Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

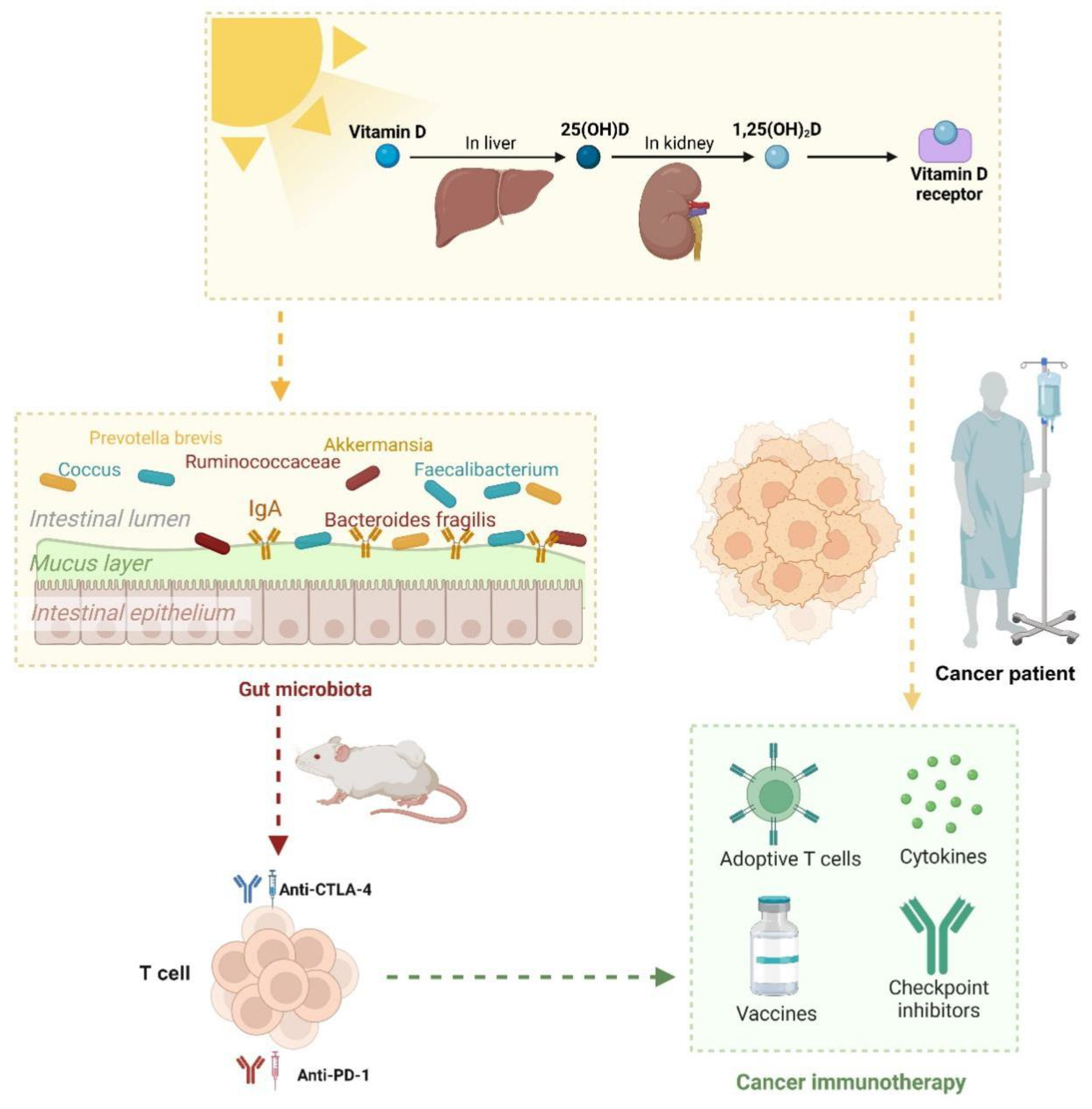

VD Metabolism and Function

Effects of VD-Cancer Immunotherapy

VD Interacts with Gut Microbiota

Gut Microbiota as a Determinant of Immunotherapy Efficacy

Gut Microbiota and VD Synergy in Modulating Cancer Immunotherapy

Conclusions

Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kennedy LB; Salama AKS. A review of cancer immunotherapy toxicity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020, 70(2), 86-104. [CrossRef]

- Szeto GL; Finley SD. Integrative Approaches to Cancer Immunotherapy. Trends Cancer. 2019, 5(7), 400-410. [CrossRef]

- Bouillon R; Marcocci C; Carmeliet G; Bikle D; White JH; Dawson-Hughes B; Lips P; Munns CF; Lazaretti-Castro M; Giustina A; Bilezikian J. Skeletal and Extraskeletal Actions of Vitamin D: Current Evidence and Outstanding Questions. Endocr Rev. 2019, 40(4), 1109-1151. [CrossRef]

- Grover S; Dougan M; Tyan K; Giobbie-Hurder A; Blum SM; Ishizuka J; Qazi T; Elias R; Vora KB; Ruan AB; Martin-Doyle W; Manos M; Eastman L; Davis M; Gargano M; Haq R; Buchbinder EI; Sullivan RJ; Ott PA; Hodi FS; Rahma OE. Vitamin D intake is associated with decreased risk of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. Cancer. 2020, 126(16), 3758-3767. [CrossRef]

- Ghaseminejad-Raeini A; Ghaderi A; Sharafi A; Nematollahi-Sani B; Moossavi M; Derakhshani A; Sarab GA. Immunomodulatory actions of vitamin D in various immune-related disorders: a comprehensive review. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 950465. [CrossRef]

- Tsuji A; Yoshikawa S; Morikawa S; Ikeda Y; Taniguchi K; Sawamura H; Asai T; Matsuda S. Potential tactics with vitamin D and certain phytochemicals for enhancing the effectiveness of immune-checkpoint blockade therapies. Explor Target Antitumor Ther. 2023, 4(3), 460-473. [CrossRef]

- Giampazolias E; Pereira da Costa M; Lam KC; Lim KHJ; Cardoso A; Piot C; Chakravarty P; Blasche S; Patel S; Biram A; Castro-Dopico T; Buck MD; Rodrigues RR; Poulsen GJ; Palma-Duran SA; Rogers NC; Koufaki MA; Minutti CM; Wang P; Vdovin A; Frederico B; Childs E; Lee S; Simpson B; Iseppon A; Omenetti S; Kelly G; Goldstone R; Nye E; Suárez-Bonnet A; Priestnall SL; MacRae JI; Zelenay S; Patil KR; Litchfield K; Lee JC; Jess T; Goldszmid RS; Reis e Sousa C. Vitamin D regulates microbiome-dependent cancer immunity. Science. 2024, 384(6694), 428-437. [CrossRef]

- Fessler J; Matson V; Gajewski TF. Exploring the emerging role of the microbiome in cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7(1), 108. [CrossRef]

- Vétizou M; Pitt JM; Daillère R; Lepage P; Waldschmitt N; Flament C; Rusakiewicz S; Routy B; Roberti MP; Duong CP; Poirier-Colame V; Roux A; Becharef S; Formenti S; Golden E; Cording S; Eberl G; Schlitzer A; Ginhoux F; Mani S; Yamazaki T; Jacquelot N; Enot DP; Bérard M; Nigou J; Opolon P; Eggermont A; Woerther PL; Chachaty E; Chaput N; Robert C; Mateus C; Kroemer G; Raoult D; Boneca IG; Carbonnel F; Chamaillard M; Zitvogel L. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science. 2015, 350(6264), 1079-84. [CrossRef]

- Chaput N; Lepage P; Coutzac C; Soularue E; Le Roux K; Monot C; Boselli L; Routier E; Cassard L; Collins M; Vaysse T; Marthey L; Eggermont A; Asvatourian V; Lanoy E; Mateus C; Robert C; Carbonnel F. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Ann Oncol. 2017, 28(6), 1368-1379. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X; Huang X; Hu M; Sun R; Li J; Wang H; Pan X; Ma Y; Ning L; Tong T; Zhou Y; Ding J; Zhao Y; Xuan B; Fang JY; Hong J; Hon Wong JW; Zhang Y; Chen H. A specific enterotype derived from gut microbiome of older individuals enables favorable responses to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cell Host Microbe. 2024, 32(4), 489-505.e5. [CrossRef]

- Park EM; Chelvanambi M; Bhutiani N; Kroemer G; Zitvogel L; Wargo JA. Targeting the gut and tumor microbiota in cancer. Nat Med. 2022, 28(4), 690-703. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan V; Spencer CN; Nezi L; Reuben A; Andrews MC; Karpinets TV; Prieto PA; Vicente D; Hoffman K; Wei SC; Cogdill AP; Zhao L; Hudgens CW; Hutchinson DS; Manzo T; Petaccia de Macedo M; Cotechini T; Kumar T; Chen WS; Reddy SM; Szczepaniak Sloane R; Galloway-Pena J; Jiang H; Chen PL; Shpall EJ; Rezvani K; Alousi AM; Chemaly RF; Shelburne S; Vence LM; Okhuysen PC; Jensen VB; Swennes AG; McAllister F; Marcelo Riquelme Sanchez E; Zhang Y; Le Chatelier E; Zitvogel L; Pons N; Austin-Breneman JL; Haydu LE; Burton EM; Gardner JM; Sirmans E; Hu J; Lazar AJ; Tsujikawa T; Diab A; Tawbi H; Glitza IC; Hwu WJ; Patel SP; Woodman SE; Amaria RN; Davies MA; Gershenwald JE; Hwu P; Lee JE; Zhang J; Coussens LM; Cooper ZA; Futreal PA; Daniel CR; Ajami NJ; Petrosino JF; Tetzlaff MT; Sharma P; Allison JP; Jenq RR; Wargo JA. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti–PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018, 359(6371), 97-103. [CrossRef]

- Matson V; Fessler J; Bao R; Chongsuwat T; Zha Y; Alegre ML; Luke JJ; Gajewski TF. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti–PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science. 2018, 359(6371), 104-108. [CrossRef]

- Kanstrup C; Teilum D; Rejnmark L; Bigaard JV; Eiken P; Kroman N; Tjønneland A; Mejdahl MK. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D at time of breast cancer diagnosis and breast cancer survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020, 179(3), 699-708. [CrossRef]

- Filip-Psurska B; Zachary H; Strzykalska A; Wietrzyk J. Vitamin D, Th17 Lymphocytes, and Breast Cancer. Cancers. 2022, 14(15), 3649. [CrossRef]

- Holick MF; Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008, 87(4), 1080S-6S. [CrossRef]

- Palacios C; Gonzalez L. Is vitamin D deficiency a major global public health problem? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014, 144 Pt A, 138-45. [CrossRef]

- Roth DE; Abrams SA; Aloia J; Bergeron G; Bourassa MW; Brown KH; Calvo MS; Cashman KD; Combs G; De-Regil LM; Jefferds ME; Jones KS; Kapner H; Martineau AR; Neufeld LM; Schleicher RL; Thacher TD; Whiting SJ. Global prevalence and disease burden of vitamin D deficiency: a roadmap for action in low- and middle-income countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018,1430(1),44-79. [CrossRef]

- Giustina A; Bilezikian JP; Adler RA; Banfi G; Bikle DD; Binkley NC; Bollerslev J; Bouillon R; Brandi ML; Casanueva FF; di Filippo L; Donini LM; Ebeling PR; Fuleihan GE; Fassio A; Frara S; Jones G; Marcocci C; Martineau AR; Minisola S; Napoli N; Procopio M; Rizzoli R; Schafer AL; Sempos CT; Ulivieri FM; Virtanen JK. Consensus Statement on Vitamin D Status Assessment and Supplementation: Whys, Whens, and Hows. Endocr Rev. 2024,45(5),625-654. [CrossRef]

- Saccone D; Asani F; Bornman L. Regulation of the vitamin D receptor gene by environment, genetics and epigenetics. Gene.2015,561(2),171-80. [CrossRef]

- Carlberg C; Raczyk M; Zawrotna N. Vitamin D: A master example of nutrigenomics. Redox Biol. 2023, 62,102695. [CrossRef]

- Delrue C; Speeckaert MM. Vitamin D and Vitamin D-Binding Protein in Health and Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023, 24(5),4642. [CrossRef]

- Thouvenot E; Laplaud D; Lebrun-Frenay C; Derache N; Le Page E; Maillart E; Froment-Tilikete C; Castelnovo G; Casez O; Coustans M; Guennoc AM; Heinzlef O; Magy L; Nifle C; Ayrignac X; Fromont A; Gaillard N; Caucheteux N; Patry I; De Sèze J; Deschamps R; Clavelou P; Biotti D; Edan G; Camu W; Agherbi H; Renard D; Demattei C; Fabbro-Peray P; Mura T; Rival M; D-Lay MS Investigators. High-Dose Vitamin D in Clinically Isolated Syndrome Typical of Multiple Sclerosis: The D-Lay MS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2025,333(16),1413-1422. [CrossRef]

- Xiang H; Zhou C; Gan X; Huang Y; He P; Ye Z; Liu M; Yang S; Zhang Y; Zhang Y; Qin X. Relationship of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations, Diabetes, Vitamin D Receptor Gene Polymorphisms and Incident Venous Thromboembolism. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2025, 41(1),e70014. [CrossRef]

- Charoenngam N; Shirvani A; Holick MF. Vitamin D for skeletal and non-skeletal health: What we should know. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019, 10(6), 1082-1093. [CrossRef]

- Demay MB; Pittas AG; Bikle DD; Diab DL; Kiely ME; Lazaretti-Castro M; Lips P; Mitchell DM; Murad MH; Powers S; Rao SD; Scragg R; Tayek JA; Valent AM; Walsh JME; McCartney CR. Vitamin D for the Prevention of Disease: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024,109(8):1907-1947. [CrossRef]

- Fekete M; Lehoczki A; Szappanos Á; Zábó V; Kaposvári C; Horváth A; Farkas Á; Fazekas-Pongor V; Major D; Lipécz Á; Csípő T; Varga JT. Vitamin D and Colorectal Cancer Prevention: Immunological Mechanisms, Inflammatory Pathways, and Nutritional Implications. Nutrients. 2025,17(8):1351. [CrossRef]

- Thouvenot E; Laplaud D; Lebrun-Frenay C; Derache N; Le Page E; Maillart E; Froment-Tilikete C; Castelnovo G; Casez O; Coustans M; Guennoc AM; Heinzlef O; Magy L; Nifle C; Ayrignac X; Fromont A; Gaillard N; Caucheteux N; Patry I; De Sèze J; Deschamps R; Clavelou P; Biotti D; Edan G; Camu W; Agherbi H; Renard D; Demattei C; Fabbro-Peray P; Mura T; Rival M; D-Lay MS Investigators. High-Dose Vitamin D in Clinically Isolated Syndrome Typical of Multiple Sclerosis. Jama 2025,333(16):1413-1422. [CrossRef]

- Lin K; Miao Y; Gan L; Zhao B; Fang F; Wang R; Chen X; Huang J. Associations of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations with Risks of Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease among Individuals with Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025, S0190-9622(25)02118-8. [CrossRef]

- Sha S; Xie R; Gwenzi T; Wang Y; Brenner H; Schöttker B. Real-world evidence for an association of vitamin D supplementation with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the UK Biobank. Clin Nutr. 2025,49,118-127. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-García A; Pallarés-Carratalá V; Turégano-Yedro M; Torres F; Sapena V; Martin-Gorgojo A; Martin-Moreno JM. Vitamin D Supplementation and Its Impact on Mortality and Cardiovascular Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 80 Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2023,15(8),1810. [CrossRef]

- Wang X; Li Q; Lyu Z; Wu Y. Supplementing with Vitamin D during Pregnancy Reduces Inflammation and Prevents Autism-Related Behaviors in Offspring Caused by Maternal Immune Activation. Biol Pharm Bull. 2025,48(5),632-640. [CrossRef]

- Mullard A. Addressing cancer's grand challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020, 19(12), 825-826. [CrossRef]

- Elkin EB; Bach PB. Cancer's next frontier: addressing high and increasing costs. JAMA. 2010,303(11),1086-7. [CrossRef]

- Riley RS; June CH; Langer R; Mitchell MJ. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2019,18(3),175-196. [CrossRef]

- Vanhooren J; Derpoorter C; Depreter B; Deneweth L; Philippé J; De Moerloose B; Lammens T. TARP as antigen in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021,70(11),3061-3068. [CrossRef]

- Paleari, L. Personalized Assessment for Cancer Prevention, Detection, and Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2024.25(15),8140. [CrossRef]

- Yu Q; Ding J; Li S; Li Y. Autophagy in cancer immunotherapy: Perspective on immune evasion and cell death interactions. Cancer Lett. 2024,590,216856. [CrossRef]

- Song S; Woo HD; Lyu J; Song BM; Lim JY; Park HY. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of overall and site-specific cancers in Korean adults: results from two prospective cohort studies. Nutr J. 2025, 24(1), 84. [CrossRef]

- Lim ST; Jeon YW; Suh YJ. Association Between Alterations in the Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Status During Follow-Up and Breast Cancer Patient Prognosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015, 16(6),2507-13. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi L; Almquist M; Borgquist S; Malm J; Manjer J. Serum vitamin D (25OHD3) levels and the risk of different subtypes of breast cancer: A nested case–control study. Breast. 2016,28,184-90. [CrossRef]

- Li H; Liu H; Wang B; Jia X; Yu J; Zhang Y; Sang D; Zhang Y. Exercise Interventions for the Prevention and Treatment of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Women with Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2024, 7 (1), 14-27. [CrossRef]

- Estébanez N; Gómez-Acebo I; Palazuelos C; Llorca J; Dierssen-Sotos T. Vitamin D exposure and Risk of Breast Cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018,8(1),9039. [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez-Mena JM; Schöttker B; Fedirko V; Jenab M; Olsen A; Halkjær J; Kampman E; de Groot L; Jansen E; Bueno-de-Mesquita HB; Peeters PH; Siganos G; Wilsgaard T; Perna L; Holleczek B; Pettersson-Kymmer U; Orfanos P; Trichopoulou A; Boffetta P; Brenner H. Pre-diagnostic vitamin D concentrations and cancer risks in older individuals: an analysis of cohorts participating in the CHANCES consortium. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016, 31(3),311-23. [CrossRef]

- Pouliliou S; Nikolaidis C; Drosatos G. Current trends in cancer immunotherapy: a literature-mining analysis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020,69(12),2425-2439. [CrossRef]

- Yu WD; Sun G; Li J; Xu J; Wang X. Mechanisms and therapeutic potentials of cancer immunotherapy in combination with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2019,452,66-70. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser M; Semeraro MD; Herrmann M; Absenger G; Gerger A; Renner W. Immune Aging and Immunotherapy in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021,22(13),7016. [CrossRef]

- Topalian SL; Weiner GJ; Pardoll DM. Cancer Immunotherapy Comes of Age. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29(36),4828-36. [CrossRef]

- Rui R; Zhou L; He S. Cancer immunotherapies: advances and bottlenecks. Front Immunol. 2023,14,1212476. [CrossRef]

- Chun RF; Liu PT; Modlin RL; Adams JS; Hewison M. Impact of vitamin D on immune function: lessons learned from genome-wide analysis. Front Physiol. 2014, 5, 151. [CrossRef]

- Charoenngam N; Holick MF. Immunologic Effects of Vitamin D on Human Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2020, 12(7), 2097. [CrossRef]

- Feldman D; Krishnan AV; Swami S; Giovannucci E; Feldman BJ. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014, 14(5), 342-57. [CrossRef]

- Martens PJ; Gysemans C; Verstuyf A; Mathieu AC. Vitamin D's Effect on Immune Function. Nutrients. 2020, 2(5), 1248. [CrossRef]

- Artusa P; White JH. Vitamin D and its analogs in immune system regulation. Pharmacol Rev. 2025, 77(2), 100032. [CrossRef]

- Sîrbe C; Rednic S; Grama A; Pop TL. An Update on the Effects of Vitamin D on the Immune System and Autoimmune Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(17), 9784. [CrossRef]

- Das D; Karthik N; Taneja R. Crosstalk Between Inflammatory Signaling and Methylation in Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 756458. [CrossRef]

- Kim DH; Meza CA; Clarke H; Kim JS; Hickner RC. Vitamin D and Endothelial Function. Nutrients. 2020, 12(2), 575. [CrossRef]

- Holick MF. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017, 18(2), 153-165. [CrossRef]

- Giulietti A; van Etten E; Overbergh L; Stoffels K; Bouillon R; Mathieu C. Monocytes from type 2 diabetic patients have a pro-inflammatory profile. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) works as anti-inflammatory. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007, 77(1). 47-57. [CrossRef]

- Galus Ł; Michalak M; Lorenz M; Stoińska-Swiniarek R; Tusień Małecka D; Galus A; Kolenda T; Leporowska E; Mackiewicz J. Vitamin D supplementation increases objective response rate and prolongs progression-free time in patients with advanced melanoma undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer. 2023, 129(13), 2047-2055. [CrossRef]

- Stucci LS; D'Oronzo S; Tucci M; Macerollo A; Ribero S; Spagnolo F; Marra E; Picasso V; Orgiano L; Marconcini R; De Rosa F; Di Guardo L; Galli G; Gandini S; Palmirotta R; Palmieri G; Queirolo P; Silvestris F. Italian Melanoma Intergroup (IMI). Vitamin D in melanoma: Controversies and potential role in combination with immune check-point inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018, 69, 21-28. [CrossRef]

- Bersanelli M; Cortellini A; Leonetti A; Parisi A; Tiseo M; Bordi P; Michiara M; Bui S; Cosenza A; Ferri L; Giudice GC; Testi I; Rapacchi E; Camisa R; Vincenzi B; Caruso G; Rauti AN; Arturi F; Tucci M; Santo V; Ricozzi V; Burtet V; Sgargi P; Todeschini R; Zustovich F; Stucci LS; Santini D; Buti S. Systematic vitamin D supplementation is associated with improved outcomes and reduced thyroid adverse events in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: results from the prospective PROVIDENCE study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023, 72(11), 3707-3716. [CrossRef]

- Mondul AM; Weinstein SJ; Layne TM; Albanes D. Vitamin D and Cancer Risk and Mortality: State of the Science, Gaps, and Challenges. Epidemiol Rev. 2017, 39(1), 28-48. [CrossRef]

- Jeffery LE; Burke F; Mura M; Zheng Y; Qureshi OS; Hewison M; Walker LS, Lammas DA; Raza K; Sansom DM. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and IL-2 combine to inhibit T cell production of inflammatory cytokines and promote development of regulatory T cells expressing CTLA-4 and FoxP3. J Immunol. 2009, 183(9), 5458-67. [CrossRef]

- Adorini L; Daniel KC; Penna G. Vitamin D receptor agonists, cancer and the immune system: an intricate relationship. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006, 6(12), 1297-301. [CrossRef]

- Wang J; Zhu N; Su X; Gao Y; Yang R. Gut-Microbiota-Derived Metabolites Maintain Gut and Systemic Immune Homeostasis. Cells. 2023, 12(5), 793. [CrossRef]

- Fan Y; Pedersen O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021, 19(1), 55-71. [CrossRef]

- Adak A; Khan MR. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019, 76(3), 473-493. [CrossRef]

- Zmora N; Suez J; Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019, 16(1), 35-56. [CrossRef]

- Liao X; Lan Y; Wang W; Zhang J; Shao R; Yin Z; Gudmundsson GH; Bergman P; Mai K; Ai Q; Wan M. Vitamin D influences gut microbiota and acetate production in zebrafish (Danio rerio) to promote intestinal immunity against invading pathogens. Gut Microbes. 2023, 15(1), 2187575. [CrossRef]

- Fan L; Xia Y; Wang Y; Han D; Liu Y; Li J; Fu J; Wang L; Gan Z; Liu B; Fu J; Zhu C; Wu Z; Zhao J; Han H; Wu H; He Y; Tang Y; Zhang Q; Wang Y; Zhang F; Zong X; Yin J; Zhou X; Yang X; Wang J; Yin Y; Ren W. Gut microbiota bridges dietary nutrients and host immunity. Sci China Life Sci. 2023, 66(11), 2466-2514. [CrossRef]

- Góralczyk-Bińkowska A; Szmajda-Krygier D; Kozłowska E. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Psychiatric Disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(19), 11245. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z; Wang Z; Lu T; Chen W; Yan W; Yuan K; Shi L; Liu X; Zhou X; Shi J; Vitiello MV; Han Y; Lu L. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2022, 65, 101691. [CrossRef]

- Zuo WF; Pang Q; Yao LP; Zhang Y; Peng C; Huang W; Han B. Gut microbiota: A magical multifunctional target regulated by medicine food homology species. J Adv Res. 2023 ,52, 151-170. [CrossRef]

- Huang L; Lum D; Haiyum M; Fairbairn KA. Vitamin D Status of Elite Athletes in Singapore and Its Associations With Muscle Function and Bone Health. SSEJ. 2021, 3 (4), 385-393. [CrossRef]

- Ullah H. Gut-vitamin D interplay: key to mitigating immunosenescence and promoting healthy ageing. Immun Ageing. 2025, 22(1), 20. [CrossRef]

- Aggeletopoulou I; Tsounis EP; Mouzaki A; Triantos C. Exploring the Role of Vitamin D and the Vitamin D Receptor in the Composition of the Gut Microbiota. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2023, 28(6), 116. [CrossRef]

- Sun J; Zhang YG. Vitamin D Receptor Influences Intestinal Barriers in Health and Disease. Cells. 2022, 11(7), 1129. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse M; Hope B; Krause L; Morrison M; Protani MM; Zakrzewski M; Neale RE. Vitamin D and the gut microbiome: a systematic review of in vivo studies. Eur J Nutr. 2019, 58(7), 2895-2910. [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi S; Masoumi SJ; Abiri B; Vafa M. The effects of synbiotic and/or vitamin D supplementation on gut-muscle axis in overweight and obese women: a study protocol for a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Trials. 2022, 23(1), 631. [CrossRef]

- Boughanem H; Ruiz-Limón P; Pilo J; Lisbona-Montañez JM; Tinahones FJ; Moreno Indias I; Macías-González M. Linking serum vitamin D levels with gut microbiota after 1-year lifestyle intervention with Mediterranean diet in patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome: a nested cross-sectional and prospective study. Gut Microbes. 2023 ,15(2), 2249150. [CrossRef]

- Thomas RL; Jiang L; Adams JS; Xu ZZ; Shen J; Janssen S; Ackermann G; Vanderschueren D; Pauwels S; Knight R; Orwoll ES; Kado DM. Vitamin D metabolites and the gut microbiome in older men. Nat Commun. 2020 ,11(1), 5997. [CrossRef]

- Clark A; Mach N. Role of Vitamin D in the Hygiene Hypothesis: The Interplay between Vitamin D, Vitamin D Receptors, Gut Microbiota, and Immune Response. Front Immunol. 2016, 7, 627. [CrossRef]

- Assa A; Vong L; Pinnell LJ; Avitzur N; Johnson-Henry KC; Sherman PM. Vitamin D deficiency promotes epithelial barrier dysfunction and intestinal inflammation. J Infect Dis. 2014, 210(8), 1296-305. [CrossRef]

- Battistini C; Ballan R; Herkenhoff ME; Saad SMI; Sun J. Vitamin D Modulates Intestinal Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 22(1), 362. [CrossRef]

- Du J; Wei X; Ge X; Chen; Li YC. Microbiota-Dependent Induction of Colonic Cyp27b1 Is Associated With Colonic Inflammation: Implications of Locally Produced 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 in Inflammatory Regulation in the Colon. Endocrinology. 2017,158(11),4064-4075. [CrossRef]

- Jin D; Wu S; Zhang YG; Lu R; Xia Y; Dong H; Sun J. Lack of Vitamin D Receptor Causes Dysbiosis and Changes the Functions of the Murine Intestinal Microbiome. Clin Ther. 2015, 7(5), 996-1009.e7. [CrossRef]

- Barbáchano A; Fernández-Barral A; Ferrer-Mayorga G; Costales-Carrera ; Larriba MJ; Muñoz A. The endocrine vitamin D system in the gut. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017, 453, 79-87. [CrossRef]

- Wang H; Tian G; Pei Z; Yu X; Wang Y; Xu F; Zhao J; Lu S; Lu W. Bifidobacterium longum increases serum vitamin D metabolite levels and modulates intestinal flora to alleviate osteoporosis in mice. mSphere. 2025, 10(3), e0103924. [CrossRef]

- Yang X; Zhu Q; Zhang L; Pei Y; Xu X; Liu X; Lu G; Pan J; Wang Y. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and serum vitamin D: evidence from genetic correlation and Mendelian randomization study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2022,76(7),1017-1023. [CrossRef]

- Ma C; Han M; Heinrich B; Fu Q; Zhang Q; Sandhu M; Agdashian D; Terabe M; Berzofsky JA; Fako V; Ritz T; Longerich T; Theriot CM; McCulloch JA; Roy S; Yuan W; Thovarai V; Sen SK; Ruchirawat M; Korangy; Wang XW; Trinchieri G; Greten TF. Gut microbiome-mediated bile acid metabolism regulates liver cancer via NKT cells. Science. 2018, 360(6391), eaan5931. [CrossRef]

- Song X; Sun X; Oh SF; Wu M; Zhang Y; Zheng W; Geva-Zatorsky N; Jupp R; Mathis D; Benoist C; Kasper DL. Microbial bile acid metabolites modulate gut RORγ+ regulatory T cell homeostasis. Nature. 2020,577(7790),410-415. [CrossRef]

- Sardar P; Beresford-Jones BS; Xia W, Shabana O; Suyama S; Ramos RJF; Soderholm AT; Tourlomousis P; Kuo P; Evans AC; Imianowski CJ; Conti AG; Wesolowski AJ; Baker NM; McCord EAL; Okkenhaug K; Whiteside SK; Roychoudhuri R; Bryant CE; Cross JR; Pedicord VA. Gut microbiota-derived hexa-acylated lipopolysaccharides enhance cancer immunotherapy responses. Nat Microbiol. 2025,10(3),795-807. [CrossRef]

- Zitvogel L; Ma Y; Raoult D; Kroemer G; Gajewski TF. The microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: Diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies. Science. 2018, 359(6382),1366-1370. [CrossRef]

- Routy B; Le Chatelier E; Derosa L; Duong CPM; Alou MT; Daillère R; Fluckiger A, Messaoudene M; Rauber C, Roberti MP; Fidelle M; Flament C; Poirier-Colame V; Opolon P; Klein C; Iribarren K; Mondragón L; Jacquelot N; Qu B; Ferrere G; Clémenson C; Mezquita L; Masip JR; Naltet C; Brosseau S; Kaderbhai C; Richard C; Rizvi H; Levenez F; Galleron N; Quinquis B; Pons N; Ryffel B; Minard-Colin V; Gonin P; Soria JC; Deutsch E; Loriot Y; Ghiringhelli F; Zalcman G; Goldwasser F; Escudier B; Hellmann MD; Eggermont A; Raoult D; Albiges L; Kroemer G; Zitvogel L. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018, 359(6371),91-97. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo JM. Vitamin D-dependent microbiota-enhancing tumor immunotherapy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2024,21(10),1083-1086. [CrossRef]

- Franco F; McCoy KD. Microbes and vitamin D aid immunotherapy. Science.2024, 384(6694), 384-385. [CrossRef]

- Kanno K; Akutsu T; Ohdaira H; Suzuki Y; Urashima M. Effect of Vitamin D Supplements on Relapse or Death in a p53-Immunoreactive Subgroup With Digestive Tract Cancer: Post Hoc Analysis of the AMATERASU Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023, 6(8), e2328886. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Barral A; Peña C; Pisano DG; Cantero R; Rojo F; Muñoz A; Larriba MJ. Vitamin D receptor expression and associated gene signature in tumour stromal fibroblasts predict clinical outcome in colorectal cancer. Gut.2017,66(8),1449-1462. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).