Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

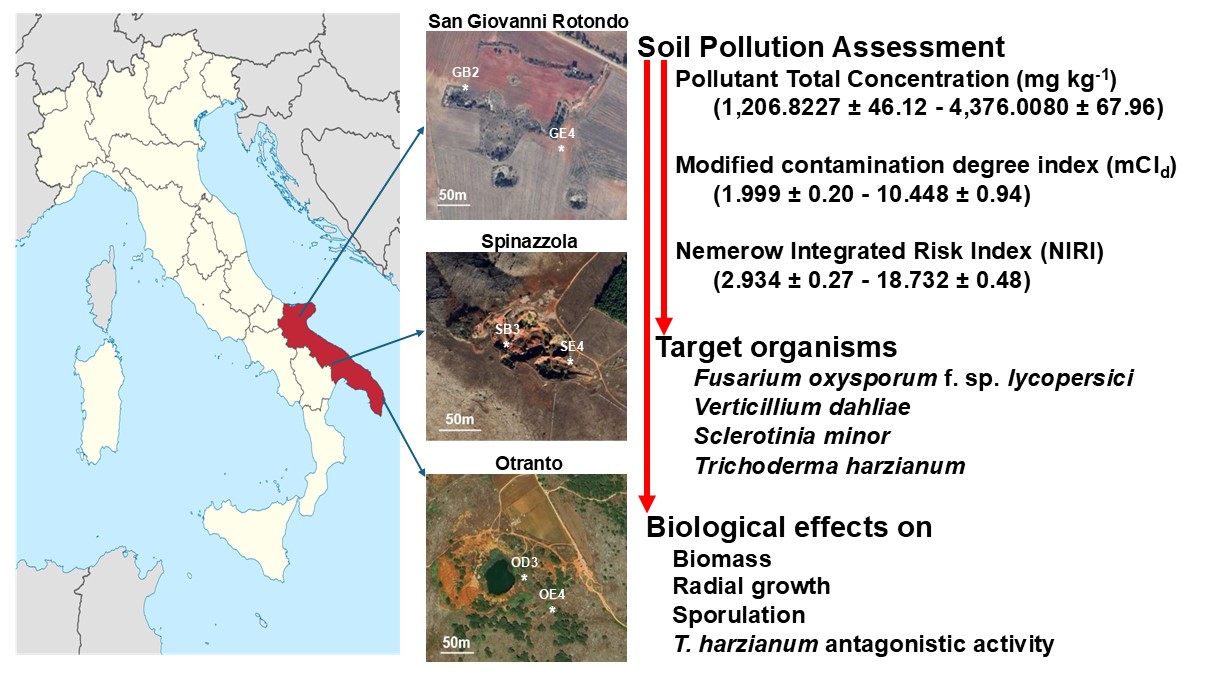

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains, Media, and Growth Conditions

2.2. Soil Sampling and Risk Assessment

| Elements | San Giovanni Rotondo [45,47,48] | Otranto [45,46,47] | Spinazzola [44,46,47] | |||

| GB2 | GE2 | OD3 | OE4 | SB3 | SE4 | |

| Arsenic (As) | bdl b | bdl | 44.300 ± 14.228 | 44.300 ± 14.228 | 56.909 ± 14.758 | 56.909 ± 14.758 |

| Barium (Ba) | 31.400 ± 8.683 | 31.400 ± 8.683 | 16.201 ± 1.436 | 16.201 ± 1.436 | 54.136 ± 17.651 | 54.136 ± 17.651 |

| Cobalt (Co) | 24.533 ± 8.975 | 24.533 ± 8.975 | 51.150 ± 3.319 | 51.150 ± 3.319 | 47.636 ± 28.954 | 47.636 ± 28.954 |

| Chromium (Cr) | 468.667 ± 10.257 | 468.667 ± 10.257 | 999.501 ± 64.521 | 999.501 ± 64.521 | 754.091 ± 23.661 | 754.091 ± 23.661 |

| Caesium (Cs) | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 6.600 ± 1.795 | 6.600 ± 1.795 |

| Copper (Cu) | bdl | bdl | 55.501 ± 7.591 | 55.501 ± 7.591 | bdl | bdl |

| Gallium (Ga) | 56.200 ± 12.718 | 56.200 ± 12.718 | 58.351 ± 5.244 | 58.351 ± 5.244 | 65.864 ± 9.131 | 65.864 ± 9.131 |

| Hafnium (Hf) | bdl | bdl | 12.147 ± 0.587 | 12.147 ± 0.587 | bdl | bdl |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | bdl | bdl | 7.051 ± 0.825 | 7.051 ± 0.825 | bdl | bdl |

| Niobium (Nb) | 81.800 ± 19.818 | 81.800 ± 19.818 | 75.101 ± 3.582 | 75.101 ± 3.582 | 112.727 ± 10.864 | 112.727 ± 10.864 |

| Nickel (Ni) | 197.333 ± 25.765 | 197.333 ± 25.765 | 190.501 ± 43.585 | 190.501 ± 43.585 | 458.182 ± 59.892 | 458.182 ± 59.892 |

| Rubidium (Rb) | bdl | bdl | bdl | bdl | 16.273 ± 7.953 | 16.273 ± 7.953 |

| Lead (Pb) | bdl | bdl | 94.151 ± 21.404 | 94.151 ± 21.404 | bdl | bdl |

| Strontium (Sr) | 27.600 ± 3.757 | 27.600 ± 3.757 | 54.301 ± 5.956 | 54.301 ± 5.956 | 14.682 ± 2.697 | 14.682 ± 2.697 |

| Thorium (Th) | bdl | bdl | 47.358 ± 9.756 | 47.358 ± 9.756 | bdl | bdl |

| Uranium (U) | bdl | bdl | 10.784 ± 10.777 | 10.784 ± 10.777 | bdl | bdl |

| Vanadium (V) | 346.800 ± 89.405 | 346.800 ± 89.405 | 206.351 ± 15.277 | 206.351 ± 15.277 | 482.000 ± 74.485 | 482.000 ± 74.485 |

| Zinc (Zn) | bdl | bdl | 265.509 ± 21.392 | 265.509 ± 21.392 | bdl | bdl |

| Zirconium (Zr) | bdl | bdl | 549.901 ± 18.049 | 549.901 ± 18.049 | 545.682 ± 41.891 | 545.682 ± 41.891 |

| ΣREE c | 944.77 ± 14.307 | 337.49± 10.703 | 687.75 ± 22.969 | 387.61 ± 29.369 | 1762.68 ± 22.174 | 826.51 ± 24.471 |

| Pollutant TotalConcentration | 1,814.1027 ± 88.08 | 1,206.8227 ± 46.12 | 3,426.2600 ± 19.49 | 3,126.1200 ± 32.31 | 4,376.0080 ± 67.96 | 3,439.8380 ± 98.23 |

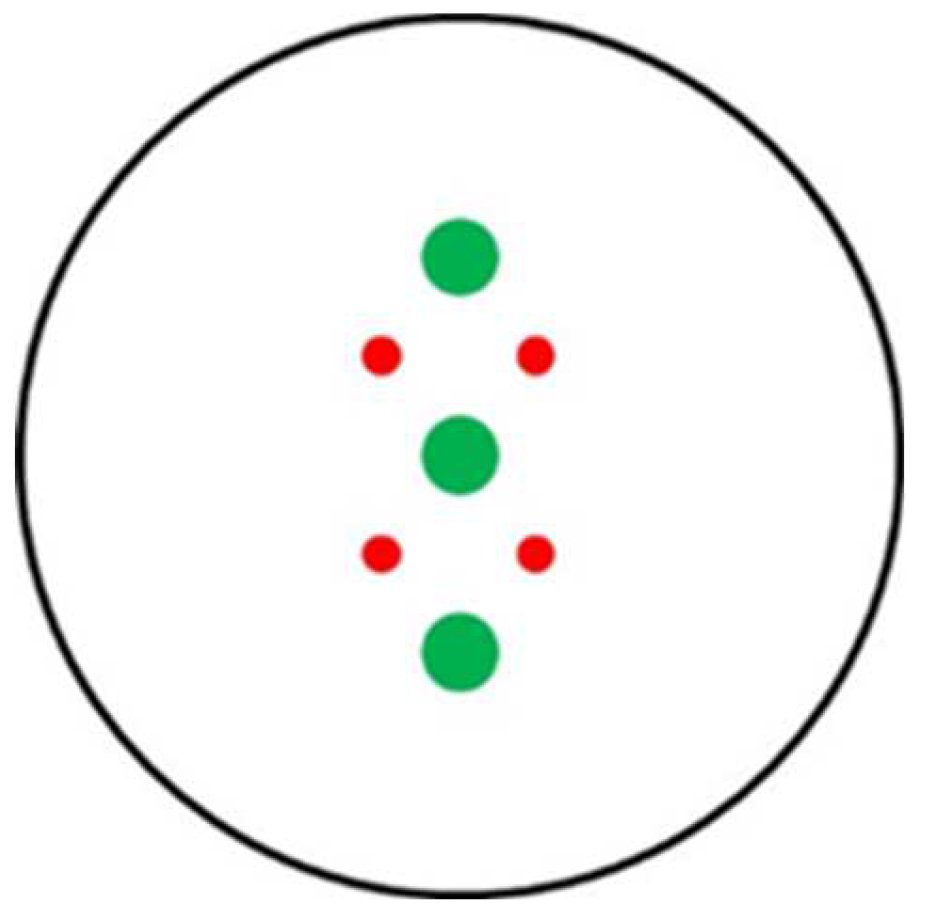

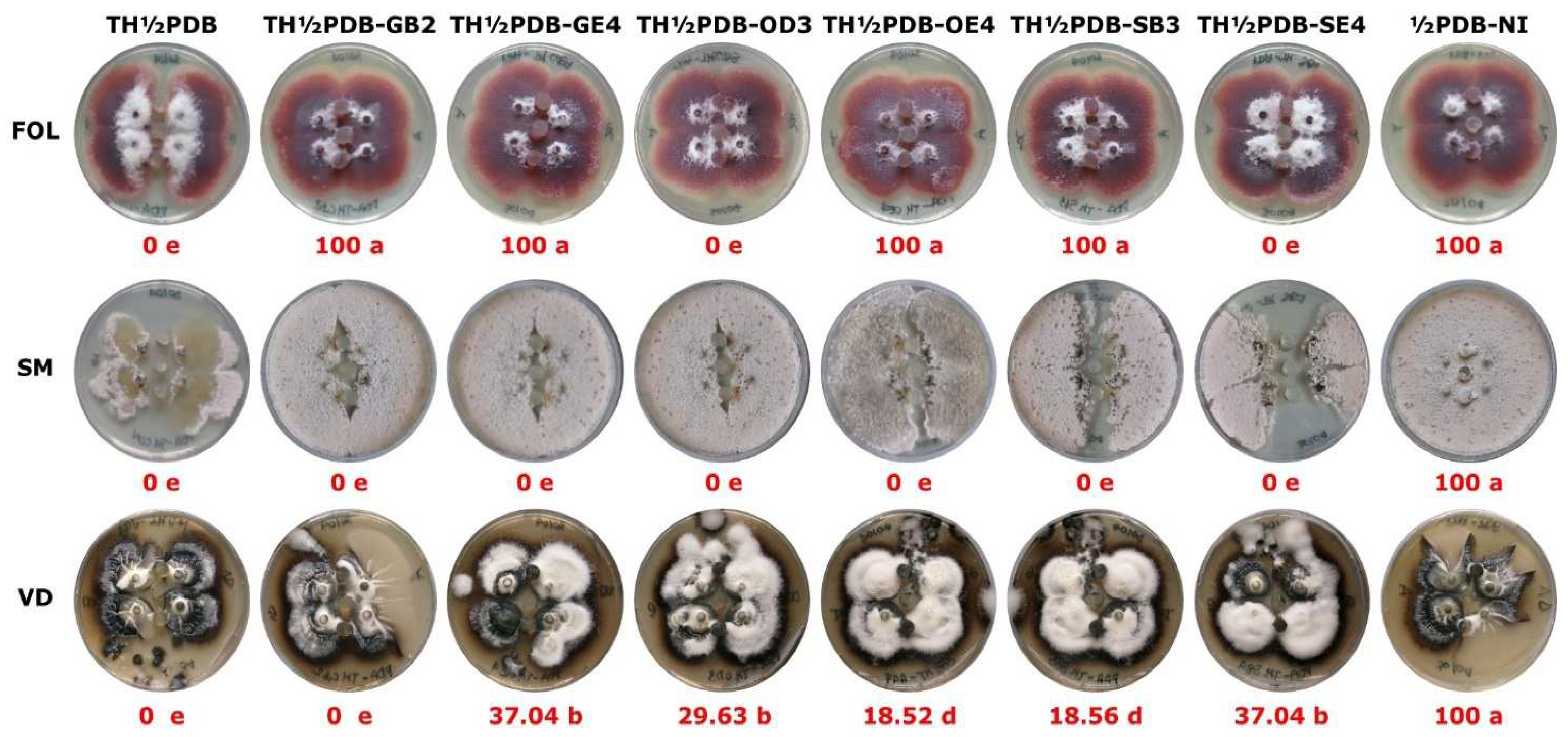

2.3. In Vitro Assay on Target Organisms

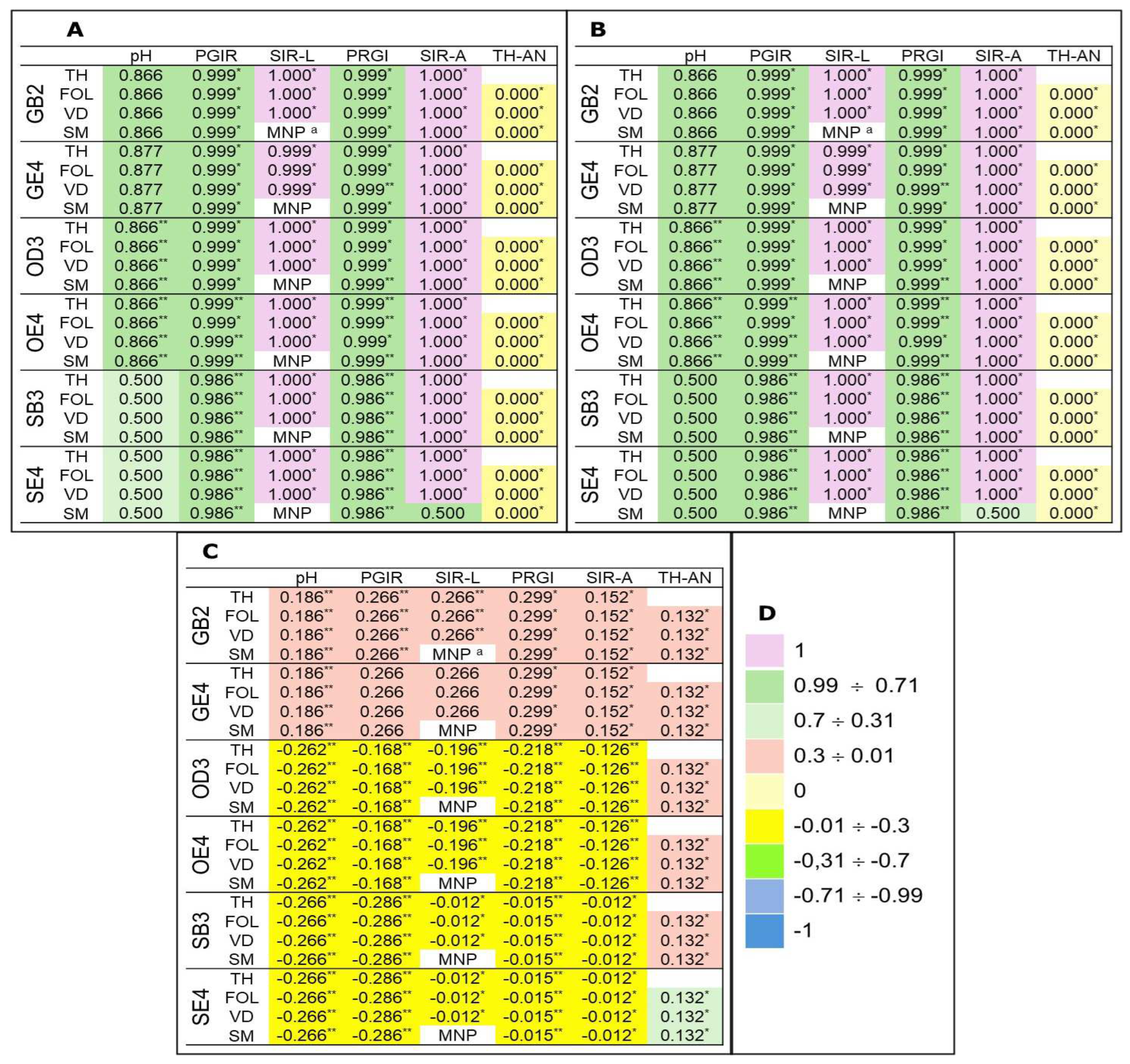

2.4. Effects on Trichoderma Harzianum Antagonistic Activity

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Characterization

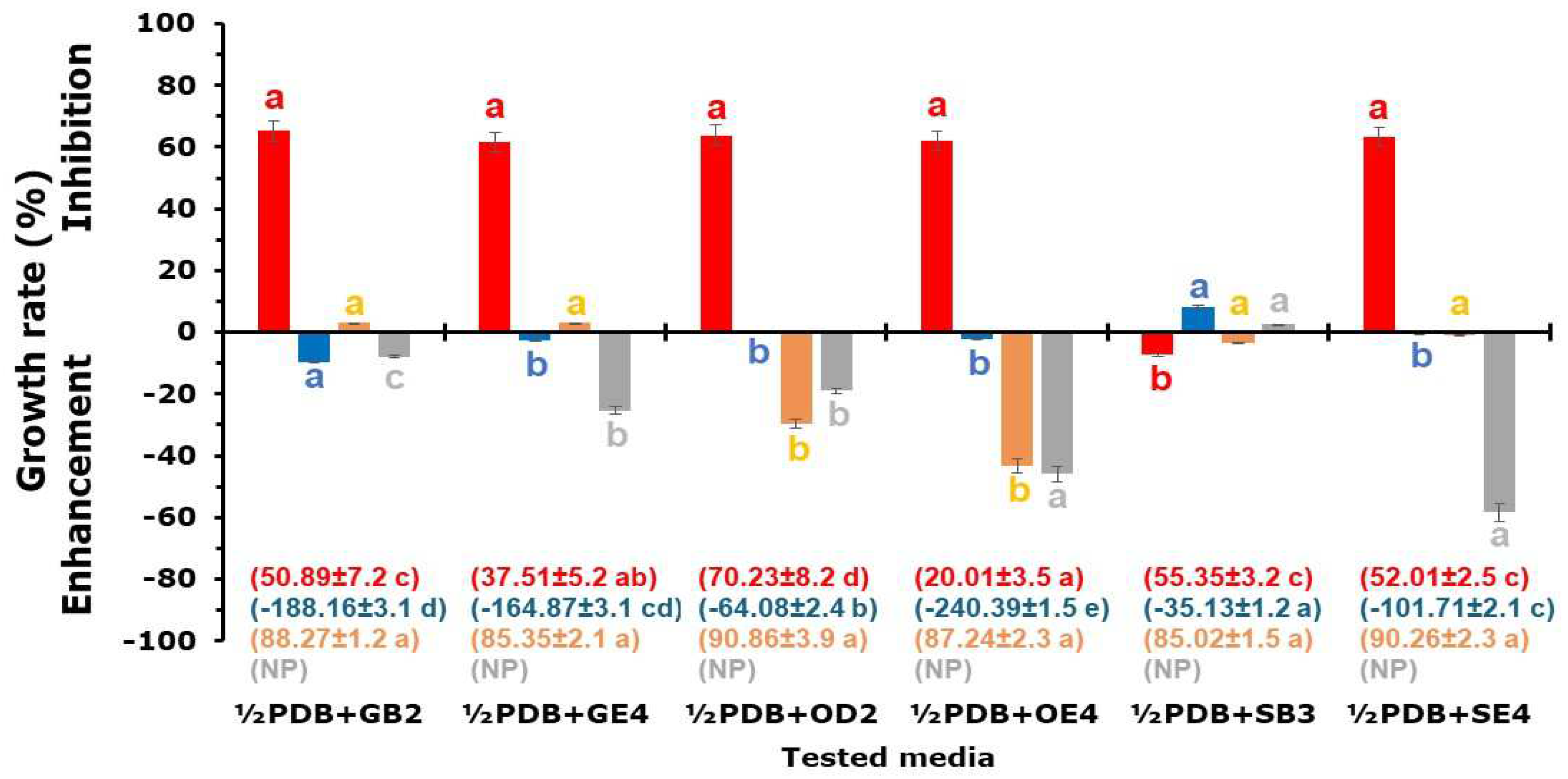

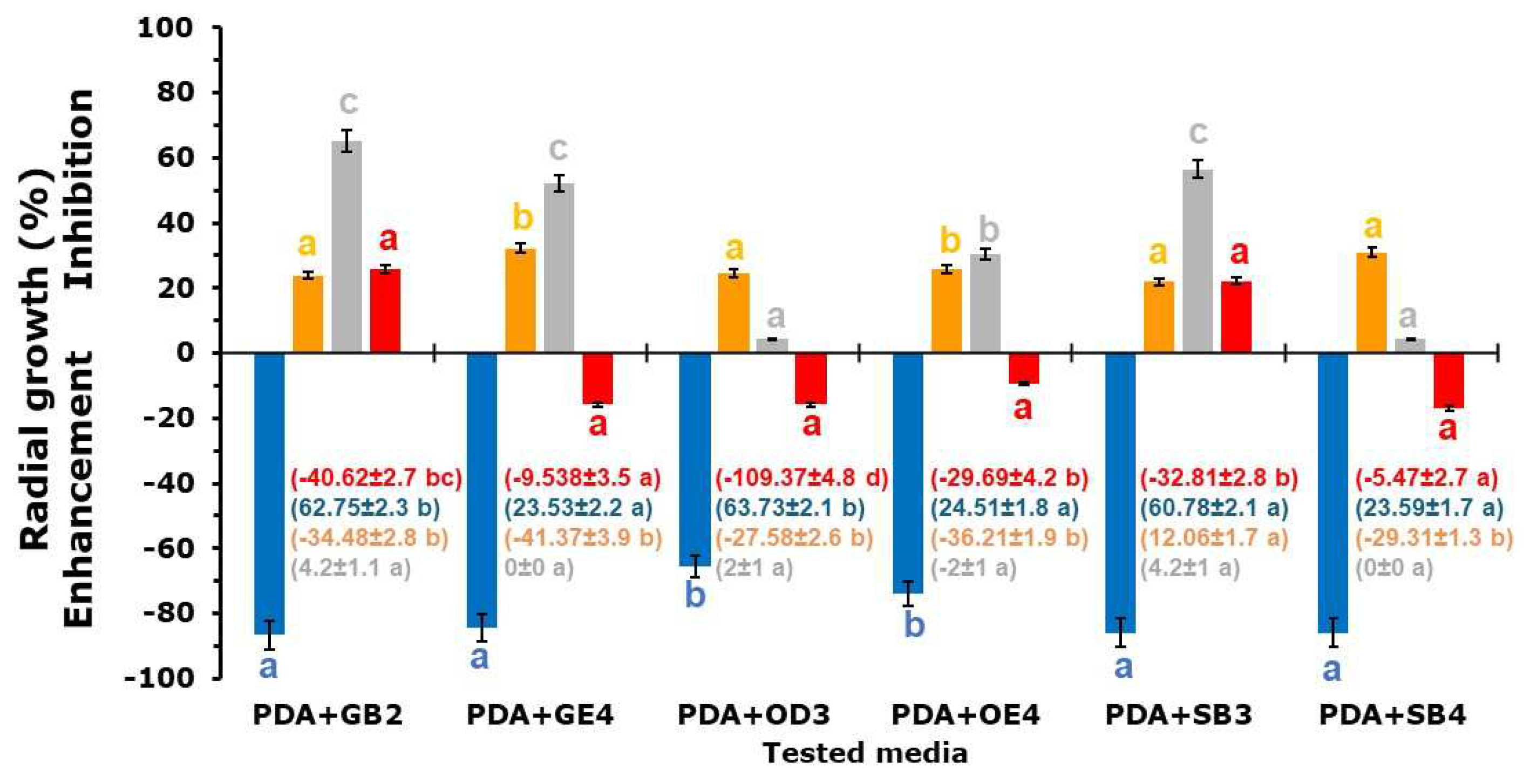

3.2. Effects of Soil Samples on Target Organisms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varriale, R.; Aldighieri, B.; Genovese, L. Dismissed mines: from the past to the future. Heritage 2023, 6, 2152–2185. [CrossRef]

- Masinga, P.; Simbanegavi, T.T.; Makuvara, Z.; Marumure J.; Chaukura N.; Gwenzi W. Emerging organic contaminants in the soil–plant-receptor continuum: transport, fate, health risks, and removal mechanisms. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 367. [CrossRef]

- Järup, L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 167–82. [CrossRef]

- Zoroddu, M.A.; Aaseth, J.; Crisponi, G.; Medici, S.; Peana, M.; Nurchi, V.M. The essential metals for humans: a brief overview. J. Inor. Biochem. 2019, 195, 120–129. [CrossRef]

- Peana, M.; Pelucelli, A.; Medici, S.; Cappai, R.; Nurchi, V.M.; Zoroddu, M.A. Metal toxicity and speciation: a review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28(35), 7190–7208. [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.T.; Azam, M.; Siddiqui, K.; Ali, A.; Choi, I.; Haq, Q.M. Heavy metals and human health: mechanistic insight into toxicity and counter defense system of antioxidants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16(12), 29592–29630. [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, E.; Priyadarshini, S.S.; Cousins, B.G.; Pradhan, N. Metal-fungus interaction: review on cellular processes underlying heavy metal detoxification and synthesis of metal nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2021, 274, 129976. [CrossRef]

- Dalvi, A.A.; Bhalerao, S.A. Response of plants towards heavy metal toxicity: an overview of avoidance, tolerance and uptake mechanism. Ann. Plant Sci. 2013, 2, 362–368.

- Mohamadhasani, F.; Rahimi, M. Growth response and mycoremediation of heavy metals by fungus Pleurotus sp. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19947. [CrossRef]

- Giller K.E.; Witter E.; Mcgrath S.P. Toxicity of heavy metals to microorganisms and microbial processes in agricultural soils: a review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1998, 30(10–11), 1389-1414. [CrossRef]

- Igiri, B.E.; Okoduwa, S.I.R.; Idoko, G.O.; Akabuogu, E.P.; Adeyi, A.O.; Ejiogu, I.K. Toxicity and bioremediation of heavy metals contaminated ecosystem from tannery wastewater, a review. J. Toxicol. 2018, 2568038. [CrossRef]

- Del Val C.; Barea J.M.; Azcón-Aguilar C. Diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus populations in heavy-metal- contaminated soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65(2), 718-723. [CrossRef]

- Bano, A.; Hussai, J.; Akbarm, A.; Mehmood, K.; Anwar, M.; Hasni, M.S.; Ullah, S.; Sajid, S.; Ali, I. Biosorption of heavy metals by obligate halophilic fungi. Chemosphere 2018, 199, 218–222. [CrossRef]

- Graz, M.; Pawlikowska-Pawlega, B.; Jarosz-Wilkolazka, A. Growth inhibition and intracellular distribution of Pb ions by the white-rot fungus Abortiporus biennis. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegra. 2011, 65(1), 124–129. [CrossRef]

- Lilly, W.W.; Wallweber, G.J.; Lukefahr, T.A. Cadmium absorption and its effects on growth and mycelial morphology of the basidiomycete fungus, Schizophyllum commune. Microbios 1992, 72, 227–237.

- Mohan, P.M.; Pratap Rudra, M.P.; Sastry, K.S. Nickel transport in nickel–resistant strains of Neurospora crassa. Curr. Microbiol. 1984, 10, 125–128. [CrossRef]

- Haque, N.; Hughes, A.; Lim, S.; Vernon, C. Rare earth elements: overview of mining, mineralogy, uses, sustainability and environmental impact. Resources 2014, 3, 614–635. [CrossRef]

- Arciszewska, Ż.; Gama, S.; Leśniewska, B.; Malejko, J.; Nalewajko-Sieliwoniuk, E.; Zambrzycka-Szelewa, E.; Godlewska-Żyłkiewicz, B. The translocation pathways of rare earth elements from the environment to the food chain and their impact on human health. Process Saf. Environ. 2022, 168, 205–223. [CrossRef]

- Tommasi, F.; Thomas, P.J.; Pagano, G.; Perono, G.A.; Oral, R.; Lynos, D.M.; Toscanesi, M.; Trifuoggi, M. Review of rare earth elements as fertilizers and feed additives: a knowledge gap analysis. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 81(4), 531–540. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, G.; Aliberti, F.; Guida, M.; Oral, R.; Sicialiano, A.; Trifuoggi, M.; Tommasi, F. Rare earth elements in human and animal health: state of art and research priorities. Environ. Research 2015, 142, 215–220. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Richter, H.; Sparovek, G.; Schnug, E. Physiological and biochemical effects of rare earth elements on plants and their agricultural significance: a review. J. Plant. Nutr. 2004, 27(1), 183–220. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Shen, L.; Feng, C.; Yang, R.; Qu, J.; Ju, H.; Zhang, Y. Distribution of rare earth elements (REEs) and their roles in plant growth: a review. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 298, 118540. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, G. Rare earth elements in soil and plant systems—a review. Plant Soil 2004, 267(1–2), 191–206. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.W.; Ghio, A.J.; Sheehan, C.E.; Bernhardt, P.F.; Roggli, V.L. Rare earth (Cerium oxide) pneumoconiosis: analytical scanning electron microscopy and literature review. Modern Pathol. 1995, 8, 859–865.

- Tong, S.L.; Zhu, W.Z.; Gao, Z.H.; Meng, Y.X.; Peng, R.L.; Lu, G.C. Distribution characteristics of rare earth elements in children’s scalp hair from a rare earths mining area in southern China. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. A 2004, 39(9), 2517–2532. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E.J.; Schmidt-Lauber, C.; Kay, J. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a systemic fibrosing disease resulting from gadolinium exposure. Best Prac. Res. Cl. Rh. 2012, 26, 489–503. [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, J.; Ye, B.; Liang, T. Rare earth elements in human hair from a mining area of China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 96, 118–123. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, G.; Guida, M.; Tommasi, F.; Oral, R. Health effects and toxicity mechanisms of rare earth elements-knowledge gaps and research prospects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015, 115(5), 40–48. [CrossRef]

- Brouziotis, A.A.; Giarra, A.; Libralato, G.; Pagano, G.; Guida, M.; Trifuoggi, M. Toxicity of rare earth elements: an overview on human health impact. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 948041. [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.; Karakoti, A.; Graham, R.P.; Maguire, J.L.; Reilly, C.M.; Seal, S.; Rattan, R.; Shridhar, V. Nanoceria: A rare-earth nanoparticle as a novel anti-angiogenic therapeutic agent in ovarian cancer. PLoS One 2013, 8(1), e54578. [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, T.; Ymamoto, A.; Kazaana, A.; Nakano, Y.; Nojiri, Y.; Kashiwazaki, M. Antibacterial, antifungal and nematocidal activities of rare earth ions. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016, 174(2), 464e470. [CrossRef]

- Tommasi, F.; d’Aquino, L. Rare earth elements and plants. In Rare Earth Elements in Human and Environmental Health: At the Crossroad Between Toxicity and Safety; Pagano G. Ed.; Pan Stanford Publishing Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2017; pp. 107–125.

- Zicari, M.A.; d’Aquino, L.; Paradiso, A, Mastrolitti, S.; Tommasi, F. Effect of cerium on growth and antioxidant metabolism of Lemna minor L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 163, 536–543. [CrossRef]

- Gjata, I.; Tommasi, F.; De Leonardis, S.; Dipierro, N.; Paciolla, C. Cytological alterations and oxidative stress induced by Cerium and Neodymium in lentil seedlings and onion bulbs. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 969162. [CrossRef]

- Gjata, I.; van Drimmelen, C.K.E.; Tommasi, F. Paciolla, C.; Heise, S. Impact of rare earth elements in sediments on the growth and photosynthetic efficiency of the benthic plant Myriophyllum aquaticum. J. Soil. Sediment. 2024, 24, 3814–3823. [CrossRef]

- d’Aquino, L.; Morgana, M.; Carboni, M.A.; Staiano, M.; Vittori Antisari, M.; Re, M.; Lorito, M.; Vinale, F.; Abadi, K.M.; Woo, S.L. Effect of some rare earth elements on the growth and lanthanide accumulation in different Trichoderma strains. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41(12), 2406–2413. [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, M.C.; Garcia, O.; Melnikov, P. Neodymium biosorption from acidic solutions in batch system. Process Biochem. 2000, 36(5), 441–444. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Lian, B. Bioleaching of rare earth and radioactive elements from red mud using Penicillium tricolor RM-10. Bioresource Technol. 2013, 136, 16–23. [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, A.; Symeopoulos, B.; Bourikas, K.; Koutinas, A.A. A comparative study of neodymium uptake by yeast cells. Radiochim. Acta 2008, 97(8), 437–441.

- Tsuruta, T. Accumulation of rare earth elements in various microorganisms. J. Rare Earth. 2007, 25, 526–532. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, B.J. Hormetic mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2013, 43, 580–606. [CrossRef]

- d’Aquino, L.; Tommasi, F. Rare Earth Elements and Microorganism. In Rare Earth Elements in Human and Environmental Health: At the Crossroad Between Toxicity and Safety; Pagano G. Ed.; Pan Stanford Publishing Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2017; 127–141.

- Hassan, SH.A.; Van Ginkel, S.W.; Hussein, M.A.M.; Abskharon, R.; Oh, S-E. Toxicity assessment using different bioassays and microbial biosensors. Environ. Int. 2016, 92–93, 106–118. [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, G.; Boni, M.; Buccione, R.; Sinisi, R. Geochemistry of the Apulian karst bauxites (southern Italy): chemical fractionation and parental affinities. Ore Geol. Rev. 2014, 63, 9–21. [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, G.; Buccione, R.; Gueguen, E.; Langone, A.; Sinisi R. Geochemistry of the Apulian allochthonous karst bauxite, Southern Italy: distribution of critical elements and constraints on Late Cretaceous Peri-Tethyan palaeogeography. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 77, 246–259. [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, G.; Boni, M.; Oggiano, G.; Mameli, P.; Sinisi R.; Buccione, R.; Mondillo, N. Critical metals distribution in Tethyan karst bauxite: the cretaceous Italian ores. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 86, 526–536. [CrossRef]

- Sinisi, R. Cretaceous bauxite from San Giovanni Rotondo (Apulia, Southern Italy): a provenance tool. Minerals 2018, 8, 567. [CrossRef]

- Brouziotis, A.A.; Heise, S.; Saviano, L.; Zhang, K.; Giarra, A.; Bau, M.; Tommasi, F.; Guida, M.; Libralato, G.; Trifuoggi, M. Levels of rare earth elements on three abandoned mining sites of bauxite in southern Italy: a comparison between TXRF and ICP-MS. Talanta 2024, 275, 126093. [CrossRef]

- Toussoun, T.A.; Nelson, P.E. A pictorial guide to the identification of Fusarium species according to the taxonomic system of Snyder and Hansen. The Pennsylvania State University Press: London, UK, 1968.

- Sudarningsih, S.; Fahruddin, F.; Lailiyanto, M.; Noer, A.A.; Husain, S.; Siregar, S.S.; Wahyono, S.C.; Ridwan, I. Assessment of soil contamination by heavy metals: a case of vegetable production center in Banjarbaru Region, Indonesia. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 249–257. [CrossRef]

- Cao Z.; Qian H.; Gao Y.; Li K.; Liu Y.; Shi X, Li, S.; Zhao, W.; Yang, S.; Tian, P.; Wu, P.; Ma, Y. Ecological risk assessment and source identification of heavy metals in the sediments of the Danjiang River Basin: a quantitative method combining multivariate analysis and the APCS-MLR model. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 175, 113518. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Shahab, A.; Xi, B.; Chang, Q.; You, S.; Li, J.; Sun, X.; Huang, H.; Li, X. Heavy metal pollution, ecological risk, spatial distribution, and source identification in sediments of the Lijiang River. China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116189. [CrossRef]

- Men, C.; Liu, R.; Xu, L.; Wang, Q.; Guo, L.; Miao, Y.; Shen, Z. Source-specific ecological risk analysis and critical source identification of heavy metals in road dust in Beijing. China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 121763. [CrossRef]

- Miot, H.A. Correlation analysis in clinical and experimental studies. J, Vasc. Bras. 2018, 17, 275–279. [CrossRef]

- Klaus-Joerger, T.; Joerger, R.; Olsson, E.; Granqvist, C-G. Bacteria as workers in the living factory: metal-accumulating bacteria and their potential for materials science. Trends Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 15–20. [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, H.; Yamamoto, H. Interactions of microorganisms with rare earth ions and their utilization for separation and environmental technology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97(1), 1–8. Epub 2012 Nov 1. [CrossRef]

- Lipman, C.B.; Burgess, P.S. The effects of copper, zinc, iron and lead salts on ammonification and nitrification in soils. Univ. Calif. Publ. Agric. Sci. 1914, 1,127–139.

- Brown, P.E.; Minges, G.A. The effect of some manganese salts on ammonification and nitrification. Soil Science 1916, 2, 67-85.

- Micheletti, F.; Fornelli, A.; Spalluto, L.; Parise, M.; Gallicchio, S.; Tursi, F.; Festa, V. Petrographic and geochemical inferences for genesis of terra rossa: a case study from the Apulian Karst (Southern Italy). Minerals 2023, 13, 499. [CrossRef]

- Vilas Boas, H.F.; Almeida, L.F.J.; Teixeira, R.S.; Souza, I.F.; Silva, I.R. Soil organic carbon recovery and coffee bean yield following bauxite mining. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1565–1573. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.K.; Lal, R. Changes in physical and chemical properties of soil after surface mining and reclamation. Geoderma 2011, 161(3-4), 168–176. [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.Y.; Zhu, X.Q.; Tang, H.S.; Du, S.J.; Gu, J. Geology and geochemistry of the Xiaoshanba bauxite deposit, Central Guizhou Province, SW China: implications for the behavior of trace and rare earth elements. J. Geochem. Explor. 2018, 190, 170–186. [CrossRef]

- Atibu, E.K.; Devarajan, N.; Laffite, A.; Giuliani, G.; Salumu, J.A.; Muteb, R.C. Mulaji, C.K.; Otamonga, J.-P.; Elongo, V.; Mpiana, P.T.; Poté, J. Assessment of trace metal and rare earth elements contamination in rivers around abandoned and active mine areas. The case of Lubumbashi River and Tshamilemba Canal, Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. Geochemistry 2016, 76(3), 353–362. [CrossRef]

- Nkrumah, P.N.; Erskine, P.D.; Erskine, J.D.; Van Der Ent, A. Rare earth elements (REE) in soils and plants of a uranium-REE mine site and exploration target in Central Queensland, Australia. Plant Soil 2021, 464(1–2), 375–389. [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, N.; Proenza, J.A.; Villanova-de-Benavent, C.; Aiglsperger, T.; Bover-Arnal, T.; Torró, L.; Salas, R.; Dziggel, A. Geochemistry and mineralogy of rare earth elements (REE) in Bauxitic ores of the Catalan Coastal Range, NE Spain. Minerals 2018, 8(12), 562. [CrossRef]

- Trifuoggi, M.; Pagano, G.; Oral, R.; Gravina, M.; Toscanesi, M.; Mozzillo, M.; Siciliano, A.; Burić, P.; Lyons, D.M.; Palumbo, A.; Thomas, P.J.; D’Ambra, L.; Crisci, A.; Guida, M.; Tommasi, F. Topsoil and urban dust pollution and toxicity in Taranto (southern Italy) industrial area and in a residential district. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191(1), 43. [CrossRef]

- Tommasi, F.; Lyons, D.M, Pagano, G.; Kovaçic, I.; Trifuoggi, M. Geospatial pattern of topsoil pollution and multi-endpoint toxicity in the petrochemical area of Augusta-Priolo (eastern Sicily, Italy). Chemosphere 2023, 333, 138802. [CrossRef]

- Naz, M.; Dai, Z.; Hussain, S.; Tariq, M.; Danish, S.; Khan, I.U.; Qi, S.; Du, D. The soil pH and heavy metals revealed their impact on soil microbial community. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 321, 115770. [CrossRef]

- Prematuri, R.; Turjaman, M.; Sato, T.; Tawaraya, K. Post Bauxite mining land soil characteristics and its effects on the growth of Falcataria moluccana (Miq.) Barneby & J. W. Grimes and Albizia saman (Jacq.) Merr. Appl. Envir. Soil Sci. 2020, 6764380. [CrossRef]

- Maurya, S.; Dubey, S.; Kumari, R.; Verma, R. Management tactics for fusarium wilt of tomato caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (Sacc.): a review. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 4(5), 1–7.

- Olivier, R.P. Agrios’ Plant Pathology, 6th Ed. Academic Press: London, UK, 2024.

- Pegg, G.F.; Brady, B.L. Verticillium Wilts. CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2002.

- Vinale, F.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Ghisalberti, L.E.; Marra, R.; Woo, L.S.; Lorito M. Trichoderma-plant-pathogen interactions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Vinale, F.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Ghisalberti, E.L.; Ruocco, M.; Woo, S.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma secondary metabolites that affect plant metabolism. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 1545–1550. [CrossRef]

- Zin, N.A.; Badaluddin, N.A. Biological functions of Trichoderma spp. for agriculture applications. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2020, 65(2), 168–178. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.C.; Rayner, A.D.M. Ecology of Saprotrophic Fungi. Longman Publishing: London, UK, 1984.

- Miao, L.; Kwong, T.F.N.; Qian, P-Y. Effect of culture conditions on mycelial growth, antibacterial activity, and metabolite profiles of the marine-derived fungus Arthrinium c.f. saccharicola. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 72,1063–1073. [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Qu, X.; Chen, F.; Bao, J.; Zhang, G.; Luo, Y. Camptothecin-producing endophytic fungus Trichoderma atroviride LY357: isolation, identification, and fermentation conditions optimization for camptothecin production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97(21), 9365–9375. [CrossRef]

- VanderMolen, K.M.; Raja, H.A.; El-Elimat, T.; Oberlies, N.H. Evaluation of culture media for the production of secondary metabolites in a natural products screening program. AMB Express 2013, 3(1), 71. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Soil samples a,b | |||||

| GB2 | GE4 | OD3 | OE4 | SB3 | SE4 | |

| pH | 8.34±0.12a | 8.24±0.15a | 8.01±0.11ab | 7.89±0.13b | 8.04±0.14ab | 8.42±0.12a |

| mCId | 3.891±0.52d | 1.999±0.20e | 5.324±0.21b | 4.555±0.07c | 10.448±0.94a | 6.703±0.46b |

| NIRI | 2.934±0.27c | 2.934±0.27c | 15.533±0.45b | 15.533±0.49b | 18.732±0.48a | 18.732±0.48a |

| Media | ½PDB NId | FOL | VD | TH | SM |

| ½PDB | 5.61±0.1 a | 5.13±0.1 a | 4.54±0.1 a | 3.82±0.1 a | 3.82±0.1 a |

| ½PDB+GB2 | 6.02±0.1 b | 6.18±0.1 b | 5.06±0.1 ab | 4.21±0.1 ab | 4.22±0.1 ab |

| ½PDB+GE4 | 5.99 ±0.1 b | 6.11±0.1 b | 5.11±0.1 b | 3.93±0.1 a | 3.91±0.1 a |

| ½PDB+OD3 | 6.08±0.1 b | 5.18±0.1 a | 4.59±0.1 a | 4.21±0.1 ab | 4.21±0.1 ab |

| ½PDB+OE4 | 6.02±0.1 b | 5.08±0.1 a | 4.94±0.1 a | 3.85±0.1 a | 3.85±0.1 a |

| ½PDB+SB3 | 6.06±0.1 b | 5.12±0.1 a | 5.01±0.1 ab | 4.61±0.1 b | 4.63±0.1 b |

| ½PDB+SE4 | 6.02±0.1 b | 6.11±0.1 b | 4.85±0.1 a | 3.76±0.1 ab | 3.73±0.1 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).