1. Introduction

It is anticipated that human exploration of the Moon will evolve toward settlement of the Moon and that such settlement will require the exploitation of local lunar resources – in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU). Most interest has been focussed on water ice mining in permanently shadowed craters at the south pole supplemented by the use of local regolith as a construction material. These approaches assume minimum processing of the resource to render it useful. However, we are interested in building a lunar infrastructure from lunar resources to minimise the capital cost of launching infrastructure from Earth. This requires significant processing of lunar resources to yield functional materials. We do not cover activities associated with utilising regolith directly as a construction material such as the 3D printing of regolith [

1] or cements such as [

2] for civil engineering construction of lunar bases [

3] for which there are excellent reviews, notably [

4]. We concern ourselves with a specific approach to ISRU that yields a range of lunar mineral-derived materials including ceramics that have high utility rather than native lunar regolith. Most efforts have been focussed on the extraction of metals from lunar minerals but we shall consider the neglected ceramic resources on the Moon. It is expected that partial gravity on the Moon will have a negligible effect on processing methods compared with microgravity in orbit [

5] or milligravity conditions associated with asteroid processing [

6]. Nevertheless, the Moon imposes particular challenges due to its limited diversity of material resources and this will dominate the feasibility of manufacturing ceramics.

We explore the manufacture and exploitation of ceramics derived from lunar resources.

Section 2 defines the lunar industrial ecology as the context for exploring ceramics manufacture; section 3 explores thermal sintering and the problem of brittleness; section 4 explores ceramic 3D printing methods for the Moon and finds them wanting; section 5 introduces the importance of polymers; section 6 explores the use of clays; section 7 briefly looks at non-clay lunar mineral uses; section 8 concludes that polymers are an essential partner to ceramics and lunar industrialization will flounder until an alternative to polymers can be found.

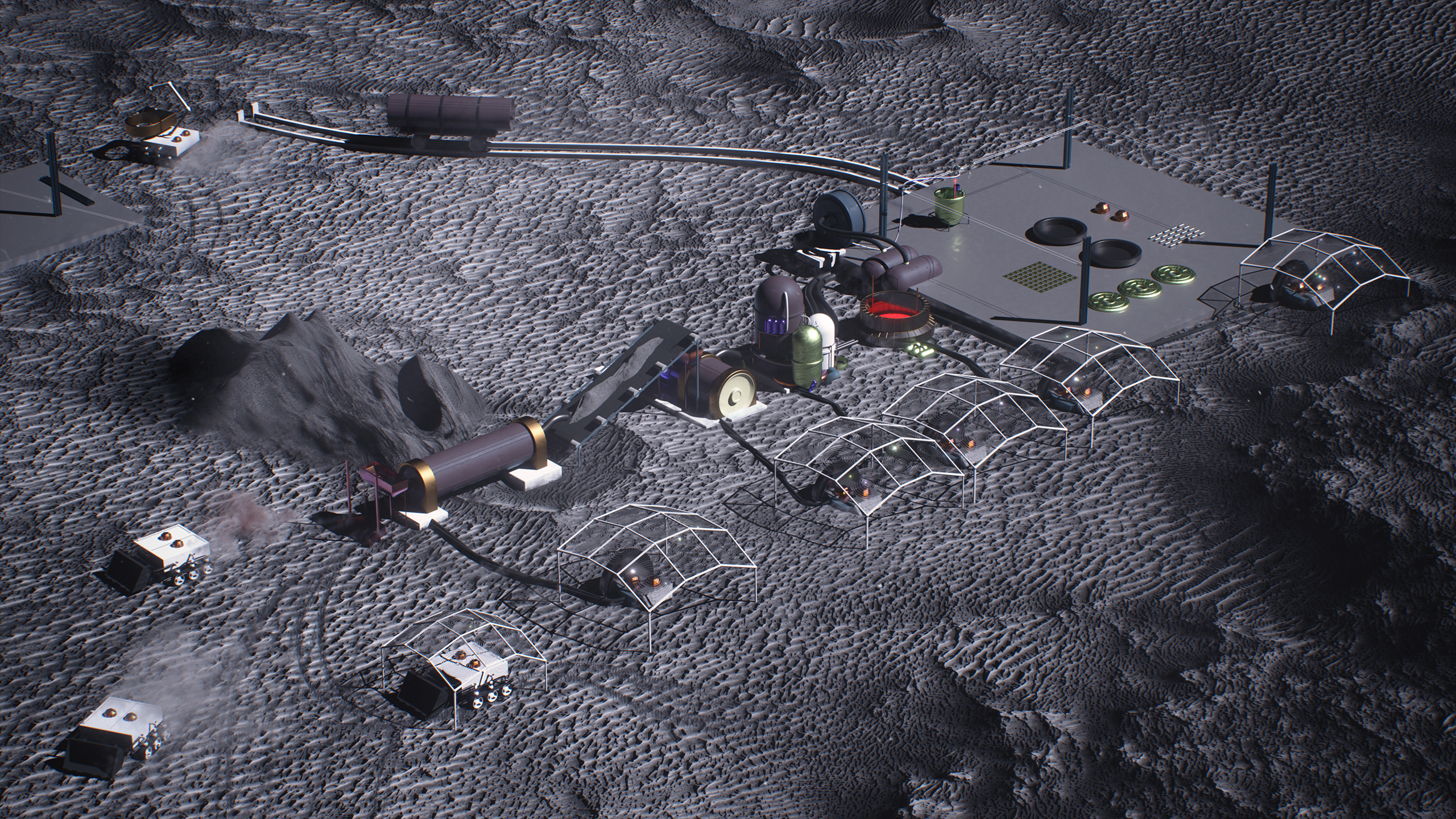

2. Circular Lunar Industrial Ecology

A circular economy for terrestrial industry is premised several properties that underlie the lunar industrial ecology: (i) maximum efficiency of mining, processing and production; (ii) recycling of waste to reduce pollution; (iii) refurbishment and repair of products to extend their useful lifetime. Energy efficiency is sacrificed in favour of material closure through recycling or re-use. We have adopted the same philosophy for the lunar industrial ecology [

7]. The guide for lunar resources is reflected in the Cheng’E-5 samples suggesting bulk abundance of SiO

2 (44.9%), Al

2O

3 (17.5%), FeO (12.2%), CaO (12.1%), MgO (8.8%), TiO

2 (2.5%), Na

2O (0.44%), Cr

2O

3 (0.27%), K

2O (0.11%) [

8] though they do not occur in pure oxide form. We limit ourselves to extracting only metals that exceed 1% average concentration though they exhibit higher concentrations in the commonest four lunar minerals – pyroxene, anorthite, orthoclase and ilmenite. Although there are only a handful of common rock-forming lunar minerals [

9], they may be supplemented by iron-nickel asteroid material from impactors [

10]. Our lunar industrial ecology is premised on such resources and we restrict ourselves to building with lunar resources but permit the import of reagents from Earth that are recycled but not consumed (

Table 1).

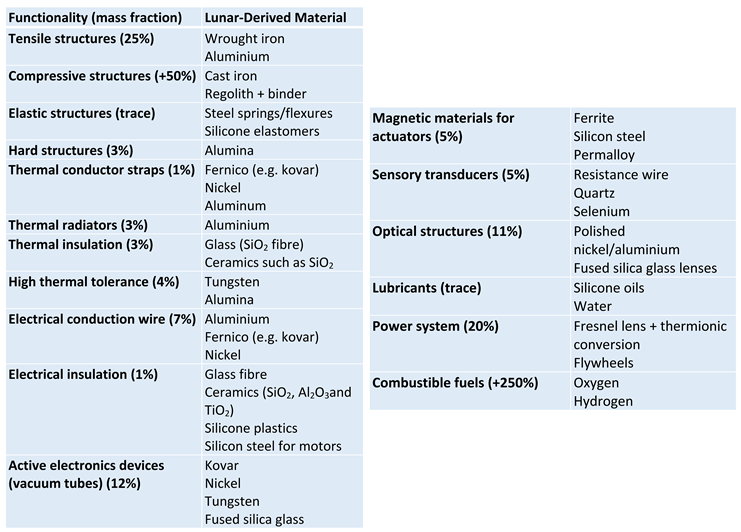

We can map the availability of processed lunar resources to the material functional requirements (demandite) of a spacecraft (

Table2).

We shall focus primarily on the core of the lunar industrial ecology – the processing of the lunar highlands mineral anorthite. We adopted a geomimetic approach - geomimetics involves inspiration from the synthesis of natural materials through geological processes such as hydrothermal vent processes at high temperature and pressure [

11]. We have exploited a geomimetic technique inspired by geochemical weathering by weak carbonic acid such as the dissolution of plagioclase feldspar into kaolinite and calcite [

12]:

CaAl2Si2O8 + H2CO3 + ½O2 → CaCO3 + Al2Si2O5(OH)4

Kaolinite may be converted into gibbsite via hydrolysis:

Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + 5H2O → 2Al(OH)3 +2H4SiO4

From silicic acid, silica may be precipitated. We adopted HCl acid leaching on anorthite (and other lunar minerals) as our “artificial weathering”. The first stage yields calcium chloride and precipitates silica from silicic acid:

CaAl2SiO8 + 8HCl + 2H2O → CaCl2 + 2AlCl3.6H2O + 2SiO2

Hydrous aluminium chloride is decomposed into aluminium hydroxide at 100oC with HCl partially recycled:

2AlCl3.6H2O → 2Al(OH)3 + 6HCl + 9H2O

Decomposition into alumina occurs at 400oC:

2Al(OH)3 → Al2O3 + 3H2O

We have demonstrated this process for the production of calcium chloride, alumina and silica from lunar highland simulant (LHS-1) that is dominantly anorthite [

13], i.e. we have utilised 100% of the anorthite mineral. Calcium chloride is feedstock as CaCl

2 electrolyte for molten salt electrolysis [

14]. Molten salt electrolysis requires much lower temperatures at 800-1000

oC than molten regolith electrolysis at 1650

oC. We have successfully demonstrated the reduction of alumina into 95% pure aluminium metal using molten salt electrolysis [

15].

Our concern here is with the ceramics we have produced – alumina and silica. Alumina and silica are applied to situations where high wear resistance, high corrosion resistance, high electrical resistance and high thermal stability are required. We shall illustrate the potential of these two materials in more exotic applications. The float glass technique involves spreading a layer of molten glass onto a bed of molten metal. Fused silica or quartz glass SiO

2, although it has a high melting temperature, is chemically inert. The typical additives of Na

2CO

3 and CaCO

3 for soda-lime glass for reduced melting temperature and for hardening respectively or B

2O

3 for borosilicate glass of low thermal expansion are not feasible on the Moon due to the paucity of Na and B but Al

2O

3 additives are feasible for aluminosilicate glass for high heat tolerance. Glass may be strengthened to reduce its shatterability by heating to a high temperature and cooling it rapidly so the exterior cools faster than the interior. The temperature gradient ensures that the outer surface is in compression while the inner core is in tension (tempering). It has been suggested that 20-25 m diameter heatshields of mass 40 tonnes for Earth re-entry at temperatures ~3000

oC may be fabricated on the Moon from sintered lunar silicates for the delivery of cargo [

16]. Silica extracted from anorthite provides a superior material for refractory heat shield tiles as used on the Space Shuttle. However, their adhesion was substandard. A 5:1 mixture of Al

2O

3:SiO

2 sintered at 1500

oC with a liquid aluminium dihydrogen phosphate (Al(H

2PO

4)

3.xH

2O) binder produces a high shear strength adhesive with high temperature tolerance [

17] that may be suitable. However, this is only feasible if we have access to phosphorus from KREEP (potassium rare earth elements phosphorus) basalt minerals on the Moon which are localised to the Procellarum region. We shall assume that this will be a possible scenario once lunar industrialisation has proceeded to maturity.

HCl “artificial weathering” is a general technique for yielding useful ceramics from lunar minerals. It may be applied to lunar forsterite to yield the ceramic magnesia:

Mg2SiO4 + 4HCl + 4H2O→ 2MgCl2 + 2H4SiO4

MgCl2 +2 NaOH → Mg(OH)2 + 2NaCl

Mg(OH)2 → MgO + H2O

The mare mineral ilmenite may be reduced in the presence of hydrogen at 1000oC to yield the ceramic rutile: FeTiO3 + H2 → Fe + TiO2 + H2O. Typically, the molten Fe metal is tapped at 1600oC (liquation) and the water electrolysed to recycle hydrogen and recover oxygen, leaving rutile. HCl “artificial weathering” may also be applied to lunar orthoclase as a source of kaolinite clay (Al2Si2O5(OH)4) via illite clay (KAl3Si3O10(OH)2):

3KAlSi3O8 + 2HCl + 12H2O → KAl3Si3O10(OH)2 + 6H4SiO4 + 2KCl

2KAl3Si3O10(OH)2 + 2HCl + 3H2O → 3Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + 2KCl

Similarly, lunar pyroxene such as augite may be artificially weathered to yield montmorillonite clay:

Ca(Fe,Al)Si2O6 + HCl + H2O → Ca0.33(Al)2(Si4O10)(OH)2.nH2O + H4SiO4 + CaCl2 + Fe(OH)3

In fact, acid weathering of pyroxenes at pH~3-4 proceeds more rapid than of feldspar so basalt is enriched in feldspar on Mars [

18]. Montmorillonite is an expanding clay unlike illite and kaolinite and is the primary ingredient in bentonite: (i) viscous agent in drilling mud; (ii) binder in sand casting - green sand is sand mixed with bentonite clay and water; (iii) absorbent (montmorillonite and kaolinite) in Fuller’s earth as a cleaning agent; (iv) feldspar and kaolinite may be supplemented by bentonite to form pottery. We shall focus on the processing of alumina, silica, magnesia, rutile and exploitation of clays as the ceramic resources available on the Moon. In doing so, we emphasise the multitude of useful properties these ceramics possess that make them so useful on the Moon as a complement to metals.

3. Thermal Sintering of Lunar-Derived Ceramics

The most significant problem with processing of ceramics is their hardness and brittleness at room temperature (an exception being Si

3N

4 which is plastic at room temperature under compressive loading [

19]). Ceramics are typically formed through moulding, casting and machining but 3D printing offers an alternative mode of manufacturing. Subtractive processing of ceramics is commonly accomplished through water jet pressurised to 300-600 MPa laden with an abrasive such as alumina which can implement cutting, drilling, shock peening and surface structuring. For constructive processing, dry ball milling is the approach for processing single ceramic powders or mixing powders for composites. Thermal sintering involves bonding of particles at ¼-¾ of the melting point. For ceramics, thermal sintering requires sintering temperature from 1000-2000

oC range. Reducing such temperatures to 1150

oC requires reducing particle sizes ~10-100 nm by milling using grinding balls <1 mm in diameter and the use of additives such as <0.2% CaO and SiO

2 to inhibit grain growth [

20]. Selective laser sintering/melting (SLS/M) cannot be employed for direct ceramic melting because of their high melting points so a polymer, metal or glass binder of lower melting point is required to bind the ceramic particles. One of the chief challenges to direct thermal sintering is the thermal gradients introduced with generate cracks and brittleness. The chief advantage of direct thermal sintering on the Moon is that it requires no reagents and direct solar energy may be concentrated to high temperatures using Fresnel lenses [

21].

To obviate high temperature >1000

oC ceramic processing, there are alternative approaches that may be exploited at lower temperature – hydrothermal sintering at high pressure for densification which requires aqueous solution [

22]. Hot pressing under high temperature and pressure may be used to sinter particles into a 3D part with homogeneous microstructure. Artificial lithification is a hydrothermal press that compacts loose particles of anhydrous cement at 250

oC and 345 MPa with water into sedimentary rock [

23]. Application to crystalline quartz or silica gel with aqueous NaOH solution to improve aqueous dissolution/precipitation reduces the required pressure to 20 MPa [

24]. Hydrothermal hot pressing has been demonstrated for alumina, geopolymers, glasses, silica, titania and kaolinite clays. Subjection of nanosized alumina powder with silica gel to 4.5-5.0 GPa at room temperature yielded densified alumina and silica with hardness of 5.7 GPa and 4.0 GPa respectively [

25]. Cold sintering involves lower applied pressures <1 GPa and modestly elevated temperatures <350

oC by adding aqueous NaOH solution for lubrication of nanosized ceramic powders as a supersaturated solution but this has yet to be demonstrated for alumina, silica or magnesia. Hence, hot hydrothermal synthesis under high pressure appears to be a viable approach to densification of ceramics on the Moon.

One of the chief challenges to machining ceramics is their hardness and brittleness so a major consideration is the introduction of durability to ceramics. Itacolumite sandstone is a highly flexible rock characterised by angular grain boundary microcracks that may be emulated by sintered aluminium titanate (Al

2TiO

5) powder [

26]. Flexibility with flexural strength of 13 MPa is enhanced by higher sintering temperature and sintering time with optimal values of 1550

oC and 12h respectively. Given the availability of TiO

2 on the Moon through hydrogen reduction of lunar ilmenite, this represents an unexplored material option for manufacturing aluminium titanate. Ceramic foams can utilise the superelasticity of alumina Al

2O

3 dispersed with 30% magnesia MgO which suppresses grain growth of alumina [

27]. Although the ductility of MgO dispersed alumina is inferior to that of 3% yttria-stabilised zirconia, the former can be manufactured from lunar resources and expanded into dense shells. This is unexplored. Ceramic superplasticity occurs in some fine-grained ceramics (ZrO

2, Si

3N

4 and SiC) at high temperature ~1500

oC through grain boundary sliding of intergranular glass phases [

28]. This requires a grain size <1 μm at high temperature [

29]. The application of an electric field can reduce the viscosity of such glass phases making the ceramic more plastic [

30]. Both these approaches of high temperature and applied electric fields are impractical. Borrowing dislocations in ceramics introduces metals with ceramic through sintering to permit dislocations at metal-ceramic interfaces to enhance ceramic plasticity, e.g. Mo metal applied to La

2O

2 ceramic [

31]. Sintered porous Si

3N

4 structures can be infiltrated by molten 6061-Al alloy under high pressure to enhance their fracture toughness [

32]. Indeed, the addition of 10% Fe to lunar regolith simulant improved the density of thermally sintering blocks at 1035

oC by reducing cracks yielding a compressive strength of 150 MPa and tensile strength of 20 MPa [

33].

Ceramic matrix composites comprise a ceramic matrix impregnated with glass or metal fibres ~10

-3 mm to impart non-brittleness. Alumina has high hardness, resistance to corrosion and wear, and high thermal conductivity. Alumina particles may be employed as a reinforcement in aluminium metal composites with optimal stress/strain properties of the composite favoured by small particle size <10 μm, higher sintering temperature at 600

oC over a 60-minute sintering time [

34]. An 80% alumina matrix with a uniform distribution of 20% nickel-iron superalloy steel particles may be fabricated using laser powder bed fusion at 1370

oC [

35]. It exhibited porosity even after thermal sintering due to poor adhesion between steel and alumina and insufficient melting of alumina. Polymer impregnation improved compressive strength from 56 to 120 MPa. Similarly, digital light processing followed by spark plasma sintering at 1050

oC under 50 MPa pressure to remove a polymer binder has demonstrated the manufacture of fully dense functional grading of metal powder-regolith material [

36]. NanoSiO

2 particle reinforcement may be incorporated into composites to extend their mechanical properties [

37]. Bioinspired organic-inorganic materials offer high thermal stability with plastic mouldability, e.g. ceramic CaCO

3 with organic thioctic acid (TA) polymerised through S-S bonds formed by adding CaCO

3 to an ethanol solution of TA [

38]. Similarly, CaCO

3 nanoparticle-based may be crosslinked with polyacrylic acid to form a hydrogel which is stretchable, shapeable and self-healable [

39]. Unfortunately, these materials require organic constituents.

4. 3D Printing of Lunar-Derived Ceramics

Traditionally, ceramic parts are manufactured by casting of slurries in moulds that are then cured and sintered but such parts cannot assume complex geometries. 3D printing of ceramics may be accomplished through fused deposition modelling (FDM), selective laser sintering (SLS), stereolithography (SLA), direct ink writing (DIW) and binder jetting [

40]. FDM is an extrusion technique that prints from a ceramic powder-impregnated thermoplastic filament that is melted and extruded. The thermoplastic is typically PLA or ABS but other higher performance polymers are possible such as PEEK. PLA is notable because it can be derived from corn starch. Binder jetting is similar in that powdered ceramic is sprayed with polymer but the binder is removed through polymer debonding at 280-650

oC followed by thermal sintering at 1400-1500

oC [

41]. Al

2O

3 is commonly printed with polymer and sintered in this way. A broad distribution of Al

2O

3 particle sizes yields higher densities and reduced shrinkage on sintering [

42]. The use of such additives is common in FDM but the quality of the parts printed is limited and unsuited to huge performance applications such as high temperatures as the matrix does not permit exploitation of the ceramics. Fibre-reinforced composites comprising high elasticity fibres within a ceramic matrix such as alumina or silica compensate for brittleness in ceramics whilst retaining their high strength-to-weight ratio and resistance to corrosion and high temperature. Most commonly, the fibre material is SiC or graphite but silica and alumina may be employed as fibres. Additive manufacturing of such composites favours the adoption of short fibres over continuous fibres where 3D printing of the preformed composite is printed followed by debinding and sintering [

43]. As with ceramic 3D printing, 3D printing may be through SLA, FDM, BJ, DIW or SLS. The adoption of ceramic fibres coated with nanophase iron permits the magnetic alignment of the fibres prior to SLA curing of polymer matrix composites (magnetic 3D printing) [

44]. However, there remain challenges with poor bonding at fibre-matrix interfaces compared with traditional composite manufacturing.

Terrestrially, the most promising and versatile mode of 3D printing of ceramics is direct ink writing (DIW) or robocasting. DIW involves the extrusion of a non-Newtonian (shear-thinning) fluid polymer binder loaded with powder at high density >50% such as a colloidal paste to print 3D parts following sintering. The ink is designed with a yield stress described by the Herschel-Bulkley model:

where τ=applied shear stress, τ

γ=yield stress,

=shear rate, K=viscosity, n=degree of shear thinning (n=1 for Newtonian fluids). During extrusion, shear-thinning is necessary, i.e. a decline in viscosity at higher shear rates to prevent clogging. Beyond τ

γ, shear thinning is described by a power law,

. The 10-50 μm powder may be metal, polymer or ceramic but the binder is an organic polymer with additives. Typical polymers are much more complex than FDM polymers and include formaldehyde-phenol-urea, polycarboxylic acid, polyethylene glycol or polyvinyl acetate. For example, the hydrogel Pluronic F-127 comprises a 2:1 mix of polyethylene oxide and polypropylene oxide provides both hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties. The paste must also include additives such as surfactants and dispersants to disperse the particles and prevent particle aggregation such as stearic acid [

45]. After deposition, shape retention requires viscosity to increase as shear decreases. Thermal debinding at 200-600

oC removes the binder and must be slow to prevent crack formation followed by thermal sintering at 1200-2000

oC which generally yields 10-20% part shrinkage. Ceramic powder – suluca, basalt, etc must be highly loaded into the slurry te reduce shrinkage after sintering. Ceramic powder comprises ~40-50% suspensions in the polymer fluid (inks) that are extruded as filaments flowing with decreased viscosity at increased shear [

46]. The loading of solid powders imposes the need for larger nozzles than inkjet printing ~400-800 μm – this is because inkjet adopts low ceramic loading (<30%) in suspension for low-viscosity ink compared with high ceramic loading (<60%) for high-viscosity pastes for extrusion or SLA [

47]. Inkjet printing is suited to ceramic nanoparticle suspensions in an ink characterised by an inverse Ohnesorge number of 1-10 but only simple structures can be printed in this way. Alumina is an ideal ceramic with high hardness, high compressive strength and resistance to both corrosion and wear that is also thermally and chemically stable at sintering temperatures. Ideal alumina loading is 53-56% with 2% Al metal to minimise shrinkage [

48]. Sintering at 1550

oC yields ceramic parts of Al

2O

3 with 98% density. The addition of 3-7% carbon nanotubes imparts electrical conductivity to non-conducting alumina. 70% regolith simulant powder may be mixed with 30% polylactic-co-glycolic acid and other additives such as dichloromethane to form an ink that may be 3D printed into rubber-like structures with E=1.8-13 MPa and 250% strain [

49]. Although monomers glycolic acid and lactic acid are derivable from urine, the additives are not so readily manufactured from lunar resources. Multi-material 3D printing may be implemented by DIW through the extrusion of different inks with different functional properties [

50]. The delivery of multiple composite inks may be through a single paste cartridge or multiple cartridges. Complex parts may be manufactured by DIW such as gears, electrical components and sensors. Carbon nanotube or graphene in inks can form carbon networks in silicone elastomer matrices whose conductivity responds to pressure and/or temperature.

All these approaches to 3D printing ceramics and/or composites require the use of polymer binders which present major challenges for deployment of the Moon. However, even if carbon sources can be found, the use of DIW is not feasible because it requires careful tailoring of inks which require an Earth-based infrastructure to realise.

5. Problem of Polymers

Carbon is scarce on the Moon at ~120 ppm embedded in regolith by solar wind impregnation. There are other possible options. It is expected that concentrated asteroidal resources have been deposited into the Moon’s surface by impacts [

51,

52]. A 1 km diameter carbonaceous chondrite striking the Moon at speeds ≤10 km/s and impact angles ≤15

o favour 85% survivability of C-rich (~10

9-10

10 kg) and N-rich (~10

8-10

9 kg) solids ~20-30 km downrange of the impact site over a 60 km

2 area within <10 m of the surface [

53]. Such impacts at <15

o and <10 km/s by C-type asteroids are rare ~5 impacts in the last 3 By but still yield greater C and N concentrations than solar wind impregnation of a typical permanently shadowed crater with ~6x10

5-6x10

8 kg C and N equally. Smaller impactors ~0.1 km would be more common ~500 delivering ~6x10

2-6x10

5 kg C and N equally for each impactor. They may present themselves through their phyllosilicate signature. The identification of graphite in Apollo 12 and Apollo 17 samples provides evidence of the survival of carbonaceous asteroid impacts favoured by porosity, obliquity and low velocity [

54]. The Yutu-2 rover of Chang’e 4 has discovered glassy material in a small 2m diameter crater with a high 47% concentration of carbonaceous chondrite remnant from an impactor [

55]. So, asteroid material may exist on the Moon but, if not, asteroids may be maneouvred into lunar orbit and undergo a controlled descent to the lunar surface [

56]. Once the asteroid has soft-landed on the Moon, it may be subject to processing under the Moon’s gravity field. The latter scenario of asteroid maneouvring is not technologically feasible in the near-term. Otherwise, the use of polymers requires its transport from Earth which imposes a high transport burden. We examine two scenarios: (i) recovery of diffuse solar-wind implanted carbon volatiles so small quantities are available; (ii) discovery of asteroid-delivered carbon source presenting copious amounts of carbon permitting the manufacture of simple polymers.

In case (i), we have a restricted supply of carbon that must be husbanded and consumed frugally – one possibility is to synthesise polymers that use carbon only in its side chains but not its backbone. Inorganic silicone polymers are dominated by siloxanes with Si-O-Si backbones such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as well as related materials such as polysilazanes with Si-N-Si backbones. However, N is rarer than C on the Moon ruling out the latter. Siloxanes (silicones) may be manufactured from syngas through the Rochow process via methanol [

57]. Silicone can act as binder for ceramic powders and a source of silica in the sintered ceramic part. Silicones have high temperature tolerance ~300

oC and high UV-resistance compared with C-C bond polymers. Preceramic polymers permit 3D printing of the polymer into complex parts which is then converted into a ceramic through pyrolysis (ceramisation) at 600-1000

oC in an N

2 atmosphere which decomposes the organic component [

58]. Silicone-based pre-ceramic polymer precursors can be 3D printed as extruded polymer and then cured into a SiOC ceramic by vacuum pyrolysis at 1100

oC after deposition. The printed SiOC has a compressive strength of 240 MPa. Pyrolysis in O

2 yields the formation of silicate ceramics by eliminating the carbon required for carbide formation. Silicones reduce the consumption of carbon but nevertheless do consume carbon requiring recovery of CO/CO

2 during pyrolysis for recycling. Metallosiloxanes such as titanosiloxanes are silicones with metals in the polymer backbone Ti-O-Si formed from TiO

2 at temperatures >900

oC [

59]. They can act as zeolites. Aluminosiloxanes are inorganic polymers based on Al-Si-O backbone but are manufactured from

complex precursors [

60]. The aluminosiloxane Al(O’Pr),(OSiMe

3) may be an organic precursor of 92Al

2O

3-8SiO

2 ceramic [

61]. However, complex precursors rule out aluminosiloxanes. Silicones and titanosilicones may be manufacturable in small quantities for specialist applications.

In case (ii), we can assume that a plentiful carbon source has been discovered and that we can synthesise simple plastics. The initial reactions for polymer synthesis from syngas to methanol are the same as for the Rochow process. We focus on synthesising transparent PMMA (polymethyl methacrylate) which has versatility of uses including as a tough acrylic glass, as a resist in electron beam lithography and, most relevant here, transparent liquid MMA monomers can act as UV photopolymer in SLA. Although manufacture of both PMMA and its photoinitiator require a source of N which we expect to be available with C from carbonaceous chondrite deposits. Syngas may be converted to methanol using an alumina catalyst at 200-300oC and 50-100 bar:

CO + 2H2 → CH3OH

Methanol is converted to acetone through dehydrogenation:

2CH3OH → CH3COCH3 + H2O + H2

Acetone reacts with HCN to yield acetone cyanohydrin (ACH):

CH3COCH3 + HCN → (CH3)2C(OH)CN

ACH is converted to transparent liquid MMA using H2SO4 at 80-120oC:

(CH3)2C(OH)CN + CH3OH + H2SO4 → CH2=C(CH3)COOCH3 + NH4HSO4

UV-initiated (benzoin initiator) polymerisation of MMA at 25-60oC yields PMMA:

–[CH2-C(CH3)(COOCH3)-]n.

MMA monomer acts as a UV photopolymer by hardening into PMMA in the presence of the photoinitiator benzoin. Benzoin synthesis begins with conversion of methanol-to-benzene in the presence of a zeolite catalyst at 400-500oC:

6CH3OH → C6H6 + 6H2O

Zeolites are tetrahedral MO4 units where M=Si or Al that act as selective catalysts. Benzene is converted to benzaldehyde through the Gattermann-Koch reaction using an AlCl3 catalyst:

C6H6 + CO + HCl → C6H5CHO

Benzoin condensation proceeds using an HCN catalyst:

2C6H5CHO → C6H5CH(OH)COC6H5

Hence, we have the UV-photopolymer PMMA with its benzoin photoinitiator to permit the use of SLA. Refractory ceramic powder ~μm size such as silica or alumina may be dispersed at 50-65% by volume in a UV acrylate photopolymer (such as MMA) with photoinitiator (such as benzoin) and subjected to 150-200 μm layered stereolithography by UV laser [

62]. Curing depth reachable by the UV laser

where n=refractive index difference between ceramic and solution derived from the Beer-Lambert law. The photopolymer binder is removed to reveal the ceramic part. Reduced gravity or microgravity imposes criticality to the rheological properties of the ceramic slurry of 50% Al

2O

3 particles in a UV-curable glycol dimethylacrylate resin with a photoinitiator [

63]. It behaves as a Bingham fluid in which low shear stress yields high solid-like viscosity but there is a threshold shear stress that acts as a plastic yield stress. The viscoelasticity of the fluid is increased into a paste by 0.5% cellulose - cellulose is a single additive that can act as dispersant, plasticiser and coagulant that is derivable from vegetation. UV photopolymerisation builds the part layer-by-layer with a layer resolution of 50-100 μm. An 86% dense ceramic results after sintering at 1500

oC.

As we can see, the manufacture of polymers on the Moon would be a boon in opening up 3D printing techniques. However, we cannot assume that these resources will be available so we must contend with a paucity of techniques for processing ceramics.

6. Lunar-Derived Clays

Here, we adopt clays as a ceramic material with plastic properties to avoid the use of polymers. Clays are hydrated aluminosilicates with ratios of SiO

2/Al

2O

3 of (2.0-5.0):1.0. Kaolinite clay (2SiO

2.Al

2O

3.2H

2O) with a water-to-clay ratio of ~0.60 may be 3D printed by DIW through 1.0-1.6 mm diameter nozzles, cured at room temperature for 24 h and sintered at 1100-1200

oC for several hours to yield porcelain with compressive strength of 20-50 MPa [

64]. The use of embedded temperature and relative humidity sensors for feedback yields strengths of 70 MPa for fired clay and 90 MPa for non-fired clay [

65]. Layerwise slurry deposition uses a slurry feedstock of regolith mixed with 40% hydrated montmorillonite clay deposited via a blade in 25-100 μm layers [

66]. During drying, water from the current layer is drawn into the substrate layer by capillary forces to create a dry high density powder bed. Either binder jetting of polymer fluid or laser sintering of powder layer may be adopted. The completed 3D part is then sintered at 1130

oC in a furnace. Martian salts MgSO

4 binding with SiO

2 to form forsterite Mg

2SiO

4 or enstatite Mg

2Si

2O

6 could strengthen the part if Martian resources were available. A lunar version could exploit Sorel cement as a binder at the cost of consuming Cl import from Earth reacting with lunar olivine:

3MgO + MgCl2 + 11H2O → 3Mg(OH)2.MgCl2.8H2O

Bamboo fibre reinforcement may be added [

67], a highly versatile material suited to a lunar agricultural facility [

68].

Geopolymer is an alkali-activated cement such as the clay-like aluminosilicate metakaolin activated by sodium silicate (waterglass). They form a 3D network of covalent Si-O-Al bonds M

n{-(SiO

2)

z-AlO

2}.wH

2O where M=metal cation such as K

+ and Na

+, n=polymerisation degree, z=1,2 or 3, w=bound water. Geopolymer may be constructed from metakaolinite (dehydroxylated kaolinite) comprising 90-95% Al

2O

3 and SiO

2 which dissolves in an activating alkali such as NaOH or KOH. Plasticising fillers can alter the viscoelasticity. These are commonly organics such as sodium carboxymethyl starch which increases viscosity but magnesium aluminium silicate is a smectite clay derived from feldspar that serves the same purpose. Geopolymer may be mixed with aggregates such as 20% silica sand which reduces shrinkage. 3D printing geopolymers may be via extrusion of geopolymer paste or geopolymer powders which are activated by NaOH solution which gives higher compression strength than KOH [

69]. Na

2CO

3 activation reaction proceeds more slowly which may be desirable but requires a carbon source. Curing at high temperature ~100

oC increases mechanical strength. A lunar regolith simulant-based geopolymer ink reinforced by carbon fibre/quartz in different patterns forms a 3D printed composite to reduce the brittleness of the geopolymer – rectangular sandwich patterns yielded the highest compressive strengths of 20 MPa and 34 MPa in y and x directions [

70]. Lunar-derived clays offer some the promise of ceramics but their true potential requires marriage with polymers.

7. Non-Clay Minerals and Their Uses

There are other uses for non-clay lunar minerals. On the Moon, olivine forsterite (Mg2SiO4) may be reacted with quartz (SiO2) to form the orthopyroxene enstatite (MgSiO3):

Mg2SiO4 + SiO2 → 2MgSiO3

The hydration of enstatite yields serpentinite (Mg3Si2O5(OH)4) and talc (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2):

6MgSiO3 + H2O → Mg3Si2O5(OH)4 + Mg3Si4O10(OH)2

Talc may be employed as a dry lubricant as an alternative to tungsten or molybdenum disulphide [

71]. Exploitation of such lunar minerals as ceramic resources has yet to be explored.

8. Conclusions

The complexity of the ink of DIW and its reliance on polymers renders DIW unsuitable for the Moon even in support of human habitats – organic matter consumed in inks or binders must be either recycled through a closed loop capability or supplied from Earth. Although recycling may be plausible for some simple polymers, DIW inks are too complex to re-synthesise. SLA-based methods similarly rely on photopolymers and photoinitiator polymers but these are more plausibly manufacturable than DIW inks though they still require a carbon source. More traditional ceramic processing methods appear more suitable for lunar application. Sintering ceramics directly using solar concentrators is not reliant on the manufacture of organic polymers or other complex materials though there remain issues regarding brittleness. However, to exploit the full range and versatility of ceramics derived from lunar resources, carbon sources on the Moon to permit the synthesis of polymers must be searched for at the highest priority. The potential for lunar-derived ceramics is under-explored in comparison with lunar-derived metals. Lunar industrialization will be critically dependent on deployment of lunar ceramics so this requires urgent address.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mueller, R.; et al. Automated additive construction (AAC) for Earth and space using in-situ resources. Proc Biennial ASCE Conf on Engineering, Science, Construction & Operations in Challenging Environments; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, M.; Ellery, A. On the development of an ISRU-based calcium sulphoaluminate concrete for 3D printed and cast lunar surface infrastructure applications. AIAA SciTech Forum, 2025; Orlando, FL, paper no 1863. [Google Scholar]

- Ellery, A. Leveraging in-situ resources for lunar base construction. Canadian J Civil Engineering 2021, 49, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, M.; Kazemi, Z.; Moazen, S.; Dube, M.; Potvin, M.-J.; Skonieczny, K. Comprehensive review of lunar-based manufacturing and construction. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 2024, 150, 101045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zocca, A.; Wilbig, J.; Gunster, J.; Widjaja, P.; Neumann, C.; Clozel, M.; Meyer, A.; Ding, J.; Zhou, Z.; Tian, X. Challenges in the technology development for additive manufacturing in space. Chinese J Mechanical Engineering: Additive Manufacturing Frontiers 2022, 1, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, A. Challenges of robotic milli-g operations for asteroid mining. In Proc Future Technologies Conference 4; Arai, K, Ed.; 2024; Volume 1157, pp. 45–64, Lecture Notes on Networks & Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Ellery, A. Sustainable in-situ resource utilisation on the Moon. Planetary & Space Science 2020, 184, 104870. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z.; Gong, Q.; Liu, N.; Jiang, B.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Gu, W. Elemental abundances of Moon samples based on statistical distributions of analytical data. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiken, G.; Vaniman, D.; French, B. Lunar Sourcebook: A Users Guide to the Moon. Cambridge University Press, 1991. Available online: https://www.lpi.usra.edu/publications/books/lunar_sourcebook/pdf/LunarSourceBook.pdf.

- Ellery, A. “Mining asteroid versus mining the Moon – can you have your cake and eat it?. extended abstract accepted by Space Resources Roundtable, Colorado School of Mines, CO. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Unterclass, M. Geomimetics and extreme biomimetics inspired by hydrothermal systems – what can we learn from nature for materials synthesis? Biomimetics 2017, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasaga, A.; Soler, J.; Ganor, J.; Burch, T.; Nagy, K. Chemical weathering rate laws and global geochemical cycles. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1994, 58, 2361–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, B.; Walls, X.; Ellery, A.; Cousens, B.; Marczenko, K. Extraction of silica and alumina from lunar highland simulant. Proc ASCE Earth & Space Conf 2024, 6962. [Google Scholar]

- Ellery, A.; Mellor, I.; Wanjara, P.; Conti, M. Metalysis FFC process as a strategic lunar in-situ resource utilisation technology. New Space J 2022, 10, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, X.; Ellery, A.; Marczenko, K.; Wanjara, P. Aluminium metal extraction from lunar highland simulant using electrochemistry. Proc ASCE Earth & Space Conf 2024, 7061. [Google Scholar]

- Hogue, M.; Mueller, R.; Sibille, L.; Hintze, P.; Rasky, D. Extraterrestrial regolith derived atmospheric entry heat shields. Proc 15th Biennial ASCE Conf Engineering, Science, Construction & Operations in Challenging Environments; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Ding, J.; Deng, C.; Zhu, H. Properties of inorganic high temperature adhesive for high temperature furnace connection. Ceramics International 2019, 45, 8684–8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, A.; Zolotiv, M.; Sharp, T.; Leshkin, L. Preferential low pH dissolution of pyroxene in plagioclase-pyroxene mixtures: implications for martian surface materials. Icarus 2008, 196, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankberg, E. Ceramic that bends instead of shattering. Science 2022, 378, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Carotenuto, G.; Nicolais, L. Review of ceramic sintering and suggestions on reducing sintering temperatures. Advanced Performance Materials 1997, 4, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, A. Generating and storing power on the Moon using in-situ resources. Proc IMechE J Aerospace Engineering 2021, 236, 1045–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakifahmetoglu, C.; Karacasulu, L. Cold sintering of ceramics and glasses: a review. Current Opinion in Solid State & Materials Science 2020, 24, 100807. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, N.; Yanagisawa, K.; Nishioka, M.; Kanahara, S. Hydrothermal hot-pressing method: apparatus and application. J Materials Science Letters 1986, 5, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, K.; Nishioka, M.; Ioku, K.; Yamasaki, N. Densification of silica gels by hydrothermal hot-pressing. J Materials Science Letters 1993, 12, 1073–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakifahmetoglu, C.; Karacasulu, L. Cold sintering of ceramics and glasses: a review. Current Opinion in Solid State & Materials Science 2020, 24, 100807. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Shui, A.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Tian, W.; Ota, T.; Xi, X. Preparation of aluminium titanate flexible ceramic by solid phase sintering and its mechanical behaviour. J Alloys & Compounds 2019, 777, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto, A.; Obata, M.; Asaoka, H.; Hayashi, H. Fabrication of alumina-based ceramic foams utilising superplasticity. J European Ceramic Society 2007, 27, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakai, F.; Kondo, N.; Shinoda, Y. Ceramics superplasticity. Current Opinion in Solid State & Materials Science 1999, 4, 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Pilling, J.; Payne, J. Superplasticity in Al2O3-ZrO2-Al2TiO5 ceramics. Scripta Metallurgica et Materiala 1995, 32, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Peng, H.; Nygren, M. Formidable increase in the superplasticity of ceramics in the presence of an electric field. Advances in Materials 2003, 15, 1006–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, M.; Huang, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, K. Borrowed dislocations for ductility in ceramics. Science 2024, 385, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Cao, J.; Noda, K.; Han, K. Mechanical properties of ceramic-metal composites by pressure infiltration of metal into porous ceramics. Materials Science & Engineering A 2004, 374, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, F.; Zuo, Y.; Pan, Y.; Yu, A.; Qi, J.; Lu, X. Iron-enhanced simulated lunar regolith sintered blocks: preparation, sintering and mechanical properties. Construction & Building Materials 2024, 439, 137395. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimian, M.; Ehsani, N.; Parvin, N.; Baharvandi, H. Effect of particle size, sintering temperature and sintering time on the properties of Al-Al2O3 composites made by powder metallurgy. J Materials Processing Technology 2009, 209, 5387–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, M.; Siahsarani, A.; Hadian, A.; Kazemi, Z.; Rahmatabadi, D.; Kashani-Bozorg, F.; Abrinia, K. Laser powder bed fusion of alumina/Fe-Ni ceramic matrix particulate composites impregnated with a polymeric resin. J Materials Research & Technology 2023, 24, 3133–3144. [Google Scholar]

- Laot, M.; Rich, B.; Cheibas, I.; Fu, J.; Zhu, J.-N.; Popovich, V. Additive manufacturing and spark plasma sintering of lunar regolith for functionally graded materials. Spool 2021, 8, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, T.; Kashani, A.; Imbalzano, G.; Nguyen, K.; Hui, D. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): a review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Composites B: Engineering 2018, 143, 172–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Mu, Z.; He, Y.; Kong, K.; Jiang, K.; Tang, R.; Liu, Z. Organic-inorganic covalent-ionic molecules for elastic ceramic plastic. Nature 2023, 619, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Mao, L.-B.; Lei, Z.; Yu, S.-H.; Colfen, H. Hydrogels from amorphous calcium carbonate and polyacrylic acid: bio-inspired materials for ‘mineral plastic’. Angewandte Chemie Int Edition 2016, 55, 11765–11769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, T.; Huang, G. State-of-the-art research progress and challenge of the printing techniques, potential applications for advanced ceramic materials 3D printing. Materials Today Communications 2024, 40, 110001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, F.; Sarraf, F.; Borzi, A.; Neels, A.; Hadian, A. Material extrusion additive manufacturing of advanced ceramics: towards the production of large components. J European Ceramic Society 2023, 43, 2752–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-S.; Sacks, M. Effect of particle size distribution on the sintering of alumina. Communications of American Ceramic Society 1988, 71, C484–C487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Dong, X.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Li, S.; Shen, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, G.; He, R. Additive manufacturing of fibre reinforced ceramic matrix composites: advances, challenges and prospects. Ceramics International 2021, 48, 19542–19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Fiore, B.; Erb, R. Designing bioinspired composite reinforcement architectures via 3D magnetic printing. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 8641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, L.; Tang, D.; Sun, T.; Xiong, W.; Feng, Z.; Evans, K.; Li, Y. Direct ink writing of mineral materials – a review. Int J Precision Engineering & Manufacturing – Green Technology 2021, 8, 665–685. [Google Scholar]

- Lamnini, S.; Elsaed, H.; Lakhdar, Y.; Baino, F.; Smeacetto, F.; Bernado, E. Robocasting of advanced ceramics: ink optimization and protocol to predict the printing parameters – a review. Helyon 2022, 8, e10651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Lao, C.; Fu, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; He, Y. 3D printing of ceramics: a review. J European Ceramic Society 2019, 39, 661–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Lazoglu, I. Direct ink writing of structural and functional ceramics: recent achievements and future challenges. Composites B 2021, 225, 109249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakus, A.; Koube, K.; Geisendorfer, N.; Shah, R. Robust and elastic lunar and martian structures from 3D printed regolith inks. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 44931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, V.; Saiz, E.; Tirichenko, I.; Garcia-Tunon, E. Direct ink writing advances in multi-material structures for a sustainable future. J Materials Chemistry A 2020, 8, 15646–15657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, P.; Cintala, M.; Horz, F.; Cressey, G. Survivability of meteorite projectiles – results from impact experiments. 32nd Lunar & Planetary Science Conf; 2001. abstract no 1764. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, P.; Artemieva, N.; Collins, G.; Bottke, W.; Bussey, D.; Joy, K. (2008) “Asteroids on the Moon: projectile survival during low velocity impacts. 39th Lunar & Planetary Science Conf; 2008. abstract no 2045. [Google Scholar]

- Halim, S.; Crawford, I.; Collins, G.; Joy, K.; Davison, T. Assessing the survival of carbonaceous chondrites impacting the lunar surface as a potential resource. Planetary & Space Sciences 2024, 246, 105905. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, K.; Crawford, I.; Curran, N.; Zolensky, M.; Fagan, A.; King, D. Moon: an archive of small body migration in the solar system. Earth Moon & Planets 2016, 118, 133–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, M.-H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, B.; Du, J.; Fa, W.; Xu, R.; He, Z.; Wang, C.; Xue, B.; Yang, J.; Zou, Y. Impact remnants rich in carbonaceous chondrites detected on the Moon by the Chang’e 4 rover. Nature Astronomy 2022, 6, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, A. Trials and tribulations of asteroid mining. Proc ASCE Earth & Space Conf 2024, 8087. [Google Scholar]

- O’Lenick, A. Basic silicone chemistry – a review. Silicone Spectator 2009, 8087. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, R.; Parameswaran, C.; Idrees, M.; Rasaki, A.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Colombo, P. Additive manufacturing of polymer-derived ceramics: materials, technologies, properties and potential applications. Progress in Materials Science 2022, 128, 100969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.; Murugavel, R. Recent developments in the chemistry of molecular titanosiloxanes and titanophosphonates. Synthesis & Reactivity in Inorganic, Metal-Organic & Nano-Metal Chemistry 2005, 35, 591–622. [Google Scholar]

- Unny, R.; Gopinathan, S.; Gopinathan, C. Chelated aluminosiloxanes. Indian J Chemistry 1980, 19A, 484–486. [Google Scholar]

- Puxviel, J.; Boilot, J.; Poncelet, O.; Hubert-Pfalzgraf, L.; Lecomte, A.; Dauger, A.; Beloeil, J. Aluminosiloxane as a ceramic precursor. J Non-Crystalline Solids 1987, 93, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, M.; Halloran, J. Freeform fabrication of ceramics vis stereolithography. J American Ceramics Society 1996, 79, 2601–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, R.; Tang, W.; Hu, K.; Wang, L. Ceramic paste for space stereolithography 3D printing technology in microgravity environments. J European Ceramic Society 2022, 42, 3968–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelo, C.; Colorado, H. 3D printing of kaolinite clay ceramics using direct ink writing (DIW) technique. Ceramics International 2018, 44, 5673–5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, C.; Mata, J.; Renteria, A.; Gonzalez, D.; Gomez, G.; Lopez, A.; Baca, A.; Nunez, A.; Hassan, S.; Burke, V.; Perlasca, D.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Kruichak, J.; Espalin, D.; Lin, Y. Direct ink-write printing of ceramic clay with an embedded wireless temperature and relative humidity sensor. Sensors 2023, 23, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, D.; Kamutzki, F.; Lima, P.; Gili, A.; Duminy, T.; Zocca, A.; Gunster, J.; Gurlo, A. Sintering of ceramics for clay in situ resource utilisation of Mars. Open Ceramics 2020, 3, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Jaw, W.; Pothunuri, L.; Soh, E.; Le Ferrand, H. Easily applicable protocol to formulate inks for extrusion-based 3D printing. Ceramica 2022, 68, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, A. Supplementing closed ecological life support systems with in-situ resources on the Moon. Life 2021, 11, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazorenko, G.; Kasprzhitskii, A. Geopolymer additive manufacturing: a review. Additive Manufacturing 2022, 55, 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, S.; He, P.; Sun, C.; Duan, X.; Jia, D.; Colombo, P.; Zhou, Y. 3D printed lunar regolith simulant-based geopolymer composites with bio-inspired sandwich architectures. J Advanced Ceramics 2023, 12, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, S.; Orkuma, G.; Apasi, A. Talc as a substitute for dry lubricant (an overview). AIP Proc 2011, 1315, 1400. [Google Scholar]

Table 1.

Lunar industrial ecology that converts raw lunar and asteroidal resources into final functional materials – inputs are on the left and applications are on the right (only a few feedback loops are shown).

Table 1.

Lunar industrial ecology that converts raw lunar and asteroidal resources into final functional materials – inputs are on the left and applications are on the right (only a few feedback loops are shown).

| Lunar Ilmenite |

|

|

|

|

| Fe0 + H2O → ferrofluidic sealing |

|

|

|

|

| FeTiO3 + H2 → TiO2 + H2O + Fe |

|

|

|

|

| |

2H2O→2H2+O2

|

|

|

|

| |

|

2Fe + 1.5O2 → Fe2O3/Fe2O3.CoO - ferrite magnets |

|

|

| |

|

|

3Fe2O3 + H2 ↔ Fe3O4 + H2O) – formation of magnetite at 350-750oC/1-2 kbar |

|

| |

|

|

4Fe2O3 + Fe ↔ 3Fe3O4 ) |

|

| Nickel-Iron Meteorites |

|

|

|

|

| W inclusions→ |

Thermionic cathodic material |

|

|

|

| Mond process: |

Alloy Ni Co Si C W |

| W(CO)6 ↔ 6CO + W |

|

|

|

|

| Fe(CO)5 ↔ 5CO + Fe (175oC/100 bar) → |

Tool steel |

2% |

9-18% |

|

| Ni(CO)4 ↔ 4CO + Ni (55oC/1 bar) → |

Electrical steel |

3% |

|

|

| Co2(CO)8 ↔ 8CO + 2Co (150oC/35 bar) → |

Permalloy |

80% |

|

|

| S catalyst |

Kovar 29% 17% 0.2% 0.01% ____ . |

| 4FeS + 7O2 → 2Fe2O3 + 4SO2

|

|

|

|

|

| (Troilite) |

SO2 + H2S → 3S + H2O |

|

|

|

| FeSe + Na2CO3 + 1.5O2 → FeO + Na2SeO3 + CO2 at 650oC |

| KNO3 catalyst |

Na2SeO3 + H2SO4 → Na2O + H2SO4 + Se → photosensitive Se |

| |

↑____________| |

| |

Na2O + H2O → 2NaOH |

|

|

|

| |

|

NaOH + HCl → NaCl + H2O |

|

|

| Lunar Orthoclase |

|

|

|

|

| 3KAlSi3O8 + 2HCl + 12H2O → KAl3Si3O10(OH)2 + 6H4SiO4 + 2KCl |

| orthoclase |

illite |

silicic acid (soluble silica) |

|

|

| 2KAl3Si3O10(OH)2 + 2HCl + 3H2O → 3Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + 2KCl |

| |

kaolinite |

|

|

|

| [2KAlSi3O8 + 2HCl + 2H2O → Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + 2KCl + SiO2 + H2O] |

| |

KCl + NaNO3 → NaCl + KNO3

|

|

|

|

| |

2KCl + Na2SO4 → 2NaCl + K2SO4

|

|

|

|

| Lunar Olivine |

|

|

|

|

| Fe2SiO4 + 4 HCl + 4H2O → 2FeCl2+ SiO2 + 2H2O |

|

|

|

|

| fayalite |

|

|

|

|

| Mg2SiO4 + 4HCl + 4H2O→ 2MgCl2 + 2H4SiO4

|

|

→ Sorel cement |

|

|

| forsterite |

MgCl2 +2NaOH → Mg(OH)2 + 2NaCl |

|

|

|

| |

Mg(OH)2 → MgO + H2O |

→ Sorel cement |

|

|

| |

600-800oC |

|

|

|

| Lunar Anorthite |

|

|

|

|

| CaAl2Si2O8 + 4C → CO + CaO + Al2O3 + 2Si at 1650oC |

→ CaO cathode coatings |

|

|

|

| |

CaO + H2O → Ca(OH)2

|

|

|

|

| |

Ca(OH)2 + CO2 → CaCO3 + H2O |

|

|

|

| CaAl2SiO8 + 8HCl + 2H2O → CaCl2 + 2AlCl3.6H2O + SiO2

|

|

→ fused silica glass + FFC electrolyte |

|

|

| |

AlCl3.6H2O → Al(OH)3 + 3HCl + H2O at 100oC |

|

|

|

| |

↑________________________________________| |

|

|

|

| |

2Al(OH)3 → Al2O3 + 3H2O at 400oC → 2Al + Fe2O3 → 2Fe + Al2O3 (thermite) |

|

|

|

| |

AlNiCo hard magnets |

|

|

|

| Lunar Pyroxene |

Al solar sail |

|

|

|

| Ca(Fe,Al)Si2O6 + HCl + H2O → Ca0.33(Al)2(Si4O10)(OH)2.nH2O + H4SiO4 + CaCl2 + Fe(OH)3 |

| Augite |

montmorillonite |

silicic acid |

iron hydroxide |

|

| Lunar Volatiles |

|

|

|

|

| CO + 0.5 O2 → CO2 |

|

|

|

|

| |

CO2 + 4H2 → CH4 + 2H2O at 300oC (Sabatier reaction) |

|

|

|

| |

Ni catalyst |

|

|

|

| 850oC |

250oC |

|

|

|

| CH4 + H2O → CO + 3H2 → CH3OH 350oC |

|

|

|

|

| Ni catalyst |

Al2O3

|

CH3OH + HCl → CH3Cl + H2O |

370oC |

+nH2O |

| |

Al2O3 CH3Cl + Si → (CH3)2SiCl2 → ((CH3)2SiO)n + 2nHCl → silicone plastics/oils |

| |

↑_________________________________________| |

| N2 + 3H2 → 2NH3 (Haber-Bosch process) |

|

|

|

|

| Fe on CaO+SiO2+Al2O3 |

|

|

|

|

| 4NH3 + 5O2 → 4NO + 6H2O |

|

|

|

|

| |

WC on Ni |

|

|

|

| |

|

3NO + H2O → 2HNO3 + NO (Ostwald process) |

|

|

| |

|

↑__________________| |

|

|

| 2SO2 + O2 ↔ 2SO3 (low temp) |

|

|

|

|

| |

SO3 + H2O → H2SO4

|

|

|

|

| Salt Reagent |

|

|

|

|

| 2NaCl + CaCO3 ↔ Na2CO3 + CaCl2 (Solvay process) → FFC electrolyte |

| |

350oC/150 MPa |

|

|

|

| |

Na2CO3 + SiO2(i) ↔ Na2SiO3 + CO2 → piezoelectric quartz crystal growth (40-80 days) |

| |

1000-1100oC |

|

|

|

| |

CaCO3 → CaO + CO2 (calcination) |

|

|

|

NaCl(s) + HNO3(g) → HCl(g) + NaNO3(s)

2NaCl(s) + H2SO4(g) → 2HCl(g) + Na2SO4(s) |

|

|

|

|

| Molten Salt (FFC) Process (CaCl2 electrolyte) |

|

|

|

|

| MOx + xCa → M + xCaO → M + xCa + ½xO2 where M=Fe, Ti, Al, Mg, Si, etc |

|

|

|

|

| CO + 0.5 O2 → CO2 |

|

|

|

|

| |

CO2 + 4H2 → CH4 + 2H2O at 300oC (Sabatier reaction) → CH4 → C + 2H2 at 1400oC → FFC anode regeneration |

| |

Ni catalyst |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Lunar resources mapped to spacecraft functions – percentages refer to the proportion of a generic dry spacecraft with excesses indicated for launch propellant to the Gateway and lunar habitat compressive structure.

Table 2.

Lunar resources mapped to spacecraft functions – percentages refer to the proportion of a generic dry spacecraft with excesses indicated for launch propellant to the Gateway and lunar habitat compressive structure.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).