Submitted:

31 May 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. MRI Protocol

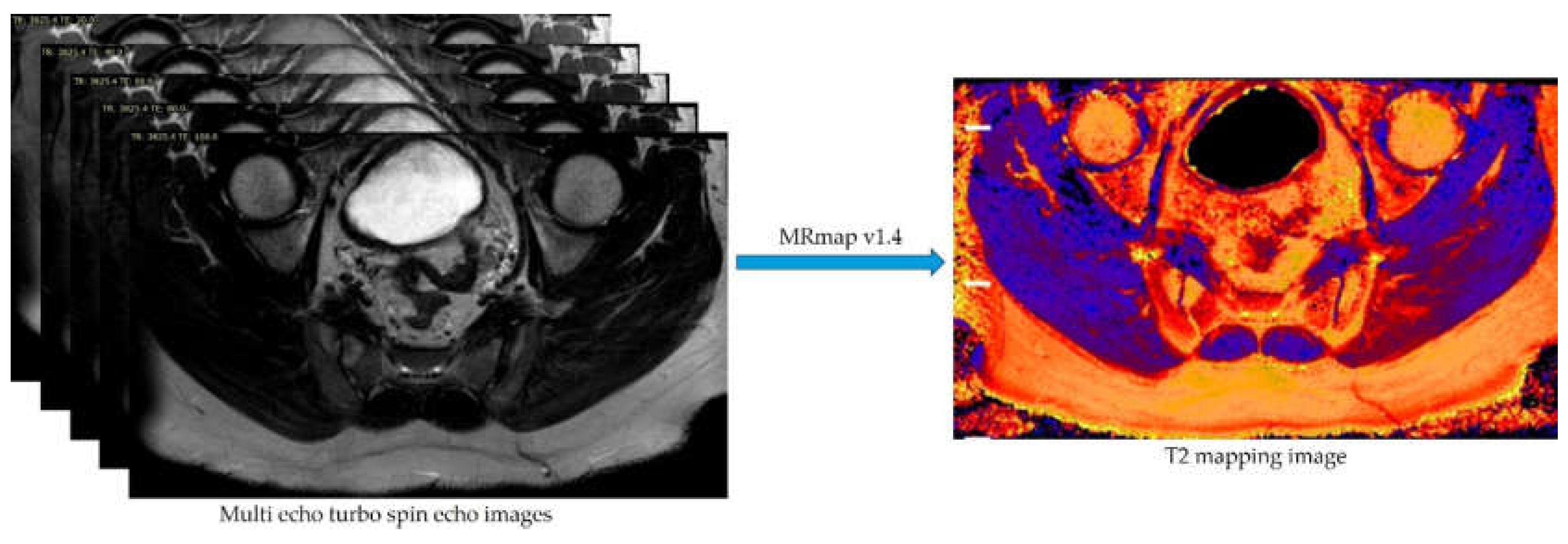

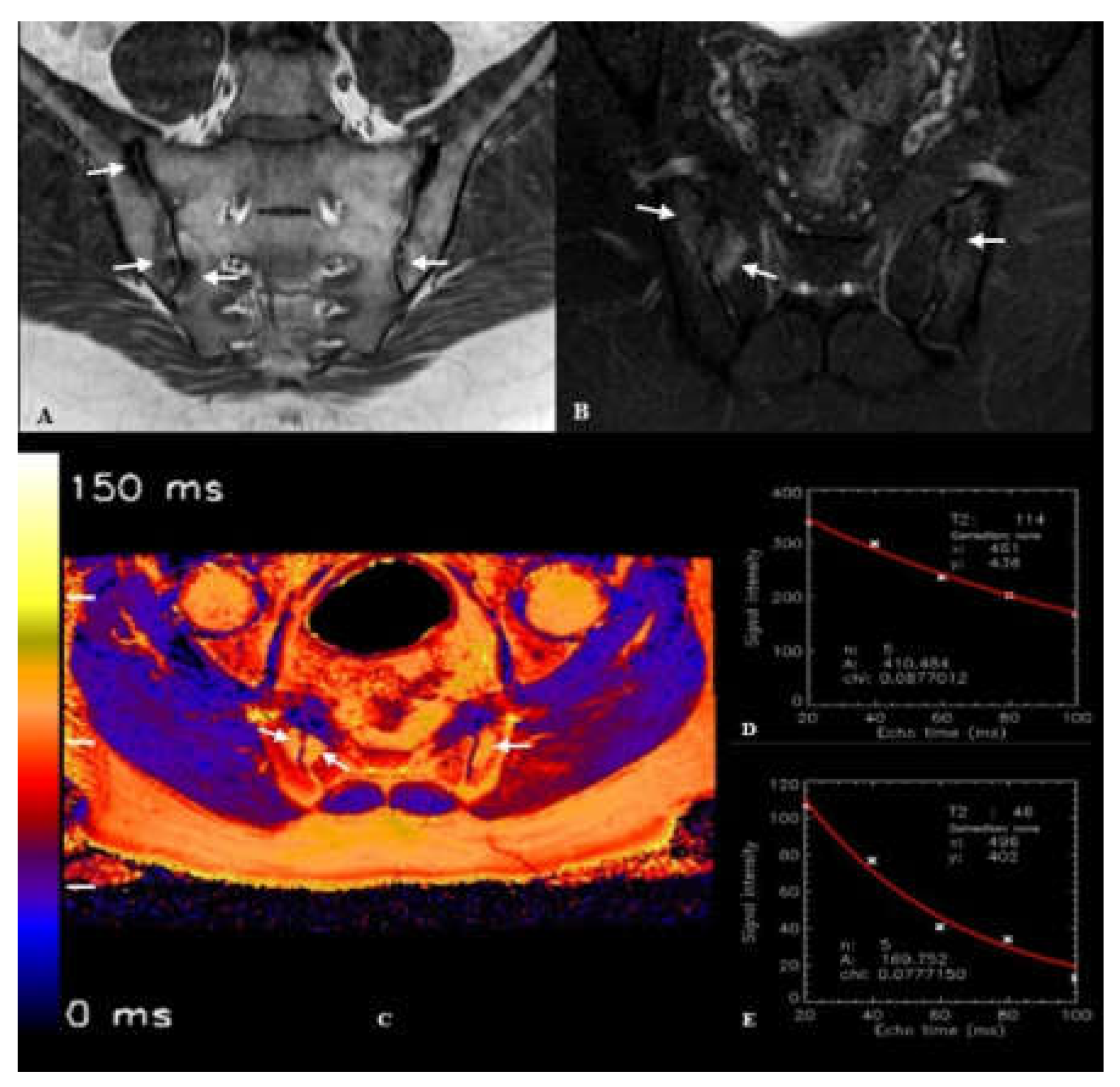

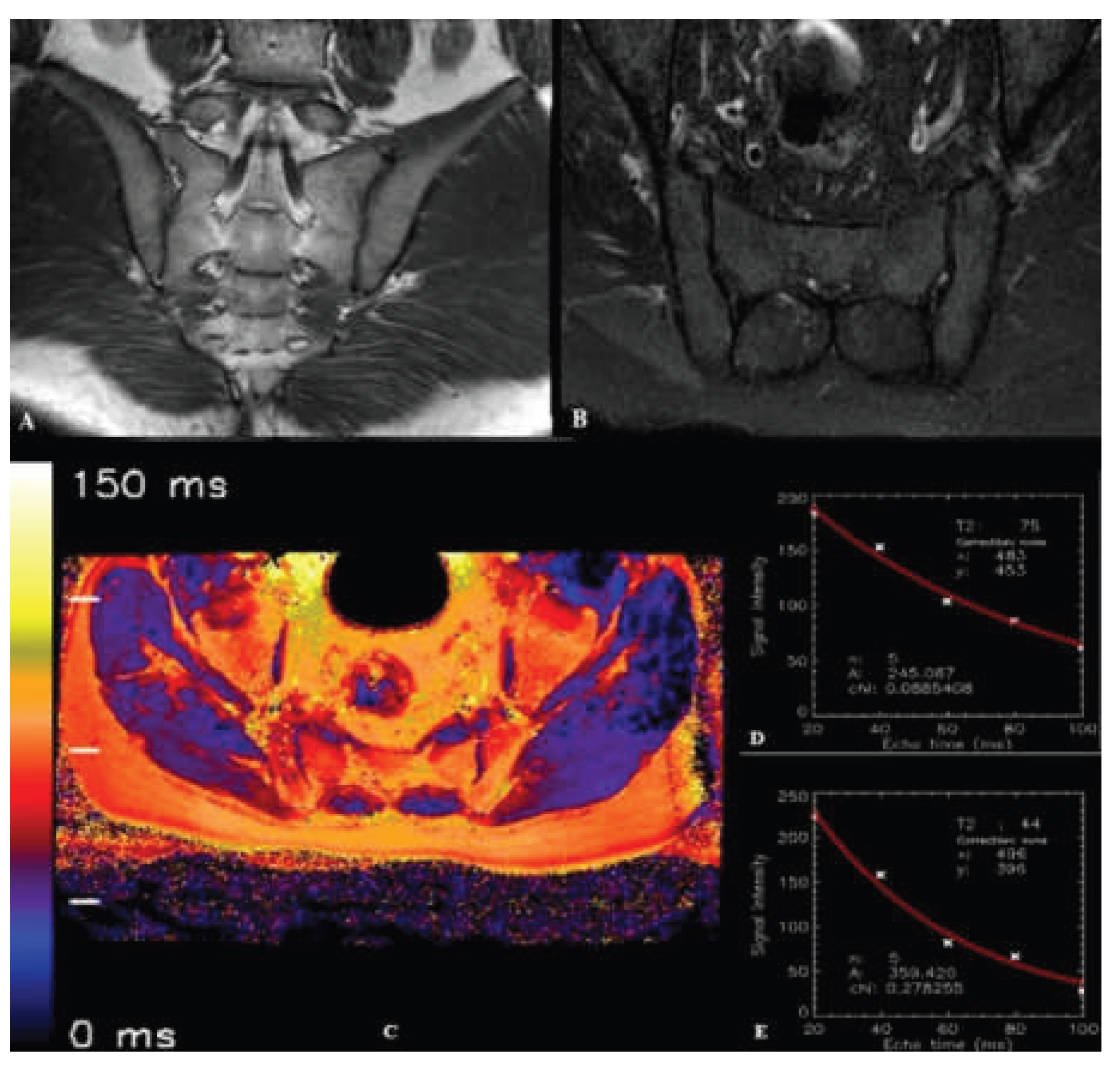

2.3. Image Processing and T2 Relaxation Time Measurement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen, S.P. Sacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2005, 101, 1440–1453. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoi, C.; Griffith, J.F.; Lee, R.K.L.; Wong, P.C.H.; Tam, L.S. Imaging of sacroiliitis: Current status, limitations and pitfalls. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2019, 9, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cihan, O.F.; Karabulut, M.; Kilincoglu, V.; Yavuz, N. The variations and degenerative changes of sacroiliac joints in asymptomatic adults. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2021, 80, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, M.; Mavi, A.; Gümüsburun, E.; Bayram, M.; Gürsoy, S.; Nishio, H. Anatomical variations with joint space measurements on CT. Kobe J Med Sci 2007, 53, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Sudol-Szopinska, I.; Urbanik, A. Diagnostic imaging of sacroiliac joints and the spine in the course of spondyloarthropathies. Pol J Radiol 2013, 78, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudwaleit, M.; Khan, M.A.; Sieper, J. The challenge of diagnosis and classification in early ankylosing spondylitis: do we need new criteria? Arthritis Rheum 2005, 52, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieper, J.; Rudwaleit, M.; Baraliakos, X.; Brandt, J.; Braun, J.; Burgos-Vargas, R.; Dougados, M.; Hermann, K.G.; Landewé, R.; Maksymowych, W.; et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009, 68 Suppl 2, ii1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navallas, M.; Ares, J.; Beltrán, B.; Lisbona, M.P.; Maymó, J.; Solano, A. Sacroiliitis associated with axial spondyloarthropathy: new concepts and latest trends. Radiographics 2013, 33, 933–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgen, A. The Value of the T2-Weighted Multipoint Dixon Sequence in MRI of Sacroiliac Joints for the Diagnosis of Active and Chronic Sacroiliitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017, 208, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banegas Illescas, M.E.; López Menéndez, C.; Rozas Rodríguez, M.L.; Fernández Quintero, R.M. [New ASAS criteria for the diagnosis of spondyloarthritis: diagnosing sacroiliitis by magnetic resonance imaging]. Radiologia 2014, 56, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Zheng, J.; Hong, G. Synthetic MRI in the detection and quantitative evaluation of sacroiliac joint lesions in axial spondyloarthritis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1000314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirbach, S.; Trattnig, S.; Marlovits, S.; Zimmermann, V.; Domayer, S.; Dorotka, R.; Mamisch, T.C.; Bohndorf, K.; Welsch, G.H. Initial results of in vivo high-resolution morphological and biochemical cartilage imaging of patients after matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte transplantation (MACT) of the ankle. Skeletal Radiol 2009, 38, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefebvre, G.; Bergere, A.; Rafei, M.E.; Duhamel, A.; Teixeira, P.; Cotten, A. T2 Mapping of the Sacroiliac Joints With 3-T MRI: A Preliminary Study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017, 209, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albano, D.; Chianca, V.; Cuocolo, R.; Bignone, R.; Ciccia, F.; Sconfienza, L.M.; Midiri, M.; Brunetti, A.; Lagalla, R.; Galia, M. T2-mapping of the sacroiliac joints at 1.5 Tesla: a feasibility and reproducibility study. Skeletal Radiol 2018, 47, 1691–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Stemmer, A.; Poncelet, B.P. T2 measurement of the human myocardium using a T2-prepared transient-state TrueFISP sequence. Magn Reson Med 2007, 57, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baessler, B.; Schaarschmidt, F.; Stehning, C.; Schnackenburg, B.; Maintz, D.; Bunck, A.C. Cardiac T2-mapping using a fast gradient echo spin echo sequence - first in vitro and in vivo experience. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, S.; Chang, S.D.; Savdie, R.; Zhang, J.; Jones, E.C.; Goldenberg, S.L.; Black, P.C.; Kozlowski, P. Luminal Water Imaging: A New MR Imaging T2 Mapping Technique for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Radiology 2017, 284, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Bronskill, M.J.; Henkelman, R.M. Magnetization transfer and T2 relaxation components in tissue. Magn Reson Med 1995, 33, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkelman, R.M.; Stanisz, G.J.; Kim, J.K.; Bronskill, M.J. Anisotropy of NMR properties of tissues. Magn Reson Med 1994, 32, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, K.J. The dynamics of water in heterogeneous systems. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1977, 278, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Chu, C.; Dou, X.; Chen, W.; He, J.; Yan, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, X. Early evaluation of radiation-induced parotid damage in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma by T2 mapping and mDIXON Quant imaging: initial findings. Radiat Oncol 2018, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ece, B.; Yigit, H.; Ergun, E.; Koseoglu, E.N.; Karavas, E.; Aydin, S.; Kosar, P.N. Quantitative Analysis of Supraspinatus Tendon Pathologies via T2/T2* Mapping Techniques with 1.5 T MRI. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baessler, B.; Luecke, C.; Lurz, J.; Klingel, K.; von Roeder, M.; de Waha, S.; Besler, C.; Maintz, D.; Gutberlet, M.; Thiele, H.; et al. Cardiac MRI Texture Analysis of T1 and T2 Maps in Patients with Infarctlike Acute Myocarditis. Radiology 2018, 289, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hueper, K.; Lang, H.; Hartleben, B.; Gutberlet, M.; Derlin, T.; Getzin, T.; Chen, R.; Abou-Rebyeh, H.; Lehner, F.; Meier, M.; et al. Assessment of liver ischemia reperfusion injury in mice using hepatic T(2) mapping: Comparison with histopathology. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018, 48, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T.C.; Lu, Y.; Jin, H.; Ries, M.D.; Majumdar, S. T2 relaxation time of cartilage at MR imaging: comparison with severity of knee osteoarthritis. Radiology 2004, 232, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazovic-Stojkovic, J.; Mosher, T.J.; Smith, H.E.; Yang, Q.X.; Dardzinski, B.J.; Smith, M.B. Interphalangeal joint cartilage: high-spatial-resolution in vivo MR T2 mapping--a feasibility study. Radiology 2004, 233, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizlin, Z.V.; Clement, J.J.; Patola, W.B.; Fenton, D.M.; Gillies, J.H.; Vos, P.M.; Jacobson, J.A. T2 mapping of articular cartilage of glenohumeral joint with routine MRI correlation--initial experience. HSS J 2009, 5, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, T.J.; Dardzinski, B.J. Cartilage MRI T2 relaxation time mapping: overview and applications. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2004, 8, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzat, S.J.; McWalter, E.J.; Kogan, F.; Chen, W.; Gold, G.E. T2 Relaxation time quantitation differs between pulse sequences in articular cartilage. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015, 42, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, K.E.; Besier, T.F.; Pauly, J.M.; Han, E.; Rosenberg, J.; Smith, R.L.; Delp, S.L.; Beaupre, G.S.; Gold, G.E. Prediction of glycosaminoglycan content in human cartilage by age, T1rho and T2 MRI. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011, 19, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.M.; Sussman, M.S.; Hurtig, M.; Probyn, L.; Tomlinson, G.; Kandel, R. Cartilage T2 assessment: differentiation of normal hyaline cartilage and reparative tissue after arthroscopic cartilage repair in equine subjects. Radiology 2006, 241, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Yin, H.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Ren, J.; Wang, K.; Han, D. Comparative analysis of the diagnostic values of T2 mapping and diffusion-weighted imaging for sacroiliitis in ankylosing spondylitis. Skeletal Radiol 2020, 49, 1597–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messroghli, D.R.; Rudolph, A.; Abdel-Aty, H.; Wassmuth, R.; Kuhne, T.; Dietz, R.; Schulz-Menger, J. An open-source software tool for the generation of relaxation time maps in magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Med Imaging 2010, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SourceForge. MRmap v1.4. Available online: https://sourceforge.net/p/mrmap/mailman/message/30100362/ (accessed on January, 2021).

- Albano, D.; Bignone, R.; Chianca, V.; Cuocolo, R.; Messina, C.; Sconfienza, L.M.; Ciccia, F.; Brunetti, A.; Midiri, M.; Galia, M. T2 mapping of the sacroiliac joints in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Eur J Radiol 2020, 131, 109246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, K.G.; Bollow, M. Magnetic resonance imaging of sacroiliitis in patients with spondyloarthritis: correlation with anatomy and histology. Rofo 2014, 186, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuite, M.J. Sacroiliac joint imaging. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2008, 12, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautry, R.; Bousson, V.; Manelfe, J.; Perozziello, A.; Boyer, P.; Loriaut, P.; Koch, P.; Silvestre, A.; Schouman-Claeys, E.; Laredo, J.D.; et al. Correlation of MRI T2 mapping sequence with knee pain location in young patients with normal standard MRI. Jbr-btr 2014, 97, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Chen, W.; Xu, X.Q.; Wu, F.Y. T2 mapping of the extraocular muscles in healthy volunteers: preliminary research on scan-rescan and observer-observer reproducibility. Acta Radiol 2020, 61, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüsse, S.; Claassen, H.; Gehrke, T.; Hassenpflug, J.; Schünke, M.; Heller, M.; Glüer, C.C. Evaluation of water content by spatially resolved transverse relaxation times of human articular cartilage. Magn Reson Imaging 2000, 18, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmueller, M.; Wuest, W.; Heiss, R.; Treutlein, C.; Uder, M.; May, M.S. Cardiac T2 mapping: robustness and homogeneity of standardized in-line analysis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2020, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | T1-weighted TSE | SPAIR TSE |

| Plane | Coronal oblique | Axial / Coronal oblique |

| TE (ms) | 8 | 80 |

| TR (ms) | 593 | 3431 |

| FOV (mm) | 200 | 200 |

| Flip angle (°) | 90 | 90 |

| No. of signal averages | 2 | 2 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 4 | 4 |

| Echo train length | 6 | 19 |

| Parameters | Multi-echo TSE |

| Plane | Axial oblique |

| TE (ms) | 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 |

| TR (ms) | 3825 |

| No. of echoes | 5 |

| Echo spacing (ms) | 20 |

| FOV (mm) | 200 |

| Flip angle (°) | 90 |

| No. of signal averages | 1 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 4 |

| Bandwidth (pixels) | 219 |

| Acquisition matrix | 268x265 |

| Acquisition time | 6.53 min |

| Acquired pixel resolution (mm) | 0.75x0.75 |

| Gender |

SpA Group (n=31) |

Control Group (n=25) |

Total (n=56) |

P Value |

| Female, n(%) | 15 (48.3) | 11 (44) | 26 (100) | >0.05 |

| Male, n(%) | 16 (51.7) | 14 (56) | 30 (100) | >0.05 |

| Age, Mean ± SD | 35.4 ± 13.0 | 37.2 ± 9.6 | 36.2 ± 12.0 | >0.05 |

| ASAS Criteria | n (%) | |

| Inflammatory Back Pain | 19 (61.2) | |

| Arthritis | 12 (38.7) | |

| Enthesitis | 4 (12.9) | |

| Uveitis | 2 (6.4) | |

| Dactylitis | 3 (9.6) | |

| Psoriasis | 2 (6.4) | |

| Crohn's/Ulcerative Colitis | 0 (0) | |

| Family history for SpA | 6 (19.3) | |

| HLA-B27 | Negative | 16 (51.6) |

| Positive | 7 (22.6) | |

| Unknown | 8 (25.8) | |

| Good Response to NSAIDs | No | 5 (16.1) |

| Yes | 12 (38.7) | |

| Unknown | 14 (45.2) | |

| CRP Level | <5 mg/L | 7 (22.6) |

| >5 mg/L | 24 (77.4) | |

| Active Sacroiliitis on MRI | 31 (100) | |

| SpA Group (n=31) | Control Group (n=25) | P Value | |

| T2 relaxation time - bone (ms)*, (Mean ± SD) |

100.23 ± 7.41 | 69.44 ± 4.37 | <0.001 |

| T2 relaxation time - cartilage (ms)**, (Mean ± SD) |

44.0 ± 3.19 | 43.2 ± 3.41 | 0.249 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).