Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.0.0.1. Contributions of this paper include:

- The design of a novel two-factor authentication protocol for IoD environments (Bio-2FA-IoD) that integrates biometrics as a primary operator verification factor, managed through a trusted Operator’s Device. This approach is inspired by the need for strong, user-bound authentication that is resilient to observational attacks.

- A formal security analysis of the proposed protocol using Burrows-Abadi-Needham (BAN) logic [3] to rigorously verify the achievement of mutual authentication and the secure establishment of shared beliefs regarding key parameters between communicating entities.

- A formal proof of security for the derived session key within the Bellare-Pointcheval-Rogaway (BPR) model [4] for Authenticated Key Exchange (AKE), demonstrating the protocol’s resilience against a wide range of active adversarial attacks.

- A comprehensive performance evaluation, comparing Bio-2FA-IoD with several contemporary IoD authentication protocols in terms of computational costs, communication overhead, and qualitative energy efficiency, thereby highlighting its suitability for resource-constrained IoD deployments.

2. Related Work

3. Preliminaries

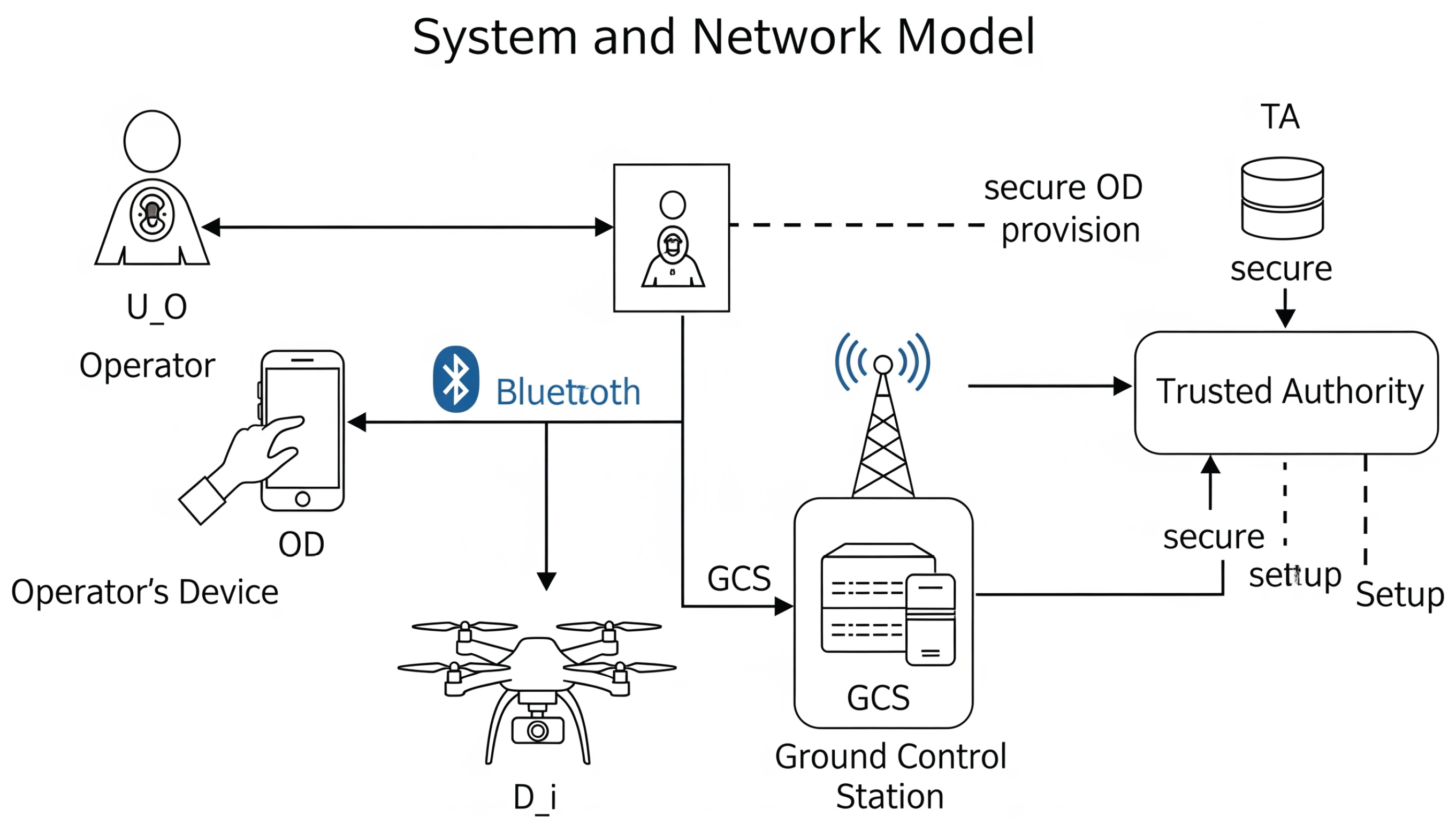

3.1. System and Network Model for IoD

- Operator (): The legitimate human user who initiates control commands or data requests for a drone. The operator’s identity is primarily verified through biometric means.

- Operator’s Device (OD): A trusted personal device (e.g., smartphone, dedicated handheld controller, tablet) belonging to the operator. It is equipped with, or can interface with, a biometric sensor. The OD is responsible for capturing biometric data, performing initial processing (e.g., feature extraction, fuzzy key generation), securely storing operator-specific credentials derived during registration, and executing the client-side authentication logic. This device is analogous to the smartphone in Khedr’s visual authentication protocol [1].

- Drone (): The Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. In the context of operator authentication to the GCS, the drone () primarily functions as a mobile platform that facilitates communication between the OD and the GCS. While drones possess their own identities and security mechanisms for flight control and drone-to-drone communication (which are outside the scope of this specific operator authentication protocol), their role here is to securely forward authentication messages between the OD and the GCS. Drones typically operate within specific flight zones and are managed by a GCS [8]. Drone technology integrates various components like communication modules (e.g., for FANETs [7,24]), sensors, and actuators, making them versatile but also complex systems to secure.

- Ground Control Station (GCS): A server entity, often part of a larger ground infrastructure or cloud backend. The GCS is responsible for receiving authentication requests from operators (via OD/Drone), verifying operator credentials, managing drone operations, and logging relevant activities. It is analogous to the "Server" in Khedr’s protocol [1] and the "Control Server (CS)" or "Ground Station Server (GSS)" in other IoD literature [8,10,19]. The GCS is assumed to have significantly more computational and storage resources than drones or ODs. It often connects to a data processing center.

- Trusted Authority (TA): A fully trusted, offline or highly secured entity responsible for the initial system setup and registration of all legitimate participants: operators (and their biometric data), ODs (by issuing initial secrets during operator registration), and GCSs. The TA manages master keys, identities, and ensures the integrity of the registration process [8,22]. It does not participate in every authentication session but establishes the root of trust.

3.2. Threat Model

- Full Control over Public Communication Channels: can eavesdrop on, intercept, delete, modify, inject, and replay any messages transmitted over insecure wireless links (e.g., -GCS, and potentially OD- if the local link is not perfectly secured).

- Impersonation Attempts: can try to impersonate any legitimate entity (, OD, , GCS) by replaying old messages or attempting to construct valid-looking new messages using any information gathered.

- Malicious Node Participation: can be a registered but compromised entity (e.g., a captured drone whose limited credentials might be extracted, or a compromised OD). The TA is assumed to be incorruptible.

- Drone Capture and Physical Attacks: Drones are vulnerable to physical capture, especially if operating in unattended or hostile environments. Upon capture, may perform physical attacks, side-channel attacks, or power analysis to extract any sensitive data stored on the drone’s hardware [6,9,19]. The protocol design aims to minimize the impact of such a compromise by limiting the sensitive data stored directly on the drone for operator authentication.

- Operator Device Attacks: While the OD is trusted by the operator, it can be subject to attacks if it relies on traditional password/PIN entry as a fallback or secondary factor (e.g., keylogging, shoulder-surfing) [1]. The use of biometrics as the primary factor mitigates this, and mechanisms like Khedr’s SVOSK [1] can further protect any manual input on the OD. Stolen ODs are a threat if biometric authentication can be bypassed or stored encrypted secrets are weak.

- Server-Side Database Attacks (GCS/TA Verification Data): might attempt to compromise the GCS or TA databases to obtain stored verification data (e.g., , , ). The protocol should ensure that such a breach does not directly reveal primary secrets like or the operator’s biometric template [26].

- Biometric System Attacks: may attempt to spoof the biometric sensor on the OD with a fake biometric sample (presentation attack) or attack the fuzzy extractor mechanism (e.g., by analyzing helper data ). The inherent security of the biometric sensor (e.g., liveness detection) and the properties of the fuzzy extractor are critical assumptions.

3.3. Security Requirements for Bio-2FA-IoD

- Mutual Authentication: All communicating IoD entities (e.g., operator via OD, and GCS) must verify each other’s identity before any sensitive payload exchanges or command execution can occur. This is a fundamental requirement to prevent unauthorized access and ensure that all parties are legitimate.

- Keylogging and Shoulder-Surfing Resistance: The protocol should protect operator credentials (like passwords or PINs, if used as a secondary factor to biometrics) from being captured by keyloggers on potentially compromised GCS terminals or observed by nearby attackers during input on the Operator’s Device (OD) [1].

- Replay Attack Resistance: Old authentication messages intercepted by an adversary must not be successfully replayed to gain unauthorized access or disrupt operations. This is often achieved using fresh nonces or timestamps [7].

- Impersonation Attack Resistance: An adversary should not be able to successfully impersonate a legitimate operator, OD, drone, or GCS. This includes user impersonation, drone impersonation, and GSS/server impersonation [8].

- Drone Capture Resilience: Given that drones may be deployed in unattended or hostile locations, they are susceptible to physical capture. The compromise of a single drone (and any secrets stored on it) should not compromise the operator’s long-term credentials, the security of other drones, or past/future session keys for other entities. Protocols should be designed to minimize sensitive data stored on the drone or ensure such data is heavily protected [6,9].

- Session Key Agreement and Security: Upon successful mutual authentication, the communicating parties (OD and GCS) should agree upon a secure session key ( in our context, primarily used for OTAC) to encrypt critical parts of their authentication exchange. This key must be protected from disclosure and should be unique to each session.

- Confidentiality: Sensitive data exchanged during the authentication process (e.g., ) and subsequent communications (if applicable) must be kept confidential from eavesdroppers.

- Integrity: The protocol must provide means to ensure that messages exchanged between entities are not tampered with or altered by an adversary during transit.

- Anonymity and Untraceability: Ideally, the real identities and locations of IoD entities (especially users and drones) should remain unknown to adversaries even if they can eavesdrop on exchanged messages. Attackers should not be able to trace or link communication sessions to specific users or drones over time [6,8,9].

-

Forward and Backward Secrecy:

- -

- Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS): Compromise of long-term secret keys (e.g., or ) should not compromise the confidentiality of past session keys ().

- -

- Perfect Backward Secrecy (PBS): Compromise of long-term secret keys should not compromise the confidentiality of future session keys derived after the compromise. The LAPEC protocol [18], for example, specifically aims for backward secrecy.

- Resistance to Specific IoD Attacks: The protocol should withstand attacks common to wireless and drone environments, such as: Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks, Denial of Service (DoS) attacks at the protocol level, privileged insider attacks [1,7], stolen verifier attacks [26], Ephemeral Secret Leakage (ESL) attacks, and physical/side-channel attacks.

- Scalability: The authentication mechanism should be able to support a potentially large number of drones and users without significant performance degradation or unmanageable key distribution overhead.

- Flexibility and Usability: The protocol should be adaptable to various IoD operational scenarios and be user-friendly for the operator during the authentication process. This includes considerations for password/PIN changes and device revocation.

- Dynamic Operations Support: The protocol should ideally support dynamic drone addition to the network and handle drone revocation or temporary disconnections and re-authentication seamlessly. Handover authentication [9] is also critical.

3.4. Cryptographic Primitives

3.4.1. Hash Functions

- Pre-image Resistance (One-wayness): Given a hash value y, it is computationally infeasible to find any input x such that .

- Second Pre-image Resistance (Weak Collision Resistance): Given an input x, it is computationally infeasible to find a different input such that .

- Collision Resistance (Strong Collision Resistance): It is computationally infeasible to find any two distinct inputs x and such that .

3.4.2. Symmetric Key Cryptography

- Encryption: , where M is the plaintext and C is the ciphertext.

- Decryption: .

3.4.3. Key Derivation Functions (KDFs)

3.5. Biometrics and Fuzzy Extractor

- Generation (): During the enrollment phase, this probabilistic algorithm takes an initial high-quality biometric sample as input. It outputs a secret cryptographic key (which should be close to uniformly random if has sufficient min-entropy) and public helper data . Schematically: . The helper data is stored publicly and is used during the key reproduction phase. It is crucial that does not reveal significant information about either or .

- Reproduction (): During an authentication attempt, this deterministic algorithm takes a fresh (potentially noisy) biometric sample from the user and the stored public helper data as input. It attempts to reproduce the original cryptographic key . Schematically: . The reproduction is successful if the Hamming distance (or another suitable metric) between the enrollment template and the current sample is within a predefined error tolerance threshold , i.e., .

3.6. Formal Security Models

3.6.1. BAN Logic

- Beliefs: (Principal P believes statement X).

- Sees: (P sees/receives message X).

- Once Said: (P once said X).

- Freshness: (Formula X is fresh, e.g., contains a fresh nonce or timestamp).

- Shared Secret Key: (P and Q share a secret key K).

- Jurisdiction: (P has jurisdiction over statement X).

- Message Meaning Rule (for shared keys): If and , then .

- Nonce Verification Rule: If and , then .

- Jurisdiction Rule: If and , then .

3.6.2. BPR Model (Bellare-Pointcheval-Rogaway)

- Participants (Oracles): Legitimate protocol participants ( via OD, GCS in our case) are modeled as oracles. An oracle represents instance s of principal U engaging in a protocol session.

-

Adversary (): A probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) adversary interacts with these oracles. has full control over the communication network (as per Dolev-Yao [5]). Its capabilities are modeled through a set of allowed oracle queries. Based on similar models in [6] and the original BPR model, common queries include:

- -

- ‘Send()’: sends message M to instance and receives the protocol-defined response.

- -

- ‘Execute()’: eavesdrops on an honest execution of the protocol.

- -

- ‘Reveal()’: obtains the session key computed by instance .

- -

- ‘Corrupt(U)’: obtains all long-term secret keys of principal U.

- -

- ‘Hash(M)’: queries the random oracle for the hash function or KDF.

- -

- ‘FuzzyExtractor(Gen/Rec, data)’: can query fuzzy extractor oracles.

- -

- ‘Test()’: Queried once on a “fresh" instance. The oracle flips a secret random bit b. If , it returns the actual session key; if , it returns a random string.

- Freshness: An instance is "fresh" if its session key has not been trivially revealed.

- AKE Security Definition: An AKE protocol is secure if is negligible. Proofs usually proceed by game-hopping.

3.7. Notations

3.8. Assumptions of the Protocol

- Secure TA: The Trusted Authority (TA) is honest, secure, and will not be compromised. It correctly executes its role during the registration phase, and its long-term secrets remain confidential [1].

- Secure Initial Provisioning of OD: The transfer of initial secrets (, ) from the TA to the Operator’s Device (OD) during registration is conducted over a secure channel or within a physically secure environment.

- Operator’s Device (OD) Trustworthiness and Security: The OD is considered a trusted computing base for the operator. It is assumed to securely store its provisioned secrets (, , ) and protect them from malware or unauthorized local access, potentially using hardware-backed security features (e.g., secure element, TEE). The operator’s local password/PIN (if used) is entered onto the OD through a secure interface (e.g., SVOSK-like [1]).

-

Biometric System Reliability and Security:

- The biometric sensor on the OD is assumed to be resistant to common spoofing attacks (e.g., presentation attacks with fake biometric samples).

- The operator’s biometric trait possesses sufficient entropy for to be a strong cryptographic key.

- Cryptographic Primitive Idealness: The chosen cryptographic hash function (e.g., SHA-256) behaves as a random oracle (or at least meets standard security properties like collision resistance). The symmetric encryption scheme (e.g., AES-128) is IND-CPA secure. The Key Derivation Function (KDF) (e.g., PBKDF2) is a secure pseudorandom function.

- Secure Local OD-Drone Link (for relay): The communication link between the OD and the drone for relaying authentication messages and is assumed to be reasonably secure (e.g., encrypted Bluetooth, local Wi-Fi with WPA2/3) or its exposure is limited due to short range.

- Loosely Synchronized Clocks: The OD and the GCS maintain loosely synchronized clocks, allowing for effective timestamp-based replay attack detection within a predefined tolerance window [1].

- GCS Database Protection: While the protocol aims to mitigate the impact of a GCS database compromise (e.g., by not storing directly), standard security practices are assumed to be in place to protect the GCS and its database of ().

4. Proposed Bio-2FA-IoD Protocol

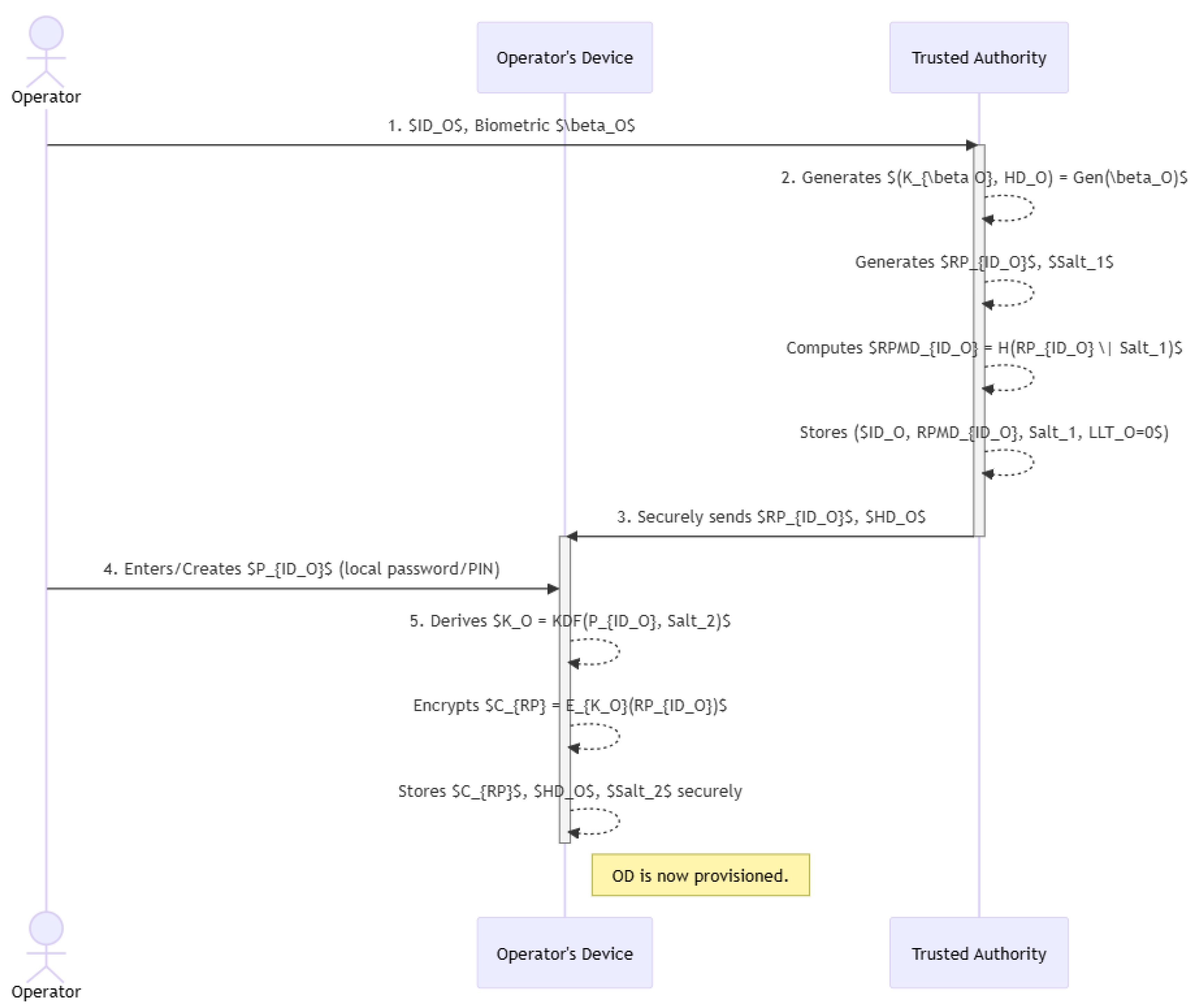

4.1. Registration Phase

- Operator Enrollment (): The operator initiates the registration process by submitting their chosen identity to the TA and enrolls their biometric trait using a trusted sensor interfaced with the TA’s system.

-

TA Operations (Credential Generation and Storage):

- The TA uses a fuzzy extractor to generate a stable biometric key and public helper data from the enrolled biometric : [2].

- TA generates a unique, high-entropy random password specifically for this operator, and a random salt .

- TA computes a hashed version of this random password: .

- TA securely stores the tuple in its database, where is the operator’s last login time, initialized to zero [1].

- OD Provisioning (): The TA securely transmits the generated random password and the helper data to the operator’s designated OD. This transfer must occur over a secure channel or through a secure physical provisioning process.

-

OD Final Setup (with assistance):

- The operator is prompted to create a local password or PIN, denoted as , on their OD.

- The OD derives a symmetric key , where is another random salt.

- The OD encrypts the received random password using : .

- The OD securely stores , , and .

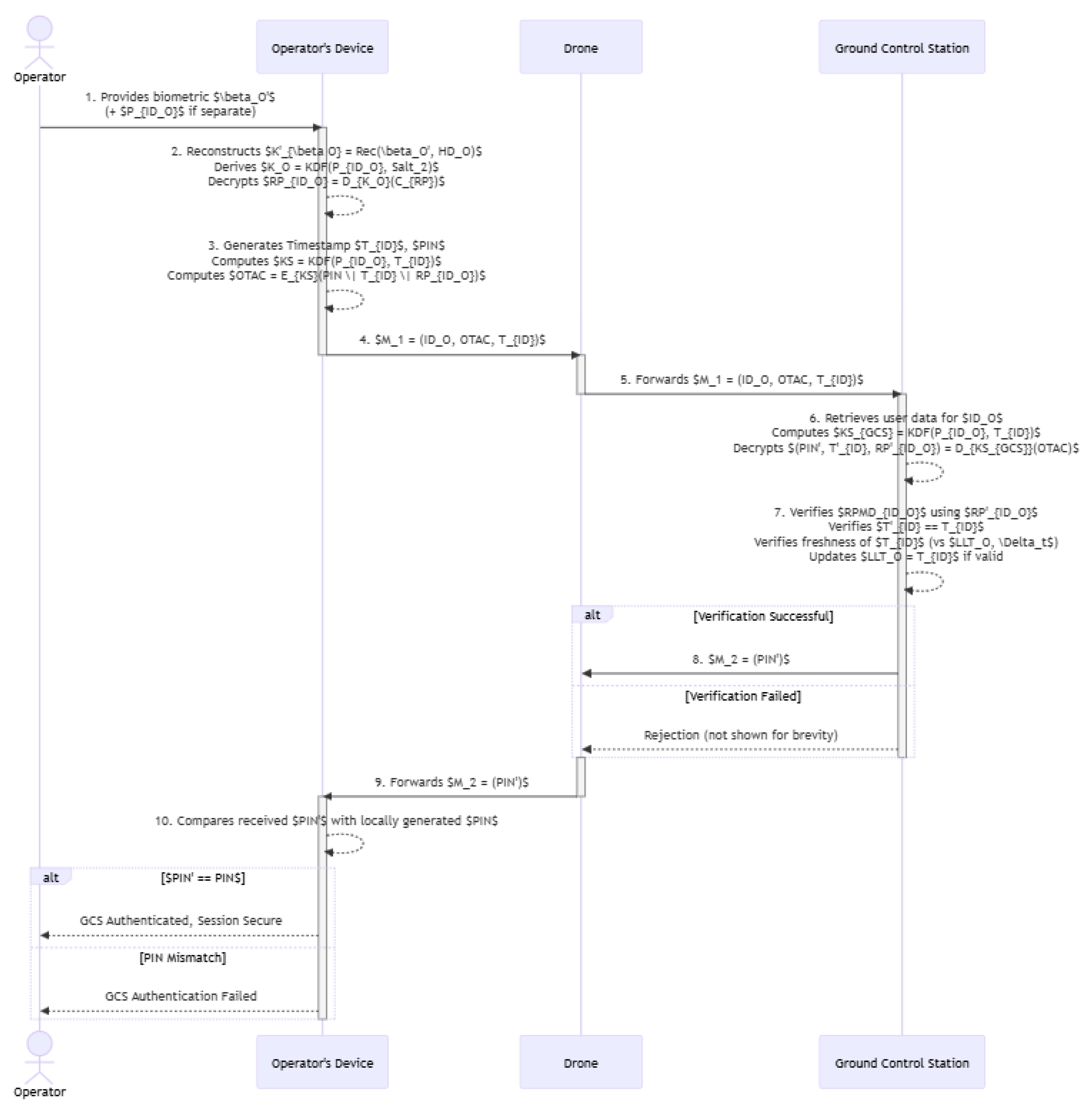

4.2. Authentication and Key Exchange Phase

-

Operator Biometric Input and Credential Activation ():

- The operator provides a fresh biometric sample to the biometric sensor on their OD.

- The OD uses the stored helper data to reconstruct the biometric key: [2]. If reconstruction fails, the process aborts.

- Operator enters . The OD regenerates .

- The OD decrypts . If decryption fails, the process aborts.

-

OD: OTAC Generation:

- The OD generates current timestamp and a fresh random nonce .

- OD generates ephemeral session key .

- OD computes .

-

Authentication Request ():

- OD sends to Drone .

- Drone forwards to the GCS.

-

GCS: Verification Process:

- Upon receiving , GCS retrieves for .

- GCS computes .

- Decrypts .

- Verifies .

- Verifies .

- Verifies and .

-

Mutual Authentication Response ():

- If all checks pass, GCS updates , sends to .

- Drone forwards to the OD.

-

OD: Final Verification (Mutual Authentication):

- OD receives containing .

- OD compares with its original . If match, GCS is authenticated.

5. Security Analysis

5.1. Informal Security Analysis

- Mutual Authentication: Achieved. The OD (for ) authenticates to GCS by proving knowledge of and (via OTAC). GCS authenticates to OD by returning the correct from OTAC. This meets requirement 1. This is similar to the mechanism in Khedr [1] but adapted for biometrics.

- Keylogging and Shoulder-Surfing Resistance: Primary authentication is biometric. Any PIN entry on the OD can use an SVOSK-like interface . This meets requirement 2.

- Replay Attack Resistance: Timestamps and checks at GCS, along with being part of the encrypted OTAC, prevent replay of messages . This meets requirement 3.

-

Impersonation Attack Resistance:

- -

- Operator/OD Impersonation: Requires (or ), , and to form a valid OTAC. Infeasible without these secrets.

- -

- GCS Impersonation: Requires deriving from OTAC, which needs . Impossible for an adversary without and current .

- Drone Capture Resilience: Secrets are on the OD, not the drone . Drone capture does not compromise operator credentials for this protocol. This meets requirement 5, a critical aspect discussed in [6].

- Session Key () Security: . Security depends on (biometrically protected) and fresh . Meets requirement 6.

- Confidentiality of OTAC Payload: are encrypted within OTAC using . Meets requirement 7.

- Integrity of Authentication Messages: Implicit integrity via successful decryption and verification of OTAC contents ( vs , consistency) and return. Modification leads to verification failure. Meets requirement 8.

- Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS): depends on long-term . PFS is not achieved for . This is a limitation regarding requirement 10.

5.2. BAN Logic Analysis

Initial Assumptions (Axioms):

- A1.

- .

- A2.

- .

- A3.

- .

- A4.

- .

- A5.

- , .

- A6.

- .

- A7.

- .

- A8.

- .

Idealized Protocol Messages:

- M1.

- M2.

Analysis Sketch:

- OD sends . OD believes it shares with GCS (via TA) to compute .

- GCS receives . Computes . Using Message Meaning Rule on (where ), .

- GCS believes is fresh (after checks), hence . By Nonce Verification, . GCS verifies from X against stored .

- OD receives . OD uses its . By Message Meaning, .

- Since and matches original , by Nonce Verification, . This confirms GCS processed X correctly.

- Both OD and GCS can now believe is a good shared key: and .

5.3. BPR Model Analysis

Oracle Setup and Adversarial Capabilities:

Proof Sketch by Game Hopping:

- Game : Real AKE security game.

- Game (Random Oracles for Hash/KDF): H and are simulated as random oracles. , which is negligible for secure functions.

- Game (Fuzzy Extractor Simulation): The output of is indistinguishable from random if has sufficient min-entropy and leaks nothing, or if queries with an invalid . The advantage change is bounded by , the security of the fuzzy extractor against guessing from or predicting output without valid input [2,6]. .

- Game (Symmetric Cipher Indistinguishability): Ciphertexts produced by are replaced by random strings if is unknown to . If is known, the simulation is perfect. The difference is bounded by IND-CPA security of E, . .

- Game (Attacking via ‘Test’ query): Consider a ‘Test()‘ query for . If has not successfully executed ‘Corrupt()’ for prior to this session becoming complete (i.e., the session is “fresh”), then is unknown to . Since is a fresh, unique timestamp for each session, and is a random oracle, is computationally indistinguishable from a random string to . The adversary might try to forge to elicit a response or try to guess from (if GCS is corrupted). and . These layers make guessing hard. If queries “Test” on a fresh session where it does not know , the game simulator directly provides a truly random string. The only way distinguishes this game from is by successfully guessing or breaking the KDF (covered in ). The probability of guessing from available information (without corruption) is . .

- Game (Final Game): The output of the ‘Test’ query is always a truly random string for fresh instances. Thus, , so .

6. Performance Evaluation

6.1. Computational Cost Analysis

- (SHA-256 hash): ms (Nyangaresi et al. [6])

- (Fuzzy Extractor - Rec): ms (Nyangaresi et al. [6])

- (AES-128 Enc/Dec): ms (Nyangaresi et al. [6])

- (PBKDF2-SHA256, simplified for derivation): ms (estimation, actual PBKDF2 can be higher due to iterations but here it’s used for key derivation not password stretching from low-entropy input).

-

Operator’s Device (OD):

- (a)

- Biometric Key Reconstruction (): ms

- (b)

- Local Key Regeneration (): ms

- (c)

- Decryption (): ms

- (d)

- Session Key Generation (): ms

- (e)

- OTAC Encryption (): ms

Total OD Cost: ms. -

Ground Control Station (GCS):

- (a)

- Session Key Generation (): ms

- (b)

- OTAC Decryption (): ms

- (c)

- Calculation (): ms

Total GCS Cost: ms.

6.2. Communication Cost Analysis

- Message

- Message

- : e.g., 128 bits (16 bytes)

- (Timestamp): e.g., 32 bits (4 bytes)

- (Nonce): e.g., 128 bits (16 bytes)

- (Random Password, assumed to be key-like): e.g., 160 bits (20 bytes)

- Plaintext for OTAC: bits (40 bytes).

- OTAC (Ciphertext using AES-128, e.g., CBC mode with IV and padding): Size will be multiple of 128 bits. For 40 bytes plaintext, it might be 3 blocks = bits (48 bytes) including IV or padding.

- Size of : bits.

- Size of : bits.

6.3. Energy Consumption Analysis

6.4. Security and Functionality Features Comparison

7. Conclusion

References

- Khedr, W. I. (2018). Improved keylogging and shoulder-surfing resistant visual two-factor authentication protocol. Journal of Information Security and Applications, 39, 41-57.

- Dodis, Y., Reyzin, L., & Smith, A. (2004). Fuzzy extractors: How to generate strong keys from biometrics and other noisy data. In EUROCRYPT 2004 (LNCS 3027, pp. 523-540). Springer.

- Burrows, M., Abadi, M., & Needham, R. (1989). A Logic of Authentication. ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), 8(1), 18-36.

- Bellare, M., Pointcheval, D., & Rogaway, P. (2000). Authenticated Key Exchange Secure Against Dictionary Attacks. In Eurocrypt 2000 (LNCS 1807, pp. 139-155). Springer.

- Dolev, D., & Yao, A. (1983). On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 29(2), 198-208.

- Nyangaresi, V. O., Al-Joboury, I. M., Al-sharhanee, K. A., Najim, A. H., Abbas, A. H., & Hariz, H. M. (2024). A biometric and physically unclonable function-Based authentication protocol for payload exchanges in internet of drones. e-Prime - Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy, 7, 100471.

- Jan, S. U., Qayum, F., & Khan, H. U. (2021). Design and Analysis of Lightweight Authentication Protocol for Securing IoD. IEEE Access, 9, 69287-69306.

- Berini, A. D. E., Ferrag, M. A., Farou, B., & Seridi, H. (2023). HCALA: Hyperelliptic curve-based anonymous lightweight authentication scheme for Internet of Drones. Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 92, 101798.

- Khalid, H., Hashim, S. J., Hashim, F., Ahamed, S. M. S., Chaudhary, M. A., Altarturi, H. H. M., & Saadoon, M. (2023). HOOPOE: High Performance and Efficient Anonymous Handover Authentication Protocol for Flying Out of Zone UAVs. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 72(8), 10906-10920.

- Akram, M. A., Ahmad, H., Mian, A. N., Jurcut, A. D., & Kumari, S. (2023). Blockchain-based privacy-preserving authentication protocol for UAV networks. Computer Networks, 224, 109638.

- Najafi, F., Kaveh, M., Mosavi, M. R., Brighente, A., & Conti, M. (2025). EPUF: An Entropy-Derived Latency-Based DRAM Physical Unclonable Function for Lightweight Authentication in Internet of Things. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 24(3), 2422-2436.

- Jan, S. U., & Khan, H. U. (2021). Identity and Aggregate Signature-Based Authentication Protocol for IoD Deployment Military Drone. IEEE Access, 9, 126038-126050.

- Hussain, S., Farooq, M., Alzahrani, B. A., Albeshri, A., Alsubhi, K., & Chaudhry, S. A. (2023). An Efficient and Reliable User Access Protocol for Internet of Drones. IEEE Access, 11, 59689-59700.

- Hasson, M., Yassin, A. A., Yassin, A. J., Rashid, A. M., Yaseen, A. A., & Alasadi, H. (2021). Password authentication scheme based on smart card and QR code. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 23(1), 140-149.

- Khan, A. A., Kumar, V., & Ahmad, M. (2022). An elliptic curve cryptography based mutual authentication scheme for smart grid communications using biometric approach. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, 34(1), 698-705.

- Akram, J., Akram, A., Jhaveri, R. H., Alazab, M., & Chi, H. (2022). BC-IoDT: Blockchain-based Framework for Authentication in Internet of Drone Things. Proceedings of the ACM MobiCom Workshop on Drone Assisted Wireless Communications for 5G and Beyond (DroneCom ’22), ACM.

- Vangala, A., Agrawal, S., Das, A. K., Pal, S., Kumar, N., Lorenz, P., & Park, Y. (2024). Big Data-Enabled Authentication Framework for Offshore Maritime Communication Using Drones. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 73(7), 10196-10210.

- Zhang, S., Liu, Y., Han, Z., & Yang, Z. (2023). A Lightweight Authentication Protocol for UAVs Based on ECC Scheme. Drones, 7(5), 315.

- Wu, T., Guo, X., Chen, Y., Kumari, S., & Chen, C. (2022). Amassing the Security: An Enhanced Authentication Protocol for Drone Communications over 5G Networks. Drones, 6(1), 10.

- Zhang, N., Jiang, Q., Li, L., Ma, X., & Ma, J. (2021). An efficient three-factor remote user authentication protocol based on BPV-FourQ for internet of drones. Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications, 14, 3319-3332.

- Wu, T. Y., Wu, H., Kumari, S., & Chen, C. M. (2025). An enhanced three-factor based authentication and key agreement protocol using PUF in IoMT. Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications, 18, 83. (Note: Year is 2025, might be early access).

- El-Zawawy, M. A., Brighente, A., & Conti, M. (2023). Authenticating Drone-Assisted Internet of Vehicles Using Elliptic Curve Cryptography and Blockchain. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, 20(2), 1775-1789.

- Cabuk, U. C., Dalkilic, G., & Dagdeviren, O. (2021). CoMAD: Context-Aware Mutual Authentication Protocol for Drone Networks. IEEE Access, 9, 78400-78414.

- Gupta, A., Barthwal, A., Vardhan, H., Kakria, S., Kumar, S., & Parihar, A. S. (2023). Evolutionary study of distributed authentication protocols and its integration to UAV-assisted FANET. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 82, 42311-42330.

- Nikooghadam, M., Amintoosi, H., Islam, S. H., & Moghadam, M. F. (2021). A provably secure and lightweight authentication scheme for Internet of Drones for smart city surveillance. Journal of Systems Architecture, 115, 101955.

- Jafarian, I. (2023). Cryptanalysis of Nikooghadam et al.’s Lightweight Authentication Protocol for Internet of Drones. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.02512. arXiv:2311.02512. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.

- Fatima, S., Akram, M. A., Mian, A. N., Kumari, S., & Chen, C. M. (2024). On the Security of a Blockchain and PUF-Based Lightweight Authentication Protocol for Wireless Medical Sensor Networks. Wireless Personal Communications, 136, 1079-1106.

Short Biography of Authors

|

Hyunseok Kim Hyunseok Kimreceived the B.S. degree in the Department of Business Management from Korea Military Academy, Seoul, Korea in 2000, M.S. and Ph.D in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering from Korea University, Seoul, Korea in 2006 and 2009, respectively. He is currently an associate professor at the ICT Polytech Institute of Korea. His research interests include the areas of Formal Methods(Formal Specification, Formal Verification, Model Checking), IoD Authentication Design, Smart Card Privacy, M-Commerce Secure Transaction. |

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Drone Operator | |

| OD | Operator’s Device |

| i-th Drone | |

| GCS | Ground Control Station |

| TA | Trusted Authority |

| Identity of entity X | |

| Operator’s biometric data (enrollment) | |

| Operator’s fresh biometric data (verification) | |

| Biometric key derived from | |

| Helper data for biometric key reconstruction | |

| Operator’s password/PIN (local to OD) | |

| Symmetric key derived from and on OD | |

| Random Password for the operator, generated by TA | |

| encrypted with on OD | |

| Hash digest of and , stored at TA/GCS | |

| Random salt values | |

| Secure one-way hash function (e.g., SHA-256) | |

| Key Derivation Function (e.g., PBKDF2) | |

| Symmetric encryption with key K (e.g., AES-128) | |

| Symmetric decryption with key K (e.g., AES-128) | |

| Timestamp generated by OD | |

| Ephemeral session key for OTAC () | |

| GCS’s version of | |

| OTAC | One-Time Authentication Code |

| Random number generated by OD, part of OTAC | |

| Operator’s last login time, stored at TA/GCS | |

| Maximum allowable time difference for freshness | |

| ∥ | Concatenation operation |

| ⊕ | Bitwise XOR operation |

| Protocol | Total Est. Cost (ms) | Primary Cryptographic Primitives |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-2FA-IoD (Proposed) | 0.0411 | FE, KDF, AES, SHA-256 |

| Nyangaresi et al. (2024) [6] | 0.0388 | PUF, FE, Hash |

| Jan et al. (2021) [7] | 17.7939 | HMAC-SHA1, Hash, XOR |

| Berini et al. (HCALA, 2023) [8] | 3.3873 | HECC, Hash, AES |

| Khalid et al. (HOOPOE, 2023) [9] | 8.343 | AES, RSA, Hash, Signature |

| Akram et al. (2023) [10] | 0.44819 | ECC, Hash, Signature |

| Najafi et al. (EPUF-Auth, 2025) [11] | ≈0.016 | PUF (DRAM), Hash, XOR |

| Protocol | Messages | Total Est. Cost (bits) | Source for Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-2FA-IoD (Proposed) | 2 | 672 | Current Estimation |

| Nyangaresi et al. (2024) [6] | 6 | 2464 | Nyangaresi et al. |

| Jan et al. (2021) [7] | 4 | 3720 | Jan et al. |

| Berini et al. (HCALA, 2023) [8] | 3 | 1536 | Berini et al. |

| Khalid et al. (HOOPOE, 2023) [9] | 2 (D-GSS) | 1280 | Khalid et al. |

| Akram et al. (2023) [10] | 2 | 1152 | Akram et al. |

| Najafi et al. (EPUF-Auth, 2025) [11] | 2 | 1536 | Najafi et al. (192 Bytes) |

| Feature | Khedr [1] (Adapted) | Nyangaresi [6] | Jan [7] | HCALA [8] | HOOPOE [9] | Bio-2FA-IoD (Proposed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Authentication | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Keylogging Resist. (GCS) | Yes | Yes (Implied) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| Shoulder-Surf. Resist. | Yes | Yes (Biometric) | N/A | Yes (PIN on User) | N/A | Yes |

| User Anonymity | No | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes | Partial |

| Replay Attack Resist. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Impersonation Resist. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Drone Capture Resilience | N/A | Yes | Partial | Partial | Yes | Good |

| Forward Secrecy (PFS) | Limited | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Limited |

| Formal Verification | AVISPA (orig.) | RoR, AVISPA | ROM, ProVerif | ROM, AVISPA | RoR, ProVerif | BAN, BPR |

| Lightweight Nature | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate | Moderate | Yes |

| Biometric Integration | No (Visual 2FA) | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Three-Factor Auth. Potential | No (2FA) | Yes (Implicit) | No (2FA) | Yes (Implicit) | No | Yes (Bio, OD, PIN) |

| Handles Handover | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Blockchain Integration | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| PUF Usage | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).