Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Plant Appearance Characteristics of the C. majus

2.2. Prediction and Comparative Analysis of RNA Editing Sites

2.3. Codon Changes Caused By RNA Editing

2.4. Types of Mutations in Proteins Induced by RNA Editing

2.5. Effects on Physicochemical Properties and Conserved Domain of Sixteen Mutant Proteins by Chloroplast RNA Editing

2.6. Transmembrane Proteins and Signal Peptides by the RNA Editing

2.7. Comparative Analysis of RNA Editing Results Between Prediction and Experimental Validation

2.8. Structure Variety of RNA and Proteins Before and After RNA Editing

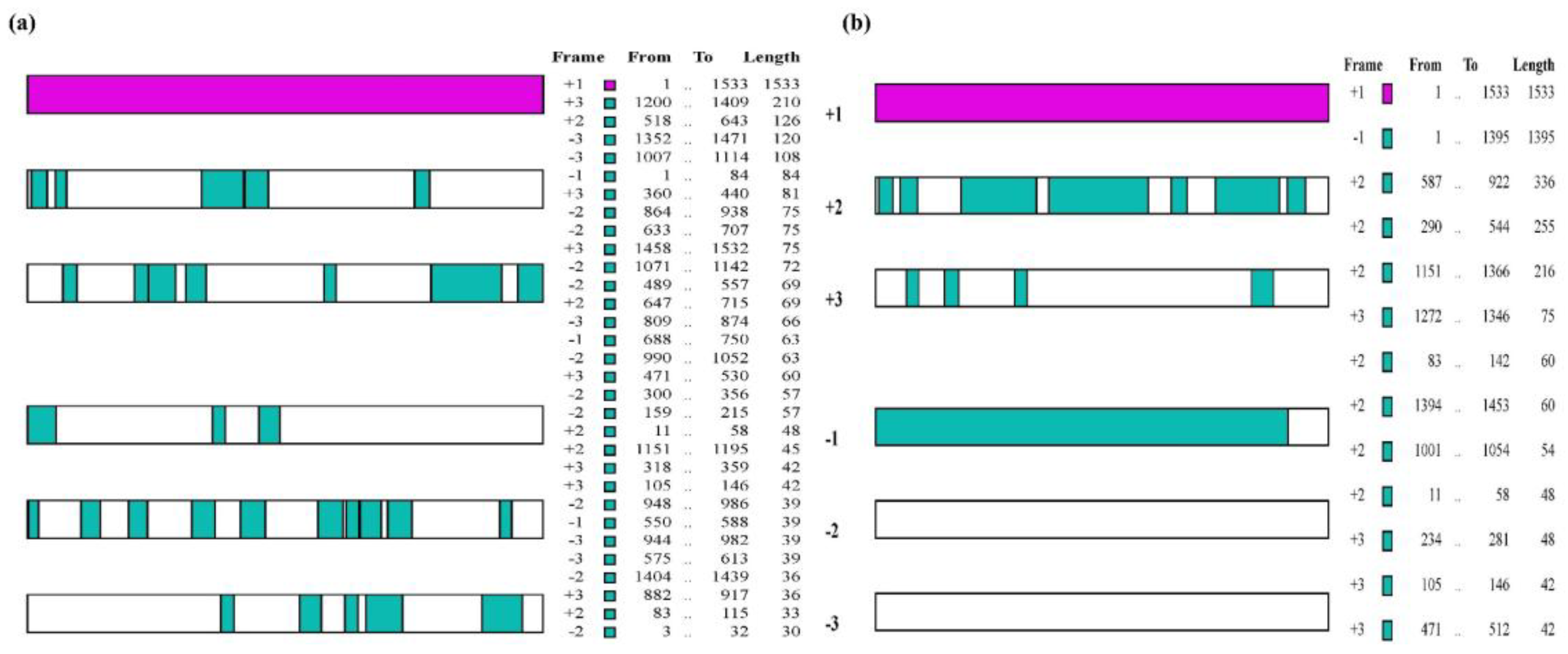

2.9. Prediction and Identification of Open Reading Frame (ORF) and Transcription Factors (TFs)

2.10. GO, KOG, and KEGG Pathway

3. Discussion

3.1. Significance of RNA Editing Occurring Within the CDS Genes in the Chloroplast Genome

3.2. RNA Editing of Chloroplast Genes Influenced the Alkaloid Chemicals

Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Photo and Materials

4.2. Sources of Chloroplast Genomes

4.3. Prediction of RNA Editing Sites and Protein Variation

4.4. Protein Feature and Structure, RNA Structure, and Functional Changes

4.5. Validation of RNA Editing by Using PCR and RT-PCR Experiment

4.6. Analysis of ORF and Transcription Factor

4.7. GO, KOG, and KEGG Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplemental materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PI | Isoelectric points |

| ORFs | Open reading frames |

| ZFN | Zinc-finger nucleases |

| PPRs | Pentapeptide repeat proteins |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction |

| GRAVY | Grand average of hydropathicity |

| SPs | Signal peptides |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| TFs | Transcription factors |

| DLT | Dark-light transition |

References

- Urnov, F.D.; Rebar, E.J.; Holmes, M.C.; Zhang, H.S.; Gregory, P. D. Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensel, G.; Kumlehn, J. Genome Engineering Using TALENs: Methods and Protocols. Mol. Biol. 2019, 195–215. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, D.; Bhattacharjee, O.; Mandal, D.; Sen, M.K.; Dey, D.; Dasgupta, A.; Kazi, T.A.; Gupta, R.; Sinharoy, S.; Acharya, K.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Ravichandiran, V.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, D. CRISPR-Cas9 system: A new-fangled dawn in gene editing. Life Sci, 2019, 232, 116636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Chen, M.; Li, D.; Lijavetzky, D. Editorial:Plant RNA processing: discovery, mechanism and function. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1359415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knoop, V. C-to-U and U-to-C: RNA editing in plant organelles and beyond. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 2273–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Liu, G.; Wang, W.; Shen, W.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, W.; Pei, S.; Chen, Z.; Xu, D.; Qin, T. RNA Editing and Its Roles in Plant Organelles. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 757109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, B.; Maier, R.M.; Appel, K.; Igloi, G.L.; Kössel, H. Editing of a chloroplast mRNA by creation of an initiation codon. Nature. 1991, 353, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, U.G.; Bozarth, A.; Funk, H.T.; Zauner, S.; Rensing, S.A.; Schmitz-Linneweber, C.; Börner, T.; Tillich, M. Complex chloroplast RNA metabolism: just debugging the genetic programme? BMC Biol. 2008, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, JK. Identification and analysis of RNA editing sites in the tobacco chloroplast genome. Mol. Plant Breed, 2020, 18, 6649–6656. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, X; Pei, Y; Hu, F.; Ren, M.M.; Wang, T.; Nie X.J. Predication, identification and characterization of the chloroplast RNA editing sites of Hulless barley. J. of triticeae crops. 2019, 39, 1316–1325.

- Ma, H. Z, Zhang, B.J.; Fan, H.L. Predication and identification of RNA editing sites in the chloroplast genomes of Barley (Hordeumvulgare L.). J. of triticeae crops. 2013, 33, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.X.; Zhan, H.S.; Lu, M.L; Liu, S.Y.; Song, W. N. Identification and analysis of RNA editing sites in chloroplast transcripts of Aegilops tauschii. J. of triticeae crops. 2014, 34, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Xie, B.; Peng, L.; Wu, Q.; Hu, J. Profiling of RNA editing events in plant organellar transcriptomes with high-throughput sequencing. Plant J. 2024, 118, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Miao, Y.; Liu, C.; & Huang, L. A Bibliometric Study for Plant RNA Editing Research:Trends and Future Challenges. Mol Biotechnol, 2023, 65, 1207-1227.

- Zhao, Y.; Gao, R.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, S.; Han, R.; Jeyaraj, A.; Arkorful, E.; Li, X.; Chen, X. Genome-wide identification of RNA editing sites in chloroplast transcripts and multiple organellar RNA editing factors in tea plant (Camellia sinensis L.): Insights into the albinism mechanism of tea leaves. Gene, 2023, 848, 146898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlas of China's higher plants D, 1972, 2, 3, Figure 1735.

- Li, X. L.; Sun, Y. P.; Wang, M.; Wang, Z. B.; Kuang, H. X. Alkaloids in Chelidonium majus L: a review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1440979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.Q.; Zou, X.; Qu, Z.Y.; Ji, Y.B. The research progress of chemical composition and pharmacological effects of Chelidonium majus. Chin. Trad. and Herb. Drugs, 2009, 40, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, S.L.; Li, L.R.; Gu, S.; Cai, M.C.; Li, X. Comprehensive research on the pharmacological effects of Chelidonium majus. Jilin traditional Chinese medicine, 2022, 42, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.Y.; He, J.; Peng, L. L.; Wang, A.; Zhao, L.C. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Chelidonium majus (Papaveraceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B, 2019, 4, 1206–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.J. Whole genome feature sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the chloroplast Chelidonium majus. Xiangnan College, 2023.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xie, J.; Zeng, R.; Guo, B.; Huang, L. The complete chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic relationship analysis of Eomecon chionantha, one species unique to China. J. Plant Res. 2024, 137, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmazaheri, H.; Soorni, A.; Kohnerouz, B.B.; Dehaghi, N.K.; Kalantar, E.; Omidi, M.; Naghavi, M.R. Comparative analysis of the root and leaf transcriptomes in Chelidonium majus L. PloS one, 2019, 14, e0215165.

- Nawrot, R.; Barylski, J.; Lippmann, R.; Altschmied, L.; Mock, H.P. Combination of transcriptomic and proteomic approaches helps to unravel the protein composition of Chelidonium majus L. milky sap. Planta, 2016, 244, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cui, X.; An, W.; Li, C.; Zhang, S.; Cao, M.; Yang, C. The complete genome sequence of a putative novel cytorhabdovirus identified in Chelidonium majus in China. Arch Virol. 2024, 169, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.B.; Xiang, G.M.; Xing, J.H. A taxonomic re-assessment in the Chinese Bupleurum (Apiaceae): Insights from morphology, nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer, and chloroplast (trnH-psbA, matK) sequences. J. of Plant Taxonomy. 2011, 49, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palhares, R. M.; Drummond, M. G.; Brasil, B. S.; Krettli, A. U.; Oliveira, G. C.; Brandão, M. G. The use of an integrated molecular-, chemical- and biological-based approach for promoting the better use and conservation of medicinal species: a case study of Brazilian quinas. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2014, 155, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Huang, X.Y.; Huang, M.Y.; Zhang, X.; Fan, J. Sequence variations of matK gene in Spiranthes plants and the effect on protein molecular interaction and function. Mol. Plant Breed, 2019, 17, 7017–7030. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Cui, J.; Wang, Q.M. Chimeric deletion mutation of rpoC2 underlies the leaf-patterning of Clivia miniata var. variegata. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Duan, F.; Li, X.; Zhao, R.; Hou, P.; Zhao, M.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Dai, T.; Zhou, W. Photosynthetic capacity and assimilate transport of the lower canopy influence maize yield under high planting density. Plant Physiology. 2024, 195, 2652–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q. The soybean NDH complex and its role in salt stress. Zhe Jiang University. 2012.

- Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, L.; Fang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Gong, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Bock, R.; Zhou, F. Accumulation of the RNA polymerase subunit RpoB depends on RNA editing by OsPPR16 and affects chloroplast development during early leaf development in rice. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.S. Mannose Receptor Family: R-Type Lectins. Springer Vienna. 2012, 331–347. [Google Scholar]

- Duart, G.; Graña-Montes, R.; Pastor-Cantizano, N.; & Mingarro, I. Experimental and computational approaches for membrane protein insertion and topology determination. Methods. 2024, 226, 102–119.

- Facchini P., J. ALKALOID BIOSYNTHESIS IN PLANTS: Biochemistry, Cell Biology, Molecular Regulation, and Metabolic Engineering Applications. Annual review of plant physiology and plant molecular biology. 2001, 52, 29–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahyazadeh, M.; Selmar, D.; Jerz, G. Electrospray-Mass Spectrometry-Guided Targeted Isolation of Indole Alkaloids from Leaves of Catharanthus roseus by Using High-Performance Countercurrent Chromatography. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2025, 30, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, M.; Shanker, K.; Samad, A.; Kalra, A.; Sundaresan, V.; Shukla, A. K. Stress responsiveness of vindoline accumulation in Catharanthus roseus leaves is mediated through co-expression of allene oxide cyclase with pathway genes. Protoplasma. 2022, 259, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, T.; Schoofs, G.; Wink, M. A chloroplast-localized lysine decarboxylase of Lupinus polyphyllus: the first enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of quinolizidine alkaloids. FEBS letters, 1980, 115, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, M.; Hartmann, T. Activation of chloroplast-localized enzymes of quinolizidine alkaloid biosynthesis by reduced thioredoxin. Plant cell reports. 1981, 1, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Tian, Y. X.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, X. R.; Lin, F. C.; Yang, J.; Tang, H. R. Variations of Alkaloid Accumulation and Gene Transcription in Nicotiana tabacum. Biomolecules. 2018, 8, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xie, K.; Yu, W.; Hu, L.; Huang, H.; Xie, H.; Wang, S. Nicotine dehydrogenase complexed with 6-Hydroxypseudooxynicotine oxidase involved in the hybrid nicotine-degrading pathway in Agrobacterium tumefaciens S33. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2016, 82, 1745–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, P.; Armarego-Marriott, T.; Bock, R. Plastid transformation and its application in metabolic engineering. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, S.; Forner, J.; Hasse, C.; Kroop, X.; Seeger, S.; Schollbach, L.; Schadach, A.; Bock, R. High-efficiency generation of fertile transplastomic Arabidopsis plants. Nature plants. 2019, 5, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, T.; Jiang, J.; Deng, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Fu, H.; Yang, B.; Zhang, L. The chloroplast GATA-motif of Mahonia bealei participates in alkaloid-mediated photosystem inhibition during dark to light transition. J. of plant physiology. 2023, 280, 153894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, H.; Hein, A.; Knoop, V. Plant organelle RNA editing and its specificity factors: enhancements of analyses and new database features in PREPACT 3.0. BMC Bioinformatics. 2018, 19, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Chen, H.; Jiang, M.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Huang, L.; Liu, C. CPGAVAS2, an integrated plastome sequence annotator and analyzer. Nucleic acids research. 2019, 47, W65–W73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, M. R.; Gasteiger, E.; Bairoch, A.; Sanchez, J. C.; Williams, K. L.; Appel, R. D.; Hochstrasser, D.F. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.). 1999, 112, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Gu, F.; Huang, Z. Improved Chou-Fasman method for protein secondary structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006, 7, S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M. K.; Gonzales, N. R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, C.; Lanczycki, C. J.; Marchler-Bauer, A. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.; Teufel, F.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne G. SignalP: The Evolution of a Web Server. In: Lisacek, F. (eds) Protein Bioinformatics. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2024, 2836.

- Hallgren, J.; Tsirigos, K. D.; Pedersen, M. D.; Armenteros, J. J. A.; Marcatili, P.; Nielsen, H.; Krogh, A.; and Winther, O. Deeptmhmm predicts alpha and beta transmembrane proteins using deep neural networks. bioRxiv. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F. T.; de Beer, T. A. P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; Lepore, R.; Schwede, T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsirigos, K. D.; Peters, C.; Shu, N.; Käll, L.; & Elofsson, A. The TOPCONS web server for consensus prediction of membrane protein topology and signal peptides. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015, 43, W401–W407.

- Viklund, H.; Bernsel, A.; Skwark, M.; Elofsson, A. SPOCTOPUS: a combined predictor of signal peptides and membrane protein topology. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2008, 24, 2928–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson S., A. EMBOSS opens up sequence analysis. European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2002, 3, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D. L.; Church, D. M.; Federhen, S.; Lash, A. E.; Madden, T. L.; Pontius, J. U.; Schuler, G. D.; Schriml, L. M.; Sequeira, E.; Tatusova, T. A.; Wagner, L. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology. Nucleic acids research. 2003, 31, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutet, E. , Lieberherr, D., Tognolli, M., Schneider, M., Bansal, P., Bridge, A. J., Poux, S., Bougueleret, L., & Xenarios, I. UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, the Manually Annotated Section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase: How to Use the Entry View. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.). 2016, 1374, 23–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Dumas, R.; Turchi, L.; Lucas, J.; & Parcy, F. Plant-TFClass: a structural classification for plant transcription factors. Trends in plant science. 2024, 29, 40–51.

- Harris, M. A.; Clark, J.; Ireland, A.; Lomax, J.; Ashburner, M.; Foulger, R.; Eilbeck, K.; Lewis, S.; Marshall, B.; Mungall, C.; Richter, J.; Rubin, G. M.; Blake, J. A.; Bult, C.; Dolan, M.; Drabkin, H.; Eppig, J. T.; Hill, D. P.; Ni, L.; Ringwald, M. Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic acids research. 2004, 32, D258–D261. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.; Yang, Y. iCAZyGFADB: an insect CAZyme and gene function annotation database. Database : the journal of biological databases and curation 2023, baad086.

- Nguyen, H.; Pham, V. D.; Nguyen, H.; Tran, B.; Petereit, J.; Nguyen, T. CCPA: cloud-based, self-learning modules for consensus pathway analysis using GO, KEGG and Reactome. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2024, 25, bbae222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The genes and numbers of RNA editing | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1(18) | 2(11) | 3(7) | 4(8) | 5(4) | 7(2) | 8(2) | 9(2) | 12(1) | 13(1) | 14(1) | 24(1) | 27(1) | 28(1) | 62(1) | 78(1) |

| ndhI, petB, petD, petG, psaB, psaI, psaJ, psbE, psbF, psbN, psbT, psbZ, rpl14, rpl16, rps11, rps14, rps19, rps3 | atpF, ndhC, psaA, psbC, psbJ, rps12, rps15, rps16, rps4, rps8, ycf3 | atpB, ndhH, ndhJ, ndhK, psbK, rpl20, rps18 | atpI, ndhE, petA, petL, rpl2, rpl22, rpl23, rps2 | cemA, clpP, ndhG, ycf4 | atpA, rpoA | accD, ccsA | ndhA, rpoC1 | ndhF | ndhD | rpoB | ndhB | matK | rpoC2 | ycf1 | ycf2 |

| Codon types and number | |||||||||||||||

| 28 | ACA→AUA, ACC→AUC, ACG→AUG, ACU→AUU, CAA→UAA, CAC→UAC, CAU→UAU, CCA→CUA, CCA→UCA, CCC→CUC, CCC→UCC, CCG→CUG, CCG→UCG, CCU→CUU, CCU→UCU, CGG→UGG, CGU→UGU, CUA→UUA, CUC→UUC, CUU→UUU, GCA→GUA, GCC→GUC, GCG→GUG, GCU→GUU, UCA→UUA, UCC→UUC, UCG→UUG, UCU→UUU | ||||||||||||||

| Types and number of amino acid mutations | |||||||||||||||

| 29 | 36 | 64 | 1 | 57 | 36 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 38 | 79 | 46 | 17 | |||

| A→V | H→Y | L→F | L→L | P→L | P→S | Q→* | R→C | R→W | S→F | S→L | T→I | T→M | |||

| Genes containing RNA editing sites | RNA secondary structure | Protein structure | Signal Peptide (Sec/SPI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| transmembrane domain number(before/after) | transmembrane domain affected | Homologous protein | affected | ɑ-helix | β-strand | Tertiary structure (best model) | Before mutation | After mutation | ||

| atpA | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | c6fkfA | - | - |

| ccsA | + | 8 | - | - | + | +1 | -1 | c7s9yA | - | - |

| ycf4 | + | 2 | - | - | + | + | +1 | c8keiD | - | - |

| cemA | + | 4 | - | - | + | -1 | +1 | c6ynyB | - | - |

| matK | + | - | - | - | + | -2 | + | c8h2hC | - | - |

| ndhA | + | 8 | - | 4heaH | + | +1 | -1 | c7eu3A/c7wffA | - | - |

| ndhB | + | 8~14/11~14 | + | 3rkoA | + | +1 | -2 | c7wffB | - | - |

| ndhD | + | 11~14/11~15 | + | 3rkoM | + | +4 | +2 | c7wffD | - | - |

| ndhF | + | 14~16 | - | 3rkoL | + | +2 | -2 | c7wffF | - | - |

| ndhG | + | 5 | + | 3rkoJ | + | + | -1 | c7wffG | - | - |

| rpoA | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | c8w9zB | - | - |

| rpoB | + | - | - | - | + | +2 | -2 | c8w9zC | - | - |

| rpoC1 | + | - | - | - | + | - | -2 | c8w9zD | - | - |

| rpoC2 | + | 3 | + | - | + | + | +1 | c1gprA | - | - |

| petA | + | 1 | - | 4h44C | + | - | -2 | c7zyvK | 0.9434 | 0.9179 |

| accD | + | - | - | - | + | -2 | +2 | c2f9iB | - | - |

| “+”representative the structures were affected by RNA editing. | ||||||||||

| “-”representative the structures were not affected by RNA editing or "No existing". | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).