Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

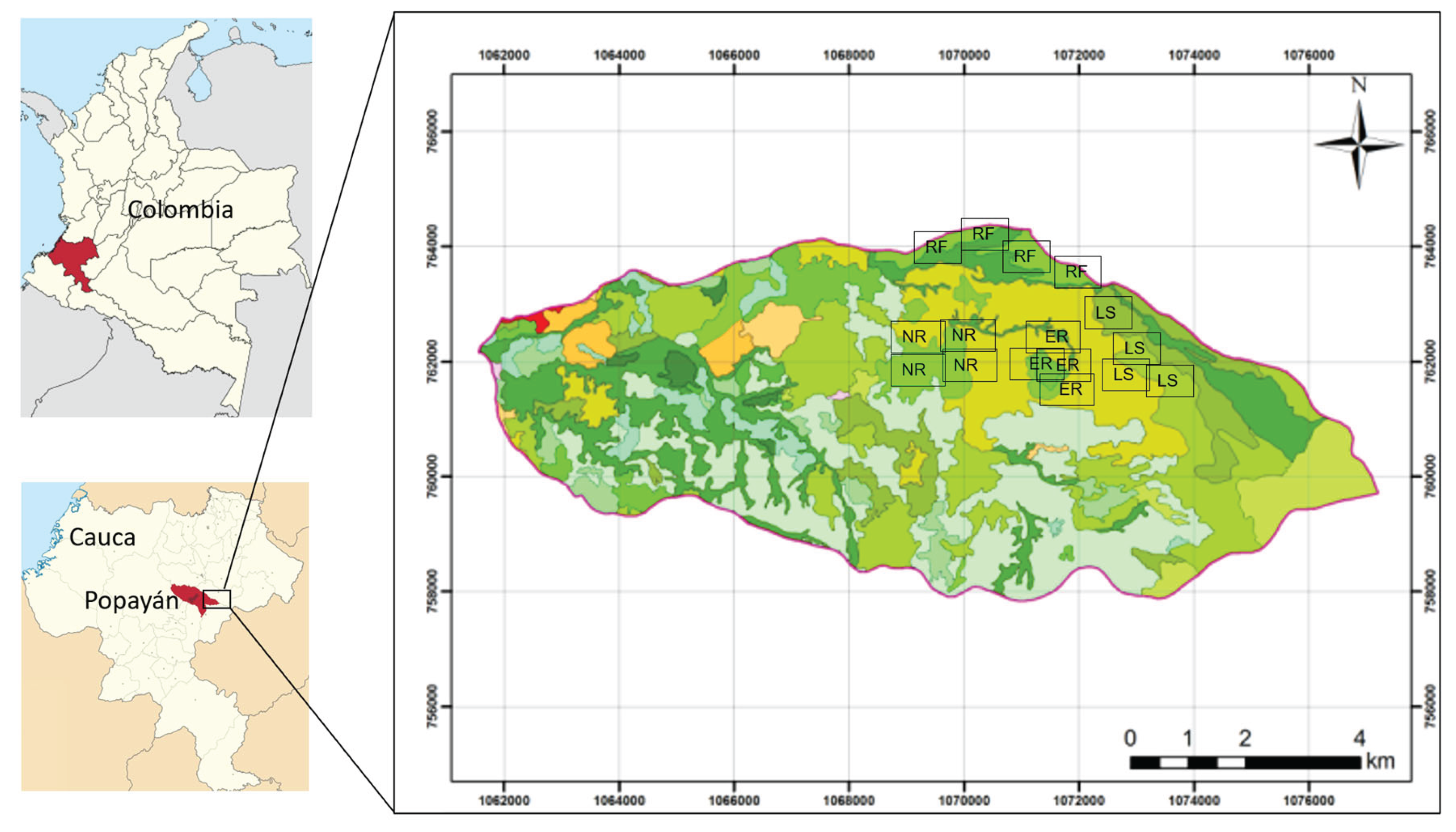

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Soil Physical, Chemical, and Biological Properties

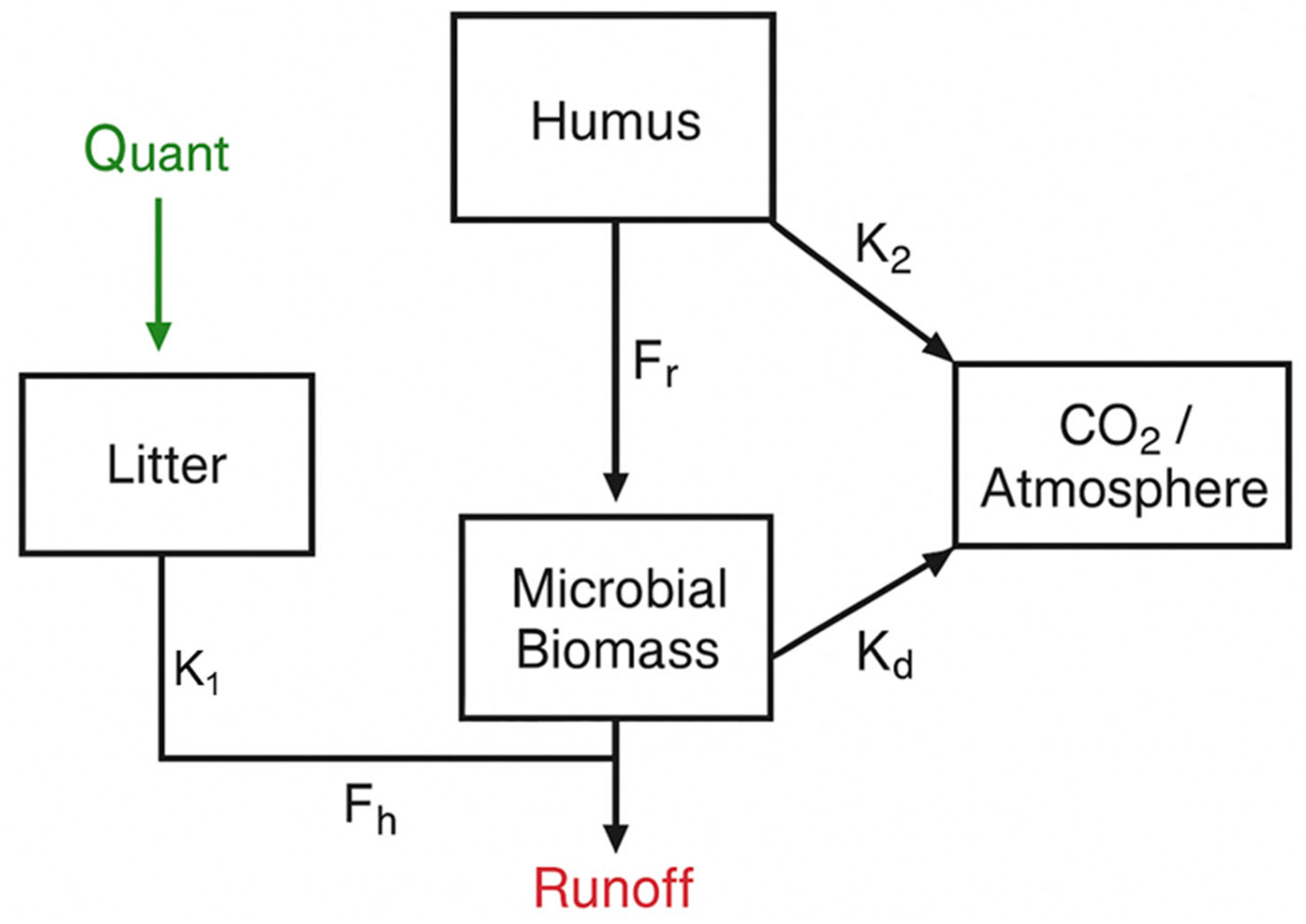

2.3. Model Design

3. Results

3.1. Soil Properties

3.2. Calibration of Model Parameters

3.2. Calibration and Validation of the SOC Model Under Different Land Uses

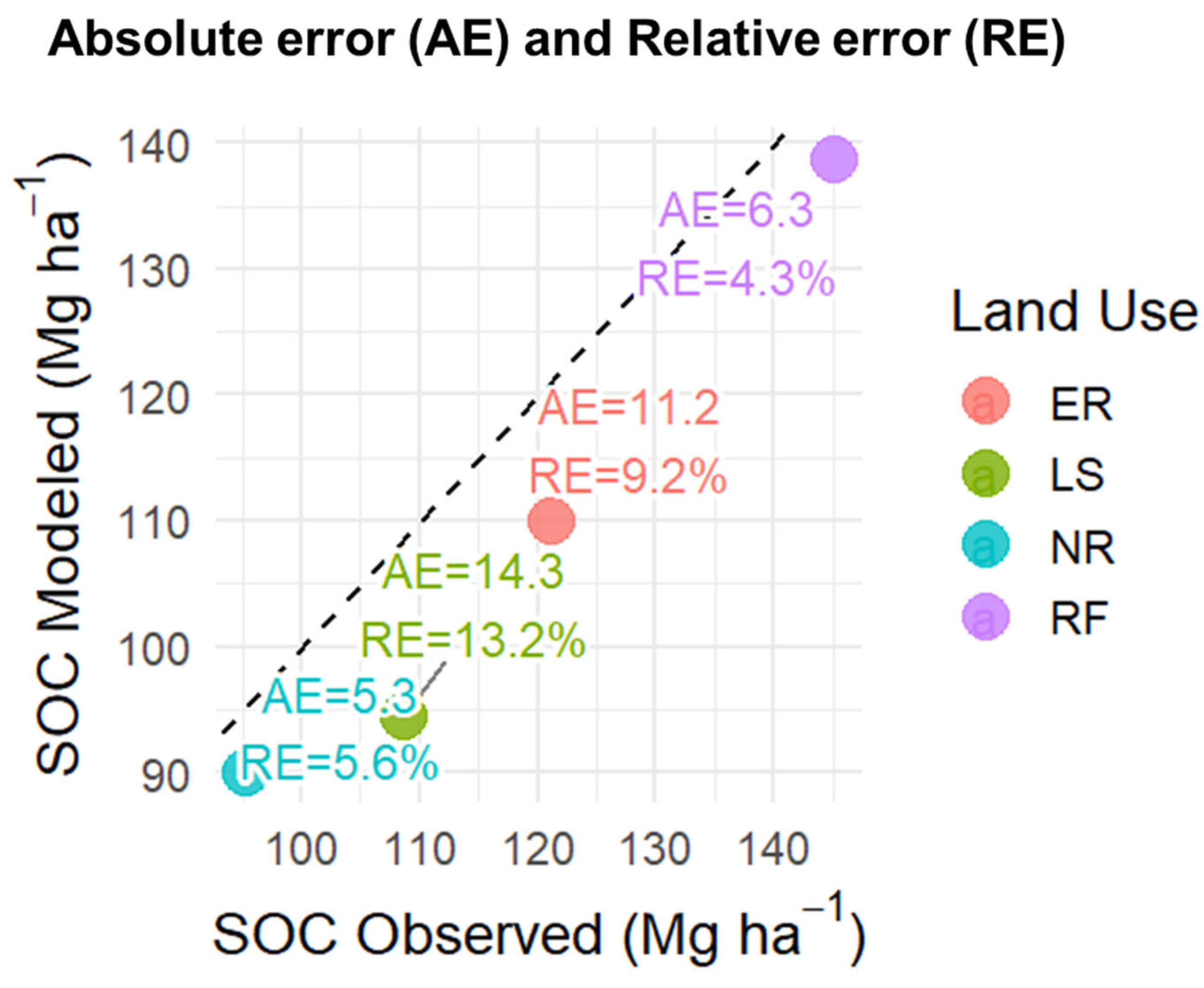

3.3. Model Performance: Observed vs. Modeled SOC

4. Discussion

4.1. Dinámica del Carbono del Suelo Según el Uso del Suelo

4.2. Implications for Soil Carbon Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Don, A.; Seidel, F.; Leifeld, J.; Kätterer, T.; Martin, M.; Pellerin, S.; Emde, D.; Seitz, D.; Chenu, C. Carbon Sequestration in Soils and Climate Change Mitigation—Definitions and Pitfalls. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2024, 30. [CrossRef]

- Lugato, E.; Leip, A.; Jones, A. Mitigation Potential of Soil Carbon Management Overestimated by Neglecting N2O Emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 219–223. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Monger, C.; Nave, L.; Smith, P. The Role of Soil in Regulation of Climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376. [CrossRef]

- Pérez Fagua, C.; Landínez Torres, Á.Y.; Silva Parra, A. Carbono Orgánico y Su Dinámica En Suelos Tropicales: Una Revisión. Cult. Científica 2023, 1, 1–22.

- Lis-Gutiérrez, M.; Rubiano-Sanabria, Y.; Usuga, J.C.L. Soils and Land Use in the Study of Soil Organic Carbon in Colombian Highlands Catena. Acta Univ. Carolinae, Geogr. 2019, 54, 15–23. [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Bravo, C.; Torres, A.; Tipán-Torres, C.; Vargas, J.C.; Herrera-Feijoo, R.J.; Heredia-R, M.; Barba, C.; García, A. Carbon Stock Assessment in Silvopastoral Systems along an Elevational Gradient: A Study from Cattle Producers in the Sumaco Biosphere Reserve, Ecuadorian Amazon. Sustain. 2023, 15, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Veldkamp, E.; Schmidt, M.; Markwitz, C.; Beule, L.; Beuschel, R.; Biertümpfel, A.; Bischel, X.; Duan, X.; Gerjets, R.; Göbel, L.; et al. Multifunctionality of Temperate Alley-Cropping Agroforestry Outperforms Open Cropland and Grassland. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Mireles, M.; Paz-Pellat, F.; Hidalgo-Moreno, C.; Etchevers-Barra, J.D. Soil Organic Carbon Depth Distribution Patterns in Different Land Uses and Management. Terra Latinoam. 2022, 40, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Challenges and Opportunities in Soil Organic Matter Research. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 60, 158–169. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.E.; Paustian, K. Current Developments in Soil Organic Matter Modeling and the Expansion of Model Applications: A Review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10. [CrossRef]

- Wieder, W.R.; Grandy, A.S.; Kallenbach, C.M.; Bonan, G.B. Integrating Microbial Physiology and Physio-Chemical Principles in Soils with the MIcrobial-MIneral Carbon Stabilization (MIMICS) Model. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 3899–3917. [CrossRef]

- Carbajal, M.; Ramírez, D.A.; Turin, C.; Schaeffer, S.M.; Konkel, J.; Ninanya, J.; Rinza, J.; De Mendiburu, F.; Zorogastua, P.; Villaorduña, L.; et al. From Rangelands to Cropland, Land-Use Change and Its Impact on Soil Organic Carbon Variables in a Peruvian Andean Highlands: A Machine Learning Modeling Approach. Ecosystems 2024, 27, 899–917. [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, M.C.; Olaya, J.F.C.; Galicia, L.; Figueroa, A. Soil Carbon Dynamics under Pastures in Andean Socio-Ecosystems of Colombia. Agronomy 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Huang, Y.; Hungate, B.A.; Manzoni, S.; Frey, S.D.; Schmidt, M.W.I.; Reichstein, M.; Carvalhais, N.; Ciais, P.; Jiang, L.; et al. Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency Promotes Global Soil Carbon Storage. Nature 2023, 618, 981–985. [CrossRef]

- Afzal, T.; Wakeel, A.; Cheema, S.A.; Iqbal, J.; Sanaullah, M. Influence of Quality and Quantity of Crop Residues on Organic Carbon Dynamics and Microbial Activity in Soil. Soil Environ. 2024, 43, 53–64. [CrossRef]

- Alavi-Murillo, G.; Diels, J.; Gilles, J.; Willems, P. Soil Organic Carbon in Andean High-Mountain Ecosystems: Importance, Challenges, and Opportunities for Carbon Sequestration. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tariq, A.; Zeng, F.; Sardans, J.; Al-Bakre, D.A.; Peñuelas, J. Long-Term Anthropogenic Disturbances Exacerbate Soil Organic Carbon Loss in Hyperarid Desert Ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2025, 31. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R.K.; Walia, A. Advancements in Microbial Biotechnology for Soil Health; 2024; Vol. 50; ISBN 978-981-99-9481-6.

- Van Keulen, H. (Tropical) Soil Organic Matter Modelling: Problems and Prospects. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2001, 61, 33–39. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jansen, B.; Absalah, S.; Kalbitz, K.; Chunga Castro, F.O.; Cammeraat, E.L.H. Soil Organic Carbon Content and Mineralization Controlled by the Composition, Origin and Molecular Diversity of Organic Matter: A Study in Tropical Alpine Grasslands. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 215, 105203. [CrossRef]

- Pérez Fagua, C.; Landínez Torres, Á.Y.; Silva Parra, A. Carbono Orgánico y Su Dinámica En Suelos Tropicales: Una Revisión. Cult. Científica 2023, 1, 1–22.

- Koutika, L.-S.; Cerri, C.C.; Koutika, L.-S.; Bartoli, F.; Andreux, F.; Burtin, G.; Chon6, T.; Philippy, R. Organic Matter Dynamics and Aggregation in Soils under Rain Forest and Pastures of Increasing Age in the Eastern Amazon Basin. Geoderma 1997, 76, 87–112. [CrossRef]

- Visconti-Moreno, E.F.; Valenzuela-Balcázar, I.G. Impact of Soil Use on Aggregate Stability and Its Relationship with Soil Organic Carbon at Two Different Altitudes in the Colombian Andes. Agron. Colomb. 2019, 37, 263–273. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jansen, B.; Absalah, S.; Van Hall, R.L.; Kalbitz, K.; Cammeraat, E.H.E. Lithology-and Climate-Controlled Soil Aggregate-Size Distribution and Organic Carbon Stability in the Peruvian Andes. Soil 2020, 6, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, S.R.; Leinweber, P.; Jurasinski, G.; Eckhardt, K.U.; Glatzel, S. Tillage-Induced Short-Term Soil Organic Matter Turnover and Respiration. Soil 2016, 2, 475–486. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, P.; Guo, Y.; Aso, H.; Huang, Q.; Araki, H.; Nishizawa, T.; Komatsuzaki, M. Long-Term No-Tillage and Rye Cover Crops Affect Soil Biological Indicators on Andosols in a Humid, Subtropical Climate. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13306. [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.T.; Klopatek, J.M.; Malin, R.C.; Klopatek, C.C. Carbon Pools and Fluxes along an Environmental Gradient in Northern Arizona. Biogeochemistry 1998, 43, 43–61.

| Variable | Land use | |||

| ER | LS | NR | RF | |

| ECEC (meq100 g-1 soil) | 4.1 ±0.22 | 5.7±0.5 | 4.38±0.39 | 3.73±0.23 |

| pH | 4.6±0.1 | 5.12±0.15 | 4.93±0.21 | 4.93±0.05 |

| C% | 3.75±0.75 | 3.81±0.84 | 3.41±2.77 | 4.97+0.93 |

| N% | 0.79±0.06 | 1.03±0.08 | 0.87±0.19 | 1.18±0.1 |

| C/N% | 4.75±0.7 | 3.70±0.29 | 3.92±0.21 | 4.21±0.5 |

| SOC (Mg ha-1) | 119.24±5.05 | 102.85±5.55 | 97.3±14.13 | 148.68±6.07 |

| CL (Mg ha−1month−1) | 2.23±0.11 | 1.08±0.19 | 2±0.32 | 4.65±0.52 |

| CMU (Mg ha-1) | 5.6±0.51 | 2.37±0.63 | 3.8±0.38 | 8.1±1.02 |

| BD (g cm−3) | 1.06±0.01 | 0.9±0.02 | 0.95±0.08 | 1±0.01 |

| Sand (%) | 72.5±3 | 73.5±2.52 | 73.5±2.52 | 73.5±2.52 |

| Silt (%) | 23.5±3 | 21±2 | 22.5±2.52 | 21.5±1.91 |

| Clay (%) | 4± 0.01 | 5.5±0.99 | 4±0.01 | 5±1.13 |

| HSM (%) | 11.32±0.56 | 10.08±0.49 | 10.52±0.55 | 13.49±0.4 |

| SM (%) | 65.65±0.61 | 62.75±0.72 | 62.81±0.25 | 64.96±0.8 |

| MicC. (μg C g−1) | 199.19±1.17 | 108.18±2.47 | 191.51±0.68 | 198.18±0.87 |

| SMicR CO2 (eq C) (kg ha−1 month−1) | 145.94±4.38 | 112.65±8.58 | 121.11±2.31 | 108.01±2.41 |

| Range Values | RF | ER | NR | LS | |

| K1 (month⁻¹) | 0.001–0.9 | 0.308 | 0.190 | 0.154 | 0.001 |

| K2 (month⁻¹) | 2.5e-6–0.001 | 1,00E-04 | 8,00E-05 | 1,00E-04 | 0.01 |

| Fh | 0.2–0.5 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.249 |

| Fr | 0.2–0.8 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.787 | 0.20 |

| Kd (month⁻¹) | 0.01–1.2 | 0.139 | 0.632 | 0.555 | 0.010 |

| Land use | ||||||||||||

| RF | MAE | ER | MAE | NR | MAE | LS | MAE | |||||

| Observed | Modeled | Observed | Modeled | Observed | Modeled | Observed | Modeled | |||||

| SOC (Mg ha-1) | 148.69 | 148.17 | 0.1 | 119.24 | 108.24 | 0.01 | 97.29 | 98.78 | 0.3 | 102.85 | 98.6 | 0.03 |

| MB (Mg ha-1) | 1.99 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 2.12 | 1.78 | 1.34 | 0.98 | 0.77 | 0.31 | 0.98 | 0.67 | 0.31 |

| eqC (Mg ha-1) | 1.42 | 1.39 | 0.03 | 1.11 | 1.09 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 1.08 | 0.1 | 0.41 | 1.08 | 0.67 |

| Humus pool (Mg ha-1) | 107.01 | 82.2 | 77.87 | 66.99 | ||||||||

| Litter pool (Mg ha-1) | 30.94 | 25.34 | 21.34 | 21.61 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).