Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Search Methodology

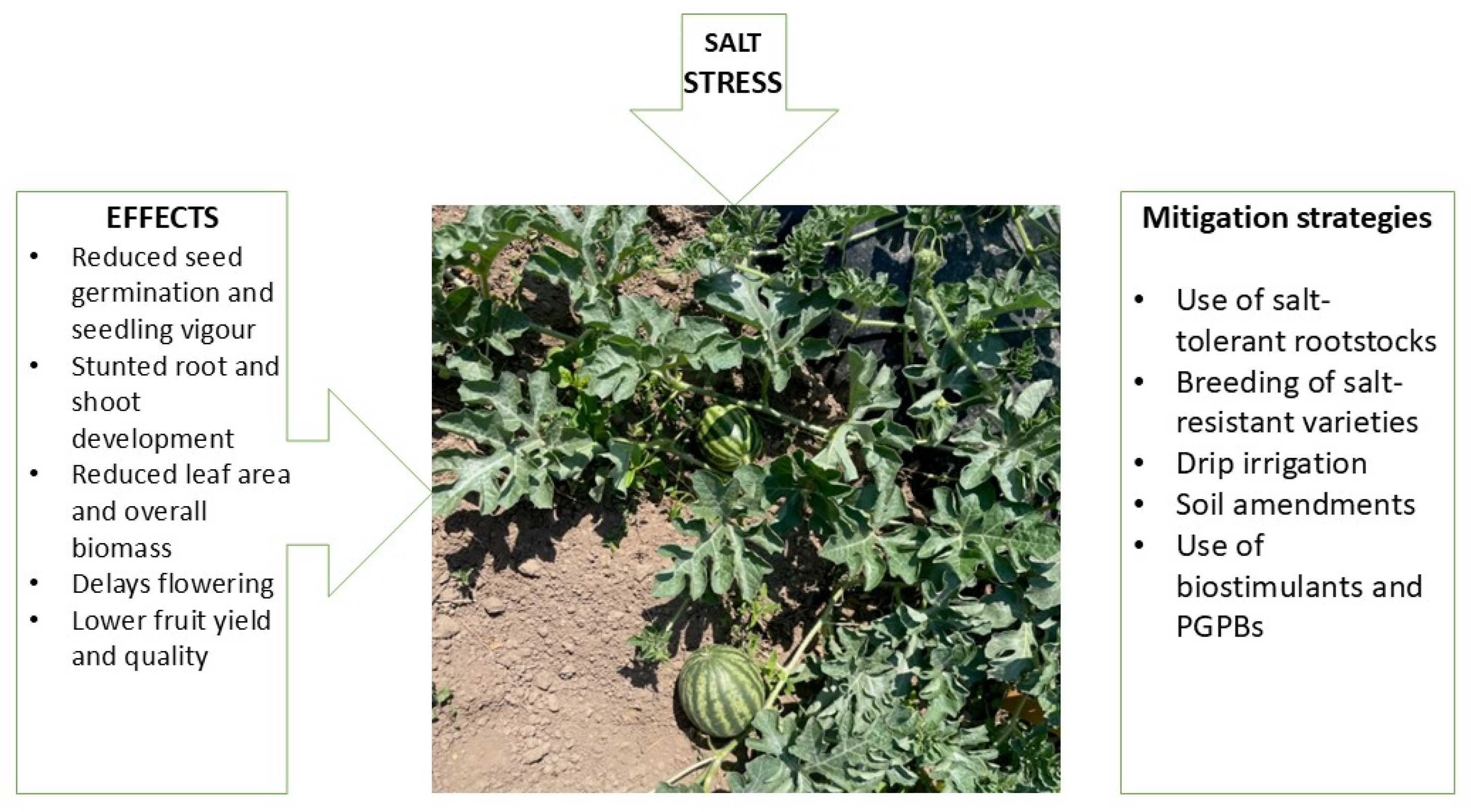

3. Effects of Salt Stress on Watermelon Growth and Development:

3.1. Seed Germination and Early Growth

3.2. Vegetative Growth:

3.3. Reproductive Development:

3.4. Physiological and Biochemical Responses:

3.5. Yield and Quality:

| Growth stages | Studies | References |

|---|---|---|

| Seed germination and Early growth | Cucumber (C. sativus cv. Super Dominus) and watermelon (C. lanatus cv. Crimson Sweet) | [29] |

| Crimson sweet watermelon | [30] | |

| Zucchini (C. moschata; C. maxima; C. moschata) genotypes, | [52] | |

| Vegetative growth | Musk melon (Kalash, Durga), bottle gourd (Crystal long, Nuefield), and squash (Green round, Squash malika) | [32] |

| Watermelon cultivar Crimson Tide and seven gourd genotypes | [33] | |

| 48 watermelon genotypes | [34] | |

| Reproductive development | S. lycopersicum and S. chilense | [36] |

| Maize | [38,39] | |

| Carrot | [40] | |

| Rice | [41,42] | |

| Wheat | [43] | |

| Physiological and Biochemical Responses | Watermelon | [47,48] |

| Spartina alterniflora | [53] | |

| Pisum sativum | [54] | |

| Yield and Quality | Mini-watermelon | [25] |

| Melon (C. melo cv. Huanghe) and watermelon (C. lanatus. convar megulaspemus | [51] |

4. Strategies to Mitigate Salt Stress in Watermelon

4.1. Use of Salt-Tolerant Rootstocks

4.2. Breeding Salt-Resistant Varieties

4.3. Agronomic Practices Such as Drip Irrigation and Soil Amendment

4.4. Application of Biostimulants and Plant Growth Regulators

4.4.1. Biostimulants

4.4.2. Plant Growth-Promoting Microbes and ISR (Induced Systemic Resistance)

| Strategies | Study | Refences |

|---|---|---|

| Use of salt-tolerant rootstocks | Potato | [59] |

| Tomato | [60,61] | |

| Egg plant | [63] | |

| Watermelon | [31,33,64,65,67,96] | |

| Melon | [67,68] | |

| Breeding salt-resistant varieties | Watermelon | [34,48,71,74,75] |

| Agronomic practices | Watermelon | [78,79,97] |

| Zucchini | [79] | |

| Mini-watermelon | [80,81] | |

| Biostimulants | Watermelon | [84,85,86] |

| Plant-Growth-Promoting Microbes | Cucumber | [95] |

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hasanuzzaman M, Oku H, Nahar K, Bhuyan MHMB, Mahmud JA, Baluska F, et al. Nitric oxide-induced salt stress tolerance in plants: ROS metabolism, signaling, and molecular interactions. Plant Biotechnology Reports. 2018;12(2):77-92. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J-K. Abiotic Stress Signaling and Responses in Plants. Cell. 2016;167(2):313-24. [CrossRef]

- Furtak K, Wolińska A. The impact of extreme weather events as a consequence of climate change on the soil moisture and on the quality of the soil environment and agriculture – A review. CATENA. 2023;231:107378. [CrossRef]

- Zandalinas SI, Fritschi FB, Mittler R. Global Warming, Climate Change, and Environmental Pollution: Recipe for a Multifactorial Stress Combination Disaster. Trends in Plant Science. 2021;26(6):588-99. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch CA, Tewksbury JJ, Tigchelaar M, Battisti DS, Merrill SC, Huey RB, et al. Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science. 2018;361(6405):916-9. [CrossRef]

- Chaves MM, Flexas J, Pinheiro C. Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Annals of Botany. 2008;103(4):551-60. [CrossRef]

- Hatfield JL, Prueger JH. Temperature extremes: Effect on plant growth and development. Weather and Climate Extremes. 2015;10:4-10. [CrossRef]

- Glazebrook, J. Contrasting Mechanisms of Defense Against Biotrophic and Necrotrophic Pathogens. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 2005;43(Volume 43, 2005):205-27. [CrossRef]

- Mittler R, Zandalinas SI, Fichman Y, Van Breusegem F. Reactive oxygen species signalling in plant stress responses. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2022;23(10):663-79. [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman M, Nahar K, Alam MM, Roychowdhury R, Fujita M. Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Mechanisms of Heat Stress Tolerance in Plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14(5):9643-84. PubMed PMID. [CrossRef]

- Mazhar S, Pellegrini E, Contin M, Bravo C, Nobili M. Impacts of salinization caused by sea level rise on the biological processes of coastal soils - A review. Frontiers in Environmental Science. 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- Munns R, Tester M. Mechanisms of Salinity Tolerance. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2008;59(Volume 59, 2008):651-81. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu D, Kaundal A. Dynamics of Salt Tolerance: Molecular Perspectives. In: Gosal SS, Wani SH, editors. Biotechnologies of Crop Improvement, Volume 3: Genomic Approaches. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 25-40.

- Butcher K, Wick AF, DeSutter T, Chatterjee A, Harmon J. Soil Salinity: A Threat to Global Food Security. Agronomy Journal. 2016;108(6):2189-200. [CrossRef]

- Yu Z, Duan X, Luo L, Dai S, Ding Z, Xia G. How Plant Hormones Mediate Salt Stress Responses. Trends in Plant Science. 2020;25(11):1117-30. [CrossRef]

- Hayat K, Jochen B, Farooq J, Saiqa M, Sikandar H, Fazal H, et al. Combating soil salinity with combining saline agriculture and phytomanagement with salt-accumulating plants. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 2020;50(11):1085-115. [CrossRef]

- Munns R, Millar AH. Seven plant capacities to adapt to abiotic stress. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2023;74(15):4308-23. [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman M, Bhuyan MHMB, Parvin K, Bhuiyan TF, Anee TI, Nahar K, et al. Regulation of ROS Metabolism in Plants under Environmental Stress: A Review of Recent Experimental Evidence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21(22):8695. PubMed PMID. [CrossRef]

- Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2010;48(12):909-30. [CrossRef]

- Demidchik, V. Mechanisms of oxidative stress in plants: From classical chemistry to cell biology. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2015;109:212-28. [CrossRef]

- Soares C, Carvalho MEA, Azevedo RA, Fidalgo F. Plants facing oxidative challenges—A little help from the antioxidant networks. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2019;161:4-25. [CrossRef]

- Naz A, Butt MS, Sultan MT, Qayyum MM, Niaz RS. Watermelon lycopene and allied health claims. Excli j. 2014;13:650-60. Epub 20140603. PubMed PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4464475. [PubMed]

- Asfaw MD. Review on watermelon production and nutritional value in Ethiopia. J Nutr Sci Res. 2022;7:173.

- Frelier J, Cummins D, Motsenbocker C. Sustainable Gardening for School and Home Gardens: Cantaloupe and Watermelon. 2021.

- da Silva SS, de Lima GS, de Lima VLA, Gheyi HR, Soares LAdA, Oliveira JPM, et al. Production and quality of watermelon fruits under salinity management strategies and nitrogen fertilization. 2020.

- Kotuby-Amacher J, Koenig R, Kitchen B. Salinity and plant tolerance. Electronic Publication AG-SO-03, Utah State University Extension, Logan. 2000.

- Yetisir H, Caliskan ME, Soylu S, Sakar M. Some physiological and growth responses of watermelon [Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. and Nakai] grafted onto Lagenaria siceraria to flooding. Environmental and experimental botany. 2006;58(1-3):1-8.

- Lessa CIN, de Sousa GG, Sousa HC, da Silva FDB, Gomes SP, de Araújo Viana TV. Agricultural ambience and salt stress in production of yellow passion fruit seedlings. Comunicata Scientiae. 2022;13:e3703-e.

- Taheri S, Barzegar T, Zadeh AZ. Effect of salicylic acid pre-treatment on cucumber and watermelon seeds germination under salinity stress. 2016.

- de Albuquerque RIBEIRO A, de Lima SALES MA, ELOI WM, MOREIRA FJC, de Lima SALES FA. Emergência e crescimento inicial da melancia sob estresse salino. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia de Biossistemas. 2012;6(1):30-8.

- Colla G, Roupahel Y, Cardarelli M, Rea E. Effect of salinity on yield, fruit quality, leaf gas exchange, and mineral composition of grafted watermelon plants. HortScience. 2006;41(3):622.

- Naseer MN, Rahman FU, Hussain Z, Khan IA, Aslam MM, Aslam A, et al. Effect of salinity stress on germination, seedling growth, mineral uptake and chlorophyll contents of three Cucurbitaceae species. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 2022;65:e22210213.

- YETİŞİR H, Uygur V. Plant growth and mineral element content of different gourd species and watermelon under salinity stress. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry. 2009;33(1):65-77.

- Coşkun ÖF, Toprak S, Mavi K. Genetic Diversity and Association Mapping for Salinity Tolerance in Watermelon (Citrullus Lanatus L.). Journal of Crop Health. 2025;77(2):73.

- Sakata Y, Ohara T, Sugiyama M, editors. The history and present state of the grafting of cucurbitaceous vegetables in Japan. III International Symposium on Cucurbits 731; 2005.

- Bigot S, Pongrac P, Šala M, van Elteren JT, Martínez J-P, Lutts S, et al. The halophyte species Solanum chilense Dun. maintains its reproduction despite sodium accumulation in its floral organs. Plants. 2022;11(5):672.

- Reddy P, Goss JA. Effect of salinity on pollen I. Pollen viability as altered by increasing osmotic pressure with NaCl, MgCl2, and CaCl2. American Journal of Botany. 1971;58(8):721-5.

- Dhingra H, Varghese T. Effect of salt stress on viability, germination and endogenous levels of some metabolites and ions in maize (Zea mays L.) pollen. Annals of Botany. 1985;55(3):415-20.

- El-Sayed H, Kirkwood R. Effects of NaCl salinity and hydrogel polymer treatments on viability, germination and solute contents in maize (Zea mays) pollen. 1992.

- Kiełkowska A, Grzebelus E, Lis-Krzyścin A, Maćkowska K. Application of the salt stress to the protoplast cultures of the carrot (Daucus carota L.) and evaluation of the response of regenerants to soil salinity. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC). 2019;137:379-95.

- Abdullah Z, Khan MA, Flowers T. Causes of sterility in seed set of rice under salinity stress. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science. 2001;187(1):25-32.

- Gerona MEB, Deocampo MP, Egdane JA, Ismail AM, Dionisio-Sese ML. Physiological responses of contrasting rice genotypes to salt stress at reproductive stage. Rice Science. 2019;26(4):207-19.

- Abdullah Z-u-N, Ahmad R, Ahmed J. Salinity induced changes in the reproductive physiology of wheat plants. Plant and cell Physiology. 1978;19(1):99-106.

- Hirasawa T, Sato K, Yamaguchi M, Narita R, Kodama A, Adachi S, et al. Differences in dry matter production, grain production, and photosynthetic rate in barley cultivars under long-term salinity. Plant Production Science. 2017;20(3):288-99.

- Kodama A, Narita R, Yamaguchi M, Hisano H, Adachi S, Takagi H, et al. QTLs maintaining grain fertility under salt stress detected by exome QTL-seq and interval mapping in barley. Breeding science. 2018;68(5):561-70.

- Huang Y, Bie Z, He S, Hua B, Zhen A, Liu Z. Improving cucumber tolerance to major nutrients induced salinity by grafting onto Cucurbita ficifolia. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2010;69(1):32-8.

- Ali M, Ayyub C, Shaheen MR, Qadri RWK, Khan I, Azam M, et al. Characterization of Water Melon (Citrullus lanatus) Genotypes under High Salinity Regime. American Journal of Plant Sciences. 2015;6(19):3260.

- Ekbic E, Cagıran C, Korkmaz K, Kose MA, Aras V. Assessment of watermelon accessions for salt tolerance using stress tolerance indices. Ciência e Agrotecnologia. 2017;41(6):616-25.

- Suárez-Hernández ÁM, Vázquez-Angulo JC, Grimaldo-Juárez O, Duran CC, González-Mendoza D, Bazante-González I, et al. Produção e qualidade de melancia enxertada, em solo salino. Horticultura Brasileira. 2019;37:215-20.

- Silva JSd, Sá FVdS, Dias NdS, Ferreira M, Jales GD, Fernandes PD. Morphophysiology of mini watermelon in hydroponic cultivation using reject brine and substrates. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental. 2021;25(6):402-8.

- Zong L, Tedeschi A, Xue X, Wang T, Menenti M, Huang C. Effect of different irrigation water salinities on some yield and quality components of two field-grown Cucurbit species. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry. 2011;35(3):297-307.

- Adriana S, Sá F, Souto L, Maria S, Romulo M, Geovani L, et al. Tolerance of Varieties and Hybrid of Pumpkin and Squash to Salt Stress. Journal of Agricultural Science. 2017;10:38-. [CrossRef]

- Brown C, Pezeshki S, DeLaune R. The effects of salinity and soil drying on nutrient uptake and growth of Spartina alterniflora in a simulated tidal system. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2006;58(1-3):140-8.

- Ahmad P, Jhon R. Effect of salt stress on growth and biochemical parameters of Pisum sativum L. (Einfluss von Salzstress auf Wachstum und biochemische Parameter von Pisum sativum L.). Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science. 2005;51(6):665-72.

- Colla G, Rouphael Y, Leonardi C, Bie Z. Role of grafting in vegetable crops grown under saline conditions. Scientia Horticulturae. 2010;127(2):147-55. [CrossRef]

- Rouphael Y, Cardarelli M, Schwarz D, Franken P, Colla G. Effects of drought on nutrient uptake and assimilation in vegetable crops. Plant responses to drought stress: from morphological to molecular features. 2012:171-95.

- Gaion LA, Braz L, Carvalho R. Grafting in Vegetable Crops: A Great Technique for Agriculture. International Journal of Vegetable Science. 2017;24:1-18. [CrossRef]

- Hashem A, Bayoumi YA, El-Shafik A, El-Zawily E-S, Tester M, Rakha MT. Interspeci fi c Hybrid Rootstocks Improve Productivity of Tomato Grown under High-temperature Stress. HortScience. 2024;59:129-37.

- Shaterian J, Georges F, Hussain A, Waterer D, De Jong H, Tanino KK. Root to shoot communication and abscisic acid in calreticulin (CR) gene expression and salt-stress tolerance in grafted diploid potato clones. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2005;53(3):323-32.

- Chen G, Fu X, Herman Lips S, Sagi M. Control of plant growth resides in the shoot, and not in the root, in reciprocal grafts of flacca and wild-type tomato (Lysopersicon esculentum), in the presence and absence of salinity stress. Plant and Soil. 2003;256:205-15.

- Santa-Cruz A, Martinez-Rodriguez MM, Perez-Alfocea F, Romero-Aranda R, Bolarin MC. The rootstock effect on the tomato salinity response depends on the shoot genotype. Plant Science. 2002;162(5):825-31.

- Zhu J, Bie Z, Huang Y, Han X. Effect of grafting on the growth and ion concentrations of cucumber seedlings under NaCl stress. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2008;54(6):895-902.

- Liu ZhengLu LZ, Zhu YueLin ZY, Wei GuoPing WG, Yang LiFei YL, Zhang GuWen ZG, Hu ChunMei HC. Metabolism of ascorbic acid and glutathione in leaves of grafted eggplant seedlings under NaCl stress. 2007.

- Goreta S, Bucevic-Popovic V, Selak GV, Pavela-Vrancic M, Perica S. Vegetative growth, superoxide dismutase activity and ion concentration of salt-stressed watermelon as influenced by rootstock. The Journal of Agricultural Science. 2008;146(6):695-704.

- Yetisir H, Uygur V. Responses of grafted watermelon onto different gourd species to salinity stress. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 2010;33(3):315-27.

- Edelstein M, Ben-Hur M, Cohen R, Burger Y, Ravina I. Boron and salinity effects on grafted and non-grafted melon plants. Plant and Soil. 2005;269:273-84.

- Ulas A, Aydin A, Ulas F, Yetisir H, Miano TF. Cucurbita rootstocks improve salt tolerance of melon scions by inducing physiological, biochemical and nutritional responses. Horticulturae. 2020;6(4):66.

- Oliveira CEdS, Steiner F, Zuffo AM, Zoz T, Alves CZ, Aguiar VCBd. Seed priming improves the germination and growth rate of melon seedlings under saline stress. Ciência Rural. 2019;49(7):e20180588.

- Napolitano M, Terzaroli N, Kashyap S, Russi L, Jones-Evans E, Albertini E. Exploring heterosis in melon (Cucumis melo L.). Plants. 2020;9(2):282.

- Mitra D, Shnaider Y, Bar-Ziv A, Brotman Y, Perl-Treves R, editors. First fruit inhibition and CRISPR-Cas9 inactivation of candidate genes to study the control of cucumber fruit set. VI International Symposium on Cucurbits 1294; 2019.

- Zhu H, Zhao S, Lu X, He N, Gao L, Dou J, et al. Genome duplication improves the resistance of watermelon root to salt stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2018;133:11-21. [CrossRef]

- Yanyan Y, Shuoshuo W, Min W, Biao G, Qinghua S. Effect of different rootstocks on the salt stress tolerance in watermelon seedlings. Horticultural plant journal. 2018;4(6):239-49.

- Mo Y, Wang Y, Yang R, Zheng J, Liu C, Li H, et al. Regulation of plant growth, photosynthesis, antioxidation and osmosis by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus in watermelon seedlings under well-watered and drought conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;7:644.

- Gao B-w, Sun D-x, Yuan G-p, An G-l, Li W, Liu J-p, et al. Identification of salt tolerance of 121 watermelon (Citrullus lanatus L.) germplasm resources. 2022.

- Sarabi B, Bolandnazar S, Ghaderi N, Ghashghaie J. Genotypic differences in physiological and biochemical responses to salinity stress in melon (Cucumis melo L.) plants: Prospects for selection of salt tolerant landraces. Plant physiology and biochemistry. 2017;119:294-311.

- Fan R, Zhang B, Li J, Zhang Z, Liang A. Straw-derived biochar mitigates CO2 emission through changes in soil pore structure in a wheat-rice rotation system. Chemosphere. 2020;243:125329.

- Qadir M, Quillérou E, Nangia V, Murtaza G, Singh M, Thomas RJ, et al., editors. Economics of salt-induced land degradation and restoration. Natural resources forum; 2014: Wiley Online Library.

- Qiang X, Sun Z, Li X, Li S, Yu Z, He J, et al. The impacts of planting patterns combined with irrigation management practices on soil water content, watermelon yield and quality. Agroforestry Systems. 2024;98(4):979-94.

- Santos AdS, Sá FdS, Souto LS, Silva MdN, Moreira RC, Lima Gd, et al. Tolerance of varieties and hybrid of pumpkin and squash to salt stress. 2018.

- Alves AdS, Oliveira FdAd, Silva DDd, Santos STd, Oliveira RR, Góis HMdM. Production and quality of mini watermelon under salt stress and K+/Ca2+ ratios. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental. 2023;27(6):441-6.

- Silva SSd, Lima GSd, Lima VLAd, Gheyi HR, Soares LAdA, Lucena RCM. Gas exchanges and production of watermelon plant under salinity management and nitrogen fertilization. Pesquisa Agropecuária Tropical. 2019;49:e54822.

- Rouphael Y, Colla G. Biostimulants in agriculture. Frontiers Media SA; 2020. p. 40.

- Singh M, Subahan GM, Sharma S, Singh G, Sharma N, Sharma U, et al. Enhancing Horticultural Sustainability in the Face of Climate Change: Harnessing Biostimulants for Environmental Stress Alleviation in Crops. Stresses. 2025;5(1):23.

- Bantis F, Koukounaras A. Ascophyllum nodosum and silicon-based biostimulants differentially affect the physiology and growth of watermelon transplants under abiotic stress factors: The case of salinity. Plants. 2023;12(3):433.

- Bijalwan P, Jeddi K, Saini I, Sharma M, Kaushik P, Hessini K. Mitigation of saline conditions in watermelon with mycorrhiza and silicon application. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021;28(7):3678-84.

- Ghani MI, Yi B, Rehmani MS, Wei X, Siddiqui JA, Fan R, et al. Potential of melatonin and Trichoderma harzianum inoculation in ameliorating salt toxicity in watermelon: Insights into antioxidant system, leaf ultrastructure, and gene regulation. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2024;211:108639.

- Lugtenberg B, Kamilova F. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annual review of microbiology. 2009;63(1):541-56.

- Yadav G, Vishwakarma K, Sharma S, Kumar V, Upadhyay N, Kumar N, et al. Emerging significance of rhizospheric probiotics and its impact on plant health: current perspective towards sustainable agriculture. Probiotics and plant health. 2017:233-51.

- Bulgarelli D, Rott M, Schlaeppi K, Ver Loren van Themaat E, Ahmadinejad N, Assenza F, et al. Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature. 2012;488(7409):91-5.

- Ganesh J, Hewitt K, Devkota AR, Wilson T, Kaundal A. IAA-producing plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from Ceanothus velutinus enhance cutting propagation efficiency and Arabidopsis biomass. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty P, Singh PK, Chakraborty D, Mishra S, Pattnaik R. Insight into the role of PGPR in sustainable agriculture and environment. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 2021;5:667150.

- Coats VC, Rumpho ME. The rhizosphere microbiota of plant invaders: an overview of recent advances in the microbiomics of invasive plants. Frontiers in microbiology. 2014;5:368.

- Acharya BR, Gill SP, Kaundal A, Sandhu D. Strategies for combating plant salinity stress: the potential of plant growth-promoting microorganisms. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2024;Volume 15 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ganesh J, Singh V, Hewitt K, Kaundal A. Exploration of the rhizosphere microbiome of native plant Ceanothus velutinus–an excellent resource of plant growth-promoting bacteria. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2022;13:979069.

- Fotoohiyan Z, Samiei F, Sardoei AS, Kashi F, Ghorbanpour M, Kariman K. Improved salinity tolerance in cucumber seedlings inoculated with halotolerant bacterial isolates with plant growth-promoting properties. BMC Plant Biology. 2024;24(1):821.

- Yetisir H, Uygur V. Plant Growth and Mineral Element Content of Different Gourd Species and Watermelon under Salinity Stress. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry. 2009;33:65-77. [CrossRef]

- Freire MHdC, Sousa GGd, de Souza MV, de Ceita ED, Fiusa JN, Leite KN. Emergência e acúmulo de biomassa em plântulas de cultivares de arroz irrigadas com águas salinas. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental. 2018;22:471-5.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).