Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: CHARMM-GUI and GROMACS

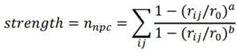

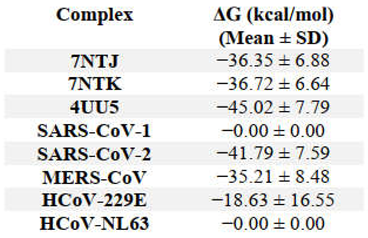

2.2. Binding Free Energy Calculations (MM/GBSA): gmx_MMPBSA

2.3. Secondary Structure Analysis of the E Peptides: gmx dssp

2.4. Interaction Analysis Between the hCoV E Peptide and PALS1 Residues: MDAnalysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Trajectory Analysis: RMSD, RMSF, Rg, SASA

3.2. Binding Free Energy Calculations (MM/GBSA)

3.3. Secondary Structure Analysis of the E Peptides: gmx dssp

3.4. Interaction Analysis Between the hCoV E Peptide and PALS1 Residues: MDAnalysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Consent for Publication

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Masters, P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 2006, 66: 193-292. [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, D.; Gordon, B.; Fielding, B.C. Coronaviruses. In: Rezaei N, editor. Encyclopedia of Infection and Immunity. Oxford: Elsevier; 2022. p. 241-58. [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Lai, A.C.K.; et al. Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24 (6): 490-502. [CrossRef]

- Casadevall, A.; Pirofski, L. Host-pathogen interactions: the attributes of virulence. J Infect Dis. 2001, 184 (3): 337-44. [CrossRef]

- Triggle, C.R.; Bansal, D.; Ding, H.; Islam, M.M.; Farag, E.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Viral Characteristics, Transmission, Pathophysiology, Immune Response, and Management of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 as a Basis for Controlling the Pandemic. Front Immunol. 2021, 12: 631139. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; DeDiego, M.L.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; et al. The PDZ-Binding Motif of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Envelope Protein Is a Determinant of Viral Pathogenesis. Plos Pathog. 2014, 10 (8). [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Yla-Anttila, P.; Sandalova, T.; Sun, R.; Achour, A.; Masucci, M.G. 14-3-3 scaffold proteins mediate the inactivation of trim25 and inhibition of the type I interferon response by herpesvirus deconjugases. Plos Pathog. 2019, 15 (11): e1008146. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Matrenec, R.; Gack, M.U.; He, B. Disassembly of the TRIM23-TBK1 Complex by theUs11 Protein of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Impairs Autophagy. J Virol. 2019, 93 (17). [CrossRef]

- Willey, R.L.; Maldarelli, F.; Martin, M.A.; Strebel, K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpu protein induces rapid degradation of CD4. J Virol. 1992, 66 (12): 7193-200. [CrossRef]

- Barro, M.; Patton, J.T. Rotavirus nonstructural protein 1 subverts innate immune response by inducing degradation of IFN regulatory factor 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102 (11): 4114-9. [CrossRef]

- Almazán, F.; DeDiego, M.L.; Sola, I.; Zuñiga, S.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; et al. Engineering a -Competent, Propagation-Defective Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus as a Vaccine Candidate. Mbio. 2013, 4 (5): e00650-13. [CrossRef]

- Boson, B.; Legros, V.; Zhou, B.J.; Siret, E.; Mathieu, C.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 envelope and membrane proteins modulate maturation and retention of the spike protein, allowing assembly of virus-like particles. J Biol Chem. 2021, 296 (100111). [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.; Masters, P.S. The Small Envelope Protein E Is Not Essential for Murine Coronavirus Replication. Journal of Virology. 2003, 77 (8): 4597-608. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.T.; Wang, S.M.; Huang, K.J.; Wang, C.T. SARS-CoV envelope protein palmitoylation or nucleocapid association is not required for promoting virus-like particle production. J Biomed Sci. 2014, 21 (34). [CrossRef]

- Westerbeck, J.W.; Machamer, C.E. The Infectious Bronchitis Coronavirus Envelope Protein Alters Golgi pH To Protect the Spike Protein and Promote the Release of Infectious Virus. J Virol. 2019, 93 (11). [CrossRef]

- Caillet-Saguy, C.; Durbesson, F.; Rezelj, V.V.; Gogl, G.; Tran, Q.D.; et al. Host PDZ-containing proteins targeted by SARS-CoV-2. Febs J. 2021, 288 (17): 5148-62. [CrossRef]

- Honrubia, J.M.; Gutierrez-Alvarez, J.; Sanz-Bravo, A.; González-Miranda, E.; Muñoz-Santos, D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-Mediated Lung Edema and Replication Are Diminished by Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Modulators. Mbio. 2023, 14 (1). [CrossRef]

- Luck, K.; Charbonnier, S.; Travé, G. The emerging contribution of sequence context to the specificity of protein interactions mediated by PDZ domains. Febs Lett. 2012, 586 (17): 2648-61. [CrossRef]

- Nourry, C.; Grant, S.G.; Borg, J.P. PDZ domain proteins: plug and play! Sci STKE. 2003, 2003 (179): RE7. [CrossRef]

- Luck, K.; Charbonnier, S.; Trave, G. The emerging contribution of sequence context to the specificity of protein interactions mediated by PDZ domains. Febs Lett. 2012, 586 (17): 2648-61. [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.Z.; Lim, W.A. Mechanism and role of PDZ domains in signaling complex assembly. JCell Sci. 2001, 114 (Pt 18): 3219-31. [CrossRef]

- Songyang, Z.; Fanning, A.S.; Fu, C.; Xu, J.; Marfatia, S.M.; et al. Recognition of unique carboxyl- terminal motifs by distinct PDZ domains. Science. 1997, 275 (5296): 73-7. [CrossRef]

- Teoh, K.T.; Siu, Y.L.; Chan, W.L.; Schlüter, M.A.; Liu, C.J.; et al. The SARS Coronavirus E Protein Interacts with PALS1 and Alters Tight Junction Formation and Epithelial Morphogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010, 21 (22): 3838-52. [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, D.; Cloete, R.; Fielding, B.C. The Flexible, Extended Coil of the PDZ-Binding Motif of the Three Deadly Human Coronavirus E Proteins Plays a Role in Pathogenicity. Viruses- Basel. 2022, 14 (8). [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, D.; Fielding, B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol J. 2019, 16 (1): 69. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Jang, G.M.; Bouhaddou, M.; Xu, J.W.; Obernier, K.; et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020, 583 (7816): 459. [CrossRef]

- Kruse, T.; Benz, C.; Garvanska, D.H.; Lindqvist, R.; Mihalic, F.; et al. Large scale discovery of coronavirus-host factor protein interaction motifs reveals SARS-CoV-2 specific mechanisms and vulnerabilities. Nat Commun. 2021, 12 (1). [CrossRef]

- Baliova, M.; Jahodova, I.; Jursky, F. A Significant Difference in Core PDZ Interactivity of SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV2 and MERS-CoV Protein E Peptide PDZ Motifs In Vitro. Protein J. 2023, 42 (4): 253-62. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Hiatt, J.; Bouhaddou, M.; Rezelj, V.V.; Ulferts, S.; et al. Comparative host- coronavirus protein interaction networks reveal pan-viral disease mechanisms. Science. 2020, 370 (6521). [CrossRef]

- May, D.G.; Martin-Sancho, L.; Anschau, V.; Liu, S.; Chrisopulos, R.J.; et al. A BioID-Derived Proximity Interactome for SARS-CoV-2 Proteins. Viruses. 2022, 14 (3). [CrossRef]

- Stukalov, A.; Girault, V.; Grass, V.; Karayel, O.; Bergant, V.; et al. Multilevel proteomics reveals host perturbations by SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Nature. 2021, 594 (7862): 246-52. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gupta, S.; Paramo, M.I.; Hou, Y.; et al. A comprehensive SARS-CoV-2-human protein-protein interactome reveals COVID-19 pathobiology and potential host therapeutic targets. Nat Biotechnol. 2023, 41 (1): 128-39. [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Fogg, V.C.; Margolis, B. Tight junctions and cell polarity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006, 22: 207-35. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.E.; Fletcher, G.C.; O'Reilly, N.; Purkiss, A.G.; Thompson, B.J.; McDonald, N.Q. Structures of the human Pals1 PDZ domain with and without ligand suggest gated access of Crb to the PDZ peptide-binding groove. Acta Crystallogr D. 2015, 71: 555-64. [CrossRef]

- Tepass, U. The Apical Polarity Protein Network in Epithelial Cells: Regulation of Polarity, Junctions, Morphogenesis, Cell Growth, and Survival. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2012, 28: 655-85. [CrossRef]

- Javorsky, A.; Humbert, P.O.; Kvansakul, M. Structural basis of coronavirus E protein interactions with human PALS1 PDZ domain. Commun Biol. 2021, 4 (1): 724. [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Cai, Y.; Pang, C.; Wang, L.; McSweeney, S.; et al. Structural basis for SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein recognition of human cell junction protein PALS1. Nat Commun. 2021, 12(1): 3433. [CrossRef]

- Kuiken, T.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Schutten, M.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; van Amerongen, G.; et al. Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003, 362 (9380): 263-70. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.M.; Poon, L.L.M.; Lee, K.C.; Ng, W.F.; Lai, S.T.; et al. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003, 361 (9371): 1773-8. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015, 1-2: 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Lo Cascio, E.; Toto, A.; Babini, G.; De Maio, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; et al. Structural determinants driving the binding process between PDZ domain of wild type human PALS1 protein and SLiM sequences of SARS-CoV E proteins. Comput Struct Biotec. 2021, 19: 1838-47. [CrossRef]

- De Maio, F.; Lo Cascio, E.; Babini, G.; Sali, M.; Della Longa, S.; et al.

- COVID-19 pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 2020, 22 (10): 592-7. [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J Comput Chem. 2008, 29 (11): 1859-65. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, A.; Dinner, A.R. Monte Carlo simulations of biomolecules: The MC module in CHARMM. J Comput Chem. 2006, 27 (2): 203-16. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; et al. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat Methods. 2017, 14 (1): 71-3. [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.R.; 3rd McGee, T.D.; Jr Swails, J.M.; Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H.; Roitberg, A.E. MMPBSA.py: An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012, 8 (9): 3314-21. [CrossRef]

- Valdes-Tresanco, M.S.; Valdes-Tresanco, M.E.; Valiente, P.A.; Moreno, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J Chem Theory Comput. 2021, 17 (10): 6281-91. [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.A.; Martinez, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Wickstrom, L.; Hauser, K.E.; Simmerling, C. ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015, 11 (8): 3696-713. [CrossRef]

- Onufriev, A.; Bashford, D.; Case, D.A. Exploring protein native states and large-scale conformational changes with a modified generalized born model. Proteins. 2004, 55 (2): 383-94. [CrossRef]

- Sitkoff, D.; Sharp, K.A.; Honig, B. Accurate Calculation of Hydration Free Energies Using Macroscopic Solvent Models. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1994, 98 (7): 1978-88. [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Tan, Y.H.; Luo, R. Implicit nonpolar solvent models. J Phys Chem B. 2007, 111 (42): 12263-74. [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.Z. Interaction Entropy: A New Paradigm for Highly Efficient and Reliable Computation of Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energy. J Am Chem Soc. 2016, 138(17): 5722-8. [CrossRef]

- Gorelov, S.; Titov, A.; Tolicheva, O.; Konevega, A.; Shvetsov, A. DSSP in GROMACS: Tool for Defining Secondary Structures of Proteins in Trajectories. J Chem Inf Model. 2024, 64 (9): 3593-8. [CrossRef]

- Kabsch, W.; Sander, C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983, 22 (12): 2577-637. [CrossRef]

- Giacon, N.; Lo Cascio, E.; Davidson, D.S.; Poleto, M.D.; Lemkul, J.A.; et al. Monomeric and dimeric states of human ZO1-PDZ2 are functional partners of the SARS-CoV-2 E protein. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023, 21: 3259-71. [CrossRef]

- Michaud-Agrawal, N.; Denning, E.J.; Woolf, T.B.; Beckstein, O. MDAnalysis: a toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 2011, 32 (10): 2319-27. [CrossRef]

- Mitusińska, K.; Skalski, T.; Góra, A. Simple Selection Procedure to Distinguish between Static and Flexible Loops. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020, 21 (7): 2293. [CrossRef]

- Barozet, A.; Chacon, P.; Cortes, J. Current approaches to flexible loop modeling. Curr Res Struct Biol. 2021, 3: 187-91. [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.J.; Benson, M.L.; Smith, R.D.; Carlson, H.A. Inherent versus induced protein flexibility: Comparisons within and between apo and holo structures. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019, 15 (1): e1006705. [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, L.; Cavazzini, D.; Rossi, G.L.; Lucke, C. New insights on the protein-ligand interaction differences between the two primary cellular retinol carriers. J Lipid Res. 2010, 51 (6): 1332-43. [CrossRef]

- Toto, A.; Ma, S.; Malagrino, F.; Visconti, L.; Pagano, L.; et al. Comparing the binding properties of peptides mimicking the Envelope protein of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 to the PDZ domain of the tight junction-associated PALS1 protein. Protein Sci. 2020, 29 (10): 2038-42. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wan, Q.; Du, Q.; Zhang, M. Structure of Crumbs tail in complex with the PALS1 PDZ-SH3-GK tandem reveals a highly specific assembly mechanism for the apical Crumbs complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014, 111 (49): 17444-9. [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.K.; Dill, K.A. Folding Very Short Peptides Using Molecular Dynamics. PLOS Computational Biology. 2006, 2 (4): e27. [CrossRef]

- Argudo, P.G.; Giner-Casares, J.J. Folding and self-assembly of short intrinsically disordered peptides and protein regions. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3 (7): 1789-812. [CrossRef]

- Chandrappa, S.; Madhusudana Reddy, M.B.; Sonti, R.; Basuroy, K.; Raghothama, S.; Balaram, P. Directing peptide conformation with centrally positioned pre-organized dipeptide segments: studies of a 12-residue helix and beta-hairpin. Amino Acids. 2015, 47 (2): 291-301. [CrossRef]

- Mitusinska, K.; Skalski, T.; Gora, A. Simple Selection Procedure to Distinguish between Static and Flexible Loops. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21 (7). [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, M.; Hagerman, P.J. The influence of symmetric internal loops on the flexibility of RNA. J Mol Biol. 1996, 257 (2): 276-89. [CrossRef]

- Gogl, G.; Zambo, B.; Kostmann, C.; Cousido-Siah, A.; Morlet, B.; et al. Quantitative fragmentomics allow affinity mapping of interactomes. Nat Commun. 2022, 13 (1): 5472. [CrossRef]

- Pennacchietti, V.; Toto, A. Different electrostatic forces drive the binding kinetics of SARS- CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV Envelope proteins with the PDZ2 domain of ZO1. Sci Rep. 2023, 13 (1): 7906. [CrossRef]

- Arold, S.; O'Brien, R.; Franken, P.; Strub, M.P.; Hoh, F.; et al. RT loop flexibility enhances the specificity of Src family SH3 domains for HIV-1 Nef. Biochemistry. 1998, 37 (42): 14683-91. [CrossRef]

- de Vega, M.J.; Martin-Martinez, M.; Gonzalez-Muniz, R. Modulation of protein-protein interactions by stabilizing/mimicking protein secondary structure elements. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007, 7 (1): 33-62. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, K.W.; Buus, S.; Nielsen, M. Structural properties of MHC class II ligands, implications for the prediction of MHC class II epitopes. PLoS One. 2010, 5 (12): e15877. [CrossRef]

- Duart, G.; Garcia-Murria, M.J.; Grau, B.; AcostA–Caceres, J.M.; Martinez-Gil, L.; Mingarro, I. SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein topology in eukaryotic membranes. Open Biol. 2020, 10 (9): 200209. [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, D.; Fielding, B.C. Is There a Link Between the Pathogenic Human Coronavirus Envelope Protein and Immunopathology? A Review of the Literature. Front Microbiol. 2020, 11: 2086. [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, M.H.; Mahmanzar, M.; Rahimian, K.; Mahdavi, B.; Tokhanbigli, S.; et al. Global landscape of SARS-CoV-2 mutations and conserved regions. J Transl Med. 2023, 21 (1):152. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hoque, M.N.; Islam, M.R.; Islam, I.; Mishu, I.D.; et al. Mutational insights into the envelope protein of SARS-CoV-2. Gene Rep. 2021, 22: 100997. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, X.; Ji, H.; Zuo, X.; Xiao, G.F.; et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein mutations on the pathogenicity of Omicron XBB. Cell Discov. 2023, 9 (1): 80. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Melnychuk, S.; Sandstrom, P.; Ji, H. Tracking the evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant of concern: analysis of genetic diversity and selection across the whole viral genome. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14: 1222301. [CrossRef]

- Akkiz, H. The Biological Functions and Clinical Significance of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Corcern. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022, 9: 849217. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Hiatt, J.; Bouhaddou, M.; Rezelj, V.V.; Ulferts, S.; et al. Comparative host- coronavirus protein interaction networks reveal pan-viral disease mechanisms. Science. 2020, 370 (6521). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Alvarez, F.; Wolff, N.; Mechaly, A.; Brule, S.; et al. Interactions of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Protein E With Cell Junctions and Polarity PSD- 95/Dlg/ZO-1-Containing Proteins. Front Microbiol. 2022, 13: 829094. [CrossRef]

- Arbour, N.; Day, R.; Newcombe, J.; Talbot, P.J. Neuroinvasion by human respiratory coronaviruses. J Virol. 2000, 74 (19): 8913-21. [CrossRef]

- Arbour, N.; Ekande, S.; Cote, G.; Lachance, C.; Chagnon, F.; et al. Persistent infection of human oligodendrocytic and neuroglial cell lines by human coronavirus 229E. J Virol. 1999, 73 (4): 3326-37. [CrossRef]

- Bonavia, A.; Arbour, N.; Yong, V.W.; Talbot, P.J. Infection of primary cultures of human neural cells by human coronaviruses 229E and OC43. J Virol. 1997, 71 (1): 800-6. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.N.; Mounir, S.; Talbot, P.J. Human coronavirus gene expression in the brains of multiple sclerosis patients. Virology. 1992, 191 (1): 502-5. [CrossRef]

- Cristallo, A.; Gambaro, F.; Biamonti, G.; Ferrante, P.; Battaglia, M.; Cereda, P.M. Human coronavirus polyadenylated RNA sequences in cerebrospinal fluid from multiple sclerosis patients. New Microbiol. 1997, 20 (2): 105-14.

- Jimenez-Guardeno, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; DeDiego, M.L.; Castano-Rodriguez, C.; et al. Identification of the Mechanisms Causing Reversion to Virulence in an Attenuated SARS-CoV for the Design of a Genetically Stable Vaccine. Plos Pathog. 2015, 11 (10): e1005215. [CrossRef]

- Stodola, J.K.; Dubois, G.; Le Coupanec, A.; Desforges, M.; Talbot, P.J. The OC43 human coronavirus envelope protein is critical for infectious virus production and propagation in neuronal cells and is a determinant of neurovirulence and CNS pathology. Virology. 2018, 515: 134-49. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).