1. Introduction

Myocardial bridging (MB) is defined as an intramyocardial segment of an epicardial coronary artery [

1]. Although MB can theoretically involve any segment of the coronary tree, the majority (approximately 60%) occur in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) [

2]. Myocardial bridges are typically classified as superficial or deep, depending on the anatomical arrangement and depth of myocardial fibres. The true prevalence of MB remains a subject of debate, as it varies significantly based on the definition applied and the modality used for identification, including autopsy, computed tomography (CT), or intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) [

1]. Notably, the frequency of MB in the LAD is reported to exceed 50% in autopsy studies, whereas it is identified in fewer than 5% of cases by angiography [

3,

4] .

The advent of multi-detector CT has markedly improved the detection rate of MB, particularly when the myocardial bridge is greater than 1 mm in thickness, yielding a sensitivity comparable to that of autopsy studies [

5]. Although the majority of cases are asymptomatic, MB has been associated with angina, exertional dyspnoea, ventricular arrhythmias, syncope, and, in rare cases, sudden cardiac death [

6,

7]. In the majority of cases, it is an incidental finding with 97% survival at 5 years. These pathologic associations are typically seen in patients with associated myocardial ischemia and/or concurrent atherosclerosis [

8].

Invasive coronary angiography (ICA) remains an important diagnostic tool, although its sensitivity for detecting MB is relatively low, at approximately 5% [

3]. The use of IVUS has enhanced the sensitivity of ICA in detecting systolic compression within a bridged segment [

9]. ICA may also be used for functional assessment of MB using fractional flow reserve (FFR). Invasive FFR (iFFR) has emerged as a gold standard technique for assessing coronary lesions following evidence in the FAME [

10] and DEFER [

11] trials showing improved outcomes in the setting of PCI. Despite this, the evidence is not as strong in the context of myocardial bridging, in which there is dynamic rather than fixed obstruction of coronary blood flow. Dobutamine-stress diastolic FFR (dFFR) has been considered as the reference standard for the physiologic assessment of MB given its increased ability to identify hemodynamically significant MB when compared with standard FFR [

12]. However, these techniques are more invasive than standard coronary angiography and are not feasible for use in the routine evaluation of patients.

Management of MB is typically conservative, with a focus on treating anginal symptoms and associated coronary artery disease (CAD). Medical treatments include beta-blockers due to their ability to reduce heart rate and contractility while prolonging diastolic coronary filling. Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers may be considered as adjunct therapy, given their vasodilatory effects [

13]. In cases where symptoms are refractory to medical management, surgical intervention, such as myotomy or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), may be warranted. Myotomy is generally preferred in the absence of concomitant obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) due to the risks associated with CABG, including graft failure secondary to competitive flow [

14]. Stent implantation is not routinely performed because of high rates of in-stent restenosis and stent fracture [

15,

16].

2. CCTA and Myocardial Bridging

CCTA, equipped with its multiplane and three-dimensional functionalities, has notably increased the detection of MBs. Inevitably, many of these will be incidental findings. However, the clinical relevance of MBs is often unclear and functional assessment remains key in the accurate detection of hemodynamically significant bridging, which is necessary to guide adequate treatment. Functional and dynamic studies are therefore of utmost relevance.

Current strategies used for the assessment of myocardial ischemia include invasive FFR, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), nuclear MPI and dynamic CT-MPI. The latter has been established in the literature as an accurate method for diagnosing myocardial ischemia when compared with the former techniques [

17,

18,

19,

20], highlighting the utility of CT in cardiac imaging, and represents an alternative to invasive assessment, nuclear MPI and CMR-MPI. These tools are well evidenced in the setting of atherosclerotic disease, with a less established role in the assessment of MB-related ischemia.

Standard CCTA, being primarily an anatomical assessment, has limitations in evaluating the functional consequences of MB. While CCTA can depict systolic narrowing of the lumen, it does not directly quantify the hemodynamic impact of the MB on myocardial perfusion.

The addition of alternative techniques can enhance CCTA. For example, stress-rest dynamic CT-MPI can be used to assess the hemodynamic significance of MB. CCTA in conjunction with stress-rest dynamic-CT MPI can allow the detection of MB, evaluation of functional significance and can ultimately guide patient management in a “one-stop shop” examination as described by Schicchi et al. [

21] The advantage of this is that, once MB is identified on CT, the same modality can then be used to assess the bridge without the patient needing to undergo secondary imaging via SPECT/CMR or ICA. The total patient-time is about 30 minutes. Moreover, CT-MPI offers a lower mean dose of radiation (6,8 mSv) as compared to SPECT (10,4 mSv). Given that MB is a commonly encountered finding on CCTA, the ability to promptly assess the relevance of such findings has the potential to reduce costs and harm to patients and allows earlier effective treatment. These techniques, however, have never been validated in the context of MB-related ischemia and their use remains non-guideline backed and not entirely evidence based due to a lack of rigorous prospective studies and controlled trials.

Novel techniques are emerging, including the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in conjunction with CCTA, that may improve the assessment of MB. Given the challenges associated with an ever-increasing volume of imaging studies and the associated incidental diagnoses of MB, innovative tools will be required to accurately assess the significance and implications of these lesions and guide both the need for treatment and appropriate treatment strategies. The increased clinical complexity poses a challenge to radiologists and clinicians in what to do with these lesions; on the part of the radiologist – whether to report on them or not, and on the part of the clinician – what to do with this information once reported on. It would be unfeasible, both in terms of costs to healthcare systems and due to time and utilization of facilities, and indeed harmful to offer invasive assessment to this increasingly large number of patients with MB identified on imaging. The above described “one-stop shop” examination poses an ideal solution to this problem, though one that remains, as yet, not feasible in clinical practice.

3. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in CCTA

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are emerging technologies that are becoming pivotal in advancing cardiac imaging, particularly in the context of CCTA. These technologies enhance image acquisition, segmentation, anatomical detection, motion correction, quantitative analysis and evaluation of functional significance, addressing the increasing complexity and volume of cardiovascular imaging data [

22,

23].

Even though the terms AI, ML and deep learning (DL) are often used synonymously, they are all fundamentally hierarchical [

24]. In fact, artificial intelligence technology can be mainly divided into machine learning and intelligent computing. ML is the main technology of AI, which includes supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and deep learning. Specifically, supervised learning includes artificial neural network (ANN), support vector machine (SVM), decision tree, Random Forest (RF), naive Bayes classifier, and K-nearest neighbor (k-NN) algorithm. Unsupervised learning mainly includes clustering algorithms and association rule algorithms. DL contains convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and deep neural networks (DNNs). AI technology differs in its applications and limitations for different data types. Therefore, the accurate diagnosis of coronary artery disease can only be achieved by finding an appropriate intelligent mathematical model to match the CCTA imaging data [

25].

The role of AI in the evaluation of MB is still experimental and under study, but there are established benefits of AI in CCTA. AI algorithms, especially CNNs, can process large data sets rapidly, constructing images faster than traditional methods. CNNs enable automatic segmentation of coronary arteries, identification of systolic compression, and estimation of functional indices, with high accuracy and direct image-based learning. Compared to traditional supervised models such as random forests or support vector machines which require manual feature extraction. CNNs offer superior performance in tasks relevant to MB by leveraging large imaging datasets and learning directly from pixel-level data [

22,

26,

27].

One of the significant advantages of AI in CCTA is its ability to produce high-quality images with reduced radiation exposure; AI algorithms can optimize imaging parameters and enhance image clarity, ensuring accurate diagnostics with smaller radiation doses compared to conventional methods. AI can also automate several critical processes in cardiac CT imaging, including segmentation, risk stratification, and assessing coronary calcium levels. Automation of these processes increases efficiency and ensures consistency and accuracy in diagnostics. AI also enables capturing more images along multiple planes, facilitating advanced 3D reconstruction and visualization of cardiac structures [

28].

4. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Myocardial Bridging

Specific techniques of interest in assessing MBs are listed below (

Table 1):

AI-enhanced segmentation and reconstruction.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) which predicts blood flow dynamics and hemodynamic effects.

CT-derived fractional flow reserve (CT-FFR), a ML technique which is particularly exciting and has already been established as a tool for assessing the functional significance of stenotic coronary lesions as an alternative to invasive FFR.

Table 1.

Summary of AI techniques of interest for assessment of MB.

Table 1.

Summary of AI techniques of interest for assessment of MB.

| |

Purpose |

Type |

Requirements |

Functional or anatomical |

| AI-enhanced segmentation and reconstruction |

Analysis of images to identify regions of interest, enhance image quality and assess ischemia |

Imaging + AI-based analysis |

CT, MRI or US images |

Functional, anatomical |

| CFD |

Simulate and analyze blood flow dynamics within vessels or the heart |

Imaging + simulation |

CT scan with contrast agent, computational modeling |

Functional |

| CT-FFR |

Assessment of functional significance of stenosis by simulating blood flow |

Imaging + simulation + ML-based analysis |

CT scan with contrast agent, computational modeling |

Functional |

4.1. AI-Enhanced Segmentation and Reconstruction

Heart segmentation is the process of delineating different anatomical structures of the heart from medical imaging techniques such as MRI, CT scans, and echocardiography [

29]. The method relies on fully connected neural networks (FCNN) such as U-Net [

30]. AI-enhanced segmentation enables detailed analysis of the heart's four chambers, valves, arteries, and veins, as well as the identification of pathophysiological lesions such as myocardial infarction, ischemia, and cardiomyopathy. This facilitates pre-surgical planning, device design, and real-time monitoring of heart disease [

31]. Traditionally, heart segmentation was performed manually, which was both time-consuming and labor-intensive. The introduction of automated analysis has reduced error rates and hastened clinical diagnosis. As a result, AI-enhanced segmentation is now widely adapted in cardiac clinics, aiding in the evaluation of cardiac function, wall thickness, and other key risk assessment metrics[

29]. Reconstruction algorithms and techniques can be used to enhance image quality, perform motion correction, identify structures of interest [

32,

33] as well as streamline workflows by automating post-processing and analysis including functions such as cross-sectioning, volume rendering, multi-planar reformation and curved planar reformation techniques [

34]. Specific uses of these functions and applications to MB have been demonstrated in several studies [

35,

36,

37,

38], including motion correction models for improving image quality, automated reconstruction and segmentation of coronary arteries, coronary stenosis/plaques and identification of bridged segments.

4.2. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

CFD enables precise modeling of intracoronary hemodynamics and has numerous applications in cardiology. For instance, it is used to create patient-specific 3D coronary artery geometries, allowing visualization of specific vascular segments with a resolution of approximately 1mm or lower. These reconstructions are derived from imaging data such as invasive coronary angiography (ICA), computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA), intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), and optical coherence tomography (OCT). The selected vascular segment is then subdivided into smaller elements (meshing) and applies mathematical model to solve fluid motion equitation. These simulations help evaluate blood velocity and pressure gradients within arteries, wall shear stress that is a factor in plaque formation and progression, and microvascular resistance which allows ischemic assessment [

39,

40,

41,

42]. CFD is also used in transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) for pre-procedural planning, device optimization, and post-procedural assessment including hemodynamic evaluation, valve size and positioning, paravalvular leak prediction, left ventricular workload and coronary perfusion impact [

43]. With regards to MB, CFD has been used experimentally to study and model the hemodynamic impact of MB by combining ICA and IVUS data [

44,

45]. A more practical and utilized application of CFD is in CT-FFR.

4.3. CT-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve (CT-FFR)

CT-FFR is a CFD based method using ML and computational modeling in conjunction with data from CCTA to estimate FFR [

46]. Current evidence suggests that CT-FFR is a promising alternative to invasive FFR, the current gold standard for evaluating coronary lesion-specific ischemia [

47,

48,

49]. Trials (DISCOVER-FLOW, NXT) have demonstrated the diagnostic accuracy and discrimination of CT-FFR when compared to invasive FFR for the assessment of CAD [

50,

51]. The most used and the only U.S. Food and Drug (FDA)-approved method is HeartFlow, which applies CFD with remote supercomputers. It creates a personalized three-dimensional (3D) model of the coronary arteries using semiautomatic contouring and segmentation. Next, the model is refined based on the patient blood flow conditions, including viscosity and pressure conditions. Myocardial blood flow is proportional to myocardial mass, whereas microvascular resistance is inversely related to the size of the epicardial coronary arteries. The model eliminates the need for adenosine infusion as it also accounts for the reduction in microvascular resistance caused by adenosine [

52,

53]. The use of CT-FFR in the assessment of MB is less robust and guideline based than its use for CAD. Evidence regarding its use for the functional assessment of MB-related ischemia remains lacking, though data on its use in this context are emerging in the last few years and are discussed below. CT-FFR computation can be done in the systolic and diastolic phases. In addition, measurements may be taken at different points – most often proximal and distal to the MB/stenosis, from which ΔCT-FFR is derived as the difference between CT-FFR measurements taken at two points.

5. Challenges in Practical Implementation

Despite the numerous benefits, the integration of AI/ML into cardiac CT also presents several challenges that need to be addressed.

There is significant variability in diagnostic standards across different institutions, which can hinder the consistent application of AI technologies. Establishing a unified gold standard for AI-assisted cardiac CT imaging is crucial for widespread adoption and reliability. The success of AI in cardiac CT heavily relies on data sharing and the standardization of practices; missing information and varied data sources can degrade AI tools’ performance. Many are trained on narrow datasets, limiting their applicability across diverse populations and imaging systems. This highlights the need for collaborative efforts to create extensive, diverse data sets that can train robust AI algorithms and ensure their generalizability across various clinical settings. Overfitting, class imbalance, and lack of transparency in model decision-making further hinder clinical translation and bring about biases [

29].

Human oversight remains essential. Radiologists must proofread and validate AI-generated results to maintain high standards of care and ensure that AI technologies complement rather than replace clinical expertise.

The deployment of AI in healthcare must comply with ethical guidelines and regulatory standards to ensure patient safety and data privacy. In the world of data driven healthcare systems, privacy remains a critical challenge especially given the utilization of ML and DL systems in making predictions using user data. Ongoing collaboration between AI developers, clinicians, and regulatory bodies is necessary to navigate these complex landscapes effectively [

28].

Currently, there is a lack of data on the real-world application of these technologies and techniques with regards to the assessment of MB. We therefore conducted a systematic review of the literature, aiming to highlight currently available evidence and identify gaps in the literature and areas for future research.

5. Methods

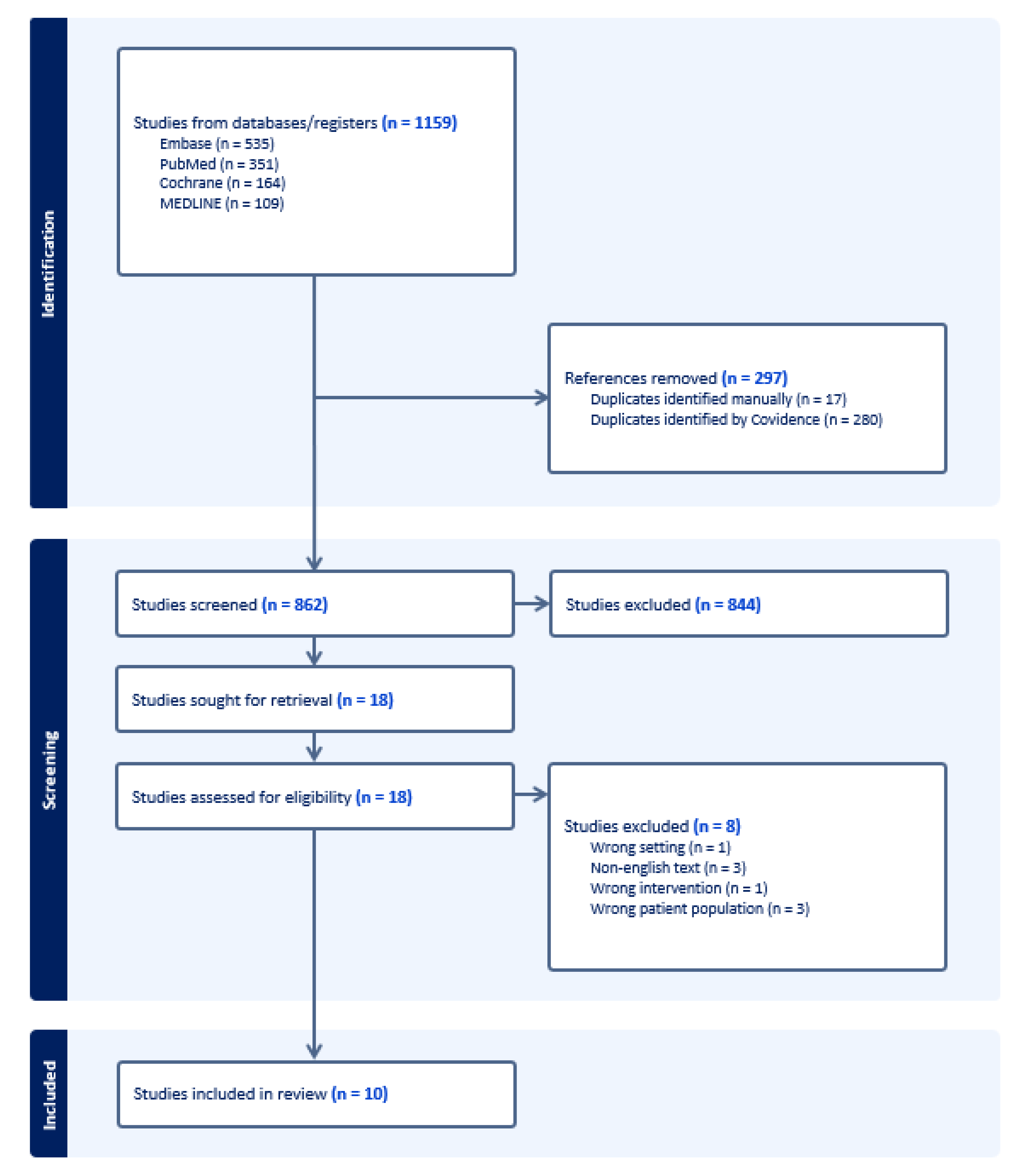

A comprehensive electronic search of the literature was conducted from inception to 17th April 2025 in the following databases: Embase, Medline, Pubmed, Cochrane. Keyword search was performed using the terms “Myocardial bridging”, “myocardial bridge”, “tomography”, “computerized tomography”, “computerized tomography angiography” as well as Boolean operators (AND, OR), resulting in a total of 1159 studies.

Semi-automated screening of the literature search results was performed by two authors using ‘Covidence’, an online systematic review tool in a two-phase process. The first phase consisted of title/abstract screening for potential eligible studies. The second phase consisted in retrieval and assessment of full-texts for eligible studies.

Studies were included if: 1) the population being studied was patients with myocardial bridging, 2) the study incorporated the use of any AI/ML techniques in its methodology, 3) they were English-language studies published in peer-reviewed journals.

Studies were excluded if: 1) they were published in a language other than English, 2) the population studied was not patients with myocardial bridging, 3) the study did not employ the use of AI/ML techniques.

Data from eligible studies were extracted using a data extraction template containing information on the study characteristics, participants, imaging modality and protocol, AI/ML technique used, and results. Automatically screened duplicates were then manually verified by the reviewers. A full diagram detailing the study selection process is shown in

Figure 1.

Given the high degree of heterogeneity between studies in terms of design, aim, methodology, study population, and the fact that none of the included studies are randomized control trials (with the majority being retrospective studies with the exception of one case report) our review reports on the findings of individual studies rather than analysis of results due to non-comparability between studies. We summarize the available literature on the topic to date and highlight areas for further research.

6. Results

A total of 10 studies were included in the review. These are summarized below (

Table 1).

7. Discussion

This systematic review synthesized evidence from 10 studies evaluating the application of AI in CCTA for the assessment of MB. Collectively, these highlight that AI-based techniques are logistically feasible in practical applications for this purpose. In particular, automation and reconstructive techniques were shown to be useful across several studies with authors reporting improvements in image quality as well as utility in optimizing certain aspects of workflow [

30,

31,

32,

33]. In addition, AI-driven techniques, particularly CT-FFR, can provide functional insight beyond static anatomical measurements. For the purpose of discussion, CT-FFR derived measurements will be summarized as a group (including systolic/diastolic CT-FFR and ΔCT-FFR measurements).

Positive findings included: significant association between CT-FFR values and MB with atherosclerosis compared to MB alone [

33]; significant association between LAD stenosis severity and CT-FFR values [

31,

34]; a role in prediction of plaque formation in MB[

31,

34]; correlation with iFFR in one study [

35]; correlation with symptoms of chest pain and angina in a second study [

36]; correlation between CT-FFR and certain anatomical features of MB (depth, length, distance from aorta) [

30,

37]; high negative predictive value (NPV) of CT-FFR [

35,

38] and high positive predictive value (PPV) in MB with >70% proximal stenosis [

35]; improved image quality [

32].

Table 2.

Summary of studies included in review.

Table 2.

Summary of studies included in review.

| Study |

Journal |

Country |

Study type |

Study aim |

Population |

Total participants |

Age |

% Male |

AI/ML technique |

Purpose of AI |

Findings |

|

Martens 2024 [36] |

European Heart Journal - Case Reports |

Belgium |

Case report |

To report on a case showing improvement in CT-FFR following treatment of MB |

A patient with LAD MB and abnormal CT-FFR which normalized after treatment with surgical unroofing of the MB |

1 |

55 |

100 |

ML-based CT-FFR (HeartFlow) |

Computation of CT-FFR |

Normalization of CT-FFR from 0.76 pre-surgery to 0.92 post-surgery |

|

Zhou 2019 [37] |

European Radiology |

China |

Retrospective case-control |

To evaluate the feasibility of CT-FFR derivation from CCTA in patients with MB, its relationship with MB anatomical features, and clinical relevance |

Patients with LAD MB on CCTA with no atherosclerosis as compared with controls |

161;

120 cases;

40 controls |

Cases: 52.4 ± 11

Controls: 54.3 ± 11.5 |

Cases: 68

Controls: 54 |

ML-based CT-FFR (cFFR v3.0.0, Siemens Healthineers) |

Computation of CT-FFR |

MBs are associated with abnormal CT-FFR values. MB length and systolic stenosis are the main contributors to abnormal CT-FFR values with a combination of the two showing moderate predictive performance. Patients with abnormal FFR were less likely to be asymptomatic and more likely to have typical anginal chest pain |

|

Zhou 2019 [34] |

JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging |

China |

Retrospective cohort |

To investigate the role of CT-FFR in predicting proximal plaque formation associated with MB in the LAD using ML approaches |

Patients with MB in the LAD and no atherosclerosis on baseline CCTA who underwent follow-up CCTA with a minimum interval of 3 months |

188 |

55 ± 6 |

68.6 |

ML-based CT-FFR (cFFR v3.0.0, Siemens Healthineers);

ML-based prediction model using LASSO algorithms |

Computation of CT-FFR; ML models for prediction of plaque formation |

CT-FFR distal to LAD MB and ΔCT-FFR significantly differed between patients with CT MB LAD who developed plaque and those who did not. ML algorithms further identified CT-FFR and ΔCT-FFR as the strongest predictors of plaque formation proximal to MB LAD |

|

Zhou 2019 [35] |

Canadian Journal of Cardiology |

China |

Retrospective cohort |

To study the diagnostic performance of ML-based CT-FFR to detect functional ischemia in MB with iFFR as the reference standard |

Patients who underwent CCTA for the evaluation of suspected or known CAD and were found to have LAD MB, who then underwent ICA within 60 days of CCTA |

104 |

61.2 ± 9.1 |

72.1 |

ML-based CT-FFR (cFFR v3.2.0, Siemens Healthineers) |

Automatic generation of centreline and luminal contours of coronary arteries; Computation of CT-FFR |

CT-FFR has high diagnostic performance for functional ischemia in vessels with MB and concomitant proximal atherosclerotic disease compared with iFFR, regardless of length and depth of MB, with a low PPV for lesions of <70% stenosis |

|

Jubran 2020 [39] |

Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging |

United States |

Retrospective cohort |

To compare CT-FFR, dobutamine-stress dFFR, iFFR and IVUS in assessing the hemodynamic significance of MB |

Patients with angina who had been found to have an MB in the LAD with ≤50% coronary artery stenosis by ICA and had undergone CCTA |

CT-FFR: 49

dFFR: 43

iFFR: 28

IVUS: 46 |

47.5 ± 13.7 |

39 |

ML-based CT-FFR (cFFR v3.1.2, Siemens Healthineers) |

Computation of CT-FFR |

CT-FFR values measured in LAD MB were lower than arteries without MB. CT-FFR values did not correlate with dobutamine-stress dFFR, iFFR or LAD systolic compression on IVUS. CT-FFR values were higher than dFFR and lower than iFFR. There was non-concordance between CT-FFR and dFFR, iFFR or degree of systolic compression measured by IVUS |

|

Yu 2021 [38] |

Korean Journal of Radiology |

China |

Cross sectional |

To investigate the diagnostic performance of CT-FFR for MB-related ischemia using dynamic CT-MPI as a reference standard |

Symptomatic patients with LAD MB and no obstructive stenosis on CCTA who also underwent CT-MPI |

75 |

62.7 ± 13.2 |

64 |

ML-based CT-FFR (cFFR; version 3.0, Siemens Healthineers) |

Computation of CT-FFR |

ΔCT-FFRsystolic shows high sensitivity and NPV and reliably excludes MB-ischemia. All CT-FFR measurements had low PPV and other methodologies are needed to confirm positive CT-FFR results |

|

Zhang 2024 [32] |

Clinical Radiology |

China |

Retrospective Observational Comparative Study (Within-Subject) |

To determine the effect of second-generation motion correction (MC2) on image quality and measurement reproducibility of CCTA images in patients with MB and mural coronary artery (MB-MCA) compared to standard (STD) images without motion correction and with first-generation motion correction (MC1) |

Patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease who underwent CCTA and had MB-MCA in the LAD |

66 |

62 ± 11 |

45 |

Deep learning image reconstruction algorithm (DLIR, GE Healthcare); First generation motion correction algorithm (MC1, GE Healthcare); Second generation motion correction algorithm (MC2, GE Healthcare) |

Image reconstruction and motion correction |

MC2 reduced motion artefacts and resulted in significant improvements of image quality and diagnostic confidence and measurement reproducibility for both MB and MCA in systolic and diastolic phases |

|

Zhang 2024 [33] |

Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging |

China |

Retrospective case-control |

To quantitatively investigate the effect of MB in the LAD on CT-FFR |

Patients with confirmed LAD MB on CCTA with or without atherosclerosis in the LAD as compared with controls |

404;

300 cases;

104 controls |

Cases: 54 ± 6

Controls: 54 ± 7 |

Cases: 56

Controls: 24 |

ML-based CT-FFR (Shukun, ct-FFR, V1.17) |

Automatic extraction of coronary artery tree; automatic segmentation, reconstruction and diagnosis of coronary artery stenosis;

Computation of CT-FFR |

No differences in CT-FFR values between systolic and diastolic phases. MB (with or without atherosclerosis) is associated with greater ΔCT-FFR and lower CT-FFR compared with controls without MB.

CT-FFR is significantly lower in MB with atherosclerosis than in MB without atherosclerosis.

In MB with atherosclerosis, LAD stenosis severity is an independent risk factor significantly affecting CT-FFR values and abnormal CT-FFR (<0.80) is associated with more severe LAD stenosis.

There was no significant difference detected in terms of clinical or anatomical features between the abnormal and normal CT-FFR groups |

|

Chen 2024 [31] |

European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging |

China |

Retrospective cohort and validation study |

To develop and validate CCTA based radiomics models in predicting proximal plaque development in LAD MB |

Patients with MB and no atherosclerotic plaque proximal to the MB segment on baseline CCTA |

295 |

55 ± 10 |

66 |

ML models |

Predictive modelling and analysis |

The proximal MB cross-sectional radiomics model (pMB CS) is able to predict proximal atherosclerotic plaque development associated with LAD MB in an external validation set (AUC 0.75; P <0.001) and can be integrated with a clinical model to further improve performance (AUC 0.76; P <0.001) |

|

Sun 2024 [30] |

Clinical Imaging |

China |

Cross sectional |

To compare the performance between CT-FFR and ΔCT-FFR in patients with deep LAD MB and explore predictors of discordance between the two measurements |

Patients with deep LAD MB on CCTA and <50% stenosis of the LAD and/or left main stem |

175 |

60 ± 7 |

71.4 |

Deep learning image reconstruction (TrueFidelity, GE Healthcare);

ML-based CT-FFR (uAI Portal; United Imaging Intelligence) |

Image reconstruction; Automatic labelling of plaque and MB;

Computation of CT-FFR |

30.9% of patients had discordance of CT-FFR and ΔCT-FFR with 94.4% of patients leaning towards CT-FFR positivity with a negative ΔCT-FFR. Proximal atherosclerosis and distance from the MB to the aorta were independent risk factors for discordance. Anatomic features (length and depth) of the MB were correlated with ΔCT-FFR rather than CT-FFR, suggesting ΔCT-FFR as a more specific tool for MB evaluation |

Eight studies utilized CT-FFR, with studies focusing on various aspects of its use: 1) assessment of functional ischemia in MB; 2) prediction of proximal atherosclerotic plaque formation; 3) association with certain anatomical characteristics of MB; 4) correlation with symptoms; 5) correlation with a reference measurement (CT-MPI, invasive assessment methods); 6) comparison of different CT-FFR derived measurements.

However, there were conflicting findings across several studies (despite variations in design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and methods) and several of the above-mentioned findings were not verified in other studies.

For example, Zhou et al. [

35] reported high concordance between CT-FFR and iFFR in patients with LAD MB and atherosclerosis, while Jubran et al. [

39] reported that CT-FFR values did not correlate with iFFR values in their study. It is important to note that in these two retrospective studies, the study design and study population differed. Jubran et al. selected patients with ≤50% coronary artery stenosis on ICA while Zhou et al. selected patients who had undergone CCTA and subsequently underwent ICA, irrespective of the degree of coronary artery stenosis identified. Moreover, Jubran et al. employed a less rigorous study design without identification of a clear cohort, and the number of patients who underwent CT-FFR and those who underwent iFFR was not 1:1 (49 patients underwent CT-FFR with only 28 patients undergoing iFFR).

Two studies attempted to correlate CT-FFR data with clinical data in terms of symptoms of chest tightness/pain and angina with differing findings. Zhou et al. [

37] found that patients with abnormal CT-FFR were significantly more likely to have symptoms of typical anginal chest pain, and less likely to be asymptomatic. Zhang et al. [

33] found that there was no significant difference in symptoms between the normal and abnormal CT-FFR groups, though this finding approached significance with a P-value of 0.05. These studies are both case-control studies, however Zhang et al. included MB patients with and without atherosclerosis, while Zhou et al. included only patients without atherosclerosis.

Two studies reported on the diagnostic properties of CT-FFR for MB-related ischemia. The first study by Zhou et al. [

35] used iFFR as the reference standard and reported a high PPV for CT-FFR in detecting ischemia in MB lesions with >70% proximal LAD stenosis on ICA, with low PPV for lesser degrees of stenosis. Despite this, CT-FFR maintained high sensitivity and NPV regardless of severity of stenosis, highlighting its use as an effective rule-out test for MB-related ischemia. In another study by Yu et al. [

38], CT-FFR was compared against a reference standard of CT-MPI in patients with MB and no obstructive stenosis on CCTA. They found that CT-FFR had a high NPV but low PPV for MB-related ischemia, suggesting it as an effective rule-out test, with positive CT-FFR results requiring further evaluation by alternate modalities.

Moreover, while two studies showed a correlation between CT-FFR values and certain anatomical characteristics of MB [

30,

37] (suggesting that certain characteristics may in turn be more correlated to functionally significant MB lesions) – Zhang et al. [

33] found no significant difference in anatomical features in patients with normal and abnormal CT-FFR values. Again, these studies had different populations with the former two including patients with no atherosclerosis and <50% coronary stenosis respectively, while the latter included patients with and without atherosclerosis. In addition, a correlation between abnormal CT-FFR values and anatomical characteristics of MB alone does not imply an association between these characteristics and functional significance of the MB, as CT-FFR has not been established as a validated tool for confirming MB-related ischemia.

Of note, the study by Jubran et al. was the only study that included a comparison with dFFR, which, as previously described, has been considered the gold-standard reference specifically for the assessment of MB-related ischemia.

Beyond functional assessment, ML and radiomics models demonstrated predictive value for future plaque development, particularly in MB segments associated with altered hemodynamics. These findings suggest that AI may not only detect current disease but also anticipate downstream atherosclerotic risk.

Significant limitations across studies included retrospective study designs, single-center designs, methodological heterogeneity across studies, small sample sizes, varying reference standards or the lack of comparison to recognized reference standards for assessing ischemia or comparison to non-gold standard reference, the use of different CT-FFR techniques, the variable exclusion/inclusion criteria and especially the variable inclusion of patients with atherosclerotic disease across studies, the lack of control groups in some studies, the lack of correlation with clinical data in most studies and the lack of adjustment for confounding factors.

This review also has limitations. The search strategy was limited to English-language publications, and we did identify three Chinese-language publications during the search that were excluded. Moreover, the small number of eligible studies and their heterogeneity precluded quantitative synthesis and meta-analysis. Publication bias also cannot be excluded, and the findings may overrepresent positive results due to selective reporting.

Future research should focus on the prospective validation of AI-based tools in larger, multicenter cohorts using standardized imaging protocols and clinical endpoints. Integrating AI-derived functional parameters with clinical data, stress testing, or perfusion imaging may improve diagnostic accuracy and facilitate personalized management strategies. Furthermore, the incorporation of explainable AI may help bridge the interpretability gap, improving clinician trust and supporting regulatory adoption.

8. Conclusions

In conclusion, AI-enhanced cardiac CT, particularly through CT-FFR, shows promise in improving the assessment, characterization, and risk stratification of MB. Tools for the accurate detection of functionally relevant MB lesions are increasingly necessary in order to allow radiologists and clinicians to navigate the exponentially growing volume of highly accurate diagnostic CCTA studies and subsequent increase in detection of MB. While further validation is necessary, these technologies have the potential to transform current imaging paradigms by offering non-invasive, reproducible, and functionally meaningful assessments that can guide patient care more effectively.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design, A.A.S., F.R., M.B. and L.S.; literature review, A.A.S. and F.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.S., L.D.V., D.A., E.B.O., V.I., M.O.A.D. and G.S.; writing—review and editing, A.A.S., F.R., M.B. and L.S.; supervision, M.B. and L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

Full data extracted from the articles included in the literature review are made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rogers, I. S., Tremmel, J. A. & Schnittger, I. Myocardial bridges: Overview of diagnosis and management. Congenit Heart Dis 12, 619–623 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Poláček, P. Relation of myocardial bridges and loops on the coronary arteries to coronary occlusions. Am Heart J 61, 44–52 (1961). [CrossRef]

- Ishii, T., Asuwa, N., Masuda, S. & Ishikawa, Y. The effects of a myocardial bridge on coronary atherosclerosis and ischaemia. J Pathol 185, 4–9 (1998).

- Möhlenkamp, S., Hort, W., Ge, J. & Erbel, R. Update on myocardial bridging. Circulation 106, 2616–2622 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Kawawa, Y. et al. Detection of myocardial bridge and evaluation of its anatomical properties by coronary multislice spiral computed tomography. Eur J Radiol 61, 130–138 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Rubinshtein, R. et al. Long-term prognosis and outcome in patients with a chest pain syndrome and myocardial bridging: a 64-slice coronary computed tomography angiography study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 14, 579–585 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Feld, H. et al. Exercise-induced ventricular tachycardia in association with a myocardial bridge. Chest 99, 1295–1296 (1991). [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, R., Rajani, R., Ishikawa, Y., Ishii, T. & Berman, D. S. Myocardial bridging on coronary CTA: an innocent bystander or a culprit in myocardial infarction? J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 6, 3–13 (2012).

- Ge, J. et al. Comparison of intravascular ultrasound and angiography in the assessment of myocardial bridging. Circulation 89, 1725–1732 (1994). [CrossRef]

- Patricio, L. et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. Revista Portuguesa de Cardiologia 28, 229–230 (2009).

- Zimmermann, F. M. et al. Deferral vs. performance of percutaneous coronary intervention of functionally non-significant coronary stenosis: 15-year follow-up of the DEFER trial. Eur Heart J 36, 3182–3188 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Escaned, J. et al. Importance of diastolic fractional flow reserve and dobutamine challenge in physiologic assessment of myocardial bridging. J Am Coll Cardiol 42, 226–233 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Angelini, P., Uribe, C. & Raghuram, A. Coronary Myocardial Bridge Updates: Anatomy, Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options. Tex Heart Inst J 52, (2025). [CrossRef]

- Ekeke, C. N., Noble, S., Mazzaferri, E. & Crestanello, J. A. Myocardial bridging over the left anterior descending: Myotomy, bypass, or both? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 149, e57–e58 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Tandar, A., Whisenant, B. K. & Michaels, A. D. Stent fracture following stenting of a myocardial bridge: Report of two cases. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 71, 191–196 (2008).

- Kunamneni, P. B. et al. Outcome of intracoronary stenting after failed maximal medical therapy in patients with symptomatic myocardial bridge. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 71, 185–190 (2008).

- Bamberg, F. et al. Dynamic myocardial CT perfusion imaging for evaluation of myocardial ischemia as determined by MR imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 7, 267–277 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ho, K. T., Chua, K. C., Klotz, E. & Panknin, C. Stress and rest dynamic myocardial perfusion imaging by evaluation of complete time-attenuation curves with dual-source CT. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 3, 811–820 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. et al. Stress Myocardial Blood Flow Ratio by Dynamic CT Perfusion Identifies Hemodynamically Significant CAD. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 13, 966–976 (2020).

- Li, Y., Dai, X., Lu, Z., Shen, C. & Zhang, J. Diagnostic performance of quantitative, semi-quantitative, and visual analysis of dynamic CT myocardial perfusion imaging: a validation study with invasive fractional flow reserve. Eur Radiol 31, 525–534 (2021).

- Schicchi, N. et al. Stress-rest dynamic-CT myocardial perfusion imaging in the management of myocardial bridging: A ‘one-stop shop’ exam. J Cardiol Cases 28, 229–232 (2023).

- Williams, M. C. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for cardiovascular computed tomography (CCT): A white paper of the society of cardiovascular computed tomography (SCCT). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 18, 519–532 (2024).

- Slart, R. H. J. A. et al. Position paper of the EACVI and EANM on artificial intelligence applications in multimodality cardiovascular imaging using SPECT/CT, PET/CT, and cardiac CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 48, 1399–1413 (2021).

- Sandeep, B. et al. Feasibility of artificial intelligence its current status, clinical applications, and future direction in cardiovascular disease. Curr Probl Cardiol 49, 102349 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Liao, J., Huang, L., Qu, M., Chen, B. & Wang, G. Artificial Intelligence in Coronary CT Angiography: Current Status and Future Prospects. Front Cardiovasc Med 9, 896366 (2022).

- Lopez-Jimenez, F. et al. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiology: Present and Future. Mayo Clin Proc 95, 1015–1039 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Krittanawong, C., Zhang, H. J., Wang, Z., Aydar, M. & Kitai, T. Artificial Intelligence in Precision Cardiovascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol 69, 2657–2664 (2017).

- Tolu-Akinnawo, O. Z., Ezekwueme, F., Omolayo, O., Batheja, S. & Awoyemi, T. Advancements in Artificial Intelligence in Noninvasive Cardiac Imaging: A Comprehensive Review. Clin Cardiol 48, e70087 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kwan, A. C., Salto, G., Cheng, S. & Ouyang, D. Artificial Intelligence in Computer Vision: Cardiac MRI and Multimodality Imaging Segmentation. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 15, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Tang, Z., Li, B., Firmin, D. & Yang, G. Recent Advances in Fibrosis and Scar Segmentation From Cardiac MRI: A State-of-the-Art Review and Future Perspectives. Front Physiol 12, (2021).

- Alnasser, T. N. et al. Advancements in cardiac structures segmentation: a comprehensive systematic review of deep learning in CT imaging. Front Cardiovasc Med 11, (2024).

- Liang, J. et al. Second-generation motion correction algorithm improves diagnostic accuracy of single-beat coronary CT angiography in patients with increased heart rate. Eur Radiol 29, 4215–4227 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. et al. Further improving image quality of cardiovascular computed tomography angiography for children with high heart rates using second-generation motion correction algorithm. J Comput Assist Tomogr 44, 790–795 (2020).

- Joshi, M. et al. Current and Future Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Cardiac CT. Curr Cardiol Rep 25, 109–117 (2023).

- Sun, Q. et al. Predictors of discordance between CT-derived fractional flow reserve (CT-FFR) and △CT-FFR in deep coronary myocardial bridging. Clin Imaging 114, 110264 (2024).

- Zhang, D. et al. Quantitative computed tomography angiography evaluation of the coronary fractional flow reserve in patients with left anterior descending artery myocardial bridging. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 44, 251–259 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Liu, Z., Hong, N. & Chen, L. Effect of a second-generation motion correction algorithm on image quality and measurement reproducibility of coronary CT angiography in patients with a myocardial bridge and mural coronary artery. Clin Radiol 79, e462–e467 (2024).

- Zhou, F. et al. Diagnostic Performance of Machine Learning Based CT-FFR in Detecting Ischemia in Myocardial Bridging and Concomitant Proximal Atherosclerotic Disease. Can J Cardiol 35, 1523–1533 (2019).

- Gijsen, F. et al. Expert recommendations on the assessment of wall shear stress in human coronary arteries: existing methodologies, technical considerations, and clinical applications. Eur Heart J 40, 3421–3433 (2019).

- Stone, P. H. et al. Role of Low Endothelial Shear Stress and Plaque Characteristics in the Prediction of Nonculprit Major Adverse Cardiac Events. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 11, 462–471 (2018).

- Kumar, A. et al. High Coronary Shear Stress in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease Predicts Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 72, 1926–1935 (2018).

- Candreva, A. et al. Current and Future Applications of Computational Fluid Dynamics in Coronary Artery Disease. Rev Cardiovasc Med 23, (2022).

- Wojtas, K., Kozłowski, M., Orciuch, W. & Makowski, Ł. Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations of Mitral Paravalvular Leaks in Human Heart. Materials 14, 7354 (2021).

- Fezzi, S. et al. Integrated Assessment of Computational Coronary Physiology From a Single Angiographic View in Patients Undergoing TAVI. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 16, E013185 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Javadzadegan, A. et al. Development of a Computational Fluid Dynamics Model for Myocardial Bridging. J Biomech Eng 140, (2018).

- Sharma, P. et al. A framework for personalization of coronary flow computations during rest and hyperemia. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2012, 6665–6668 (2012).

- Gulati, M. et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/ SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 144, E368–E454 (2021).

- Bittl, J. A. et al. Putting the 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization Into Practice. JACC Case Rep 4, 31–35 (2022).

- Neumann, F.-J. & Sousa-Uva, M. ‘Ten commandments’ for the 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on Myocardial Revascularization. Eur Heart J 40, 79–80 (2019).

- Yang, S. et al. Long-term prognostic implications of CT angiography-derived fractional flow reserve: Results from the DISCOVER-FLOW study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 18, 251–258 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Nørgaard, B. L. et al. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography in suspected coronary artery disease: the NXT trial (Analysis of Coronary Blood Flow Using CT Angiography: Next Steps). J Am Coll Cardiol 63, 1145–1155 (2014).

- Rajiah, P., Cummings, K. W., Williamson, E. & Young, P. M. CT Fractional Flow Reserve: A Practical Guide to Application, Interpretation, and Problem Solving. RadioGraphics 42, 340–358 (2022).

- Tesche, C. et al. Coronary CT Angiography–derived Fractional Flow Reserve. Radiology 285, 17–33 (2017).

- Seetharam, K., Brito, D., Farjo, P. D. & Sengupta, P. P. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Cardiovascular Imaging: State of the Art Review. Front Cardiovasc Med 7, 618849 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Martens, B., Michiels, V., J.-F., A. & Cosyns, B. Normalization of FFR<ovid:inf>CT</ovid:inf> after surgical unroofing of a myocardial bridge: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 8, ytae005- (2024).

- Zhou, F. et al. Fractional flow reserve derived from CCTA may have a prognostic role in myocardial bridging. Eur Radiol 29, 3017–3026 (2019).

- Zhou, F. et al. Machine Learning Using CT-FFR Predicts Proximal Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation Associated With LAD Myocardial Bridging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 12, 1591–1593 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Jubran, A. et al. Computed Tomographic Angiography-Based Fractional Flow Reserve Compared With Catheter-Based Dobutamine-Stress Diastolic Fractional Flow Reserve in Symptomatic Patients With a Myocardial Bridge and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 13, e009576- (2020).

- Yu, Y., Yu, L., Dai, X. & Zhang, J. CT Fractional Flow Reserve for the Diagnosis of Myocardial Bridging-Related Ischemia: A Study Using Dynamic CT Myocardial Perfusion Imaging as a Reference Standard. Korean J Radiol 22, 1964–1973 (2021).

- Chen, Y. C. et al. Coronary CTA-based vascular radiomics predicts atherosclerosis development proximal to LAD myocardial bridging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 25, 1462–1471 (2024). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).