1. Introduction

Modern physics is based on two ground-breaking revolutionary theories, relativity and quantum mechanics, which have transformed our understanding of the nature of reality. The complexities and paradoxes of quantum mechanics are typically captured in Niels Bohr’s famous quote, “If you have studied quantum mechanics and are not shocked, then you have understood nothing" (Bohr, N. (1958). Atomic Physics and Human Knowledge (Atomic Physics and Human Knowledge. New York: John Wiley & Sons).

In the 20th century, quantum theory, as a fundamental theory of physics, is a valuable scientific legacy, shaped by the work of eminent scientists such as Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr [

1,

2,

3]. Quantum theory was the starting point of a scientific renaissance that led to the development of Quantum Physics (QF) and science on a global scale. This progress has led to the significant development of quantum technologies affecting important areas such as health, drug development, cryptography, industry, economics, data security, climate change and artificial intelligence [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Quantum Computing (QC) devices and quantum technologies, once confined to academic round table discussions, have now attracted the interest of many countries and private companies alike and have become key tools in scientific research. The field of quantum technologies, which makes them essential tools for the advancement of science and information technology (QIST), has generated intense interest due to its extraordinary computational capabilities, attracting international countries such as the U.S.A., E.U., China, U.K. and others, who are investing billions of euros to gain a quantum advantage in this powerful technology [

2,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

In addition, private companies, scientific institutions and industries are actively involved in this technological competition, fostering ongoing research and experimentation, with the aim of developing a new generation of technologies making use of quantum properties such as superposition and entanglement [

7].

With the development of quantum technologies, the demands of the workforce are affected, resulting in the labour market seeking innovative knowledge and high skills in all professional fields, which has an impact on the education system [

16]. Education must adapt to the new conditions, playing a key role in preparing students from an early age, through organised teaching that enhances their knowledge and skills, so that they become active and creative citizens, useful to society [

17,

18]. As a result, the teaching of quantum mechanics has been integrated into Secondary Education (SE) curricula as part of physics in several countries, making it necessary to learn about quantum science and its applications [

19,

20,

21]. However, the complexity of the concepts, as well as the fact that this field requires a different way of thinking compared to the traditional way of thinking applied until recently in classical physics, make it difficult to teach it effectively and to provide quality education in the educational context.

There is an extensive research literature highlighting the barriers to conceptual understanding, misconceptions, concerns and confusions in thinking, as well as dilemmas regarding the approach and methods of teaching quantum physics. The difficulty of accessing the field of quantum science continues to be a challenge for both students and teachers. This is largely due to their traditional way of thinking and inadequate training [

5,

20,

22,

23].

This reality requires increased attention and makes it imperative to promote quantum literacy, which includes an understanding of the fundamental principles of quantum physics and their application to everyday life and modern technologies. Familiarity with these concepts is crucial to prepare new generations to understand the scientific and technological developments that will affect the future of society. Incorporating quantum literacy into education is crucial as it bridges the gap between classical and quantum thinking, enhancing the understanding of scientific concepts [

17,

18,

22]. At the same time, it fosters critical thinking and expands students’ knowledge, cultivating skills that will enable them to more effectively understand and meet future challenges in the field of quantum science.

Consequently, the adoption of alternative teaching methods that will enhance the effectiveness of learning, contributing to the design of more efficient learning pathways and teaching practices is required. Such approaches include quantum computing and the use of innovative educational games, which make the learning process more enjoyable and entertaining for IE students [

17].

Undoubtedly, quantum literacy represents a unique opportunity to reshape the way of thinking through the integration of quantum computing and the use of quantum games in secondary education curricula. QF, with its required different cognitive approach and understanding, necessitates the development of QF. As Francis Bacon says: “Knowledge is power" and “Science is the best way to acquire knowledge" (F. Bacon, 1605), underlining (highlighting) the fundamental importance of scientific learning and knowledge acquisition for the evolution of society. Therefore, QL, which promotes understanding of QF, empowers critical thinking, and enhances skills to address contemporary scientific challenges, is key to effective education and preparation of students. In this way, students will be able to adequately understand new technologies without requiring a mathematical background and to actively participate in the scientific progress of the future [

1,

2,

5,

7,

8,

9,

17,

18,

22,

26].

The literature refers to a number of papers that propose a conceptual approach to quantum physics through software that exploits games. The study by C Zeki et al., entitled “Quantum Games and Interactive Tools for Quantum Technologies Outreach and Education" [

27], presents a wide range of interactive tools and quantum games as a means of promotion and education in quantum technologies. These tools help players to become familiar with the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics. For example, several software, educational platforms and online tools are presented, such as Hello Quantum, Hello Qiskit, Particle in a Box and others. These initiatives enhance quantum literacy by introducing new methods of education that do not require a mathematical background [

12,

17,

26].

Cultivating QL is not only a critical educational priority pillar, but also contributes to enhancing knowledge, laying the foundations and paving the way for the creation of innovative and progressive solutions. At the same time, it plays a key role in the scientific and technological innovations that will lead to disruptive changes in the world of tomorrow.

In this work, we present a pilot action that we implemented in about 80 high school students, aged 16-17 years old, in high schools of Larissa. The study was implemented in three different Lyceums (Experimental, State and Private) in order to take into account the diversity of the students in terms of their social, cultural and educational level. Initially, the activity started with an overview lecture introducing students to the QIST formalism and quantum concepts such as superposition and bifurcation. Then the importance of generating the B92 quantum key distribution technique was introduced. This was followed by a hands-on demonstration through selected quantum games, facilitating students’ understanding of the preceding concepts. The final stage included a questionnaire, through which students’ knowledge, experiences and interest in quantum science were assessed. The purpose of this paper is to highlight the necessity and importance of integrating quantum literacy into secondary school curricula. A pilot study with students confirmed its effectiveness in enhancing quantum computing education and facilitating the understanding of quantum physics. It is clear that this can be effectively achieved through Quanum Computing (QC) and innovative quantum games, allowing students at all learning levels to approach the magical world of quantum science in an enjoyable way that will shape our future.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2 issues related qith literacy are discussed while in

Section 3 the basic concepts of Quantum Computing are presented.

Section 4 analyzes the quantum key distribution protocol and the game given to students. In

Section 5 the study design employed for this work is presentd and the results are given in

Section 6 while a discussion based on the results are provided in

Section 7. Finally,

Section 8 concludes this work and some future research directions are provided.

2. Quantum Literacy in Secondary Education

We are in the heart of the 4th Industrial Revolution where the development of critical skills is a vital prerequisite for students to actively participate in scientific research and innovation. The rapid progress of modern science, which increasingly relies on next-generation technology, makes quantum literacy an integral part of the educational process. In today’s educational landscape, schools play a central role in preparing students for the challenges of the 21st century by strengthening both their linguistic and cognitive skills through literacy [

18].

Strengthening literacy in today’s educational reality is a cornerstone of learning and a foundation for the formation of critical thinking citizens, capable of actively contributing to social progress. Literacy, however, is not limited to mere linguistic competence, i.e. the ability to use spoken and written language, but extends to the wider ability to understand, interpret and communicate effectively through a variety of forms of expression [

24]. In the era of digital innovation and rapid technological and scientific developments, literacy is becoming multidimensional and interdisciplinary. It extends to areas such as mathematics and critical thinking, but also to specialised fields of knowledge such as digital, information, scientific and quantum literacy. All these forms are interrelated and complementary, with a common denominator being their contribution to the development of the skills necessary for the understanding, use and efficient use of information, digital tools and technological media. At the same time, they strengthen and prepare students’ ability to approach complex scientific concepts, such as quantum mechanics and quantum science, which depart significantly from traditional scientific concepts and require the development of new ways of thinking and interpreting the physical world [

18,

24,

28,

29,

30,

35].

Digital Literacy refers to the ability to use digital technologies and information effectively and safely. It includes the search, evaluation, processing and presentation of information through digital media, as well as the development of skills for the responsible use of digital tools, while enhancing critical thinking and knowledge management in today’s digital age [

28].

Information Literacy is a basic prerequisite for the use of technologies, promoting continuous learning and the development of critical thinking. It includes the ability to identify reliable sources, to evaluate and make effective use of information, contributing to decision-making, interpretation of data and practical application of knowledge [

29].

Scientific Literacy refers to the understanding and application of scientific principles and methods, as well as the knowledge of basic concepts from the fields of physics, chemistry and biology. It aims at enhancing the ability to solve everyday problems and prepares students to approach complex systemic issues such as the concepts of quantum physics and the operation of quantum computers in comparison with classical computers [

30]

Quantum Literacy marks the next step in science and technology education, making quantum science more accessible to the general public, even without the need for a mathematical background. Cultivating quantum literacy is crucial, as it facilitates understanding of current scientific developments and enhances the use of future technologies, contributing to a meaningful and quality education [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

24,

25]. Advances in QC and the rapid growth of quantum technologies have put quantum physics at the heart of scientific research and innovation. In this context, education in QL is becoming crucial for the further development of science, industry and progressive technology [

45,

46].

The integration of QL into secondary school curricula is a critical-capital need, as it prepares students for the scientific and technological challenges of the future. This need is undeniable, as QL enhances students’ ability to think critically, analyse complex problems and contribute to a community that harnesses the potential of the future. At the same time, it enables students to cultivate specific skills and understand the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics, equipping them to meet the demands of the times and contribute to the development of new ways of thinking and innovation [

18,

45,

46].

Understanding QF, due to its complexity and abstract character, requires the application of innovative pedagogical approaches. These must meet the learning needs of students and actively support the development of QL. Through targeted and experiential educational practices, students can familiarise themselves with the concepts of QF and acquire the skills needed to actively participate in the scientific and technological progress of the future [

2,

4,

5,

7,

9,

18,

21,

22,

23,

25].

Based on the existing literature, various interactive logics, educational platforms, web-based tools and quantum games such as IBM Q Experience are listed as examples, Hello Quantum [

31], Hello Qiskit [

32], Particle in a Box [

33], Psi and Delta [

34], QplayLearn [

34], Virtual Lab by Quantum Flytrap [

35,

36], Quantum Odyssey [

37], ScienceAtHome [

38] and Virtual Quantum Optics Laboratory [

39,

40]. These resources provide (free) educational tools that allow students to interact with quantum computers and perform experiments, facilitating their understanding of the basic principles of quantum science in an interactive, hands-on and creative way. In addition, educational and training programmes for the development of quantum skills are offered through platforms and initiatives such as Quantum Flagship (QTEduCSA) [

42,

43], Quantum Computing Report, Coursera, MIT, Delft University, IEEE Quantum courses, the QWorld network [

40], and educational material on Geeks for Geeks. These programs include participation in quantum hackathons [

35] and Quantum game jams [

42], offering experiential learning opportunities that combine knowledge with application.

These initiatives reinforce the central thesis of this paper, as they contribute substantially to the promotion of quantum literacy. Through innovative and participatory educational methods, they make quantum science accessible to students and learners of all levels, without the requirement of specialized or advanced mathematical knowledge. These activities combine entertainment and learning, facilitating understanding and deepening of complex concepts through experiential, practical and creative experiences. The cultivation of QL can be achieved through the use of educational tools and QC applications, which transform abstract and often obscure concepts into understandable and tangible learning experiences for students [

18].

Quantum Computing is emerging as a revolutionary computational paradigm, based on the principles of QF, marking a radical upheaval in data processing (or overturning traditional approaches to data processing). Unlike conventional computers, which operate (or are limited to two states) on the basis of binary digits (0 or 1), QC exploits quantum bits (qubits), which can be in multiple states simultaneously. The fundamental principles of quantum computing include superposition and quantum entanglement provide computational power far beyond that of classical computers, making it possible to solve extremely complex problems that were previously impossible to tackle. As a result, this computational superiority of quantum computers is expected to radically transform the way we process and exploit information, opening up new horizons in computational science, such as cryptography, biology, chemistry, machine learning and many more.

3. Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Quantum Computing

In the modern era, information is emerging as a fundamental factor in the evolution of humanity, transforming amorphous data into valuable knowledge. In the digital environment we live in, information moves at lightning speed, permeating every aspect of our existence. It is not just a collection of data, but the ability to process and use it, making sense of it, and innovating, thus shaping our understanding of the world and the course of society.

In classical computers, the elementary unit of information is the bit (binary digit), which can be in one of two states, 0 or 1. Through transistors, data is encoded and processed, producing information that humans convert into knowledge. In contrast, in quantum computers, the unit of information is the quantum bit, the

qubit (QUantum BIT). The qubit is a two-state quantum system (vector instead of monometer) and it is denoted as in Equation

1 [

3]:

A qubit is not equivalent to a classical bit. Unlike a bit, a qubit can be in a superposition of states, that is, it can have values 0 and 1 simultaneously, utilizing the principles of superposition and entanglement. This property offers exponentially more computing power, allowing for the simultaneous processing of huge amounts of information. Information, in physical form, influences the evolution of systems, while quantum mechanics explains the ability of qubits to be in multiple states simultaneously as in Equation

2 where

a and

b are complex numbers and denote the probability

or

to measure qubit in state |0〉 or |1〉 respectively where

.

The fundamental properties of quantum mechanics can be summarized as follows [

3]:

Superposition: in a quantum system, the qubit, can be in multiple states, e.g. 0 and 1, at the same time until a measurement is made, which will lead it to a particular state. This property allows two qubits to simultaneously register the four binary numbers 00, 01, 10 and 11, and in general n qubits can manage binary states.

Entanglement: a strange phenomenon of the microcosm, quantum mechanics. It is a quantum state in which two particles or groups of particles interact instantaneously, where two or more qubits are connected in such a way that their state cannot be described independently. This means that qubits behave as a single entity, regardless of the distance between them. Measuring the state of one qubit instantaneously affects the state of the other, as if there were a direct “communication" between them.

Teleportation: the property of instantaneously transferring a quantum state, quantum information, from one point to another or from a sender to a remote receiver, without loss. In quantum computers, the information is not copied, but rather moved by exploiting phenomena such as the quantum entanglement.

These fundamental properties of QF are the mechanisms for achieving quantum supremacy and quantum advantage. Quantum supremacy refers to the ability to perform calculations at a speed far exceeding the capabilities of classical computers, i.e. faster information processing. The quantum advantage, on the other hand, focuses on the ability to solve problems that are practically impossible to solve with classical computers, leading to qualitatively superior results.

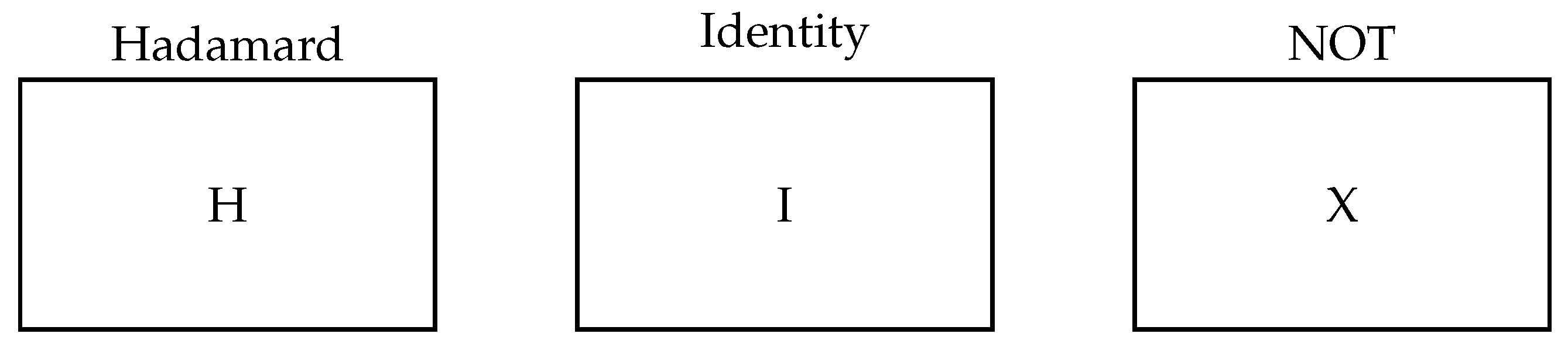

In quantum computing these properties can be represented by a standard mathematical mechanism using quantum gates, registers and quantum circuits. Some of the most important gates are the superposition or Hadamard (H), Identity (I), Not (X), and Controlled not (Cx) as in Equation

3 [

3].

As an example, the effect of the Hadamard gate on a qubit, for example to both 0 and 1, lead it to superposition, i.e. to have a probability of 0.5 for occurrence after measuring 0 and also 0.5 for measuring 1 (Equation

4).

Interestingly, the dual application of the Hadamard gate leads to certainty as shown in Equation

5.

Similarly, the effect of the other gates mentioned above is as follows:

Identity: , ,

Not: , ,

Controlled Not: , .

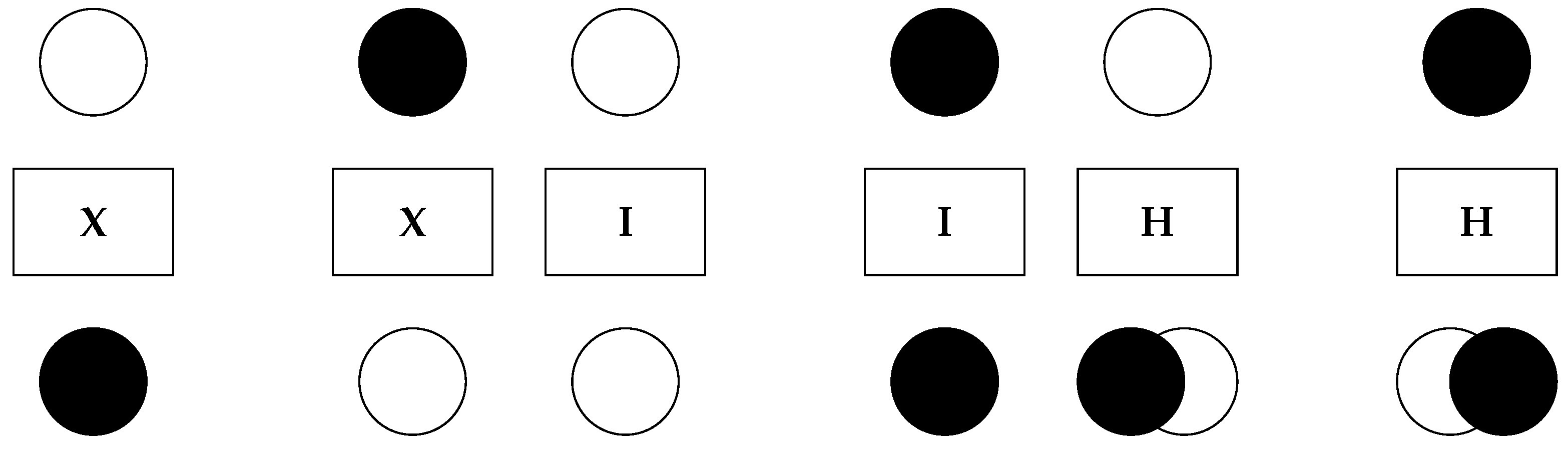

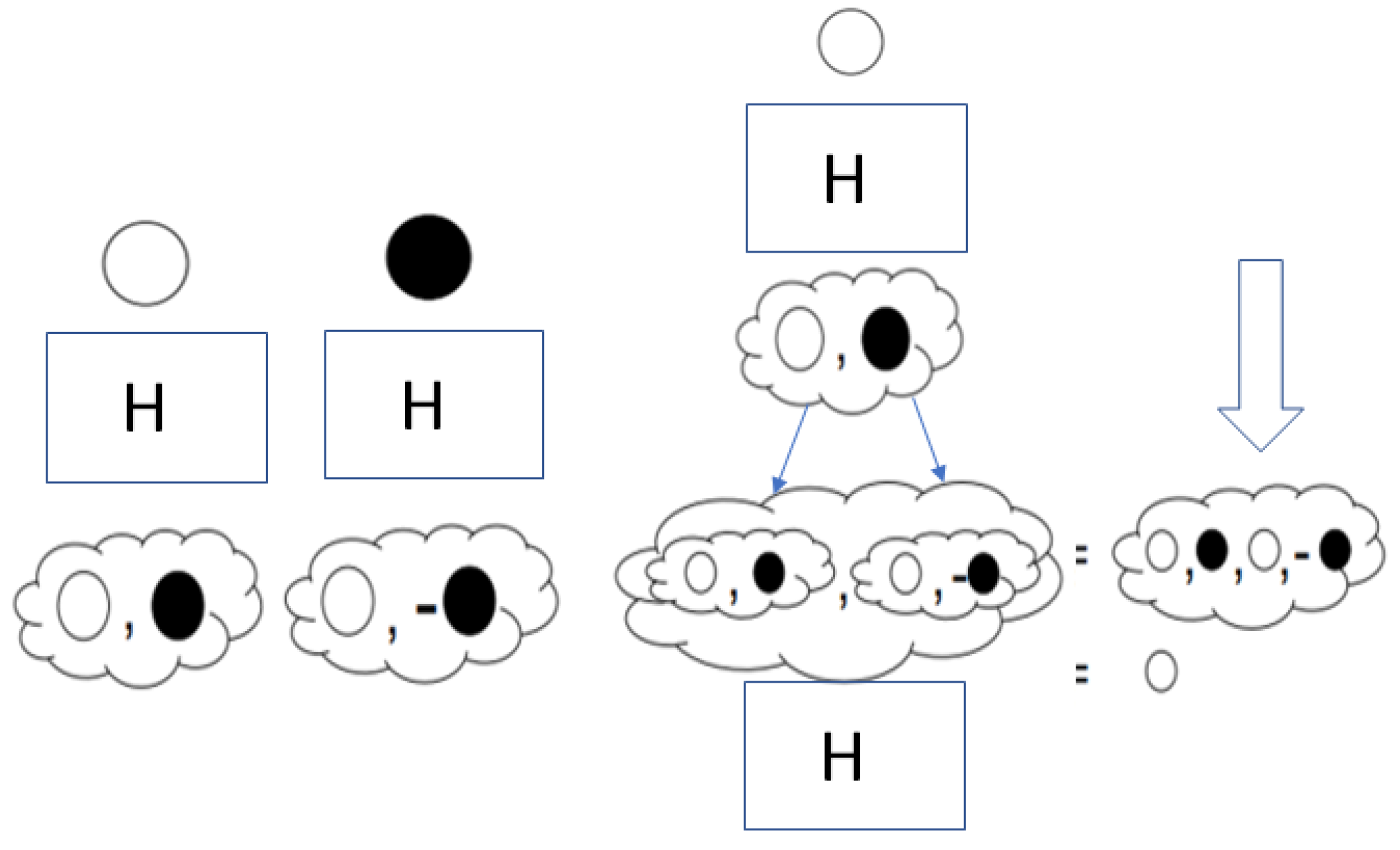

The main task of this research was not to use a mathematical formalisation of both qubits and quantum gates and circuits and as a first approach qubits were replaced by balls, white for |0〉 and black for |1〉, and boxes instead of gates such as for example box H or box X (

Figure 1,

Figure 2) [

26].

Finally, the explanation of the Hadamard double gate application was given that when a white ball enters the result is a white or black ball with equal probability of occurrence but when a black ball enters the result is again a white but minus black ball again with equal probability. Thus, if white ball is entered in box H has not yet decided the result but it will be either white or black ball. If it is a white ball the second box will return either white or black whereas if it was black it would return either white or minus black. Therefore, the black balls cancel each other out and the probability remains that it is a white ball or white again i.e. 100% white (

Figure 3). A similar result is obtained if the first box returns a black ball where in the end the result will be black again.

4. Quantum Key Distribution

Since ancient times, humanity has had secrets that it had to protect so that even if they fell to unauthorized persons they could not be interpreted. This is how the need for cryptography came about with one of the first successful attempts being Caesar’s algorithm known as the Caesar Cipher. It was based on a simple method of constant shifting of letters by a constant amount of k called the key (nowadays symmetric cryptography). If for example , then all A’s would be shifted to C, B’s to D and so on and cyclically Y’s to A and finally Z’s to B. The disadvantage of this method is the constant shifting of the letters so that in the entire cipher text each letter was represented by exactly the same letter throughout the text. Of course, a huge improvement would be to display each letter differently each time it appeared in the text. This is exactly what Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) comes to solve where many protocols have already been developed but in this paper we focus on B92.

4.1. B92 Protocol

B92 QKB proposed by Charles Bennett in 1992 which was chosen for this study is a simple protocol since it uses only two non-orthogonal quantum states rather than four and the quantum gates of superposition (Hadamard) and identity [

48].

Assuming that two persons, namely Demetra and Persephone wish to communicate and they decide to create a symmetric key using the above protocol. Firstly the pre-decide to:

create a random bit sequence of the same length that will form the basis for the key, and

create a quantum circuit of length equal to the length of their secret bit sequence and in addition: Demetra: apply Hadamard only if her key is 1 and nothing (Identity) in case she has 0 Persephone: apply Hadamard only if her key is 0 and nothing (Identity) in case she has 1.

After that, Demetra sends her sequence of H and I to Persephone who applies her sequence of H and I to the quantum circuit as in

Table 1. In addition, Persephone after measuring the circuit substitutes the |+〉 with 1, and |0〉 with 0 which is the final bit sequence and sends it to Demetra, in this case it is

.

Now, both Demetra and Persephone have the final bit sequence which in our case which they place under their original random bit sequence and ignoring the 0’s, they select only the digits of their original hidden bit sequence that match 1 of the final bit sequence and this is the key! (

Table 2).

4.2. The B92 Game

The game was based on the QKD B92 protocol but instead of qubits and gates, students used balls and boxes. They were already familiar with the application of any combination of the Hadamard and Identity gates and as in first stage they were asked to create a random bit sequence of 7 bits and write it down to a piece of paper.Then they followed what they had already pre-decided about the boxes (gates) that they had to apply accordingly they digits. The combination of two Hadamards or two Identities produced a certain result and they place a zero to a next line, while any combination of Hadamard and Identity produced an uncertain result and they insert an 1 (

Table 3).

And the produced key was which surprised them since they started with a secret random bit sequence unknown to each other and at the end they produced the same key.

At the final stage of our study an anonymous questionnaire was given to the students where the results were very promising.

5. Study Design

This study employed a mixed methods approach to explore SE students’ perceptions, understanding, and difficulties regarding quantum computing and quantum mechanics following a dedicated outreach presentation. By integrating both quantitative and qualitative data, the study aimed to obtain a comprehensive understanding of how students engaged with the concepts presented.

5.1. Participants

The participants were third-grade students from three secondary education institutions located in the region of Larissa, Greece: one Private Lyceum, one General Lyceum, and one Experimental Lyceum. These schools represented typical variations within the Greek secondary education system and provided a diverse yet manageable population for the exploratory purpose of this study. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and no personal identifying information was collected. All participants provided informed consent, and the study adhered to ethical research guidelines in accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). A total of 78 valid responses were collected, forming the basis of the subsequent analysis. Although the sample was drawn from three different schools, preliminary comparisons indicated that student responses were highly consistent across institutions. As a result, the data were treated as a unified dataset to emphasize overall trends and maintain focus on the exploratory objectives of the study.

5.2. Approach

An original questionnaire was developed to capture students’ perceptions, prior knowledge, and self-reported learning outcomes related to quantum computing and quantum mechanics based on the main principles as suggested from [

49]. The questionnaire was administered immediately following the educational intervention, which consisted of a simplified, student-friendly presentation introducing key concepts of quantum computing, such as superposition, entanglement, quantum gates, and quantum cryptography.

The questionnaire was structured into three main sections. The first section included demographic questions (gender, age, and school type) and questions on prior knowledge of quantum computing. The second section comprised nine Likert-scale items assessing students’ perceptions of the presentation, their understanding, the perceived difficulty of transitioning from classical to quantum physics, and their future intentions related to quantum studies. All Likert items followed a five-point intensity scale ranging from “Not at all" to “Very much". The third section included open-ended and multiple-choice questions evaluating specific conceptual understanding (e.g., superposition, entanglement) and invited students to describe which part of the presentation they found most difficult.

The detailed questionnaire is as follows:

Q1: Do you have any prior knowledge about presentation and in particular quantum computer science and quantum mechanics (QM)? If so, where did you acquire it from?

Q2: How interesting did you find the presentation in terms of learning about quantum computer science, quantum mechanics (QM) and key distribution? (Not at all, Little, Moderately, Much, Very much)

Q3: Do you think that learning quantum computer science and quantum mechanics is easy? (Not at all, Little, Moderately, Much, Very much)

Q4: Could quantum computing make a substantial contribution to improving our world? (Not at all, Little, Moderately, Much, Very much)

Q5: Do you think that understanding quantum computer science requires advanced knowledge of mathematics and physics? (Not at all, Little, Moderately, Much, Very much)

Q6: Do you feel that the prerequisite knowledge was not sufficient or was a barrier to understanding? Did you feel that the lack of specialized knowledge made it difficult for you to delve into the quantum world? (Not at all, Little, Moderately, Much, Very much)

Q7: Do you think the transition from classical to quantum physics is easy? (Not at all, Little, Moderately, Much, Very much)

Q8: What is the difference between a bit and a qubit? Could you identify with an example from everyday life what could be used as a bit and what could be used as a qubit?

Q9: Did the presentation help you understand the importance of key distribution creation? (Not at all, Little, Moderately, Much, Very much)

Q10: Which part of the presentation did you find most difficult?

Q11: Quantum superposition is a property of quantum mechanics that allows: a) A quantum system cannot exist in multiple states simultaneously. b) A particle or a quantum system cannot exist in multiple states at the same time during observation. c) Two quantum states are added together in a way that does not allow them to coexist at the same time.

Q12: Quantum entanglement is a property of quantum mechanics that allows: a) Communicate with particles that are located and traveling in the universe instantaneously. b) A particle or a quantum system can be in many states simultaneously. c) A quantum state in which two particles or groups of particles interact instantaneously.

Q13: Is it possible to choose a higher education or academic course with a view to a career in the fields of quantum computing? (Not at all, Little, Moderately, Much, Very much)

5.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed on all closed-ended questions using Excel to compute frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. Visualization of results was achieved through bar and pie charts, which were grouped into two composite figures to ensure clarity and avoid information overload.

To further investigate relationships among students’ perceptions, Spearman’s rho correlation tests were conducted using Python (SciPy library) between selected Likert-scale items, as the data was ordinal and did not meet normality assumptions. The correlation analysis revealed moderate and statistically significant associations between students’ perceived interest, perceived difficulty, and future intentions regarding quantum computing.

For the open-ended question, a thematic analysis was performed to identify recurring patterns in students’ self-reported difficulties. Responses were independently reviewed and coded by the researchers. Descriptive codes were assigned to each comment and then grouped into broader themes, such as “Quantum Gates", “Quantum Cryptography", and “General Conceptual Difficulties".” The themes and their frequencies were then summarized in a frequency table. Given the relatively short and focused nature of the responses, this approach was deemed appropriate for capturing the qualitative dimension of the students’ perceptions.

6. Results

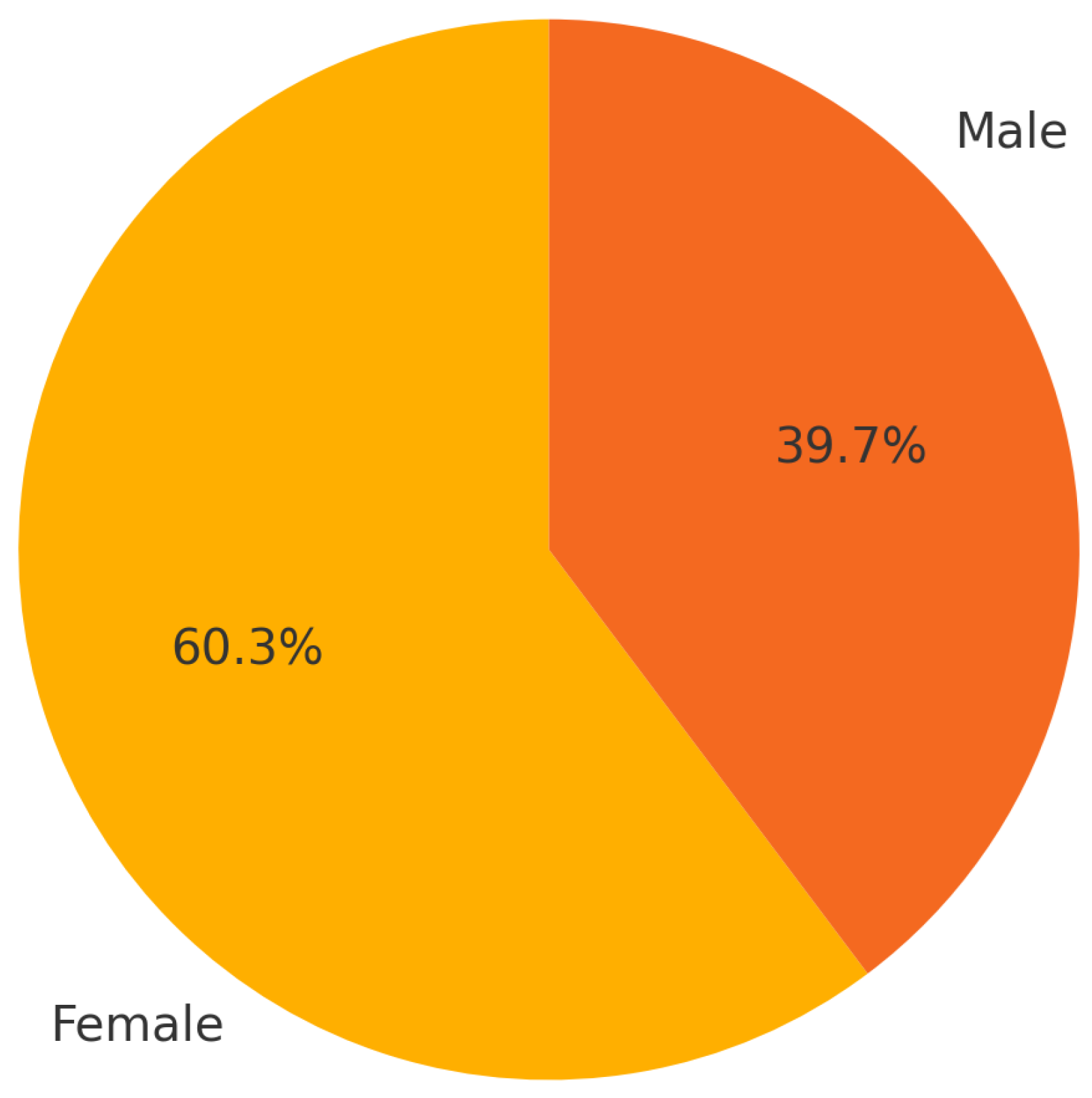

Among the

78 participants, 47 identified as female (60.26%) and 31 as male (39.74%). This distribution reflects a higher representation of female students in the sample. The gender breakdown is illustrated in

Figure 4, providing context for the interpretation of students’ perceptions and responses throughout the study.

6.1. Descriptive Analysis of Quantitative Responses

This section summarizes the students’ responses from the closed-ended items of the questionnaire. The analysis is divided into two parts: (a) Likert-scale responses concerning perceptions of the quantum computing presentation (questions Q2 to Q9 and Q13), and (b) categorical knowledge-related responses (questions Q1, Q8, Q11, and Q12).

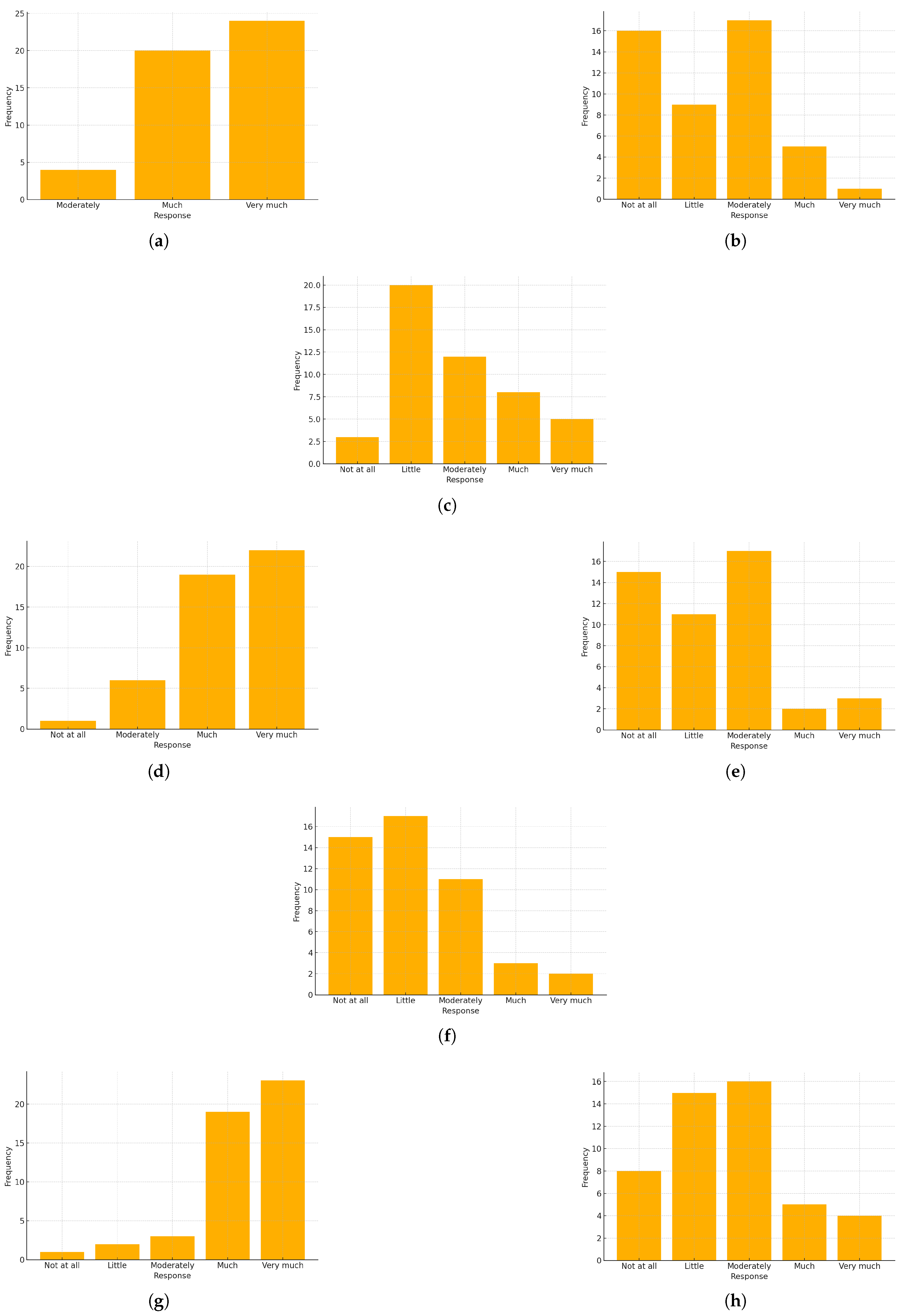

6.1.1. Likert-Scale Responses (Figure 5)

The majority of participants found the topic of quantum computing moderately to very interesting (Q2), with most responses concentrated in the categories “Moderately," “Much", and “Very much". When asked about the perceived ease of learning quantum computing and quantum mechanics (Q3), most students rated their learning experience as “Little" to “Moderately" easy, indicating a moderate level of perceived difficulty. Regarding their self-assessed level of understanding the presentation (Q4), the majority expressed relatively high understanding, mostly rating it as “Much" or “Very much."

Concerning whether advanced knowledge in mathematics and physics was necessary for understanding the topic (Q5), responses varied widely, although a significant proportion indicated it as moderately to very important. Many students acknowledged that their lack of prior knowledge moderately hindered their understanding (Q6). Additionally, when asked specifically about the ease of transitioning from classical to quantum physics (Q7), most respondents rated the transition as moderately difficult or slightly challenging.

The presentation was generally perceived as helpful in clarifying complex topics such as key distribution (Q9), with most participants rating it as “Much" or “Very much" helpful. Finally, when asked about their willingness to consider studying quantum computing or a related subject in the future (Q13), student responses were predominantly neutral (“Moderately"), although notable proportions expressed higher or lower willingness as well.

Figure 5.

(a) Q2. (b) Q3. (c) Q5. (d) Q4. (e) Q6.(f) Q7. (g) Q9. (h) Q13.

Figure 5.

(a) Q2. (b) Q3. (c) Q5. (d) Q4. (e) Q6.(f) Q7. (g) Q9. (h) Q13.

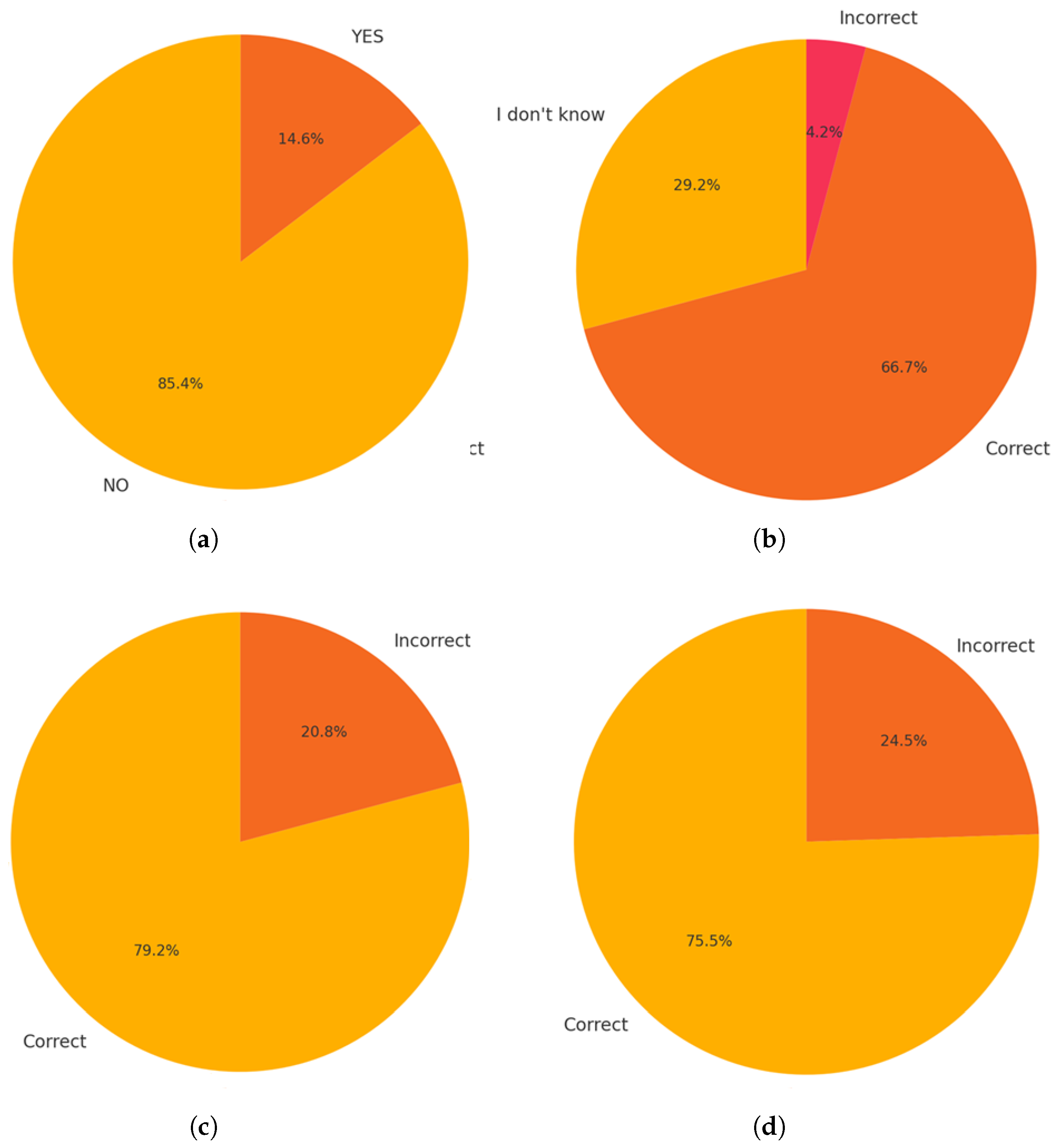

6.1.2. Categorical Knowledge-Related Responses (Figure 6)

Regarding prior knowledge of quantum computing (Q1), the vast majority (85.4%) had no previous exposure, with only a minority (14.6%) reporting some prior familiarity. When assessing specific conceptual understanding, such as the difference between a bit and a qubit (Q8), most students (68.8%) demonstrated correct understanding, while a smaller proportion (20.8%) explicitly indicated uncertainty, and a few provided incorrect responses (10.4%). For conceptual comprehension questions on quantum superposition (Q11) and quantum entanglement (Q12), the majority of students correctly answered both questions, with correct response rates of approximately 77.1% and 75.0%, respectively. Nevertheless, the presence of notable percentages of incorrect responses (22.9% for superposition and 25.0% for entanglement) highlights areas where misconceptions or misunderstandings persist.

Figure 6.

(a) Q1. (b) Q8. (c) Q11. (d) Q12.

Figure 6.

(a) Q1. (b) Q8. (c) Q11. (d) Q12.

6.2. Correlational Analysis

To further explore the relationships among students’ perceptions captured by the Likert-scale questions, Spearman’s rho correlations () were computed. Three significant correlations emerged from this analysis:

A moderate positive correlation was found between students’ perception of the necessity of advanced knowledge in mathematics and physics (Q5) and their feeling that a lack of prior knowledge hindered their understanding (Q6), (, ). This indicates that students who believed advanced mathematics and physics knowledge was crucial were more likely to perceive their own lack of background knowledge as an obstacle.

Similarly, a moderate positive correlation was observed between students’ perceived ease of learning quantum computing (Q3) and the perceived ease of transition from classical to quantum physics (Q7), (, ). This suggests that students who found the transition from classical physics easier also tended to report higher ease of understanding quantum computing concepts.

Lastly, another moderate positive correlation emerged between students’ interest in the quantum computing presentation (Q2) and their willingness to consider future studies or careers related to quantum computing (Q13), (). Students who rated the presentation as more interesting were generally more inclined to consider pursuing quantum computing academically or professionally.

These correlations underscore important links between students’ attitudes, perceived difficulties, and future interests regarding quantum computing, highlighting areas that educational interventions could strategically target.

6.3. Thematic Analysis of Open-Ended Responses

Table 4 presents the thematic analysis of students’ responses to the open-ended question, ’

’What part of the presentation did you find most difficult?" A significant number of participants (

) explicitly reported no difficulty. However, those who identified specific challenging areas predominantly cited difficulties understanding quantum gates (

) and quantum cryptography (

). A smaller subset mentioned general conceptual challenges without specific reference (

). Additionally, a few isolated mentions were made regarding challenges in grasping the concepts of quantum superposition (

), the difference between bit and qubit (

), and the overall concept of the quantum computer (

). These results underscore the variability in students’ experiences and highlight key areas where instructional clarity and additional support might be beneficial.

7. Discussion

At a time when rapid technological developments are redefining the foundations of knowledge and innovation, QL is a very promising educational option. The ability to access and understand the principles of QC must not remain the privilege of the few, but must become the right of the many [

16,

18,

26,

50].

The present pilot study was implemented with the participation of 78 SE students of the Prefecture of Larissa, aged 17 years, and aimed to investigate the effectiveness of an innovative educational intervention both in understanding complex quantum concepts and in enhancing students’ computational thinking. Data collection for this study was carried out in two organised and well-planned phases, which aimed to ensure reliable data capture and adequate hypothesis exploration. In the first phase, we focused on the initial analysis and preparation of students through a theoretical lecture on quantum concepts. In the second phase, data collection was carried out through a practical application, which allowed for a specific investigation of the topic, ensuring the accuracy and completeness of the results. The current study focuses on the analysis of the perceptions and difficulties faced by secondary school students in understanding basic principles of quantum mechanics and quantum computation, after following a relevant teaching intervention.

Although the students showed particular interest in the subject, many reported that they experienced moderate ease in understanding quantum concepts. This difficulty was mainly attributed to the radical differentiation of quantum logic from the traditional, classical way of thinking that students are familiar with from a young age. The results underline the need for further educational interventions, tailored to students’ needs, to bridge the gap between everyday experience and abstract quantum concepts. Initially, in the first phase of our intervention, many students were alarmed by the title of the presentation on quantum computation, considering it to be a particularly difficult and complex topic. Analysis of the responses indicated that students who considered advanced knowledge of mathematics and physics as necessary to understand the subject matter had greater difficulty in understanding the concepts. In contrast, students who did not consider advanced knowledge to be as important experienced less difficulty in understanding. In addition, students who found the transition from classical to quantum physics easier also found quantum computation easier to understand. These students were more open and willing to engage with the subject in the future. Correlations of the data showed that students’ perceptions of the importance of advanced knowledge significantly influenced their learning experience and future interests. Regarding students’ perceptions of the subject requirements, most students believed that advanced mathematics and physics were necessary to understand quantum computing. This perception made them more vulnerable to the belief that their lack of this knowledge was a barrier to their understanding. The thematic analysis of the data highlighted the main difficulties that students encountered, such as understanding quantum gates and quantum cryptography, and highlighted the need for clarity and additional support for these concepts. Despite the initial difficulties, in the second phase of our activity, students showed strikingly more positive attitudes after the presentation and practical application of a game about quantum concepts. In particular, the application of the game, which presented the basic quantum concepts in a simple and entertaining way, had a positive effect. Immediately after the educational intervention, most students found the topic of quantum computing interesting and understood the basic concepts to a satisfactory degree.

Remarkably, students who found the transition from classical to quantum physics easier found quantum computation easier. This observation suggests that using a playful and fun way of presenting quantum concepts can positively influence and facilitate learning, as well as enhance student engagement and interest. The results of the study showed that, through appropriate teaching practices, students were able to understand basic principles of quantum physics in an accessible and clear way, even without prior knowledge of physics or mathematics. This playful methodology fosters the development of a less deterministic way of thinking, encouraging interdisciplinary problem solving and promoting active student participation. At the same time, it fosters skills necessary for understanding and exploiting quantum technology, and enhances quantum literacy, adapting learning to the individual needs of each student.

This approach strengthens memory, enhances collaboration and motivates learning engagement, providing a context in which students develop their critical and computational thinking in a creative and inspiring way. Moreover, it helps them to transcend stereotypical perceptions and traditional ways of thinking about physics and computers, paving the way to understanding the exciting world of quantum computing through a new, engaging perspective. A related work [

50] is recorded in the available literature, which, although not conducted with SE students, was conducted with first-year university students and is in substantial agreement with the results of our work. This study followed a similar approach, which was carried out in two phases: a theoretical lecture and a practical application to introduce quantum concepts. At the end of these phases, students were asked to complete a questionnaire, which showed an increase in both interest and understanding of the basic principles of quantum mechanics. The findings of this survey are consistent with the results of our study, pointing to a significant increase in student interest and understanding of the scientific field of quantum mechanics. These findings reinforce the importance and potential of such pedagogical methods in education, confirming the value of using interactive and innovative approaches through quantum computing in teaching complex scientific concepts.

Our present research demonstrates that the understanding of quantum concepts by secondary school students can be achieved through an alternative and experiential approach, such as the use of quantum computing games. Its integration into the teaching process provides students with a practical and enjoyable way to approach complex concepts, making the learning experience more interesting and effective. Through interactive activities and the use of educational digital tools, students gain the ability to design quantum algorithms, build quantum gateways and approach the field of quantum computing in a tangible, accessible and creative way. Quantum literacy, as an innovative educational strategy, can serve as a starting point for the development of structured educational initiatives that enhance cognitive access to the subject. Through this approach, it becomes possible to upgrade the educational process with regard to quantum technologies, contributing to their demystification on the one hand and supporting a qualitative and meaningful understanding of the subject matter by a wider range of learners on the other. It is therefore clear that targeted investment in education and training in quantum technologies is needed. This need is accompanied by the challenge of developing effective methodologies capable of integrating the potential of quantum computational thinking into educational practice, ultimately contributing to the formation of a more educated and technologically aware population. It should be noted, however, that the study was conducted exclusively in the region of Larissa, Greece, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader national or international student populations. Future studies involving diverse geographic and cultural settings are needed to validate and extend these results.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

Quantum computing and quantum technologies in general are emerging as one of the most revolutionary and innovative scientific fields of the modern era, with enormous potential to shape the future of knowledge and technology. In this context, linking the educational process with the latest developments in science becomes necessary in order to ensure that students are able to meet the demands of a rapidly evolving world. Education must recognise and integrate modern pedagogical approaches, cultivating skills that will enable students to deal creatively and critically with the complex problems of tomorrow. This study highlighted the importance of quantum computing through playful teaching practices in the approach to QP.

This work showed that, even without prior knowledge, students can understand and experiment with quantum concepts, enhancing their skills and developing critical thinking. Through the use of creative and computational tools, students not only understood the basic principles of quantum physics, but also enhanced their ability to practically apply quantum technologies, developing an interdisciplinary approach to learning. The study clearly shows that integrating quantum literacy into education is no longer just an option, but an imperative. At a time when technological developments are reshaping knowledge and innovation, education must adapt to these new realities by providing students with the tools to understand and exploit the next generations of technologies. Applying quantum physics and computing through collaborative learning and fostering creativity builds the conditions for meaningful understanding and prepares students for the future of technological and scientific developments. This methodology is not just an educational proposal, but a strategy for the transformation of education, with a view to dynamic participation in the challenges of the next era.

In conclusion, this paper can serve as a valuable guide for the educational community and inspire other stakeholders, paving the way for the renaissance of education and the effective preparation of students for the era of the quantum revolution.

Future work is twofold. First, an attempt will be made to teach students QC with the help of artificial intelligence after a lecture on its proper use. At the same time, corresponding lectures will be given with the classical teaching method and the effectiveness of the two methods will be compared. Second, the development of an online game with two opposing players using several quantum gates and trying to change their classical way of thinking into a quantum one. Alice in Wonderland is the central idea of the second project and a model has already been designed but not yet implemented.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the teachers and students of the secondary schools: Larissa Experimental High School, Falani General High School, and Bakoyannis Private School for their valuable assistance in conducting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| SE |

Secondary Education |

| QP |

Quantum Phyicics |

| QC |

Quantum Computing |

| QL |

Quantum Literacy |

| QIST |

Quantum Information Science and Technology |

| QKD |

Quantum Key Distribution |

References

- A. Matuschak; M. Nielsen How can we develop transformative tools for thought? Available online: https://numinous.productions/ttft/ (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- QuanTime National Q-12 Education Partnership. Available online: https://q12education.org/quantime (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Ilias K. Savvas; Maria Sabani. Quantum Computing: From Theory to Practice, Publisher: Tziolas Thessaloniki, Greece, 2022; in Greek.

- J. P. Dowling; G. J. Milburn. Quantum technology: the second quantum revolution. JPhilos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2003, 361, 1655–1674.

- C. Hughes et al. Assessing the needs of the quantum industry. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.03601 (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- E. Gibney. Quantum gold rush: the private funding pouring into quantum start-ups. Nature 2019, 574, 22–24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N. Skult; J. Smed. The marriage of quantum computing and interactive storytelling, in Games and Narrative: Theory and Practice Springer 2022, 574(7776), 191–206.

- B. Victor Explorable Explanations. Available online: http://worrydream.com/ExplorableExplanations (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- IEEE IEEE Quantum Education. Available online: https://ed.quantum.ieee.org (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- F. S. Khan et al. Quantum games: a review of the history, current state, and interpretation. Quantum Inf. Process 2018, 17, 1–42.

- S. Phoenix; F. Khan; and B. Teklu. Preferences in quantum games. Phys. Lett. A 2020, 384(15), 126299. [CrossRef]

- QuTE4E Quantum Technologies Education for Everyone. Available online: https://qtedu.eu/project/quantum-technologies-education-everyone (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- P. Knight; and I. Walmsley. UK national quantum technology programme. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2019, 4(4), 040502. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Raymer; and C. Monroe. The US National quantum initiative. Quantum Sci.Technol. 2019, 4(2), 020504. [CrossRef]

- T. Lobato; and I.M. Greca. Introduction of Quantum Theory Content into High School Curricula-Analysis or the Introduction Theory Content into High Scholl Physics Curricula High School, Science & Education (Bauru) 2005, 11, 119.

- LManinder Kaur; and Araceli Venegas-Gomez. Defining the quantum workforce landscape: a review of global quantum education initiatives Journal of Optical Engineering 2022, 61(8).

- G. Kalkanis; P. Hadzisaki; and D. Stavrou. An instructional model for a radical conceptual change towards quantum mechanics concepts. Sci. Educ. 2003, 87, 257.

- Aspasia, V. Oikonomou; and Ilias K. Savvas. Quantum Legacy in the Hands of Secondary School Students to Implement Quantum Literacy through Quantum Computing IEEE EDUCON: Global Engineering Education Conference 2025.

- Laurentiu Nitaa et al. The challenge and opportunities of quantum literacy for future education and transdisciplinary problem-solving. J. of Research in Science & Technological Education 2023, 41, 564–580.

- H. K. E. Stadermann; E. van den Berg; and M. J. Goedhart. Analysis of secondary school quantum physics curricula of 15 different countries: Different perspectives on a challenging topic J. of Phys. Rev. Phys. Educ. Res. 2019, 15(1).

- K. Krijtenburg-Lewerissa et al. Insights into teaching quantum mechanics in secondary and lower undergraduate education arXiv: Physics Education 2017, 13, 010109.

- C. Singh. Student understanding of quantum mechanics. Am. J. Phys. 2001, 69(8), 885–895. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Styer. Common misconceptions regarding quantum mechanics. Am. J. Phys. 1996, 64(1), 31–34. [CrossRef]

-

J. Teaching in Higher Education 2001, 4, 519–526.

- D. Kaiser. How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture, and the Quantum Revival Reprint ed., Norton & Company, New York, 2012.

- S.E. Economou; T. Rudolph; and E. Barnes. Teaching quantum information science to high-school and early undergraduate students arXiv: Physics Education, 2020. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.07874 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Zeki, C. Seskir et al. Quantum games and interactive tools for quantum technologies outreach and education Optical Engineering, 61(8) 2022.

- European Union. Digital literacy in the EU: An overview. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/en/publications/datastories/digital-literacy-eu-overview (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- B. W. Becker. Information Literacy in the Digital Age: Myths and Principles of Digital Literacy School of Information Student Research Journal, 7(2) 2018.

- Nancy Holincheck et al. Assessing the Development of Digital Scientific Literacy With a Computational Evidence-Based Reasoning Tool. Journal of Educational Computing Research 2022, 60, 1796–1817. [CrossRef]

- Hello Quantum. Available online: https://helloquantum.mybluemix.net (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- IBM. IBM Quantum Learning. Available online: https://learning.quantum.ibm.com/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- A. Anupam et al. Particle in a Pox: an experiential environment for learning Quantum Mechanics. IEEE Trans. Edu. 2018, 61, 29–37. [CrossRef]

- QPlayLearn. Q from of A to Z. Available online: https://qplaylearn.com (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- P. Migdal et al. Visualizing quantum mechanics in an interactive simulation – Virtual Lab by Quantum Fly-trap Opt. Eng., 61(8) 2022.

- P. Migdal and P. Cochin. Quantum Tensors – an NPM package for sparse matrix operations for quantum information and computing. Available online: https://github.com/Quantum-Flytrap/quantum-tensors (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- L. Nita. et al. Inclusive for quantum computing supporting the aims of quantum literacy using the puzzle game Quantum Odyssey. arXiv:2106.07077 (2021).

- ScienceAtHome. Citizen science games. Available online: https://www.scienceathome.org (accessed on 22 January 2023).

- B.R. La Cour et al. Citizen science games. Available online: https://www.vqol.org (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- QWorld QBronze: the introductory level workshop series on the basics of quantum computing and quantum programming. Available online: https://qworld.networkshop-bronze (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Innovation Management Resources The complete guide to organizing a successful Hackathon HackerEarth. Available online: https://www.hackerearth.com/community-hackathons/resources/e books-to-organize-hackathons/ (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- 2014 games Quantum Game Jam. Available online: https://www.finnishgamejam.com/quantumjam2015/games/2014 games/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- J. R. Wootton The history of games for quantum computers. Available online: https://decodoku.medium.com/the-history-of-games for-quantum-computers-al (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Innovation Management Resources TThe complete guide to organizing a successful Hackathon HackerEarth. Available online: https://www.hackerearth.com/community-hackathons/resources/e books-to-organize-hackathons/ (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- C. Lazzeroni, S. C. Lazzeroni, S. Malvezzi, and A. Quadri. Teaching science in today’ s society: the case of particle physics for primary schools Universe, 7(6) 2021.

- Maninder Kaur, and Araceli Venegas-Gomez. Defining the quantum workforce landscape: a review of global quantum education initia-tives Journal of Optical Engineering, 61(8) 2022.

- D. Escanez-Exposito et al. QScratch: Introduction to quantum mechanics concepts through block-based programming EPJ Quantum Technology, 12(1), Article 12. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-025-00314-9. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. H. Bennett. Quantum cryptography using any two nonorthogonal states JPhysical Review Letters, 68(21) 21992 3121–3124.

- P. Lietz. Research into Questionnaire Design: A Summary of the Literature. International Journal of Market Research 2010, 52, 249–272. [CrossRef]

- D. Escanez-Exposito et al. QScratch: Introduction to quantum mechanics concepts through block-based programming EPJ 721 Quantum Technology, 12(1) Available online: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-025-00314-9 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).