Submitted:

01 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

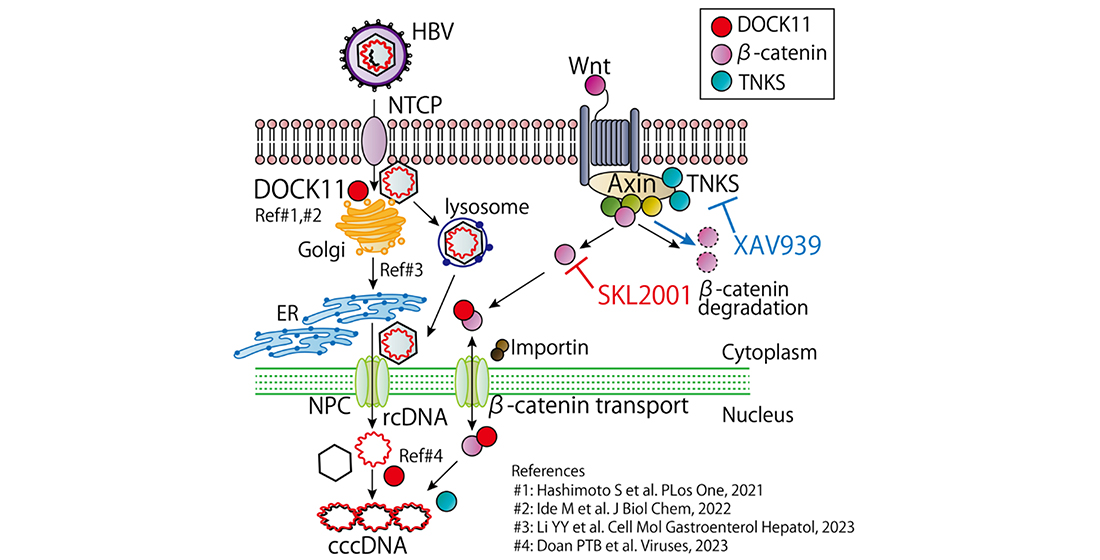

1. Introduction

2. Results

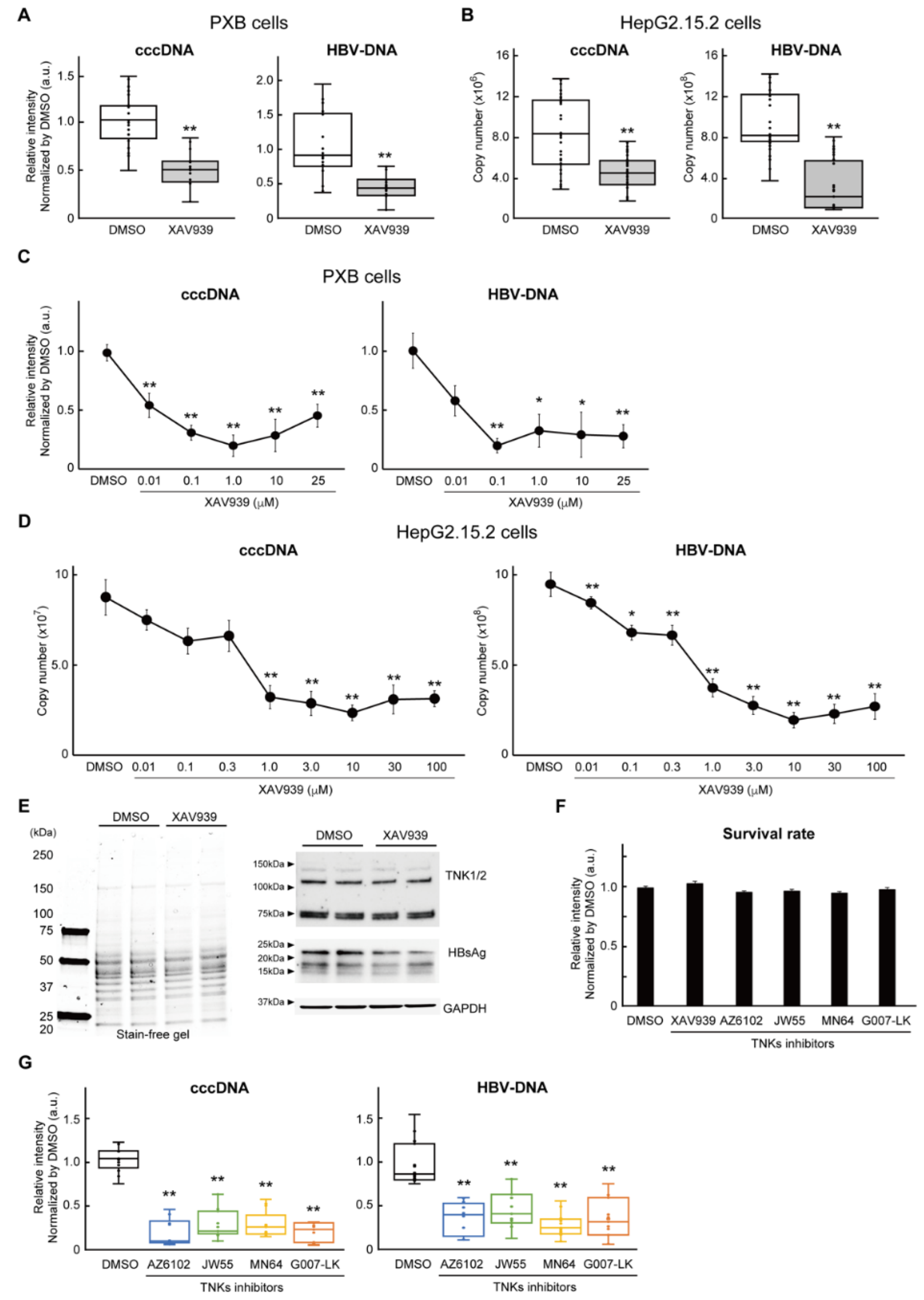

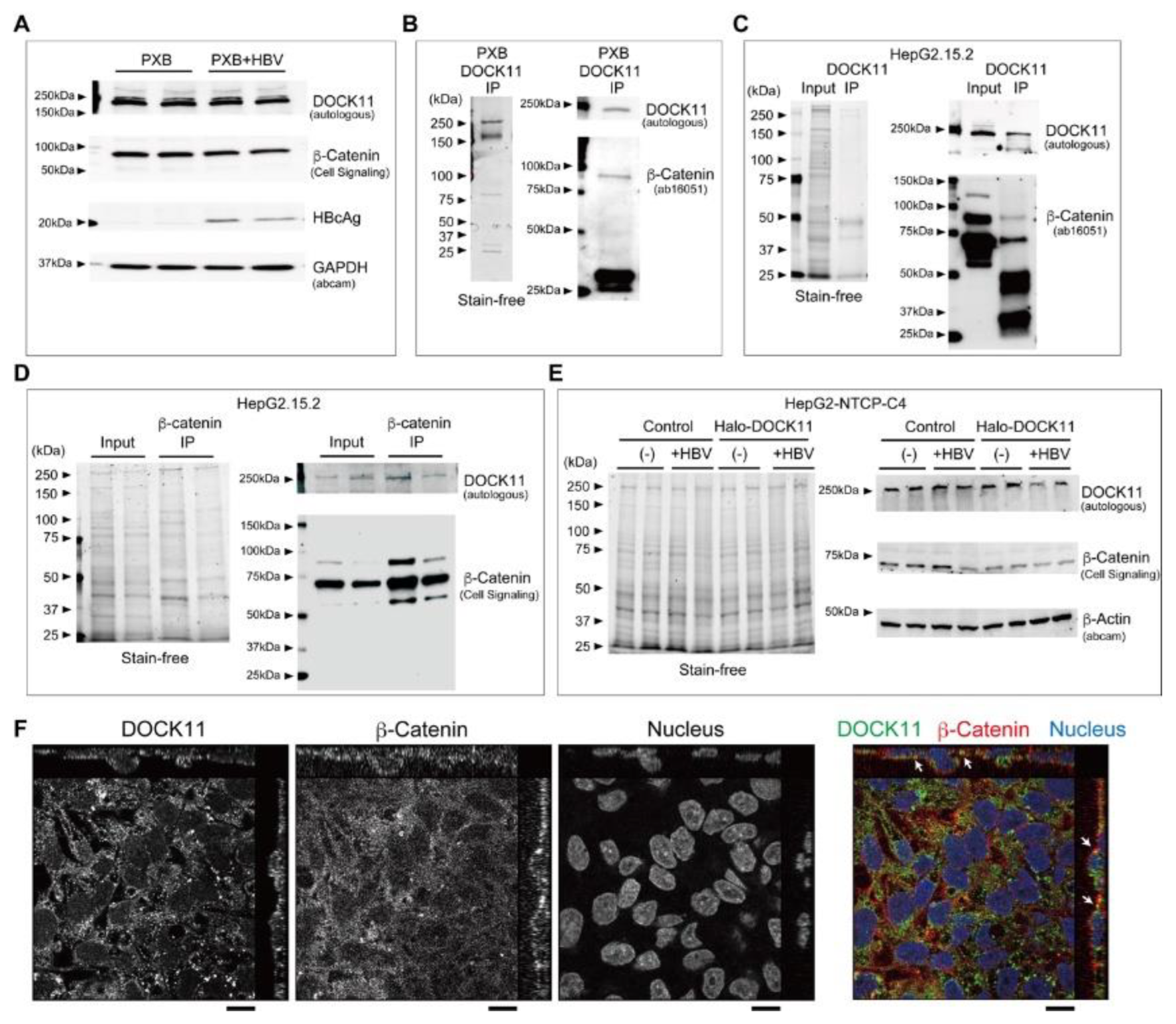

2.1. Inhibition of TNKS eliminated HBV cccDNA

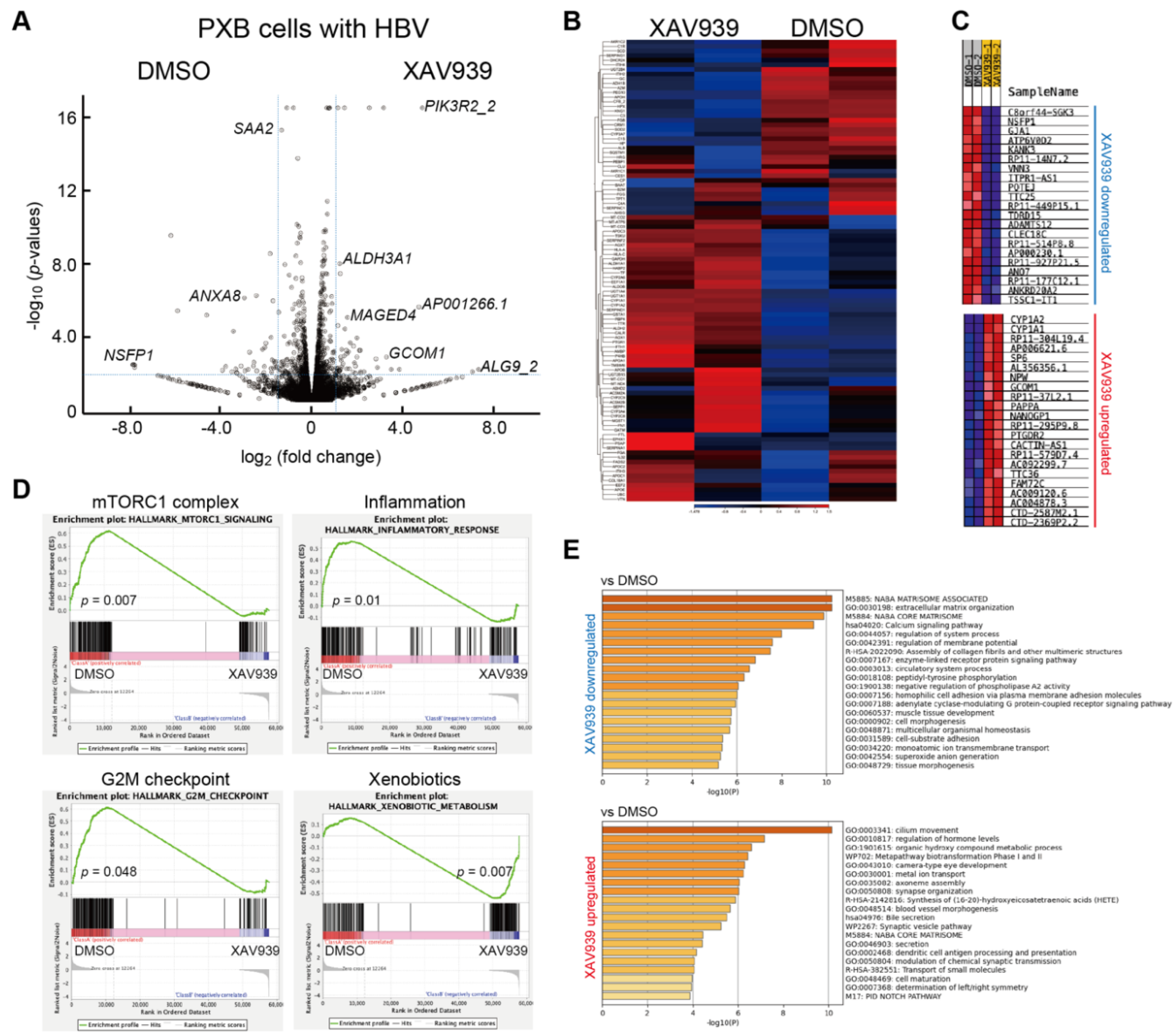

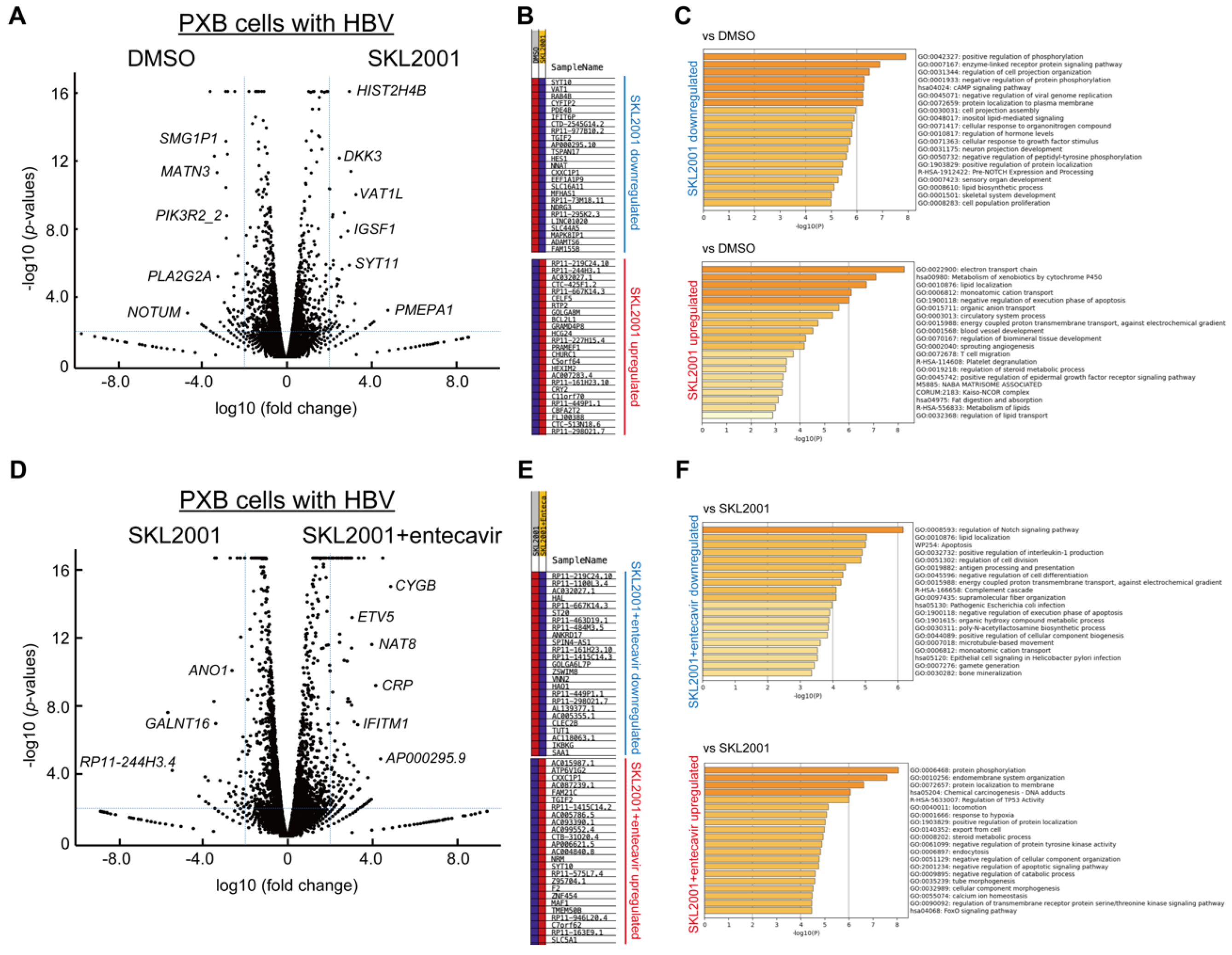

2.2. Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with TNKS inhibition

2.3. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates cccDNA and HBV-DNA levels

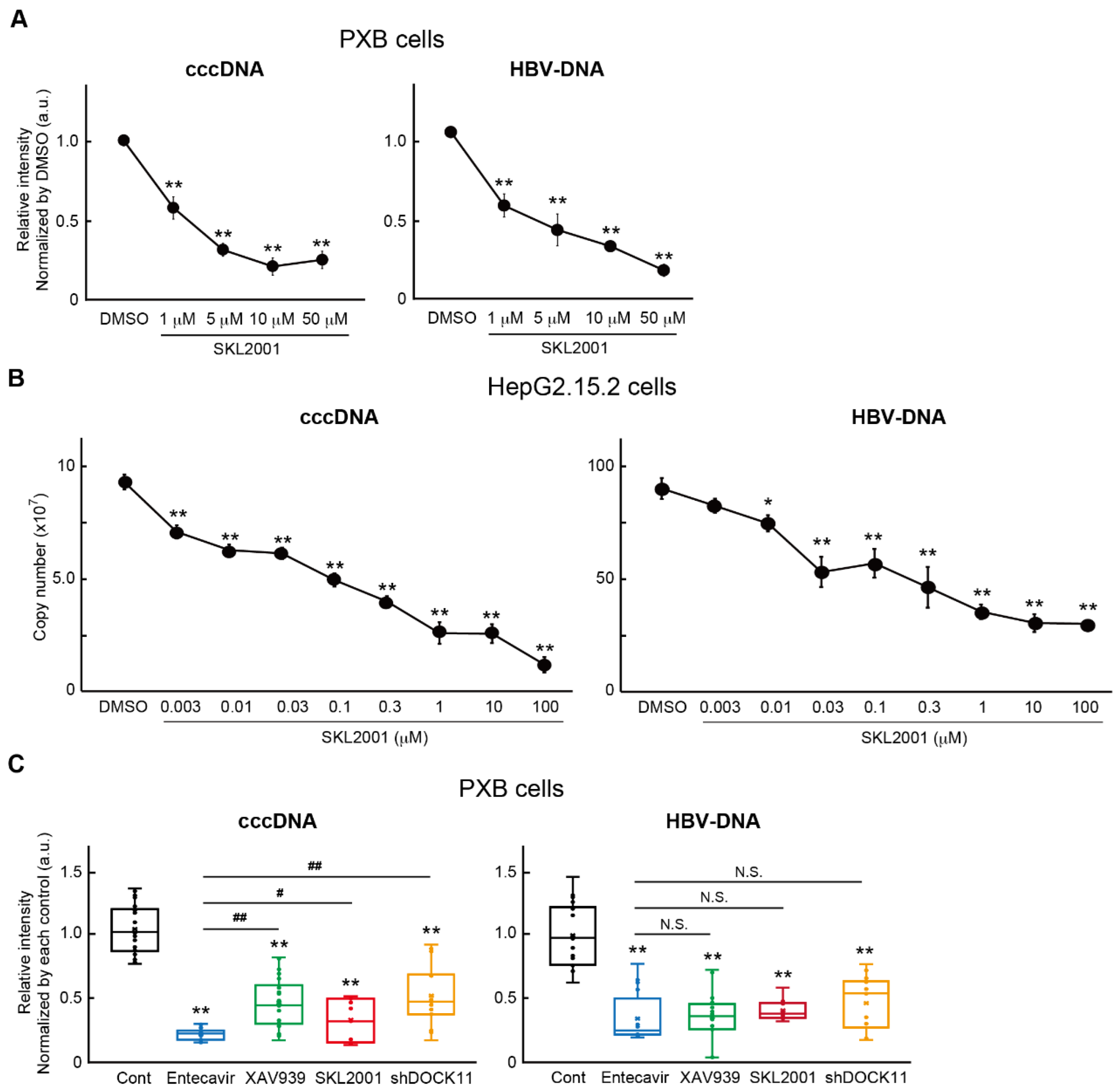

2.4. Wnt/b-catenin agonist SKL2001 strongly suppressed cccDNA and HBV-DNA levels

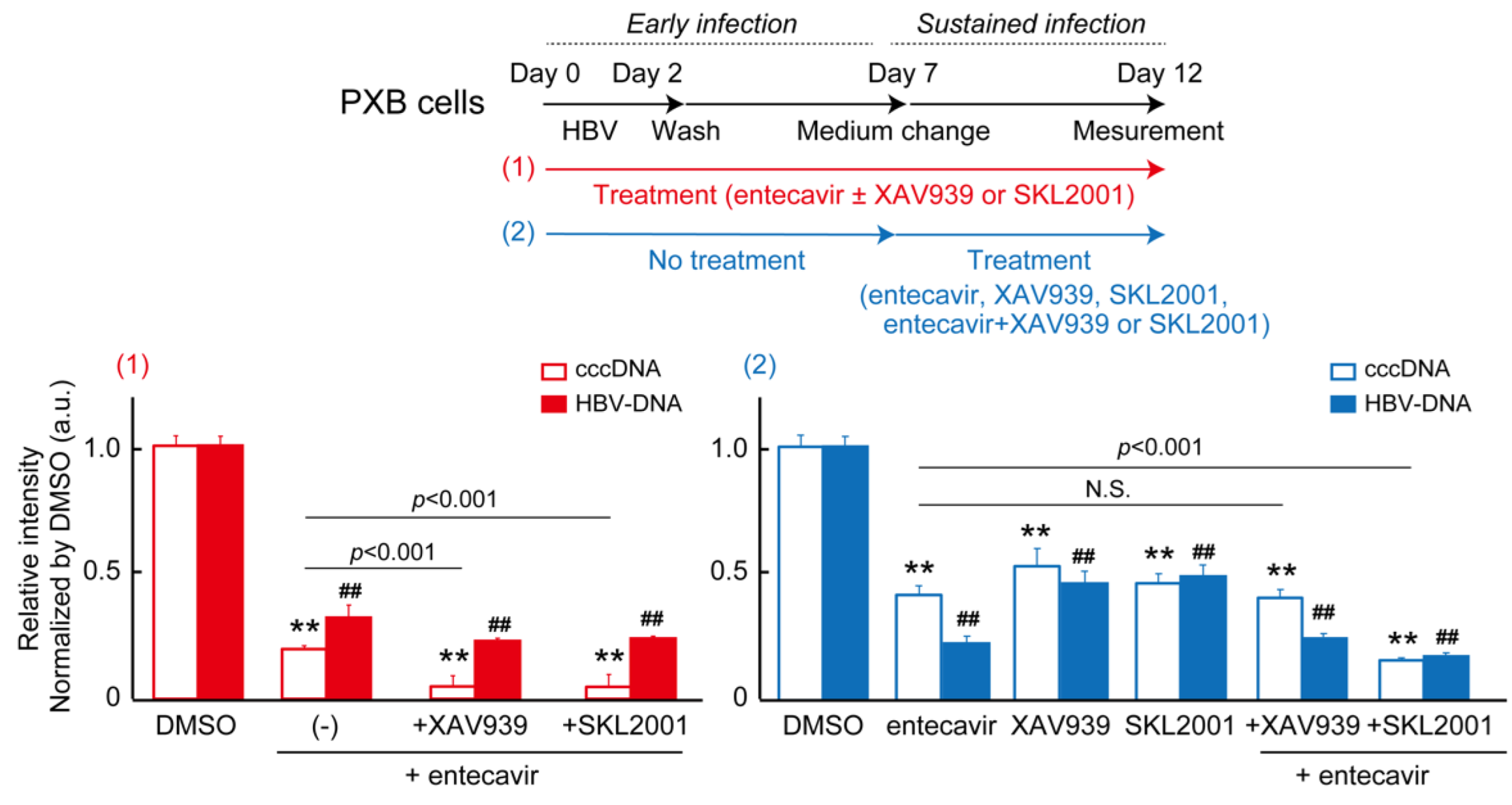

2.5. DEGs of co-treatment effect of Wnt/b-catenin agonist SKL2001 and entecavir

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Cell culture

4.2. Quantification of cccDNA and HVB-DNA

4.3. Western blotting

4.4. Cell proliferation assay

4.5. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

4.6. Short-hairpin RNA (shRNA)

4.7. Immunoprecipitation (IP) Assay

4.8. Immunofluorescence microscopy and fluorescence imaging

4.9. Statistical Analysies

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nassal, M. , HBV cccDNA: viral persistence reservoir and key obstacle for a cure of chronic hepatitis B. Gut 2015, 64, 1972–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Y.; Zhang, B. H.; Theele, D.; Litwin, S.; Toll, E.; Summers, J. , Single-cell analysis of covalently closed circular DNA copy numbers in a hepadnavirus-infected liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 12372–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, P. T. B.; Nio, K.; Shimakami, T.; Kuroki, K.; Li, Y. Y.; Sugimoto, S.; Takayama, H.; Okada, H.; Kaneko, S.; Honda, M.; Yamashita, T. Super-Resolution Microscopy Analysis of Hepatitis B Viral cccDNA and Host Factors. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y. Y.; Kuroki, K.; Shimakami, T.; Murai, K.; Kawaguchi, K.; Shirasaki, T.; Nio, K.; Sugimoto, S.; Nishikawa, T.; Okada, H.; Orita, N.; Takayama, H.; Wang, Y.; Thi Bich, P. D.; Ishida, A.; Iwabuchi, S.; Hashimoto, S.; Shimaoka, T.; Tabata, N.; Watanabe-Takahashi, M.; Nishikawa, K.; Yanagawa, H.; Seiki, M.; Matsushima, K.; Yamashita, T.; Kaneko, S.; Honda, M. , Hepatitis B Virus Utilizes a Retrograde Trafficking Route via the Trans-Golgi Network to Avoid Lysosomal Degradation. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 15, 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, M.; Tabata, N.; Yonemura, Y.; Shirasaki, T.; Murai, K.; Wang, Y.; Ishida, A.; Okada, H.; Honda, M.; Kaneko, S.; Doi, N.; Ito, S.; Yanagawa, H. , Guanine nucleotide exchange factor DOCK11-binding peptide fused with a single chain antibody inhibits hepatitis B virus infection and replication. J Biol Chem 2022, 298, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, S.; Shirasaki, T.; Yamashita, T.; Iwabuchi, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Takamura, Y.; Ukita, Y.; Deshimaru, S.; Okayama, T.; Ikeo, K.; Kuroki, K.; Kawaguchi, K.; Mizukoshi, E.; Matsushima, K.; Honda, M.; Kaneko, S. , DOCK11 and DENND2A play pivotal roles in the maintenance of hepatitis B virus in host cells. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0246313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagawa, H. , Exploration of the origin and evolution of globular proteins by mRNA display. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 3841–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, B. A.; Kraus, W. L. , New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly(ADP-ribose) and PARPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012, 13, 411–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Mickanin, C.; Feng, Y.; Charlat, O.; Michaud, G. A.; Schirle, M.; Shi, X.; Hild, M.; Bauer, A.; Myer, V. E.; Finan, P. M.; Porter, J. A.; Huang, S. M.; Cong, F. , RNF146 is a poly(ADP-ribose)-directed E3 ligase that regulates axin degradation and Wnt signalling. Nat Cell Biol 2011, 13, 623–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Tacchelly-Benites, O.; Wang, Z.; Randall, M. P.; Tian, A.; Benchabane, H.; Freemantle, S.; Pikielny, C.; Tolwinski, N. S.; Lee, E.; Ahmed, Y. , Wnt pathway activation by ADP-ribosylation. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimelman, D.; Xu, W. , beta-catenin destruction complex: insights and questions from a structural perspective. Oncogene 2006, 25, 7482–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Rubin, J. S.; Kimmel, A. R. , Rapid, Wnt-induced changes in GSK3beta associations that regulate beta-catenin stabilization are mediated by Galpha proteins. Curr Biol 2005, 15, 1989–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnow, G.; McLachlan, A. , Selective effect of beta-catenin on nuclear receptor-dependent hepatitis B virus transcription and replication. Virology 2022, 571, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnow, G.; McLachlan, A. , beta-Catenin Signaling Regulates the In Vivo Distribution of Hepatitis B Virus Biosynthesis across the Liver Lobule. J Virol 2021, 95, e0078021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Wang, T. Z.; Kong, D.; Zhang, L.; Meng, H. X.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Y. Q.; Yu, Z. X.; Jin, X. M. , Hepatoma cell line HepG2.2.15 demonstrates distinct biological features compared with parental HepG2. World J Gastroenterol 2011, 17, 1152–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, C.; Tateno, C.; Aratani, A.; Ohnishi, C.; Katayama, S.; Kohashi, T.; Hino, H.; Marusawa, H.; Asahara, T.; Yoshizato, K. , Growth and differentiation of colony-forming human hepatocytes in vitro. J Hepatol 2006, 44, 749–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Neri, S.; Zhen, Y.; Fong, L. W. R.; Qiao, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Stephan, C.; Deng, W.; Ye, R.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, S.; Yu, Y.; Hung, M. C.; Chen, J.; Lin, S. H. , Tankyrase disrupts metabolic homeostasis and promotes tumorigenesis by inhibiting LKB1-AMPK signalling. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narwal, M.; Koivunen, J.; Haikarainen, T.; Obaji, E.; Legala, O. E.; Venkannagari, H.; Joensuu, P.; Pihlajaniemi, T.; Lehtio, L. , Discovery of tankyrase inhibiting flavones with increased potency and isoenzyme selectivity. J Med Chem 2013, 56, 7880–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norum, J. H.; Skarpen, E.; Brech, A.; Kuiper, R.; Waaler, J.; Krauss, S.; Sorlie, T. , The tankyrase inhibitor G007-LK inhibits small intestine LGR5(+) stem cell proliferation without altering tissue morphology. Biol Res 2018, 51, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsell, A. G.; Ekblad, T.; Karlberg, T.; Low, M.; Pinto, A. F.; Tresaugues, L.; Moche, M.; Cohen, M. S.; Schuler, H. , Structural Basis for Potency and Promiscuity in Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase (PARP) and Tankyrase Inhibitors. J Med Chem 2017, 60, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waaler, J.; Machon, O.; Tumova, L.; Dinh, H.; Korinek, V.; Wilson, S. R.; Paulsen, J. E.; Pedersen, N. M.; Eide, T. J.; Machonova, O.; Gradl, D.; Voronkov, A.; von Kries, J. P.; Krauss, S. , A novel tankyrase inhibitor decreases canonical Wnt signaling in colon carcinoma cells and reduces tumor growth in conditional APC mutant mice. Cancer Res 2012, 72, 2822–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dhfyan, A.; Alhoshani, A.; Korashy, H. M. , Aryl hydrocarbon receptor/cytochrome P450 1A1 pathway mediates breast cancer stem cells expansion through PTEN inhibition and beta-Catenin and Akt activation. Mol Cancer 2017, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A. H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S. K. , Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. M.; Mishina, Y. M.; Liu, S.; Cheung, A.; Stegmeier, F.; Michaud, G. A.; Charlat, O.; Wiellette, E.; Zhang, Y.; Wiessner, S.; Hild, M.; Shi, X.; Wilson, C. J.; Mickanin, C.; Myer, V.; Fazal, A.; Tomlinson, R.; Serluca, F.; Shao, W.; Cheng, H.; Shultz, M.; Rau, C.; Schirle, M.; Schlegl, J.; Ghidelli, S.; Fawell, S.; Lu, C.; Curtis, D.; Kirschner, M. W.; Lengauer, C.; Finan, P. M.; Tallarico, J. A.; Bouwmeester, T.; Porter, J. A.; Bauer, A.; Cong, F. , Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature 2009, 461, 614–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waaler, J.; Machon, O.; von Kries, J. P.; Wilson, S. R.; Lundenes, E.; Wedlich, D.; Gradl, D.; Paulsen, J. E.; Machonova, O.; Dembinski, J. L.; Dinh, H.; Krauss, S. , Novel synthetic antagonists of canonical Wnt signaling inhibit colorectal cancer cell growth. Cancer Res 2011, 71, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Choi, M. Y.; Yu, J.; Castro, J. E.; Kipps, T. J.; Carson, D. A. , Salinomycin inhibits Wnt signaling and selectively induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 13253–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Mitchell, B.; Kintner, C.; Ding, S.; Schultz, P. G. , A small-molecule agonist of the Wnt signaling pathway. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2005, 44, 1987–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yin, J.; Chen, D.; Nie, F.; Song, X.; Fei, C.; Miao, H.; Jing, C.; Ma, W.; Wang, L.; Xie, S.; Li, C.; Zeng, R.; Pan, W.; Hao, X.; Li, L. , Small-molecule modulation of Wnt signaling via modulating the Axin-LRP5/6 interaction. Nat Chem Biol 2013, 9, 579–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagotto, F.; Gluck, U.; Gumbiner, B. M. , Nuclear localization signal-independent and importin/karyopherin-independent nuclear import of beta-catenin. Curr Biol 1998, 8, 181–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, Y.; Stewart, M. , Nup50/Npap60 function in nuclear protein import complex disassembly and importin recycling. EMBO J 2005, 24, 3681–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, J. C.; Pierson, E. E.; Keifer, D. Z.; Delaleau, M.; Gallucci, L.; Cazenave, C.; Kann, M.; Jarrold, M. F.; Zlotnick, A. , Importin beta Can Bind Hepatitis B Virus Core Protein and Empty Core-Like Particles and Induce Structural Changes. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12, e1005802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderholm, J. F.; Bird, S. L.; Kalab, P.; Sampathkumar, Y.; Hasegawa, K.; Uehara-Bingen, M.; Weis, K.; Heald, R. , Importazole, a small molecule inhibitor of the transport receptor importin-beta. ACS Chem Biol 2011, 6, 700–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwak, J.; Hwang, S. G.; Park, H. S.; Choi, S. R.; Park, S. H.; Kim, H.; Ha, N. C.; Bae, S. J.; Han, J. K.; Kim, D. E.; Cho, J. W.; Oh, S. , Small molecule-based disruption of the Axin/beta-catenin protein complex regulates mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Cell Res 2012, 22, 237–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; Gan, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Lv, L.; Mei, Z. Aquaporin 9 inhibits growth and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 1527–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, W.; Yamamine, N.; Imura, J.; Hattori, Y. , SKL2001 suppresses colon cancer spheroid growth through regulation of the E-cadherin/beta-Catenin complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 493, 1342–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhijun, Z.; Jingkang, H. , MicroRNA-520e suppresses non-small-cell lung cancer cell growth by targeting Zbtb7a-mediated Wnt signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017, 486, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Kawaguchi, K.; Honda, M.; Sakai, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Mizukoshi, E.; Kaneko, S. , Distinct notch signaling expression patterns between nucleoside and nucleotide analogues treatment for hepatitis B virus infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 501, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhou, H.; Xia, X.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, B. , Activated Notch signaling is required for hepatitis B virus X protein to promote proliferation and survival of human hepatic cells. Cancer Lett 2010, 298, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Tang, Z.; Zang, G.; Yu, Y. , Blockage of Notch1 signaling modulates the T-helper (Th)1/Th2 cell balance in chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatol Res 2010, 40, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, G.; Xu, H. , Hepatitis B virus X protein activates Notch signaling by its effects on Notch1 and Notch4 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol 2016, 48, 329–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Kawaguchi, K.; Honda, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Shirasaki, T.; Okada, H.; Orita, N.; Shimakami, T.; Yamashita, T.; Sakai, Y.; Mizukoshi, E.; Murakami, S.; Kaneko, S. , Notch signaling facilitates hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA transcription via cAMP response element-binding protein with E3 ubiquitin ligase-modulation. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, M. Y.; Kim, C. M.; Park, Y. M.; Ryu, W. S. , Hepatitis B virus X protein is essential for the activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in hepatoma cells. Hepatology 2004, 39, 1683–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Olshausen, G.; Quasdorff, M.; Bester, R.; Arzberger, S.; Ko, C.; van de Klundert, M.; Zhang, K.; Odenthal, M.; Ringelhan, M.; Niessen, C. M.; Protzer, U. , Hepatitis B virus promotes beta-catenin-signalling and disassembly of adherens junctions in a Src kinase dependent fashion. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 33947–33960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Nadda, N.; Quadri, A.; Kumar, R.; Paul, S.; Tanwar, P.; Gamanagatti, S.; Dash, N. R.; Saraya, A.; Shalimar, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Nayak, B. Assessments of TP53 and CTNNB1 gene hotspot mutations in circulating tumour DNA of hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Genet 2023, 14, 1235260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Tang, S. , WNT/beta-catenin signaling in the development of liver cancers. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 132, 110851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M. A.; Ijaz, B.; Daud, M.; Tariq, S.; Nadeem, T.; Husnain, T. , Interplay of Wnt beta-catenin pathway and miRNAs in HBV pathogenesis leading to HCC. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2019, 43, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Evert, M.; Calvisi, D. F.; Chen, X. beta-Catenin signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Invest 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Cai, X.; Huang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Liang, L.; Tian, L.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Tang, N. , HBx mutations promote hepatoma cell migration through the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Sci 2016, 107, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. D.; Wang, Y.; Ye, L. H. , Hepatitis B virus X protein accelerates the development of hepatoma. Cancer Biol Med 2014, 11, 182–90. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, M.; Xin, X.; Bi, L. Q.; Zhou, L. T.; Liu, X. H. , Molecular mechanism of hepatitis B virus X protein function in hepatocarcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 10732–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lin, L.; Yoo, S.; Wang, W.; Blank, S.; Fiel, M. I.; Kadri, H.; Luan, W.; Warren, L.; Zhu, J.; Hiotis, S. P. , Impact of non-neoplastic vs intratumoural hepatitis B viral DNA and replication on hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. Br J Cancer 2016, 115, 841–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaddeo, G.; Cao, Q.; Ladeiro, Y.; Imbeaud, S.; Nault, J. C.; Jaoui, D.; Gaston Mathe, Y.; Laurent, C.; Laurent, A.; Bioulac-Sage, P.; Calderaro, J.; Zucman-Rossi, J. , Integration of tumour and viral genomic characterizations in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinomas. Gut 2015, 64, 820–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Li, N.; Zhou, P. C.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, R. R.; Fan, X. G. , Detection of HBV DNA and antigens in HBsAg-positive patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2017, 41, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fiel, M. I.; Luan, W.; Blank, S.; Kadri, H.; Kim, K. W.; Hiotis, S. P. , Impact of intrahepatic hepatitis B DNA and covalently closed circular DNA on survival after hepatectomy in HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2013, 20, 3761–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Yu, J.; Yang, A. , Kinesin family member 23 knockdown inhibits cell proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in esophageal carcinoma by inactivating the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Funct Integr Genomics 2023, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Pan, J.; Liu, H.; Lin, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C. , Daphnetin inhibits the survival of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through regulating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Drug Dev Res 2022, 83, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Gong, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Shu, L.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. , Downregulation of MAL2 inhibits breast cancer progression through regulating beta-catenin/c-Myc axis. Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H. L.; Tang, G. D.; Liang, Z. H.; Qin, M. B.; Wang, X. M.; Chang, R. J.; Qin, H. P. , Role of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway agonist SKL2001 in Caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2019, 97, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. T.; Han, T.; Li, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y. J.; Wang, F. M.; Jing, X.; Du, Z. , Enhanced specificity of real-time PCR for measurement of hepatitis B virus cccDNA using restriction endonuclease and plasmid-safe ATP-dependent DNase and selective primers. J Virol Methods 2010, 169, 181–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, V. K.; Lindgren, C. M.; Eriksson, K. F.; Subramanian, A.; Sihag, S.; Lehar, J.; Puigserver, P.; Carlsson, E.; Ridderstrale, M.; Laurila, E.; Houstis, N.; Daly, M. J.; Patterson, N.; Mesirov, J. P.; Golub, T. R.; Tamayo, P.; Spiegelman, B.; Lander, E. S.; Hirschhorn, J. N.; Altshuler, D.; Groop, L. C. , PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet 2003, 34, 267–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).