1. Introduction

The Biliary tract cancer is a heterogeneous group of malignancies that includes intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder cancer, and ampulla of Vater cancer [

1]. Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is further classified into perihilar and distal cholangiocarcinoma according to their anatomical location [

1]. Despite recent advances in diagnostic technology, surgical resection, the only curative treatment, can be offered to up to one-quarter of patients [

2]. Most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage and are indicated for systemic chemotherapy, but the prognosis is poor [

3]. Furthermore, the incidence of biliary tract cancer, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in particular, is increasing globally, and it is problematic.

As first-line treatment for advanced biliary tract cancer, the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC) is a standard regimen based on positive results of two randomized trials [

4,

5]. The phase III trial ABC-02 showed an improved progression-free survival (PFS) of 8.0 months for patients treated with GC compared to 5.0 months for patients treated with gemcitabine monotherapy, with an accompanying improvement in median overall survival (OS) of 11.7 versus 8.1 months [

4]. Biliary tract cancer exhibits immunogenic features, including expression of the immune checkpoint molecules programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) in the tumor microenvironment [

6,

7]. Recently, the phase III TOPAZ-1 trial with 685 patients showed that the addition of immune checkpoint therapy using the anti-PD-L1 antibody durvalumab (D) in combination with GC increased patient survival [

8,

9,

10]. The median overall survival (OS) for patients receiving the GCD treatment was 12.8 months compared to 11.5 months for those receiving GC plus placebo, with a reduction in the risk of death of 20% in favor of the experimental arm.

The results of the TOPAZ-1 trial led to the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) approval of GCD therapy as the new first-line standard therapy for patients with unresectable or metastatic biliary tract cancer. In Japan, this combination therapy has been available since December 2022 in the real-world setting. Therefore, there is limited post-approval real-world data regarding its efficacy, safety, and predictive factors for response in Japan.

We performed a multicenter retrospective analysis with the aim to investigate the efficacy and safety of this new first-line standard treatment in a real-world setting. The predictive factors, including systemic inflammation-based prognostic indicators, were also investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

The Patients: Between January 2023 and May 2024, a total of 52 Japanese patients with advanced biliary tract cancer receiving GCD treatment at NHO Takasaki General Medical Center, Gunma Saiseikai Maebashi Hospital, and SUBARU Ota Memorial Hospital were included and none were excluded from the current retrospective study. Patients were diagnosed with biliary tract cancer based on typical radiological or pathological findings. The authors retrospectively examined the medical records, collected patient characteristics, and analyzed the outcomes, including the tumor response, OS, PFS, and adverse events (AEs).

The combination of durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin (GCD) treatment and the assessment of the tumor response and AEs: Patients were treated with durvalumab combined with gemcitabine and cisplatin administered intravenously in a 21-day cycle for up to eight cycles. Durvalumab (1500 mg) was administered on day 1 of each cycle in combination with gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) and cisplatin (25 mg/m2), which were administered on days 1 and 8 of each cycle. After completion of up to eight cycles of gemcitabine and cisplatin, durvalumab monotherapy (1500 mg) was administered once every 4 weeks until clinical or imaging disease progression or until unacceptable toxicity.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was carried out every 6-12 weeks. The tumor response was evaluated by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. The overall response rate (ORR) was defined as the sum of the complete response (CR) and partial response (PR). The disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the sum of the CR, PR, and stable disease (SD) rates. The OS was defined as the period from the day of initial GCD treatment to the day of death or last visit. The PFS was defined as the period from the day of initial GCD treatment to the day of the presence of disease progression or death. The performance status was evaluated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [

11]. AEs related to GCD treatment were assessed by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 [

12]. The serum levels of CEA and CA19-9 were measured at baseline and every 6 weeks interval. The ratio of tumor markers before administration to those 6 weeks after the start of administration was less than 1, which was defined as a decrease group, and 1 or more, which was defined as an increase group. The modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS) was determined as described previously [

13,

14]. Patients were stratified into 3 mGPS groups: mGPS 0 (CRP ≤0.5 and albumin ≥3.5 g/dL), mGPS 1 (CRP >0.5 mg/L or albumin <3.5 g/dL), and mGPS 2 (CRP >0.5 mg/L and albumin <3.5 g/dL). The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and CRP/Alb ratio were calculated. The prognostic nutritional index (PNI) was calculated as follows: PNI = [10 × serum albumin (g/dL)] + [0.005 × total lymphocyte count (/mm

3)]. These values were calculated immediately before the administration of GCD treatment.

Statistical analyses: Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages, and continuous variables are presented as the median (interquartile range [IQR]). Differences between groups were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test and the Mann-Whitney U test when a significant difference was obtained using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The prognosis was assessed using a Cox hazard analysis, the Kaplan-Meier method, and a log-rank test. All statistical analyses were undertaken using EZR version 1.61 (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University) [

16]. P-values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

Patient characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The median age of all patients was 73.0 (IQR 67.8-77.3) years old, and there were 36 (69.2%) men. The median body mass index (BMI) before GCD treatment was 21.9 (IQR: 19.7-23.7) kg/m

2. There were 36 cases of cholangiocarcinoma (distal: 10, perihilar: 19, intrahepatic: 7), 13 cases of gallbladder cancer, and 3 cases of ampullary carcinoma. Concerning tumor factors, 30 patients (57.7%) had local advanced disease, and 22 patients (42.3%) had metastases. There were 20 patients (38.5%) with postoperative recurrence. Biliary drainage was performed in 30 cases. The ECOG-PS distribution was 0, 1, and 2 in 43 (82.7%), 7 (13.5%), and 3 patients (5.8%), respectively. There were 38 cases (73.1%) receiving first-line therapy and 14 cases receiving second-line or later treatments. A history of first-line treatment with gemcitabine plus cisplatin (GC), GC plus S-1 (GCS), and gemcitabine was noted in 12 (23.1%), 1 (1.9%), and 1 patient (1.6%), respectively. The serum levels of CEA and CA19-9 at baseline were 4.8 (IQR 2.6-10.5) ng/mL and 255.9 (IQR 40.8-1014.3) U/mL, respectively.

3.1. The OS and PFS

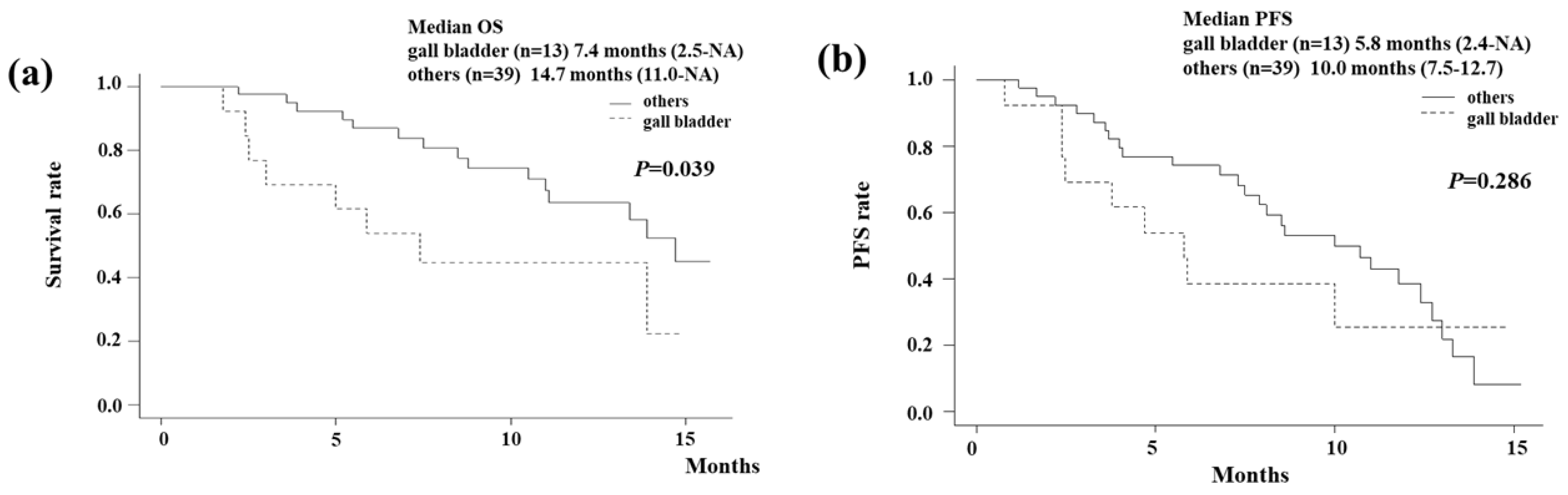

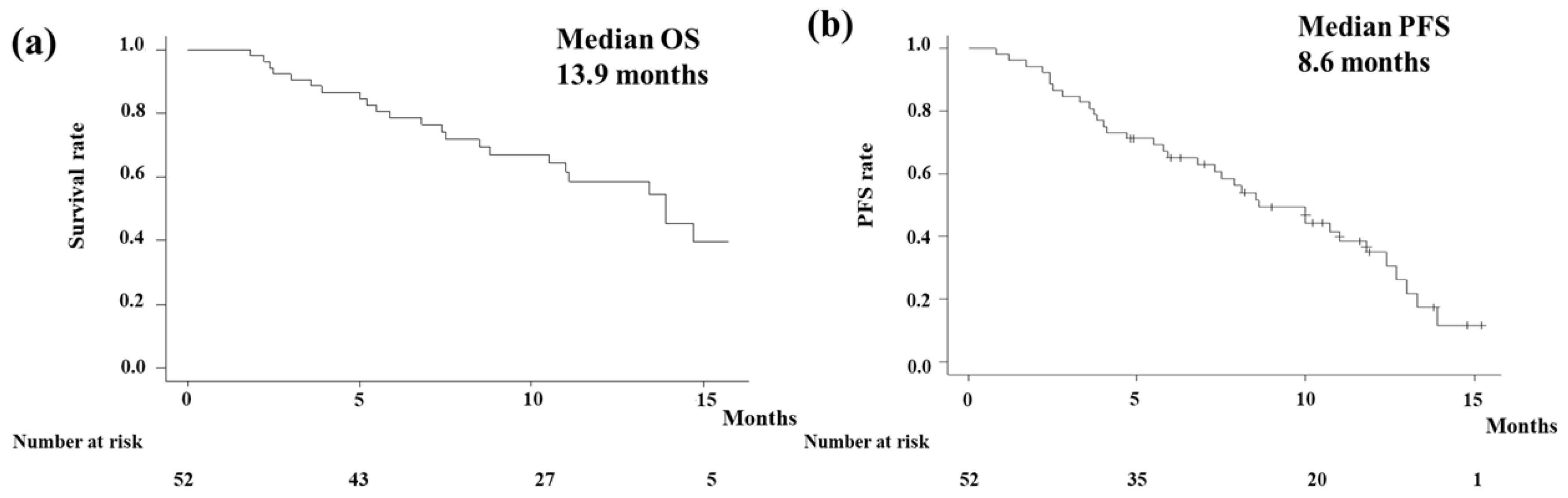

In the analysis of the OS, events occurred in 23 patients (44.2%) with a median follow-up period of 10.1 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 8.9-11.3 months). The Kaplan-Meier curve showed that the median OS of all patients was 13.9 months (95% CI 10.5-NA months;

Figure 1a).

Figure 1b shows the PFS of all patients. Events were observed in 33 patients (63.5%) in the analysis of the PFS. The median PFS in all patients was estimated to be 8.6 (95% CI 6.8-11.8) months. According to the primary tumor type, OS and PFS were shown in

Figure 2. The Kaplan-Meier curve showed that the median OS of gallbladder cancer was 7.4 months (95% CI 2.5-NA months;

Figure 2a). On the other hand, those of other cancers were 14.7 months (95% CI 11.0-NA months). The median OS of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (distal/perihilar), intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and ampullary carcinoma were (13.4/14.7), NA, and 7.4 months, respectively. Gallbladder cancer had a significantly poorer OS compared to other cancers (I=0.039). The Kaplan-Meier curve showed that the median PFS of gallbladder cancer was 5.8 months (95% CI 2.4-NA months;

Figure 2b). On the other hand, those of other cancers were 10.0 months (95% CI 7.5-12.7 months). Although it did not reach statistical significance, gallbladder cancer tended to have a poorer PFS compared to other cancers.

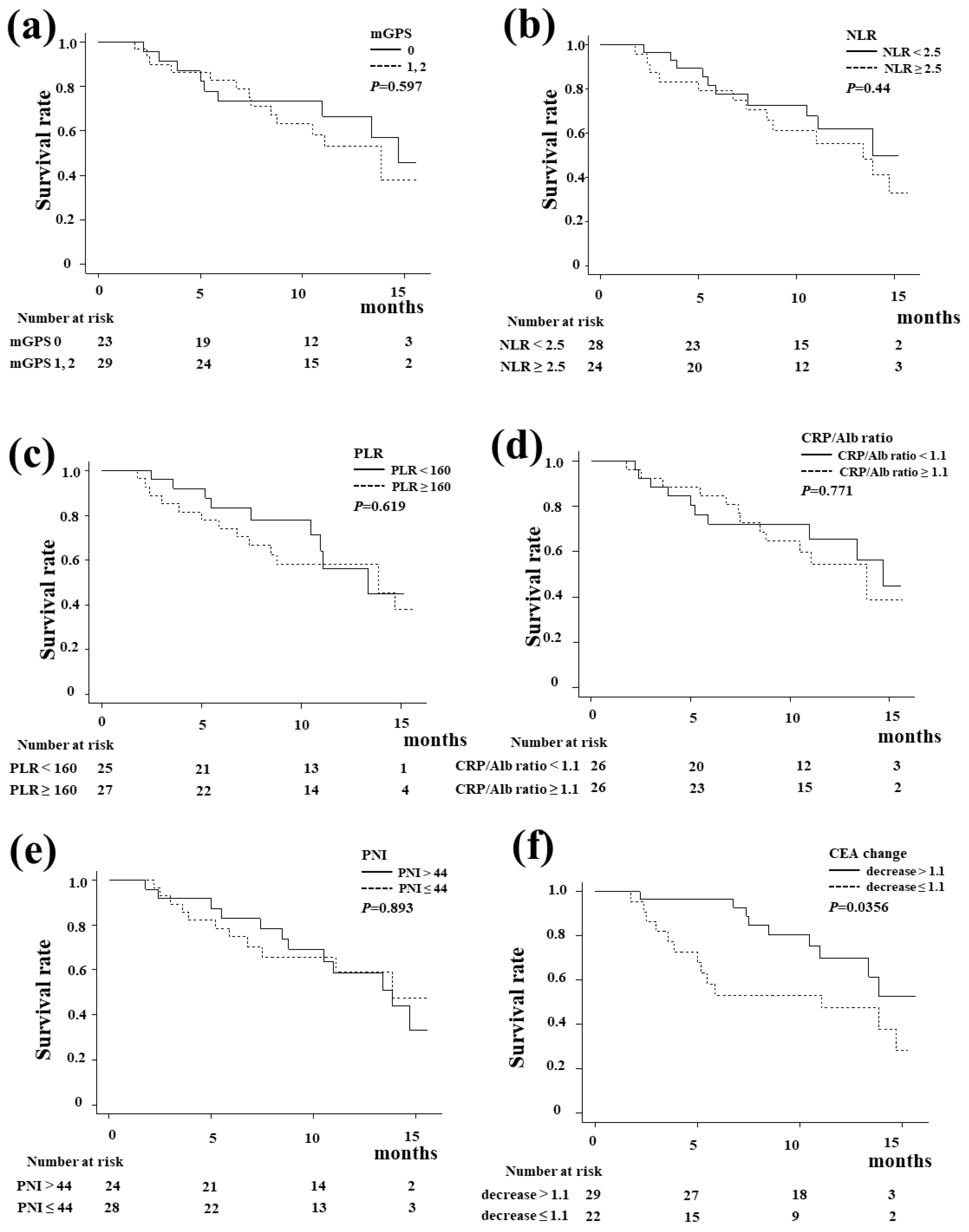

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of the OS according to the systemic inflammation-based prognostic indicators and tumor marker change. There were no significant differences in the OS regarding the mGPS score, NLR, PLR, CRP/Alb ratio, or PNI. A decrease in CEA at six weeks after the start of treatment was a significant predictor of OS (

P=0.0356).

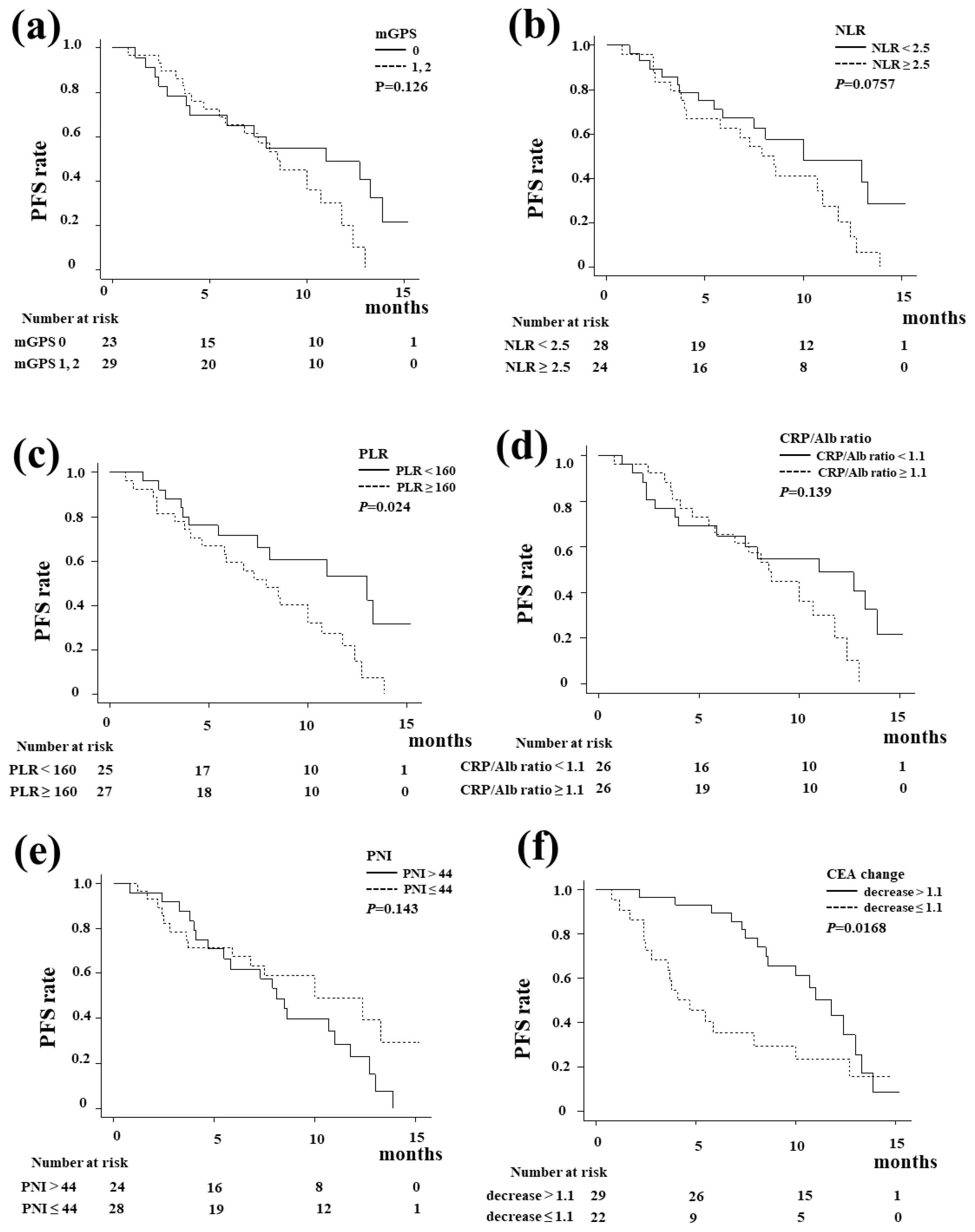

Figure 4 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of the PFS. The PLR (

Figure 4c,

P=0.024) was significantly associated with the PFS, whereas the mGPS, NLR, CRP/Alb ratio, and PNI did not influence the PFS. A decrease in CEA at six weeks after the start of treatment was also a significant predictor of PFS (

P=0.0168).

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of the OS according to the systemic inflammation-based prognostic indicators and tumor marker change. There were no significant differences in the OS regarding the mGPS score, NLR, PLR, CRP/Alb ratio, or PNI. A decrease in CEA at six weeks after the start of treatment was a significant predictor of OS (

P=0.0356).

Figure 4 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of the PFS. The PLR (

Figure 4c,

P=0.024) was significantly associated with the PFS, whereas the mGPS, NLR, CRP/Alb ratio, and PNI did not influence the PFS. A decrease in CEA at six weeks after the start of treatment was also a significant predictor of PFS (

P=0.0168).

3.2. The ORR and DCR

The results associated with the tumor response are shown in

Table 2. According to the RECIST, 2 patients (3.8%) had CR, 11 patients (21.2%) had PR, 28 (53.8%) had SD, 10 (19.2%) had PD, and 1 patient (1.9%) was not evaluable (NE). Thus, the ORR and DCR in all patients were calculated to be 25.0% (13/52) and 78.8% (41/52), respectively.

3.3. AEs

The AEs during GCD treatment are summarized in

Table 3. Adverse events were manageable, although neutropenia (42.3%), anemia (25.0%), thrombocytopenia (13.5%), and gastrointestinal symptoms such as dysgeusia, loss of appetite, nausea, and constipation were observed. The most frequent grade ≥3 AE was neutropenia, reported in 28.8% of patients, followed by anemia and general fatigue. Immune-related adverse events included hypothyroidism in 2 cases, cholangitis in 1 case, and colitis in 1 case. These 4 patients with immune-related adverse events were all grade ≥3.

4. Discussion

The main finding of the present study was that GCD therapy was considered to be an effective regimen for unresectable advanced biliary tract cancer even in clinical practice. The median PFS and OS of our cohort were 8.6 and 13.9 months, respectively. Those of the TOPAZ-1 trial were 7.2 months with PFS and 12.8 months with OS, respectively. In other words, this study demonstrated that results in a real-world setting can be comparable to those obtained in randomized controlled trials, which enrolled patients with better clinical characteristics. The treatment outcomes of this study were ORR 25.0% and DCR 78.8%. Those of the TOPAZ-1 trial were 26.7% with ORR and 85.3% with DCR. We were also able to demonstrate that the ORR and DCR results of this real-world study were comparable to the TOPAZ-1 trial [

8].

Biliary tract cancers are aggressive tumors known to be characterized by a scarce response to treatment. The ABC-02 trial reported an ORR of 26.1% and a DCR of 81.4% in patients with biliary tract cancer receiving cisplatin plus gemcitabine [

4,

5], and GC treatment contributed as a first-line regimen for more than 10 years. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have been used in various types of cancer, and their effectiveness has been reported. The first immune checkpoint inhibitor to be used in biliary tract cancer was the TOPAZ-1 regimen [

8,

9,

10], in which durvalumab was added to the standard GC treatment. The benefit of combining chemotherapy and immunotherapy in biliary tract cancers has recently been confirmed by the KEYNOTE-966 phase III study of pembrolizumab plus GC [

17].

The TOPAZ-1 study did not include ampullary carcinoma, and there were no data for ampullary carcinoma. This study included 3 cases of ampullary carcinoma. We could not confirm the result of the treatment effect due to the small number of cases. Further investigation is needed by adding additional cases in the future. In this study, we showed that gallbladder cancer had a significantly poorer prognosis compared to other cancers.

For predicting the treatment response, a decrease in CEA at six weeks after the start of treatment was a significant predictor of PFS and OS in this study. In other words, it is possible to predict the therapeutic effect at a relatively early term of treatment, which is clinically useful. The PLR showed a significant difference as a predictive factor for the PFS in the present study. Inflammation has been considered to play an essential role in cancer progression. A number of inflammation-based prognostic factors have been developed, including the GPS, mGPS, PLR, NLR, CRP/Alb ratio, and PNI [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. We evaluated these inflammation-based prognostic factors in this study. The PLR only showed a significant difference in the present study. A high PLR, indicating systemic inflammation and potential immunosuppression, is often associated with poorer outcomes in patients treated with ICIs [

24]. Lymphocytes and platelets play pivotal roles in the systemic inflammatory response, demonstrating crucial functions in tumor development, infiltration, and metastasis [

25]. Tumor cells employ various mechanisms to activate platelets, leading to the direct release of factors such as IL-1, thrombin, and endothelin, thereby promoting tumor angiogenesis and enhancing tumor migration and dissemination [

26]. A reduced lymphocyte count could result in an inadequate immune response, consequently exerting an adverse impact on the prognosis of patients with cancers [

25]. Neutrophils inhibit the immune response by lymphocytes, natural killer cells, or activated T cells [

27,

28]. Although the PLR only showed a significant difference in the present study, not only PLR but also NLR might have shown statistical significance if the number of patients and the observation periods were increased.

In the TOPAZ-1 study, the most common adverse events were anemia (48.2%), nausea (40.2%), constipation (32.0%), and neutropenia (31.7%) in the GCD group [

8]. In this study, neutropenia (42.3%), anemia (25.0%), and thrombocytopenia (13.5%) were similar. However, there were fewer referrals for gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, likely because these could be managed with antiemetics. In the TOPAZ-1 trial, grade ≥3 AEs included anemia (23.7%), neutropenia (20.1%), and thrombocytopenia (4.7%) [

8]. In this study, grade ≥3 AEs included neutropenia (28.8%) and anemia (5.8%). Neutropenia was common, but anemia and thrombocytopenia were less common compared to TOPAZ-1. Immune-related adverse events included hypothyroidism in 2 cases, cholangitis in 1 case, and colitis in 1 case. In the TOPAZ-1 trial, any immune-mediated adverse events were observed in 43/338 cases (12.7%), and hypothyroid events (5.9%) were most common, followed by dermatitis (3.6%), hepatic events (1.2%), and adrenal insufficiency (1.2%) [

8].

The current study had several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study, and the number of patients was relatively small. Although this is sufficient in terms of reporting early real-world clinical data, the examination of predictive factors is a future task as more detailed markers may be identified if the number of cases increases.

5. Conclusions

Our data mostly confirmed the results achieved in the TOPAZ-1 trial in terms of PFS, ORR, and safety, supporting the use of this combination in clinical practice. PLR and a decrease in CEA at six weeks were suggested to be potentially useful for predicting response. GCD therapy is an effective regimen for unresectable biliary tract cancer in real-world clinical practice.

Author Contributions

EK: SK, AN, and TH conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination. MI, HY, YS, TH, NK, NT and YY performed data curation. TH performed statistical analyses and interpretation. TU supervised the study. EK and SK drafted the text. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external sources of funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of National Hospital Organization Takasaki General Medical Center (TGMC2023-075) and each institution. It was conducted in compliance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before treatment, and this study received ethical approval for use of an opt-out methodology.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in association with this study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PD-L1 |

programmed death ligand 1 |

| GCD |

durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin |

| mGPS |

modified Glasgow Prognostic Score |

| NLR |

neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio |

| PLR |

platelet-lymphocyte ratio |

| ORR |

overall response rate |

| DCR |

disease control rate |

| PFS |

progression-free survival |

| OS |

overall survival |

| CTLA-4 |

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 |

| AEs |

adverse events |

| RECIST |

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| PNI |

prognostic nutritional index |

| BMI |

body mass index |

References

- Valle, J.W.; Kelley, R.K.; Nervi, B.; Oh, D.Y.; Zhu, A.X. Biliary tract cancer. Lancet. 2021, 397, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banales, J.M.; Marin, J.J.G.; Lamarca, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Khan, S.A.; Roberts, L.R.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020, 17, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.-S.; Lee, K.-W.; Heo, J.-S.; Kim, S.-J.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-I.; et al. Comparison of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma with hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Today. 2006, 36, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle, J.; Wasan, H.; Palmer, D.H.; Cunningham, D.; Anthoney, A.; Maraveyas, A.; et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010, 362, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okusaka, T.; Nakachi, K.; Fukutomi, A.; Mizuno, N.; Ohkawa, S.; Funakoshi, A.; et al. Gemcitabine alone or in combination with cisplatin in patients with biliary tract cancer: a comparative multicentre study in Japan. Br J Cancer. 2010, 103, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Arai, Y.; Totoki, Y.; Shirota, T.; Elzawahry, A.; Kato, M.; et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat Genet. 2015, 47, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbatino, F.; Villani, V.; Yearley, J.H.; Deshpande, V.; Cai, L.; Konstantinidis, I.T.; et al. PD-L1 and HLA class I antigen expression and clinical course of the disease in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; Aiwu, R.H.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.T.; Okusaka, T.; Vogel, A.; et al. Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, D.W.; Yoon, J.; Kim, T.Y.; Bang, J.H.; et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin plus durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced biliary tract cancer: an open-label single-center phase 2 study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022, 7, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; He, A.R.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.T.; Okusaka, T.; Vogel, A.; et al. Plain language summary of the TOPAZ-1 study: durvalumab and chemotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer. Future Oncol. 2023, 19, 2277–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oken, M.M.; Creech, R.H.; Tormey, D.C.; Horton, J.; Davis, T.E.; McFadden, E.T.; et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982, 5, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. NCI common Terminology Criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) ver 5.0. 2017. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- McMillan, D.C.; Crozier, J.E.; Canna, K.; Angerson, W.J.; McArdle, C.S. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) in patients undergoing resection for colon and rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007, 22, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, Y.; Iwata, T.; Okugawa, Y.; Kawamoto, A.; Hiro, J.; Toiyama, Y.; et al. Prognostic significance of a systemic inflammatory response in patients undergoing multimodality therapy for advanced colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2013, 84, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.R.; Cook, E.J.; Goulder, F.; Justin, T.A.; Keeling, N.J. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005, 91, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, R.K.; Ueno, M.; Yoo, C.; Finn, R.S.; Furuse, J.; Ren, Z.; et al. Pembrolizumab in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared with gemcitabine and cisplatin alone for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer (KEYNOTE-966): a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023, 401, 1853–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillian, D.C.; Crozier, J.E.; Canna, K.; Angerson, W.J.; McArdle, C.S. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) in patients undergoing resection for colon and rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007, 22, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Iwata, T.; Okugawa, Y.; Kawamoto, A.; Hiro, J.; Toiyama, Y.; et al. Prognostic significance of a systemic inflammatory response in patients undergoing multimodality therapy for advanced colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2013, 84, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.R.; Cook, E.J.; Goulder, F.; Justin, T.A.; Keeling, N.J. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005, 91, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.; Bosonnet, L.; Raraty, M.; Sutton, R.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Campbell, F.; et al. Preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio is an independent significant prognostic marker in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2009, 197, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruki, K.; Shiba, H.; Shirai, Y.; Horiuchi, T.; Iwase, R.; Fujiwara, Y.; et al. The C-reactive protein to albumin ratio predicts long-term outcomes in patients with pancreatic cancer after pancreatic resection. World J Surg. 2016, 40, 2254–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeguchi, M.; Hanaki, T.; Endo, K.; Suzuki, K.; Nakamura, S.; Sawata, T.; et al. C-reactive protein/albumin ratio and prognostic nutritional index are strong prognostic indicators of survival in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Pancreat Cancer. 2017, 3, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, S.; Song, D.; Zang, Y.; Hao, R.; Li, L.; Zhu, J. Prognostic relevance of platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in gastric cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1367990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkwill, F.; Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow. Lancet. 2001, 357, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, S.; Goldfinger, L.E. Platelet microparticles and miRNA transfer in cancer progression: many targets, modes of action, and effects across cancer stages. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, H.T.; Klassen, L.W.; Kay, H.D. Inhibition of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in vitro by autologous peripheral blood granulocytes. J Immunol. 1985, 134, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hag, A.; Clark, R.A. Immunosuppression by activated human neutrophils. Dependence on the myeloperoxidase system. J Immunol. 1987, 139, 2406–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).