Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

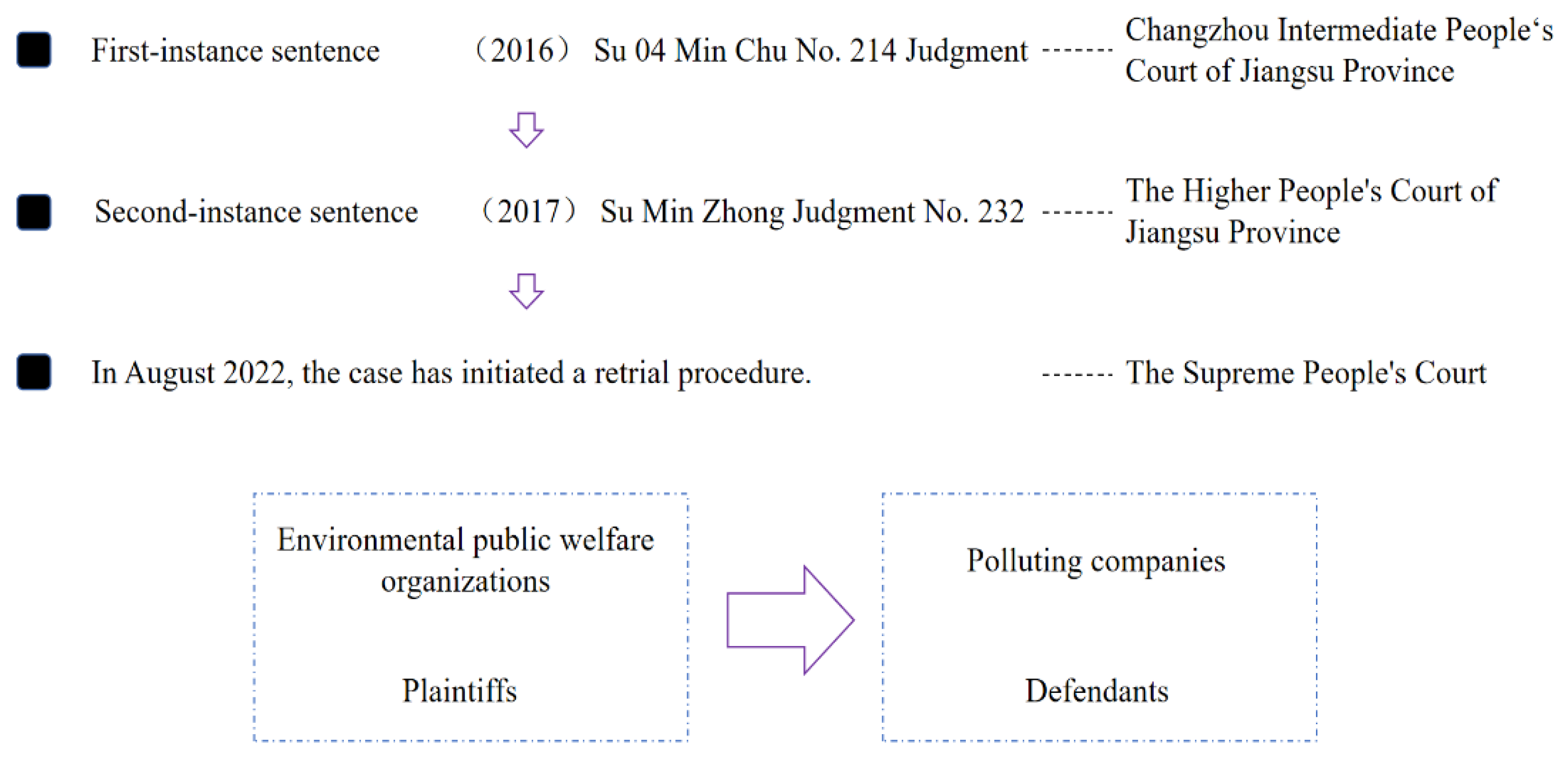

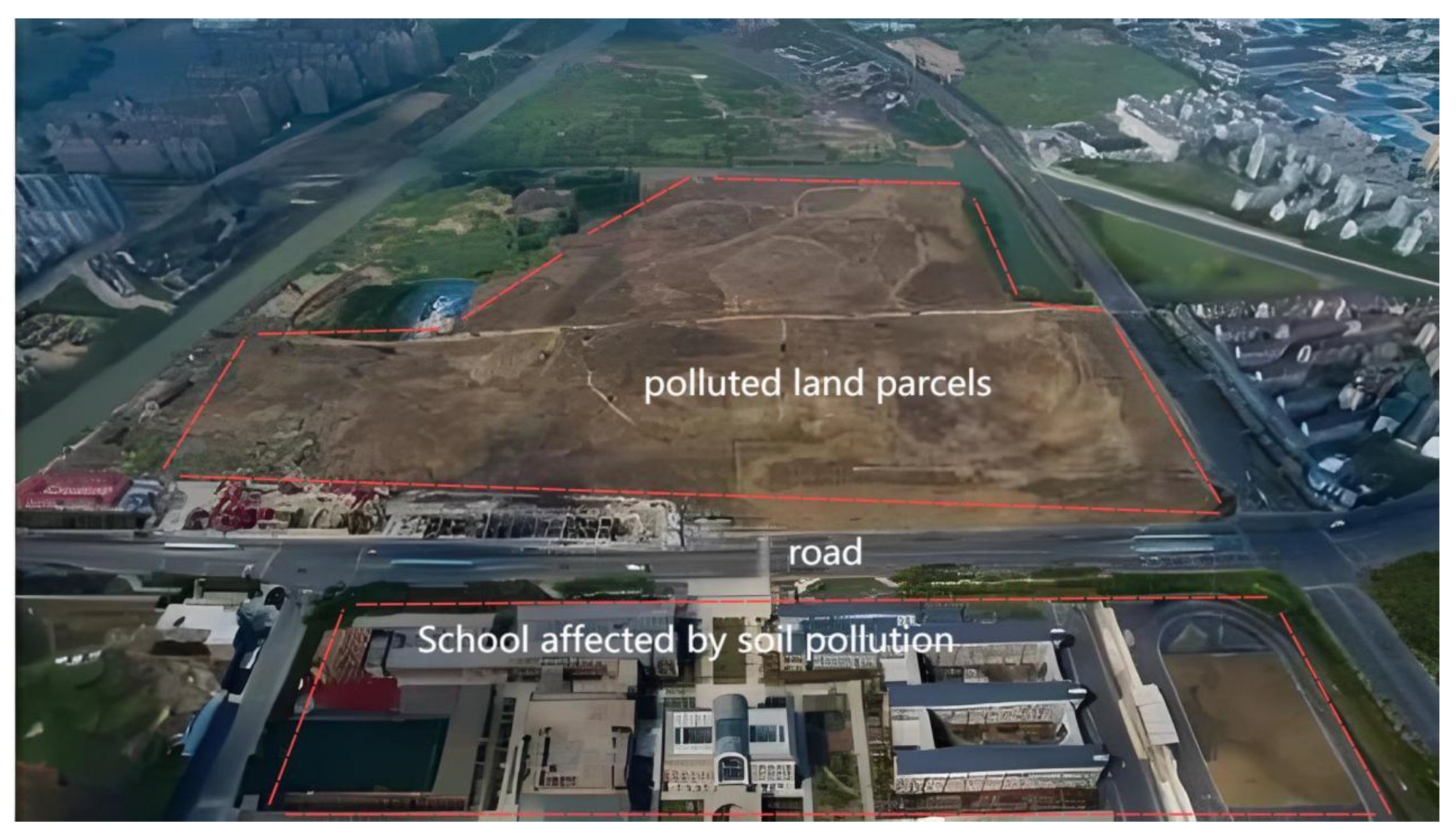

2.1. First-Instance Judgment

2.2. Second-Instance Judgment and Retrial

3. Results

3.1. The Myth of Legal Retroactivity and the Statute of Limitations

3.1.1. Incomplete Regulation of the Principle of Non-Retroactivity

3.1.2. Unclear Applicability Premises of the Three-Year Statute of Limitations

3.2. Practical Dilemmas in Legal Liability for Soil Pollution

3.2.1. The Disorderly Allocation of Responsibilities Between Public and Private Entities

3.2.2. Convergence of Environmental Legal Liability Types in Case Proceedings

4. Discussion

4.1. Special Application of the Principle of Retroactivity and Statute of Limitations

4.1.1. The Principle of Retroactivity in Environmental Law

4.1.2. Typological Differentiation of Statute of Limitations Rules

4.2. Soil Pollution Remediation System Under Public-Private Collaboration

4.2.1. Leveraging the Leading Role of Administrative Enforcement

4.2.2. Realizing Public Law Obligations Through Private Law Mechanisms

4.3. Liability Mechanisms Under a Systematic Environmental Litigation Framework

4.3.1. Clarifying the Legal Nature of Environmental Public Interest Litigation

4.3.2. Clarifying the Hierarchical Priorities of Environmental Public Interest Litigation

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Normative Construction of Soil Pollution Legal Liability

5.1.1. Codification Positioning of Soil Pollution Legal Liability

5.1.2. Codification of Soil Pollution Legal Liability

5.2. Practical Pathways for Soil Pollution Legal Liability

5.2.1. Differentiated Application of Retroactivity and Statute of Limitations

5.2.2. Identification of Soil Pollution Liability for Public and Private Entities

5.3. Judicial Reflections and Solutions for the Changzhou Toxic Land Case

5.3.1. Public-Private Collaboration in Soil Pollution Remediation

5.3.2. Resolving Retrial Challenges Through Systemic Thinking

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koul B., Taak P. Soil pollution: causes and consequences. Biotechnological Strategies for Effective Remediation of Polluted Soils. Springer, Singapore, 2018.

- Petrović Z., Manojlović D., Jović V. Legal protection of land from pollution. Екoнoмика пoљoпривреде, 2014, 3, 723-738. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/legal-protection-of-land-from-pollution (дата oбращения: 29.05.2025).

- Scullion, J. Remediating polluted soils. Naturwissenschaften 2006, 93, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan S., Naushad M., Lima E C., Zhang S X., Shaheen S M., Rinklebe J. Global soil pollution by toxic elements: current status and future perspectives on the risk assessment and remediation strategies – a review. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 417, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Drenguis D, D. Reap what you sow: soil pollution remediation reform in China. Washington International Law Journal 2014, 23, 171–201. https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol23/iss1/7.

- Xinhua News Agency. Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on Further Comprehensively Deepening Reform and Promoting Chinese path to Modernization. Available online: https://china.huanqiu.com/article/4IhSggVkMuj (accessed on 16 Jan 2025).

- He Y J., Wu D F., Li S C., Zhou P. Ecological and environmental risk warning framework ofland use/cover change for the belt and road initiative. Land, 2024, 13, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Cho, E R. The liability on the damage of soil pollution. Korean Society of Soil and Ground-water Environment 2005, 10, 1–9. https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO200509408769726.page.

- Globerman S., Schwindt R. Economics of retroactiveliability for contaminated sites. University of British Columbia Law Review, 1995, 29, 27-62. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?

- Zhao, Y.H. Contaminated land in china the legal regime and itsweakest links. University of Pennsylvania Asian Law Review 2020, 16, 150–212. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/etalr16&i=152.

- Feng L., Luo G Y., Loppolo G., Zhang X H., Liao W J. Prevention and control of soil pollution toward sustainable agricultural land use in China: analysis from legislative and judicial perspectives. Land Use Policy, 2025, 151, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Hall M W., Miyaji K. In search of new risk management strategies using a comparative eval-uation of environmental laws for soil contamination in the United States, Germany and Japan. IEEE Inte-rnational Engineering Management Conference (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37574) , 2004, 1, 27-31. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y. The impacts and implications of CERCLA on the Soil Environmental Conservation Act of the Republic of Korea. Transnational Environmental Law 2017, 6, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movchan R., Kamensky D. Criminal liability for soil pollution in Western Europe and Ukraine: a comparative study. Soil Security, 2024, 14, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev A S., Evdokimova M V. Approaches to the regulation of soil pollution in Russia and foreign countries. Eurasian Soil Science, 2022, 55, 641–650. [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu D. Soil Pollution and contamination, the lagal framework and actual trends in environmental policies. Annals of the University Dunarea de Jos of Galati: Fascicle II, Mathematics, Physics, Th-eoretical Mechanics, 2013, 36, 102-106. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=0ee780ff-62bd-3ead-8228-f9e7fe21d1f5.

- Ramón F., Lull C. Legal measures to prevent and manage soil contamination and to increase food safety for consumer health: The case of Spain. Environmental Pollution, 2019, 250, 883-891. [CrossRef]

- Montanarella L., Panagos P. The relevance of sustainable soil management within the European Green Deal. Land Use Policy, 2021, 100, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Betlem G., Faure M. Environmental toxic torts in europe: some trends in recovery of soil clean-up costs and damages for personalinjury in the netherlands, belgium, england and germany. GeorgetownInternational Environmental Law Review, 1998, 10, 855-890. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/gintenlr10&id=863&collection=journals&index=.

- Chigbu U E., Babalola T O. Unhiding the “land rights” and “land wrongs” in sub-Saharan Afr-ica: An interpretive scoping review. Land Use Policy, 2025, 154, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Tindwa H J., Singh B R. Soil pollution and agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa: State of the knowledge and remediation technologies. Front. Soil Sci, 2022, 2, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Slayi M., Zhou L., Dzvene A R., Mpanyaro Z. Drivers and consequences of land degradation on livestock productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic literature review. Land, 2024, 13, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Sam K., Zabbey N., Onyena A P. Implementing contaminated land remediation in Nigeria: Insights from the Ogoni remediation project. Land Use Policy, 2022, 115, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Hegazy S M A., Abdellaoui S., Ghannay T., Aboukhewat M G. Sustainable development and combating soil pollution in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (a foundational legal study). Journal of Human Security, 2024, 20, 87-93. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y C., Li Z Y. ‘Sharing’ as a critical framework for waterfront heritage regeneration: a case study of Suzhou Creek, Shanghai. Land, 2024, 13, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- (2016) Su 04 Min Chu No. 214 Ci-vil Judgment. Available online: https://cserl.chinalaw.org.cn/portal/article/index/id/375/cid/10.html (accessed on 18 Jan 2025).

- (2017) Su Min Zhong No. 232 Civil Judgment. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2781385 (accessed on 18 Jan 2025).

- The Supreme People’s Court will conduct a retrial of the “Changzhou toxic land case” on the morning of August 18th. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzAxOTExMzM4Mg==&mid=2649701660&idx=5&sn=ab6197230714a51ed320497fde3c2584&chksm=83d069d5b4a7e0c3e7b3119c8aa107d681205c036bfc339dd9f93efd64e9224408c7f25b157c&scene=21#wechat_redirect (accessed on 25 Jan 2025).

- Zhu, G H. Research on government environmental responsibility in China’s environmental go-vernance. China Social Sciences Press, Beijing. 2017.

- The Supreme People’s procuratorate has listed four cases of environmental pollution in Tengger Desert. Available online: https://www.spp.gov.cn/ztk/2015/sthj/dxal/201506/t20150616_99520.shtml (accessed on 25 Jan 2025).

- Qin, T B., Yuan Y S G. On the restricted application of punitive damages in environmental civil public interest litigation. Journal of Nanjing University of Technology (Social Sciences Edition), 2022, 21, 32-49+111. [CrossRef]

- Sun X H. Research on the traceability of law. China Legal Publishing House, Beijing. 2008.

- Wang H H. Retroactive liability in China’s soil pollution law: lessons from theoretical and comparatite analysis. Transnationa Environmental Law, 2020, 9, 593-616. [CrossRef]

- Vozza D. Historical pollution and long-term liability: a global challenge needing an international approach? In: Centonze, F., Manacorda, S. (eds) Historical Pollution. Springer, Cham. 2017.

- Peng Y Q. The current situation and improvement of judicial protection of spiritual interests in environmental infringement: an empirical analysis based on 16 judicial documents. Journal of Sichuan Police College, 2022, 34, 108-121. [CrossRef]

- Gao S P. Several issues in the legislation of statute of limitations for litigation. Legal Forum, 2015, 30, 28-36. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=qQX4xeHgc6sBa5EEutyUtTFAKY9xRbP8wfZirlddcQZwhgkLE-HZqK_GvH14pJoH2bSb5qShSvpZvVXUYxlfUe3pt8oA2FlnXItnP2_2xt_TWF9ZBi22yDDj9sq-k10O1kb7E_LfFVA7Z7LZeYODDiIl6DFz8teoG0rDSN03U7Z2ZrXWkwi4hs5E8WUY3YwwRQDtsOjlfk0=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Cheng Y. Selection of implementation mechanism for legal liability for ecological damage. China Social Sciences Press, Beijing. 2021.

- Persico C., Figlio D., Roth J. The developmental consequences of superfund sites. Journal of Labor Economic, 2020, 38, 1055-1097. [CrossRef]

- Hu J. The administrative leadership essence and enlightenment of ecological environment dam-age relief from the perspective of comparative law. Comparative Law Research, 2023, 3, 102-117. https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.3171.D.20230606.1435.004.

- Zhang B. The nature and positioning of the government compensation system for ecological environment damage. Modern Law, 2020, 42, 78-93. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=qQX4xeHgc6uX6OcpZbEwjioVYbkdkDZcXLFsKEy-W-3r4Vhbb4wttz9DYvPNkzej-1NzFpKyie6vVIZIadR356VA6u9ROYcQm0XebskJWoPI_X5rDzAHUMoPy9pq26eJ7R8pWg3h-hyiDd9bVkqWuWcjCKl7bDos2BCp3cyuzIad370GOsLOfJwLChTLX-6Zz0AZjAsI-IA=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Darracq E G., Brooks J J., Darracq A K. A national vision for land use planning in the Unit-ed States. Land, 2025, 14, 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Qin T B., Yang R K. On the path construction of positive interaction between procuratorial power and administrative power in administrative public interest litigation: from the perspective of impro-ving pre litigation procedures. Journal of Jiangsu Administrative College, 2023, 4, 122-129. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=qQX4xeHgc6sD-yOXdmtUTDqVbcqbZMS9y78fK17bBN80y40KRrUvZP8lvX78rSVWX2EDjc6rxr7euPmtt3t-2y6yMFtS8o9x5vy9iXOiJkiyfkPr7GWAOrSLofLyxJor9HSjxUajk7kHVauKNy5GZsmq9GNOxSx-zDt_mKAxSNi0poVaF4VJsWiEp7XTWhDtGBo7wAFs7MI=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Lv Z M. Analysis of environmental public interest litigation. Legal and Commercial Research, 2008, 6, 131-137. [CrossRef]

- Wang M Y. On the development direction of environmental public interest litigation in China: an analysis based on the theory of the relationship between administrative and judicial powers. Chinese Law, 2016, 1, 49-68. [CrossRef]

- Craig R K. Notice letters and notice pleading: the federal rules of civil procedure and the suff-iciency of environmental citizen suit notice. Oregon Law Review, 1999, 78, 105-202. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/orglr78&i=115.

- Adelman D E., Glicksman R L. The limits of citizen environmental litigation. Natural Resources & Environment, 2019, 33, 17-21. DOI: 27010525.

- Wang S Y., Li H Q. On the litigation of ecological environment damage compensation in China. Learning and Practice, 2018, 11, 68-75. [CrossRef]

- Cheng D W., Wang C F. The system positioning and improvement path of ecological environm-ent damage compensation system. Journal of the National Academy of Administration, 2016, 5, 81-85+143. [CrossRef]

- Judy M L., Probst K N. Superfund at 30. Vermont Journal of Environmental Law, 2009, 11, 191-248. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/vermenl11&i=195.

- Legislative Plan of the 14th Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Available online: http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c2/c30834/202309/t20230908_431613.html (accessed on 15 Feb 2025).

- World’s first! China’s procuratorial public interest litigation law form-ally starts legislative process. Available online: https://content-static.cctvnews.cctv.com/snow-book/index.html?item_id=15039571181457722818&toc_style_id=feeds_default&share_to=wechat&track_id=827e16ea -5b0e-4b51-98be-834986422fb8 (accessed on 15 Feb 2025).

| stage | government responsibilities | legal basis | types of illegal performance of duties | ways to assume environmental responsibility |

| before pollution occurs | supervise and administrate | article 7, article 8, etc. of the Solid Waste Pollution Prevention and Control Law; article 5, article 6, etc. of the Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law; article 4, article 9, etc. of the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law | incomplete action | administrative responsibility; political responsibility |

| after pollution occurs | conduct investigation and evaluation when collecting and storing land; imposing administrative penalties, ordering corrections, etc. on polluting behavior | the Land Reserve Management Measures, Jiangsu Provincial Land Reserve Management Implementation Measures, Jiangsu State-Owned Land Reserve Measures, Changzhou Municipal Land Reserve Management Measures, etc; chapter 8 of the Solid Waste Pollution Prevention and Control Law, chapter 6 of the Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law, etc | nonfeasance;incomplete action | |

| during pollution remediation | urge polluters to repair the environment, assume supervision and backup responsibilities | article 1234 of the Civil Code; article 5 of the Environmental Protection Law; articles 94, 95, etc. of the Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law | Illegally exercising powers |

| environmental civil legal liability | environmental administrative legal responsibility | responsibility for soil pollution remediation | |

| interest foundation | private environmental benefits | environmental public welfare | environmental public welfare |

| specific type | environmental infringement liability | the administrative legal responsibility that the counterparty should bear for violating environmental administrative norms | environmental public law responsibility based on public interest damage |

| responsibility attribute | private law liability | public law responsibility | Public law responsibility |

| natural order | the government’s order to rectify takes priority over the remediation responsibility of polluters, and the remediation responsibility of polluters takes priority over the government’s backup remediation responsibility | ||

| responsibility mode | stop infringement, eliminate obstruction, eliminate danger, restore the original state, compensate for damages, apologize, etc | stop illegal activities, impose administrative penalties, order correction, etc | restoration of ecological environment and compensation for ecological environment damage |

| legal basis | articles 1229-1233 of the Civil Code and related judicial interpretations | article 102, article 112, etc. of the Solid Waste Pollution Prevention and Control Law | articles 1234-1235 of the Civil Code, article 94 of the Soil Pollution Prevention and Control Law, etc |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).