I. Introduction

With the increasing complexity of software systems, code security has become a core issue in modern software development. Traditional code security detection methods mostly rely on static and dynamic analysis tools, however, these methods face the challenges of insufficient accuracy and inefficiency when dealing with complex codes and variable development environments. To cope with this problem, it is particularly important to construct an intelligent method that can deeply understand code semantics and perform efficient detection. Based on this, controlled language design for code security specification detection becomes an important way to improve software security.

II. Existing Methods for Code Security Specification Detection in Software Development

In modern software development, traditional approaches to code security specification detection mostly rely on static and dynamic analysis tools that have limitations in terms of accuracy and level of automation [

1]. Code security specification detection using large-scale language models (LLMs) can identify and predict potential security defects through a deep learning approach. LLMs are able to understand the contextual semantics of the code, improve the accuracy of defect detection, and automatically correct code that does not comply with security specifications. This approach demonstrates significant advantages in improving software security and development efficiency, especially when dealing with dynamically changing code in large-scale projects, and effectively reduces the burden and error rate of manual review.

III. LLM-Based Controlled Language Design for Code Security Specification

A. Architecture of LLM language model for code security application

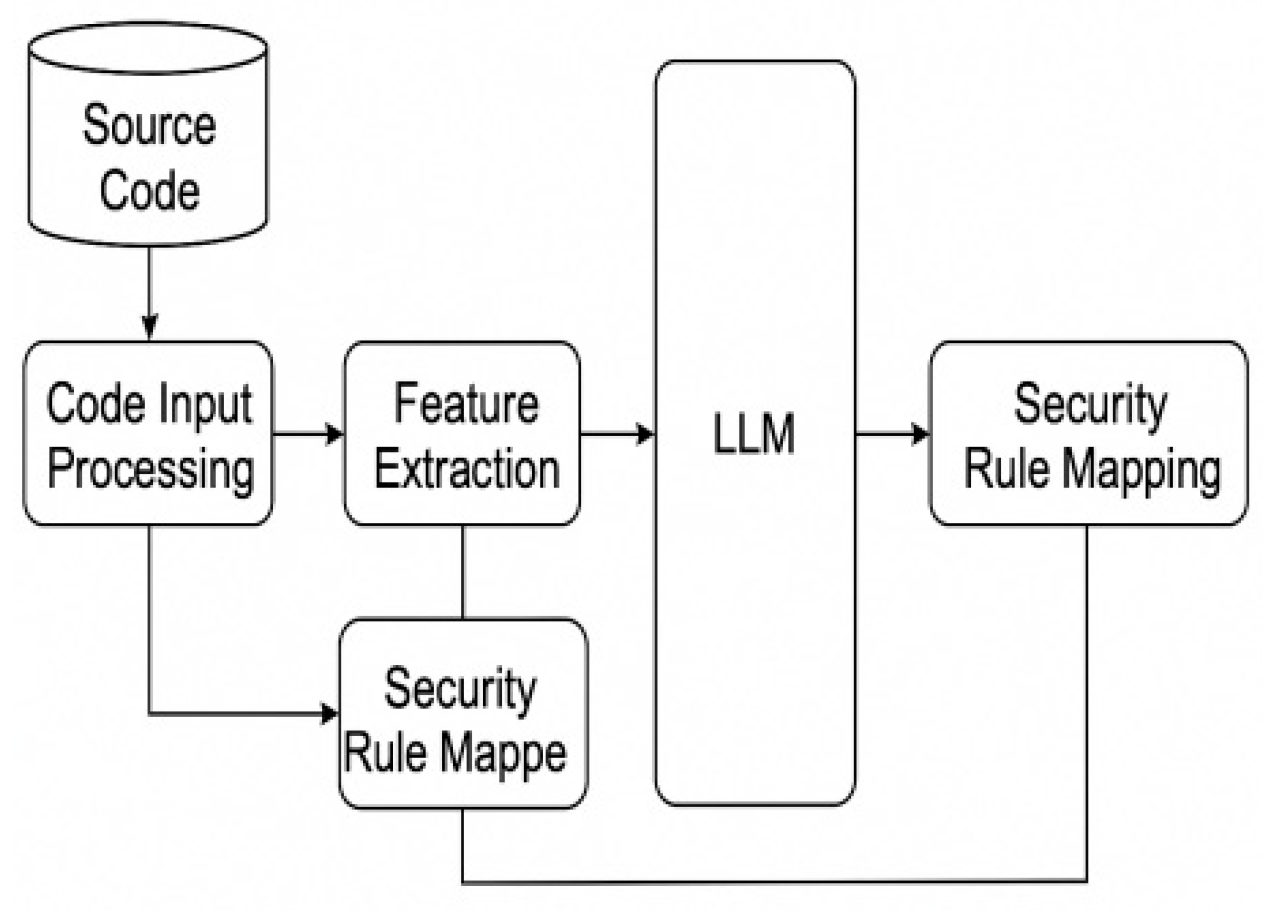

The application architecture of the LLM language model is key in building a controlled language design for code security specification based on the Large Language Model (LLM) [

2] . The architecture leverages the advanced natural language processing capabilities of LLM for deep semantic analysis and pattern recognition of source code to identify potential security vulnerabilities. The architecture consists of four main components: code input processing, feature extraction, security rule mapping and correction suggestions. The code input processing module is responsible for parsing the source code and transforming it into a model-understandable format; the feature extraction module utilizes LLM to extract the structural and semantic features of the code; the security rule mapping module matches the extracted features with predefined security specifications; and, finally, the correction recommendation module generates specific recommendations for security improvements (see

Figure 1 for details.).

C. Language constraints and rules construction based on language modeling

The construction of language constraints and rules based on language models relies on the structured extraction and symbolic logic derivation of a large number of security semantic features [

5] . In the construction process, a deep language embedding vector space is used to encode vectors for 2700 types of function call patterns, 19000 variable action chains, and 8400 control flow paths, and semantic constraint induction is realized through self-supervised learning. Regularized constraint functions are introduced in the model training phase:

where

is the output of the LLM representation of the sample code fragment,

is the corresponding security specification target vector, and

is the constraint strength parameter set in the interval [0.1, 5.0]. The loss function constrains the model output to converge to the legitimate semantic space, ensuring that the code generation and refactoring process conforms to the pre-defined set of rules [

6] . The language rule construction covers five categories of key constraint domains, specifically including variable name specification, function authority boundaries, loop nesting hierarchy, input validation paths, and memory access sections, with no less than 45 sub-rules refined within each category of constraints. The parameter mapping is shown in

Table 1:

D. Syntactic and Semantic Modeling of Security Specification Languages

The syntactic and semantic modeling design of the security specification language is based on a multi-layer abstract representation and symbolic semantic fusion mechanism, which fuses a formal language G = (N, Σ, P, S) and a family of symbolic semantic mapping functions F, to achieve multi-dimensional modeling of code structure, constraint relations and contextual semantics [

7] . The grammar rule set includes 128 sets of generative formulas, terminator Σ contains 245 items, and non-terminator N covers 162 classes of code structure units. Semantic modeling uses graph neural network as the core structure to construct the edge-weighted graph G(V, E) where node V denotes the AST grammar node (total number of nodes ≥ 3200), and the set of edges E corresponds to the relationships of variable dependency, control flow, and data flow, which generates a total of about 2.1 × 10⁶ edges. The core semantic function is:

where

is the embedding vector of any two AST nodes,

, the bias term

, and the activation function adopts GELU. This function constructs the learnable semantic relationship weights between nodes and enhances the deep dependency propagation through the residual mechanism. In order to further clarify the functional boundaries and parameter configurations of each constituent module in the process of syntactic and semantic fusion, the core building blocks are structured and quantified and organized [

8] . By systematically sorting out the parameter dimensions, activation functions, number of mapping rules and other dimensions of the modules of syntactic parsing, AST embedding, graph neural propagation, and semantic matching, it can provide a clear technical reference support for subsequent model training, optimization and actual deployment. The specific parameter composition is detailed in

Table 2.

IV. LLM-Assisted Code Security Specification Detection Methods

A. Technical process of natural language to controlled language conversion

In the technical process of natural language to controlled language conversion, the key lies in the construction of the whole process of semantic parsing, command intent recognition and structure mapping using large-scale pre-trained language model (LLM) [

9] . The process contains five core phases: semantic annotation, intent recognition, syntax tree generation, structure mapping and controlled language synthesis, covering a total of about 470 million parameters, a processing vector dimension of 1024, more than 18,500 classes of transformed semantic templates, and supported language models covering 45 kinds of security constraint structures and 21 kinds of contextual dependencies. The core conversion functions are defined as follows:

where

is the semantic template of the first

class,

is the contextual embedding of the natural language input,

denotes the weight coefficients, and the

function constructs the template mapping relationship using weighted cosine similarity, with k taking the value range of [1, 450]. The model adopts residual attention structure to improve the stability of multi-layer mapping, and finally outputs the controlled language sequence, whose length distribution has a mean value of 29.4, a maximum value of 87, and covers 750 rule nodes. In order to facilitate the understanding of the function and parameter characteristics of each stage of the conversion process, the process modules are structured. Meanwhile, in order to clarify the parameter configuration and computational characteristics of each stage,

Table 3 details the main module parameters of the natural language conversion process.

B. Semantic Mapping and Similarity Calculation Methods

In LLM-assisted code security specification detection, the semantic mapping and similarity computation method constructs a high-dimensional semantic space based on multi-dimensional embedding vectors, and realizes the accurate mapping between natural language and controlled language through semantic tensor alignment [

10] . The semantic vector dimension is set to 1024, the number of mapping templates is set to 6800 groups, and each group of templates contains an average of 62.4 key semantic slots, and the total mapping relation matrix size reaches 6.1×10⁶. The core computation method uses weighted cosine similarity, defined as follows:

where

is the semantic vector representation of natural language and controlled language respectively, and the dimension

is the weight parameter of the third dimension, which is dynamically adjusted according to the importance of semantic slots. The method combines the positional attention mechanism and contextual convolutional features to enhance the expressive ability of low-frequency semantic components, supports cross-modal matching and constrained semantic extraction under multi-language and complex namespaces, and supports the maximum number of parallel comparison pairs of up to 5.3×10⁷ pairs, which is highly robust and generalizable in the exact matching scenarios of security rules.

C. Code Security Specification Detection Algorithm Design

The code security specification detection algorithm design adopts a fusion of deep representation structure and controlled language rule matching mechanism, and realizes the unified modeling of semantic abstraction, syntactic constraint parsing and specification violation detection through multi-layer neural network. The model structure contains embedding layer, encoding layer, rule matching layer and anomaly localization layer, with 690 million total references, 1024 embedding dimensions, 9200 rule templates, and a constraint rule vector matrix size of more than 7.2×10⁶. The core of the algorithm consists of three sub-modules, and its loss function is designed as follows:

where,

, is the rule matching loss with the number of matching pairs N=185000;

, is used to keep the output consistent with the controlled language specification with the constraint dimension M=768;

is the classification loss of the detection module, the total number of anomaly candidate locations T=42000; weight coefficients λ1=0.8, λ2=1.2. the model adopts a three-layer Transformer structure, each layer contains 8-head attention mechanism, the feed-forward network has a width of 2048, the activation function is GELU, and the upper limit of the length of the location coding is 512. the detection phase scans the AST through a sliding window mechanism path sequence with a window size of 15, a step size of 3, and a batch size of 256.Candidate detection points are clustered and divided in a 128-dimensional high-dimensional space, utilizing a threshold decision function:

where

is the center vector of target rules, the threshold

is dynamically adjusted to fit different language contexts. The whole inspection process supports parallel analysis of abstract syntax patterns in more than 40 different language structures, with an annual processing capacity of more than 12 million lines of code, which is suitable for high-intensity code review scenarios in complex business systems, industrial software, and security-sensitive fields.

V. Experimental Results and Analysis

A. Experimental design

The experimental design focuses on evaluating the effectiveness and stability of LLM-driven code security specification detection system in multi-language and multi-project environments. The experimental dataset covers three mainstream languages, C/C++, Java and Python, and contains a total of 1.38 million function-level code snippets, involving 426,000 static defect samples, 193,000 dynamic vulnerability snippets, and no less than 6,800 rule types. In the training phase, 80% of the data is selected for supervised learning, and the remaining 20% is used for testing and validation, using a batch size of 128, a learning rate of 3e-5, and the number of iterations set to 20 rounds. The experiments are deployed in a 4-block NVIDIA A100 (40GB) GPU environment, with a maximum graphics memory occupation of 36.4GB, an average training duration of about 2.7 hours per round, a total model parameter size of 690 million, a model output dimension of 1024, and a dynamic window scanning mechanism for the detection process, with the window length set to 15 and the step size to 5, to ensure that the coverage of the complex control flow and the call chain The depth reaches more than 98%. The whole experimental process is centered on high-density defect injection, multi-type rule verification and cross-language generalization performance, which provides systematic technical support for evaluating the practical value of the model in industrial-grade security review tasks.

B. Experimental results

The designed LLM-based security specification detection system shows good accuracy and stability in cross-language and multi-rule environments. In the code function-level detection task, the combined accuracy rate for all three types of languages, C/C++, Java, and Python, exceeds 93%, and the false alarm rate is controlled within 4.2%, and the performance is especially stable in the function privilege leakage and memory access out-of-bounds type of rules. In order to further analyze the performance difference of the model in different defect types and language scenarios, quantitative comparative analysis is carried out from two perspectives of defect dimension and language dimension, and the experimental data are shown in

Table 4.

As seen in

Table 4, the detection accuracy of the model in the "memory access overrun" category reaches 95.6%, which is the highest among all types, and the false alarm rate is only 3.2%, which indicates that the LLM has higher pattern recognition ability when dealing with structured boundary access scenarios; the detection accuracy of the "incomplete exception processing" category is 91.4%, which is lower than the other defect types, and the omission rate reaches 3.9%, reflecting that the model has a certain complexity bottleneck when dealing with abnormal logic branches. The detection accuracy of the "Incomplete Exception Processing" category is 91.4%, lower than other defect types, with a miss-reporting rate of 3.9%, reflecting that there is a certain complexity bottleneck in the model's processing of exception logic branches. In addition, the defect detection delay of "function privilege leakage" is 11.4ms, which is lower than that of "incomplete abnormality processing" (13.0ms), indicating that the defects with stable control structure are more efficiently processed.

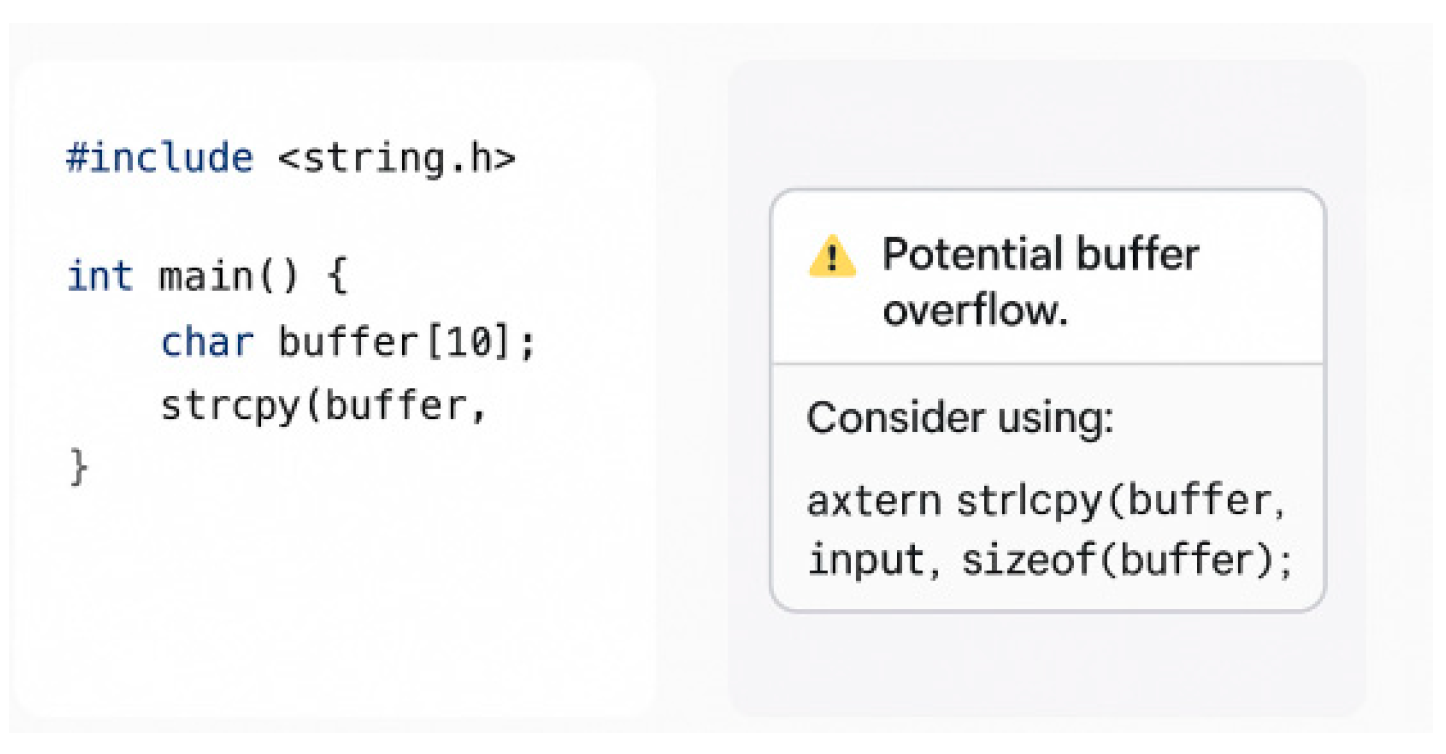

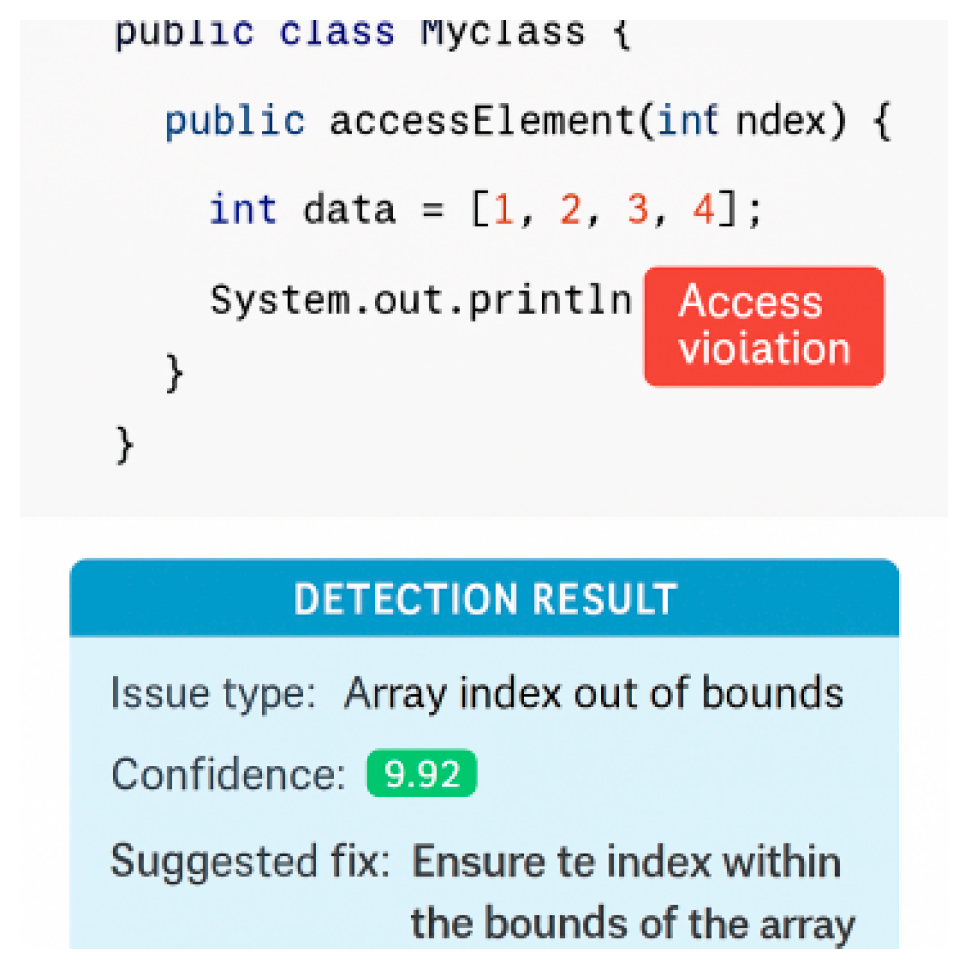

In order to show more intuitively the actual detection capability of the model in different language environments,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 demonstrate the comprehensive performance of LLM in identifying hazardous codes, locating defective locations, and generating repair suggestions:

Figure 2 shows a typical code snippet of a memory leak triggered by an uninitialized pointer in C/C++, where the system identifies the risky location and generates a structured repair recommendation based on the context.

Figure 3 depicts a code scenario for accessing protected member variables in Java, with specific line numbers labeled for improper access rights, and a confidence score with a description of the correction method.

Figure 4 presents a function body with missing input validation in a Python script, where the system identifies a potential SQL injection risk and suggests a patch fix using parameterized queries.

VI. Conclusions

The code security specification detection method based on large-scale language modeling significantly improves the detection accuracy and efficiency of code security in software development. The method provides accurate identification and repair solutions for potential vulnerabilities in complex code environments through deep semantic understanding and rule mapping. Future research will focus on optimizing the cross-language adaptability of the model and further improving the real-time detection capability in dynamic environments. Meanwhile, considering the diversity of code security requirements, customized optimization for different programming languages and development frameworks will be a key direction to improve the comprehensiveness and applicability of detection.

References

- Zhu, Y.Q.; Cai, Y.M.; Zhang, F. Motion capture data denoising based on LSTNet autoencoder. Journal of Internet Technology, 2022, 23, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Murphy, J.; Rahman, A. Come for syntax, stay for speed, write secure code: an empirical study of security weaknesses in Julia programs. Empirical Software Engineering, 2025, 30, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidin, S.S.; Yahya, N.; bin Fauri Fauzi, M.A.; et al. Current and Future Trends for Sustainable Software Development: Software Security in Agile and Hybrid Agile through Bibliometric Analysis. Journal of Applied Data Sciences, 2025, 6, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M.; Akour, M. AI-Driven Innovations in Software Engineering: a Review of Current Practices and Future Directions. Applied Sciences, 2025, 15, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raitsis, T.; Elgazari, Y.; Toibin, G.E.; et al. Code Obfuscation: a Comprehensive Approach to Detection, Classification, and Ethical Challenges. Algorithms, 2025, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Li, S.; Bo, T.; et al. Image retrieve for dolphins and whales based on EfficientNet network[C]//Sixth International Conference on Computer Information Science and Application Technology (CISAT 2023). SPIE, 2023, 12800, 1239-1244.

- Martinović, B.; Rozić, R. Perceived Impact of AI-Based Tooling on Software Development Code Quality. SN Computer Science, 2025, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingras, S.; Basu, A. Modernizing the ASPICE Software Engineering Base Practices Framework: Integrating Alternative Technologies for Agile Automotive Software Development. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM), 2025, 13, 1880–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Huang, S.; Li, Y.; et al. BadCodePrompt: backdoor attacks against prompt engineering of large language models for code generation. Automated Software Engineering, 2025, 32, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandotiya, S. Generative AI for software testing: Harnessing large language models for automated and intelligent quality assurance. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 2025, 14, 1931–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).