Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.Introduction

2. Material and Methods

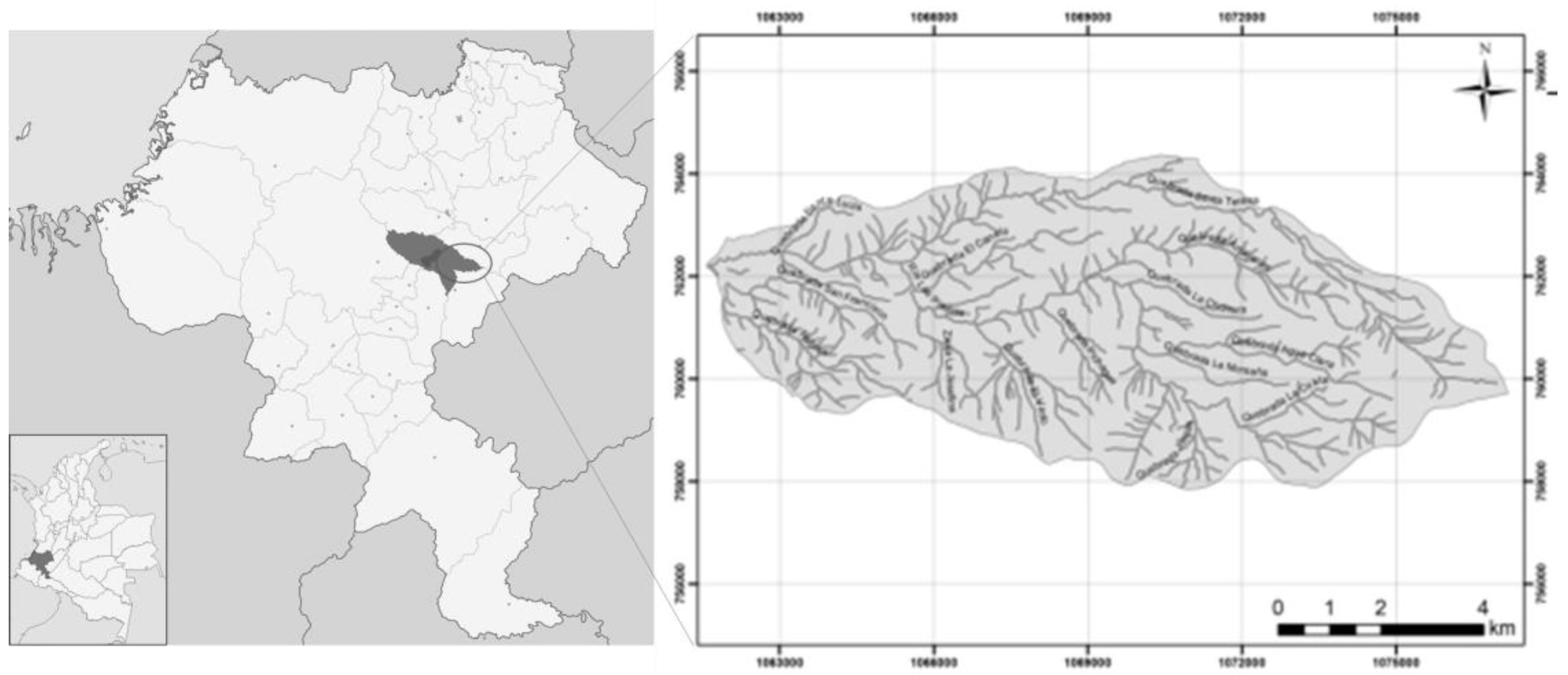

2.1. Site and Land Use Description

| Plant cover | |||

| Variables | RF | ER | NR |

| Basal area/ha (m2 ) | 15,75 ± 0,03 | 16,33 ± 0,02 | 6.08 ± 0,04 |

| No. trees/ha (DAP>0,1m) | 1538 ± 0,04 | 1485 ± 0,05 | 873 ± 0,08 |

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Determination of Soil Carbon Inputs and Outputs

2.2.2. Soil Sampling

2.3. Laboratory Analysis

2.3.1. Soil Chemical Properties

2.3.2. Soil Physical Properties

2.4. Socio-Ecological Information Recompilation

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

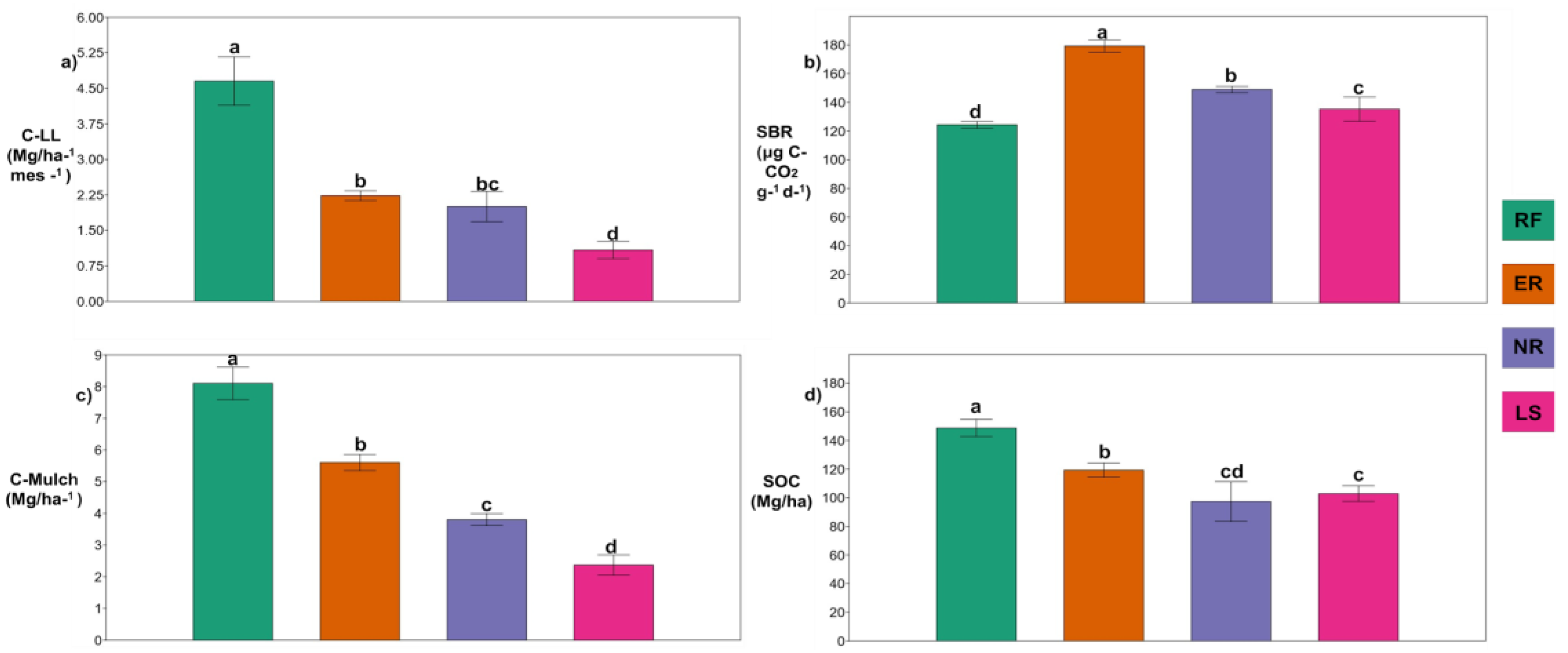

3.1. C Inputs and Outputs and SOC Storage in Different Land Uses

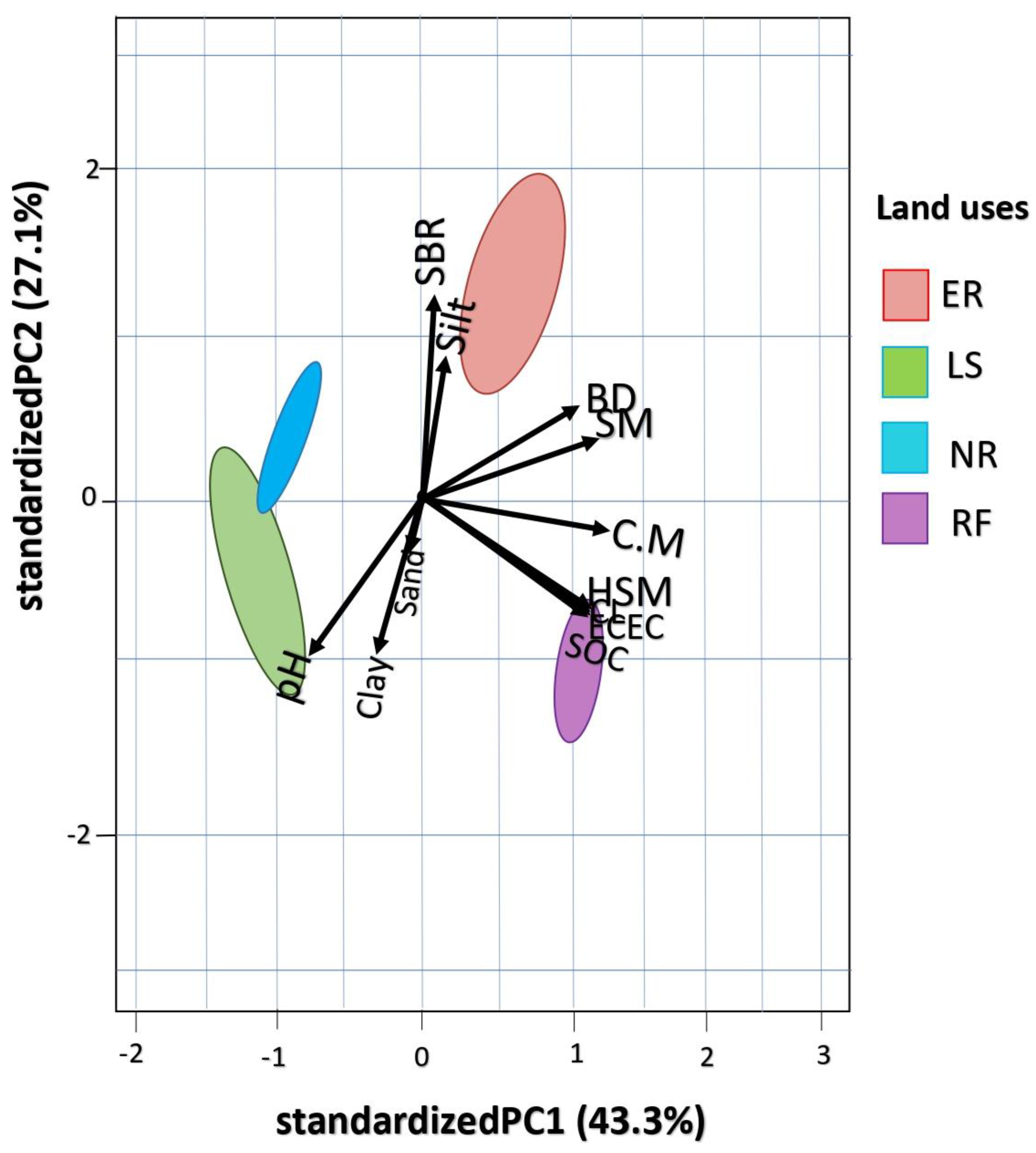

3.2. Physicochemical Properties

| SOIL CHARACTERISTICS | LAND USE | ||||

| RF | ER | NR | LS | ||

| Physical | BD (g/cm3) | 1,01a ± 0,01 | 1,06a ± 0,01 | 0,95ab ± 0,08 | 0,90b ± 0,02 |

| HSM (%) | 13,49a ± 0,40 | 11,32a ± 0,56 | 10,52c ± 0,55 | 10,08b ± 0,49 | |

| SM (%) | 64,96b ±0,80 | 65,97a ± 0,61 | 62,83c ± 0,25 | 62,75c ±0,72 | |

| Sand (%) | 73,41a ± 2,52 | 72,00b ± 3,01 | 73,50a ± 2,52 | 73,46a ± 2,52 | |

| Silt (%) | 21,01c ± 1,51 | 23,39a ± 3,03 | 22,40b ± 2,52 | 21,04c ± 2,00 | |

| Clay (%) | 5,58a ± 1,15 | 4,61ba ± 0,50 | 4,10b ± 0,50 | 5,50a ± 1,01 | |

| Chemical | SOC(Mg ha−1) | 148,68a ±6,07 | 119,24b ±5,04 | 97,30cd±14,13 | 102,85c ±5,55 |

| SBR (μg C-CO2 g −1 d−1) | 124,31d ±2,41 | 179,28a ±4,34 | 148,91b ±2,31 | 135,25c ±8,58 | |

| pH | 4,93a ± 0,05 | 5,14a ± 0,05 | 4,98ª ± 0,21 | 5,13a ± 0,16 | |

| ECEC (meq100 g-1 s) | 3,73c ± 0,21 | 4,21b ± 0,21 | 4,38b ± 0,39 | 5,70a ± 0,50 | |

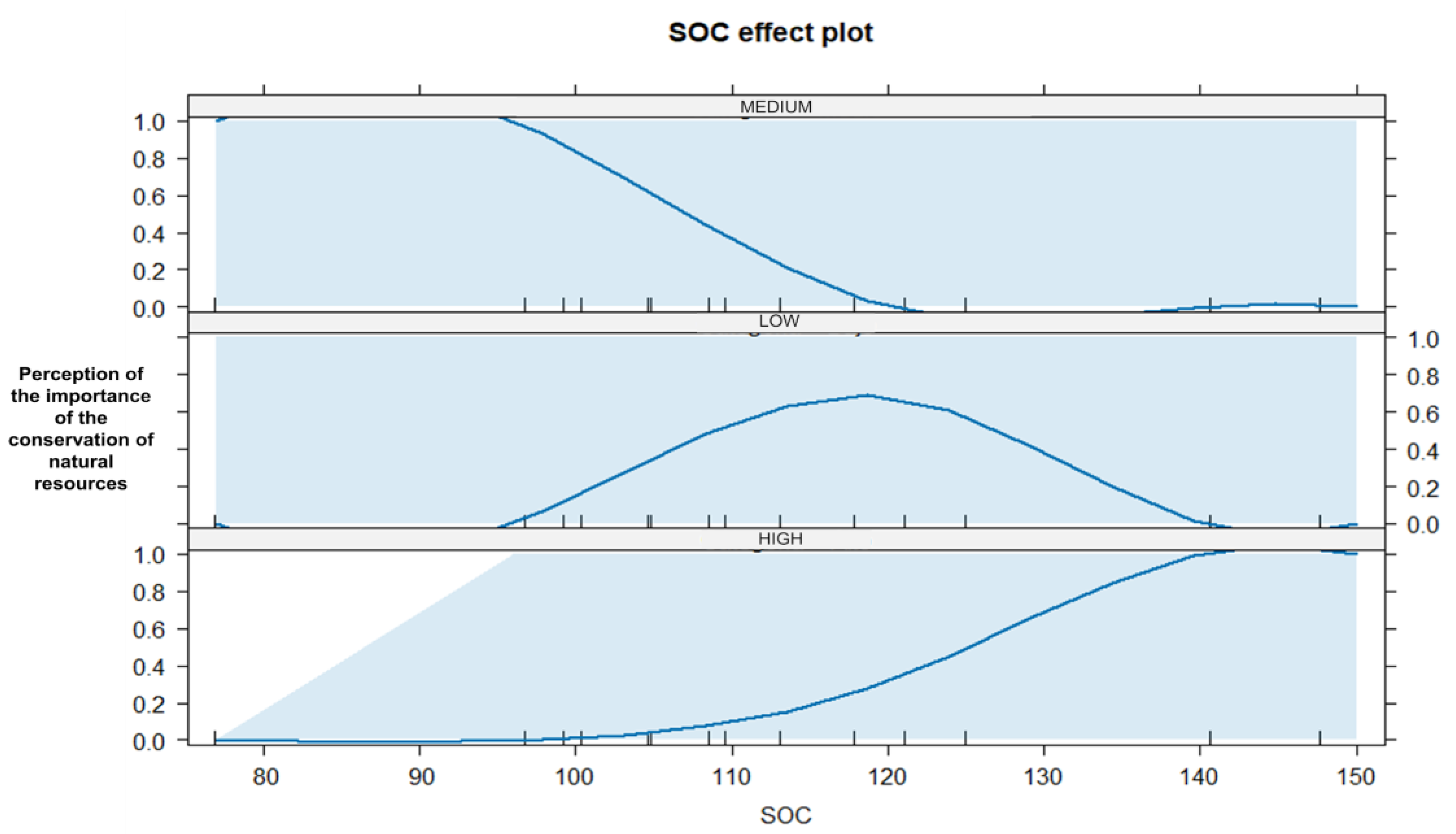

3.3. Multinomial Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

4.1. Carbon Stocks

4.2. Soil Properties and SOC in Different Land Use

4.3. Regression Model

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- E. H. Boakes, C. Dalin, A. Etard, and T. Newbold, “Impacts of the global food system on terrestrial biodiversity from land use and climate change,” Nat. Commun., vol. 15, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Ivanovich, T. Sun, D. R. Gordon, and I. B. Ocko, “Future warming from global food consumption,” Nat. Clim. Chang., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 297–302, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Aguilar, “Universidad de Murcia,” All rights Reserv. IJES, vol. 281, no. 4, pp. 1–30, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://digitum.um.es/digitum/bitstream/10201/93201/1/Karen Lissette Aguilar Duarte Tesis Doctoral.pdf.

- B. Harper et al., “Land-use emissions play a critical role in land-based mitigation for Paris climate targets,” Nat. Commun., vol. 9, no. 1, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. P. Anderson et al., “Consecuencias del Cambio Climático en los Ecosistemas y Servicios Ecosistémicos de los Andes Tropicales,” 2012.

- J. Sylvester et al., “A rapid approach for informing the prioritization of degraded agricultural lands for ecological recovery: A case study for Colombia,” J. Nat. Conserv., vol. 58, no. November 2019, p. 125921, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Berrio-Giraldo, C. Villegas-Palacio, and S. Arango-Aramburo, “Understating complex interactions in socio-ecological systems using system dynamics: A case in the tropical Andes,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 291, no. April, p. 112675, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tan and R. Lal, “Carbon sequestration potential estimates with changes in land use and tillage practice in Ohio, USA,” Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., vol. 111, no. 1–4, pp. 140–152, 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Krauss et al., “Reduced tillage in organic farming affects soil organic carbon stocks in temperate Europe,” Soil Tillage Res., vol. 216, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Lal, “Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security,” Science (80-. )., vol. 304, no. 5677, pp. 1623–1627, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Lefévre, F. Rekik, A. V, and L. Wiese, Carbono Orgánico del Suelo. 2017. [Online]. Available: www.fao.org/publications.

- Barman, P. Saha, S. Patel, and A. Bera, “Crop Diversification an Effective Strategy for Sustainable Agriculture Development,” 2022, Accessed: May 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?hl=es&lr=&id=HV17EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA89&dq=Crop+Diversification+an+Effective+Strategy+for+Sustainable+Agriculture+Development&ots=LUJOOM6X8M&sig=QDhC8DWiYjfRh5RpKFpuCEZerFQ.

- M. C. Ordoñez, L. Galicia, A. Figueroa, I. Bravo, and M. Peña, “Effects of peasant and indigenous soil management practices on the biogeochemical properties and carbon storage services of Andean soils of Colombia,” Eur. J. Soil Biol., vol. 71, pp. 28–36, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Kopittke et al., “Ensuring planetary survival: the centrality of organic carbon in balancing the multifunctional nature of soils,” Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 52, no. 23, pp. 4308–4324, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Ordóñez Díaz, I. Bravo Realpe, and A. Figueroa Casas, “Flujo de Carbono Orgánico Total (COT) en una cuenca andina: caso subcuenca Río Las Piedras,” Rev. Ing. Univ. Medellín, vol. 13, no. 24, pp. 29–42, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Celentano et al., “Restauración ecológica de bosques tropicales en Costa Rica: Efecto de varios modelos en la producción, acumulación y descomposición de hojarasca,” Rev. Biol. Trop., vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 1323–1336, 2011. [CrossRef]

- F. Moreno, S. F. Oberbauer, and W. Lara, “Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Under Different Tropical Cover Types in Colombia,” pp. 367–383, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Montoya Salazar, J. C. Menjivar Flores, and I. D. S. Bravo Realpe, “Fraccionamiento y cuantificación de la materia orgánica en andisoles bajo diferentes sistemas de producción,” Acta Agron., vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 333–343, 2013.

- G. R. Blake and K. H. Hartge, “Bulk Density,” Methods Soil Anal. Part 1 Phys. Mineral. Methods, pp. 363–375, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Prakash, A. Sridharan, and S. Sudheendra, “Hygroscopic moisture content: Determination and correlations,” Environ. Geotech., vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 293–301, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Caicedo-Rosero, F. de J. Méndez-Ávila, E. Gutiérrez-Zeferino, and J. de J. A. Flores-Cuautle, “Medición de humedad en suelos, revisión de métodos y características,” Pädi Boletín Científico Ciencias Básicas e Ing. del ICBI, vol. 9, no. 17, pp. 1–8, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Alavi-Murillo, J. Diels, J. Gilles, and P. Willems, “Soil organic carbon in Andean high-mountain ecosystems: importance, challenges, and opportunities for carbon sequestration,” Reg. Environ. Chang., vol. 22, no. 4, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Beillouin et al., “A global overview of studies about land management, land-use change, and climate change effects on soil organic carbon,” Glob. Chang. Biol., vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 1690–1702, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Don, J. Schumacher, and A. Freibauer, “Impact of tropical land-use change on soil organic carbon stocks - a meta-analysis,” Glob. Chang. Biol., vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 1658–1670, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wei, L. F. Yu, J. C. Zhang, Y. C. Yu, and D. L. Deangelis, “Relationship Between Vegetation Restoration and Soil Microbial Characteristics in Degraded Karst Regions: A Case Study,” Pedosphere, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 132–138, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Giweta, “Role of litter production and its decomposition, and factors affecting the processes in a tropical forest ecosystem: A review,” J. Ecol. Environ., vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Xu, N. He, and G. Yu, “Methods of evaluating soil bulk density: Impact on estimating large scale soil organic carbon storage,” Catena, vol. 144, pp. 94–101, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. Heckman et al., “Beyond bulk: Density fractions explain heterogeneity in global soil carbon abundance and persistence,” Glob. Chang. Biol., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 1178–1196, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Lal, “Soil organic matter and water retention,” Agron. J., vol. 112, no. 5, pp. 3265–3277, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. A. M. Valencia, F. M. Hurtado, and D. F. J. Jaramillo, “Impact of land use on organic carbon sequestration in a natural area of Medellín, Colombia,” Acta Agron., vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 39–46, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Fujisaki, L. Chapuis-Lardy, A. Albrecht, T. Razafimbelo, J. L. Chotte, and T. Chevallier, “Data synthesis of carbon distribution in particle size fractions of tropical soils: Implications for soil carbon storage potential in croplands,” Geoderma, vol. 313, no. November 2017, pp. 41–51, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Bogati and M. Walczak, “The Impact of Drought Stress on Soil Microbial Community, Enzyme Activities and Plants,” Agronomy, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–26, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Quinto-Mosquer, G. Ayala-Viva, and H. Gutiérrez, “Nutrient content, acidity, and soil texture in areas degraded by mining in the biogeographic Chocó,” Rev. la Acad. Colomb. Ciencias Exactas, Fis. y Nat., vol. 46, no. 179, pp. 514–528, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Khalajabadi, R. Darío, and Z. Hernández, “Propiedades Relacionadas Con La Adsorción De Cationes Intercambiables En Algunos Suelos De La Zona Cafetera De Colombia 1,” Cenicafé, vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 79–89, 2012.

- Håkansson and J. Lipiec, “A review of the usefulness of relative bulk density values in studies of soil structure and compaction,” Soil Tillage Res., vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 71–85, 2000. [CrossRef]

- C. Wang et al., “Ecological restoration treatments enhanced plant and soil microbial diversity in the degraded alpine steppe in Northern Tibet,” L. Degrad. Dev., vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 723–737, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. X. Lu et al., “Effects of different vegetation restoration on soil nutrients, enzyme activities, and microbial communities in degraded karst landscapes in southwest China,” For. Ecol. Manage., vol. 508, no. January, p. 120002, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Sahle, O. Saito, C. Fürst, and K. Yeshitela, “Quantification and mapping of the supply of and demand for carbon storage and sequestration service in woody biomass and soil to mitigate climate change in the socio-ecological environment,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 624, pp. 342–354, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Demie, M. Negash, Z. Asrat, and L. Bohdan, “Carbon stocks vary in reference to the models used, socioecological factors and agroforestry practices in Central Ethiopia,” Agrofor. Syst., vol. 98, no. 6, pp. 1905–1925, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Amin, M. S. Hossain, L. Lobry de Bruyn, and B. Wilson, “A systematic review of soil carbon management in Australia and the need for a social-ecological systems framework,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 719, p. 135182, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. S. El-Beltagi et al., “Mulching as a Sustainable Water and Soil Saving Practice in Agriculture: A Review,” Agronomy, vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 1–31, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Walia, K. Kaur, and T. Kaur, “Techniques and Practices of Soil Moisture Conservation (Use of Mulches, Kinds, Effectiveness, and Economics),” Rainfed Agric. Watershed Manag., pp. 49–56, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Jagadesh et al., “Revealing the hidden world of soil microbes: Metagenomic insights into plant, bacteria, and fungi interactions for sustainable agriculture and ecosystem restoration,” Microbiol. Res., vol. 285, no. May, p. 127764, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Coefficients: | Intercept | BD | SOC | SBR | CL | C_MU |

| Bajo | 32.16 | 18.38 | -0.49 | 0.81 | 24.14 | -34.16 |

| Medio | -32.05 | -18.61 | -1.23 | 0.93 | -19.93 | 20.52 |

| Std. Errors: | Intercept | BD | SOC | SBR | CL | C_MU |

| Bajo | 331.36 | 311.13 | 6292.85 | 7496.41 | 1131.01 | 548.08 |

| Medio | 299.04 | 245.43 | 6265.70 | 7576.90 | 1017.60 | 1731.31 |

| Residual Deviance: 4.84e-06 | ||||||

| AIC: 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).