1. Introduction

Prevalence and incidence of type 1 diabetes increased significantly in recent years. In pediatric population in north-east Poland its incidence has increased from 19.48 up to 36.68/100,000 person/years from 2010 to 2022 [

1]. In Podkarpackie (Subcarpathian) Region in south-east Poland, where our study was conducted, number of people aged below 40 years, suffering from type 1 diabetes (T1D) exceeds 4.5 thousand (data obtained from regional branch of National Health Fund, unpublished). Therefore, the number of women with T1D in reproductive age also increased substantially. It translates into growing number of pregnancies in females with pregestational T1D, which became prevalent in one in every 275 pregnancies [

2,

3]. Despite continuous progress in the care of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D), pregnancy in such patients is still significant medical problem, responsible for an increased number of perinatal complications affecting both the fetus and the mother (miscarriage, perinatal death, congenital malformations, preterm birth, LGA, macrosomia) in comparison to the general pregnant population [

4,

5]. According to clinical practice recommendations of Diabetes Poland, pregnancy in women with type 1 diabetes should be planned to avoid unfavorable pregnancy outcomes both for the mother and the child, and it should be a part of standard diabetes care for women in reproductive age. Preconception care should include optimization of diabetes therapy, assessment of presence and treatment of possible diabetic complications (ophthalmological examination should be carried out at the stage of pregnancy planning, or at the latest in the first trimester of pregnancy), diabetes education, including dietary advise and assessment of thyroid function [

6].

A multicenter, international randomized controlled CONCEPTT trial was the first to prove that use of continuous glucose monitoring system (CGM) is associated with better glycemic control during pregnancy as well as with better pregnancy outcomes compared to self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) [

7]. Wider introduction of new technologies in diabetes care – continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) – insulin pumps and CGM systems, either intermittently scanned (isCGM) and real time (rtCGM) improved substantially metabolic control and pregnancy outcomes in women with pregestational T1D [

8,

9]. Created by the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity Foundation (GOCCF) program offers in several centers in Poland free use of insulin pumps and rtCGM system (SAP – sensor-augmented pump) with PLGS – predictive low-glucose suspend system from the preconception stage for women with T1D who are planning to become pregnant.

As it was mentioned earlier, pregnancy in women with T1D should be planned [

6]. Unfortunately, in a real life, number of unplanned pregnancies in this population is still too high. Interestingly, number of papers assessing impact of pregnancy planning on pregnancy outcomes is not high. Although their results were to some extent discordant, they indicated better glycemic control and better pregnancy outcomes, especially lower number of preterm deliveries in women who planned pregnancy compared to those who did not [

10,

11]. Therefore, we conducted retrospective, observational, single center study to analyze the impact of pregnancy planning on pregnancy outcomes in patients qualified to participation in a GOCCF program.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

Diabetic Outpatient Clinic at the University Clinical Hospital in Rzeszów is the only center which currently participates in the GOCCF program in the Subcarpathian region of Poland. From 2018 to March 2025, 102 women with T1D were enrolled to the GOCCF program. Four of them were excluded from the final analysis: two of them have not got T1D before pregnancy (they had diagnosed diabetes during gestation), one suffers from adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease), which had a major impact on insulin requirements, maternal weight gain and neonatal birth weight, and the last one had advanced diabetic complications at the time of conception with diabetic kidney disease in stage G4 which led to development of preeclampsia and finally pregnancy was prematurely terminated by cesarean section in 28th week and premature baby (birthweight 700 g) died after five days.

Among 98 women, aged 21-41 years, included into analysis, only 48 (49.0%) planned pregnancy and they were prepared for pregnancy in accordance with Diabetes Poland clinical practice recommendations, while in 50 cases (51.0%) pregnancy was unplanned. Many of women from both groups were referred from diabetes outpatient clinics in different parts of Subcarpathian region, and they were frequently not familiar with the use of the CSII and rtCGM. Therefore, they had to be trained how to use the equipment first, which took some 1-2 weeks up to initiation of CSII and rtCGM. This explains later initiation of CCSI in some women, despite their pregnancy was planned.

Baseline characteristics of study participants is presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Management of Diabetes

After qualification to GOCCF program, patients were trained by doctor and diabetic educator regarding use of SAP with PLGS system therapy, proper diet and physical activity during pregnancy. GOCCF secured the availability of personal insulin pumps MiniMed 640G and later also MiniMed 740G (Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA). During pregnancy patients were treated in accordance with current Diabetes Poland clinical practice recommendations with target HbA1c <6.5% (<48 mmol/mol) in the first trimester, and <6.0% (<42 mmol/mol) in subsequent trimesters, target range of CGM glucose values was 3.5–7.8 mmol/L (63–140 mg/dL) and TIR >70%, TAR <25% and TBR <4% with <1.0% of glucose level <3 mmol/L (54 mg/dl) [

6].

2.3. Analyzed Outcomes

Analyzed parameters included: age, diabetes duration, pregestational BMI, HbA1c, CGM parameters: TIR (time in range), TAR (time above range), TBR (time below range) and CV (coefficient variability), insulin requirement, maternal weight gain, miscarriage, preterm delivery, method of termination of pregnancy, congenital malformations and birthweight of newborns: normal weight, LGA or SGA (large or small for gestational age) and macrosomia (birthweight >4000 g).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot for Windows software, version 12.5 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). The nominal variables are presented as absolute and percentage frequencies. The normality of data distribution was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Differences between baseline and end-of-study values within groups were analyzed using a paired two-tailed Student’s t-test for dependent variables or by a Mann–Whitney rank sum test where appropriate, while differences between the groups using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for independent variables or by a Mann–Whitney rank sum test where appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 test with the Yates continuity correction applied. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Whole Group

After initiation of CSII + rtCGM therapy with PLGS system, glycemic control of diabetes (HbA1c, TIR and TAR) improved substantially (

Table 2), over 50% of women achieved HbA1c level <6.0% (<42.mmol/mol) in the second and third trimester, TIR >70% and TAR <25% was achieved respectively by 44 and 45 % of females. TBR <3.5 mmol/L (63 mg/dL), decreased significantly, especially time below <3 mmol/L (<54 mg/dL) fell from 2.0 ± 2.8 % to 1.3 ± 2.0 % (P=0.009).

3.1.1. Weight Gain and Birthweight

One of important problems in pregnancies in women with T1D is excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Mean weight gain in a whole group was 12.4 ± 4.7 kg. Higher than recommended weight gain for given pregestational BMI occurred in 29 women. In 51 cases it was within recommended range, while in 18 females weight gain was lower than recommended. In these groups proportion of LGA babies was significantly different: 48.3%, 21.6% and 27.8% respectively, P=0.043. Also mean birthweight of newborns was significantly different between these groups. It was highest in a group with excessive weight gain: 3824.1 ± 510.3 g vs. 3.481.5 ± 612.9 g (normal weight gain), P=0.024, and vs. 3333.9 ± 706.0 g (low weight gain), P=0.033.

According to the recommendations of the Polish Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians, after the 38th week of pregnancy in women with diabetes, an attempt should be made to induce labor, and if there is no progress in labor or other indications occur, the pregnancy should be terminated by caesarean section (CS) [

12]. In our study 87.8% of pregnancies were terminated by CS and decision on the method of termination of pregnancy was made by obstetricians. A total of 20 women experienced preterm birth. Macrosomia (birthweight >4000 g) occurred in 21 newborns and 30 babies (30.6%) were large for gestational age (LGA). None of newborns was small for gestational age (SGA). Congenital abnormalities occurred in 5 newborns: in 3 cases it was cardiomyopathy, in one case kidney agenesis and hypospadias in 1 male newborn.

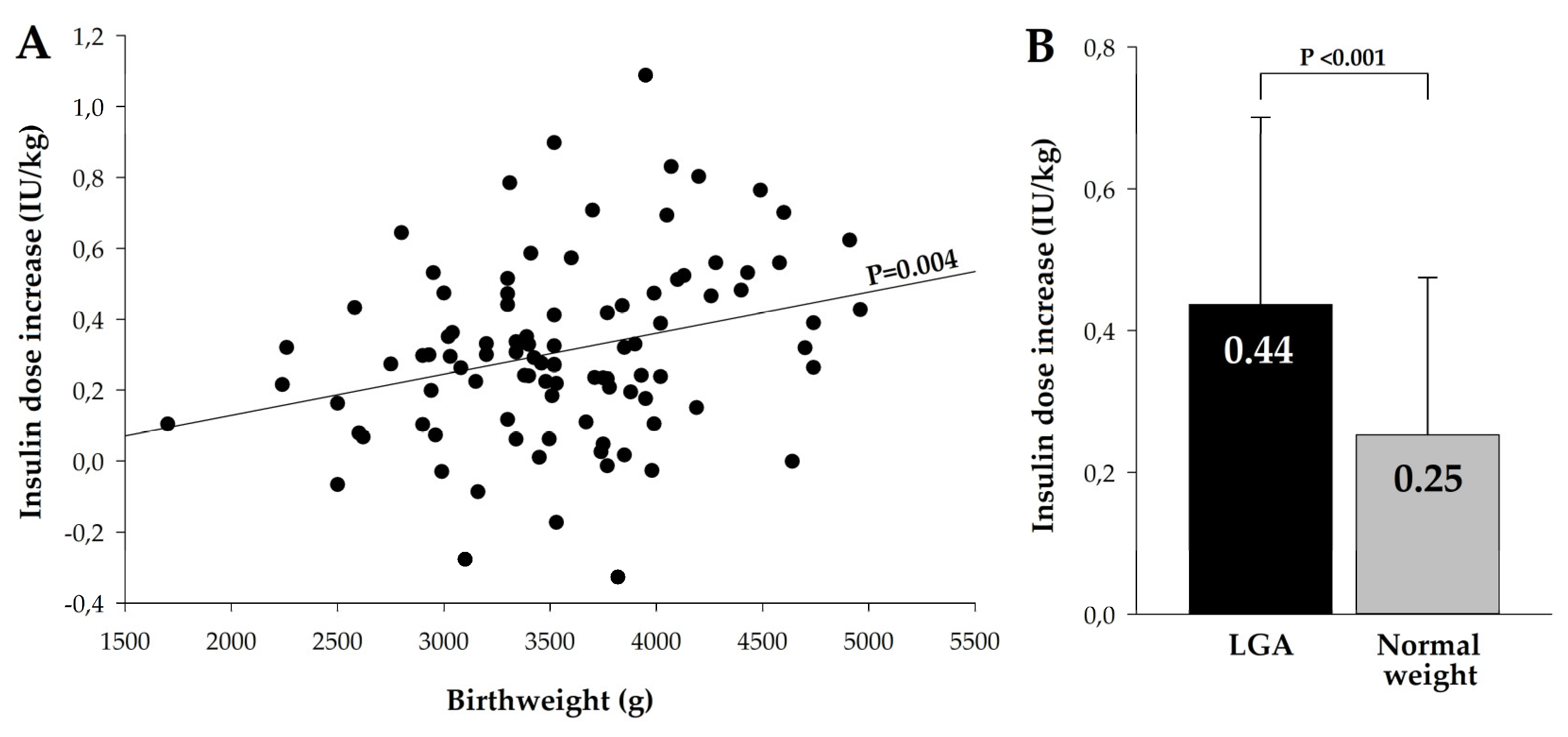

3.1.2. Insulin Dose

Mean total insulin dose increase was 33.2 ± 22.4 IU and the average increase in insulin dose per kg of body weight was 0.31 ± 0.25 IU/kg. Highest daily insulin dose increase was found in a group with the excessive weight gain, 44,6 ± 25.1 IU and it was significantly higher compared to group with normal weight gain, 29.9 ± 21.3 IU, P=0.004, and with low weight gain, 24.3 ± 12.3 IU, P=0.001. Rise in insulin dose per kg of body weight in these three groups was not significantly different: 0.39 ± 0.27 IU/kg, 0.27 ± 0.26 IU/kg and 0.29 ± 0.16 IU/kg, P=0.110. However, we found highly significant relationship between insulin dose per kg of body weight and birthweight of newborn (

Figure 1A), and in mothers who delivered LGA babies mean rise in insulin dose was 0.44 ± 0.26 IU/kg vs. 0.25 ± 0.22 IU/kg in women who delivered normal-weight newborns, P<0.001.

3.2. Planned vs. Unplanned Pregnancy

Among patients enrolled in GOCCF program, 48 women planned their pregnancy, while in 50 cases pregnancy was unplanned. Women who planned pregnancy had significantly lower HbA1c before gestation and they had earlier initiation of SAP with PLGS system therapy. No significant differences between the groups were seen regarding age (although it tended to be higher in the planning pregnancy group), T1D duration, pregestational BMI, use of CSII before gestation and White’s scale at baseline. (

Table 3).

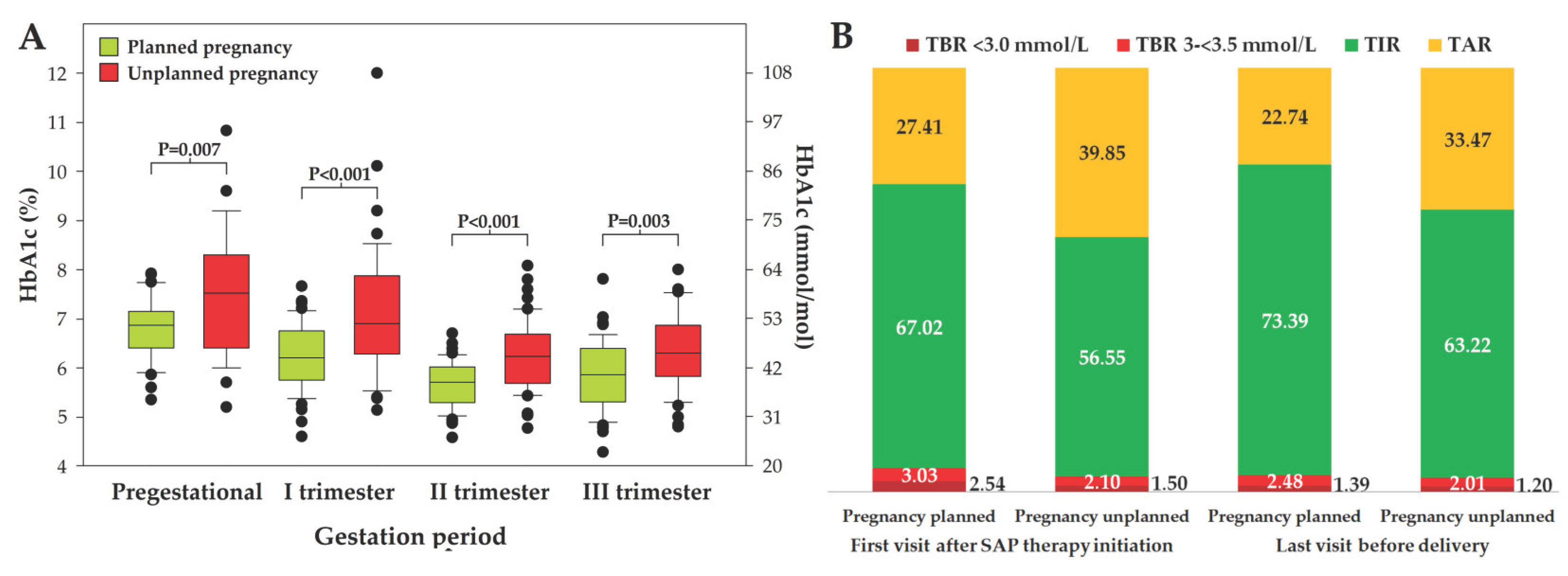

Figure 2.

HbA1c before pregnancy and in subsequent trimesters in women with planned and unplanned pregnancy (panel A) and CGM report presenting mean TIR, TAR and TBR in these groups of patients (Panel B).

Figure 2.

HbA1c before pregnancy and in subsequent trimesters in women with planned and unplanned pregnancy (panel A) and CGM report presenting mean TIR, TAR and TBR in these groups of patients (Panel B).

3.2.1. Maternal Outcomes

Women who planned pregnancy had significantly better diabetes control measured by HbA1c either before gestation and throughout the entire pregnancy compared to females who did not plan pregnancy (

Figure 2, panel A). They also had significantly higher mean TIR and lower TAR at the beginning of SAP with PLGS system therapy, which was maintained throughout pregnancy (P<0.001 in each case), while no difference was found regarding TBR (

Figure 2, panel B). However, time spent in hypoglycemia.

A proportion of women who had recommended metabolic control of diabetes before pregnancy and/or achieved and maintained recommended values of HbA1c at each pregnancy trimester, number and proportion of females who achieved TIR >70% and TAR <25% is presented in

Table 4. Number of women who spent more than 1% of time below 54 mg/dl was similar: 13 (27.1%) and 14 (28.0%) in planned and unplanned pregnancy respectively, P=0.901. Women who planned pregnancy had lower coefficient variability (CV) compared to females non-planning gestation, 29.4 ± 5.5 vs. 31.9 ± 5.1, P=0.030.

We did not find significant differences regarding weight gain and insulin dose increase, neither total nor IU per kg of body weight, between women who planned and those who did not plan pregnancy.

3.2.2. Neonatal Outcomes

The most frequent adverse pregnancy outcomes affecting offspring is excessive birth weight manifested as macrosomia and LGA. In our study we did not find differences in these outcomes between women who planned and who did not plan gestation - macrosomia was present respectively in 11 and 10 neonates (22.9 vs. 20.0%, P=0.916), number of LGA babies was 14 and 16 respectively (29.2% vs. 32.0%, P=0.932). Also birth weight was not significantly different: 3628 ± 555 g vs. 3486 ± 683, P=0.261. However, number of preterm deliveries was significantly lower in women who planned pregnancy, n=5 (10.4%) compared to those who did not plan pregnancy, n=15 (30.0%), P=0.031. Also mean duration of pregnancy was significantly different: 37.8 ± 0.9 vs. 36.9 ± 1.8 weeks respectively, P=0.039. Congenital abnormalities were rare and they were present in 1 neonate from a group planning pregnancy and in 4 neonates in a group non-planning gestation.

4. Discussion

Despite continuous progress in type 1 diabetes treatment, pregnancy in women with T1D still remains a challenge. Number of adverse pregnancy outcomes, either maternal as well as neonatal (preeclampsia, preterm delivery, miscarriage, congenital defects, LGA neonates etc.), remains high compared to non-diabetic women [

13]. Achievement and maintenance of good metabolic control, especially in the first weeks of pregnancy is of utmost importance to improve pregnancy outcomes [

14]. The Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity Foundation program several years ago initiated support for pregnant women with type 1 diabetes offering to them use of personal insulin pumps and rtCGM with PLGS system to improve efficacy and increase safety of treatment by avoiding hypoglycemic episodes [

15]. Diabetic Outpatient Clinic at the University Clinical Hospital in Rzeszów participates in this program from 2018. Up to March 2025 SAP with PLGS system therapy was used in 102 pregnant women with T1D.

In our retrospective, single center study we were aimed to analyze whether pregnancy planning and using CSII and rtCGM with PLGS system from the very beginning of gestation or from pregestational period has an impact on pregnancy outcomes in T1D. Number of studies addressing this problem is not large. In one of the earliest studies, also conducted in Poland, pregnancy planning was associated with better glycemic control during pregnancy irrespective of method of insulin therapy – CSII vs. MDI (multiple daily insulin injections). In this study no CGM systems were used. Despite higher number of neonatal complications in a group with unplanned pregnancy, the difference did not reach statistical significancy. The authors also noted significantly larger weight gain in a group using CSII compared to MDI group [

16]. Inversely to our study and many other papers, in the Finnish study conducted in North Karelia pregnancy planning was associated with several benefits – apart of better metabolic control also the number of congenital anomalies was lower and less cesarean sections were performed in the planning pregnancy group. In this study no CSII and/or CGM were used [

17]. Authors of the one of a recent studies conducted in Italy and France, similarly to our observations, found that pregnancy planning was associated with lower HbA1c levels throughout entire gestation period compared to unplanned pregnancies. Also, like in our study, number of preterm deliveries was significantly lower in planned pregnancies. No other differences between the two groups were found. Unlike our study, the authors did not assess changes in body weight or insulin doses and such data are not available [

18]. In another study, conducted in Poland, involving 209 females with T1D, treated with either CSII or MDI, pregnancy planning, despite better metabolic control before gestation and in the first trimester of pregnancy, was not associated with better pregnancy outcomes. However, the authors found that lack of pregnancy planning and high HbA1c level at the first trimester were independent predictors of macrosomia and LGA [

19]. In a large study, conducted in Spain, which involved 425 women with pregestational diabetes (306 with T1D) although pregnancy planning was associated with better metabolic control, the authors did not find significant differences between the groups regarding obstetric and neonatal outcomes. Similarly to our study, weight gain was not significantly different, as was the increase in insulin dose in the groups of women who planned and did not plan pregnancy [

20]. In another study of the same authors, lack of pregnancy planning and elevated HbA1c before pregnancy and in the first trimester were associated with significantly higher risk of fetal hypertrophic cardiomyopathy which was diagnosed in 5.8% of neonates [

21]. In our study 3 such cases were diagnosed. In all of them HbA1c values were higher then recommended before pregnancy (mean 8.0%) and in the first trimester (7.3%). Also in the first CGM report all of them had TIR <50% and TAR >50%, which can explain that neonatal complication. Pregnancy was planned in one of them.

Excessive weight gain (29 out of 98 women) was in our study associated with adverse neonatal outcomes, namely with macrosomia and LGA. It could be expected that planning pregnancy, in addition to better metabolic control, would also be associated with greater dietary discipline during gestation and with lower weight gain in pregnancy. However, in our study women who planned pregnancy had a similar weight gain compared to those who did not plan a gestation, and the increase in insulin dose, as well as the birth weight of newborns were not significantly different. In a recently published meta-analysis high pregestational BMI and excessive gestational weight gain were associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Analysis of 18,965 pregnancies in T1D revealed that periconceptional BMI ≥25 kg/m

2 was associated with 22% higher risk of perinatal complications (congenital malformation, preeclampsia, and neonatal intensive care unit admission) and each 1 kg/m

2 higher was translated to 3% higher odds of these complications. Excessive gestational weight gain was associated with both neonatal, as well as maternal adverse outcomes: preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, LGA and macrosomia [

22]. Limiting weight gain during pregnancy can be achieved by behavioral interventions – dietary interventions and physical activity. A systematic review and meta-analysis of such interventional studies documented that lifestyle interventions based on diet and physical activity were associated with reduced gestational weight gain which was associated with lower risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Despite this meta-analysis included only studies in non-diabetic population, it indicates the need for wide implementation of such interventions in routine antenatal care also in women with T1D [

23].

At present, we are facing a completely new paradigm of diabetes treatment during pregnancy in women with type 1 diabetes. It applies not only to use of new technologies, but also to behavioral treatment which include appropriate diet and adequate physical activity [

14]. Better glycemic control can be achieved by using CGM and hybrid closed-loop (HCL) systems of insulin delivery. In a review paper addressed to this issue the authors underlined that there is strong evidence documenting improvement of glycemic control with use of CGM with advanced HCL (AHCL) [24]. Also recently published meta-analysis of thirteen studies with 450 participants revealed better glycemic control measured by TIR, reduced time spent in hyperglycemia and reduced glucose variability [25]. However, more evidence is necessary to determine whether such a treatment is associated also with better pregnancy outcomes [24,25].

Our study is obviously not free from several limitations. First limitation is its retrospective design. On the other hand, it brings certain benefits as it reflects the effects of treatment conducted in everyday clinical practice in accordance with current guidelines and recommendations regarding therapeutic goals. The second limitation of our study is its single-center nature. However, also in this case some benefits can be found – the treatment was provided by the same personnel, using the same rules regarding insulin dose adjustment, procedures in case of hypo- or hyperglycemia, the same educator provided dietary and behavioral advisement in all patients. The third limitation is relatively low number of study participants which was associated with insufficient statistical power which did not allow us to draw far-reaching conclusions.

5. Conclusions

Pregnancy planning is associated with significantly better glycemic control in pregnant women with T1D and lower number of preterm deliveries. Despite it demonstrated relatively small impact on clinically relevant pregnancy outcomes, its role should not be underestimated and planning gestation should be recommended to all women of reproductive age with type 1 diabetes who are considering motherhood in the future.

Constant development of modern technologies, including AHCL systems, will have an indisputable impact on the future paradigm of treatment of pregestational diabetes. However its impact on clinically relevant maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnancy is yet to be discovered and confirmed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J. and M.D.; methodology, A.J. and M.D.; software, M.D.; validation, A.J., L.K-S. and M.D.; formal analysis, M.D.; investigation, A.J. and L.K-S.; resources, X.X.; data curation, A.J. and M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.; writing—review and editing, M.D. and A.J.; visualization, M.D.; supervision, M.D.; project administration, A.J and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the District Medical Chamber in Rzeszów, Resolution No. 93/2023/B of 27th November 2023 and by the appropriate administrative bodies, and it was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in an appropriate version of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived by Bioethics Committee due to retrospective and observational design of the study and anonymization of data.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

In our study and during preparation of this manuscript we did not use generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). Part of these data were presented during 58th European Association for the Study of Diabetes held in Hamburg in 2023 as a short oral presentation and were published in a form of abstract: Juza A, Kołodziej-Spirodek L, Dąbrowski M. Pregnancy planning and time in range are essential for pregnancy outcomes in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2023, 66 (Suppl 1), S259.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHCL |

Advanced hybrid closed-loop |

| CGM |

Continuous glucose monitoring |

| CS |

Cesarean section |

| CSII |

Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion |

| CV |

Coefficient variability |

| GOCCF |

Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity Foundation |

| HCL |

Hybrid closed-loop |

| LGA |

Large for gestational age |

| PLGS |

Predictive low-glucose suspend |

| SAP |

Sensor-augmented pump |

| SGA |

Small for gestational age |

| T1D |

Type 1 diabetes |

| TAR |

Time above range |

| TBR |

Time below range |

| TIR |

Time in range |

References

- Szabłowski, M.; Klimas, P.; Wiktorzak, N.; Okruszko, M.; Peczyńska, J.; Jamiołkowska-Sztabkowska, M.; Borysewicz-Sańczyk, H., Polkowska, A.; Zasim, A.; Noiszewska, K.; Głowińska-Olszewska, B.; Bossowski, A. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes in Podlasie region, Poland, in years 2010-2022 - 13-years-single-center study, including COVID-19 pandemic perspective. Epidemiologia cukrzycy typu 1 na Podlasiu w latach 2010–2022 – 13-letnie badanie jednoośrodkowe, z uwzględnieniem perspektywy pandemii COVID-19. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2025, 31, 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Ferry, P.; Dunne, F.P.; Meagher, C.; Lennon, R.; Egan, A.M.; Newman, C. Attendance at pre-pregnancy care clinics for women with type 1 diabetes: A scoping review. Diabet Med. 2023, 40, e15014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chivese, T.; Hoegfeldt, C. A.; Werfalli, M.; Yuen, L.; Sun, H.; Karuranga, S.; Li, N.; Gupta, A.; Immanuel, J.; Divakar, H.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: The prevalence of pre-existing diabetes in pregnancy - A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published during 2010-2020. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022, 183, 109049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ersson, M.; Norman,; M, Hanson, U. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in type 1 diabetic pregnancies: A large, population-based study. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2005–2009. 2009, 32, 2005–2009. [CrossRef]

- Mackin, S.T.; Nelson, S.M.; Kerssens, J.J.; Wood, R.; Wild, S.; Colhoun, H.M.; Leese, G.P.; Philip, S.; Lindsay, R.S.; & SDRN Epidemiology Group. Diabetes and pregnancy: national trends over a 15 year period. Diabetologia. 2018, 61,1081-1088. [CrossRef]

- Araszkiewicz, A.; Borys, S.; Broncel, M.; Budzyński, A.; Cyganek, K.; Cypryk, K.; Cyranka, K.; Czupryniak, L.; Dąbrowski, M.; Dzida, G.; et al. Standards of Care in Diabetes. The position of Diabetes Poland – 2025. Current Topics in Diabetes. 2025, 5, 1–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feig, D.S.; Donovan, L.E.; Corcoy, R.; Murphy, K.E.; Amiel, S.A.; Hunt, K.F.; Asztalos, E.; Barrett, J.F.R.; Sanchez, J.J.; de Leiva, A.; et al. … CONCEPTT Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2017, 390, 2347–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, C.; Ero, A.; Dunne, F.P. Glycaemic control and novel technology management strategies in pregestational diabetes mellitus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023, 13, 1109825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citro, F.; Bianchi, C.; Nicolì, F.; Aragona, M.; Marchetti, P.; Di Cianni, G.; Bertolotto, A. Advances in diabetes management: have pregnancy outcomes in women with type 1 diabetes changed in the last decades? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023, 205, 110979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurawska-Kliś, M.; Kosiński, M.; Kuchnicka, A.; Rurka, M.; Hałucha, J.; Wójcik, M.; Cypryk, K. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion does not correspond with pregnancy outcomes despite better glycemic control as compared to multiple daily injections in type 1 diabetes - Significance of pregnancy planning and prepregnancy HbA1c. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021, 172, 108628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourou, L.; Vallone, V.; Vania, E.; Galasso, S.; Brunet, C.; Fuchs, F.; Boscari, F.; Cavallin, F.; Bruttomesso, D.; Renard, E. Assessment of the effect of pregnancy planning in women with type 1 diabetes treated by insulin pump. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wender-Ożegowska, E.; Bomba-Opoń, D.; Brązert, J.; Celewicz, Z.; Czajkowski, K.; Gutaj, P.; Malinowska-Polubiec, A.; Zawiejska, A.; Wielgoś, M. The Polish Society of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians standards for the management of patients with diabetes. Ginekologia Perinatologia Prakt. 2017, 2, 215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, H.R.; Howgate, C.; O’Keefe, J.; Myers, J.; Morgan, M.; Coleman, M.A.; Jolly, M.; Valabhji, J.; Scott, E.M.; Knighton, P. et al. & National Pregnancy in Diabetes (NPID) advisory group. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: a 5-year national population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhalima, K.; Beunen, K.; Siegelaar, S.E.; Painter, R.; Murphy, H.R.; Feig, D.S.; Donovan, L.E.; Polsky, S.; Buschur, E.; Levy, C.J.; et al. Management of type 1 diabetes in pregnancy: update on lifestyle, pharmacological treatment, and novel technologies for achieving glycaemic targets. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 490–508, [published correction appears in Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, e12. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00230-9.]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, R.K.; Kodani, N.; Itoh, A.; Meguro, S.; Kajio, H.; Itoh, H. A sensor-augmented pump with a predictive low-glucose suspend system could lead to an optimal time in target range during pregnancy in Japanese women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetol Int. 2024, 15, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyganek, K.; Hebda-Szydlo, A.; Katra, B.; Skupien, J.; Klupa, T.; Janas, I.; Kaim, I.; Sieradzki, J.; Reron, A.; Malecki, M. T. Glycemic control and selected pregnancy outcomes in type 1 diabetes women on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and multiple daily injections: the significance of pregnancy planning. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010, 12, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekäläinen, P.; Juuti, M.; Walle, T.; Laatikainen, T. Pregnancy planning in type 1 diabetic women improves glycemic control and pregnancy outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 29, 2252–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourou, L.; Vallone, V.; Vania, E.; Galasso, S.; Brunet, C.; Fuchs, F.; Boscari, F.; Cavallin, F.; Bruttomesso, D.; Renard, E. Assessment of the effect of pregnancy planning in women with type 1 diabetes treated by insulin pump. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żurawska-Kliś, M.; Kosiński, M.; Kuchnicka, A.; Rurka, M.; Hałucha, J.; Wójcik, M.; Cypryk, K. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion does not correspond with pregnancy outcomes despite better glycemic control as compared to multiple daily injections in type 1 diabetes - Significance of pregnancy planning and prepregnancy HbA1c. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021, 172, 108628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimenea, A.; Calderón, A.M.; Antiñolo, G.; Moreno-Reina, E.; García-Díaz, L. Assessing the impact of pregnancy planning on obstetric and perinatal outcomes in women with pregestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024, 209, 111599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimenea, A.; Calderón, A.M.; Antiñolo, G.; Moreno-Reina, E.; García-Díaz, L. Predictive Value of Maternal HbA1c Levels for Fetal Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Pregestational Diabetic Pregnancies. Children (Basel). 2025, 12, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, N.; Ezeoke, A.; Petry, C.J.; Kusinski, L.C.; Meek, C.L. Associations of High BMI and Excessive Gestational Weight Gain With Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2024, 47, 1855–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teede, H.J.; Bailey, C.; Moran, L.J.; Bahri Khomami, M.; Enticott, J.; Ranasinha, S.; Rogozinska, E.; Skouteris, H.; Boyle, J.A.; Thangaratinam, S.; Harrison, C.L. Association of Antenatal Diet and Physical Activity-Based Interventions With Gestational Weight Gain and Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2022, 182, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).