1. Introduction

In the 20th century, almost 3,500 fermented products which may be divided into around 250 different types became widely available. Fermented foods have long been a mainstay of human diets [

1] and despite modern advancements in food processing, billions of people worldwide continue to consume traditional fermented foods in their daily lives [

2,

3]. These foods not only serve as dietary staples but also hold significant cultural and ritual importance, particularly in regions especially in the Indian subcontinent. In the northeastern states of India, traditional fermented probiotic foods form a substantial part of the daily diet. These include a variety of items made from soybeans, bamboo shoots, fish, meat, vegetables, and leaves etc. [

4]. A small route known as the “BLT corridor,” which runs between Bangladesh and Nepal, and then connects to the northeastern region often referred to as the Seven Sister States serves as a vital connection geographically to the rest of India, yet the region retains its unique cultural identity with its traditional fermented foods playing an essential role in both nutrition and cultural preservation. As a reflection of the long-standing customs that have been passed down through the centuries, the consumption of these fermented foods is deeply ingrained in the local heritage and customs. With roughly 3.1% of India’s overall population northeast states of India makes up 8% of the country’s entire land area, however, about half of India’s biodiversity is found there, making it one of the world’s “biodiversity hotspots” and the country’s most abundant source of plant variety [

5,

6]. The population of northeast India is diversified, with a wide range of ethnic backgrounds. The majority of inhabitants in the state of Manipur, India have been fermenting food for taste enhancement and preservation since ancient times, and they carry these practices with them from one generation to the next. Each fermented food item features a distinct substrate and preparation method, tailored to specific regions. Examples include fermented bamboo shoots, soybean products, fish, fish paste, and various beverages. These foods are widely consumed in Northeast India, especially by the Manipuri community in the Manipur state [

7]. In Northeast India, various ethnic communities consume over 250 types of traditional fermented foods and alcoholic beverages, ranging from well-known to lesser-known varieties [

8]. These include fermented products made from soybean and non-soybean legumes, vegetables (such as gundruk, sinki, anishi, goyang, and miya mikhri), bamboo shoot products (like soibum, mesu, and ekung/hiring), cereals and pulses (such as kinema, bhatootu, marchu, chilra, tungrymbai, and axone/bekang/peruyyan), preserved meats, dairy-based beverages (including kadi, churpa, nudu, Sangom aphamba, and dahi), non-food mixed amylolytic starters, and alcoholic drinks (such as ghanti, jann, and daru) [

9].Various processing technologies are used to convert bulky, indigestible, and difficult to decompose raw materials into more functional appealing foods and beverages with extended shelf lives. This processing enhances the availability and market value of different ethnic foods thereby minimizing waste and promoting food security [

10]. Despite the abundance of literature on fermented foods, a comprehensive review on the nutraceutical potential of fermented foods commonly prepared and consumed in traditional ways by different ethnic communities across the globe of their remains scarce. More comprehensive research into the nutritional and therapeutic benefits of these foods could yield valuable insights and highlight their potential for widespread application.

1.1. Fermented Foods from Northeast India

Several traditional fermented foods are widely available and consumed in the northeastern part of India. One notable way by which food distinguishes one ethnic group from another is by its uses [

11]. The people of northeastern India consume a wide range of fermented foods that are rich in essential nutrients such as proteins, vitamins, carbohydrates, fats, and minerals [

9]. The fermentation processes commonly utilize readily available ingredients like milk, vegetables, fish, soybeans, bamboo, meat, and cereals [

9,

12]. The climate of this region especially temperate, subtropical and tropical climate has a significant impact on the kinds of fermented foods that are produced and sold here [

11]. Some of the most well-known nutritious fermented foods available in this area as shown in table 1

Ziang-Sang/Ziang-dui: Manipur and Nagaland states of India are home to these fermented green vegetable items, which are primarily produced by Naga women and offered for sale in local marketplaces [

13]. Ziang-sang is traditionally prepared during the winter season.

Goyang: The Sherpa people of Sikkim and the Darjeeling hills of India make this fermented beverage from the leaves of a wild plant called maganesaag (Cardamine macrophylla wild) [

13].

Anishi: Originating from Nagaland, India this product is primarily made by the AO tribe using the leaves of

Colocasia sp. (edible yam) [

14].

Soibum/Soidon: These native foods of the States of Manipur are fermented bamboo shoot products. They are consumed as an essential component of Manipuri cuisine and are aware of how people use them in social situations. The nutritional value of bamboo shoots has recently been investigated [

15]. Soibum was added during the nuggets manufacture to enhance their physico-chemical, microbiological, and shelf life [

16].

Mesu: The indigenous fermented bamboo shoots, called mesu are found in the Himalayan regions of Sikkim and the Darjeeling Hills of India. It is only produced from June to September, when bamboo shoots begin to appear [

17].

Ekung/Hirring: The state of Arunachal Pradesh produces fermented foods known as ekung/hirring, a fermented product made from young bamboo shoots [

13].

Miya mikhri: These are the fermented food preparations of the Dimasa tribes of the Assam of the North East India. Miya mikhri can be used with curry or eaten as a pickle [

18].

Ngari: Ngari, an indigenous fermented fish, is consumed by the ancient Manipuri inhabitants of the Manipur states. For many centuries, ethnic groups in Manipur have used preservation methods to uphold their traditional identities. Its manufacture involved the use of fish of the Puntius species, which are also used in the sun-dried Phoubu Nga [

19].

Hawaijar: Hawaijar is a fermented soybean product known for its sticky texture, traditionally made in the state of Manipur, India. The name originates from the words "hawai," which translates to pulses, and "jar," an abbreviation of the term "achar" for pickle [

19]. This dish has been an important part of the diet of the native of this state for several decades, and its preparation and consumption are believed to have originated with the Brahmin community in Manipur.

1Axone, Bekang, and Peruyyan: Axone, Bekang, and Peruyyan are names for fermented soybean dishes that vary among different tribes, all originating from Glycine max. L. Merrill, which refers to soybeans. In Mizoram, it is called bekang, in Nagaland it is referred to as axone (or aakhone), and in Arunachal Pradesh, it is known as peruyyan among the apantansis [

7].

1Hentak: Amblypharyngodan mola, Esomus danricus, Puntius spp., and other dry fish are used to make hentak and vegetables (Colocasia spp.), betelaginous paste is a traditional and well-liked fermented product from the Indian state of Manipur [

19].

Table 1.

Traditional fermented foods from North-East India, including their indigenous substrates, nutritional composition, and nutraceutical advantages. Data sourced from references [

8,

13,

17,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. This table highlights traditional fermented food products commonly consumed in North-East India and includes the type of indigenous substrate used, detailed macronutrient and micronutrient composition, as well as the associated nutraceutical benefits.

Table 1.

Traditional fermented foods from North-East India, including their indigenous substrates, nutritional composition, and nutraceutical advantages. Data sourced from references [

8,

13,

17,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. This table highlights traditional fermented food products commonly consumed in North-East India and includes the type of indigenous substrate used, detailed macronutrient and micronutrient composition, as well as the associated nutraceutical benefits.

| Sl.no. |

Local name |

Indigenous Substrate |

Nutritional Composition |

Nutraceutical potential |

References |

| 1. |

Dahi |

Milk |

Protein content is 22.5%, fat content is 24.5%, carbohydrates make up 48.2%, and the food value is measured at 503.6 kcal per 100 grams. |

This food possesses antioxidant properties. |

[20,21] |

| 2. |

Goyang |

WEPs |

Protein comprises 35.9%, fat makes up 2.1%, carbohydrates constitute 48.9%, and the food value is 357.2 kcal per 100 grams. Additionally, The concentrations of calcium, sodium, and potassium are 92.2, 6.7, and 268.4 mg/100 g, respectively. |

support bone and heart health, managing blood pressure |

[8] |

| 3. |

Hawaijar |

Soybean |

Protein content is 43.9%, fat content is 27.9%, carbohydrates constitute 23.4%, and the food value is 521.2 kcal per 100 grams. Additionally, The concentrations of calcium, sodium, iron, potassium, and zinc are 357.8 mg, 88.7 mg, 92.3 mg, 835.1 mg, and 63.0 mg per 100 grams, respectively. |

This food possesses organoleptic properties. |

[22] |

| 4. |

Hirring |

Bamboo shoot |

Protein content is 33.0%, fat content is 2.7%, carbohydrates make up 49.3%, and the food value is 353.5 kcal per 100 grams. Additionally, calcium is present at 19.3 mg per 100 grams, 3.4 mg of sodium and 272.4 mg of potassium per 100 grams, respectively. |

Properties include antioxidants, anti-cancer, and anti-aging effects |

[23] |

| 5. |

Kinema |

Soybean |

Protein content is 47.7%, fat content is 17.0%, carbohydrates make up 28.1%, and the food value is 454 kcal per 100 grams. Additionally, there are 5129.0 mg of free amino acids and 42618.0 mg of total amino acids per 100 grams. With 432.0 mg of calcium, 27.7 mg of sodium, 17.7 mg of iron, 5.4 mg of manganese, and 4.5 mg of zinc per 100 grams, these elements are present. |

Reduction in cholesterol levels and presence of antioxidant properties. |

[13,24,25] |

| 6. |

Mesu |

Young bamboo shoots |

Fat content is at 2.6%, protein at 27.0%, and carbohydrates at 55.6%, providing 352.4 kcal per 100 grams. It also has 2.8 mg of sodium, 282.6 mg of potassium, and 7.9 mg of calcium per 100 grams. |

weight management, and metabolic wellness |

[17] |

| 7. |

Ngari |

Fish |

The protein content is 34.1%, fat is at 13.2%, and carbohydrates make up 31.6%, resulting in 381.6 kcal per 100 grams of food value. It also has 41.7 mg of calcium, 0.9 mg of iron, 0.8 mg of magnesium, 0.6 mg of manganese, and 1.7 mg of zinc per 100 grams by weight. |

contributes to gut health and immune function, muscle growth, promotes heart and brain health |

[26,27] |

| 8. |

Soibum |

Tender bamboo shoot |

The fat content is 3.2%, protein is at 36.3%, and carbohydrates account for 47.2%, offering 362.8 kcal per 100 grams of food value. Furthermore, per 100 grams, it has 212.1 mg of potassium, 2.9 mg of sodium, and 16.0 mg of calcium. |

helps in detoxification, antioxidants, boosting immunity |

[28,29,30] |

| 9. |

Soidon |

Matured bamboo shoot |

This food's nutritional makeup consists of 46.6 grams of carbohydrates, 37.2 grams of protein, and 3.1 grams of fat per 100 grams, with a total energy value of 363.1 kilocalories. Additionally, it contains 18.5 milligrams of calcium, 3.7 milligrams of sodium, and 245.5 milligrams of potassium. |

weight management, cholesterol control, and immune support |

[30] |

| 10. |

Ziang-sang/ Ziang-dui |

Leaves of mustard |

Per 100 grams, this product has 38.7% protein, 3.2% fat, and 41.2% carbs, providing an energy value of 348.4 kilocalories. It also contains 240.4 milligrams of calcium, 133.7 milligrams of sodium, and 658.4 milligrams of potassium per 100 grams. |

support bone health, reducing inflammation, cancer-protective |

[31] |

| 11. |

Tungrymbai |

Soybean |

This item has 12.8 grams of fiber, 30.2 grams of fat, and 45.9 grams of protein, 212.7 micrograms of carotene, and 200 micrograms of folic acid per 100 grams. |

Ability to acidify, breakdown antinutritional substances, and exhibit antimicrobial properties. |

[32,33,34] |

| 12. |

Hentak |

Fish |

Per 100 grams, this food comprises 32.7% protein, 13.6% fat, and 38.7% carbohydrates, with a total energy content of 408.0 kilocalories. It also contains 38.2 milligrams of calcium, 1.0 milligrams of iron, 1.1 milligrams of magnesium, 1.4 milligrams of manganese, and 3.1 milligrams of zinc. |

enhances digestibility, ` boosts the bioavailability of nutrients. |

[26,27] |

| 13. |

Eup |

Tender bamboo shoot |

The composition of this food per 100 grams includes 33.6% protein, 3.1% fat, and 45.1% carbohydrates, providing an energy value of 342.7 kilocalories. Additionally, it contains 76.9 milligrams of calcium, 3.4 milligrams of sodium, and 181.5 milligrams of potassium. |

Rich in antioxidants, antimicrobial properties, and provides nutritional benefits. |

[23] |

| 14. |

Gundruk |

Leafy vegetables |

This food contains 38.7% protein, 2.1% fat, and 38.3% carbohydrates per 100 grams, providing an energy value of 321.9 kilocalories. It also contains 234.6 milligrams of calcium, 142.2 milligrams of sodium, and 677.6 milligrams of potassium per 100 grams. |

Enhances milk production, acts as a beneficial appetizer, and contains elevated levels of ascorbic acid, lactic acid, and carotene, which possess anti-cancer properties. |

[20,31,35] |

| 15. |

Kargyong |

Meat (yak/ beef/pork) |

This food consists of 16.0% protein, 49.1% fat, and 32.0% carbohydrates per 100 grams, providing a total energy value of 634.5 kilocalories. |

supports muscle growth, boosts energy metabolism, and contributes to immune function and red blood cell formation |

[36] |

2.1. The Health Benefits of Fermented Foods

Microbes are receiving more attention because of the many health benefits associated with the fermentation process. In this regards, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are among the microorganisms that have been studied and investigated the most using enzymes such as peptidase and proteinase, these bacteria orchestrate vitamins, minerals, and nutrients during fermentation and also separate some non-nutrients and generate biologically active peptides. The process of fermentation is well known for being very low in nutritional value and for producing a variety of bioactive peptides that have probiotic, antioxidative, and anti-microbial qualities in addition to other health advantages [

37]. Furthermore, foods that have undergone fermentation improve the foods flavor, digestibility, and medicinal efficacy [

4]. The health benefits of biologically active peptides produced by fermentation-causing bacteria have been extensively studied. Blood pressure has been demonstrated to be hypotensive in response to conjugated linoleic acids (CLA); prebiotic in response to exopolysaccharides; antimicrobial in response to bacteriocins; anti-carcinogenic and antimicrobial in response to sphingolipids; and hypotensive, antioxidant, and opioid antagonistic in response to bioactive peptides [

38]. A study by Sanlier et al., found that fermented foods provide a number of health advantages, including anti-inflammatory, anti-fungal, anti-microbial, anti-atherosclerotic, and antidiabetic effects. Foods that have undergone fermentation are actually more nutrient-dense than those that have not, fermented foods can also be considered healthy foods that have lost some of their nutrients due to the transfer of bacteria and health-promoting metabolites [

39]. A healthy probiotic bacterial culture system can be obtained from a high-quality fermented food. According to research, eating some of these cultures may help people with a number of illnesses, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, lactose intolerance, irritable bowel syndrome, gastroenteritis, diarrhea, cancer, and genitourinary tract infections [

40].

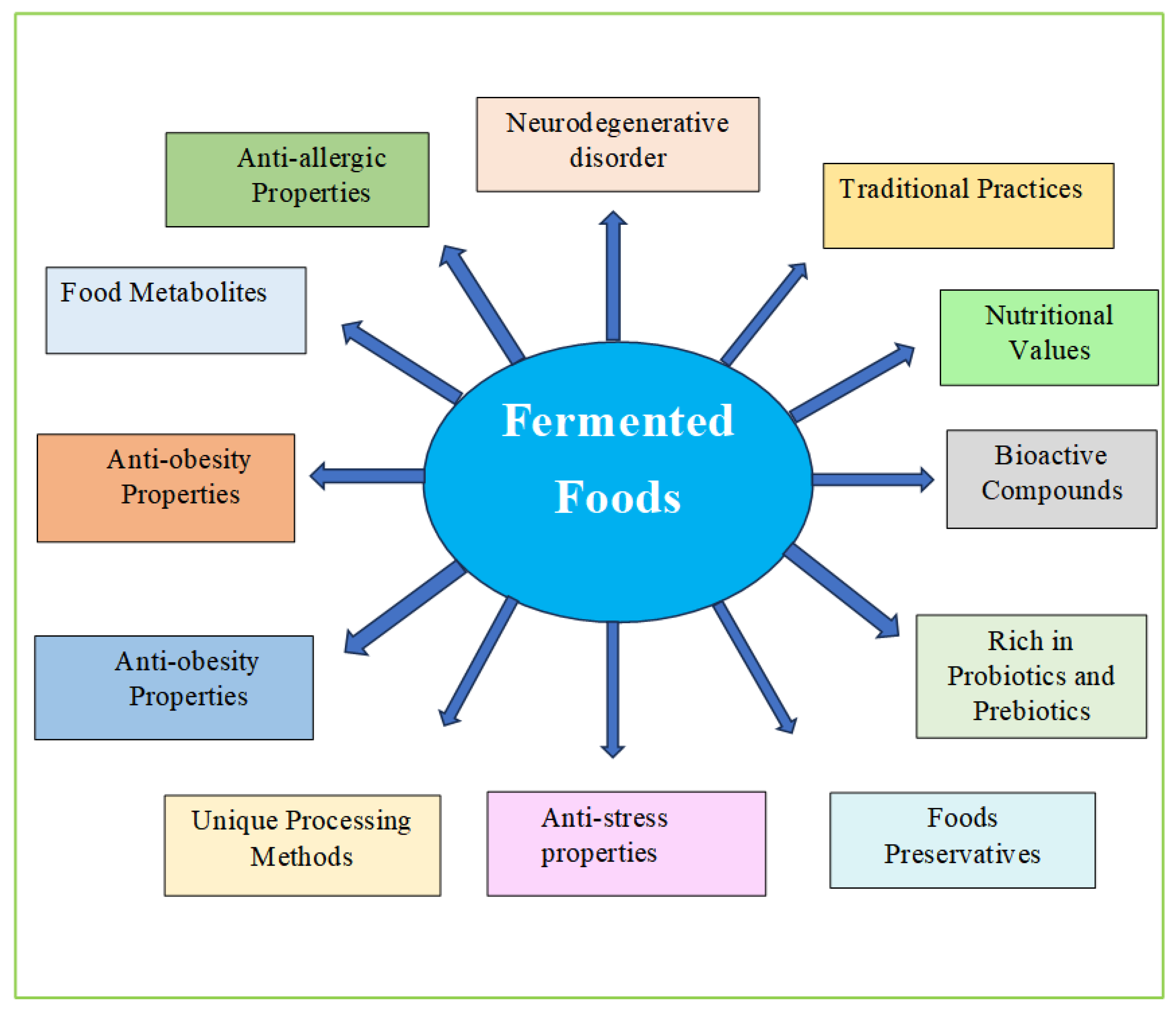

Figure 1.

Health benefits and attributes of fermented foods.

Figure 1.

Health benefits and attributes of fermented foods.

This schematic diagram illustrates the multifaceted benefits of fermented foods, highlighting their role in improving nutritional value, supporting gut health through probiotics and prebiotics, contributing to disease prevention (such as neurodegenerative disorders, obesity, and allergies), and preserving traditional food practices. The unique bioactive compounds and metabolites generated during fermentation also provide anti-stress and food preservation properties.

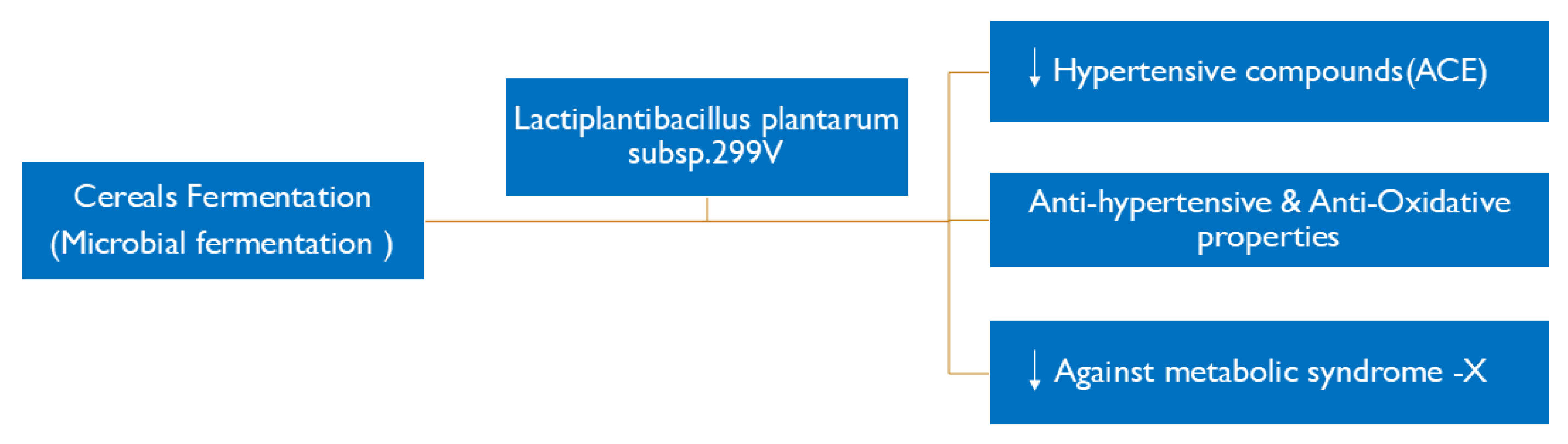

The nutritional makeup of fermented foods protects bacteria against gastrointestinal tract obstacles such as excessive acidity, bile salts, and digestive enzymes. Traditional fermented foods have been linked to a number of health benefits for humans, which are believed to result from the biologically active chemicals produced during microbial fermentation. For example,

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum 299v (previously Lb. plantarum) ferments faba beans and produces antioxidative and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activities. Materials show their peak anti-metabolic syndrome action after three days of fermentation [

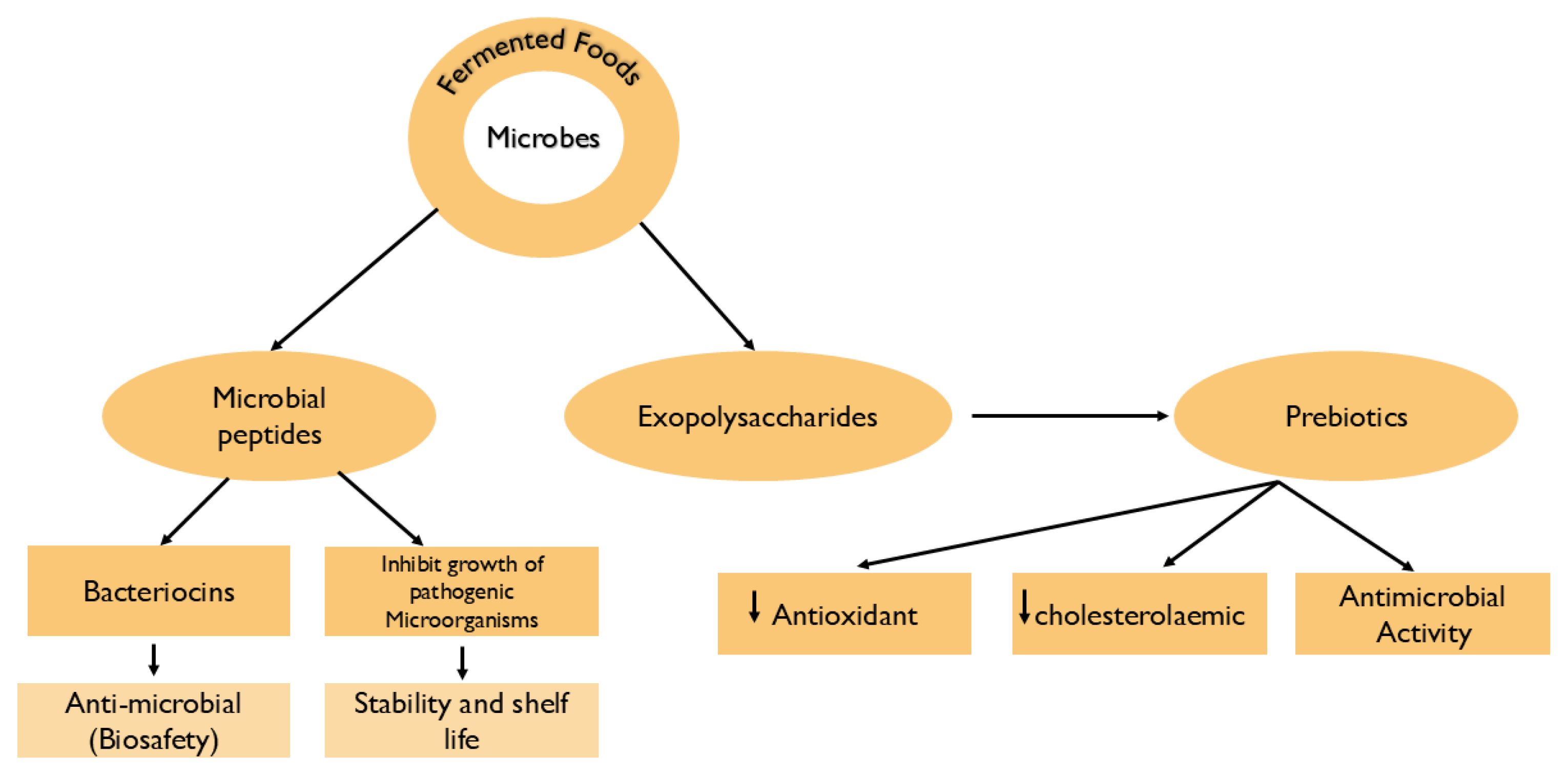

41]. An antimicrobial peptide known as bacteriocins is produced by bacteria in fermented foods and has been connected to biosafety. The stability and shelf life of fermented foods like wiener are increased by these peptides, which prevent harmful microbes from developing [

38]. It has been discovered that microbial enzymes, such as bile-salt hydrolase, offer therapeutic benefits that promote intestinal electrolyte balance, immunological balance, vitality consumption, and intrinsic lipid and cholesterol metabolism [

42] and Exopolysaccharides, which contribute to the food’s quality and flavor, are also produced by microbes in fermented foods. As seen in [

Figure 2] [

43], these microbes are also said to function as prebiotics and have antioxidant, hypocholesterolaemic, and antimicrobial properties (

Figure 2).

2.2. Fermented Foods and Management of Heart Disease (CVD)

Among the most prevalent and serious life-threatening conditions, cardiovascular diseases are among the world’s leading causes of death. By 2030, it is estimated that approximately 23.6 million individuals will be affected worldwide [

44,

45,

46]. Coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, heart failure risk, stroke, and ischemic heart disease are among the ailments that fall under this category [

47,

48]. Additionally, the development of heart disease can be triggered by gut dysbiosis [

49]. The metabolic syndrome of the CVD type may be treated by altering the composition of gut microbes [

50]. Probiotics added to a well-balanced diet have been demonstrated to lower the risk of CVD progression [

51] and combination with a balanced diet, consumption of dairy-fermented foods like cheese, sour milk, and yogurt has been found to be negatively correlated with the onset of cardiovascular disease (CVD). The glycemic index, blood lipid levels, cholesterol concentrations, and blood pressure can all be improved and controlled by the healthful ingredients found in these foods, which explains this [

52]. Consuming fermented dairy products may lower the incidence of CVD, according to a recent review analysis [

53]. Traditional Japanese fermented soybean food natto, made from

Bacillus subtilis, can significantly stop the progression of cardiovascular illnesses and high blood pressure. The potent serine fibrinolytic enzyme nattokinase, which is found in natto, has several health advantages by improving improves blood circulation by breaking down fibrin and its monomers, which in turn reduces blood clotting and prevents cardiovascular diseases [

54]. A traditional fermented milk beverage called kefir has shown promise in treating a number of cardiometabolic disorders, including hypertension, vascular endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance in humans, and decreased ventricular hypertrophy in rats with spontaneous hypertension [

55,

56]. According to studies, kefir has a number of health advantages, such as regulating the vagal/sympathetic nervous system, reducing reactive oxygen species overproduction, blocking angiotensin-converting enzyme activity, producing an anti-inflammatory cytokine profile, and changing the composition of the gut microbiota [

56]. Fermented purple sweet potato yoghurt combined with probiotic-rich diets triggered an anti-apoptotic cascade in hypertensive hearts, preventing hypertension-related cardiac apoptosis [

57] and it also increased the cardiac survival rate. According to reports, fermented milk containing

Lactobacillus (previously

Lactobacillus lactis) was suggested as a way to lower blood pressure caused by hypertension, both systolic and diastolic; as a result, the fermented milk demonstrated antihypertensive benefits [

58]. While some bacteriocins are bacteriostatic, their main action is bactericidal, which makes them useful in the food supply and medical fields. Their area of expertise lies in disrupting the proton motive force on activated membrane vesicles and the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane [

59,

60].

2.3. Anti-Diabetic Properties of Fermented Foods

Blood sugar levels are regularly increased in people with diabetes mellitus. Insulin resistance, a disorder in which cells stop responding to insulin, as they should, is assumed to be the origin of type 2 diabetes. One of the most common disorders is type 2 diabetes, which affects 90-95% of adults. One kind of diabetes known as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is identified by the development of glucose intolerance during or during pregnancy [

61,

62]. The potential anti-diabetic effects of several ingredients in ethnic fermented foods have been the subject of recent research. Red mold rice, a traditional Chinese fermented dish created by inoculating steamed rice with the mold Monascus, may have anti-diabetic effects, according to some research many secondary metabolites, such as monacolin K, monascin (MS), ankaflavin (AK), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), are produced by

Monascus species during fermentation and have several health advantages for people. Red mold rice given to diabetic rats for eight weeks improved insulin production and appeared to improve lipid profiles, according to

in-vivo research [

63] because fermented soybean products contain substances including phytoestrogens, isoflavonoids, and bioactive soy peptides, they have also been linked to anti-diabetic effects. Fermented soybean products are used in many Asian nations. In rat models, plant-based fermented diets such as soy flour, alfalfa meal, and barley sprouts, along with lactic acid bacteria (LAB), show a strong influence of gut microbiota on type 2 diabetes (T2D), resulting in lower blood glucose levels and more active beta cells [

61]. Numerous fermented milk products, including yogurt, have also been investigated for their possible health advantages, especially in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. It has been reported that consuming 244 grams of yogurt per day was linked to an 18% lower risk of type 2 diabetes, according to a meta-analysis that included nine cohort studies [

64].

2.4. Anti-Carcinogenic Properties of Fermented Foods

A chronic illness known as cancer occurs when particular body components show abnormal or unregulated cell proliferation, which can lead to tumors and spread throughout the body. One of the main causes of death in the world today is cancer. Most cancer patients choose to eat foods with anti-cancer characteristics even while cancer chemotherapy is available. These foods could be classic or novel fermented foods that contain probiotic microbes. One of the main areas of research in recent years has been how fermented foods affect stomach cancer.

It has been reported that fermented milk products may have an anti-carcinogenic effect on colorectal malignancies and this defence mechanism is linked to short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are produced during fermentation and control epithelial cell death [

65]. Because it contains probiotic microorganisms and bioactive ingredients such as peptides, organic acids, and exopolysaccharides (EPS), kefir contributes significantly to these positive benefits on cancer prevention [

66]. Interestingly, it has been shown that chemotherapy and skim milk fermented with

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei NTU 101 can effectively prevent tumor growth and metastasis. Additionally, research has shown that fermented foods can offer protection against breast cancer, a condition that is prevalent globally.

2.5. Fermented Foods and Anti-Obesity Properties

Traditional fermented foods may be utilized in place of dietary supplements because of their many bioactive components, which have health benefits. Probiotics found in fermented foods help reduce blood cholesterol, help reduce body weight, boost cellular immunity, ward off infections, are anti-carcinogenic, help prevent osteoporosis and diabetes, reduce obesity, allergies, and atherosclerosis, and help with lactose intolerance [

67]. Overweight and obesity, along with metabolic syndrome, are caused by the body accumulating excessive or abnormal fat, which can be harmful to one’s health [

68] and increased energy expenditure, improper energy usage, altered gut flora, inappropriate eating habits, poor lifestyle choices, decreased physical activity, and a range of environmental factors are all linked to altered metabolic health concerns in obesity [

69].

By improving plasma triglyceride (TG) reactivity, Chongkukjang, a Korean fermented soybean red pepper paste, has been demonstrated to lower the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL when taken daily by obese people. According to available literature, it has been reported that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ2), a gene linked to obesity and important for lipid metabolism, is activated by fermented Chongkukjang [

70,

71]. Furthermore, it has been discovered that giving soy-based probiotics

(B. longum ATCC 15707 and Enterococcus faecium CRL 183) to obese mice improves their immune response and gut microbiota by raising their levels of IL6 and IL10 [

70].

2.6. Gastro Intestitinal Disorder and Fermented Foods

The Roman historian Pliny was the first to highlight the benefits of fermented foods and their health-promoting properties. Additionally, he introduced the concept of treating gastrointestinal diseases with fermented milk [

72]. Numerous harmful disorders frequently impact the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In addition to promoting gut commensal bacteria, fermented meals can improve intestinal permeability and the integrity of the gut barrier [

73]. As a result, they can aid in the treatment of several diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome, atherosclerosis, and colon cancer [

74]. Fermented foods contain lactic acid bacteria, which are beneficial for gastrointestinal disorders and gut microbiota alterations. Those with IBS are especially affected by this [

75].

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei LS2 (formerly known as

Lactobacillus paracasei) is found in Korean kimchi, a popular fermented vegetable dish. It has been shown to enhance myeloperoxidase activity, stimulate cytokine induction, and boost the quantity of neutrophils and macrophages in lamina propria lymphocytes, all of which may have an anti-inflammatory effect [

76]. Studies have shown that kimchi possesses anti-inflammatory and anti-mutagenic properties, which may help prevent gastric cancer, gastrointestinal disorders, functional bowel disease, and H. pylori infections. Consuming kimchi has also been demonstrated to help prevent constipation and diarrhea [

77].

Additionally, it has been demonstrated that fermented rice products can help restore a healthy gut microbiota and prevent a variety of gastrointestinal conditions, including Candida infections, Crohn's disease, irritable bowel syndrome, infectious ulcerative colitis, and duodenal ulcers [

72]. It has been discovered that haria, a traditional fermented rice beverage, offers defense against gastrointestinal problems such acidity, amebiasis, vomiting, diarrhea, and dysentery [

78]. In addition to producing red and white fermented sorghum flour, LAB increases GABA and other phenolic compounds. These enhanced bioactive chemicals were more likely to be absorbed by the intestinal and colonic epithelium [

79]. Consuming miso, a traditional fermented soybean paste from Japan, lowers the incidence of gastrointestinal disorders. This is due to the fact that miso contains aspartate, glutamate, and histidine [

80]. Sourdough is a fermented flour that is beneficial for digestive health and can help people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) reduce their gas production because it contains a high concentration of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and bioactive substances like short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) [

80]. Eating sourdough has been shown to significantly reduce the intensity of symptoms such flatulence, nausea, bloating, stomach discomfort, and stomach volume [

81].

2.7. Fermented Foods and Neurodegenerative Disorders

The human brain is one of the organs that can be impacted by gut bacteria. The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, together known as the gut-brain axis (GBA), facilitated the communication between the gut and central nervous system (CNS). This connection takes place through afferent and efferent autonomic pathways (ANS), which are linked to muscle tissue and the mucosal layer of the gut [

82]. Neurodegenerative disorders including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are influenced by the gut microbiota, which produces a variety of neuroactive chemicals and metabolites that can have both positive and negative effects [

79]. It has been reported that Belly dysbacteriosis has been linked to both AD and PD. The increased

Enterobacteriaceae population in the stomach and the resulting lipopolysaccharide (LPS) aggregation have a neurotoxic nature. Lipopolysaccharides pass through the intestinal walls, entering the bloodstream and affecting various organs, including the brain [

83]. Probiotic bacteria present in related fermented foods may help alleviate gut dysbiosis and could be a potential therapeutic approach for some neurodegenerative diseases. Giving rats the active metabolites from fermented rice made by

Monascus purpureus, a traditional Chinese medicinal food may lessen neurodegeneration and activate anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative processes, according to studies conducted on a rat model of Parkinson’s disease [

84].

2.8. Fermented Foods and Anti-Psychobiotic Properties

Given the importance of the gut microbiota for mental health, cognition, and mental process recognition, there are exciting opportunities for focused microbial control to enhance brain function. The term "psychobiotic" was created to support this theory and refer to any exogenic intermediation that clarifies a bacterially arbitrated influence on the brain [

85,

86]. Probiotics and prebiotics, therefore, have repeatedly shown good results as examples of Psychobiotics in both animal and human research [

53,

87]. The impact of various dietary strategies on the microbiota has also been well studied, and it has been discovered that diet plays a crucial role in determining the composition and activity of the microbiota [

88]. New research indicates that improving culinary customs may alleviate symptoms of depression. Furthermore, thorough studies from many nations and cultures now associate a lower risk of common mental health issues with eating habits that prioritize health [

89,

90,

91,

92]. Current research is also investigating the impact of specific dietary components (e.g., whole fruits, vegetables, or fermented foods), showing potential benefits in modulating microbiome-host interactions, which plays a significant role in the relationship between diet and the microbiota [

93,

94]. Although studying these approaches is crucial for understanding how specific diets influence the gut microbiota and human health, leading to potentially beneficial discoveries, humans typically consume a variety of nutrients in every meal. Examining individual food components may miss the combined benefits that whole nutritional systems can provide for both general health and the diversity and makeup of the microbiota [

95]. One legitimate way to create novel dietetic and psychobiotic treatments is to get proficient in a variety of food techniques. The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, the immune system, and tryptophan metabolism are among the microbiota-related processes that may contribute to the diet-brain relationship, according to animal research [

96,

97], there are still few human studies of this kind. The majority of studies looking at how nutrition affects anxiety, depression, or cognition have not discovered any notable alterations in microbiome integration [

92,

98,

99]. Some medical findings propose that an individual’s ability to enhance psychological well-being or cognition may be influenced by dietary strategies that interact with their microbiome. A two-month intensive nutrition education program that emphasized increasing the intake of dietary fiber, vegetables, and dairy products resulted in an improved microbiota profile with a higher abundance of beneficial microbes like

Bifidobacterium bifidum and a decrease in depressive symptoms, according to a recent study done among obese women [

100]. Additionally, older people who followed the Mediterranean diet more closely for 52 weeks showed gains in both global cognition and episodic memory recall; these improvements were attributed to particular bacterial species that were responsive to the dietary intervention [

101]. To put these early results into a solid experimental framework and to develop therapies that target the human microbiome, more human research is necessary.

Cross-sectional studies have established a robust correlation between stress levels and overall well-being, along with the nutritional value of a healthy diet [

102,

103]. Various research methodologies have integrated nutritional components [

104,

105], while others have concentrated solely on diet or food additives [

106]. Significant reductions in reported stress among participants have been documented, with nutritional interventions effectively alleviating symptoms of distress, particularly in cases of nonclinical depression [

91,

92]. However, the few studies that have been conducted have produced contradictory findings, and little is known about the overall impact of nutritional interventions on perceived stress [

107]. Probiotics and fermented drinks are two examples of microbiota-targeted therapies that have been shown in prior studies to reduce stress levels [

108,

109,

110].

The authors of this study investigated the impact of a psychobiotic diet, which emphasizes consuming more fermented foods and prebiotics, on gut bacterial composition and function as well as psychological outcomes in a sample of healthy adults. Over the course of four weeks, 45 adults were randomized to receive either a psychobiotic diet (n = 24) or a control diet (n = 21). While validated surveys were used to evaluate dietary practices and mental health, shotgun sequencing was used to study the structure and function of the fecal microbiota. Plasma, urine, and fecal samples were also metabolically profiled. The findings showed that self-reported anxiety decreased after following the psychobiotic regimen (32% in the diet group versus 17% in the control group), however this difference was not statistically significant. However, the reductions in reported anxiety were more noticeable for those who followed the regimen more closely. The quantities of 40 particular fecal lipids and urine tryptophan metabolites showed significant changes, whereas the food intervention only slightly altered the composition and activity of the bacteria. Significant improvements in reported anxiety levels among individuals on the psychobiotic diet were associated with higher variability in bacterial composition. These results suggest that dietary strategies, like including items that target the microbiome, may improve people's perceptions of stress. The underlying mechanisms, however, especially the function of gut bacteria, require more research [

88].

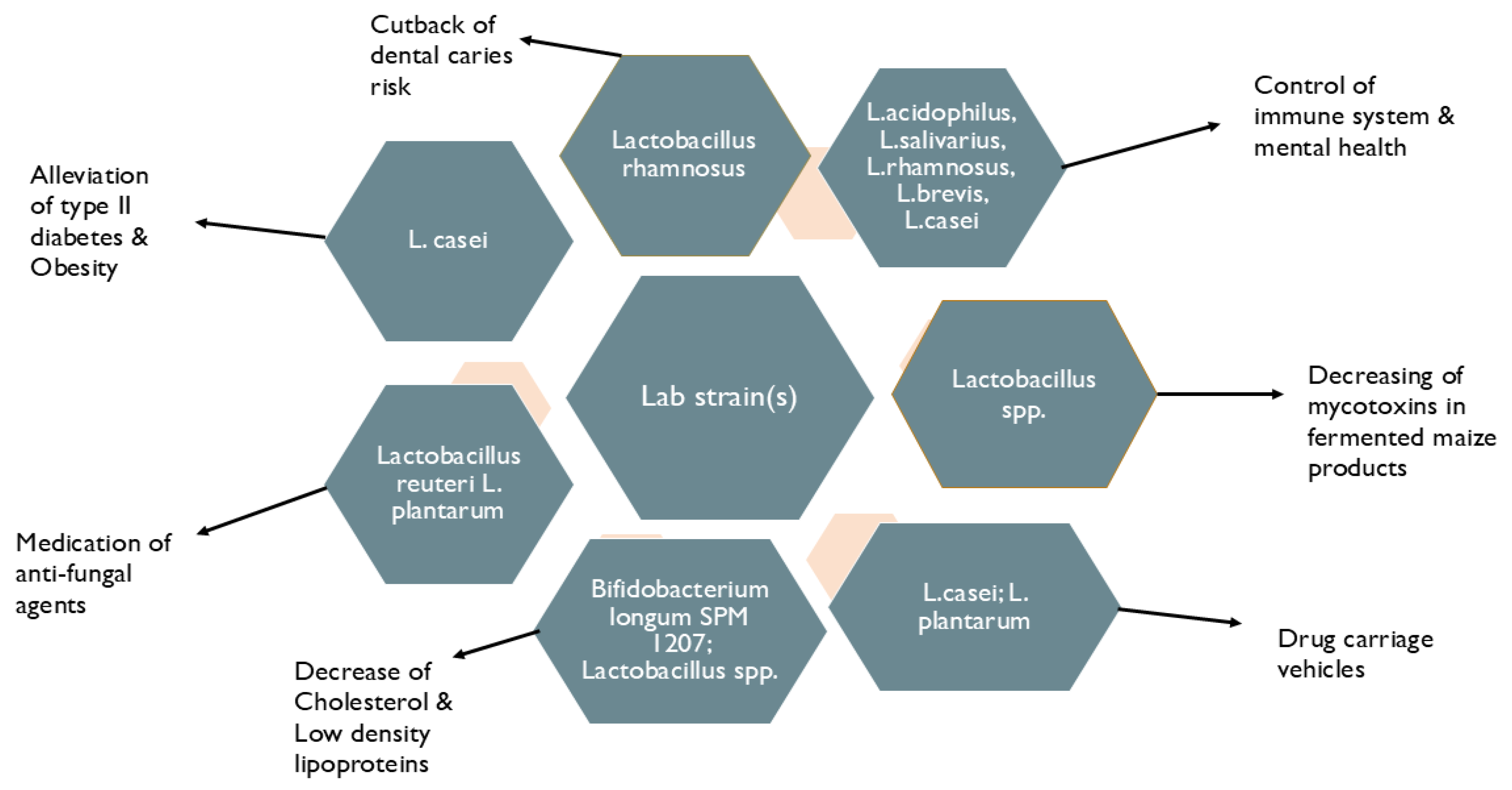

Lactic acid bacteria, or LAB, are important in traditional fermented foods because they enhance the nutritional value, physical attributes, and health advantages that local people can enjoy. Cereal fermentation by LAB efficiently increases the bioavailability of micronutrients while decreasing antinutrients like phytate and tannins. Numerous bacteria found in fermented foods generate antimicrobial substances including bacteriocins and organic acids, which act as natural preservatives and provide nutraceuticals that improve nutrient absorption and nutritional health. Furthermore, LAB are vital probiotics in the human gut microbiota, supporting gastrointestinal health and possibly contributing to the management and prevention of a number of illnesses. Probiotics that contain LAB, particularly those belonging to the Lactobacillus genus, can have a beneficial impact on mental health and immune system performance. Numerous Lactobacillus strains, such as Lactobacillus salivarius, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Lactobacillus brevis, have been identified for their roles in lowering inflammation and boosting innate and adaptive immunity.

Studies indicate that gut microbiota and physiological and mental health factors are related, emphasizing how fermented foods may affect mental and general health by regulating gut microflora activity and generating bioactive compounds with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant qualities, which will ultimately enhance gut barrier function [

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112].

2.9. The Application of Probiotic Microorganisms in the Field of Dentistry

Probiotic bacteria are being researched as a potential treatment for oral infections, and there is compelling evidence supporting this. Existing evidence suggests that probiotics may be highly effective in the prevention and treatment of halitosis, periodontal disease, and dental caries [

113]. One study found that Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG), ATTC, is resistant to several bacteria, including S. mutans, the primary cause of tooth decay [

114]. This finding implies that consuming milk with L. rhamnosus GG may reduce the risk of dental cavities. Further research is required to ascertain the extent to which the different probiotic strains promote oral health, notwithstanding the beneficial effects of probiotics on oral health that these studies have indicated. Probiotics may also be helpful in curing dental cavities, according to recent studies [

115]. However, further investigation is needed to fully understand the role of probiotics in dentistry.

2.10. Preventing Type II Diabetes And Obesity

According to study, giving mice

Lactobacillus casei orally decreased their plasma glucose levels, confirming previous findings that emphasize the critical role probiotic bacteria play in the treatment of insulin-independent diabetes [

116]. In order to improve the host’s health with regard to diabetes and obesity, prebiotics and diets high in probiotics must be combined. In order to prevent and treat these disorders, probiotics can improve insulin sensitivity, lower inflammation, and balance the gut microbiota. Furthermore, by controlling hunger and fat storage, a healthy gut microbiota might enhance metabolic health and potentially aid in weight management.

2.11. Reducing Levels of Cholesterol in the Bloodstream

Dietary cholesterol is not necessary because the body creates plenty of it, however saturated fat is important for heart health. Actually, too much cholesterol in the diet can greatly increase the risk of cardiovascular illnesses like heart attacks and strokes [

117]. Probiotic bacteria have been shown to raise serum cholesterol levels in vitro and might be eliminated in vivo, according to promising research on the subject [

118]. However, these findings remain inconclusive, necessitating further investigation. Furthermore, gastrointestinal discomfort may result from consuming large amounts of probiotics and prebiotics, according to certain research. Investigating whether particular probiotics include genes linked to antibiotic resistance is also crucial because this could affect the safety and effectiveness of long-term use. Understanding the balance of dietary components, including probiotics, is crucial for optimizing heart health and preventing metabolic disorders [

119].

Traditional fermented foods from different regions of the world have been increasingly recognized for their potential health-promoting properties. These foods are not only valued for their taste and preservation benefits but also for the wide range of bioactive compounds they offer. For instance, Japanese fermented products like

Natto and

Miso are rich in antioxidants and have been linked to anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and cholesterol-lowering effects. Similarly, Korean staples such as

Chongkukjang and

Kimchi possess strong antimicrobial, immune-boosting, and neuroprotective properties. Beverages like

Kefir and

Kombucha are associated with benefits for metabolic disorders, heart health, and even viral infections. In Southeast Asia,

Tempeh is noted for its positive impact on brain and gut health, while fermented vegetables like

Sauerkraut support anti-inflammatory responses, especially in digestive conditions such as IBS. Importantly, lesser-known fermented foods from North-East India, such as

Hirring and

Kinema, have also shown promising antioxidant and cholesterol-lowering activities. A summary of these traditional foods and their reported nutraceutical properties is presented in

Table 2.

3.1. Exploring Fermented Foods as Probiotic Sources

A large variety of foods with nutritional and health benefits are produced through food fermentation, according to numerous research and reports. Foods that have undergone a controlled, slow process of microbial cultivation and their enzymatic activity on raw substrates derived from plants or animals are commonly referred to as fermented foods (

Table 3) [

137]. Certain LAB strains are present as fermenting microorganisms and fibers from grains, vegetables, beans, and cereals as a source of prebiotics in foods prepared with substrates sourced from a variety of agricultural sources (

Table 4). Fermented roots, tubers, and green vegetables are easier to digest than raw foods. By having allelopathic action against harmful bacteria and fungal contaminants, microorganisms used in fermentation greatly improve food safety as a preservation technique for storage. By adding flavors, textures, and aromas, microbial cultures give food desirable and valued organoleptic properties [

137].

Include prebiotic dietary fibers, fermenting microorganisms, and postbiotic metabolites, enhancing characteristics such as digestibility, aromas, textures, and taste.

Each distinct sensory profile is created by modifying a variety of factors of the fermentation process, including the development of specific microbial cultures, the selection of raw materials, fruits, or vegetables, and the preservation of optimal fermentation conditions. As seen in

Table 3 and

Table 4, the substrates utilized in food fermentation typically contain a high concentration of prebiotic carbohydrates. Inulin-type fructans are found in considerable amounts in chicory root, Jerusalem artichokes, and cereals [

149]. Other carbohydrates, such as psyllium, galactomannan, lactosucrose, resistant starch, soybean OSs, IMOSs, and XOSs [

150], arabino-OSs, and lactosucrose, have also been shown to have prebiotic effects [

151]. IMOSs are a popular functional food in Asia and are widely used as prebiotics in the European and American functional food industries [

152]. The high dietary fiber content of fermented foods derived from grains, beans, lentils, and vegetables supports the proliferation of fermenting bacteria in the gastrointestinal system [

153]. These substances have a beneficial impact on gut flora when ingested the fibers in fruits, vegetables, and legumes work together to support the growth of the cultures found in fermented meals, which is an additional advantage [

154,

155]. Probiotics create metabolites, which may be a barrier to intestinal protection, by absorbing prebiotics from meals during their extended presence in the gastrointestinal system. According to the research, inulin-type fructans, which are present in fermented foods, caused specific changes in the human gut microbiota [

156]. The inulin included in plant materials used for fermentation has been shown in studies to have a nutraceutical effect on human gut microbiota by promoting the growth of

Bifidobacterium adolescentis and

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [

157]. The prebiotic properties of OSs made from tapioca starch, which is frequently used for food fermentation, have also been confirmed by in vitro experiments [

158].

Comprises oligosaccharides, dietary fibers, metabolites, and nutrients. Cultures, including bacteria and yeast, introduced to initiate fermentation.

3.2. Antifungal Substances and Additional Antimicrobial Agents Derived from Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB)

As the number of antibiotic-resistant microbial species increases and counts to other functions, Lactobacillus reuteri produces reuterin, which has a broad-spectrum bustle against protozoa, fungi, and both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, as well as reuterocyclin, an undesirable charged, hydrophobic, broad-spectrum antibiotic that is limited only to effort in contrast to gram-positive bacteria [

159]. Additionally, bacteriocins, organic acids, and antifungal peptides made by microbes are present in grass silage. L. plantarum isolated from grass silage exhibits antifungal activity by producing organic acids, cyclic dipeptides, and other molecular mass metabolites [

160].

3.3. LABs Serving as Carriers for Distributing Drugs

The accessary function of several Lactobacillus species was examined, and it was found that LAB may play a role as a transporter for oral immunization because of its mucosal adherence, accessary outline, low intrinsic immunogenicity, and GRAS status. across one such study, L. casei and L. plantarum continuously shown high adjuvanticity across a range of experimental model systems [

161]. Quarantining potential probiotic LAB should exhibit the ability to stick to gut epithelial tissue and colonize the GIT by attachment to intestinal epithelial cells. Other than L. rhamnosus, many of the probiotic microflora that are currently available do not colonize their problematic hosts and hence do not stay in the GIT for a significant period of time, which highlights the relative importance of these traits [

162,

163,

164].

3.4. Antimicrobial Action and Protection

Fatty acids, organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, and diacetyl should all form complexes that demonstrate antimicrobial activity in a particular strain of probiotic microflora (

Figure 3) [

148,

164]. Probiotics should not have any negative or contagious effects on the human, but they should disarm bacteria to enhance population health. Additionally, potential probiotics must not contain any transportable antibiotic fight genes and should inhibit the synthesis of biogenic amines from food proteins [

162,

165]. Microbes present in fermented foods generate a range of bioactive substances such as microbial peptides and exopolysaccharides. Microbial peptides, including bacteriocins, contribute to antimicrobial biosafety, enhance food stability, and inhibit pathogenic microorganisms. Exopolysaccharides serve as precursors for prebiotics, which confer multiple health benefits including antioxidant effects, cholesterol-lowering (cholesterolaemic) activity, and antimicrobial properties.

3.5. Distinguishing Probiotics from Fermented Foods

Fermented foods and probiotics are not interchangeable; therefore, one should not take the place of the other. Both are beneficial supplements to a balanced diet. In technical terms, fermented foods are not the same as probiotics. A probiotic is a food or supplement that contains a specific number of living cells of probiotic organisms and known species of beneficial microorganisms that, when taken as directed, provide a health benefit (

Table 5). Probiotics are essentially defined as supplements that have clinical evidence of health benefits when taken in sufficient amounts, whereas fermented foods are part of a meal either as a complete meal or as an accompaniment in some traditional food items [

166].

Fermented food is a product (food or drink) that has been fermented with lactic acid. Lactic acid is produced by the bacteria as a microbial metabolite as they are fed on the sugar and carbohydrates present in the substrate. This process, which is being used today to preserve food, was developed to keep the seasonal agricultural resource from decomposing while being stored for an extended period of time. In some cases, the process introduces vitamins, enzymes, and beneficial bacteria to increase nutritional value. Fermented foods are not always probiotics, and probiotics are not always fermented foods [

137]. Probiotics are described as containing organisms that have been found and health advantages that have been scientifically demonstrated. While some fermented foods may contain live microbes when taken, they may not meet the stringent requirements for them. Certain products may not even include live germs due to operational factors that may have inactivated living bacteria during postproduction and downstream processing. Even while fermented foods and beverages are a fantastic addition to any diet, it can be difficult to determine which particular probiotic strains are present in them [

137,

142,

143,

144,

145,

146,

147,

148].

Even though we are aware that every type of fermented product contains a number of generic categories of bacteria, it is not always possible to identify the specific strains of bacteria present in certain fermented foods. For instance, a variety of

Lactobacilli and

Bifidobacteria are present in yogurt or fermented milk [

167]. Probiotics with identified microbial strains and advantages supported by clinical studies are generally advised; But that doesn't mean fermented foods aren't valuable. Living microorganisms may not be present in the finished product despite the fact that many goods are made using well-characterized and established fermentation cultures. Though these bacteria may have been segregated in some products (fermented barley beer) or inactivated in the final processing step (such as baking sour bread), the fermentation process may have been carried out utilizing specific strains. It is only possible to classify a fermented meal or beverage created with defined cultures as a probiotic product if the bacteria are still living cells when consumed.

Even if the fermented product still includes positive microorganisms for human health, longer fermentation times should have avoided any contamination. An additional consideration is the amount of fermented food or drink needed to provide enough probiotic cultures (colony forming units, or CFU) to contribute to health benefits [

166]. Many fermented foods are known to have positive health effects on consumers. Clinical trials should be conducted to evaluate this association, however, and human intervention studies are necessary to validate these effects. Despite the lack of such clinical research to show the health benefits of fermented foods, specialized foods are nevertheless produced by fermentation and consumed as food flavorings and nutrition in many nations. It's a custom in families [

168].

Not all fermented foods may be classified as probiotics, even though they may contain beneficial nutritional elements (

Table 3). Some foods, however, might be categorized as prospective biotics based on whether their fermented substrate is still whole and acting as a prebiotic and whether live LAB is present when the food is consumed. Although fermented foods like kimchi and kombucha may include live, healthy bacteria, pickles and sourdough are treated in a way that typically kills the microorganisms. It is unknown how much of the product must be ingested to achieve an adequate number of probiotic cultures [

169].

Studies indicate that common foods could be a source of synbiotics for the development of novel functional products [

170]. The science behind the health benefits of consuming fermented foods is complex and multifaceted. Lactic acid is known to help break down other meals that contain a lot of protein since it is produced by lactic acid bacteria during fermentation. Microorganisms that develop over a period of days and weeks digest the vegetables (root, tuber, and leafy) and animal-derived substrates utilized in food fermentations (

Table 4). The nutrients in the veggies are mainly predigested by bacteria and yeast, which enhances absorption because the nutrients in their unfermented state would not normally be sufficiently digested in the gut.

Figure 5.

Benefits to health of different probiotic lab strains used in fermented foods.

Figure 5.

Benefits to health of different probiotic lab strains used in fermented foods.

There is numerous health advantages associated with various strains of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and others. Such strains include L. rhamnosus, L. plantarum, and L. casei are linked with functions such as alleviation of type II diabetes and obesity, dental caries prevention, antifungal activity, cholesterol reduction, drug delivery, and immune and mental health regulation. Additionally, certain LAB strains help decrease mycotoxins in fermented maize products, enhancing food safety and quality.

4. National Dietary Guidelines for Traditional Fermented Foods of Various Ethnicities

The national dietetics program includes national nutritional protocols as a key component. The advice for health and well-being, in the form of guidelines and protocols, is developed by scientists and medical professionals with the support of the most recent data on food consumption and scientific verification [

171]. Actually, they offer recommendations on what to eat, how much to eat (e.g., portions per day), and which food category to choose, and which digestible pattern to pursue. Global nutritional guidelines provide recommendations, including consuming fruit and vegetables every day, opting for unsaturated fats, and adding no more than 5 grams of salt to one's diet each day. National nutritional standards, on the other hand, are specific to the country and particularly to the people of the country that created them; they are linked to and impacted by domestic nutritional and traditional traits, as well as the availability of food items inside the country in question. Furthermore, the national public health classification which varies from nation to nation is being developed and discussed. Dietary guidelines also need to be in line with national traditions and easy for the populace to comprehend.

Many countries, including Bulgaria, South Africa, Australia, India, Oman, Sri Lanka, and Qatar, have already made recommendations for the use of fermented foods in their national food guidelines. Fermented foods are also a traditional and indigenous food in several nations, and they represent an important aspect of their cultural heritage. Citing fermented foods as supporting health is common at the moment. They are composed of health-related modules and can serve as probiotic carriers. Additionally, they can be supported to promote various gut bacteria types and have a positive impact on mental health and other medical disorders. A preliminary review of the fermented food regimen has been proposed as a means of reducing children's cravings for sugary meals [

172]. The preference for sweet foods might be linked to the gut bacteria, and children acquire their gut microbiome early in life.

To completely comprehend the distinct effects of fermented foods on different population groups and, ultimately, to explain their exclusion from national dietary guidelines, more research on randomized, well-ordered, experimental designs is required. For now, there are no succinct scientific foundations for such benefits. There must be evidence of a strong link between fermented foods and health before this dietary class may be gradually included into the locals' culinary traditions and, eventually, into country food principles. To confirm the effect on comfort and health security, it is also crucial to precisely determine the chemical makeup and microbial makeup of fermented foods.

4. Discussion

Fermented foods are integral to global culinary traditions, particularly within ethnic and traditional diets, offering a unique blend of flavors and textures that enhance the dining experience. These foods have transcended mere sustenance to occupy a significant role in health and nutrition, attributed to their potential health benefits and the intricate processes involved in their production. Despite the extensive body of literature surrounding fermented foods, a holistic review focusing specifically on their nutraceutical potential is still lacking. This article aims to fill that gap by examining notable fermented products from Northeast India, such as Hawaijar and Ngari, alongside globally recognized varieties like natto, Chongkukjang, miso, kefir, tempeh, kimchi, kombucha, and sauerkraut.

The helpful probiotic microorganisms found in fermented foods are one of their main characteristics. Gut health is greatly enhanced by these probiotics, which include strains like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. These microbes boost immunological function, nutrition absorption, and digestion by keeping the gut microbiota in balance. Consuming fermented foods high in probiotics has been connected to the prevention and treatment of a number of gastrointestinal conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and even colorectal cancer. A healthy gut microbiome is crucial for general health. Fermented foods are rich in bioactive chemicals that enhance their nutraceutical profile, in addition to their probiotic content. The body uses these bioactive substances, such as phenolic compounds, antioxidants, and metabolites like citric and lactic acid, to counteract dangerous free radicals. Antioxidants, which are present in foods like kimchi and kombucha, are essential for reducing oxidative stress, which is a major cause of chronic illnesses including cancer, heart disease, and neurological conditions. For example, the presence of phenolic chemicals in fermented foods has been associated with decreased blood pressure, decreased inflammation, and decreased cholesterol all of which are important aspects of cardiovascular health. Additionally, the fermentation process increases the bioavailability of vital nutrients, which facilitates improved vitamin and mineral absorption and use. Iron, zinc, copper, as well as vitamins A, D, E, B6, and B12, are among the essential minerals that are frequently abundant in fermented foods. For example, the fermentation of soybeans into products like tempeh and miso significantly increases the availability of these nutrients, making them more accessible for absorption. This increased nutrient density is particularly beneficial for populations at risk of nutrient deficiencies, emphasizing the importance of incorporating fermented foods into daily diets. Recent research has also highlighted the role of fermented foods in managing metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. Regular eating of these meals has been shown to enhance insulin sensitivity and assist control blood sugar levels. The presence of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyrate, which are created when gut bacteria ferment food fibers, is thought to be responsible for this positive effect. SCFAs have been demonstrated to help people with metabolic diseases by lowering inflammation and improving glucose metabolism. Fermented dairy products, such as yogurt and kefir, have also been linked to weight management because they decrease appetite and increase fullness, which helps control obesity. There are still a number of study gaps despite the encouraging health advantages linked to fermented foods. More thorough research is required to assess the long-term impacts of a wide variety of fermented foods on different health outcomes, as the majority of the current literature is on particular fermented products or regional populations. Furthermore, it is unclear exactly how particular probiotic strains and bioactive substances work. Future research should delve deeper into these mechanisms to establish a more complete understanding of how fermented foods can be effectively utilized in disease prevention and management. Moreover, the therapeutic potential of fermented foods as sources for drug discovery remains largely unexplored. Bioactive compounds isolated from these foods could pave the way for new therapeutic agents, particularly for conditions like cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders. Examining how these substances interact molecularly with biological pathways may result in new therapeutic interventions, underscoring the significance of fermented foods in modern health research.

5. Conclusions

There are still significant gaps in the present research landscape despite the encouraging findings. Since most research has focused on particular fermented foods or regional populations, more extensive studies that examine the long-term impacts of various fermented foods on health outcomes are required. To fully utilize the nutraceutical potential of these foods, it is also essential to comprehend the processes by which particular bacterial strains and bioactive chemicals work. The prospect of utilizing fermented foods as a source for drug discovery is another area ripe for exploration. It may be possible to create new therapeutic agents for diseases like cancer, heart disease, and neurological disorders by separating bioactive substances and examining how they interact with cellular pathways. In summary, fermented foods present a valuable intersection between tradition and health science, rich in probiotics, antioxidants, and bioactive compounds that can significantly contribute to disease prevention and health promotion. As interest in natural, functional foods increases, incorporating fermented foods into daily diets, coupled with further research into their therapeutic properties, could advance our understanding and management of chronic diseases, fostering a healthier lifestyle globally.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S. and K.B.S.; methodology, K.S.; software, K.S.; validation, K.S., K.B.S and S.T.D; formal analysis, K.S.; investigation, K.S.; resources, K.S.; data curation, K.S.;S.T.D.;O.I.S.;K.S.D.;B.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B.S; N.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S.; N.S.; visualization, K.B.S.; supervision, K.B.S.; N.S.; project administration, funding acquisition, O.I.S.; K.S.D.; B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author Khalida Shahni gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of Manipur, under the sanctioned file number 23/05/2023 R&D-Biotech/DST/375, which has been instrumental in facilitating the ongoing research work. The author also extends sincere thanks to the Head of the Department of Zoology, Manipur University, for the provision of essential facilities and continuous support throughout the study. Special appreciation is due to the Research Team of the DBT-BUILDER Manipur University Interdisciplinary Life Science Programme for Advanced Research and Education, funded by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), New Delhi, whose valuable guidance greatly contributed to the development and refinement of the research concept.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LAB |

Lactic acid bacteria |

| CLA |

Conjugated linoleic acids |

| IBD |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

| ACE |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| GDM |

Gestational diabetes mellitus |

| SCFAs |

Short-chain fatty acids |

| EPS |

Exopolysaccharides |

| PPARγ2 |

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ |

| GIT |

Gastrointestinal tract |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| ANS |

Autonomic pathways |

| GBA |

Gut-brain axis |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| CFU |

Colony forming units |

References

- Campbell-Platt G. Fermented foods of the world: a dictionary and guide. London: Butterworts; 1987.

- Ray M, Ghosh K, Singh S, Mondal KC. Folk to functional: An explorative overview of rice-based fermented foods and beverages in India. J Ethn Foods. 2016;3(1):5–18. [CrossRef]

- Tamang JP, Holzapfel WH, Shin DH, Felis GE. Editorial: Microbiology of Ethnic Fermented Foods and Alcoholic Beverages of the World. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1377. [CrossRef]

- Jeyaram K, Singh A, Romi W, Devi AR, Singh WM, Dayanithi H, et al. Traditional fermented foods of Manipur. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2009;8(1):115–21.

- Mao AA, Hynniewta TM. Floristic diversity of North East India. J Assam Sci Soc. 2000;41(4):255–66.

- Sarma MK. Biodiversity significance of therapeutically potential plant species indigenous to North East India. J Res Rep Genet. 2019;3. [CrossRef]

- Haokip SW, Shankar K, Sheikh KA. Traditional fermented foods and their health benefits of the North-Eastern States of India. Agric Food e-Newsletter. 2020;2(2):2581–8317.

- Timothy B, Iliyasu AH, Anvikar AR. Bacteriocins of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Their Industrial Application. Curr Top Lact Acid Bact Probiotics. 2021;7:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Tamang JP, Holzapfel WH, Shin DH, Felis GE. Editorial: Microbiology of Ethnic Fermented Foods and Alcoholic Beverages of the World. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1377. [CrossRef]

- Rolle R, Satin M. Basic requirements for the transfer of fermentation technologies to developing countries. Int J Food Microbiol. 2002;75(3):181–7. [CrossRef]

- Keishing SS. Hawaijar – A Fermented Soya of Manipur, India: Review. IOSR J Environ Sci Toxicol Food Technol. 2013;4(2):29–33. [CrossRef]

- Tamang JP, Kailasapathy K, editors. Fermented foods and beverages of the world. Boca Raton: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2010.

- Tamang B, Tamang JP. Traditional knowledge of biopreservation of perishable vegetables and bamboo shoots in Northeast India as food resources. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2009;8(1):89–95.

- Das S, Mishra BK, Hati S. Techno-functional characterization of indigenous Lactobacillus isolates from the traditional fermented foods of Meghalaya, India. Curr Res Food Sci. 2020;3:9–18. [CrossRef]

- Nirmala MJ, Samundeeswari A, Sankar PD. Natural plant resources in anti-cancer therapy – A review. Res Plant Biol. 2011;1(3):1–14.

- Das A, Nath D, Kumari S, Saha R. Effect of fermented bamboo shoot on the quality and shelf life of nuggets prepared from desi spent hen. Vet World. 2013;6(7):419–23. [CrossRef]

- Tamang JP. Microbiology of mesu, a traditional fermented bamboo shoot product. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;29(1):49–58. [CrossRef]

- Sajem AL, Gosai K. Traditional use of medicinal plants by the Jaintia tribes in North Cachar Hills district of Assam, northeast India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:33. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar RK, Bejjanki SK, Roy D, Shitole S, Saha A, Narayan B. Biochemical and microbial characterization of Ngari and Hentaak - traditional fermented fish products of India. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(12):8284–91. [CrossRef]

- Tamang JP, Thapa S. Fermentation dynamics during production of Bhaati Jaanr, a traditional fermented rice beverage of the Eastern Himalayas. Food Biotechnol. 2006;20(3):251–61. [CrossRef]

- Thapa N, Tamang JP. Ethnic fermented foods and beverages of Sikkim and Darjeeling Hills (Gorkhaland Territorial Administration). In: Tamang JP, editor. Ethnic Fermented Foods and Beverages of India: Science History and Culture. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2020. p. 479–537. [CrossRef]

- Jeyaram K, Singh WM, Premarani T, Devi AR, Chanu KS, Talukdar NC, et al. Molecular identification of dominant microflora associated with ‘Hawaijar’ - A traditional fermented soybean (Glycine max (L.)) food of Manipur, India. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;122(3):259–68. [CrossRef]

- Chung JM, Kim HJ, Park GW, Jeong HR, Choi K, Shin CH. Ethnobotanical study on the traditional knowledge of vascular plant resources in South Korea. Korean J Plant Resour. 2016;29(1):62–89. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar PK, Morrison E, Tinggi U, Somerset SM, Craven GS. B-group vitamin and mineral contents of soybeans during kinema production. J Sci Food Agric. 1998;78(4):498–502. [CrossRef]

- Gupta P, Jeswiet J. Effect of temperatures during forming in single point incremental forming. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2018;95:3693–706. [CrossRef]

- Thapa N, Pal J, Tamang JP. Microbial diversity in Ngari, Hentak and Tungtap, fermented fish products of North-East India. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;20(6):599–607. [CrossRef]

- Singh M, Singh GP, Tyagi S, editors. Microbial products: Applications and translational trends. 1st ed. CRC Press; 2023.

- Jeyaram K, Romi W, Singh ThA, Devi AR, Devi SS. Bacterial species associated with traditional starter cultures used for fermented bamboo shoot production in Manipur state of India. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;143(1–2):1–8. [CrossRef]

- Othilakshmi DK, Gayathry DG, Jayalakshmi T. GCMS elucidation of bioactive metabolites from fermented Kombucha tea. Int J Adv Biochem Res. 2024;8(Special Issue 8):458–62. [CrossRef]

- Tamang B, Tamang JP, Schillinger U, Franz CMAP, Gores M, Holzapfel WH. Phenotypic and genotypic identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from ethnic fermented bamboo tender shoots of North East India. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;121(1):35–40. [CrossRef]

- Tamang JP, Tamang B, Schillinger U, Franz CMAP, Gores M, Holzapfel WH. Identification of predominant lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditionally fermented vegetable products of the Eastern Himalayas. Int J Food Microbiol. 2005;105(3):347–56. [CrossRef]

- Kharnaior P, Tamang JP. Microbiome and metabolome in home-made fermented soybean foods of India revealed by metagenome-assembled genomes and metabolomics. Int J Food Microbiol. 2023;407:110417. [CrossRef]

- Agrahar-Murugkar D, Subbulakshmi G. Preparation techniques and nutritive value of fermented foods from the Khasi tribes of Meghalaya. Ecol Food Nutr. 2006;45(1):27–38. [CrossRef]

- Chettri R, Tamang JP. Bacillus species isolated from tungrymbai and bekang, naturally fermented soybean foods of India. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;197:72–6. [CrossRef]

- Tamang JP, Kailasapathy K, editors. Fermented foods and beverages of the world. 1st ed. CRC Press; 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hui YH, Evranuz EÖ, editors. Handbook of animal-based fermented food and beverage technology. 2nd ed. CRC Press; 2016. [CrossRef]

- Doughari JH. Effect of oxidative stress on viability and virulence of environmental Acinetobacter haemolyticus isolates. Sci Res Essays. 2012;7(3):274–82. [CrossRef]

- Şanlier N, Gökcen BB, Sezgin AC. Health benefits of fermented foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59(3):506–27. [CrossRef]

- Saran S, et al. A handbook on high value fermentation products. 1st ed. Wiley; 2019.

- Stanton C, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. Fermented functional foods based on probiotics and their biogenic metabolites. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16(2):198–203. [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk A, Karaś M, Złotek U, Szymanowska U, Baraniak B, Bochnak J. Peptides obtained from fermented faba bean seeds (Vicia faba) as potential inhibitors of an enzyme involved in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. LWT. 2019; 105:306–13. [CrossRef]

- Joyce SA, Gahan CGM. Bile acid modifications at the microbe-host interface: potential for nutraceutical and pharmaceutical interventions in host health. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2016; 7:313–33. [CrossRef]

- Lynch KM, Zannini E, Coffey A, Arendt EK. Lactic acid bacteria exopolysaccharides in foods and beverages: isolation, properties, characterization, and health benefits. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2018; 9:155–76. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135. [CrossRef]

- Venkitachalam L, Wang K, Porath A, Corbalan R, Hirsch AT, Cohen DJ, et al. Global variation in the prevalence of elevated cholesterol in outpatients with established vascular disease or 3 cardiovascular risk factors according to national indices of economic development and health system performance. Circulation.2012;125:1858–69. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Geneva: WHO; 2011.

- Anandharaj M, Sivasankari B, Parveen Rani R. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on hypercholesterolemia: a review. Chin J Biol. 2014; 2014:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Drozdz D, Kawecka-Jaszcz K. Cardiovascular changes during chronic hypertensive states. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014; 29:1507–16. [CrossRef]

- Jin M, Qian Z, Yin J, Xu W, Zhou X. The role of intestinal microbiota in cardiovascular disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2019; 23:2343–50. [CrossRef]

- Thushara RM, Gangadaran S, Solati Z, Moghadasian MH. Cardiovascular benefits of probiotics: a review of experimental and clinical studies. Food Funct. 2016; 7:632–42. [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl L, Boeing H, Stelmach-Mardas M, Gottschald M, Dietrich S, Hoffmann G, et al. Dietary supplements and risk of cause-specific death, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of primary prevention trials. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:27–39. [CrossRef]

- Buziau AM, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Geleijnse JM, Mishra GD. Total fermented dairy food intake is inversely associated with cardiovascular disease risk in women. J Nutr. 2019;149:1797–80https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxz128.

- Zhang K, Chen X, Zhang L, Deng Z. Fermented dairy foods intake and risk of cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60:1189–94. [CrossRef]

- Lee B-H, Lai Y-S, Wu S-C. Antioxidation, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition activity, nattokinase, and antihypertension of Bacillus subtilis (natto)-fermented pigeon pea. J Food Drug Anal. 2015;23:750–7. [CrossRef]

- Friques AGF, Arpini CM, Kalil IC, Gava AL, Leal MA, Porto ML, et al. Chronic administration of the probiotic kefir improves the endothelial function in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Transl Med. 2015;13:390. [CrossRef]

- Pimenta FS, Luaces-Regueira M, Ton AM, Campagnaro BP, Campos-Toimil M, Pereira TM, et al. Mechanisms of action of kefir in chronic cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;48:1901–14. [CrossRef]

- Lin P-P, Hsieh Y-M, Kuo W-W, Lin Y-M, Yeh Y-L, Lin C-C, et al. Probiotic-fermented purple sweet potato yogurt activates compensatory IGF-IR/PI3K/Akt survival pathways and attenuates cardiac apoptosis in the hearts of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:1319–28. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Figueroa JC, González-Córdova AF, Astiazaran-García H, Vallejo-Cordoba B. Hypotensive and heart rate-lowering effects in rats receiving milk fermented by specific Lactococcus lactis strains. Br J Nutr. 2013;109:827–33. [CrossRef]