1. Introduction

Understanding the dynamics of futures price volatility is very important for many aspects of risk management, such as hedging, portfolio construction, derivatives pricing and many other. Samuelson was the first who investigated the relation between volatility and time until contract expiration, stating the hypothesis that the volatility of futures price changes should increase as the delivery date nears. This prediction is very well known and referred to as

Samuelson hypothesis, or

maturity effect,

1] This backwardation of volatility of forward contracts arises across most markets but this effect is especially pronounced in energy markets, as a particular steep increase in volatility occurs in the last six (or less) months of the life of the contract. This is one of the most fascinating phenomenon of commodity futures, which must be taken into account in pricing and managing of commodity contracts.

To illustrate the importance of this effect, we start with a simple example. We consider a future contract on WTI with expiration in

years priced at

per barrel. Assume that the implied volatility quoted for this contract is

and we consider an ATM call option on this future expiring

months before the contract expiration, thus in

years. Such options are called

early exercise options. The total variance during the lifetime of the contract will be

. If we price the option using the quoted implied volatility, the price of the early exercise ATM call option will be

per unit (no discount). However, under Samuelson effect the variance does not accumulate in uniform fashion, and such calculation will be wrong. Suppose we have a strong Samuelson, so that a half of the total variance happens in the last three months of the life of the contract. In such case, to price the option we have to use the volatility:

The right option price is , and ignoring the presence of Samuelson leads to overpricing the option by .

Now, let’s analyze the consequences of using a wrong variance for the second part of the time, the last three months of the lifetime of the contract. Since a half of the total variance realizes during a short period of time of three months, the average volatility

corresponding to the last three months, will be much higher:

Assume that in

years we have a right to buy a call option for premium

, and the strike

of the call option equal to the current forward price

. Thus we consider a compound option with payoff:

where

is the Black call price with price

F of the underlying asset, strike

, volatility

and time to expiration

. We can price the compound option by using standard numerical procedures ( grid evaluation or Monte Carlo). Even though the right

with Samuelson is higher than with flat Samuelson, the expectation of the underlying call option

is the same in two scenarios (we use a risk neutral pricing). However, the distribution of future prices in

years with flat Samuelson is much wider ( standard deviation of future price of

vs

), which makes the compound option more expensive under flat Samuelson

vs with Samuelson

. Disregarding Samuelson results in overpricing the option by

.

Another examples of an early exercise options include swaptions, which are widespread products in Energy Markets. Their evaluation is discussed in [

2]. Samuelson effect must be taken into account in evaluation of path dependent options, such as extendibles, calculations of forward exposure of a portfolio, necessary for CVA computations; hedging decisions and many other.

Numerous studies have investigated the Samuelson hypothesis empirically, and it has been supported in a subset of markets. Many of them arrive to mixed conclusions. For example, Miller [

3] investigates live cattle, Barnhill et al. [

4] study U. S. Treasury bonds; Adrangi et.al [

5] consider selected energy; Adrangi and Chatrath [

6] analyze coffee, sugar, and cocoa. Andersen [

7] finds evidence in the agricultural markets, such as wheat, oats, soybean mean, cocoa, but not for silver. Milonas [

8] finds strong support for the hypothesis in agricultural markets, but little or no support when using gold, copper, GNMA, T-bond, and T-bill prices. Rutledge (1976) finds support for the Samuelson hypothesis with silver and cocoa, but inconclusive evidence for wheat and soybean oil. Galloway and Kolb [

10] study the term structure of volatility in 45 markets, including agricultural and energy commodity futures, precious and industrial metal futures, and stock index, currency, and interest rate futures. Their findings provide support for the maturity effect in agricultural and energy commodities, but not in precious metals and financials. Liu [

11] employs almost stochastic dominance and the power spectrum to investigate the maturity effect for five groups of energy futures, such as crude oil, reformulated regular gasoline, RBOB regular gasoline, No. 2 heating oil, and propane. The outcome provides mixed results, ranging from supporting, to being contrary to the hypothesis. Jaeck and Lautier [

12] find evidence of a Samuelson effect in various electricity markets, such as German, Nordic, Australian and US, and show that storage is not a necessary condition for such an effect to appear.

"Negative" papers rejecting the hypothesis include Grammatikos and Saunders [

13] , who find no relation between futures return volatility and time-to-maturity for currency futures prices, and a study by Park and Sears [

14] which provides evidence to disprove the Samuelson hypothesis for stock index. The well known study by Bessembinder et al. [

15] suggests that the hypothesis will be generally supported in markets where spot price changes include a predictable temporary component, which likely to be met in real assets than for financial assets. They show that the hypothesis will generally be supported in markets where spot prices and convenience yields are positively correlated. The authors assume the carry arbitrage model represents futures markets.

The carry arbitrage model is based on the notion that the underlying instrument can be ‘‘carried” (purchased) with

financing (borrowing) and delivered against a short futures position. Brooks [

16] identifies and explores the important link between the empirical Samuelson hypothesis and theoretical carry: the degree to which carry arbitrage is empirically validated is associated with the degree to which the Samuelson hypothesis is not supported. In the continuation of the research, Brooks and Teterin [

17] study the volatility term structure in 10 futures markets comprising three categories: agriculture, energy, and metals. To estimate the slope of the volatility term structure they use the Nelson and Siegel [

18] functional form, borrowed from the literature on modeling the term structure of interest rates. The authors show that the slope of the volatility term structure is more negative when inventories are low and that the threshold for high/low inventory is specific to each market. The relationship between the Samuelson hypothesis and inventory levels is rooted in the cost-of-carry model

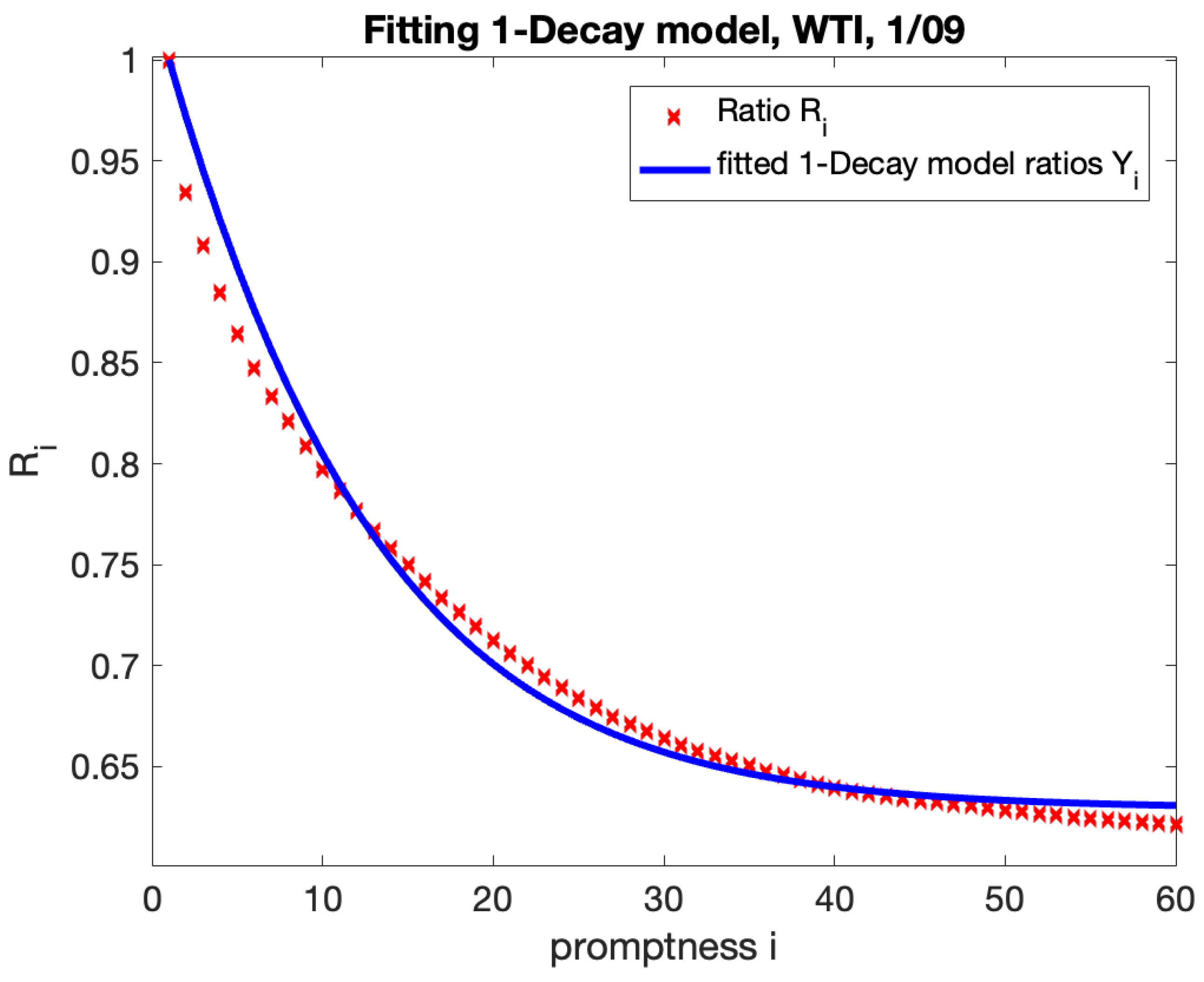

The popular models in the academic literature arrive to the Samuelson effect of futures volatility by considering models formulated in terms of the spot energy price with mean reverting process, see Clewlow and Strickland [

19] The Schwatz single factor model, [

20] results in the exponential decay of future volatility:

where

is the mean reversion rate, and

is the spot price volatility. The long term level of volatilities at

is zero, which is not realistic. Two factors models with mean reverting processes for spot price and convenience yield, see Schwartz (1997), Gibson and Schwartz [

21], Pilipović [

22], result in an exponential decay of futures volatility with non-zero long term level volatility at long horizons.

The vital paper by Schwartz and Trolle [

23] expands the framework of spot models to accommodate unspanned stochastic volatility. In their approach, the volatility of both spot price and forward cost of carry depend on two volatility factors which follow a mean reverting process, resulting in Samuelson effect for futures volatility. Crosby and Frau [

24] broaden [

23] model by incorporating multiple jump processes. They explore the valuation of plain vanilla options on futures prices when the spot price follows a log-normal process, the forward cost of carry curve and the volatility are stochastic variables, and the spot price and the forward cost of carry allow for time-dampening jumps. Frau and Fanelli [

25] present a new term-structure model for commodity futures prices based on [

23], which they extend by incorporating seasonal stochastic volatility represented with two different sinusoidal expressions and price plain vanilla options on the Henry Hub natural gas futures contracts. Hillard and Hillard [

26] develop a jump-diffusion model for pricing and hedging with margined options on futures. They introduce a jump diffusion process for spot prices, and mean reverting processes for interest rate and stochastic convenience yield. Under positive correlations between diffusion parts futures volatility increases as maturity approaches. Model parameter are calibrated using data on Brent crude contracts.

Another class of models deal with modeling futures directly, not through spot prices and unobservable convenience yield. Chiarella et al. [

27] propose a model encompassing hump-shaped, unspanned stochastic volatility, which entails a finite-dimensional affine model for the commodity futures curve and quasi-analytical prices for options on commodity futures. Schnieder and Tavin [

28] introduce a futures-based model able of capturing the main features displayed by Crude Oil futures and options contracts, such as the Samuelson volatility effect and the volatility smile. They calculate the joint characteristic function of two futures contracts in the model in analytic form and use it to price calendar spread options.

Since the majority of trading in commodity happens in futures markets, we also choose to analyze futures directly. A natural generalization of the exponential decay model (

1) (and appearing explicitly in various papers, (see for example [

28]), is the following form of parameterization of variance with two exponential decays

where

B is the global decay and

is a long term decay (much smaller than

B),

is the normalization factor to match the implied market volatility, and

is the level of a long term volatility. Swindle [

29] uses this representation to model the total implied variance of commodity future.

We choose to model

instantaneous variance using the representation (

2). Introducing a time dependent instantaneous variance can be interpreted as non-uniform clock: we consider the total realized variance as "time". Under Samuelson, far away from the expiration the clock ticks very slowly, and it accelerates as we get closer to the expiry.

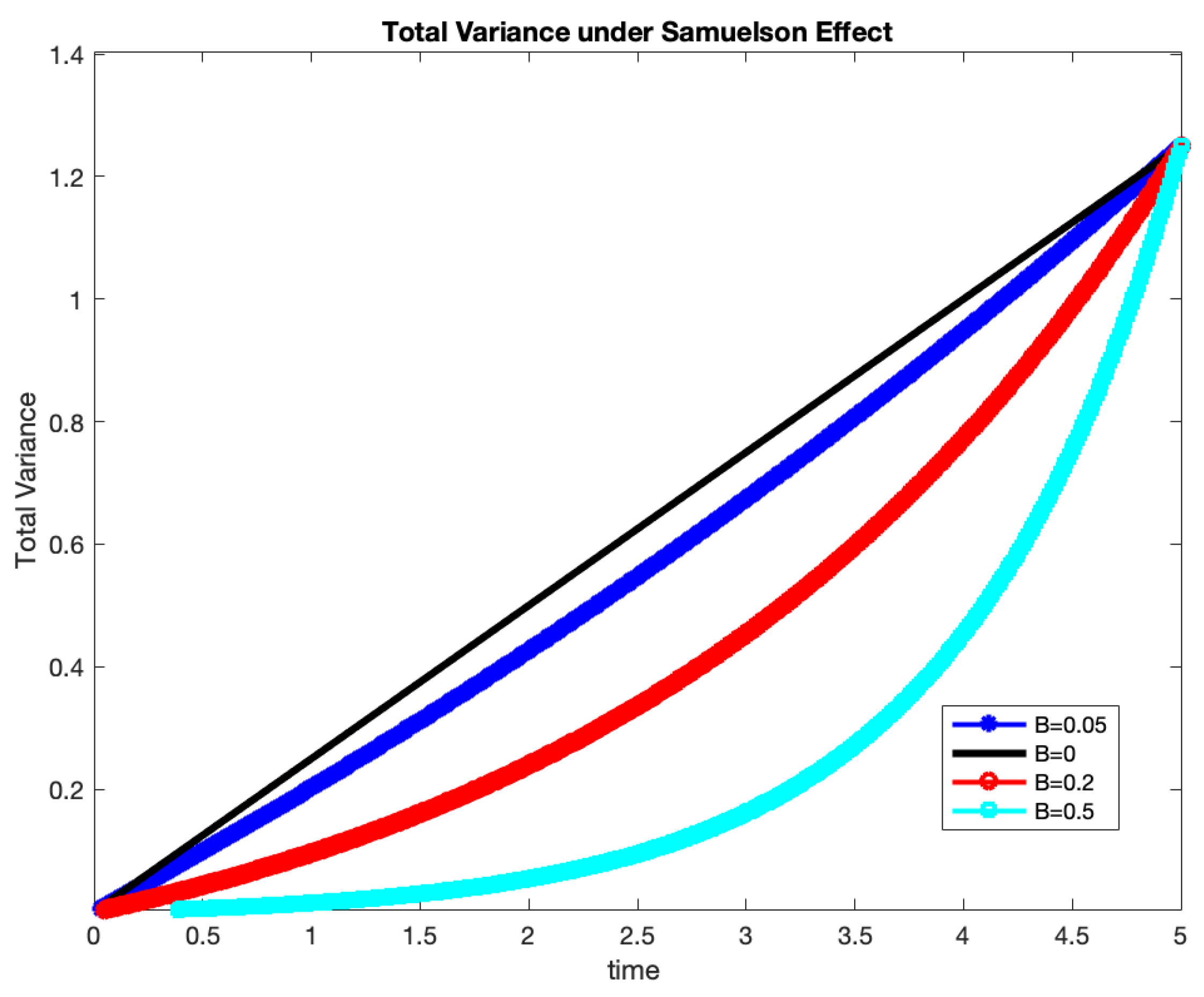

The

Figure 1 below illustrates the point. In this example we use the simplest model (

1) for instantaneous variance (thus

), and calculate the total variance (time) for a futures contract with expiry 5 years. Let the market implied volatility of the future be

. We consider different choices of decay

. Thus, from no Samuelson, to weak, moderate and very strong decay. In all cases the total realized variance between

and the expiration

T has to match the market implied variance

, but the way it gets there depends on

B. For a strong Samuelson

, about

of the total variance accumulates in the last year of the life of the contract.

In this paper, we devote our attention how to parameterize and more importantly, calibrate the increase of volatility when approaching contract maturity. We do not question the presence of Samuelson effect for considered commodity futures, neither we model the whole volatility surface, involving stochastic volatility models. Rather, we concentrate on Samuelson effect only and search for a practical solution which works, delivers stable results with error within the statistical model error. For that purpose, we employ the representation (

2) for the instantaneous variance and consider two exponential decay models: a simpler model with long term decay

, thus two parameters, called 1-decay model. Choice of modeling of instantaneous variance (or volatility) permits easy calibration to the market information ( implied volatilities) and calculation of variances on any future time intervals, using the aforementioned non-uniform clock.

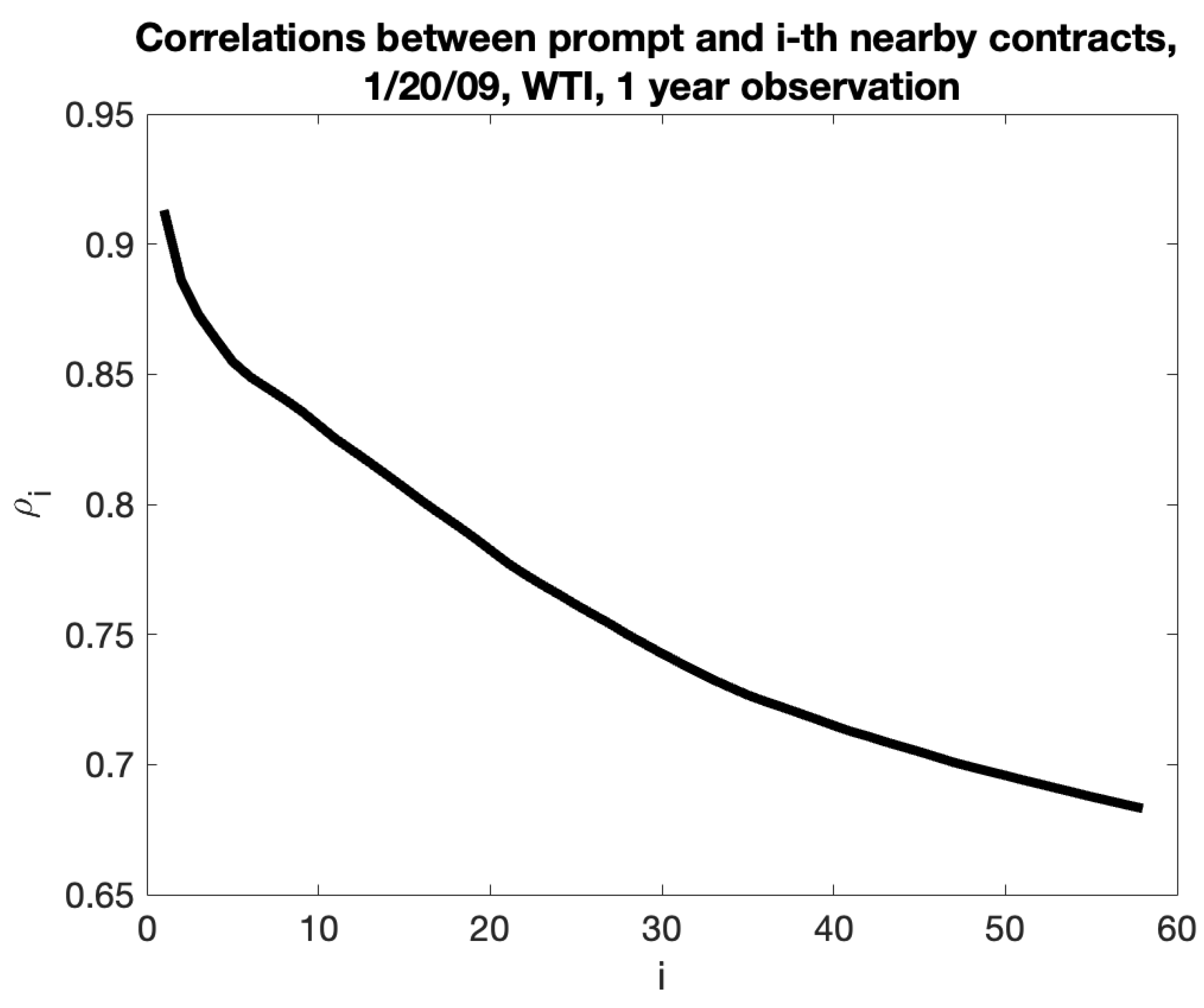

We opt for using data of nearby contracts and normalize the variances of their returns by the variance of the prompt contact. We develop analytics for statistical errors on normalized variances using results by Joarder [

30] to attain a benchmark for the calibration results, and present out of sample testing of the model. In our study we used 15 years of history for WTI, Brent and Natural Gas futures prices, 2006 - 2021, including the drama of Spring 2020. We generalize the calibration methodology to seasonal commodities such as natural gas. We contrast Samuelson strength vs the models performance in different historical periods. At crisis times, when Samuelson is strong, one should use 2-decay model, as it gives better results. From the other hand, at quiet times, therefore weak Samuelson, 1-decay model is totally adequate.

The closest research to our paper in the existing literature is the mentioned paper by Brooks and Teterin ("BT") [

17]. They also use nearby future returns, calculate the their standard deviations and fit a three factor parametrization by Nelson and Siegel [

18] with exponential decay. However there are key differences between our approaches. First, BT interpolate futures prices with Nelson-Sielge curve [

18], resulting is a vector of futures pseudo-price time-series with each time-series corresponding to an exact maturity on every trading day.

1. We use the raw prices of nearby future contracts, not mixing them. Even though as calendar time passes, the time to expiration of nearby future indeed changes and drifts to zero,

2 we deliver convincing results of the volatility–maturity relationship using raw prices.

Second, BT employ only 12 nearby contracts, while we include all available information, 60 contracts. BT do not account for seasonality when considering term structure of NG volatility. Our data includes crisis period of Spring 2020, which is quite interesting period to test models.

Third, the models and the target of the fit are different. The NS model [

18] model for yield curve

given by the parametric form

is based on the forward yield curve, see Diebold and Li (2006):

BT use (

3) to model

average volatility

of a synthetic forward contract with constant maturity

(in months). We fit instantaneous variance employing a representation (

2) similar to (

4), but with two exponential decays. For us, the main input in the model, governing the Samuelson strength, is given by exponential decay parameter

B. In the BT’s approach, the exponential decay parameter

is fixed at the initial stages of the fit, and the main parameter reflecting the Samuelson forte, is represented by the slope of the volatility term structure

.

Lastly, and most importantly, our main motivation is to find a natural and practical method to accommodate Samuelson effect in the evaluation of path dependent options, early expirations options, CVA, etc. That is why we choose the instantaneous variance as a subject of our study. This choice allows us to match the market information such options quotes on futures perfectly (through implied volatilities). BT [

17] aim to test the Samuelson hypothesis for variety of commodities and link the Samuelson strength to inventory levels and carry arbitrage.

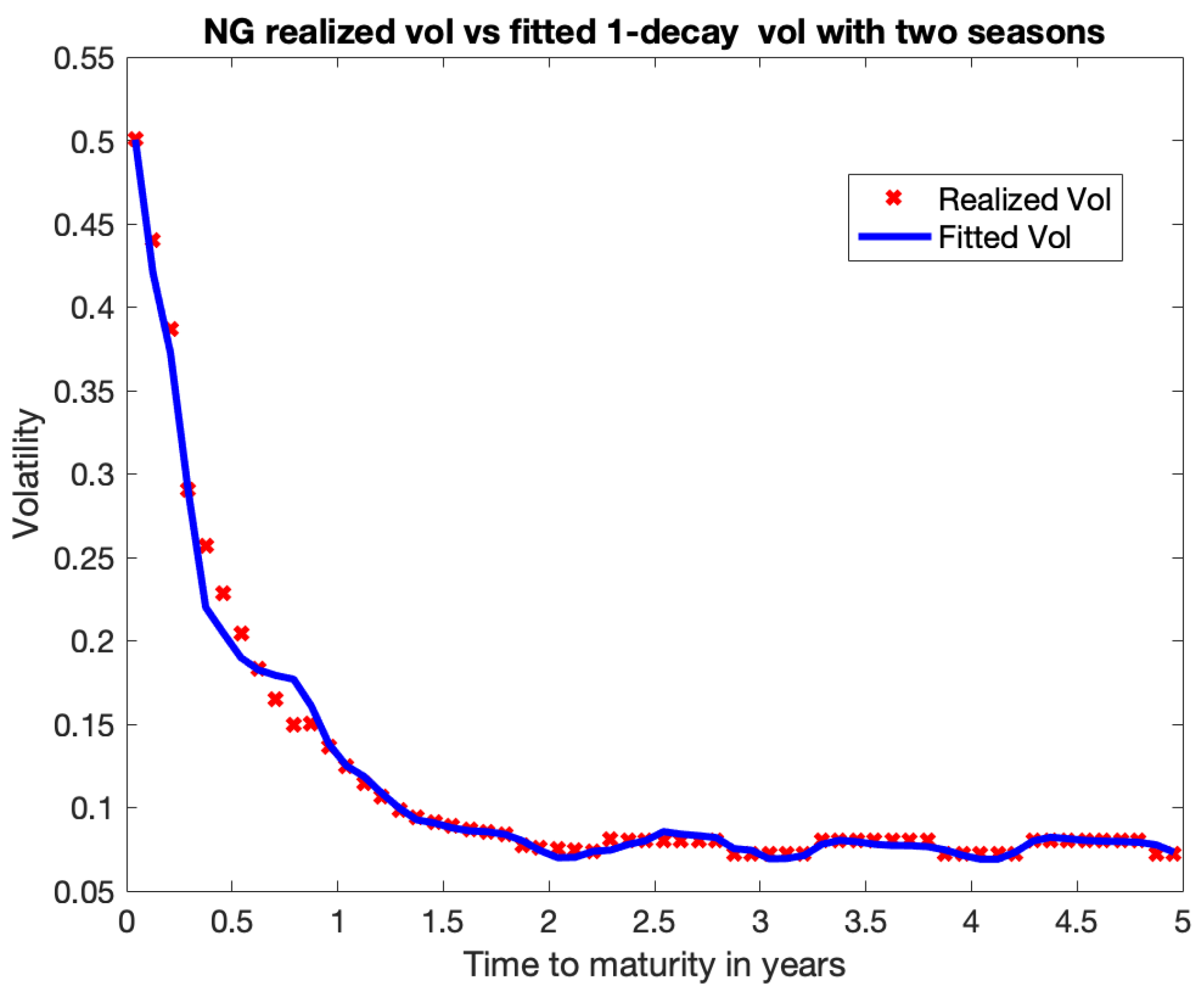

We generalized the calibration methodology to seasonal commodities such as Natural Gas. The Natural Gas term structure is defined by seasonality. Natural gas storage is a vital part of the natural gas delivery system and helps to balance supply and demand. During the winter season, from November to March (withdrawal season), gas consumption peaks as a result of increased heating demand. During the summer season, from April to October (injection season), gas demand decreases while production continues. Because of this, we fitted Samuelson independently after dividing the data for nearby futures into two periods: winter and summer. Since we used data of nearby contracts, with this separation, we were not allowed to concatenate returns from different seasons, for example, March and April. For that reason, we were forced to use only two months data of observation period. Despite the good fitting results, where the errors stayed largely within the statistical error, the results are not consistently stable due to the short observation period. Adding more seasons would cause even greater issues.

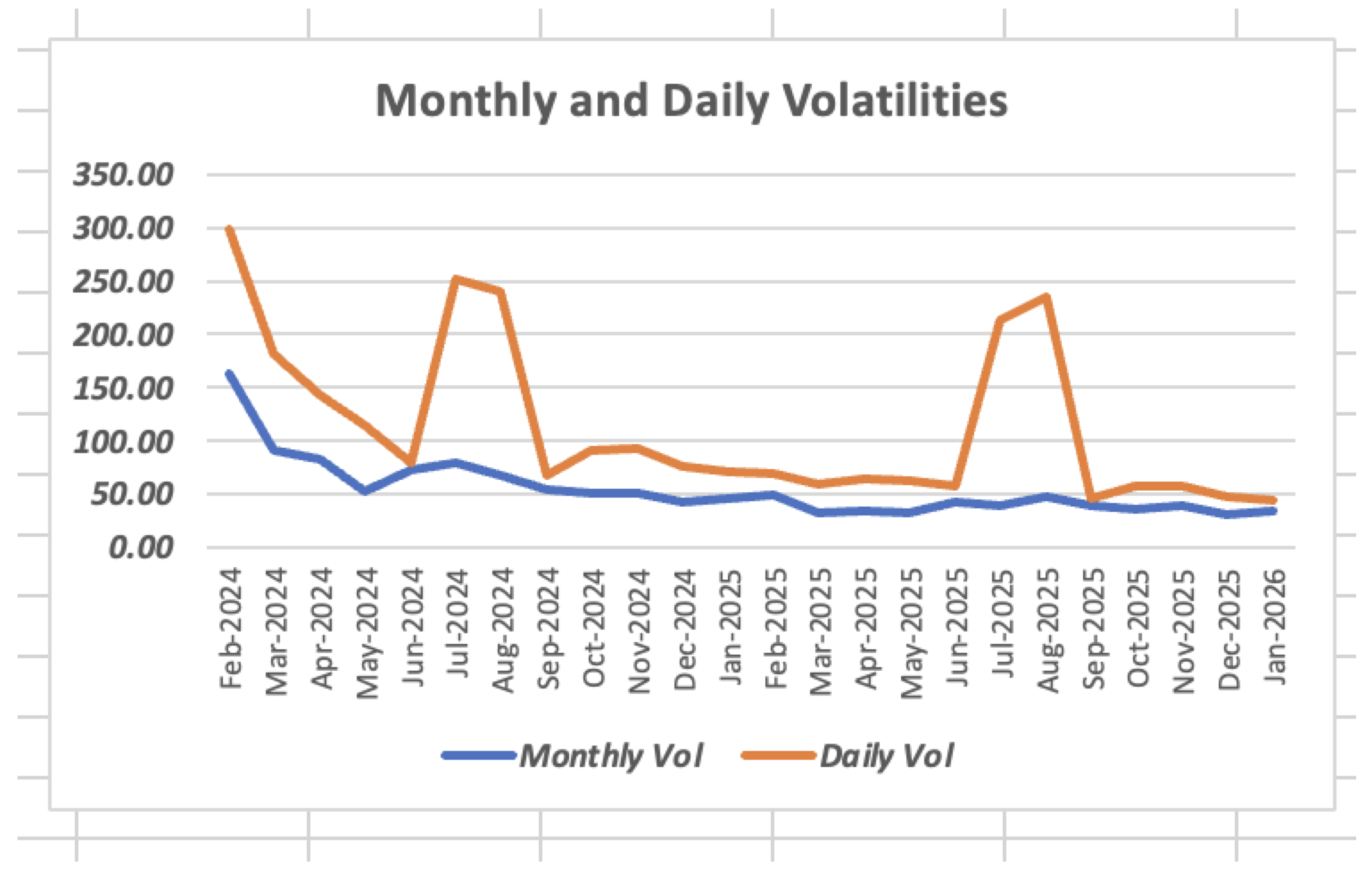

Next target was to find the methodology for Samuelson effect for a more complicated case of seasonal commodities, in particular electricity futures. Electricity always has been the most fascinating commodity to study due to non-storability (at least in meaningful quantities), therefore very high volatility and abundance of extreme events. Because supply and demand have to be in equilibrium at all times, the electricity seasonality is more refined that any other seasonal commodity. Each hour in each weekday and month has its own pattern and can be traded separately. Therefore, using only two seasons would not be enough, and we need to come up with a more granular seasonal model. The previous seasonal model for Natural Gas implies that

is roughly the same for months in the same season, and the Samuelson parameters

B,

and

are different for winter and summer months. Since we used only two months of nearby futures data, we were catching the Samuelson effect locally, at that particular period of time. The goal is to come up with a methodology which applicable to long term deals, such as popular Power Purchase Agreements ("PPA"), which become increasingly more popular in view of growing use of renewable energy. We use the same model for the instantaneous variance (

2), with

, however there is a number of differences between two approaches. Firstly, we assume that the normalization constant

depends on a month in year, and the Samuelson parameters

B and

are the same for all months. We consider only the 1-decay model with

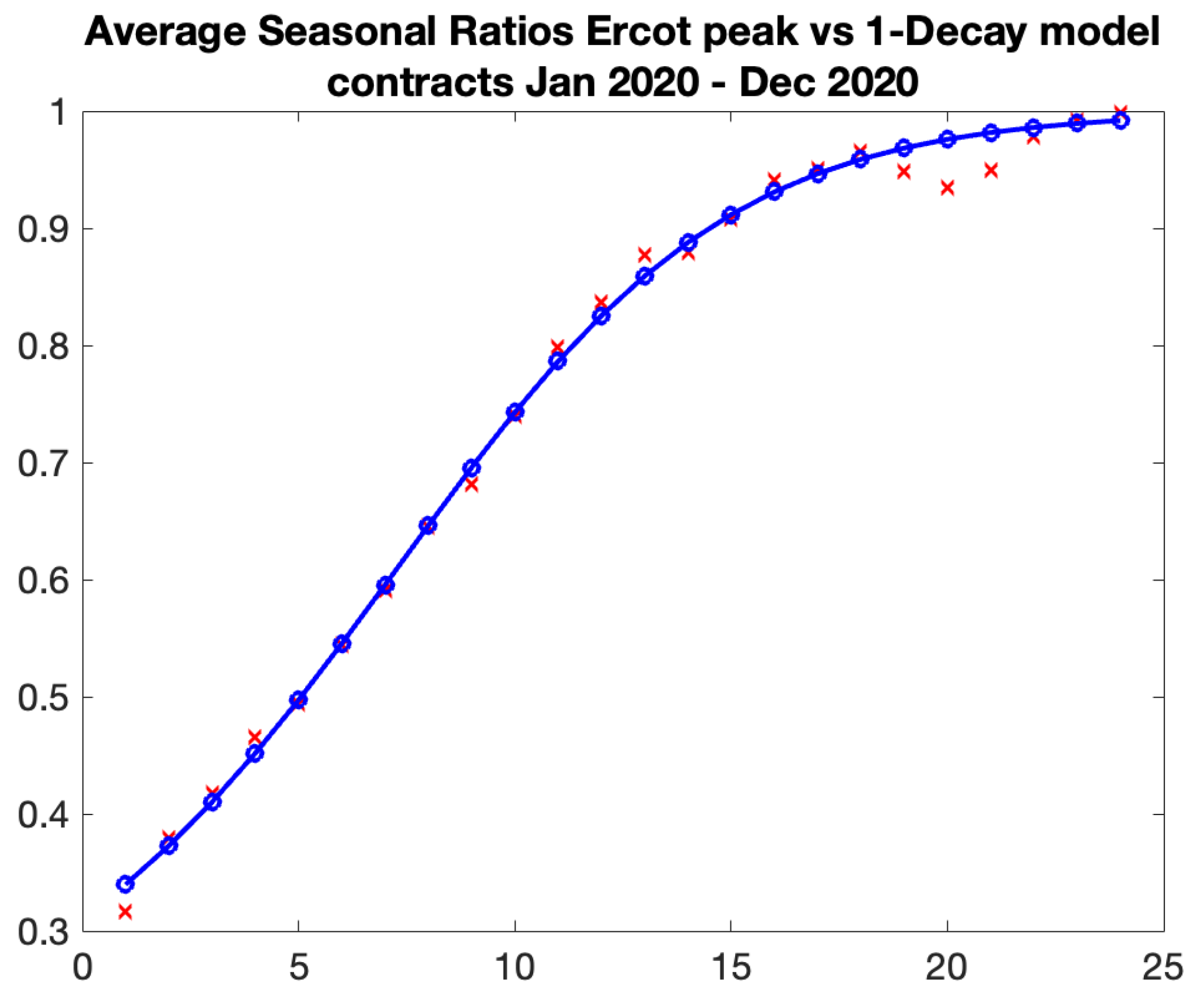

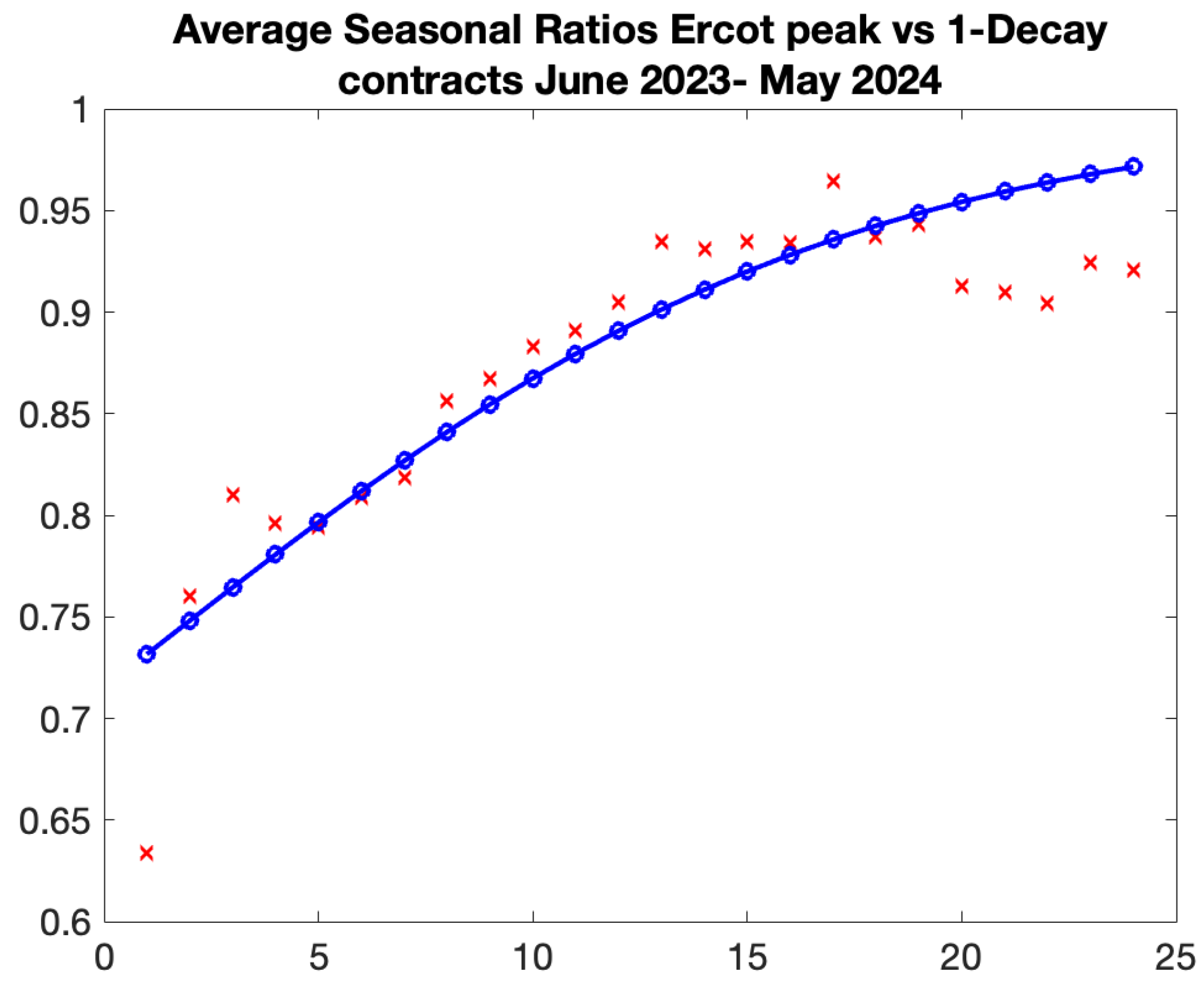

. Secondly, we use the real futures data and calculate the realized variance on one year observation period. As in the previous model we calculate the ratios of variances, but now we use the variances of the same calendar month. We average the ratios for 12 moving the observation period and fit the model. The results are stable.

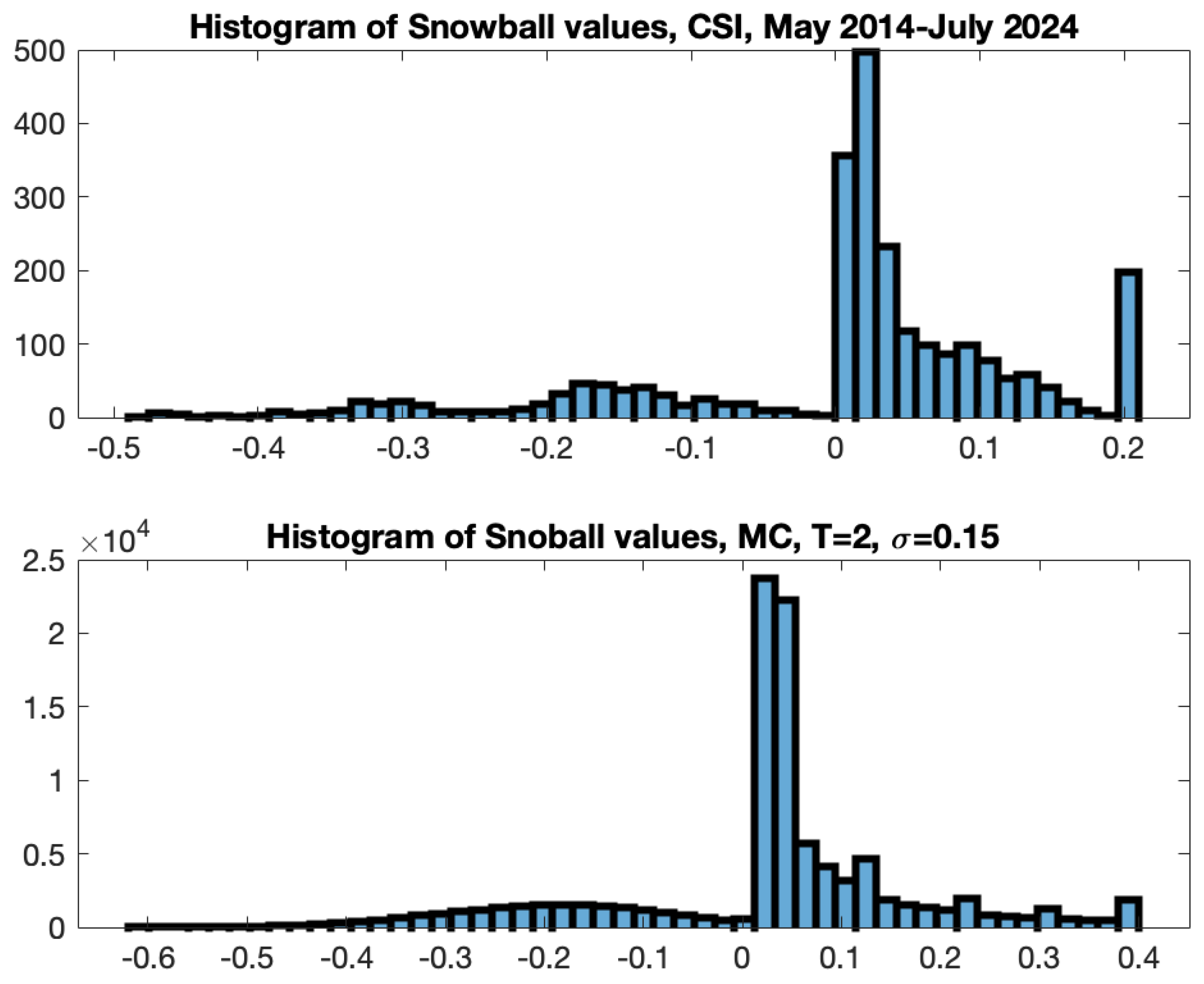

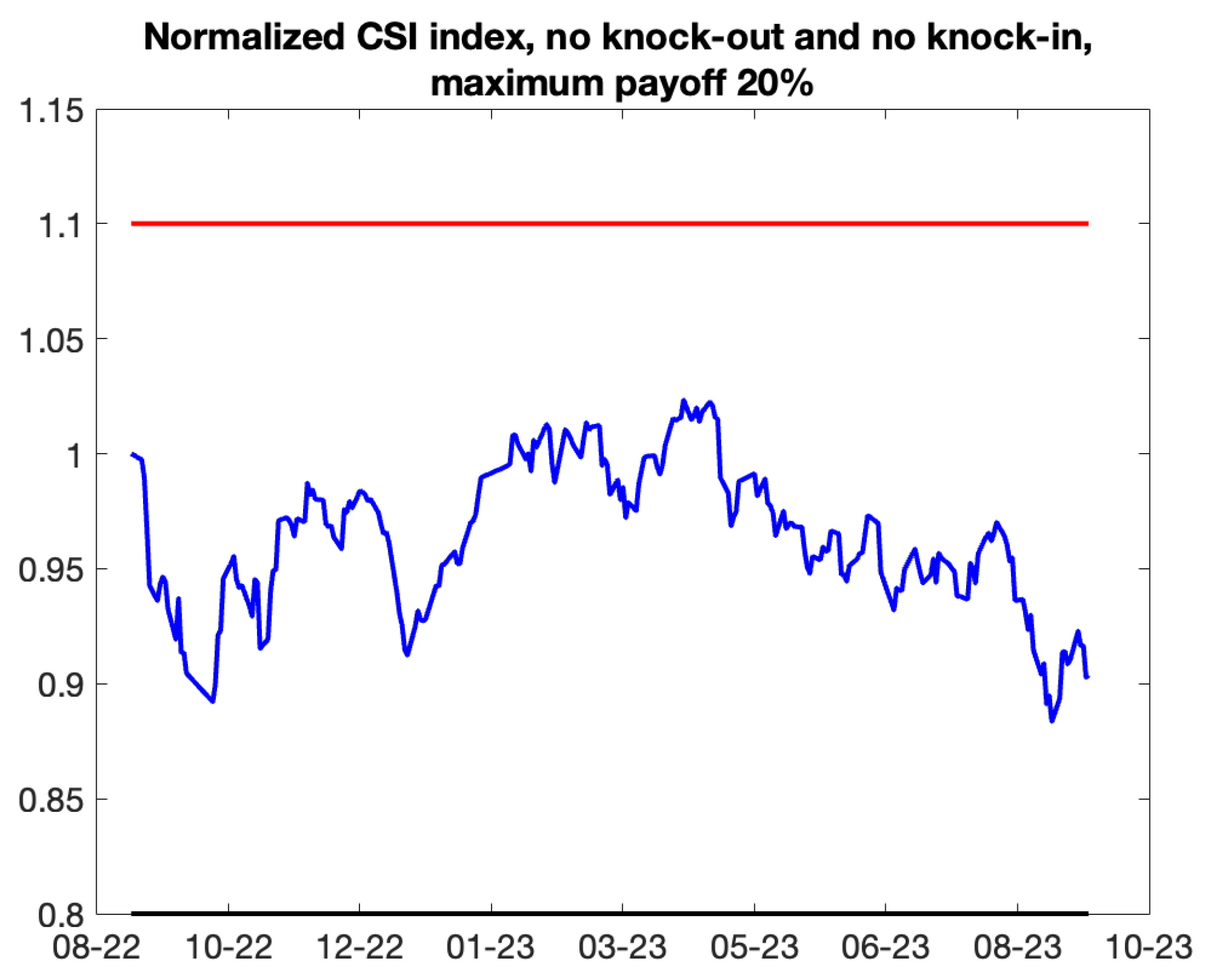

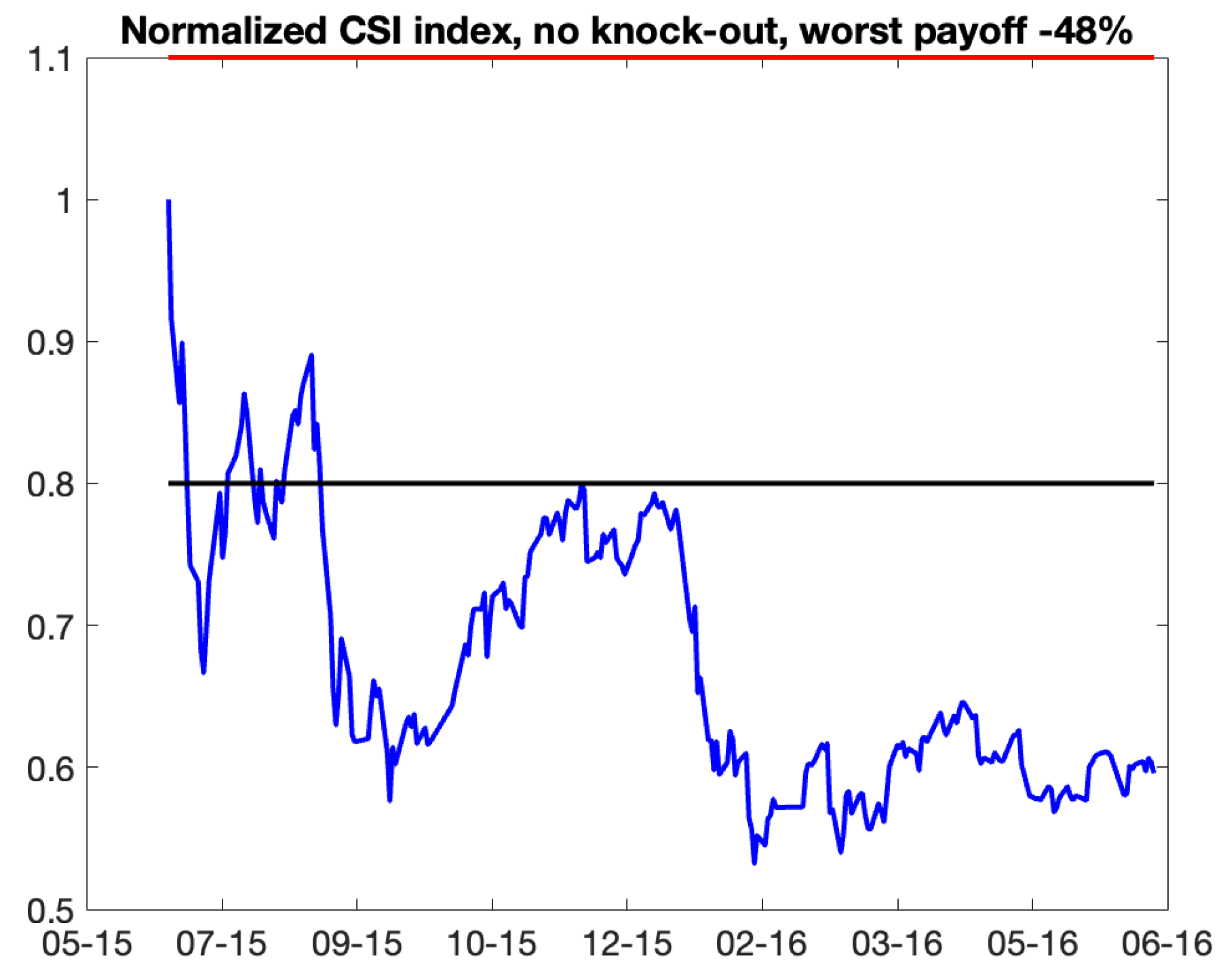

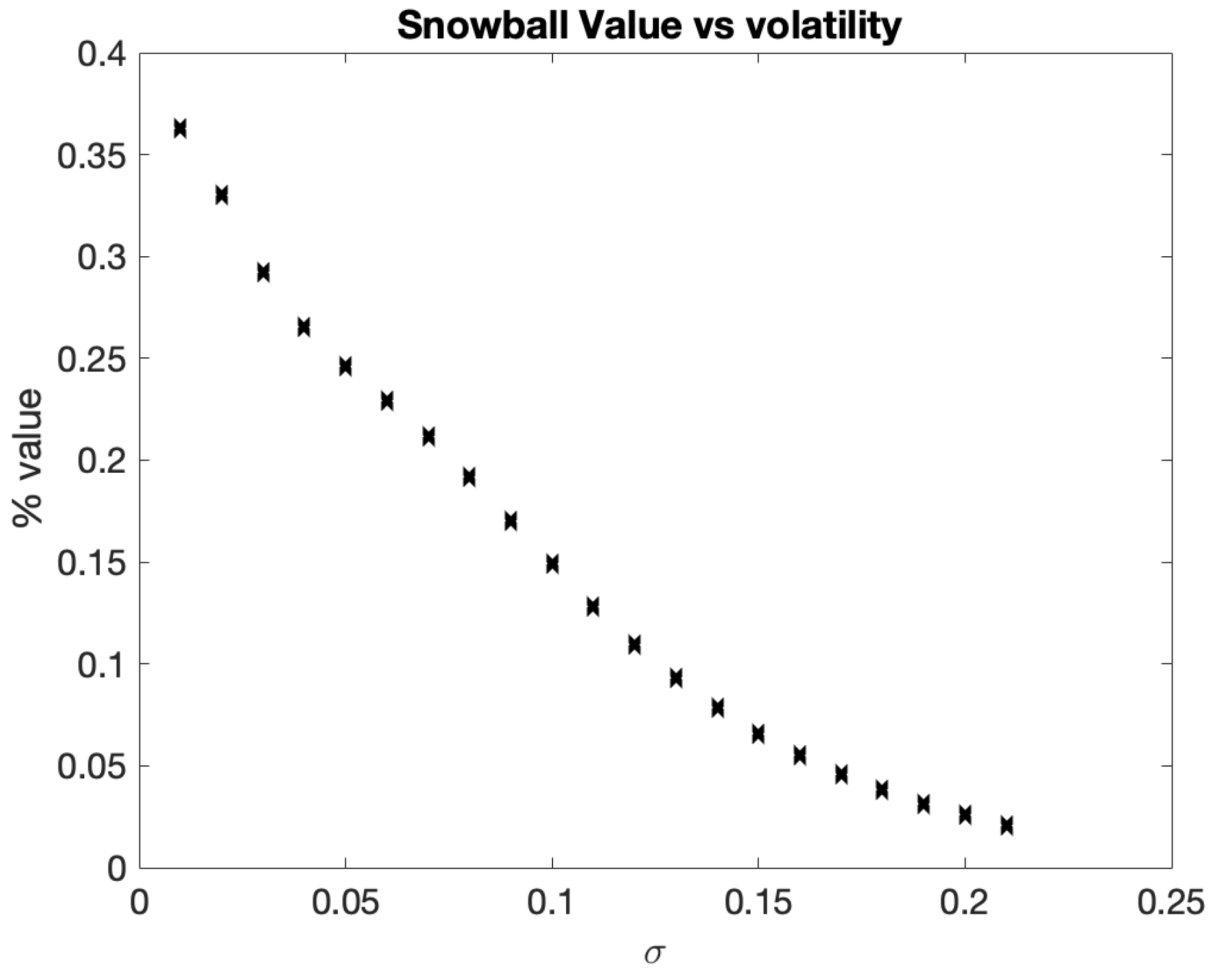

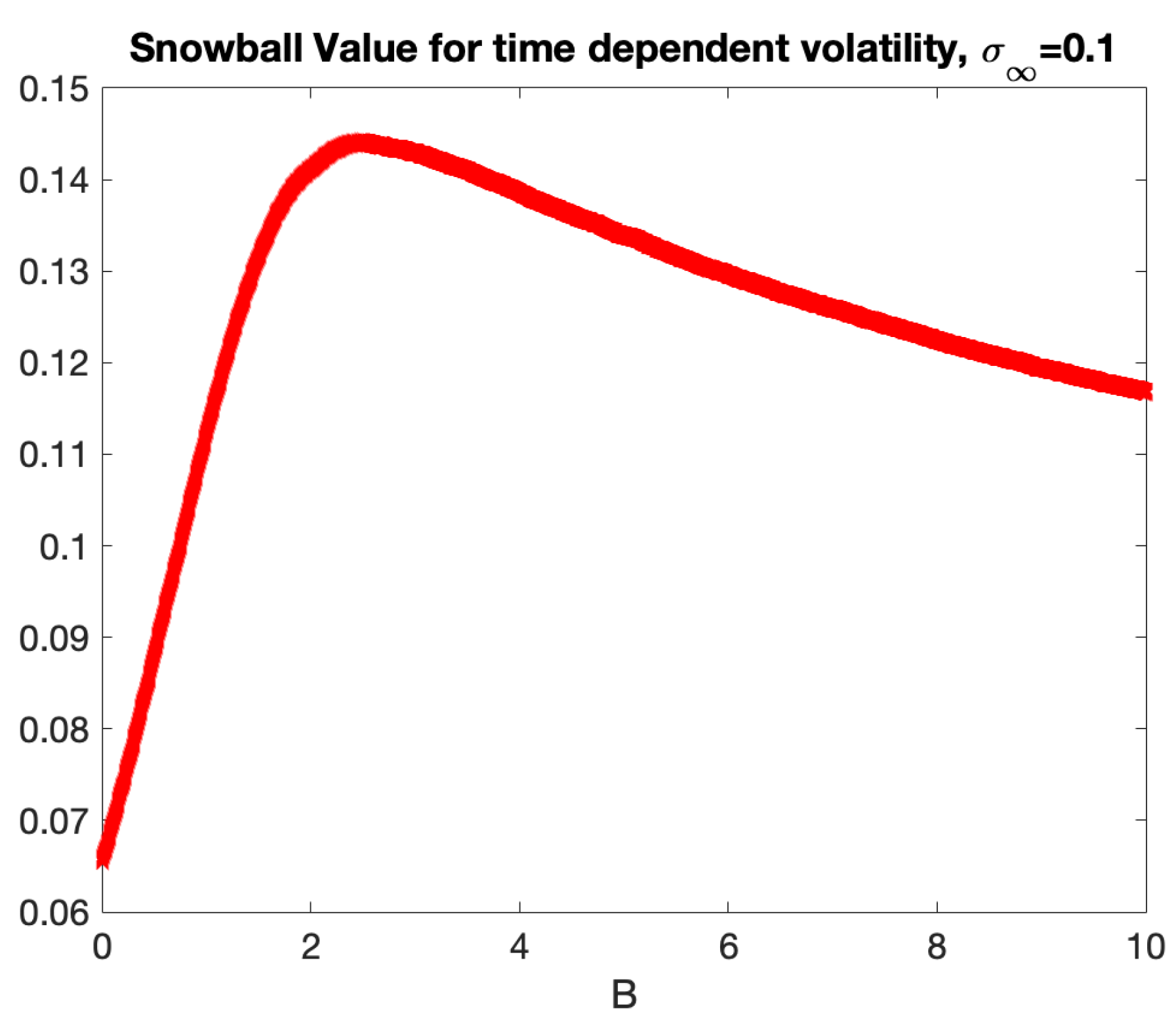

We demonstrated how the Samuelson effect can be used for commodities derivatives. Firstly, we outline the evaluation of early expiration options, such as swaptions. Secondly, we demonstrate how the calibrated model of the instantaneous variance can be used to extrapolate implied volatilities, which is crucially important in the evaluation of PPA’s. Furthermore, we discovered an intriguing application of the Samuelson effect to a popular auto-callable equity derivative, the snowball, see [

31]. The term ”snowball” describes an investor’s potential for profit accumulation. Snowball is type of auto-callable structure with two barriers: knock-out and knock-in set up as percentage of the initial price.The longer the investor retains an income certificate, the more is the profit, provided the underlying does not drop precipitously. Consequently, the payment of the snowball is contingent upon the realized variance of the underlying asset and the rate of its accumulation. Issuing auto-callable derivatives on assets influenced by the Samuelson effect can be beneficial, as initial low volatility may extend the duration of the asset remaining within barriers, hence yielding greater profit. Furthermore, we identified that, based on the structure of a snowball, keeping the realized variance constant, there is an optimal rate of variance growth that yield maximum profit.

We now outline the remainder of the paper.

Section 2 describes various calibration procedures, including generalization for seasonal commodities as Natural Gas.

Section 3 discusses the results of the calibration using 15 years of data for Wti, Brent and Natural Gas futures, the optimal choice of observation period and the model selection, the analytics of the statistical errors to access the goodness of the fit.

Section 4 outlines the calibration procedure of the Samuelson effect for electricity futures and presents the results using the historical data of North Hub Ercot electricity futures.

Section 4 concludes. Some of the details are given in Appendix.

2. Calibration Procedures of Samuelson

This section is devoted to the detailed description of the calibration of the Samuelson effect.

To investigate the Samuelson effect, we begin with a selection of data. A variety of data types can be used to calibrate a certain Samuelson form. We can start by using a snapshot of the implied at-the-money volatility of the market. Analyzing the historical realized volatilities of returns of futures contracts with expirations , calculated a time period , , is a further choice. Lastly, the third option would be to examine the return volatilities of nearby contracts. We can use the idea of "promptness" of a contract in place of specific contracts. The first nearby contract, also known as the prompt, is the closest future contract that is accessible at time t and has the shortest duration to expiration. The second nearby contract is the next accessible contract, etc. The second neighboring contract takes over as the first one when the first one expires, etc. We can define an i-th nearby contract in general.

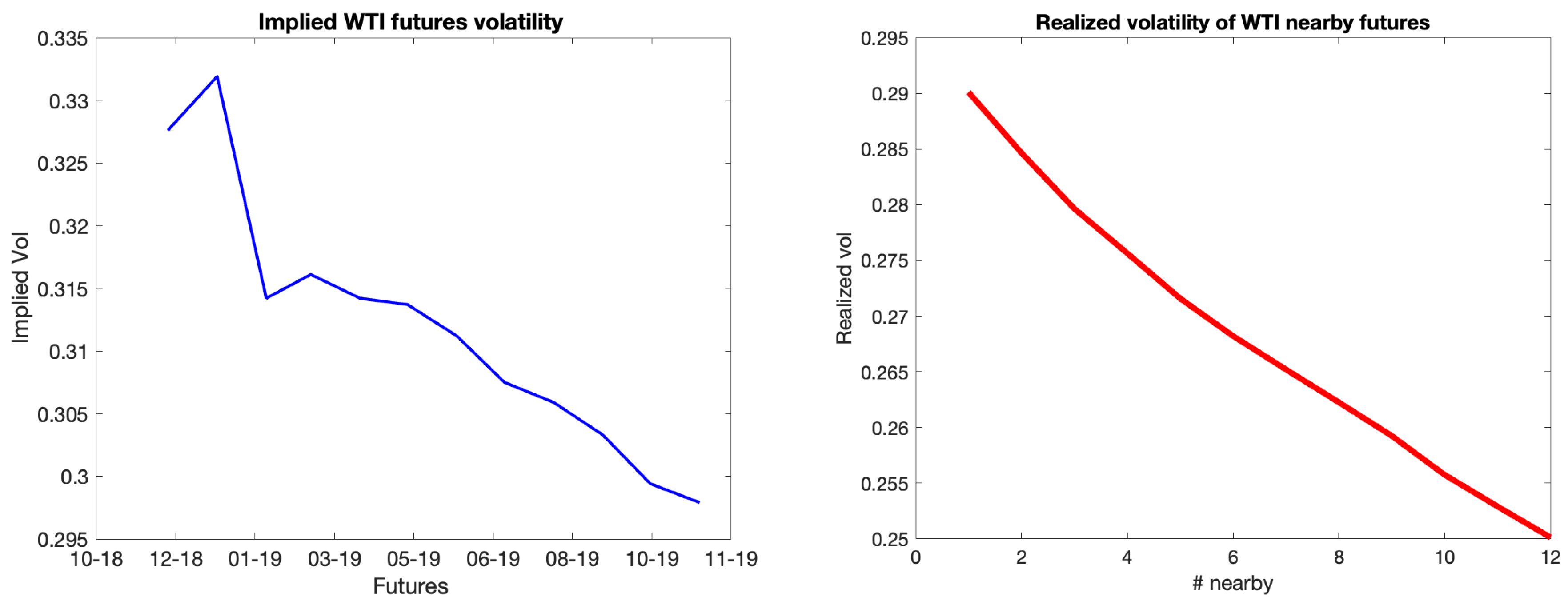

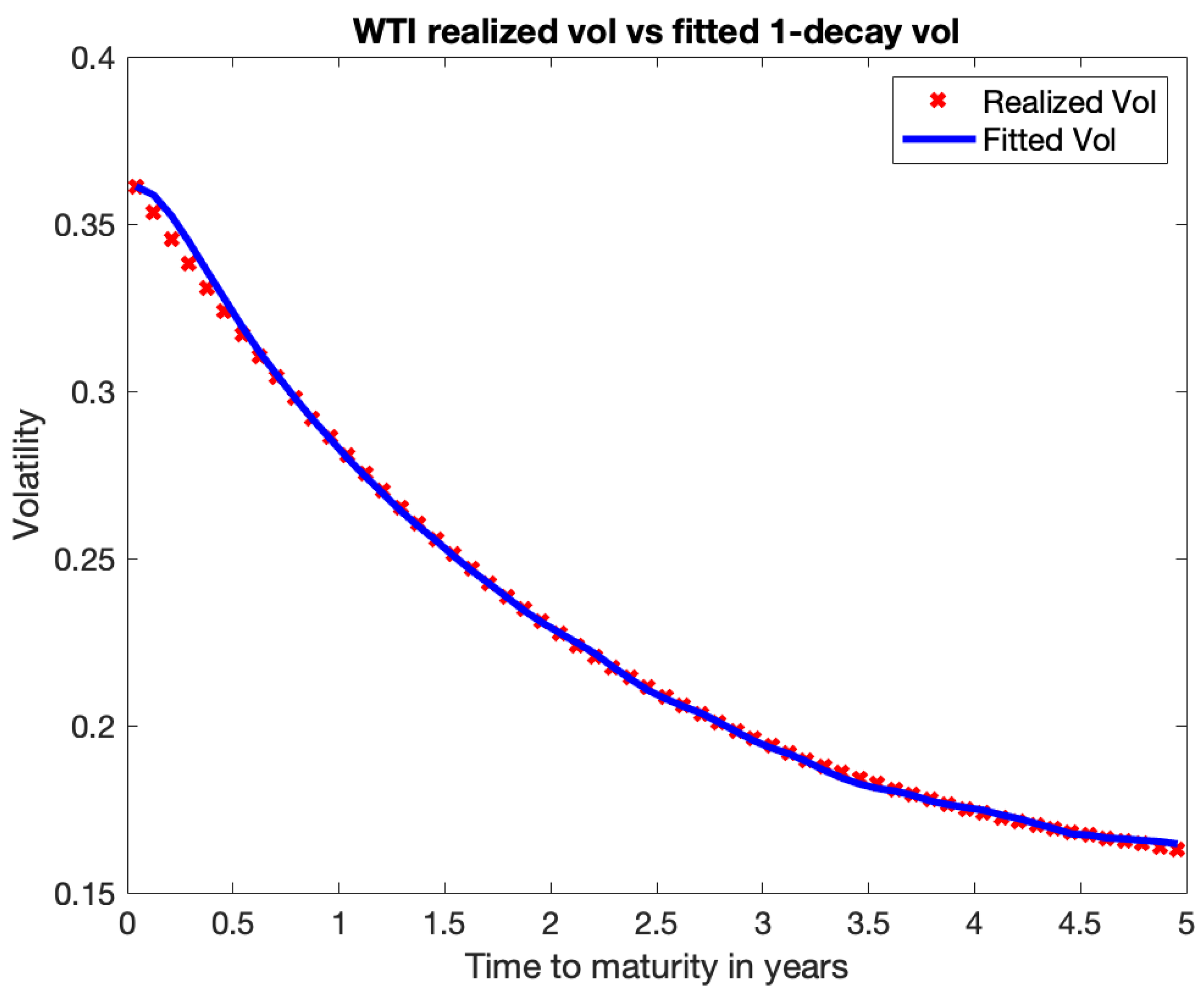

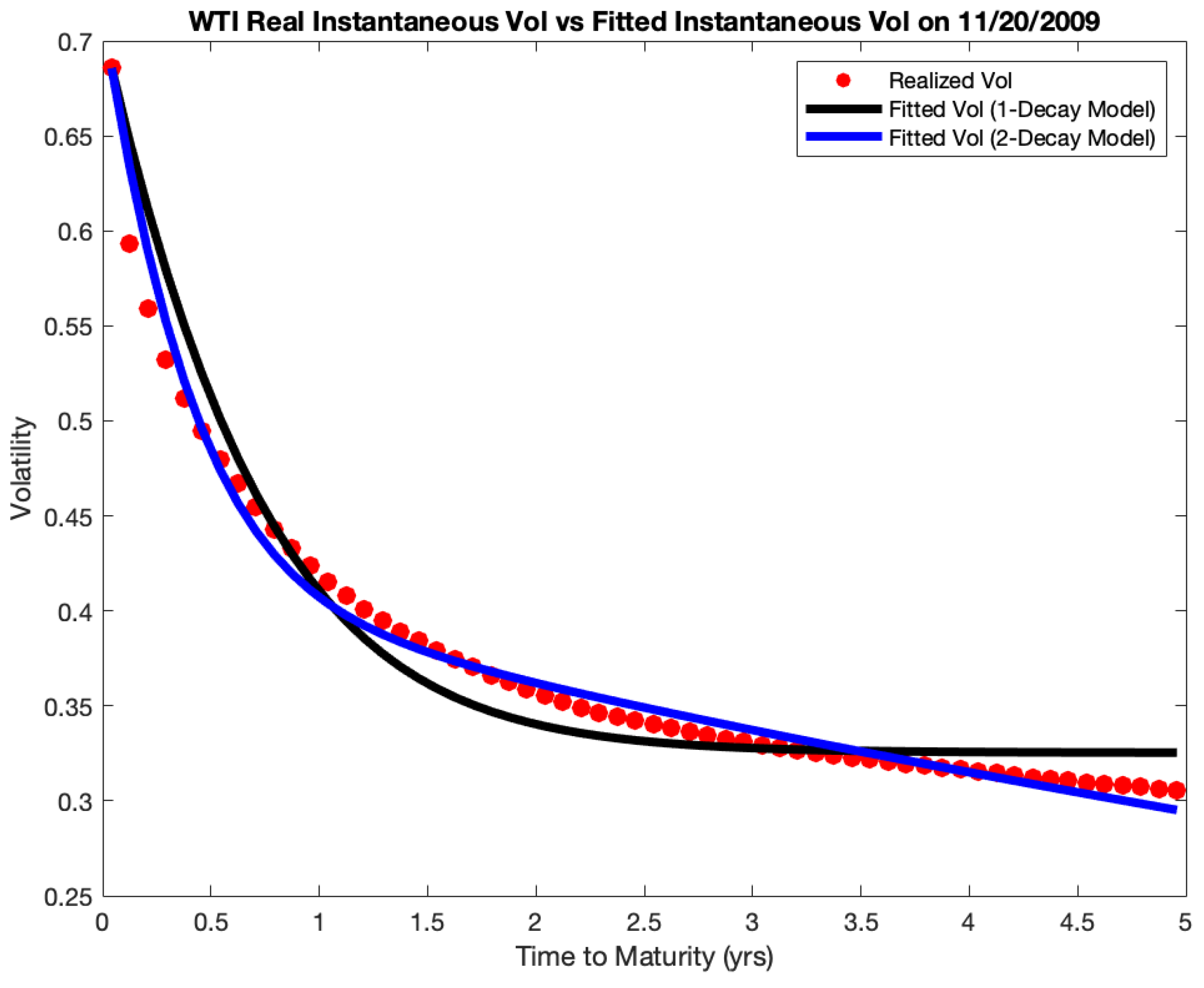

With the Samuelson effect, we anticipate lower volatility for farther-off futures. Utilizing data sources such as market indicated volatilities and forward-looking information has benefits. Option liquidity on futures longer than a year is, nevertheless, insufficient. There have been previous occasions when we have not observed an immediate decrease in volatility, which may be due to local market disturbances. However, historical realized volatilities reveal that realized volatilities almost usually decrease with expiration . Below is a picture of the WTI futures implied volatilities from December 2018 up to November 2019.

Since our approach is based on modeling instantaneous variance, the second source of data would involve integration to arrive to realized variance. Therefore, we choose to employ nearby contracts to capture the "true" instantaneous volatility. Thus, approach 3—the volatilities of returns of nearby contracts—is the data of choice for our analysis.

In order to eliminate the impact of volatility level and make the statistics comparable, we normalize the variances of the

i-th nearby contract by the variance of the first nearby contract:

These ratios provide the basis of the calibrating processes. In Joarder (2009), the statistical characteristics of the product and ratio of two correlated chi-square random variables were investigated. The paper’s findings will be used to calculate the statistical errors of the ratios. The Appendix C will contain the specifics.

We establish a set of model parameter

:

and

model ratios

that are inferred from the instantaneous variance’s form (

2):

where where

and

are times to maturity (in years) of the

i-th and the first nearby contracts correspondingly.

The general model calibration process adheres to the accepted methodology for determining which model parameters best fit the historical data. First, we choose an observation period

and construct series of nearby contracts

of historical settlement prices observed daily at

and

,

,

. For non-seasonal commodities, we used observation periods of two and twelve months, while for seasonal goods, we used two months. A two-month observation period usually equals M = 44, and a twelve-month observation period equals M = 252.

N is the number of observed contracts, usually N = 60, and

. After that, we compute log-returns.

We next compute realized variances of returns and document the previously established ratios. A constrained minimization of the total error determines the optimal set of model parameters

where

are the model ratios given by (

6). We assume that decay occurs mostly due to increase in

and cancel out the normalization constant

. The specific choices parameters

and the constraints are revealed in each case.

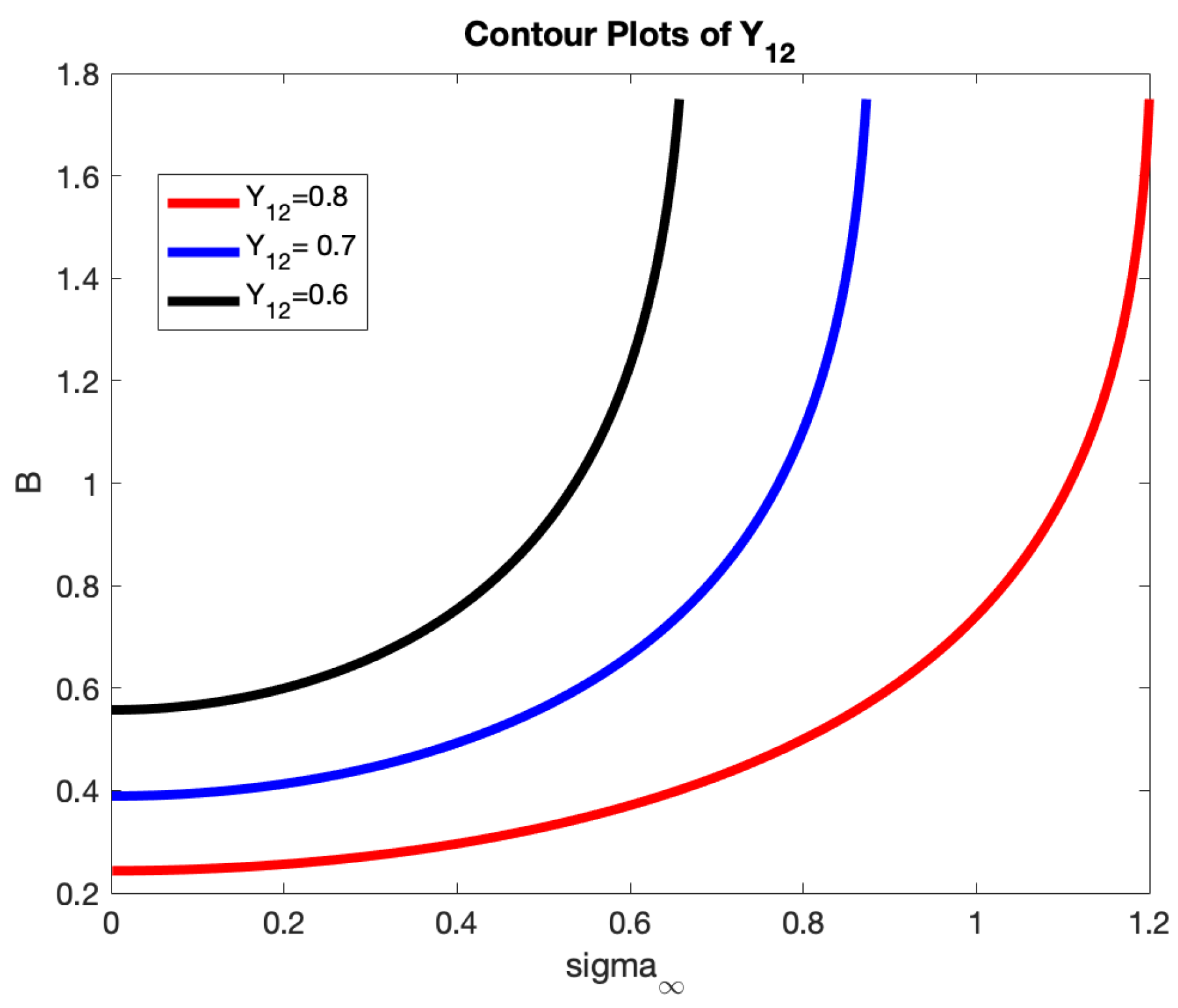

The primary challenge of the minimization problem is the possibility of various solutions because of the way parameters influence the ratios: an increase in long-term volatility

weakens the decay, whereas a higher

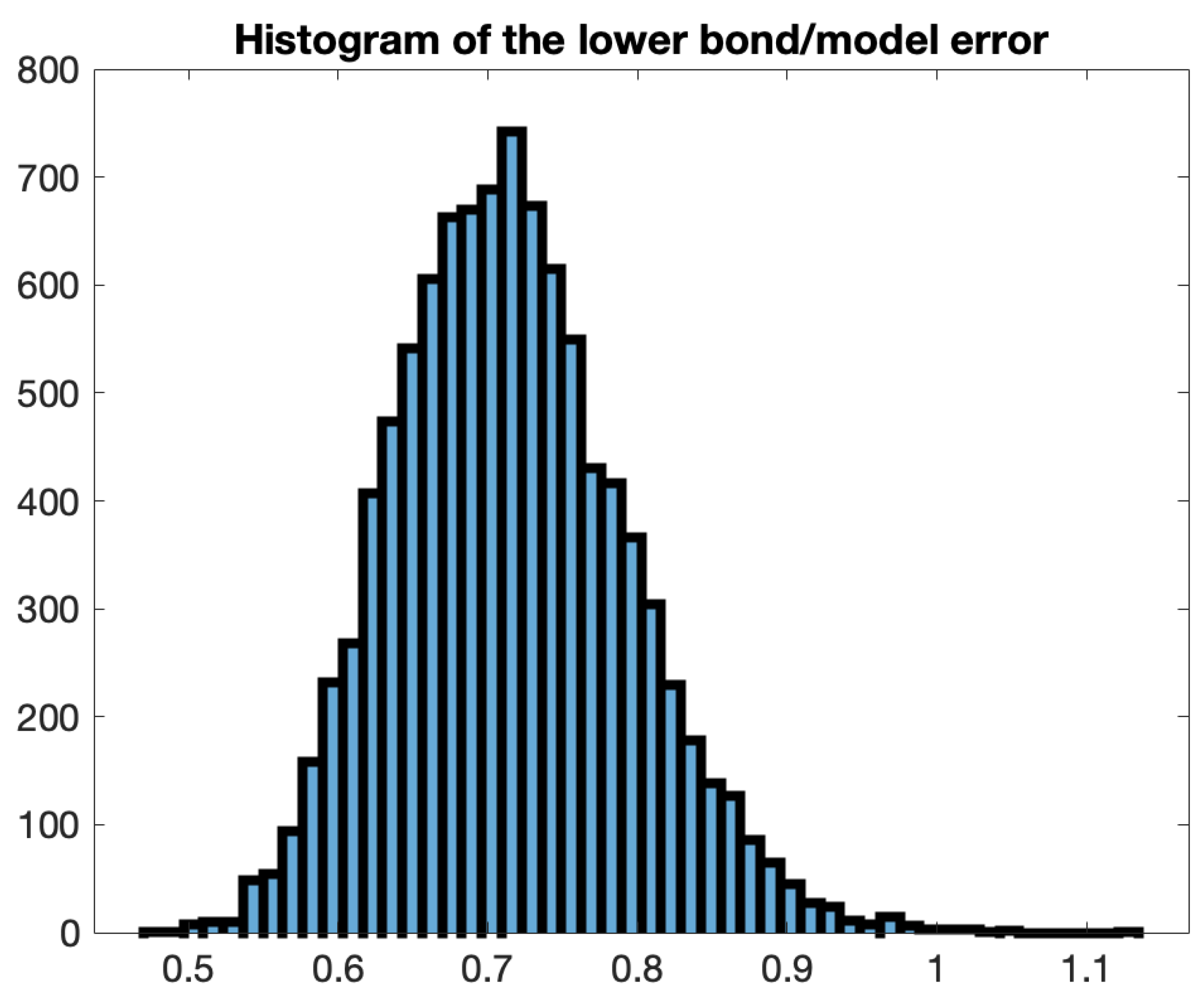

B drives ratios to decay more quickly. We should stay away from certain areas of the parameter space where slight adjustments to ratios result in significant changes to decay or long-term volatility. Several contour plots of the 12-month ratio

for the scenario where the long-term decay

. are shown in the following

Figure 3 to demonstrate this.

The model with two decays, B and , will be referred to as the 2-Decay model, whereas the model with will be called the 1-Decay model. Only in times of crisis, when Samuelson is very strong, do we need to use a more intricate 2 Decay model. The following section will provide examples.

2.1. Samuelson Effect for Seasonal Commodities

To accommodate Samuelson, the previous approach must be modified for seasonal commodities such as electricity, natural gas, heating oil, and gasoline. Our first emphasis is on natural gas, one of the most significant and "physical" commodities. The first seasonal model for Natural Gas assumes that is roughly the same throughout months within the same season, and the Samuelson parameters B, and are different for winter and summer months.

The subsequent objective was to identify the methodology for the Samuelson effect in a more complex scenario involving seasonal commodities, specifically electricity futures. Seasonality is more nuanced for electricity than for any other seasonal commodity. Every hour of each weekday and month exhibits a distinct pattern and can be traded independently. Consequently, relying solely on two seasons is insufficient; we must develop a more detailed seasonal model. We employ the identical model for the instantaneous variance (

2) with

while positing that the normalization constant

is contingent upon the month of the year, while the Samuelson parameters

B and

remain constant across all months. We utilize actual futures data to compute the realized variance over a one-year observation period. Similar to the prior model, we compute the ratios of variances; however, we now utilize the variances from the same calendar month. We compute the average ratios over a 12-month period, adjusting the observation timeframe, and subsequently fit the model. The results are stable.

2.1.1. Natural Gas

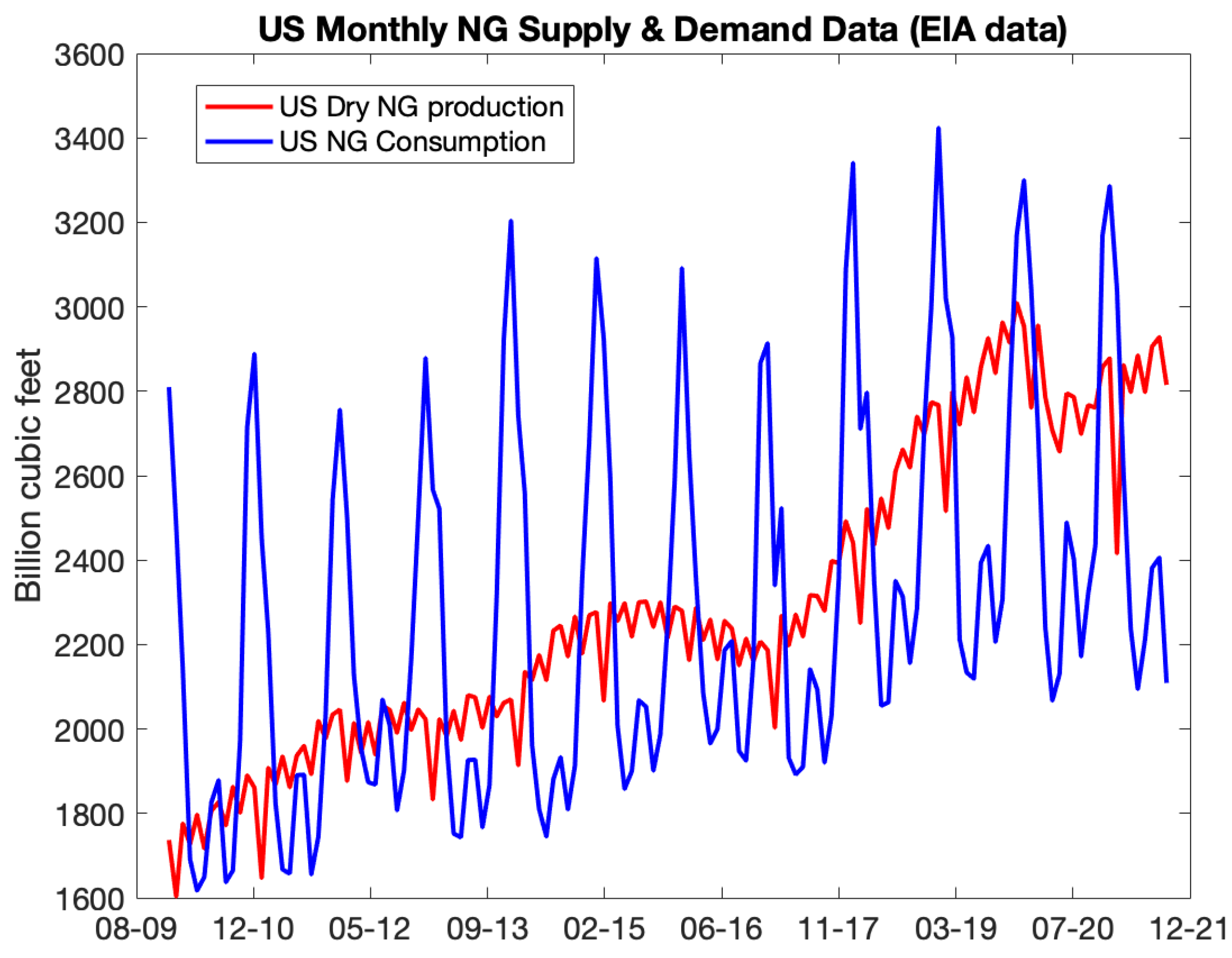

A typical monthly supply-demand chart for natural gas (NG) based on EIA data is shown in the

Figure 4. This type of chart can be found in many natural gas market references, such as Swindle (2014). Particularly during the winter, storage is essential to closing the gap between supply and demand.

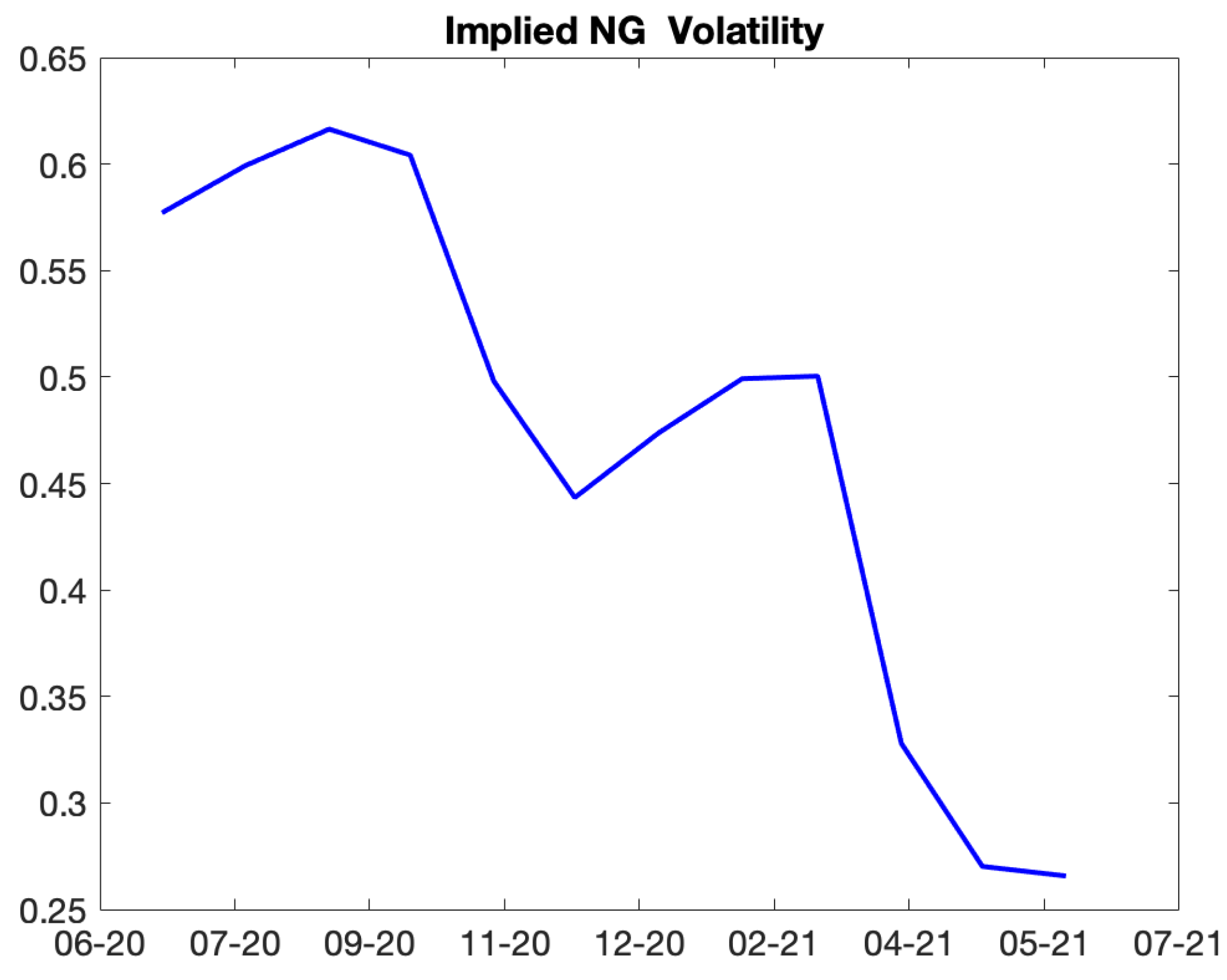

There are significant winter peaks in demand because of the cold weather, and milder summer peaks because of rising power use. Demand is cyclical, which causes seasonal patterns in prices and volatility. This makes a volatility term structure a superposition of decay with time to expiration and seasonal shape. An illustration of implied NG natural gas volatility can be found in

Figure 5.

Based on the data and the widely accepted description of natural gas storage seasons, we also choose to divide the Samuelson data into two periods: a summer (injection) season that runs from April to October, and a winter (withdrawal) season that runs from November to March.

Because of this division, we are unable to combine returns from various seasons, such March and April. Using an observation period of just one month is an easy fix. Fitting results are not convincing, though, because variance measured on (about) 22 data points is extremely noisy. As a result, we chose a two-month observation period, but we choose it carefully. For example, in September and October we observe first nearby futures prices from different seasons, therefore this period does not work. There are even more issues if we use additional months in the observation period, such as four or six, because we would have to leave out more combinations. Therefore, we decide to employ two months for the study time.

Using a similar process to that used for oil, mutatis mutandis, we fit a seasonal Samuelson independently.

2.1.2. Electricity

Electricity has consistently been the most intriguing commodity to examine due to its non-storability (at least currently, in significant quantities), resulting in considerable volatility and a prevalence of extreme events. Due to the necessity for supply and demand to be in equilibrium at all times, electricity seasonality is more nuanced than any other seasonal commodity, seen in both prices and volatilities.

Given this behavior, we formulate the subsequent assumptions regarding the dynamics of instantaneous variance (

2).

We will now proceed to outline the methodology for calibrating the Samuelson parameters B and by utilizing historical data of prospective prices that have been observed over a one-year period. Assume that the year 2022 is the desired observation period. We select the initial contract as the contract that we observed until its expiration during the observation period, which in this case is January 2023.

We adhere to the subsequent steps:

Record prices for the chosen contract for about one year prior to the expiration. In this particular instance, observations commence at time

, January 1, 2022, and continue until the contract’s expiration at

, contingent upon the market.

3 The observation period is defined as

.

Calculate log-returns and their standard deviation . This represents the realized volatility of the first contract.

Simultaneously compute the log-returns of further forward contracts, including Feb 23, Apr 23, and extending four years forward to Dec 27, with the identical observation period , and determine the standard deviations of their log-returns. Document 48 realized volatilities

Calculate ratios by dividing the volatility of each month and year by the volatility of the same month in the previous year:

Record 36 ratios which are functions of and only on the presumption on the assumption on the normalization constant .

Subsequently, replicate the aforementioned steps 1-4, commencing on February 23, while advancing the observation term by one month, initiating from February 1, 2022, until the contract’s expiration. The approach yields an additional set of 36 ratios. Select March 23 and continue until December 2023. Consequently, we shall obtain 12 sets of 36 ratios. Observe that the time periods

and

are approximately same across all sets.

Given that they rely solely on times rather than the month of the year, we can average each promptness i across 12 sets to determine the optimal parameters B and that encapsulate the Samuelson effect.

Our objective is to develop a methodology suited to long-term agreements, such as prevalent Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs). Consequently, we have opted to examine a global pattern of volatility term structure, rather than a more detailed seasonal decay as conducted in our analysis of natural gas.

We will now describe the outcomes of the calibration tasks.