The Role of D-Amino Acids in Stress Signaling and Defense Responses in Nature

Microbial colonies are known to convert L-amino acids to D-amino acids as a primary defense mechanism against invasive species and harsh environments. Enzymes that convert L-amino acids to D-amino acids mainly exist in lower life forms such as fungi, bacteria and lower plants [

2] like mosses and green algae. D-amino acids are known to inhibit biofilm formation [

3] and quorum sensing, a process in which hostile bacterial colonies coordinate their biofilm formation. Bacterial cell walls and plastids in moss and angiosperms also use simple D-amino acids such as D-alanine, D-glutamate, and D-aspartate as building blocks of peptidoglycan proteins that are resistant to enzymatic breakdown. Biochemical reactions involving D-amino acids in plants could be viewed as remnants of cyanobacterial metabolism that reflect ancestral peptidoglycan chemistry. Other than their role in building defensive peptidoglycans, D-amino acids seem to be of little anabolic value in plants. D-amino acids reportedly constitute on average about 0.7% of the plant’s total amino acid content [

4] so it is reasonable to regard them mainly as xenobiotic and signaling compounds and not as an essential source of organic nitrogen.

The Plantae and Fungi kingdoms utilize D-amino acids as stress signals and defense mechanisms by harming the predator’s nervous system. For instance, ergot fungi and seeds of morning glories naturally produce D-Lysergic acid, the amino acid precursor humans use to make the psychedelic drug LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide). LSD’s hallucinogenic effect on the nervous system could be related to the source plant’s D-amino acid neurotoxic stress signal and defense strategy against herbivores.

In some aquatic invertebrates, D-alanine levels increase under osmotic (high salinity) or anaerobic stress, suggesting D-amino acids can have a metabolic role that signals ecological stress. Some amphibians and invertebrates also use D-amino acids in their toxic defense systems, for example by corrupting the predator’s RNAs [

5] and protein translation processes. Venoms from spiders contain D-amino acids which are used in manufacturing antibiotics and ion channel blockers. Frogs, in their skin secretions, produce peptides containing D-amino acids, often with opioid [

6] or antimicrobial properties. Neurotoxic peptides in snail venom, called conotoxins, which disrupt neuromuscular transmissions, contain D-tryptophan or D-leucine [

7] and are fatal to fish and in high doses to mammals. Conotoxins are used, in small doses, in pharmaceutical analgesics for numbing and relieving pain.

D-amino acid peptides are also shown [

8] to disrupt the binding of natural peptides to heat shock proteins which function as molecular chaperones that prevent protein misfolding and aggregations during environmentally stressful conditions.

In mammals, D-forms of simple amino acids such as glutamic, serine, alanine and aspartic are utilized in small concentrations as agonists to excitatory glutamate receptors in the central nervous system. When overactivated, these receptors are associated with neurotoxicity in the brain, inflammation and damage of the spinal cord, dyskinesias, Parkinson’s disease, [

9] demyelinating diseases [

10] such as multiple sclerosis (MS), transverse myelitis and polio. The excitatory function of D-amino acids in the mammalian nervous system points out to their putative function as both responders to stress stimuli and activators of stress response.

D-Amino Acids in Food Chains: From Soil to Plants, Animals and Humans

While plants mostly lack enzymes to synthesize or metabolize D-amino acids, bacterial broad spectrum racemases and Dextrorotatory amino acid aminotransferases can convert L-amino acids to D-amino acids when subjected to biotic or abiotic stressors such as heat, high pH or salinity, anaerobic conditions, UV or microwave radiations, oxidative stress and free radicals (high Eh), and chemicals like aldehydes formed from microbial or enzymatic degradation of pesticides. As a result, high concentrations of D-amino acids in soil often indicate high stress conditions and decomposition of bacterial cell walls, synthetic pesticides, antibiotics and veterinary medicine leaching into agricultural soils via wastewater irrigation or animal manure. Because the decomposition of insects, plant residues and worms mainly produces L-amino acids, a high ratio of D- to L-amino acids in the soil correlates with a high density of stressed or dying microbes in necromass composition.

Generally, D-amino acids such as D-serine, D-alanine and D-tyrosine are mineralized at slower rates compared to the corresponding L-enantiomers and thus inhibit plant growth [

11] and are considered phytotoxins when they overwhelm L-amino acids. Commensal plant microbiomes have a limited ability to metabolize toxic loads of D-amino acids into non-toxic products using D-amino acid oxidase (DAO).

In the Animalia kingdom, although simpler life forms like fruit flies seem to have formed symbiotic relationships with microbes that produce D-amino acids, mammals such as humans, have a limited capacity in metabolizing or even recognizing D-amino acids. The ability of viruses such as Bacillus anthracis that use D-amino acids in their capsules to evade mammalian immune systems is capitalized in new vaccine [

12] developments. Denatured peptides synthesized from D-amino acids [

13] which resist breakdown in human serum and gastric acid, and bypass the body’s innate immune system are also being researched as artificial T-cell immunogens in new vaccines. These same features of D-amino acid peptides could also activate autoimmune reactions, as explained later in this paper. Generally-speaking, in mammals, as in plants, the D-enantiomers of essential amino acids are utilised at very low levels [

14] and when in excess, mark pathological environmental stress and act as inhibitors of cellular growth and metabolism.

Mutualistic gut bacteria (via fermentation) and some brain neurons can produce simple D-amino acids in free form and small quantities, in the gut as bactericides against pathogenic invasive microbes, and in the central nervous system as excitatory (stress) signaling molecules via NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptors. Amino acid racemase and oxidases in the human brain, kidney, heart [

15] and liver, and broad-spectrum racemases in gut bacteria can modulate D-amino acid signaling [

16] and prevent accumulation of D-amino acids that can result in apoptosis and programmed cell death.

Foods fermented with Lactic acid bacteria produce L-amino acids and safe low levels of D-lactates [

17], which can be metabolized by commensal lactic-acid gut bacteria. Other exogenous free D-amino acids from plant, animal or synthetic/processed sources, unlike D-amino acids produced by commensal bacteria, can challenge the endogenous mammalian D-amino acid oxidase system. Although we have limited data [

18] on the effect of long-term consumption of processed D-amino acid proteins on the human organism, researchers have shown [

19] that even a minor degree of racemisation to D-amino acids in food proteins can result in a major decrease in their proteolytic digestibility and, as discussed later, in allergic reactions and autoimmunity. Also, when overloaded with D-amino acids, the liver may become deficient in L-cysteine, which is required to make glutathione, a powerful antioxidant that metabolizes toxic loads of D-amino acids and alcohol metabolites like acetaldehyde.

High concentrations of D-lactate can also form as a by-product of hypoxic (oxygen-deprived), stressed and dysfunctional cellular metabolic pathways that lead to conditions such as diabetes and hyperglycemia. Studies have shown that even trauma, like gunshot or burn injuries, [

20] can result in elevated endotoxic levels of serum D-lactate.

A Novel Hypothesis: D-amino Acids as Metabolic Switches in Plants and Humans

As their front-line response to foliar and root stressors, plants deploy phytochemicals such as salicylic acid, abscisic acid and jasmonic acid, which initiate crosstalk signaling to coordinate defense responses, osmoregulation and antioxidant (reactive oxygen species/ROS) homeostasis, impacting apoplastic and rhizosphere pH and redox potential (Eh). These hormonal responses to xenobiotic stresses originating outside the ecological biome are shown to be initiated and tightly regulated by microbial colonies [

21], which, as shown earlier, primarily use D-amino acids in their own stress response. So it can be hypothesized that microbial D-amino acids play an interkingdom role in modulating a plant's redox signaling networks, cellular Eh–pH and response to environmental conditions that affect pest or pathogen-host interactions [

1].

In humans, research data also underscore [

22] the metabolic crosstalk between the gut microbiota and D-amino acids. The expression of D-amino acid oxidase enzymes in leukocytes (white blood cells) also indicates the ability of the human immune system to detect and neutralize D-amino acids as microbial stress signals.

The novel hypothesis shared in this paper proposes microbial D-amino acids as evolutionarily-conserved interkingdom stress signals and metabolic switches that allow plants and animals to exploit lower life forms such as soil or gut microbiota as their front-line ecological microsensors. This hypothesis is supported by the endosymbiotic theory [

23], which postulates the bacterial evolutionary origin of cellular respiration and immune cells. Given the conserved prokaryotic biochemistry of metabolic organelles and immune cells, they are evolutionarily privileged to receive and decode D-amino acids as xenobiotic stress signals from their bacterial ancestors that act as ecological microbiosensors.

Furthermore, the fact that only with the help of commensal microbiomes and enzymes, plants and humans can metabolize D-amino acids and peptides, slowly and in small doses, may be indicative of the role of D-amino acids as interkingdom messengers of ecological stress.

Conversely, homochiral L-amino acids are essential in orchestrating immune/defense systems and the efficiency and directionality of metabolic cycles (flow of electrons) in plants and humans.

To maintain organism-level homeostasis in response to stressful conditions signaled by microbial D-amino acids, plants and humans deploy, in a similar and sometimes coordinated fashion [

21], homochiral L-amino acid-containing hormones, neuropeptides and phytochemicals such as auxin (plants), serotonin/phytoserotonin and melatonin that regulate metabolic and physiological functions like growth, dormancy and circadian/seasonal rhythms. Higher life forms also rely heavily on L-amino acids like L-Cysteine, a precursor to many vitamins and antioxidants like glutathione, for adaptation to oxidative stress and bacterial redox signaling.

In addition, for optimized light-harvesting and metabolic adaptation to changing seasons and levels of oxidative stress, humans have evolved other neuropeptides like dopamine, hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, and pigments such as melanin, and plants have evolved phytochemicals such as salicylates, tocopherols (Vitamin E), flavonoids and anthocyanins. These protective plant phytonutrients seem to be also involved in interspecies hormesis (xenohormesis), which means activating and optimizing human stress responses. The majority of stress-sensitive metabolic hormones and xenohormetic phytonutrients, as well as light-harvesting and mitochondrial complexes and cytochromes, use homochiral L-amino acids such as L-phenylalanine, L-tyrosine, and L-tryptophan synthesized in the shikimate pathway (which pesticides like glyphosate can block.) [

24]

Support by Quantum Physics and Thermodynamics

Higher forms of life are maintained by metabolic cycles that use light and oxygen to extract energy from the living organism’s ecosystem. Krebs and photosynthetic cycles rely on an “orderly and directional flow of electrons and protons” inside living cells in order to extract energy (ATP) from organic matter, water, oxygen and light. Thermodynamically, the ability of living organisms to impose order and organization over chaos is expressed as Gibbs Free Energy, a measure of vitality and work potential that increases with energy harvesting but decreases with chaos and temperature.

In Quantum physics, the efficiency of this energy-harvesting process in living cells, expressed as “quantum yield,” depends on the orderly flow of electrons inside organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts, which in turn depends on L-amino acids and peptides because the chirality of amino acids determines their “directional” influence on harmonizing electron spins and the “quantum effectiveness” of electron transport and proton pumping processes. In higher life forms, health and vitality correlates with high metabolic “quantum yields” via the controlled “directional” flow of electrons. In other words, metabolic cycles in living cells of higher life forms act like semiconductor circuits that rely on L-amino acid switches for optimal performance.

In his paper "The Living State and Cancer" [

25] Nobel laureate Albert Szent-Györgyi defined the “living state” as a dynamic (quasi-equilibrium) steady state achieved through the movement of electrons facilitated by the semiconductive role of amino-acids and proteins as the workhorses of life. In this process, proper foldings of chiral proteins, achieved through side chains such as L-Lysine, allow charge transfer reactions and mobility of electrons in the semi-conductive “desaturated” proteins, which build next to them aqueous “charge exclusion” zones with low dielectric constants.

This quantum view of metabolism is compatible with the chiral-specificity of olfactory receptors and the "vibration theory of olfaction,” [

26] which point out to the importance of stereospecificity in both reward- and stress-signaling pathways.

Energy-harvesting organelles (mitochondria and chloroplasts) use biological semiconductors such as Light-harvesting Complex (LHC) proteins, cytochromes, mitochondrial membrane protein complexes and ATP synthase which rely on homochiral aromatic L-amino acid peptides. These stereospecific chiral peptides can function both as energy boosters by polarizing electron spins, or as dissipaters/quenchers (in times of stress) by transducing damaging excess photons or electrons. The L-configuration of amino acids allows proper protein folding and electron delocalization in these proteins. These functions are disrupted by the same stressful xenobiotic stimuli that also upregulate microbial formation of D-amino acids.

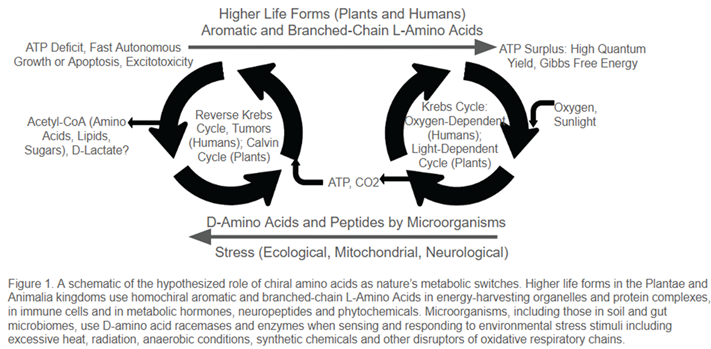

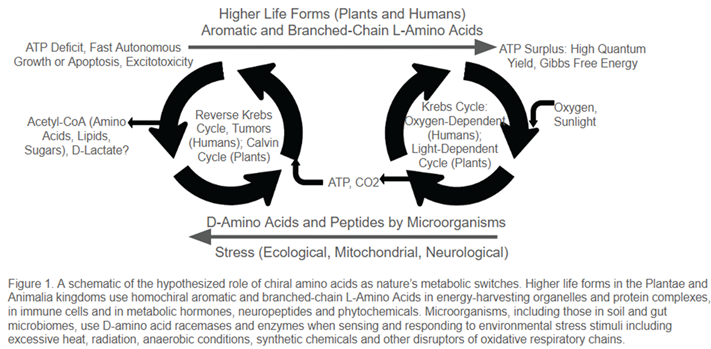

Once in the intercellular space, D-amino acids, as the chiral opposites of L-amino acids, can disrupt their binding affinity and electron transfer efficiency by slowing down or even reversing the protein desaturation process. This effect can act like a semiconductor switch and lead to a transition from a thermodynamically-efficient “living” organized state to what Szent-Györgyi called the disorganized “proliferative alpha state,” a chaotic “cancerous” disruption to cellular homeostasis. In fact, we now know that cancer cells, as well as primitive bacteria and archaea found in deep-sea vents facing extremely harsh hot or alkaline environments can indeed reverse the Krebs cycle to build lipids and other organic compounds for self-sufficient survival and rapid chaotic growth in metabolically hostile ecosystems (Figure 1).

In humans, Szent-Györgyi had identified a D-amino acid (D-lactate) as the end product as well as a marker of the cancerous state that leads to reversal of Krebs cycle and damages to proteins and DNA structures. Recently, serum D-lactate levels have been suggested as a biomarker for diseases related to liver functions or intestinal [

27] integrity.

In plants, abundance of D-amino acids can impair light-dependent photosynthesis, which relies on chiral L-amino acids (for light-harvesting complexes and cytochromes) and functions as the plant’s primary reductive mechanism in restoring the antioxidant pools of NADPH (Reduced Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate) and Glutathione, both essential in prevention of vicious metabolic/oxidative cycles under stress.

Based on these observations and the recently confirmed role of D-amino acids as biochemical modulators in the rhizosphere [

28] and chemotactic stress signals [

29] it is reasonable to hypothesize that D-amino acids from microbes, as sensitive front-line sensors of metabolically hostile ecosystems, play a key role in redox-signaling cascade networks in plants and humans by switching the directionality of electron spin and flow in the Krebs and photosynthetic cycles and ultimately causing a transition from an orderly metabolism in higher life forms to a microbial metabolism with low quantum yield. A recent study confirms [

30] that the appearance of peptides, where L-amino acids are partially replaced by D-analogs, impacts the efficiency of the photoinduced electron transfer and is indeed a primary cause of some diseases. Another recent review [

31] has provided evidence relating D-amino acids to mitochondrial dysfunctions and diabetic kidney disease.

Researchers have also recently demonstrated [

32] that dysfunctions in Citrate Synthase, the first rate-limiting enzyme in the Krebs cycle (also called the Citric Acid Cycle), can switch the cellular metabolic direction from oxidative to reductive (glycolysis or anaerobic) Reverse-Krebs cycle. The enzyme relies on homochiral L-amino acids histidine and aspartate to distinguish pro-chiral carbons in the citrate molecule. Other enzymes in the citric acid cycle also rely on homochiral L-amino acids so one can make a cogent argument that D-amino acids are able to induce enzymatic dysfunctions which are linked to metabolic disruptions, diseases, cell death (apoptosis) and tumors.