1. Introduction

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are common precancerous skin lesions that develop in areas of chronic ultraviolet radiation exposure. They are considered early indicators of squamous cell carcinoma [

1] and often coexist with subclinical changes in the surrounding skin, highlighting their key role in the broader process of skin field cancerization. Managing AKs effectively requires addressing both individual lesions and the entire affected skin field to reduce the risk of progression to invasive skin cancers [

2].

Clinical evaluation of AK involves assessing lesion count, distribution, and severity, which is crucial for determining baseline disease burden and guiding treatment decisions.

In routine clinical practice, assessing AK severity presents challenges. Most guidelines rely on lesion count, yet specialists often find this metric inconsistent [

3]. Additionally, studies indicate that complete patient clearance rates inversely correlate with baseline lesion numbers, yet many intervention studies fail to account for this baseline burden, potentially underestimating treatment benefits [

4,

5].

Accurate evaluation of treatment outcomes and long-term monitoring are critical to optimizing patient care. Current methods for assessing AK burden and treatment response, such as clinical scoring systems and qualitative indices, are subjective and prone to interobserver variability [

3,

6,

7]. These limitations underscore the need for more objective, reproducible, and comprehensive approaches that can enhance management strategies and improve the surveillance of AK over time.

Clinical photography has become an essential documentation tool in dermatology, particularly for diagnosing and monitoring conditions such as actinic keratoses (AKs). It allows clinicians to track changes in skin lesions over time, particularly in cases of extensive sun damage where AKs appear diffusely across large body surface areas [

8]. Clinical photography, coupled with image analysis, offers an efficient means of comprehensive documentation of AK clearance and/or new AK formation.

Detecting AK lesions in clinical photographs poses a significant challenge due to their subtle visual characteristics and ill-defined boundaries. Their size, shape, color, and texture variability further complicate the automated detection process. Early attempts at quantitatively assessing AK lesions using clinical photography faced challenges such as inconsistent illumination, lesion color diversity [

9], and the restriction of detection to preselected subregions of the photographed skin areas using a binary patch classifier for AK discrimination from healthy skin [

10,

11,

12]. These limitations hindered the reproducibility and accuracy of detection.

Leveraging an optimized convolutional neural network (AKCNN) as a patch classifier has significantly improved AK detection [

13]. However, a patch classifier processes small image patches (e.g.,50x50 pixels) independently, classifying each patch without explicit consideration of its surrounding spatial context. AKCNN is subject to manually predefined scanning areas necessary to exclude skin regions prone to false diagnoses, such as actinic keratosis, on clinical images. Unlike more distinct skin conditions, AK lesions often blend with the surrounding sun-damaged skin, making it challenging to delineate them precisely. These limitations prompted our earlier work, which explored semantic segmentation using a U-Net model with recurrent spatial processing in skip connections, thereby enhancing AK detection using clinical photographs [

14].

Accurate identification of AK burden within skin field cancerization often relies more on contextual cues—such as surrounding photodamage—than on the lesion’s appearance alone. This dependence on broader spatial information underscores the importance of models that integrate fine-grained local features and global context to effectively detect and segment AK lesions in a real clinical photography setting.

As semantic segmentation evolves rapidly, it is essential to continually reassess and refine architectural choices to meet the growing demands of complex clinical tasks, including AK burden evaluation and longitudinal monitoring in dermatology. In this context, the present study investigates architectural U-based enhancements that incorporate Transformers within spatial recurrent modules to enable more coherent and contextually informed segmentations.

Moreover, the high-resolution nature of the clinical photographs and the need to detect fine-texture AK regions impose additional limitations when implementing a regular semantic segmentation method. Training a segmentation network on high-resolution images requires either a huge memory capacity, which is often unavailable, or progressively reducing the image’s spatial size to fit into memory. However, down-sampling increases the risk of losing critical discriminative features. To address the challenge of segmenting AK lesions from clinical images, we have previously adopted the "tile strategy" [

14]. This method involves breaking down a large image into smaller tiles (crops), making predictions on these tiles, and then stitching them back together to form the final prediction. However, this process may result in the loss of image features shared between tiles, leading to under-segmentation or the missed detection of AK lesions. In the present work, we applied a Gaussian weighting technique to mitigate boundary effects during prediction merging.

The improvements in AK segmentation accuracy at crop and image levels were demonstrated through comparisons with results from state-of-the-art semantic segmentation models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Evolution of Transformer Architectures in Medical Image Segmentation

Initially developed for natural language processing, Transformers have increasingly demonstrated strong potential in computer vision. The introduction of the Vision Transformer (ViT) by Dosovitskiy et al. [

15] marked a significant shift, establishing the viability of Transformers for visual tasks. Unlike traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), Transformers leverage self-attention mechanisms to model long-range dependencies across the entire image, enabling a deeper understanding of spatial relationships and context. Although ViT was developed for natural image understanding, it quickly attracted attention for dense prediction tasks such as semantic segmentation due to its powerful global context modeling. However, early efforts to directly apply pure Transformer architectures to pixel-wise segmentation encountered challenges, including high computational cost and limited spatial precision. To mitigate these issues, various Transformer variants were introduced. The Swin Transformer [

16] improved computational efficiency and spatial locality by computing self-attention within shifted windows. Other variants, such as Pyramid Vision Transformer (PVT) [

17] and LeViT [

18], further optimized the balance between resolution and context modeling. These advances expanded the feasibility of integrating Transformers into medical segmentation tasks, paving the way for more practical and effective designs.

Since its introduction, U-Net has inspired numerous enhanced variants, demonstrating its widespread adoption in medical image segmentation [

19,

20]. The rise of Transformer architectures has further driven the development of hybrid models that combine U-Net’s strengths with global attention mechanisms. Review papers in the bibliography reflect this rapid evolution and highlight the growing impact of these hybrid approaches in the medical field [

21,

22,

23].

One of the earliest and most influential examples is TransU-net, which integrates a Vision Transformer (ViT) module into the U-Net encoder [

24]. In this architecture, a convolutional neural network (CNN) backbone is first employed for local feature extraction, followed by the ViT component, which captures long-range dependencies across the spatial domain. More recently, the TransU-net framework has been extended to include Transformer modules that can be flexibly inserted into the U-Net backbone, resulting in three hybrid configurations: Encoder-only, Decoder-only, and Encoder+Decoder. This modular design allows users to tailor architecture more easily to specific segmentation tasks [

25].

Following TransU-net, several variants explored different ways to integrate Transformer blocks. Swin-Unet [

26] replaced ViT with Swin Transformer blocks to enable efficient, hierarchical, and windowed attention across scales. DS-TransUNet [

27] extended this concept by utilizing Swin Transformers in both the encoder and decoder paths, with dual-branch interactions to enhance multi-scale consistency. UCTransNet [

28], in contrast, focused on the skip connections, replacing them with a channel transposition and attention fusion mechanism.

Most recently, HmsU-Net [

29] was proposed as a multi-scale U-Net architecture that integrates CNN and Transformer blocks in parallel at both the encoder and decoder. Each CNN-Trans block processes features through two branches, one convolutional and one Transformer-based, and fuses them using a multi-scale feature fusion module. A cross-attention mechanism further enhances skip connections across levels, enabling stronger interaction between encoder and decoder representations. This design allows the network to effectively capture both local textures and global semantics [

29].

These models illustrate the diversity of Transformer integration strategies within the U-Net framework, ranging from encoder-only attention to full dual-path designs. Each variant reflects a unique attempt to balance spatial accuracy, global reasoning, and computational efficiency, making Transformer-enhanced U-Nets a powerful class of models for medical image segmentation.

2.2. AKtransU-net: Skip Connection Enforcement with Global Dependencies

Skip connections have been a cornerstone of U-Net-based architectures, effectively bridging the encoder and decoder by preserving spatial details [

30]. However, several studies have shown that plain skip connections, such as direct concatenation, can introduce semantic gaps between encoder and decoder features, negatively impacting segmentation performance. To address this, various models have rethought the design of skip connections. MultiResUnet [

31], for example, instead of simply concatenating the feature maps from the encoder stages to the decoder stages, first passes them through a chain of convolutional layers with residual connections and then concatenates them with the decoder features. In another architecture, IBA-U-Net [

32], the researchers, to solve the difference between the feature map extracted from the encoding path and the output feature map of the upper layer in the decoding path, introduced the Attentive Bidirectional Convolutional Long short-term memory block (BConvLSTM), which uses the BConvLSTM block to extract bidirectional information, and then uses the Attention block to compare BConvLSTM output elements to different degrees to highlight the salient features in the skip connection. UCTransNet [

28] and FAFS-UNet [

33] have introduced cross-attention and feature selection modules to enrich skip connections with context-aware filtering and semantic alignment, thereby enhancing their capabilities. Similarly, HmsU-Net [

34] improved the communication between the encoder and decoder by introducing a Cross-Attention module that fuses features from the last three encoder stages and distributes them to the decoder.

Inspired by these developments and based upon our previous exploration of U-net variants for AK detection [

14], the proposed architecture adopts the view that skip connections should actively propagate feature maps enriched with global dependencies to the decoder stage. To achieve this, we apply ViT blocks [

15] to the encoder-derived feature maps at multiple scales. Passing the CNN feature maps through a Transformer block augments them with global relationships.

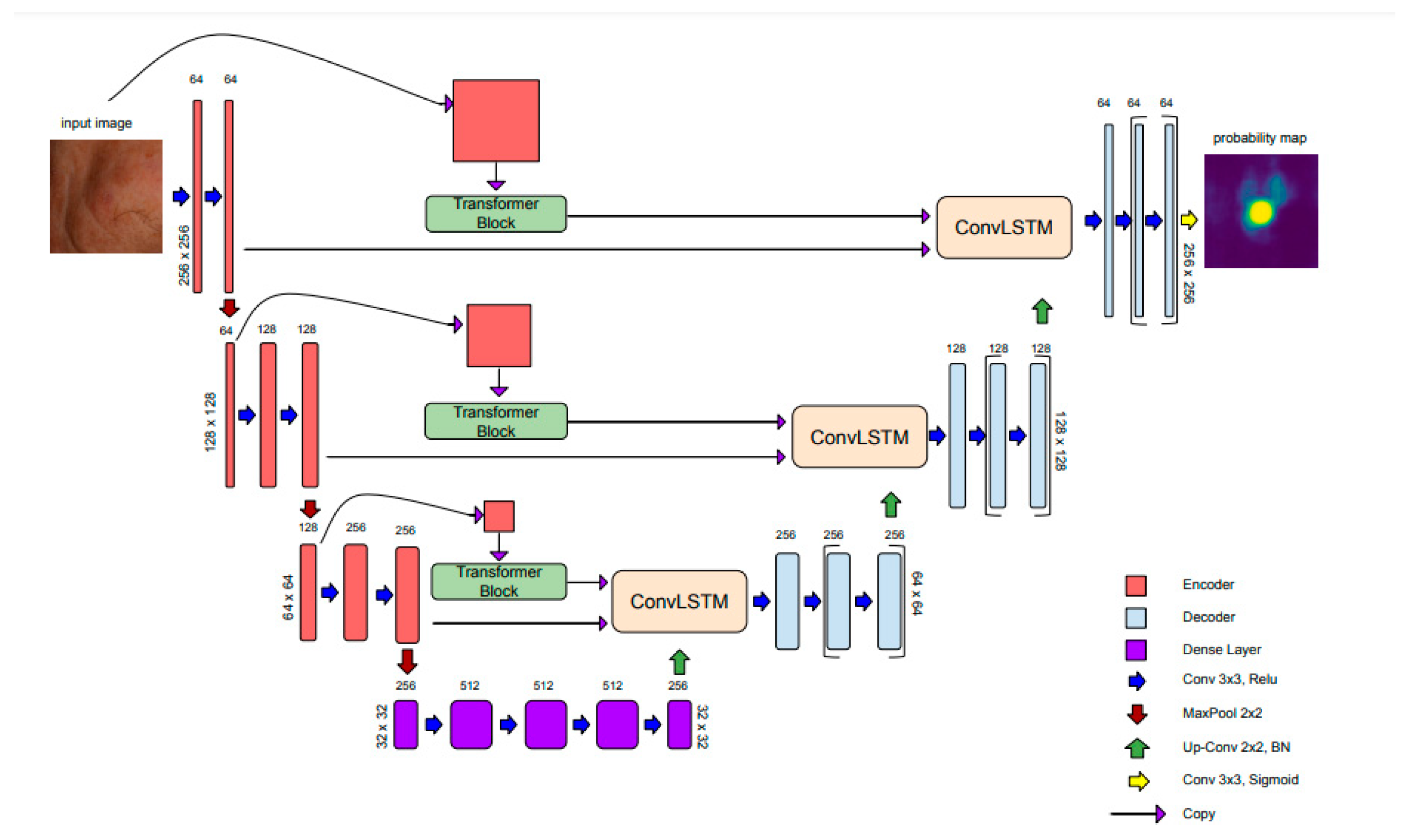

The output of each Transformer block is then passed into ConvLSTM modules within the skip connections, which process three inputs sequentially: the CNN encoder output, the Transformer features, and the upsampled decoder output. This design enables the network to detect lesions not only by analyzing local textures but also by leveraging their broader spatial context. The architecture is shown in

Figure 1.

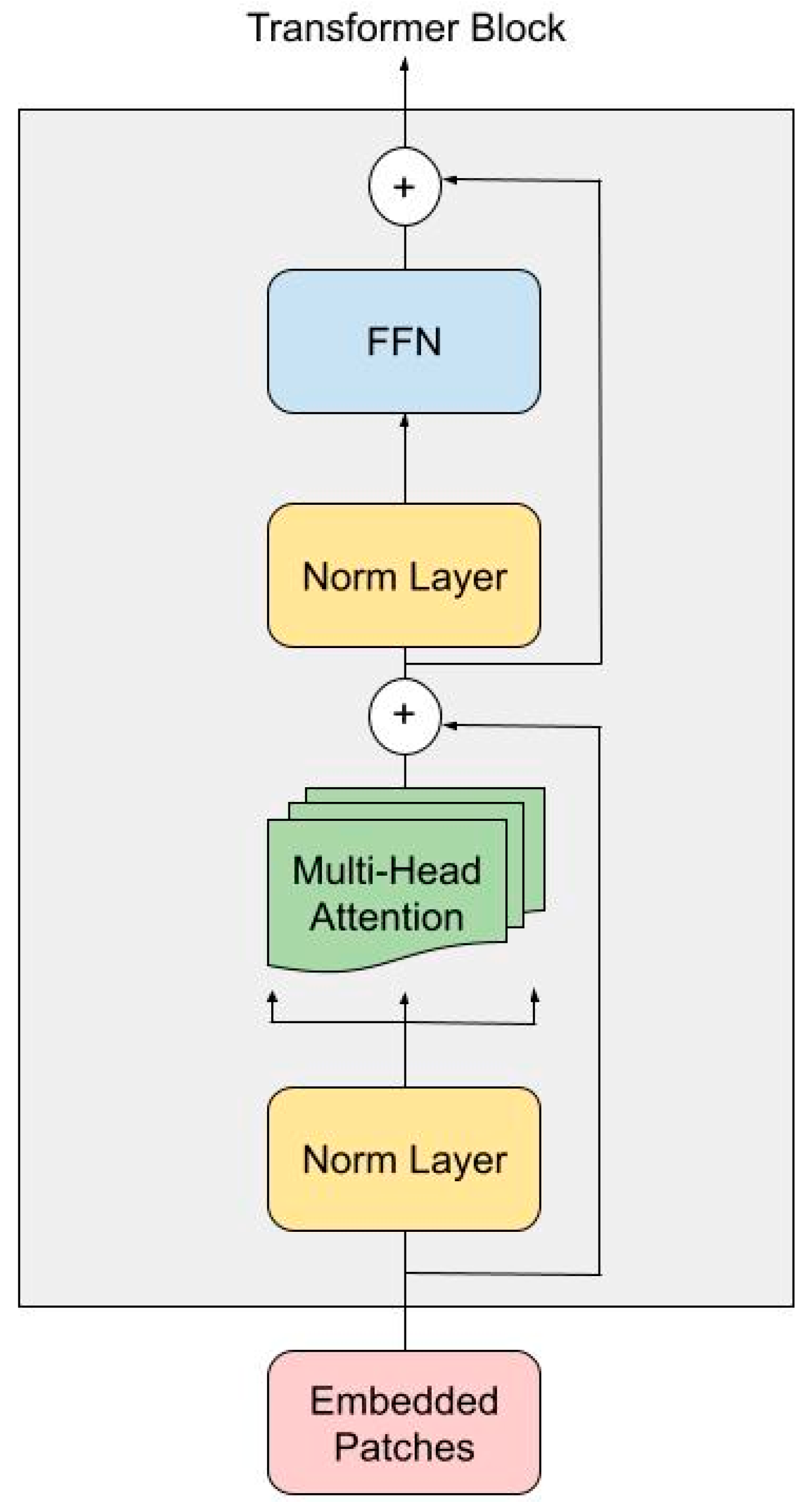

2.3. Transformer Encoder

In AKTransU-Net, three Transformer encoder blocks are integrated at progressively down-sampled scales within the encoding path. This design enhances the CNN-extracted features with global attention, enabling the model to capture long-range dependencies across the spatial domain.

Each Transformer encoder block follows a standard ViT configuration (

Figure 2), utilizing 16 attention heads (h = 16), and processes embedded tokens of size D = 1024. The encoder block consists of two sub-layers, each preceded by Layer Normalization and followed by a residual connection.

In the first sub-layer, the embedded patches are projected into sets of query (Q), key (K), and value (V) vectors through Multi-Head Self-Attention. For each head, attention is computed using scaled dot-product attention:

where

is the dimensionality of the key vectors calculated as follows:

The outputs from all attention heads are concatenated and passed through a linear projection. This is followed by a second Layer Normalization and a Feed-Forward Network composed of two linear layers with a non-linear activation function (Rectified Linear Unit). Finally, the output token sequence is reshaped back to its original spatial dimensions. This step ensures that the global context learned through attention is preserved while maintaining compatibility with the subsequent ConvLSTM and decoder layers.

2.4. ConvLSTM in Skip Connections for Spatial Refinement

ConvLSTM layers are a variation of LSTMs (Long Short-Term Memory networks) that extend the traditional LSTM by incorporating convolutional operations, making them well-suited for capturing spatial relationships in image data [

35,

36]. While ConvLSTMs are often used in spatiotemporal tasks, they can be effectively applied to purely spatial data by focusing on spatial interactions across feature maps. ConvLSTM modules have been integrated into U-Net skip connections to enhance the model’s capacity to reconstruct accurate segmentation maps [

32,

37,

38].

ConvLSTM consists of an input gate , an output gate a forget gate a memory cell and the hidden state . The gates control access, update, and clear the memory cell.

For an input

the ConvLSTM process is formulated as follows:

In the final step t, the refined feature map capturing spatial dependencies is passed to the decoder. and correspond to the 2D convolution kernel of the input and hidden states, respectively. (*) represents the convolution operation and bullet the Hadamard function (element-wise multiplication), respectively. are the bias terms, and sigma is the sigmoid function.

In our architecture, the ConvLSTM layer processes the CNN encoding, Transformer encoding, and upsampled decoder feature map in a sequential three-step process. In the first step, the encoder’s CNN-based feature map is processed. In the second step, the Transformer-based representation is incorporated, using the hidden state from the previous step. In the third and final step, the upsampled decoder feature map is refined, leveraging the accumulated spatial memory from the earlier steps. This sequential integration allows the ConvLSTM to serve as a spatial refinement module, enhancing the consistency of skip connections. As a result, the decoder receives a richer combination of low- and high-level spatial information, leading to more precise and accurate segmentation.

2.5. Material

The use of archival photographic material for this study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee (IRB) of the University Hospital of Ioannina (Approval No.: 3/17-2-2015 [θ.17]). The study included 115 patients diagnosed with facial actinic keratosis (AK), comprising 60 males and 55 females, aged between 45 and 85 years, who attended the specialized Dermato-oncology Clinic of the Dermatology Department.

Facial photographs were captured with the camera positioned perpendicular to the target area, ensuring full coverage of the face from the chin to the hairline. High-resolution digital images (4016 × 6016 pixels) were obtained using a Nikon D610 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Nikon NIKKOR© 60mm f/2.8G ED Micro lens, following a protocol adapted from Muccini et al.[

39]. The camera was configured with an aperture of f/18, shutter speed of 1/80 sec, ISO 400, autofocus enabled, and white balance set to auto mode. A Sigma ring flash (Sigma, Fukushima, Japan) in TTL mode was mounted on the camera. Linear polarizing filters were placed in front of both the lens and the flash, aligned to create a 90° polarization angle between them, thereby minimizing surface reflection and enhancing lesion visibility.

Two dermatologists jointly reviewed and annotated the photographs, reaching a consensus on the regions affected by AK. Multiple images were captured for each patient to ensure comprehensive lesion coverage and to provide different perspectives of individual lesions. This process resulted in a total of 569 clinically annotated photographs.

Given the high spatial resolution of the images (4016 × 6016 pixels), model training was performed using rectangular crops (tiles). The crop size was chosen to preserve sufficient contextual information. To this end, the images were initially downscaled by a factor of 0.5, and 512 × 512-pixel crops were extracted using translation-based lesion bounding boxes. This approach ensured the resulting image tiles included lesions in varied positions and captured a diverse range of perilesional skin contexts [

14].

A total of 510 photographs from 98 patients were used for training, yielding 16,488 translation-augmented image crops. Approximately 20% (3,298 crops), corresponding to five patients, were set aside for validation. An independent test set comprising 59 photographs from 17 patients produced 403 central lesion crops for model performance evaluation.

2.6. Evaluation

To demonstrate the anticipated improvements of AKtransU-net in detecting AK lesions, we present comparative results using both CNN-based and CNN-transformer hybrid architectures at the crop level. One of the CNN models evaluated was a deeper variant of AKU-net [

14], which extends the original four hierarchical levels of AKU-net to five (AKU-Net5). Additionally, we assessed DeepLabv3+, a widely recognized benchmark model for medical image segmentation [

40,

41]. For CNN-transformer hybrids, we included both TransUNet and HmsU-Net in our comparisons. TransUNet is among the earliest and most extensively evaluated transformer-based architectures for complex medical image segmentation tasks [

24]. HmsU-Net, currently considered a state-of-the-art model, has demonstrated superior performance across various medical image segmentation applications [

34].

To rigorously compare the performance of models, we analyzed the Dice coefficient achieved by each method using non-parametric statistical tests, which are appropriate for repeated measures across the same dataset when necessary. A Friedman test was applied to determine whether performance differences existed across all models. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

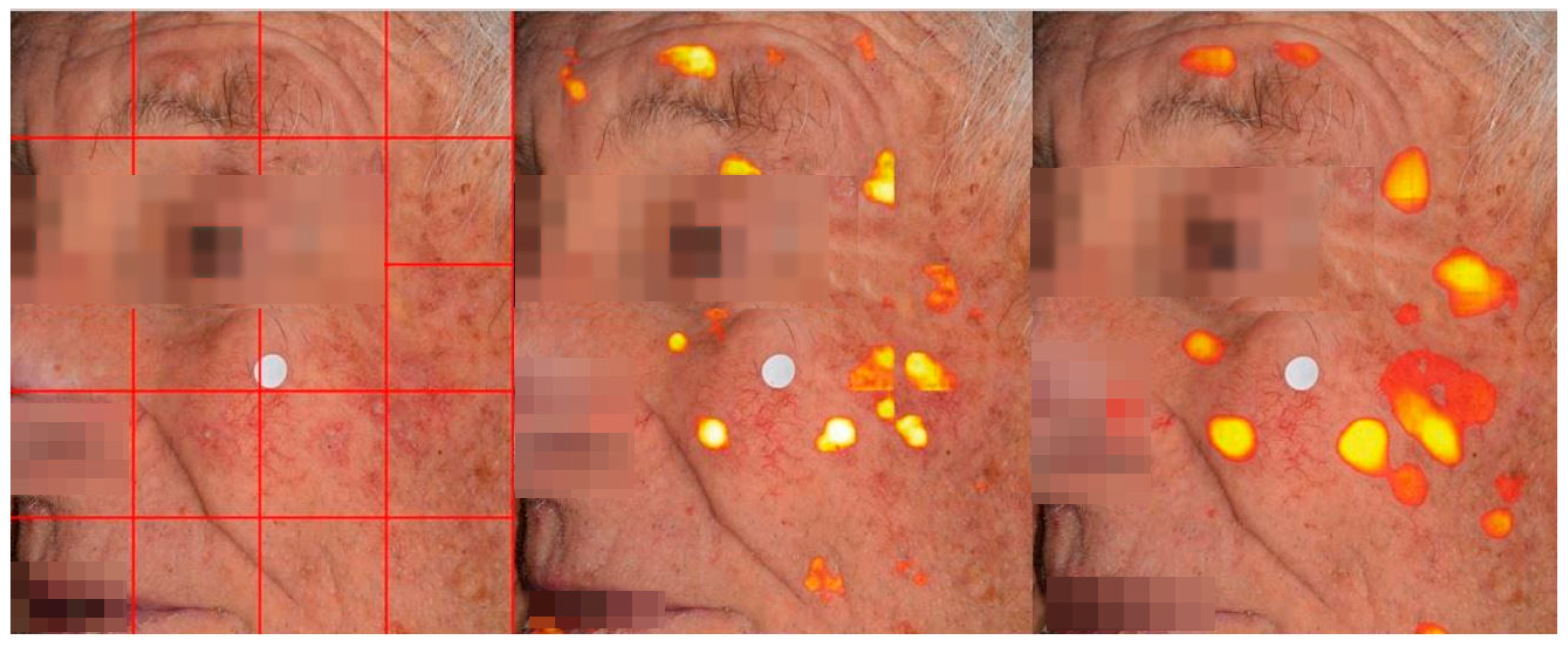

The prominent architectures at the crop level were finally evaluated for AK detection in clinical images employing a sliding window approach. This method involves breaking down a large image into smaller overlapping tiles, making predictions on these patches, and then stitching them back together to form the final prediction. This technique enables the model to focus on smaller areas of the image, which is particularly advantageous when working with high-resolution images that display a wide range of textures, color intensities, and lesion appearances. This overlapping strategy helps mitigate the boundary effects that typically arise in segmentation tasks, where regions at the edges of crops may receive less attention from the model, or even errors can occur when the patch boundary splits objects. Once the crops have been processed and predictions are made, the next challenge is to merge these predictions back into a single, coherent segmentation map. Given the overlapping nature of the crops, multiple predictions will be made for the same pixel. Without proper weighting, inconsistencies or artifacts may arise, especially in overlapping regions where predictions from different crops may vary (

Figure 3).

To ensure a seamless integration of predictions, we applied a Gaussian weighting technique. The idea is to prioritize the center of each crop when merging the predictions.

Pixels near the center of a crop tend to be more reliable because they are farther from the crop’s boundaries, where predictions might be affected by edge artifacts or the limited context available to the model.

The Gaussian weight map,

, is a 2D map that assigns higher weights to the central pixels and gradually reduces the weights towards the edges. It is defined as follows:

where

and

are the pixel coordinates relative to the center of the crop, and

controls the spread of the Gaussian function. The Gaussian map resembles a bell-shaped curve, where the central region of the crop is emphasized, and the boundary regions are down-weighted.

In our experiments, the Gaussian function’s influence extends up to of the crop’s width from its center. This ensures that the center region of each crop, which contains the most confident predictions, is weighted more heavily, while the outer pixels, which may be affected by edge effects, contribute less to the final prediction.

To reconstruct the full segmentation map from the individual crops, the predictions for each crop are multiplied by the corresponding Gaussian weight map, which emphasizes the central pixels and downweights the predictions near the edges. This weighted prediction is added to a cumulative full-size prediction map.

In addition to the full prediction map, a cumulative weight map is maintained to track the total weight assigned to each pixel during the merging process. This ensures that areas with more overlap receive appropriate normalization.

For each crop, the weighted prediction is added to the full prediction map at its corresponding position, and the Gaussian weight map is added to the cumulative weight map. After all the crops have been processed, the final full-size prediction map is normalized by dividing it by the cumulative weight map, ensuring that each pixel’s final prediction is a weighted average of all the overlapping crops that contributed to it. This process can be expressed as follows:

where

is the final prediction for pixel

,

are the prediction and the Gaussian weight map for the

crop, respectively.

The full-size segmentation map, reconstructed using the Gaussian-weighted predictions, is then thresholded to produce a binary mask.

Besides the overlapping tiles approach, we also experimented with the YOLOv8-Seg model, which processes the entire image to detect and segment AK regions. The YOLOv8-Seg model is an extension of the YOLOv8 architecture explicitly designed for instance segmentation tasks [

42,

43,

44]. While it retains the core object detection framework of YOLOv8, it adds segmentation capabilities, enabling it to predict pixel-wise masks in addition to bounding boxes and class probabilities for objects in an image. This allows the model to not only detect objects but also to separate them from the background with more precise segmentation.

To assess the segmentation performance of the proposed models, we computed the median Dice coefficient (%) for each model.

2.7. Implementation Details

The models were implemented in Python 3 using the TensorFlow framework or PyTorch (HmsU-net, TransU-net). Training was conducted on a system equipped with an NVIDIA A100 GPU and 100 GB of RAM. All models were trained for 100 epochs using the Binary Cross-Entropy loss function and the Adam optimizer, with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and a weight decay of 1e-6.

Due to computational constraints, the image crops were downscaled by a factor of 0.5, resulting in a final resolution of 256 × 256 pixels. For YOLOSegV8 and the whole-image AK segmentation task, images were instead rescaled to 1120×1120 pixels.

3. Results

3.1. AK Detection in Localized Image Regions (256X256 Crops)

To assess the segmentation performance of the proposed models, we computed the median Dice coefficient (%) for each model. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. With 15 pairwise model comparisons, the Bonferroni-adjusted threshold for significance was:

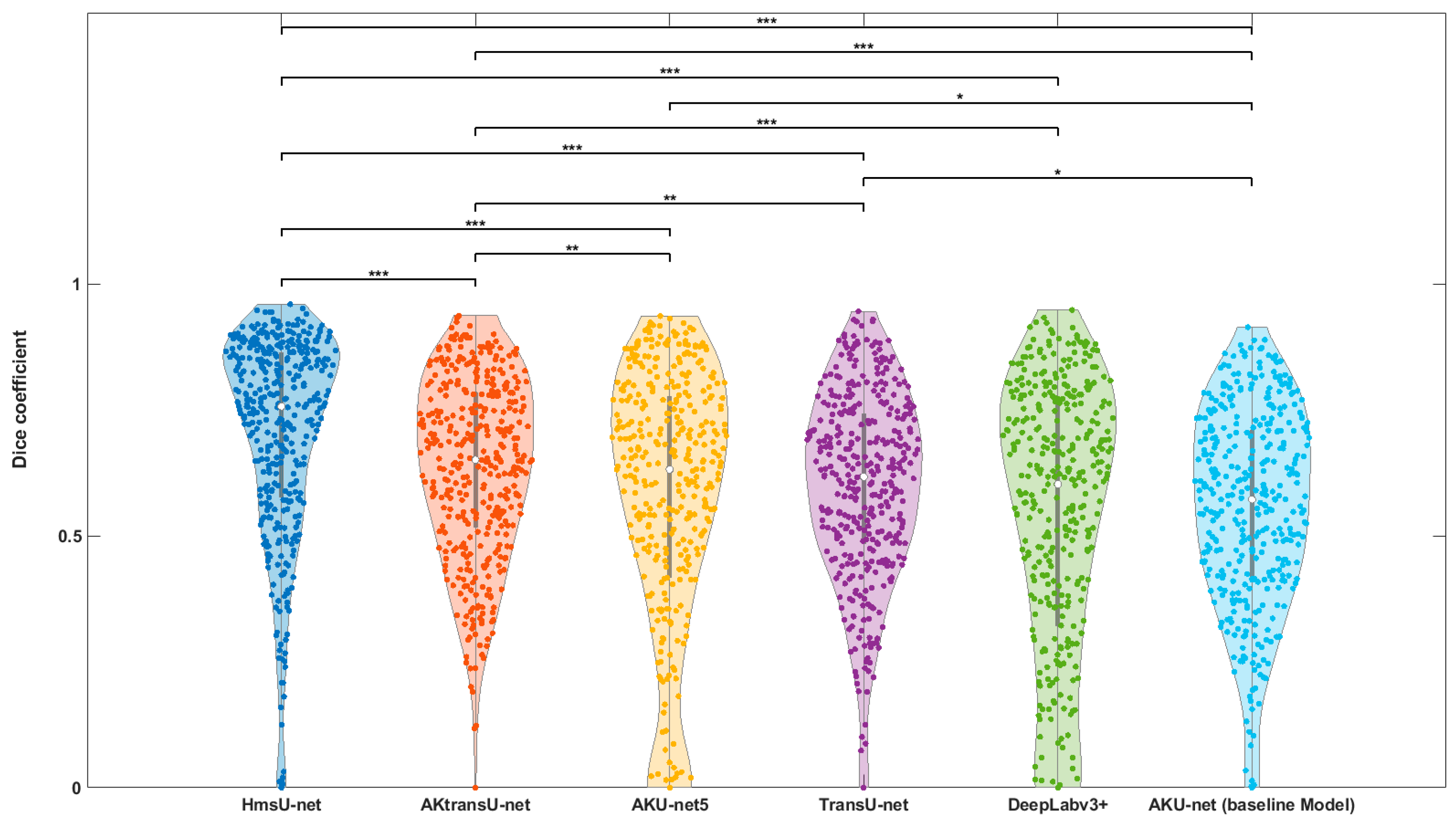

The violin plot in

Figure 4 visually summarizes these results. Horizontal lines indicate each pairwise test. Asterisks denote adjusted p-value thresholds as follows:

*: p < 0.01 (nominal, but not significant under Bonferroni)

**: p < α_corrected (statistically significant under Bonferroni)

***: p < .001 (highly significant)

Moreover,

Table 1 compiles the pairwise statistical comparisons against the baseline AKU-net model [

14].

The results indicate that HmsU-net significantly outperforms all other models in terms of both central tendency and consistency of performance. Both HmsU-net and AKtransU-net exhibited highly significant improvements (***) over the reference model, AKU-net, with HmsU-net achieving a substantial increase of more than 18 percentage points in the median Dice score.

In contrast, the improvements observed with TransU-net and AKU-net5, while nominally better than the baseline, did not withstand statistical correction for multiple comparisons and thus lacked statistical robustness. Similarly, DeepLabv3+ failed to show a statistically significant improvement over AKU-net, both in terms of raw performance (60.24% Dice) and statistical significance.

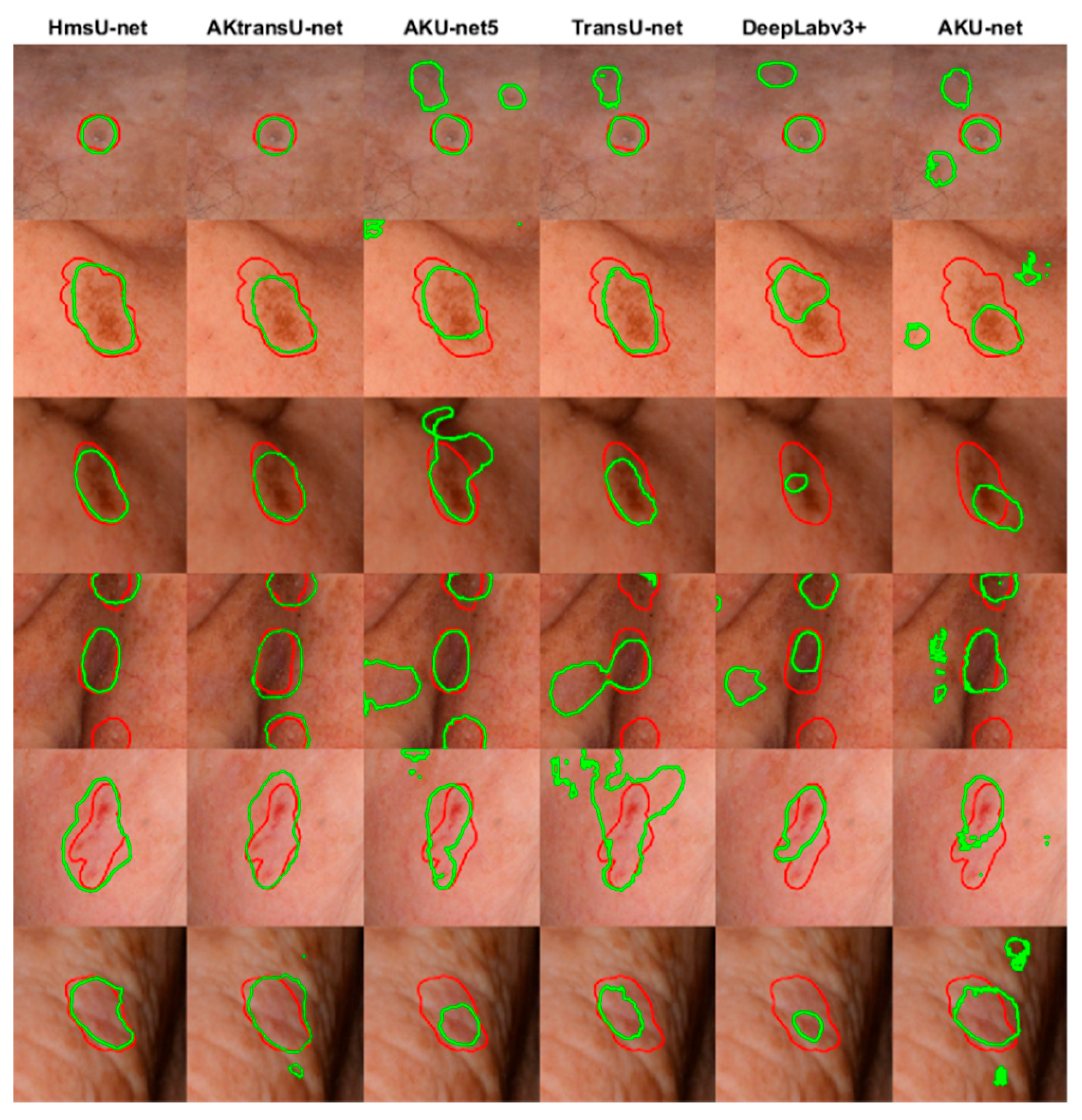

A visual demonstration of the efficiency of the evaluated models is given in

Figure 5.

3.2. Lesion Detection in Full Clinical Photographs-Whole Image Inference

To handle lesion detection in whole images, we compared three crop-based scanning strategies during semantic segmentation and evaluated their impact on segmentation performance. The first tested approach was simple block processing, involving non-overlapping image tiling into fixed-size crops (512 × 512 pixels), with predictions directly concatenated. While computationally efficient, this approach introduced artifacts at crop boundaries due to the lack of contextual information. Following, overlapping crop inference was applied using a sliding window with a stride of either 256 × 256 pixels or 128 × 128 pixels, where overlapping predictions were averaged to produce the final segmentation. Finally, we employed a Gaussian-weighted overlapping inference that used the same stride (

Table 2). The quantitative evaluation revealed a progressive improvement in segmentation accuracy and boundary continuity across methods. The Gaussian-weighted stride approach achieved the highest segmentation accuracy, with a median Dice score of 65.13%, followed by the overlapping average stride (48.11%) and simple block processing (45.74%). Pairwise comparisons using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test confirmed that both alternative strategies performed significantly worse than the Gaussian-stride baseline (p < 0.01 for both comparisons). These results demonstrate that Gaussian weighting over overlapping patches effectively improves segmentation consistency and accuracy in large, high-resolution photographs.

The wide-area segmentation performance of AKtransU-net using Gaussian-weighted stride (base model) was compared with that of HmsU-net and YOLOSegV8. The results compiled in

Table 3 show that AKtransU-net performed significantly better than HmsU-net at 256 × 256 strides (p < .05), while HmsU-net at 128 × 128 stride and YOLOSegV8 showed no significant difference from AKtransU-net (p > .05). However, a stride of 128 × 128 pixels requires approximately four times more inference computations than a stride of 256 × 256 pixels for the same image.

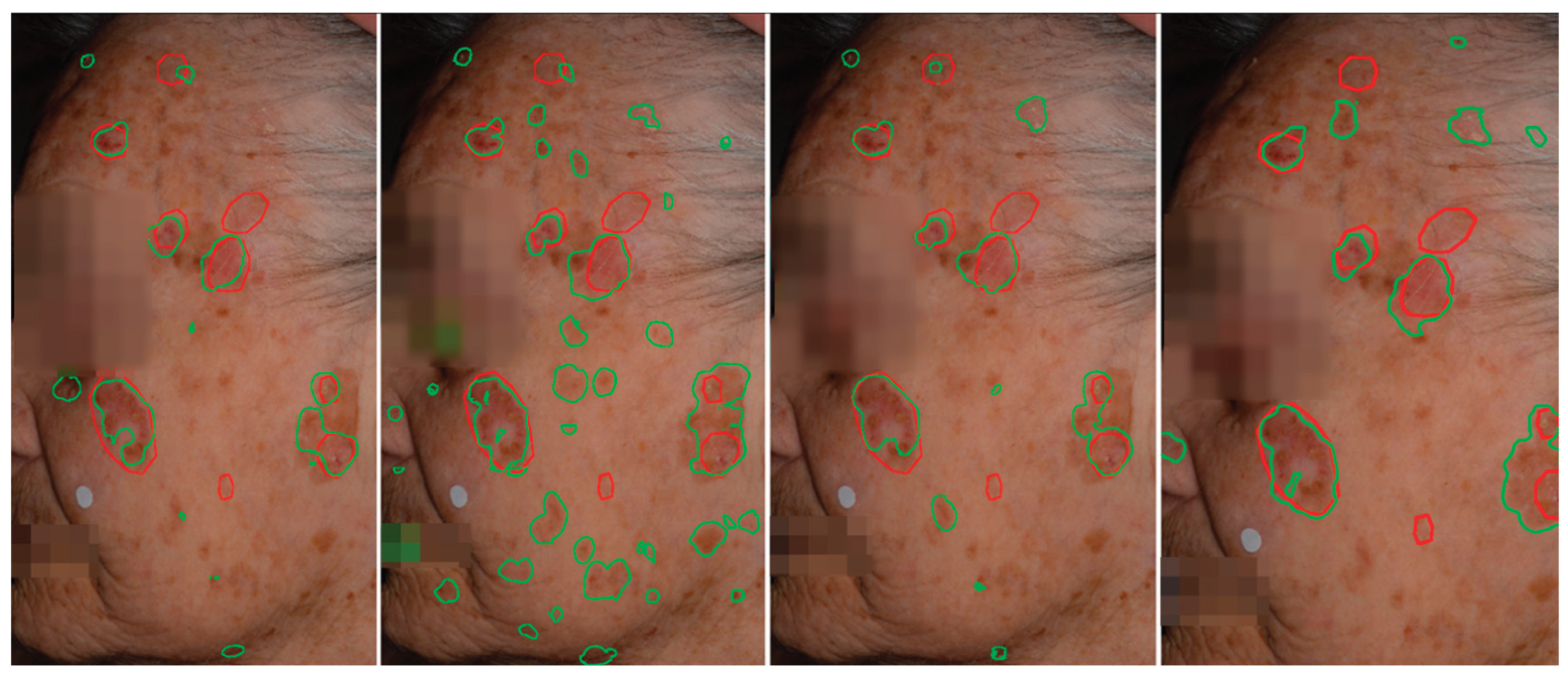

Figure 6.

Qualitative comparison of AK detection results on whole-face images. From left to right: AKtransU-net (stride, 256 × 256), HmsU-Net (256 × 256), HmsU-Net (128 × 128), and YOLOSegV8. Red contours denote the ground-truth segmentations, while green contours indicate the predictions generated by each model.

Figure 6.

Qualitative comparison of AK detection results on whole-face images. From left to right: AKtransU-net (stride, 256 × 256), HmsU-Net (256 × 256), HmsU-Net (128 × 128), and YOLOSegV8. Red contours denote the ground-truth segmentations, while green contours indicate the predictions generated by each model.

We performed an additional evaluation using targeted patch extraction to estimate the upper bound of segmentation performance for each model. Specifically, crops were extracted with their centers aligned to the annotated AK lesions. This lesion-centered extraction strategy ensured that each crop fully encompassed the lesion of interest while minimizing background variability and irrelevant tissue. As a result, the models were evaluated at whole-image detection under optimal conditions that approximate the maximum achievable segmentation performance. These results provide a helpful reference point for interpreting the practical scanning performance of each model under standard whole-image tiling conditions.

Based on lesion-centered patch extraction, the upper-bound evaluation revealed no statistically significant difference in segmentation performance between AKtransU-net and HmsU-net (

Table 4). Both models achieved comparable median Dice scores under these ideal conditions, indicating similar potential when the lesion is fully captured within the input crop. However, the results of the full-image scanning experiments demonstrated substantial performance differences between the models, with AKtransU-net consistently outperforming HmsU-net under standard tiling conditions. This divergence suggests that the scanning strategy and context variability strongly influence model behavior. Specifically, the performance of HmsU-net appeared more sensitive to changes in scanning configuration and patch overlap, while AKtransU-net maintained more consistent accuracy.

These findings underscore the crucial role of scanning methodology in real-world segmentation applications, suggesting that evaluating models solely under optimal conditions may underestimate their variability and robustness during deployment.

4. Discussion

The integration of artificial intelligence into clinical photography holds significant potential for enhancing the monitoring of skin conditions, such as actinic keratosis, and the broader context of skin field cancerization. AK lesions are often subtle, poorly defined, and diffusely distributed across chronically sun-damaged skin, making their accurate and consistent evaluation challenging, even for experienced clinicians. Given that cutaneous field cancerization progresses gradually and exhibits complex spatial patterns, there is a clear need for an advanced semantic segmentation model tailored explicitly to these clinical demands. If AK lesions can be reliably identified across complex, photodamaged skin, then a range of critical capabilities emerge, such as the consistent assessment of disease burden, the early detection of subclinical field changes, and the objective quantification of treatment response over time. Furthermore, such a system would enable standardized follow-up protocols by providing clinicians with detailed, reproducible, and spatially coherent information. In essence, high-performance AK detection is the foundation for longitudinal monitoring, therapeutic planning, and, ultimately, the advancement of precise and personalized management of field-directed therapies in dermatology.

In this work, we extend a previously introduced U-Net architecture enhanced with ConvLSTM modules by further integrating Vision Transformer encoding into the skip connections. Our goal was to target improvements where they are most critically needed: preserving spatial detail while incorporating a global contextual understanding. The inclusion of ViT modules in the skip pathways enables the model to retain fine-grained localization features while simultaneously gaining a broader semantic view of the image. This global awareness is vital for suppressing false positives, as lesion detection benefits from an enhanced understanding of the surrounding tissue context. Evidence for this is provided by the comparison with the state-of-the-art hybrid architecture HmsU-net, where our model exhibits more robust context awareness in whole image assessment (

Table 3).

To mitigate boundary artifacts and improve the smoothness and coherence of the final segmentation map, Gaussian stride processing was employed, which applies a weighted blending of overlapping tile outputs. While this method enables the processing of full-size images on limited hardware, it inherently fragments spatial information. Moreover, upper-bound evaluations (

Table 4) revealed the gap between tile-wise and truly detection accuracy of targeted lesions, indicating room for improvement.

Alternatively, YOLOv8-Seg offers a segmentation solution that processes the entire image in a single pass, preserving global context. While its performance is comparable to that of the proposed AKTransU-net (

Table 3), it appears to have reached a performance plateau in the context of AK segmentation. A key limitation is its maximum input resolution of 1120×1120 pixels, which is constrained by hardware and architectural design. This restricts its capacity for further improvement in high-resolution dermatological image analysis.

In contrast, tile-based processing offers a more flexible and scalable framework, with significant potential for further improvement through advancements in both model architecture and tile management strategies.

Finally, while the current architecture prioritizes segmentation accuracy and contextual understanding, its computational complexity remains a limitation, particularly due to the inclusion of multi-scale Transformer blocks. In future work, we aim to explore model compression techniques, lightweight Transformer variants, and efficient attention mechanisms to improve inference speed and make the model more suitable for deployment on resource-constrained devices.

5. Conclusions

The introduction of Transformers into visual tasks has significantly expanded the deep learning armamentarium, providing powerful tools for modeling long-range dependencies and capturing global context—capabilities that are particularly valuable in clinical imaging. This is especially important for challenging applications, such as skin field cancerization, where AK lesion detection depends on both fine detail and broader contextual understanding. As high-resolution imaging becomes increasingly central to dermatologic care, Transformer-driven context modeling offers a promising path forward for robust, scalable, and clinically meaningful AI-assisted monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D.,P.S.,A.L.,I.B.,and G.G. ; methodology, P.D., P.S., and A.L.; software, P.D.,C.T and P.S.; validation, P.D., P.S., and G.G.; resources, G.G.,I.B.,D.E. and A.Z.; data curation, G.G.,I.B.,D.E. and A.Z. writing—original draft preparation P.S. and D.P; writing—review and editing, P.S.,P.D.,C.T.,A.L.,G.G.and I.B.; visualization, G.G., I.B. and E.D.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Hospital of Ioannina (Approval No.: 3/17-2-2015( .17), Approval date: 17 February 2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The code is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AK |

Actinic keratosis |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| ViT |

Vision Transformer |

| ConvLSTM |

Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory |

| TransU-net |

Transformer U-net |

| HmsU-net |

Hybrid Multi-scale U-Net |

| YOLO |

You Only Look Once |

| BConvLSTM |

Bidirectional Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory |

References

- T.J. Willenbrink, E.S. Ruiz, C.M. Cornejo, C.D. Schmults, S.T. Arron, A. Jambusaria-Pahlajani, Field cancerization: Definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes, J Am Acad Dermatol 83 (2020) 709–717. [CrossRef]

- Figueras Nart, R. Cerio, T. Dirschka, B. Dréno, J.T. Lear, G. Pellacani, K. Peris, A. Ruiz de Casas, Defining the actinic keratosis field: a literature review and discussion, Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 32 (2018) 544–563. [CrossRef]

- L. Schmitz, P. Broganelli, A. Boada, Classifying Actinic Keratosis: What the Reality of Everyday Clinical Practice Shows Us, Journal of Drugs in Dermatology 21 (2022) 845–849. [CrossRef]

- J. Malvehy, A.J. Stratigos, M. Bagot, E. Stockfleth, K. Ezzedine, A. Delarue, Actinic keratosis: Current challenges and unanswered questions., J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 38 Suppl 5 (2024) 3–11. [CrossRef]

- K. Ezzedine, C. Painchault, M. Brignone, Systematic Literature Review and Network Meta-analysis of the Efficacy and Acceptability of Interventions in Actinic Keratoses., Acta Derm Venereol 101 (2021) adv00358. [CrossRef]

- E. Epstein, Quantifying actinic keratosis: Assessing the evidence, Am J Clin Dermatol 5 (2004) 141–144. [CrossRef]

- C. Baker, A. James, M. Supranowicz, L. Spelman, S. Shumack, J. Cole, W. Weightman, R. Sinclair, P. Foley, Method of Assessing Skin Cancerization and KeratosesTM (MASCKTM): development and photographic validation in multiple anatomical sites of a novel assessment tool intended for clinical evaluation of patients with extensive skin field cancerization., Clin Exp Dermatol 47 (2022) 1144–1153. [CrossRef]

- Paola. Pasquali, Photography in clinical medicine, 1st ed. 20, Cham, Switzerland : Springer, 2020.

- S.C. Hames, S. Sinnya, J.M. Tan, C. Morze, A. Sahebian, H.P. Soyer, T.W. Prow, Automated detection of actinic keratoses in clinical photographs, PLoS One 10 (2015) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- P. Spyridonos, G. Gaitanis, A. Likas, I.D. Bassukas, Automatic discrimination of actinic keratoses from clinical photographs, Comput Biol Med 88 (2017). [CrossRef]

- L. Nanni, M. Paci, G. Maguolo, S. Ghidoni, Deep learning for actinic keratosis classification, AIMS Electronics and Electrical Engineering 4 (2020) 47–56. [CrossRef]

- P. Spyridonos, G. Gaitanis, A. Likas, I.D. Bassukas, Late fusion of deep and shallow features to improve discrimination of actinic keratosis from normal skin using clinical photography, Skin Research and Technology 25 (2019) 538–543. [CrossRef]

- P. Spyridonos, G. Gaitanis, A. Likas, I.D. Bassukas, A convolutional neural network based system for detection of actinic keratosis in clinical images of cutaneous field cancerization, Biomed Signal Process Control 79 (2023) 104059. [CrossRef]

- P. Derekas, P. Spyridonos, A. Likas, A. Zampeta, G. Gaitanis, I. Bassukas, The Promise of Semantic Segmentation in Detecting Actinic Keratosis Using Clinical Photography in the Wild, Cancers 2023, Vol. 15, Page 4861 15 (2023) 4861. [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, L. Beyer, A. Kolesnikov, D. Weissenborn, X. Zhai, T. Unterthiner, M. Dehghani, M. Minderer, G. Heigold, S. Gelly, J. Uszkoreit, N. Houlsby, An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale, (2020).

- Z. Liu, Y. Lin, Y. Cao, H. Hu, Y. Wei, Z. Zhang, S. Lin, B. Guo, Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows, in: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021: pp. 9992–10002. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, E. Xie, X. Li, D.-P. Fan, K. Song, D. Liang, T. Lu, P. Luo, L. Shao, Pyramid Vision Transformer: A Versatile Backbone for Dense Prediction without Convolutions, in: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021: pp. 548–558. [CrossRef]

- B. Graham, A. El-Nouby, H. Touvron, P. Stock, A. Joulin, H. Jégou, M. Douze, LeViT: a Vision Transformer in ConvNet’s Clothing for Faster Inference, in: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021: pp. 12239–12249. [CrossRef]

- N. Siddique, S. Paheding, C.P. Elkin, V. Devabhaktuni, U-net and its variants for medical image segmentation: A review of theory and applications, IEEE Access (2021). [CrossRef]

- R. Azad, E.K. Aghdam, A. Rauland, Y. Jia, A.H. Avval, A. Bozorgpour, S. Karimijafarbigloo, J.P. Cohen, E. Adeli, D. Merhof, Medical Image Segmentation Review: The Success of U-Net, IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell (2024). [CrossRef]

- Q. Pu, Z. Xi, S. Yin, Z. Zhao, L. Zhao, Advantages of transformer and its application for medical image segmentation: a survey, Biomed Eng Online 23 (2024) 1–22. [CrossRef]

- R.F. Khan, B.D. Lee, M.S. Lee, Transformers in medical image segmentation: a narrative review, Quant Imaging Med Surg 13 (2023) 8747–8767. [CrossRef]

- H. Xiao, L. Li, Q. Liu, X. Zhu, Q. Zhang, Transformers in medical image segmentation: A review, Biomed Signal Process Control 84 (2023) 104791. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen, Y. Lu, Q. Yu, X. Luo, E. Adeli, Y. Wang, L. Lu, A.L. Yuille, Y. Zhou, TransUNet: Transformers Make Strong Encoders for Medical Image Segmentation, (2021). Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2102.04306 (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- J. Chen, J. Mei, X. Li, Y. Lu, Q. Yu, Q. Wei, X. Luo, Y. Xie, E. Adeli, Y. Wang, M.P. Lungren, S. Zhang, L. Xing, L. Lu, A. Yuille, Y. Zhou, TransUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture design for medical image segmentation through the lens of transformers, Med Image Anal 97 (2024) 103280. [CrossRef]

- S. Atek, I. Mehidi, D. Jabri, D.E.C. Belkhiat, SwinT-Unet: Hybrid architecture for Medical Image Segmentation Based on Swin transformer block and Dual-Scale Information, in: 2022 7th International Conference on Image and Signal Processing and Their Applications (ISPA), 2022: pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- A. Lin, B. Chen, J. Xu, Z. Zhang, G. Lu, D. Zhang, DS-TransUNet: Dual Swin Transformer U-Net for Medical Image Segmentation, IEEE Trans Instrum Meas 71 (2022) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, P. Cao, J. Wang, O. Zaïane, UCTransNet: Rethinking the Skip Connections in U-Net from a Channel-Wise Perspective with Transformer, Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 36 (2022) 2441–2449. [CrossRef]

- B. Fu, Y. Peng, J. He, C. Tian, X. Sun, R. Wang, HmsU-Net: A hybrid multi-scale U-net based on a CNN and transformer for medical image segmentation, Comput Biol Med 170 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, P. Fischer, T. Brox, U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation, Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 9351 (2015) 234–241. [CrossRef]

- N. Ibtehaz, M.S. Rahman, MultiResUNet : Rethinking the U-Net architecture for multimodal biomedical image segmentation, Neural Networks 121 (2020) 74–87. [CrossRef]

- S. Chen, Y. Zou, P.X. Liu, IBA-U-Net: Attentive BConvLSTM U-Net with Redesigned Inception for medical image segmentation, Comput Biol Med 135 (2021) 104551. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, S. Yang, Y. Jiang, Y. Chen, F. Sun, FAFS-UNet: Redesigning skip connections in UNet with feature aggregation and feature selection, Comput Biol Med 170 (2024) 108009. [CrossRef]

- B. Fu, Y. Peng, J. He, C. Tian, X. Sun, R. Wang, HmsU-Net: A hybrid multi-scale U-net based on a CNN and transformer for medical image segmentation, Comput Biol Med 170 (2024) 108013. [CrossRef]

- W. Byeon, T.M. Breuel, F. Raue, M. Liwicki, Scene labeling with LSTM recurrent neural networks, in: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2015: pp. 3547–3555. [CrossRef]

- X. Shi, Z. Chen, H. Wang, D.Y. Yeung, W.K. Wong, W.C. Woo, Convolutional LSTM Network: A Machine Learning Approach for Precipitation Nowcasting, Adv Neural Inf Process Syst 2015-Janua (2015) 802–810. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.04214v2 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- R. Azad, M. Asadi-Aghbolaghi, M. Fathy, S. Escalera, Bi-Directional ConvLSTM U-Net with Densley Connected Convolutions, Proceedings - 2019 International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop, ICCVW 2019 (2019) 406–415. [CrossRef]

- X. Jiang, J. Jiang, B. Wang, J. Yu, J. Wang, SEACU-Net: Attentive ConvLSTM U-Net with squeeze-and-excitation layer for skin lesion segmentation, Comput Methods Programs Biomed 225 (2022) 107076. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Muccini, N. Kollias, S.B. Phillips, R.R. Anderson, A.J. Sober, M.J. Stiller, L.A. Drake, Polarized light photography in the evaluation of photoaging, J Am Acad Dermatol 33 (1995) 765–769. [CrossRef]

- L.C. Chen, Y. Zhu, G. Papandreou, F. Schroff, H. Adam, Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation, Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 11211 LNCS (2018) 833–851. [CrossRef]

- Prokopiou, P. Spyridonos, Highlighting the Advanced Capabilities and the Computational Efficiency of DeepLabV3+ in Medical Image Segmentation: An Ablation Study, BioMedInformatics 2025, Vol. 5, Page 10 5 (2025) 10. [CrossRef]

- R. Varghese, M. Sambath, YOLOv8: A Novel Object Detection Algorithm with Enhanced Performance and Robustness, 2024 International Conference on Advances in Data Engineering and Intelligent Computing Systems (ADICS) (2024). [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, Y. Zou, Y. Tan, C. Zhou, YOLOv8-seg-CP: a lightweight instance segmentation algorithm for chip pad based on improved YOLOv8-seg model, Sci Rep 14 (2024) 27716. [CrossRef]

- Explore Ultralytics YOLOv8 - Ultralytics YOLO Docs, (n.d.). Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov8/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).