Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Distribution of ASM

2.3. Considerations of ASM Practitioners

2.4. Determinants of ASM

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Population

4.2. The Questionnaire and Data Collection

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O’Neill, J. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations. 2014. Available online: https://amr-review.org/ (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Li, J.; Song, X.; Yang, T.; Chen, Y.; Gong, Y.; Yin, X.; Lu, Z. A systematic review of antibiotic prescription associated with upper respiratory tract infections in China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Q.Q.; Ying, G.G.; Pan, C.G.; Liu, Y.S.; Zhao, J.L. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China: source analysis, multimedia modeling, and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environ Sci Technol 2015, 49, 6772–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ateshim, Y.; Bereket, B.; Major, F.; Emun, Y.; Woldai, B.; Pasha, I.; Habte, E.; Russom, M. Prevalence of self-medication with antibiotics and associated factors in the community of Asmara, Eritrea: a descriptive cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sachdev, C.; Anjankar, A.; Agrawal, J. Self-medication with antibiotics: an element increasing resistance. Cureus 2022, 14, e30844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zeb, S.; Mushtaq, M.; Ahmad, M.; Saleem, W.; Rabaan, A.A.; Naqvi, B.S.Z.; Garout, M.; Aljeldah, M.; Al-Shammari, B.R.; Al-Faraj, N.J.; Al-Zaki, N.A.; Al-Marshood, M.J.; Al-Saffar, T.Y.; Alsultan, K.A.; Al-Ahmed, S.H.; Alestad, J.H.; Naveed, M.; Ahmed, N. Self-medication as an important risk factor for antibiotic resistance: a multi-institutional survey among students. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. 2015. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/193736/9789241509763_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance: No Action Today, No Cure Tomorrow. 2011. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/antimicrobial-resistance-no-action-today-no-cure-tomorrow (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- G20 Summits. Communiqué of the G20 Leaders, Hangzhou, China. 2016. Available online: http://www.g20chn.org/hywj/dncgwj/201609/t20160906_3392.html (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Li, H.; Yan, S.; Li, D.; Gong, Y.; Lu, Z.; Yin, X. Trends and patterns of outpatient and inpatient antibiotic use in China's hospitals: data from the Center for Antibacterial Surveillance, 2012-16. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019, 74, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. China’s National Action Plan to Contain Antimicrobial Resistance. 2016. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s3593/201608/f1ed26a0c8774e1c8fc89dd481ec84d7.shtml (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Y, F. China should curb non-prescription use of antibiotics in the community[J]. BMJ 2014, 348, g4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Chang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhai, P.; Hu, S.; Li, P.; Hayat, K.; Kabba, J.A.; Feng, Z.; Yang, C.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, M.; Hu, H.; Fang, Y. Dispensing antibiotics without a prescription for acute cough associated with common cold at community pharmacies in shenyang, northeastern china: a cross-sectional study. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Widowati, I.G.A.R.; Budayanti, N.N.S.; Januraga, P.P.; Duarsa, D.P. Self-medication and self-treatment with short-term antibiotics in Asian countries: a literature review[J]. Pharm Educ 2021, 21, 152–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, K.; Chung, D.R.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, S.Y.; Ha, Y.E.; Kang, C.I.; Peck, K.R.; Song, J.H. Factors affecting the public awareness and behavior on antibiotic use. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018, 37, 1547–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demoré, B.; Mangin, L.; Tebano, G.; Pulcini, C.; Thilly, N. Public knowledge and behaviours concerning antibiotic use and resistance in France: a cross-sectional survey. Infection 2017, 45, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, B.; Zhao, L.; Li, S.; Li, L. Changes in Chinese policies to promote the rational use of antibiotics. PLoS Med 2013, 10, e1001556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Do, N.T.T.; Vu, H.T.L.; Nguyen, C.T.K.; Punpuing, S.; Khan, W.A.; Gyapong, M.; Asante, K.P.; Munguambe, K.; Gómez-Olivé, F.X.; John-Langba, J.; et al. Community-based antibiotic access and use in six low-income and middle-income countries: a mixed-method approach. Lancet Glob Health 2021, 9, e610–e619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Monnet, D.L.; Harbarth, S. Will coronavirus disease (COVID-19) have an impact on antimicrobial resistance? Euro Surveill 2020, 25, 2001886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, Y.; Fan, S.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y. Broader open data needed in psychiatry: practice from the psychology and behavior investigation of chinese residents. Alpha Psychiatry 2024, 25, 564–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- China Family News. CFHI-2021 China Family Health Index Survey General Report[EB/OL]. (Chinese). Available from: https://www.cfnews.org.cn/newsinf o/2685237.html.

- Ye, D.; Chang, J.; Yang, C.; Yan, K.; Ji, W.; Aziz, M.M.; Gillani, A.H.; Fang, Y. How does the general public view antibiotic use in China? Result from a cross-sectional survey. Int J Clin Pharm 2017, 39, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, P.; Yu, J.; Zhou, N.; Hu, M. Access to medicines for acute illness and antibiotic use in residents: A medicines household survey in Sichuan Province, western China. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0201349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McNulty, C.A.; Boyle, P.; Nichols, T.; Clappison, P.; Davey, P. Don't wear me out--the public's knowledge of and attitudes to antibiotic use. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007, 59, 727–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virmani, S.; Nandigam, M.; Kapoor, B.; Makhija, P.; Nair, S. Antibiotic use among health science students in an Indian University: a cross sectional study[J]. Clin Epidemiol Global Health 2017, 5, 176–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Using Indicators to Measure Country Pharmaceutical Situations: Fact Book on WHO Level I and Level II Monitoring Indicators. 2006. Available online: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/index/assoc/s14101e/s14101e.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Grigoryan, L.; Burgerhof, J.G.; Degener, J.E.; Deschepper, R.; Lundborg, C.S.; Monnet, D.L.; Scicluna, E.A.; Birkin, J.; Haaijer-Ruskamp, F.M.; SAR consortium. Attitudes, beliefs and knowledge concerning antibiotic use and self-medication: a comparative European study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007, 16, 1234–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L. Background for different use of antibiotics in different countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 40, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, J.S.; Frazer, G.R. Analysis of primary care prescription trends in England during the COVID-19 pandemic compared against a predictive model. Fam Med Community Health 2021, 9, e001143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mitsi, G.; Jelastopulu, E.; Basiaris, H.; Skoutelis, A.; Gogos, C. Patterns of antibiotic use among adults and parents in the community: a questionnaire-based survey in a Greek urban population. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2005, 25, 439–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.R.M.; Dolk, F.C.K.; Smieszek, T.; Robotham, J.V.; Pouwels, K.B. Understanding the gender gap in antibiotic prescribing: a cross-sectional analysis of English primary care. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McNulty, C.A.; Boyle, P.; Nichols, T.; Clappison, P.; Davey, P. The public's attitudes to and compliance with antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007, 60, 63–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogale, A.A.; Amhare, A.F.; Chang, J.; Bogale, H.A.; Betaw, S.T.; Gebrehiwot, N.T.; Fang, Y. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of self-medication with antibiotics among community residents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2019, 17, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Antibiotic Resistance: Multi-Country Public.

- Vahedi, S.; Jalali, F.S.; Bayati, M.; Delavari, S. Predictors of self-medication in Iran: a notional survey study. Iran J Pharm Res 2021, 20, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grigoryan, L.; Haaijer-Ruskamp, F.M.; Burgerhof, J.G.; Mechtler, R.; Deschepper, R.; Tambic-Andrasevic, A.; Andrajati, R.; Monnet, D.L.; Cunney, R.; Di-Matteo, A.; et al. Self-medication with antimicrobial drugs in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 2006, 12, 452–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lukovic, J.A.; Miletic, V.; Pekmezovic, T.; Trajkovic, G.; Ratkovic, N.; Aleksic, D.; Grgurevic, A. Self-medication practices and risk factors for self-medication among medical students in Belgrade, Serbia. PLoS One 2014, 9, e114644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yu, W.; Wang, H. Changes in social support among patients with hematological malignancy undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Souzhou, China. Indian J Cancer 2020, 57, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awuah, R.B.; Asante, P.Y.; Sakyi, L.; Biney, A.A.E.; Kushitor, M.K.; Agyei, F.; de-Graft Aikins, A. Factors associated with treatment-seeking for malaria in urban poor communities in Accra, Ghana. Malar J 2018, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, L. Legislation of clinical antibiotic use in China. Lancet Infect Dis 2013, 13, 189–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoloni, A.; Cutts, F.; Leoni, S.; Austin, C.C.; Mantella, A.; Guglielmetti, P.; Roselli, M.; Salazar, E.; Paradisi, F. Patterns of antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance among healthy children in Bolivia. Trop Med Int Health 1998, 3, 116–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Xu, S.; Zhu, S.; Li, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zu, J.; Fang, Y.; Ross-Degnan, D. Assessment of non-prescription antibiotic dispensing at community pharmacies in China with simulated clients: a mixed cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019, 19, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | n (%) | χ2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Total | ||||

| Total | 8008 (72.60) | 3023 (27.40) | 11031 (100.00) | |||

| Gender | 0.0831 | 0.7731 | ||||

| Male | 3647 (45.54) | 1386 (45.86) | 5033 (45.63) | |||

| Female | 4361 (54.56) | 1637 (54.15) | 5998 (54.37) | |||

| Age (years) | 179.8654 | <0.0001 | ||||

| 0–30 | 3377 (42.17) | 1288 (42.61) | 4665 (42.29) | |||

| 31–45 | 2325 (29.03) | 676 (22.36) | 3001 (27.21) | |||

| 46–59 | 1652 (20.63) | 566 (18.72) | 2218 (20.11) | |||

| 60– | 654 (8.17) | 493 (16.31) | 1147 (10.40) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 3.7998 | 0.1496 | ||||

| <18.5 | 1103 (13.77) | 459 (15.18) | 1562 (14.16) | |||

| 18.5–24.9 | 5510 (68.81) | 2035 (67.32) | 7545 (68.40) | |||

| 25– | 1395 (17.42) | 529 (17.50) | 1924 (17.44) | |||

| Spouse | 34.7433 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 2243 (60.34) | 3983 (54.56) | 6226 (56.44) | |||

| No | 1474 (39.66) | 3331 (45.54) | 4805 (43.56) | |||

| Education level | 832.9165 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Primary or below | 473 (5.91) | 654 (21.63) | 1127 (10.22) | |||

| Secondary | 2272 (28.37) | 1145 (37.88) | 3417 (30.98) | |||

| Higher | 5263 (65.72) | 1224 (40.49) | 6487 (58.81) | |||

| Occupation | 527.0434 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Unemployed | 4496 (56.14) | 2379 (78.70) | 6875 (62.32) | |||

| Blue-collar | 992 (12.39) | 295 (9.76) | 1287 (11.67) | |||

| White-collar | 2520 (31.47) | 349 (11.54) | 2869 (26.01) | |||

| Monthly household income per capita | 1020.805 | <0.0001 | ||||

| 0–3000 | 1714 (21.40) | 1532 (50.68) | 3246 (29.43) | |||

| 3001–6000 | 3229 (40.32) | 1025 (33.91) | 4254 (38.56) | |||

| 6001– | 3065 (38.27) | 466 (15.42) | 3531 (32.01) | |||

| Medical insurance | 60.1299 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Resident/employee | 6083 (75.96) | 2206 (72.97) | 8289 (75.14) | |||

| Commercial | 203 (2.53) | 34 (1.12) | 237 (2.15) | |||

| Government-funded | 168 (2.10) | 38 (1.26) | 206 (1.87) | |||

| Out-of-pocket payment | 1554 (19.41) | 745 (24.64) | 2299 (20.84) | |||

| Number of chronic diseases | 11.7185 | 0.0029 | ||||

| none | 6644 (82.97) | 2442 (80.78) | 9086 (82.37) | |||

| Single | 932 (11.64) | 369 (12.21) | 1301 (11.79) | |||

| Multiple | 432 (5.39) | 212 (7.01) | 644 (5.84) | |||

| Smoking history | 15.2551 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 1514 (18.91) | 672 (22.23) | 2186 (19.82) | |||

| No | 6494 (81.09) | 2351 (77.77) | 8845 (80.18) | |||

| Drinking history | 42.7765 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 3383 (42.25) | 1070 (35.40) | 4453 (40.37) | |||

| No | 4652 (57.75) | 1953 (64.60) | 6578 (59.63) | |||

| Variables | ASM [n (%)] | χ2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | ||||

| Total | 3717 (33.70) | 7314 (66.30) | 11031 (100.00) | |||

| Gender | 6.6819 | 0.0097 | ||||

| Male | 1632 (43.91) | 3401 (46.50) | 5033 (45.63) | |||

| Female | 2085 (56.09) | 3913 (53.50) | 5998 (54.37) | |||

| Age (years) | 55.2949 | <0.0001 | ||||

| 0–30 | 1423 (38.28) | 3242 (44.33) | 4665 (42.29) | |||

| 31–45 | 1020 (27.44) | 1981 (27.09) | 3001 (27.21) | |||

| 46–59 | 876 (23.57) | 1342 (18.35) | 2218 (20.11) | |||

| 60– | 398 (10.71) | 749 (10.24) | 1147 (10.40) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 14.5356 | 0.0007 | ||||

| <18.5 | 471 (12.67) | 1091 (14.92) | 1562 (14.16) | |||

| 18.5–24.9 | 2548 (68.55) | 4997 (68.32) | 7545 (68.40) | |||

| 25– | 698 (18.78) | 1226 (16.72) | 1924 (17.44) | |||

| Spouse | 34.7433 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 2243 (60.34) | 3983 (54.46) | 6226 (56.44) | |||

| No | 1474 (39.66) | 3331 (45.54) | 4805 (43.56) | |||

| Education level | ||||||

| Primary or below | 324 (8.72) | 803 (10.98) | 1127 (10.22) | 14.7739 | 0.0006 | |

| Secondary | 1148 (30.89) | 2269 (31.02) | 3417 (30.98) | |||

| Higher | 2245 (60.40) | 4242 (58.00) | 6487 (58.81) | |||

| Occupation | 48.6309 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Unemployed | 2156 (58.00) | 4719 (64.52) | 6875 (62.32) | |||

| Blue-collar | 455 (12.24) | 832 (11.38) | 1287 (11.67) | |||

| White-collar | 1106 (29.76) | 1763 (24.10) | 2869 (26.01) | |||

| Monthly household income per capita | 4.7330 | 0.0938 | ||||

| 0–3000 | 1045 (28.11) | 2201 (30.09) | 3246 (29.43) | |||

| 3001–6000 | 1454 (39.12) | 2800 (38.28) | 4254 (38.56) | |||

| 6001– | 1218 (32.77) | 2313 (31.62) | 3531 (32.01) | |||

| Medical insurance | 60.5866 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Resident/employee | 2931 (78.85) | 5358 (72.98) | 8289 (75.14) | |||

| Commercial | 95 (2.56) | 142 (1.94) | 237 (2.15) | |||

| Government-funded | 70 (1.88) | 136 (1.86) | 206 (1.87) | |||

| Out-of-pocket payment | 621 (16.71) | 1678 (22.94) | 2299 (20.84) | |||

| Number of chronic diseases | 65.5118 | <0.0001 | ||||

| none | 2921 (78.58) | 6165 (84.29) | 9086 (82.37) | |||

| Single | 501 (13.48) | 800 (10.94) | 1301 (11.79) | |||

| Multiple | 295 (7.94) | 349 (4.77) | 644 (5.84) | |||

| Smoking history | 6.7482 | 0.0094 | ||||

| Yes | 788 (21.20) | 1398 (18.99) | 2186 (19.82) | |||

| No | 2929 (78.80) | 5916 (80.89) | 8845 (80.18) | |||

| Drinking history | 19.8502 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 1609 (43.29) | 2844 (38.88) | 4453 (40.37) | |||

| No | 2108 (56.71) | 4470 (61.12) | 6578 (59.63) | |||

| Residence | 11.0567 | 0.0009 | ||||

| Urban | 2772 (74.58) | 5236 (71.59) | 8008 (72.60) | |||

| Rural | 945 (25.42) | 2078 (28.41) | 3023 (27.40) | |||

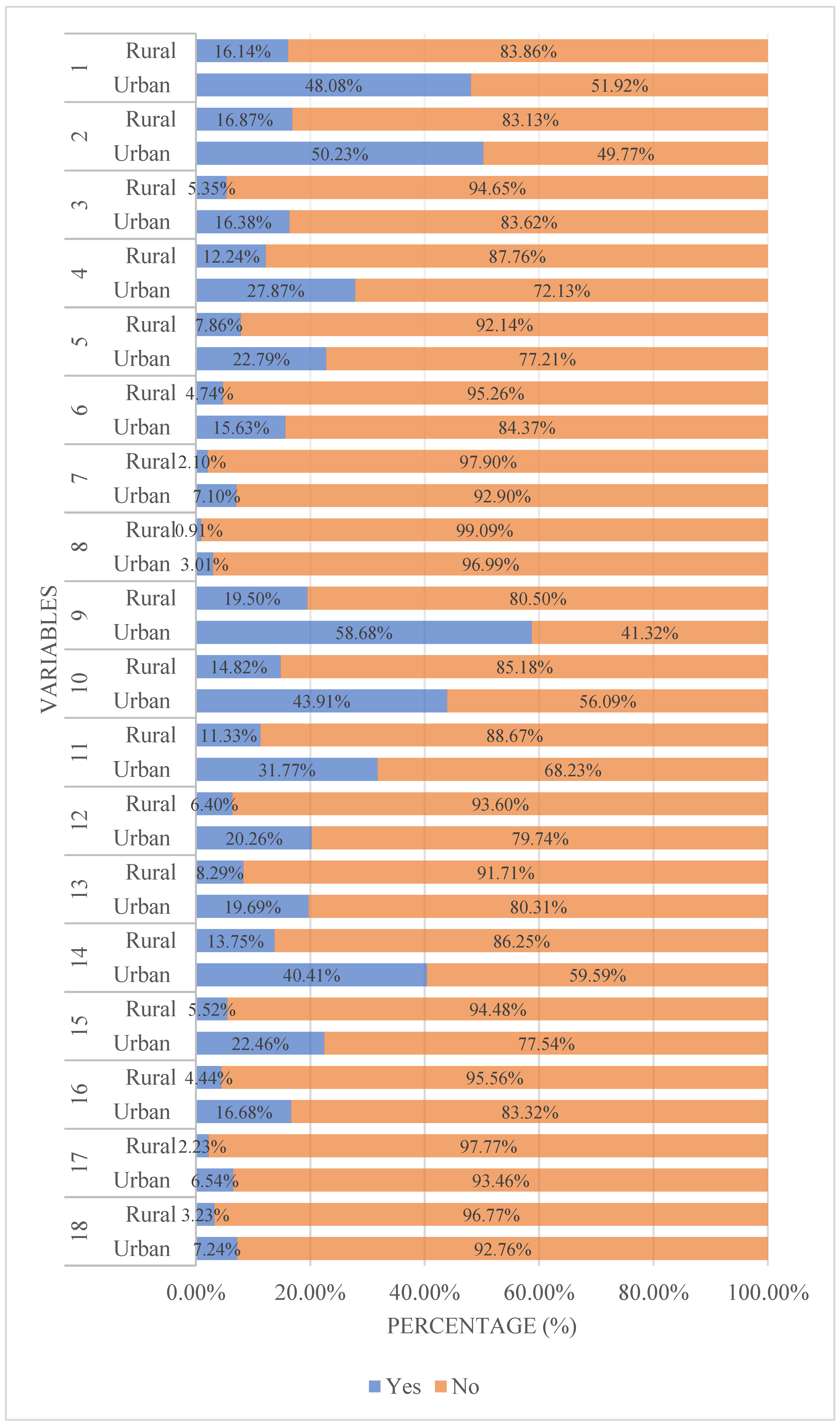

| Variables | n (%) | χ2 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Rural | Total | ||||

| Total | 2772 (74.58) | 945 (25.42) | 3717 (100.00) | |||

| Clinical factors | ||||||

| 1 Drug efficacy | 1787 (64.47) | 600 (63.49) | 2387 (64.22) | 0.2910 | 0.5896 | |

| 2 Drug safety | 1867 (67.35) | 627 (66.35) | 2494 (67.10) | 0.3211 | 0.5710 | |

| 3 Dosage form (e.g., capsules, patches) | 609 (21.97) | 199 (21.06) | 808 (21.74) | 0.3442 | 0.5574 | |

| Economic & accessibility | ||||||

| 4 Drug price | 1036 (37.37) | 455 (48.15) | 1491 (40.11) | 34.0566 | <0.0001 | |

| 5 Insurance reimbursement eligibility | 847 (30.56) | 292 (30.90) | 1139 (30.64) | 0.0392 | 0.8430 | |

| Convenience & experience | ||||||

| 6 Ease of administration | 581 (20.96) | 176 (18.62) | 757 (20.37) | 2.3697 | 0.1237 | |

| 7 Taste of medication | 264 (9.52) | 78 (8.25) | 342 (9.20) | 1.3602 | 0.2435 | |

| 8 Packaging aesthetics | 112 (4.04) | 34 (3.60) | 146 (3.93) | 0.3657 | 0.5453 | |

| Social & personal advice | ||||||

| 9 Physician’s advice | 2181 (78.68) | 725 (76.72) | 2906 (78.18) | 1.5873 | 0.2077 | |

| 10 Pharmacist’s advice | 1632 (58.87) | 551 (58.31) | 2183 (58.73) | 0.0937 | 0.7596 | |

| 11 Family member’s suggestions | 1181 (42.60) | 421 (44.55) | 1602 (43.10) | 1.0879 | 0.2969 | |

| 12 Friend’s suggestions | 753 (27.16) | 238 (25.19) | 991 (26.66) | 1.4120 | 0.2347 | |

| 13 Recommendations from sales personnel | 732 (26.41) | 308 (32.59) | 1040 (27.98) | 13.3816 | 0.0003 | |

| 14 Personal experience | 1502 (54.18) | 511 (54.07) | 2013 (54.16) | 0.0035 | 0.9530 | |

| Brand & corporate | ||||||

| 15 Brand reputation | 835 (30.12) | 205 (21.69) | 1040 (27.98) | 24.8509 | <0.0001 | |

| 16 Corporate credibility | 620 (22.37) | 165 (17.46) | 785 (21.12) | 10.1830 | 0.0014 | |

| 17 Advertising influence | 243 (8.77) | 83 (8.78) | 326 (8.77) | 0.0002 | 0.9874 | |

| 18 After-sales service | 269 (9.70) | 120 (12.70) | 389 (10.47) | 6.7430 | 0.0094 | |

| Variables | β | SE | Wald χ2 | p-Value | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -0.2714 | 0.1474 | 3.3924 | 0.0655 | ||

| Gender (Ref: Female) | ||||||

| Male | -0.2619 | 0.0480 | 29.7837 | <0.0001 | 0.770 (0.700, 0.845) | |

| Age (Ref: 60–) | ||||||

| 0–30 | -0.0321 | 0.0953 | 0.1133 | 0.7364 | 0.968 (0.803, 1.167) | |

| 31–45 | -0.0108 | 0.0857 | 0.0159 | 0.8997 | 0.989 (0.836, 1.170) | |

| 46–59 | 0.1848 | 0.0841 | 4.8313 | 0.0279 | 1.203 (1.020, 1.418) | |

| BMI (Ref: 25–) | ||||||

| <18.5 | -0.1350 | 0.0771 | 3.0688 | 0.0798 | 0.874 (0.751, 1.016) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | -0.0362 | 0.0553 | 0.4279 | 0.5130 | 0.964 (0.865, 1.075) | |

| Spouse (Ref: No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.0408 | 0.0610 | 0.4482 | 0.5032 | 1.042 (0.924, 1.174) | |

| Education level (Ref: Higher) | ||||||

| Primary or below | -0.3759 | 0.0863 | 18.9833 | <0.0001 | 0.687 (0.580, 0.813) | |

| Secondary | -0.0769 | 0.0509 | 2.2792 | 0.1311 | 0.926 (0.838, 1.023) | |

| Occupation (Ref: White-collar) | ||||||

| Unemployed | -0.1291 | 0.0559 | 5.3329 | 0.0209 | 0.879 (0.788, 0.981) | |

| Blue-collar | -0.0905 | 0.0729 | 1.5406 | 0.2145 | 0.913 (0.792, 1.054) | |

| Monthly household income per capita (Ref: 6001–) | ||||||

| 0-3000 | 0.0330 | 0.0570 | 0.3365 | 0.5618 | 1.034 (0.924, 1.156) | |

| 3001-6000 | 0.0203 | 0.0492 | 0.1707 | 0.6795 | 1.021 (0.927, 1.124) | |

| Medical insurance (Ref: Out-of-pocket payment) | ||||||

| Resident/employee | 0.2826 | 0.0552 | 26.2324 | <0.0001 | 1.327 (1.191, 1.478) | |

| Commercial | 0.4848 | 0.1430 | 11.4930 | 0.0007 | 1.624 (1.227, 2.149) | |

| Government-funded | 0.2163 | 0.1572 | 1.8926 | 0.1689 | 1.241 (0.912, 1.690) | |

| Number of chronic diseases (Ref: Multiple) | ||||||

| None | -0.5776 | 0.0913 | 39.9822 | <0.0001 | 0.561 (0.469, 0.671) | |

| Single | -0.3353 | 0.0997 | 11.3167 | 0.0008 | 0.715 (0.588, 0.869) | |

| Smoking history (Ref: No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.0849 | 0.0608 | 1.9542 | 0.1621 | 1.089 (0.966, 1.226) | |

| Drinking history (Ref: No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.1830 | 0.0461 | 15.7526 | <0.0001 | 1.201 (1.097, 1.314) | |

| Residence (Ref: Rural) | ||||||

| Urban | 0.0454 | 0.0501 | 0.8211 | 0.3648 | 1.046 (0.949, 1.154) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).