Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Material and Methods

Statistical Analysis:

Results

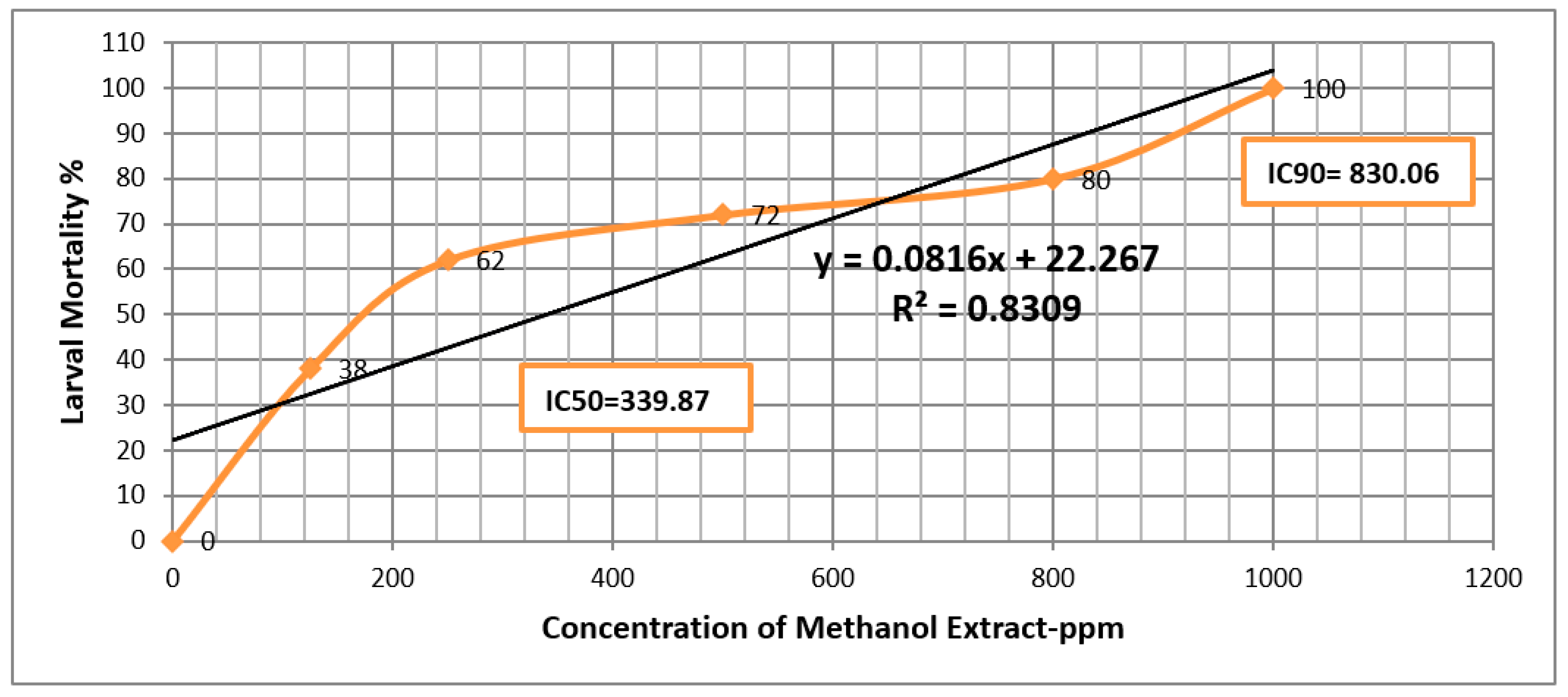

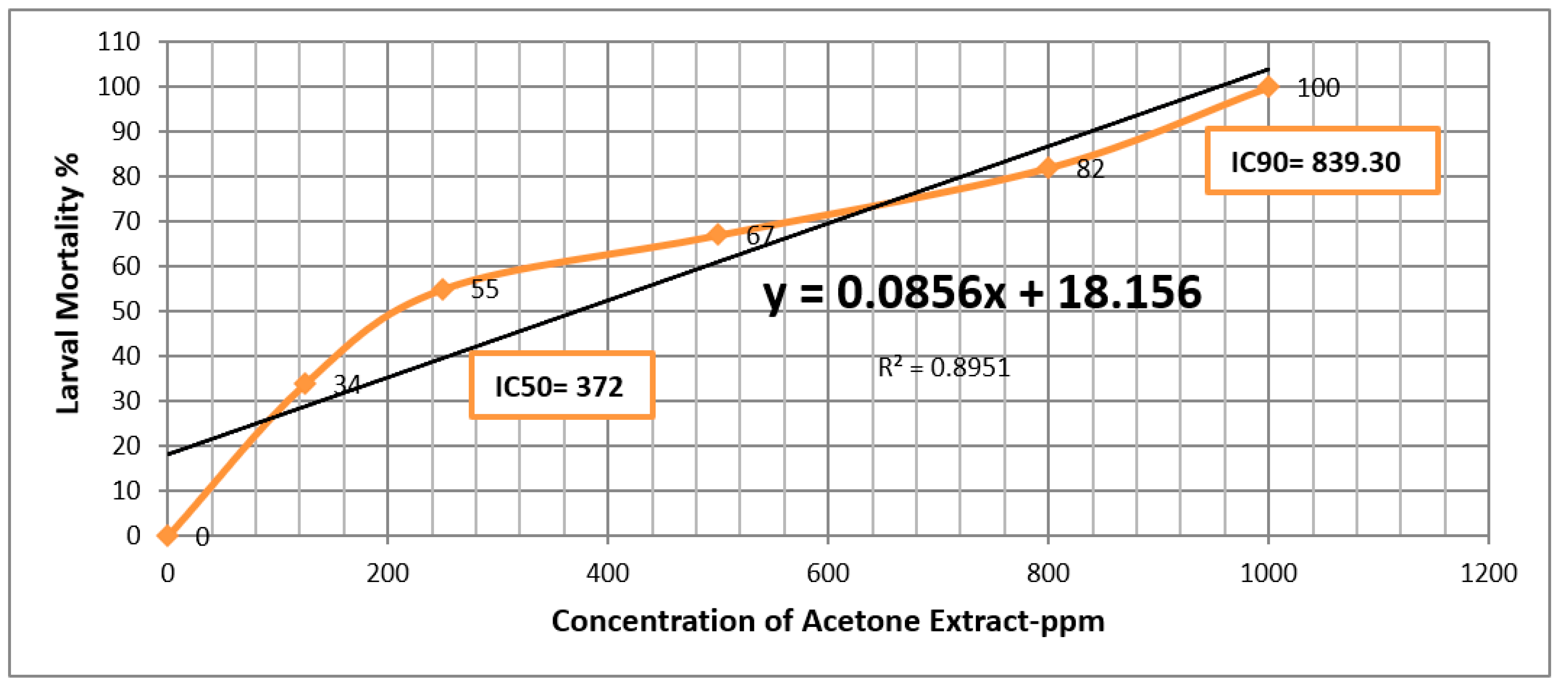

| Extract | LC50 | LC90 |

| Methanol | 339.87 (ppm) | 830.06 (ppm) |

| Acetone | 372 (ppm) | 839.30 (ppm) |

Discussion

Conclusion

Competing Of Interest

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (). What is Dengue? 2023. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/index.html Access on March 29, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rodenhuis-Zybert IA, Wilschut J, Smit JM. Dengue virus life cycle: viral and host factors modulating infectivity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(16):2773-86. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Dengue and Severe Dengue; 2023. Available: https://www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-andsevere-dengue Accessed on March 29, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. (April 2013). "The global distribution and burden of dengue" (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC36 51993) . Nature. 496 (7446): 504–507. Bibcode:2013Natur.496..504B (https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2013Natur.496..504B) . doi:10.1038/nature12060 (https://doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature12060) . PMC 3651993 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3651993) . PMID 23563266 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23563266).

- Jing Q, Wang M (June 2019). "Dengue epidemiology" (https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.glohj.2019.06.002) . Global Health Journal. 3 (2): 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.glohj.2019.06.002 (https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.glohj.2019.06.002) . ISSN 2414-6447 (https://search.worldcat.org/issn/2414- 6447).

- Pan American Health Organization. PLISA Health Information Platform for the Americas, Dengue Indicators Portal. Washington, D.C.: PAHO/WHO; 2025 [cited 28 January 2025]. Available from: https://www3.paho.org/data/index.php/en/dengue.html.

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A. , Memish, Z.A., 2018. Dengue hemorrhagic fever virus in Saudi Arabia: a review. Vector-Borne and Zoonot. Dis. 18 (2), 75–81.

- Zaki, A. , Perera, D., Jahan, S.S., Cardosa, M.J., 2008b. Phylogeny of dengue viruses circulating in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: 1994 to 2006. Trop. Med. Int. Health 13 (4), 584–592.

- "Dengue and severe dengue" (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengueandseveredengue) . World Health Organization. 17 March 2023. Archived (https://web.archive.or g/web/20240314173620/https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue) from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- Kularatne SA (September 2015). "Dengue fever". BMJ. 351: h4661. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4661 (htt ps://doi.org/10.1136%2Fbmj.h4661) . PMID 26374064 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26374064) . S2CID 1680504 (https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:1680504).

- Emerald, M. (2024). Medicinal Plants: Therapeutic Potential, Safety, and Toxicity. In: Hock,F.J., Pugsley, M.K. (eds) Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Safety and Pharmacokinetic Assays.Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-E.; Jayakody, J.T.M.; Kim, J.-I.; Jeong, J.-W.; Choi, K.-M.; Kim, T.-S.; Seo, C.; Azimi, I.; Hyun, J.; Ryu, B. The Influence of Solvent Choice on the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Asteraceae: A Comparative Review. Foods 2024, 13, 3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, H.M.; Kashegari, A.T.; Shalabi, A.A.; Darwish, K.M.; El-Halawany, A.M.; Algandaby, M.M.; Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Abdel-Naim, A.B.; Koshak, A.E.; et al. Phenolics from Chrozophora oblongifolia Aerial Parts as Inhibitors of α-Glucosidases and Advanced Glycation End Products: In-Vitro Assessment, Molecular Docking and Dynamics Studies. Biology 2022, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu X, Kitaoka N, Rodr´ıguez-Lo ´ pez CE and Chen S (2024) Editorial: Plant secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 15:1477551. [CrossRef]

- Croft BA, Brown AWA. 1975. Responsesof arthropod natural enemiesto insecticides.Ann Rev Entomol 20: 285-335.

- Brown AWA. 1986.Insecticide resistance in mosquitoes: pragmatic review. "/ Am Mosq Control Assoc 2:123- 140.

- Hayes JB Jt Laws ER, Jr. 1991. Handbook of pesticide toxicology Volume l. San Diego' CA: Academic Press'.

- Jang, Y.S. , Baek, B.R., Yang, Y.C., Kim, M.K., Lee, H.S., 2002. Larvicidal activity of leguminous seeds and grains against Ae. aegypti and C. pipiens pallens. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 18 (3), 210–213.

- Cavalcanti, E.S. , Morais, S.M., Lima, M.A., Santana, E.W., 2004. Larvicidal activity of essential oils from Brazilian plants against Ae. aegypti L. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 99 (5), 541– 544.

- Maurya, P. , Sharma, p., Mohan, L., Batabyal, L., Srivastava, C.N., 2009. Evaluation of the toxicity of different phytoextracts ofOcimum basilicum againstAnopheles stephensi and Culex quinquefasciatus. J. Asia-Pacific Entomol. 12, 113–115.

- Kovendan, K. , Murugan, K., Vincent, S., Barnard, D.R., 2012. Mosquito larvicidal properties of Orthosiphon thymiflorus (Roth) Sleesen. (Family: Labiatae) against mosquito vectors, Anopheles stephensi, Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae).. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 5 (4), 299–305.

- Gupta, R. K. , Dutta, B. (1967): Vernacular names of the useful plants of northwest Indianarid regions. – J Agric Trop Bot Appl 14: 402-53.

- Jaradat, N. , Khasati, A., Abu-Shanab, B. A., Al-Lahham, S., Naser Zaid, A., Abualhasan, M. N., Qneibi, M., Hawash, M. (2019): Bactericidal, Fungicidal, Helminthicidal, Antioxidant, and Chemical Properties of Chrozophora obliqua Extract. – Phytothérapie 18(5): 275-283.

- Muimba-Kankolongo, A.; Ng’andwe, P.; Mwitwa, J.; Banda, M.K. , NonWood Forest Products, Markets, and Trade, in Forest Policy, Economics, and Markets in Zambia2015, Elsevier. p. 67-104.

- Täckholm, V. (1974) Students’ Flora of Egypt. 2nd Edition, Cairo University Publishing, Beirut, 888.

- Boulos, L. Flora of Egypt. Checklist; Al Hadara Publishing: Cairo, Egypt, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K. A. , Green, D. W., Pascoe, D., & Gower, D. E. (1986). The acute toxicity of cadmium to different larval stages of Chironomus riparius (Diptera: Chironomidae) and its ecological significance for pollution regulation. Oecologia 70, 362-366.

- Briggs, J. D. (1960). Reduction of adult house-fly emergence by the effects of Bacillus spp. on the development of immature forms. J. Insect pathology. 2 : 418 – 432.

- Finney, D.J. , 1971. Probit analysis, Third ed. Cambridge University Press.

- Mohan B, Nayak JB, Kumar RS, Kumari LS, Ch M, Rajani B. Phytochemical screening, GC-MS analysis of Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn. An endangered medicinal plant. J Pharmaco Phytochem. 2016;5:10-6.

- Kamaruding NA, Ismail N, Sokry N. Identification of Antibacterial Activity with Bioactive Compounds from Selected Marine Sponges. Pharmacogn J. 2020;12(3):493-502.

- Handayani, Virsa. "Insilico screening chemical compounds α-glucosidase inhibitor from Cordia myxa L." International Journal of Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences 10, no. 3 (2019): 2051-2054.

- Shaaban, Mohamed T., Mohamed F. Ghaly, and Sara M. Fahmi. "Antibacterial activities of hexadecanoic acid methyl ester and green-synthesized silver nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacteria." Journal of basic microbiology 61, no. 6 (2021): 557-568.

- Javed, M.R.; Salman, M.; Tariq, A.; Tawab, A.; Zahoor, M.K.; Naheed, S.; Shahid, M.; Ijaz, A.; Ali, H. The Antibacterial and Larvicidal Potential of Bis-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Molecules 2022, 27, 7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, Noha M., Abdel-Hamied M. Rasmey, Akram A. Aboseidah, Mahmoud Abdel Aziz, and Abdelsamed I. Elshamy. "Chemical Profile, Antimicrobial and Antitumor Activities of the Streptomyces rochei SUN35 Strain." Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 66, no. 13 (2023): 2211-2218.

- Abu-Serag, N. A., N. I. Al-Garaawi, A. M. Ali, and M. A. Alsirrag. "Analysis of bioactive phytochemical compound of (Cyperus aucheri Jaub.) by using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry." In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, vol. 388, no. 1, p. 012063. IOP Publishing, 2019.

- Al-Gara, awi, Neepal Imtair, Nidaa Adnan Abu-Serag, Khansaa Abdul Alee Shaheed, and Zina Khalil Al Bahadly. "Analysis of bioactive phytochemical compound of (Cyperus alternifolius L.) by using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry." In IOP conference series: Materials science and engineering, vol. 571, p. 012047. IOP Publishing, 2019.

- Vasumathi, Dinakaran, Swaminathan Senguttuvan, Jeganathan Pandiyan, Kuppusamy Elumalai, Marimuthu Govindarajan, Karuvi Sivalingam Subasri, and Kaliyamoorthy Krishnappa. "Bioactive molecules derived from Scoparia dulcis medicinal flora: Act as a powerful bio-weapon against agronomic pests and eco-friendlier tool on non-target species." South African Journal of Botany 162 (2023): 211-219.

- HasanMaziz, V. V. S. S. , Nanthiney Devi Ragavan, Charles Arvind, Sethuraman Vairavan, and Chengebroyen Neevashini. "Gc-Ms Analysis And Antibacterial Activity Of Dryopteris Hirtipes (Blumze) Kuntze Linn." Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences 10, no. 1S (2023): 3718-3726.

- Miyazawa, Mitsuo, Eri Horiuchi, and Jyunichi Kawata. "Components of the essential oil from Adenophora triphylla var. japonica." Journal of Essential Oil Research 20, no. 2 (2008): 125-127.

- Zhao, Q.; De Laender, F.; Van den Brink, P.J. Community composition modifies direct and indirect effects of pesticides in freshwater food webs. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Ullah, M.I.; Sajjad, A.; Shakeel, Q.; Hussain, A. Environmental and health effects of pesticide residues. In Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 311–336. [Google Scholar]

- Uwaifo, F.; John-Ohimai, F. Dangers of organophosphate pesticide exposure to human health. Matrix Sci. Med. 2020, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, M.A.M. The repellent activity test of rosemary leaf (Rosmarinus officinalis L) essential oil gel preparations influence on Aedes aegypti mosquito. In Proceedings of Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; p. 012016. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.; Crystal, K.; Coats, J. Three molecules found in rosemary or nutmeg essential oils repel ticks (Dermacentor variabilis) more effectively than DEET in a no-human assay. Pest. Manage. Sci. 2020, 77, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roark, R.C. (1947) Some Promising Insecticidal Plants. Economic Botany, 1, 437-445. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed MA. 2014. The investigate the quality Aspect from C. brocchiana seeds, and study their nutritional value, Food Science & Technology Department, College of Agricultural Studies, Sudan University of Science and Technology, Khartoum North, Sudan.

- Galal M, Adam SE. 1988. Experimental Chrozophora plicate poisoning in goats and sheep. Vet Hum Toxicol 30: 447-452.

- El-Ghonemy, A.A. (1993). Encyclopedia of medicinal plants of the United Arab Emirates. (1sted.). Abu Dhabi, UAE: United Arab Emirates University.

- Batanouny, K. (1999). Wild medicinal plants in Egypt. Cairo, Gaza, Egypt: Dept. of Botany,University of Cairo.

- Kamel MR, Nafady AM, Hassanein AM, Haggag EG. 2018. Chrozophora oblongifolia aerial parts: assessment of antioxidant activity, hepatoprotective activity and effect on hypothalamicgonadal axis in adult male rats. J Adv Pharmacy Res 2 (1): 56-62.

- Spigno, G.; Tramelli, L.; De Faveri, D.M. Effects of extraction time, temperature and solvent on concentration and antioxidant activity of grape marc phenolics. J. Food Eng. 2007, 81, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, C.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, A.; Palma, M.; Barroso, C.G. Ultrasound assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from grapes. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 732, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infectious Diseases Society of America. Statement of the IDSA concerning ‘Bioshield II: Responding to an ever-changing threat’. Alexandria, VA: IDSA; 2004.

- Pereira, V.; Figueira, O.; Castilho, P.C. Flavonoids as Insecticides in Crop Protection—A Review of Current Research and Future Prospects. Plants 2024, 13, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adel-sattar, Essam, 2001.Flavonoids from Chrozophora oblongifolia. Bull. Fac. Pharm. Cairo University.

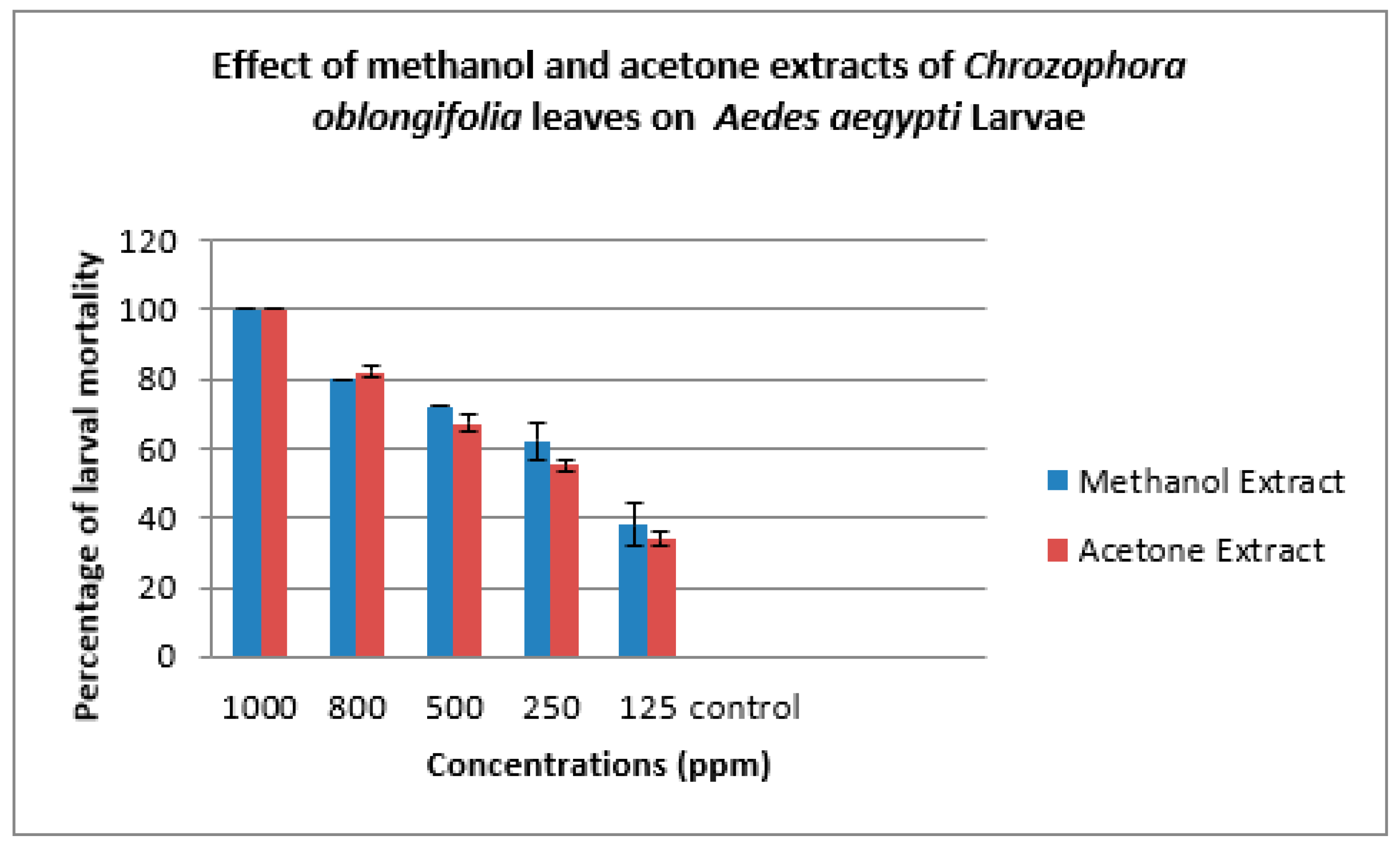

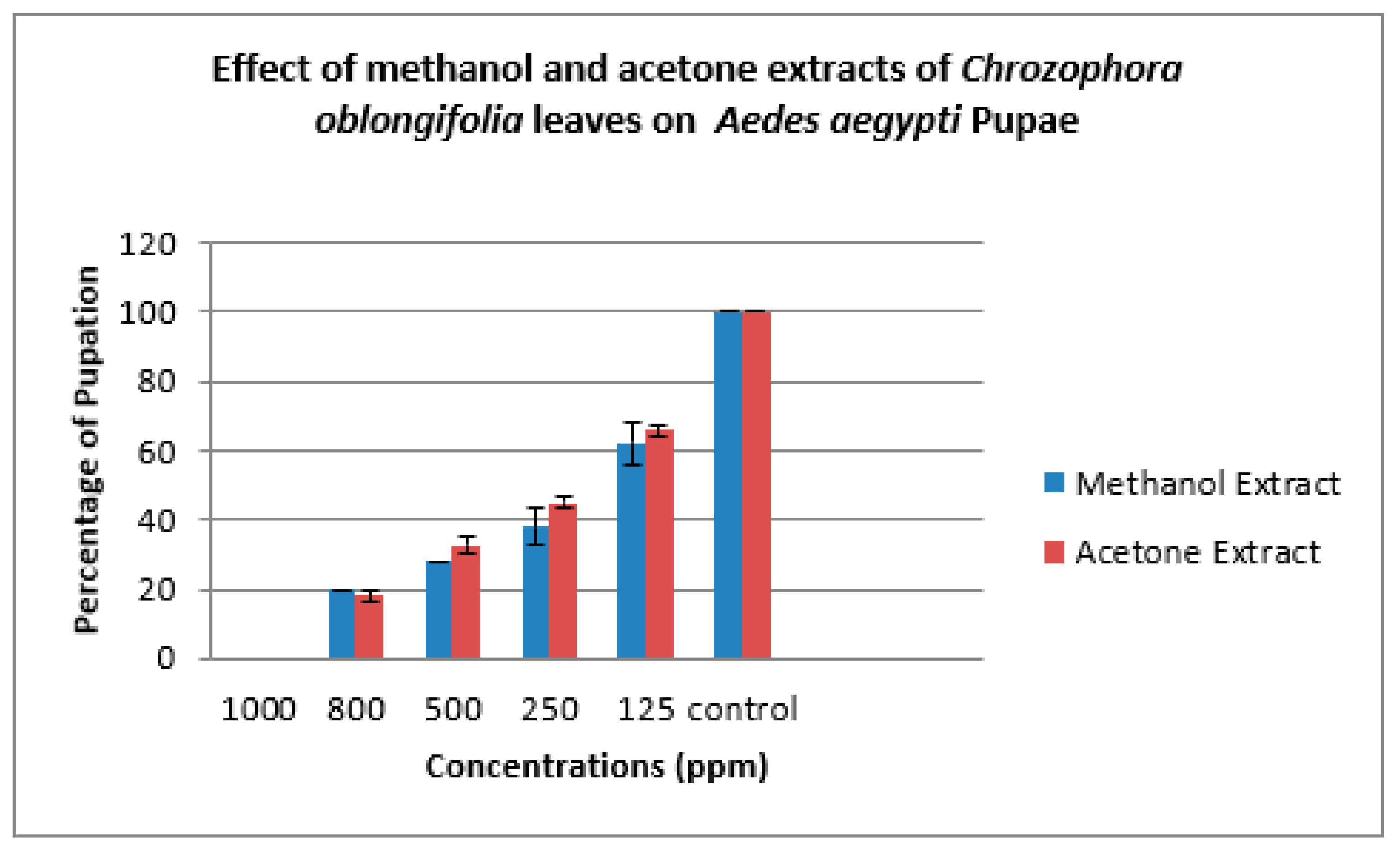

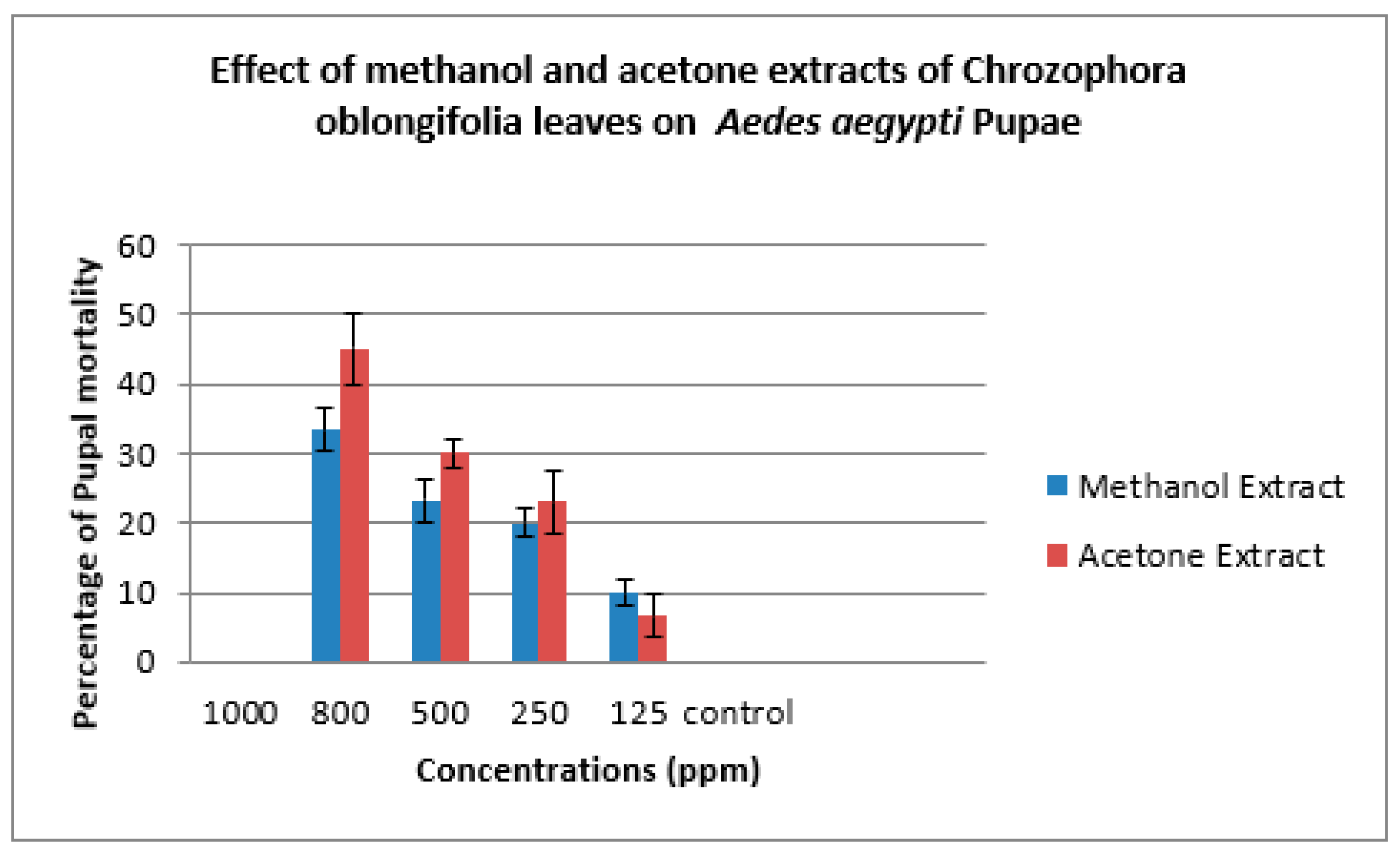

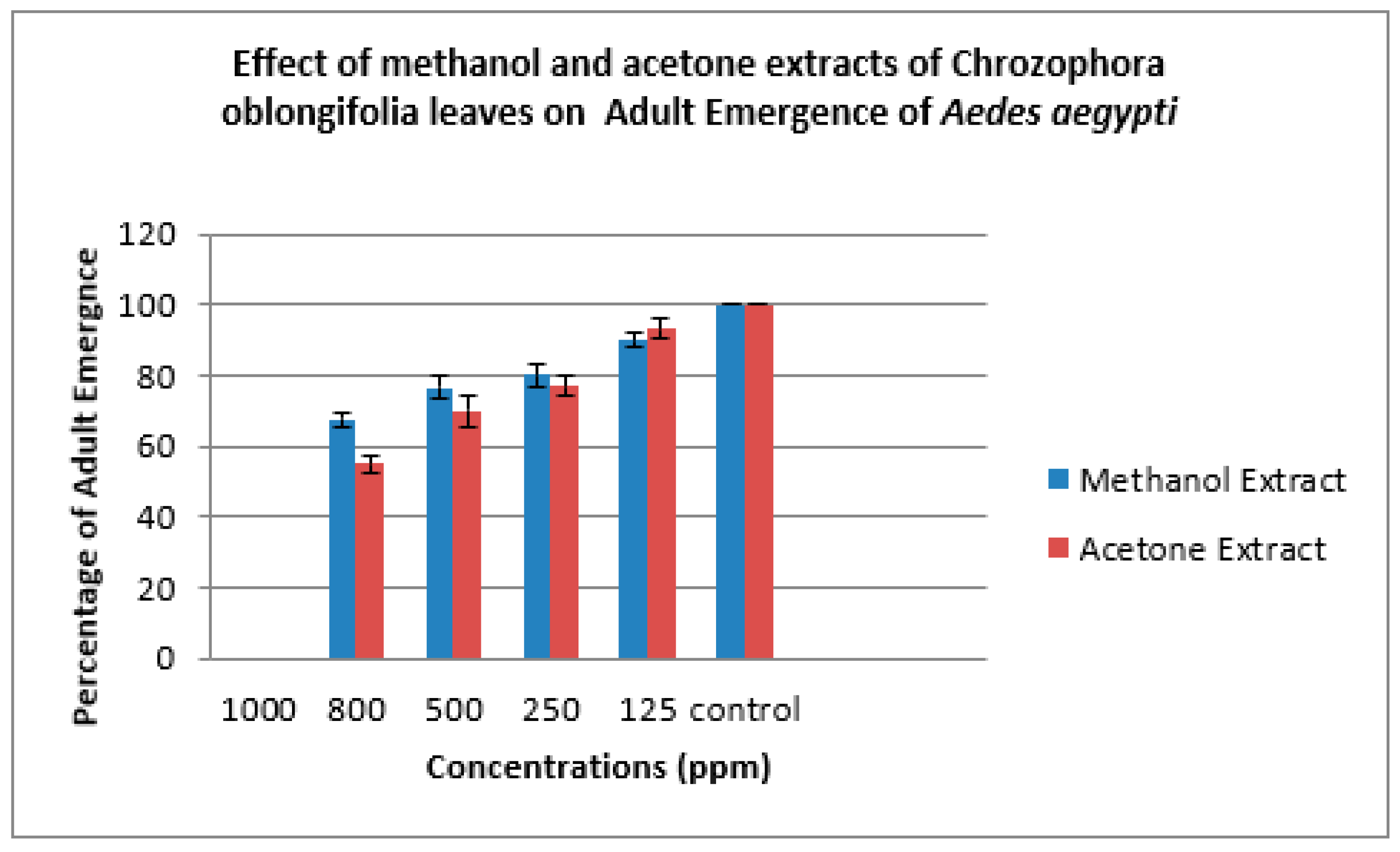

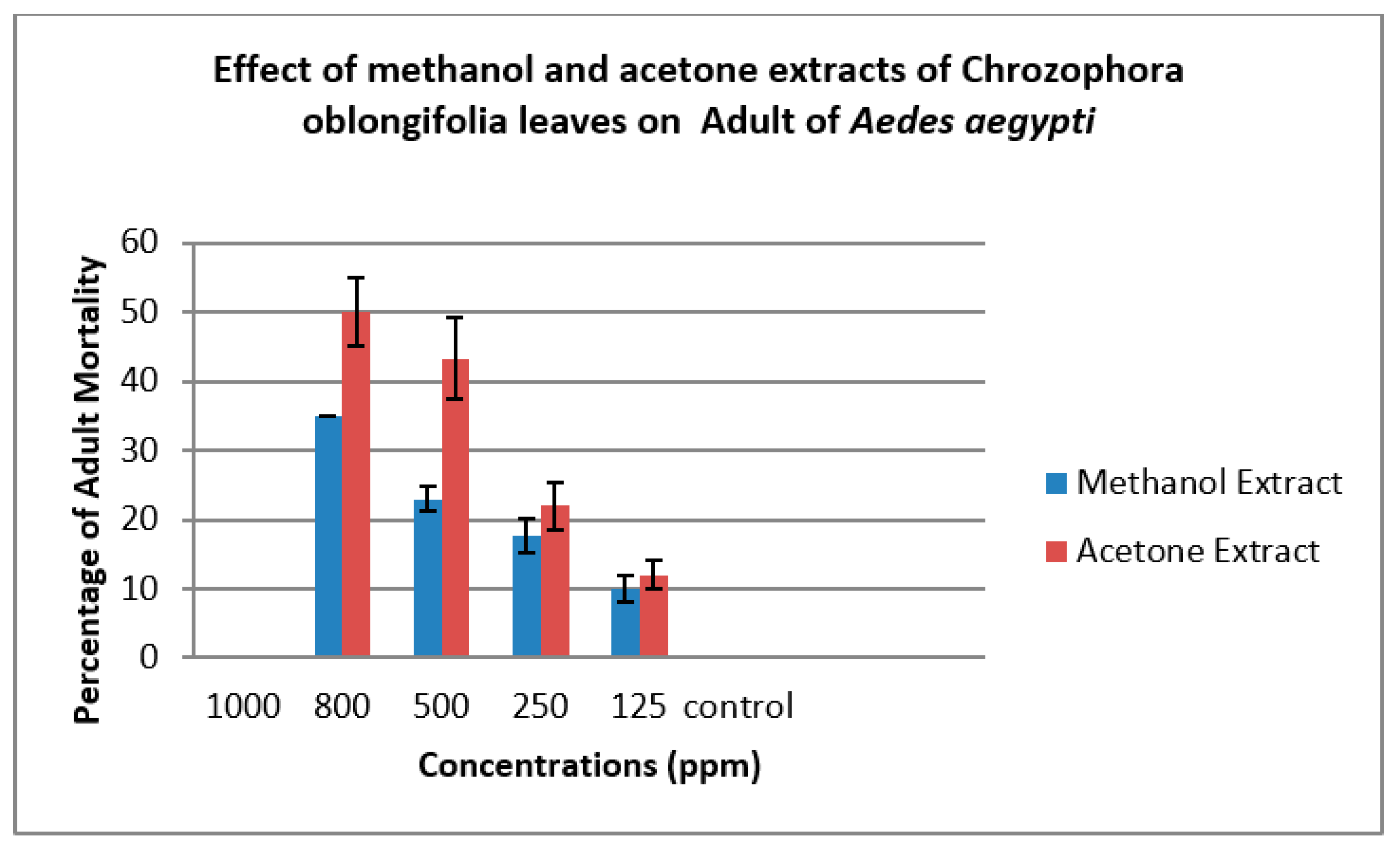

| Methanol Extract | ||||||

| Concs. ppm | Larva Mortality% | Larva duration/ days | Pupation% | Pupal Mortality% | Adult Emergency% | Ault Mortality% |

| 1000 | 100.00±0.00 | ---- | ------ | ------ | ------- | ---- |

| 800 | 80.00±0.00 | 6.33±1.00 | 20.00±0.00 | 33.33±3.00 | 67.67±2.00 | 35.00±0.00 |

| 500 | 72.00±0.00 | 7.33±1.00 | 28.00±0.00 | 23.33±3.00 | 76.67±3.00 | 23.00±2.00 |

| 250 | 62.00±5.00 | 6.00±1.00 | 38.0±5.00 | 20.00±2.00 | 80.00±3.00 | 17.67±3.00 |

| 125 | 38.00±6.00 | 7.00±0.00 | 62.00±6.00 | 10.00±2.00 | 90.00±2.00 | 10.00±2.00 |

| Control | 0 | 5.00±0.00 | 100.00±0.00 | 0 | 100.00±0.00 | 0 |

| Acetone Extract | ||||||

| Concs. ppm | Larva Mortality% | Larva duration/ days | Pupation% | Pupal Mortality% | Adult Emergency% | Ault Mortality% |

| 1000 | 100.00±0.00 | ------ | ----- | ---- | ------ | ----- |

| 800 | 82.00±2.00 | 5.33±1.00 | 18.00±0.00 | 45.00±5.00 | 55.00±3.00 | 50.00±5.00 |

| 500 | 67.33±2.00 | 6.33±1.00 | 32.67±2.00 | 30.00±2.00 | 70.00±4.00 | 43.33±6.00 |

| 250 | 55.00±2.00 | 6.67±1.00 | 45.00±2.00 | 23.00±4.00 | 77.00±3.00 | 22.00±3.00 |

| 125 | 34.00±2.00 | 6.67±1.00 | 66.00±2.00 | 6.67±3.00 | 93.33±3.00 | 12.00±2.00 |

| Control | 0 | 5.00±0.00 | 100.0±0.00 | 0 | 100.00±0.00 | 0 |

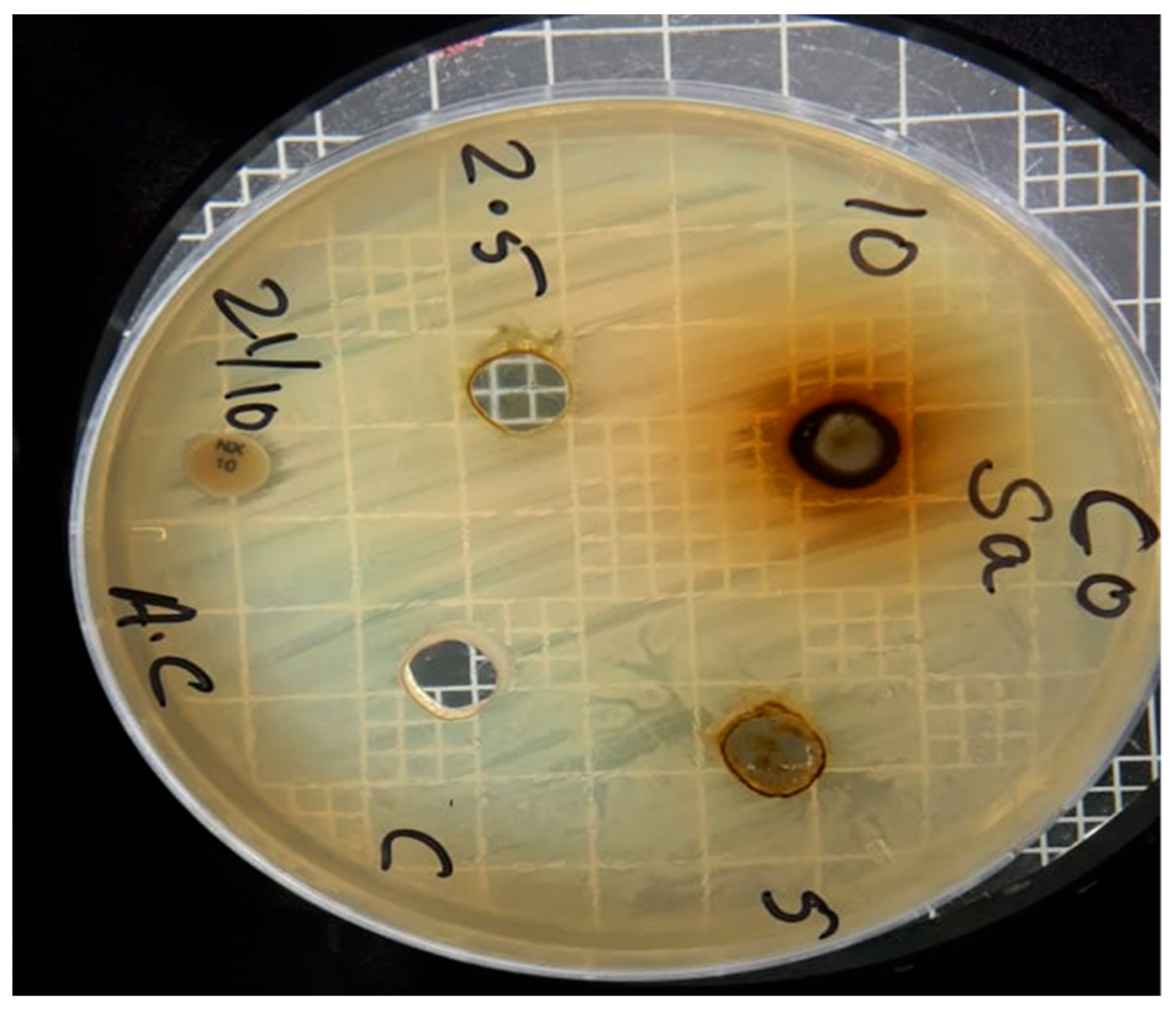

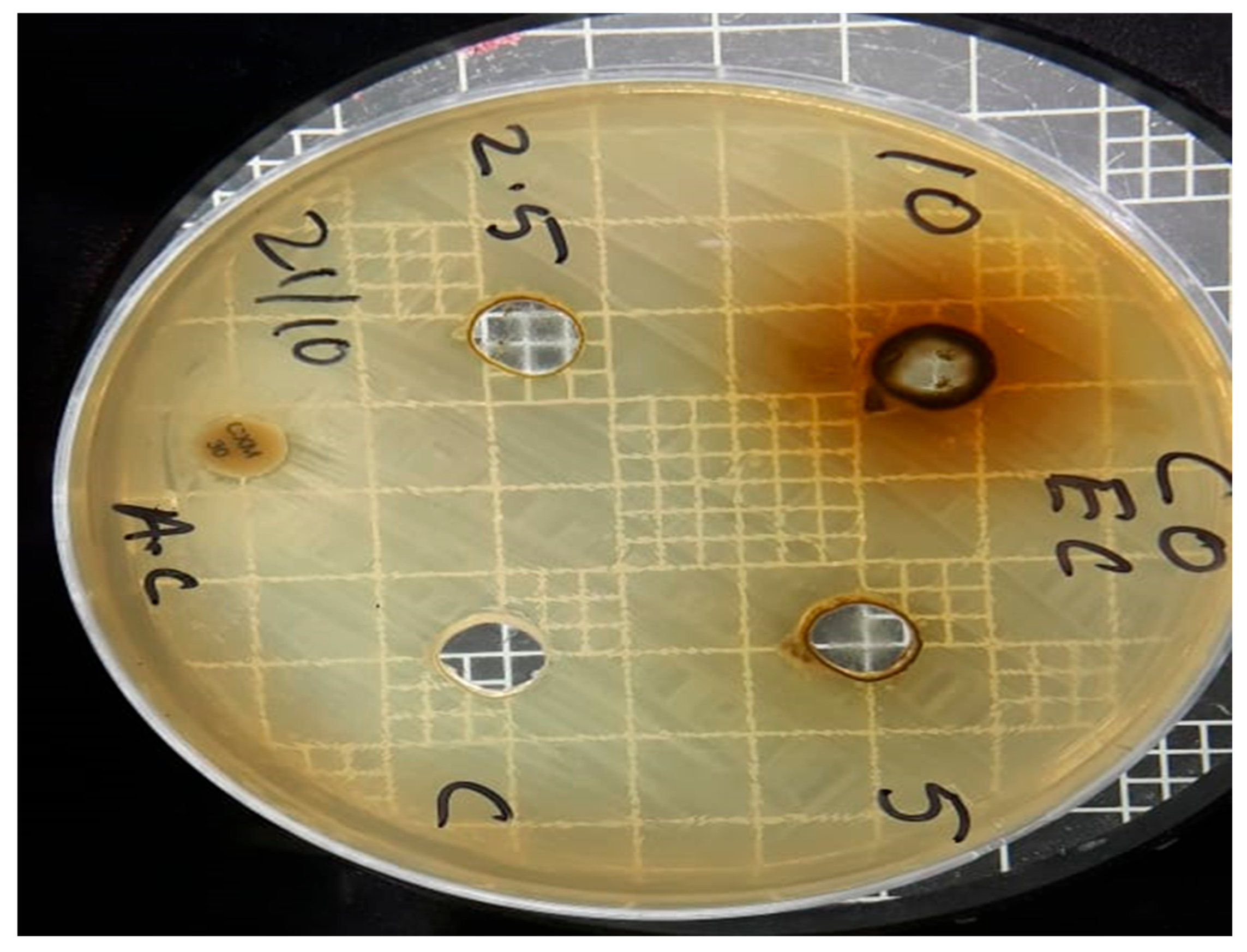

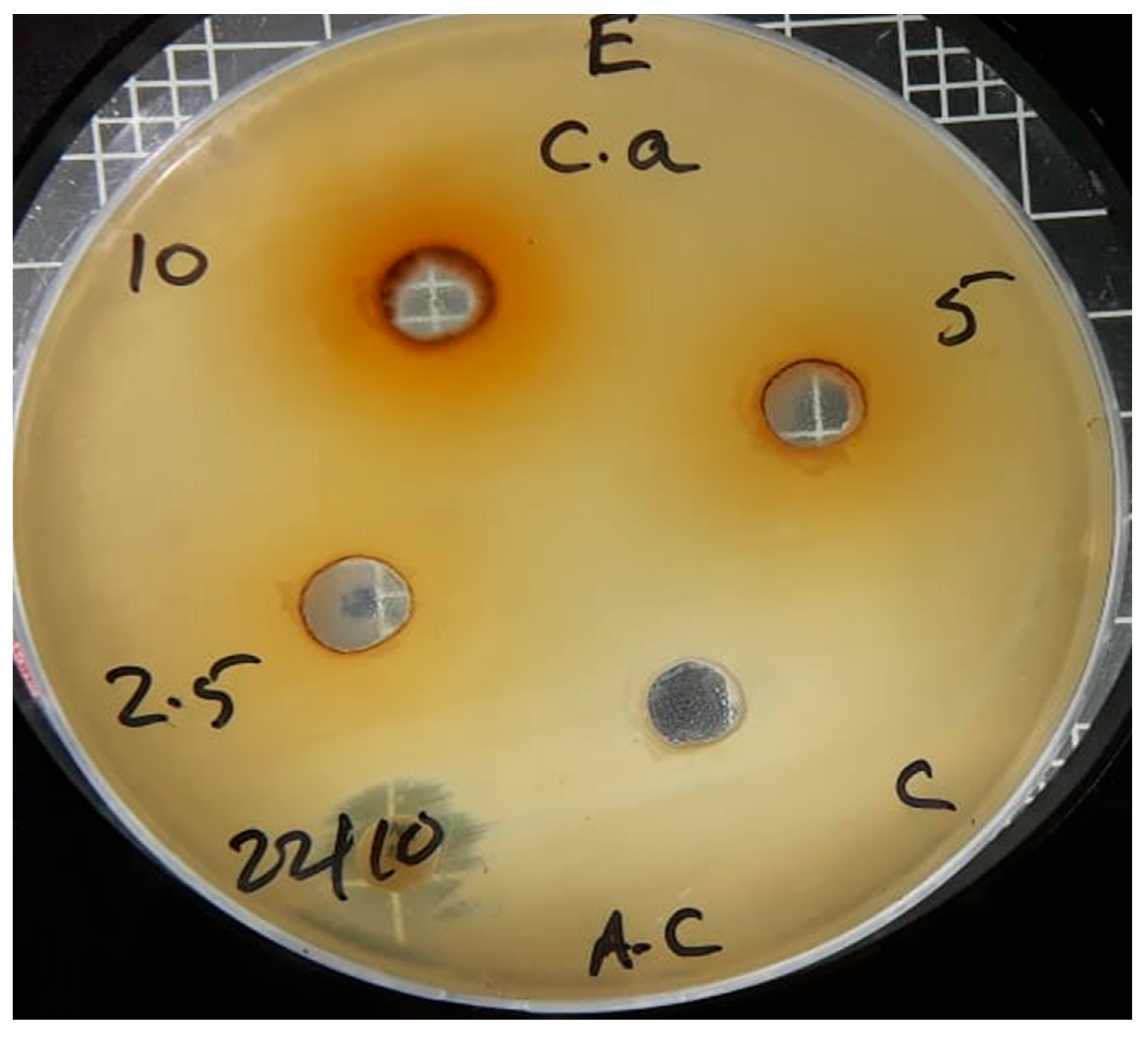

| Sr no. | Microbial strains | Methanol leaves extract of Chrozophora oblongifolia | ||

| Concentrations (ppm) | ||||

| 10000 | 5000 | 2500 | ||

| 1 | S. aureus | 14 mm | 11 mm | 0 |

| 2 | E. coli | 17 mm | 13 mm | 0 |

| 3 | Candida albicans | 16 mm | 0 | 0 |

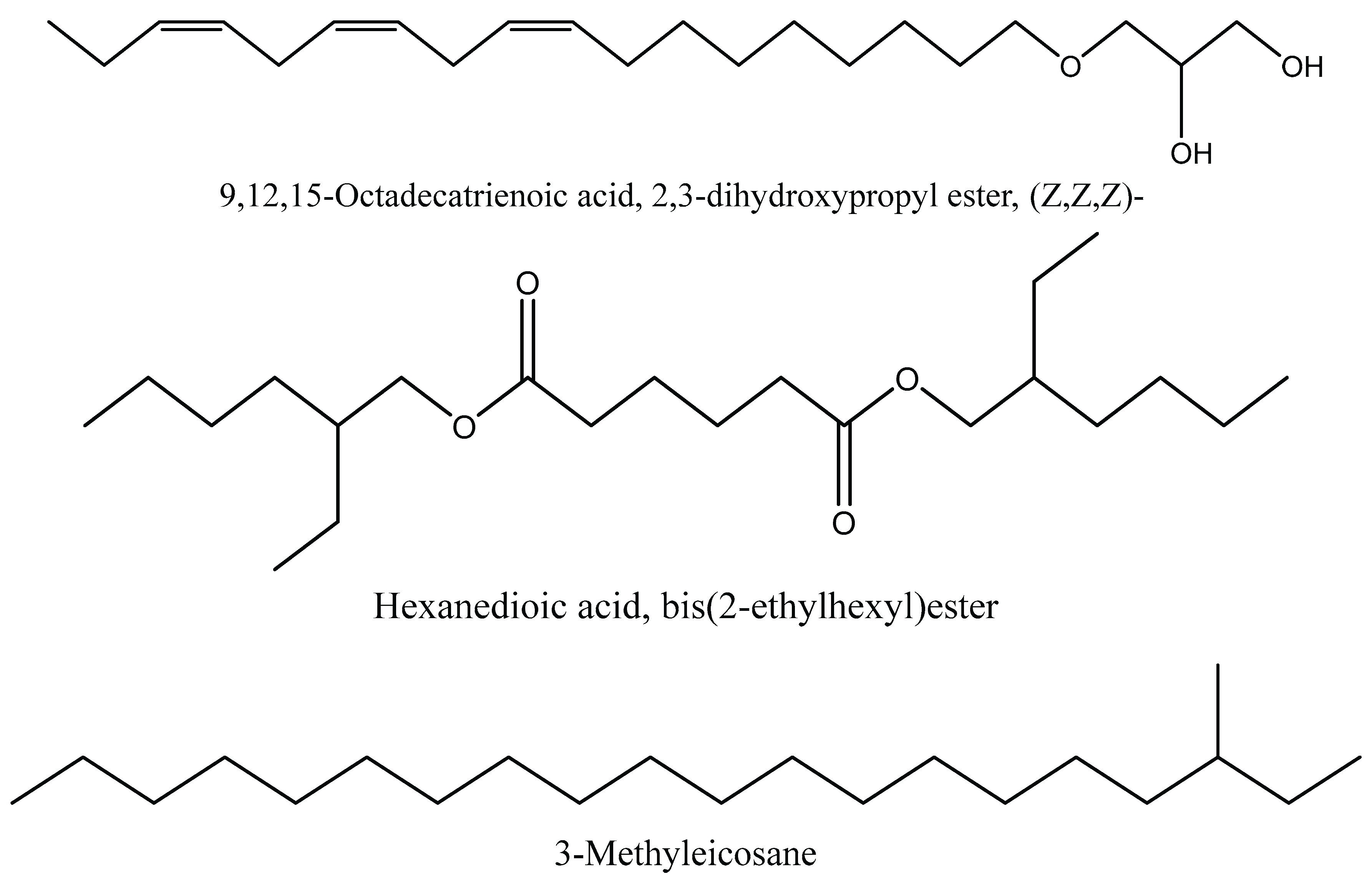

| Molecular Formula | Compound Name | Peak Area % | RT |

| C21H44 | 3-Methyleicosane | 1.01 | 11.38 |

| C25H44N2O5S | 2-Myristynoyl pantetheine | 0.51 | 16.92 |

| C13H26O2 | Methyl 10-methylundecanoate | 0.68 | 17.35 |

| C15H30O2 | Tetradecanoic acid, methyl ester | 0.52 | 18.95 |

| C18H24O | Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17á-ol | 0.54 | 19.29 |

| C24H46O2 | Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2-octyl-, methyl ester | 0.48 | 19.47 |

| C24H46O2 | Cyclopropanedodecanoic acid, 2-octyl-, methyl ester | 0.51 | 19.68 |

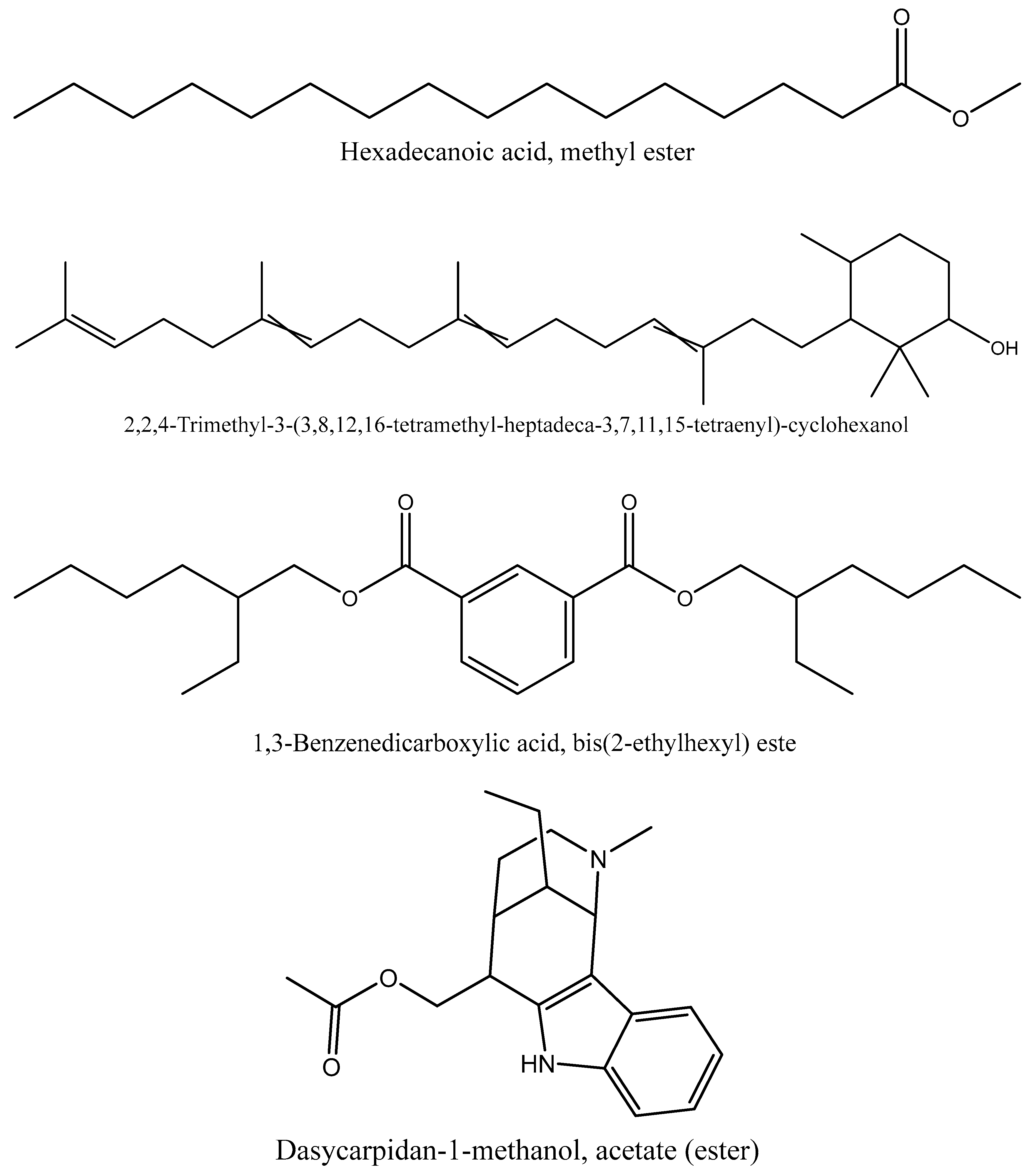

| C17H34O2 | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 3.74 | 20.37 |

| C21H36O4 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester, (Z,Z,Z)- | 2.67 | 21.52 |

| C20H26N2O2 | Dasycarpidan-1-methanol, acetate (ester) | 3.44 | 21.96 |

| C22H42O4 | Hexanedioic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) este | 15.59 | 22.14 |

| C28H42O2 | 3,4',5,6'-tetra-tert-butylbiphenyl-2,3'-diol | 0.52 | 22.92 |

| C22H42O4 | Hexanedioic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester | 28.18 | 23.2 |

| C38H74O2 | Oleic acid, eicosyl ester | 0.44 | 23.8 |

| C30H42Cl2N4O3 | 9-(2',2'-Dimethylpropa noilhydrazono)-3,6-dic hloro-2,7-bis-[2-(dieth ylamino)-ethoxy]fluore | 0.47 | 24 |

| C41H64O13 | Digitoxin | 0.48 | 24.14 |

| C24H38O4 | 1,3-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) este | 3.6 | 24.75 |

| C24H38O4 | 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) este | 1.76 | 25.08 |

| C30H52O | 2,2,4-Trimethyl-3-(3,8,12,16-tetramethyl-hep tadeca--3,7,11,15-tetraenyl)-cyclohexanol | 4.06 | 25.4 |

| C44H78O2 | Cholesterol margarate | 0.81 | 25.95 |

| C28H44O4 | 9-Octadecenoic acid, (2-phenyl-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)methyl ester, cis- | 0.63 | 26.44 |

| C24H30O7 | 9,11,18-Trihydroxy-6,18-epoxypimara-5,8(1 4),15-trien-7-one, 2Ac derivative | 0.53 | 27.47 |

| C26H44O5 | Ethyl iso-allocholate | 0.59 | 28.13 |

| Sr. no. | Compound | Peak Area % | Biological activity |

| 1 | Hexanedioic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester | 28.18% | Antioxidant and antibacterial activity (31) |

| 2 | Hexanedioic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester | 15.59 % | Antioxidant and antibacterial activity (31) |

| 3 | 2,2,4-Trimethyl-3-(3,8,12,16-tetramethyl-heptadeca--3,7,11,15-tetraenyl-cyclohexanol | 4.06 % | Antidiabetic effect (32) |

| 4 | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 3.74% | Antimicrobial (33) |

| 5 | 1,3-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester | 3.6 % | Anticancer, larvicidal, antibacterial, antifungal, antimutagenic and cytotoxic effect(34, 35) |

| 6 | Dasycarpidan-1-methanol, acetate (ester) | 3.44% | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antimicrobial anticancer, angiogenesis and analgesic property (36) |

| 7 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester, (Z,Z,Z)- | 2.67% | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticancer, and anti –inflammatory activity (37) |

| 8 | 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis (2-ethylhexyl) ester | 1.76% | Antimicrobial and larvicidal (38, 39) |

| 9 | 3-Methyleicosane | 1.01 % | Antifungal, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and cytotoxic effect. (40) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).