Experimental Test of Hypothesis

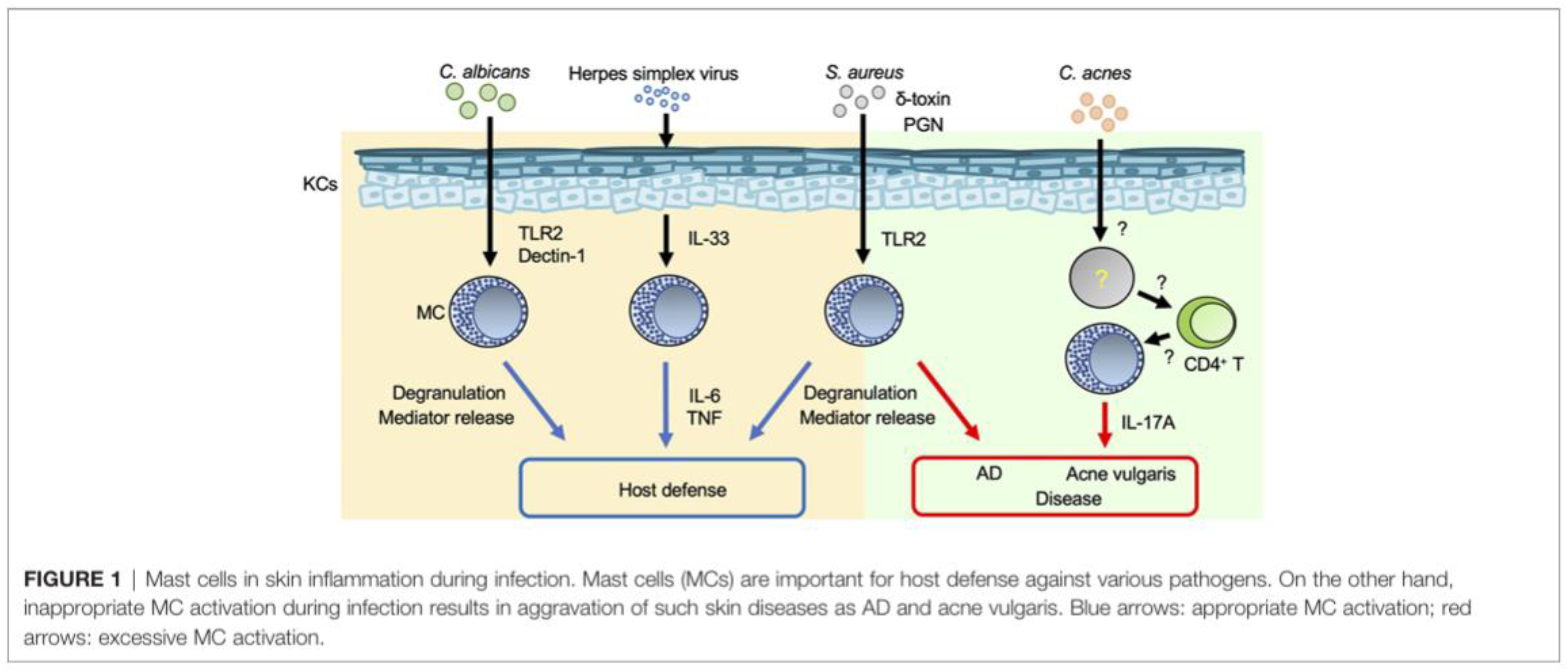

Recently, this hypothesis was tested in practice. Japanese dermatologist Dr. Yasuhiro Horiuchi has tested a combination of oral mast cell stabilizer tranilast with oral antibiotic minocycline for

acne vulgaris treatment. In the paper “Tranilast and Minocycline Combination for Intractable Severe Acne and Prevention of Postacne Scarring: A Case Series” published in 2022 Dr. Horiuchi presented data of a small study with twelve severe acne patients (7 males and 5 females) of grade 3 or 4 (

Table 1) without treatment history at the start of the combination therapy that include 100 mg/day minocycline and 200 mg/day tranilast for up to 4–5 months depending on each patient’s severity [

29]. All participants healed almost all their acne lesions without newly developed hypertrophic scars. Severe acne patients (grade 4) took over 5 months to reach grade 0, but patients with grade 3 acne showed recovery after approximately 3–4 months of the combination therapy (

Table 1, Figure 5 from [

29,

30]).

Table 1.

Patients and progress of the combination Tranilast/Minocycline therapy (reprinted from [

29]).

Table 1.

Patients and progress of the combination Tranilast/Minocycline therapy (reprinted from [

29]).

Based on these fundings, the author has concluded that more attention should be paid to the involvement and control of mast cells in the development of scarring in severe acne and the blocking of mast cell function can serve as an effective and satisfactory therapeutic strategy [

29]. “The daily combined use of tranilast with antibiotics can treat severe acne and prevents the formation of new scars,” the author added. In comparison, a single treatment with oral and/or externally administered antibiotics can cause atrophic scars during severe acne.

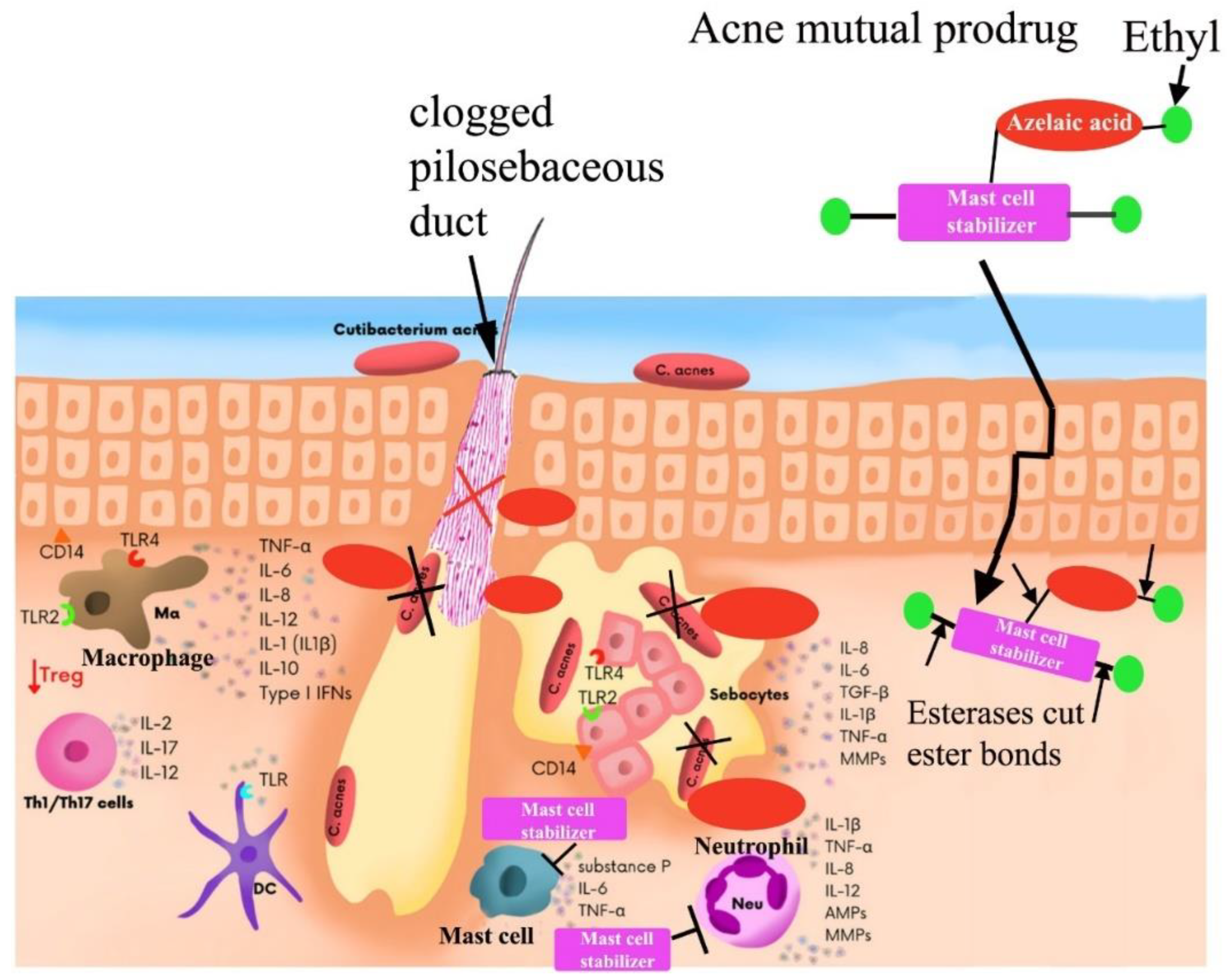

Figure 5.

An illustration of combination therapy treatment (top). Bottom - severe acne lesions diagram: causative acne bacteria, and mast cells related to severe inflammation and acne scar development [

30].

Figure 5.

An illustration of combination therapy treatment (top). Bottom - severe acne lesions diagram: causative acne bacteria, and mast cells related to severe inflammation and acne scar development [

30].

Tranilast is a daily medical agent that’s been approved in Japan for more than 30 years. Tranilast (INN, brand name Rizaben) is an antiallergic drug. It was developed by Kissei Pharmaceuticals and was approved in 1982 for use in Japan and South Korea for bronchial asthma. Indications for keloid and hypertrophic scar were added in the 1980s. When given systemically, tranilast appears to cause liver damage; in a large well-conducted clinical trial it caused elevated transaminases three times the upper limit of normal in 11 percent of patients, as well as anemia, kidney failure, rash, and problems urinating. Given systemically it inhibits blood formation, causing leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. Because of these severe adverse effects, in 2016 the FDA proposed that tranilast be excluded from the list of active pharmaceutical ingredients that compounding pharmacies in the US could formulate with a prescription [

31]. While the FDA has serious concerns about the safety of tranilast when administered orally, the Agency has insufficient information about the systemic absorption of topical tranilast formulations to determine whether topical administration of the drug product would present the same safety concerns. Given the lack of information available about the safety and efficacy of topical tranilast, and safety concerns related to the oral use of this product, the proposed rule would not place tranilast on the 503A Bulks List [

31].

Oral antibiotics are generally more effective than their topical variety. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, nearly 20 million Americans suffer from severe acne where the preferred treatment was found to be oral antibiotics. However, oral antibiotics just control but do not cure acne. They work by killing the bacteria (P. acnes) that is responsible for acne. In addition, antibiotics possess anti-inflammatory properties. Thus, antibiotics reduce the inflammation that occurs in acne lesions. Oral antibiotics are usually taken twice daily. Many acne patients need to take oral antibiotics for many months or even years before they notice significant acne improvement. Since antibiotics have been used for many years in the treatment of acne, increasing bacterial resistance to the antibiotics means that the antibiotics are not as effective in the treatment of acne as they once were.

Dermatologists are in a unique position to respond to the rising threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria: dermatologists make up just 1% of all physicians but are responsible for 4.9% of antibiotic prescriptions [

32]. Dermatologists primarily prescribe antibiotics for the treatment of severe acne, and this prescribing practice may have contributed to the rise of antibiotic resistance. As with the topical antibiotics, there is emerging resistance by bacteria to the erythromycin class of antibiotics and other families of antibiotics including doxycycline and minocycline. In addition, there are side effects associated with the oral antibiotics, including upset stomach, dizziness, headache, increased sun sensitivity, yeast infections, rash and hives. There have also been reports of minocycline-induced lupus-like syndrome. Another word of caution: the use of oral antibiotics by women who are on birth control pills could make the pill less effective, subjecting women to the risk of unwanted pregnancy. In addition, the increased exposure to antibiotics increases the risk of antibiotic-associated dysbiosis, which is associated with reduced diversity of gut microbial species and abundance of certain taxa, disruption of host immunity, and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant microbes. Antibiotic usage during young childhood development can lead to adverse gut issues (dysbiosis) in adulthood [

33]. The gut microbiome is altered by antibiotics and frequent usage of antibiotics linked to future gut disease such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), ulcerative colitis, obesity, etc. The intestinal immune system is directly influenced by the gut microbiome and it can be hard to recover the gut microbiome balance if it is damaged through antibiotics. The use of minocycline in acne vulgaris has been associated with skin and gut dysbiosis [

34].

Oral minocycline is approved by the FDA for moderate-to-severe acne. However, tranilast (in both oral and topical forms) was excluded by the FDA from the list of active pharmaceutical ingredients that compounding pharmacies in the US could formulate with a prescription [

31]. Thus, the combination therapy of oral mast cell stabilizer tranilast and oral antibiotic minocycline is not even an option for acne patients in USA. This is completely excluded a possibility to test a combination therapy of oral tranilast/minocycline for 20 million Americans suffering from moderate-to-severe acne.

It is obvious that oral delivery of compounds that work excursively within acne lesions (in epidermis and dermis layers of human skin) is not the best approach. It is very unlikely that 100 mg per day of minocycline dosed orally will create a therapeutically significant concentration of antibiotic in interstitial fluid around cells that form hair follicles and sebaceous glands. It is known that dermatologists expect acne patients to use oral antibiotics for at least three to four months before they notice significant acne improvement. The recommended course will, however, depend on the medication used and acne severity. Some people may take an antibiotic for much longer, with one study of amoxicillin reporting an average duration of 37 weeks [

35]. Therefore, an oral route of antibiotic and FDA approved mast cell stabilizer for delivery to epidermis/dermis layers of skin does not look like a feasible strategy to treat

acne vulgaris. Direct topical delivery of both compounds would be a better option.

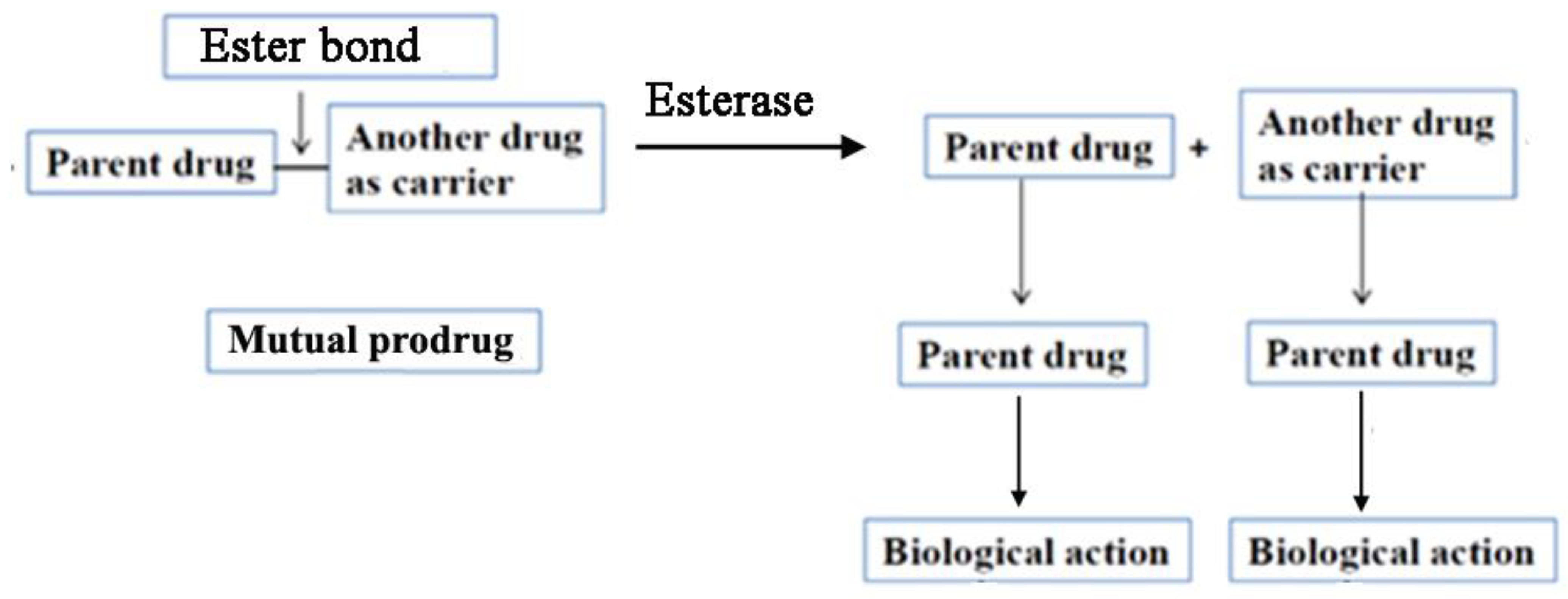

Mutual Prodrug Concept for Topical Delivery

We have developed a concept of mutual prodrugs for different types of skin inflammatory diseases. The prodrug and mutual prodrug approaches are usually used to resolve the undesirable properties and particularly physicochemical problems accompanied by active drug. For the drugs that are applied topically to the skin a lipophilicity is a very important parameter that governs absorption of drugs through the skin. Therefore, skin penetrability can be significantly improved by altering drug lipophilicity. In general, mutual prodrugs consist of two pharmacologically active drugs joined with each other via covalent bond (ester, amide or other) (

Figure 6). They are usually taken together with aims such as: 1) to mask the side effects of active drugs; 2) change drug physicochemical properties (for example to increase drug lipophilicity, or vice versa to increase drug water solubility); 3) to provide a synergistic action when both parental drugs are liberated simultaneously.

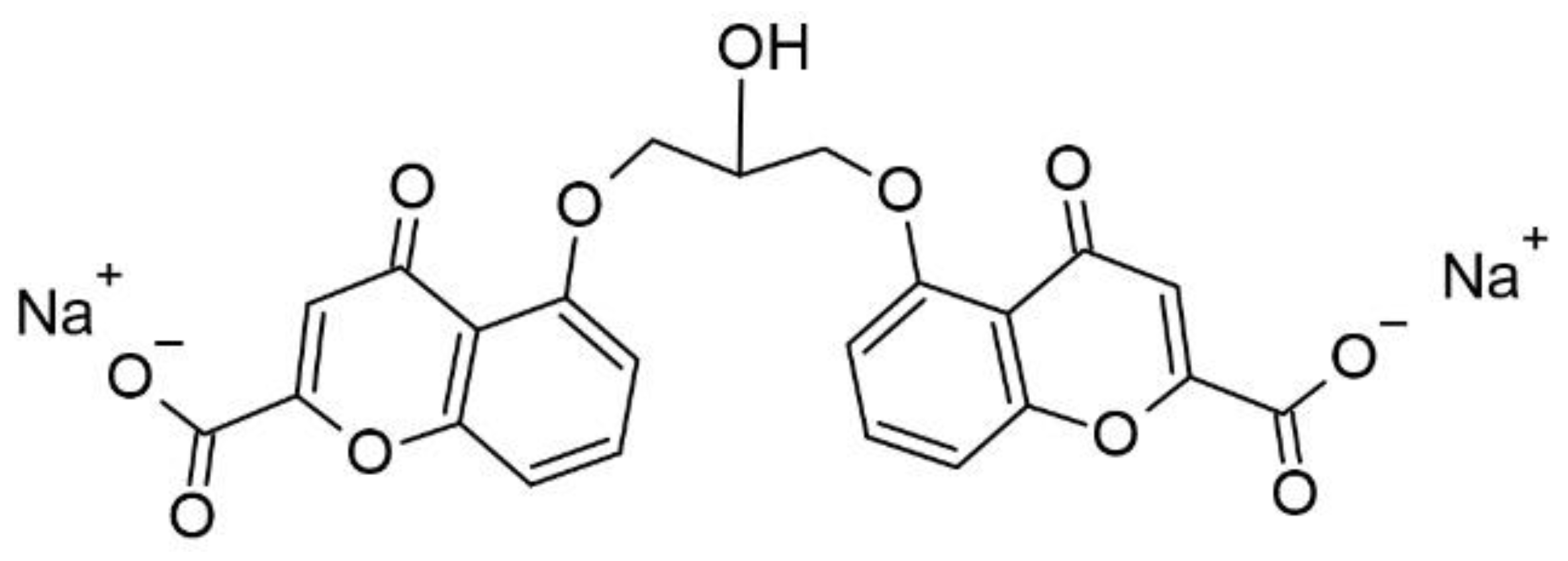

Cromolyn sodium (

Figure 7), when given orally, is poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract because this compound is negatively charged, water soluble and hydrophilic. Log of Cromoglycate Sodium is -3 (measured with pH = 6.5 buffer and 1-octanol) [

36]). Therefore, it is a practically membrane-impermeable active pharmaceutical ingredient. It explains the very low oral bioavailability of cromolyn sodium that is 0.5 to 2%, with a half-life of 80 to 90 minutes. Most of the drug (98%) is excreted in the feces unabsorbed, with the remainder excreted in the urine. Similarly, less than 0.07% of administered cromolyn sodium is absorbed from ophthalmic solution or drops. However, the effect of absorbed cromolyn sodium on mast cells lasts for approximately 6 hours following administration [

37].

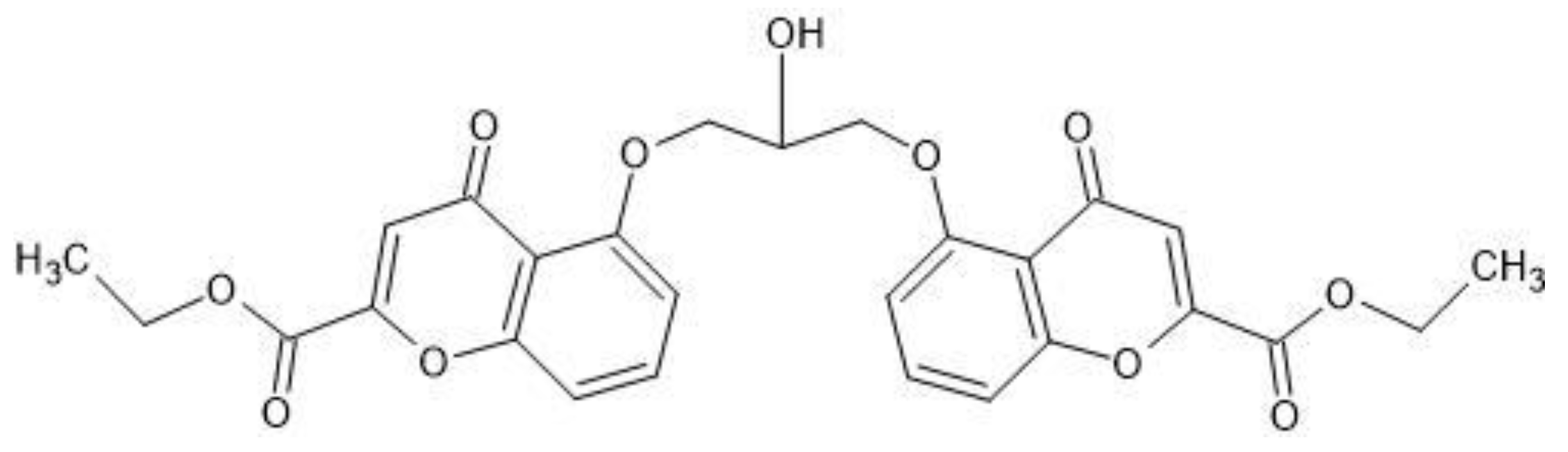

Diethyl cromoglycate is a prodrug of cromolyn sodium. In this compound both carboxyl groups of cromolyn sodium are masked via esterification reaction with ethanol (

Figure 8). Diethyl cromoglycate has partition coefficient = 60.3 (Log P = 1.78) [

36]. It is a lipophilic compound and therefore its water solubility is very poor (0.052 mg/ml) in comparison with water solubility of cromolyn sodium (195.3 mg/ml) [

36]. Diethyl cromoglicate was never approved by FDA for any indications.

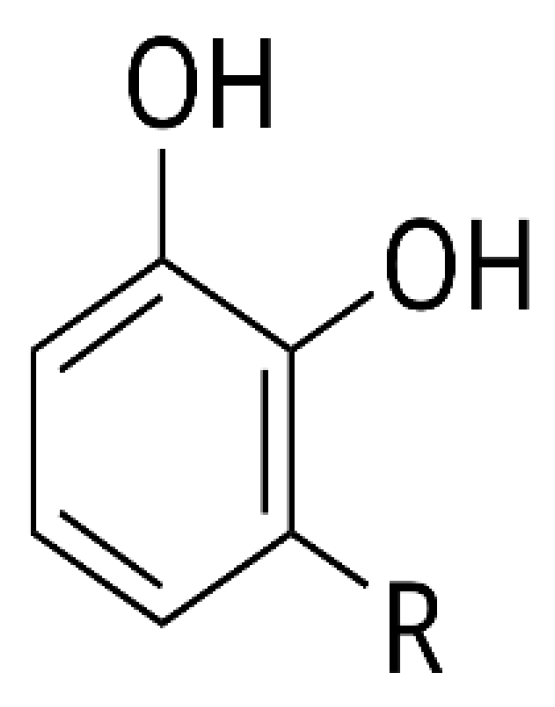

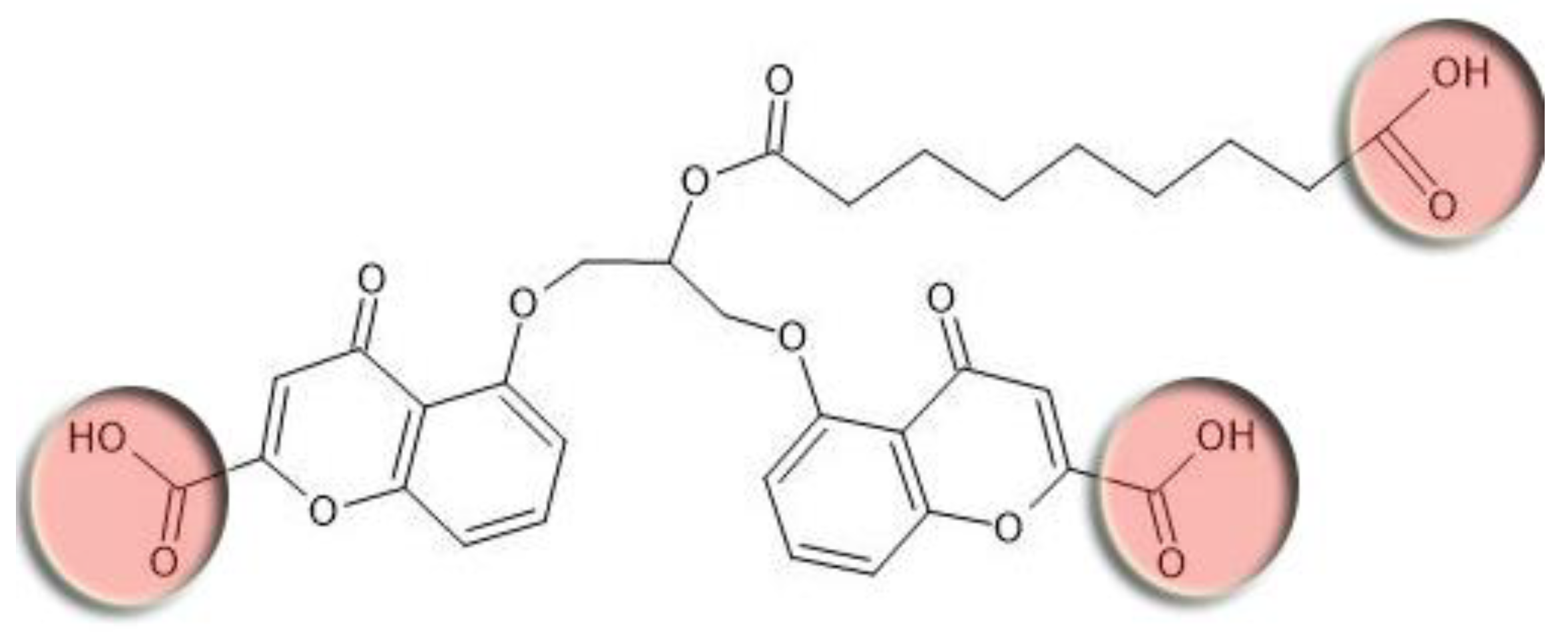

Based on these new data that revealed key role of mast cells in acne vulgaris pathophysiology, Samdolite Pharmaceuticals Inc. has proposed a principally new approach: to deliver safe, effective and FDA approved mast cell stabilizer cromoglicic acid in from of mutual prodrug directly into the acne lesions (bypassing an oral route). At pH 6-8 cromoglicic acid forms the salt cromolyn sodium that has very low skin penetrability. To make it skin permeable, we have converted cromoglicic acid into a lipophilic mutual prodrug via covalent linking of cromoglicic acid with an azelaic acid (

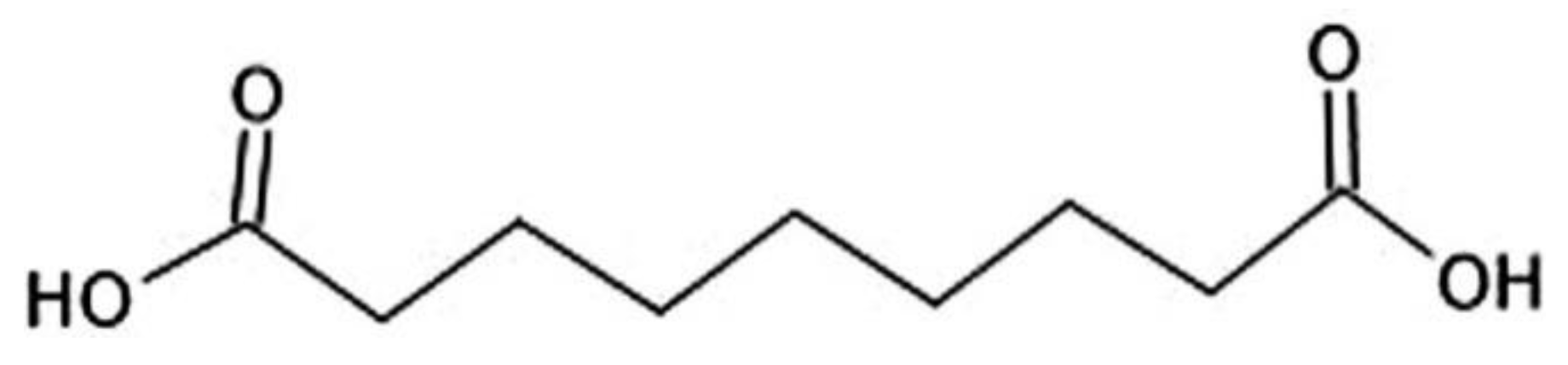

Figure 9). An azelaic acid has Log P = 1.136 at pH 4.6 i.e. it is a lipophilic substance. But at the same time azelaic acid has two ionizable carboxyl groups (

Figure 8) that decrease its lipophilicity and skin penetrability (at pH 7 azelaic acid has calculated Log D = -3). It is known that the pH is crucial for the bacteriological activity of azelaic acid. It is only active at specific values of pH 4–6 where calculated Log D range is between 1.5 and -1 [

38]. As a result, the percutaneous absorption of azelaic acid was assessed to be 3.6% of the dermally applied dose [

39]. The plasma concentration and urinary excretion of azelaic acid are not significantly different from baseline levels following topical treatment with Azelex cream (20% w/w of an azelaic acid). Most likely that is a reason why topical formulations of azelaic acid require a higher dose (15% w/w or 20% w/w of azelaic acid) to reach the desired therapeutic effects for acne and other indications.

Azelaic acid is linked to cromoglicic acid via ester bond (Fisher esterification reaction between hydroxyl group of cromoglicic acid and carboxyl group of azelaic acid). The linkage of azelaic acid to cromoglicic acid via ester bond has a goal to increase a lipophilicity of the final mutual prodrug and thus to improve its skin penetrability. However, this intermediate mutual prodrug still has three ionizable carboxyl groups (

Figure 10, red circles) that significantly decrease compound’s lipophilicity.

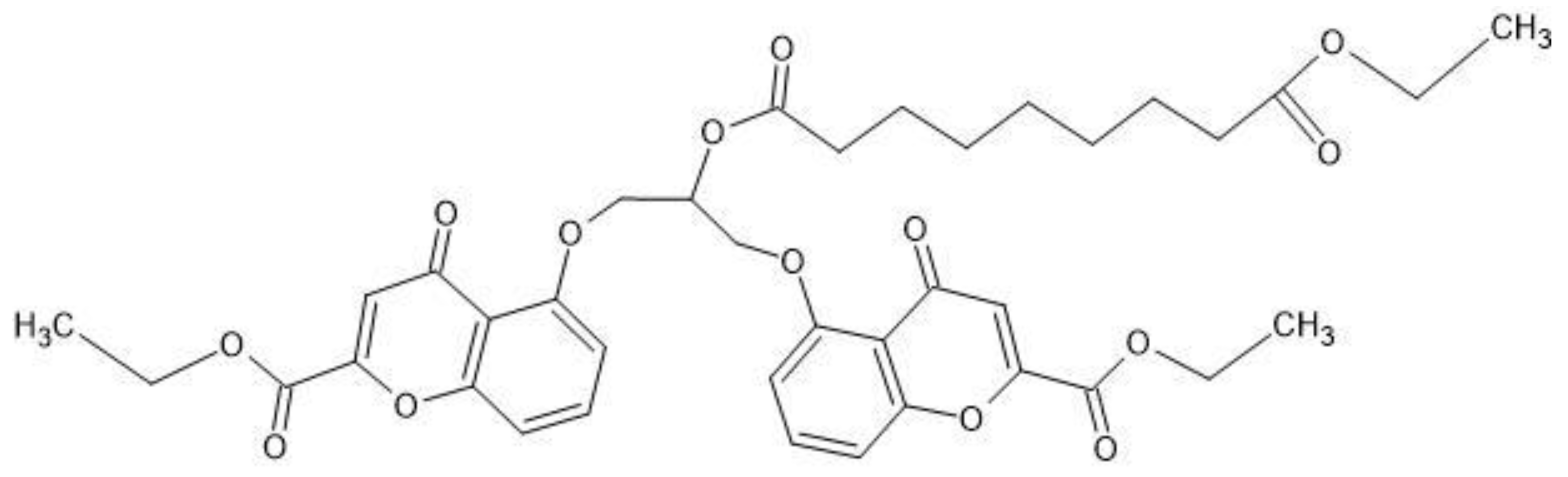

With the purpose of increasing mutual prodrug lipophilicity, all three free carboxyl groups were masked with ethyl residues linked via ester bonds. The ester bonds masked one ionizable carboxyl group on azelaic acid and two polar hydroxyl group on cromoglicic acid (

Figure 10). Thus, the final mutual prodrug is composed of a cromoglicic acid and an azelaic acid linked via ester bond where all three polar and ionizable carboxyl groups are masked with ethyl groups linked via ester bonds (

Figure 11). The calculated Log P of this compound is 4.15.

The azelaic acid in this tandem mutual prodrug serves a double role: 1) it is a carrier that increases mutual prodrug lipophilicity and 2) it is a parent drug that possesses active anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory compound approved by the FDA as an effective monotherapy in mild to moderate forms of acne in adolescent, adult male [

40] and female acne patients [

41]. Currently, cosmetic products that contain at least 10 w/w % azelaic acid are over-the-counter formulations. The products that contain 15 or 20 w/w % of azelaic acid are prescription drugs.

Cromoglicic acid (in form of sodium salt cromolyn sodium) is an effective and safe mast cell stabilizer that was approved by the FDA for human usage more than 35 years ago. Cromolyn sodium is available as an FDA-approved product in the nominated dosage form and ROA. Cromolyn sodium is also available as a 10% solution for inhalation and a 4% ophthalmic solution. Cromolyn sodium was available as an FDA-approved oral 100 mg capsule that was discontinued, not for reasons of safety or efficacy.

Cromolyn sodium is available as an OTC nasal product (NasalCrom nasal spray) in the US [

42].

Currently, there are no FDA approved commercial medicines in the form of topical cream, gel, or lotion that contain cromolyn sodium. Cromolyn sodium 4% and 10% Topical Cream is available from pharmacies providing compounded medications [

43,

44]. Numerous attempts to develop topical formulations with Cromolyn sodium to treat atopic dermatitis, chronic urticaria or “eczema” failed. Most likely it happened because of low transdermal absorption of this polar and charged compound. One example of failure is Altoderm™ topical cream that was claimed as a novel, proprietary formulation of topical cromolyn sodium that was designed to enhance the absorption of cromolyn sodium in order to treat atopic dermatitis, or “eczema”. This product candidate was tested in several clinical trials in the UK. Cromolyn sodium topical was administered for 12 weeks to 144 child subjects with moderately severe atopic dermatitis. In the study results, published in the

British Journal of Dermatology in February 2005, Altoderm™ demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in symptoms [

45]. During the study, subjects were permitted to continue with their existing treatment, in most cases this consisted of emollients and topical steroids. A positive secondary outcome of the study was a reduction in the use of topical steroids for the Altoderm™-treated subjects. The conclusion was that the topical use of sodium cromoglicate seemed to have a promising potential. However, since the efficacy of cromoglicate sodium for topical treatment of atopic dermatitis and other skin allergies was very low, all topical formulations containing cromolyn sodium failed to become FDA approved commercial products. Most likely the reason of failure was the extremely strong physical barrier of human skin (especially the skin hydrophobic layer

stratum corneum) for any polar and charged molecules [

46].

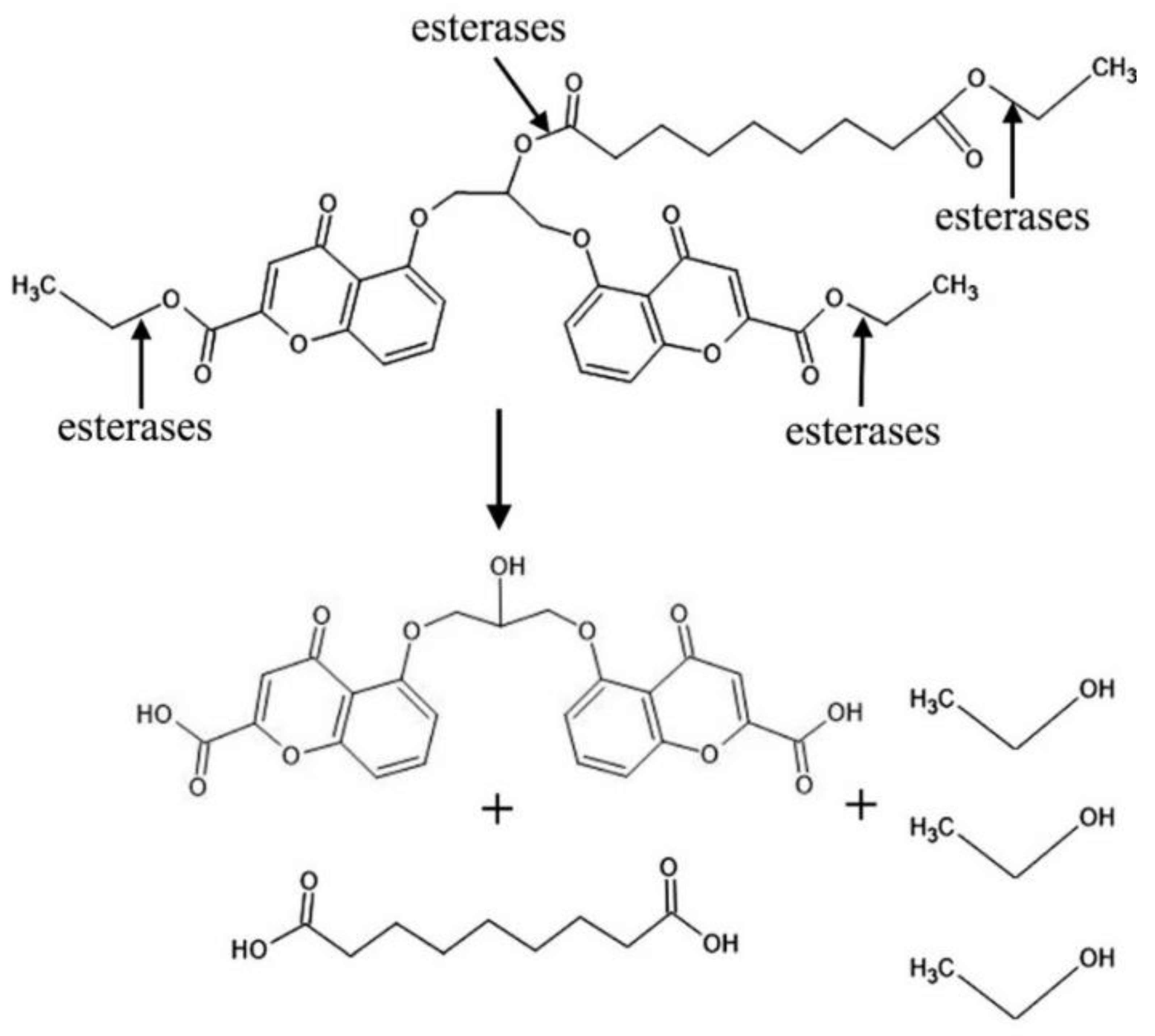

CromAzol™ cream contains 5% or 10% w/w of mutual prodrug triethyl cromoglicate azelate (

Figure 10). 5% or 10% w/w CromAzol™ cream should be applied directly on acne lesions. Both parental drugs will be liberated by skin esterases (

Figure 12) within viable layers of epidermis and dermis and the synergistic action of parental drugs will lead to significant alleviation of the inflammation process in acne lesions. According to recently published paper, pH value of human dermal interstitial fluid is at 8.60 range [

47]. Therefore, at this pH cromoglicic acid will be converted to its salt form. Since sodium is the main cation in human dermal interstitial fluid (concentration is 137 ± 17 mmol/L) [

48], the cromoglicic acid will be converted to cromolyn sodium immediately after hydrolysis by esterases.

Particularly for acne vulgaris our mutual prodrug CromAzol™ has one parent (basic) drug which is a cromoglicic acid and another parent drug which is an azelaic acid that serves as a carrier (increase lipophilicity of mutual prodrug) (

Figure 12).

Lipophilic mutual prodrug diffuses through stratum corneum to viable epidermis and dermis layers where skin esterase activity liberates a cromoglicic acid, an azelaic acid and three molecules of ethanol (

Figure 12).

Enzyme esterases tend to have relatively high activities within human skin [

22], and this metabolic activity has been exploited in the delivery of prodrugs with the increased lipophilicity (usually afforded by linking of aliphatic chains). High lipophilicity of prodrugs improves prodrug diffusion through the stratum corneum and uptake into deeper viable skin layers where esterases can liberate the free drug within the skin.

Cromoglicic acid in the form of its disodium salt (other name cromolyn sodium, sodium cromoglicate) is commercially available as an oral suspension, eye drops and a nasal spray. It mainly acts as a mast cell stabilizer [

5] by preventing the release of common inflammatory mediators such as histamine, prostaglandins, and others. This medication is used primarily to manage asthma attacks [

49] together with corticosteroid-based drugs. Additionally, it is very effective in alleviating allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis symptoms.

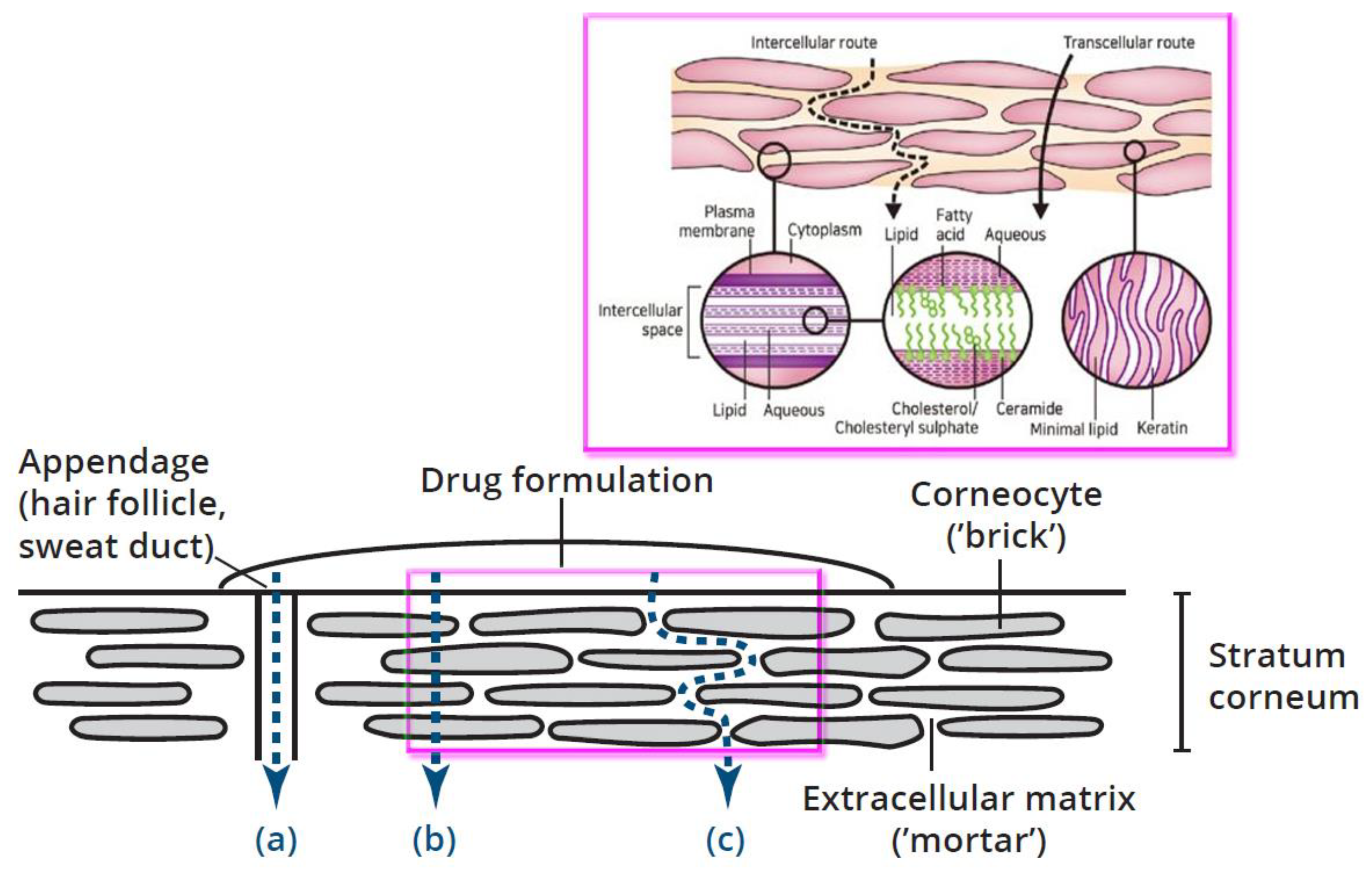

Cromolyn sodium is a hydrophilic, water-soluble compound with MW = 512.33 and partition coefficient P < 0.001 (Log D ≥ - 3) (measured at pH = 6.5 buffer and 1-octanol) [

36]. The water solubility of cromolyn sodium is high (195.3 mg/ml). These physicochemical properties prevent any effective transdermal delivery of cromolyn sodium through human skin (especially through its hydrophobic barrier,

stratum corneum). Water soluble molecules and drugs are normally not able to cross the skin as the skin is a natural barrier to water. The stratum corneum is composed of insoluble bundled keratins surrounded by a cell envelope, stabilized by cross-linked proteins, and covalently bound lipids (

Figure 13, magenta insert). It was shown that topically applied polar hydrophilic substances penetrate through human skin, mostly through skin appendages like hair follicles and sweat ducts (

Figure 13, bottom). On the contrary, lipophilic substances penetrate through the

stratum corneum via diffusion between (intercellular space) or close to the envelope of the corneocytes [

50]. Finally, it reaches for the viable layers of the skin - epidermis and dermis.

The orifices of the appendages were estimated to represent not more than 0.1% of the total skin surface [

53]. These estimates were recently corrected through measuring follicular orifice size and distribution of vellus hair follicles in different skin areas. It was found that the surface area of the follicular epithelium can be seen as a considerable enlargement of the skin surface, with variability in contribution depending on the skin area, follicular size and density [

54]. Thus, transdermal drug delivery that is based mostly on appendage/follicular penetration does not look very effective in comparison with drug delivery through the corneocytes or around them(

Figure 13, (b) and (c)).

CromAzol™ Cream Mechanism of Action (MoA)

Lipophilic mutual prodrug diffuses through the

stratum corneum to viable layers of epidermis and dermis that have high esterase activity [

22]. Skin esterases hydrolyze ester bonds in the mutual prodrug and liberate parent drugs a cromoglicic acid, an azelaic acid and three molecules of ethanol (

Figure 11). Ethanol is a natural metabolite in the human body and in addition it has some bactericidal activity [

55]. According to a recently published paper pH value of human dermal interstitial fluid is at 8.60 range [

47]. At this pH cromoglicic acid will be converted to salt form. Sodium is the main cation in human dermal interstitial fluid (concentration is 137 ± 17 mmol/L) [

48], so the cromoglicic acid will be converted to cromolyn sodium. Cromolyn sodium inhibits mast cells (stop degranulation process) [

5]. In addition, cromolyn sodium inhibits the assembly of an active nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase in the neutrophils [

6], thereby preventing tissue damage induced by oxygen radicals that happens during neutrophil influx in acne lesions.

The inhibition of mast cell degranulation stops the releasing of cytokines and chemokines that recruit innate immune cells to acne lesions and thus stop or at least effectively alleviate severe inflammation processes within acne lesions. An azelaic acid is bactericidal to

C. acnes and other bacteria (suppress its outgrowth in hair follicles and sebaceous glands) [

7] and it does not induce resistance in

C. acnes bacteria [

56]. In addition, azelaic acid goes deep within the pores and removes dead skin cells that cause dull skin tone and clogged pores [

8,

9] (

Figure 14). Thus, both compounds that are liberated simultaneously by skin esterases within acne lesions will have a strong synergistic effect that stops or significantly slow down acne proliferation leading to severe acne and scarring. Topical delivery of a safe and effective mast cell stabilizer and bactericide azelaic acid offers significant advantages in comparison with oral delivery of an oral mast cell stabilizer tranilast and antibiotic minocycline [

30]. Main benefits of topical delivery are: 1) an avoiding of gut microbiome exposure to antibiotics that can potentially disrupt healthy microbiome and induce dysbiosis [

33,

34]; 2) an avoiding of first-pass metabolism effect hat reduce the concentration of both active drugs in systemic circulation; 3) an avoiding of extra exposure of active drugs to systemic circulation; 4) decreasing of the chance to develop an antibiotic resistance (researchers have found that young and adult patients treated with antibiotics for acne are more likely to carry drug-resistant

C. acnes) [

57]; 5) direct delivery of all drugs into acne lesions where they needed.

In-Vitro Membrane Permeation Studies

In preliminary

in vitro studied we have compared skin penetrability of CromAzol™ and its parental drugs cromoglycate sodium and azelaic acid. The vertical PermeGear Franz cell was used to study in vitro transport (diffusion) of cromoglicate sodium, azelaic acid and its lipophilic and mutual prodrug. Shed snakeskin was used as a skin model. This is simple and reliable model membrane for human skin that used for preliminary permeability studies due to its similarity in composition to the human stratum corneum [

60]. The solution in the receiver compartment was maintained at 37°C and stirred at 500 rpm with a magnetic stirrer. Before each experiment, the shed snakeskin was hydrated in 7.4 pH Dulbecco′s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) containing 0.1% sodium azide solution for 24 hours at room temperature. To emulate the esterase activity of human skin, a “sandwich” of shed snakeskin from a black rat snake (

Pantherophis obsoletus) and a dialysis membrane with a molecular weight cut-off of 3.5 kDa (Cole-Palmer, Spectra Por S/P 3 EW-02900-04) was designed (

Figure 15).

PermeGear Franz cell with a diffusion area of 0.64 cm

2 and a volume of 2 mL in the donor and receiver compartments was used for all experiments. Recombinant Human Carboxylesterase 2/CES2 (R&D Systems, # 5657-CE) at a concentration 50 µg/mL was added between the snakeskin and the dialysis membrane (

Figure 15). The temperature in Franz cell was controlled via thermocouple probe IT-23 (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) (

Figure 16).

The receiver compartment was filled with 2 mL of 50% w/w polyethylene glycol 400 in DPBS to maintain a sink condition in the receiver solution. The donor compartment was filled with 2 mL 50% w/w polyethylene glycol 400 in DPBS to maintain a sink condition in the receiver solution.

For these in vitro experiments 10% CromAzol™ cream was used. The cream contains 10% w/w Triethyl Cromoglicate Azelate as an active compound. Inactive ingredients were 3% w/w calcium acetate (used as a gelation agent), PEG 400, 0.1% w/w Benzalkonium chloride (used as antibacterial agent) and water. CromAzol™ cream is opaque white cream with smooth texture. The cream holds its shape well (

Figure 17). The cream is non-greasy because it is oil-free. Creams with 10% w/w of cromoglicate sodium and 10% w/w of azelaic acid were used as comparators for 10% CromAzol™ cream.

10% w/w CromAzol™ cream was applied directly to the model skin surface in donor compartment (

Figure 18). The cream was well adhesive/sticky even to the hydrated snakeskin. The drop of cream (~ 10 mg) was applied to the model skin. The drop was visible during permeability experiment (12h). We have assumed that CromAzol™ cream is not dissolvable/degradable in 50% polyethylene glycol 400/DPBS solution.

In

in vitro system CromAzol™ has ~ 4X higher permeability through the model skin than its parental drugs azelaic acid and cromoglicate sodium (

Figure 19). Thus, these results prove that the increasing of lipophilicity of mutual prodrug leads to significant improvement of skin permeability of this compound.

CromAzol™ cream is non-comedogenic because its main solvent is PEG 400 that has comedogenic potential =1 [

61]. Therefore, PEG 400 has a very

low probability of clogging or blocking the pores on human skin. In addition, PEG 400 has

irritant factor = 0 [

62].

Experimental In Vivo Studies

CromAzol

™ cream active ingredient is Triethyl Cromoglicate Azelate (

Figure 11). After hydrolysis by esterases Triethyl Cromoglicate Azelate releases two safe parent drugs approved by FDA more than 30 years ago. Both parent drugs sodium cromolyn and azelaic acid have perfect safety profile and both of them available over the counter – as intranasal spray NasalCrom and 10% azelaic acid cream. Azelaic acid was first approved as a new molecular entity by FDA in 1995 as a topical cream (20%) produced by Allergan (Azelex

®; NDA 020428). As a topical product, Azelex was approved by the Division of Dermatology and Dental Products or DDDP) at FDA. Azelex is FDA-approved for the following indication: topical treatment of mild-to-moderate inflammatory acne vulgaris. According to the approved product labeling: “Azelaic acid is a human dietary component of a simple molecular structure that does not suggest carcinogenic potential, and it does not belong to a class of drugs for which there is a concern about carcinogenicity. Therefore, animal studies to evaluate carcinogenic potential with Azelex Cream were not deemed necessary. In a battery of tests (Ames assay, HGPRT test in Chinese hamster ovary cells, human lymphocyte test, dominant lethal assay in mice), azelaic acid was found to be nonmutagenic.”

Azelaic acid was also approved as a new dosage form in 2002 – as a 15% topical gel product (Finacea®; NDA 021470; Bayer Healthcare) – by the Dermatologic and Dental Drug Products Division for the topical treatment of the inflammatory papules and pustules of mild to moderate rosacea.

Cromoglicic acid (in form of its disodium salt cromolyn sodium) was first approved by the FDA in 1984. Cromolyn sodium was developed in the late 1950s and 1960s and became available in Great Britain in 1968 for prophylaxis of asthma. In 1977 10% sodium cromoglycate ointment was tested in clinical trials as a treatment of atopic eczema in children [

63]. At the end of treatment significantly more patients in the sodium cromoglicate group had benefited from treatment compared with only two patients in the placebo group. No patients experienced side effects. In 2005, 4% sodium cromoglicate (Altoderm) topical was administered for 12 weeks to 144 child subjects with moderately severe atopic dermatitis. In the study results, published in the

British Journal of Dermatology in February 2005, Altoderm™ demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in symptoms [

45]. During the study, subjects were permitted to continue with their existing treatment, in most cases this consisted of emollients and topical steroids. A positive secondary outcome of the study was a reduction in the use of topical steroids for the Altoderm™-treated subjects. The conclusion was that the topical use of sodium cromoglicate seemed to have a promising potential.

In addition, cromolyn sodium entered the US market in 1973 as a treatment for asthma. The mechanism of action is not entirely understood but its primary mechanism is to act as a mast cell stabilizer by inhibiting mast cell degranulation caused by immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody reactions and other nonimmunological substances. Cromolyn sodium has “anti-allergic, anti-pruritic and anti-inflammatory properties” and works by “[inhibiting] the release of inflammatory mediators from [sensitized] mast cells. It was mentioned that cromolyn sodium is “lipid insoluble and poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract after oral administration” and therefore the effects are “primarily topical” and must be considered when determining how to deliver the drug to the target organ. Cromolyn sodium is commercially available as a 4% ophthalmic solution to treat vernal keratoconjunctivitis, vernal conjunctivitis, and vernal keratitis, a 5.2 mg/ml spray nasal spray for treatment and prevention of nasal symptoms of hay fever and other nasal allergies, a 10 mg/mL solution for inhalation for the prophylaxis of bronchial asthma, and a 100 mg/5 mL oral concentrate for the management of mastocytosis.

CromAzol™ cream contains 10% (w/w) of the mutual prodrug Triethyl Cromoglicate Azelate. The molecular weight of this compound is 723 Da. Cromoglicic acid MW = 468 Da and azelaic acid MW = 188 Da. Skin esterases hydrolysis of mutual prodrug ester bonds liberate cromoglicic acid and azelaic acid at 1:1 ratio. 10% w/w CromAzol™ cream contains 6.4% w/w of cromoglicic acid, 2.6% w/w of azelaic acid and 1% w/w ethanol.

FDA approved Cromolyn sodium was administered as an oral 2% to 4% aqueous solution in doses ranging from 400 mg/day to 1600 mg/day for 8 weeks. Topically, cromolyn sodium has been administered as a topical 0.21% to 10% cream, lotion, nebulizer solution, emulsion, and ointment for 2-64 weeks. Currently, Cromolyn Sodium 10% Topical Ointment is manufactured by compounding pharmacy Bayview Pharmacy (3844 Post Road, Warwick, RI 02886) [

44].

Thus, topical dosages of azelaic acid and cromoglicic acid in 10% w/w CromAzol™ cream are significantly less in comparison with already tested in human clinical trials for topical formulations (20% w/w azelaic acid and 10% w/w cromolyn sodium).

An inventor of CromAzol™ cream performed self-testing of 10% w/w formulation during weeks and found that this formulation does not induce any irritation or other visible skin reactions (like redness, irritation, itching, skin rash, change in skin color or others) when applied 2 times per day on multiple face sites. Thus, the formulation was considered as safe for limited tests on volunteers with moderate-to-severe acne. One male volunteer with severe acne (IGA grade 4) was recruited to test 10% w/w CromAzol™ cream. With IGA grade 4 almost entire face involved with numerous papules and pustules, and nodules already present (

Figure 21).

Figure 20.

The Investigators’ Global Assessment Scale (IGA) was developed by Allen and Smith Jr. This system has become the template for assessing acne severity [

64].

Figure 20.

The Investigators’ Global Assessment Scale (IGA) was developed by Allen and Smith Jr. This system has become the template for assessing acne severity [

64].

Consent was obtained from study subject following the informed consent protocol. The volunteer had acne that started during previous 1.5 years and proliferate to grade 4 despite using multiple over the counter and prescription acne topical drugs that include Benzoyl Peroxide, Sulfur, topical antibiotics, (Clindamycin gel and solution), topical tretinoins etc. The last option proposed by his dermatologist was Accutane (oral isotretinoin). The patient rejected this option because he knew about very serious side effects of Accutane. The male volunteer was supplied with 10% w/w CromAzol™ cream and recommended to apply it one time per day in the morning directly on visible inflammatory lesions (papules, pustules and nodules). During CromAzol™ cream usage volunteer never mentioned any skin side effects during 3 months test and at the end of test period had decreasing of IGA grade from 4 to 1/0 (

Figure 21). With IGA grade 1 acne patients have a few scattered comedones and a few small papules. With IGA grade 0 residual hyperpigmentation and erythema may be present (

Figure 20).

Figure 21.

Volunteer face before (left) and after 3 months treatment with CromAzol™ cream (right).

Figure 21.

Volunteer face before (left) and after 3 months treatment with CromAzol™ cream (right).

The volunteer was asked to describe how the CromAzol™ cream acts on newly formed papules and pustules. The observation was enough simple – after cream application on newly formed papules and pustules (red sites that slightly painful after touch) they never proliferate to the late stage – nodules. After 1-2 days cream application papules and nodules just disappeared. New inflammatory lesions usually appeared far away (1-2 cm) from previously treated areas. At the end of 3 months test the volunteer practically stopped to use CromAzol™ cream because he had only a few scattered small papules. However, after a couple of weeks after complete stop of cream usage the volunteer mentioned that the number of papules and pustules started to increase.

Discussion

Acne causes great distress for tens of millions of sufferers in the US, hundreds of millions of sufferers worldwide and can result in anxiety and social problems. Current treatments for acne are not enough effective, regimens are complex, and side effects are common. Besides permanent scarring, the condition, which affects around 650 million people worldwide, can lead to anxiety and depression. There is still no effective cure for acne, and available treatments have significant drawbacks, yet there have been no novel products launched over the past 10 years — innovation is long overdue. Samdolite Pharmaceuticals plans to address this unmet need. The burden of acne vulgaris among adolescents and young adults has continued to increase in nearly all countries since the 1990s (with the highest rates observed in teenagers aged 15–19 years) [

4]. In the US alone, 5 million physician visits are attributed to acne annually, costing > 2 billion dollars [

67]. Cumulative prevalence approaches 100% in adolescence and decreases with age, affecting up to 64% of individuals aged 20–29 years and 43% of individuals aged 30–39 years, respectively [

68]. Significant increase in acne cases can only mean one thing – practically all acne treatments (oral and topical) that were designed based on traditional paradigm are not effective. This old paradigm suggested acne developed due to abnormal keratinocyte desquamation, leading to hyperkeratinization and comedogenesis (blockage of pores). Increased sebum accumulation in clogged pores thought to facilitate the growth of Propionibacterium acnes (now Cutibacterium acnes or C. acnes). Topical and oral antibiotics, various comedolytic agents, inhibitors of sebum production have only some moderate efficacies that in the best case stop or slow down acne proliferation in severe stages (IGA 3/4). As a result the majority of acne patients do not achieve success according to FDA guidance – see Table 1 and 2 in [

3].

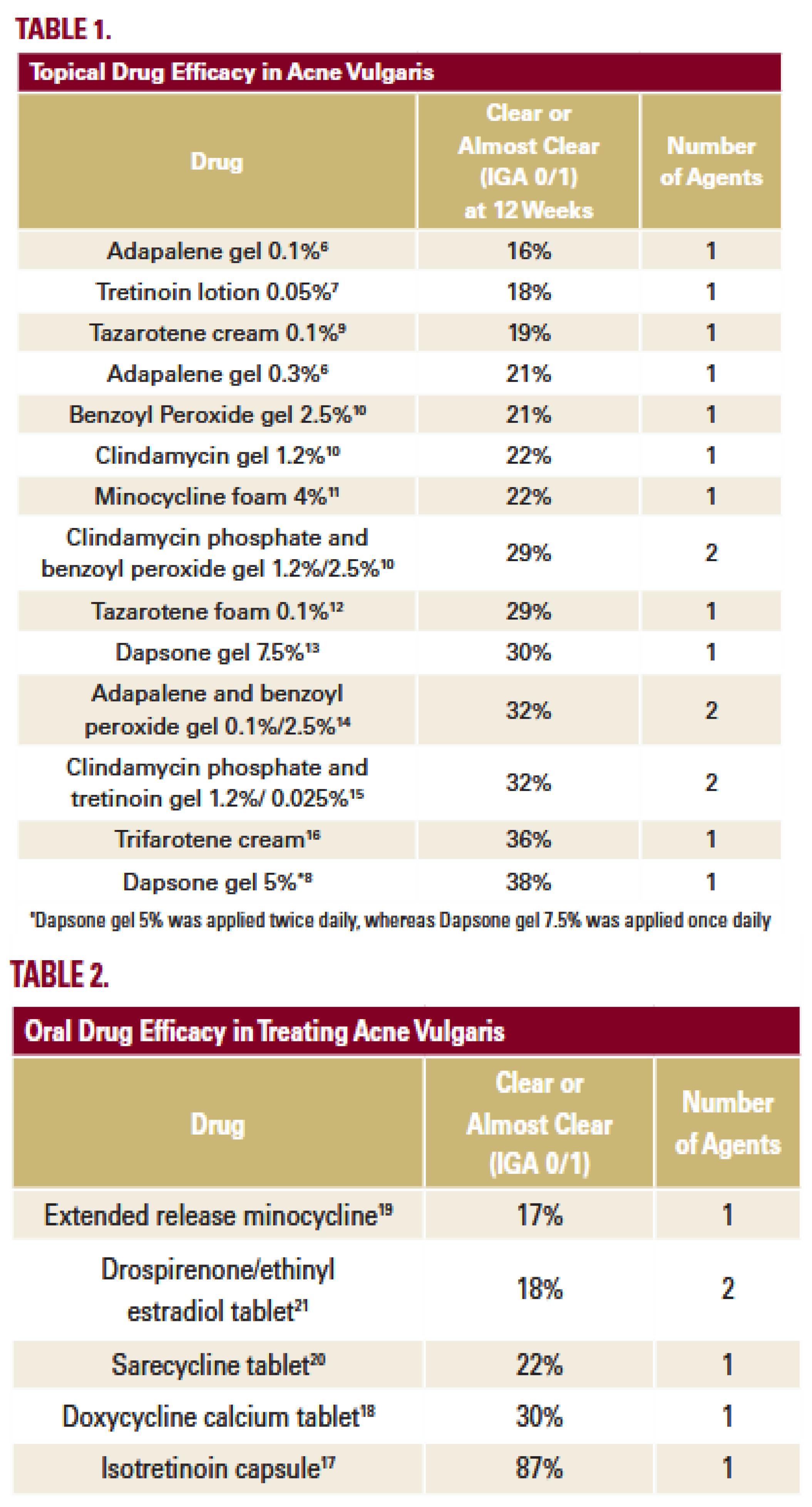

Table 1.

Patel et al. study demonstrates that the majority of physician-treated acne patients in the United States are not likely to achieve success according to FDA guidance. An exclusion is oral isotretinoin that has the highest IGA 0/1 at 87%. Of all outpatient acne visits, only 6% receive oral isotretinoin because this medication has very strong and dangerous side effects. None of the other medications had an IGA 0/1 > 40%.

Table 1.

Patel et al. study demonstrates that the majority of physician-treated acne patients in the United States are not likely to achieve success according to FDA guidance. An exclusion is oral isotretinoin that has the highest IGA 0/1 at 87%. Of all outpatient acne visits, only 6% receive oral isotretinoin because this medication has very strong and dangerous side effects. None of the other medications had an IGA 0/1 > 40%.

The new acne treatment paradigm emphasizes that acne is primarily an inflammatory condition. Research indicated subclinical inflammation in the skin of acne patients, even before microcomedone formation. Thus, inflammation is a central feature of acne, occurring at every stage of development. At severe acne stage (IGA 4) the inflammation can become chronic self-sustaining process when inflamed big lesions (nodules) do not show any evidence of viable bacterial colonization

. Therefore,

acne vulgaris can start as an acute inflammation i.e. the immune system’s response to

C. acnes proliferation in clogged pore and then it progresses to chronic inflammation when mast cells continue releasing of pro-inflammatory cytokines that recruit immune effectors cells (neutrophils, leucocytes, macrophages etc.) to inflamed sites when there is no primary trigger – viable C. acnes colonization. Chronic inflammation is an abnormal immune response in which the inflammatory process does not end when it should stop when trigger that started this process disappeared. With chronic inflammation, processes that normally protect human skin and body end up hurting them. Chronic inflammation can last for months or years. Chronic inflammation can lead moderate acne (IGA 1/2) to progress to severe stages – nodular and cystic acne that characterized by large lesions (nodules and/or cysts) that are 5 mm or more in diameter (

Figure 22).

Recently published review “Targeting Inflammation in Acne: Current Treatments and Future Prospects” provides an overview of emerging treatments of acne and their link to our current and improved understanding of acne pathogenesis [

71]. Authors note the role of both the innate and adaptive immune systems in acne pathogenesis and particularly the role of monocytic cells that release pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and IL-12. Cutibacterium acnes additionally activate the Nod-like receptor 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in monocytic cells, which leads to increased release of pro-inflammatory IL-1β. TLR-2, TLR-4, and these pro-inflammatory cytokines are all expressed in higher levels in acne lesions. It is known that monocytes can migrate into tissues and replenish resident macrophage populations. Macrophages have a high antimicrobial and phagocytic activity and thereby protect tissues from foreign substances. However, possible role of mast cells in acne pathophysiology was completely ignored in this review regardless of the study “Tranilast and Minocycline Combination for Intractable Severe Acne and Prevention of Postacne Scarring: A Case Series” that was published in 2022. Paper’s author Dr. Horiuchi mentioned in this study that mast cells are prominent in acne lesions and they involved in scar formation at severe acne. Tranilast is an oral mast cells inhibitor. It was the first time used for acne treatment. In this study it was dosed to severe acne patients in combination with antibiotic minocycline that routinely prescribed by dermatologists to acne patients with IGA 3/4 but usually has very modest efficacy -

Table 2 from [

3]. According to study results, all participants healed almost all their acne lesions without newly developed hypertrophic post acne scars. Severe acne patients (grade 4) took over 5 months to reach grade 0, but patients with grade 3 acne showed recovery after approximately 3–4 months of the combination therapy (

Table 1,

Figure 4). Tranilast acts directly on mast cells and inhibits their degranulation that releases numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines. Antibiotics including minocycline have powerful anti-inflammatory properties, which the dermatologist is also taking advantage of when prescribing antibiotics for acne. These facts taken together, support the hypothesis that combo acne treatment with tranilast + minocycline showed very prominent synergistic effect on acne inflammation process. The results support main principle of new acne treatment paradigm - anti-inflammatory drugs are expected to exert significant effects against all lesion stages, albeit via distinct anti-inflammation mechanisms.

The prominent role for mast cells in the inflammatory response has been increasingly well documented in recent years. Mast cells not only contribute to maintain homeostasis via degranulation and to generate IgE-mediated allergic reactions but also sit at a major crossroads for both innate and adaptive immune responses. The part played by mast cells in chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis identifies mast cells as a valuable treatment target in these diseases [

72]. Mast cells can express different receptors and ligands on the cell surface, molecules that can activate the cells of the immune system, such as different subsets of T cells. All these mediators and cell surface molecules can promote inflammation in the skin [

73]. Mast cells regulatory control over innate immune processes has made them successful targets to purposefully suppress their responses (mostly via degranulation process) in multiple therapeutic contexts. MC number and CD69 expression peaked in the closed comedone stage, indicating that activated MCs are involved in early acne lesions [

74].

Researchers from Prof. Kaplan’s lab, Pitt Department of Dermatology, University of Pittsburgh recently published research article “Agonism of the glutamate receptor GluK2 suppresses dermal mast cell activation and cutaneous inflammation” [

75]. The researchers found that a compound called SYM2081 inhibited inflammation-driving mast cells in mouse models and human skin samples, paving the way for new topical treatments to prevent itching, hives and other symptoms of skin conditions driven by mast cells.

In a previous

Cell paper, Kaplan and his team found that neurons in the skin release a neurotransmitter called glutamate that suppresses mast cells [

76]. When they deleted these neurons or inhibited the receptor that recognizes glutamate, mast cells became hyperactive, leading to more inflammation. “This finding led us to wonder if doing the opposite would have a beneficial effect,” said Kaplan. “If we activate the glutamate receptor, maybe we can suppress mast cell activity and inflammation.”

To test this hypothesis, lead author Youran Zhang, a medical student at Tsinghua University who did this research as a visiting scholar in Kaplan’s lab, and Tina Sumpter, Ph.D., a research assistant professor in the Pitt Department of Dermatology, looked at a compound called SYM2081, or 4-methylglutamate, that activates a glutamate receptor called GluK2 found almost exclusively on mast cells. Sure enough, they found that SYM2081 effectively suppressed mast cell degranulation and proliferation in both mice and human skin samples. And when the mice received a topical cream containing SYM2081 before the induction of rosacea- or eczema-like symptoms, skin inflammation and other symptoms of disease were much milder.

According to Prof. Kaplan, these findings suggest that suppressing mast cells with a daily cream containing a GluK2-activating compound could be a promising way to prevent rosacea and other inflammatory skin conditions. This article supports the hypothesis that hyperactive mast cells trigger an inflammation process, then support it and lead to chronic inflammation. Because inflammation is critical for all types of mast cells driven diseases, anti-inflammatory drugs are expected to exert significant effects against all these diseases, albeit with distinct factors that triggers these diseases. Prof. Kaplan study results showed that suppressing of mast cell activity leads to alleviation of skin inflammation and rosacea- or eczema-like symptoms in mice animal model.

Based on a new paradigm for acne treatment we explore a new approach and designed a mutual prodrug for topical treatment of acne vulgaris. The chemical’s name of mutual prodrug is Triethyl Cromoglicate Azelate (proposed brand name CromAzol™ cream). This compound is a chemical combination of two drugs previously approved by the FDA active moieties (cromoglicic acid and azelaic acid) that are linked via an ester bond (see

Figure 11). Triethyl Cromoglicate Azelate is composed of cromoglicic acid linked with azelaic acid via ester bond where residues carboxyl groups are masked by esterification with ethanol (

Figure 11). thus, active drugs are taken together with next aims: 1) to increase the lipophilicity of a mutual prodrug and thus to increase its permeability through human skin; 2) to provide a synergistic action at the application site (acne vulgaris) i.e. simultaneously suppress bacteria

C. acnes overgrowth and to inhibit activated mast cells. After releasing from mutual prodrug parent drug sodium cromolyn prevents mast cells degranulation that release alarm signals to other immune cells (leukocytes, neutrophils, macrophages and others) that are responsible for severe inflammation process at acne lesions. The active moieties (cromolyn sodium and azelaic acid) have not been previously marketed or approved as a physical combination. Classification code assigned by the Center or Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) provides a way of categorizing new drug applications (NDA) [

77]. According to this document Type 2 NDA is for a drug product that contains a new active ingredient, but not a New Molecular Entity (NME). A new active ingredient includes those products whose active moiety has been previously approved or marketed in the United States, but whose particular ester, salt, or noncovalent derivative of the unmodified parent molecule has not been approved by the Agency or marketed in the United States, either alone, or as part of a combination product.

Type 4 NDA is for a new drug-drug combination of two or more active ingredients. An application for a new drug-drug combination product may have more than one classification code if at least one component of the combination is an NME or a new active ingredient. The new product may be a physical or chemical (e.g., covalent ester or noncovalent derivative) combination of two or more active moieties.

An NDA for an active ingredient that is a chemical combination of two or more previously approved or marketed active moieties that are linked by an ester bond is classified as a Type 2,4 application if the active moieties have not been previously marketed or approved as a physical combination. If the physical combination has been previously marketed or approved, however, such a product would no longer be considered a new combination, and the NDA would thus be classified as Type 2.

The active ingredients cromolyn sodium and azelaic acid have not been previously marketed or approved as a physical combination. In our mutual prodrug cromoglicic acid and azelaic acid are linked by an ester bond. In addition, three residue ionizable carboxyl groups are masked by ethyl groups linked via ester bonds (

Figure 11).

Based on FDA provided way of categorizing new drug applications (NDA) we have assumed that our mutual prodrug would be classified as Type 2,4 - a new combination containing previously approved and marketed active moieties where the active moieties have not been previously marketed or approved as a physical combination.

Many novel drugs are tested in preclinical studies in animal disease models where non-human animals bear pathologies that share features with a human disease. The animal models for acne vulgaris are not well-established and they may not predict all features of the acne in humans. For example, we have contacted with preclinical efficacy CRO company

IMAVITA [

78]

that claimed that they have P. acnes Infection Acne Model and

Rhino Mouse Acne Modelfor

topical route applications and testing of dermatological products. IMAVITA claims that

Rhino mouse acne model has been useful in assessing the

comedolytic activity of drugs/compounds (

particularly for topical retinoids).

The problem is that published scientific study showed that cromolyn sodium (at 10 mg/kg in vivo or 10 – 100 μM in vitro) did not inhibit IgE-dependent mast cell activation in mice

in vivo (measuring Evans blue extravasation in passive cutaneous anaphylaxis and increases in plasma histamine in passive systemic anaphylaxis) and

in vitro (measuring peritoneal mast cell β-hexosaminidase release and prostaglandin D2 synthesis) [

79]. At the same time authors have demonstrated that under the conditions tested, cromolyn sodium inhibits those mast cell-dependent responses in rats. On the contrary, cromolyn also failed to inhibit ear swelling or leukocyte infiltration at sites of passive cutaneous anaphylaxis in mice. Cromolyn did not inhibit IgE-dependent degranulation in mouse peritoneal mast cells PMCs even at high concentration 100 μM. On the contrary, the simultaneous addition of cromolyn (10 – 100 μM) inhibited antigen-induced IgE-dependent degranulation of rat PMCs in a concentration-dependent manner [

79]. Thus, skin and peritoneal mast cells in mice are substantially less responsive to cromolyn than are the corresponding mast cell populations in the rats. Therefore, preclinical efficacy testing of our topical acne drug may provide unreliable results in the proposed Rhino mouse acne model. Unfortunately, there are no preclinical efficacy CRO companies that provide rat acne models or acne models in other animal species.

Formulations applied to the skin are classified into two types: 1) transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDSs), which are expected to have systemic effects as a result of the distribution of the active substance through systemic circulation

via blood capillaries in the dermis, and 2) topical preparations, which exhibit local effects as a result of persisting in the skin or in the musculoskeletal system under the skin. The purpose of the CromAzol™ cream is delivering parent compounds (cromolyn sodium and azelaic acid) mostly in the skin with lowest systemic exposure. However, it is possible that some parent compounds will distribute into systemic circulation

via blood capillaries in the dermis. For example, it was shown that systemic absorption of sodium cromoglicate (SCG) from 4 % w/w cutaneous emulsion (Altoderm ®) in children with atopic dermatitis was low. The mean amount of Altoderm ® applied each day was 7.78 ± 5.31 g (Range 3-20 g). The mean percentage of SCG absorbed was 1.46 ± 0.91% (Range 0.03-2.68%) [

80]. Authors mentioned that a previous study in atopic dermatitis, using a 4% concentration of SCG in oil in water cream measured the amount of SCG in 24-hour urine specimens and reported absorption of 0.44 ± 0.02% (mean ± SE) [

81]. Thus, the mean absorption from the 4% cutaneous emulsion we used was therefore 3 times greater than that from the 4% cream used in that study. In addition, authors evaluated the safety of sodium cromoglicate in respect of systemic exposure was determined using the inhaled route in man. It is described in detail in a review by Cox et al. [

82]. Pharmacokinetic studies that have been undertaken using this system, have shown that, on average, 12% of the inhaled dose is deposited in the respiratory tract, but it can be as high as 17.1%. That proportion of the drug reaching the respiratory tract is absorbed. The remainder is swallowed, of which up to 1% is absorbed [

83]. The maximum approved dose via inhalation is 2 × 20 mg, four times daily or 160 mg/day. Assuming that up to 18% of this could be absorbed systemically; this would give an upper limit for daily systemic exposure of 28.8 mg/day. The author assumed that taking the maximum figures recorded, 20 g of Altoderm lotion (800 mg SCG) applied per day and 2.68% absorption, this would give a potential of 21 mg of SCG absorbed/day, below that approved for inhalation use. Cromolyn sodium is safe when delivered into systemic circulation via oral route (dosage 800 mg per day).

Topically applied 20% w/w azelaic acid (Azelex cream) is associated with relatively high systemic exposure, which is presumed innocuous because it is a normal dietary constituent whose endogenous levels are not altered by topical use [

84]. The percutaneous absorption of azelaic acid was assessed to be 3.6% of the dermally applied dose [

39]. The plasma concentration and urinary excretion of azelaic acid are not significantly different from baseline levels following topical treatment with Azelex cream (20% w/w of an azelaic acid).

We have developed topical formulation CromAzol™ cream that contains 5% or 10% w/w Triethyl Cromoglicate Azelate as an active compound. Inactive ingredients in formulation are 3% w/w calcium acetate (used as a gelation agent), PEG 400, 0.1% w/w Benzalkonium chloride (used as antibacterial agent) and water. CromAzol™ cream is opaque white cream that holds its shape well and it has smooth texture (

Figure 15). The cream is non-greasy because it is oil free. We are going to test this formulation in animal toxicology preclinical studies that were requested by FDA after pre-IND meeting. After IND application approved by FDA we are going to proceed with human Phase 1 safety study. For the dermatology phase I studies patients with indication disease are usually recruited. The reason is that their skin usually has different permeability and sensitivity in comparison with healthy volunteers. Thus, secondary measurement after safety observations is an efficacy. Thus, Phase 1 clinical trial with CromAzol™ cream can reveal how effective this novel drug for acne treatment.

Additional Application for CromAzol Cream - Rosacea

We have discussed this subject with several lead dermatologists and got their opinion that CromAzol™ cream can be used for other mast cell driven diseases, especially for rosacea. Impacting approximately 5% of the adult population worldwide, rosacea can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life and lead to self-abasement, depression, anxiety and social phobia. Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects ~16 million Americans (The National Rosacea Society website). The idea that mast cells appear to play an intricate role in the pathophysiology of rosacea and could serve as potential targets for future therapies was supported by numerous studies.

“The clinical presentations of rosacea are diverse, but blushing resulting from an exaggerated vasodilatory response to various triggers is a shared feature among patients across the rosacea spectrum,” says Dr. Webster, Webster Dermatology, Hockessin, Del. “If we are looking for a single way to treat rosacea, it may be time to go after the mast cell and its interactions with vascular smooth muscle and vasomotor nerves.”[

85]

Recently, increasing evidence has indicated that mast cells have important effects on the pathogenesis of rosacea. In review article, authors describe recent advances of skin mast cells in the development of rosacea [

86]. “Mast cells participate in the pathogenesis of rosacea through innate immune responses, neurogenetic inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibrosis. Mast cells can be important immune cells that connect innate immunity, nerves, and blood vessels in the development of rosacea, no matter what the subtypes,” the authors write. One study showed that the number of mast cells was significantly higher in lesions than in clinically uninvolved skin in patients with papulopustular and erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, and there was a positive correlation between mast cell density and the duration of rosacea. According to the authors, adaptive immunity along with the innate immune system might play a critical role in the pathophysiology of rosacea; past studies have shown that mast cells can heighten host defense by initiating inflammation associated with innate immune responses [

87].

Thus, mast cells appear to play an intricate role in the pathophysiology of rosacea and could serve as potential targets for future therapies. Once activated, the mast cells can promote the release of different mediators and have a considerable effect on the pathophysiology of diverse inflammatory diseases,” Dr. Wang et al. write [

86]. According to the study authors, the important role of mast cells makes them a potential target for drug therapy. However, more studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy for its inhibition in the treatment of rosacea.

In one clinical study 10 patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (ETR) were chosen to topically apply either 4% cromolyn sodium or placebo on their faces [

88]. After 8 weeks, only the cromolyn treatment group showed some decreasing of facial erythema. In addition, MMP activity was markedly decreased in the cromolyn treatment group with mildly decreased KLK activity and LL-37 protein levels [

88]. These results indicate that cromolyn or other mast cell stabilizers may be a potential therapy for rosacea, especially ETR, through the inhibition of mast cell activation.

In my opinion, the weak results of this study can be explained by very low permeability of sodium cromolyn through human skin. This polar, charged and water-soluble compound just cannot diffuse through

stratum corneum layer of human skin. It can pass through the skin only via the hydrophilic pathways i.e. through appendages of sweat glands [

89] (see

Figure 13). The hair follicles and sweat glands were assumed to cover only 0.1% of the skin surface and therefore were considered to be irrelevant for skin penetration processes [

53]. Thus, the penetration of hydrophilic compounds applied to skin in form of water solution is negligible.

There is some good evidence that an inhibition of mast cells degranulation prevents rosacea like inflammation. In 2019 Dr. Di Nardo has published paper “Botulinum toxin blocks mast cells and prevents rosacea like inflammation”[

90]. Authors showed that “dermal mast cell degranulation is blocked by onabotulinum toxin in vivo and onabotulinum toxin reduces expression of rosacea biomarkers”. Authors concluded that well-formulated “topical BoNT may be appropriate for further study in the treatment of rosacea” [

90]. However, the topical application of protein with average molecular weight 800-900 kDa to human skin looks not feasible approach because of strong barrier properties of skin upper layer

stratum corneum [

46].

Rosacea is effectively treated by intense pulsed light (IPL) [

91]. Authors discovered that the photobiomodulation effect of IPL for rosacea treatment may inhibit mast cells degranulation and alleviate inflammatory reactions [

91].

The researchers from Prof. Kaplan’s lab (Department of Dermatology, University of Pittsburgh) recently published article “Agonism of the glutamate receptor GluK2 suppresses dermal mast cell activation and cutaneous inflammation” [

75]. They found that SYM2081 effectively suppressed mast cell degranulation and proliferation in both mice and human skin samples. When the mice received a topical cream containing SYM2081 before the induction of rosacea- or eczema-like symptoms, skin inflammation and other symptoms of disease were much milder. The suppression of MC degranulation inhibits inflammation-driving mast cells paving the way for new topical treatments to prevent itching, hives and other symptoms of skin condition driven by mast cells.

Thus, despite the chemical compounds or physical methods the inhibition of mast cells degranulation looks very promising approach in further managing of rosacea.

CromAzol™ cream that effectively drags mast cell stabilizer through human skin could be a very effective drug for rosacea. The first parent drug released by human skin esterases is cromoglicic acid. According to published study, pH value of human dermal interstitial fluid is at 8.60 range [

47]. Therefore, at this pH cromoglicic acid will be converted to its salt form. Since sodium is the main cation in human dermal interstitial fluid (concentration is 137 ± 17 mmol/L) [

48], the cromoglicic acid will be converted to cromolyn sodium immediately after hydrolysis by esterases. Cromolyn sodium inhibits mast cells (stop degranulation process) [

5]. In addition, cromolyn sodium inhibits the assembly of an active nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase in the neutrophils [

6], thereby preventing tissue damage induced by oxygen radicals that happens during neutrophil influx in acne lesions.

The second parent drug in mutual prodrug triethyl cromoglicate azelate is an azelaic acid. This compound is already approved for rosacea. Azelaic acid 15% gel (Finacea) has multiple modes of action in rosacea, but an anti-inflammatory effect achieved by reducing reactive oxygen species appears to be the main pharmacological action. Clinical studies have shown that azelaic acid 15% gel is an effective and safe first-line topical therapeutic option in patients with mild-to-moderate papulopustular rosacea [

92]. Mast cell stabilizer and anti-inflammatory azelaic acid delivered simultaneously in rosacea sites may have synergistic effect on the inflammation process and therefore should more effectively stop the inflammation process (

Figure 23).