1. Introduction

Using technology in education, especially through virtual labs (VLs), transforms students from passive listeners into active investigators and enhances conceptual mastery [

1,

2,

3]. The teaching of physics in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) plays a central role in students’ scientific education. In the towns of Inkisi and Kimpese, schools face significant challenges, such as a lack of hands-on laboratories, a shortage of well-trained educators, frequent power outages, and poor internet connectivity.

This situation has forced physics teachers to favor a strictly theoretical approach, thereby limiting students’ experience to a bookish and abstract assimilation of fundamental concepts. The repercussions of this educational shortfall are numerous, including a series of common conceptual and terminological confusions in mechanics, such as the distinction between path and trajectory, speed and acceleration, or weight and mass [

4,

5,

6]. These difficulties are further exacerbated by misconceptions, which are considered cognitive obstacles, making the acquisition of key concepts even more challenging [

7].

Moreover, as some studies confirm, there is a significant gap between students’ performance in physics in sub-Saharan African countries compared to developed nations. This gap is attributed, among other factors, to the lack of material resources, the pedagogical shortcomings of teachers, the prioritization of theory over practice, and insufficient mastery of technology [

8].

VLs are often considered as a reliable solution to the shortage of physics laboratories in schools across sub-Saharan Africa. They help overcome economic challenges related to acquiring equipment for the construction of physical hands-on labs [

8,

9]. However, most of them are global, meaning they are designed for practical physics education in a general context. As a result, they overlook the specific needs of physics education in the DRC and do not always align with the current curriculum.

In this article, we propose a VL that addresses both the economic challenges faced by developing countries and the curricular requirements of the DRC:

Bazin-R VirtLab (BRVL). Such an approach has already been proposed by several researchers in various parts of the world [

1,

10,

11,

12,

13].

However, most of publications on VLs focus solely on the purely technical aspects or the pedagogical and didactic implications of VLs. The evaluations they present of VLs overlook the robust comparative methodologies offered by multi-criteria aggregation functions.

In our study, we not only propose a custom-designed VL tailored for physics education in the DRC, but, more importantly, we evaluate it alongside other VLs using multi-criteria analysis methods, based on pedagogical criteria established by professionals.

To validate BRVL, we used the ELECTRE I, ELECTRE II, ELECTRE TRI, PROMETHEE I, PROMETHEE II, TOPSIS, and AHP methods. These approaches were independently applied to compare BRVL with several global, free, and offline VLs. Prior to this, the weights of the selected criteria were determined using Conjoint Analysis (CA). The TOPSIS, AHP, ELECTRE II, and PROMETHEE II methods allow for ranking alternatives (VLs) from best to worst. Although ELECTRE I and PROMETHEE I are designed for a different type of decision problem (choice), they help identify a set of non-dominated alternatives called the “core.” ELECTRE TRI is dedicated to categorizing alternatives into different levels (“High”, “Medium”, and “Low”). The advantage of ELECTRE methods is that they reveal non-compensatory dynamics. Indeed, with ELECTRE, a low performance on a single criterion could eliminate an alternative despite its excellent performance on other criteria.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the literature review. In

Section 3, we outline our research methodology.

Section 4 summarizes the key findings of our work. The results are discussed in

Section 5, followed by the conclusion of our study in

Section 6.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Virtual Labs in STEM Education

STEM education has experienced rapid growth thanks to recent advancements in VLs. Indeed, more and more, educators and learners see VLs as an essential tool for interactive and evolving experimentation.

Table 1 highlights several recent studies on the pedagogical impact of VLs in STEM education. While most of these studies emphasize advantages such as cost-effectiveness, time savings, and user-friendliness [

10], gaps remain in assessing curriculum alignment, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. This table underscores the need for tools like BRVL that prioritize educational outcomes specific to a given region.

2.2. MCDA in Educational Technology

MCDA methods provide a systematic approach to objectively evaluating educational technologies.

Table 2 lists several recent studies that apply multi-criteria aggregation methods to assess learning tools. As the reader may notice, none of these studies incorporate conjoint analysis for determining criterion weights. Furthermore, the criteria considered in these studies are often technical rather than pedagogical. By introducing BRVL, we hope to bridge this gap.

2.3. Conjoint Analysis

Conjoint Analysis (CA) is a technique that employs a decomposition approach to evaluate the value of different attribute levels based on respondents’ assessments of hypothetical profiles called “plan cards” [

28]. CA was introduced by Green and Srinivasan [

29] in the early 1970s. The first mention of CA appeared a few years later [

30], before being updated and expanded in the early 1990s. Since its proposal, CA has gained significant popularity among researchers and industry professionals as a key methodology for assessing buyer preferences and trade-offs between products and services with multiple attributes [

31].

The CA involves three steps:

- 1.

-

Preference measurement: Preferences are assessed through ranking or rating tasks. The relative importance

of attribute

k is given by Equation

1:

Where is the utility of the level j of the attribute k.

- 2.

-

Utility estimation: Utilities values

are estimated using models such as MONANOVA, OLS, LINMAP, PROBIT, or LOGIT as shown in Equation

2, in the case of linear models:

Where represents the parameter estimate for level j of attribute k.

- 3.

Experiential design: Fractional factorial designs, such as Latin squares, reduce the number of profiles required for analysis. For three attributes A, B, and C, each with three levels, a Latin square reduces the total profiles from 27 to 9.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.1.1. Presentation of BRVL

“Bazin-R VIRTLAB” (BRVL) is an educational tool designed to digitize hands-on activities traditionally conducted in physical laboratories through 3D simulations on a computer. It is developed in alignment with the current school curriculum of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

BRVL consists of several modules, including essential knowledge to master (courses), identification and correction of misconceptions, simulations, quizzes distributed across all six taxonomic levels of Bloom’s scale [

32], and answer keys for the quizzes.

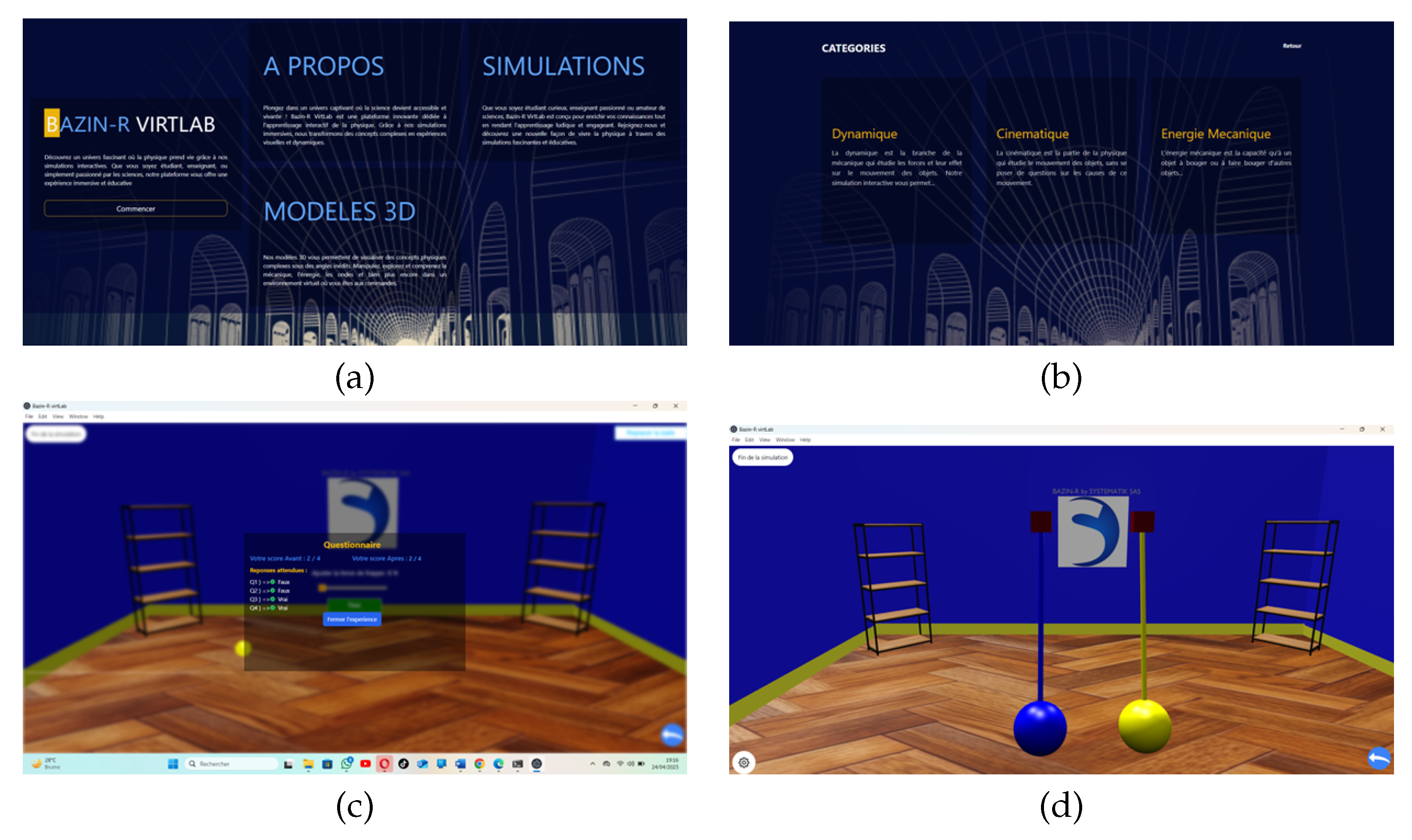

Figure 1 illustrates some of BRVL’s interfaces. These interfaces – Home page (

Figure 1-a), menu page of essential knowledge (

Figure 1-b), misconceptions identification page (

Figure 1-c), and example of a simulation (

Figure 1-d) – are designed to be user-friendly, and their ease of use is so remarkable that almost no prior training is required before using BRVL.

3.1.2. Technical Description of Competing VLs

The towns of Kimpese and Kisantu face several challenges that hinder the integration of ICTs in education. The most significant difficulties include frequent power outages, poor internet connectivity, the high cost of internet subscriptions, unemployment, and widespread poverty.

Given these factors, we have selected only VLs that are free and capable of functioning offline. BRVL, of course, has also been designed with these challenges in mind.

In total, five VLs have been selected and compared to BRVL based on criteria that will be defined later in this paper.

Table 3 provides a technical overview of the six competing VLs.

3.2. Selected Criteria

A criterion is a partial evaluation function that assigns a value to alternatives and allows their comparison according to a specific dimension. Without criteria, evaluations would be purely subjective. Criteria ensure comparability and guarantee the reliability of the decisions made.

Table 4 presents the most commonly used criteria for evaluating educational tools (such as digital, ICT, and mechanical tools) and supports their selection with the latest references.

The criteria were selected based on their relevance and frequency in scientific publications addressing the evaluation of educational tools. There are many such criteria, but to avoid overlap, we only retained those that provide the most comprehensive explanation of our problem.

3.3. MCDA Methods

This subsection is dedicated to describing the MCDA methods used either for selecting or ranking competing VLs, depending on their intended application. The choice of methods is based on their acceptance in the academic, research, and industrial sectors.

Table 5 presents all the MCDA methods used in our article to compare the VLs, based on the judges’ evaluations conducted using the selected criteria.

3.4. Survey Protocol

In this subsection, we describe the investigation process and provide details on the methodology, data collection procedures, and analysis framework used in the field study.

3.4.1. Profile of Respondents

We conducted a full-population survey of secondary school teachers in the towns of Inkisi and Kimpese, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). There are 22 secondary schools in total in these two towns, each with only one Physics teacher.

3.4.2. Requested Survey Data

The respondents were asked to rate the fictitious VLs generated using the ORTHOPLAN method in SPSS on a scale from 0 to 10. Only nine cards were generated, whereas an exhaustive set would have contained 54. The nine generated VLs are listed in

Table 6. Applying conjoint analysis (CA) to these data enables the determination of the respondents’ utility shares for the criteria based on their modalities. These utility shares will subsequently be considered as weights for these criteria.

After evaluating the fictitious VLs, the respondents were invited to assess the real VLs that were to be compared. They were asked to rate each VL on a scale from 0 to 10 for each criterion. Prior training on the use of each of the six competing VLs was required before this exercise.

We then aggregated the data by calculating the arithmetic mean of the scores for each VL per criterion. For example, the average score of the VL Algodoo for “Usability” is the arithmetic mean of all the ratings assigned to it by the 22 respondents.

3.4.3. Decision Table Formation

The decision table consists of criteria, weights for selected criteria, alternatives (VLs), and the performance of these alternatives on the chosen criteria. The four selected criteria were chosen due to their high frequency in publications evaluating educational tools. The VLs considered do not represent the entire universe of VLs; their selection was based on the socio-economic conditions of the investigated areas.

It was essential to prioritize VLs that do not require highly powerful computers (which would, of course, be expensive), that function without an Internet connection (offline), and that are primarily designed for teaching Physics in secondary school.

3.4.4. Implementation of MCDA Methods

The final step is to apply the MCDA methods to the obtained decision table. It should be noted that some methods, such as those in the ELECTRE and PROMETHEE families, require parameter tuning before use.

Table 7 specifies the values assigned to the required parameters for each method.

ELECTRE analyses were conducted by considering concordance and discordance thresholds of 0.70 and 0.30, respectively. Additionally, for ELECTRE II, we applied a veto threshold , meaning that an alternative is automatically rejected if its performance on at least one criterion is less than or equal to (on a scale of 0–10), even if it excels in other criteria.

For the PROMETHEE methods, we set and , implying that a difference of 0.5 or less between two alternatives on a criterion is considered negligible, while a difference of 1.5 or more leads to a clear preference for the superior alternative.

To compare alternatives

and

according to criterion

, we use Equation

3 when

is to be maximized:

Where:

is the performance of alternative on criterion .

denotes the nearest integer to the real x. We admit that but .

is the mean deviation, and denote respectively maximal and the minimal values of .

The reader can easily verify that all AHP pairwise comparison matrices derived using this formula are consistent.

3.4.5. Sensitivity to Parameter Values

The choice of values assigned to the parameters of MCDA methods can be highly influential in the final decision. That is why we deemed it necessary to verify whether the results obtained with the selected parameter values in

Table 7 were stable and not excessively dependent on parameter variation. If they were, a change in parameter settings would lead to different results from those previously obtained, making them questionable. This would indicate that the outcomes are not robust or are merely a product of arbitrary parameter choices.

Although the parameter settings are within standard norms (See

Table 8), we conducted a sensitivity analysis by modifying them. Each modified parameter creates a distinct scenario. Thus, for ELECTRE, we considered five scenarios for each veto value, with veto values ranging from 4 to 8, whereas for PROMETHEE, we explored eleven scenarios.

In

Table 9, we provide comprehensive information on the different scenarios of the ELECTRE and PROMETHEE methods. The assigned parameter values are those recommended in the literature (see

Table 8). By proceeding in this manner, we aim to assure the reader that the results obtained in favor of BRVL are not due to a strategic selection of parameter values designed to produce a favorable outcome for us.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Data Reliability

Table 10 provides results on the reliability of the data collected from respondents. The single measures ICC (0.089, p=0.000) indicate that judges have significant discrepancies in their assessments and that there is not a high level of individual reliability. The average measures ICC (0.702, p=0.000), on the other hand, suggest good agreement. This means that, collectively, the judges are consistent even though there are individual variations.

The Friedman test result “Between elements” () indicates that judges do not give the same evaluations to the VLs, which is expected in a comparative analysis like ours. The differences observed between the evaluated VLs are statistically significant (). The residual value () suggests that there is significant non-additivity. This implies that the criteria or judges’ evaluations are not simply cumulative in a linear manner.

Cronbach’s (0.787) and Cronbach’s for standardized data (0.793) indicate good internal reliability of the evaluations. The intra-population sum of squares (525.801) is higher than the between-persons sum of squares (166.994). This means that the variability in judgments is mainly due to differences between the elements rather than variations between the judges. The ratio between these two values shows that the effect of the evaluated elements is stronger than the effect of the judges, which aligns with good collective reliability.

Data transformation was not considered necessary as the current structure of the evaluations remains sufficient to reliably interpret the results.

4.2. Averaged Ratings

The grades assigned by the judges (physics teachers from schools in Kimpese and Inkisi) to the VLs, based on the selected criteria, are aggregated using the arithmetic mean (see

Table 11). For example, the aggregated rating of 7.4091 obtained by the VL Physion for the criterion ’Knowledge Construction’ is the arithmetic mean of the ratings assigned by the judges to this VL for the given criterion.

4.3. Criteria Weights

Table 12 shows that misconceptions correction and curriculum compliance are the most important criteria, with respective weights of 28.795% and 26.080%. Usability is the least important criterion, according to respondents. Additionally, respondents made two inversions in Knowledge Building and only one in Misconceptions Correction. This implies that their choices are consistent and stable. They seem to have a comprehensive understanding and a clear perception of each attribute and its levels.

The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (0.991) is close to 1, which means that the conjoint analysis model accurately explains the respondents’ choices. Kendall’s tau (0.889) suggests strong agreement in the rankings of the alternatives. Therefore, we can confidently conclude that the model is reliable, the responses are consistent, and the preferences are not influenced by random or incoherent answers.

4.4. Benchmarking VLs

Table 13 is the result of combining

Table 11 with the weighted criterion vector obtained through CA.

Table 14 provides the final results of the VL evaluation using the selected MCDA methods. There is complete consensus among the ranking-oriented methods: the BRVL virtual lab is ranked first, followed by Physic Virtual Lab, LVP, Virtual Lab, Algodoo, and Physion.

The ELECTRE I and PROMETHEE I methods (using both the usual and Gaussian functions) also agree on the best VLs (core set): BRVL and Physic Virtual Lab are the alternatives that were not outperformed. However, the core set consists only of BRVL when the linear function is used for PROMETHEE I.

The PROMETHEE II method produces the same ranking regardless of the function used. The ELECTRE TRI method classifies BRVL in the “High” category, LVP and Physic Virtual Lab in the “Medium” category, and the remaining VLs in the “Low” category.

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis results for the ELECTRE and PROMETHEE methods are unequivocal. Regardless of the scenario, BRVL is part of the core for ELECTRE I and PROMETHEE I and ranks first for ELECTRE II and PROMETHEE II. Moreover, the final ranking of VLs remains unaffected by modifications to the parameter values of these methods.

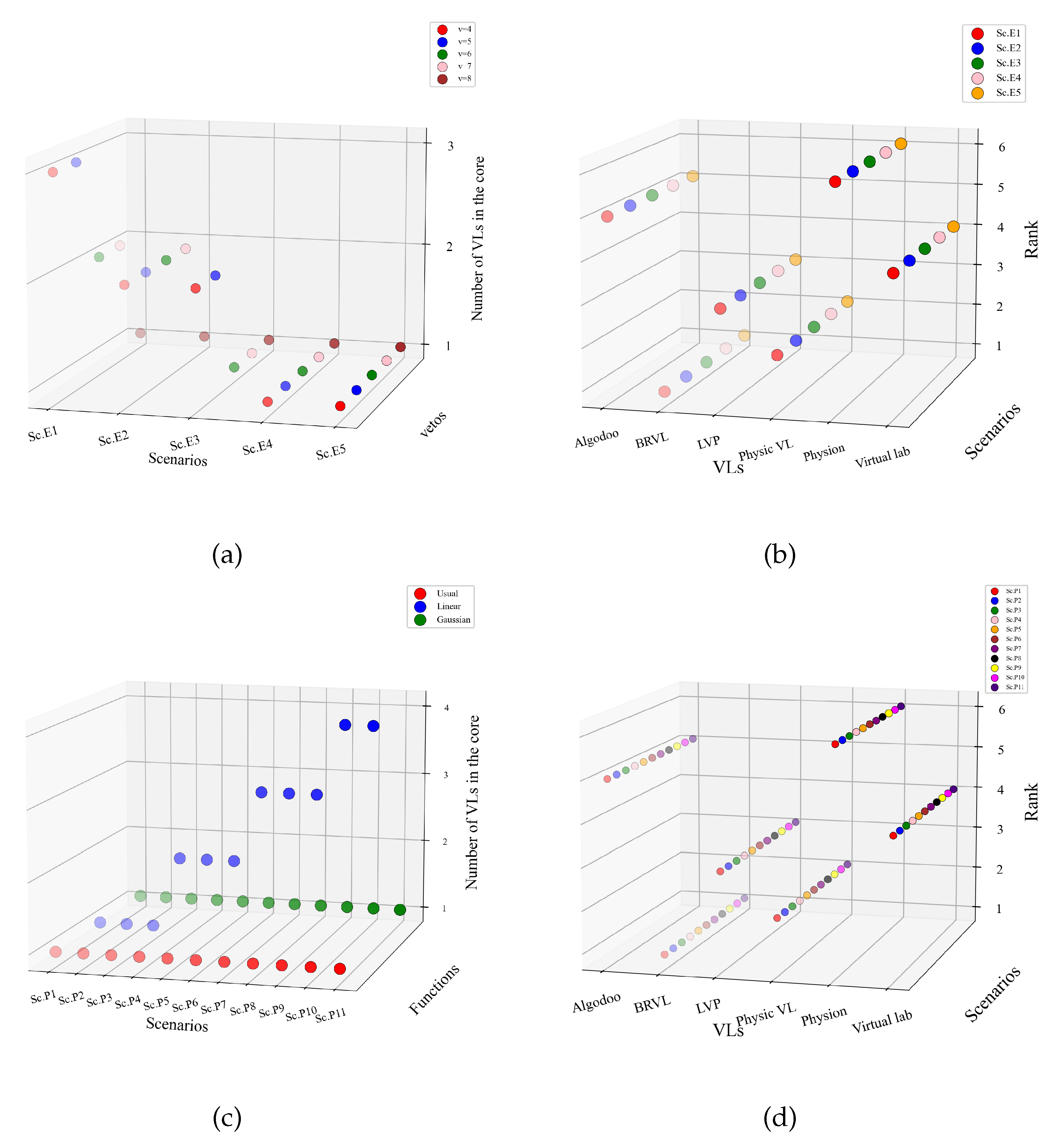

Figure 2 illustrates that, within the context of our study, the ELECTRE methods (

Figure 2-a for ELECTRE I and

Figure 2-b for ELECTRE II) and the PROMETHEE methods (

Figure 2-c for PROMETHEE I and

Figure 2-d for PROMETHEE II) exhibit strong robustness. However, it is worth noting that, for ELECTRE I, the core shrinks (from 3 to 1) as the concordance threshold increases, while ELECTRE II remains perfectly stable regardless of threshold values. Additionally, the core of PROMETHEE I expands (from 1 to 4) as the values of

q and

p increase for the linear function, while it remains a singleton for the usual and Gaussian functions, regardless of the values of

q and

p.

The ranking of VLs in PROMETHEE II remains unchanged, regardless of the values assigned to q and p or the function chosen (usual, linear, or Gaussian). As q and p increase, the net flows decrease, but the ranking order remains the same.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that the use of the BRVL adds significant value to physics education in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), particularly because its solution aligns with the local curriculum and is shown to be more effective than many global alternatives in correcting misconceptions.

In fact, the BRVL is unique in that it adapts to the limitations of Congolese secondary schools (difficulty accessing the Internet, limited equipment, and specific educational needs). In contrast to VLs made for high-resource contexts [

12,

13,

14,

15] or universities [

20,

21], the BRVL is preferred by its adaptability to the limitations of secondary Congolese schools (difficulty accessing the Internet, limited equipment, and specific educational needs). As noted by Refs. [

18,

19], low-cost VLs have the potential to transform STEM education in underequipped areas. Our novelty is in considering a lightweight platform, active pedagogy focused on common misconceptions of local students. This section discuss about how the BRVL goes beyond the bounds of traditional VLs [

17] while offering a replicable model for francophone countries with comparable resources.

5.1. Synthesis of Methodological and Conceptual Contributions

This research introduces a novel paradigm for integrating ICT into sub-Saharan African education through its dual innovation: a pedagogically grounded virtual laboratory framework, coupled with robust multi-method validation protocols. Two major advances emerge: robustness of results and prioritization of contextual criteria.

5.1.1. Robustness of Results

Despite their differences (compensatory

vs non-compensatory), ELECTRE, PROME-THEE, AHP, and TOPSIS techniques unanimously agreed that BRVL was the best one. This supports the findings of Ref. [

19] on the need for mixed methodologies. Our sensitivity analysis extends this idea by demonstrating that BRVL remains in the core even under highly stringent thresholds (

,

,

,

, etc.). Furthermore, PROMETHEE II net flows withstand variations in preference functions (Usual vs. Gaussian vs. Linear), surpassing standard robustness tests in the literature.

5.1.2. Prioritization of Contextual Criteria

The weight assigned to misperception correction (28.8 %) supports Ref. [

17], demonstrating an uncommon agreement with local demands. Compared to generic VLs like NEWTON [

13], which are usually developed for Western audiences, our approach performs better.

5.2. Break from Worldwide Models

BRVL’s use circumvents basic impediments of worldwide arrangements (e.g., Algodoo, Physion): Curricular misalignment, Targeted pedagogical shortcomings, and Technological advances and infrastructure constraints.

5.2.1. Curricular Misalignment

The systematic exclusion of global models from ELECTRE I/PROMETHEE I cores – even under maximally permissive parameter configurations – empirically validates the critical finding of Ref. [

20] : without curricular adaptation to national educational standards, virtual laboratories fail to achieve meaningful learning outcomes. Our multi-method analysis establishes that even marginal curricular deviations constitute disqualifying conditions, conclusively demonstrating the non-compensatory dominance of curriculum alignment in MCDA evaluation frameworks.

5.2.2. Targeted Pedagogical Shortcomings

Poor performance in misconception correction (the highest-weighted criterion) reveals a systemic bias in global VLs: some designs centered on 3D immersion [

14] neglect the mechanisms of cognitive deconstruction, which are essential in overcrowded classrooms where errors persist due to lack of individualized feedback. In contrast, BRVL establishes a new paradigm for “glocal” VLs – global in technology yet local in pedagogy. Its modular architecture (e.g., pre-encoded misconception library) may inspire adaptations for other STEM disciplines, as suggested by Ref. [

12].

5.3. Technological Advances and Infrastructure Constraints

Our thinking makes an essential contribution to the ongoing debate. BRVL distinguishes itself through intelligent dematerialization: unlike bandwidth-intensive VLs [

15], BRVL demonstrates that an offline solution for PCs or Android smartphones can also deliver sufficient fidelity for mechanics experiments.

6. Conclusion

Our study has demonstrated that BRVL significantly outperforms competing global alternatives, particularly concerning the two criteria with the highest weights: misconception correction (weighted at 28.8%) and curricular alignment with the fourth-year scientific physics program in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (weighted at 26.1%). This superiority is further reinforced by the robustness of the results obtained through the eight multicriteria methods employed in this study, as well as by the sensitivity analysis, which confirms BRVL’s resilience to extremely strict thresholds.

From a pedagogical standpoint, unlike other virtual physics laboratories, BRVL is specifically designed to suit the local educational context in the DRC – a developing country facing multiple challenges in equipping its scientific schools with modern laboratory facilities and materials.

From a theoretical perspective, our work has made a significant contribution to the development of a new MCDA evaluation framework for resource-constrained virtual physics laboratories. Practically, BRVL, due to its accessible architecture, offline functionality, low cost, and alignment with local curricula, can be replicated in other countries with similar contexts seeking to integrate ICT into their national curricula. The responsibility now lies with policymakers to allocate substantial budgets for the design and implementation of locally tailored virtual laboratories. Moreover, the BRVL could be integrated into the Congolese national curriculum to support not only the correction of misconceptions among young learners but also the teaching, learning, and assessment of physics.

Among its limitations, we highlight the restricted study area and its dependence on regions with easy access to electricity and smartphones. Moving forward, it is necessary to expand this research to other cities and provinces in the DRC, as well as to other STEM disciplines (such as mathematics, chemistry, and biology). Furthermore, versions adapted to Congolese and African regions where populations lack access to electricity should be developed. BRVL could also be utilized as an interface for conducting practical physics examinations within the Congolese National Baccalaureate. Over several years of longitudinal study, BRVL’s results could serve as the basis for future research aimed at refining its capabilities, including the automation of evaluations through the integration of appropriate algorithms (e.g., Python-based MCDA toolkit).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, RMB, RBMN, and JRMB; Data curation, RMB, RBMN and JRMB; Formal analysis, RBMN, JRMB, and GKK; Investigation, RMB; Methodology, RMB and RBMN; Software, RBMN, and JRMB; Supervision, RBMN, GKK and BNM; Validation, RBMN, RMB, JRMB and BNM ; Visualization, RBMN, RMB, GKK and BNM; Writing – original draft, RMB, RBMN ; Writing – review & editing, RBMN, JRMB and BNM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no external funding for this study.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact authors for data and materials requests.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their deep thanks for the referees’ valuable suggestions about revising and improving the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that none of the work reported in this paper could have been influenced by any known competing financial interests or personal relationships.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Betw. subj. |

Between subjects |

| BRVL |

Bazin-R VirtLab |

| Curr. compl. |

Curriculum compliance |

| Dev. Tech. |

Development Technology |

| df |

Degree of freedom |

| Know. build. |

Knowledge building |

| ICC |

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technology |

| Intra pop. |

Intra population |

| Misc. corr. |

Misconceptions correction |

| MCDA |

Multi-Criteria Decision Aid |

| Nonadd. |

Nonadditivity |

| Sig. |

Significance threshold |

| STEM |

Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| Sum Sq. |

Sum of squares |

| VL |

Virtual lab |

References

- Dori, Y.J.; Belcher, J. How does technology-enabled active learning affect undergraduate students’ understanding of electromagnetism concepts? Journal of the learning sciences 2005, 14, 243–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefalis, C.; Skordoulis, C.; Drigas, A. Digital Simulations in STEM Education: Insights from Recent Empirical Studies, a Systematic Review. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberbosch, M.; Deiters, M.; Schaal, S. Combining Virtual and Hands-on Lab Work in a Blended Learning Approach on Molecular Biology Methods and Lab Safety for Lower Secondary Education Students. Education Sciences 2025, 15, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, V.; Brosh, Y.; Sneider, C. Weight, Mass, and Gravity: Threshold Concepts in Learning Science. Science Educator 2016, 25, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Taibu, R.; Rudge, D.; Schuster, D. Textbook presentations of weight: Conceptual difficulties and language ambiguities. Physical Review Special Topics-Physics Education Research 2015, 11, 010117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibu, R.; Schuster, D.; Rudge, D. Teaching weight to explicitly address language ambiguities and conceptual difficulties. Physical Review Physics Education Research 2017, 13, 010130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, J.P.; Peterfalvi, B. Obstacles et construction de situations didactiques en sciences expérimentales. Aster: Recherches en didactique des sciences expérimentales 1993, 16, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, F.E.; Ojobola, F.B. Improving Learning of Practical Physics in Sub-Saharan Africa—System Issues. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education 2022, 22, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, F. Advancing practical physics in Africa’s schools; Open University (United Kingdom), 2017.

- Aljuhani, K.; Sonbul, M.; Althabiti, M.; Meccawy, M. Creating a Virtual Science Lab (VSL): the adoption of virtual labs in Saudi schools. Smart Learning Environments 2018, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrah, M.; Humbert, R.; Finstein, J.; Simon, M.; Hopkins, J. Are virtual labs as effective as hands-on labs for undergraduate physics? A comparative study at two major universities. Journal of science education and technology 2014, 23, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laseinde, O.T.; Dada, D. Enhancing teaching and learning in STEM Labs: The development of an android-based virtual reality platform. Materials Today: Proceedings 2024, 105, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, T.; Ghergulescu, I. NEWTON virtual labs: introduction and teacher perspective. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 17th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT). IEEE, 2017, pp. 343–345.

- Sypsas, A.; Paxinou, E.; Zafeiropoulos, V.; Kalles, D. , Virtual Laboratories in STEM Education: A Focus on Onlabs, a 3D Virtual Reality Biology Laboratory. In Online Laboratories in Engineering and Technology Education: State of the Art and Trends for the Future; May, D.; Auer, M.E.; Kist, A., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024; pp. 323–337. [CrossRef]

- August, S.E.; Hammers, M.L.; Murphy, D.B.; Neyer, A.; Gueye, P.; Thames, R.Q. Virtual engineering sciences learning lab: Giving STEM education a second life. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies 2015, 9, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdan, A.P. Tailoring STEM Education for Slow Learners Through Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Emerging Trends in Electrical, Electronic and Communications Engineering (ELECOM). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–7.

- Gnesdilow, D.; Puntambekar, S. Middle School Students’ Application of Science Learning From Physical Versus Virtual Labs to New Contexts. Science Education 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yordanov, T.; Mihailov, N.; Gabrovska-Evstatieva, K. Low-cost Remote Lab on Renewable Energy Sources with a Focus on STEM Education. In Proceedings of the 2023 18th Conference on Electrical Machines, Drives and Power Systems (ELMA). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nedungadi, P.; Raman, R.; McGregor, M. Enhanced STEM learning with Online Labs: Empirical study comparing physical labs, tablets and desktops. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Frontiers in Education conference (FIE). IEEE; 2013; pp. 1585–1590. [Google Scholar]

- El Kharki, K.; Berrada, K.; Burgos, D. Design and implementation of a virtual laboratory for physics subjects in Moroccan universities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J.; Devi, A.; Ray, B. Virtual laboratories in tertiary education: Case study analysis by learning theories. Education Sciences 2022, 12, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonje, S.A.; Pawar, R.S.; Shukla, S. Assessing blockchain-based innovation for the “right to education” using MCDA approach of value-focused thinking and fuzzy cognitive maps. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 2021, 70, 1945–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.S.; González-Gómez, D. MCDA/F-DEMATEL/ICTs Method Under Uncertainty in Mathematics Education: How to Make a Decision with Flipped, Gamified, and Sustainable Criteria. In Decision Making Under Uncertainty Via Optimization, Modelling, and Analysis; Springer, 2025; pp. 91–113.

- Youssef, A.E.; Saleem, K. A hybrid MCDM approach for evaluating web-based e-learning platforms. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 72436–72447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransikarbum, K.; Leksomboon, R. Analytic hierarchy process approach for healthcare educational media selection: Additive manufacturing inspired study. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 8th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications (ICIEA). IEEE; 2021; pp. 154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Kurilovas, E.; Kurilova, J. Several decision support methods for evaluating the quality of learning scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 3rd Workshop on Advances in Information, Electronic and Electrical Engineering (AIEEE). IEEE; 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hisamuddin, M.; Faisal, M. Exploring Effective Decision-Making Techniques in Learning Environment: A Comprehensive Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 Second International Conference Computational and Characterization Techniques in Engineering & Sciences (IC3TES). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Kuzmanovic, M.; Savic, G. Avoiding the privacy paradox using preference-based segmentation: A conjoint analysis approach. Electronics 2020, 9, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.E.; Rao, V.R. Conjoint measurement-for quantifying judgmental data. Journal of Marketing research 1971, 8, 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Green, P.E.; Srinivasan, V. Conjoint analysis in consumer research: issues and outlook. Journal of consumer research 1978, 5, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.E.; Srinivasan, V. Conjoint analysis in marketing: new developments with implications for research and practice. Journal of marketing 1990, 54, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krathwohl, D.R. A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into practice 2002, 41, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Etten, B.; Smit, K. Learning material in compliance with the Revised National Curriculum Statement: a dilemma. Pythagoras 2005, 2005, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Ghahramanloo, A.; Abedi, M.; Shirdel, Y.; Moradi-Asl, E. Examining the Degree of Compliance of the Continuing Public Health Bachelor’s Curriculum with the Job Needs of Healthcare Networks. Journal of Health 2024, 15, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeli, S.; Esmaeili, A.; Mohammadi, Y.; Raeisoon, M. Investigating the Compliance of the Curriculum Content of the Psychiatric Department of Medicine (Externship and Internship) with the Future Job Needs from the Perspective of General Practitioners. Research in Medical Education 2021, 13, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, R.L.; Isleta, K.P.; Regala, J.D.; Bialba, D.M.R. Enhancing experiential science learning with virtual labs: A narrative account of merits, challenges, and implementation strategies. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 2024, 40, 3167–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilani, H.; Markov, I.V.; Francis, D.; Grigorenko, E.L. Screens and Preschools: The Bilingual English Language Learner Assessment as a Curriculum-Compliant Digital Application. Children 2024, 11, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Neto, J.P.; Sales, D.C.; Pinheiro, H.S.; Neto, B.O. Using modern pedagogical tools to improve learning in technological contents. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE). IEEE; 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Braojos, C.; Montejo-Gámez, J.; Marín-Jiménez, A.E.; Poza-Vilches, F. A review of educational innovation from a knowledge-building pedagogy perspective. The Future of Innovation and Technology in Education: Policies and Practices for Teaching and Learning Excellence 2018, pp. 41–54.

- Mishra, S. The world in the classroom: Using film as a pedagogical tool. Contemporary Education Dialogue 2018, 15, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Chen, P.H.; Wang, W.S.; Huang, Y.M.; Wu, T.T. Empowering ChatGPT with guidance mechanism in blended learning: Effect of self-regulated learning, higher-order thinking skills, and knowledge construction. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2024, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Fang, N. The effects of enhanced hands-on experimentation on correcting student misconceptions about work and energy in engineering mechanics. Research in science & technological education 2023, 41, 462–481. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, P.; Taylor, A.K. Reducing students’ misconceptions with refutational teaching: For long-term retention, comprehension matters. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology 2017, 3, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Fang, N. Student misconceptions about force and acceleration in physics and engineering mechanics education. International Journal of Engineering Education 2016, 32, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.L.; Kirby, L.A. Situational interest helps correct misconceptions: An investigation of conceptual change in university students. Instructional Science 2020, 48, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosapoor, M. New teachers’ awareness of mathematical misconceptions in elementary students and their solution provision capabilities. Education Research International 2023, 2023, 4475027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapenieks, J. User-friendly e-learning environment for educational action research. Procedia Computer Science 2013, 26, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, C. User-Friendly Digital Tools: Boosting Student Engagement and Creativity in Higher Education. European Public & Social Innovation Review 2025, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Song, H.D. Make e-learning effortless! Impact of a redesigned user interface on usability through the application of an affordance design approach. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 2015, 18, 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, M.; Singh, K.; Jahnke, I. Socio-technical-pedagogical usability of online courses for older adult learners. Interactive Learning Environments 2023, 31, 2855–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakic, S.; Softic, S.; Andriichenko, Y.; Turcin, I.; Markoski, B.; Leoste, J. Usability Platform Test: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Educational Technology Applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning. Springer; 2024; pp. 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- Lefkos, I.; Mitsiaki, M. Users’ preferences for pedagogical e-content: A utility/usability survey on the Greek illustrated science dictionary for school. Research on E-Learning and ICT in education: Technological, pedagogical and instructional perspectives 2021, pp. 197–217.

- Balanyà Rebollo, J.; De Oliveira, J.M. Teachers’ evaluation of the usability of a self-assessment tool for mobile learning integration in the classroom. Education Sciences 2024, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusharraf, A.I. An Investigation of University Students’ Perceptions of Learning Management Systems: Insights for Enhancing Usability and Engagement. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchima-Marin, C.; Murillo, J.; Salvador-Acosta, L.; Acosta-Vargas, P. Integration of Technological Tools in Teaching Statistics: Innovations in Educational Technology for Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP). The Journal of the Operational Research Society 1980, 41, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.L. Multiple attributes decision making. Methods and applications 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, B. Classement et choix en présence de points de vue multiples. Revue française d’informatique et de recherche opérationnelle 1968, 2, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, J.R.; Greco, S.; Roy, B.; Słowiński, R. ELECTRE methods: Main features and recent developments. Handbook of multicriteria analysis 2010, pp. 51–89.

- Roy, B.; Bertier, P. La méthode ELECTRE II. Technical report, METRA International, 1973. Document de travail.

- Mousseau, V.; Slowinski, R.; Zielniewicz, P. ELECTRE TRI 2.0 a. methodological guide and user’s manual. Document du LAMSADE 1999, 111, 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Brans, J.P.; Vincke, P. Note—A Preference Ranking Organisation Method: (The PROMETHEE Method for Multiple Criteria Decision-Making). Management science 1985, 31, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, J.P.; Vincke, P.; Mareschal, B. How to select and how to rank projects: The PROMETHEE method. European journal of operational research 1986, 24, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, J.; Greco, S.; Ehrogott, M.; Brans, J.P.; Mareschal, B. PROMETHEE methods. Multiple criteria decision analysis: state of the art surveys 2005, pp. 163–186.

- Greco, S.; Ehrgott, M.; Figueira, J. ELECTRE methods. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys, Springer, New York, NY 2016, pp. 155–185.

- Maystre, L.Y.; Pictet, J.; Simos, J. Méthodes multicritères ELECTRE: description, conseils pratiques et cas d’application à la gestion environnementale; Vol. 8, EPFL Press, 1994.

- Roy, B. The outranking approach and the foundations of ELECTRE methods. Theory and Decision 1991, 31, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadian, M.; Kazemzadeh, R.B.; Albadvi, A.; Aghdasi, M. PROMETHEE: A comprehensive literature review on methodologies and applications. European journal of Operational research 2010, 200, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, J.P.; Mareschal, B.; Figueira, J.; Greco, S.; et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis: state of the art surveys. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science 2005, 78, 163–186. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).