Introduction

Nephroblastoma, commonly known as Wilms Tumor (WT), is the most common pediatric kidney cancer, most typically affecting children between the age of 3 to 5 [

1]. Although there are excellent survival rates for WT, around 15 percent of patients will not respond to treatment; this percentage increases as the diagnosis of WT becomes more aggressive [

1]. Current therapies, like chemotherapy, can leave long-term side effects on patients, hence why it is critical to continue studying WT and develop novel therapies that will maintain high survival rates while decreasing the burden of current treatment. Alternative therapeutic approaches, such as surgery and radiation, have been employed for WT [

2], particularly in cases of diffuse anaplasia; which is associated with a more severe prognosis and greater resistance to treatments [

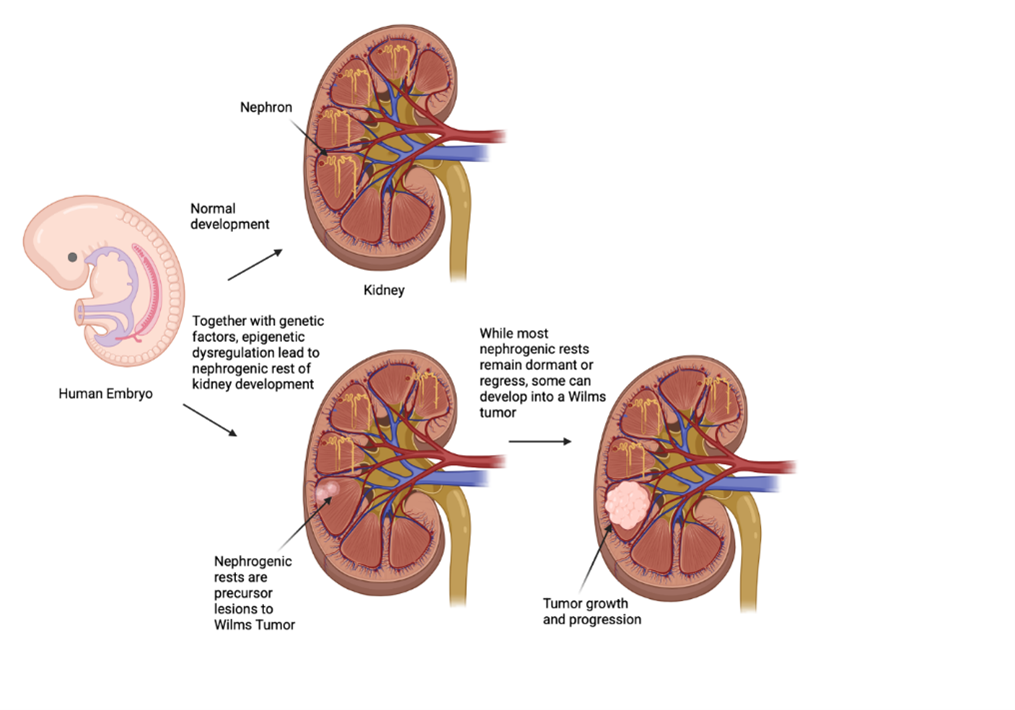

3]. Increasing evidence suggests that WT development is linked to aberrant nephrogenesis, which arises when embryonic kidney cells fail to properly mature into nephron progenitor cells around the ureteric bud. The aberrant proliferation of these undifferentiated cells leads to tumor formation in the kidney cortex [

4]. There have been substantial advances in the understanding of WT pathogenesis over recent decades; however, the mechanisms that disrupt differentiation and lead to tumor growth remain unclear. Although WT is associated with certain birth defects and gene mutations, there is no evidence supporting the direct inheritance of the cancer from the parents.

While there were germline mutations contributing to familial WT on gene locus 11p15, there are also epigenetic mutations on this locus that more relevantly contribute to Wilms tumorigenesis. There were several somatic mutations at 11p15 that were discovered in 69% of tumors [

5]

. According to a paper by Elise M. Fiala, MS, et al, when patients are predisposed to Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome (BWS) on locus 11p15.5, they are more at risk for WT; there is a gain-of-function methylation at imprinting control 1 (IC1) and has a high-risk factor for those with BWS (28%) to develop WT. Moreover, out of an experimental sample of 21 WT patients, 33% were shown to have an epigenetic abnormality on locus 11p15.5 that could be detected in their blood [

6]

. This discovery indicates that epigenetic changes that lead to WT may not only be found in the tumor itself but also have indicators within the patients’ blood. Epigenetics alternations are central to oncogenesis in many pediatric cancers due to their low mutational burden. It is now appreciated that WT is a generally non-familial disease, and epigenetic abnormalities significantly contributed to tumorigenesis. The development of the pediatric kidney closely resembles that of WT development, as the tumors are most commonly discovered in nephrogenic rests, which are consistently located around the renal medulla and periphery of the kidney, both of which arise during early renal development up until the gestational period [

7]. Furthermore, WT shares many features with the embryonic kidney, which suggests a close link between normal kidney development and the genesis of WT. The structure of the developing kidney is often maintained in WT, making it easier to study how WT interacts with normal kidney development and progression of the disease [

7]. This review will summarize the significant contribution of epigenetic mechanisms to Wilms tumorigenesis, in comparison to kidney development, with the ultimate development of highly novel and impactful therapies that alleviate adverse outcomes for the affected children.

Epigenetic Alterations in Wilms Tumor

Epigenetics refers to changes in organisms driven by external factors—such as environmental influences and chemical exposures—without altering the organism's DNA sequence. Epigenetics plays a crucial role in cancer development and progression, alongside genetic alterations. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA, can alter gene expression and contribute to uncontrolled cell proliferation, as well as other common characteristics of cancer, such as suppressed differentiation gene expression and immune evasion. These changes can be reversed, making epigenetics a promising avenue for cancer treatment. They are particularly relevant in childhood cancers due to their low rate of genetic mutations. WT is increasingly considered as a disease driven by epigenetic dysfunction. Understanding the epigenetic basis of WT is critical for uncovering the molecular mechanisms underlying pediatric kidney cancer and abnormal renal development. Unlike many adult cancers driven primarily by genetic mutations, WT often involves disruptions in developmental gene regulation through epigenetic alterations—such as loss of imprinting at 11p15 (IGF2/H19), DNA methylation changes, and mutations in chromatin remodeling genes (e.g., WT1, ARID1A, BCOR). These changes can lead to the persistence of undifferentiated nephron progenitor cells and mis-regulated growth signals, contributing to tumorigenesis. By elucidating these epigenetic mechanisms, we can not only improve risk stratification and identify biomarkers for early detection, but also develop novel, targeted therapies that reverse epigenetic dysregulation—potentially reducing toxicity and improving outcomes for children with WT.

DNA Methylation in Wilms Tumor

DNA methylation, where methyl groups are added to

the fifth carbon of a cytosine base within a CpG dinucleotide—a pair of cytosine and guanine nucleotides connected by a phosphodiester bond, is a major mechanism of

epigenetic gene silencing.

Methylation is carried out by enzymes called DNA methyltransferases, which transfer a methyl group onto cytosine bases. This modification reduces gene expression in the affected DNA strands, effectively silencing specific genes and regulating cellular function [

8]. DNA methylation significantly contributes to cancer development and progression. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns, including both global hypomethylation and site-specific hypermethylation, are hallmarks of many tumors. These changes can lead to silencing of tumor suppressor genes or activation of oncogenes, contributing to uncontrolled cell growth and tumor formation [

9]. DNA methylation plays a significant role in WT development and progression. In WT, altered methylation patterns can affect genes involved in tumor growth, development, and overall tumor behavior [

10].

According to a study by Elise Fiala, an increase in DNA methylation has been shown to increase the risk of Wilms tumorigenesis through the 11p15.5 and 11p13 regions of the chromosome [

11]

. 11p15.5 is known to harbor the WT2 locus, which includes imprinted genes like Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF2) and H19 (a long non-coding RNA). Imprinting refers to the phenomenon where the expression of certain genes is determined by the parent (mother or father) the gene is inherited from. In WT, alterations in the imprinted genes at 11p15, like H19 and IGF2, can disrupt this normal imprinting pattern and lead to increased expression of IGF2, which can contribute to tumor growth [

12].

H19 and IGF2 are transcriptionally active from the maternal and paternal chromosomes respectively. A base level of methylation of imprinting center 1, more specifically the H19/IGF2: IG-DMR (herein) genomic region, allows H19 to solely be produced by the maternal allele and IGF2 by the paternal allele, indicating an increased understanding of the epigenetic mechanisms surrounding methylation. When this region is hypermethylated along the maternal chromosome, IGF2 will become transcriptionally active on the maternal allele and induce inactivation of H19, which has been demonstrated as a defect along the nephrogenic rests, also contributing to Wilms tumorigenesis [

12]. The 11p13 region harbors the WT 1 (WT1) locus, and mutations in the WT1 gene are frequently observed in WT. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in this region can also disrupt WT1 function, contributing to Wilms tumorigenesis. In addition, WT can be classified into different subtypes based on their DNA methylation patterns, which correlate with clinical outcomes. For example, one study identified four prognostic subtypes of WTs, with differences in prognosis, age, sex, histological type, and tumor stage [

13].

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), by inhibiting expression of certain genes, may drive unregulated cell proliferation in WT. By understanding the mechanisms behind methylation and its role in tumorigenesis, researchers can develop targeted approaches for potential therapies, focusing on reversing or modifying these epigenetic changes. In a publication by Sarah Albasha, et al.

, hypermethylation among certain genes such as CCL2, CCL5, and CD4, can be correlated to carcinogenesis, with a potential clinical approach of DNA methyltransferase inhibitors being discovered [

14]

. These insights are crucial for understanding the specific role of methylation and identifying the exact DNA modifications, enabling researchers to target genes and chromosomal regions of interest. By pinpointing these genetic loci, scientists can explore key developmental pathways within the central dogma, aiming to develop drugs that can demethylate hypermethylated regions. This approach may reduce unregulated cell proliferation, offering a promising therapeutic strategy for conditions like WT. In the context of WT, DNMT inhibitors are being researched as potential therapeutic targets [

15]. Specifically, DNMT inhibition may lead to the expression of genes involved in tumor development, potentially helping to control tumor growth and reduce the inflammatory microenvironment in WT [

15].

In summary, understanding the role of DNA methylation in WT development and progression is crucial for developing new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

RNA Methylation in Wilms Tumor

RNA methylation is a post-transcriptional modification where methyl groups are added to RNA nucleotides, primarily at the N6 position of adenosine (m6A). Like DNA methylation, m6A is reversible and regulated by specific enzymes: writers (methyltransferases, such as METTL3, METTL14), erasers (demethylases, such as FTO, ALKBH5), and readers (bind to m6A-modified RNA and affect its fate, such as YTHDFs, IGF2BPs (bind to m6A-modified RNA). This modification impacts various aspects of RNA function, including splicing, translation, stability, and localization. Different types of RNA methylation exist, with m6A being the most prevalent and well-studied. m6A plays a multifaceted role in cancer, influencing processes like cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. M6A impacts both coding and non-coding RNAs, potentially promoting or suppressing tumor growth depending on the context. Furthermore, m6A methylation can affect the tumor microenvironment and even influence cancer treatment resistance. Abnormal m6A modifications in cancer can lead to changes in gene expression, protein translation, and RNA stability, ultimately contributing to cancer cell behavior.

Genetic variations in m6A modification genes, like ALKBH5, have been investigated for their potential contribution to WT risk [

16]. WT 1-associated protein (WTAP) is a component of the m6A writer complex, which is responsible for depositing m6A modifications on mRNA. WTAP specifically helps to recruit the m6A methyltransferase complex (METTL3 and METTL14) to target mRNAs [

17]. WTAP's involvement in the m6A writer complex potentially plays a role in regulating RNA metabolism and potentially contribute to the development or progression of WTs. Research is ongoing to further understand the specific mechanisms by which m6A modification, including that mediated by WTAP, contributes to WT development and to explore potential therapeutic targets based on m6A modification. m6A may disrupt the finely tuned expression of genes critical for

kidney development, contributing to the

developmental arrest seen in WT. For example,

m6A-modified transcripts involved in nephron progenitor maintenance (like SIX2-related pathways) may be improperly degraded or overexpressed. IGF2, already central in WT via loss of imprinting at 11p15, is also regulated post-transcriptionally by m6A readers (

IGF2BPs), suggesting a

convergence of epigenetic and post-transcriptional control. Studies have revealed the potential prognostic value of m6A-related genes and their relationship to the immune microenvironment in WT [

16]. Four m6A-related genes were successfully screened, including ADGRG2, CPD, CTHRC1, and LRTM2 [

16].Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that the four genes were closely related to the prognosis of WT, which was also confirmed by receiver operator characteristic curves [

16]. m6A machinery components are druggable, and inhibitors targeting METTL3 or IGF2BP proteins are under investigation in other cancers [

18]. Targeting m6A dysregulation could offer a novel strategy for therapy-resistant or relapsed WTs.

Understanding the role of m6A RNA methylation in WT offers a novel perspective on post-transcriptional regulation in pediatric kidney cancer and may uncover new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for improved clinical outcomes. As our knowledge deepens, m6A-related pathways hold promise not only as biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis but also as potential therapeutic targets in the pursuit of precision medicine for WT.

Histone Modifications in Wilms Tumor

Histone modifications are fundamental epigenetic mechanisms that alter chromatin structure and regulate gene expression. Histones are the main proteins around which DNA is wrapped in the nucleus, forming nucleosomes. Histone modifications involve covalent alterations to histone proteins, primarily acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, all of which can regulate transcription by altering chromatin structure, directly affecting how tightly DNA is packed, and by recruiting other proteins that influence gene expression. Specific enzymes, like histone acetyltransferases (HATs), histone deacetylases (HDACs), histone methyltransferases, and histone phosphatases, are responsible for adding or removing these modifications. Histone modifications play a significant role in cancer development and progression [

19]. Dysregulation of these modifications can lead to aberrant gene expression, disrupting cell processes and contributing to tumor formation, invasion, and metastasis.

Histone acetylation and deacetylation, the key epigenetic processes, play a crucial role in regulating gene expression and are implicated in various diseases, including cancer. HATs add acetyl groups to histones, leading to increased gene expression, while histone HDACs remove acetyl groups, resulting in gene silencing. In WT, imbalance in histone acetylation and deacetylation can lead to the aberrant expression of genes involved in tumor growth and progression. For example, the downregulation of tumor suppressor genes due to increased deacetylation can contribute to tumor development. MYCN, a key oncogene, is linked to histone acetylation, a process where acetyl groups are added to histone tails, which alters chromatin structure and affects gene expression [

20]. MYCN's ability to induce tumorigenesis involves altering histone acetylation patterns, influencing gene expression and ultimately promoting tumor development. MYCN interacts with

HATs/HDACs to modulate oncogenic gene expression. MYCN amplification is a key characteristic of aggressive WT, particularly anaplastic subtype [

21].

MYCN-amplification dysregulates the cell cycle progression leading to relapse, poor survival, and treatment resistance [

22]. Anaplasia in WT is defined as a three-fold nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia and abnormal mitotic figures. HDACs can also deacetylate non-histone proteins, influencing cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation. Studies have revealed the critical role of HDACs, especially HDAC1 and HDAC2, in kidney development [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Some studies suggest that HDACs (particularly

HDAC1-2, HDAC4-5) are overexpressed in WT, contributing to tumorigenesis by silencing tumor suppressor genes [

27,

28,

29]. HDAC inhibitors have shown promise in treating WT, especially in high-risk cases like those involving blastemal-predominant WT [

29]

. These inhibitors, like panobinostat and romidepsin, have been found to be effective against a variety of WT, even more potent than doxorubicin in some cases. Research has shown that HDAC inhibitors can target specific oncogenic pathways in WT, potentially enhancing treatment outcomes [

29,

30]. Wilms tumor 1(WT1) is a gene that encodes a protein involved in regulating cell growth and differentiation. WT1 interacts with

HATs (e.g. p300/CBP) and HDACs to regulate gene expression [

31,

32,

33]. Mutations or loss of WT1 were found to disrupt the acetylation balance, leading to aberrant proliferation [

34]. Loss of imprinting (LOI) of

IGF2 is common in WT. A study also showed that HDAC inhibition can restore normal imprinting, suggesting a role for acetylation in IGF2 regulation [

35]. In short, histone acetylation/deacetylation imbalances contribute to WT pathogenesis, particularly through

WT1 dysfunction, IGF2 dysregulation, and HDAC overexpression. Targeting these epigenetic mechanisms could offer new treatment strategies.

Histone methylation refers to the addition of methyl groups (–CH₃) to specific amino acids on histone proteins (like lysine or arginine residues on histones H3 and H4). These modifications alter chromatin structure and regulate gene expression — either activating or repressing transcription depending on the site and degree of methylation. Histone methylation is catalyzed by histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and removed by histone demethylases (KDMs). In cancer, histone methylation often gets dysregulated, leading to abnormal expression of oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes. Histone methylation plays a crucial role in WT development and progression, influencing gene expression and potentially contributing to tumor growth and metastasis. In WT, dysregulation of HMTs and KDMs contributes to altered gene expression and tumor development. Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2) is the

catalytic subunit of the

Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), which

tri-methylates H3K27 (H3K27me3) to

repress gene transcription. EZH2 plays a crucial role in kidney development and disease [

36]. EZH2 is often overexpressed in WT, this increased EZH2 activity leads to excessive H3K27me3 at key differentiation gene promoters, suppression of genes critical for kidney cell differentiation, and maintenance of progenitor-like, undifferentiated states in nephron progenitor cells (especially Six2+ cells) [

36]. As a result, kidney development is blocked at an immature stage, and proliferation continues, promoting tumor formation. Studies show that high EZH2 expression correlates with poor differentiation in WT and some aggressive subtypes of WT (e.g., anaplastic WT) show especially high EZH2 activity.

EZH2 is increasingly being studied as a

biomarker (

Table 1). Drugs targeting histone methylation (like

EZH2 inhibitors, e.g., tazemetostat) are now being developed and approved for certain cancers (e.g., epithelioid sarcoma, follicular lymphoma) [

37].

H3K4me3 is a histone modification where lysine 4 on histone H3 is methylated three times. It's generally considered a marker of active chromatin and often found at the promoter regions and transcription start sites. In the context of WT, the regulation of H3K4me3, particularly by enzymes like MLL (also known as KMT2A), plays a role in tumor development. Studies have shown increased levels of H3K4me3 in WT [

7,

39]. The elevated H3K4me3 in WT may contribute to the upregulation of genes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, and growth. This increased expression could potentially contribute to tumor growth and progression. H3K4me3 marks are enriched at promoters of genes involved in

cell proliferation, stemness, and developmental pathways (e.g.,

MYCN, LIN28B) [

40]. Overexpression of these genes due to aberrant H3K4me3 can drive WT growth [

7,

41]. Loss of H3K4me3 at

tumor suppressor genes (e.g.,

TP53) may contribute to their silencing [

42]. Similarly,

WT1, frequently mutated in WT, interacts with histone methylation machinery and influences

H3K4me3, loss of WT1 function reduces this activation landscape at key

differentiation genes, therefore block nephron maturation and promote tumor growth [

43]. Mutations in

H3K4 methyltransferases (e.g., MLL1-4, SETD1A/B) or

demethylases (e.g., KDM5 family) can disrupt normal kidney development [

44,

45]. WT often exhibit abnormal retention of bivalent marks, silencing genes crucial for renal differentiation and causing aberrant transcriptional programs [

44,

45] .

Bivalent domains are genomic regions marked by

both H3K4me3 (activation signal) and H3K27me3 (repression signal). These are common in

embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and

progenitor cells, keeping genes "poised" for activation or silencing during differentiation [

7].

In conclusion, the H3K27me3-H3K4me3 interplay is a

master regulator of WT biology, influencing

stemness, differentiation, and aggressiveness. In contrast with the overexpression of EZH2,

KDM6A, a demethylase that removes H3K27me3 and promotes gene activation, may be under expressed or functionally impaired, leading to persistent repression of critical developmental regulators. These alterations highlight a complex interplay of histone methylation dynamics that drive WT pathogenesis and offer promising targets for

epigenetic therapies aiming to restore proper chromatin states.

Histone modification dysregulation is increasingly recognized as a critical contributor to WT development and progression. Aberrant patterns of histone acetylation, methylation, and other post-translational modifications disrupt normal gene expression programs essential for renal differentiation, leading to uncontrolled proliferation and tumorigenesis. Among these modifications, the activity of HDACs has emerged as particularly important, as their aberrant function can silence tumor suppressor genes and maintain the undifferentiated state of tumor cells. Targeting histone-modifying enzymes, especially through HDAC inhibitors, offers a promising therapeutic strategy for restoring normal epigenetic control and inhibiting tumor progression. Continued research into the specific histone modification patterns and their regulatory enzymes in Wilms tumor will be essential for developing more effective and targeted epigenetic therapies.

Non-Coding RNA

Non-coding RNA (ncRNA) refers to RNA molecules that are not translated into proteins, unlike messenger RNA (mRNA) which carries the code for protein synthesis. ncRNAs regulate gene expression at various levels, including chromatin structure, transcription, and post-transcriptional processes. They are dysregulated in various cancers and can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. These ncRNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs

(circRNAs), influence multiple cancer hallmarks like proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and metastasis [

46].

miRNAs are ~22-nucleotide RNAs that suppress gene expression by targeting messenger RNAs (mRNAs) for degradation or translational inhibition. The miR-17-92 cluster, a group of microRNAs, is often overexpressed in Wilms' tumors and is implicated in promoting tumorigenesis. It has been shown to evade apoptosis, disrupt senescence, and enhance oncogenic transformation. Specifically, miR-17 and miR-20a within the cluster can inhibit senescence by targeting p21WAF1. Additionally, the cluster can suppress apoptosis by targeting PTEN through miR-19 components [

47]. A recent study revealed that expression of miR-204 in WT tissues were significantly lower than that in adjacent normal tissues [

48]. Conversely, tumor tissue had a higher miR-485-5p expression than the adjacent normal tissues [

48]. miR-204 could be a novel biomarker for anaplastic tumor and may be a useful target for developing therapeutic interventions [

48]. The

let-7 family of microRNAs plays an important

tumor-suppressive role in many cancers, including

WT [

49]. Its dysregulation is a key feature in WT pathogenesis, often in connection with

LIN28 overexpression. Mouse models overexpressing

LIN28 in renal progenitors develop

WT–like lesions, and these are characterized by

low let-7 expression [

49].

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcripts >200 nucleotides that regulate gene expression through chromatin remodeling, transcriptional control, and miRNA sponging. Several lncRNAs have been implicated in WT development, including LINC00473, SOX21-AS1, LINC00667, SNHG6, HOXA11-AS, MYLK-AS1, and XIST [

50]. These lncRNAs have been shown to play different roles in WT development, including promoting cell proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis, and regulating cell cycle progression [

51]. TUG1 is a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) that has been implicated in various cancers. Studies suggest that TUG1 expression may be altered in WTs, potentially influencing tumor cell growth, migration, and invasion [

52]. While there is no direct "Tug1" treatment for WT, research indicates TUG1 may play a role in tumor development and progression [

53]. In WT, the lncRNA MALAT1 is found to be downregulated in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues [

54]. This downregulation suggests that MALAT1 may act as a tumor suppressor or a prognostic biomarker for Wilms' tumor. Additionally, MALAT1 expression can be detected in exosomes, which are extracellular vesicles that carry cargo including nucleic acids and proteins for cellular communication [

54].

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are covalently closed-loop RNAs that act as miRNA sponges, regulate transcription, or interact with RNA-binding proteins. circCDYL is identified as a tumor suppressor in WT, as its overexpression suppresses cell proliferation, migration, and invasion both in vitro and in vivo [

55]. Emerging evidence suggests circRNAs play important roles in

pediatric cancers, including

WT, where they modulate oncogenic and tumor-suppressive pathways. CircCDYL acts by targeting miR-145-5p, a microRNA that regulates the expression of genes involved in tumor growth and metastasis [

55]. The study by Cao et al. (2021) found that circ0093740 is upregulated in WT cells and tissues. Suppressing circ0093740 inhibits cell proliferation and migration [

56]. Mechanistically, circ0093740 promotes tumor growth and metastasis by sponging miR-136/145 and upregulating DNMT3A, a DNA methyltransferase [

56]. The study by Zhou et al. (2022) suggests that circRNAs are involved in the ceRNA (competing endogenous RNA) network in WT. This network involves circRNAs, microRNAs, and mRNAs, where circRNAs act as miRNA sponges, regulating the expression of their target mRNAs [

57]. Although circRNA research in WT is in early stages, available evidence highlights their

regulatory importance in tumor biology. Further

experimental validation and

clinical correlation studies are needed to fully elucidate their potential as biomarkers or therapeutic targets.

In summary, WT exhibits a complex epigenetic landscape beyond LOI of IGF2, involving DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNA expression, and WT1 influence. These changes are often associated with specific genomic regions, like 11p15, and contribute to the development and progression of the tumor.

Therapeutic Implications of Epigenetic Regulation in WT

WT (WT) is one of the most curable pediatric malignancies, with overall survival rates exceeding 90% for patients with favorable histology [

58]. Current treatments are risk-stratified and multimodal, combining surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy where indicated. Surgical excision is the foundation of WT management. Most children undergo unilateral nephrectomy, although nephron-sparing surgery is increasingly utilized in bilateral or predisposed cases [

59]. Chemotherapy regimens, typically involving vincristine, dactinomycin, and doxorubicin, are administered based on tumor stage and histology. These protocols are informed by Children's Oncology Group (COG) and International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) trials [

58]. Radiation is used selectively for Stage III/IV tumors, particularly those with anaplastic histology or pulmonary metastases. Radiation therapy improves local control but is carefully balanced against long-term toxicity [

1]. While WT has relatively few recurrent mutations, alterations in pathways like IGF2, WNT, and mTOR offer opportunities for molecular intervention. Despite the promise, these agents are not yet standard due to mixed efficacy and concerns over pediatric toxicity

. Furthermore, outcomes for patients with diffuse anaplasia, recurrence, or chemoresistance remain suboptimal, underscoring the need for more targeted and less toxic therapies.

Increasing evidence highlights the critical role of epigenetic mechanisms in the initiation and progression of WT. These epigenetic changes are reversible, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention. The genetic mutations of WT are diverse. Of interest, the mutated genes are often epigenetic regulators. Epigenetic dysregulation plays a pivotal role in WTigenesis, and provides the rationale for targets to treat WT. DNMT inhibitors, such as azacytidine (Vidaza) and decitabine (Dacogen), can disrupt DNA methylation patterns by inhibiting DNMT activity [

60]. Some studies have specifically investigated the use of DNMT inhibitors in combination with other treatments for WTs, showing promising results in preclinical models and potentially in clinical trials. [

41]. While standard treatment involves surgery and chemotherapy, DNMT inhibitors could offer a new approach to address the genetic and epigenetic alterations that contribute to WT development and progression [

15]. HDACs) play a significant role in WT development and progression. Overactivation of HDACs, particularly HDAC1 and HDAC2, has been linked to unrestrained proliferation of progenitor cells, a key factor in WT formation [

28]. Less-differentiated blastemal type of WT often relapses. Recently, Ma et al. generate a cell model (namely of WiT49-PRCsP) that recapitulates blastemal WT, enabling the discovery of therapeutic vulnerability for high-risk WTs. [

29]. The drug screening identified a marked hypersensitivity of both epithelial- and blastemal-predominant WT patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) to HDAC inhibitors [

29]. Among the compounds tested, panobinostat and romidepsin demonstrated the most potent antitumor effects across both histologic subtypes. Panobinostat, a pan-HDAC inhibitor, exhibited broad activity but was associated with increased toxicity, likely due to its inhibition of multiple HDAC isoforms. In contrast, romidepsin, which selectively targets HDAC1 and HDAC2, showed a more favorable therapeutic profile [

29]. Nevertheless, several HDCA inhibitors are FDA-approved anti-cancer drugs, HDAC inhibitors may offer a promising approach for the treatment of WT, especially high-risk, metastatic WTs [

28,

29]. In addition to HDACs, EZH2 is

overexpressed in WT, particularly in blastemal components, and contributes to

transcriptional repression of tumor suppressors and differentiation genes. EZH2 expression is elevated in human WT specimens and WiT49-PRCsP cells [

28,

29]. The role of EZH2 in WT has led to research on targeting this protein as a potential therapeutic approach. EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat has been FDA approved for the treatment of sarcoma, suggesting their potential in treating this type of cancer. Study of tazemetostat in pediatric solid tumors including WT is undergoing. Aberrant patterns of histone modifications identified in WT highlights epigenetic enzymes as potential therapeutic targets (

Table 2) [

29,

61]. Epigenetic therapies may work synergistically (e.g., EZH2 + HDAC or DNMT + HDAC inhibitors) to restore differentiation, inhibit proliferation, and overcome drug resistance.

In summary, epigenetic dysregulation plays a central role in the pathogenesis and heterogeneity of WT, particularly through the aberrant activity of chromatin-modifying enzymes such as HDACs and EZH2. These regulators contribute to the maintenance of an undifferentiated, progenitor-like tumor state by repressing genes involved in differentiation and tumor suppression. Preclinical studies demonstrating the sensitivity of WT models—especially blastemal-predominant subtypes—to HDAC and EZH2 inhibitors underscore the therapeutic potential of targeting these epigenetic mechanisms. Selective HDAC1/2 inhibitors like romidepsin, and EZH2 inhibitors such as tazemetostat, offer promising avenues for intervention with potentially fewer off-target effects. Moreover, combination strategies that concurrently inhibit multiple epigenetic regulators may further enhance tumor differentiation and reduce resistance. As our understanding of the epigenomic landscape in WT continues to evolve, integrating epigenetic therapies into precision treatment approaches holds significant promise for improving outcomes in high-risk and refractory disease.

Conclusion and Perspective

Epigenetic regulation is a fundamental driver of WT biology. Dysregulation of DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs contributes to the disruption of normal nephrogenesis, often leading to the development of this pediatric kidney malignancy. Key epigenetic modifiers, including HDACs and EZH2, are aberrantly expressed in WT and contribute to the maintenance of a progenitor-like, undifferentiated state, particularly in the aggressive blastemal subtype. Recent advances in epigenetic profiling have identified potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets, offering new avenues for precision medicine in WT treatment. Accumulating evidence from preclinical studies demonstrates that targeting these epigenetic mechanisms can suppress tumor growth, promote differentiation, and enhance therapeutic sensitivity. Selective inhibitors of HDAC1/2 and EZH2 are particularly promising and may offer more precise therapeutic options with reduced toxicity compared to broader epigenetic drugs.

However, challenges remain in understanding the complex interplay between genetic and epigenetic alterations, as well as their dynamic changes during tumor progression. Future research should focus on integrating multi-omics approaches to unravel the epigenetic landscape of WT, enabling the development of targeted therapies that restore normal epigenetic control. Additionally, exploring the role of the tumor microenvironment and epigenetic plasticity could further improve clinical outcomes. Looking forward, the integration of epigenetic profiling into clinical diagnostics could refine risk stratification and identify patients most likely to benefit from targeted epigenetic therapies. Combination strategies that incorporate epigenetic modulators with conventional chemotherapy or emerging immunotherapies hold the potential to overcome resistance and improve long-term outcomes. Furthermore, understanding how developmental epigenetic programs are hijacked in WT may reveal novel targets and biomarkers. A deeper investigation into the tumor-specific epigenetic landscape will pave the way for novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, ultimately advancing precision medicine in pediatric renal oncology.

Acknowledgment

Great thanks to Dr. Samir El-Dahr for critically reading and editing this manuscript. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Louisiana Board of Regents Support Fund (LEQSF-RD-A-18) and Tulane University Carol Lavin Bernick Faculty Grants.

References

- Neagu, M.C.; David, V.L.; Iacob, E.R.; Chiriac, S.D.; Muntean, F.L.; Boia, E.S. Wilms' Tumor: A Review of Clinical Characteristics, Treatment Advances, and Research Opportunities. Medicina (Kaunas) 2025, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.; Gao, H.; Ma, W.; Liu, X.; Chang, M.; Sun, F. Identification of the expression patterns and potential prognostic role of m6A-RNA methylation regulators in Wilms Tumor. BMC Med Genomics 2023, 16, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, P.; Beckwith, J.B.; Mishra, K.; Zuppan, C.; Weeks, D.A.; Breslow, N.; Green, D.M. Focal versus diffuse anaplasia in Wilms tumor--new definitions with prognostic significance: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group. Am J Surg Pathol 1996, 20, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenstein, P.; Pritchard-Jones, K.; Charlton, J. The yin and yang of kidney development and Wilms' tumors. Genes Dev 2015, 29, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, R.H.; Murray, A.; Baskcomb, L.; Turnbull, C.; Loveday, C.; Al-Saadi, R.; Williams, R.; Breatnach, F.; Gerrard, M.; Hale, J.; et al. Stratification of Wilms tumor by genetic and epigenetic analysis. Oncotarget 2012, 3, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, E.M.; Ortiz, M.V.; Kennedy, J.A.; Glodzik, D.; Fleischut, M.H.; Duffy, K.A.; Hathaway, E.R.; Heaton, T.; Gerstle, J.T.; Steinherz, P.; et al. 11p15.5 epimutations in children with Wilms tumor and hepatoblastoma detected in peripheral blood. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc 2020, 126, 3114–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiden, A.P.; Rivera, M.N.; Rheinbay, E.; Ku, M.; Coffman, E.J.; Truong, T.T.; Vargas, S.O.; Lander, E.S.; Haber, D.A.; Bernstein, B.E. Wilms tumor chromatin profiles highlight stem cell properties and a renal developmental network. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 6, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.V.C.; Bourc'his, D. The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonar, S.; Nyahatkar, S.; Kalele, K.; Adhikari, M.D. Role of DNA methylation in cancer development and its clinical applications. Clin Transl Discov 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, J.V.D.; Pereira, B.M.D.; da Cruz, J.G.V.; Scherer, N.D.; Furtado, C.; de Azevedo, R.M.; de Oliveira, P.S.L.; Faria, P.; Boroni, M.; de Camargo, B.; et al. Genes Controlled by DNA Methylation Are Involved in Wilms Tumor Progression. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiala, E.M.; Ortiz, M.V.; Kennedy, J.A.; Glodzik, D.; Fleischut, M.H.; Duffy, K.A.; Hathaway, E.R.; Heaton, T.; Gerstle, J.T.; Steinherz, P.; et al. 11p15.5 epimutations in children with Wilms tumor and hepatoblastoma detected in peripheral blood. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc 2020, 126, 3114–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anvar, Z.; Acurzio, B.; Roma, J.; Cerrato, F.; Verde, G. Origins of DNA methylation defects in Wilms tumors. Cancer Lett 2019, 457, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Lu, Z.; Lei, H.; Lai, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, Z.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, J.; He, Z. DNA Methylation Data-Based Classification and Identification of Prognostic Signature of Children With Wilms Tumor. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 683242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albasha, S.A.; Almotawa, M.Z.; Alsaleh, A.A.; Alibrahim, N.N.; Radwan, Z.H.; Alhashem, Y.N.; Almatouq, J.; Alamoudi, M.K. In Silico Analysis of DNA Methylation Status of T-Cell Inflamed Signature Reveals a Therapeutic Strategy to Improve Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Efficacy in Wilms Tumor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2023, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, J.; Pereira, B.M.S.; Cruz, J.; Scherer, N.M.; Furtado, C.; Montalvao de Azevedo, R.; Oliveira, P.S.L.; Faria, P.; Boroni, M.; de Camargo, B.; et al. Genes Controlled by DNA Methylation Are Involved in Wilms Tumor Progression. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Du, J.; Jiang, H.; Chen, G.; Feng, X.; Gu, H. Identification of m6A-associated genes as prognostic and immune-associated biomarkers in Wilms tumor. Discov Oncol 2023, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Mo, J.; Liao, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B. The RNA m(6)A writer WTAP in diseases: structure, roles, and mechanisms. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Guo, K.X.; Li, J.; Xu, S.H.; Zhu, H.; Yan, G.R. Regulations of m(6)A and other RNA modifications and their roles in cancer. Front Med 2024, 18, 622–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. The roles of histone modifications in tumorigenesis and associated inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Cent 2022, 2, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Shi, P.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, C.; Cui, H. Molecular Mechanisms of MYCN Dysregulation in Cancers. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 625332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez Martin, O.; Schlosser, A.; Furtwangler, R.; Wegert, J.; Gessler, M. MYCN and MAX alterations in Wilms tumor and identification of novel N-MYC interaction partners as biomarker candidates. Cancer Cell Int 2021, 21, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Perez, M.V.; Henley, A.B.; Arsenian-Henriksson, M. The MYCN Protein in Health and Disease. Genes (Basel) 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Bellew, C.; Yao, X.; Stefkova, J.; Dipp, S.; Saifudeen, Z.; Bachvarov, D.; El-Dahr, S.S. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity is critical for embryonic kidney gene expression, growth, and differentiation. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 32775–32789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H. The roles of histone deacetylases in kidney development and disease. Clin Exp Nephrol 2021, 25, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Chen, S.; Yao, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.H.; Liu, J.; Saifudeen, Z.; El-Dahr, S.S. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 regulate the transcriptional programs of nephron progenitors and renal vesicles. Development 2018, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ngo, N.Y.N.; Herzberger, K.F.; Gummaraju, M.; Hilliard, S.; Chen, C.H. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 target gene regulatory networks of nephron progenitors to control nephrogenesis. Biochem Pharmacol 2022, 206, 115341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Liu, D.H.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, X.M.; Yuan, L.Q.; Pan, J.; Fu, M.C.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J. Histone deacetylase 5 promotes Wilms' tumor cell proliferation through the upregulation of c-Met. Mol Med Rep 2016, 13, 2745–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Ngo, N.Y.N.; Wang, A.; El-Dahr, S.; Liu, H. Overactivation of histone deacetylases and EZH2 in Wilms tumorigenesis. Genes Dis 2023, 10, 1783–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Gao, A.; Chen, J.; Liu, P.; Sarda, R.; Gulliver, J.; Wang, Y.; Joiner, C.; Hu, M.; Kim, E.J.; et al. Modeling high-risk Wilms tumors enables the discovery of therapeutic vulnerability. Cell Rep Med 2024, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Lu, X.; Bazai, S.K.; Dainese, L.; Verschuur, A.; Dumont, B.; Mouawad, R.; Xu, L.; Cheng, W.; Yan, F.; et al. Delineating the interplay between oncogenic pathways and immunity in anaplastic Wilms tumors. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, M.S.; Heinzel, T.; Englert, C. TSA downregulates Wilms tumor gene 1 (Wt1) expression at multiple levels. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, 4067–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, G.; Liu, C.; Huang, B. Histone acetyltransferase p300 promotes the activation of human WT1 promoter and intronic enhancer. Arch Biochem Biophys 2005, 436, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lee, S.B.; Palmer, R.; Ellisen, L.W.; Haber, D.A. A functional interaction with CBP contributes to transcriptional activation by the Wilms tumor suppressor WT1. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 16810–16816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Parejo Drayer, P.; Seeherunvong, W.; Katsoufis, C.P.; DeFreitas, M.J.; Seeherunvong, T.; Chandar, J.; Abitbol, C.L. Spectrum of Clinical Manifestations in Children With WT1 Mutation: Case Series and Literature Review. Front Pediatr 2022, 10, 847295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.C.; Min, H.Y.; Jung, H.J.; Park, K.H.; Hyun, S.Y.; Cho, J.; Woo, J.K.; Kwon, S.J.; Lee, H.J.; Johnson, F.M.; et al. Essential role of insulin-like growth factor 2 in resistance to histone deacetylase inhibitors. Oncogene 2016, 35, 5515–5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Hilliard, S.; Kelly, E.; Chen, C.H.; Saifudeen, Z.; El-Dahr, S.S. The polycomb proteins EZH1 and EZH2 co-regulate chromatin accessibility and nephron progenitor cell lifespan in mice. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 11542–11558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straining, R.; Eighmy, W. Tazemetostat: EZH2 Inhibitor. J Adv Pract Oncol 2022, 13, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Shi, B.; Zhu, K.; Zhong, X.; Lai, D.; Wang, J.; Tou, J. Bioinformatical analysis of the key differentially expressed genes for screening potential biomarkers in Wilms tumor. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 15404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, J.; Williams, R.D.; Sebire, N.J.; Popov, S.; Vujanic, G.; Chagtai, T.; Alcaide-German, M.; Morris, T.; Butcher, L.M.; Guilhamon, P.; et al. Comparative methylome analysis identifies new tumour subtypes and biomarkers for transformation of nephrogenic rests into Wilms tumour. Genome Med 2015, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp, S.; Chuah, S.M.; Halasz, M. Epigenetic Dysregulation in MYCN-Amplified Neuroblastoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschietto, M.; Charlton, J.; Perotti, D.; Radice, P.; Geller, J.I.; Pritchard-Jones, K.; Weeks, M. The IGF signalling pathway in Wilms tumours - A report from the ENCCA Renal Tumours Biology-driven drug development workshop. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 8014–8026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanets, A.; Shorstova, T.; Hilmi, K.; Marques, M.; Witcher, M. Epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes: Paradigms, puzzles, and potential. Bba-Rev Cancer 2016, 1865, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waehle, V.; Ungricht, R.; Hoppe, P.S.; Betschinger, J. The tumor suppressor WT1 drives progenitor cell progression and epithelialization to prevent Wilms tumorigenesis in human kidney organoids. Stem Cell Rep 2021, 16, 2107–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.; Li, X. Current Epigenetic Insights in Kidney Development. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilliard, S.A.; El-Dahr, S.S. Epigenetics mechanisms in renal development. Pediatr Nephrol 2016, 31, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, F.J.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. The Role of Non-coding RNAs in Oncology. Cell 2019, 179, 1033–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Chan, M.T.; Wu, W.K. The roles of microRNAs in Wilms' tumors. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgen Calli, A.; Issin, G.; Yilmaz, I.; Ince, D.; Tural, E.; Guzelis, I.; Cecen, R.E.; Olgun, H.N.; Gokcay, D.; Ozer, E. The association of miR-204 and mir-483 5p expression with clinicopathological features of Wilms tumor: Could this provide foresight? Jpn J Clin Oncol 2023, 53, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, A.; Yermalovich, A.; Zhang, J.; Spina, C.S.; Zhu, H.; Perez-Atayde, A.R.; Shukrun, R.; Charlton, J.; Sebire, N.; Mifsud, W.; et al. Lin28 sustains early renal progenitors and induces Wilms tumor. Genes Dev 2014, 28, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. The Emerging Landscape of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Wilms Tumor. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xiong, Q.W.; Wang, J.H.; Peng, W.X. Roles of lncRNAs in childhood cancer: Current landscape and future perspectives. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1060107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.B.; Zhuang, J.; Gong, L.; Dai, Y.; Diao, H.Y. Investigating the dysfunctional pathogenesis of Wilms' tumor through a multidimensional integration strategy. Ann Transl Med 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Sun, L.N.; Wan, F.S. Molecular mechanisms of TUG1 in the proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion of cancer cells. Oncol Lett 2019, 18, 4393–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Singh, A.; Wilson, C.; Swaroop, P.; Kumar, S.; Yadav, D.K.; Jain, V.; Agarwala, S.; Husain, M.; Sharawat, S.K. Exosomal long non-coding RNA MALAT1: a candidate of liquid biopsy in monitoring of Wilms' tumor. Pediatr Surg Int 2024, 40, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Jia, W.; Gao, X.; Deng, F.; Fu, K.; Zhao, T.; Li, Z.; Fu, W.; Liu, G. CircCDYL Acts as a Tumor Suppressor in Wilms' Tumor by Targeting miR-145-5p. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 668947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Huang, Z.; Ou, S.; Wen, F.; Yang, G.; Miao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Shan, Y.; et al. circ0093740 Promotes Tumor Growth and Metastasis by Sponging miR-136/145 and Upregulating DNMT3A in Wilms Tumor. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 647352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.M.; Xiang, B.; Zhang, Z.X.; Li, Y.P.; Shi, Q.L.; Li, M.J.; Li, Q.; Yu, Y.H.; Lu, P.; Liu, F.; et al. The Regulatory Network and Role of the circRNA-miRNA-mRNA ceRNA Network in the Progression and the Immune Response of Wilms Tumor Based on RNA-Seq. Frontiers in Genetics 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, N.; Kajal, P.; Sharma, U. Many faces of Wilms Tumor: Recent advances and future directions. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2021, 64, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, E.J. Pediatric renal tumors: practical updates for the pathologist. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2005, 8, 320–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnyszka, A.; Jastrzebski, Z.; Flis, S. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors and their emerging role in epigenetic therapy of cancer. Anticancer Res 2013, 33, 2989–2996. [Google Scholar]

- Brok, J.; Mavinkurve-Groothuis, A.M.C.; Drost, J.; Perotti, D.; Geller, J.I.; Walz, A.L.; Geoerger, B.; Pasqualini, C.; Verschuur, A.; Polanco, A.; et al. Unmet needs for relapsed or refractory Wilms tumour: Mapping the molecular features, exploring organoids and designing early phase trials - A collaborative SIOPRTSG, COG and ITCC session at the first SIOPE meeting. Eur J Cancer 2021, 144, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

EZH2 serves as both a biomarker for aggressive disease and a potential therapeutic target in WT.

Table 1.

EZH2 serves as both a biomarker for aggressive disease and a potential therapeutic target in WT.

| Role |

Details |

Reference(s) |

| Diagnostic Biomarker |

EZH2 overexpression is common in WT compared to normal kidney tissue. It can help distinguish tumor tissue from normal or benign kidney lesions in some cases. |

[28] |

| Prognostic Biomarker |

High levels of EZH2 correlate with poor prognosis in many cancers. In WT, higher EZH2 expression has been associated with worse differentiation and potentially more aggressive tumor behavior, but this link needs more clinical validation. |

[38] |

| Predictive Biomarker |

EZH2 expression could predict response to EZH2 inhibitors in the future — though this is still at an experimental stage for WT. |

[1,38] |

| Therapeutic Target |

Beyond being a marker, EZH2 is an active target: inhibiting it might reverse the block in differentiation that drives WT growth. |

[28] |

Table 2.

The summary of histone modification inhibitors potential for the treatment of Wilms Tumor.

Table 2.

The summary of histone modification inhibitors potential for the treatment of Wilms Tumor.

| Names |

Target(s) |

Mechanism |

Potential Relevance in Wilms Tumor |

Development Status |

| Panobinostat |

HDAC (Class I, II, IV) |

Broad-spectrum HDAC inhibitor; induces apoptosis, cell cycle arrest |

May target aberrant epigenetics in Wilms tumor; preclinical studies needed |

FDA-approved (myeloma) |

| Vorinostat (SAHA) |

HDAC (Class I, II) |

Promotes histone acetylation, reactivates tumor suppressor genes |

Potential for differentiation therapy in Wilms tumor |

FDA-approved (myeloma) |

| Romidepsin |

HDAC (Class I) |

Selective HDAC1/2 inhibition; disrupts oncogenic pathways |

Possible synergy with chemotherapy in pediatric tumors |

FDA-approved (myeloma) |

| Tazemetostat (EPZ-6438) |

EZH2 (H3K27me3 methyltransferase) |

Blocks PRC2-mediated silencing of tumor suppressors |

EZH2 overexpression linked to poor prognosis; may inhibit Wilms tumor progression |

FDA-approved (epithelioid sarcoma) |

| GSK126 |

EZH2 inhibitor |

Reduces H3K27me3 marks, reactivates silenced genes |

Preclinical potential for Wilms tumors with EZH2 dysregulation |

Investigational |

| JQ1 |

BET (BRD4) inhibitor |

Targets bromodomains; suppresses MYC and other oncogenes |

MYC is implicated in Wilms tumor; may disrupt oncogenic transcription |

Preclinical |

| CPI-203 |

BET inhibitor |

Downregulates pro-proliferative genes |

Potential for high-risk Wilms tumor subtypes |

Investigational |

| Valproic Acid |

HDAC (Class I, IIa) |

Weak HDAC inhibitor; induces differentiation |

Possible adjunct therapy due to low toxicity in pediatrics |

FDA-approved (epilepsy) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).