Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

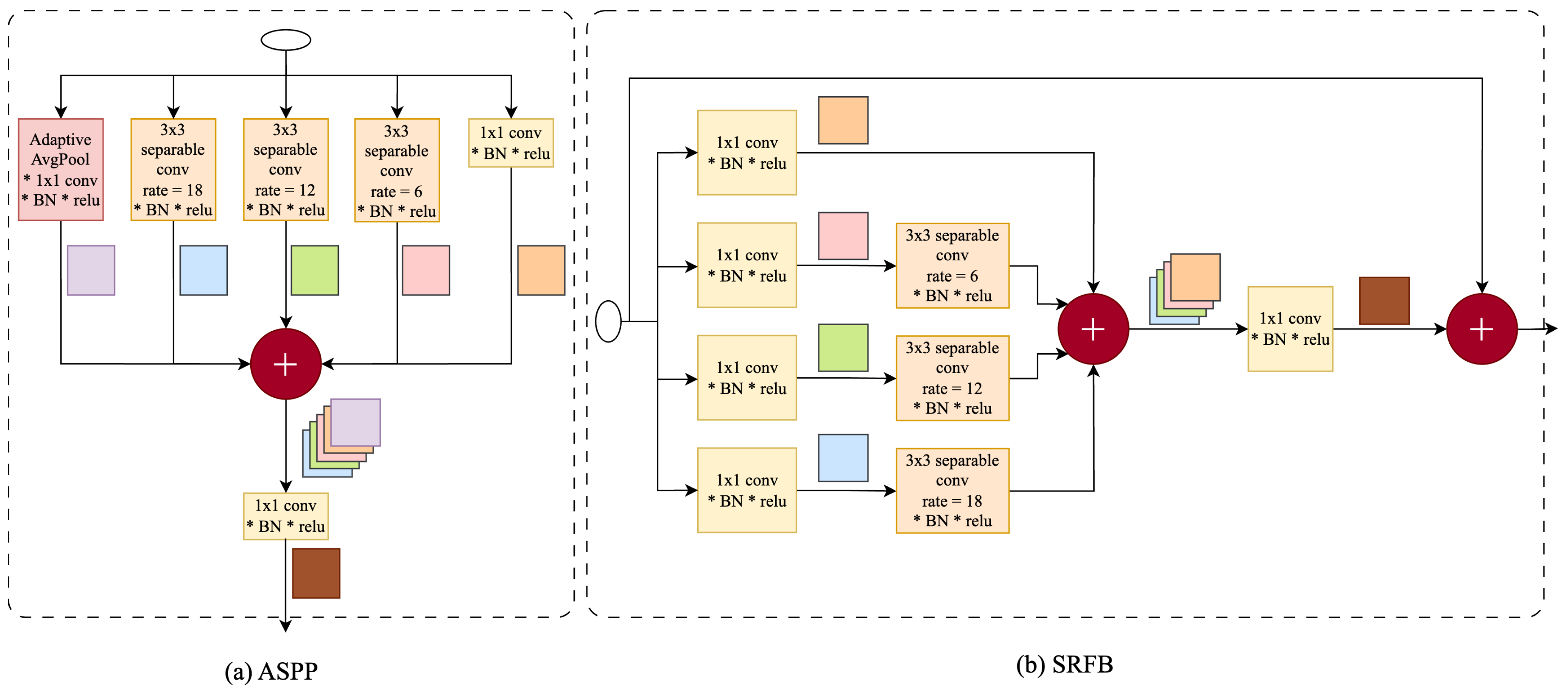

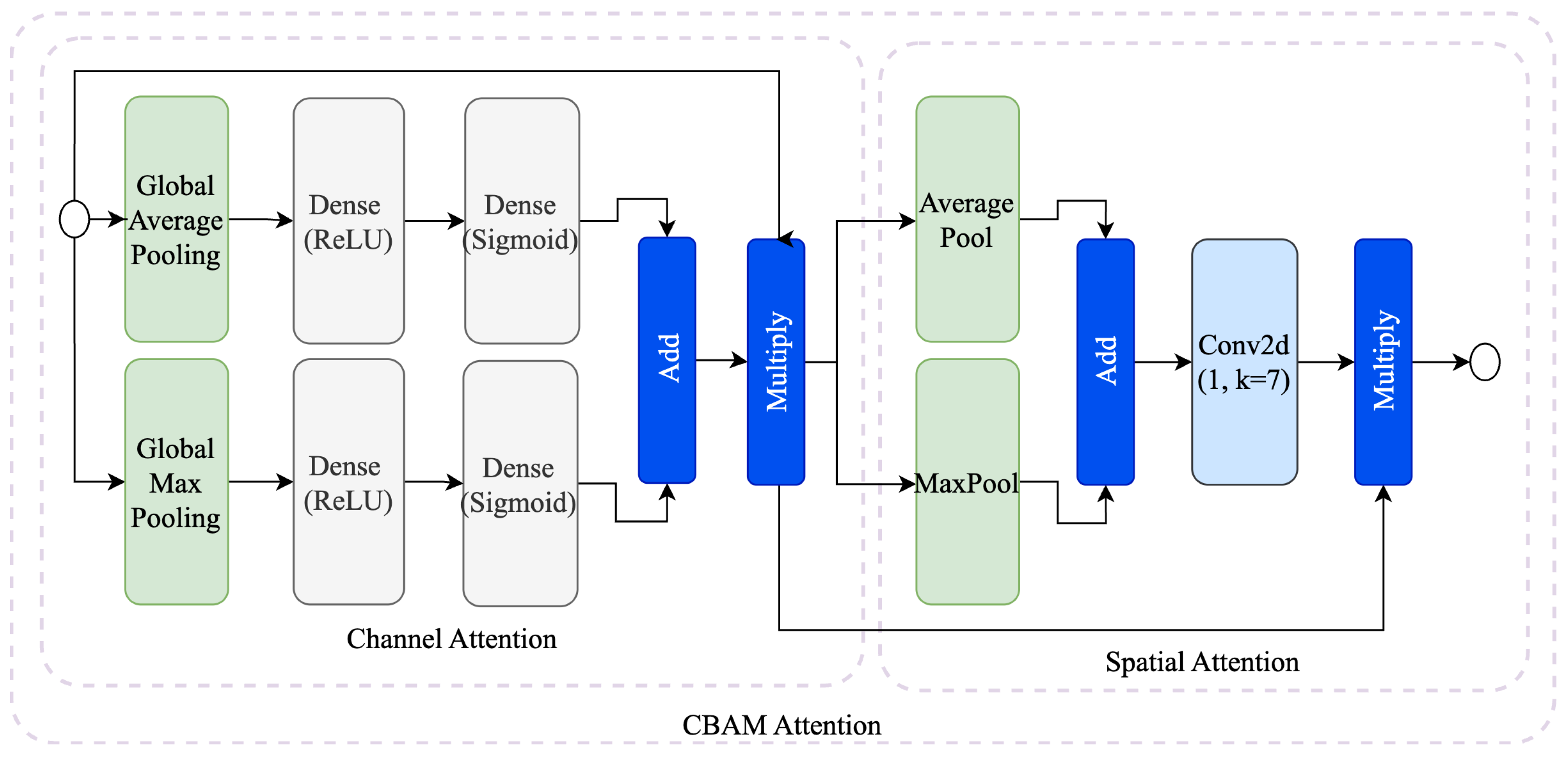

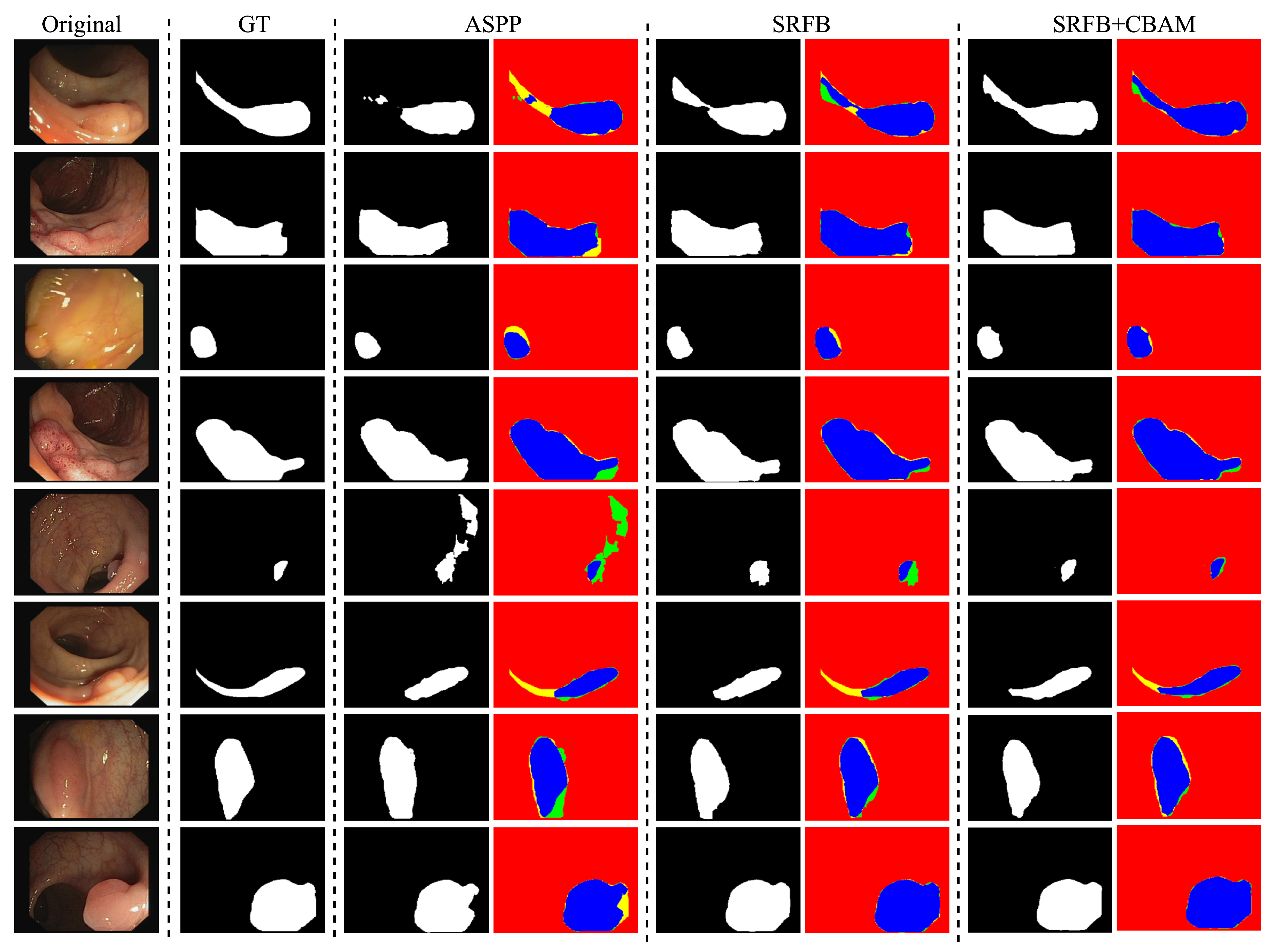

- Propose a novel Separable Receptive Field Block (SRFB) integrated with a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to replace the traditional Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP), improving the preservation of spatial details and multi-scale contextual information capture.

- Enhance segmentation accuracy, particularly for small and irregularly shaped polyps, by leveraging lightweight EfficientNet encoders for efficient feature extraction.

- Achieve superior performance compared to state-of-the-art methods through extensive evaluation on benchmark datasets, including Kvasir, CVC-ClinicDB, and CVC-ColonDB, using Dice Coefficient and Intersection over Union (IoU) metrics.

- Ensure computational efficiency suitable for real-time medical imaging applications, facilitating potential clinical deployment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Recent Advances in Colon Polyp Segmentation

2.2. Gaps in Existing Methods

2.3. Positioning Our Approach

3. DeepColonLab

3.1. Encoder

3.2. Separable Receptive Field Block

3.2.1. Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM)

3.3. Decoder

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Datasets

- Kvasir: This dataset contains 1,000 endoscopic images collected at Vestre Viken Health Trust (VV), Norway. The image resolutions range from to pixels. All annotations were carefully performed and verified by experienced gastroenterologists from VV and the Cancer Registry of Norway.

- CVC-ClinicDB: Composed of 612 image frames with a resolution of pixels, this dataset was extracted from 31 colonoscopy video sequences. It was used in the MICCAI 2015 Sub-Challenge on Automatic Polyp Detection in Colonoscopy Videos.

- CVC-ColonDB: Provided by the Machine Vision Group (MVG), this dataset includes 380 images with a resolution of pixels. The images were taken from 15 short colonoscopy video sequences.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics and Loss Function

4.3. Implementation Details

5. Experiments

5.1. Experiment 1

5.2. Experiment 2

5.3. Experiment 3

5.4. Comparison with Other Recent Works

6. Conclusions

References

- R. L. Siegel, K. D. Miller, N. S. Wagle, A. Jemal, Cancer statistics, 2023, CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 73 (1) (2023) 17–48.

- J. Bond, Colon polyps and cancer, Endoscopy 35 (01) (2003) 27–35.

- R. L. Siegel, A. N. Giaquinto, A. Jemal, Cancer statistics, 2024, CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 74 (1) (2024) 12–49.

- D. A. Lieberman, D. G. Weiss, J. H. Bond, D. J. Ahnen, H. Garewal, W. V. Harford, D. Provenzale, S. Sontag, T. Schnell, T. E. Durbin, et al., Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer, New England Journal of Medicine 343 (3) (2000) 162–168. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Zauber, S. J. Winawer, M. J. O’Brien, I. Lansdorp-Vogelaar, M. van Ballegooijen, B. F. Hankey, W. Shi, J. H. Bond, M. Schapiro, J. F. Panish, et al., Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths, New England Journal of Medicine 366 (8) (2012) 687–696. [CrossRef]

- S. Sanduleanu, C. M. le Clercq, E. Dekker, G. A. Meijer, L. Rabeneck, M. D. Rutter, R. Valori, G. P. Young, R. E. Schoen, Definition and taxonomy of interval colorectal cancers: a proposal for standardising nomenclature, Gut 64 (8) (2015) 1257–1267. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Topol, High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence, Nature medicine 25 (1) (2019) 44–56. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Hashimoto, G. Rosman, D. Rus, O. R. Meireles, Artificial intelligence in surgery: promises and perils, Annals of surgery 268 (1) (2018) 70–76. [CrossRef]

- O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer, T. Brox, U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation, in: Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, proceedings, part III 18, Springer, 2015, pp. 234–241.

- Z. Zhou, M. M. Rahman Siddiquee, N. Tajbakhsh, J. Liang, Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation, in: Deep learning in medical image analysis and multimodal learning for clinical decision support: 4th international workshop, DLMIA 2018, and 8th international workshop, ML-CDS 2018, held in conjunction with MICCAI 2018, Granada, Spain, September 20, 2018, proceedings 4, Springer, 2018, pp. 3–11.

- O. Oktay, J. Schlemper, L. L. Folgoc, M. Lee, M. Heinrich, K. Misawa, K. Mori, S. McDonagh, N. Y. Hammerla, B. Kainz, et al., Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arxiv, arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.03999 10 (2018).

- D. Jha, P. H. Smedsrud, M. A. Riegler, D. Johansen, T. De Lange, P. Halvorsen, H. D. Johansen, Resunet++: An advanced architecture for medical image segmentation, in: 2019 IEEE international symposium on multimedia (ISM), IEEE, 2019, pp. 225–2255. [CrossRef]

- D.-P. Fan, G.-P. Ji, T. Zhou, G. Chen, H. Fu, J. Shen, L. Shao, Pranet: Parallel reverse attention network for polyp segmentation, in: International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention, Springer, 2020, pp. 263–273.

- L.-C. Chen, G. Papandreou, F. Schroff, H. Adam, Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation, arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.05587 (2017).

- A. Dosovitskiy, L. Beyer, A. Kolesnikov, D. Weissenborn, X. Zhai, T. Unterthiner, M. Dehghani, M. Minderer, G. Heigold, S. Gelly, et al., An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale, arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

- J. Chen, Y. Lu, Q. Yu, X. Luo, E. Adeli, Y. Wang, L. Lu, A. L. Yuille, Y. Zhou, Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation, arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.04306 (2021).

- J. M. J. Valanarasu, P. Oza, I. Hacihaliloglu, V. M. Patel, Medical transformer: Gated axial-attention for medical image segmentation, in: Medical image computing and computer assisted intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th international conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, proceedings, part I 24, Springer, 2021, pp. 36–46.

- L.-C. Chen, Y. Zhu, G. Papandreou, F. Schroff, H. Adam, Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation, in: Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 801–818.

- B. Dong, W. Wang, D.-P. Fan, J. Li, H. Fu, L. Shao, Polyp-pvt: Polyp segmentation with pyramid vision transformers, arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.06932 (2021). [CrossRef]

- J. Wei, Y. Hu, R. Zhang, Z. Li, S. K. Zhou, S. Cui, Shallow attention network for polyp segmentation, in: Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part I 24, Springer, 2021, pp. 699–708.

- C.-H. Huang, H.-Y. Wu, Y.-L. Lin, Hardnet-mseg: A simple encoder-decoder polyp segmentation neural network that achieves over 0.9 mean dice and 86 fps, arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.07172 (2021).

- N. T. Duc, N. T. Oanh, N. T. Thuy, T. M. Triet, V. S. Dinh, Colonformer: An efficient transformer based method for colon polyp segmentation, IEEE Access 10 (2022) 80575–80586. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Sikkandar, S. G. Sundaram, A. Alassaf, I. AlMohimeed, K. Alhussaini, A. Aleid, S. A. Alolayan, P. Ramkumar, M. K. Almutairi, S. S. Begum, Utilizing adaptive deformable convolution and position embedding for colon polyp segmentation with a visual transformer, Scientific Reports 14 (1) (2024) 7318. [CrossRef]

- J. Ren, X. Zhang, L. Zhang, Hifiseg: High-frequency information enhanced polyp segmentation with global-local vision transformer, IEEE Access (2025). [CrossRef]

- Z. Ji, H. Qian, X. Ma, Progressive group convolution fusion network for colon polyp segmentation, Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 96 (2024) 106586. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, J. Mu, H. Sun, C. Dai, Z. Ji, I. Ganchev, Dlgrafe-net: A double loss guided residual attention and feature enhancement network for polyp segmentation, Plos one 19 (9) (2024) e0308237. [CrossRef]

- S. Pathan, Y. Somayaji, T. Ali, M. Varsha, Contournet-an automated segmentation framework for detection of colonic polyps, IEEE Access (2024). [CrossRef]

- H. Xue, L. Yonggang, L. Min, L. Lin, A lighter hybrid feature fusion framework for polyp segmentation, Scientific Reports 14 (1) (2024) 23179. [CrossRef]

- C. Xu, K. Fan, W. Mo, X. Cao, K. Jiao, Dual ensemble system for polyp segmentation with submodels adaptive selection ensemble, Scientific Reports 14 (1) (2024) 6152. [CrossRef]

- S. Xiang, L. Wei, K. Hu, Lightweight colon polyp segmentation algorithm based on improved deeplabv3+, Journal of Cancer 15 (1) (2024) 41.

- S. Gangrade, P. C. Sharma, A. K. Sharma, Y. P. Singh, Modified deeplabv3+ with multi-level context attention mechanism for colonoscopy polyp segmentation, Computers in Biology and Medicine 170 (2024) 108096. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, D. Huang, et al., Receptive field block net for accurate and fast object detection, in: Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 385–400.

- D. Jha, P. H. Smedsrud, M. A. Riegler, P. Halvorsen, T. De Lange, D. Johansen, H. D. Johansen, Kvasir-seg: A segmented polyp dataset, in: International conference on multimedia modeling, Springer, 2019, pp. 451–462.

- J. Bernal, F. J. Sánchez, G. Fernández-Esparrach, D. Gil, C. Rodríguez, F. Vilariño, Wm-dova maps for accurate polyp highlighting in colonoscopy: Validation vs. saliency maps from physicians, Computerized medical imaging and graphics 43 (2015) 99–111. [CrossRef]

- N. Tajbakhsh, S. R. Gurudu, J. Liang, Automated polyp detection in colonoscopy videos using shape and context information, IEEE transactions on medical imaging 35 (2) (2015) 630–644. [CrossRef]

| Type | Dice (mean ± std) | IoU (mean ± std) | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resnet50+ASPP | 0.9391 ± 0.0070 | 0.9012 ± 0.0083 | 27,026,338 |

| Resnet50+RFB | 0.9419 ± 0.0053 | 0.9036 ± 0.0079 | 27,110,050 |

| Resnet101+ASPP | 0.9354 ± 0.0016 | 0.8963 ± 0.0019 | 46,018,466 |

| Resnet101+RFB | 0.9394 ± 0.0104 | 0.9012 ± 0.0141 | 46,102,178 |

| Resnet152+ASPP | 0.9377 ± 0.0086 | 0.8992 ± 0.0127 | 61,662,114 |

| Resnet152+RFB | 0.9368 ± 0.0102 | 0.8977 ± 0.0134 | 61,745,826 |

| Densenet121+ASPP | 0.9373 ± 0.0084 | 0.9000 ± 0.0112 | 8,986,338 |

| Densenet121+RFB | 0.9426 ± 0.0061 | 0.9072 ± 0.0080 | 9,097,698 |

| Densenet169+ASPP | 0.9413 ± 0.0061 | 0.9041 ± 0.0082 | 15,353,442 |

| Densenet169+RFB | 0.9412 ± 0.0107 | 0.9054 ± 0.0139 | 15,447,522 |

| Densenet201+ASPP | 0.9421 ± 0.0049 | 0.9056 ± 0.0061 | 21,296,482 |

| Densenet201+RFB | 0.9339 ± 0.0014 | 0.8952 ± 0.0017 | 21,383,650 |

| EfficientnetB0+ASPP | 0.9501 ± 0.0034 | 0.9180 ± 0.0040 | 5,000,094 |

| EfficientnetB0+RFB | 0.9512 ± 0.0053 | 0.9202 ± 0.0069 | 5,130,462 |

| EfficientnetB1+ASPP | 0.9455 ± 0.0010 | 0.9123 ± 0.0014 | 7,505,730 |

| EfficientnetB1+RFB | 0.9558 ± 0.0047 | 0.9258 ± 0.0060 | 7,636,098 |

| EfficientnetB2+ASPP | 0.9529 ± 0.0050 | 0.9225 ± 0.0072 | 8,735,364 |

| EfficientnetB2+RFB | 0.9573 ± 0.0053 | 0.9275 ± 0.0082 | 8,864,868 |

| EfficientnetB3+ASPP | 0.9564 ± 0.0055 | 0.9266 ± 0.0076 | 11,781,642 |

| EfficientnetB3+RFB | 0.9577 ± 0.0037 | 0.9288 ± 0.0042 | 11,910,282 |

| Encoder | Dice (mean ± std) | IoU (mean ± std) | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| EfficientNetB0 | 0.9524 ± 0.0044 | 0.9209 ± 0.0064 | 5,138,752 |

| EfficientNetB1 | 0.9579 ± 0.0030 | 0.9278 ± 0.0042 | 7,644,388 |

| EfficientNetB2 | 0.9590 ± 0.0038 | 0.9301 ± 0.0046 | 8,873,158 |

| EfficientNetB3 | 0.9593 ± 0.0023 | 0.9304 ± 0.0038 | 11,918,572 |

| EfficientNetB4 | 0.9583 ± 0.0029 | 0.9289 ± 0.0044 | 18,852,876 |

| EfficientNetB5 | 0.9591 ± 0.0042 | 0.9308 ± 0.0051 | 29,736,180 |

| EfficientNetB6 | 0.9597 ± 0.0060 | 0.9314 ± 0.0084 | 42,213,020 |

| EfficientNetB7 | 0.9590 ± 0.0026 | 0.9299 ± 0.0037 | 65,355,412 |

| Dataset | Configuration | Encoder | Dice (mean ± std) | IoU (mean ± std) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVC-ClinicDB | DeepColonLab (L) | EfficientNetB2 | 0.9590 ± 0.0038 | 0.9301 ± 0.0046 |

| DeepColonLab (M) | EfficientNetB4 | 0.9583 ± 0.0029 | 0.9289 ± 0.0044 | |

| DeepColonLab (H) | EfficientNetB6 | 0.9597 ± 0.0060 | 0.9314 ± 0.0084 | |

| CVC-ColonDB | DeepColonLab (L) | EfficientNetB2 | 0.9379 ± 0.0098 | 0.9019 ± 0.0105 |

| DeepColonLab (M) | EfficientNetB4 | 0.9385 ± 0.0189 | 0.9031 ± 0.0199 | |

| DeepColonLab (H) | EfficientNetB6 | 0.9397 ± 0.0101 | 0.9043 ± 0.0112 | |

| Kvasir | DeepColonLab (L) | EfficientNetB2 | 0.9260 ± 0.0064 | 0.8830 ± 0.0082 |

| DeepColonLab (M) | EfficientNetB4 | 0.9318 ± 0.0059 | 0.8902 ± 0.0075 | |

| DeepColonLab (H) | EfficientNetB6 | 0.9302 ± 0.0070 | 0.8885 ± 0.0087 |

| Work | Year | Dataset | Dice | Jaccard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PraNet [13] | 2020 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.899 | 0.849 |

| CVC-ColonDB | 0.709 | 0.640 | ||

| Kvasir | 0.898 | 0.840 | ||

| SANet [20] | 2021 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.916 | 0.859 |

| CVC-ColonDB | 0.753 | 0.670 | ||

| Kvasir | 0.904 | 0.847 | ||

| Polyp PVT [19] | 2021 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.937 | 0.889 |

| CVC-ColonDB | 0.808 | 0.727 | ||

| Kvasir | 0.936 | 0.949 | ||

| ColonFormer [22] | 2022 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.934 | 0.884 |

| CVC-ColonDB | 0.811 | 0.733 | ||

| Kvasir | 0.927 | 0.877 | ||

| HarDNet-MSEG [21] | 2021 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.932 | 0.882 |

| CVC-ColonDB | 0.731 | 0.660 | ||

| Kvasir | 0.912 | 0.857 | ||

| Cun Xu et al. [29] | 2024 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.953 | 0.975 |

| Kvasir | 0.923 | 0.954 | ||

| He Xue et al. [28] | 2024 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.9471 | 0.9021 |

| Kvasir | 0.9390 | 0.8907 | ||

| Shiyu Xiang et al. [30] | 2024 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.9328 | 0.8742 |

| Kvasir | 0.8882 | 0.7988 | ||

| Gangrade et al. [31] | 2024 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.955 | 0.912 |

| Kvasir | 0.975 | 0.962 | ||

| ContourNet [27] | 2024 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| CVC-ColonDB | 0.99 | 0.98 | ||

| Kvasir | 0.97 | 0.95 | ||

| Jianuo Liu et al. [26] | 2024 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.9438 | 0.8996 |

| Kvasir | 0.9166 | 0.8564 | ||

| HiFiSeg [24] | 2025 | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.942 | 0.897 |

| CVC-ColonDB | 0.826 | 0.749 | ||

| Kvasir | 0.933 | 0.886 | ||

| DeepColonLab (Ours) | CVC-ClinicDB | 0.9597±0.0060 | 0.9314±0.0084 | |

| CVC-ColonDB | 0.9397±0.101 | 0.9043±0.112 | ||

| Kvasir | 0.9318±0.0059 | 0.8902±0.0075 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).