Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Research Problem

3. Methods - Data Sources

- -

- annual number of Karkonosze Mts National Park entrance tickets sold at the toll booths;

- -

- number of overnight stays based on the amount of local fees paid to the Town Hall of Szklarska Poręba;

- -

- number of tourists visiting the Tourist Information;

- -

- number of passengers entering Szrenica in the summer and winter seasons.

4. Study Area

5. Results

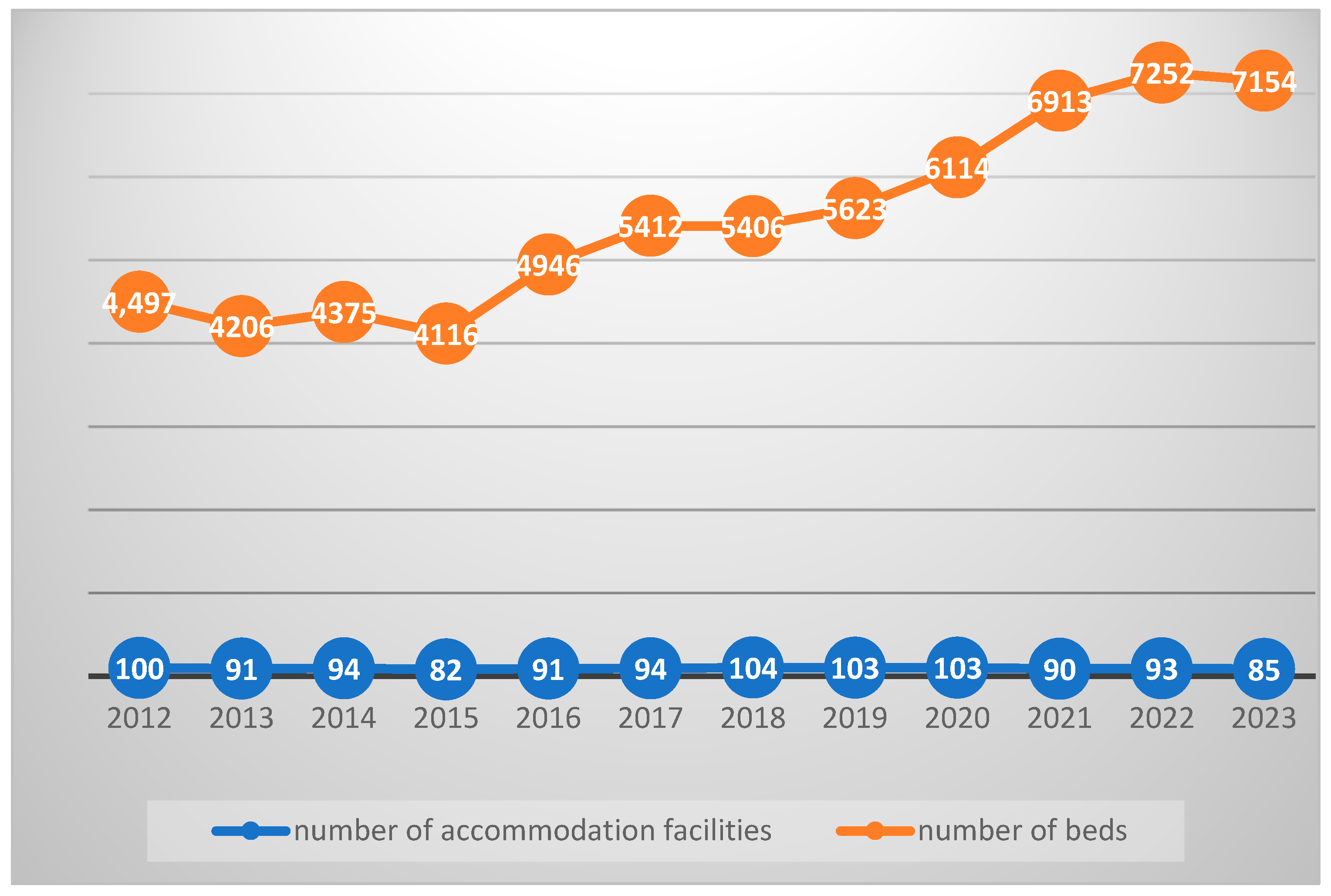

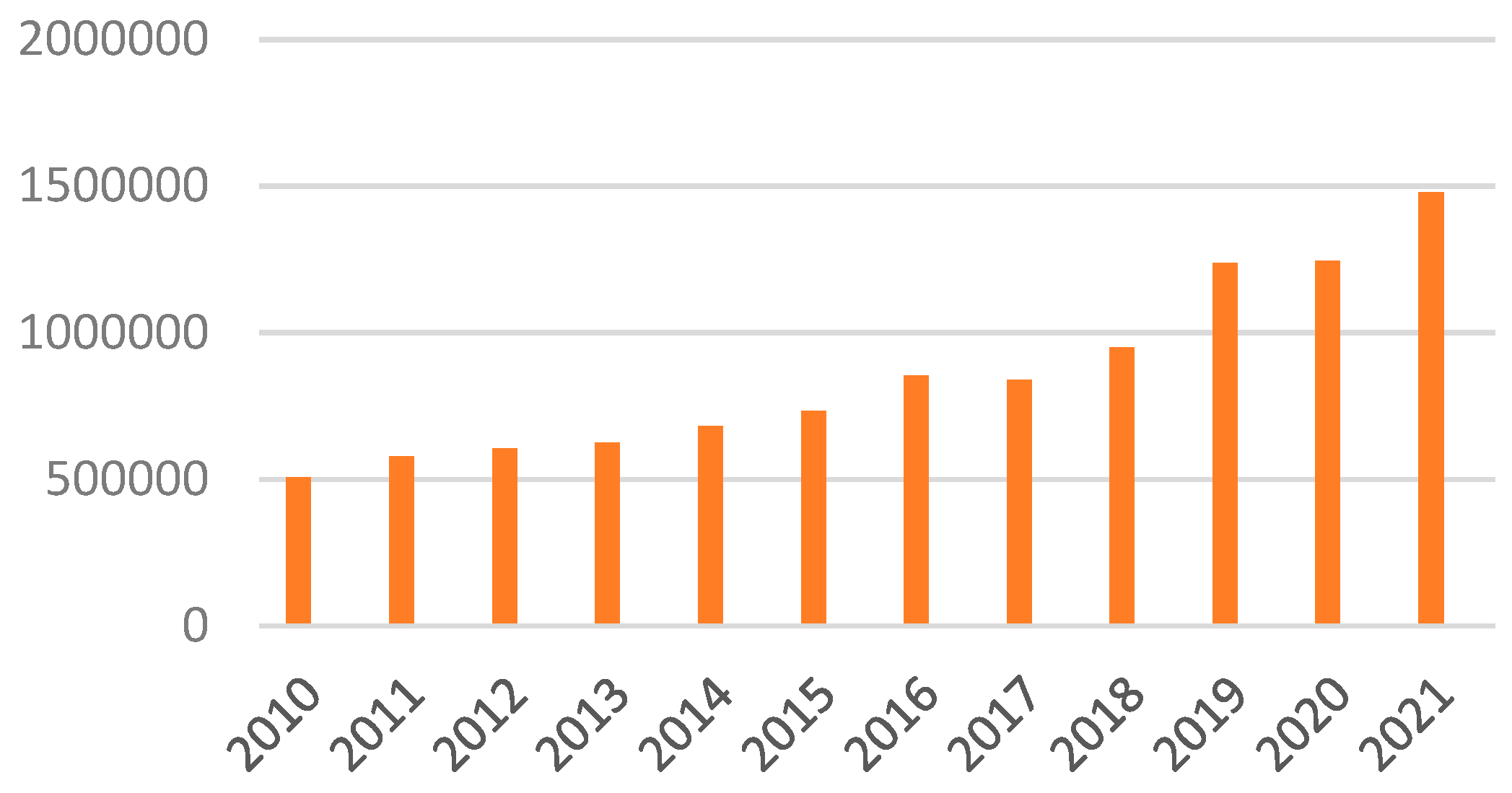

5.1. Tourism Development in Szklarska Poręba Community

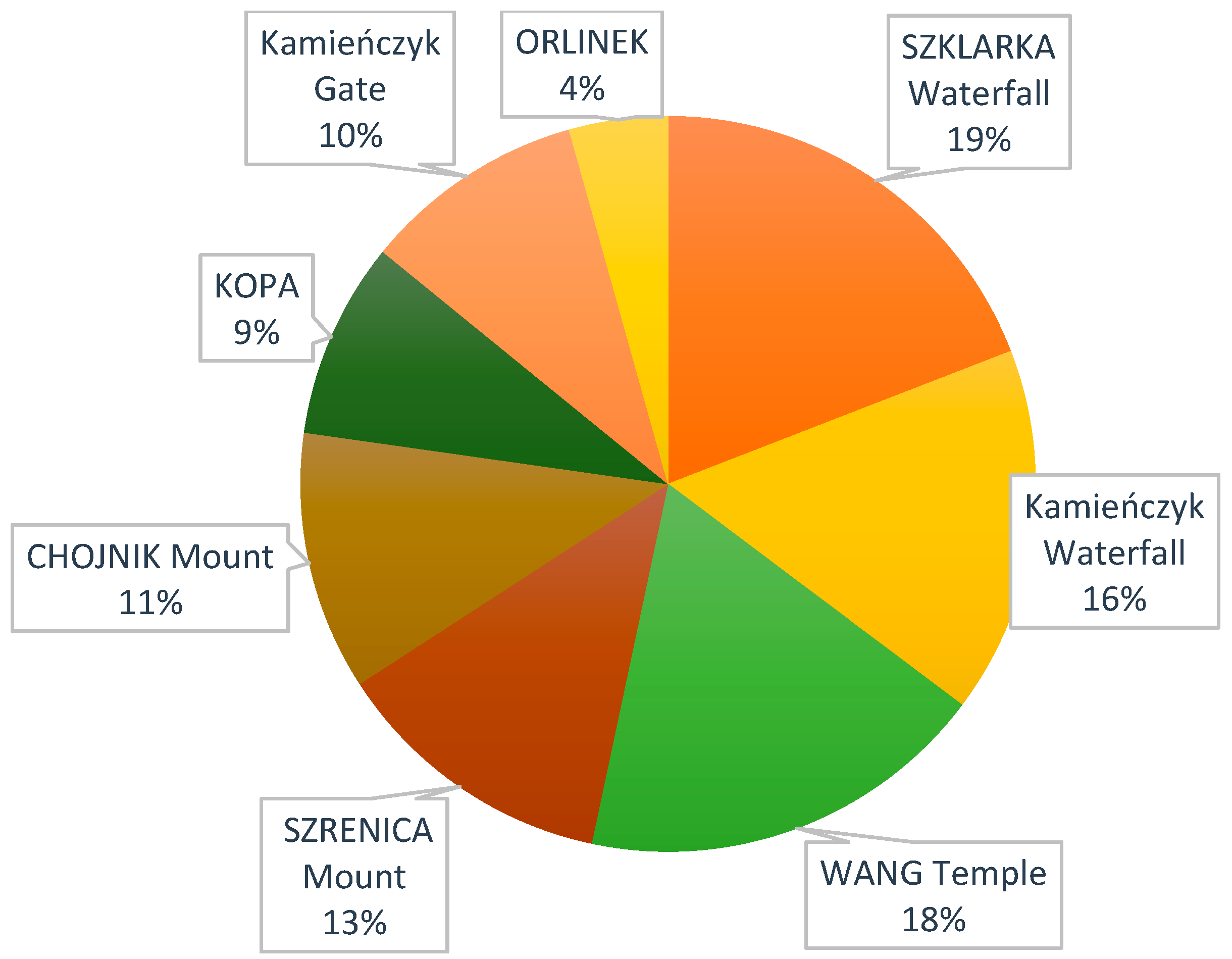

5.2. Tourism Development in Karkonosze Mts National Park

6. Conclusions and Implications

- -

- limit the number of tourists who can enter the protected area each day through a given ticket office and in the strict protection area, especially in the neighbourhood tourist hostel, attention should be paid to waste disposal,

- -

- place information boards along the hiking trails, highlighting the importance of the environmental and cultural values of the park,

- -

- secure tourist trails against their trampling and widening by tourists,

- -

- create a plan for making the area of the park and its surroundings accessible, so that its findings can be transferred to local planning. Plans for making the areas of the Karkonosze Mts National Park accessible should be created with the cooperation of all stakeholders: tourism organisers, local community and naturalists/ecologists.

- -

- improve public transport and cycling by launching additional public transport and the creation of bicycle routes to nearby towns; this can reduce traffic jams in the city, exhaust emissions and noise from private cars of tourists

- -

- introduce high parking fees in the city centre

- -

- promote nearby resorts and towns and encourage visits outside the high season (peak summer season and peak winter season) through the development of resort and spa facilities; promote ecotourism and the creation of unique tourism products related to the culture and folklore of the region, implemented in Szklarska Poręba and surrounding towns.

References

- Durydiwka M. 2009. Ruch turystyczny – z centrum ku peryferiom. Prace i Studia Geograficzne, 42: 59-71.

- Weaver D. B. 2001. Ecotourism in the context of other tourism types. [in]: D. B. Weaver (ed), The Encyclopedia of Ecotourism, CABI Publishing, new York, pp. 73-83.

- Peeters P., Góssling S., Klijs J., Milano C., Novelli M., Postma A. 2018. Research for TRAN Committee — Overtourism: impact and possible policy responses. European Parliament, Poli cy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies. Brussels.

- Koens K., Postma A., Papp B., Yeoman I. 2018. “Overtourism”? – Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions World Tourism Organization. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł J., Zmyślony P. 2017. Turystyka miejska jako źródło protestów społecznych: przykłady Wenecji i Barcelony. Turystyka Kulturowa, 2, ss. 7-36.

- UNWTO 2018. Overtourism? – Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions, Executive Summary. Madrid. [CrossRef]

- Koens K., Postma A., Papp B. 2018. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability, 20, 4384. [CrossRef]

- Doxey G.V. 1975. A Causation theory of visitor-resident irritants, methodology and research in-ferences: The impact of tourism. [in]: Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings of the Travel Re search Association (pp. 195-198). San Diego: TTRA.

- Butler R. W. 1980. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. The Canadian Geographer 24 (1), pp. 5-12. [CrossRef]

- Milano C, Cheer J. M., Novelli M. 2018. Overtourism: a growing global problem. https://tJieconversationxom/overtourism-a-growing-global-problem-100029.

- Krippendorf J. 1987. The Holiday Makers. Understanding the impact of Leisure and Travel. Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford.

- Gursoy D.; Rutherford, D.G. 2004. Host attitudes toward tourism: An Improved Structural Model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 37, 495-516.

- Sharpley R. 2014. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag., 42,37-49.

- Boissevain J. (ed) 1996.Coping with Tourists: European Reactions to Mass Tourism. Barghahn Books, New York and Oxford.

- Tyler D., Guerrier Y., Robertson M. 1998. Managing tourism in cities: policy, process and practice . John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

- Bosselman F., Petersonjh C., McCarthy C. 1999. Managing tourism growth: issues and applications. Island Press Washington.

- Goodwin H. 2017. The challenge of overtourism. Responsible Tourism Partnership Worlang Pa per 4, 1.

- Milano C, Novelli M.. Cheer J.M. 2019. Overtourism and Tourismphobia: A Journey Through Four Decades of Tourism Developrnent, Planning and Local Concerns. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(4), pp. 353-357.

- Mihalic T. 2020. Conceptualising overtourism: A sustainability approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 103025. [CrossRef]

- Lidzbarski T. 2020. Overtourism poza granicami sukcesu. Funkcje i dysfunkcje turystyki na greckiej wyspie Zakhyntos. Turystyka Kulturowa, 4: 7-46.

- Saepórsdóttir A.D., Hall, C.M., Wendt M. 2020a. From boiling to frozen? The rise and fali of international tourism to iceland in the era of overtourism. Environments 2020, 7, 59.

- Saepórsdóttir A.D., Hall C.M., Wendt M. 2020b. Overtourism in Iceland: Fantasy or reality? Sustainability, 72, 7375.

- Weber F., Stettler J., Priskin J., Rosenberg-Taufer B., Ponnapureddy S., Fux S., Camp M, Barth M. 2017. Tourism destinations under pressure. Challenges and innovative solutions, Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts-Institute of Tourism ITW, Lucerna.

- Mika M. 2008. Przemiany pod wpływem turystyki na obszarach recepcji turystycznej, [w:] W. Kurek (red.), Turystyka, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa, ss. 406-482.

- Russo A.P. 2002. The “vicious circle” of tourism development in heritage cities. Annals of Tourism Research, 20, 1, pp. 165-182.

- Adie B.A., Falk M., Savioli M. 2020. Overtourism as a perceived threat to cultural heritage in Eu rope. Current Issues in Tourism 23(14), pp. 1737-1741. [CrossRef]

- Freytag T, Bauder M. 2018. Bottom-up touristification and urban transformations in Paris. Tourism Geographies, 20 (3), pp. 443-460. [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł J. 2018. Koncepcja gentryfikacji turystycznej i jej współczesne rozumienie. Pra ce Geograficzne, 154, ss. 35-54. [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth D., Weisler A. 2018. Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing econ omy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50(6), pp. 1147-1170. [CrossRef]

- Kruczek Z. 2018. Turyści vs. mieszkańcy. Wpływ nadmiernej frekwencji turystów na proces gentry fikacji miast historycznych na przykładzie Krakowa. Turystyka Kulturowa, 3, ss. 29-41.

- Kurek W., Mika M. 20089. Miejscowości turystyczne w dobie konkurencji (na przykładzie Polskich Karpat, [w:] G. Gołembski (red.), Turystyka jako czynnik wzrostu konkurencyjności regionów w dobie globalizacji. Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej Poznań, 219–228.

- Niezgoda A. 2006. Obszar recepcji turystycznej w warunkach rozwoju zrównoważonego. Akademia Ekonomiczna w Poznaniu, Prace Habilitacyjne, 24.

- Andereck K.L., Nyaupane G.P. 2011. Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. Travel Res., 50, 248-260.

- Andereck K.L., Valentine K.M., Vogt C.A., Knopf R.C. 2007. A Cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. Sustain. Tour.,15,483-502.

- Higgins-Desbiolles F., Camicelli S., Królikowski C., Wijesinghe G., Boluk K. 2019. Degrowing tourism: Rethinking tourism. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27,1926-1944.

- Oklevik O., Góssling S., Hall C.M., Steen Jacobsen J.K., Gratte L.R., McCabe S. 2019. Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: A case study of activities in Fjord Norway. Sustain. Tour., 27,1804-1824.

- Pecot M., Ricaurte-Quijano C. 2019. “Todos a Galapagos?”: Overtourism in wilderness areas of the global south. In: Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; Milano, C, Cheer J.M., Novelli M. (Eds.), CABI: Cambridge, UK, pp. 70-85.

- Lankford S.V., Pfister R.E., Knowles J., Williams A. 2003. An exploratory study of the impacts of tourism on resident outdoor recreation experiences. Park Recreat. Adm.,27, 30-49.

- Frick J., Degenhardt B., Buchecker M. 2007. Predicting local residents' use of nearby outdoor recreation areas through quality perceptions and recreational expectations. For. Snow Landsc. Res., 81, 31-41.

- Luck M., Seeler S. 2021. Understanding domestic tourists to support COVID-19 recovery strategies - The case of Aotearoa New Zealand. Responsible Tour. Manag. 2021, 7,10-20.

- Wendt M., Saepórsdóttir A.D., Waage E.R.H. 2022. A Break from Overtourism: Domestic Tourists Reclaiming Nature during the CPOVID-19 Pandemic. Tourism and Hospitality, 3: 788-802. [CrossRef]

- Capocchi A., Valione C. Pierotti M., Amaduzzi A. 2019. Overtourism: A Literature Review to Assess Implications and Future Perspectives. Sustainablity, 11 (12), pp. 3303. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gil S., Coca-Stefaniak J.A. 2020. Overtourism and the sharing economy: Tourism cities at a crossroads. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 6 (1), pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Kruczek Z. 2019. Ways to Counteract theNegative Effects of Overtourism at Tourist Attractions and Destinations. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Sklodowska. Sectio B, 74, pp. 45-57. [CrossRef]

- Pinke-Sziva I., Smith M., Olt G., Berezvai Z. 2019. Overtourism and the night-time economy: A case study of Budapest. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(1), pp. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Szromek A.R., Kruczek Z., Walas B. 2020. The Attitude of Tourist Destination Residents towards the Effects of Overtourism – Kraków Case Study. Sustainability 12 (1), p. 228. [CrossRef]

- Zmyślony P, Kowalczyk-Anioł J.. Dembińska M. 2020. Deconstructing the Overtourism-Related Social Conflicts. Sustainability, 12 (4), p. 1695. [CrossRef]

- Jover J., Diaz-Parra I. 2020. Who is the city for? Overtourism, lifestyle migration and social sustain-ability. Tourism Geographies, 1-24.

- Kacprzak K. 2021. Overtourism w przestrzeni turystycznej Pragi w opinii zagranicznych rezydentów. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Lublin, B, 76, pp. 29-44.

- Miazek P. 2020. Przyczyny zróżnicowania ruchu turystycznego w polskich parkach narodowych. Turyzm, 30, 1: 73-86.

- Kruczek Z.. Szromek A.R. 2020. The Identification of Values in Business Models of Tourism Enter prises in the Context of the Phenomenon of Overtourism. Sustainability, 12(4), p. 1457. [CrossRef]

- Tracz M., Bajgier-Kowalska M.. Wojtowicz B. 2019. Transformation in the Tourist Services and their Impact on the Perception of Tourism by the Residents of Kraków (Poland). Studies of the Industrial Geography Commission of the Polish Geographical Society, 35(1), pp. 164-178. [CrossRef]

- Zmyślony R, Kowalczyk-Anioł J. 2019. Urban tourism hypertrophy: Who should deal with it? The case of Kraków (Poland). International Journal of Tourism Cities 5(2), pp. 247-269.

- Kazimierczak M., Malchrowicz-Mośko E. 2021. Overtourism w etycznej perspektywie. Turystyka Kulturowa, 1(118), ss. 38-55.

- Dielemans J. 2011. Witajcie w raju. Reportaż o przemyśle turystycznym. Wydawnictwo Czarne, Wołowiec ( Välkommen till Paradiset: reportage om turistindustrin).

- Kowalczyk-Anioł J. 2019. Hipertrofia turystyki miejskiej – geneza i istota zjawiska. Konwersato rium Wiedzy o Mieście, 32 (4), ss. 7-18. [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Garcia F., Cortes-Macias R., Parzych K. 2021. Tourism impacts, tourism-phobia and gentrification in historie centers: The cases of Malaga (Spain) and Gdańsk (Poland). Sustainability (Switzerland), 13 (1) pp. 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Turner L., Ash J. 1975. The Golden Hordes. International Tourism and the Pleasure Peripher. Constable, Londyn.

- Nash D. 1978. Tourism as a form of imperialism. [in]: V. L. Smith (ed), Host and guest. The Antropology of Tourism, Basil Bleckwell, Oxford.

- Garrod B. 2003. Managing visitor impacts, [in:] Managing Visitor Attractions. New Directions, A. Fyall, B. Garrod, A. Leask (eds.), Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp. 124-139 (cyt za: M. Nowacki, 2014, Zarządzanie atrakcjami turystycznymi w świetle aktualnych badań. Folia Turistica, 31.).

- Almeidaa J., Costa C., Nunes da Silva F. 2017. A framework for conflict analysis in spatial planning for tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 24, pp. 94-106.

- Dredge D. 2010. Place change and tourism development conflict: Evaluating public interest. Tourism Management, 31(1), pp. 104-112.

- Macias Rodriguez D., Del Espino Hidalgo B., Perez Cano M.T. 2020. Destination central dis-trict: The representation of the conflict. International Journal of Tourism Cities.

- Atejlevic I. 2020. Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re)generating the potential 'new normal’. Tourism Geographies, 22 (3), pp. 467-475. [CrossRef]

- Chaney D., Seraphin H. 2020. Covid-19 crisis as an unexpected opportunity to adopt radical changes to tackle overtourism. Anatolia. [CrossRef]

- UNWTO 2021 . Covid-19 and tourism. 2020: A year in review. www.unwto.org/covid-19-and-tourism-2020.

- Higgins-Desbiolles F. 2021. The “war over tourism”: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tour ism academy after COVlD-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29 (4), pp. 551-569. [CrossRef]

- Góssling, S.. Scott, D.. Hall. C.M. 2020. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVlD-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29 (1) pp. 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Smith M.K., Sziva L.R, Olt G. 2019. Overtourism and resident resistance in Budapest. Tour. Plan. Dev.,76,376-392.

- Visentin F., Bertocchi D. 2019. Venice: An analysis of tourism excesses in an overtourism icon. In: Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; Milano, C, Cheer J.M., Novelli M. (Eds.), CABI: Cambridge, UK, pp. 18-38.

- Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z dnia 9 listopada 2015 r. w sprawie Karkonoskiego Parku Narodowego (Dz. U. poz. 2002); wcześniej wydane akty prawne dotyczące Karkonoskiego Parku Narodowego (Dz. U. z 1959 r. Nr 17, poz. 90 oraz z 1996 r. Nr 64, poz. 306) zostały uchylone. [Ordinance of the Council of Ministers of 9 November 2015 on the Karkonosze National Park (Dz. U. pos. 2002); previously issued legal acts concerning the Karkonosze National Park (Dz. U. of 1959 No. 17, item 90 and of 1996 No. 64, item 306) have been repealed].

- Partyka J. 2010. Ruch turystyczny w polskich parkach narodowych. Folia Turistica – Turystyka i ekologia, 22: 9-25.

- Dudek A., Kowalczyk A. 2003. Turystyka na obszarach chronionych – szanse i zagrożenia. Prace i studia geograficzne, 32: 117-140.

- Zarządzenie Ministra Klimatu z dnia 13 stycznia 2020 r. w sprawie zadań ochronnych dla Karkonoskiego Parku Narodowego na lata 2020-2021. Dz. Urzęd. Ministra Klimatu, poz. 3. [Order of the Minister of Climate of 13 January 2020 on the protective tasks for the Karkonoski National Park for 2020-2021. Dz. Official. Minister of Climate, item 3].

- Myga-Piątek U., Jankowski G. 2009. Wpływ turystyki na środowisko przyrodnicze i krajobraz kulturowy – analiza wybranych przykładów obszarów górskich. Problemy Ekologii Krajobrazu, 25: 27-38.

| year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tourists in general | 17 000 | 17 710 | 16 256 | 18 029 | 20 084 | 21 792 | 19 257 | 20 678 | 38 352 | 28 258 | 22 633 | 55 322 | 295 371 |

| foreign tourists | 6 956 | 6 897 | 6 864 | 6 829 | 6 703 | 6 651 | 6 681 | 6 611 | 6 633 | 5 968 | 5 873 | 5 872 | 78 538 |

| Month/year | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JANUARY | 65 027 | 71 201 | 73 639 | 61 391 |

| FEBRUARY | 67 953 | 62 739 | 72 262 | 70 832 |

| MARCH | 16 407 | 35 545 | 47 723 | 39 927 |

| APRIL | 2 788 | 32 585 | 62 158 | 76 949 |

| MAY | 54 147 | 93 299 | 120 096 | 128 528 |

| JUNE | 118 534 | 165 022 | 160 021 | 169 659 |

| JULY | 281 699 | 296 740 | 258 336 | 272 714 |

| AUGUST | 286 812 | 306 905 | 282 816 | 273 183 |

| SEPTEMBER | 187 544 | 201 703 | 146 667 | 201 149 |

| OCTOBER | 92 099 | 144 846 | 152 270 | 108 171 |

| NOVEMBER | 33 639 | 66 483 | 72 031 | 55 850 |

| DECEMBER | 38588 | 43 506 | 32 742 | 46 921 |

| TOTAL | 1 245 237 | 1 520 574 | 1 480 761 | 1 505 274 |

| Month/year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JANUARY | 2994 | 3325 | 3393 | 3682 | 6487 | 9514 | 7247 | 6356 |

| FEBRUARY | 2723 | 4464 | 6466 | 5350 | 3593 | 7413 | 3835 | 6916 |

| MARCH | 3092 | 2322 | 3242 | 2538 | 1646 | 3747 | 5921 | 3429 |

| APRIL | 1975 | 5627 | 4138 | 6337 | 0* | 593 | 351 | 2707 |

| MAY | 17461 | 12413 | 20076 | 14118 | 4172 | 7350 | 14847 | 19647 |

| JUNE | 11495 | 13789 | 16102 | 20881 | 14985 | 20621 | 20950 | 22472 |

| JULY | 24359 | 33950 | 34118 | 32795 | 4008 | 39831 | 35536 | 34365 |

| AUGUST | 42869 | 43375 | 39891 | 43608 | 40978 | 42407 | 40850 | 38231 |

| SEPTEMBER | 21601 | 16623 | 21106 | 19234 | 28715 | 29900 | 19622 | 33331 |

| OCTOBER | 8423 | 11500 | 11905 | 8988 | 11085 | 0 | 16708 | 10266 |

| NOVEMBER* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| DECEMBER | 2484 | 2548 | 2584 | 5499 | 1625 | 4202 | 4476 | no data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).