. Guo, et al., Nature 577 (2020) 60.

- M. Raju, A. Van Duin, M. Ihme, Sci. Rep. 8 (2018) 3851.

- G. Wang, N. Wu, J. Wang, J. Shao, X. Zhu, X. Lu, L. Guo, RSC Adv. 6 (2016) 108343.

- S. Chiashi, Y. Saito, T. Kato, S. Konabe, S. Okada, T. Yamamoto, Y. Homma, ACS Nano 13 (2019) 1177.

- M. Matsumoto, T. Yagasaki, H. Tanaka, J. Chem. Phys. 154 (2021) 094702.

- Y.-g. Zheng, H.-f. Ye, Z.-q. Zhang, H.-w. Zhang, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14 (2012) 964.

- M. Erko, G.H. Findenegg, N. Cade, A. Michette, O. Paris, Phys. Rev. B 84 (2011) 104205.

- V.V. Chaban, V.V. Prezhdo, O.V. Prezhdo, ACS Nano 6 (2012) 2766.

- J. Wang, Y. Zhu, J. Zhou, X.-H. Lu, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6 (2004) 829.

- G. Cicero, J.C. Grossman, E. Schwegler, F. Gygi, G. Galli, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (2008) 1871.

- M.K. Tripathy, D.K. Mahawar, K. Chandrakumar, J. Chem. Sci. 132 (2020) 1.

- P. Bampoulis, V.J. Teernstra, D. Lohse, H.J. Zandvliet, B. Poelsema, J. Phys. Chem. C 120 (2016) 27079.

- A.N. Enyashin, S. Gemming, M. Bar-Sadan, R. Popovitz-Biro, S.Y. Hong, Y. Prior, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46 (2007) 623.

- A.O. Pereira, C.R. Miranda, J. Phys. Chem. C 119 (2015) 4302.

- T. Stephenson, Z. Li, B. Olsen, D. Mitlin, Energy Environ. Sci. 7 (2014) 209.

- Z. Ahadi, M. Shadman Lakmehsari, S. Kumar Singh, J. Davoodi, J. Appl. Phys. 122 (2017) 224305.

- D. Maharaj, B. Bhushan, Sci. Rep. 5 (2015) 8539.

- M. Matsumoto, T. Yagasaki, H. Tanaka, J. Comput. Chem. 39 (2018) 2454.

- M. Matsumoto, T. Yagasaki, H. Tanaka, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61 (2021) 2542.

- R.W. Hockney, J.W. Eastwood, Computer Simulation Using Particles, CRC Press, 2021.

- J.E. Jones, Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 106 (1924) 441.

- J.E. Lennard-Jones, Proc. Phys. Soc. 43 (1931) 461.

- S. Xiong, G. Cao, Nanotechnology 27 (2016) 105701.

- B. Mortazavi, T. Rabczuk, RSC Adv. 7 (2017) 11135.

- M. Maździarz, Materials 14 (2021) 519.

- J. Abascal, E. Sanz, R. García Fernández, C. Vega, J. Chem. Phys. 122 (2005) 234511.

- O.A. Karim, A. Haymet, J. Chem. Phys. 89 (1988) 6889.

- R. García Fernández, J.L. Abascal, C. Vega, J. Chem. Phys. 124 (2006) 144506.

- T. Chang, G. Zhao, Adv. Sci. 8 (2021) 2002425.

- R.P. Bebartta, R. Sehrawat, K. Gul, Advances in Biopolymers for Food Science and Technology, Elsevier, 2024, p. 445.

- J.-R. Authelin, M.A. Rodrigues, S. Tchessalov, S.K. Singh, T. McCoy, S. Wang, E. Shalaev, J. Pharm. Sci. 109 (2020) 44.

- L. Scalfi, B. Coasne, B. Rotenberg, J. Chem. Phys. 154 (2021) 114708.

- J.W. Cahn, J.E. Hilliard, J. Chem. Phys. 28 (1958) 258.

- D.V. Svintradze, Biophys. J. 122 (2023) 892.

- G. Hummer, J.C. Rasaiah, J.P. Noworyta, Nature 414 (2001) 188.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).