1. Introduction

In many real-world scenarios, relationships between entities can be modeled as bipartite networks, where edges only exist between two disjoint sets of nodes, such as users and items [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Predicting new links in these networks, often framed as recommendation, is a crucial task for improving user experience and system efficiency [

5]. Collaborative filtering (CF) is one of the most widely used approaches in recommendation systems [

6,

7], with memory-based and model-based methods as two major branches [

8]. While memory-based CF methods are simple and highly interpretable, they have long been considered less competitive in performance compared to more complex model-based methods.

However, recent advance, Sapling Similarity Collaborative Filtering (SSCF), has shown that memory-based approaches still hold significant promise [

9]. SSCF leverages a new similarity measure and achieves state-of-the-art performance on benchmark datasets, outperforming all the other models. This suggests that the full potential of memory-based methods has yet to be realized, particularly if better ways of capturing structural information in networks can be found.

Most traditional memory-based CF methods rely on basic node similarity measures, often limited to shared neighbors, which overlook deeper topological insights. In contrast, network science offers rich theoretical foundations for understanding link formation. The Cannistraci-Hebb (CH) theory [

10,

11], inspired by brain connectivity, emphasizes the importance of local community structures [

12] rather than just node-level features. CH-based methods are network automata rules that have shown strong performance in various link prediction tasks and have even been used to sparsify neural networks while preserving accuracy [

13,

14].

Motivated by the theoretical and empirical strength of CH theory, we propose Network Shape Automata (NSA), a novel memory-based collaborative filtering method that fully leverages network topology for recommendation. NSA adheres to the classical architecture of memory-based CF, yet redefines similarity computation based on local topological features derived from CH theory. We evaluate NSA on various benchmark datasets from both the recommendation and link prediction domains. Results demonstrate that NSA consistently achieves competitive, and in some cases superior, performance compared to state-of-the-art models, while preserving the simplicity and transparency of memory-based systems. Our work highlights the overlooked potential of structural information in network-based recommendations and presents NSA as a bridge between interpretable design and high recommendation accuracy.

Here, we present our main contribution in this work as follows:

Introduction of Network Shape Automata (NSA): We propose NSA, a novel memory-based collaborative filtering method that, for the first time, integrates CH theory into similarity computation by leveraging local topological features of the network.

Comprehensive Hyperparameter Learning and Evaluation Across Domains: NSA was evaluated on 13 datasets across both recommendation and link prediction domains, consistently demonstrating stable and often superior performance compared to state-of-the-art models. Rather than relying on a single perspective, we innovatively examined both sides of the bipartite network structure. By incorporating a broader range of datasets and application scenarios, as detailed in

Table 1, our evaluation provides a more comprehensive and rigorous assessment of model performance. Notably, we conducted extensive and systematic hyperparameter learning, involving over 105300 model assessments. This ensured unbiased and automated hyperparameter selection, enabling fair and reproducible comparisons across all evaluated methods.

Revealing the Power of Structural Information: This work underscores the often-overlooked potential of structural information in recommendation tasks and shows how NSA effectively bridges the gap between interpretability and accuracy. NSA demonstrates that tools from network science can be effectively used to uncover intrinsic patterns in user-item interactions, providing a principled way to model real-world information. By exploiting network structural properties, NSA can capture meaningful relationships even when user-item interactions are extremely limited.

Unified Perspective on Recommendation and Link Prediction: This work is among the most recent efforts to systematically bridge the tasks of link prediction and recommendation through the lens of network science. By viewing recommendation as a dynamic network evolution process, we provide a unified framework that captures the underlying mechanisms of real-world information systems.

2. Related Work

2.1. Bipartite Network Projection

Bipartite networks consist of two disjoint sets of nodes with edges only between nodes of different sets [

21], and are commonly used to represent real-world relationships, for example, users and items in recommendation systems. In such applications, the two sets typically correspond to users and items, with edges representing interactions such as purchases, views, or ratings. Depending on the nature of these interactions, bipartite networks can be divided into two categories: non-unary rating, where links carry explicit preference scores; and unary rating, where links only indicate the presence or absence of interaction, without expressing degrees of preference [

6]. This paper focuses on the unary rating scenario, where collaborative filtering methods are widely adopted.

Bipartite network projection, or one-mode projection, transforms a bipartite network into two monopartite ones by connecting nodes of the same type if they share common neighbors [

21]. This process captures similarity within a single node set and serves as a compressed representation of the original bipartite structure. However, such compression inevitably loses some relational detail, making the choice of edge weighting in the projected network critical for preserving meaningful information [

22,

23]. Different weighting methods emphasize different aspects of the original network and are chosen based on the analytical goals of the projection.

2.2. Collaborative Filtering

Recommendation systems are essential tools for delivering personalized content by predicting user preferences based on historical interactions. To address this task, various approaches have been proposed, including content-based approach [

24], collaborative filtering [

25], and hybrid models that combine multiple strategies. Among them, collaborative filtering (CF) stands out for its effectiveness and broad adoption, relying on user behavior shared patterns rather than item attributes.

Collaborative filtering can be further classified into memory-based and model-based methods [

8,

26].

Memory-based approaches predict user preferences by computing similarities between users or items, with various similarity measures developed to improve recommendation accuracy. The structure of different memory-based methods is largely the same, with the choice of similarity measure being the key differentiator. Widely used similarity measures in memory-based approaches include Common Neighbors [

27], Jaccard [

28], Resource Allocation Index [

29], Cosine Similarity, and Pearson Correlation Coefficient [

30]. Most of these measures estimate similarity based on the common neighbors of two nodes. Notably, the recently proposed Sapling Similarity Collaborative Filtering (SSCF) introduces a probabilistic perspective that enables negative similarity modeling, offering improved performance [

9].

Model-based approaches, in contrast, learn predictive models from user-item interactions using machine learning techniques. Recent advancements focus on neural network methods, particularly Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), which capture high-order user-item connectivity [

31]. These include NGCF, an early and influential method that introduced graph-based message passing for collaborative filtering [

15]; LightGCN, which simplified this framework while achieving stronger performance [

16]; SimpleX, which further optimized the model design for efficiency [

18]; UltraGCN, which avoided explicit graph convolution by modeling global interactions [

17]; LT-OCF, which models user and item embedding evolution over continuous time using neural ODEs with learnable interaction timestamps, thereby effectively capturing temporal dynamics [

19]; and BSPM, which uses a blurring-sharpening process to perturb and refine interactions, and is regarded as a diffusion-based approach rather than a conventional neural network method [

20].

2.3. Cannistraci-Hebb Theory

CH rules are network automata for estimating the likelihood of a non-observed link to appear in the network. These rules are classified as network automata because they utilize only local information to infer the score of a link in the network without need of pre-training of the rule. Note that CH rules are predictive network automata that differ from generative network automata which are rules created to generate artificial networks [

32,

33,

34]. The concept of

network automata was originally introduced by Wolfram [

35] and later formally defined by Smith et al. [

36] as a general framework for modeling the evolution of network topology. Given an unweighted and undirected adjacency matrix

at time

t, in a network automaton the states of links evolve over time according to a rule that depends only on local topological properties computable from a portion of the adjacency matrix

:

Network shape intelligence is an emerging paradigm that tries to perform link prediction by exploiting the intrinsic topological structure of real-world networks, without relying on training or external data. The core idea is to treat the network itself as both input and source of knowledge, enabling unsupervised predictions based solely on local connectivity patterns [

13]. A representative advancement in this area is the Cannistraci-Hebb (CH) theory, which extends Hebbian learning, originally proposed in neuroscience, to the domain of complex network analysis [

37].

Hebbian learning posits that coactivated neurons tend to form connections and was generalized into the Local-Community Paradigm (LCP) [

12]. LCP assumes that new links are more likely to form within local communities, where nodes are densely connected and related. CH theory formalizes this through two structural tendencies: maximization of internal local community links (iLCL) and minimization of external local community links (eLCL) [

10,

11]. Based on these principles, different versions of CH indexes have been proposed that focus different properties of networks (CHn). In addition, multi-scale variants (Ln) are introduced to account for different community sizes, based on the path length between node pairs.

CH-based link predictors have shown strong empirical performance across different domains. In particular, Cannistraci et al. demonstrated that a CH-inspired predictor outperformed AlphaFold in protein-protein interaction prediction [

13]. Furthermore, neural networks with CH-based sparse connectivity, retaining only 1% of original links, achieved comparable or better results than fully connected models [

14], suggesting the potential of biologically-inspired, ultra-sparse architectures.

These insights underscore the predictive power of topology alone and provide theoretical support for applying CH theory to recommendation systems, especially in settings where data sparsity or lack of supervision poses significant challenges.

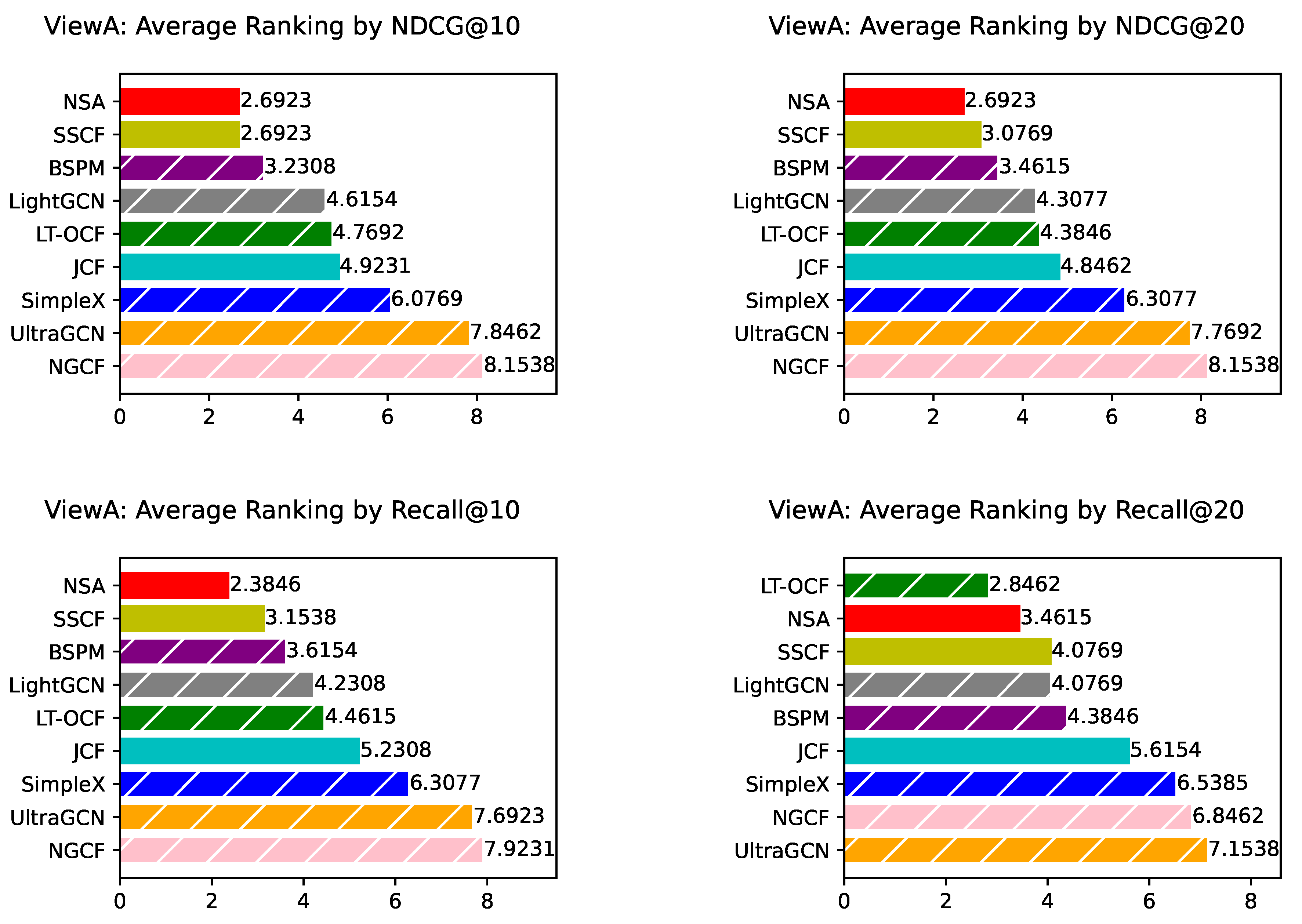

3. Network Shape Automata

To formally present our approach, we begin by introducing the fundamental definitions. Consider a bipartite network representing the recommendation system, where the set of user nodes is denoted by U and the set of item nodes by . The cardinalities and indicate the total number of users and items, respectively. The network structure is encoded by an adjacency matrix , where each entry if user u is connected to item , and 0 otherwise. As we focus on unary rating scenarios, the network is assumed to be unweighted. The degree of a user node u is defined as , while the degree of an item node is denoted by . The set of common neighbors between users i and j is denoted , and similarly, the common neighbors between items and are denoted .

Then, we introduce Network Shape Automata (NSA) which can be treated as memory-based collaborative filtering in a topological way. Specifically, NSA follows the steps described in the sub

Section 3.1 to

Section 3.4 below, illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.1. CH Scoring

As the core component of NSA, we calculate the similarity between different pairs of nodes based on CH theory.

CH index

Inspired by CH theory [

10], the basis of the similarity is CH indexes, including CH3-L2 [

11] and CH3.1-L2. CH3-L2 is the version based on local community for path of length 2 and takes into account only the minimization of external links, of which the formula is

The formula of CH3.1-L2 is

For clarification, i and j represent two nodes of the same kind in the bipartite network, denotes the set of nodes on the path of length 2 between nodes i and j (specifically, in the case of a path of length 2, this can be understood as the set of common neighbors between i and j). represents the number of external community links for node k (i.e., the number of neighbors of node k that are not in the set and are not i or j). represents the number of internal community links for node k (i.e., the number of neighbors of node k that are also in the set).

Denominator

Inspired by the weighting methods used in bipartite network projection, we introduce a scaling factor as the denominator of the CH index to reduce the weight of links connecting two nodes with many neighbors. We adopt three options as denominator with different topological meaning, including:

sum of degree: the sum of the degrees of the two seed nodes

union of neighbors: the total number of neighbor nodes of the two seed nodes

sum of nlcl: the number of non local community links (nlcl) of the two seed nodes (i.e., the number of neighbors of the two seed nodes that are not in the

set)

Exponent

To further control the impact of the scaling factor, we introduce a new exponent variable for the denominator. As the name suggests, the exponent serves as the power of the denominator base that ranges from 1 to 2.

The similarity between a pair of nodes can be represented as

3.2. Monopartite Projection

The CH-scoring process is based on the local community defined by paths of length two. This naturally gives rise to two projected monopartite networks, one for users and one for items, where a link exists between two nodes of the same type only if they share at least one common neighbor. We employed bipartite network projection to transform both the topology and the assigned weights into two separate monopartite networks.

3.3. Bipartite Scoring

Based on two monopartite networks respectively, we can weight all the non-existing links inside the original bipartite network based on simple aggregation. Here, we adopted two options for the aggregation:

3.4. Mixing Item and User Scores

Based on the item-based score and user-based score we draw from two monopartite networks, take the weighted average of item-based score and user-based score controlled by parameter

as the weight of item-based score, which is ranged from 0 to 1 step by 0.1. The final recommendation score can be represented as:

4. Experiments

We’ve conducted quite a lot of experiments to prove that our method is of superiority compared to both traditional memory-based methods and the advanced model-based methods.

4.1. Baselines

The baselines adopted in our study span from traditional memory-based approaches to state-of-the-art model-based methods.

Memory-based methods follow a standard pipeline and the key distinction among various memory-based approaches lies in the choice of similarity metric. Our implementation of memory-based collaborative filtering strictly follows the framework introduced in previous work [

9]. We selected two representative similarity measures to construct memory-based baselines: the state-of-the-art Sapling Similarity and the widely-used Jaccard Similarity, with the memory-based method built upon called SSCF and JCF respectively. We select a series of representative and state-of-the-art model-based methods as baselines, including NGCF [

15], LightGCN [

18], SimpleX [

18], UltraGCN [

17], LT-OCF [

19] and BSPM [

20] . For BSPM, to be specific, we utilized the variant BSPM-EM which offers better performance [

20].

4.2. Datasets

We employed 13 datasets from different filed ranging from drug-target network in biological field to typical recommendation datasets in social system [

9,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. The statistics of all the datasets are listed in

Appendix B, where we reported the source, number and type of nodes and the density.

It is important to note that, for some datasets, there is no explicit distinction between users and items. For example, in drug-target networks, recommendations can be made from either the drug perspective or the target perspective, both of which are meaningful in real-world applications. Therefore, we conducted experiments from both perspectives, treating different sets of nodes as the "user" side.

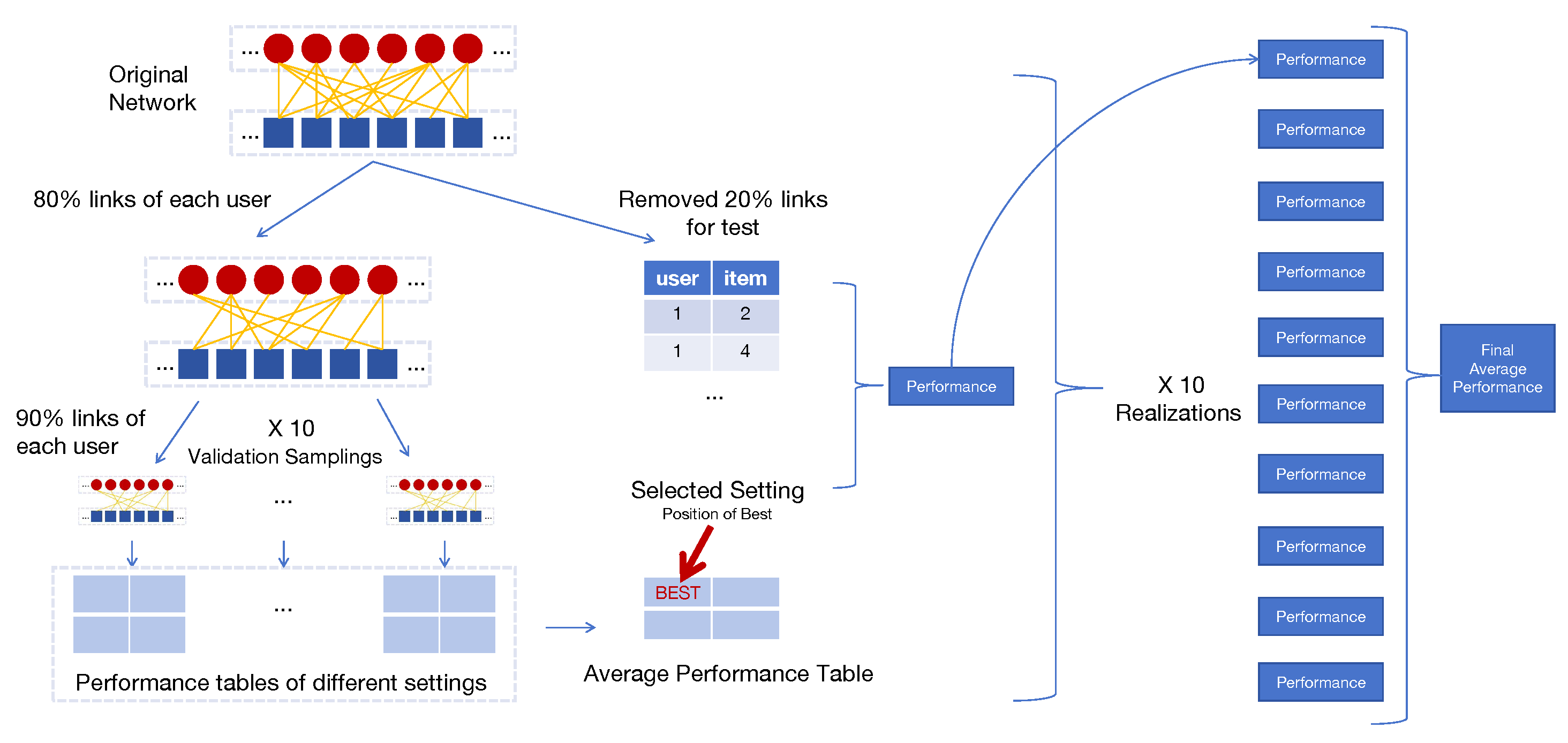

4.3. Hyperparameter Learning and Evaluation

In this section, we introduce the way we split the datasets as train and test set, the metric we used for evaluation, and the evaluation process. For clarity, the entire procedure is also illustrated in a figure provided in

Appendix E.

Metrics

To better evaluate the performance of models, we utilized widely used metrics in recommendation system field: Recall@10, Recall@20, NDCG@10, NDCG@20.

Train-Test Split

We follow the widely used way to split each dataset to train set and test set. For all the datasets, the train set retains 80% links for each user randomly. The rest links would become test set which is used to evaluate the performance of models. We repeat the split several times which can be called as different realizations in case that the randomness of segmentation influences the evaluation of performance.

Hyperparameter Learning

We adopted multiple

validation samplings to learn the most appropriate hyperparameter setting for each realization automatically. To be specific, we’ll further split the train set to two parts. 10% links of each user would be randomly removed to verify the performance of different hyperparameter settings. Also, to avoid randomness, we repeat this procedure 10 times and the hyperparameter setting with highest average performance would be the one used for test. It needs attention that, when evaluated by different metrics, the best hyperparameter setting can be different. To ensure the fairness of comparison, we conducted the same hyperparameter choosing strategy on all baseline methods mentioned above strictly and carefully. The concrete hyperparameter setting under search for each baseline method are reported in

Appendix D.

Evaluation Process

Each model would give a ranking of all the non-existing links for all the users based on the existing links in the train set, then the links with highest ranking would become the result of prediction. For each user, we would compute metrics Recall@20, Recall@10, NDCG@20 and NDCG@10. For each metric, the final performance is the average among all the users. Results reported are the average across all realizations.

5. Results

In this section, we present a comprehensive summary, comparison, and analysis of the performance of NSA and selected baseline methods across 13 datasets. Specifically, experiments were conducted using 10 realizations under the default ViewA, and 5 realizations under the alternative ViewB. For the latter, we selected the top-performing method from each category based on the results in ViewA: NSA for memory-based methods; LT-OCF for neural network-based methods, which are considered a subset of model-based approaches; and BSPM for diffusion-based methods, which has shown competitive performance in prior work [

9]. Due to space limitations, additional results are provided in the Appendix.

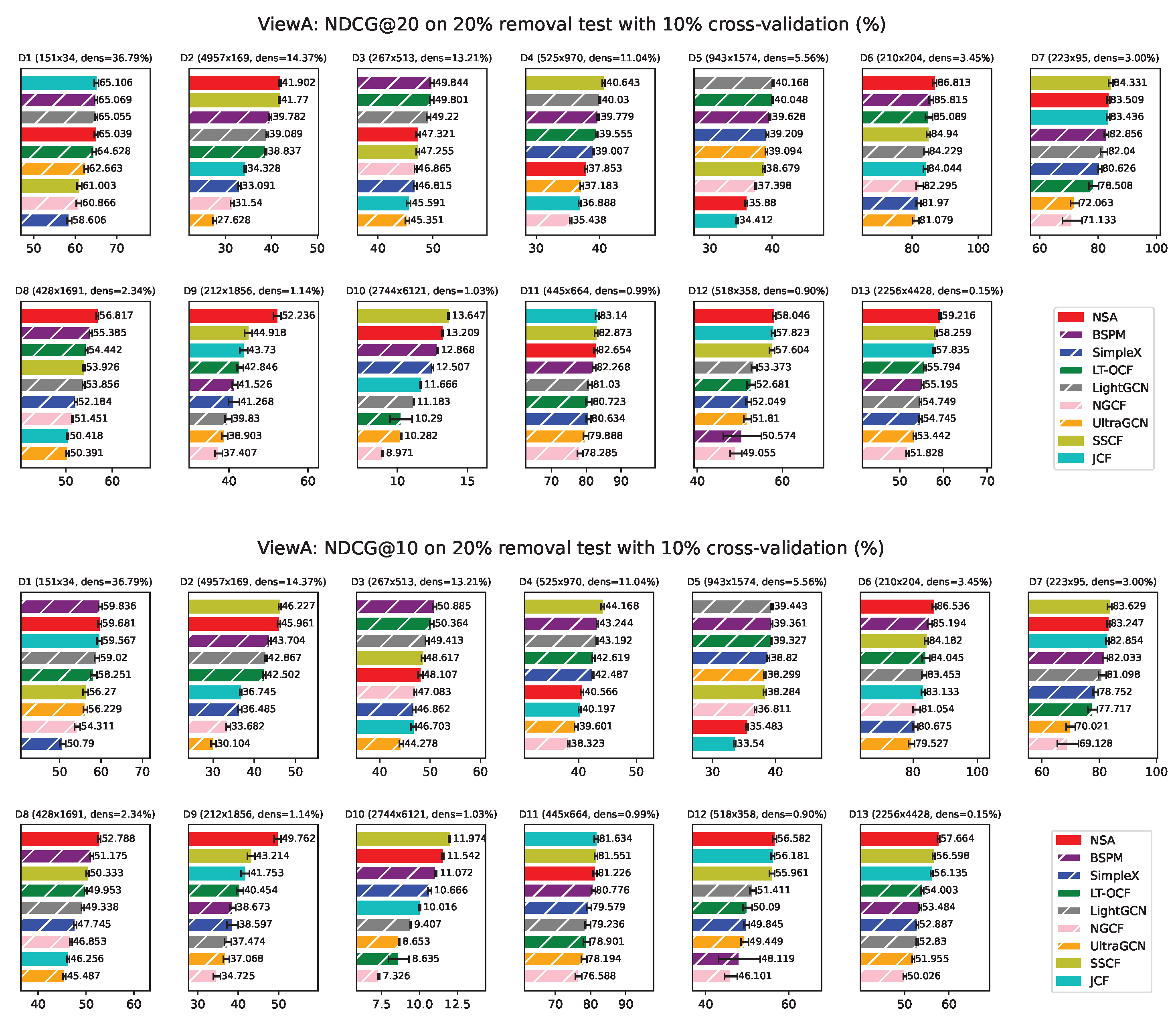

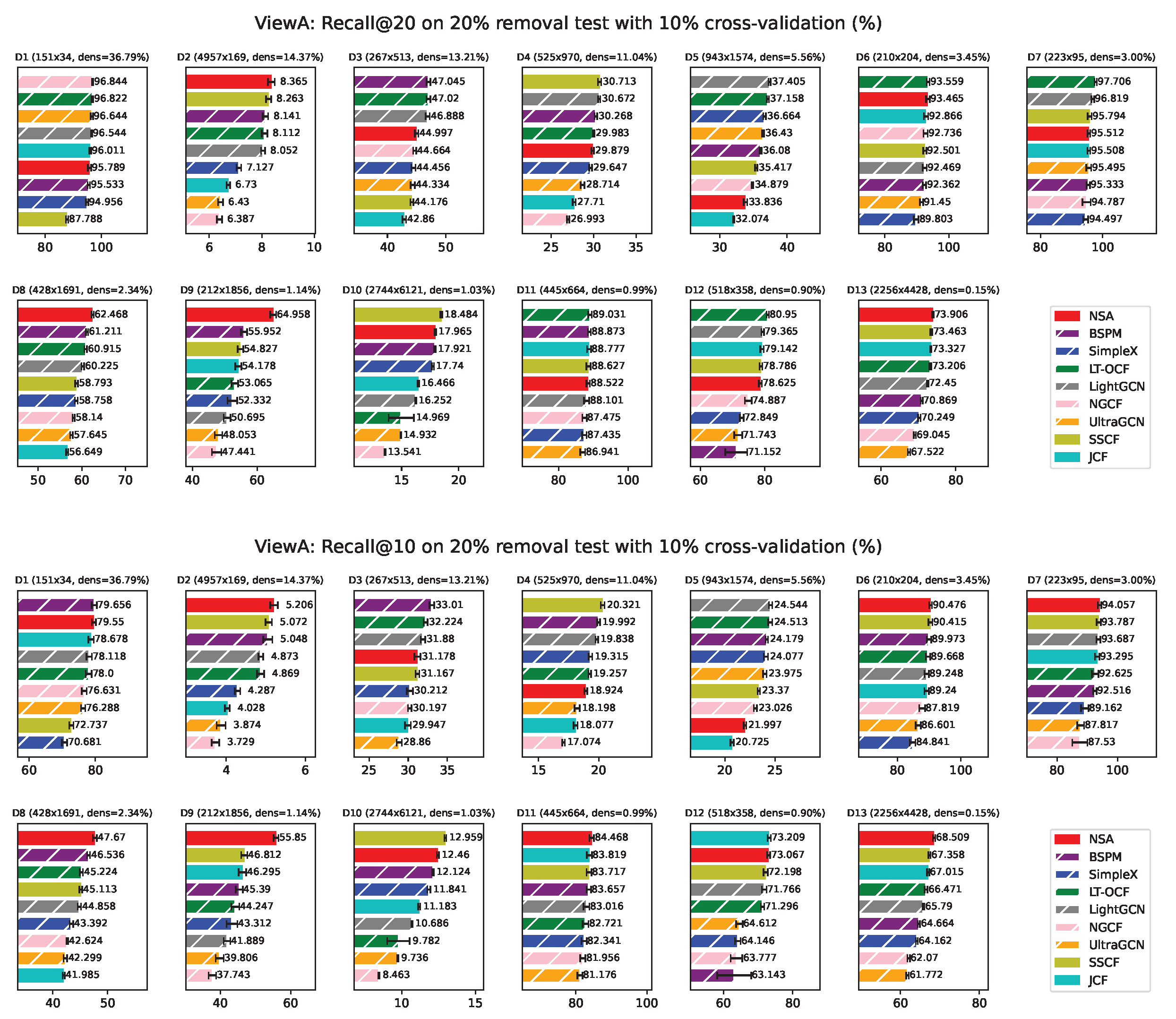

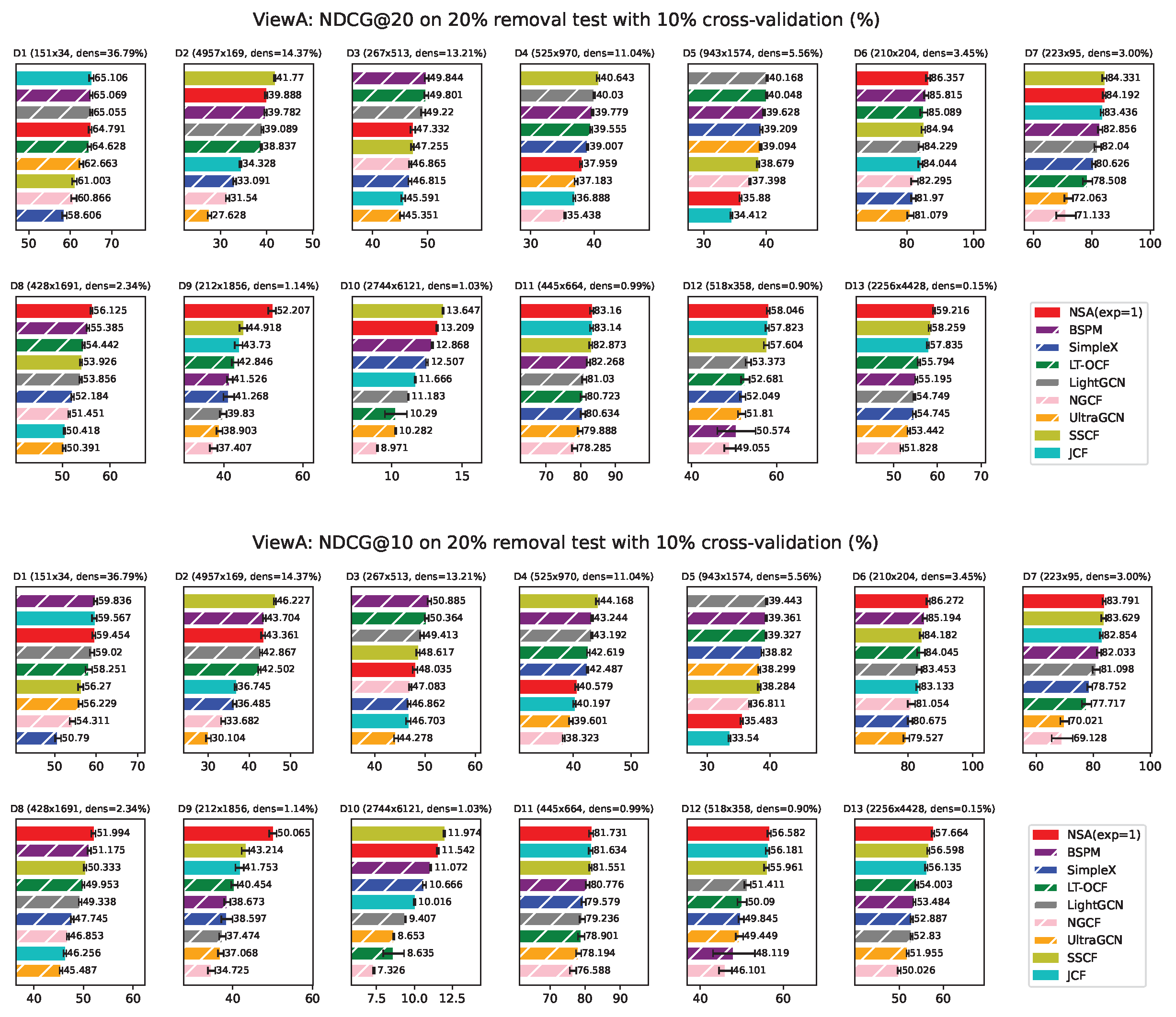

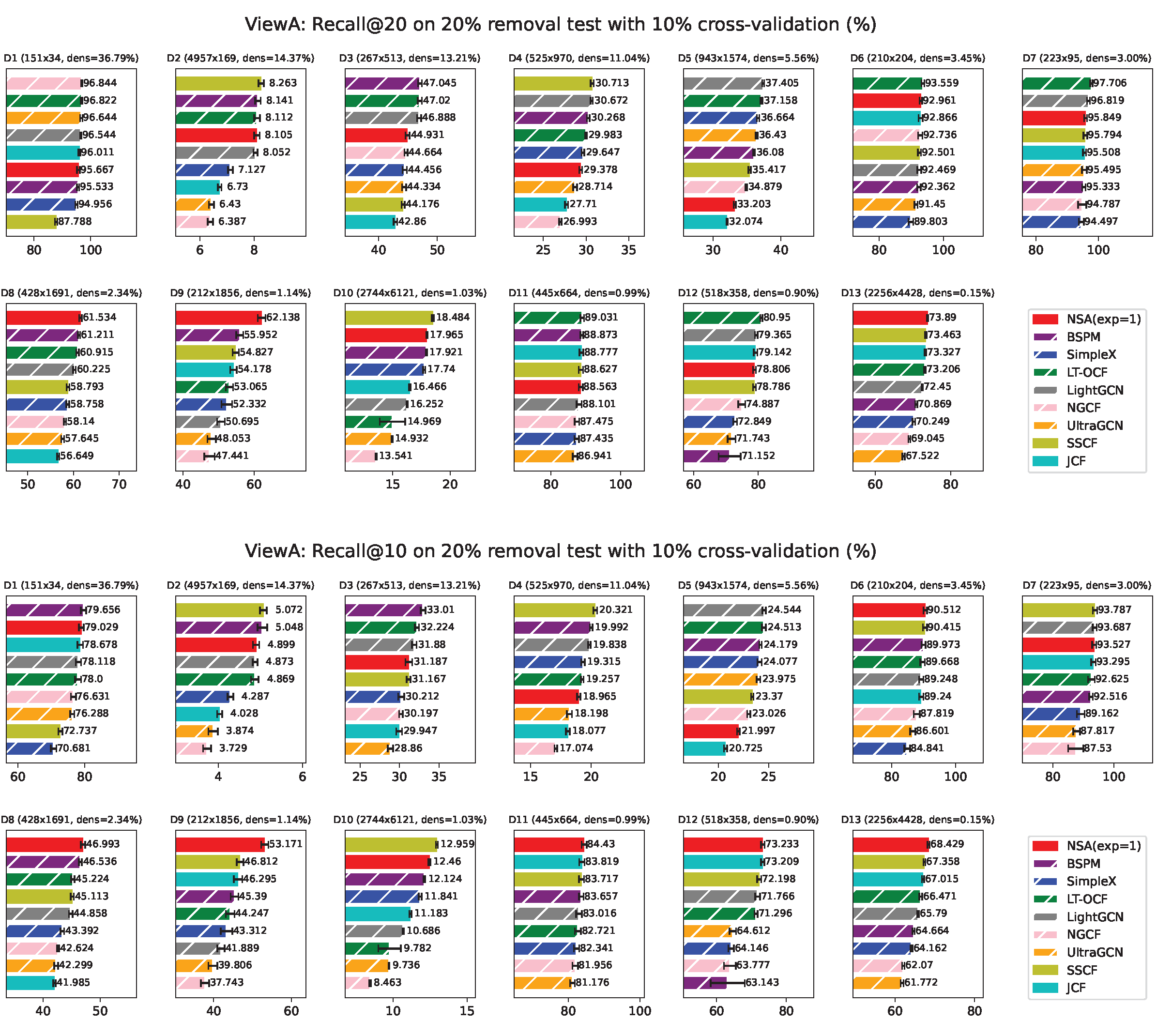

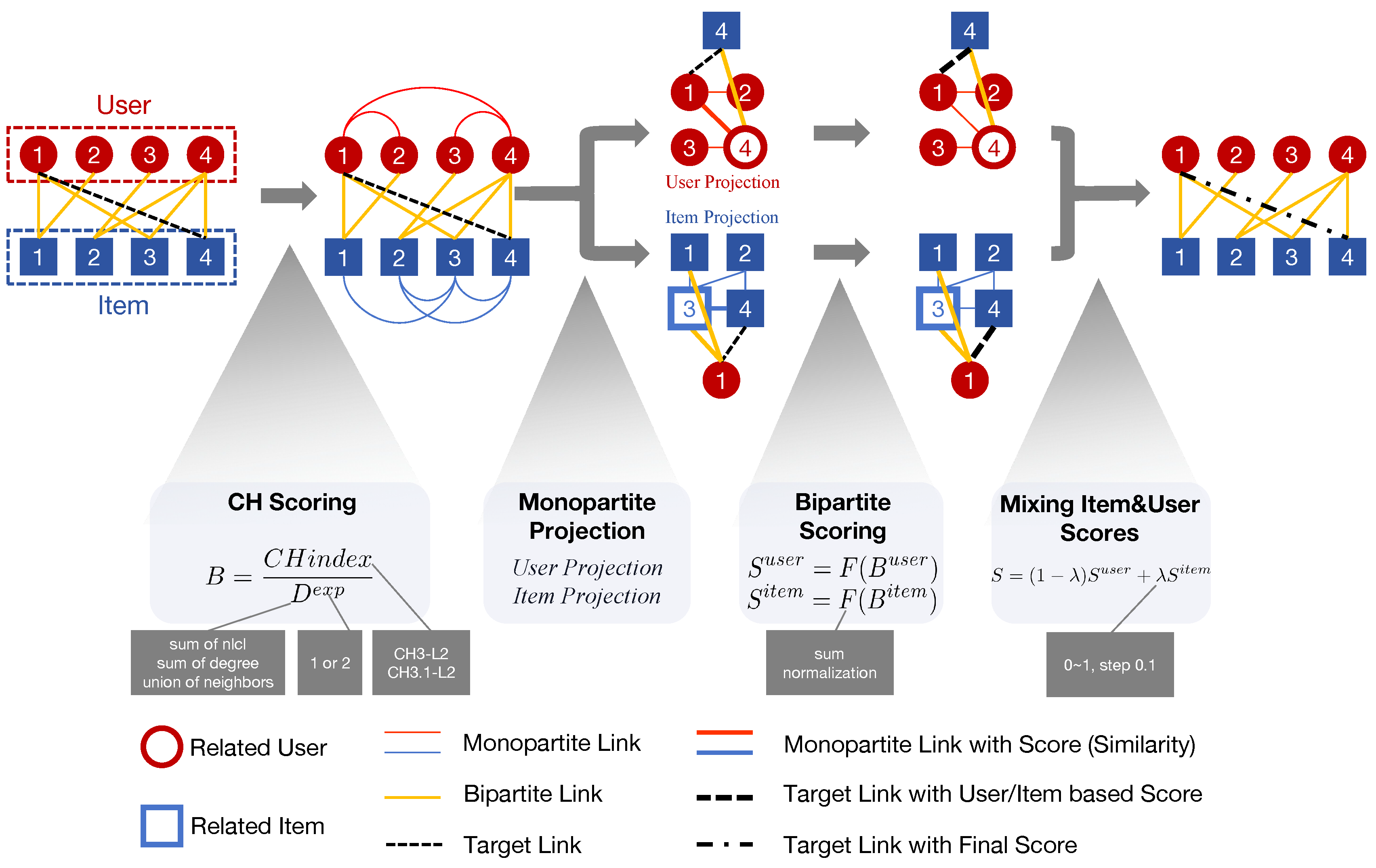

ViewA Results

We present results for all methods based on individual network from ViewA in

Appendix F, where NSA consistently outperforming most methods on the majority of datasets compared to a comprehensive set of baselines. To provide a comprehensive comparison, we further compute the average ranking of each method across all datasets. As shown in

Figure 2 , NSA consistently ranks first or second across various metrics, highlighting its overall superiority. This consistent top-tier performance not only reflects NSA’s high accuracy but also underscores its robustness and adaptability across different domains and evaluation criteria.

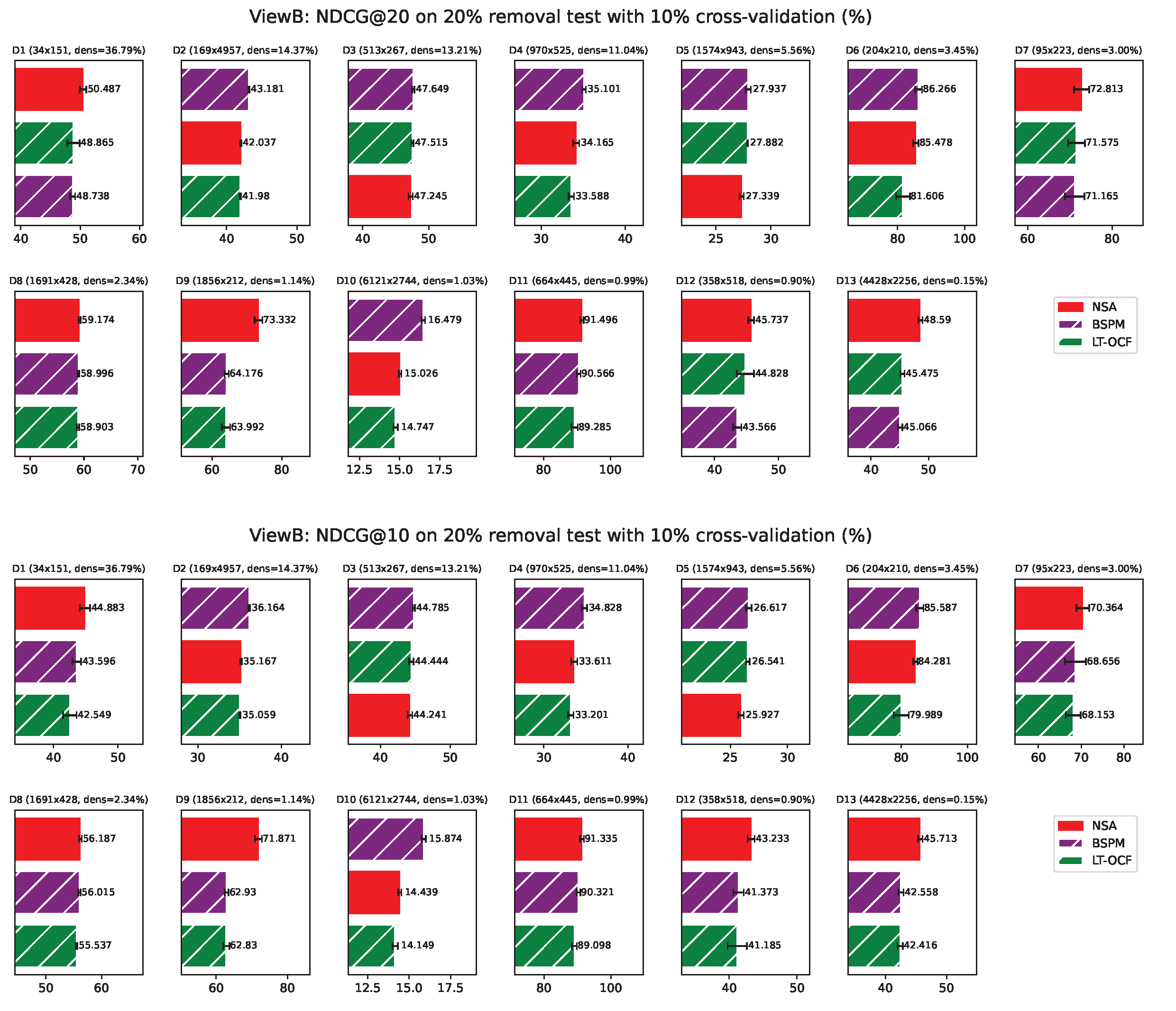

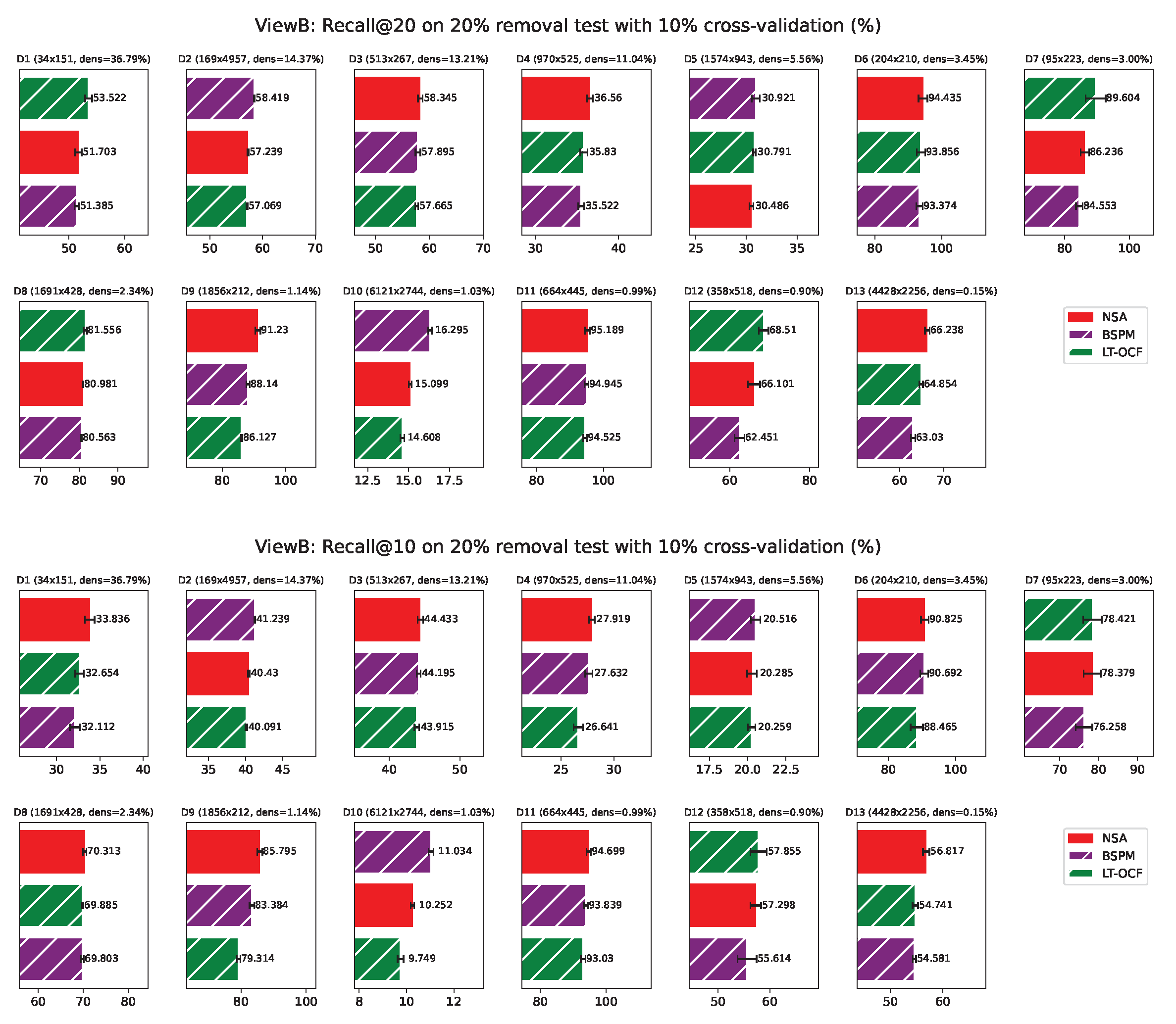

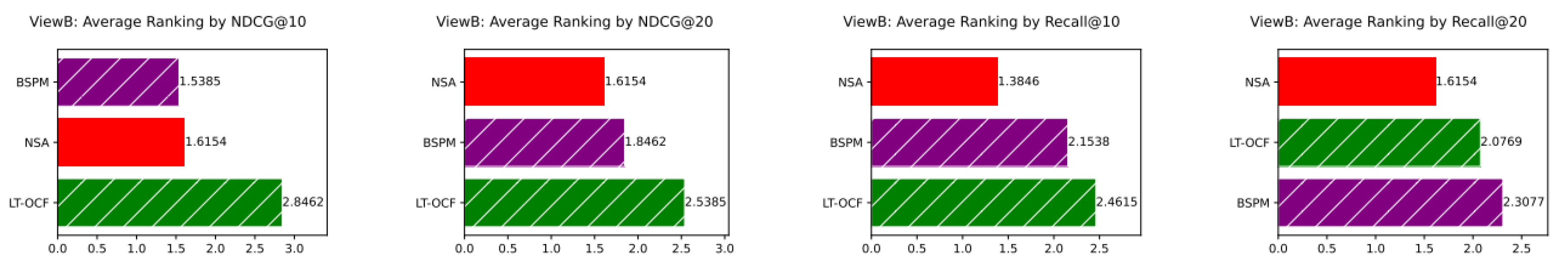

ViewB Results

NSA achieves the best average ranking across three evaluation metrics, outperforming BSPM and LT-OCF, as shown in

Figure 3. The results for ViewB organized by individual networks are provided in

Appendix G. These results further demonstrate the effectiveness and robustness of NSA.

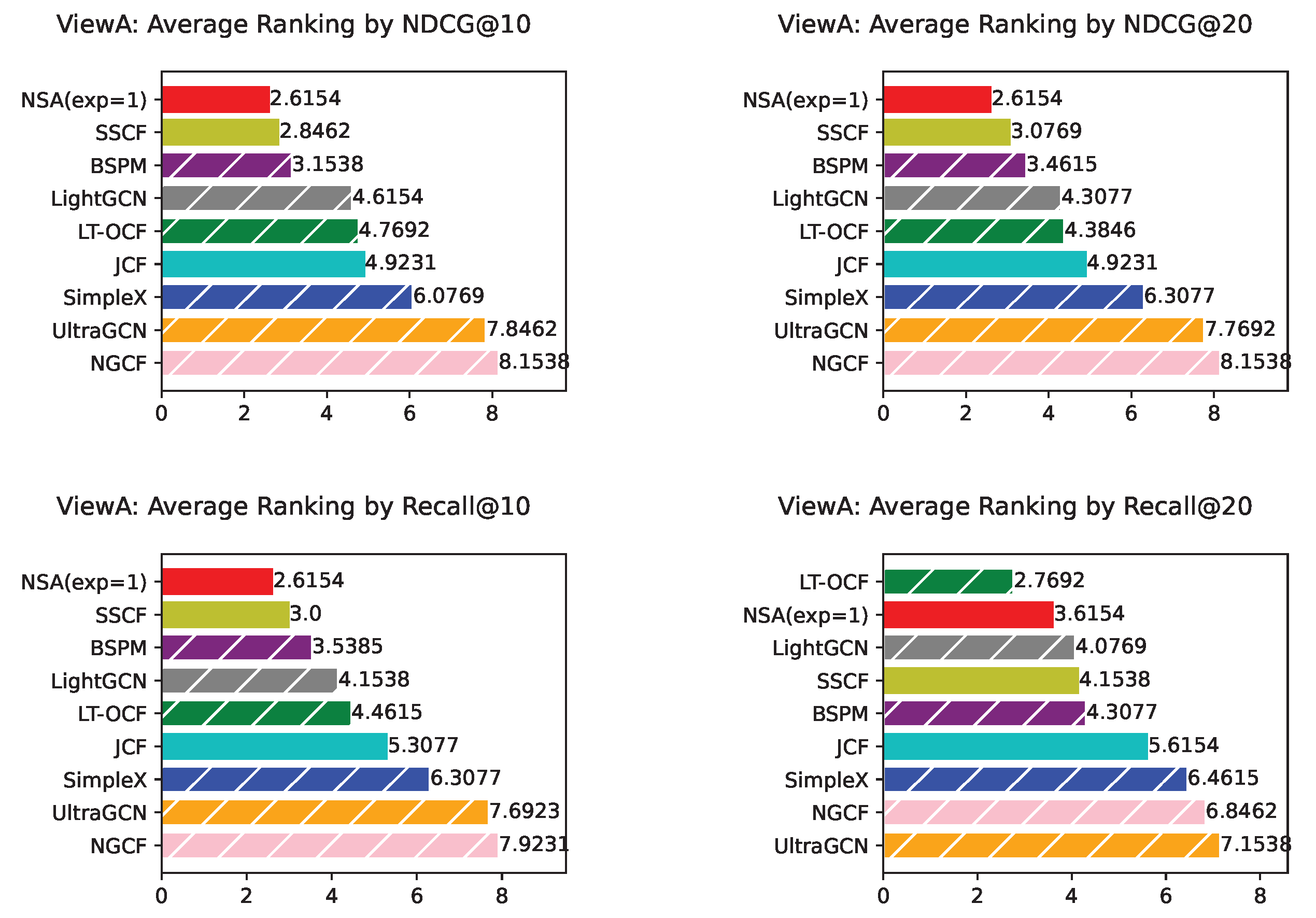

Effectiveness of a Simplified NSA Variant

To further evaluate the flexibility and robustness of NSA, we conducted an ablation study in which the exponent parameter was fixed to a constant value of 1 without tuning in the validation stage. Interestingly, it still achieved impressive results from ViewA, ranking first on average evaluated by multiple metrics. The detailed results are provided in

Appendix H. This finding demonstrates the strong performance of NSA even under a more constrained configuration.

Training-Free Robustness of NSA

While NSA achieves strong overall performance, we observe that it performs slightly less competitively than certain model-based methods specifically on Recall@20. This discrepancy may stem from the epoch selection strategies commonly employed by model-based approaches. In contrast, NSA is a non-training method and thus does not involve such metric-specific tuning so that it avoids potential bias introduced by overfitting and maintains consistently strong performance across other key metrics. This distinction highlights NSA’s ability to preserve ranking fidelity and generalize effectively across evaluation settings, without the need for iterative optimization or metric-dependent parameter tuning.

High Sparsity Robustness of NSA

Especially on datasets under high sparsity level, NSA demonstrates strong performance compared to other methods. This indicates that NSA is more robust to networks with higher sparsity. Its advantage may stem from the incorporation of CH theory from network science, which enables it to extract more informative signals from the inherently sparse structures found in real-world networks.

6. Conclusion and Discussion

In this paper, we propose Network Shape Automata (NSA), a novel memory-based collaborative filtering method that leverages bipartite network topology for recommendation. Building on recent progress in memory-based methods, NSA further explores the potential of this class of approaches, emphasizing simplicity, interpretability, and strong performance. NSA introduces the Cannistraci-Hebb (CH) theory from network science as the foundation for its similarity measure. This theory, inspired by the evolution of brain neural networks, enables NSA to utilizing local community structures based on topological features of real-world networks, without requiring any training. We evaluate NSA on 13 real-world bipartite datasets across multiple domains and compare it against both memory-based and model-based collaborative filtering methods. We conducted experiments on networks with up to 9865 nodes and 172206 edges, making it difficult to scale to larger networks due to the extensive experimental setup: for ViewA alone, we performed thorough hyperparameter learning and evaluation on 13 networks using 9 methods, each with 3 hyperparameters (averaging 9 settings), across 10 realizations with 10 validation samplings, resulted in a total of 105300 model assessments. Experimental results show that NSA consistently outperforms strong baselines across multiple evaluation metrics. It also demonstrates notable robustness under high sparsity, while preserving the desirable traits of memory-based approaches. Overall, NSA highlights the overlooked potential of memory-based collaborative filtering in modern recommendation systems and validates the effectiveness of the Cannistraci-Hebb theory in modeling network evolution for link prediction and recommendation tasks.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Zhou Yahui Chair Professorship award of Tsinghua University (to CVC), the National High- Level Talent Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant number 20241710001, to CVC).

Appendix A. Classification of Collaborative Filtering

In

Figure A1, we illustrate that collaborative filtering can be further divided into memory-based and model-based method. NSA can be classified as a memory-based approach.

Figure A1.

The classification of Collaborative Filtering.

Figure A1.

The classification of Collaborative Filtering.

Appendix B. Statistics of Datasets

In this section, we present the detailed statistics of all the datasets we used for test. In

Table A1, we summarized the source, number of nodes, type of nodes and density of each dataset. For clarity, we give each dataset an index in descending order considering network density.

Table A1.

Statistics of Datasets.

Table A1.

Statistics of Datasets.

| Index |

Name |

Field |

TypeA |

#NodeA |

TypeB |

#NodeB |

#Link |

Density |

| D1 |

aidorganizations_issues [38] |

Social |

orgnization |

151 |

issue |

34 |

1889 |

36.79% |

| D2 |

export [42] |

Social |

country |

169 |

item |

4957 |

120377 |

14.37% |

| D3 |

industries_educationfields_IPUMS [39] |

Social |

industry |

267 |

education |

513 |

18088 |

13.21% |

| D4 |

congressmen_topics_US [40] |

Social |

congressmen |

525 |

topic |

970 |

56215 |

11.04% |

| D5 |

users_movies_movielens100k |

Social |

user |

943 |

movie |

1574 |

82520 |

5.56% |

| D6 |

drug_target_ionchannel_2009 [41] |

Biological |

drug |

210 |

target |

204 |

1476 |

3.45% |

| D7 |

drug_target_GPCR_2009 [41] |

Biological |

drug |

223 |

target |

95 |

635 |

3.00% |

| D8 |

occupations_tasks_ONET [40] |

Social |

occupation |

428 |

task |

1691 |

16936 |

2.34% |

| D9 |

tfs_genes_regulation_ecoli |

Biological |

protein |

212 |

gene |

1856 |

4496 |

1.14% |

| D10 |

amazon-product [45,46] |

Social |

user |

6121 |

item |

2744 |

172206 |

1.03% |

| D11 |

drug_target_enzyme_2009 [41] |

Biological |

drug |

445 |

target |

664 |

2926 |

0.99% |

| D12 |

drug_target_HQ_2014 [43] |

Biological |

drug |

518 |

target |

358 |

1666 |

0.90% |

| D13 |

drug_target_moesm4_esm [44] |

Biological |

drug |

4428 |

target |

2256 |

15051 |

0.15% |

Appendix C. Experimental Environment

The NSA experiments are conducted in a CPU-based computing environment equipped with an AMD processor featuring 64 cores, using MATLAB and C++. The number of CPU cores employed during execution is configurable, allowing flexible adaptation to the available computational resources.

Appendix D. Hyperparameter Setting

For all the baseline methods we’re using, we listed all the hyperparameters we used for experiments in

Table A2 (the rows with yellow background refer to the tuned parameters). For memory-based methods, there’s limited range for hyperparameters to tune. For model-based methods, we chose the appropriate range of hyperprameter based on what mentioned in literature and preliminary experiments for each dataset.

Table A2.

Hyperparameters For Different Methods.

Table A2.

Hyperparameters For Different Methods.

| Classification |

Algorithm |

Parameter |

Tuning value |

| Memory-based |

|

CH index |

CH3-L2, CH3.1-L2 |

| |

denominator |

sum of degree, sum of nlcl, union of neighbours |

| |

exponent |

1, 2 |

| |

bipartite scoring |

sum, normalization |

| NSA |

mixing parameter |

0-1, interval 0.1 |

| SSCF |

mixing parameter |

0-1, interval 0.1 |

| JCF |

mixing parameter |

0-1, interval 0.1 |

| Model-based |

|

lr |

1e-3, 1e-4, 1e-5 |

| |

reg |

1e-4, 1e-5, 1e-6 |

| |

embed_size |

64 |

| |

layer size |

[64, 64, 64] |

| |

batch size |

1024 |

| |

node dropout |

0.1 |

| NGCF |

mess dropout |

[0.1, 0.1, 0.1] |

| |

lr |

1e-2, 1e-3, 1e-4 |

| |

decay |

1e-3, 1e-4, 1e-5 |

| |

recdim |

64 |

| |

dropout |

0 |

| |

layer |

3 |

| LightGCN |

bpr_batch |

2048 |

| |

lr |

1e-3, 1e-4, 1e-5 |

| |

gamma |

0.8, 0.5 |

| |

negative weight |

250, 10 |

| |

embedding_dim |

64 |

| |

num neg |

1000 |

| |

margin |

0.9 |

| |

net_dropout |

0.1 |

| SimpleX |

batch size |

1024 |

| |

lr |

1e-2, 1e-1 |

| |

gamma |

1e-3, 1e-4, 1e-5 |

| |

lambda |

5e-4, 1e-5 |

| |

batch size |

512 |

| |

negative weight |

300 |

| UltraGCN |

embedding dim |

64 |

| |

lr |

1e-2, 1e-3, 1e-4 |

| |

k |

4, 2 |

| |

decay |

1e-4 |

| LT-OCF |

lrt |

1e-5 |

| |

lr |

1e-3, 1e-2 |

| |

idl_betas |

0.2, 0.3 |

| |

factor_dims |

12, 50 |

| |

decay |

1e-4 |

| |

dropout |

0 |

| BSPM |

layer |

3 |

Appendix E. Hyperparameter Learning and Evaluation Process

To better illustrates the evaluation process, we present the whole procedure by a figure. Note that, for time reason, ViewA results are the average among 10 realizations, while ViewB results are based on 5 realizations. For each realization, we conducted 10 validation samplings to find the best hyperparameter setting. Also, for different metrics, the best hyperparameter settings can be different.

Figure A2.

Hyperparameter Learning and Evaluation procedure. We conducted thorough hyperparameter learning and evaluation for each method according to this to get the final performance: (1) split the original dataset for different realizations; (2) for each realization, conduct 10 validation samplings to determine the best setting and then utilized it for evaluation; (3) report the final average performance across all realizations.

Figure A2.

Hyperparameter Learning and Evaluation procedure. We conducted thorough hyperparameter learning and evaluation for each method according to this to get the final performance: (1) split the original dataset for different realizations; (2) for each realization, conduct 10 validation samplings to determine the best setting and then utilized it for evaluation; (3) report the final average performance across all realizations.

Appendix F. ViewA Results on Individual Network

For page limit, results from ViewA evaluated by different metics on each network are reported here. Since the scale of some datasets can be small, it is of significance to evaluate the performance based on both top 20 and top 10 performance. Here we can find that NSA is competitive across different metrics.

Figure A3.

ViewA: Performance evaluated by NDCG on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewA means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set A as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Figure A3.

ViewA: Performance evaluated by NDCG on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewA means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set A as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Figure A4.

ViewA: Performance evaluated by Recall on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewA means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set A as users.

Figure A4.

ViewA: Performance evaluated by Recall on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewA means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set A as users.

Appendix G. ViewB Results on Individual Network

In this section, we present the results from ViewB. For time reason, only BSPM and LT-OCF which are the two model-based methods shows the most potential from ViewA. With 5 tests repeated, NSA remains competitive on different metrics.

Figure A5.

ViewB: Performance evaluated by NDCG on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewB means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set B as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Figure A5.

ViewB: Performance evaluated by NDCG on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewB means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set B as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Figure A6.

ViewB: Performance evaluated by Recall on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewB means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set B as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Figure A6.

ViewB: Performance evaluated by Recall on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewB means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set B as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Appendix H. NSA with Fixed Exponent 1 Results from ViewA

In this section, we reported the results of simplified version NSA, with its configurable exponent being fixed to 1. Surprisingly we found that it performs quite well, with its average ranking consistently being the first across all the metrics we test.

Figure A7.

ViewA: NSA(exp=1) Performance evaluated by NDCG on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewA means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set A as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Figure A7.

ViewA: NSA(exp=1) Performance evaluated by NDCG on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewA means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set A as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Figure A8.

ViewA: NSA(exp=1) Performance evaluated by Recall on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewA means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set A as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Figure A8.

ViewA: NSA(exp=1) Performance evaluated by Recall on individual dataset. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewA means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set A as users. Error bars represent sample standard deviation (with degrees of freedom = 1).

Figure A9.

ViewA: NSA(exp=1) Average ranking across 13 datasets evaluated by different metrics. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewB means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set B as users.

Figure A9.

ViewA: NSA(exp=1) Average ranking across 13 datasets evaluated by different metrics. Bars corresponding to model-based approaches are overlaid with white hatching. *ViewB means that these experiments are conducted treating nodes in set B as users.

Appendix I. Broader Impact and Future Work

Broader Impact

NSA is a link prediction model applicable to recommendation systems and network modeling tasks. Its simplicity makes it both interpretable and easy to implement and integrate into existing infrastructures. Potential real-world applications include personalized content delivery and modeling social connections (e.g., friend suggestions on social platforms). However, like other link prediction models, NSA may unintentionally amplify existing biases or propagate misinformation, particularly when deployed without proper safeguards. To mitigate such risks, practitioners should regularly audit model outputs, monitor their downstream impact in live environments, and incorporate human feedback mechanisms to ensure responsible use.

Future Work

NSA is built upon the principles of memory-based methods, which, while effective and offering higher interpretability, can be sensitive to network scale, as they often require access to the entire dataset to aggregate interaction information. In contrast, model-based methods offer better scalability through iterative processing and compact representations. Future work could focus on combining NSA with model-based techniques to enhance scalability, exploring sampling strategies to reduce memory consumption, and developing online or incremental variants of NSA that are suitable for streaming or dynamically evolving networks. Furthermore, investigating NSA’s robustness and fairness under adversarial or biased conditions would further strengthen its practical applicability.

Appendix J. Time Complexity of NSA

In this section, we’ll explain the time complexity of our method NSA. We’ll start with the basic definition and explain the time complexity step by step.

Appendix J.1. Basic Definition

U: number of users

I: number of items

Appendix J.2. CH Scoring and Monopartite Projection

Appendix J.2.2.15. CH index

The time complexity of CH index on path of length 2 computation is determined by the cost of computing iLCL and eLCL statistics for the intermediate nodes along those paths. Here we’ll discuss the time complexity in a general case, where n and m denote the number of nodes and edges in a network, respectively. is the average degree.

Path count. Each length-2 path

is defined by an intermediate node

z connected to both

u and

v. The total number of such paths is given by:

where

is the degree of node

z. This represents the number of unique unordered two-hop paths in the network.

Computation per path. For each length-2 path, CHA computes a score based on the iLCL and eLCL of the intermediate node z. This requires checking the neighbors of z against the local community associated with the pair , which takes time per path.

Overall time complexity. Multiplying the path count and per-path cost gives the total time complexity:

We now analyze this quantity under three typical network regimes:

-

Sparse, degree-homogeneous: If the graph is Sparse (i.e.

) with relatively uniform degrees (i.e.,

for all

z), then:

So the overall time complexity of .

-

Sparse, degree-heterogeneous: If the graph is sparse (i.e.,

), but has a skewed degree distribution (e.g., power law), we can no longer assume

for all nodes. To handle this case, we apply a relaxation via Hölder’s inequality to upper-bound the root-mean-cube degree

in terms of the average degree:

This relaxation allows us to express the cubic-degree term in the overall complexity as:

Thus, the overall time complexity in this case is .

Dense graphs: In the worst-case scenario of dense graphs, where

for all nodes, we obtain:

leading to an overall time complexity of

.

We compute CH index on the whole bipartite network, which means that in our case, .

Denominator

The computation of denominator is related to common neighbors () between two nodes of same kind. The computation of common neighbors between two nodes of same kind is implemented by the dot product of the adjacent matrix and its transpose. This procedure is offline and the results can be reused always. For user based, it’s of time complexity , while for item based it’s of time complexity . Since we want the similarity score on two projected monopartite networks, we only need to consider computations of denominator. The final time complexity of denominator computation can be .

Appendix J.3. Bipartite Scoring

In this step, we aggregate the similarity scores on two monopartite networks separately to the link prediction scores. For instance, when we compute the user-based link prediction score, we utilized the user similarity matrix of size and adjacent matrix of size utilizing sum or normalization method. For each user-item pair, we compute the score using all the user’s similarity corresponding to our target user so that the complexity can be U exactly. Hence, the user based link prediction complexity should be multiplied with all pairs of user-item pair and result in time complexity of . Correspondingly the item based link prediction score time complexity can be of . The total time complexity in this step can be .

Appendix J.4. Mix Item and User Scores

For each user-item pair, we aggregate user and item score, so that the time complexity is

Appendix J.5. Summary

Corresponding the different network regime mentioned in

Appendix J.2, we summarize here the overall time complexity of NSA.

Sparse, degree-homogeneous: The dominant component of the time complexity is the collaborative filtering mechanism, result in overall complexity of .

Sparse, degree-heterogeneous: The dominant component of the time complexity is CH score computation, result in overall complexity of .

Dense graphs: The dominant component of the time complexity is CH score computation, result in overall complexity of which is rare for recommendation system tasks.

Appendix K. Experimental Time

In this section, we listed the running time of each method on different datasets with one hyperparameter setting in

Table A3.

Table A3.

Summary of Running Time. All reported times are averaged over three runs. Experiments for memory-based methods were conducted on an AMD Ryzen Threadripper PRO 3995WX CPU with 64 physical cores, while other methods were conducted on an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU. All time values are expressed in seconds (s).

Table A3.

Summary of Running Time. All reported times are averaged over three runs. Experiments for memory-based methods were conducted on an AMD Ryzen Threadripper PRO 3995WX CPU with 64 physical cores, while other methods were conducted on an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU. All time values are expressed in seconds (s).

| Dataset |

NSA |

SSCF |

JCF |

NGCF |

LightGCN |

UltraGCN |

SimpleX |

LT-OCF |

BSPM |

| aidorganizations_issues |

0.06± 0.00 |

0.06± 0.00 |

0.06± 0.00 |

28.90± 1.52 |

11.30± 0.07 |

35.80± 0.74 |

22.39± 0.42 |

13.41± 0.09 |

17.31± 0.27 |

| export |

5.40± 0.01 |

1.55± 0.00 |

1.20± 0.00 |

1129.81± 8.55 |

435.42± 3.44 |

277.43± 2.16 |

267.52± 0.63 |

617.89± 31.94 |

22.75± 0.03 |

| industries_eductionfields_IPUMS |

0.35± 0.00 |

0.34± 0.00 |

0.40± 0.00 |

150.53± 2.49 |

67.50± 0.54 |

75.34± 0.37 |

34.17± 0.94 |

96.63± 0.85 |

17.99± 0.13 |

| congressmen_topics_US |

1.21± 0.01 |

1.24± 0.00 |

1.41± 0.02 |

340.44± 1.96 |

209.35± 2.30 |

157.58± 1.26 |

113.68± 3.61 |

269.45± 4.39 |

18.97± 0.20 |

| users_movies_movielens100k |

2.90± 0.00 |

3.15± 0.01 |

3.65± 0.01 |

477.04± 5.27 |

288.40± 0.68 |

205.45± 2.18 |

132.38± 2.65 |

402.87± 2.50 |

19.33± 0.07 |

| drug_target_ionchannel_2009 |

0.13± 0.00 |

0.13± 0.00 |

0.12± 0.00 |

70.05± 2.24 |

9.85± 0.37 |

35.58± 0.70 |

12.84± 0.41 |

11.10± 0.27 |

17.71± 0.04 |

| drug_target_GPCR_2009 |

0.09± 0.00 |

0.09± 0.00 |

0.09± 0.00 |

39.53± 1.36 |

6.98± 0.06 |

34.92± 1.14 |

13.85± 0.95 |

8.58± 0.13 |

17.87± 0.13 |

| occupations_tasks_ONET |

1.32± 0.00 |

1.51± 0.00 |

1.76± 0.01 |

141.58± 0.41 |

61.06± 0.37 |

76.30± 0.47 |

63.22± 2.62 |

83.36± 0.36 |

17.91± 0.12 |

| tfs_genes_regulation_ecoli |

0.65± 0.00 |

1.00± 0.00 |

0.57± 0.01 |

82.75± 0.23 |

19.40± 0.13 |

41.33± 0.54 |

24.49± 0.93 |

23.85± 0.11 |

18.04± 0.05 |

| amazon-product |

26.81± 0.12 |

25.67± 0.05 |

25.25± 0.14 |

924.45± 6.48 |

600.66± 1.88 |

385.63± 1.44 |

394.01± 2.27 |

836.37± 4.80 |

22.19± 0.05 |

| drug_target_enzyme_2009 |

0.37± 0.00 |

0.54± 0.00 |

0.30± 0.00 |

64.72± 0.05 |

14.46± 0.20 |

39.43± 1.12 |

12.96± 0.24 |

19.76± 0.14 |

17.70± 0.11 |

| drug_target_HQ_2014 |

0.32± 0.00 |

0.43± 0.00 |

0.30± 0.00 |

67.52± 0.36 |

10.33± 0.12 |

35.92± 1.32 |

18.43± 0.59 |

12.29± 0.27 |

17.83± 0.09 |

| drug_target_moesm4_esm |

12.30± 0.10 |

16.36± 0.04 |

11.66± 0.01 |

135.00± 2.90 |

60.33± 0.11 |

74.57± 0.37 |

58.64± 1.48 |

85.20± 0.63 |

18.85± 0.07 |

Appendix L. Time Complexity of Baselines

Appendix L.1. Definition

For clarification, all the mathematical symbol mentioned below are defined here.

U: number of users

I: number of items

E: number of edges in the network

L: number of layers for neural-network based methods

D: dimension of embedding in model-based methods

N: number of negative samples

K: number of sampling similar neighbors

T: number of epochs for neural-network based methods

Appendix L.2. Time Complexity

We list below the time complexities of the baseline methods, based on their respective descriptions in the original papers.

References

- Watts, D.J.; Strogatz, S.H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’networks. nature 1998, 393, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albora, G.; Zaccaria, A.; et al. Machine learning to assess relatedness: the advantage of using firm-level data. Complexity 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacchella, A.; Cristelli, M.; Caldarelli, G.; Gabrielli, A.; Pietronero, L. A new metrics for countries’ fitness and products’ complexity. Scientific reports 2012, 2, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straccamore, M.; Pietronero, L.; Zaccaria, A. Which will be your firm’s next technology? Comparison between machine learning and network-based algorithms. Journal of Physics: Complexity 2022, 3, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, F.; Rokach, L.; Shapira, B. Recommender systems: Techniques, applications, and challenges. Recommender systems handbook.

- Goldberg, D.; Nichols, D.; Oki, B.M.; Terry, D. Using collaborative filtering to weave an information tapestry. Communications of the ACM 1992, 35, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J.B.; Frankowski, D.; Herlocker, J.; Sen, S. Collaborative filtering recommender systems. In The adaptive web: methods and strategies of web personalization; Springer, 2007; pp. 291–324.

- Chen, R.; Hua, Q.; Chang, Y.S.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; Kong, X. A survey of collaborative filtering-based recommender systems: From traditional methods to hybrid methods based on social networks. IEEE access 2018, 6, 64301–64320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albora, G.; Mori, L.R.; Zaccaria, A. Sapling similarity: A performing and interpretable memory-based tool for recommendation. Knowledge-Based Systems 2023, 275, 110659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscoloni, A.; Abdelhamid, I.; Cannistraci, C.V. Local-community network automata modelling based on length-three-paths for prediction of complex network structures in protein interactomes, food webs and more. bioRxiv, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscoloni, A.; Michieli, U.; Cannistraci, C.V. Adaptive network automata modelling of complex networks 2020.

- Cannistraci, C.V.; Alanis-Lobato, G.; Ravasi, T. From link-prediction in brain connectomes and protein interactomes to the local-community-paradigm in complex networks. Scientific reports 2013, 3, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, I.; Muscoloni, A.; Rotscher, D.M.; Lieber, M.; Markwardt, U.; Cannistraci, C.V. Network shape intelligence outperforms AlphaFold2 intelligence in vanilla protein interaction prediction. bioRxiv, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, W.; Muscoloni, A.; Cannistraci, C.V. Ultra-sparse network advantage in deep learning via Cannistraci-Hebb brain-inspired training with hyperbolic meta-deep community-layered epitopology. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; He, X.; Wang, M.; Feng, F.; Chua, T.S. Neural graph collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 42nd international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in Information Retrieval, 2019, pp. 165–174.

- He, X.; Deng, K.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. Lightgcn: Simplifying and powering graph convolution network for recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in Information Retrieval, 2020, pp. 639–648.

- Mao, K.; Zhu, J.; Xiao, X.; Lu, B.; Wang, Z.; He, X. UltraGCN: ultra simplification of graph convolutional networks for recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM international conference on information & knowledge management, 2021, pp. 1253–1262.

- Mao, K.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Dai, Q.; Dong, Z.; Xiao, X.; He, X. SimpleX: A simple and strong baseline for collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, 2021, pp. 1243–1252.

- Choi, J.; Jeon, J.; Park, N. Lt-ocf: learnable-time ode-based collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, 2021, pp. 251–260.

- Choi, J.; Hong, S.; Park, N.; Cho, S.B. Blurring-sharpening process models for collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 46th international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval, 2023, pp. 1096–1106.

- Zhou, T.; Ren, J.; Medo, M.; Zhang, Y.C. Bipartite network projection and personal recommendation. Physical review E 2007, 76, 046115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, P.; Wu, J.; Di, Z. The effect of weight on community structure of networks. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its applications 2007, 378, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E. Scientific collaboration networks. II. Shortest paths, weighted networks, and centrality. Physical review E 2001, 64, 016132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusilovski, P.; Kobsa, A.; Nejdl, W. The adaptive web: methods and strategies of web personalization; Vol. 4321, Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- Breese, J.S.; Heckerman, D.; Kadie, C. Empirical analysis of predictive algorithms for collaborative filtering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.7363, arXiv:1301.7363 2013.

- Su, X.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey of collaborative filtering techniques. Advances in artificial intelligence 2009, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liben-Nowell, D.; Kleinberg, J. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the twelfth international conference on Information and knowledge management, 2003, pp. 556–559.

- Jaccard, P. Étude comparative de la distribution florale dans une portion des Alpes et des Jura. Bull Soc Vaudoise Sci Nat 1901, 37, 547–579. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Lü, L.; Zhang, Y.C. Predicting missing links via local information. The European Physical Journal B 2009, 71, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shardanand, U.; Maes, P. Social information filtering: Algorithms for automating “word of mouth”. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems, 1995, pp. 210–217.

- Chen, L.; Wu, L.; Hong, R.; Zhang, K.; Wang, M. Revisiting graph based collaborative filtering: A linear residual graph convolutional network approach. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 27–34.

- Barabási, A.L.; Albert, R. Emergence of Scaling in Random Networks. Science 1999, 286, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, F.; Kitsak, M.; Serrano, M.Á.; Boguñá, M.; Krioukov, D. Popularity versus similarity in growing networks. Nature 2012, 489, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscoloni, A.; Cannistraci, C.V. A nonuniform popularity-similarity optimization (nPSO) model to efficiently generate realistic complex networks with communities. New Journal of Physics 2018, 20, 052002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, S.; Gad-el Hak, M. A new kind of science. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2003, 56, B18–B19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M.; Onnela, J.P.; Lee, C.F.; Fricker, M.D.; Johnson, N.F. Network automata: Coupling structure and function in dynamic networks. Advances in Complex Systems 2011, 14, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannistraci, C.V. Modelling self-organization in complex networks via a brain-inspired network automata theory improves link reliability in protein interactomes. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 15760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscia, M.; Hausmann, R.; Hidalgo, C.A. The structure and dynamics of international development assistance. Journal of Globalization and Development 2013, 3, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggles, S.; Hacker, J.D.; Sobek, M. General design of the integrated public use microdata series. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 1995, 28, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M.A.; Coscia, M. Using random walks to generate associations between objects. PloS one 2014, 9, e104813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanishi, Y.; Araki, M.; Gutteridge, A.; Honda, W.; Kanehisa, M. Prediction of drug–target interaction networks from the integration of chemical and genomic spaces. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, i232–i240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassa, B. Trade liberalisation and “revealed” comparative advantage 1. The manchester school 1965, 33, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Bajorath, J. Monitoring drug promiscuity over time. F1000Research 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Kovács, I.A.; Barabási, A.L. Network-based prediction of drug combinations. Nature communications 2019, 10, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, J.; Targett, C.; Shi, Q.; Van Den Hengel, A. Image-based recommendations on styles and substitutes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 38th international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval, 2015, pp. 43–52.

- Pasricha, R.; McAuley, J. Translation-based factorization machines for sequential recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 12th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 2018, pp. 63–71.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).