1. Introduction

Neurons exhibit remarkable complexity in morphology and function [

34], requiring highly specialized and dynamic gene expression programs to regulate synapse formation, neurotransmission, and plasticity while maintaining cellular homeostasis. Advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics, combined with computational tools such as machine learning (ML), have revolutionized our ability to decode neuronal gene regulation, revealing spatiotemporal expression patterns at unprecedented resolution.

Expanding multi-omics datasets have further refined our understanding of neuronal function. The Tabula Sapiens project [

31], a multi-tissue single-cell transcriptomic atlas spanning over 500,000 human cells, complements the mouse-focused Tabula Muris [

30], enabling cross-species comparisons that uncover conserved neuronal pathways and functional divergence. The Allen Brain Observatory [

32], incorporating high-resolution imaging and electrophysiological data from over 100,000 neurons, provides a direct link between gene activity and neuronal firing patterns, bridging the gap between molecular and functional neuroscience.

Epigenomic datasets have also significantly advanced the field. The Roadmap Epigenomics Projet [

27], with its spatially resolved histone modification maps, allows for in-depth exploration of epigenetic regulation in neuronal subtypes. The Human Cell Atlas [24-25], now integrating transcriptomic and epigenomic datasets, facilitates a systems-level investigation of neuronal differentiation and plasticity. Together, these resources provide a critical foundation for deciphering the intricate interplay between gene regulation, neuronal identity, and disease-associated dysregulation.

2. Integrative Statistical and Computational Approaches in Neurobiology

Statistical and computational frameworks are essential for deciphering the complex regulatory networks that govern neuronal function. By integrating biological datasets, these approaches reveal novel insights into gene expression dynamics, neuronal identity, and therapeutic opportunities. This review highlights key computational techniques and their applications in neurobiology.

3. Dimensionality Reduction and Biological Insights

High-dimensional genomic datasets, such as single-cell transcriptomics, require dimensionality reduction techniques to filter noise while preserving biologically relevant structures. These methods facilitate pattern discovery, subtype identification, and regulatory network characterization in neuronal systems.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [

9] is a widely used linear transformation technique that projects high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional space while retaining global variance. PCA has been instrumental in identifying regulatory elements in methylation datasets from the Roadmap Epigenomics Project, uncovering genomic regions linked to neuronal plasticity and synaptic remodeling.

However, non-linear relationships in gene expression often limit PCA’s effectiveness. To address this, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) [

15] constructs a topological representation of data, capturing complex gene expression patterns with higher sensitivity than PCA, though at a greater computational cost. UMAP-driven analyses of the Tabula Muris dataset have successfully clustered neuronal subtypes, refining our understanding of cell-type-specific regulatory mechanisms.

UMAP, for instance, was one of the techniques used in a study of mice traumatic brain injury. snRNA-seq was used to sequence hippocampal nuclei followed by quality checks and dimensionality and noise reduction, providing a valuable dataset for future studies on brain trauma [

36]. A similar dataset with a similar analysis, but for exercise, noticed significant crosstalk between NF-kB, Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and retinoic acid pathways after exercise in the Cornu Ammonis region [

17]

4. Feature Selection in Functional Genomics

Feature selection refines AI models by prioritizing biologically relevant variables, such as key genes and enhancers, which drive neuronal function. By reducing noise and focusing on the most informative features, this approach enhances the interpretability and accuracy of computational predictions.

A widely used technique, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [

7], iteratively removes the least important features and retrains the model, refining it to include only those variables that contribute significantly to biological outcomes. A modified version of RFE, called dynamic RFE (dRFE) was applied recently to 17 different -omics datasets for binary classification and showed significant improvements over standard RFE [

8].

It is sometimes the case that we have a model which automatically penalizes certain parameters if it deems that the feature associated with them is less relevant. LASSO regression imposes constraints on model parameters by enforcing sparsity, automatically selecting the most relevant genes for analysis. This technique along with particle swarm optimization has shown a 96% accuracy in early Alzheimer’s diagnosis vs healthy controls [

5].

Note also, for example, a modified version of LASSO regression is at the heart of the widely used DRIAD (Drug Repurposing in AD) ML framework [

23]. These findings offer potential targets for early therapeutic intervention, illustrating how AI-driven feature selection can pinpoint molecular signatures with translational relevance.

5. Temporal Analysis of Neuronal Regulation

Temporal analyses of gene expression and chromatin states provide crucial insights into neurodevelopment, synaptic plasticity, and disease progression. In schizophrenia, for instance, stage-specific disruptions in synaptic signaling have been linked to symptom severity and treatment response [

19].

A classical approach, Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA), models gene expression time-series data by integrating autoregression, stationarity adjustments, and moving averages. ARIMA has been applied to predict schizophrenia symptom severity and outpatient remission rates [

26]. However, its linear assumptions limit its ability to capture complex, nonlinear genomic patterns.

Integrating these temporal models with multi-omics data and explainable AI frameworks could enhance disease tracking and precision medicine strategies. Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) [

18] is a time-series technique that aligns sequences non-linearly to account for variations in speed and timing. In neuropsychiatric research, DTW has been used to map symptom trajectories in bipolar disorder [

16] and depression [

2], capturing individualized disease progression. Applied to transcriptomic datasets, DTW has revealed conserved gene expression pathways across datasets like PPMI, highlighting shared regulatory mechanisms in neurodegeneration. These analyses emphasize the temporal complexity of neuronal regulation, offering insights into disease staging and personalized interventions in precision medicine

6. Network Analysis for Gene Regulation

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) exhibit a natural graph-like structure, where genes function as nodes and regulatory interactions define weighted edges. Graph neural networks (GNNs) [

12], an extension of standard neural networks, have emerged as powerful tools for modeling GRNs, capturing complex dependencies between genes, proteins, and non-coding elements. Unlike traditional correlation-based approaches, GNNs leverage hierarchical relationships and contextual dependencies, allowing for deeper insights into transcriptional regulation. Recent applications have used GNNs have been used to illustrate disease-related neural development and differential mechanisms [

33] to infer causal regulatory pathways [

11], and to inferring novel GRNs [

6].

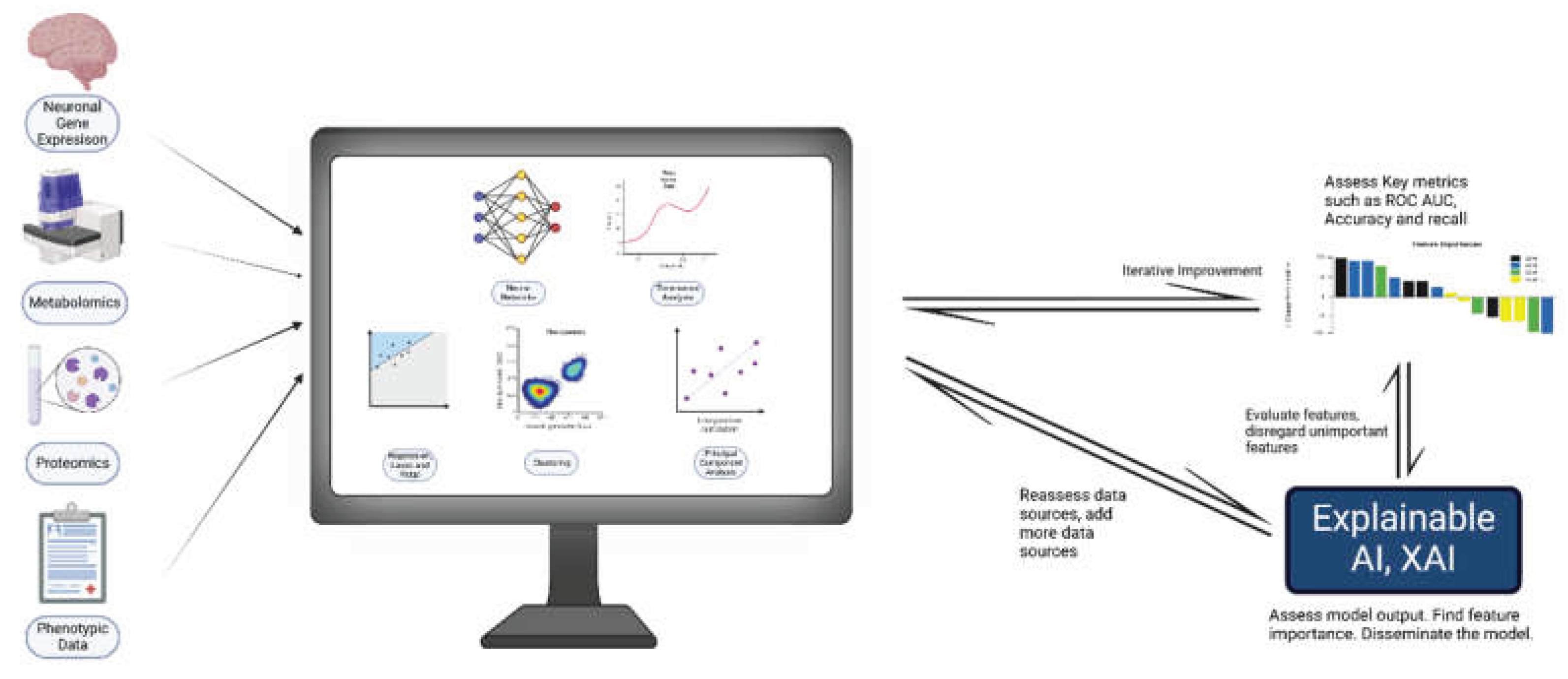

Figure 2.

Illustration of ML-driven analysis of brain -omics and phenotypic data with iterative model refinement and explainable AI (XAI). Created with BioRender. Goswami, A. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/xapiapw.

Figure 2.

Illustration of ML-driven analysis of brain -omics and phenotypic data with iterative model refinement and explainable AI (XAI). Created with BioRender. Goswami, A. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/xapiapw.

7. Hidden Markov Models

Beyond machine learning, Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) provide powerful frameworks for neurogenomics. Markov models, which predict future states based on current conditions, have been used to decode gene expressions in epilepsy [

21], analyze temporal brain activity in bipolar disorder [

37], and track emotional regulation in schizophrenia, [

28].

8. Explainable AI for Model Interpretability

Explainable AI (XAI) is a set of tools to understand the set of contingent factors leading to a model’s prediction. For our purposes, these tools address the "black box" nature of deep learning by identifying biologically meaningful features driving predictions. Techniques like SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) [

3,

14], a game theoretic approach to model predictions has seen promising use in identifying candidate autism genes and in transcriptomic analysis.

9. Case Studies Demonstrating Biological Applications

Huntington’s Disease: Predictive Stratification A machine learning pipeline for the Enroll-HD cohort integrated gradient-boosted decision trees (XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) to predict age of onset (AAO) and saw effectiveness against the well-known Langbehn formula [

20].

Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Biomarker Discovery: Support vector machines have been successfully used as an explainable AI tool in accurately diagnosing and predicting Alzheimer’s with outcomes comparable to traditional methods in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center dataset [

1].

Schizophrenia: Biomarkers from f-MRI imaging: Graph neural networks (GNNs) have been effectively applied to resting-state f-MRI data, achieving an accuracy of 0.82 in distinguishing individuals with schizophrenia from healthy controls, outperforming or matching most existing methods [

33].

10. Limitations

Despite significant advancements, three key challenges persist in the field.

Multi-Omics Data Integration: Harmonizing multi-omics datasets is complicated by batch effects [

35], differences in resolution, and data sparsity [

10], which hinder cross-study reproducibility. While the emergence of large, standardized datasets has mitigated these challenges, further improvements in data harmonization and preprocessing pipelines remain crucial.

Lack of Experimental Validation & Model Interpretability: Many deep learning-based predictions lack experimental validation, limiting their translational impact. Additionally, their black-box nature poses challenges for clinical adoption, as regulatory approval and clinical trust require interpretability. Advances in explainable AI (XAI), such as SHAP and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) [

22], are improving model transparency but require broader implementation.

Dataset Bias & Generalizability: Existing datasets often underrepresent diverse populations, introducing biases that limit the generalizability of findings [

13]. Addressing this issue requires greater diversity in sample collection, an effort increasingly supported by large-scale consortia collaborations.

11. Conclusion

The integration of multi-omics data, computational modeling, and AI has revolutionized our understanding of neuronal gene regulation, plasticity, and disease. Advances in single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, alongside epigenomic profiling, have revealed neuronal identity and function, while AI-driven approaches have identified key regulatory elements, biomarkers, and therapeutic targets.

However, challenges in data integration, validation, and model interpretability hinder clinical translation. Standardized multi-omics pipelines, explainable AI (XAI), and diverse datasets are needed for generalizability.

Future directions include hybrid AI models, high-resolution neuronal atlases, and deeper computational integration into precision medicine. Interdisciplinary collaboration will be key to advancing AI-driven diagnostics and therapies for brain disorders.

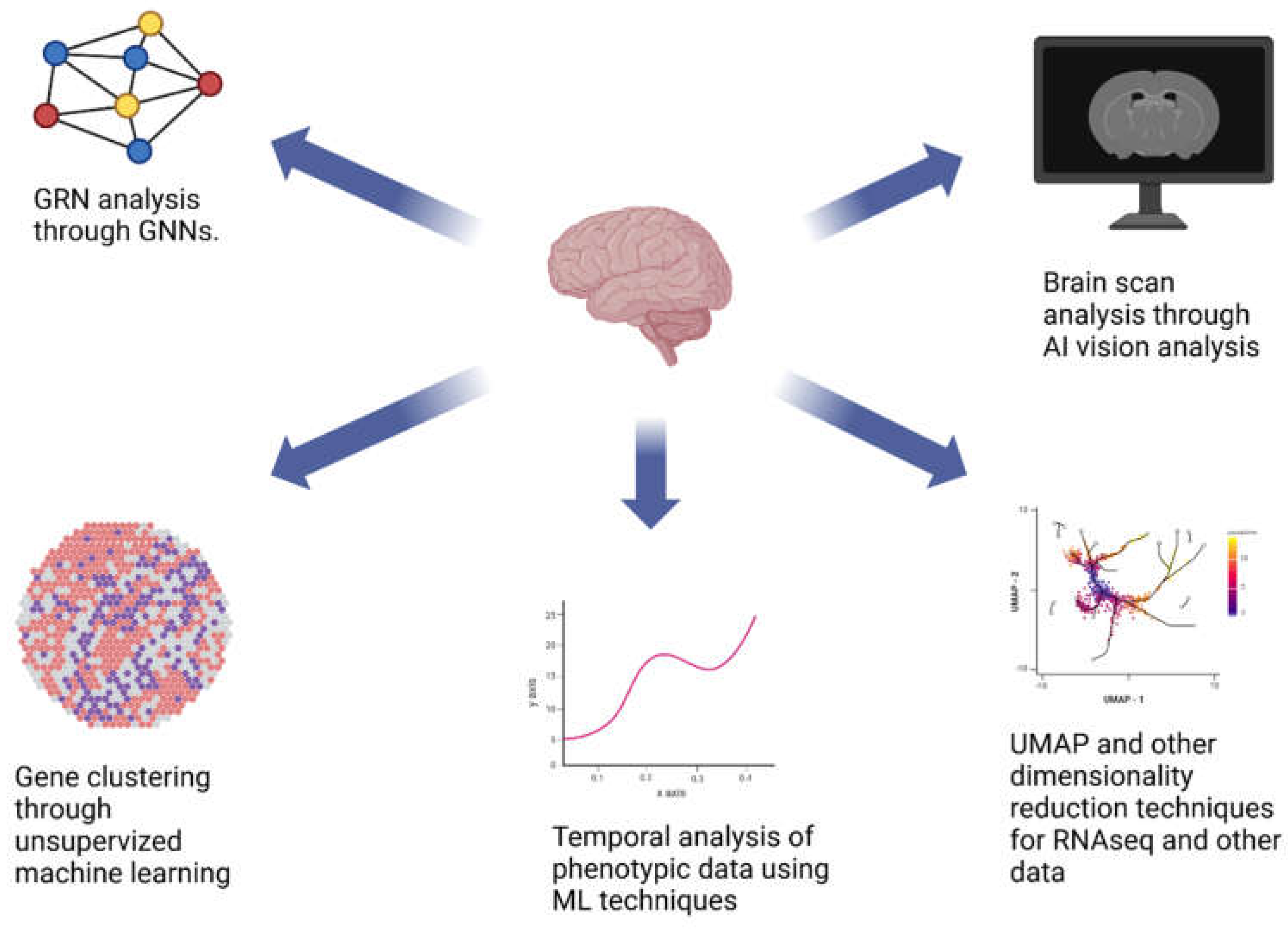

Figure 3.

An illustration of the various ML techniques available for analyzing brain -omics data. Created in BioRender. Goswami, a. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/xapiapw.

Figure 3.

An illustration of the various ML techniques available for analyzing brain -omics data. Created in BioRender. Goswami, a. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/xapiapw.

| Datasets |

| Dataset Name |

Data Type |

Purpose |

Scale and Resolution |

Key Application |

| Allen Brain Atlas (Vries, Siegle, & Koch, 2023) |

Imaging, transcriptomics |

Mapping neuronal activity |

More than 100,000 neurons, cellular resolution |

Understanding cortical structure functions |

| Tabula Muris ( (The Tabula Muris Consortium, 2020)) |

Single-cell RNA-seq |

Clustering neuronal subtypes |

Approx. 100,000 cells, single-cell resolution |

Exploring immune-neuronal interactions |

| Human Cell Atlas (Rood, et al., 2025) (Rozenblatt-Rosen, Stubbington, Regev, & Teichmann, 2017) |

Multi-omics |

Integrating transcriptomics & epigenomics |

More than ten million cells, single cell & spatial resolution |

Tracking developmental trajectories |

| Roadmap Epigenomics (Satterlee, et al., 2019) |

Epigenomics |

Studying histone modifications |

Genome-wide, high-resolution |

Identifying histone plasticity markers |

| Computational Techniques |

| Methodology |

Function |

Example Use Case |

Dataset Used |

Strength |

| LASSO Regression |

Feature selection with sparsity |

Identifying early Alzheimer’s biomarkers |

Alzheimer’s Disease National Initiative |

Select the most relevant gene markers (Cui, et al., 2021) |

| Graph Neural Networks |

Modeling gene regulatory networks |

Infer regulatory pathways |

Dream5 network initiative dataset |

Captures complex interactions (Feng, Jiang, Yin, & Sun, 2023) |

| SHAP |

Identifying key biological features |

Understanding transcriptional mechanisms in ASD |

Various |

Improves AI model interpretability (Castro-Martinez, Vargas, Diaz-Beltran, & Esteban, 2024) |

| Challenges in Multi-omics Analysis |

| Challenge |

Issue |

Suggested Approach |

Impact on Research |

| Batch Effects |

Bias in multi-omics integration |

Standardizing data pipelines |

Improves reproducibility |

| Data Sparsity |

Incomplete feature representation |

Robust imputation methods |

Enables deduction of rare neuronal subtypes |

| Deep learning models |

Lack of interpretability in AI models |

Implementation of explainable AI frameworks |

Enhances AI-driven biomarker validation. |

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Arkansas High Performance Computing Center which is funded through multiple National Science Foundation grants and the Arkansas Economic Development Commission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Alatrany, A. S., Khan, W., Hussain, A., Kolivand, H., & Al-Jumeily, D. (2024). An explainable machine learning approach for Alzheimer’s disease classification. 14(4637). [CrossRef]

- Booij, M. M., van Noorden, M. S., van Vliet, I. M., Ottenheim, N. R., van der Wee, N. J., van Hemert, A. M., & Giltay, E. J. (2021). Dynamic time warp analysis of individual symptom trajectories in depressed patients treated with electroconvulsive therapy. Journal of Affective Disorder, 293, 435-443. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Martinez, J., Vargas, E., Diaz-Beltran, L., & Esteban, F. J. (2024). Enhancing Transcriptomic Insights into Neurological Disorders Through the Comparative Analysis of Shapley Values. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol., 46(12). [CrossRef]

- Citri, A., & Malenka, R. C. (2008). Synaptic Plasticity: Multiple Forms, Functions, and Mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology, 18-41.

- Cui, X., Xiao, R., Liu, X., Ziao, H., Zheng, X., Zhang, Y., & Du, J. (2021). Adaptive LASSO logistic regression based on particle swarm optimization for Alzheimer's disease early diagnosis. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems(104316). [CrossRef]

- Feng, K., Jiang, H., Yin, C., & Sun, H. (2023). Gene regulatory network inference based on causal discovery integrating with graph neural network. Quantitative Biology. [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I., Weston, J., Barnhill, S., & Vapnik, V. (2002). Gene Selection for Cancer Classification using Support Vector Machines. Machine Learning, 46, 389-422. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y., Huan, L., & Zhou, F. (2021). A dynamic recursive feature elimination framework (dRFE) to further refine a set of OMIC biomarkers. Bioinformatics, 37(15), 2183-2189. [CrossRef]

- James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2013). An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R (Springer Texts in Statistics). Springer.

- Jeong, Y., Ronen, J., Kopp, W., Lutsik, P., & Akalin, A. (2024). scMaui: a widely applicable deep learning framework for single-cell multiomics integration in the presence of batch effects and missing data. BMC Bioinformatics, 25(275). [CrossRef]

- Ji, R., Geng, Y., & Quan, X. (2024). Inferring gene regulatory networks with graph convolutional network based on causal feature reconstruction. Scientific Reports, 14(21342). [CrossRef]

- Khemani, B., Patil, S., Kotecha, K., & Tanwar, S. (2024). A review of graph neural networks: concepts, architectures, techniques, challenges, datasets, applications, and future directions. Journal of Big Data, 11(18). [CrossRef]

- Landry, L. G., Ali, N., Williams, D. R., Rehm, H. L., & Bonham, V. L. (2017). Lack Of Diversity In Genomic Databases Is A Barrier To Translating Precision Medicine Research Into Practice. Health Affairs. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S.-I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. NIPS'17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 4468-4777). Red Hook, NY: Curran Associates, Inc.

- McInnes, L., Healy, J., Saul, N., & Grossberger, L. (2018). UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(29). [CrossRef]

- Mesbah, R., Koenders, M. A., Spiijker, A. T., de Leeuw, M., van Hemert, A. M., & Giltray, E. J. (2023). Dynamic time warp analysis of individual symptom trajectories in individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. [CrossRef]

- Methi, A., Islam, M., Kaurani, L., Sakib, M. S., Kruger, D. M., Pena, T., . . . Fischer, A. (2024). A Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of the Mouse Hippocampus After Voluntary Exercise. Mol. Neurobiol., 61(8), 5628-5645. [CrossRef]

- Muller, M. (2007). Information Retrieval for Music and Motio. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Obi-Nagata, K., Temma, Y., & Hayashi-Takagi, A. (2019). Synaptic functions and their disruption in schizophrenia: From clinical evidence to synaptic optogenetics in an animal model. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B Physical and Biological Sciences, (pp. 179-197). [CrossRef]

- Ouwerkerk, J., Feleus, S., van der Zwaan, K. F., Li, Y., Roos, M., van Roon-Mom, W. M., . . . Mina, E. (2023). Machine learning in Huntington’s disease: exploring the Enroll-HD dataset for prognosis and driving capability prediction. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 18(218). [CrossRef]

- Qin, L., Zhou, Q., Sun, Y., Pang, X., Chen, Z., & Zheng, J. (2024). Dynamic functional connectivity and gene expression correlates in temporal lobe epilepsy: insights from hidden markov models. Journal of Translational Medicine, 22(736). [CrossRef]

- Ribiero, M. T., Singh, S., & Guestrin, C. (2016). "Why Should I Trust You?": Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. KDD '16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. Association for Computing MachineryNew YorkNYUnited States. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S., Hug, C., Todorov, P., Moret, N., Boswell, S. A., Evans, K., . . . Sokolov, A. (2021). Machine learning identifies candidates for drug repurposing in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Communications, 12(1033). [CrossRef]

- Rood, J. E., Wynne, S., Robson, L., Hupalowska, A., Randell, J., Teichmann, S. A., & Regev, A. (2025). The Human Cell Atlas from a cell census to a unified foundation model. Nature, 637, 1065-1071. [CrossRef]

- Rozenblatt-Rosen, O., Stubbington, M. J., Regev, A., & Teichmann, S. A. (2017). The Human Cell Atlas: from vision to reality. Nature, 550, 451-453. [CrossRef]

- Sabhawal, A., Grover, G., Kaushik, S., & Unni, S. K. (2019). Modelling and forecasting Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores to achieve remission using time series analysis. International Journal Of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 28(1). [CrossRef]

- Satterlee, J. S., Chadwich, L. H., Tysin, F. S., McAllister, K., Beaver, J., Birnbaum, L., . . . Roy, A. L. (2019). The NIH Common Fund/Roadmap Epigenomics Program: Successes of a comprehensive consortium. Science, 5(7). [CrossRef]

- Strauss, G. P., Esfahlani, F. Z., Raugh, I. M., Luther, L., & Sayama, H. (2023). Markov chain analysis indicates that positive and negative emotions have abnormal temporal interactions during daily life in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. [CrossRef]

- Sunil, G., Gowtham, S., Bose, A., Harish, S., & Srinivasa, G. (2024). Graph neural network and machine learning analysis of functional neuroimaging for understanding schizophrenia. 25(2). [CrossRef]

- The Tabula Muris Consortium. (2020). A single-cell transcriptomic atlas characterizes ageing tissues in the mouse. Nature, 583, 590-595. [CrossRef]

- The Tabula Sapiens Consortium. (2022). The Tabula Sapiens: A multiple-organ, single-cell transcriptomic atlas of humans. Science, 376(eabl4896). [CrossRef]

- Vries, S. E., Siegle, J. H., & Koch, C. (2023). Sharing neurophysiology data from the Allen Brain Observatory. eLife, 12(e85550). [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Ma, A., Chang, Y., Gong, J., Jiang, Y., Qi, R., . . . Xu, D. (2021). scGNN is a novel graph neural network framework for single-cell RNA-Seq analyses. Nature Communications, 12(1882). [CrossRef]

- Yimin, F., Li, Y., Zhong, Y., Hong, L., Li, L., & Li, Y. (2024). Learning meaningful representation of single-neuron morphology via large-scale pre-training. Bioinformatics, 40(2), ii128-ii136. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Zhang, N., Mai, Y., Ren, L., Chen, Q., Cao, Z., . . . Zheng, Y. (2023). Correcting batch effects in large-scale multiomics studies using a reference-material-based ratio method. Genome Biology, 24. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Yang, Q., Yuan, R., Li, M., Lv, M., Zhang, L., . . . Chen, X. (2023). Single-nucleus transcriptomic mapping of blast-induced traumatic brain injury in mice hippocampus. Scientific Data, 10(638). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Yang, L., Lu, J., Yuan, Y., Li, D., Zhang, H., . . . Wang, B. (2024). Reconfiguration of brain network dynamics in bipolar disorder: a hidden Markov model approach. Translational Psychiatry, 14(507). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).