Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

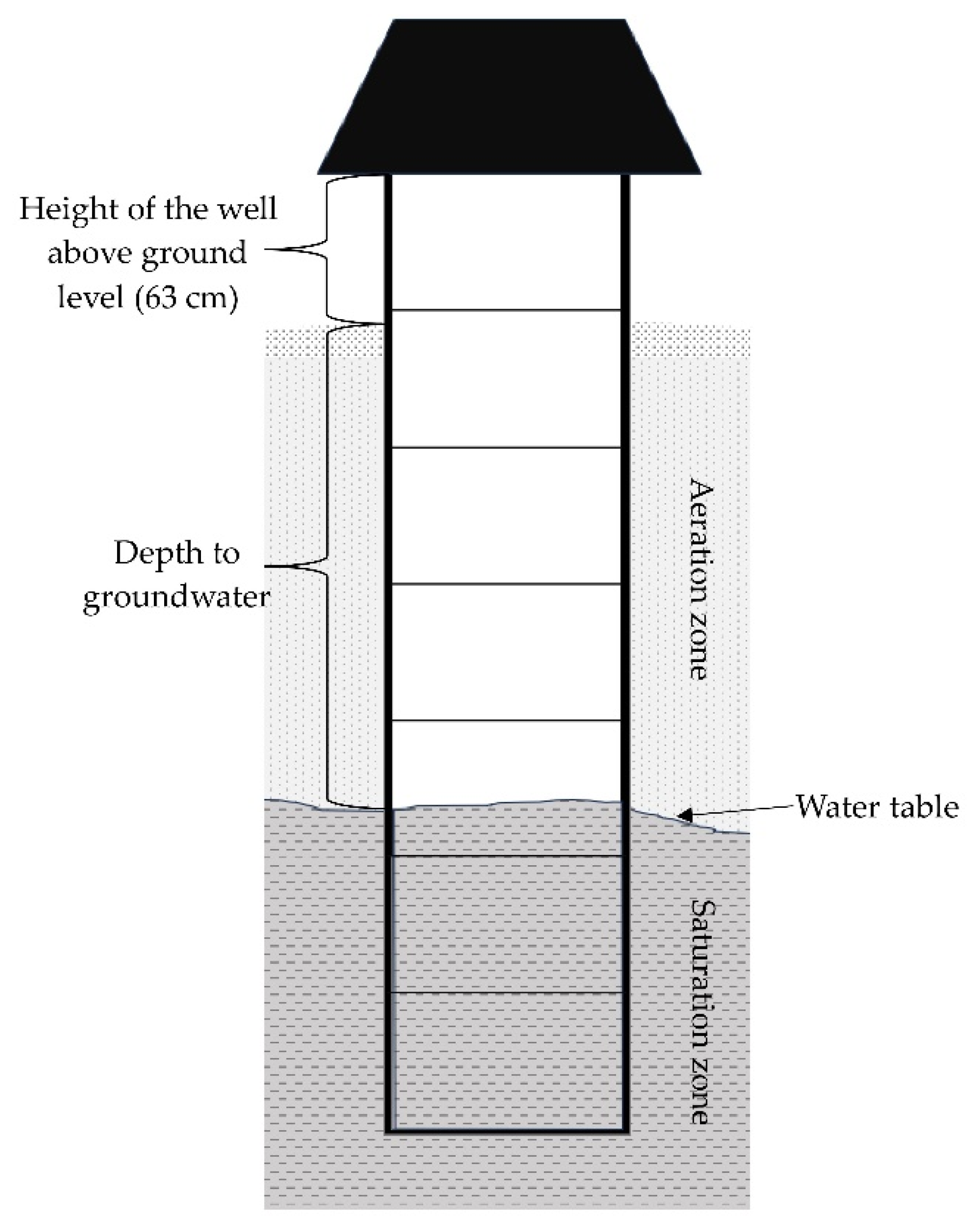

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

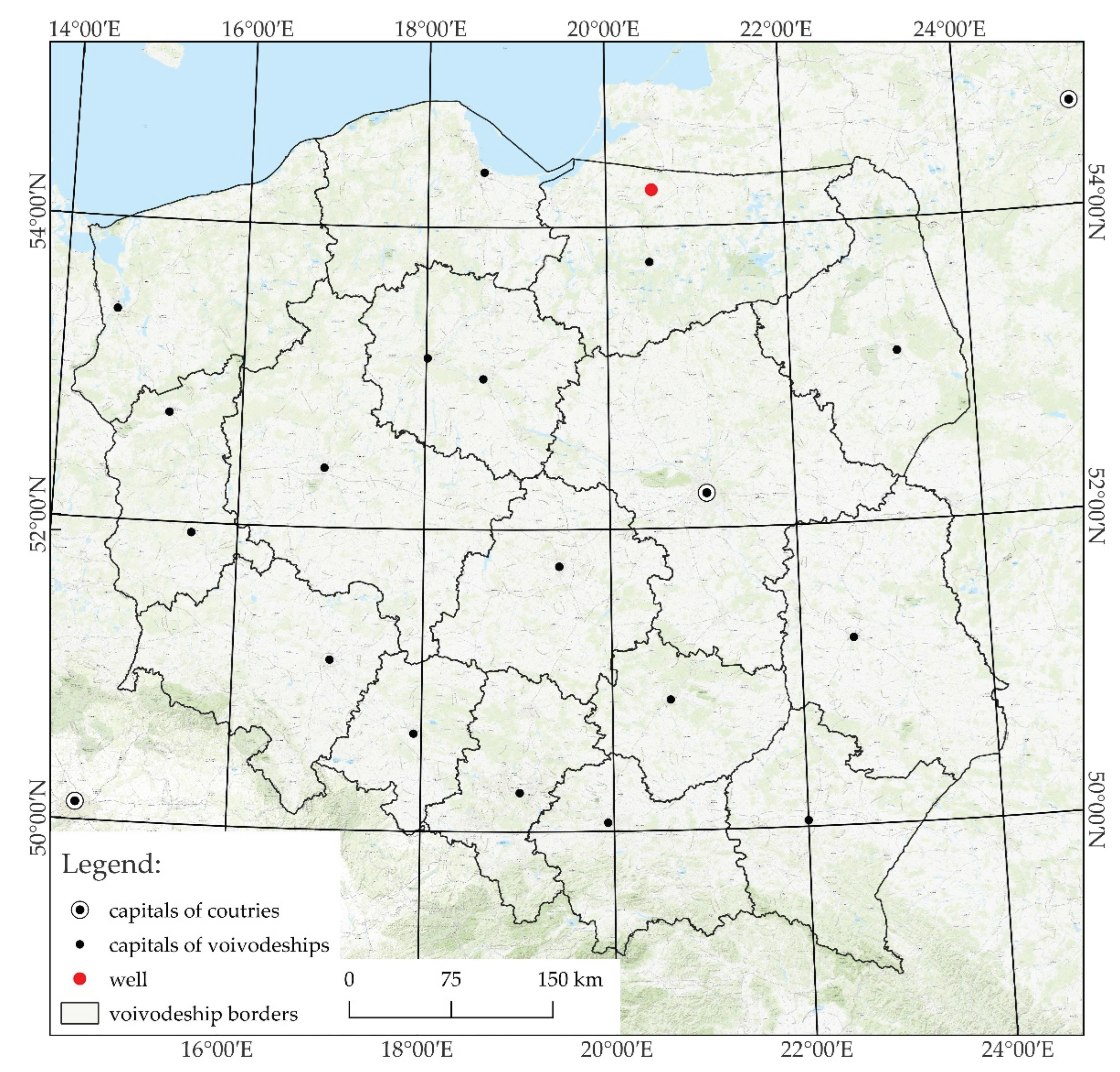

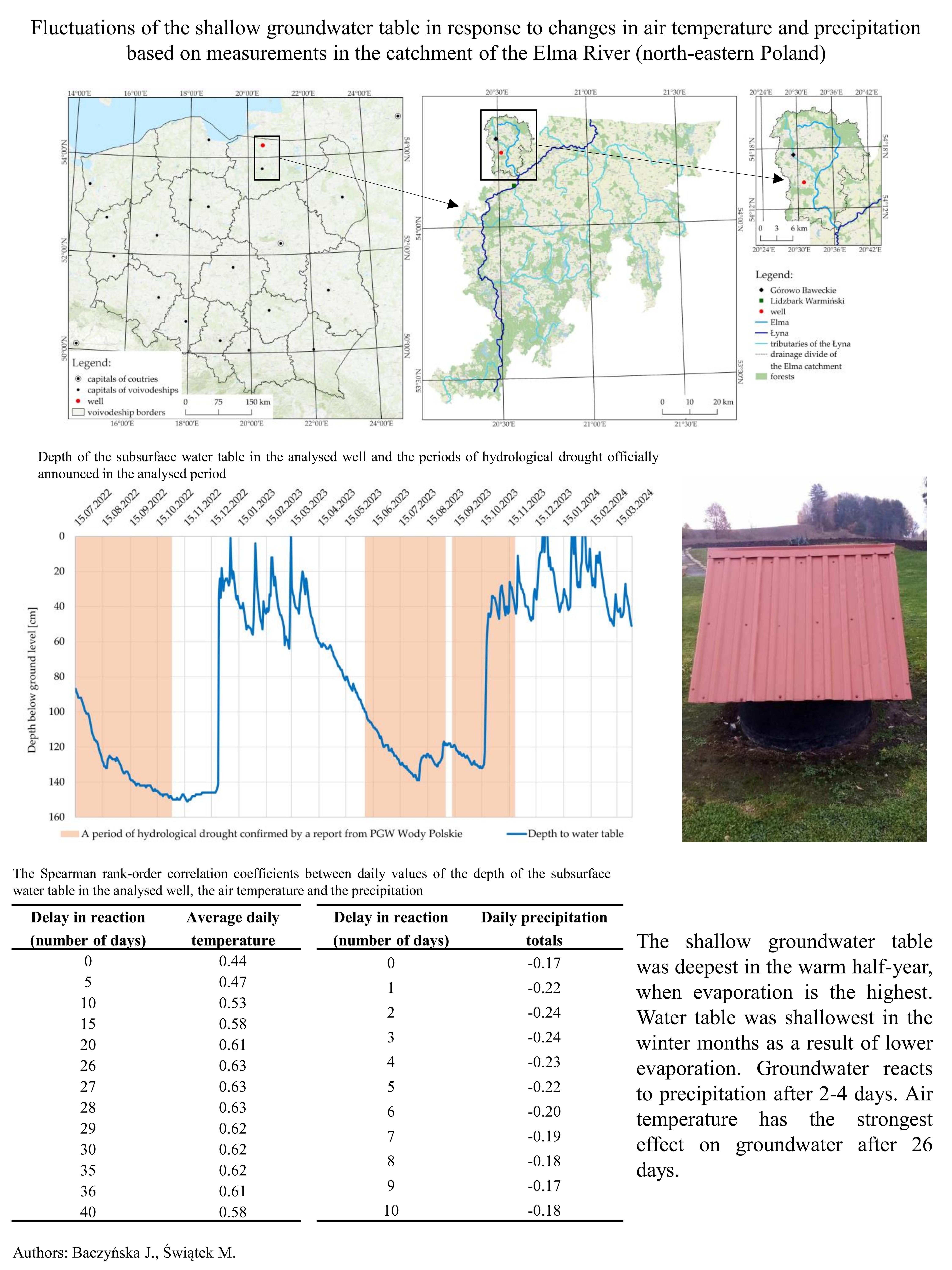

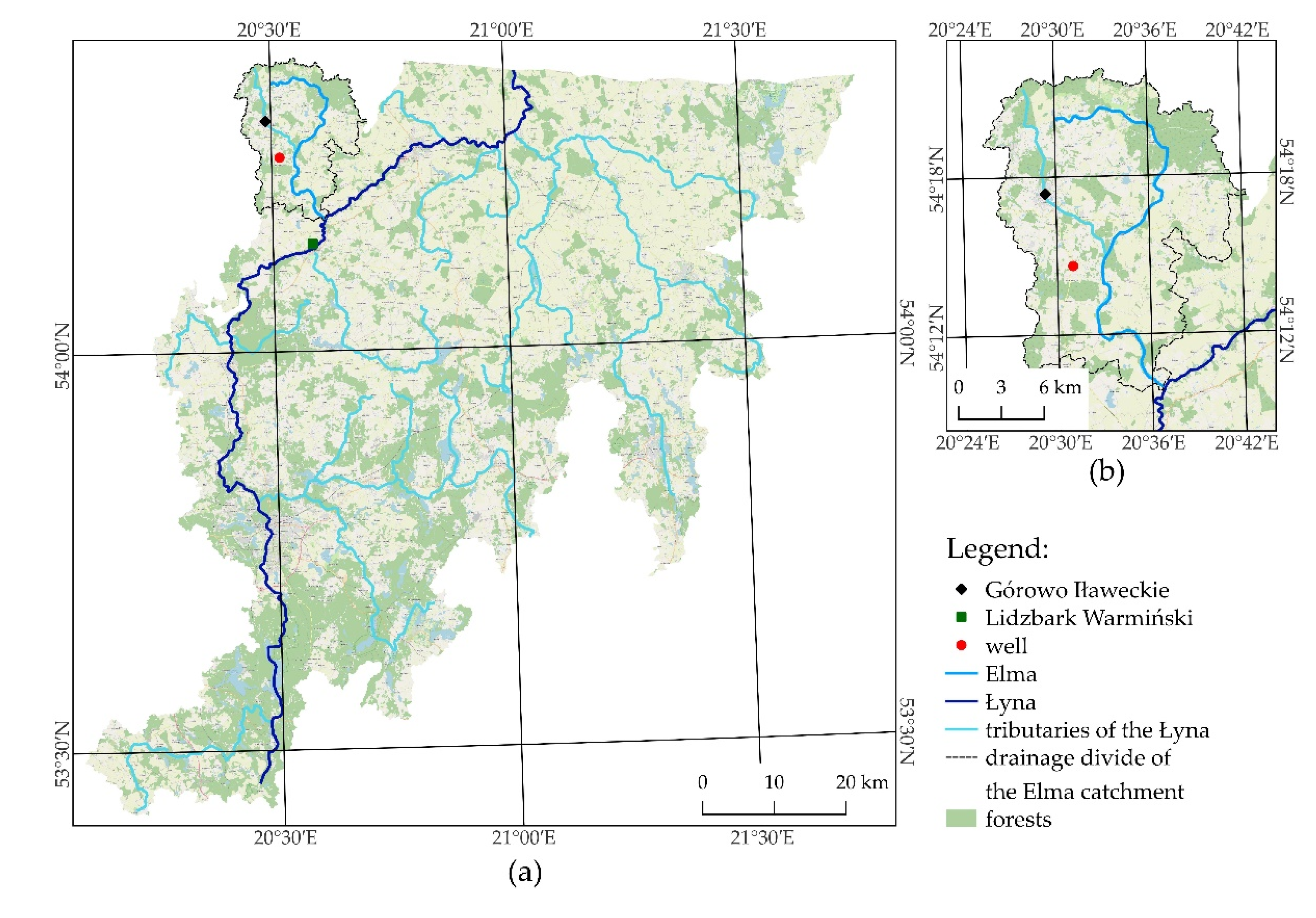

2. Research Area

3. Materials and Methods

- 0-0.2 – very weak correlation;

- 0.2-0.4 – weak correlation;

- 0.4-0.6 – moderate correlation;

- 0.6-0.8 – strong correlation;

- 0.8-1 – very strong correlation [43].

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Summary and Conclusions

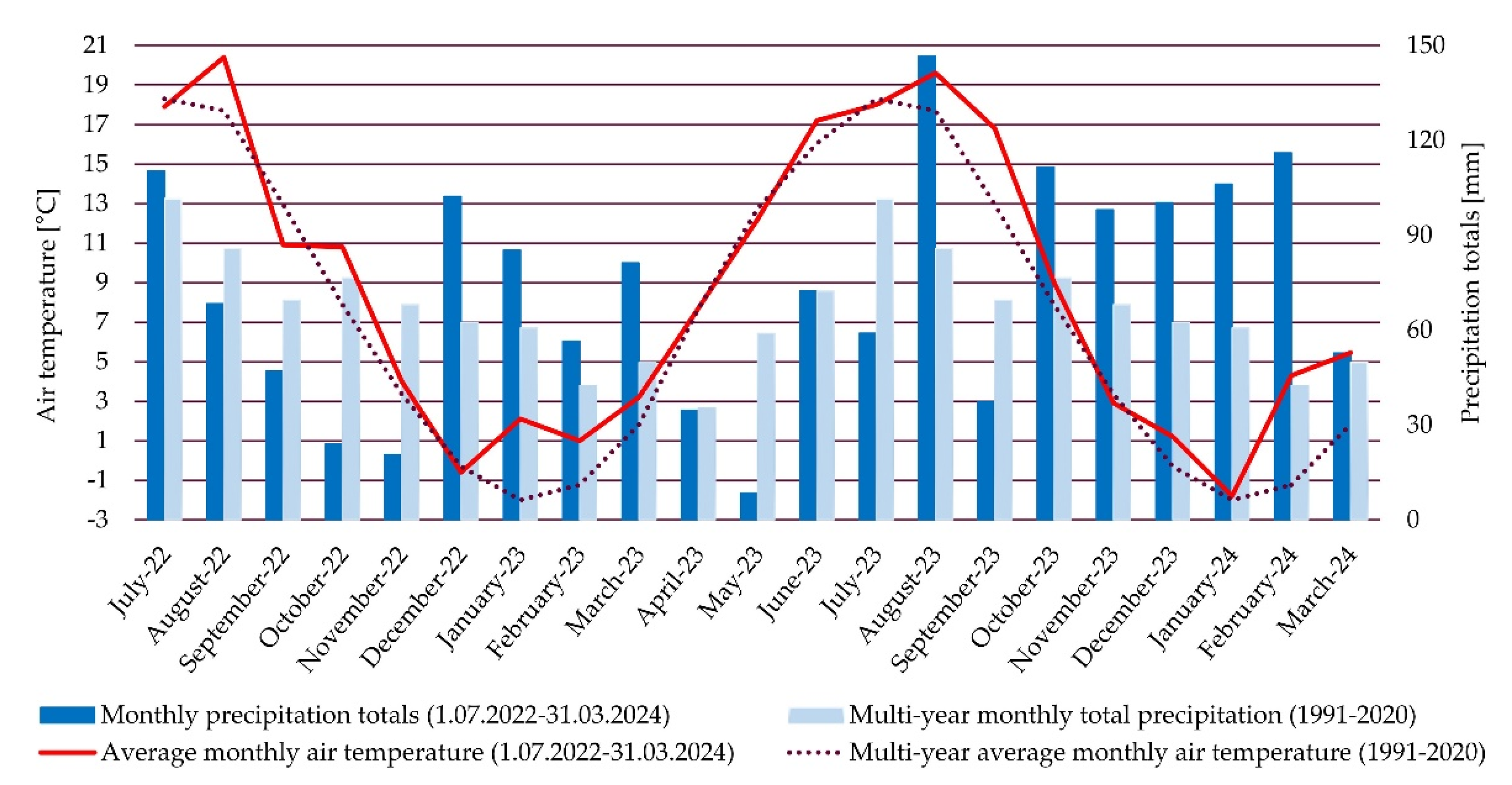

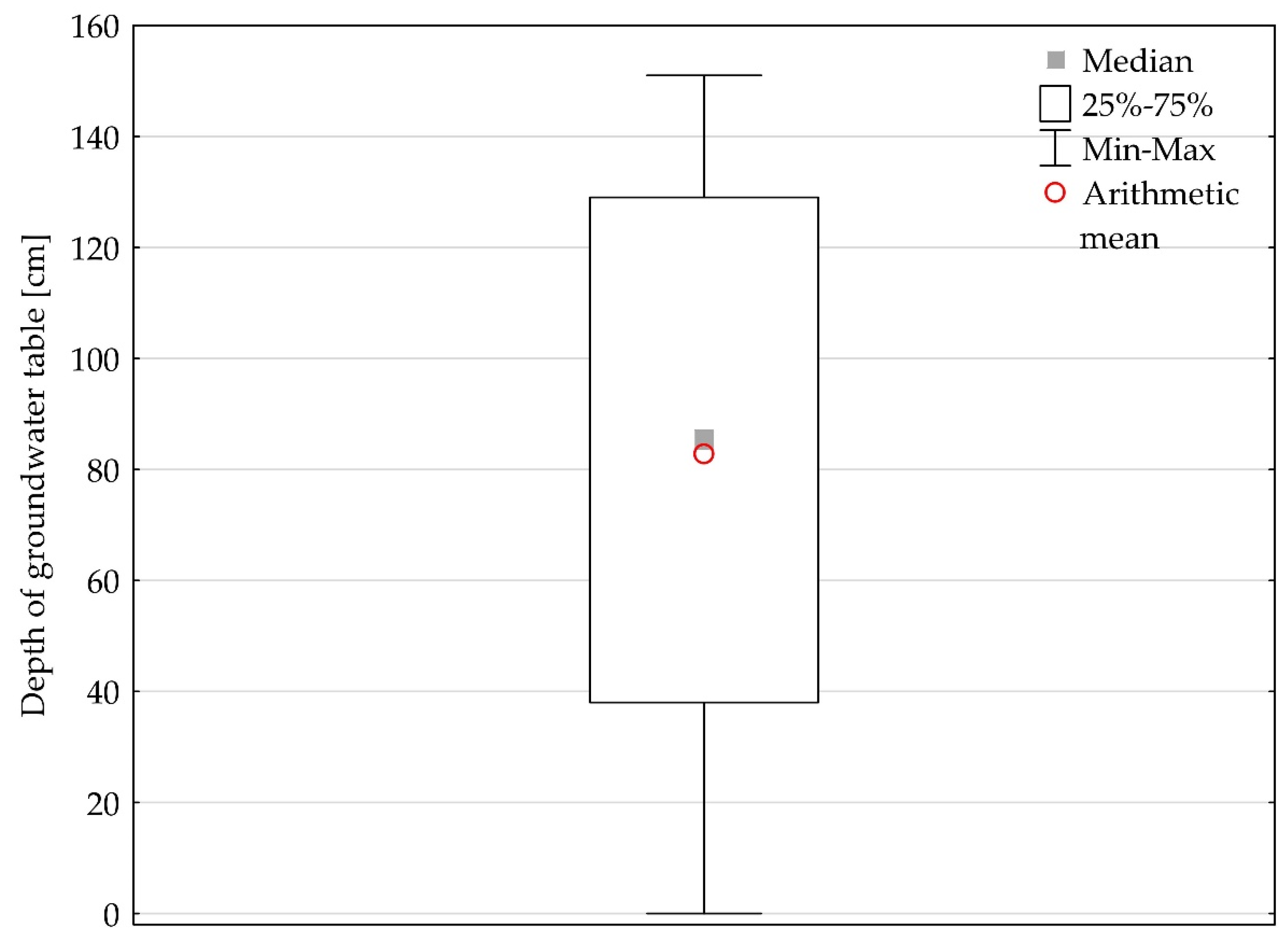

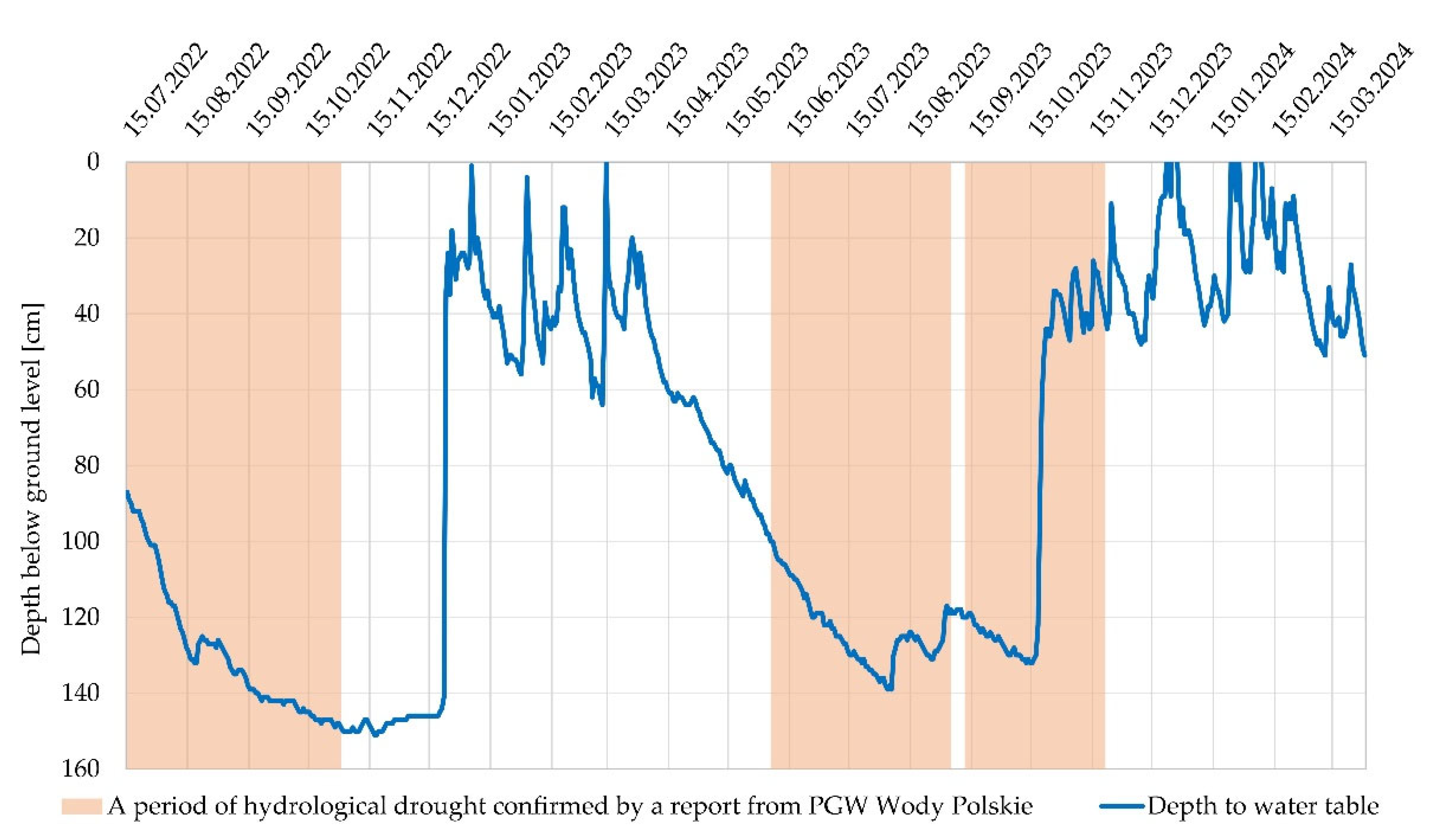

- The depth of the subsurface water table varied during the year. In warm months, the water table was deeper than in cold months ones. This was caused, first of all, by the intensive evaporation of water from the land surface. In the cold season, the water table was relatively high, then falling gradually with increases in the air temperature.

- Air temperature had a significant influence on the depth of the groundwater level. It determined, first of all, the intensity of water evaporation from the soil, which affects the water resources. This was noticeable in the warm seasons of the analysed period, when, as a result of high air temperature values, the groundwater table was situated at greater depths, even in spite of relatively high precipitation totals.

- The influence of precipitation was the most significant in the cold half-year, when the intensity of evaporation decreased. During those periods, precipitation can effectively supplement groundwater resources, which is proven by the relatively high level of the water table in the well in the winter and its noticeable rise after rainfall or rapid snowmelts. An example may be December 2022, when the subsurface water table rose by 117 cm in two days as a result of rapid snowmelt, and October 2023 when, after long rainfall, the subsurface water table increased by 88 cm within one week.

- In the warm season, however, only long-lasting rainfall could effectively supplement the subsurface water resources. Short, torrential rains had only a slight influence on groundwaters. This is proven by the event of 5 August 2024 when, in spite of intensive rainfall (46 mm in a day), the groundwater table increased by 14 cm and then started to drop again after a week.

- Air temperature had the strongest influence on shallow groundwaters after 26–35 days, and precipitation – after 2–3 days.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shevchenko, O.; Skorbun, A.; Osadchyi, V.; Osadcha, N.; Grebin, V.; Osypov, V. Cyclicities in the Regime of Groundwater and of Meteorological Factors in the Basin of the Southern Bug River. Water, 2022, 14, 2228. [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, M. Symptoms of climate change in Poland. In Geography for socjety, Kordel, Z., Josan, I., Wiskulski, T., Eds.; Editura Universitӑţii din Oradea: Oradea, Romania, 2015; pp. 94-112.

- Ustrnul, Z.; Wypych, A.; Czekierda, D. Air temperature change. In Climate change in Poland: past, present, future, Falarz, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 349-373. [CrossRef]

- Pierzgalski, E.; Boczoń, A.; Tyszka, J. Variability of precipitation and groundwater levels in Białowieża National Park. Kosmos 2002, 51(4), 415-425 (in Polish).

- Świątek, M.; Walczakiewicz, S. Changes in specific runoff in river catchments of Western Pomerania versus climate change. Geographia Polonica 2022, 95, 25-52. [CrossRef]

- Świątek, M. Changes in specific discharge in the lowland part of Poland in the years 1961–2021. Acta Geographica Lodziensia 2024, 115, 125-140 (in Polish). [CrossRef]

- 7. 6th IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I.; Huang, M.; Leitzell, K.; Lonnoy, E.; Matthews, J.B.R.; Maycock, T.K.; Waterfield, T.; Yelekçi, O.; Yu, R.; Zhou, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2023a; pp. 3−32. [CrossRef]

- Döll, P. Vulnerability to the impact of climate change on renewable groundwater resources: a global-scale assessment. Environmental Research Letters 2009, 4(3), 035006. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liesch, T.; Goldscheider, N. Impacts of climate change and human activities on global groundwater storage from 2003-2022. Research Square 2024. [CrossRef]

- 6th IPCC. Climate information relevant for Water Resources Management. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/factsheets/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Sectoral_Fact_Sheet_Water_Resources_Management.pdf (1 February 2025).

- Małecki, Z.J.; Gołębiak, P. Water resources of Poland and the world. Zeszyty Naukowe – Inżynieria Lądowa i Wodna w Kształtowaniu Środowiska 2012, 7, 50-56 (in Polish).

- Alfieri, L.; Burek, P.; Feyen, L.; Forzieri, G. Global warming increases the frequency of river floods in Europe. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 2247–2260. [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, P.; Musolff, A.; Kumar, R.; Hartmann, A.; Fleckenstein, J.H. Groundwater head responses to droughts across Germany. EGUsphere Preprint repository 2024. [CrossRef]

- Vitola, I.; Vircavs, V.; Abramenko, K.; Lauva, D.; Veinbergs, A. Precipitation and Air Temperature Impact on Seasonal Variations of Groundwater Levels. Environmental and Climate Technologies 2012, 10, 25-33. [CrossRef]

- Tomalski P. Dynamics of shallow groundwater resources in the Łódź Voivodeship and neighboring areas. Acta Geographica Lodziensia 2011, 97/2011, 1-102 (in Polish).

- Kaznowska, E.; Wasilewicz, M.; Hejduk, L.; Krajewski, A.; Hejduk, A. The Groundwater Resources in the Mazovian Lowland in Central Poland during the Dry Decade of 2011-2020. Water 2024, 16(2), 201. [CrossRef]

- Dobek, M. The reaction of groundwater levels to the rainfall in the years 1961–1981 in selected areas of the Lublin Upland. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska. Sectio E. Agricultira 2007. 62(1), 49-55 (in Polish).

- Chabudziński, Ł.; Michalczyk, Z. Dynamics of the groundwater levels in the border zone of Western Roztocze and the Lublin Upland in 2014. Przegląd Geologiczny 2015, 63, 639-644 (in Polish).

- Staśko, S.; Tarka, R.; Buczyński, S. Extreme weather events and their effect on the groundwater level. Examples from Lower Silesia. Przegląd Geologiczny 2017, 65, 1244-1248 (in Polish).

- Czuchaj, A.; Wolny, F.; Marciniak, M. Response of surface and groundwater to precipitation in the Różany Strumień catchment. Badania Fizjograficzne. Seria A. Geografia Fizyczna 2019, 10(70), 7-19 (in Polish). [CrossRef]

- Chlost, I. Remarks on the regime of groundwater level fluctuations of the first aquifer in the Gardeńsko-Łebska Lowland in the hydrological year 2003. Słupskie Prace Geograficzne 2005, 2, 161-170 (in Polish).

- Lidzbarski, M. The changes of groundwater level in the Cashubian ice-marginal valley aquifer (northen Poland). Przegląd Geologiczny 2002, 50(8), 717-722 (in Polish).

- Kažys, J.; Rimkus, E.; Taminskas, J.; Butkutė, S. Hydrothermal effect on groundwater level fluctuations: case studies of Čepkeliai and Rėkyva peatbogs, Lithuania. Geologija Geografija 2015, 1(3), 116-129.

- Fendeková, M. Groundwater Drought Occurrence in Slovakia. In Water Resources in Slovakia: Part II - Climate Change, Drought and Floods, Negm, A.M.; Zeleňáková, M., Eds.; The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2019; pp. 91–104. [CrossRef]

- Söller, L.; Luetkemeier, R.; Müller Schmied, H.; Döll, P. Groundwater stress in Europe – assessing incertainties in future groundwater discharge alterations due to water abstractions and climate change. Frontiers in Water 2024 6, 1448625. [CrossRef]

- Borzyszkowski, J.; Grzegorczyk, I. Staropruska Lowland (841.5). In Regional Physical Geography of Poland, Richling, A., Solon, J., Macias, A., Balon, J., Borzyszkowski, J., Kistowski, M., Eds.; Bogucki Wyd. Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2021; pp. 539-544 (in Polish).

- Giemza, A. Detailed geological map of Poland – sheet 63 – Wojciechy. Map N-34-66-A, 1:50 000. Centralna Baza Danych Geologicznych – Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny 2009 (in Polish).

- Landscape map of Poland. Główny Urząd Geodezji i Kartografii (in Polish). Available online: https://mapy.geoportal.gov.pl/imap/Imgp_2.html?SRS=2180&resources=map:wms@ https://mapy.geoportal.gov.pl/wss/service/img/guest/Krajobrazowa/MapServer/WMSServer (20 January 2025).

- Topographic map of the world. Esri. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/index.html (02 February 2025).

- Hydrological map of Poland. Główny Urząd Geodezji i Kartografii (in Polish). Available online: https://mapy.geoportal.gov.pl/imap/Imgp_2.html?SRS=2180&resources=map: wms@https://mapy.geoportal.gov.pl/wss/service/img/guest/HYDRO/MapServer/WMSServer (20 January 2025).

- Sohoulande, C.D.D. Vegetation and water resource variability within the Köppen-Geiger global climate classifcation scheme: a probabilistic interpretation. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2024, 155, 1081–1092. [CrossRef]

- Stopa-Boryczka, M.; Boryczka, J. Climate of the Northeastern Poland according to macroregions and mesoregions of J. Kondracki and J. Ostrowski, with consideration of experimental studies of the local climate. In Atlas of interdependencies between meteorological and geographical parameters in Poland, Stopa-Boryczka, M., Boryczka, J., Wawer, J., Grabowska, K., Dobrowolska, M., Osowiec, M., Błażek, E., Skrzypczuk, J., Grzęda, M., Eds.; (pp. 43-153). Wydział Geografii i Studiów Regionalnych UW: Warszawa, Poland, 2013 (in Polish).

- Małek J. Caddisflies (Trichoptera) of the Górowo Heights. Uniwersytet Warmińsko-Mazurski: Olsztyn, Poland, 2001 (in Polish).

- Climate maps of Poland. Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy (in Polish). Available online: https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-maps/#Mean_Temperature/Yearly/1991-2020/1/Winter (15 February 2025).

- Climate of Poland 2023. Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy (in Polish). Available online: https://archiwum.imgw.pl/sites/default/ files/inline-files/imgw-pib_klimat_polski_2023_raport.pdf (23 January 2025).

- Climate maps of Poland. Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy (in Polish). Available online: https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-maps/#Precipitation/Yearly/1991-2020/1/null (15 February 2025).

- Sikora, A.; Marchowski, D.; Półtorak, W. Use of beaver ponds by breeding Whooper Swans Cygnus cygnus and Mute Swans C. olor at Górowo Heights (north-eastern Poland). Ornis Polonica 2022, 63, 199–214 (in Polish).

- Zbyryt, A.; Menderski, S.; Niedźwiecki, S.; Kalski, R.; Zub, K. White Stork Ciconia ciconia breeding population in Warmińska Refuge (Natura 2000 Special Protection Area). Ornis Polonica 2014, 55, 240-256 (in Polish).

- Basic world map. OpenStreetMap contributors. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org (03 Februry 2025).

- Annex to resolution No. LVII/416/2023 of the Górowo Iławeckie Municipal Council, environmental protection program for the Górowo Iławeckie Municipality until 2030. Biuro Doradcze Ekoinferna (in Polish). Available online: https://gorowoil-ug.bip-wm.pl/public/getFile?id=380242 (6 February 2025).

- Public Data. Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej – Państwowy Instytut Badawczy (in Polish). Available online: https://danepubliczne.imgw.pl/data/dane_pomiarowo_ obserwacyjne/dane_meteorologiczne/dobowe/ (13 May 2024).

- Archived hydrological situation reports. Państwowe Gospodarstwo Wodne Wody Polskie (in Polish). Available online: https://www.wody.gov.pl/sytuacja-hydrologiczno-nawigacyjna/114-nieprzypisany/991-archiwalne-komunikaty-o-sytuacji-hydrologicznej (19 May 2024).

- Tatarczak, A. Statistics. Handbook. Case studies. Innovatio Press Wydawnictwo Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Ekonomii i Innowacji: Lublin, Poland, 2021; Volume 9 (in Polish).

- Bajkiewicz-Grabowska, E. General hydrology. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN SA: Warszawa, Poland, 2020 (in Polish).

- Jokiel, P.; Marszelewski, W.; Pociask-Karteczka, J. Hydrology of Poland. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN SA: Warszawa, Poland, 2011(in Polish).

- Somorowska, U. Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Snowfall Conditions in Poland Based on the Snow Fraction Sensitivity Index. Resources 2024, 13, 60. [CrossRef]

- Kilkus, K.; Štaras, A.; Rimkus, E.; Valiuškevičius, G. Changes in Water Balance Structure of Lithuanian Rivers under Different Climate Change Scenarios. Environmental Research, Engineering and Management 2006, 2(36), 3-10.

- Kubicz, J.; Kajewski, I.; Kajewska-Szkudlarek, J.; Dąbek, P.B. Groundwater recharge assessment in dry years. Environmental Earth Sciences 2019, 78, 1-9. [CrossRef]

| Delay in reaction (number of days) | Average daily temperature | Maximum daily temperature | Minimum daily temperature | Minimum daily temperature at ground level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0,44 | 0,42 | 0,43 | 0,41 |

| 1 | 0,43 | 0,43 | 0,45 | 0,41 |

| 2 | 0,44 | 0,44 | 0,46 | 0,42 |

| 3 | 0,45 | 0,45 | 0,47 | 0,42 |

| 4 | 0,46 | 0,46 | 0,48 | 0,43 |

| 5 | 0,47 | 0,48 | 0,49 | 0,45 |

| 6 | 0,48 | 0,49 | 0,50 | 0,46 |

| 7 | 0,49 | 0,50 | 0,51 | 0,46 |

| 8 | 0,51 | 0,51 | 0,53 | 0,48 |

| 9 | 0,52 | 0,52 | 0,54 | 0,48 |

| 10 | 0,53 | 0,54 | 0,55 | 0,49 |

| 11 | 0,54 | 0,55 | 0,56 | 0,50 |

| 12 | 0,55 | 0,56 | 0,57 | 0,51 |

| 13 | 0,56 | 0,57 | 0,58 | 0,52 |

| 14 | 0,57 | 0,58 | 0,60 | 0,53 |

| 15 | 0,58 | 0,59 | 0,61 | 0,54 |

| 16 | 0,59 | 0,60 | 0,61 | 0,55 |

| 17 | 0,60 | 0,61 | 0,62 | 0,56 |

| 18 | 0,60 | 0,62 | 0,63 | 0,56 |

| 19 | 0,61 | 0,63 | 0,64 | 0,56 |

| 20 | 0,61 | 0,63 | 0,65 | 0,57 |

| 21 | 0,62 | 0,64 | 0,65 | 0,57 |

| 22 | 0,62 | 0,65 | 0,66 | 0,57 |

| 23 | 0,62 | 0,65 | 0,66 | 0,57 |

| 24 | 0,62 | 0,65 | 0,66 | 0,57 |

| 25 | 0,62 | 0,65 | 0,66 | 0,57 |

| 26 | 0,63 | 0,65 | 0,66 | 0,58 |

| 27 | 0,63 | 0,66 | 0,67 | 0,58 |

| 28 | 0,63 | 0,66 | 0,67 | 0,57 |

| 29 | 0,62 | 0,66 | 0,67 | 0,57 |

| 30 | 0,62 | 0,66 | 0,67 | 0,57 |

| 31 | 0,62 | 0,66 | 0,67 | 0,57 |

| 32 | 0,62 | 0,66 | 0,67 | 0,57 |

| 33 | 0,62 | 0,66 | 0,67 | 0,58 |

| 34 | 0,62 | 0,67 | 0,67 | 0,58 |

| 35 | 0,62 | 0,67 | 0,67 | 0,57 |

| 36 | 0,61 | 0,67 | 0,67 | 0,57 |

| 37 | 0,61 | 0,66 | 0,66 | 0,56 |

| 38 | 0,60 | 0,66 | 0,66 | 0,55 |

| 39 | 0,59 | 0,65 | 0,65 | 0,54 |

| 40 | 0,58 | 0,64 | 0,64 | 0,53 |

| 41 | 0,56 | 0,64 | 0,63 | 0,51 |

| 42 | 0,55 | 0,63 | 0,62 | 0,50 |

| Delay in reaction (number of days) | Daily precipitation totals |

| 0 | -0,17 |

| 1 | -0,22 |

| 2 | -0,24 |

| 3 | -0,24 |

| 4 | -0,23 |

| 5 | -0,22 |

| 6 | -0,20 |

| 7 | -0,19 |

| 8 | -0,18 |

| 9 | -0,17 |

| 10 | -0,18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).