Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Brief History of Livestock Transportation Regulation in Canada

3. Good Law

3. Bad Law, Symbolic Law, Not Law at All

4. Soft Law

5. Mutant Law - Street Level – Judicial Review

6. Methods

7. Results

8. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Author Note

References

- OIE. Appendix 3.7.3 Guidelies for the transport of animals by land. 2006 OIE Terrstrial Animal Health Code Strasbourg,: Office Internationale des Epizooties 2006. p. 429-41.

- Bench C, Schaefer A, Faucitano L. The welfare of pigs during transport. In: Luigi Faucitano, Schaefer AL, editors. Welfare of pigs from birth to slaughter. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic; 2008. p. 161-95.

- Loly, CM. The rise and fall of the cattle train in Canada. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba; 1995.

- CFIA. A history of the changes to the transportation of animals requirements under the Health of Animals Regulations (HAR) Part XII Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2024. Available online: https://inspection.canada.ca/en/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/humane-transport/timeline-humane-transport-regulations (accessed on 18 February 2019).

- Fitzgerald R, Stalder K, Matthews J, Schultz Kaster C, Johnson A. Factors associated with fatigued, injured, and dead pig frequency during transport and lairage at a commercial abattoir. J Anim Sci. 2009, 87, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doughty A, McArthur, DA. Documents relating to the constitutional history of Canada,1791-1818, vol. II1914:[xiii, 576 pages pp.]. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_03421.

- Britian, G. An Act to prevent cruel and improper treatment of Cattle and other Animals, and to amend the Law relating to impounding the same 1857:[111-9 pp.]. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_00925_5.

- Canada. The consolidated statutes of Canada : being the public general statutes which apply to the whole province as revised and consolidated by the commissioners appointed for that purpose.1859:[xiii, 1247 pages ; 32 cm. pp.]. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08189.

- Lower-Canada. An Ordinance for establishing an efficent system of Police in the Cities of Quebec and Montreal. Lower Canada The revised acts and ordinances of Lower-Canada [Internet]. 1845. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_00928.

- Britian, G. The British North America act, 1867 and amending acts.1867. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_04236.

- Canada. Acts of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada ... second session of the third Parliament, begun and holden at Ottawa, on the fourth day of February, and closed by prorogation on the eighth day of April, 1875 : public general acts : 1875 (pt. 1) (Acts 1-56)1875. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08051_4_1.

- Goding H, Raub AJ. The 28 Hour Law Regulating the Interstate Transportation of Live Stock: Its Purpose, Requirements, and Enforcement: US Department of Agriculture; 1918.

- Canada. Acts of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada, relating to criminal law, to procedure in criminal cases and to evidence : compiled from the Revised Statutes of Canada, which were ... brought into force on 1st March, 1887, under proclamation dated 24th January, 1887 ; with marginal references to corresponding Imperial Acts.1887. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_02000.

- Canada. The Criminal Code: Acts of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada ... second session of the seventh Parliament, begun and holden at Ottawa, on the twenty-fifth day of February and closed by prorogation on the ninth day of July, 1892 : public general acts : 1892 (pt. 1) (Acts 1-29)1892. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08051_21_1.

- Canada. Chapter 51 the Criminal Code1954. Available online: https://www.lareau-legal.ca/Martin1955two.pdf.

- Canada. Bill C-28 An Act to amend the Animal Contagious Diseases Act. House of Commons Bills, 30th Parliament, 1st Session : C23-C31 [Internet]. 1975; (C-28):[245-86 pp.]. Available online: https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.HOC_30_1_C23_C31/256.

- Canada. Respecting:Bill C-28 An Act to amend the Animal Contagious Diseases Act. House of Commons Committees, 30th Parliament, 1st Session : Standing Committee on Agriculture, vol 2 no 36-66 [Internet]. 1975:[1347-403 pp.]. Available online: https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.com_HOC_3001_1_2/1347.

- Whiting, TL. Policing farm animal welfare in federated nations: The problem of dual federalism in Canada and the USA. Animals 2013, 3, 1086–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltelli A, Dankel DJ, Di Fiore M, Holland N, Pigeon M. Science, the endless frontier of regulatory capture. Futures 2022, 135, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. Evaluation of the Contraventions Act Program - Final Report. In: Justice, editor. Ottawa, ON: Canada, Department of Justice; 2021.

- Fuller, LL. The morality of law (2nd ed). New Haven: Yale University Press; 1969.

- Murphy, C. Lon Fuller and the moral value of the rule of law. Law & Phil. 2005, 24, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Eliantonio M, Korkea-aho E. Soft law and courts: saviours or saboteurs of the rule of (soft) law? Research Handbook on Soft Law: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2023. p. 191-207.

- Van Klink, B. Symbolic legislation: an essentially political concept. Symbolic legislation theory and developments in biolaw. 2016, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bielska-Brodziak A, Drapalska-Grochowicz M, Suska M. Symbolic protection of animals. Society Register. 2019, 3, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Newig, J. Symbolic environmental legislation and societal self-deception. Enviro Poli 2007, 16, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrere, M. The (symbolic) legislative recognition of animal sentience. Animal L. 2022, 28, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Ferrere, M. Animal welfare Underenforcement as a rule of law problem. Animals. 2022, 12, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, LL. Eight ways to fail to make law. Philosophy of law. 2000, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, CR. On the expressive function of law. U Pa L Rev. 1996, 144, 2021–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviram, A. The Placebo Effect of Law: Law’s Role in Manipulating Perceptions. Geo Wash L Rev. 2006, 75, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Kamin, S. Against a “War on Animal Cruelty” Lessons from the War on Drugs and Mass Incarceration. In: Lori Gruen JM, editor. Carceral Logics Human Incarceration and Animal Captivity: Cambridge University Press; 2022.

- McPherson, L. The Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA) at 10 years: History, implementation, and the future. Drake L Rev. 2016, 64, 741. [Google Scholar]

- Cubellis MA, Walfield SM, Harris AJ. Collateral consequences and effectiveness of sex offender registration and notification: Law enforcement perspectives. Int’l J Offend Therapy & Comp Criminology. 2018, 62, 1080–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Suska, M. Becoming Symbolic: Some Remarks on the Judicial Rewriting of the Offence of Animal Abuse in Poland. Int J Semiot Law. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Yes, Chickens Have Feelings Too. The Recognition of Animals Sentience Will Address Outdated Animal Protection Laws for Chickens and Other Poultry in the United States. San Diego Int’l L J. 2020, 22, 335. [Google Scholar]

- Landi M, Anestidou L. Animal Sentience Should Be The Key For Future Legislation. Animal L. 2024, 30, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Lessard, M. Can Sentence Recognition Protect Animals? Lessons from Quebec’s Animal Law Reform. Animal L. 2021, 27, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Sossin L, Van Wiltenburg C. The puzzle of soft law. Osgoode Hall LJ. 2021, 58, 623–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canada. Regulatory guidance and resources for the humane transport of animals Ottawa, ON: Canadian Food Inspection Agency; 2025. Available online: https://inspection.canada.ca/en/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/humane-transport/guidance-and-resources (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- CARC, C. Recommended code of practice for the care and handling of farm animals Transportation. Nepean, Ontario: Canadian Agri-Food Research Council; 2001. Available online: https://www.nfacc.ca/pdfs/codes/transport_code_of_practice.pdf.

- Sankoff, P. Canada’s experiment with industry self-regulation in agriculture: Radical innovation or means of insulation. Can J Comp & Contemp L. 2019, 5, 299. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan MS, Al Halbusi H, Ahmad AB, Abdelfattah F, Thamir Z, Raja Ariffin RN. Discretion and its effects: analyzing the role of street-level bureaucrats’ enforcement styles. International Review of Public Administration. 2023, 28, 480–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Winter P, Hertogh M. Public servants at the regulatory front lines. Street-Level enforcement in theory and practice. The Palgrave handbook of the public servant. 2019, 1-20.

- Bronitt SH, Stenning P. Understanding discretion in modern policing. Criminal law journal. 2011, 35, 319–332. [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau, J.; Doyon v. Canada (Attorney General), 2009 FCA 1522009; A-513-08. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/26kcr.

- CART. Decisions Ottawa, ON: Canada Agriculture Review Tribunal 2025 [Searchable Website]. Available online: https://decisions.cart-crac.gc.ca/cart-crac/en/ann.do.

- CART. 2023-2024 Annual Report. In: Tribunal CAR, editor. Ottawa, ON: Canada; 2024.

- FCA. FCA. Canada (Procureur général) c. L. Bilodeau et Fils Ltée, 2017 CAF 5 (Bilodeau)2017; (A-543-15). Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/fca/doc/2017/2017fca5/2017fca5.pdf.

- Forsyth, M. The regulation of witchcraft and sorcery practices and beliefs. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci. 2016, 12, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting TL, Brandt S. Minimum space allowance for transportation of swine by road. Can Vet J. 2002, 43, 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, KR. Science as falsification. Conjectures and refutations. 1963, 1, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Protection, WA. Animal Protection Index - Interactive Data Map London, UK: World Animal Protection, formerly The World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA), 2025 [Available online:. Available online: https://api.worldanimalprotection.org/.

- CFIA. News Release Canada’s largest science-based regulator marks 25 years of protecting food, plants and animals2022 2025-05-06. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/food-inspection-agency/news/2022/04/canadas-largest-science-based-regulator-marks-25-years-of-protecting-food-plants-and-animals.html.

- CFIA. Health of Animals Regulations: Part XII: Transport of Animals-Regulatory Amendment - Interpretive Guidance for Regulated Parties Ottawa ON: Canadian Food Inspection Agency; 2025. Available online: https://inspection.canada.ca/en/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/humane-transport/health-animals-regulations-part-xii (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- McCulloch, SP. Brexit and animal protection: Legal and political context and a framework to assess impacts on animal welfare. Animals. 2018, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (Repealed) | Replaced 2020-04-22 |

| Prohibition of Overcrowding | Overcrowding |

| 140 (1) No person shall load or cause to be loaded any animal in any railway car, motor vehicle, aircraft, vessel, crate or container if, by so loading, that railway car, motor vehicle, aircraft, vessel, crate or container is crowded to such an extent as to be likely to cause injury or undue suffering to any animal therein. | 148 (1) No person shall load an animal, or cause one to be loaded, in a conveyance or container, other than a container that is used to transport an animal in an aircraft, in a manner that would result in the conveyance or container becoming overcrowded, or transport or confine an animal in a conveyance or container, or cause one to be transported or confined, in a conveyance or container that is overcrowded. |

| 2) No person shall transport or cause to be transported any animal in any railway car, motor vehicle, aircraft, vessel, crate or container that is crowded to such an extent as to be likely to cause injury or undue suffering to any animal therein. | (2) For the purposes of subsection (1), overcrowding occurs when, due to the number of animals in the container or conveyance, (a) the animal cannot maintain its preferred position or adjust its body position in order to protect itself from injuries or avoid being crushed or trampled; (b) the animal is likely to develop a pathological condition such as hyperthermia, hypothermia or frostbite; or (c) the animal is likely to suffer, sustain an injury or die. |

| 148.1 No person shall transport an animal by air, or cause one to be transported by air, unless it is transported in a container that meets the stocking density guidelines that are set out in the Live Animals Regulations, 44th edition, published by the International Air Transport Association, as amended from time to time. |

| general | high specifying of the rules prohibiting or permitting behavior of certain kinds |

| widely promulgated |

publicly accessible rules as publicity of laws ensure citizens know what the law requires |

| prospective | specifying how individuals ought to behave in the future rather than prohibiting or sanctioning behavior that occurred in the past |

| clear | citizens should be able to identify what the laws prohibit, permit, or require |

| non-contradictory | one law cannot prohibit what another law permits |

| compliable | must not ask the impossible of the regulated |

| constant | the demands laws make on citizens should remain relatively constant, laws should not change frequently |

| congruence | there should be congruence between what written statute declares and how officials enforce those statutes. Congruence requires lawmakers to pass only laws that will be enforced and requires officials to enforce no more than is required by the laws. |

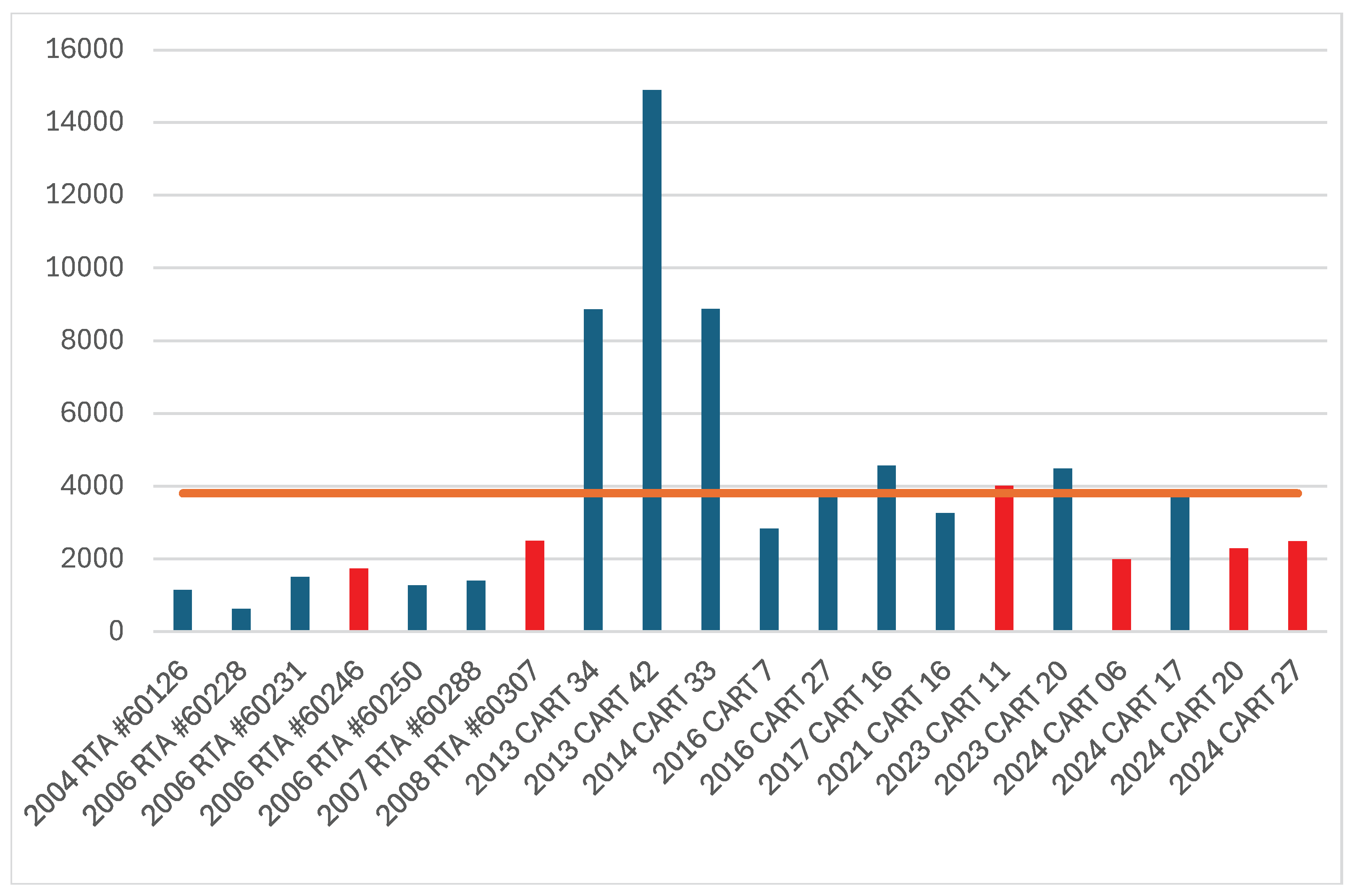

| Ref. No. | Reference | Words | Code | Math | Chair | Description | Sect. | Case turns on…. | Outcome | ||||||||||

| 2004 RTA #60126 |

F. Ménard Inc. v. Canada (CFIA) |

1137 | Y | N | TSB | August 4th, daily high of 29oC and high humidity, the Applicant loaded 115 hogs from several farms and transported them to the slaughterhouse. At the time of unloading 12 hogs were dead and the remainder of the lot were demonstrating symptoms related to heat stress. |

140(2) | The transporter did not decrease the floor pressure to the extent recommended by the Transport Code of Practice. | Notice upheld: The Applicant committed the violation and is liable for payment of the penalty in the amount of $2,000.00 to the Respondent within 30 days |

||||||||||

| 2006 RTA #60228 |

Transport Giannone- Garceau Inc. v. Canada (CFIA) |

624 | Y | Y | TSB | Applicant transported a load of chickens from Woodstock, ON to Drummondville, Quebec, (784 km) on the evening of Oct 4th and morning of October 5th. Eighty cages contained eight chickens each and five hundred and fifty-six cages contained seven chickens each. The chickens had an average live weight of 3.86 kilograms. A large number of dead birds were found in cages located in the centre of the trailer more than 10%. | 140(2) | The Transport Code recommends a maximum live weight loading density in cold weather of 63 kg/m2, equates to 7.4 chickens per cage in this case. | Notice upheld: The deaths (and undue suffering) of the chickens was caused by overcrowding in the circumstances and accordingly has established on a balance of probabilities that the Applicant committed the violation. Reduced the penalty from $4,400.00 to $2,200.00. |

||||||||||

| 2006 RTA #60231 |

René Nadeau v. Canada (CFIA) |

1497 |

Y |

Y |

TSB |

March 1st loaded 780 crates of 45 day old broiler chickens, to be transported to Grand River Poultry located in Beamsville, Ontario. At slaughter the birds were diverted to a second processor because they were too large for the processor settings. The weather conditions were fair and cool throughout transport, total travel time 26.5 hours. The Dead on arrival rate was 7.22%, 332 birds were condemned. . |

140(1) |

The recommended Code of practice for chickens the recommended maximum live weight loading floor pressure for crates in cold weather is 67.9 kgm- 2, whereas the density in this load was 71.8 kgm-2. | Notice upheld: Tribunal determined the Applicant committed the violation, by allowing these chickens to be crated and transported in the manner they were. and is liable for payment of the penalty of $2,000.00 to be paid within 30 days. |

||||||||||

| 2006 RTA #60246 |

Curtmar Farms Limited v. Canada (CFIA) |

1738 |

Y |

N |

TSB |

On March 6, two front compartments contained 12 calves in the upper section and 13 calves in the lower section on an overnight trip from Carbonear to Port aux Basques ND (866 km) took approximately ten to twelve hours and loaded on a ferry to Quebec. Weight of calves recorded but not area of compartment. |

140(1) |

Insufficient numerical data in the decision to calculate floor pressure. | Quashed: The evidence overcrowding is based almost entirely on the weight of the animals as estimated by the young and inexperienced driver, and which evidence has been put in considerable doubt by the direct evidence of the Applicant. |

||||||||||

| 2006 RTA #60250 |

Curtis Edwards v. Canada (CFIA) |

1266 | Y | N | TSB |

Loaded 45 cattle (cull dairy cows) at Prince Albert SK on Oct 26, and arrived at destination in Calgary AB on Oct. 27th, at noon, 741km distance. A downer animal was identified at Taber AB 701 km mark. This animal was Dead at arrival and 2 further animals were down. |

140(2) | The belly of the trailer contained one animal over the maximum recommended limit, and the back compartment contained 2 animals over the maximum recommended limit by reference to the Transport Code. |

Notice upheld: The Applicant committed the violation and is liable for payment of the penalty in the amount of $2,000.00 to the Respondent within 30 days. |

||||||||||

|

2007 RTA #60228 |

Timothy Wendzina v. Canada (CFIA) |

1398 |

Y |

N |

TSB |

March 1st, the Applicant transported a load of 38 dairy cattle (Holsteins with one Jersey) and a bull from the farm to XL Beef in Moose Jaw, SK approximately 250 km. The weather conditions were a temperature of -8oC, wind at 28 km/hr. gusting to 41 km/hr., windchill of -17 0C. It was overcast with light snow. On arrival there were multiple cows down in the belly of the trailer and ambulatory cattle had to be unloaded over top of one of them. Three animals were unable to stand, were recumbent, non- responsive, wet, covered in excrement, and killed on truck. |

140(2) |

The problem compartment was overcrowded by the Code standards, but dead cows were not weighed and other numerical facts do not appear in the decision. | Notice upheld: Tribunal determined the Applicant committed the violation and is liable for payment of a reduced penalty in the amount of $2,200.00. |

||||||||||

| 2008 RTA #60307 |

Brian’s Poultry Services Ltd. v. Canada (CFIA) |

2498 |

Y |

Y |

TSB |

On Oct 4, two loads of chicken; Load A 4,532 chickens (80 crates at 8 birds per crate and 556 crates at 7 birds per crate). The average weight per crate was 27.02 kg, 453 dead birds were found (10% of load). Load B 5,460 chickens (780 crates at 7 birds per crate). The average weight per cage was 26.88 kg 590 dead birds were found (10.8% of load). Both trucks travelled Woodstock ON to Drummondville PQ, 786 km |

140(1) |

BPS presented the Transport Code recommending the maximum live weight loading densities for chickens in crates in cold weather to be 63 kg/m2. Load A was 12.1% below the recommended maximum; and load B was 12.5% below the recommended maximum, Crate weight measured floor area of a crate not measured at inspection. |

Quashed: The Tribunal indicated that that death is evidence of suffering. Tribunal determined the Applicant did not commit the violation and is not liable for payment of the penalty. |

||||||||||

| 2013 CART 34 |

0830079 B.C. Ltd. v. Canada (CFIA) |

8864 |

Y |

N |

DB |

On July 25, transported 6,018 spent laying hens on 2 trailers: 3600 in Trailer A, 84 crates (28 chickens/crate) plus 48 crates (26 chickens/crate) and 2418 in trailer B, 96 crates (26 chickens/crate). At slaughter Trailer A had 703 DOA and Trailer B had 124 DOA. Size of crate not measured or not recorded in decision. |

142(2) |

Service contract stipulated 18 birds/crate. Code of practice recommended maximum was 19 bird/cage for trailer A and 18 bird/cage for trailer B. Actual number of birds loaded was 28 and 26 birds per cage. |

Notice upheld: On the balance of probabilities, the accused committed the violation and is liable to pay the respondent, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, a monetary penalty of $3,000 within thirty (30) days (reduced from $6,000). |

||||||||||

|

2013 CART 42 |

Finley Transport Limited v. Canada (CFIA) |

14888 |

Y |

Y |

BLR |

August 5, afternoon 205 hogs loaded at Petrolia ON to Toronto ON slaughterhouse 278 km, at 300C; 3 dead on arrival one live unable to stand, dead in three different compartments. Pigs in respiratory distress, panting with oral froth. Recorded compartment floor space, pig weight not available assumed 230lb (105 kg). The 6 central compartments in the potbelly area of the trailer were loaded at 242 kgm-2. |

140(2) |

Finley did not adjust the number of pigs/compartments in response to the hot ambient temperatures. Ruled death was from heat exhaustion and death of this type is significantly foreseeable. | Notice upheld: Defence claimed preexisting heart conditions as cause of death. The Tribunal established, on the balance of probabilities, that the three hogs in question died from heat exhaustion due to overcrowding and orders t pay the Agency a monetary penalty of $6,000 within thirty (30) days |

||||||||||

| 2014 CART 33 |

Western Commercial Carriers Ltd. v. Canada (CFIA) |

8867 | Y | Y | DB | On July 1 the appellant transported 270, 113 kg pigs (best weather capacity of trailer though to be 280 pigs) in the early morning that day in Falher, AB and then driving the to Langley, BC (1,266 km). He arrived in Langley very early in the morning of July 2, 2013. At 07:00 that morning, as the pigs were unloaded at the slaughterhouse, 30 pigs were DOA and 1 distressed pig killed at unloading. |

140(1) | Did not reduce number loaded to 75% of his best weather load. Eight of the 12 compartments of the truck had dead hogs, with 4 compartments having 5 DOAs, no clustering within a compartment. Average floor pressure across 12 compartments was 251kgm-2 of live pig at loading. |

Notice upheld: On a balance of probabilities, the applicant, committed the alleged violation, and orders it to pay to the respondent, the amount of $6,000.00 within 30 days. |

||||||||||

|

2016 CART 07 |

TransVol Ltée v. Canada (Minister of |

2827 |

N |

N |

DB |

March 8 and 9 the appellant a commercial broiler chicken catching company loaded 7,340 birds into 734 cages, 10 birds each and 14 additional cages on the truckload left empty. The load arrived at slaughter in slightly more than |

140(1) |

TransVol does not contest the fact that the 20-bird cage was found on a truck, but rather it alleges that the particular cage in question was not filled or |

Notice upheld: On a balance of probabilities the applicant, TransVol Ltée., committed the alleged violation, and ordered it to pay, |

||||||||||

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) | 1 hour. Upon arrival officials found 48 dead chickens and one cage containing 20 chickens with 6 dead. Only the one cage was considered overcrowded. | loaded onto the truck by its employees. It is impossible to cram 20 chickens weighing 2.37 kg into the type of cage used in this case; and some of the chickens must have been culls and weighed far less than the average 2.37 kg. |

the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, a monetary penalty in the amount of $7,800.00 within 30 days |

||||||||||||||||

| 2016 CART 27 |

Transport Robert Laplante & Fils Inc. v. Canada (CFIA) |

3696 | Y | N | DB |

On May 17, the applicant transported 237 pigs for 3 hours from farm to slaughter. Due to a miscalculation, he believed he had only loaded 232 pigs. On arrival 2 pigs were found DOA and 2 further pigs were stressed. |

140(2) | No numerical evidence, nor location of dead and compromised pigs was contained in the decision. | Notice upheld: On a balance of probabilities, the applicant, committed the alleged violation, and orders it to pay to the respondent, the amount of $6,600.00 within 30 days. |

||||||||||

| 2017 CART 16 |

Transport Eugène Nadeau v Canada (CFIA) |

4559 | Y | N | DB |

On May 14, an unusually hot day high 27.7 oC, the applicant transported 180 pigs coming from two barns about 70 km apart to the abattoir taking 9 hours (mechanical failure on road), arriving on May 15. At unloading 10 DOA on top deck, some of the surviving pigs appeared to be in distress. |

140(2) |

At the time of the incident the trailer compartments were measured and compared to the code maximum. No numerical evidence was recorded in the decision. |

Notice upheld: On a balance of probabilities, Transport Eugène Nadeau inc., committed the alleged violation. Ordered to pay the monetary penalty in the amount of $7,800.00 within 30 days. |

||||||||||

| 2021 CART 16 |

C.I. Hishon Transport Inc. v CFIA |

3251 | Y | Y | LB |

On July 13, 211 hogs weighing 125 kg were loaded into a trailer from three different farms located in relative proximity to each other in western Ontario. The load then made its 13-hour journey of about 725 km to the slaughterhouse facility in Saint-Esprit, Quebec. On arrival there were 7 dead and 2 in respiratory distress. |

140(2) |

Dead and compromised pigs were all confined to the rear compartment loaded at 334 kgm-2. With 7 pigs dead the floor pressure was reduced to 267 kgm-2 and 2 additional pigs were dying. |

Notice upheld: On a balance of probabilities The CFIA has demonstrated a causal link between Hishon Transport and the transport, the crowding, the actual injury and undue suffering confirmed the penalty in the amount of $7,800.00. |

||||||||||

|

2023 CART 11 |

Atkinson v CFIA |

4010 | Y | Y | MR | Brandon Manitoba 328 sheep to Slaughter in Ontario (no destination reported) three animals with injuries, each in separate compartments: a dead lamb, a downed cull ewe that was subsequently euthanized and a dead newborn lamb. |

148(1) |

Truckside calculations of floor pressure were presented as evidence. Inspectors were using transport Code of Practice standard, that evidence was not documented in the decision. Dead ewe was old and emaciated. |

Quashed - the Agency did not prove on the balance of probabilities overcrowding caused injury or undue suffering to the dead lamb or the downed cull ewe. |

||||||||||

| 2023 CART 20 |

Brussels Transport Ltd. v CFIA |

4482 |

Y |

Y |

PLF |

Denfield ON to Saint-Espirit PQ, 772 kilometers in 8.5 hours at 24-30oC. Of 170, 130 kg market hogs, five were found dead in 2 different compartments upon their arrival at slaughter: 3 of 24 (A) and 2 of 18(B). Other animals were observed in respiratory distress upon arrival. This federal slaughter facility documents and investigates loads with 3 or more DOA. |

148(1) |

The code requires reduction in crowding by 25% in hot weather. In Compartment A loaded at 238 kgm- 2 3 of 24 died; Compartment B, loaded at 314 kgm-2 , 2 of 18 died. The weather warrants a 25% reduction in floor pressure as recommended by the Code. |

Notice upheld. Brussels failed to reduce the density of hogs in two compartments by 25% in response to the hot, humid weather. Maximum loading pressure of market pigs in summer weather is 3/4 of 287 kgm-2 is 215 kgm-2 both compartments were overloaded, penalty of $13,000.00 confirmed. |

||||||||||

|

2024 CART 06 |

1230890 Ontario Limited v CFIA |

1993 |

Y |

Y |

EC |

Appellant confined 167, 128 kg, market hogs near Kerwood, ON, and transported them to Breslau, ON, 156 km at 270C, 1hr 29 min. Dead pigs were identified in 3 compartments. |

148(1) |

Adopted Ontario Pork recommendation that for ambient temperature from 240C to 280C reduce load by 15%. Tribunal compared the 10 compartments to the standing room only 287kgm-2. Compartments ranged from 103 to 245kgm-2. The most crowded compartment has reduced floor pressure by 14.6% and contained no dead pigs. |

Quashed - The Notice and its penalty of $10,000.00 are cancelled. Death by hyperthermia could not have been prevented by decreasing the crowding. Author Note: There is no ambient temperature where the transport of pigs is prohibited in Canada. |

||||||||||

| 2024 CART 17 |

Earl MacDonald and Son Transport Limited v CFIA |

3722 | Y | Y | GP | On August 10, 171 pigs were loaded and transported at 26-28 0C (840 km) in a triple axle potbelly trailer from Thamesville ON to Saint-Espirit PQ. In the rear compartment, 3 of 27 pigs loaded were dead on arrival. Some pigs were panting on arrival. but had no other abnormalities (hernia, lameness, etc.) and were placed in a pen to cool off under showers provided for this purpose. |

148(1) | Facts: 27 pigs. average 121 kg loaded in a compartment of 12.65 m2 a floor pressure of 258.3 kgm-2. Accepted maximum allowable floor pressure in standing room only pigs, to be 287 kgm-2. The Ontario Pork guide requires reduction by 15% in hot weather, or a maximum floor pressure of 244 kgm-2. The compartment was overloaded by 3 pigs. | Notice upheld: Violation occurred at the time of loading and did not require the death of pigs. Confirm the administrative monetary penalty provided for in Notice of Violation in the amount of $10,000. |

||||||||||

| 2024 CART 20 |

Vernla Livestock Inc. v CFIA |

2292 |

Y |

N |

PLF |

Two incidents where market pigs loaded 205 hogs on the 30th of Dec 2 pigs stressed and killed on arrival, and 260 hogs on 18th Jan 3 hogs DOA, 2 further hogs, were non-ambulatory on arrival and euthanized. First appeal where individual hog weight was estimated by the difference between loaded and empty trailer weight. |

148(1) |

Due to the number of animals in the container, an animal was likely to suffer, sustain an injury or die. This case is based on the likelihood of a future event. No floor pressure information was presented in the decision although CFIA calculations of floor pressure were accepted in evidence. |

Quashed: The Agency has the burden of proof. The Agency has not convinced me on a balance of probabilities that it was likely that an animal would suffer, sustain an injury or die due to the number of animals in the container. Penalty of $13,000.00 was cancelled. |

||||||||||

|

2024 CART 27 |

1230890 Ontario Limited v CFIA |

2487 |

Y |

Y |

MR |

On January 28, the Applicant loaded 270, 135 kg, market hogs at a farm and transported them to an abattoir. Eight compartments held 30 hogs each and 2 compartments held 15 hogs. The load arrived with 7 dead hogs and 3 non- ambulatory hogs distributed in 6 compartments. At unloading pigs were panting, an unusual presentation in winter. |

148(2) |

Due to the number of animals in the container, an animal was likely to suffer, sustain an injury or die. This case is based on the likelihood of a future event. It is not “outcome-based” as argued by the Agency. No floor pressure information was presented in the decision although CFIA calculations of floor pressure were accepted in evidence. |

Quashed: The Agency has the burden of proof. The Agency has not convinced me on a balance of probabilities that it was likely that an animal would suffer, sustain an injury or die due to the number of animals in the container. Penalty of $13,000.00 was cancelled. |

||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).