1. Introduction

The transformation of long-term care delivery systems has fundamentally altered the provision of healthcare services for older adults. The global implementation of long-term care insurance systems has led to a marked shift toward community-based care models. In South Korea, this transition is evidenced by recent statistics showing that, among 25,494 long-term care institutions, 77.3% are community-based, while only 22.7% are facility-based (Lee and Kim, 2022). This structural transformation has positioned home care workers as crucial providers of direct patient care, while simultaneously introducing complex challenges regarding workforce stability and the quality of care.

A significant disparity exists in employment stability between institutional and home-based care settings. Butler and Kusmaul (2019) reported retention rates of 87.6% in institutional settings compared to 42.2% in home-based care environments. This stark contrast highlights the vulnerable position of home care workers, who often experience heightened job strain and diminished job satisfaction despite their critical role in maintaining community health. The sustainability of community-based care systems fundamentally depends on addressing these workforce challenges through evidence-based interventions that enhance both worker well-being and the quality of care.

Kanter's theory of structural empowerment provides a theoretical framework for understanding and addressing these challenges. According to Laschinger et al. (2001), workplace conditions that provide access to information, support, resources, and opportunities for development create an environment that is conducive to employee empowerment. Their research demonstrated that structural empowerment significantly influences psychological empowerment, which, in turn, affects job strain and work satisfaction. However, the mechanisms through which structural empowerment influences psychological empowerment in home care settings remain unclear.

Recent theoretical developments suggest that several factors may mediate the relationship between structural and psychological empowerment. The concepts of thriving at work and caregiver reciprocity are particularly relevant. Spreitzer et al. (2005) conceptualized thriving at work as a psychological state characterized by vitality and learning, extending beyond job satisfaction to encompass personal growth and development. Complementing this perspective, Christens (2012) emphasized the importance of relational empowerment, highlighting how reciprocal relationships contribute to psychological empowerment through collaborative competence and network mobilization.

The integration of these concepts—structural empowerment, psychological empowerment, thriving at work, and caregiver reciprocity—offers a promising theoretical framework for understanding home care worker outcomes. While previous research has examined these concepts individually, their interrelationships in the context of home care remain unexplored. This gap is particularly significant given the unique challenges faced by home care workers, who often work in isolation and navigate complex interpersonal relationships with clients and healthcare systems.

Therefore, this study aims to examine how structural empowerment influences psychological empowerment through the mediating effects of thriving at work and caregiver reciprocity among home care workers. Specifically, we investigated (1) the direct effect of structural empowerment on psychological empowerment, (2) the mediating role of thriving at work in this relationship, (3) the mediating role of caregiver reciprocity, and (4) the serial mediation effect of both thriving at work and caregiver reciprocity. Understanding these relationships is crucial for developing targeted interventions to enhance worker empowerment and improve the quality of geriatric care in community settings.

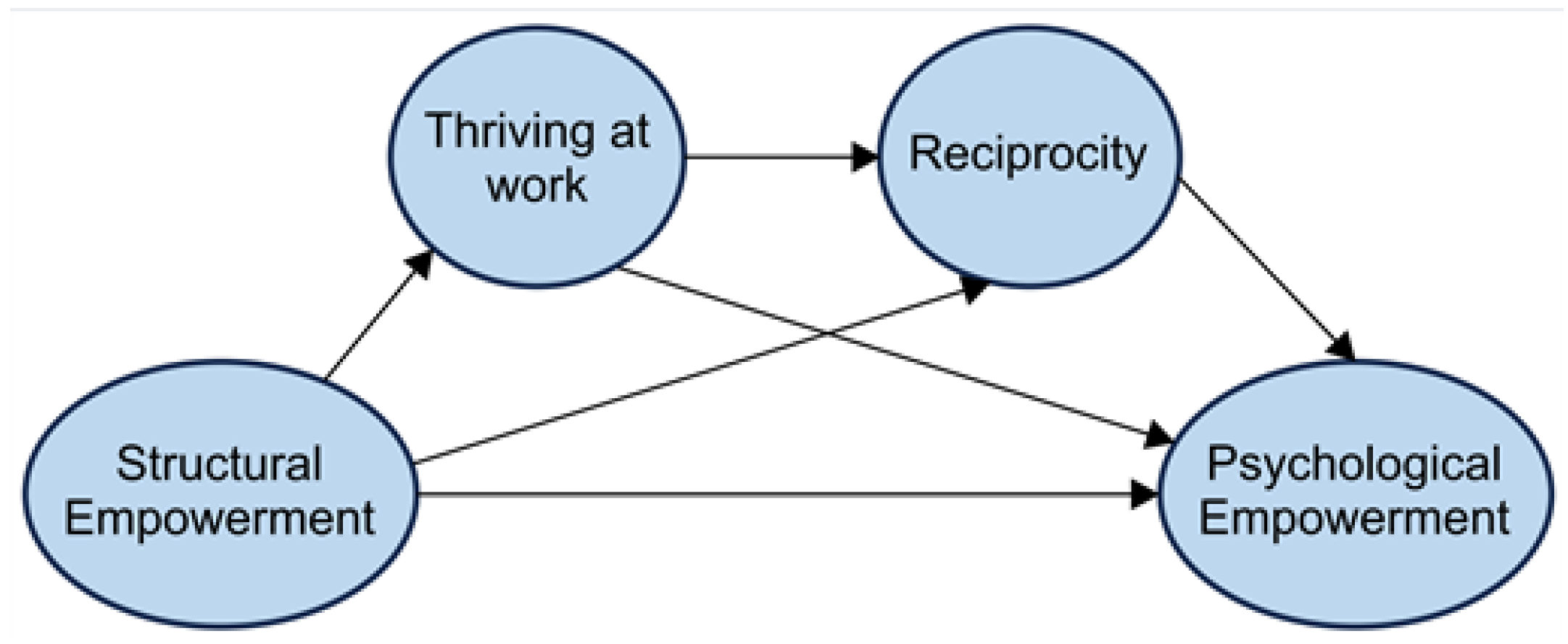

Figure 1.

The hypothetical model of this study.

Figure 1.

The hypothetical model of this study.

This study contributes to the field in several ways. First, it extends Kanter's theory by examining previously unexplored mediating mechanisms in the home care context. Second, it provides empirical evidence regarding the role of relational factors in workers’ empowerment. Finally, it provides practical insights for healthcare administrators and policymakers seeking to enhance home care workforce’s stability and effectiveness.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

A cross-sectional correlational study design was employed to examine the relationships among structural empowerment, thriving at work, caregiver reciprocity, and psychological empowerment in home care workers. This design was selected to test the hypothesized serial multiple mediation model based on Kanter's theoretical framework.

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

The target population comprised home care workers actively providing direct care services to older adults in South Korea. Using convenience sampling, we recruited participants from home care agencies between May 1 and June 1, 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) current employment as a home care worker, (2) with at least six months of work experience, and (3) direct involvement in client care.

A priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 indicated that a minimum sample size of 180 participants was required to detect medium effect sizes (f² = 0.15) with 80% power at α = .05 for multiple regression analyses with four predictors. This analysis assumed a medium effect size based on previous studies that examined similar relationships in healthcare settings.

Of the 220 distributed questionnaires, 200 were returned (response rate = 90.9%). Eight questionnaires were excluded due to missing data (>50% incomplete responses) or uniform response patterns, which were determined through a standard deviation analysis of individual responses. Missing data in the remaining questionnaires (<5% per variable) were handled using multiple imputations. The final analysis included 192 questionnaires.

2.3. Measures

All instruments used in this study have previously demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity in Korean healthcare settings. Permission for use was obtained from the original authors wherever required.

2.3.1. Structural Empowerment

Structural empowerment was measured using the Korean version of Chandler's (1986) Conditions of Work Effectiveness Questionnaire, modified by Yang (1999). This 28-item instrument assesses four dimensions: opportunity (9 items), information (8 items), support (8 items), and resources (3 items). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater perceived empowerment. The instrument demonstrated strong internal consistency in this study (Cronbach's α = .94).

2.3.2. Thriving at Work

The Korean version of the Thriving at Work Scale (Choi & Kim, 2018), adapted from Porath et al.'s (2012) original measure, was used to assess thriving at work. The scale consists of ten items equally distributed across two dimensions: vitality and learning. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater thriving. The internal consistency reliability in the current study was excellent (Cronbach's α = .93).

2.3.3. Caregiver Reciprocity

Reciprocity was assessed using the Korean version of the Nurse and Nursing Assistant Caregiver Reciprocity Scale (Lee & Kim, 2016), originally developed by Yen-Patton (2011). The 16-item instrument measures three domains: balance between collaborators (7 items), affection and goodwill (5 items), and internal rewards (4 items). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating stronger reciprocal relationships. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = .90).

2.3.4. Psychological Empowerment

Psychological empowerment was measured using Park's (2015) Korean adaptation of Spreitzer's (1995) Psychological Empowerment Scale. The 16-item instrument assesses four dimensions: meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact (4 items each). Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater psychological empowerment. The internal consistency reliability was good (Cronbach's α = .82).

2.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 23.0. Preliminary analyses included descriptive statistics, reliability assessments, and examination of the assumptions for parametric testing. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the bivariate relationships among the study variables.

The hypothesized serial multiple mediation model was tested using Hayes' (2015) PROCESS macro (Model 6) with 5,000 bootstrap samples. This approach allows for the simultaneous testing of multiple indirect effects while controlling for covariates. Specific indirect effects were examined using 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the participants and differences in major variables according to these characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The final sample comprised 192 home care workers. The majority were female (n = 184, 95.8%), with a mean age of 55.84 years (SD = 7.55). Most participants were married (n = 163, 84.9%), while some participants were divorced (n = 19, 9.9%) and single (n = 10, 5.2%). Most participants reported having a religious affiliation (n = 146, 76.0%). Educational attainment varied, with 48.4% (n = 93) having college or higher education, 35.4% (n = 68) having high school education, and 16.1% (n = 31) having middle school education or lower. Participants reported substantial work experience, with a mean total experience of 88.19 months (SD = 49.40) and a current workplace tenure of 61.72 months (SD = 47.70).

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

The correlations among the study variables are presented in

Table 2. The analysis revealed significant positive correlations among all key constructs. Psychological empowerment demonstrated significant positive correlations with structural empowerment (r = .337,

p < .001), thriving at work (r = .443,

p < .001), and caregiver reciprocity (r = .416,

p < .001). Structural empowerment showed positive correlations with both thriving at work (r = .445,

p < .001) and caregiver reciprocity (r = .490,

p < .001). Additionally, thriving at work and caregiver reciprocity were positively correlated (r = .618,

p < .001). No significant differences were observed in the main study variables based on the participants' demographic characteristics.

3.3. Serial Multiple Mediation Analysis

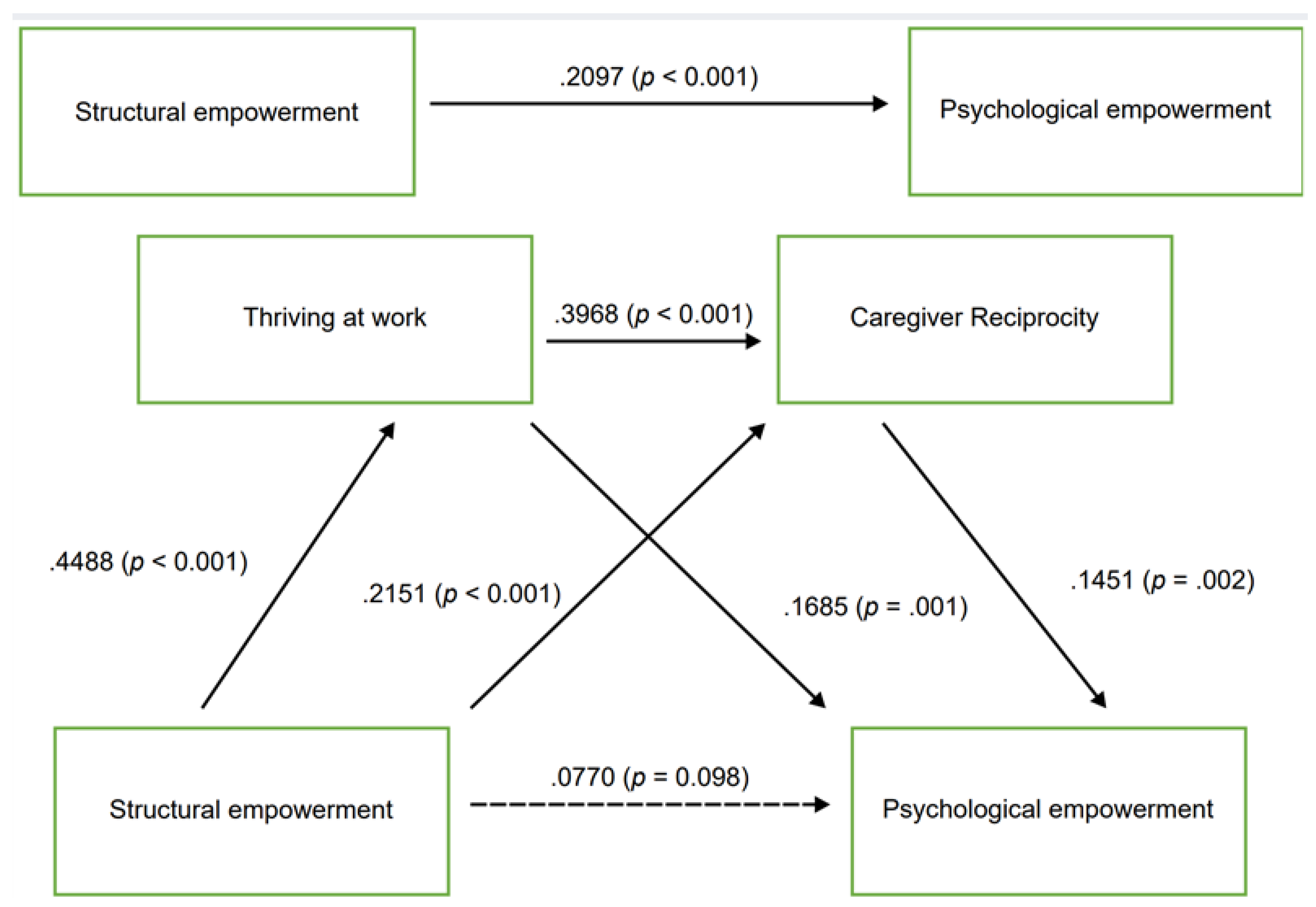

The regression coefficients and model summary information are presented in

Table 3. Structural empowerment demonstrated significant direct effects on thriving at work (β = .4488, SE = .0656,

p < .001), caregiver reciprocity (β = .2151, SE = .0488,

p < .001), and on psychological empowerment (β = .0770, SE = .0464,

p < .001). Thriving at work had significant direct effects on both caregiver reciprocity (β = .3968, SE = .0484,

p < .001) and psychological empowerment (β = .1685, SE = .0510,

p < .001). Caregiver reciprocity significantly influenced psychological empowerment (β = .1451, SE = .0659,

p = .002).

3.4. Mediation Effects

As shown in Table 4, bootstrap analysis with 5,000 resamples revealed significant indirect effects on the dependent variables. The serial mediation path from structural empowerment through thriving at work and caregiver reciprocity to psychological empowerment was significant (β = .1327, 95% CI [0.0713, 0.1929]). Simple mediation analyses showed significant indirect effects for both the structural empowerment → thriving at work → psychological empowerment path (β = .0756, 95% CI [0.0381, 0.1169]) and the structural empowerment → caregiver reciprocity → psychological empowerment path (β = .0312, 95% CI [0.0034, 0.0640]). The total indirect effect was significant (β = .1327, 95% CI [0.0713, 0.1929]), supporting the hypothesized dual-mediation model.

The final model, with standardized path coefficients and corresponding p-values, is illustrated in

Figure 2. The model explained 58% of the variance in psychological empowerment. As shown in

Figure 2, structural empowerment demonstrated both direct effects on psychological empowerment (β = .0770,

p = .098) and indirect effects through thriving at work (β = .4488,

p < .001) and through caregiver reciprocity (β = .2151,

p < .001).

4. Discussion

This study examined the structural relationships among empowerment variables and their mediating mechanisms in home care workers using a serial multiple mediation model based on Kanter's theory. These findings provide empirical support for the complex pathways through which structural empowerment influences psychological empowerment with thriving at work and caregiver reciprocity. Our discussion focuses on three key findings and their implications for nursing practice and future research.

First, our results demonstrate that structural empowerment significantly influences psychological empowerment, both directly and indirectly, extending the findings of Laschinger et al. (2001) to the home care context. The significant direct effect (β = .0770, p < .05) suggests that organizational structures providing access to information, support, resources, and opportunities directly enhance workers' sense of meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact. This finding is particularly relevant for home care settings, where workers often operate in isolation from the organizational structures. The results emphasize the critical importance of establishing robust organizational support systems that maintain connections with geographically dispersed workers.

Second, the serial mediation analysis revealed that thriving at work serves as a crucial intermediary mechanism between structural and psychological empowerment at work. The significant indirect effect of thriving (β = .0756, 95% CI [0.0381, 0.1169]) aligns with Spreitzer et al.'s (2005) conceptualization of thriving as a psychological state characterized by vitality and learning. In the home care context, this finding suggests that empowering organizational structures facilitates workers' experiences of growth and vitality, which in turn enhances their psychological empowerment. This pathway illuminates how organizational investments in worker development and support translate into enhanced psychological capacity.

Third, our findings highlight the vital role of caregiver reciprocity in the empowerment process of caregivers. The significant indirect effect through reciprocity (β = .0312, 95% CI [0.0034, 0.0640]) extends Christens' (2012) work on relational empowerment by demonstrating how reciprocal relationships mediate the impact of organizational structures on psychological empowerment. This finding is particularly salient for home care workers, whose effectiveness depends heavily on their ability to establish and maintain therapeutic relationships with their clients and colleagues.

The dual mediating effect of thriving and reciprocity (β = .1327, 95% CI [0.0713, 0.1929]) reveals the complementary nature of personal growth and relational processes in fostering psychological empowerment at work. This finding suggests that interventions aimed at enhancing home care worker empowerment should simultaneously address both individual development needs and the relational aspects of care work.

4.1. Implications for Geriatric Nursing Practice

Our findings have several important implications for geriatric nursing practice and the quality of care for older adults. First, healthcare organizations should prioritize the development of structural empowerment mechanisms specifically adapted to home care settings. This includes implementing mobile communication systems, creating virtual support networks, and establishing regular in-person gathering opportunities for workers who are isolated. These structural supports directly impact the quality of care provided to older adults by enabling care workers to make informed decisions and respond effectively to clients’ needs.

Second, managers should focus on creating conditions that promote thriving at work through continuous education on geriatric care, skill development opportunities, and fostering meaningful work experiences. Professional development programs should specifically address the complex needs of older adult clients, including dementia care, fall prevention, and end-of-life care. These initiatives should accommodate the unique scheduling challenges faced by home care workers while ensuring high-quality care delivery.

Third, organizations should implement strategies to enhance caregiver reciprocity through mentorship programs, peer support networks, and collaborative problem-solving among care teams. These initiatives should recognize the distinct nature of home care relationships and provide appropriate support structures that ultimately benefit both care workers and their older adult clients. Regular case conferences and care planning meetings can facilitate knowledge sharing and improve care coordination among healthcare professionals.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences regarding the relationships observed. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to examine how these relationships evolve. Second, the use of self-reported measures may have introduced a common method variance. Future studies should incorporate objective measures and multiple data sources to address this limitation. Third, the sample was drawn from a single geographic region, which may limit its generalizability. Replication studies in diverse settings would strengthen the external validity of these results.

Future research should examine how different organizational contexts moderate the relationships observed in this study. Additionally, investigating how empowerment processes influence client outcomes would provide valuable insights into the broader impact of worker empowerment in home care settings.

5. Conclusions

This study provides empirical support for a complex model of empowerment in home care settings, demonstrating how structural empowerment operates through personal growth and relational pathways to enhance psychological empowerment. These findings contribute to our theoretical understanding of empowerment processes and provide practical guidance for enhancing the effectiveness of home care workers. As healthcare systems increasingly rely on home care services, these insights provide valuable guidance for developing and supporting an empowered workforce capable of addressing the complex challenges of community-based care delivery.

References

- Abid, G., Contreras, F., Ahmed, S., & Qazi, T. (2019). Contextual factors and organizational commitment: Examining the mediating role of thriving at work. Sustainability, 11(17), 4686. [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S. L., & Andreetta, M. (2011). The influence of empowering leadership, empowerment, and engagement on affective commitment and turnover intentions in Community Health Service Workers. Leadership in Health Services, 24(3), 228–237. [CrossRef]

- Becker, L. C. (1990). Reciprocity. Univ. of Chicago Pr.

- Butler, S., & Kusmaul, N. (2019). Perceptions of Empowerment Among Home Care Aides. Innovation in Aging, 3, S704-S704. Link.

- Campbell, S. L. (2003). Cultivating empowerment in nursing today for a strong profession in the future Journal of Nursing Education, 42(9), 423-426.

- Casey, M., Saunders, J. A., & O'hara, T. (2010). Impact of critical social empowerment on psychological empowerment and job satisfaction in nursing and midwifery settings. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(1), 24-34. Link.

- Chandler, G. E. (1986). The relationship of nursing work environment to empowerment and powerlessness (Doctoral dissertation, College of Nursing, University of Utah).

- Choi, J., & Kim, M. (2018). Validation of the Korean version of the thriving at work scale. Korean Journal of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 31(3), 715–739. [CrossRef]

- Christens, B. D. (2011). Toward relational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 114–128. [CrossRef]

- Cox, E. O. (2001). Empowerment-oriented practice applied to long-term care. Journal of Social Work in Long-Term Care, 1(2), 27–46. [CrossRef]

- Dahinten, V. S., Lee, S., & MacPhee, M. (2016). Disentangling the relationships between staff nurses' workplace empowerment and job satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(8), 1060-1070. Link.

- Engström, M., Wadensten, B., & Häggström, E. (2010). Caregivers' job satisfaction and empowerment before and after an intervention focused on caregiver empowerment. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(1), 14-23. Link.

- Gill, H., Cassidy, S. A., Cragg, C., Algate, P., Weijs, C. A., & Finegan, J. E. (2019). Beyond reciprocity: The role of empowerment in understanding felt trust. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(6), 845–858. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R. M. (1977). Some effects of proportions on group life: Skewed sex ratios and responses to Token women. American Journal of Sociology, 82(5), 965–990. [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H. S. S., Finegan, J., Shamian, J., & Wilk, P. (2001). Impact of Structural and Psychological Empowerment on Job Strain in Nursing Work Settings: Expanding Kanter’s Model. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 31, 260-272. Link.

- Laschinger, H., Finegan, J., Shamian, J., & Wilk, P. (2004). A longitudinal analysis of the impact of workplace empowerment on work satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 527-545. Link.

- Lautizi, M., Laschinger, H., & Ravazzolo, S. (2009). Workplace empowerment, job satisfaction and job stress among Italian mental health nurses: An exploratory study. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(4), 446-452. Link.

- Lee, D. N. (2019). The effect of job satisfaction on self-leadership of home visiting care-workers in Long Term Care Home Service Center : The verification of mediated effect of empowerment. Korea Academy of Care Management, (33), 5–36. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. S., & Kim, H. Y. (2022). Emotional labor of care worker in long-term care facilities- calling impact on burnout - focusing on Chungcheongnam-do province -. Journal of Community Welfare, 80, 83–107. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. S. (2015). The current state of the working environment for long-term care facility workers and the direction of treatment improvement policies. Proceedings of the Korean Association for Geriatric Welfare Academic Conference, 5(2), 151-160.

- Lee, M. A., & Kim, E. (2016). Influences of hospital nurses’ perceived reciprocity and emotional labor on quality of Nursing Service and intent to leave. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 46(3), 364. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. G. (2015). A study on effect of the psychological empowerment and job satisfaction of caregivers of domiciliary care centers on the quality of Long Term Care Service. Korean Journal of Gerontological Social Welfare, null(70), 9–30. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J., & Lee, Y. (2021). Analysis and prospects for the supply-demand gap of care workers. The Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 21, 12(6), 2255–2268. [CrossRef]

- Ng, H., Boey, K., & To, H. (2022). Structural empowerment among social workers in Hong Kong.

- Park, H. K. (2016). The structural relationship between school vitality level, self-directed learning ability of elementary school teachers, psychological empowerment, and creative job performance. (Doctoral dissertation). Soongsil University.

- Park, S. E., Kim, H. S., & Im, Y. J. (2016). Thriving at Work: Concept, antecedent factors, and effectiveness. Korean Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(2), 155-184.

- Park, S. O., & Park, W. J. (2023). Factors affecting the job embeddedness of nurses in integrated nursing and care service wards: The role of job stress, professional autonomy, and reciprocity. Clinical Nursing Research, 29(1), 1-11.

- Porath, C., Spreitzer, G., Gibson, C., & Garnett, F. G. (2011). Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 250–275. [CrossRef]

- Silén, M., Skytt, B., & Engström, M. (2019). Relationships between structural and psychological empowerment, mediated by person-centred processes and thriving for Nursing Home Staff. Geriatric Nursing, 40(1), 67–71. [CrossRef]

- Siu, H. M., Spence Laschinger, H. K., & Vingilis, E. (2005). The effect of problem-based learning on nursing students’ perceptions of empowerment. Journal of Nursing Education, 44(10), 459–469. [CrossRef]

- Spence Laschinger, H. K., Finegan, J., Shamian, J., & Wilk, P. (2001). Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 260–272. [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological, empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G., Sutcliffe, K., Dutton, J., Sonenshein, S., & Grant, A. M. (2005). A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organization Science, 16(5), 537–549. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. (1999). A study on the relationship between empowerment of nurses, work-related personal characteristics, and job performance. (Doctoral dissertation). Kyung Hee University.

- Yen-Patton, G. P. (2011). Nurse and nursing assistant reciprocal caring in long term care: Outcomes of absenteeism, retention, turnover and Quality Care.

- Yeom, E. Y., & Seo, K. S. (2023). The effect of reciprocity, organization conflict on person-centered care of certified caregivers in long-term care facilities. Journal of the Korean Society for Wellness, 18(1), 67–73. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., Shi, Y., Sun, Z., Xie, F., Wang, J., Zhang, S., Gou, T., Han, X., Sun, T., & Fan, L. (2018). Impact of workplace violence against Nurses’ thriving at work, job satisfaction and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(13–14), 2620–2632. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N., Liu, Y., Zhang, J., Liu, J., Li, J., Wang, S., & Gul, H. (2022). How and why non-balanced reciprocity differently influence employees’ compliance behavior: The mediating role of thriving and the moderating roles of perceived cognitive capabilities of artificial intelligence and conscientiousness. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).