Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

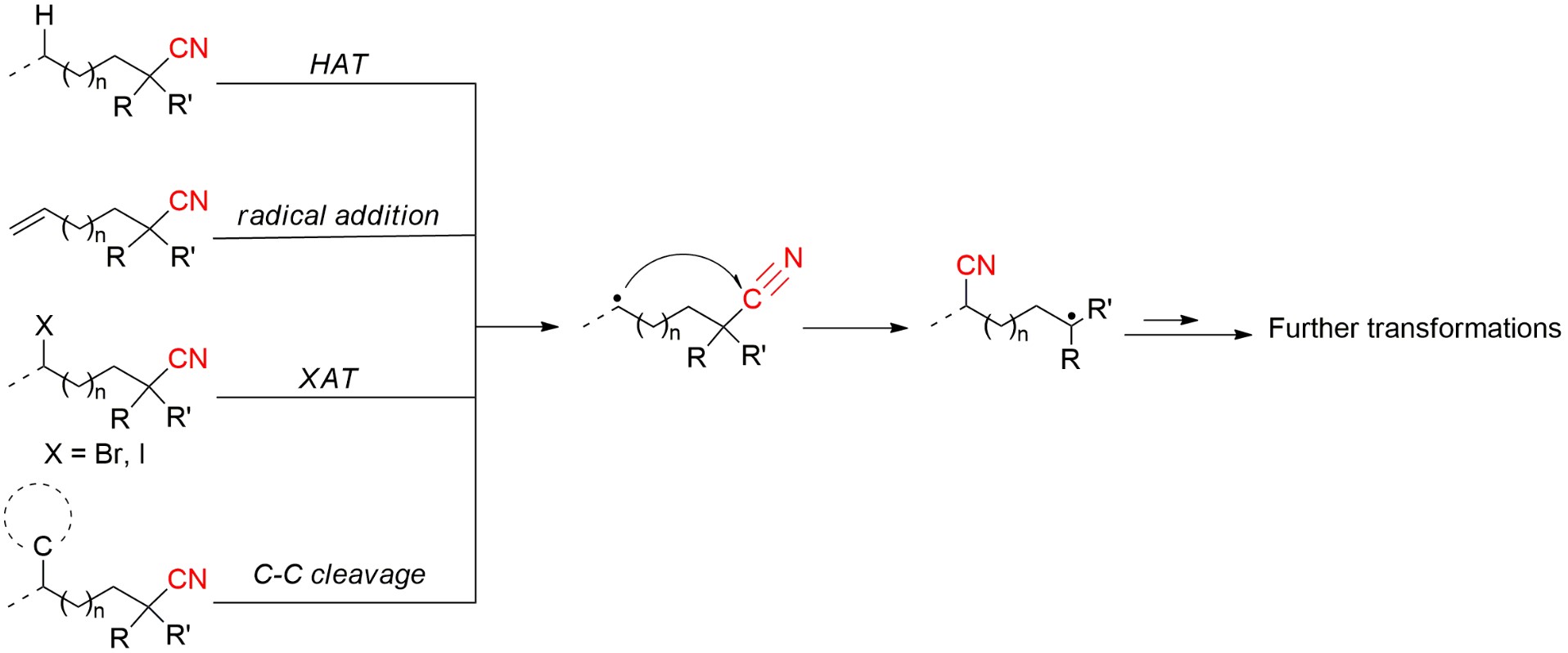

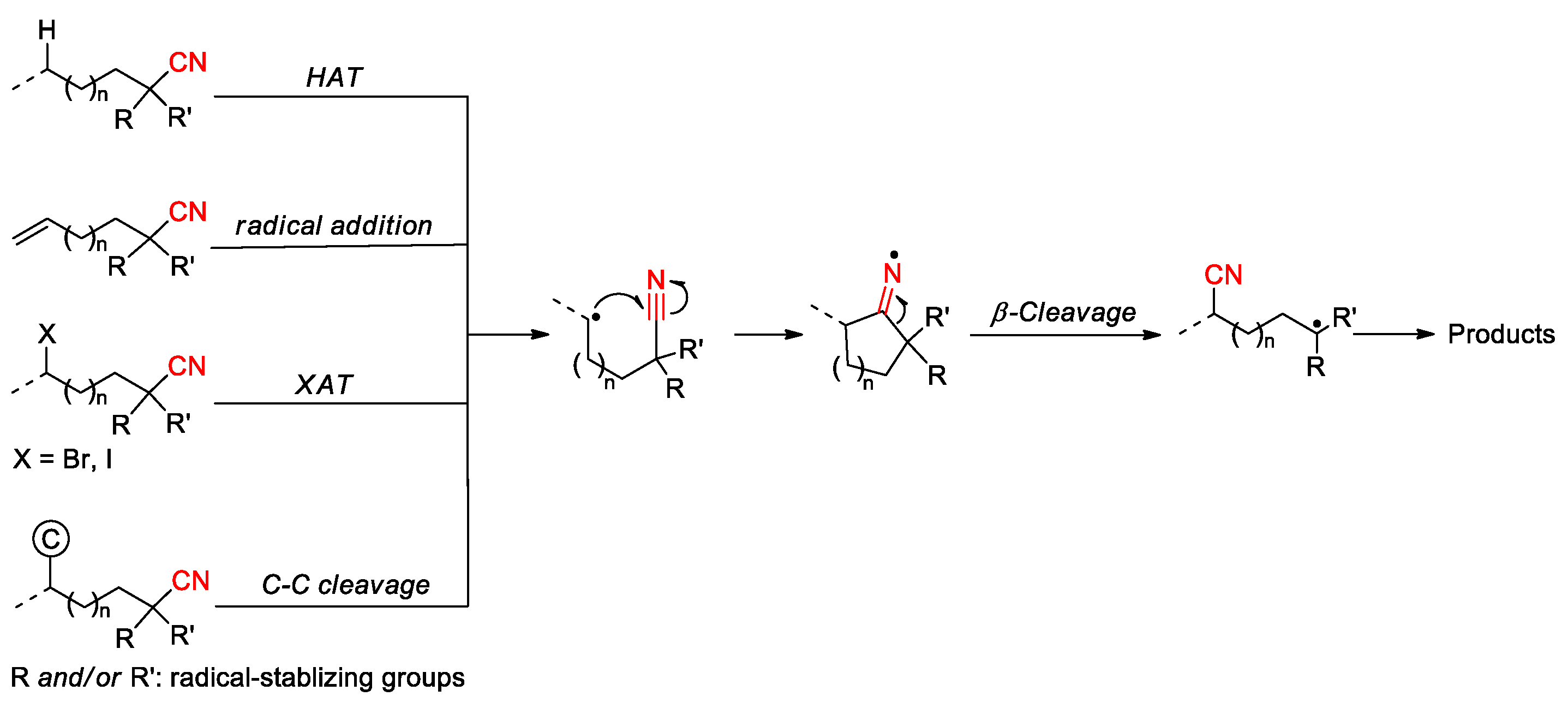

2. Radical-Mediated Translocation of Cyano Groups

2.1. Site Selectivity in CN Migration

2.2. CN Group Translocation via HAT

2.3. Cyano Group Migration via Radical Addition to Unsaturated CC Bonds

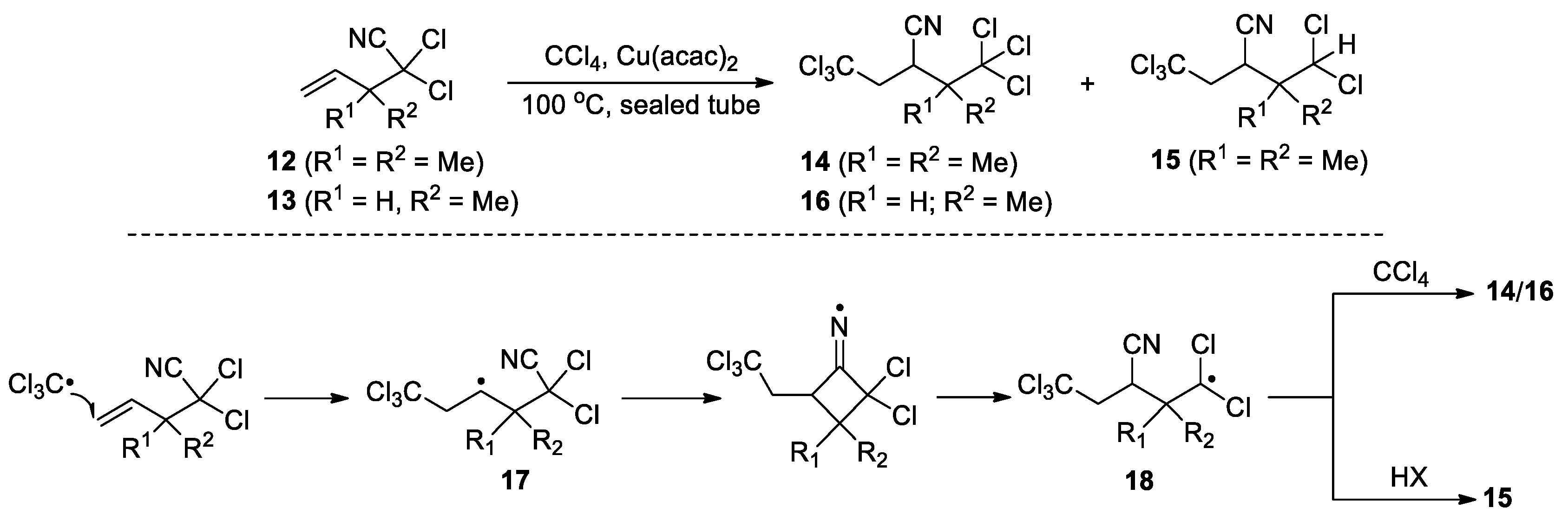

2.3.1. Early Reported Works

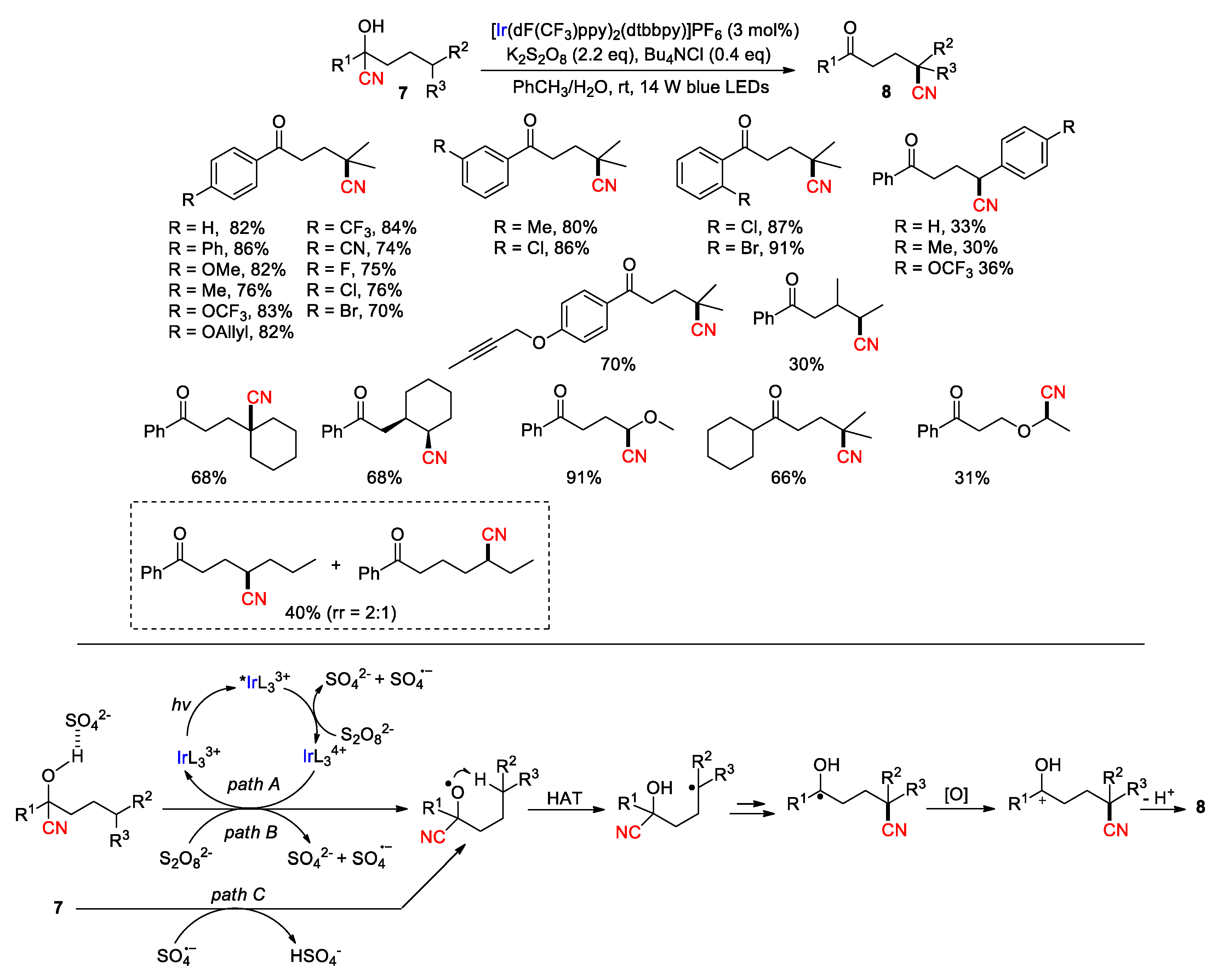

2.3.2. CN Migration with Unsaturated Cyanohydrins

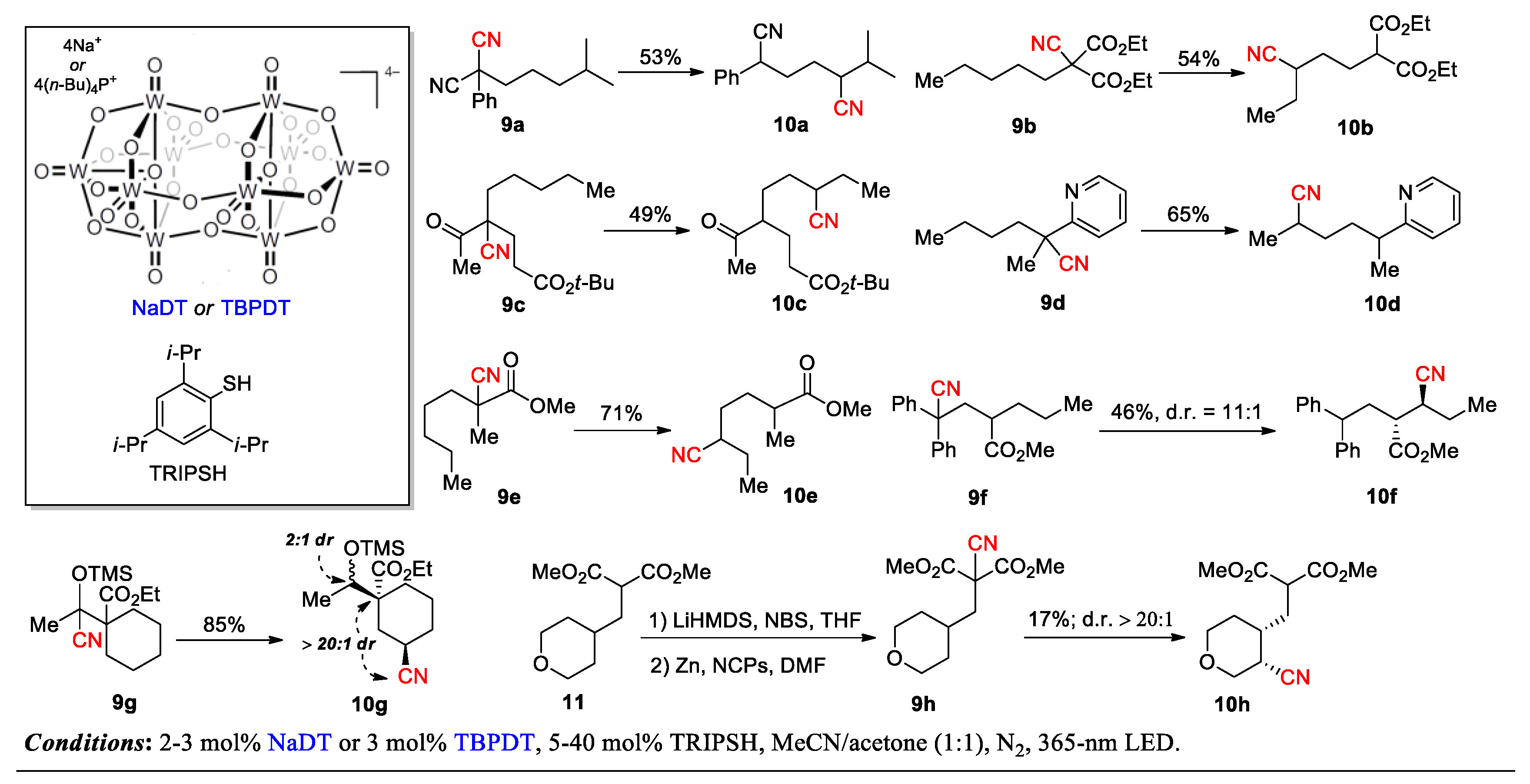

2.3.3. CN Migration with Alkenyl Nitriles

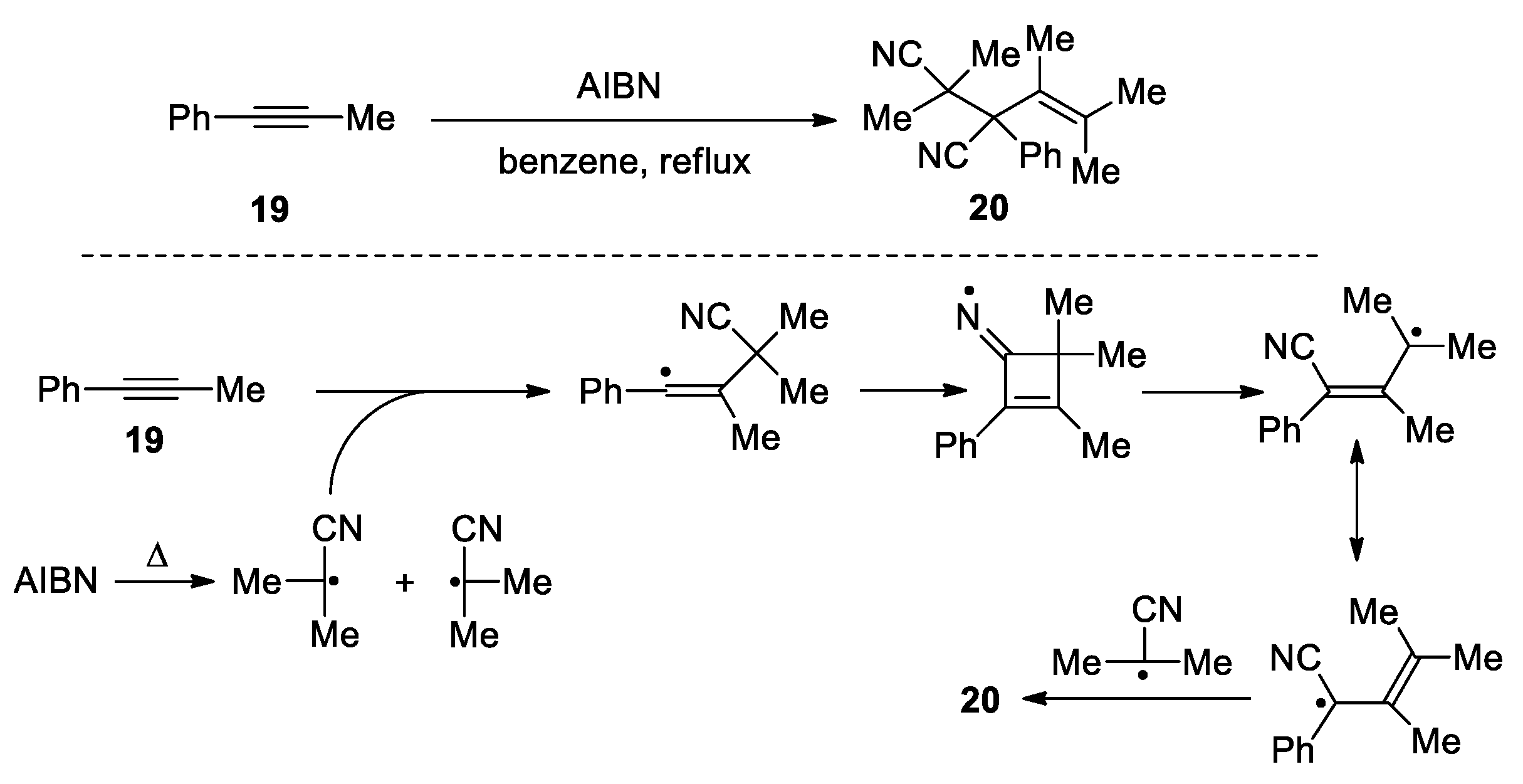

2.3.4. Recently Reported Cyano Migrations Involving Diradical or Radical Cation Intermediates

2.4. Cyano Group Migrations via Halogen Atom Transfer

2.5. Cyano Group Migrations via C-C Bond Fragmentation

3. Conclusions

References

- Seth, A.; Mehta, P.K. The Chemistry of Nitriles, 1st ed.; Seth, A., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wu, W. Recent Advances in Chemical Modifications of Nitriles. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 6658–6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnett, G.J.; Hauck, U.; Hayes, J.J.; Hoffmann, U.; Lohri, B.; Meade, M.; Morawitz, F.; Plesniak, M.P.; Stahr, H.; Veits, J.; Walsh, A. Zogg, A.; Reents, R.; Smith, D.A; Martin, R.E. Development and Demonstration of a High-Volume Manufacturing Process for a Key Intermediate of Dalcetrapib: Investigations on the Alkylation of Carboxylic Acids, Esters, and Nitriles. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2023, 27, 2329–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Qin, J.; Du, X.; Yuan, F.; Zhao, H.; Long, J.; Dong, L.; Chen, J.; Long, Y.; Ma, J. Amorphous Fe0.7Cu0.3Ox as a Bifunctional Catalyst for Selective Hydration of Nitriles to Amides in Water. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 7791–7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshit, A.; Dhara, H.N.; Sahoo, A.H.; Patel, B.K. The Renaissance of Organo Nitriles in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Asian J. 2022, 17, e202200792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Park, K.; Furugen, C.; Jiang, J.; Shimizu, E.; Ito, N.; Sajiki, H. Highly Selective Hydrogenative Conversion of Nitriles into Tertiary, Secondary, and Primary Amines under Flow Reaction Conditions. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, P.V.; Alawaed, A.A. Room Temperature Reduction of Titanium Tetrachloride-Activated Nitriles to Primary Amines with Ammonia-Borane. Molecules 2023, 28, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovela, S.; Karad, S.; Tatipudi, V.V.G.; Arumugam, K.; Somwanshi, A.V.; Muthukumar, M.; Mathur, A.; Tester, R. Synthesis of diversely substituted quinazoline-2,4(1H,3H)-diones by cyclization of tert-butyl (2-cyanoaryl)carbamates. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 6495–6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloumi, M.; Shirini, F. Acidic Ionic Liquid Bridge Supported on Nano Rice Husk Ash: An Efficient Promoter for the Conversion of Nitriles to Their Corresponding 5-Substituted 1H-Tetrazoles and Amides. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202203554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodse, S.K.; Barde, P.D. Catalyst free, one-pot green synthesis of 2-aryl-2-oxazoline derivatives from aryl nitrile using ionic liquid. Syn. Commun. 2023, 53, 1616–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchinetti, V.; Gomes, C.R.B.; de Souza, M.V.N. Application of nitriles on the synthesis of 1,3-oxazoles, 2-oxazolines, and oxadiazoles: An update from 2014 to 2021. Tetrahedron 2021, 102, 132544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, P.; Sreenivasulu, C.; Gorantla, K.R.; Mallik, B.S.; Satyanarayana, G. A simple removable aliphatic nitrile template 2-cyano-2,2-di-isobutyl acetic acid for remote meta-selective C–H functionalization. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 1959–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lýpez, R.; Palomo, C. Cyanoalkylation: Alkylnitriles in Catalytic C-C Bond-Forming Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13170–13184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amancha, P.K.; Lai, Y.J.; Chen, I.C.; Liu, H.J.; Zhu, J.L. Terahedron 2010, 66, 871-877.

- Zhu, J.L.; Huang, P.W.; You, R.Y.; Lee, F.Y.; Tsao, S.W.; Chen, I.C. Total Syntheses of (±)-(Z)- and (±)-(E)-9-(Bromomethylene)-1,5,5-trimethylspiro[5.5]undeca-1,7-dien-3-one and (±)-Majusculone. Synthesis 2011, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.L.; Chou, C.w.; Zhu, J.L.; Tsai, M.H. Access to cyclohexadiene and benzofuran derivatives via catalytic arene cyclopropanation of α-cyanodiazocarbonyl compounds. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 5552–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, Y. Metal-mediated C−CN Bond Activation in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonatto, V.; Lameiro, R.F.; Rocho, F.R.; Lameira, J.; Leitão, A.; Montanari, C.A. Nitriles: an attractive approach to the development of covalent inhibitors. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 14, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Song, C.; Du, Y. Nitrile-containing pharmaceuticals: target, mechanism of action, and their SAR studies. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 11, 1650–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, M.; Nagaraaj, P. Recent developments in dehydration of primary amides to nitriles. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 3792–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Lakshman, M.K. A Simple Synthesis of Nitriles from Aldoximes. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 3079–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.M.; Thadathil, D.A.; Ponmudi, K.; George, A.; Varghese, A. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Synthesis of Nitriles: A Sustainable Approach. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202200081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, K.; Hasebe, M.; Sueki, S.; Anada, M. Brønsted Acid Catalyzed Dehydroxylative Cyanation of Benzylic Alcohols with Trimethylsilyl Cyanide Using1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol as a Solvent. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Shen, C.; Wang, G.; Shi, Z.; Tian, X.; Dong, K. Access to α-Cyano Carbonyls Bearing a Quaternary Carbon Center by Reductive Cyanation. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 2527–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Morandi, B. Nickel-Catalyzed Cyanation of Aryl Chlorides and Triflates Using Butyronitrile: Merging Retro-hydrocyanation with Cross-Coupling. Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 15899–15903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.P.; Romney-Alexander, T.M. Cyanation of Aromatic Halides. Chem. Rev. 1987, 87, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Kuang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Palladium-Catalyzed Direct Cyanation ofIndoles with K4[Fe(CN)6]. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Jiao, N. Direct Approaches to Nitriles via Highly Efficient Nitrogenation Strategy through C−H or C−C Bond Cleavage. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

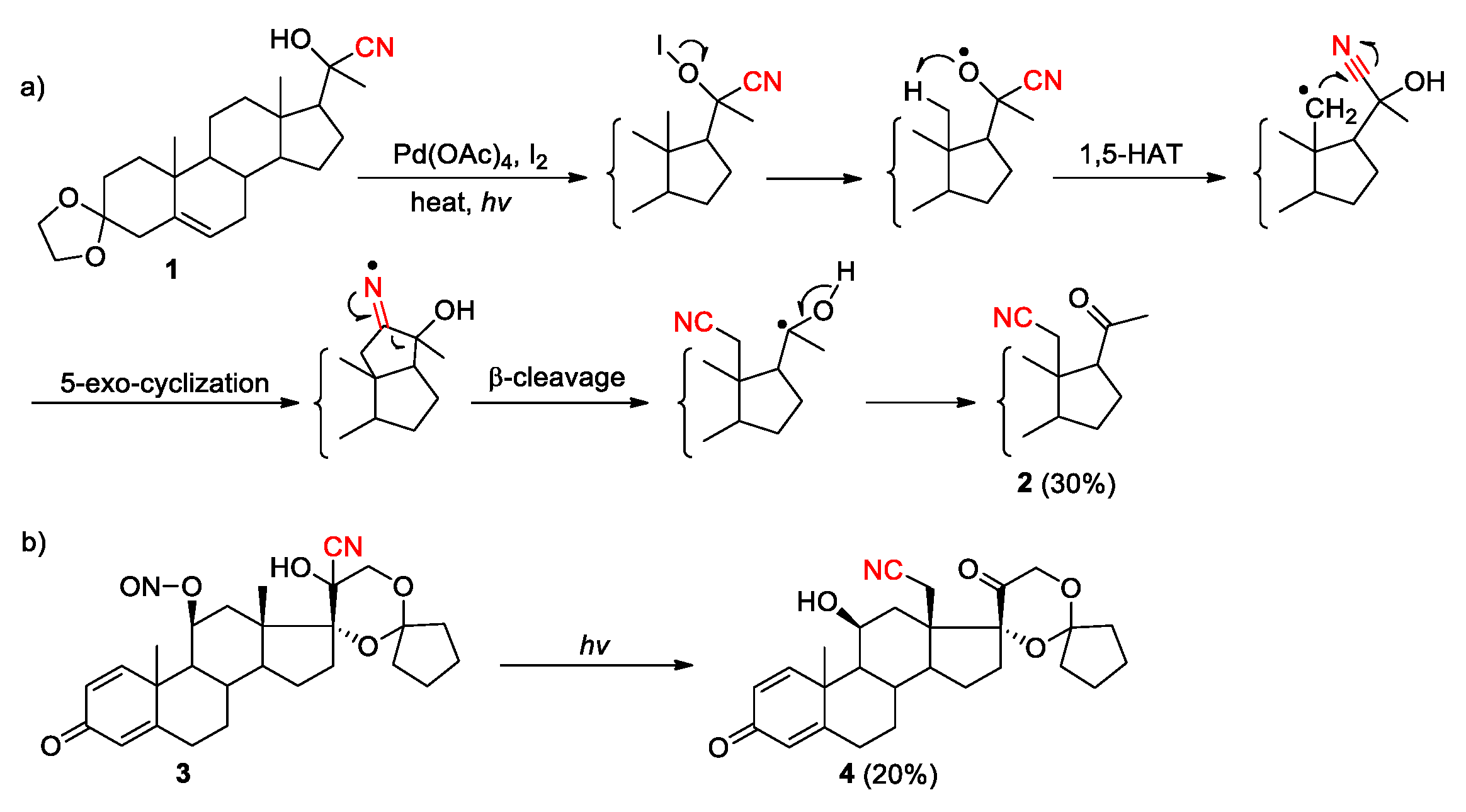

- Meystre, C.; Heusler, K.; Kalvoda, J.; Wieland, P.; Anner, G.; Wettstein, A. New substitution reactions in steroids. Experientia 1961, 17, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvoda, J.; Meystre, C.; Anner, G. Reaktionen von Steroid-Hypojoditen VIII 1,4-Verschiebung der Nitrilgruppe (18-Cyano-pregnane). Helv. Chim. Acta 1966, 49, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Pillai, J.; Lush, R.K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2001, 30, 94-103.

- Li, W.; Xu, W.; Xie, J.; Yu, S.; Zhu, C. Distal radical migration strategy: an emerging synthetic means. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, C. Recent Advances in Radical-Mediated C-C Bond Fragmentation of Non-Strained Molecules. Chin. J. Chem. 2019, 37, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, C. Radical-Mediated Remote Functional Group Migration. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1620–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Ma, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhu, C. Radical-mediated rearrangements: past, present, and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 11577–11613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, X.; Zhi, S.; Zhang, W. Radical-Mediated Trfunctionalization Reactions. Molecules 2024, 29, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafzi, F.; Eşsiz, S. Computational Study on Chemoselective Difunctionalization of Unactivated Alkenes with Radical-mediated Remote Functional Group Migration. ChemPhysChem 2023, 24, e202200886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvoda, J. A New Type of Intramolecular Group-transfer in Steroid Photochemistry. A Contribution to the Mechanism of the Oxidative Cyanohydrin-Cyano-ketone Rearrangement. Chem. Commun 1970, 1002–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

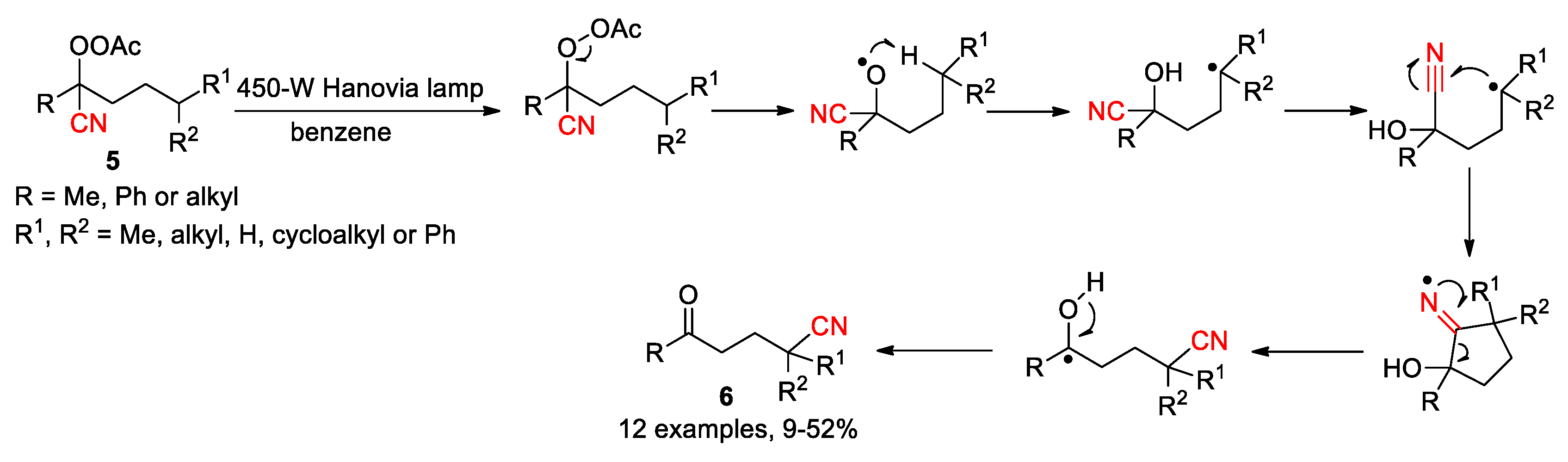

- Watt, D.S. A Reiterative Functionalization of Unactivated Carbon-Hydrogen Bonds. Photolysis of α-Peracetoxynitriles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freerksen, R.W.; Pabst, W.E.; Raggio, M.L.; Sherman, S.A.; Wroble, R.R.; Watt, D.S. Photolysis of α-Peracetoxynitriles. 2. A Comparison of Two Synthetic Approaches to 18-Cyano-20-ketosteroids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 1536–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Manion, B.D.; Benz, A.; Rath, N.P.; Evers, A.S.; Zorumski, C.F.; Mennerick, S.; Covey, D.F. Neurosteroid Analogues. 9. Conformationally Constrained Pregnanes: Structure-Activity Studies of 13,24-Cyclo-18,21-dinorcholane Analogues of the GABA Modulatory and Anesthetic Steroids (3α,5α)- and (3α,5α)-3-Hydroxypregnan-20-one. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 5334–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prier, C.K.; Rankic, D.A.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huan, L.; Zhu, C. Cyanohydrin-Mediated Cyanation of Remote Unactivated C(sp3)-H Bonds. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- For the production of sulfate radical anion (SO4•– ) along with SO42- from S2O82- , see: Jin, J.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Direct α-Arylation of Ethers through the Combination of Photoredox-Mediated C-H Functionalization and the Minisci Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1565-1569.

- Lei, Z.; Wu, J. Terminal-selective C(sp3)-H borylation of unbranched alkanes enabled by intermolecular radical sampling and LMCT photocatalysis. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

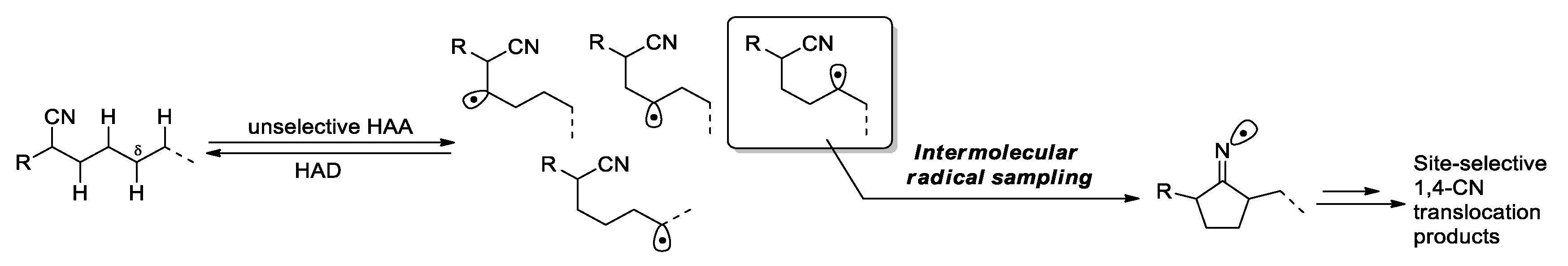

- Chen, K.; Zeng, Q.; Xie, L.; Xue, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y. Functional-group translocation of cyano groups by reversible C-H sampling. Nature 2023, 620, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.P.; Sinha, S.; Gahtori, P.; Tivaric, S.; Srivastava, V. Recent advances of decatungstate photocatalyst in HAT process. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 2523–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bury, A.; Bougeard, P.; Corker, S.J.; Johnson, M.D.; Perlmann, M. 1,3-Migration of a Cyano-group in Substituted 3-Cyanopropyl Radicals. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. II 1982, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montevecehi, P.C.; Navacehia, M.L.; Spagnolo, P. 2-Cyano-isopropyl radical addition to alkynes. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 7929–7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

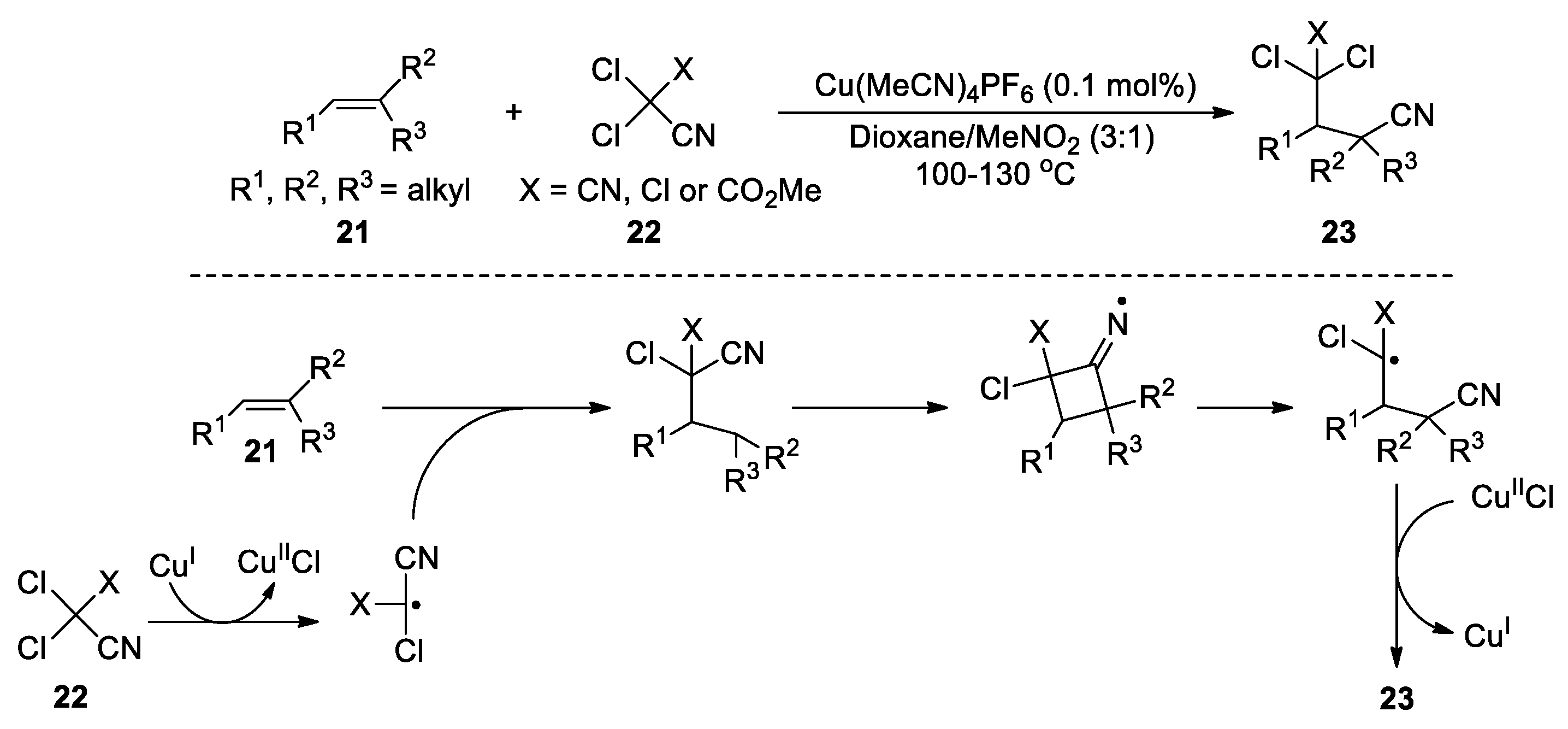

- Kamijo, S.; Yokosaka, S.; Inoue, M. Carbocyanation of trisubstituted olefins via Cu-catalyzed atom transfer radical addition. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 4324–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

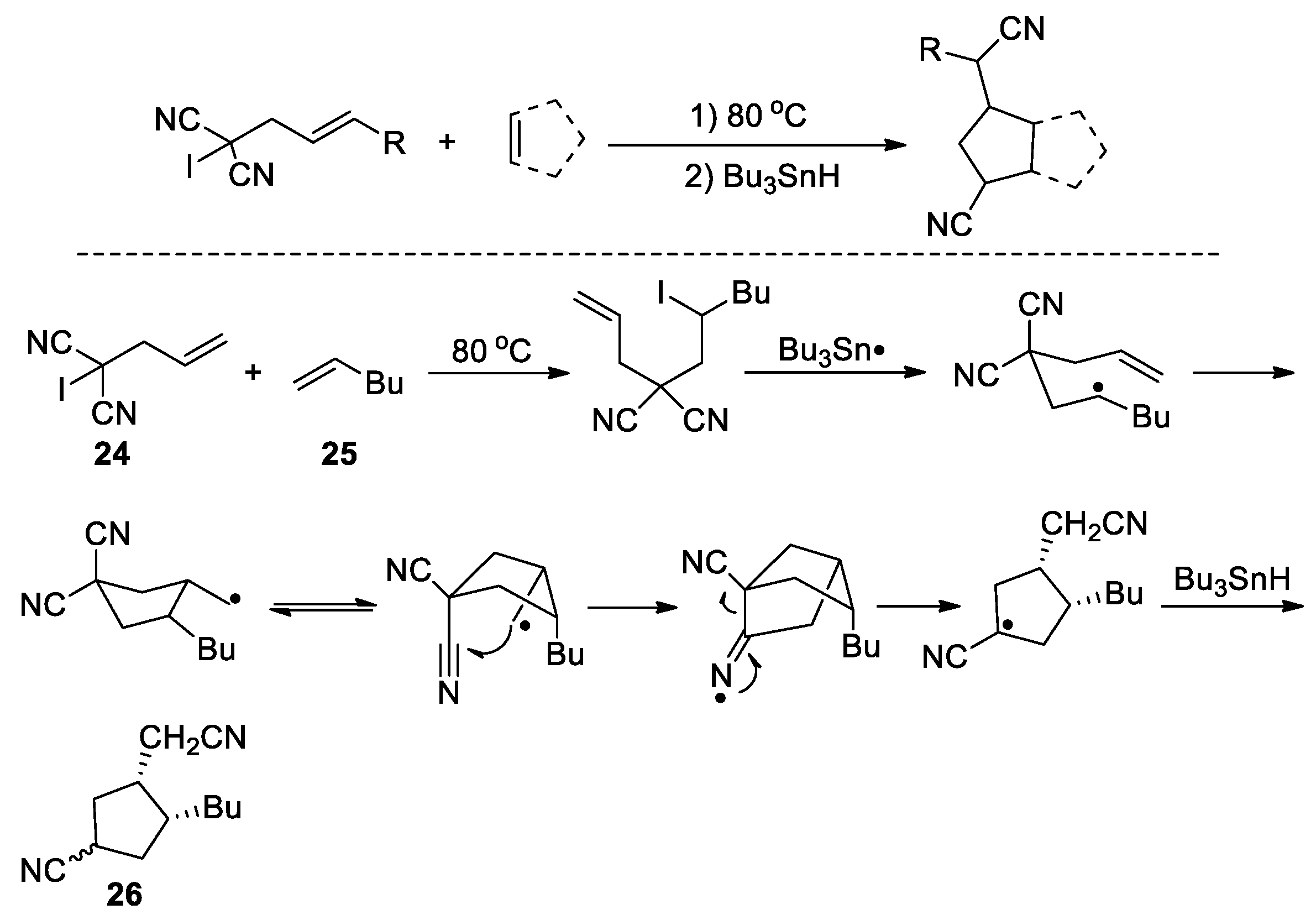

- Curran, D.P.; Seong, C.M. Radical annulation reactions of allyl iodomalononitriles. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 2175–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

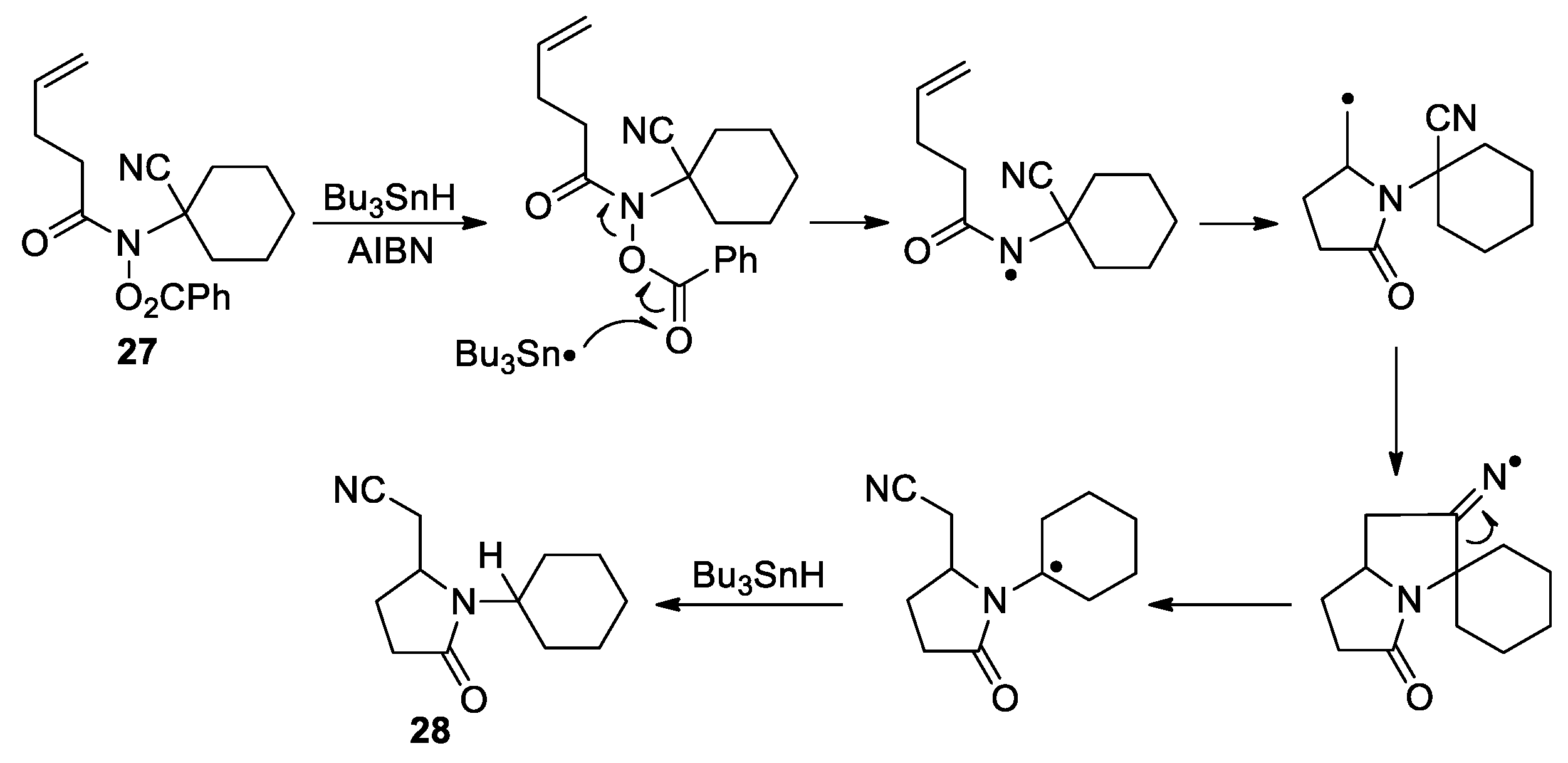

- Callier, A.C.; Quiclet-Sire, B.; Zard, S.Z. Amidyl and carbamyl radicals by stannane mediated cleavage of O-benzoyl hydroxamic acid derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 6109–6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

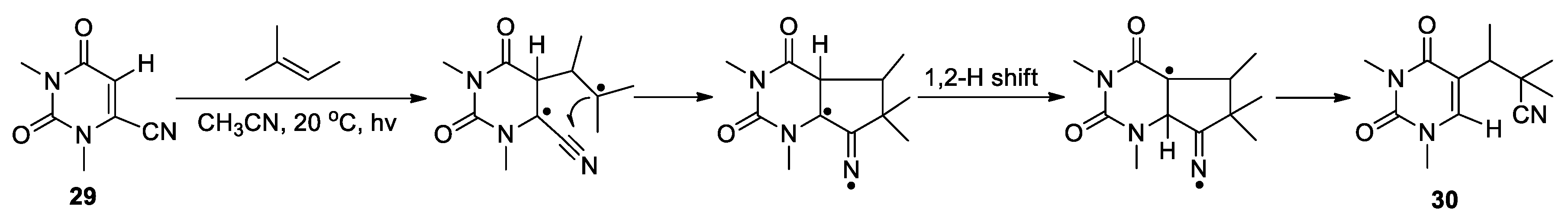

- Saito, I.; Shimozono, K.; Matsuura, T. A Novel Photoaddition of 6-Cyanouracils to Alkenes and Alkynes Involving Migration of a Cyano Group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 3948–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

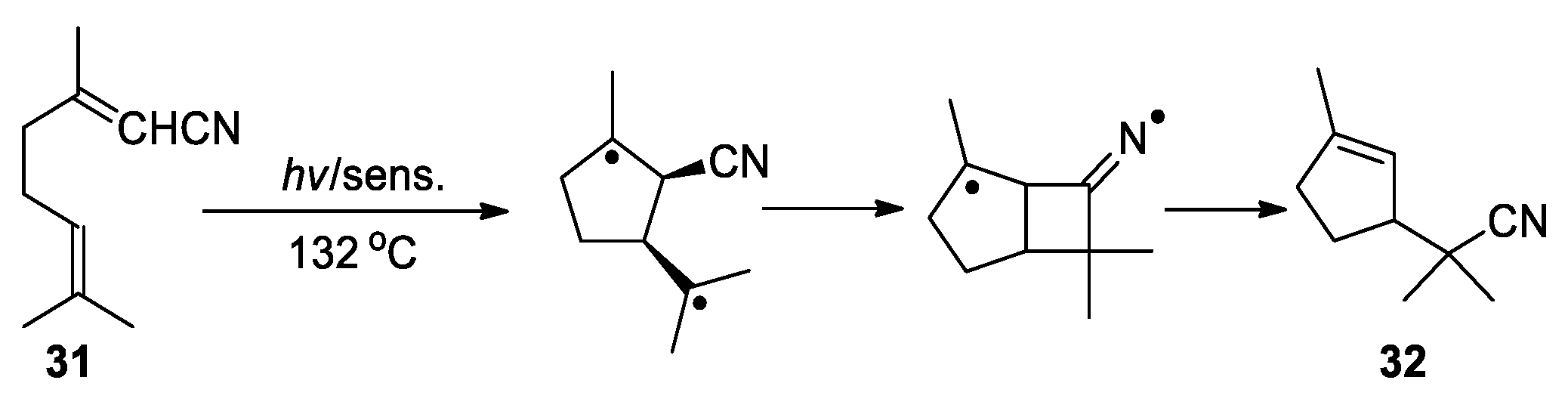

- Wolff, S.; Agosta, W.C. Triplet-Sensitized Photochemical Rearrangement of Geranonitrile at Elevated Temperature. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 3627–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Li, J.; Jiang, W.; Huo, C. Radical-Mediated Difunctionalization of Styrenes. Synthesis 2019, 51, 4507–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Hu, W.; Zhang, W. Difunctionalization of Alkenes and Alkynes via Intermolecular Radical and Nucleophilic Additions. Molecules 2021, 26, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Walsh, P.J.; Jia, T. Copper-Catalyzed Intermolecular Difunctionalization of Styrenes with Thiosulfonates and Arylboronic Acids via a Radical Relay Pathway. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 2633–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Wan, X.; Shen, Q. Cobalt-Catalyzed Enantioselective Dicarbofunctionalization of Acrylates. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 15221–15236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-L. Zhou, Q.; Liao, J.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, B.-Q.; Deng, G.-J.; Tang, K.-W.; Liu, Y. Cu-Catalyzed Oxidative Dual Arylation of Active Alkenes: Preparation of Cyanoarylated Oxindoles through Denitrogenation of 3-Aminoindazoles. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 2866–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, D.H.R.; Csiba, M.A.; Jaszberenyi, J.C. Ru(bpy)32+-mediated addition of Se-phenyl p-tolueneselenosulfonate to electron rich olefins. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 2869–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courant, T.; Masson, G. Recent Progress in Visible-Light Photoredox-Catalyzed Intermolecular 1,2-Difunctionalization of Double Bonds via an ATRA Type Mechanism. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6945–6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, K.J.; Nemoto Jr., D.; Kao, S.C.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.-S.; West, J.G. Modular Difunctionalization of Unactivated Alkenes through Bio-Inspired Radical Ligand Transfer Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11810–11821, and references cited therein. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

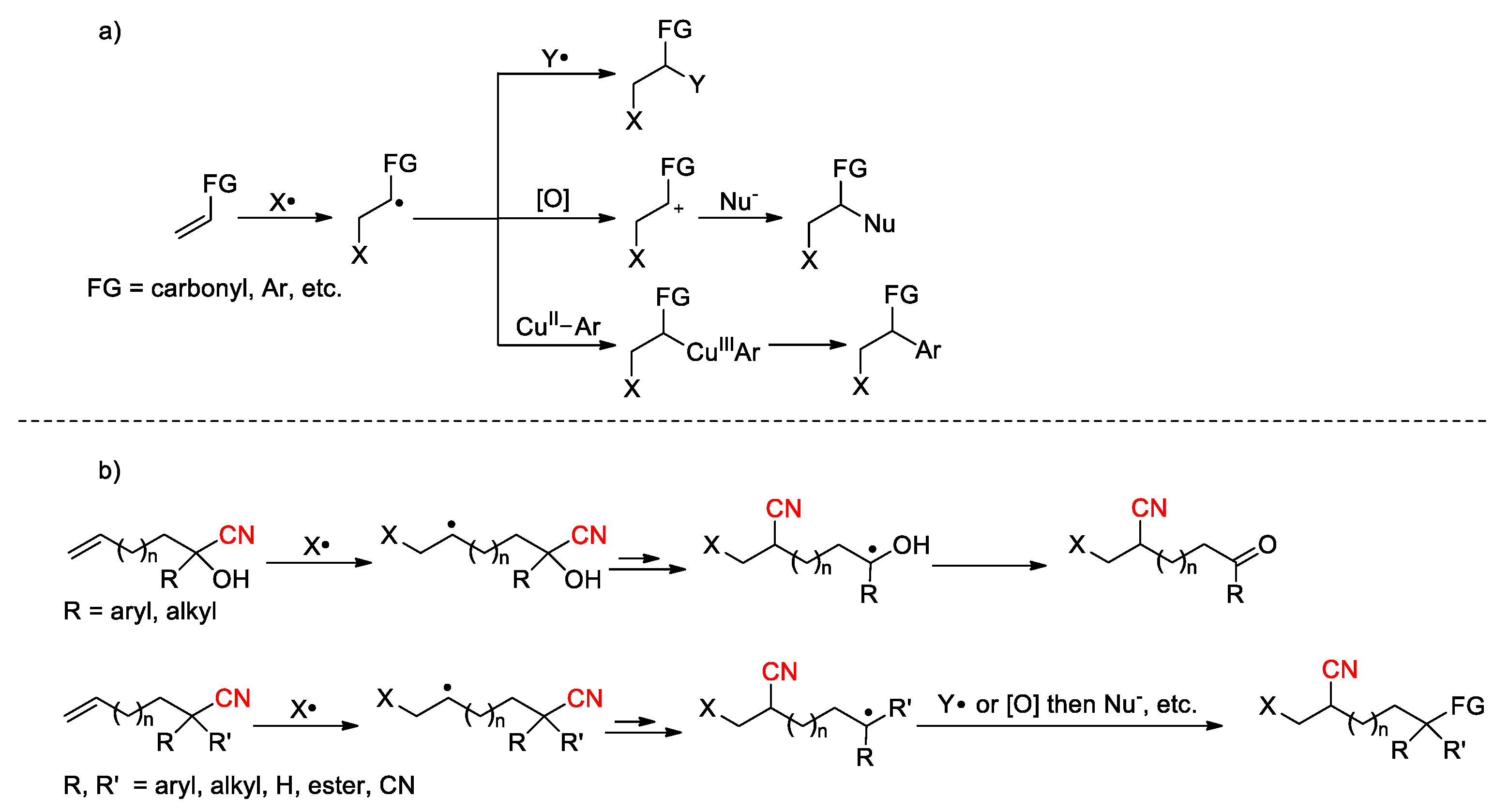

- Wu, X.; Wu, S.; Zhu, C. Radical-mediated difunctionalization of unactivated alkenes through distal migration of functional groups. Tetrahedron. Lett. 2018, 59, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Claraz, A. Vicinal Difunctionalization of Unactivated Alkenes Through Radical Addition/Remote (Hetero)Aryl Migration Cascade. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 27, e202400504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

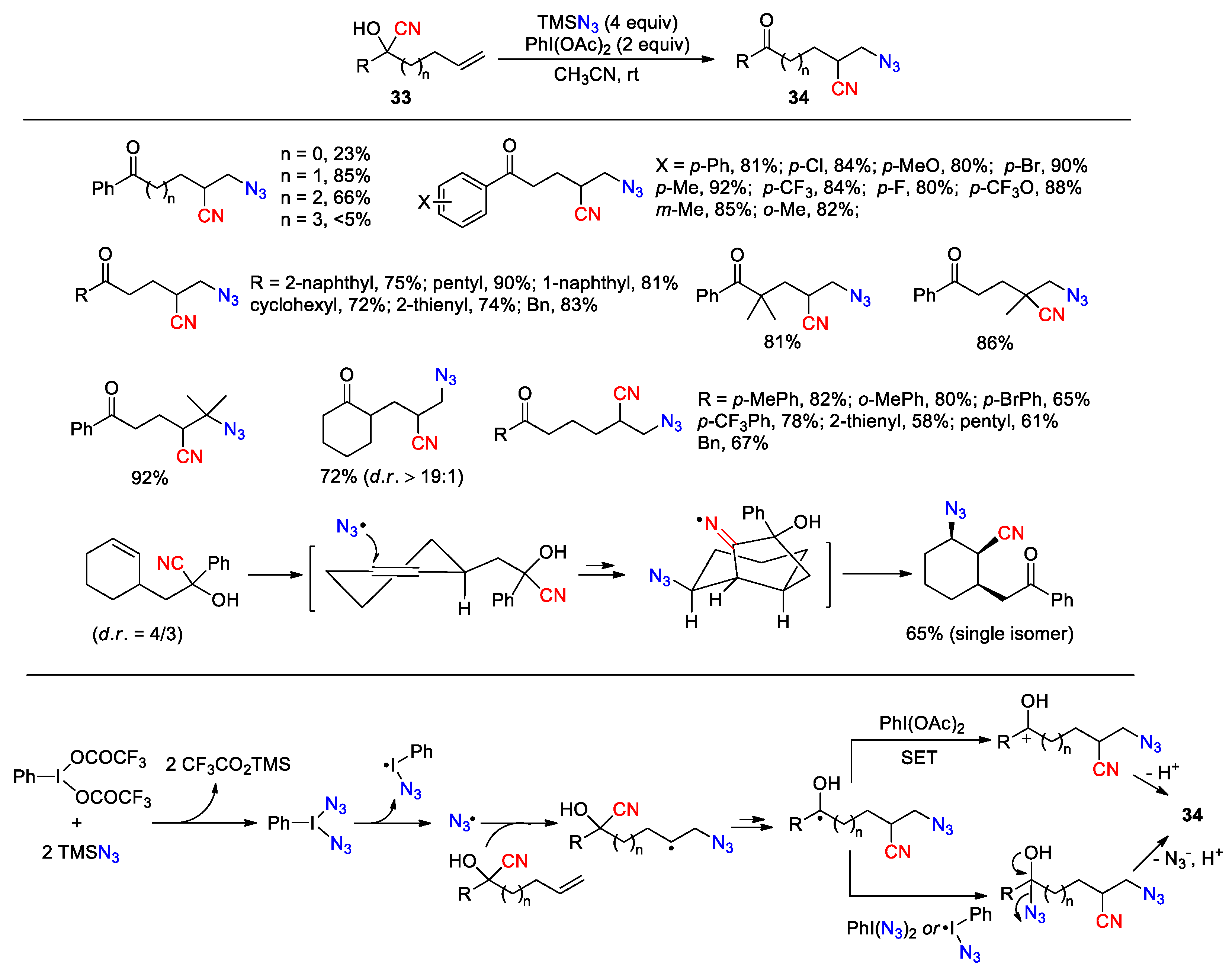

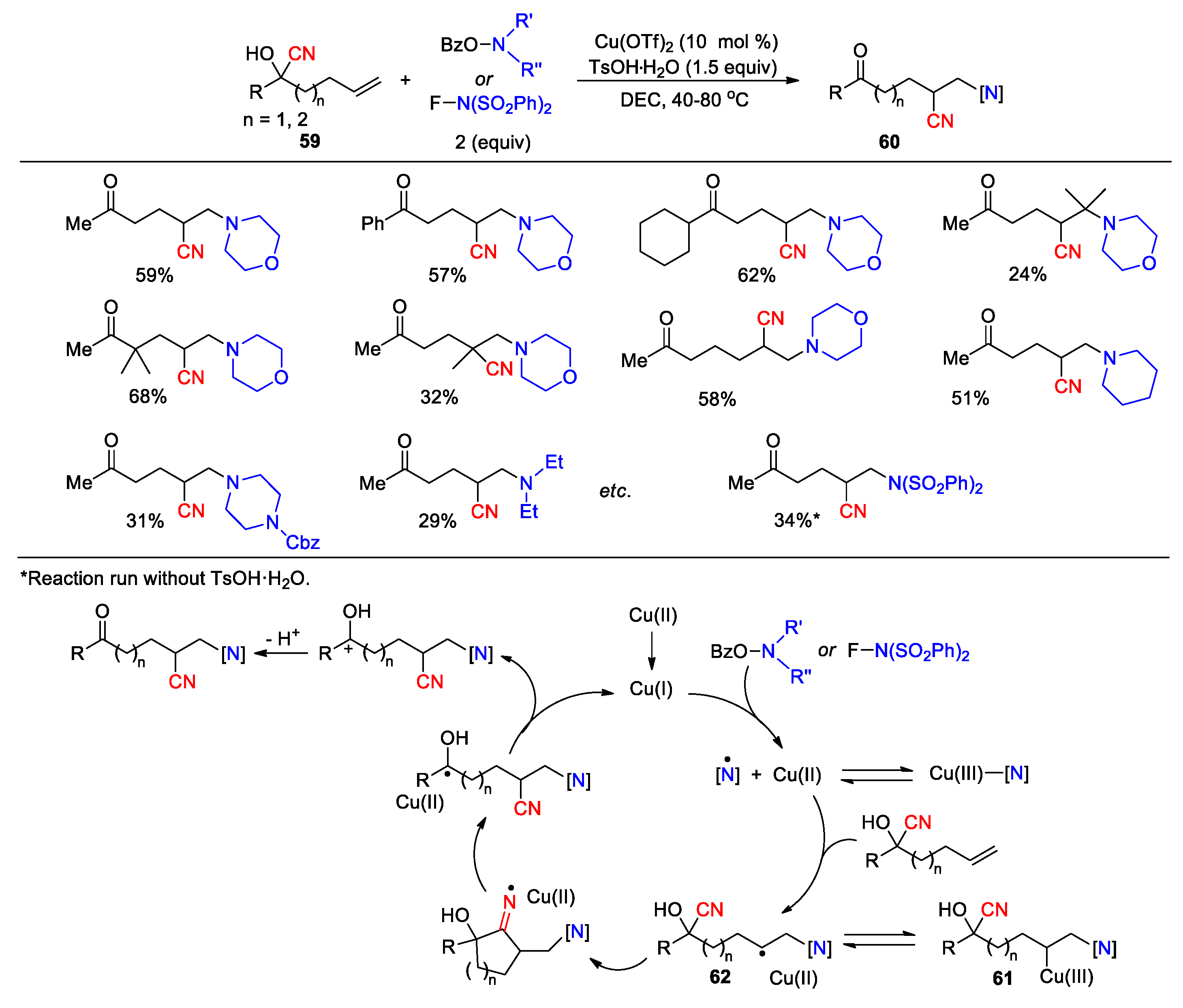

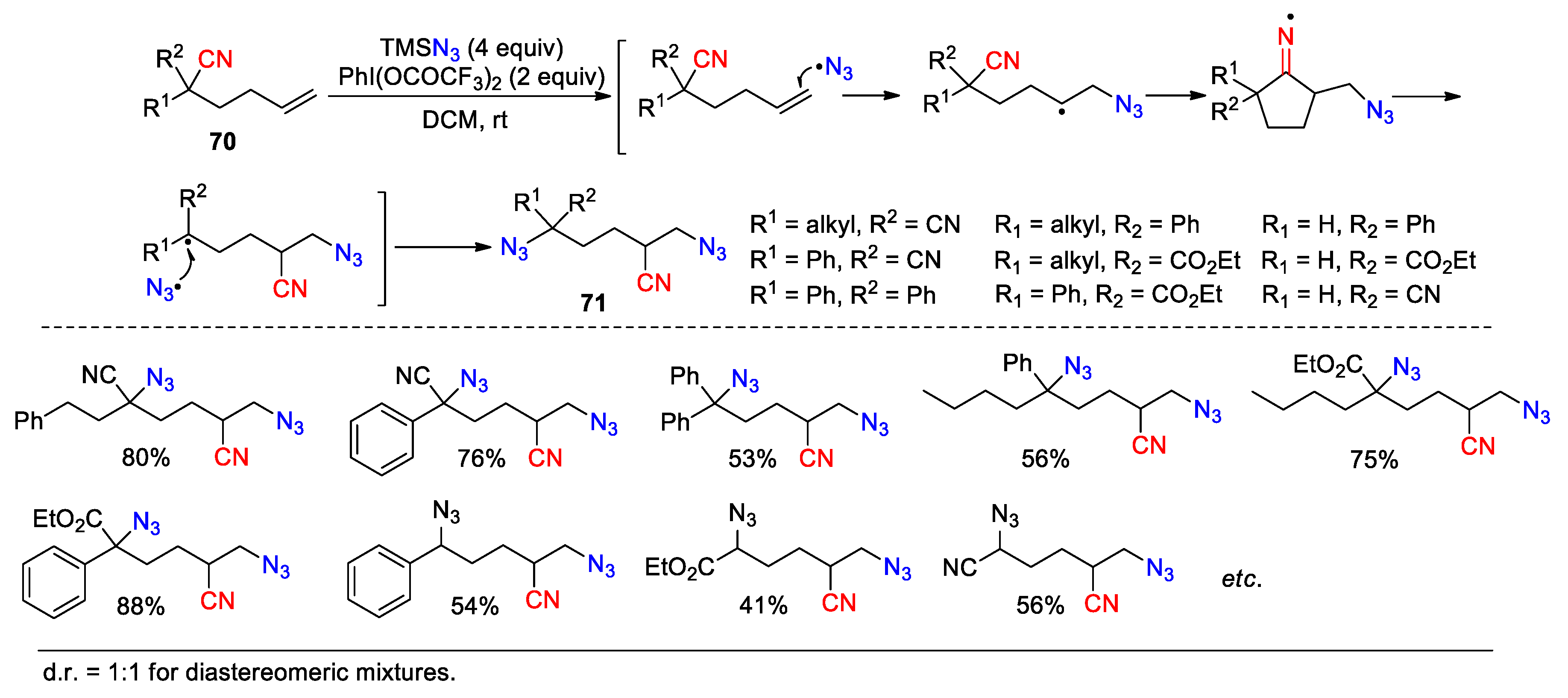

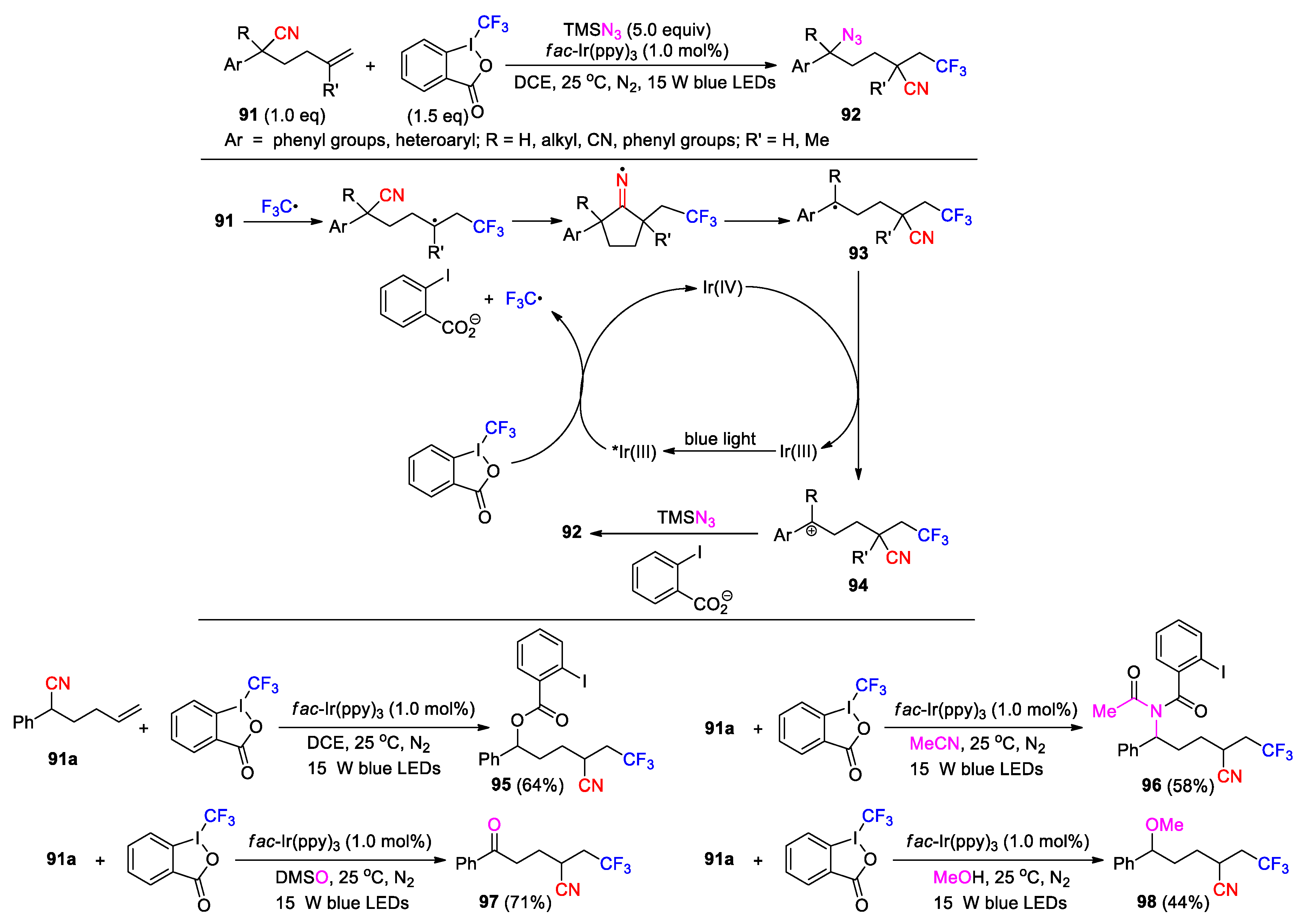

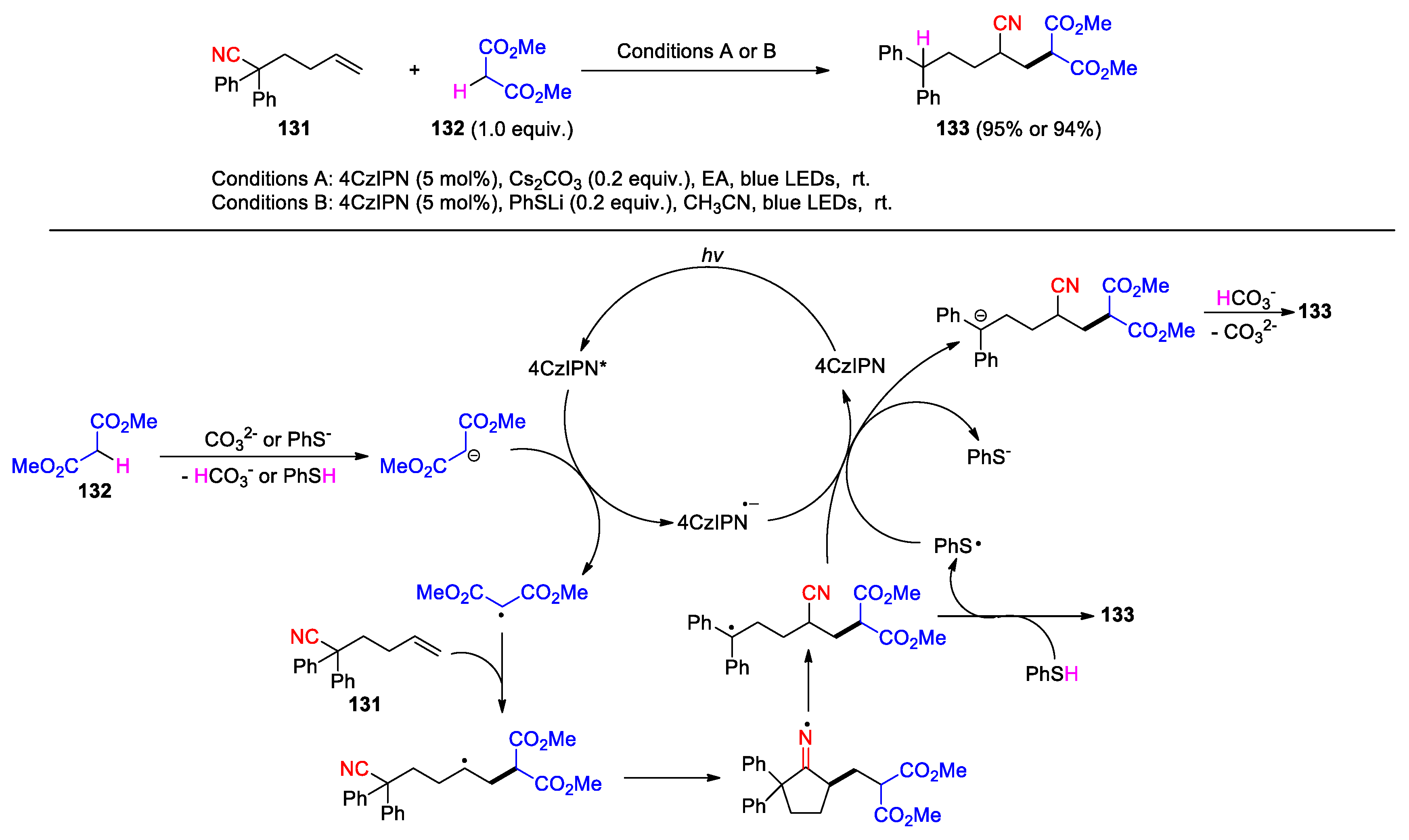

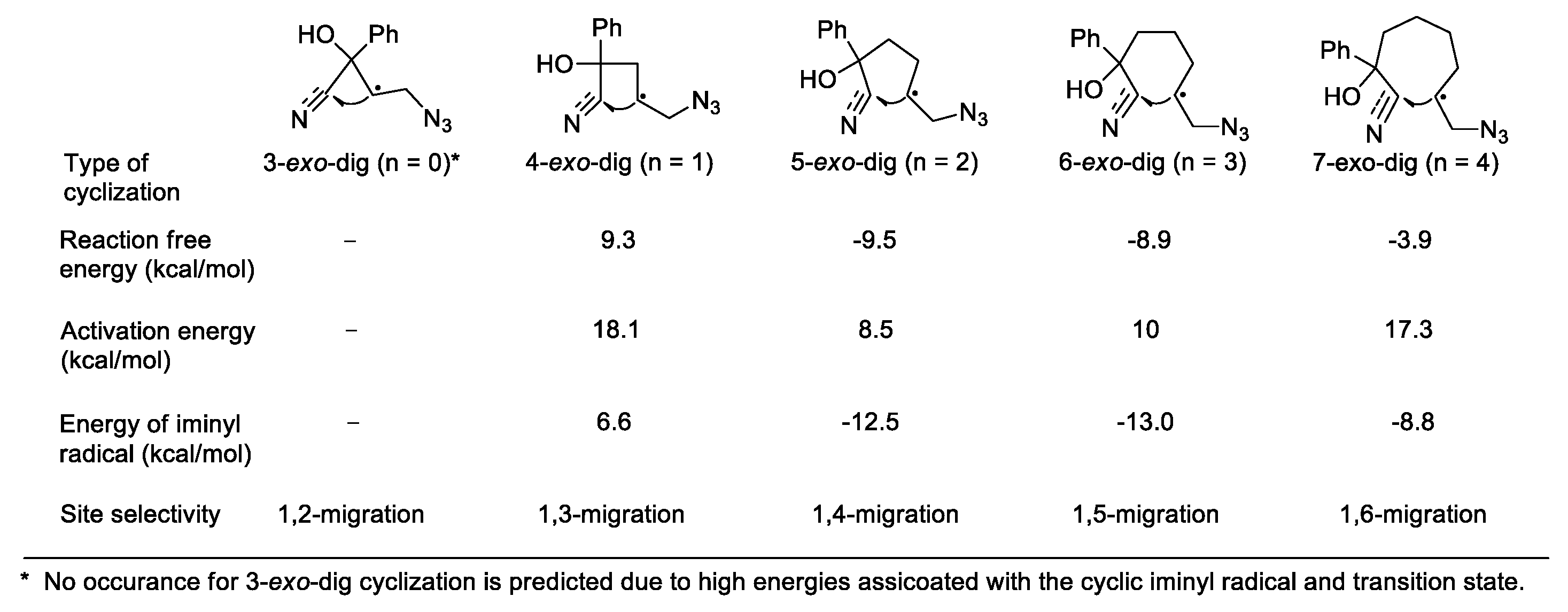

- Wu, Z.; Ren, R.; Zhu, C. Combination of a Cyano Migration Strategy and Alkene Difunctionalization: The Elusive Selective Azidocyanation of Unactivated Olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10821–10824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matcha, K.; Narayan, R.; Antonchick, A.P. Metal-Free Radical Azidoarylation of Alkenes: Rapid Access to Oxindoles by Cascade C-N and C-C Bond-Forming Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7985–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

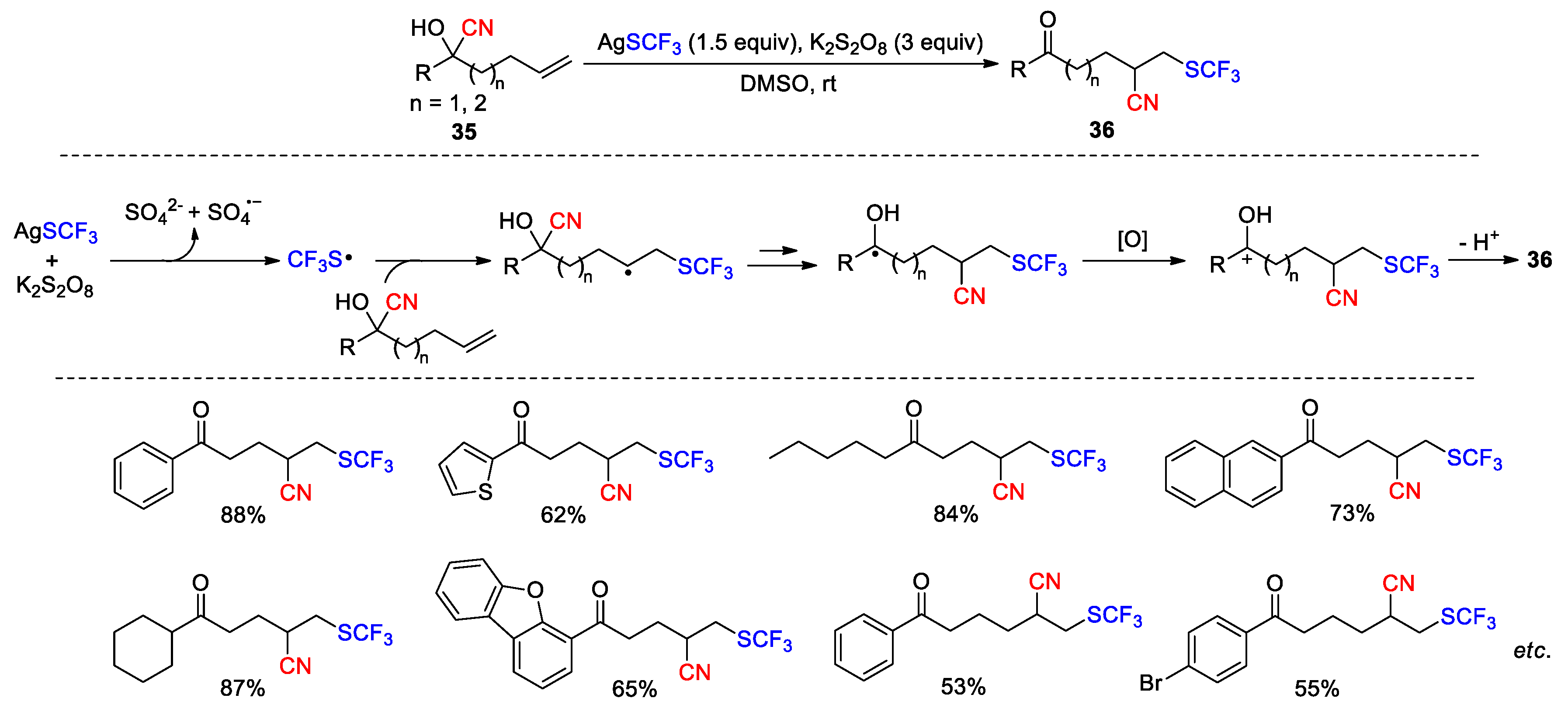

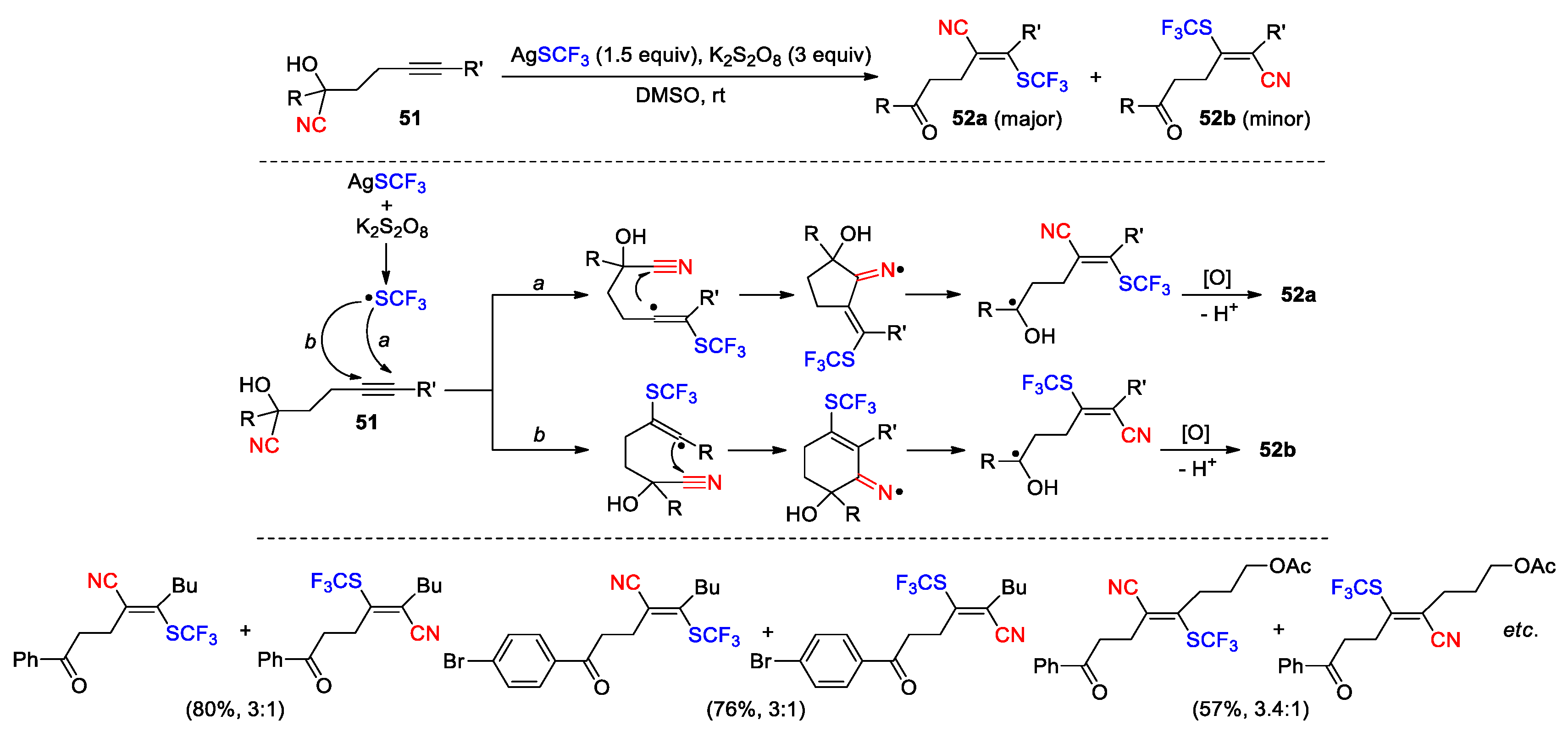

- Ji, M.; Wu, Z.; Yu, J.; Wan, X.; Zhu, C. Cyanotrifluoromethylthiolation of Unactivated Olefins through Intramolecular Cyano Migration. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 1959–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

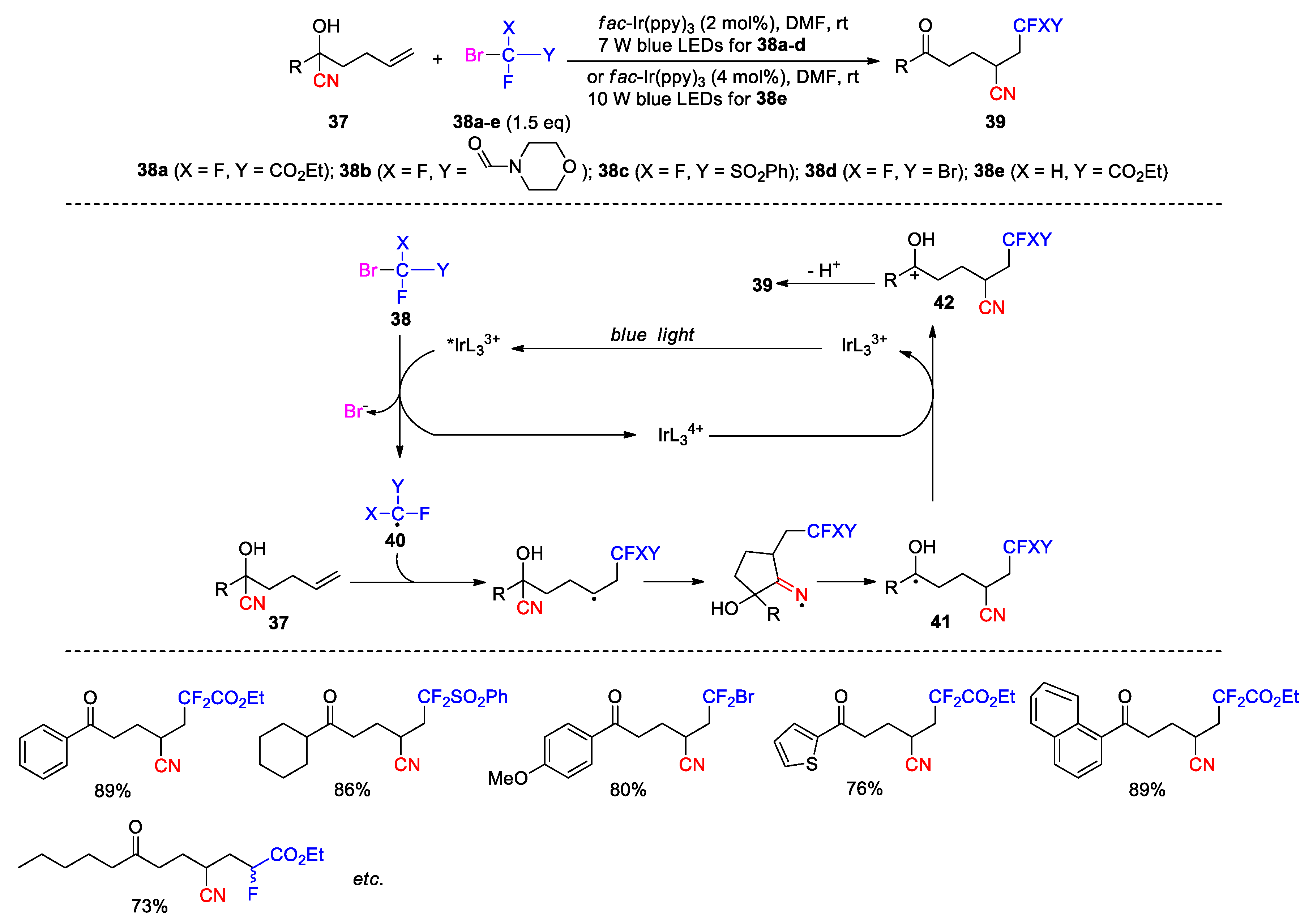

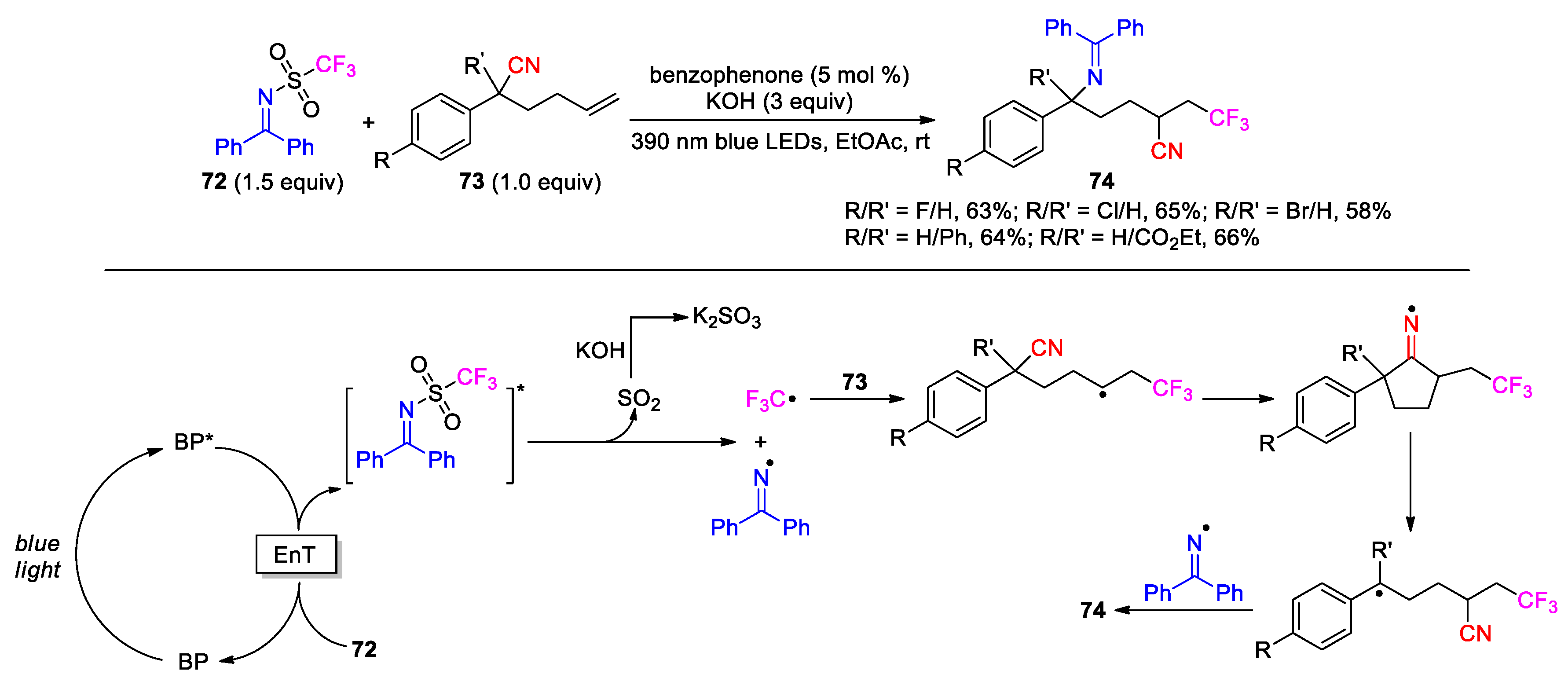

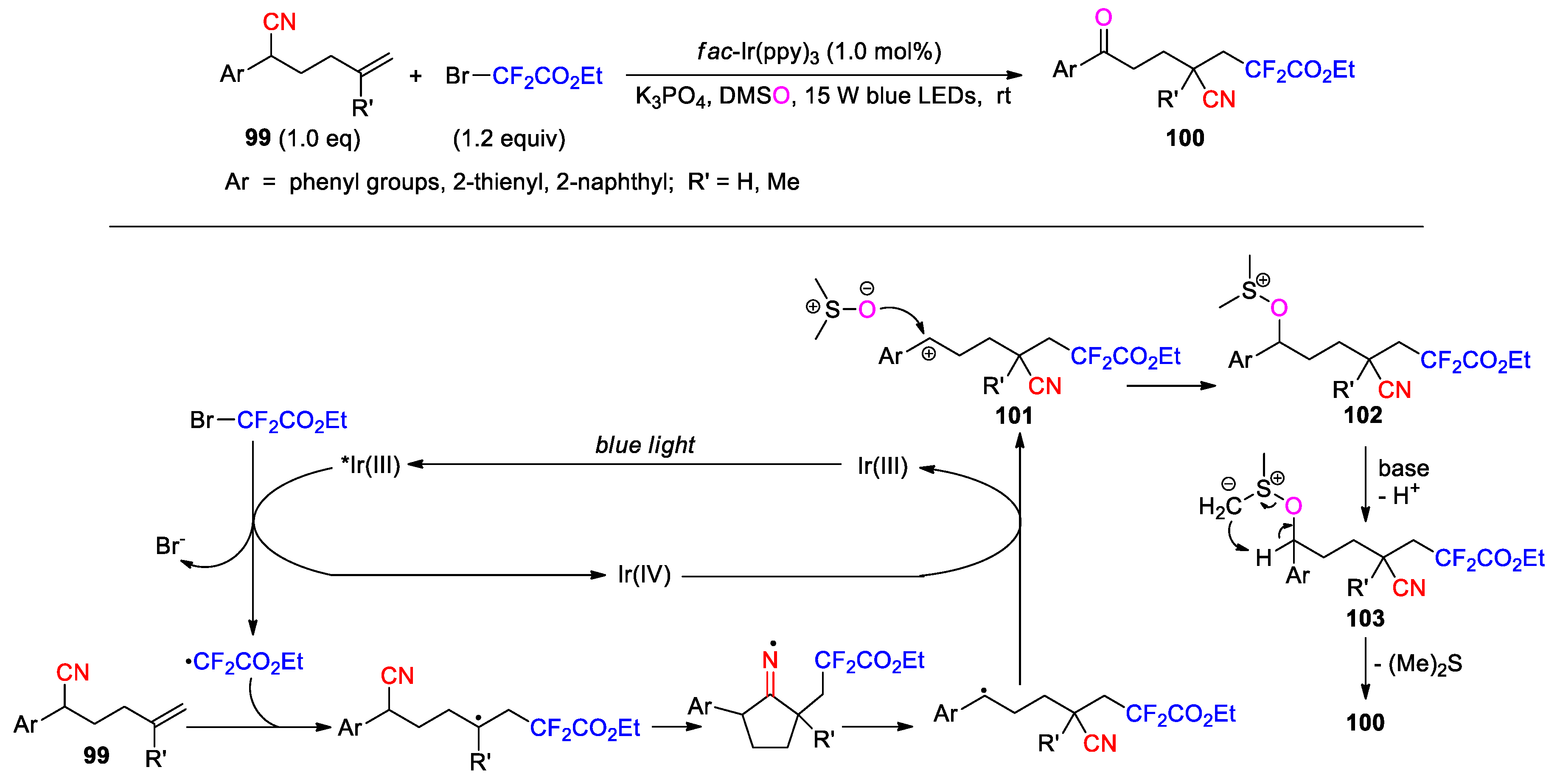

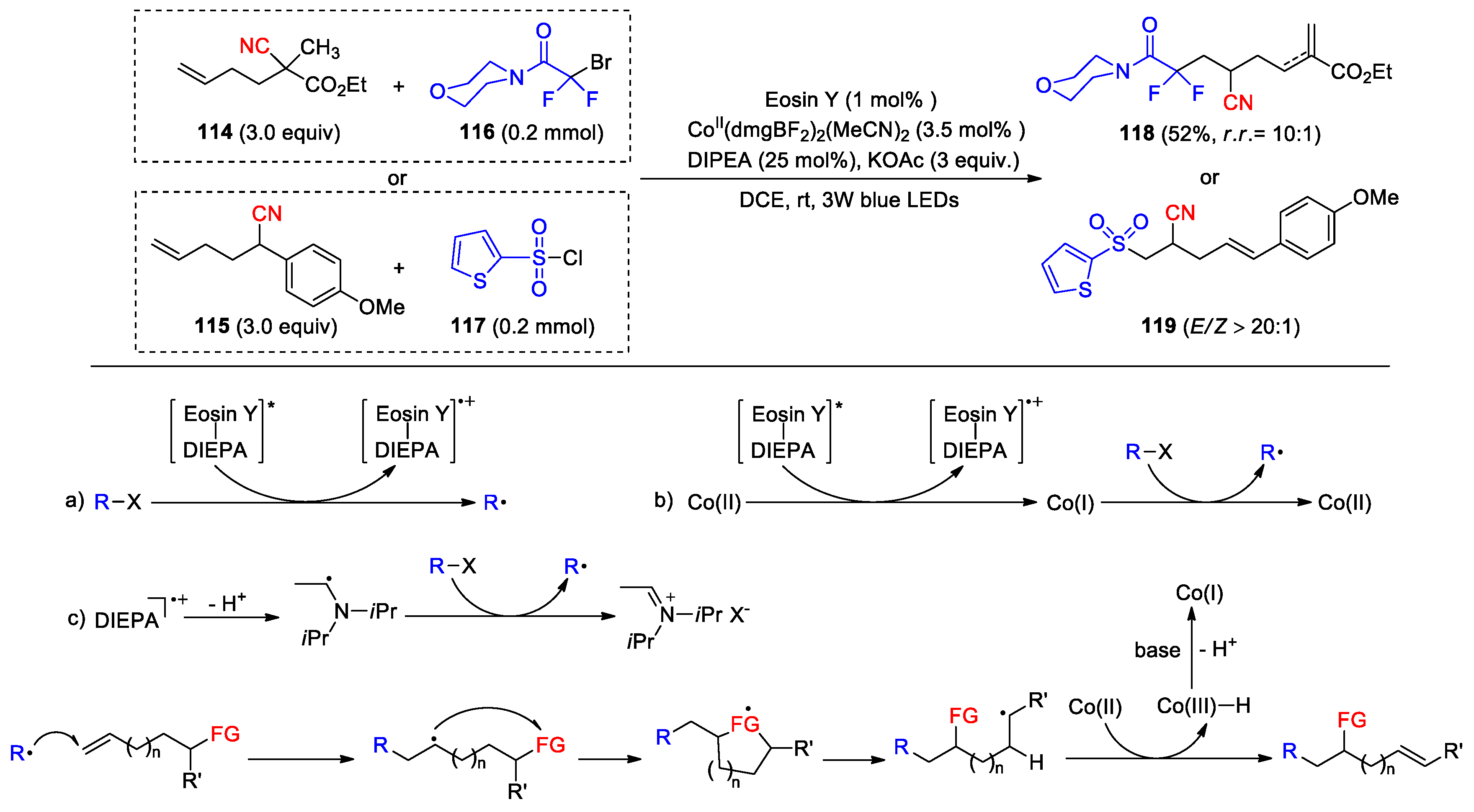

- Ren, R.; Wu, Z.; Huan, L.; Zhu, C. Synergistic Strategies of Cyano Migration and Photocatalysis for Difunctionalization of Unactivated Alkenes: Synthesis of Di- and Mono-Fluorinated Alkyl Nitriles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 3052–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.D.; D’Amato, E.M.; Narayanam, J.M.R.; Stephenson, C.R.J. Engaging unactivated alkyl, alkenyl and aryl iodides in visible-light-mediated free radical reactions. Nature Chem. 2012, 4, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

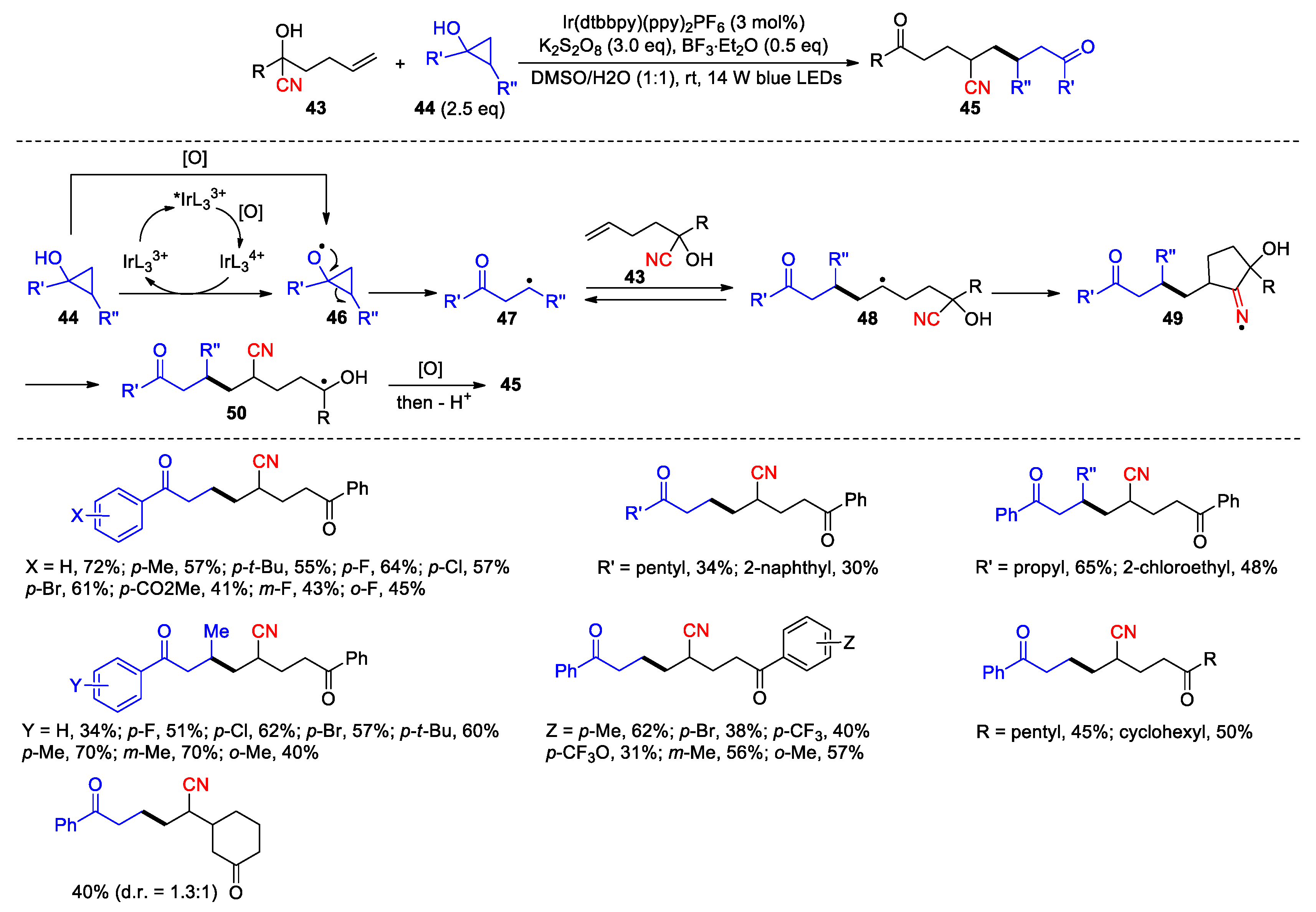

- Ji, M.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, C. Visible-light-induced consecutive C-C bond fragmentation and formation for the synthesis of elusive unsymmetric 1,8-dicarbonyl compounds. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2368–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Yu, J.; Zhu, C. Cyanotrifluoromethylthiolation of unactivated dialkyl-substituted alkynes via cyano migration: synthesis of trifluoromethylthiolated acrylonitriles. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 6812–6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

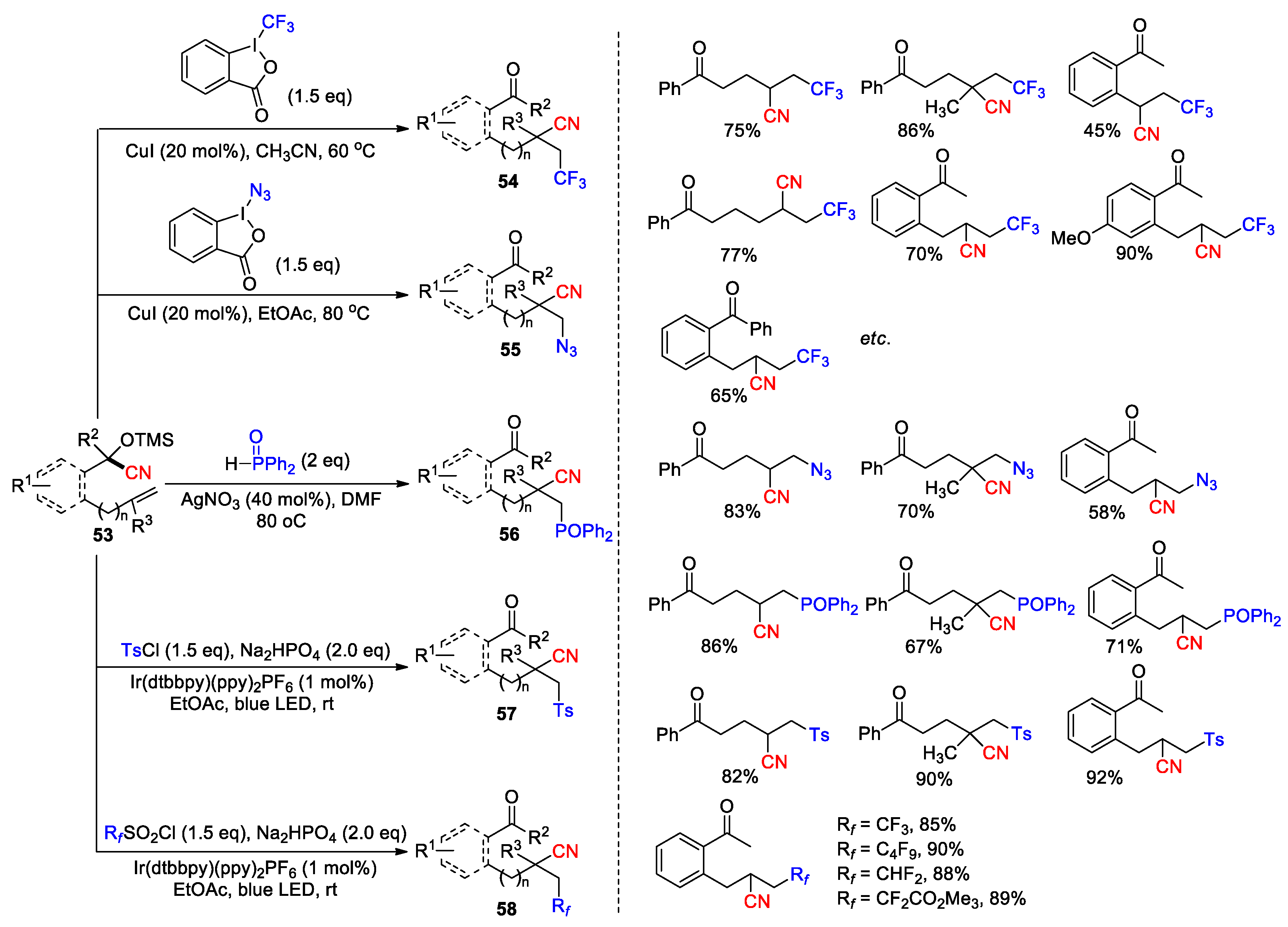

- Wang, N.; Li, L.; Li, Z.-L.; Yang, N.-Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.-X.; Liu, X.-Y. Catalytic Diverse Radical-Mediated 1,2-Cyanofunctionalization of Unactivated Alkenes via Synergistic Remote Cyano Migration and Protected Strategies. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 6026–6029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- For producing trifluoromethyl radical form Togni’s reagent and Cu(I) catalyst, see: Barata-Vallejo, S; Lantaño, B.; Postigo, A. Recent Advances in Trifluoromethylation Reactions with Electrophilic Trifluoromethylating Reagents. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 1-25.

- For producing azido radical form Zhdankin reagent and Cu(I) catalyst, see: Rabet, P.T.G.; Fumagalli, G.; Boyd, S.; Greaney, M.F. Benzylic C-H Azidation Using the Zhdankin Reagent and a Copper Photoredox Catalyst. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 1646-1649.

- For the SET reduction of Cu(II) species by ketyl radical intermediate to regenerate Cu(I) catalyst, see: Gao, P.; Shen, Y.-W.; Fang, R.; Hao, X.-H.; Qiu, Z.-H.; Yang, F.; Yan, X.-B.; Wang, Q.; Gong, X.-J.; Liu, X.-Y.; Liang, Y.-M. Copper-catalyzed one-pot trifluoromethylation/aryl migration/carbonyl formation with homopropargylic alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7629–7633.

- For producing phosphonyl radical from diphenyl phosphine oxide and AgNO3, see: Liu, Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Zeng, F.-L. Sun, K.; Qu, C.; Fan, L.-L.; An, Z.-L.; Li, R.; Jing, C.-F.; Wei, S.-K.; Qu, L.-B.; Yu, B.; Sun, Y.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-F. Phosphorus Radical-Initiated Cascade Reaction to Access 2-Phosphoryl-Substituted Quinoxalines. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 11727-11735.

- For producing p-toluenesulfonyl radical from p-toluenesulfonyl chloride under photoredox catalytic conditions, see: Ding, R.; Li, L.; Yu, Y.-T.; Zhang, B.; Wang, P.-L. Photoredox-Catalyzed Synthesis of 3-Sulfonylated Pyrrolin-2-ones via a Regioselective Tandem Sulfonylation Cyclization of 1,5-Dienes. Molecules 2023, 28, 5473.

- For producing perfluoroalkyl radicals from fluorinated sulfonyl chlorides under photoredox catalytic conditions, see: Kliś, T. Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis for the Synthesis of Fluorinated Aromatic Compounds. Catalysts 2023, 13, 94.

- Hu, J.; Yang, C.; Qin, X.; Liu, H.; Ma, T.; Shi, A.-t.; Lv, Q.-L.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Li, D. Catalyst- and base-free visible light-enabled radical relay trihalomethylation/functional group-migration/carbonylation with CX3SO2Cl. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2024, 22, 4488–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

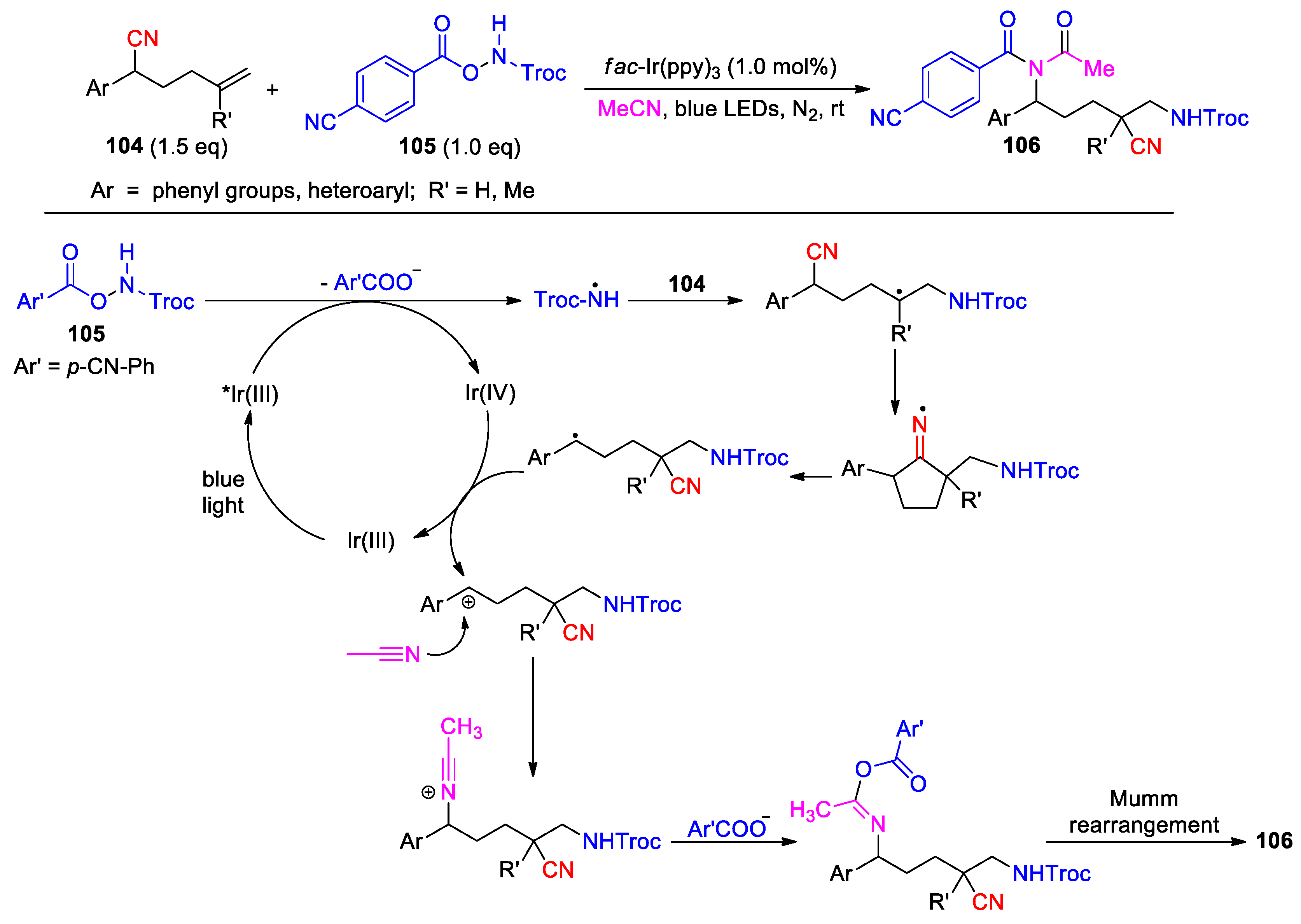

- Kwon, Y.; Wang, Q. Copper-Catalyzed 1,2-Aminocyanation of Unactivated Alkenes via Cyano Migration. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 4141–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Xiang, J.-N.; Li, J.-H. Fluoroamide-driven intermolecular hydrogen-atom-transfer-enabled intermolecular 1,2-alkylarylation of alkenes. Org. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Banerjee, A.; Yao, W.; Patterson, E.V.; Ngai, M.-Y. Photocatalytic Radical Aroylation of Unactivated Alkenes: Pathway to β-Functionalized 1,4-, 1,6-, and 1,7-Diketones. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 10358–10364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

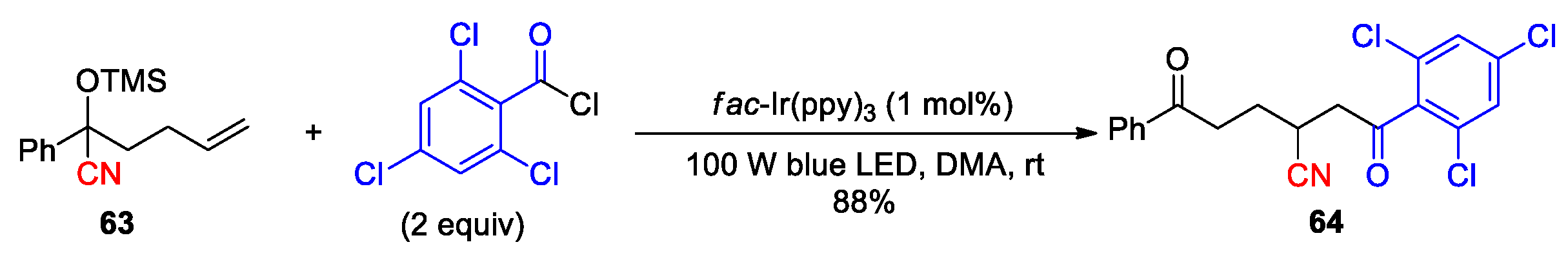

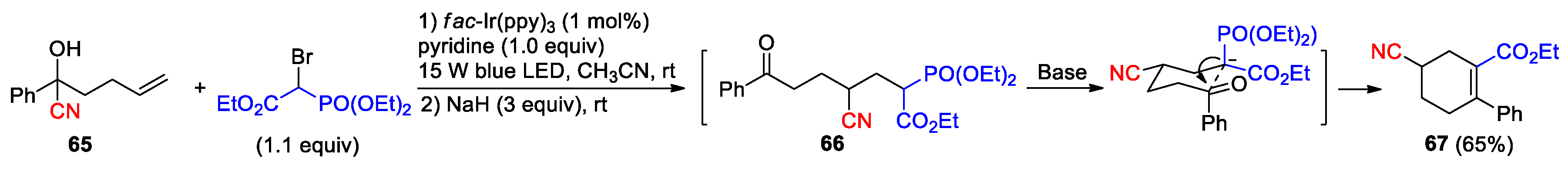

- Zhang, X.-G.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Feng, C. Multisubstituted Cyclohexene Construction through Telescoped Radical-Addition Induced Remote Functional Group Migration and Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons (HWE) Olefination. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 9611–9615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

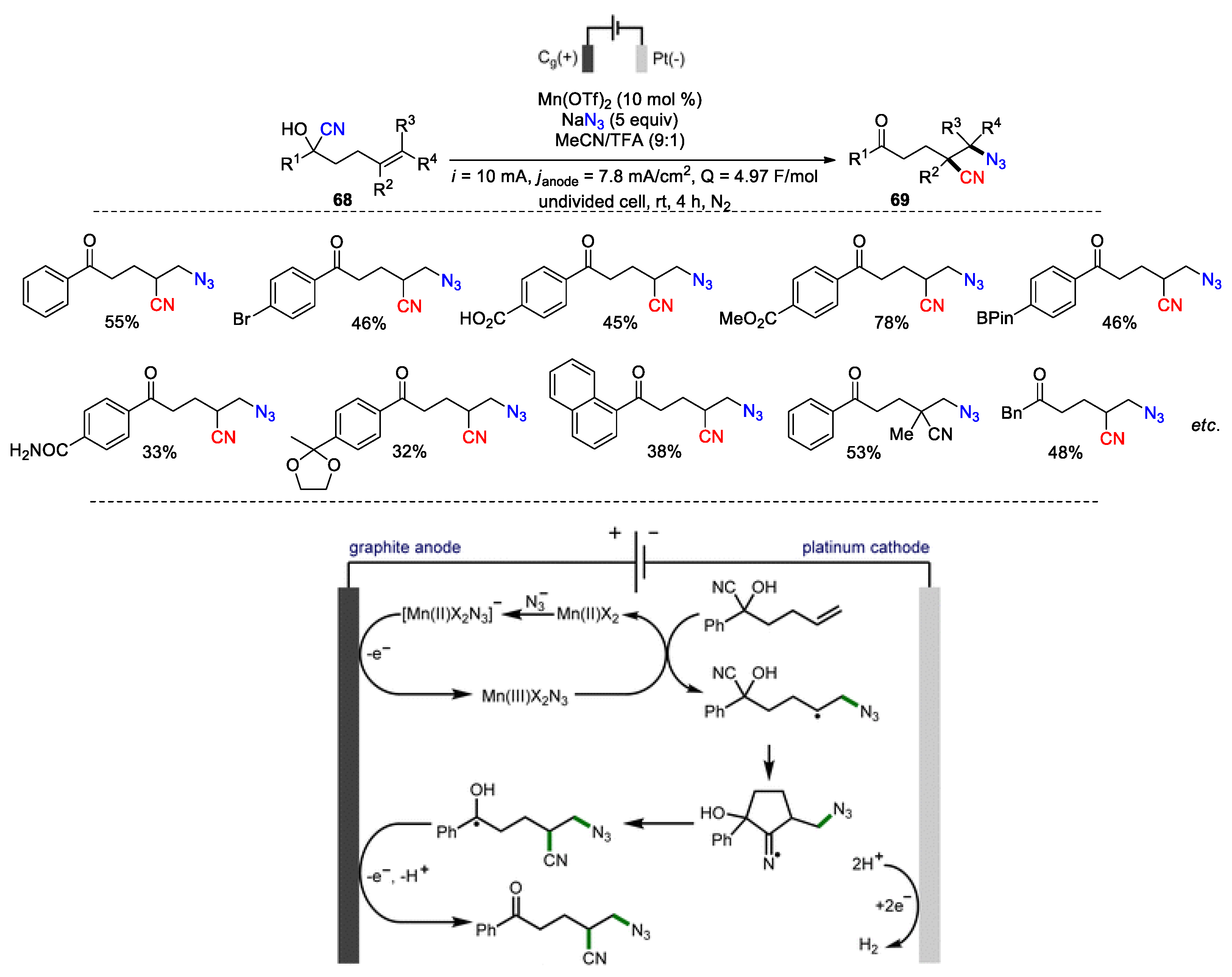

- Seastram, A.C.; Hareram, M.D.; Knight, T.M.B.; Morrill, L.C. Electrochemical alkene azidocyanation via 1,4-nitrile migration. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 8658–8661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Zhu, C. Radical trifunctionalization of hexenenitrile via remote cyano migration. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, K.; Xiang, H.; Yang, H. Photochemical Alkene Trifluoromethylimination Enabled by Trifluoromethylsulfonylamide as a Bifunctional Reagent. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 2129–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

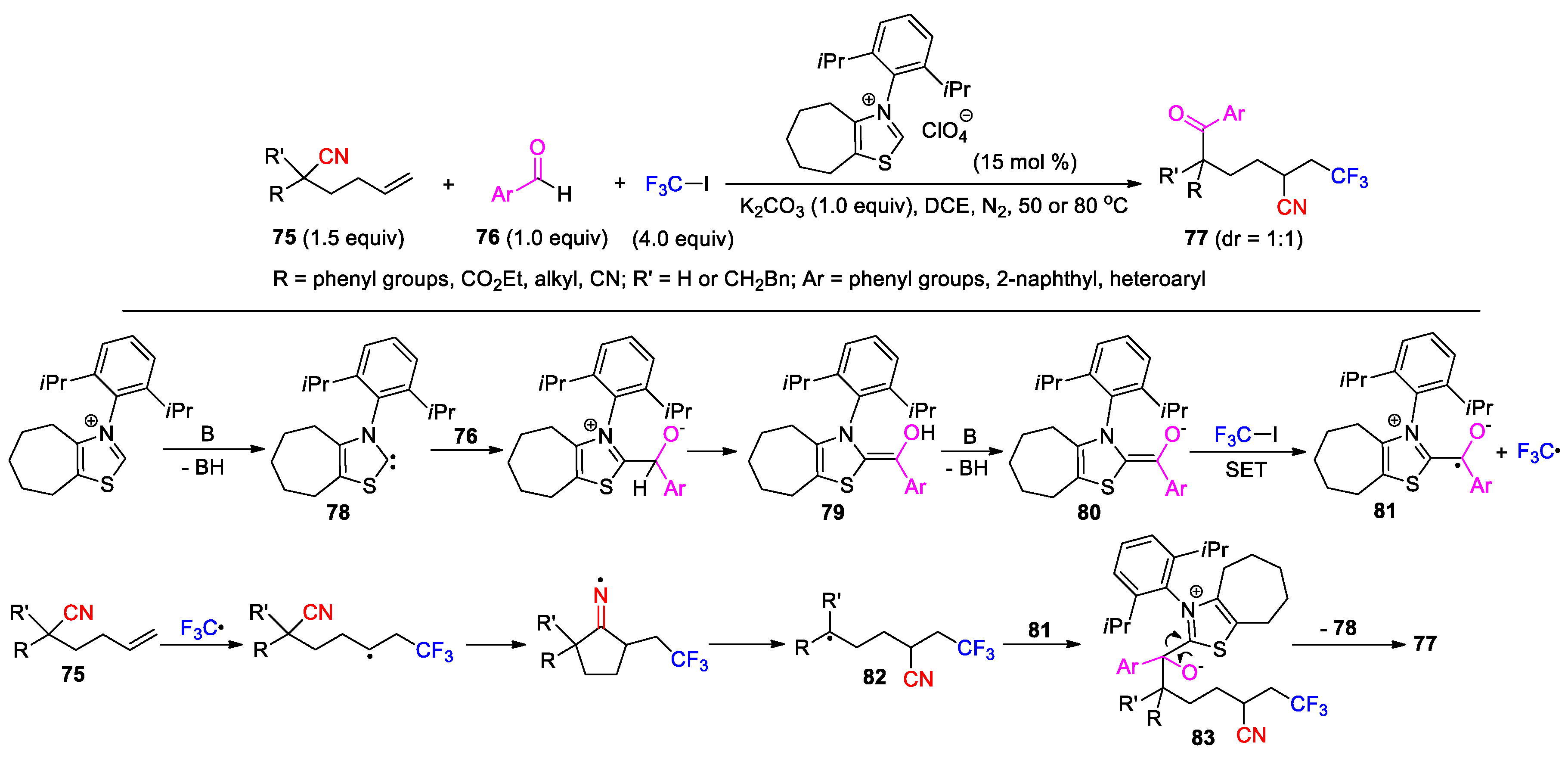

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.; Feng, J.; Du, D. Organocatalytic radical relay trifunctionalization of unactivated alkenes by a combination of cyano migration and alkylacylation. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 5395–5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfau, L.; Nichilo, S.; Molton, F.; Broggi, J.; Tomás-Mendivil, E.; Martin, D. Critical Assessment of the Reducing Ability of Breslow-type Derivatives and Implications for Carbene-Catalyzed Radical Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 26783–26789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

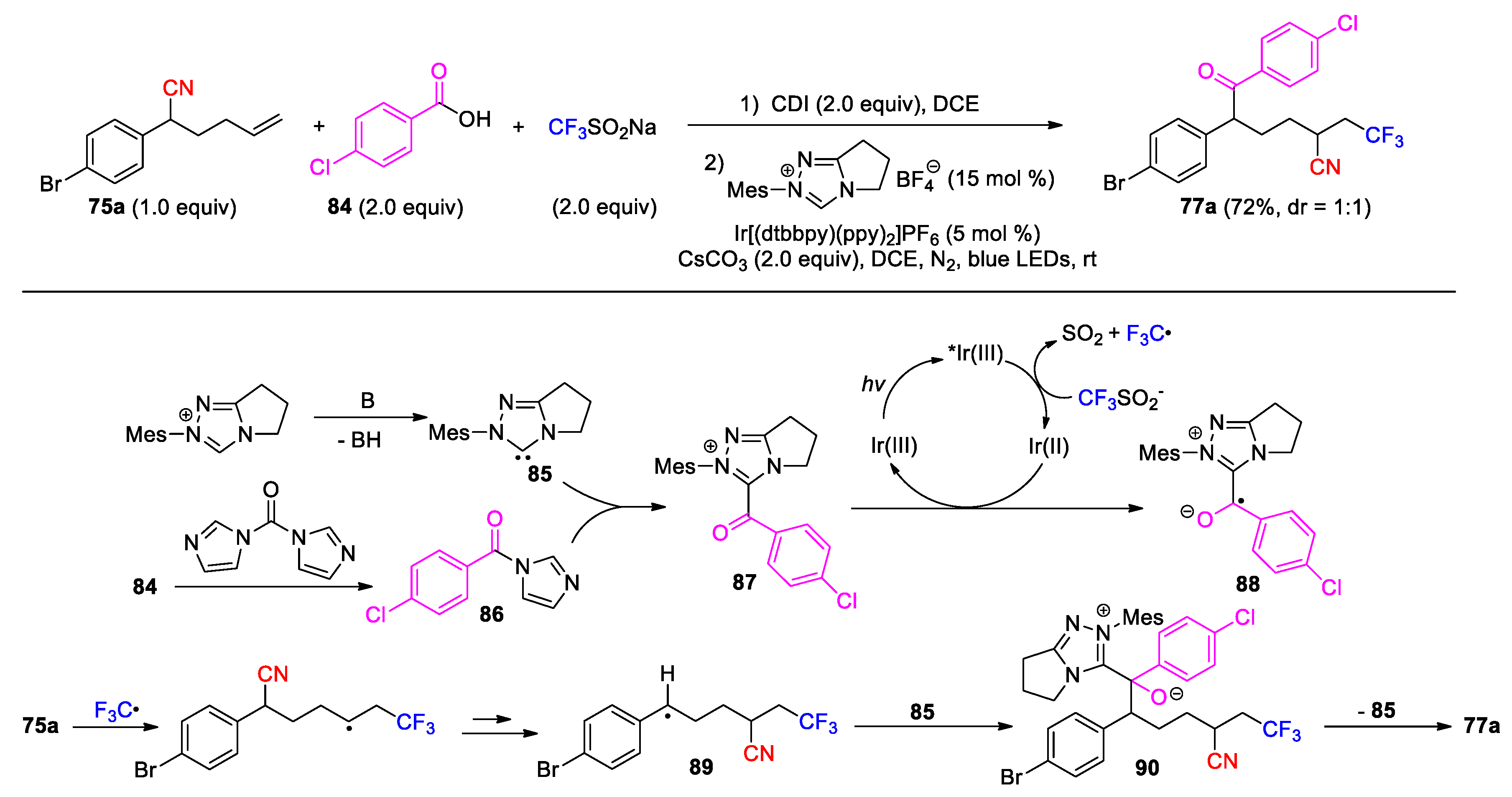

- Feng, J.-Q.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Ni, A.; Wei, Z.; Du, D.; Feng, J. Dual visible-light and NHC-catalyzed radical relay trifunctionalization of unactivated alkenes. Chem. Synth 2024, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Gu, C.; Li, Y.; Xie, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, K.; Zhu, Y. Photoredox Catalyzed Trifluoromethyl Radical-Triggered Trifunctionalization of 5-Hexenenitriles via Cyano Migration. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K. Photoredox-Catalyzed Trifunctionalization of 5-Heteroaryl-Substituted 1-Hexenes or 5-hexenenitriles via Remote Heteroaryl or Cyano Group Migration. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 3616–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouse, A.M.; Maheswari, B.; Akondi, S.M. Visible-Light Photoredox-Catalyzed Trifunctionalization of Unactivated Alkenes via Diamidation and Cyano Migration. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2025, 367, e202400987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chang, C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, C. Remote desaturation of hexenenitriles by radical-mediated cyano migration. Tetrahedron 2023, 131, 133228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

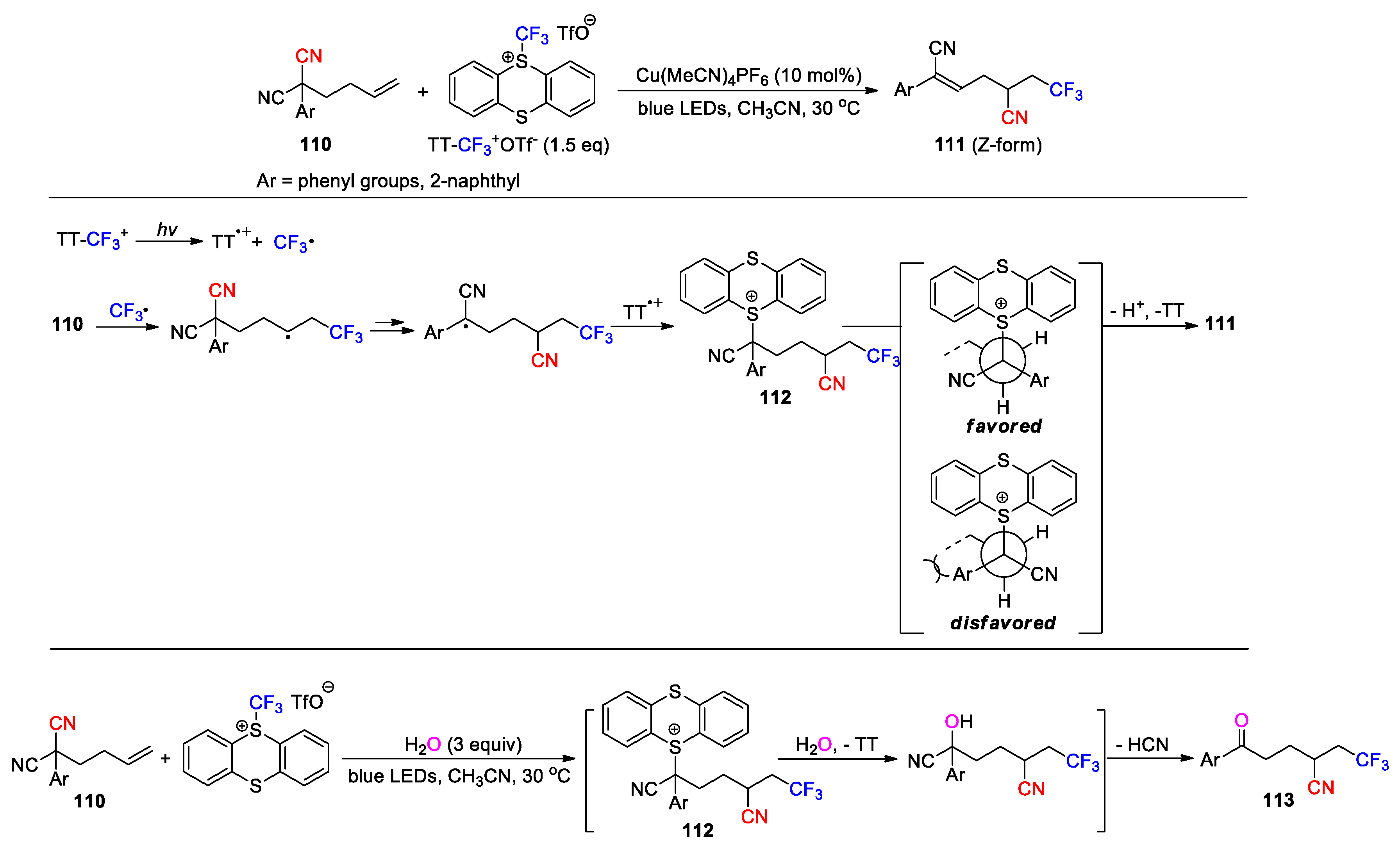

- Li, B.; Xing, D.; Li, X.; Chang, S.; Jiang, H.; Huang, L. Chemo-divergent Cyano Group Migration: Involving Elimination and Substitution of the Key α-Thianthrenium Cyano Species. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 6633–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Luo, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, D.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.-H.; Qi, X.; Yi, H.; Lei, A. Radical-triggered translocation of C-C double bond and functional group. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigenaga, S.; Shibata, H.; Tagami, K.; Kanbara, T.; Yajima, T. Eosin Y-Catalyzed Visible-Light-Induced Hydroperfluoroalkylation of Electron-Deficient Alkenes. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 14923–14929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; McMillan, A.J.; Constantin, T.; Mykura, R.C.; Juliá, F.; Leonori, D. Merging Halogen-Atom Transfer (XAT) and Cobalt Catalysis to Override E2-Selectivity in the Elimination of Alkyl Halides: A Mild Route toward contra-Thermodynamic Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14806–14813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

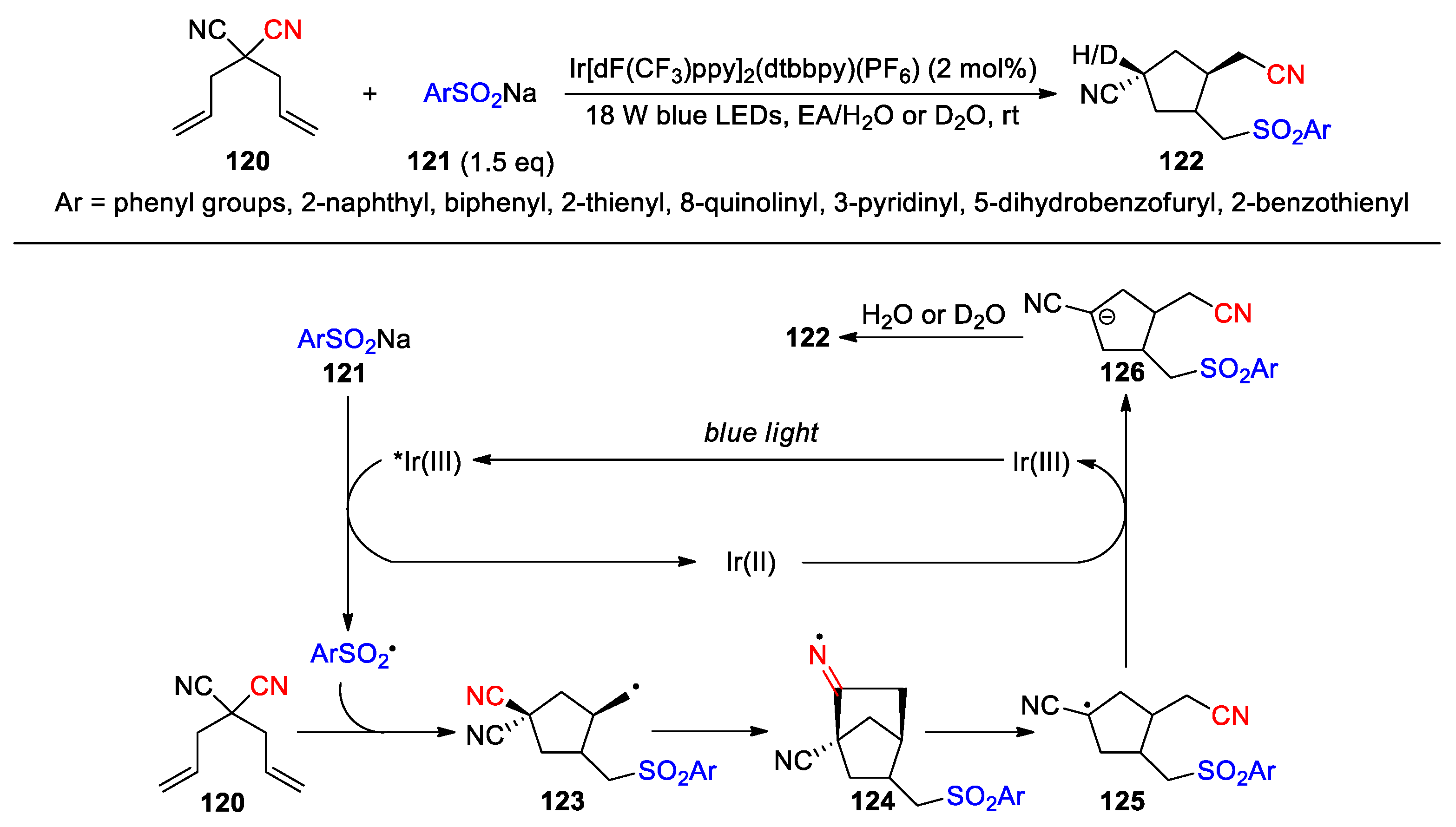

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, C. Radical Functionalization of 1,6-Diene via Transannular Cyano Migration: Synthesis of Polysubstituted Cyclopentanes. Chin. J. Chem. 2025, 43, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, H. Fluoroalkylative Ketonization of Malononitrile-Tethered Alkenes via Nickel Electron-Shuttle and Lewis Acid Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 4532–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

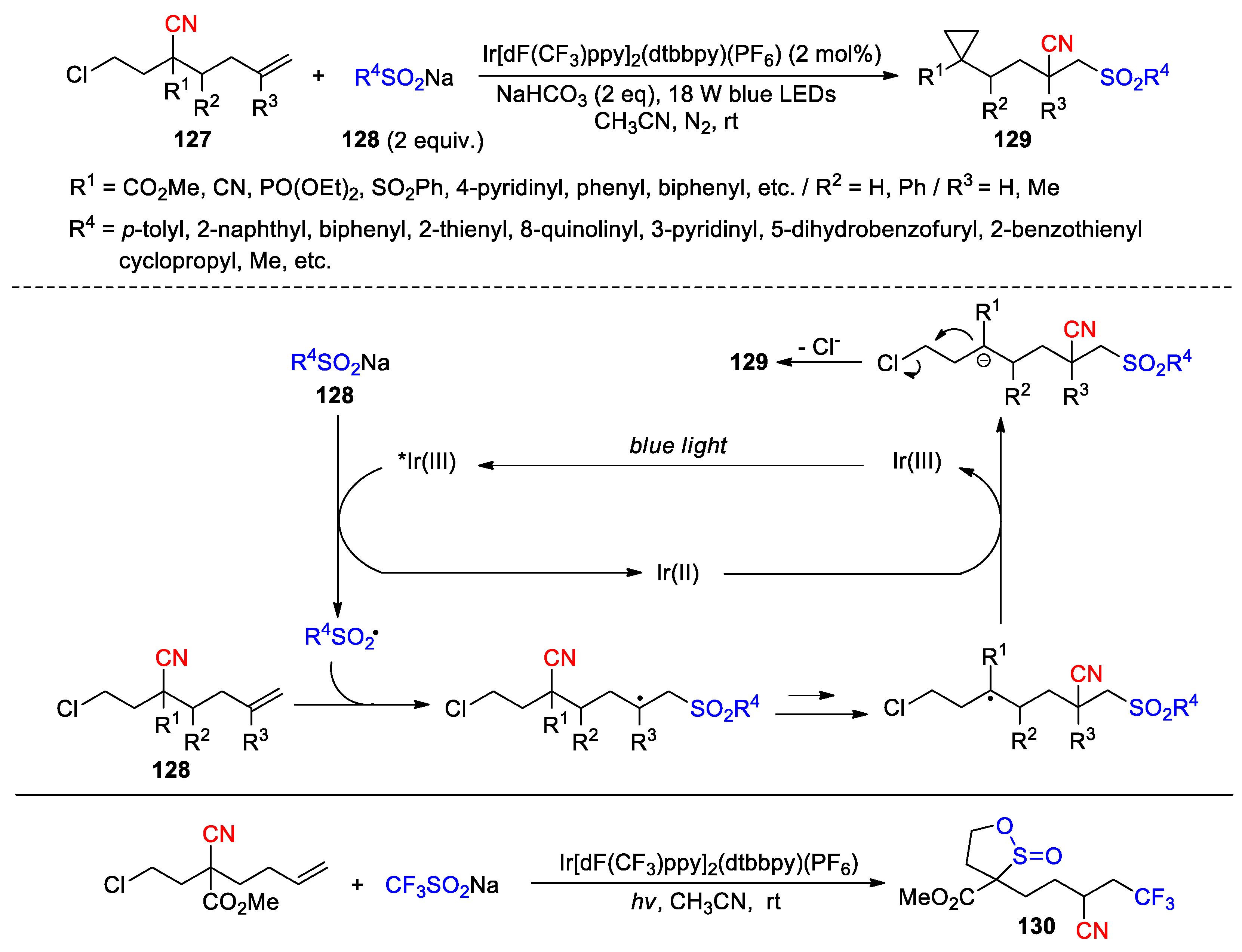

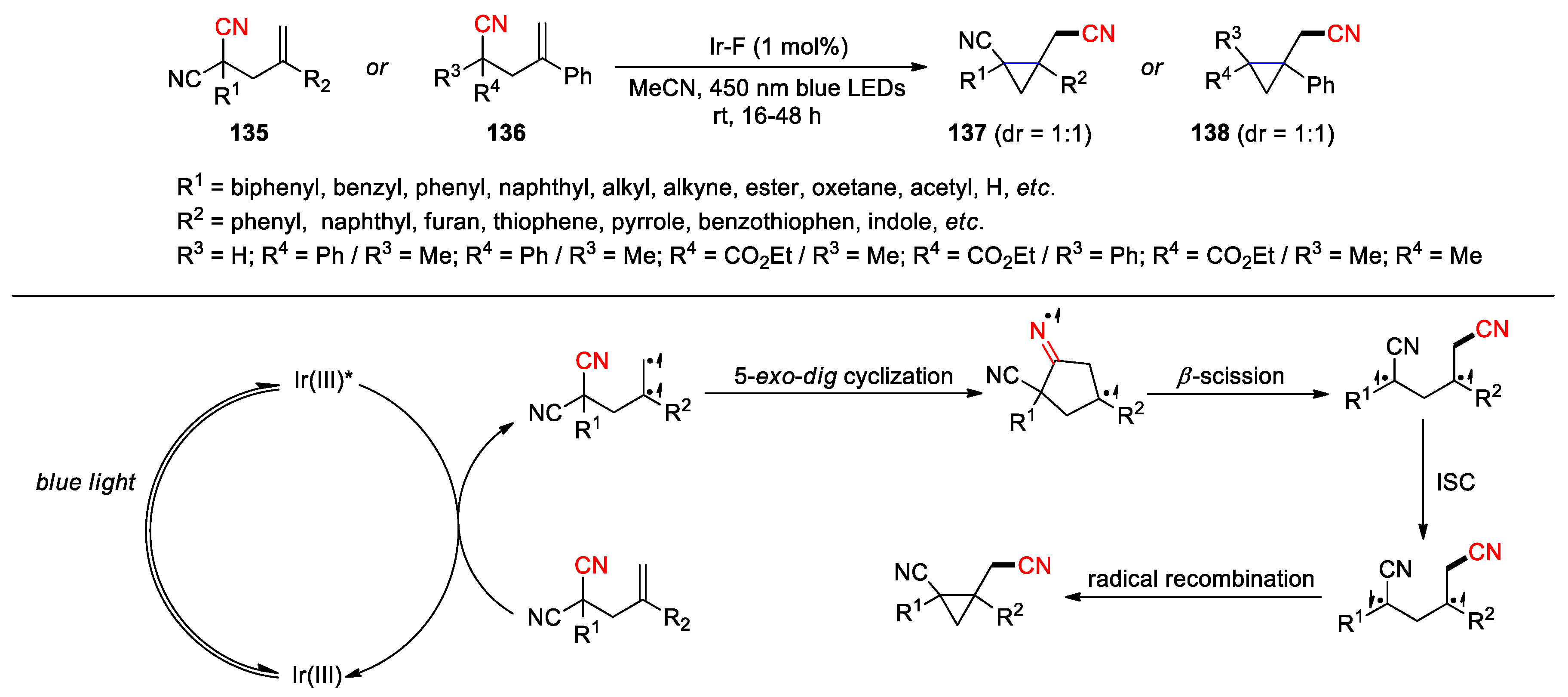

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, C. Cyano migration-mediated radical-polar crossover cyclopropanation. Sci. China Chem. 2024, 67, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Deng, H.-P. Alkylcyanation of Unactivated Alkenes with Protic C(sp3)-H Feedstocks via Radical-Initiated Intramolecular Cyano Group Migration Enabled by Photoredox/Brønsted Base Dual Catalysis. ChemPhotoChem 2025, 9, e202400282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

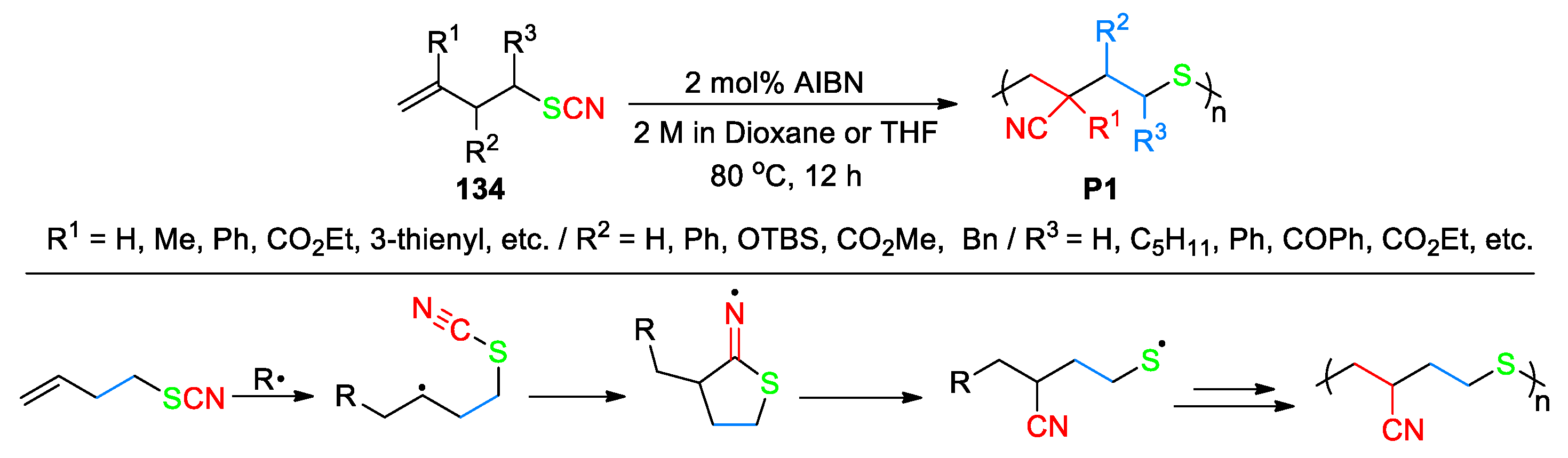

- Sato, T.; Miki, K.; Seno, M. Radical Group-Transfer Polymerization of 2-Thiocyanatoethyl Vinyl Ether. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 4166–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, M.; Imai, M.; Kamigaito, M. Synthesis of degradable polymers via 1,5-shift radical isomerization polymerization of vinyl ether derivatives with a cleavable bond. Polym. J. 2024, 56, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; Cui, F.; Yue, C.; Liu, H.; Sui, Y.; Ji, C.; Yan, J.; Li, Y. Radical Homopolymerization of Linear α-Olefins Enabled by 1,4-Cyano Group Migration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202402511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C. Switchable Radical Polymerization of α-Olefins via Remote Hydrogen Atom or Group Transfer for Enhanced Battery Performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202418350. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Dong, Q.-X.; Wen, S.-Y.; Ran, H.; Huang, H.-M. Di-π-ethane Rearrangement of Cyano Groups via Energy-Transfer Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 18210–18217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, J.; Pang, T.; Wu, G.; Zhong, F. Norrish-Yang-type cyclopropanation via functional group migration with photosensitizer at ppb loading. Chem Catal. 2024, 4, 101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

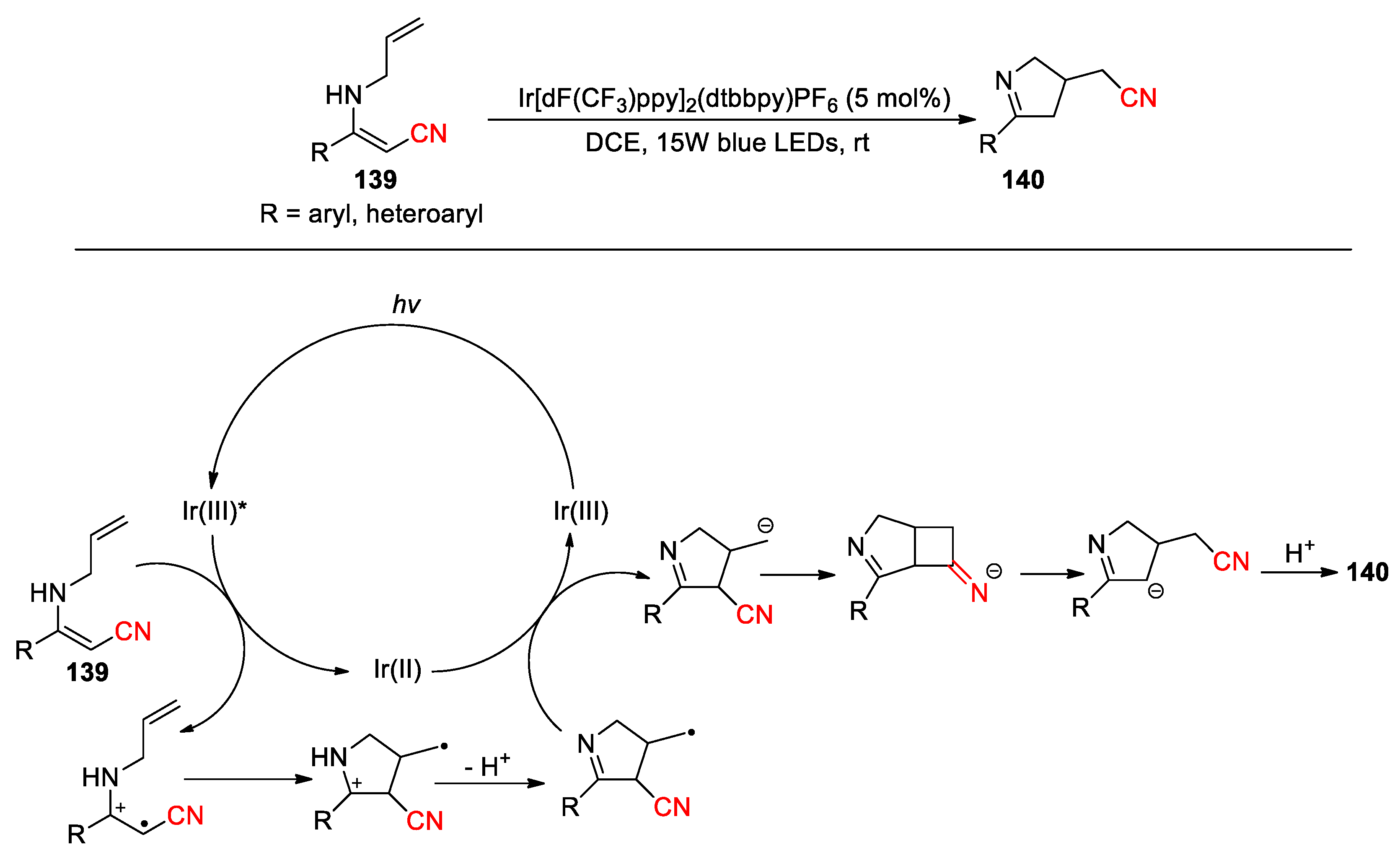

- Zheng, B.; Zhi, J.; Wang, N.; Zhang, D.; Shimakoshi, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Pan, L. Radical-triggered base-free 1,3-C → C migrations: chemodivergent synthesis of cyclic imines from N-allyl enamines. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

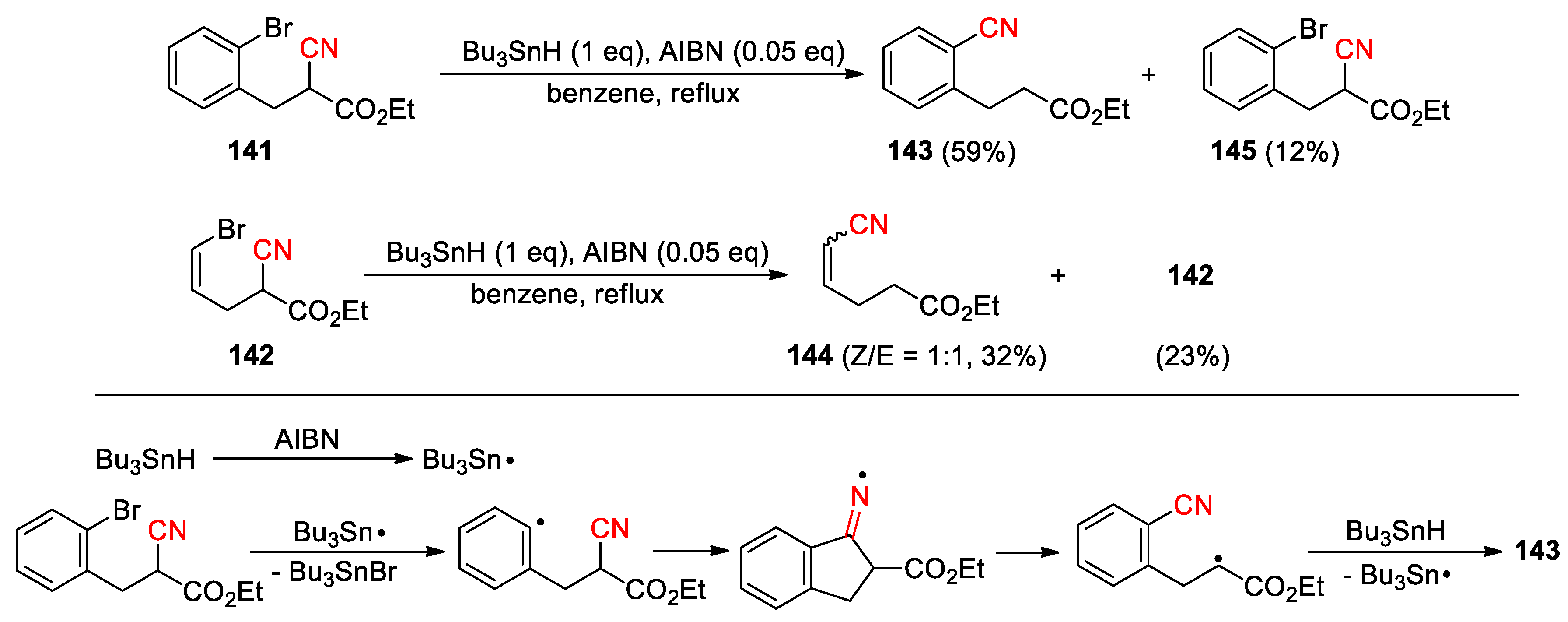

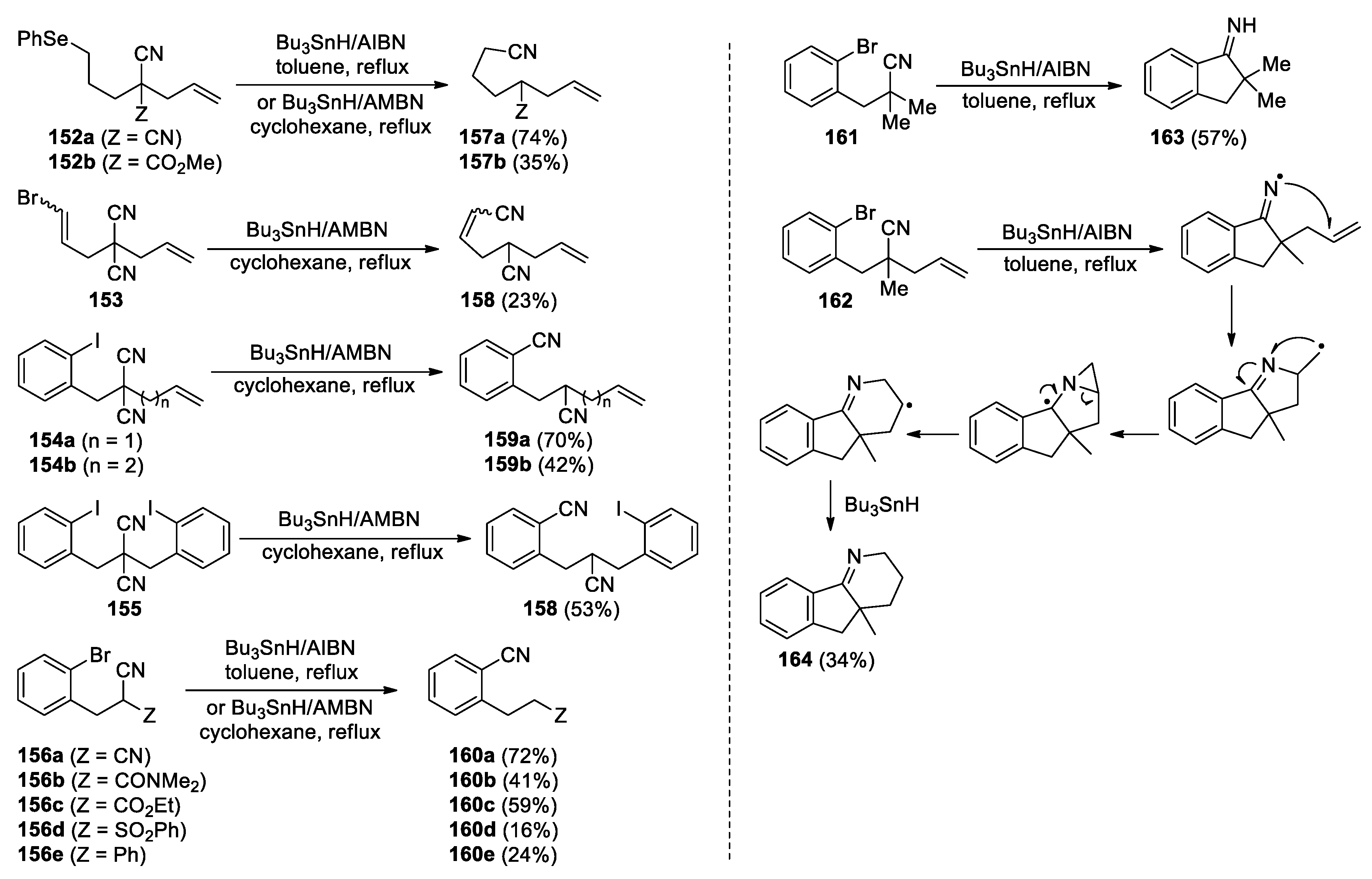

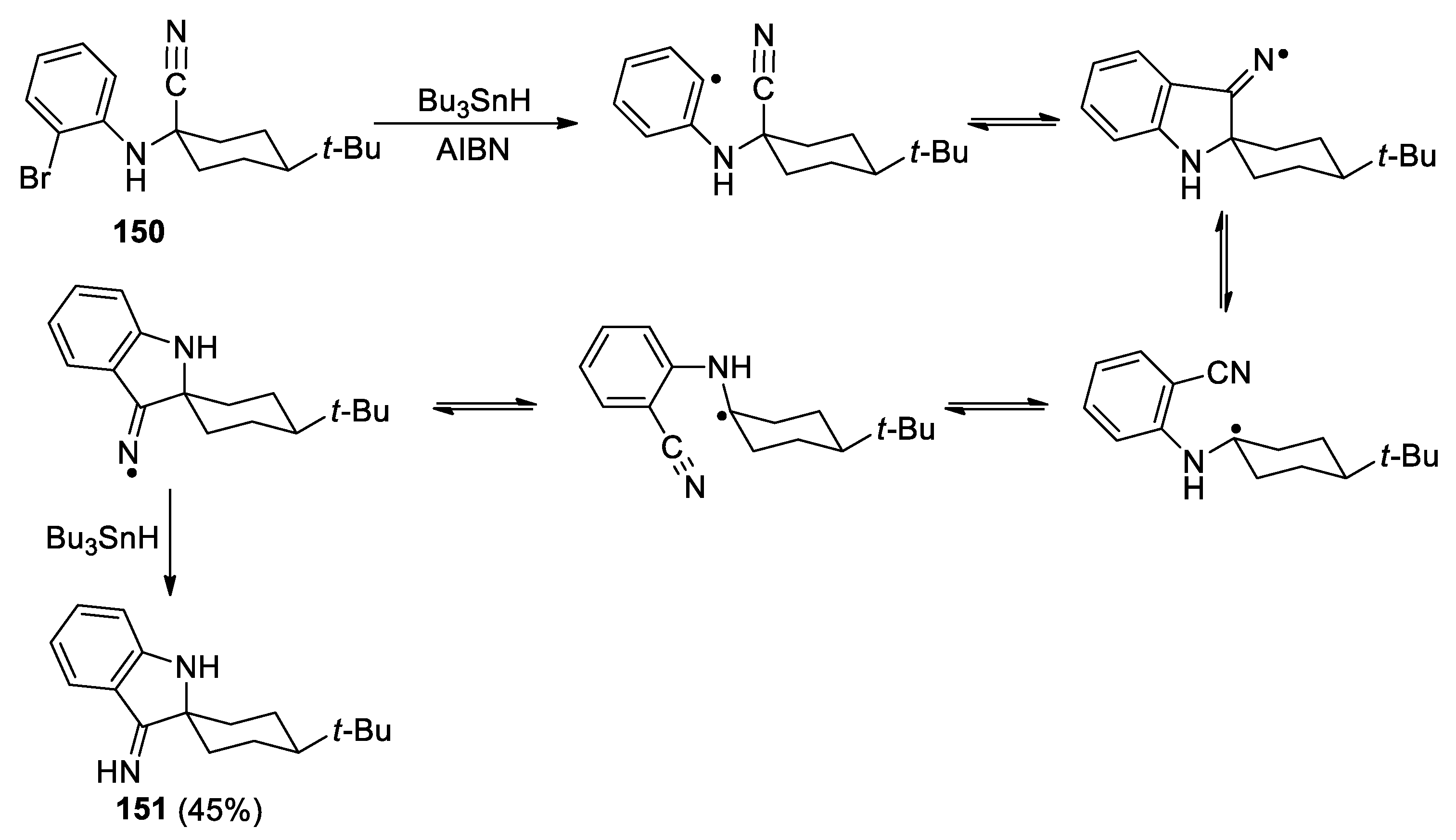

- Beckwith, A.L.J.; O'Shea, D.M.; Gerba, S.; Westwood, S.W. Cyano or Acyl Group Migration by Consecutive Homolytic Addition and β-Fission. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1987, 666–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckwith, A.L.J.; O'Shea, D.M.; Westwood, S.W. Rearrangement of Suitably Constituted Aryl, Alkyl, or Vinyl Radicals by Acyl or Cyano Group Migration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 2565–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

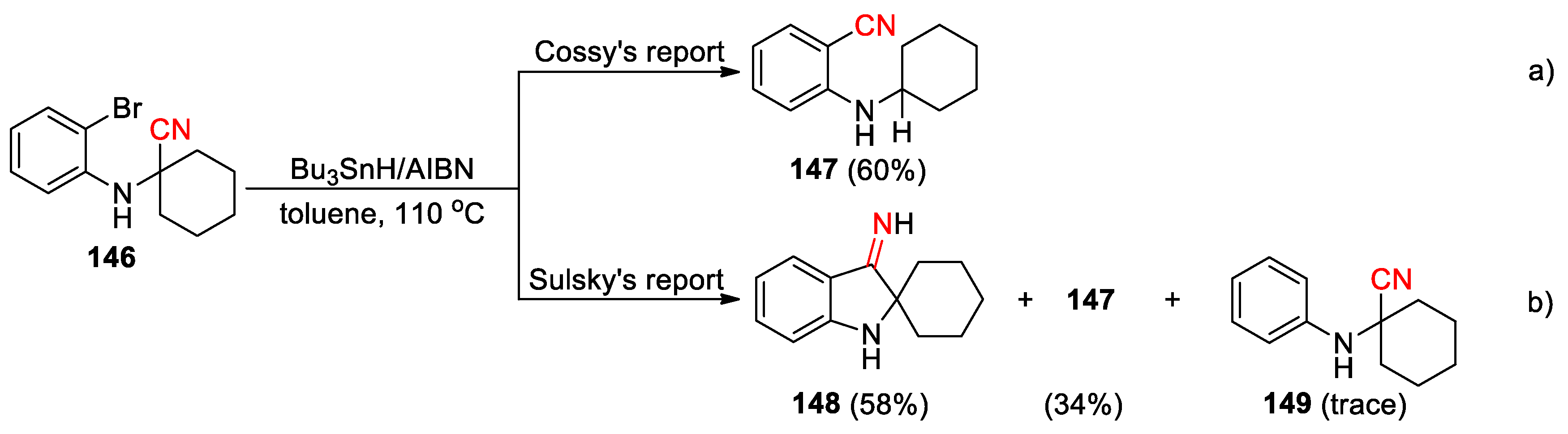

- Cossy, J.; Poitevin, C.; Pardo, D.G.; Peglion, J.L. Synthesis of 2-(Alkylamino)benzonitriles from α-(Bromoarylamino)nitriles. Synthesis 1995, 1368–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulsky, R.; Gougoutas, J.Z.; DiMarco, J.; Biller, S.A. Conformational Switching and the Synthesis of Spiro[2H-indol]-3(1H)-ones by Radical Cyclization. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 5504–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, W.R.; Bridge, C.F.; Brookes, P. Radical cyclisation onto nitriles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 8989–8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

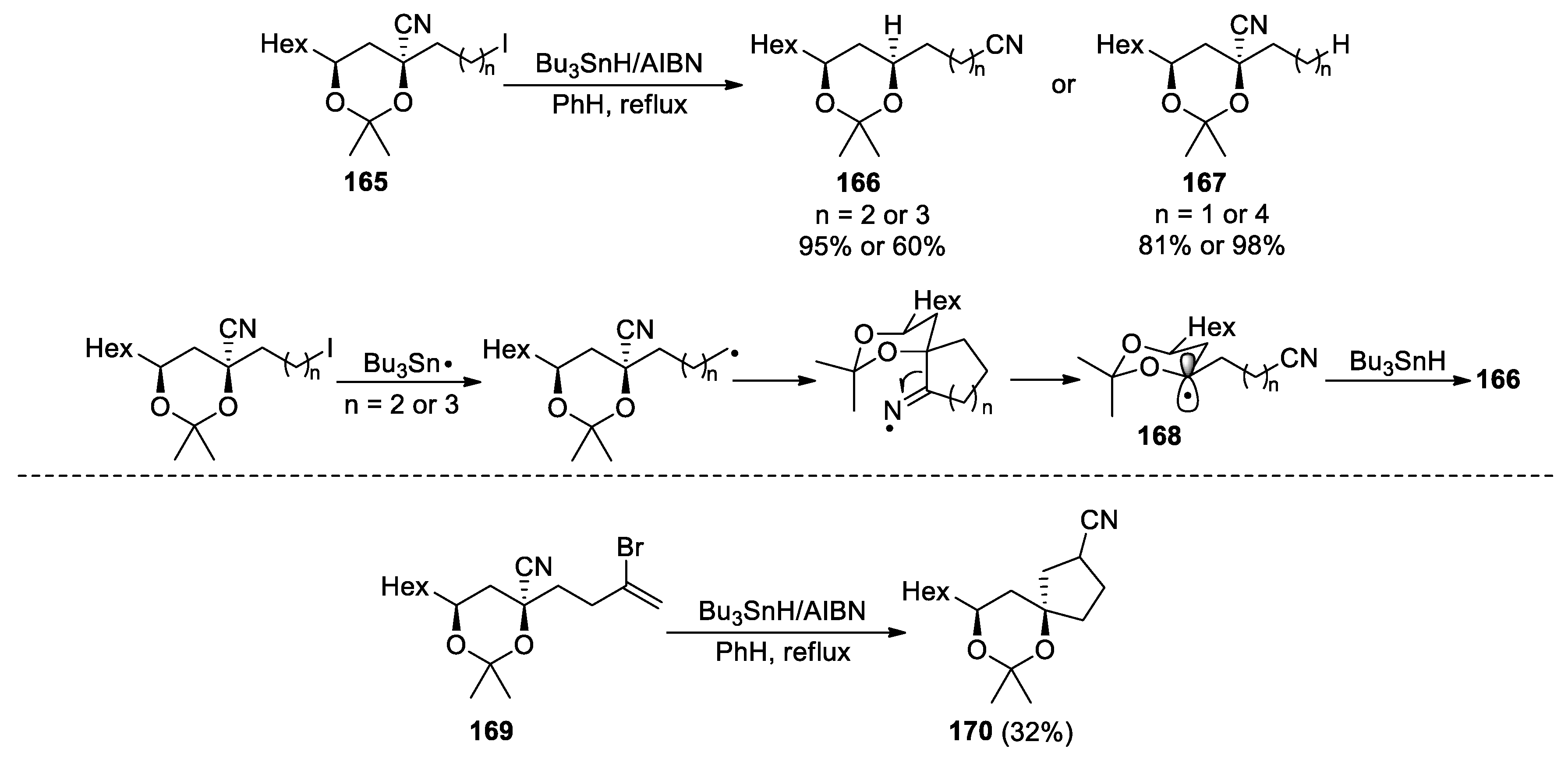

- Ryclmovsky, S.D.; Swenson, S.S. Tandem Radical Nitrile Transfer-Cyclization Reactions of 1,3-Dloxane-4-Nltriles: Synthesis of Spirocyclic Systems. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 16489–16502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

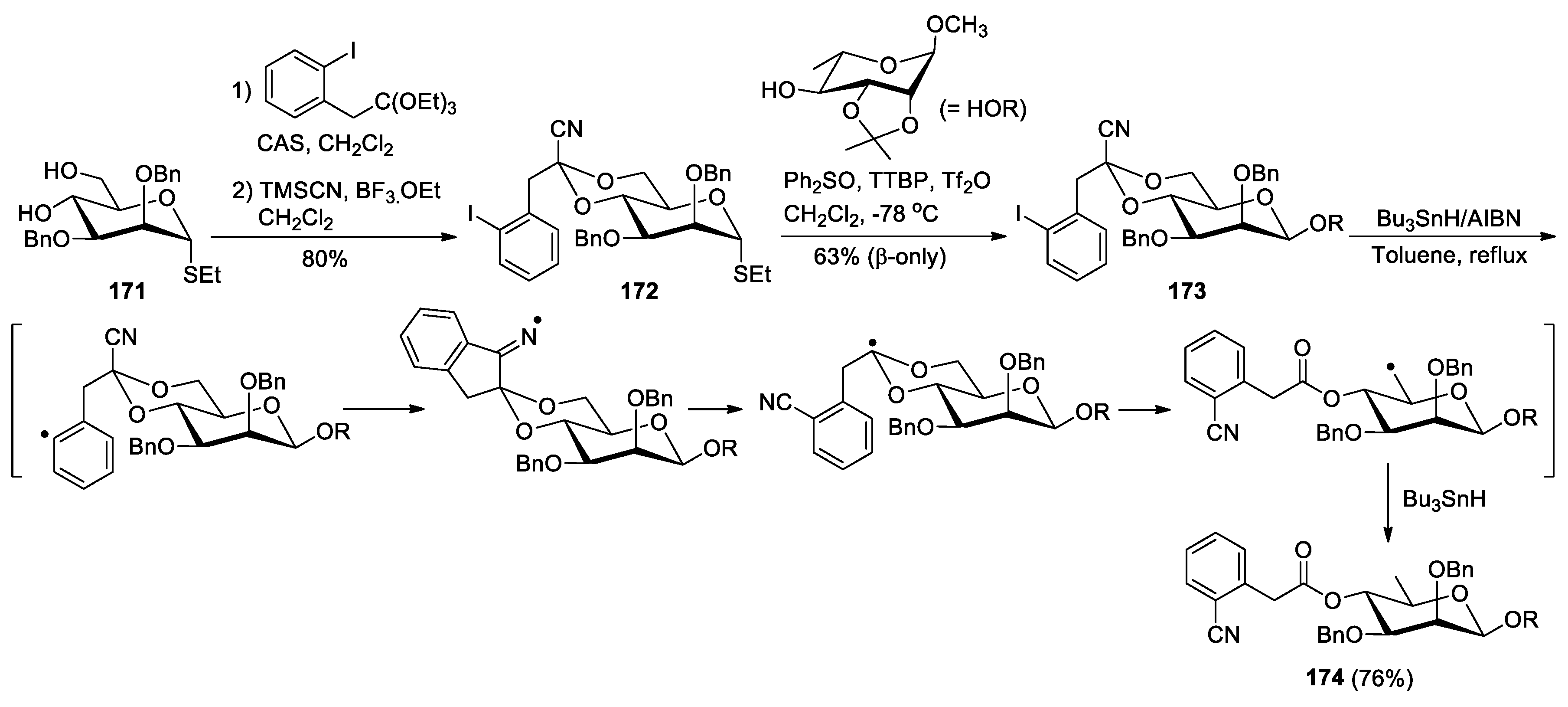

- Crich, D.; Bowers, A.A. 4,6-O-[1-Cyano-2-(2-iodophenyl)ethylidene] Acetals. Improved Second-Generation Acetals for the Stereoselective Formation ofβ-D-Mannopyranosides and Regioselective Reductive Radical Fragmentation to β-D-Rhamnopyranosides. Scope and Limitations. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 3452–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

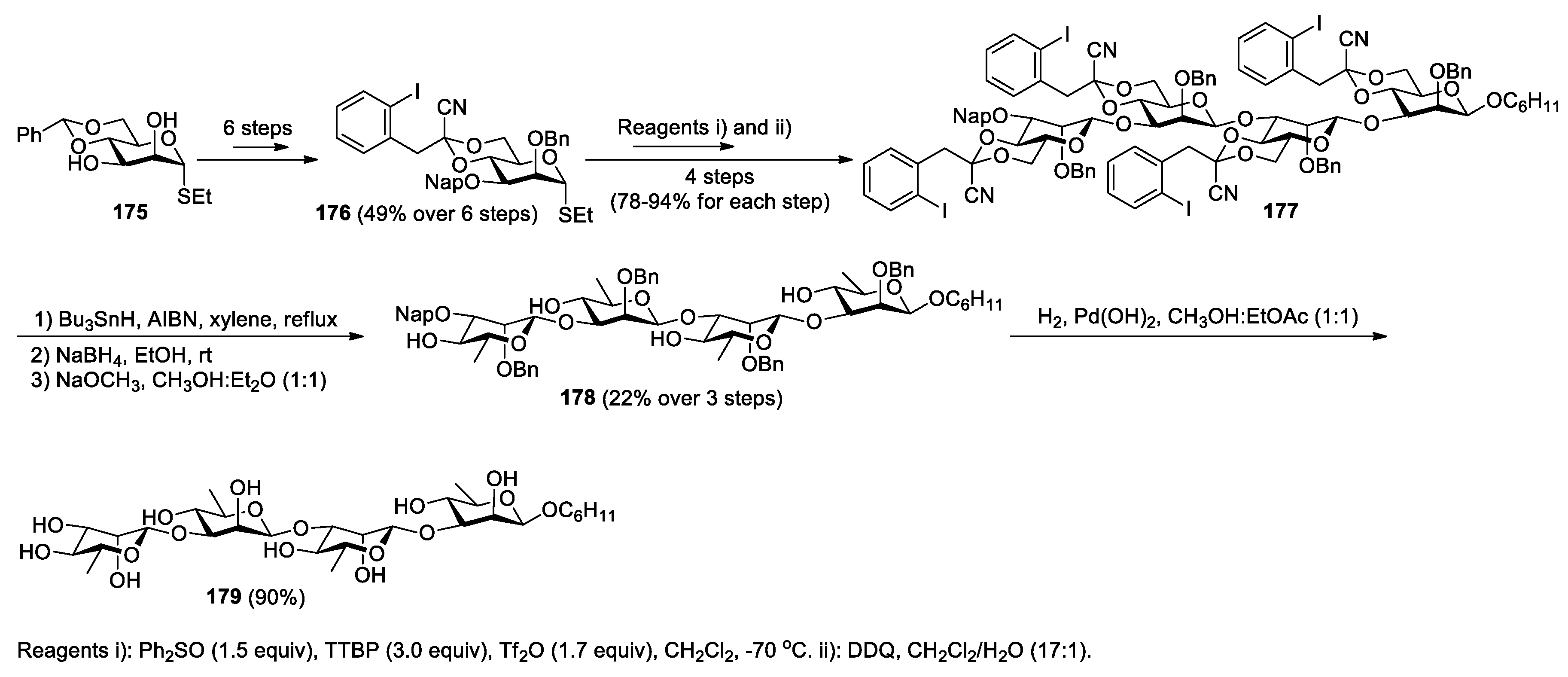

- Crich, D.; Bowers, A.A. Synthesis of a β-(1→3)-D-Rhamnotetraose by a One-Pot, Multiple Radical Fragmentation. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4327–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

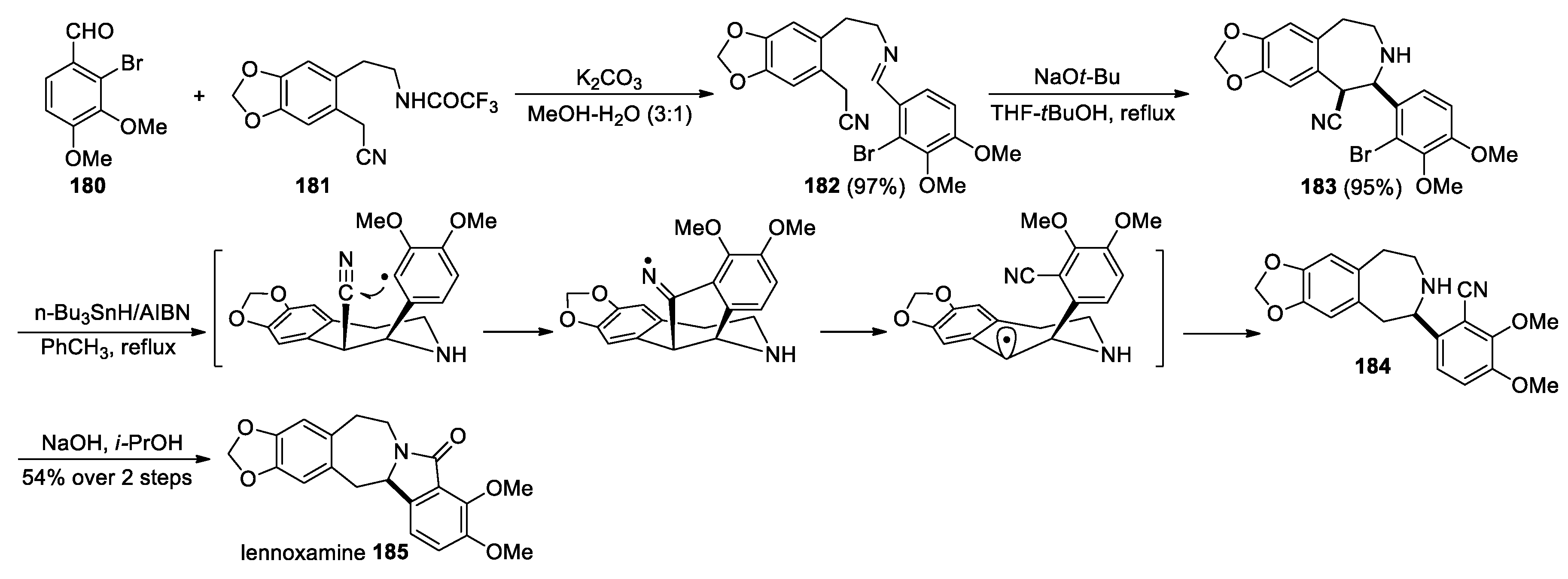

- Onozaki, Y.; Kurono, N.; Senboku, H.; Tokuda, M.; Orito, K. Synthesis of Isoindolobenzazepine Alkaloids Based on Radical Reactions or Pd(0)-Catalyzed Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 5486–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

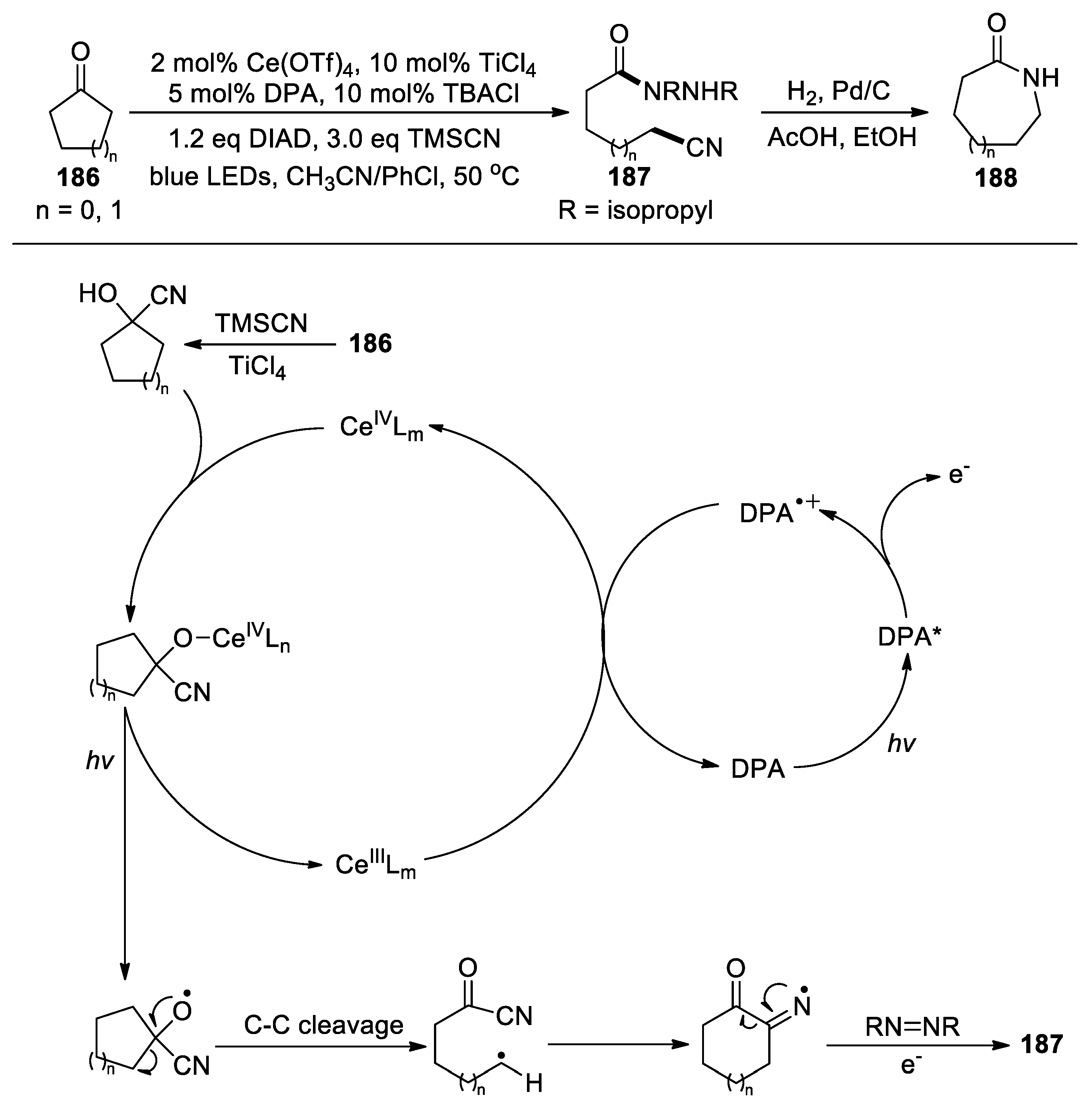

- Chen, Y.; Du, J.; Zou, Z. Selective C-C Bond Scission of Ketones via Visible-Light-Mediated Cerium Catalysis. Chem. 2020, 6, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

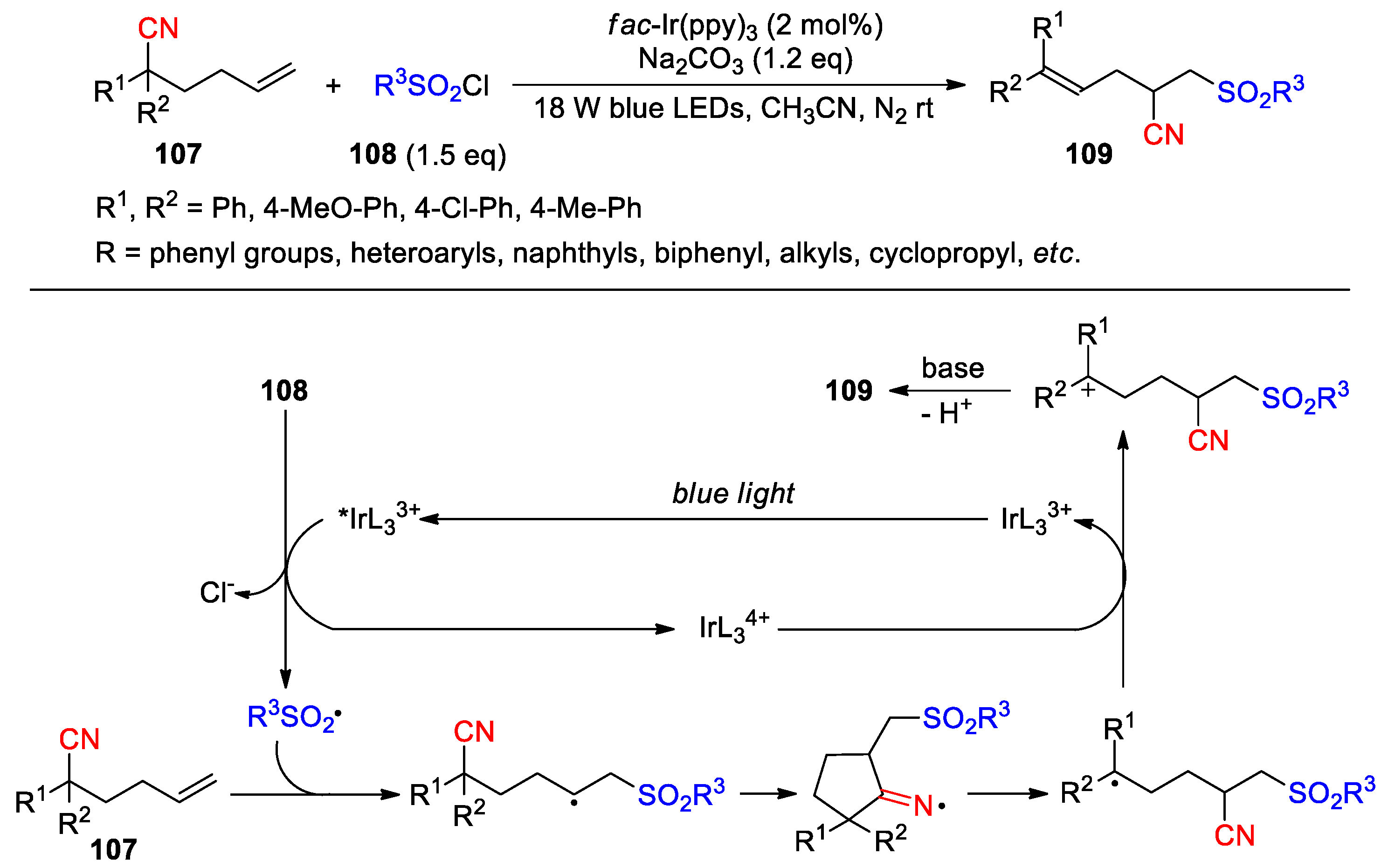

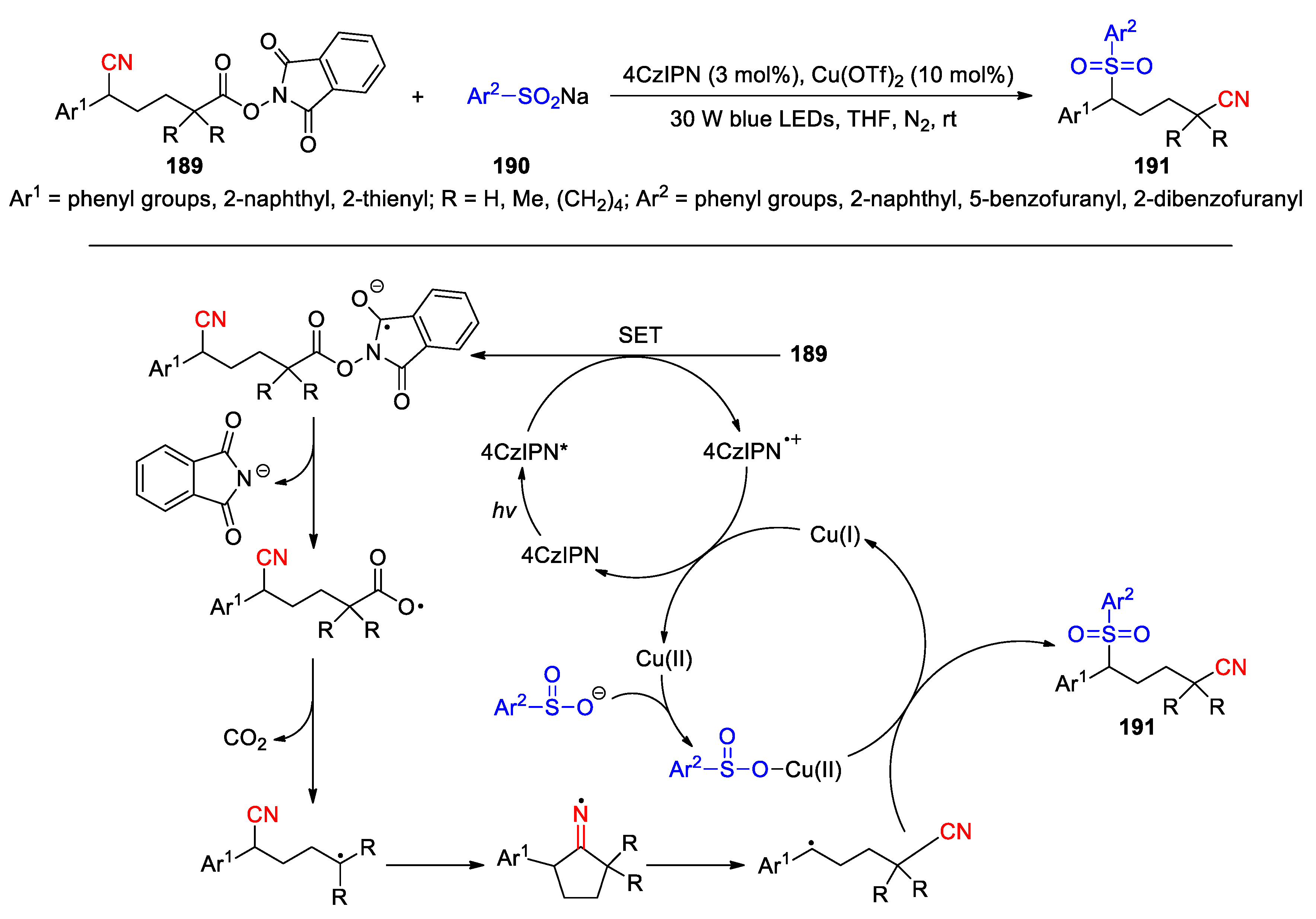

- Xie, X.; Li, Y.; Bo, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, K. Photoredox/Cu dual catalyzed 1,4-cyanosulfonylation enabled by remote cyano migration. Org. Chem. Front., 2024, 11, 4857–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

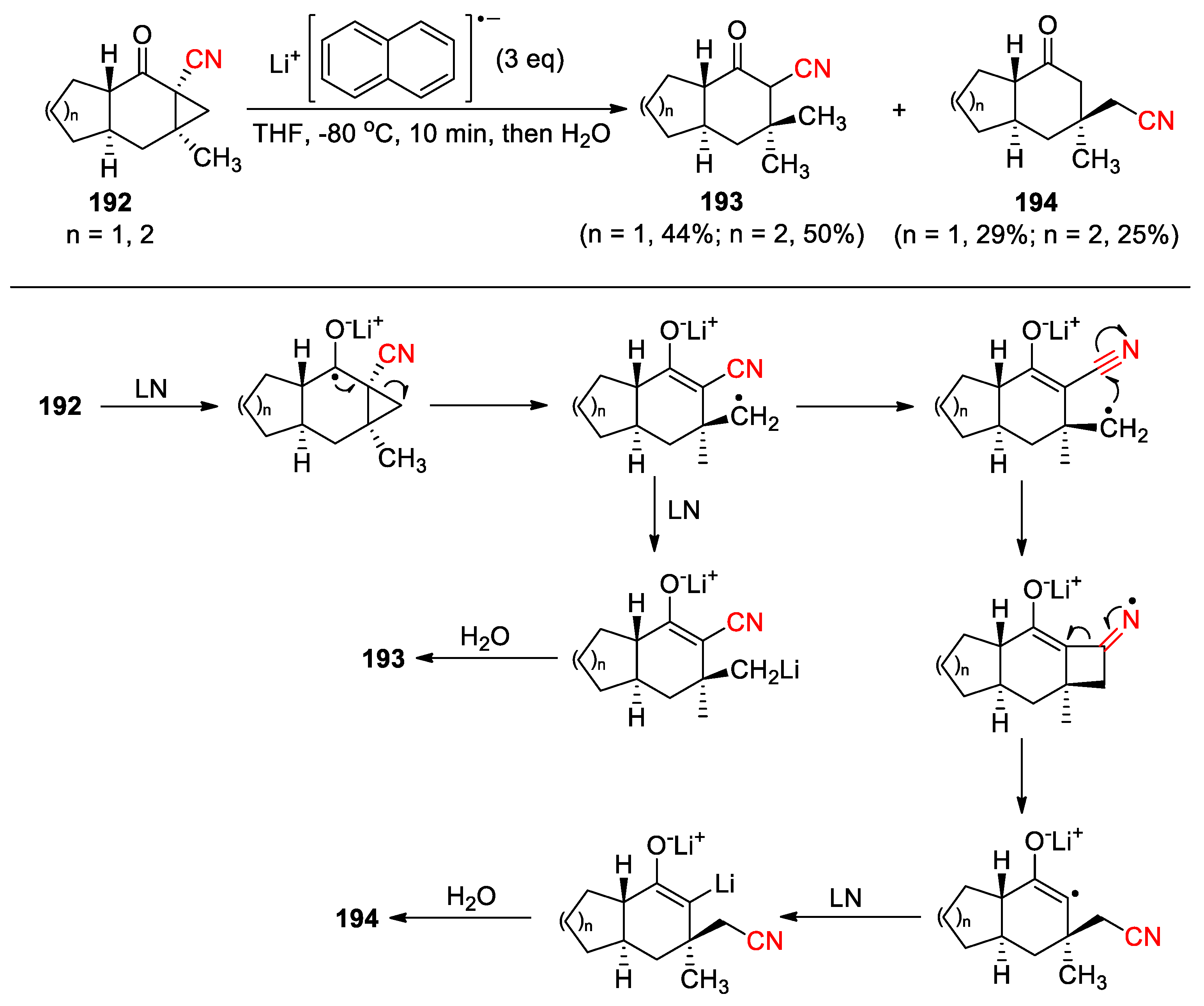

- Zhu, J.-L.; Wu, Y.-P. Rhodium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Cyclopropanation of α-Diazo β-Keto Nitriles Containing an Unsaturated Substituted Cycloalkyl Group. Synlett 2017, 28, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).