1. Introduction

Land serves as the foundational resource for human survival and development, supporting critical ecosystem services such as soil and water conservation, habitat protection, and climate regulation [

1,

2]. However, the accelerating pace of contemporary urbanization, particularly in rapidly developing regions such as the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area in China, has precipitated dramatic land-use transformations that threaten ecological stability while fueling economic growth [

3,

4,

5]. In Guangzhou, a megacity at the heart of this region, urban expansion has consumed significant portions of arable and forest lands since 2000, degrading ecosystem service values (ESV) and intensifying conflicts between development needs and environmental protection [

3,

6,

7]. Such trade-offs exemplify a global challenge: how to optimize land-use allocation to balance economic prosperity with ecological sustainability - a dilemma exacerbated by conventional planning approaches that prioritize short-term gains over long-term resilience.

Land use optimization has evolved as a critical interdisciplinary field at the intersection of economics, human geography, and landscape ecology, progressively incorporating more sophisticated approaches to address complex urban planning challenges [

8,

9,

10]. The quest for sustainable land-use solutions has driven significant methodological evolution, from early qualitative models to advanced spatial-quantitative frameworks. Foundational work by Forman and Godron [

11] established key concepts of landscape pattern optimization through their influential “centralization-decentralization” model, while Dokmeci [

12] pioneered the application of linear programming (LP) to land use allocation, introducing much-needed quantitative rigor to planning processes. These theoretical advances were significantly enhanced by the spatial analytical capabilities of Geographic Information Systems (GIS), which facilitated a crucial transition from purely quantitative control to sophisticated spatial optimization. Illustrative applications such as the Boundary-based Fast Genetic Algorithm (BFGA) demonstrated how multi-objective optimization could generate context-specific land use strategies for developing urban areas, though these approaches often lacked integration of eco-economic perspectives in spatial planning frameworks [

13].

The development of land use simulation models, particularly the CLUE (Conversion of Land Use and its Effects) model by Veldkamp and Fresco [

14], and its refined version, CLUE-S, by Verburg et al. [

15], marked a major methodological breakthrough. These models combine empirical land use-driver relationships, dynamic competition modeling, and multi-scenario spatial projections, making them valuable for visualizing land use transitions and assessing planning alternatives [

16,

17]. Their applications across various landscapes, from urban expansion to agricultural land management, demonstrate their versatility but also highlight a key limitation—the reliance on external demand inputs, which restricts their ability to support fully integrated planning [

18,

19,

20,

21].

More recently, Ecosystem Service Valuation (ESV) has emerged as a critical component of land use decision-making, emphasizing the interdependence of ecological and economic systems [

22]. Advances in valuation methodologies [

23] and policy-driven sustainability metrics [

24] have reinforced its importance. Notable applications such as Wang et al.'s [

25] integration of ESV into LP models and Liang et al.'s [

6] ecological-oriented investment optimization frameworks represent important steps forward. However, these approaches often focus on singular ecological benefits while neglecting regional socio-economic dynamics, limiting their applicability across different development stages and geographic settings. This highlights the need for more synthetic approaches that can simultaneously evaluate economic and ecological outcomes across land use types [

26], enabling truly balanced optimization of competing land use demands—an imperative particularly acute for rapidly urbanizing regions facing pressing sustainability challenges.

This study addresses key gaps in land-use research by developing an integrated LP and CLUE-S modeling framework that combines quantitative optimization with spatial simulation to support more effective land-use planning in rapidly urbanizing regions, using Guangzhou as a case study. We implement four policy-oriented scenarios (Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS), Cultivated Protection Scenario (CPS), Economic Development Scenario (EDS), and Balanced Development Scenario (BDS)) to systematically evaluate trade-offs between urban expansion, food security and ecological conservation through 2035. The framework captures regional trade-offs among ecological integrity and urban expansion by incorporating localized ESV coefficients and economic indicators, offering greater contextual accuracy than generalized models [

27,

28]. Policy constraints such as ecological redlines and urban growth boundaries are directly embedded into the simulation, allowing for a realistic representation of how regulations influence spatial dynamics. Furthermore, the model quantifies the downstream effects of land-use changes on landscape connectivity and economic productivity, providing urban planners with practical tools for sustainable decision-making while offering a transferable approach that aligns with UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 11 and 15), representing an important step toward operationalizing ecological civilization principles in urban planning worldwide.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas

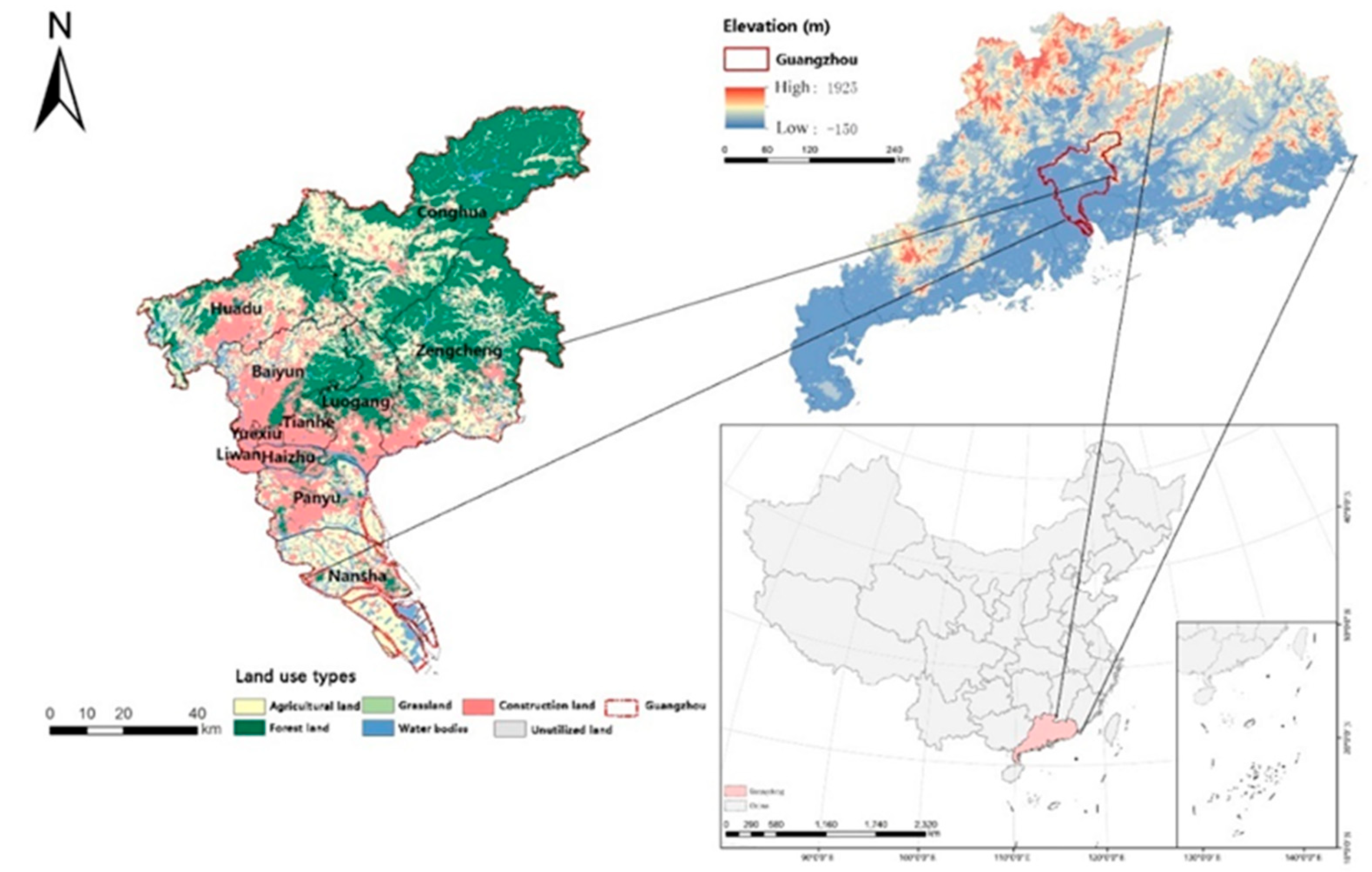

Guangzhou (112°57′–114°3′E, 22°26′–23°26′N), located in southern China at the heart of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, is the largest city in south China and serves as a major economic, political, and cultural hub (

Figure 1). The municipality spans 7,434.4 km2 across 11 administrative districts, including Liwan, Haizhu, Tianhe, Baiyun, Huangpu, Panyu, Huadu, Nansha, Conghua, Zengcheng, and Yuexiu. The city features diverse topography that transitions from mountainous terrain in the northeast (peaking at Tiantangding, 1,210 m) to coastal plains in the south. The city lies at the confluence of Xijiang, Beijiang, and Dongjiang Rivers, forming a dense and well-developed water system.

Guangzhou’s natural geographical advantages have supported its transformation from a traditional agricultural society into a major industrial and urban center, particularly following China’s reform and opening-up policies. The city initially developed labor-intensive industries through regional integration with Hong Kong, forming a “front shop-back factory” model. However, reliance on similar industrial structures and excessive land and environmental exploitation led to inefficient competition and rising pollution levels. Over the past two decades, Guangzhou has actively embraced industrial restructuring, prioritizing high-tech sectors and absorbing industrial transfers from Hong Kong. Between 2000 and 2020, the city’s GDP grew from 237.59 billion yuan to 2,501.91 billion yuan, reflecting an average annual growth rate of 16.58%. Despite this rapid development, Guangzhou continues to face challenges such as environmental degradation, unsustainable land and resource use, imbalanced land-use structures, and growing tensions between human activities and land capacity.

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Land Use Classification

The land use classification for this study was derived from 2020 Landsat TM imagery (30-m resolution) of Guangzhou, following China's national land use classification standard (GB/T 21010-2017). The remote sensing data processing involved several key steps: (1) atmospheric and geometric correction using ENVI software; (2) hybrid classification combining supervised classification with visual interpretation to ensure accuracy; and (3) categorization into six primary land use types: agricultural land, forest land, grassland, water area, construction land, and unutilized land. To facilitate spatial analysis in the CLUE-S model, the processed data were converted to a 200m × 200m grid format using the WGS1984 coordinate system.

2.2.2. Driving Factors

Based on data availability, feasibility, and stability considerations, we selected 12 key spatial driving factors that comprehensively capture the socio-economic and biophysical determinants of land use change. These included both external factor, such as Gross domestic product (GDP), Population density, and Active cropland; and internal environmental factors, including Distance from roads, Distance from inland rivers, Distance from lakes, Elevation, Slope, Undulation, Soil organic matter, Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), and Soil texture (

Figure S1).

The 30-m resolution digital evaluation model (DEM) data, obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud platform, served as the foundation for deriving terrain parameters (e.g., Slope, Elevation, and Undulation). Infrastructure and hydrological data (e.g., roads and rivers) were extracted from OpenStreetMap and BigMap databases, with subsequent calculation of river network density and proximity metrics using spatial analysis tools in ArcGIS 10.8. Soil properties including organic matter content and texture composition were obtained from the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD). Vegetation indices were derived from MODIS Vegetation Index Products to ensure high temporal resolution and global consistency. Socio-economic indicators such as population density, per capita GDP, and the active cropland were compiled from the Statistical Yearbook of Guangzhou. All datasets underwent standardized processing, including spatial interpolation (spline method for socio-economic data) and conversion to 200×200 m raster format (ASCII) to ensure model compatibility.

2.3. Methods

To address the dual challenges of quantitative land demand and spatial allocation, this study integrates a LP model with the CLUE-S model to simulate land use optimization for Guangzhou in 2035 under the four policy scenarios (EPS, CPS, EDS, and BDS). The LP model was used to depict the direction of land use shifts and calculated future land use demands based on ecological and economic objectives, while the CLUE-S model was utilized to allocate the land use demands to spatial distribution under each scenario.

2.3.1. Linear Programming (LP) Model

The LP model was applied to forecast land use demand in Guangzhou for 2035, using 2020 as the baseline year. Two objective functions were defined: maximizing ESV and maximizing economic benefit. Land use constraints and targets were defined for each scenario based on the Master Plan of Land Use in Guangzhou (2006-2020), Master plan of Guangzhou Territorial Space (2021-2035) and Forest projection and utilization plan of Guangdong Province (2021-2035).

The quantitative assessment of ESV was first proposed by Costanza et al. [

29]. Building upon this framework, Xie et al. [

30] refined the method to better align with the characteristics of China's ecosystems and developed a value equivalent factor table specifically tailored for ecosystem service valuation in China. In this study, we adopted this modified approach and adjusted it to account for the regional characteristics of Guangzhou. Based on statistical data such as grain crop yield and sown area in Guangzhou in 2020, and using Equation (1), the economic value of ecosystem services per unit area (

, CNY/ha) was estimated to be 1,146.27 CNY/ ha [

31].

where

is the national average price of the grain crop

i (CNY/t),

is the yield of the

ith grain crop (

t), and

M is the total area of grain crops (ha).

Referring to China’s equivalent value coefficient table for ecosystem services and applying Equation (2), we further calculated the per-unit-area ecosystem service value (

Table S1). Ultimately, the coefficient of ecological benefits for different land use types in Guangzhou were determined (

Table 1).

where

represents the area (ha) of land use type

i in the study region, and

denotes the ecosystem service value per unit area of land use type

i.

- 2.

Coefficient of economic benefit

In this study, we obtained the economic benefit coefficient of each region and calculated the economic benefit coefficient of each land use type by obtaining the output value of the first, second, and third industries recorded in the Guangzhou Statistical Yearbook 2020 and dividing that coefficient by each land use area (

Table 1).

Then the objective functions for ecological and economic benefits were defined as:

where

represents the area of land use type

j;

and

are the coefficients of ecological and economic benefit (

Table 1), respectively.

- 3.

Scenario setting and constraints

Four policy-oriented scenarios were established to reflect distinct development priorities in land use planning. The Ecological Protection Scenario (EPS) aimed to maximize ESV by prioritizing forest and water conservation, with constraints ensuring minimum area thresholds for these land use types. The cultivated Protection Scenario (CPS) focused on safeguarding agricultural land to support food security, imposing strict limitations on the conversion of farmland. The economic Development Scenario (EDS) emphasized urban expansion to stimulate economic growth, permitting higher allocations of construction land within predefined boundaries. Finally, the balanced Development Scenario (BDS) sought to achieve a compromise among ecological preservation, agricultural production, and urban development by applying moderate constraints across all land use categories.

Each scenario incorporates specific constraints on land use conversions and target values for ecosystem services and economic indicators, allowing for systematic comparison of trade-offs between different development pathways. The BDS scenario was used as a reference, with its ecological and economic targets reflecting average growth trends, and other scenarios were adjusted accordingly. Detailed constraints for other scenarios are specified in

Table S2.

Guangzhou's rapid urbanization over the past two decades has led to substantial conversion of agricultural land to urban construction land, creating significant food security challenges as the remaining agricultural land can no longer support the growing population's needs. Drawing from Guangzhou’s territorial spatial planning and historical land use trends, we established critical land use constraints to guide sustainable development: maintaining at least 1,287.99 km2 of agricultural land for food security, preserving over 418 km2 of water areas for ecological protection, capping urban land at 1,772 km2 to control sprawl, while conserving the 2020 forest land baseline of 2,914.81 km2. The total optimized area was maintained at Guangzhou's administrative size of 7,072.36 km2.

- 4.

Objective function solving

The optimization model (Equations (3) and (4)) was implemented using the linprog function in MATLAB 7.01 to solve the multi-objective linear programming problem. Taking the EPS scenario with economic objective as an example, we introduced a constraint requiring the total ESV to exceed the baseline levels by at least 3%, thereby guaranteeing a harmonious balance between ecological conservation and economic development. The LP model was formulated as follows:

Subject to ecological constraint (ensure ESV exceeds threshold)

where to represent the land use areas (km2) allocated to agricultural land, forest land, grassland, water area, construction land, and unutilized land, respectively.

2.3.2. CLUE-S Model

The CLUE-S model was used to simulate the spatial allocation of land use types by combining ecological and socio-economic driving factors [

32,

33]. The spatial distributions of the land-use types are quantified by using a binomial logit model with the percentages of the types as the dependent variables and 12 socio-economic and biophysical driving factors (

Figure S1) as the independent variables. The probabilities of the conversion of land use type were defined by using the following logistic model:

where

is the probability of the land use type

i occurring in a grid cell;

Xi are the driving factors; and

represents the logistic regression coefficient of this driving factor. The quantitative relationships between driving factors and land use patterns were analyzed using SPSS software (

Table S3 and

Figure S2). The reliability of these correlations was assessed through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves, with all values exceeding the 0.75 threshold. This confirms that the dataset meets regression requirements, and the selected driving factors are statistically valid for regional modeling applications.

The specific conversion settings of the six land use types affect the temporal dynamics of the simulation, which are composed of two parameters: the transition matrix and the conversion elasticity (ELAS). The value for the first parameter, transition matrices, adopt binary values: “1” indicates permissible transitions between corresponding land use types, while “0” designates prohibited conversions. Based on a systematic analysis of both current land use patterns and projected development trajectories in the study region, transition matrices were established for each scenario as showed in

Table S4-S7. The second parameter, which ranges from 0 (easy conversion) to 1 (irreversible change), is determined on the basis of expert knowledge and observed behavior in recent years (

Table S8).

The CLUE-S model operates in discrete time steps and uses conversion rules to simulate demand for all patterns and the most likely changes in the different types on the basis of Equation (5). For each grid

i, the total probability of land use type

u (

) was calculated according to the following equation:

where

is the spatial probability derived from logistic regression;

is the conversion elasticity coefficient; and

is the iterative adjustment term.

2.3.3. Landscape-Scale Graph Metrics Selection

Landscape indices are well-established quantitative tools for characterizing landscape patterns, as they effectively capture both structural composition and spatial configuration features while enabling temporal monitoring of landscape dynamics [

34,

35]. Building upon these fundamental landscape ecology principles, our study systematically selected seven representative indices at both patch and landscape levels to quantitatively assess the spatial configuration characteristics of Guangzhou's urban landscape under various development scenarios (

Table S9).

2.3.4. Model Validation

The overall simulation accuracy was evaluated using the Kappa statistic. The Kappa index, which quantitatively measures the consistency between simulated and observed land use, is defined as follows:

where

represents the perfect agreement under ideal conditions,

is the expected agreement by chance, and

is the observed proportion of correct simulations.

Using 2010 land use data and predefined driving factors as inputs, we employed the CLUE-S model to simulate optimal land use allocation for Guangzhou in 2015. The simulation demonstrated strong consistency with the actual land use distribution, achieving an overall accuracy of 82.11% (146,921 correctly simulated grid cells out of 178,924 total). The Kappa coefficient of 0.785 further confirms the model's reliability, surpassing the widely accepted threshold of 0.75 for satisfactory agreement. These validation results demonstrate that the parameter configuration provides a robust foundation for future land use simulation studies in Guangzhou.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Optimization Pattern of Land Use Under Different Scenarios

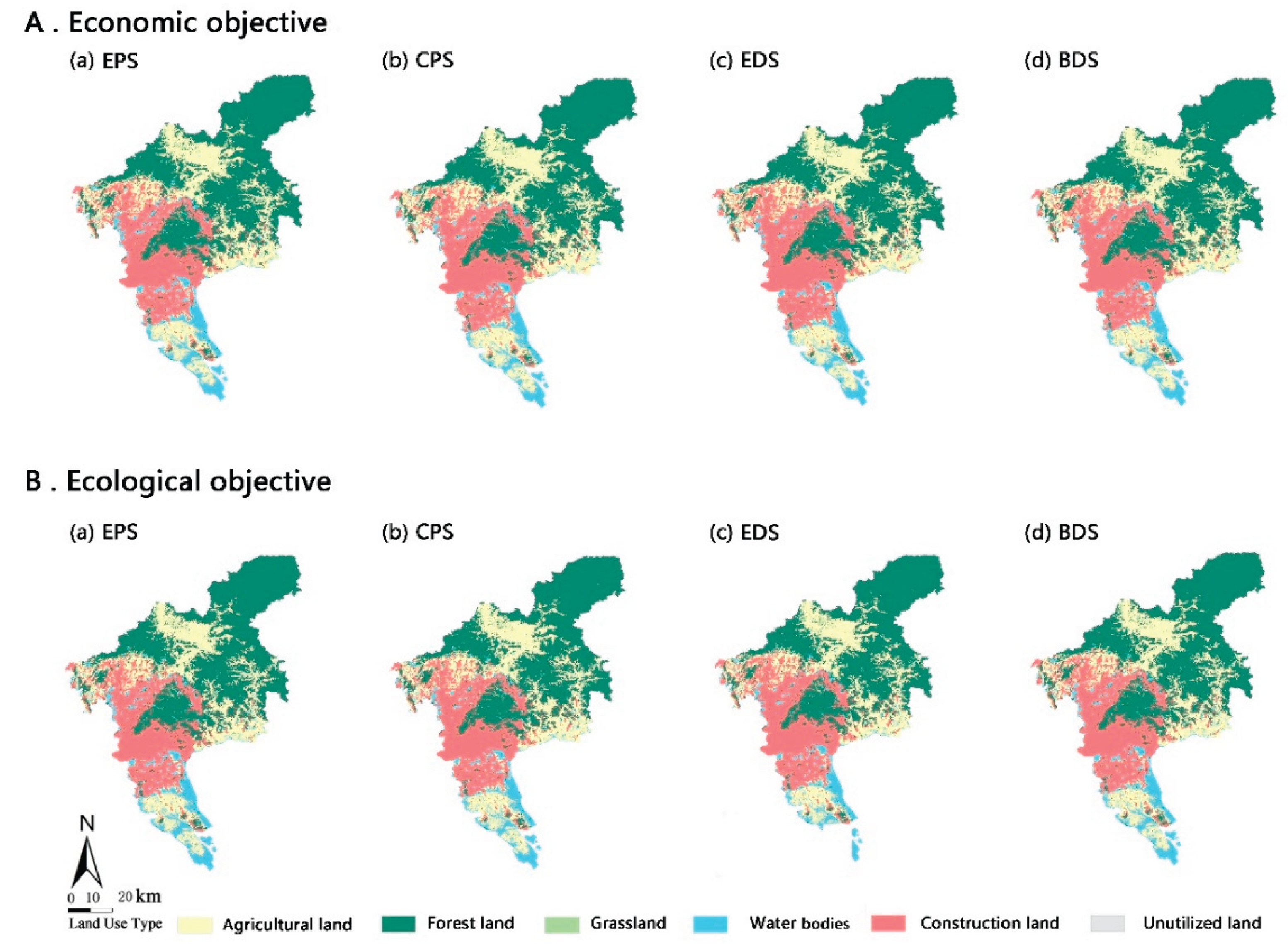

Land use structure optimization results under each scenario were input as demand data into the CLUE-S model, which, combined with various driving factors and conversion constraints, simulated spatial allocations. The optimal land use configuration for Guangzhou in 2035 varied across the four scenarios, reflecting differences in ecological and economic objectives (

Figure 2) and land use types (

Table 2). In addition, to evaluate the accuracy of the simulation results, land use transition matrices for the EPS under ecological objective and the EDS under economic objective were compared with the 2020 baseline land-use conditions. The corresponding transition matrices are presented in

Tables S10 and S11, and the spatial distribution of land conversion is shown in

Figure S3. The results indicate that the differences between the optimized land use areas and the predefined demand targets were minimal, confirming the reliability and consistency of the model's simulation performance.

For the EPS under the ecological objective, the area of water bodies is projected to reach 554.41 km

2, largely due to the implementation of ecological protection measures. Major increases are observed in Panyu, Nansha, and the junction between Huadu and Baiyun districts (e.g., Liuxi River, Hongqi Asphalt Road, Jiaomen Waterway, and Humen Waterway) (

Figure 2). The expected rise in water bodies was projected to further optimize the flood diversion and detention system of the water network, characterized by north storage, middle drainage, and south drainage. Additionally, it would achieve a balance between regulation and storage, reserve storage and buffer, and functional integration.

Construction land increases under all scenarios for ecological objective when compared to 2020, with the greatest expansion (1,642.68 km2) occurring under the EDS. This growth is primarily driven by the conversion of agricultural land and expansion of existing urban areas, particularly in the central city and Nansha District. The expansion of construction land would provide a foundation for industrial development, accelerate the growth of China-Singapore Knowledge City and Nansha Science City, and promote the construction of the Sci-tech innovation corridor linking Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong and Guangzhou–Zhuhai–Macao Nansha District. Simultaneously, construction land would expand on its original foundation, while scattered residential areas would be converted into forest land or agricultural land to facilitate the integrated development of urban and rural areas.

The relationships between the four scenarios under economic objective follow similar patterns. Lateral comparison of the two objectives revealed that the areas and spatial distributions of agricultural land, grassland, and unutilized land were comparable. The primary differences lay in the changes to forest land, construction land, and water bodies, as these land-use types generate greater ecological value than others, while construction land yields higher economic value. Consequently, depending on whether the focus was on ecological or economic objectives, the simulation process prioritized specific land use classes to meet transformation conditions and maximize target outcomes.

3.2. Comparison of Eco-Economic Value Under Different Scenarios

The ESV and economic benefit for Guangzhou in 2035 were quantitatively assessed under different objectives and scenarios using ESV equivalent factor and land-based per capita GDP, respectively, to reflect ecological and economic outcomes (

Table 3). Under ecological objective, all scenarios achieved varying degrees of improvement in ESV compared to the 2020 baseline. The EPS generated the highest ESV at 172.76 × 10

8 CNY, marking a 9.85% increase, followed by the BDS at 165.98 × 10⁸ CNY (+5.53%), EDS at 163.65 × 10⁸ CNY (+4.05%), and CPS at 163.51 × 10⁸ CNY (+3.96%). Although EDS did not yield the highest ecological value, it produced the highest economic benefit among the ecological-objective scenarios at 18,462.24 × 10⁸ CNY, representing an 11.86% increase compared to 2020. This indicates that substantial economic gains can still be achieved under ecologically oriented planning through effective spatial optimization. In contrast, under economic objective, land use configurations favored urban expansion, resulting in significantly higher economic benefits. EDS delivered the greatest economic return, reaching 19,853.08 × 10⁸ CNY, a 20.29% increase over the baseline. BDS and EPS followed closely with benefits of 19,539.38 × 10⁸ CNY (+18.39%) and 19,209.66 × 10⁸ CNY (+16.39%), respectively, while CPS reached 19,136.46 × 10⁸ CNY (+15.95%). However, improvements in ESV under economic objectives were relatively limited. The EPS achieved the highest ESV (162.27 × 10⁸ CNY; +3.18%), followed by BDS (158.64 × 10⁸ CNY; +0.87%), EDS (157.45 × 10⁸ CNY; +0.03%), and CPS (157.31 × 10⁸ CNY; +0.02%).

These findings confirm that although economic objective can drive higher GDP growth, they offer limited improvements in ecological value. In contrast, the BDS under ecological objective delivers the high ecological outcomes with balanced economic gains, while the EPS under economic objective provides a promising compromise that ensures ecological security without undermining economic performance. Thus, these two scenarios emerge as the most practical and sustainable options for rapidly urbanizing cities like Guangzhou in future development. The results support the use of integrated simulation approaches for guiding land use policy under rapid urbanization and complex eco-economic constraints.

3.3. Landscape Pattern Analysis Under Different Scenarios

Landscape pattern indices were employed to assess spatial structure, composition, and ecological integrity under each scenario. These include both patch-level metrics, such as proportion of landscape (PLAND), largest patch index (LPI), and aggregation index (AI); and landscape-level metrics, including landscape shape index (LSI), Shannon’s diversity index (SHDI), Shannon’s evenness index (SHEI), and Connectance index (CONNECT).

3.3.1. Landscape Pattern Dynamics at the Patch Level

Table 4 displays the changes in patch-level landscape indices for different land use types in 2020 and their projected values in 2035 under both ecological and economic objectives. Among all land use types, agricultural land exhibited the most pronounced changes. Under the economic objective, its PLAND is projected to reach 23.3680% in the EPS and 24.7496% in the CPS, reflecting a notable decline from the 2020 level. In contrast, forest land, owing to its high ecological and economic value, shows a consistent increase in PLAND across all scenarios, with the highest value of 45.6512% observed under the ecological-objective EPS. Construction land is projected to expand under all scenarios due to development pressure, with its PLAND reaching 24.7647% under the economic-objective EDS. Meanwhile, the PLAND of grassland and unutilized land remains relatively stable, given their limited ecological and economic contributions.

For agricultural land, LPI is projected to decrease across scenarios, while AI increases, indicating that although large continuous patches are being reduced, the remaining agricultural land becomes more spatially aggregated. This change is driven by the conversion of scattered or marginal farmland into other land-use types, while new agricultural areas are more compactly distributed. In the case of construction land, both LPI and AI increase significantly under all simulations, especially under the EDS. This suggests a trend toward concentrated urban growth, with the emergence of sub-centers and enhanced spatial cohesion. Overall, these changes reflect the contrasting landscape restructuring processes under ecological and economic planning objectives.

3.3.2. Landscape Pattern Dynamics at the Landscape Level

At the landscape level, four indies (i.e., LSI, SHDI, SHEI, and CONNECT) were used to evaluate fragmentation and structural complexity (

Table 5). The LSI reflects the degree of dispersion or aggregation of patches, and higher values indicate greater fragmentation. By 2035, the LSI values across all scenarios are lower than those in 2020, suggesting a reduction in landscape fragmentation. This indicates a trend toward more regular patch shapes and less anthropogenic disturbance, which is beneficial for habitat integrity and species reproduction. Consequently, urban development is projected to become more spatially ordered.

For the landscape diversity, both the SHDI and SHEI exhibited consistent trends. Higher SHDI values indicate greater land use richness and heterogeneity, is often associated with increased fragmentation. Compared to 2020, the SHDI and SHEI values are projected to change only slightly by 2035, indicating that landscape heterogeneity remains relatively stable or declines slightly. The results indicate that through CLUE-S model simulations, scattered patches of agricultural and construction land are reallocated into more cohesive land-use types, thereby improving overall land use efficiency. Furthermore, the CONNECT index reveals enhanced landscape connectivity and spatial cohesion compared to the 2020 baseline.

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy Implications of Scenario-Based Land Use Optimization

The simulation results reveal that Guangzhou’s future land use trajectory is highly sensitive to the policy orientation embedded in scenario design. Each scenario produced markedly different spatial and functional outcomes, underscoring the crucial role of integrated planning in achieving sustainable development. Notably, under the EPS, forest land expanded to 3,232.45 km², primarily through conversion from agricultural and construction land, particularly in ecologically important zones such as Conghua and Huadu Districts. This expansion aligns with Guangzhou's ecological conservation goals but comes at the cost of reduced agricultural land, which may threaten regional food security.

Conversely, the EDS prioritized urban expansion, with construction land increasing to 1,786.11 km

2, surpassing the allowable development boundary (1,772 km

2). This scenario generated the highest increase in economic output (20.29%) but simultaneously caused severe landscape fragmentation, as reflected by the elevated

LSI value (33.67) and the decline in landscape connectivity (

Table 5). These outcomes suggest that unrestrained urbanization, while beneficial economically in the short term, compromises long-term ecological sustainability.

The BDS, in contrast, demonstrated the strongest potential for achieving multiple planning objectives. With moderate gains in both economic output (18.39%) and ecosystem service value (5.53%), this scenario preserved key ecological corridors and high-quality agricultural land while supporting compact urban growth. Such results reinforce the argument that scenario-based simulations can effectively illuminate trade-offs and inform spatial strategies that promote synergistic outcomes. These findings are consistent with the broader literature advocating for integrated land use frameworks that accommodate ecological constraints within development planning [

36,

37,

38].

4.2. Landscape Pattern Dynamics and Spatial Mechanisms of Change

The landscape pattern analysis revealed distinct spatial dynamics under each scenario, providing insights into the mechanisms driving land use change. Under the EPS, forest land not only increased in quantity but also exhibited improved aggregation (

LPI = 29.63) and enhanced connectivity (

Table 4 and 5), particularly in the northern mountainous and riparian areas (

Figure 2). These improvements stem from the protection of ecological corridors and the restoration of water bodies, with total water area expanding to 554.41 km

2. While these spatial shifts are consistent with ecological objective, emphasizing the importance of large, contiguous habitat patches for biodiversity conservation [

39,

40]. However, they came at the cost of displacing urban growth into agriculturally valuable areas, revealing a classic ecological-agricultural trade-off.

In contrast, the EDS significantly altered the spatial composition and configuration of land use by converting large areas of agricultural and forest land into construction land. This scenario yielded the higher SHDI values (

Table 5), indicating increased land use heterogeneity. However, the concurrent reduction in functional connectivity and the elevated LSI suggest that such fragmentation may reduce ecological resilience and compromise landscape function, particularly in peri-urban zones where patch cohesion is critical.

The BDS emerged as the most spatially optimized scenario, achieving a delicate balance between land use intensity and ecological coherence. It maintained relatively low landscape fragmentation and the higher CONNECT index, signaling effective retention of structural connectivity among ecological patches. These results underscore the need to consider both compositional aspects (e.g., land use proportions) and configurational characteristics (e.g., patch arrangement) in landscape planning, rather than focusing solely on the total area of land-use types. Policies focused solely on expanding total forest land without addressing spatial configuration may fall short in achieving biodiversity or climate adaptation goals [

41,

42].

4.3. Practical Recommendations for Sustainable Land Use Planning

Based on the simulation results for Guangzhou under different land use scenarios, differentiated planning strategies should be adopted to support sustainable territorial development. Under the EPS, it is essential to enhance the conservation of key water resource areas, increase afforestation efforts, and optimize the spatial distribution of existing agricultural land and construction land. Priority should be given to restoring ecologically sensitive zones by converting marginal agricultural land to ecological land. In the CPS, given that Guangzhou's grain self-sufficiency rate remains low (approximately 30%), expanding agricultural land area is constrained. Therefore, efforts should focus on consolidating fragmented construction land in suburban areas, promoting land reclamation and “village-in-city” renovation, improving agricultural land quality, and enhancing rural spatial structure. These measures can help mitigate the land-use conflict between agriculture and urbanization while improving the overall rural environment. Under the EDS, strategies should emphasize improving land development intensity, enhancing the efficient use of existing construction land, and curbing urban sprawl. Compact urban growth and vertical development can alleviate pressure on ecological and agricultural land. In the BDS, land use planning should aim to harmonize ecological, agricultural, and urban functions by ensuring a more proportionate spatial allocation of ecological land, agricultural land, and construction land. This approach can help optimize landscape structure and support coordinated regional development.

Since the implementation of the Guangdong Province general land use plan, urban expansion in the Pearl River Delta, particularly in Guangzhou, has accelerated significantly. The strategic development of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area has further fueled the demand for construction land. However, given spatial constraints, Guangzhou must avoid inefficient and unutilized land use by strengthening land consolidation and fully implementing the “Three Old” renovation policy (i.e., old towns, old factories, and old villages). We recommend controlling the total scale of urban land, delineating strict urban growth boundaries, and establishing flexible and rigid land use control zones across short-, medium-, and long-term horizons, aligned with the goals of integrated regional development in the Greater Bay Area.

Finally, it is critical to enforce the protection of permanent basic agricultural land and ecological redlines, promote internal urban greening, return ecologically unsuitable agricultural land to forest or other ecological land, and adopt stringent protection measures for rivers and drinking water source areas to prevent further reduction in their spatial extent. These spatial governance measures are necessary to ensure long-term ecological security and sustainable land use in Guangzhou.

4.4. Implications and Limitations

Land use optimization that balances ecological and economic development is inherently interdisciplinary, requiring the integration of diverse fields, expertise, and methodological approaches. The primary innovation of this study lies in the development of a comprehensive framework that combines the CLUE-S spatial allocations model with LP optimization, grounded in the principles of sustainable land planning. By integrating a mathematical optimization model with GIS-based spatial analysis, this method addresses the limitations of each in demand forecasting and spatial allocation. Through the incorporation of both ecological and socio-economic factors, the CLUE-S model was employed to simulate land use dynamics under multiple policy scenarios. The results demonstrated that the synergy between the CLUE-S and LP models offers a more effective means of capturing land use change processes in rapidly urbanizing regions. This integrated approach provides valuable theoretical insights and a robust technical foundation for guiding ecological protection, urban development, and land use optimization in fast-growing urban areas.

While the coupled CLUE-S and LP framework provides valuable insights into Guangzhou’s potential land use trajectories, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the model relies on static driver assumptions and does not fully capture feedback mechanisms between land use change and socio-economic dynamics. As such, potential changes in population distribution, employment structure, or infrastructure investments are not reflected in the simulations, potentially limiting their predictive accuracy. Second, the exclusion of environmental uncertainties, particularly climate change impacts, represents a critical omission. Sea-level rise, extreme weather events, and hydrological shifts could significantly reshape the feasibility and desirability of certain land uses, especially in low-lying regions such as Nansha District. Integrating climate risk assessments and adaptive capacity metrics into future models would enhance the realism of scenario planning. Third, the current study focused primarily on intra-city dynamics, without accounting for cross-boundary land use interactions within the broader Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Regional connectivity, resource sharing, and institutional coordination are likely to influence land development patterns at the metropolitan scale. Incorporating multi-scalar spatial interactions would provide a more comprehensive basis for planning in mega-urban regions. Finally, while the study touched on ESV changes, it did not quantify other critical ecosystem functions such as biodiversity maintenance, carbon storage, or hydrological regulation in a spatially explicit way. Future research should expand the evaluation framework to include these dimensions, ideally through dynamic coupling of land use models with ecosystem process models and participatory scenario co-creation with stakeholders. This would support the development of more adaptive, inclusive, and ecologically grounded land use strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study developed an integrated land use optimization framework by coupling the CLUE-S model with LP model to simulate spatial patterns and evaluate eco-economic trade-offs under different policy-driven scenarios in Guangzhou. By considering ecological policy constraints, economic development demands, and spatial planning regulations, we successfully simulates landscape pattern changes and regional development benefits under four policy scenarios (EPS, EDS, BDS, and CPS), demonstrating how varying spatial configurations of land use generate distinct ecological and economic benefits. The results demonstrate that land use patterns and regional benefits in 2035 vary significantly across scenarios. Under ecological objective, the EPS significant improved forest connectivity and increased ESV by 9.85%, though at the expense of agricultural land. Under economic objective, the EDS maximized economic benefit (20.29%) but also resulted in increased landscape fragmentation and ecological degradation. The CPS successfully preserved agricultural land to support food security, but this led to a reduction in ecological benefits due to urban expansion into environmentally sensitive areas. In contrast, the BDS achieved a more balanced outcome, yielding a 0.87% improvement in ESV and an 18.39% increase in GDP while maintaining overall landscape connectivity and reducing fragmentation. Notably, the BDS under ecological objectives and the EPS under economic objectives emerged as the most effective pathways for promoting sustainable urban development, offering a reasonable balance between environmental protection and economic growth.

The combined LP–CLUE-S model overcame limitations of individual models by integrating demand forecasting with spatial allocation, providing a robust tool for land use decision-making. This integrated modeling approach offers valuable theoretical and technical support for strategic land use planning and policy formulation in rapidly urbanizing regions. Future urban development in fast-growing cities like Guangzhou should be guided by adaptive, scenario-based planning strategies that respect ecological thresholds, prioritize compact urban forms, and balance competing land use priorities to ensure long-term regional sustainability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Maps of the driving forces in the study region; Figure S2: Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) distribution of land use types and driving factors; Figure S3: Spatial distribution of land use conversion in Guangzhou; Table S1: Ecosystem service value coefficient for Guangzhou City; Table S2: Four simulation scenarios with constraint conditions under two optimization objectives; Table S3: Logistic regression coefficient of driving factors; Table S4: Transition matrix under the EPS; Table S5: Transition matrix under the CPS; Table S6: Transition matrix under the EDS; Table S7: Transition matrix under the BDS; Table S8: Elasticity coefficient of land use conversion under different scenarios; Table S9: Landscape pattern indexes and meanings; Table S10: Land use transition matrix of the EPS under ecological objectives in 2020 and 2035; Table S11: Land use transition matrix of the EDS under economic objectives in 2020 and 2035.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and J.W.; methodology, M.Z.; software, B.L.; validation, Q.G., formal analysis, S.Y.; investigation, L.Y.; data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China, grant number 2024A04J3347; Young Talent Project of GDAS, China, grant number 2023GDASQNRC-0217; GDAS' Project of Science and Technology Development, China, grant number 2024GDASZH-2024010102, and 2023GDASZH-2023010104; Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China, grant number 2024A1515030190; and National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42130712.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liburne, L. , Eger, A., Mudge, P., et al. The Land Resource Circle: Supporting land-use decision making with an ecosystem-service-based framework of soil functions. Geoderma 2020, 363, 114134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D. , Xu, Y., Shao, X., et al. Advances and prospects of spatial optimal allocation of land use. Progress in Geography 2009, 28, 791–797. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Q. , Zhang, H., Ye, Y., Yuan, S. Planning strategy of land and space ecological restoration under the framework of man-land system coupling: Take the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area as an example. Geographical Research 2020, 39, 2176–2188. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. , Wu, J., Su, Y., et al. Estimating ecological sustainability in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, China: Retrospective analysis and prospective trajectories. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 303, 114167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. , Chen, S., Gao, L., et al. Spatiotemporal evolution and impact mechanism of ecological vulnerability in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 157, 111214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J. , Zhong, M., Zeng, G., Chen, G., Hua, S., Li, X., Yuan, Y., Wu, H., Gao, X. Risk management for optimal land use planning integrating ecosystem services values: A case study in Changsha, Middle China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. , Kang, J., Wang, Y. Distinguishing the relative contributions of landscape composition and configuration change on ecosystem health from a geospatial perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 165002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, T. , Mineo, K. Regional sustainability assessment framework for integrated coastal zone management: Satoumi, ecosystem services approach, and inclusive wealth. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 73, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.G. Linking landscape, land system and design approaches to achieve sustainability. J. Land Use Sci. 2019, 14, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehari, A. , Genovese, P.V. A Land Use Planning Literature Review: Literature Path, Planning Contexts, Optimization Methods, and Bibliometric Methods. Land 2023, 12, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.T.T. , Godron, M. Landscape Ecology. John Wiley and Sons Ltd., New York, 1986.

- Dokmeci, V.F. Optimization of central places in an industrial economy. Ann. Reg. Sci. 1975, 9, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K. , Huang, B., Wang, S., Lin, H. Sustainable land use optimization using Boundary-based Fast Genetic Algorithm. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2012, 36, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, A. , Fresco, L.O. Exploring land use scenarios, an alternative approach based on actual land use. Agric. Syst. 1997, 55, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, P.H. , Soepboer, W., Veldkamp, A., Limpiada, R., Espaldon, V., Mastura, S.S. Modeling the spatial dynamics of regional land use: the CLUE-S model. Environ. Manage. 2002, 30, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. , Liu, L., Chen, Z., Zhang, J., Verburg, P.H. Land-use change simulation and assessment of driving factors in the loess hilly region—a case study as Pengyang County. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 164, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiakou, S. , Vrahnakis, M., Chouvardas, D., et al. Land use changes for investments in silvoarable agriculture Projected by the CLUE-S spatio-temporal model. Land 2022, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G. , Yin, C., Chen, X., Xu, W., Lu, L. Combining system dynamic model and CLUE-S model to improve land use scenario analyses at regional scale: A case study of Sangong watershed in Xinjiang, China. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M. , Thornton, P.K., Bernués, A., et al. Exploring future changes in smallholder farming systems by linking socio-economic scenarios with regional and household models. Global Environ. Change 2014, 24, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. , Ren, X., Che, Y., Yang, K. A Coupled SD and CLUE-S Model for Exploring the Impact of Land Use Change on Ecosystem Service Value: A Case Study in Baoshan District, Shanghai, China. Environ. Manage. 2015, 56, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiziridls, D.A. , Mastrogianni, A., Pleniou, M., et al. Improving the predictive performance of CLUE-S by extending demand to land transitions: The trans-CLUE-S model. Ecol. Modell. 2023, 478, 110307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B. , Turner, R.K., Morling, P. Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E. , Barton, D.N. Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerry, A.D. , Polasky, S., Lubchenco, J., et al. Natural capital and ecosystem services informing decisions: From promise to practice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, 7348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. , Guo, H., Chuai, X., et al. The impact of land use change on the temporospatial variations of ecosystems services value in China and an optimized land use solution. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2014, 44, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S. , Wen, Z. Optimization of land use structure to balance economic benefits and ecosystem services under uncertainties: A case study in Wuhan, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindu, M. , Schneider, T., Teketay, D., Knoke, T. Changes of ecosystem service values in response to land use/land cover dynamics in Munessa-Shashemene landscape of the Ethiopian highlands. Sci. Total. Environ. 2016, 547, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulsoontronrat, J. , Ongsomwang, S. Suitable Land-Use and Land-Cover Allocation Scenarios to Minimize Sediment and Nutrient Loads into Kwan Phayao, Upper Ing Watershed, Thailand. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R. , d'Arge, R., de Groot, R., et al. The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G. , Zhen, L., Lu, C., et al. Expert knowledge based valuation method of ecosystem services in China. Journal of Natural Resources 2008, 23, 911–919. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P. , Yang, M., Liu, W. Spatial-temporal changes in ecosystem service values based on land use changes in Dongguan city during 2007-2015. Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation 2020, 40, 250–255. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. , Zhang, S., Huang, Y., et al. Exploring an Ecologically Sustainable Scheme for Landscape Restoration of Abandoned Mine Land: Scenario-Based Simulation Integrated Linear Programming and CLUE-S Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M. , Liu, W., Wang, J., et al. Scenario simulation of ecosystem service value change in Dongguan section of Shima River based on CLUE-S model. Bulletin of Soil and Water Conservation 2021, 41, 152–160. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z. Hu, Z., Yang, X., Yang, J., et al. Linking landscape pattern, ecosystem service value, and human well-being in Xishuangbanna, southwest China: Insights from a coupling coordination model. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 27, e01583.

- Peptenatu, D. , Andronache, I., Ahammer, H., et al. A new fractal index to classify forest fragmentation and disorder. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 1373–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahpari, S. , Allison, J., Harrison, M.T., et al. An integrated economic, environmental and social approach to agricultural land-use planning. Land 2021, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. , Bai, Y., Che, L., et al. Incorporating ecological constraints into urban growth boundaries: A case study of ecologically fragile areas in the Upper Yellow River. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 124, 107436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Wu, J., Tang, H., et al. An urban hierarchy-based approach integrating ecosystem services into multiscale sustainable land use planning: The case of China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106097.

- Fahrig, L. , Watling, J.I., Arnillas, C.A., et al. Resolving the SLOSS dilemma for biodiversity conservation: a research agenda. Biol. Rev. 2022, 97, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szangolies, L. , Rohwäder, M. , Jeltch, F. Single large AND several small habitat patches: A community perspective on their importance for biodiversity. Basic and Applied Ecology 2022, 65, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Leitão, A.B. , Ahern, J. Applying landscape ecological concepts and metrics in sustainable landscape planning. Landscape and Urban Plann. 2002, 59, 65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H. , Huang, Y., Zhou, Y., et al. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Ecosystem Service Values and Topography-Driven Effects Based on Land Use Change: A Case Study of the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).